Peer Reviewed Literature

What is peer review, terminology, peer review what does that mean, what types of articles are peer-reviewed, what information is not peer-reviewed, what about google scholar.

- How do I find peer-reviewed articles?

- Scholarly vs. Popular Sources

Research Librarian

For more help on this topic, please contact our Research Help Desk: [email protected] or 781-768-7303. Stay up-to-date on our current hours . Note: all hours are EST.

This Guide was created by Carolyn Swidrak (retired).

Research findings are communicated in many ways. One of the most important ways is through publication in scholarly, peer-reviewed journals.

Research published in scholarly journals is held to a high standard. It must make a credible and significant contribution to the discipline. To ensure a very high level of quality, articles that are submitted to scholarly journals undergo a process called peer-review.

Once an article has been submitted for publication, it is reviewed by other independent, academic experts (at least two) in the same field as the authors. These are the peers. The peers evaluate the research and decide if it is good enough and important enough to publish. Usually there is a back-and-forth exchange between the reviewers and the authors, including requests for revisions, before an article is published.

Peer review is a rigorous process but the intensity varies by journal. Some journals are very prestigious and receive many submissions for publication. They publish only the very best, most highly regarded research.

The terms scholarly, academic, peer-reviewed and refereed are sometimes used interchangeably, although there are slight differences.

Scholarly and academic may refer to peer-reviewed articles, but not all scholarly and academic journals are peer-reviewed (although most are.) For example, the Harvard Business Review is an academic journal but it is editorially reviewed, not peer-reviewed.

Peer-reviewed and refereed are identical terms.

From Peer Review in 3 Minutes [Video], by the North Carolina State University Library, 2014, YouTube (https://youtu.be/rOCQZ7QnoN0).

Peer reviewed articles can include:

- Original research (empirical studies)

- Review articles

- Systematic reviews

- Meta-analyses

There is much excellent, credible information in existence that is NOT peer-reviewed. Peer-review is simply ONE MEASURE of quality.

Much of this information is referred to as "gray literature."

Government Agencies

Government websites such as the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) publish high level, trustworthy information. However, most of it is not peer-reviewed. (Some of their publications are peer-reviewed, however. The journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, published by the CDC is one example.)

Conference Proceedings

Papers from conference proceedings are not usually peer-reviewed. They may go on to become published articles in a peer-reviewed journal.

Dissertations

Dissertations are written by doctoral candidates, and while they are academic they are not peer-reviewed.

Many students like Google Scholar because it is easy to use. While the results from Google Scholar are generally academic they are not necessarily peer-reviewed. Typically, you will find:

- Peer reviewed journal articles (although they are not identified as peer-reviewed)

- Unpublished scholarly articles (not peer-reviewed)

- Masters theses, doctoral dissertations and other degree publications (not peer-reviewed)

- Book citations and links to some books (not necessarily peer-reviewed)

- Next: How do I find peer-reviewed articles? >>

- Last Updated: Feb 12, 2024 9:39 AM

- URL: https://libguides.regiscollege.edu/peer_review

What are Peer-Reviewed Journals?

- A Definition of Peer-Reviewed

- Research Guides and Tutorials

- Library FAQ Page This link opens in a new window

Research Help

540-828-5642 [email protected] 540-318-1962

- Bridgewater College

- Church of the Brethren

- regional history materials

- the Reuel B. Pritchett Museum Collection

Additional Resources

- What are Peer-reviewed Articles and How Do I Find Them? From Capella University Libraries

Introduction

Peer-reviewed journals (also called scholarly or refereed journals) are a key information source for your college papers and projects. They are written by scholars for scholars and are an reliable source for information on a topic or discipline. These journals can be found either in the library's online databases, or in the library's local holdings. This guide will help you identify whether a journal is peer-reviewed and show you tips on finding them.

What is Peer-Review?

Peer-review is a process where an article is verified by a group of scholars before it is published.

When an author submits an article to a peer-reviewed journal, the editor passes out the article to a group of scholars in the related field (the author's peers). They review the article, making sure that its sources are reliable, the information it presents is consistent with the research, etc. Only after they give the article their "okay" is it published.

The peer-review process makes sure that only quality research is published: research that will further the scholarly work in the field.

When you use articles from peer-reviewed journals, someone has already reviewed the article and said that it is reliable, so you don't have to take the steps to evaluate the author or his/her sources. The hard work is already done for you!

Identifying Peer-Review Journals

If you have the physical journal, you can look for the following features to identify if it is peer-reviewed.

Masthead (The first few pages) : includes information on the submission process, the editorial board, and maybe even a phrase stating that the journal is "peer-reviewed."

Publisher: Peer-reviewed journals are typically published by professional organizations or associations (like the American Chemical Society). They also may be affiliated with colleges/universities.

Graphics: Typically there either won't be any images at all, or the few charts/graphs are only there to supplement the text information. They are usually in black and white.

Authors: The authors are listed at the beginning of the article, usually with information on their affiliated institutions, or contact information like email addresses.

Abstracts: At the beginning of the article the authors provide an extensive abstract detailing their research and any conclusions they were able to draw.

Terminology: Since the articles are written by scholars for scholars, they use uncommon terminology specific to their field and typically do not define the words used.

Citations: At the end of each article is a list of citations/reference. These are provided for scholars to either double check their work, or to help scholars who are researching in the same general area.

Advertisements: Peer-reviewed journals rarely have advertisements. If they do the ads are for professional organizations or conferences, not for national products.

Identifying Articles from Databases

When you are looking at an article in an online database, identifying that it comes from a peer-reviewed journal can be more difficult. You do not have access to the physical journal to check areas like the masthead or advertisements, but you can use some of the same basic principles.

Points you may want to keep in mind when you are evaluating an article from a database:

- A lot of databases provide you with the option to limit your results to only those from peer-reviewed or refereed journals. Choosing this option means all of your results will be from those types of sources.

- When possible, choose the PDF version of the article's full text. Since this is exactly as if you photocopied from the journal, you can get a better idea of its layout, graphics, advertisements, etc.

- Even in an online database you still should be able to check for author information, abstracts, terminology, and citations.

- Next: Research Guides and Tutorials >>

- Last Updated: Dec 12, 2023 4:06 PM

- URL: https://libguides.bridgewater.edu/c.php?g=945314

What is peer review?

From a publisher’s perspective, peer review functions as a filter for content, directing better quality articles to better quality journals and so creating journal brands.

Running articles through the process of peer review adds value to them. For this reason publishers need to make sure that peer review is robust.

Editor Feedback

"Pointing out the specifics about flaws in the paper’s structure is paramount. Are methods valid, is data clearly presented, and are conclusions supported by data?” (Editor feedback)

“If an editor can read your comments and understand clearly the basis for your recommendation, then you have written a helpful review.” (Editor feedback)

Peer Review at Its Best

What peer review does best is improve the quality of published papers by motivating authors to submit good quality work – and helping to improve that work through the peer review process.

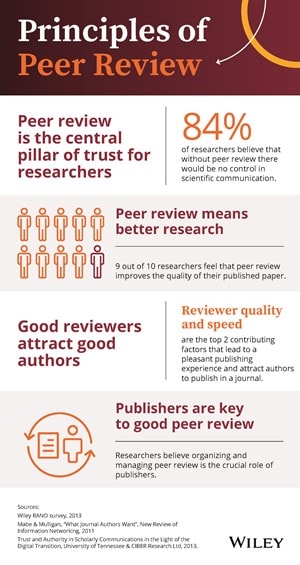

In fact, 90% of researchers feel that peer review improves the quality of their published paper (University of Tennessee and CIBER Research Ltd, 2013).

What the Critics Say

The peer review system is not without criticism. Studies show that even after peer review, some articles still contain inaccuracies and demonstrate that most rejected papers will go on to be published somewhere else.

However, these criticisms should be understood within the context of peer review as a human activity. The occasional errors of peer review are not reasons for abandoning the process altogether – the mistakes would be worse without it.

Improving Effectiveness

Some of the ways in which Wiley is seeking to improve the efficiency of the process, include:

- Reducing the amount of repeat reviewing by innovating around transferable peer review

- Providing training and best practice guidance to peer reviewers

- Improving recognition of the contribution made by reviewers

Visit our Peer Review Process and Types of Peer Review pages for additional detailed information on peer review.

Transparency in Peer Review

Wiley is committed to increasing transparency in peer review, increasing accountability for the peer review process and giving recognition to the work of peer reviewers and editors. We are also actively exploring other peer review models to give researchers the options that suit them and their communities.

Special Issues

Special Issues are subject to extensive review, during which journal Editors or Editorial Board input is solicited for each proposal. Our approval process includes an assessment of the rationale and scope of the proposed topic(s), and the expertise of Guest Editors, if any are involved. Special Issue articles must follow the same policies as described in the journal's Author Guidelines.

Editor/Editorial Board papers

Papers authored by Editors or Editorial Board members of the title are sent to Editors that are unaffiliated with the author or institution and monitored carefully to ensure there is no peer review bias.

- Student Services

- Faculty Services

Peer Review and Primary Literature: An Introduction: Peer Review: What is it?

- Scholarly Journal vs. Magazine

- Peer Review: What is it?

- Finding Peer-Reviewed Articles

- Primary Journal Literature

- Is it Primary Research? How Do I Know?

What is Peer Review?

What Does "Peer Reviewed" Mean? When a journal is peer-reviewed (also called " Refereed "), it means that all articles submitted for publication have gone through a rigorous evaluation. To ensure that each article meets the highest standards of scholarship, it is evaluated by the editor(s) of the journal. This is sometimes called " internal review ." In some cases multiple in-house research editors will evaluate the scholarly strength of the article before even considering it for further peer-review.

The editor(s) then enlists the services of other scholars in the same field as the manuscript's author--in other words, that author's peers. This peer-review process is sometimes called " external review ." These peer scholars offer their view on the quality of the article and its research. How appropriate and exacting was the research method? Were the results presented in the best way possible? Was the literature review thorough? Does the article make a significant contribution to the scholarship of that field? Does it meet the scope of this particular journal? There are many criteria for judgement!

The exact peer-review process will vary between publishers. Additionally, the whole value of peer review, as it now exists, is often hotly debated. Some believe that the Open Access (OA) movement of publishing research on the web and inviting scrutiny and comment will eventually eliminate the need for publisher driven peer-review.

However, as of now, peer-reviewed journal literature is still considered the highest form of scholarship. Also, your professors will likely say that they want you to use peer-reviewed articles in your paper--sometimes exclusively.

Links to Additional Pages That Discuss the Peer Review Process

Here are a few additional web links for discussions of specific processes and the current controversies:

- View a PowerPoint presentation on the process at the BMJ (British Medical Journal) Group.

- One major publisher of scholarly journals is Elsevier (the publisher behind ScienceDirect). Here is a page on their peer review policies. They link to other related articles, blog entries and the like on the bottom half of that page.

- Even to receive a grant to conduct field research, scientists often must go through a peer review. Here is an example of that process from the National Institutes of Health.

Subject Guide

- << Previous: Scholarly Journal vs. Magazine

- Next: Finding Peer-Reviewed Articles >>

- Last Updated: Nov 16, 2022 12:46 PM

- URL: https://suffolk.libguides.com/PeerandPrimary

Understanding peer review

The peer review process.

Peer review is a formal quality control process completed before an academic work is published. Not all academic literature is peer reviewed, but many academic journal articles and books will be. Peer-reviewed literature is sometimes also called “refereed literature”.

“Peer assessment”, where peers and colleagues give general feedback on your work, is sometimes also called peer review. However, “peer review” in published research refers specifically to the process described below.

Researchers who are experts in the same field review the submitted work to see if the research and arguments are sound, original, and of high enough quality to be published. Peer reviewers will provide feedback for the author to incorporate before the article is published, or they may advise that the work is not published at all.

If the peer review process is conducted to a high standard by relevant, respected experts, it can improve the quality of published academic literature and encourage original, high-quality research. However, peer review takes time, which affects how quickly an article can be published. The quality of peer review processes can also vary across publishers and reviewers.

Find peer-reviewed literature

In most cases, you can identify whether an academic work is peer reviewed by looking at the publisher’s website or using a “peer reviewed” filter when searching a database.

Academic journals

Some journals require all research articles to be peer reviewed. You can look up the journal’s website to find out their peer review process. Be aware that other content in these journals, like reviews and editorial pieces, may not be peer reviewed.

Another way to check if a journal has a peer review process is to look it up in a journal directory.

- Search a journal’s International Standard Serial Number (ISSN) or title ( not the article title) and see if it is listed with this black ”refereed” icon.

- Click the journal title for more details and a link to the journal website.

Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ)

- Search for open access journals. Click the journal title in the search results to check for links to their peer review process.

Some academic journal databases will include an option to only search peer-reviewed journals. This option will appear either in their “advanced search” function or as a filter for their results page once you’ve searched. The Library catalogue also has a “peer-reviewed journals” filter on its search results page.

Academic books

Check the book publisher’s website for their review processes. University presses are highly likely to publish peer-reviewed academic books.

If the book is open access, check to see if it’s listed in the Directory of Open Access Books (DOAB) , which only includes scholarly, peer-reviewed books.

Academic books are less likely than academic journals to be clearly identified as peer reviewed in databases. Searching an ebook collection that focuses on research will increase your chances of finding peer-reviewed books.

You can also search for a book’s title in the Library catalogue or an academic journal database to see if other researchers have reviewed it and commented on the book’s peer review process.

Related information

We're here to help, online or in person.

Frequently asked questions

What is the definition of peer review.

Peer review is a process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Utilizing rigorous criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decide whether to accept each submission for publication. For this reason, academic journals are often considered among the most credible sources you can use in a research project– provided that the journal itself is trustworthy and well-regarded.

Frequently asked questions: Citing sources

A scientific citation style is a system of source citation that is used in scientific disciplines. Some commonly used scientific citation styles are:

- Chicago author-date , CSE , and Harvard , used across various sciences

- ACS , used in chemistry

- AMA , NLM , and Vancouver , used in medicine and related disciplines

- AAA , APA , and ASA , commonly used in the social sciences

There are many different citation styles used across different academic disciplines, but they fall into three basic approaches to citation:

- Parenthetical citations : Including identifying details of the source in parentheses —usually the author’s last name and the publication date, plus a page number if available ( author-date ). The publication date is occasionally omitted ( author-page ).

- Numerical citations: Including a number in brackets or superscript, corresponding to an entry in your numbered reference list.

- Note citations: Including a full citation in a footnote or endnote , which is indicated in the text with a superscript number or symbol.

A source annotation in an annotated bibliography fulfills a similar purpose to an abstract : they’re both intended to summarize the approach and key points of a source.

However, an annotation may also evaluate the source , discussing the validity and effectiveness of its arguments. Even if your annotation is purely descriptive , you may have a different perspective on the source from the author and highlight different key points.

You should never just copy text from the abstract for your annotation, as doing so constitutes plagiarism .

Most academics agree that you shouldn’t cite Wikipedia as a source in your academic writing , and universities often have rules against doing so.

This is partly because of concerns about its reliability, and partly because it’s a tertiary source. Tertiary sources are things like encyclopedias and databases that collect information from other sources rather than presenting their own evidence or analysis. Usually, only primary and secondary sources are cited in academic papers.

A Wikipedia citation usually includes the title of the article, “Wikipedia” and/or “Wikimedia Foundation,” the date the article was last updated, and the URL.

In APA Style , you’ll give the URL of the current revision of the article so that you’re sure the reader accesses the same version as you.

There’s some disagreement about whether Wikipedia can be considered a reliable source . Because it can be edited by anyone, many people argue that it’s easy for misleading information to be added to an article without the reader knowing.

Others argue that because Wikipedia articles cite their sources , and because they are worked on by so many editors, misinformation is generally removed quickly.

However, most universities state that you shouldn’t cite Wikipedia in your writing.

Hanging indents are used in reference lists in various citation styles to allow the reader to easily distinguish between entries.

You should apply a hanging indent to your reference entries in APA , MLA , and Chicago style.

A hanging indent is used to indent all lines of a paragraph except the first.

When you create a hanging indent, the first line of the paragraph starts at the border. Each subsequent line is indented 0.5 inches (1.27 cm).

APA and MLA style both use parenthetical in-text citations to cite sources and include a full list of references at the end, but they differ in other ways:

- APA in-text citations include the author name, date, and page number (Taylor, 2018, p. 23), while MLA in-text citations include only the author name and page number (Taylor 23).

- The APA reference list is titled “References,” while MLA’s version is called “ Works Cited .”

- The reference entries differ in terms of formatting and order of information.

- APA requires a title page , while MLA requires a header instead.

A parenthetical citation in Chicago author-date style includes the author’s last name, the publication date, and, if applicable, the relevant page number or page range in parentheses . Include a comma after the year, but not after the author’s name.

For example: (Swan 2003, 6)

To automatically generate accurate Chicago references, you can use Scribbr’s free Chicago reference generator .

APA Style distinguishes between parenthetical and narrative citations.

In parenthetical citations , you include all relevant source information in parentheses at the end of the sentence or clause: “Parts of the human body reflect the principles of tensegrity (Levin, 2002).”

In narrative citations , you include the author’s name in the text itself, followed by the publication date in parentheses: “Levin (2002) argues that parts of the human body reflect the principles of tensegrity.”

In a parenthetical citation in MLA style , include the author’s last name and the relevant page number or range in parentheses .

For example: (Eliot 21)

A parenthetical citation gives credit in parentheses to a source that you’re quoting or paraphrasing . It provides relevant information such as the author’s name, the publication date, and the page number(s) cited.

How you use parenthetical citations will depend on your chosen citation style . It will also depend on the type of source you are citing and the number of authors.

APA does not permit the use of ibid. This is because APA in-text citations are parenthetical and there’s no need to shorten them further.

Ibid. may be used in Chicago footnotes or endnotes .

Write “Ibid.” alone when you are citing the same page number and source as the previous citation.

When you are citing the same source, but a different page number, use ibid. followed by a comma and the relevant page number(s). For example:

- Ibid., 40–42.

Only use ibid . if you are directing the reader to a previous full citation of a source .

Ibid. only refers to the previous citation. Therefore, you should only use ibid. directly after a citation that you want to repeat.

Ibid. is an abbreviation of the Latin “ibidem,” meaning “in the same place.” Ibid. is used in citations to direct the reader to the previous source.

Signal phrases can be used in various ways and can be placed at the beginning, middle, or end of a sentence.

To use signal phrases effectively, include:

- The name of the scholar(s) or study you’re referencing

- An attributive tag such as “according to” or “argues that”

- The quote or idea you want to include

Different citation styles require you to use specific verb tenses when using signal phrases.

- APA Style requires you to use the past or present perfect tense when using signal phrases.

- MLA and Chicago requires you to use the present tense when using signal phrases.

Signal phrases allow you to give credit for an idea or quote to its author or originator. This helps you to:

- Establish the credentials of your sources

- Display your depth of reading and understanding of the field

- Position your own work in relation to other scholars

- Avoid plagiarism

A signal phrase is a group of words that ascribes a quote or idea to an outside source.

Signal phrases distinguish the cited idea or argument from your own writing and introduce important information including the source of the material that you are quoting , paraphrasing , or summarizing . For example:

“ Cognitive psychologist Steven Pinker (1994) insists that humans possess an innate faculty for comprehending grammar.”

If you’re quoting from a text that paraphrases or summarizes other sources and cites them in parentheses , APA and Chicago both recommend retaining the citations as part of the quote. However, MLA recommends omitting citations within a quote:

- APA: Smith states that “the literature on this topic (Jones, 2015; Sill, 2019; Paulson, 2020) shows no clear consensus” (Smith, 2019, p. 4).

- MLA: Smith states that “the literature on this topic shows no clear consensus” (Smith, 2019, p. 4).

Footnote or endnote numbers that appear within quoted text should be omitted in all styles.

If you want to cite an indirect source (one you’ve only seen quoted in another source), either locate the original source or use the phrase “as cited in” in your citation.

In scientific subjects, the information itself is more important than how it was expressed, so quoting should generally be kept to a minimum. In the arts and humanities, however, well-chosen quotes are often essential to a good paper.

In social sciences, it varies. If your research is mainly quantitative , you won’t include many quotes, but if it’s more qualitative , you may need to quote from the data you collected .

As a general guideline, quotes should take up no more than 5–10% of your paper. If in doubt, check with your instructor or supervisor how much quoting is appropriate in your field.

To present information from other sources in academic writing , it’s best to paraphrase in most cases. This shows that you’ve understood the ideas you’re discussing and incorporates them into your text smoothly.

It’s appropriate to quote when:

- Changing the phrasing would distort the meaning of the original text

- You want to discuss the author’s language choices (e.g., in literary analysis )

- You’re presenting a precise definition

- You’re looking in depth at a specific claim

To paraphrase effectively, don’t just take the original sentence and swap out some of the words for synonyms. Instead, try:

- Reformulating the sentence (e.g., change active to passive , or start from a different point)

- Combining information from multiple sentences into one

- Leaving out information from the original that isn’t relevant to your point

- Using synonyms where they don’t distort the meaning

The main point is to ensure you don’t just copy the structure of the original text, but instead reformulate the idea in your own words.

“ Et al. ” is an abbreviation of the Latin term “et alia,” which means “and others.” It’s used in source citations to save space when there are too many authors to name them all.

Guidelines for using “et al.” differ depending on the citation style you’re following:

To insert endnotes in Microsoft Word, follow the steps below:

- Click on the spot in the text where you want the endnote to show up.

- In the “References” tab at the top, select “Insert Endnote.”

- Type whatever text you want into the endnote.

If you need to change the type of notes used in a Word document from footnotes to endnotes , or the other way around, follow these steps:

- Open the “References” tab, and click the arrow in the bottom-right corner of the “Footnotes” section.

- In the pop-up window, click on “Convert…”

- Choose the option you need, and click “OK.”

To insert a footnote automatically in a Word document:

- Click on the point in the text where the footnote should appear

- Select the “References” tab at the top and then click on “Insert Footnote”

- Type the text you want into the footnote that appears at the bottom of the page

Footnotes are notes indicated in your text with numbers and placed at the bottom of the page. They’re used to provide:

- Citations (e.g., in Chicago notes and bibliography )

- Additional information that would disrupt the flow of the main text

Be sparing in your use of footnotes (other than citation footnotes), and consider whether the information you’re adding is relevant for the reader.

Footnotes appear at the bottom of the page they refer to. This is convenient for the reader but may cause your text to look cluttered if there are a lot of footnotes.

Endnotes appear all together at the end of the whole text. This may be less convenient for the reader but reduces clutter.

Both footnotes and endnotes are used in the same way: to cite sources or add extra information. You should usually choose one or the other to use in your text, not both.

An in-text citation is an acknowledgement you include in your text whenever you quote or paraphrase a source. It usually gives the author’s last name, the year of publication, and the page number of the relevant text. In-text citations allow the reader to look up the full source information in your reference list and see your sources for themselves.

If you are reusing content or data you used in a previous assignment, make sure to cite yourself. You can cite yourself just as you would cite any other source: simply follow the directions for that source type in the citation style you are using.

Keep in mind that reusing your previous work can be considered self-plagiarism , so make sure you ask your professor or consult your university’s handbook before doing so.

A credible source should pass the CRAAP test and follow these guidelines:

- The information should be up to date and current.

- The author and publication should be a trusted authority on the subject you are researching.

- The sources the author cited should be easy to find, clear, and unbiased.

- For a web source, the URL and layout should signify that it is trustworthy.

Academic dishonesty can be intentional or unintentional, ranging from something as simple as claiming to have read something you didn’t to copying your neighbor’s answers on an exam.

You can commit academic dishonesty with the best of intentions, such as helping a friend cheat on a paper. Severe academic dishonesty can include buying a pre-written essay or the answers to a multiple-choice test, or falsifying a medical emergency to avoid taking a final exam.

Academic dishonesty refers to deceitful or misleading behavior in an academic setting. Academic dishonesty can occur intentionally or unintentionally, and varies in severity.

It can encompass paying for a pre-written essay, cheating on an exam, or committing plagiarism . It can also include helping others cheat, copying a friend’s homework answers, or even pretending to be sick to miss an exam.

Academic dishonesty doesn’t just occur in a classroom setting, but also in research and other academic-adjacent fields.

To apply a hanging indent to your reference list or Works Cited list in Word or Google Docs, follow the steps below.

Microsoft Word:

- Highlight the whole list and right click to open the Paragraph options.

- Under Indentation > Special , choose Hanging from the dropdown menu.

- Set the indent to 0.5 inches or 1.27cm.

Google Docs:

- Highlight the whole list and click on Format > Align and indent > Indentation options .

- Under Special indent , choose Hanging from the dropdown menu.

When the hanging indent is applied, for each reference, every line except the first is indented. This helps the reader see where one entry ends and the next begins.

For a published interview (whether in video , audio, or print form ), you should always include a citation , just as you would for any other source.

For an interview you conducted yourself , formally or informally, you often don’t need a citation and can just refer to it in the text or in a footnote , since the reader won’t be able to look them up anyway. MLA , however, still recommends including citations for your own interviews.

The main elements included in a newspaper interview citation across APA , MLA , and Chicago style are the names of the interviewer and interviewee, the interview title, the publication date, the name of the newspaper, and a URL (for online sources).

The information is presented differently in different citation styles. One key difference is that APA advises listing the interviewer in the author position, while MLA and Chicago advise listing the interviewee first.

The elements included in a newspaper article citation across APA , MLA , and Chicago style are the author name, the article title, the publication date, the newspaper name, and the URL if the article was accessed online .

In APA and MLA, the page numbers of the article appear in place of the URL if the article was accessed in print. No page numbers are used in Chicago newspaper citations.

Untitled sources (e.g. some images ) are usually cited using a short descriptive text in place of the title. In APA Style , this description appears in brackets: [Chair of stained oak]. In MLA and Chicago styles, no brackets are used: Chair of stained oak.

For social media posts, which are usually untitled, quote the initial words of the post in place of the title: the first 160 characters in Chicago , or the first 20 words in APA . E.g. Biden, J. [@JoeBiden]. “The American Rescue Plan means a $7,000 check for a single mom of four. It means more support to safely.”

MLA recommends quoting the full post for something short like a tweet, and just describing the post if it’s longer.

The main elements included in image citations across APA , MLA , and Chicago style are the name of the image’s creator, the image title, the year (or more precise date) of publication, and details of the container in which the image was found (e.g. a museum, book , website ).

In APA and Chicago style, it’s standard to also include a description of the image’s format (e.g. “Photograph” or “Oil on canvas”). This sort of information may be included in MLA too, but is not mandatory.

The main elements included in a lecture citation across APA , MLA , and Chicago style are the name of the speaker, the lecture title, the date it took place, the course or event it was part of, and the institution it took place at.

For transcripts or recordings of lectures/speeches, other details like the URL, the name of the book or website , and the length of the recording may be included instead of information about the event and institution.

The main elements included in a YouTube video citation across APA , MLA , and Chicago style are the name of the author/uploader, the title of the video, the publication date, and the URL.

The format in which this information appears is different for each style.

All styles also recommend using timestamps as a locator in the in-text citation or Chicago footnote .

Each annotation in an annotated bibliography is usually between 50 and 200 words long. Longer annotations may be divided into paragraphs .

The content of the annotation varies according to your assignment. An annotation can be descriptive, meaning it just describes the source objectively; evaluative, meaning it assesses its usefulness; or reflective, meaning it explains how the source will be used in your own research .

Any credible sources on your topic can be included in an annotated bibliography . The exact sources you cover will vary depending on the assignment, but you should usually focus on collecting journal articles and scholarly books . When in doubt, utilize the CRAAP test !

An annotated bibliography is an assignment where you collect sources on a specific topic and write an annotation for each source. An annotation is a short text that describes and sometimes evaluates the source.

The elements included in journal article citations across APA , MLA , and Chicago style are the name(s) of the author(s), the title of the article, the year of publication, the name of the journal, the volume and issue numbers, the page range of the article, and, when accessed online, the DOI or URL.

In MLA and Chicago style, you also include the specific month or season of publication alongside the year, when this information is available.

In APA , MLA , and Chicago style citations for sources that don’t list a specific author (e.g. many websites ), you can usually list the organization responsible for the source as the author.

If the organization is the same as the website or publisher, you shouldn’t repeat it twice in your reference:

- In APA and Chicago, omit the website or publisher name later in the reference.

- In MLA, omit the author element at the start of the reference, and cite the source title instead.

If there’s no appropriate organization to list as author, you will usually have to begin the citation and reference entry with the title of the source instead.

The main elements included in website citations across APA , MLA , and Chicago style are the author, the date of publication, the page title, the website name, and the URL. The information is presented differently in each style.

When you want to cite a specific passage in a source without page numbers (e.g. an e-book or website ), all the main citation styles recommend using an alternate locator in your in-text citation . You might use a heading or chapter number, e.g. (Smith, 2016, ch. 1)

In APA Style , you can count the paragraph numbers in a text to identify a location by paragraph number. MLA and Chicago recommend that you only use paragraph numbers if they’re explicitly marked in the text.

For audiovisual sources (e.g. videos ), all styles recommend using a timestamp to show a specific point in the video when relevant.

The abbreviation “ et al. ” (Latin for “and others”) is used to shorten citations of sources with multiple authors.

“Et al.” is used in APA in-text citations of sources with 3+ authors, e.g. (Smith et al., 2019). It is not used in APA reference entries .

Use “et al.” for 3+ authors in MLA in-text citations and Works Cited entries.

Use “et al.” for 4+ authors in a Chicago in-text citation , and for 10+ authors in a Chicago bibliography entry.

Check if your university or course guidelines specify which citation style to use. If the choice is left up to you, consider which style is most commonly used in your field.

- APA Style is the most popular citation style, widely used in the social and behavioral sciences.

- MLA style is the second most popular, used mainly in the humanities.

- Chicago notes and bibliography style is also popular in the humanities, especially history.

- Chicago author-date style tends to be used in the sciences.

Other more specialized styles exist for certain fields, such as Bluebook and OSCOLA for law.

The most important thing is to choose one style and use it consistently throughout your text.

The main elements included in all book citations across APA , MLA , and Chicago style are the author, the title, the year of publication, and the name of the publisher. A page number is also included in in-text citations to highlight the specific passage cited.

In Chicago style and in the 6th edition of APA Style , the location of the publisher is also included, e.g. London: Penguin.

A block quote is a long quote formatted as a separate “block” of text. Instead of using quotation marks , you place the quote on a new line, and indent the entire quote to mark it apart from your own words.

The rules for when to apply block quote formatting depend on the citation style:

- APA block quotes are 40 words or longer.

- MLA block quotes are more than 4 lines of prose or 3 lines of poetry.

- Chicago block quotes are longer than 100 words.

In academic writing , there are three main situations where quoting is the best choice:

- To analyze the author’s language (e.g., in a literary analysis essay )

- To give evidence from primary sources

- To accurately present a precise definition or argument

Don’t overuse quotes; your own voice should be dominant. If you just want to provide information from a source, it’s usually better to paraphrase or summarize .

Every time you quote a source , you must include a correctly formatted in-text citation . This looks slightly different depending on the citation style .

For example, a direct quote in APA is cited like this: “This is a quote” (Streefkerk, 2020, p. 5).

Every in-text citation should also correspond to a full reference at the end of your paper.

A quote is an exact copy of someone else’s words, usually enclosed in quotation marks and credited to the original author or speaker.

The DOI is usually clearly visible when you open a journal article on an academic database. It is often listed near the publication date, and includes “doi.org” or “DOI:”. If the database has a “cite this article” button, this should also produce a citation with the DOI included.

If you can’t find the DOI, you can search on Crossref using information like the author, the article title, and the journal name.

A DOI is a unique identifier for a digital document. DOIs are important in academic citation because they are more permanent than URLs, ensuring that your reader can reliably locate the source.

Journal articles and ebooks can often be found on multiple different websites and databases. The URL of the page where an article is hosted can be changed or removed over time, but a DOI is linked to the specific document and never changes.

When a book’s chapters are written by different authors, you should cite the specific chapter you are referring to.

When all the chapters are written by the same author (or group of authors), you should usually cite the entire book, but some styles include exceptions to this.

- In APA Style , single-author books should always be cited as a whole, even if you only quote or paraphrase from one chapter.

- In MLA Style , if a single-author book is a collection of stand-alone works (e.g. short stories ), you should cite the individual work.

- In Chicago Style , you may choose to cite a single chapter of a single-author book if you feel it is more appropriate than citing the whole book.

Articles in newspapers and magazines can be primary or secondary depending on the focus of your research.

In historical studies, old articles are used as primary sources that give direct evidence about the time period. In social and communication studies, articles are used as primary sources to analyze language and social relations (for example, by conducting content analysis or discourse analysis ).

If you are not analyzing the article itself, but only using it for background information or facts about your topic, then the article is a secondary source.

A fictional movie is usually a primary source. A documentary can be either primary or secondary depending on the context.

If you are directly analyzing some aspect of the movie itself – for example, the cinematography, narrative techniques, or social context – the movie is a primary source.

If you use the movie for background information or analysis about your topic – for example, to learn about a historical event or a scientific discovery – the movie is a secondary source.

Whether it’s primary or secondary, always properly cite the movie in the citation style you are using. Learn how to create an MLA movie citation or an APA movie citation .

To determine if a source is primary or secondary, ask yourself:

- Was the source created by someone directly involved in the events you’re studying (primary), or by another researcher (secondary)?

- Does the source provide original information (primary), or does it summarize information from other sources (secondary)?

- Are you directly analyzing the source itself (primary), or only using it for background information (secondary)?

Some types of source are nearly always primary: works of art and literature, raw statistical data, official documents and records, and personal communications (e.g. letters, interviews ). If you use one of these in your research, it is probably a primary source.

Primary sources are often considered the most credible in terms of providing evidence for your argument, as they give you direct evidence of what you are researching. However, it’s up to you to ensure the information they provide is reliable and accurate.

Always make sure to properly cite your sources to avoid plagiarism .

Common examples of secondary sources include academic books, journal articles , reviews, essays , and textbooks.

Anything that summarizes, evaluates or interprets primary sources can be a secondary source. If a source gives you an overview of background information or presents another researcher’s ideas on your topic, it is probably a secondary source.

Common examples of primary sources include interview transcripts , photographs, novels, paintings, films, historical documents, and official statistics.

Anything you directly analyze or use as first-hand evidence can be a primary source, including qualitative or quantitative data that you collected yourself.

The Scribbr Citation Generator is developed using the open-source Citation Style Language (CSL) project and Frank Bennett’s citeproc-js . It’s the same technology used by dozens of other popular citation tools, including Mendeley and Zotero.

You can find all the citation styles and locales used in the Scribbr Citation Generator in our publicly accessible repository on Github .

Ask our team

Want to contact us directly? No problem. We are always here for you.

- Email [email protected]

- Start live chat

- Call +1 (510) 822-8066

- WhatsApp +31 20 261 6040

Our team helps students graduate by offering:

- A world-class citation generator

- Plagiarism Checker software powered by Turnitin

- Innovative Citation Checker software

- Professional proofreading services

- Over 300 helpful articles about academic writing, citing sources, plagiarism, and more

Scribbr specializes in editing study-related documents . We proofread:

- PhD dissertations

- Research proposals

- Personal statements

- Admission essays

- Motivation letters

- Reflection papers

- Journal articles

- Capstone projects

Scribbr’s Plagiarism Checker is powered by elements of Turnitin’s Similarity Checker , namely the plagiarism detection software and the Internet Archive and Premium Scholarly Publications content databases .

The add-on AI detector is powered by Scribbr’s proprietary software.

Peer-reviewed journal articles

What is peer review, why use peer-reviewed articles, peer reviewed articles video.

- Scholarly and academic - good enough?

- Find peer-reviewed articles

- Check if it's peer reviewed

Reusing content from this guide

Attribute our work under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Further help

Contact the Librarian team .

Phone: + 617 334 64312 during opening hours

Email: [email protected]

Peer review (also known as refereeing) is a process where other scholars in the same field (peers) evaluate the quality of a research paper before it's published. The aim is to ensure that the work is rigorous and coherent, is based on sound research, and adds to what we already know.

The purpose of peer review is to maintain the integrity of research and to ensure that only valid and quality research is published.

To learn more about the peer review process, visit:

- What is peer review? Comprehensive overview of the peer review process and different types of peer review from Elsevier

Your lecturers will often require you to use information from academic journal articles that are peer reviewed (also known as refereed).

Peer-reviewed articles are credible sources of information. The articles have been written and reviewed by trusted experts in the field, and represent the best scholarship and research currently available.

Explanation of peer reviewed articles and journals (YouTube, 1m51s)

- Next: Scholarly and academic - good enough? >>

- Last Updated: May 28, 2024 2:49 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.uq.edu.au/how-to-find/peer-reviewed-articles

- Library Catalogue

What is peer review? What is a peer-reviewed journal?

Peer-reviewed (or refereed) journals.

Peer-reviewed or refereed journals have an editorial board of subject experts who review and evaluate submitted articles before accepting them for publication. A journal may be a scholarly journal but not a peer-reviewed journal.

Peer review (or referee) process

- An editorial board asks subject experts to review and evaluate submitted articles before accepting them for publication in a scholarly journal.

- Submissions are evaluated using criteria including the excellence, novelty and significance of the research or ideas.

- Scholarly journals use this process to protect and maintain the quality of material they publish.

- Members of the editorial board are listed near the beginning of each journal issue.

How to tell if a journal is peer-reviewed

- If you are searching for scholarly or peer-reviewed articles in a database , you may be able to limit your results to peer-reviewed articles.

- If you're looking at the journal itself, search for references to their peer-review process, such as in an editorial statement, or a section with instructions to authors.

- You can also check the entry for a journal in the Library Catalogue . Many journal records will have a note in the Description section, e.g. to say "Refereed / Peer-reviewed."

For an overview of the different types of journals, see What is a scholarly (or peer-reviewed) journal?

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Reumatologia

- v.59(1); 2021

Peer review guidance: a primer for researchers

Olena zimba.

1 Department of Internal Medicine No. 2, Danylo Halytsky Lviv National Medical University, Lviv, Ukraine

Armen Yuri Gasparyan

2 Departments of Rheumatology and Research and Development, Dudley Group NHS Foundation Trust (Teaching Trust of the University of Birmingham, UK), Russells Hall Hospital, Dudley, West Midlands, UK

The peer review process is essential for quality checks and validation of journal submissions. Although it has some limitations, including manipulations and biased and unfair evaluations, there is no other alternative to the system. Several peer review models are now practised, with public review being the most appropriate in view of the open science movement. Constructive reviewer comments are increasingly recognised as scholarly contributions which should meet certain ethics and reporting standards. The Publons platform, which is now part of the Web of Science Group (Clarivate Analytics), credits validated reviewer accomplishments and serves as an instrument for selecting and promoting the best reviewers. All authors with relevant profiles may act as reviewers. Adherence to research reporting standards and access to bibliographic databases are recommended to help reviewers draft evidence-based and detailed comments.

Introduction

The peer review process is essential for evaluating the quality of scholarly works, suggesting corrections, and learning from other authors’ mistakes. The principles of peer review are largely based on professionalism, eloquence, and collegiate attitude. As such, reviewing journal submissions is a privilege and responsibility for ‘elite’ research fellows who contribute to their professional societies and add value by voluntarily sharing their knowledge and experience.

Since the launch of the first academic periodicals back in 1665, the peer review has been mandatory for validating scientific facts, selecting influential works, and minimizing chances of publishing erroneous research reports [ 1 ]. Over the past centuries, peer review models have evolved from single-handed editorial evaluations to collegial discussions, with numerous strengths and inevitable limitations of each practised model [ 2 , 3 ]. With multiplication of periodicals and editorial management platforms, the reviewer pool has expanded and internationalized. Various sets of rules have been proposed to select skilled reviewers and employ globally acceptable tools and language styles [ 4 , 5 ].

In the era of digitization, the ethical dimension of the peer review has emerged, necessitating involvement of peers with full understanding of research and publication ethics to exclude unethical articles from the pool of evidence-based research and reviews [ 6 ]. In the time of the COVID-19 pandemic, some, if not most, journals face the unavailability of skilled reviewers, resulting in an unprecedented increase of articles without a history of peer review or those with surprisingly short evaluation timelines [ 7 ].

Editorial recommendations and the best reviewers

Guidance on peer review and selection of reviewers is currently available in the recommendations of global editorial associations which can be consulted by journal editors for updating their ethics statements and by research managers for crediting the evaluators. The International Committee on Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) qualifies peer review as a continuation of the scientific process that should involve experts who are able to timely respond to reviewer invitations, submitting unbiased and constructive comments, and keeping confidentiality [ 8 ].

The reviewer roles and responsibilities are listed in the updated recommendations of the Council of Science Editors (CSE) [ 9 ] where ethical conduct is viewed as a premise of the quality evaluations. The Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) further emphasizes editorial strategies that ensure transparent and unbiased reviewer evaluations by trained professionals [ 10 ]. Finally, the World Association of Medical Editors (WAME) prioritizes selecting the best reviewers with validated profiles to avoid substandard or fraudulent reviewer comments [ 11 ]. Accordingly, the Sarajevo Declaration on Integrity and Visibility of Scholarly Publications encourages reviewers to register with the Open Researcher and Contributor ID (ORCID) platform to validate and publicize their scholarly activities [ 12 ].

Although the best reviewer criteria are not listed in the editorial recommendations, it is apparent that the manuscript evaluators should be active researchers with extensive experience in the subject matter and an impressive list of relevant and recent publications [ 13 ]. All authors embarking on an academic career and publishing articles with active contact details can be involved in the evaluation of others’ scholarly works [ 14 ]. Ideally, the reviewers should be peers of the manuscript authors with equal scholarly ranks and credentials.

However, journal editors may employ schemes that engage junior research fellows as co-reviewers along with their mentors and senior fellows [ 15 ]. Such a scheme is successfully practised within the framework of the Emerging EULAR (European League Against Rheumatism) Network (EMEUNET) where seasoned authors (mentors) train ongoing researchers (mentees) how to evaluate submissions to the top rheumatology journals and select the best evaluators for regular contributors to these journals [ 16 ].

The awareness of the EQUATOR Network reporting standards may help the reviewers to evaluate methodology and suggest related revisions. Statistical skills help the reviewers to detect basic mistakes and suggest additional analyses. For example, scanning data presentation and revealing mistakes in the presentation of means and standard deviations often prompt re-analyses of distributions and replacement of parametric tests with non-parametric ones [ 17 , 18 ].

Constructive reviewer comments

The main goal of the peer review is to support authors in their attempt to publish ethically sound and professionally validated works that may attract readers’ attention and positively influence healthcare research and practice. As such, an optimal reviewer comment has to comprehensively examine all parts of the research and review work ( Table I ). The best reviewers are viewed as contributors who guide authors on how to correct mistakes, discuss study limitations, and highlight its strengths [ 19 ].

Structure of a reviewer comment to be forwarded to authors

| Section | Notes |

|---|---|

| Introductory line | Summarizes the overall impression about the manuscript validity and implications |

| Evaluation of the title, abstract and keywords | Evaluates the title correctness and completeness, inclusion of all relevant keywords, study design terms, information load, and relevance of the abstract |

| Major comments | Specifically analyses each manuscript part in line with available research reporting standards, supports all suggestions with solid evidence, weighs novelty of hypotheses and methodological rigour, highlights the choice of study design, points to missing/incomplete ethics approval statements, rights to re-use graphics, accuracy and completeness of statistical analyses, professionalism of bibliographic searches and inclusion of updated and relevant references |

| Minor comments | Identifies language mistakes, typos, inappropriate format of graphics and references, length of texts and tables, use of supplementary material, unusual sections and order, completeness of scholarly contribution, conflict of interest, and funding statements |

| Concluding remarks | Reflects on take-home messages and implications |

Some of the currently practised review models are well positioned to help authors reveal and correct their mistakes at pre- or post-publication stages ( Table II ). The global move toward open science is particularly instrumental for increasing the quality and transparency of reviewer contributions.

Advantages and disadvantages of common manuscript evaluation models

| Models | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| In-house (internal) editorial review | Allows detection of major flaws and errors that justify outright rejections; rarely, outstanding manuscripts are accepted without delays | Journal staff evaluations may be biased; manuscript acceptance without external review may raise concerns of soft quality checks |

| Single-blind peer review | Masking reviewer identity prevents personal conflicts in small (closed) professional communities | Reviewer access to author profiles may result in biased and subjective evaluations |

| Double-blind peer review | Concealing author and reviewer identities prevents biased evaluations, particularly in small communities | Masking all identifying information is technically burdensome and not always possible |

| Open (public) peer review | May increase quality, objectivity, and accountability of reviewer evaluations; it is now part of open science culture | Peers who do not wish to disclose their identity may decline reviewer invitations |

| Post-publication open peer review | May accelerate dissemination of influential reports in line with the concept “publish first, judge later”; this concept is practised by some open-access journals (e.g., F1000 Research) | Not all manuscripts benefit from open dissemination without peers’ input; post-publication review may delay detection of minor or major mistakes |

| Post-publication social media commenting | May reveal some mistakes and misconduct and improve public perception of article implications | Not all communities use social media for commenting and other academic purposes |

Since there are no universally acceptable criteria for selecting reviewers and structuring their comments, instructions of all peer-reviewed journal should specify priorities, models, and expected review outcomes [ 20 ]. Monitoring and reporting average peer review timelines is also required to encourage timely evaluations and avoid delays. Depending on journal policies and article types, the first round of peer review may last from a few days to a few weeks. The fast-track review (up to 3 days) is practised by some top journals which process clinical trial reports and other priority items.

In exceptional cases, reviewer contributions may result in substantive changes, appreciated by authors in the official acknowledgments. In most cases, however, reviewers should avoid engaging in the authors’ research and writing. They should refrain from instructing the authors on additional tests and data collection as these may delay publication of original submissions with conclusive results.

Established publishers often employ advanced editorial management systems that support reviewers by providing instantaneous access to the review instructions, online structured forms, and some bibliographic databases. Such support enables drafting of evidence-based comments that examine the novelty, ethical soundness, and implications of the reviewed manuscripts [ 21 ].

Encouraging reviewers to submit their recommendations on manuscript acceptance/rejection and related editorial tasks is now a common practice. Skilled reviewers may prompt the editors to reject or transfer manuscripts which fall outside the journal scope, perform additional ethics checks, and minimize chances of publishing erroneous and unethical articles. They may also raise concerns over the editorial strategies in their comments to the editors.

Since reviewer and editor roles are distinct, reviewer recommendations are aimed at helping editors, but not at replacing their decision-making functions. The final decisions rest with handling editors. Handling editors weigh not only reviewer comments, but also priorities related to article types and geographic origins, space limitations in certain periods, and envisaged influence in terms of social media attention and citations. This is why rejections of even flawless manuscripts are likely at early rounds of internal and external evaluations across most peer-reviewed journals.

Reviewers are often requested to comment on language correctness and overall readability of the evaluated manuscripts. Given the wide availability of in-house and external editing services, reviewer comments on language mistakes and typos are categorized as minor. At the same time, non-Anglophone experts’ poor language skills often exclude them from contributing to the peer review in most influential journals [ 22 ]. Comments should be properly edited to convey messages in positive or neutral tones, express ideas of varying degrees of certainty, and present logical order of words, sentences, and paragraphs [ 23 , 24 ]. Consulting linguists on communication culture, passing advanced language courses, and honing commenting skills may increase the overall quality and appeal of the reviewer accomplishments [ 5 , 25 ].

Peer reviewer credits

Various crediting mechanisms have been proposed to motivate reviewers and maintain the integrity of science communication [ 26 ]. Annual reviewer acknowledgments are widely practised for naming manuscript evaluators and appreciating their scholarly contributions. Given the need to weigh reviewer contributions, some journal editors distinguish ‘elite’ reviewers with numerous evaluations and award those with timely and outstanding accomplishments [ 27 ]. Such targeted recognition ensures ethical soundness of the peer review and facilitates promotion of the best candidates for grant funding and academic job appointments [ 28 ].

Also, large publishers and learned societies issue certificates of excellence in reviewing which may include Continuing Professional Development (CPD) points [ 29 ]. Finally, an entirely new crediting mechanism is proposed to award bonus points to active reviewers who may collect, transfer, and use these points to discount gold open-access charges within the publisher consortia [ 30 ].

With the launch of Publons ( http://publons.com/ ) and its integration with Web of Science Group (Clarivate Analytics), reviewer recognition has become a matter of scientific prestige. Reviewers can now freely open their Publons accounts and record their contributions to online journals with Digital Object Identifiers (DOI). Journal editors, in turn, may generate official reviewer acknowledgments and encourage reviewers to forward them to Publons for building up individual reviewer and journal profiles. All published articles maintain e-links to their review records and post-publication promotion on social media, allowing the reviewers to continuously track expert evaluations and comments. A paid-up partnership is also available to journals and publishers for automatically transferring peer-review records to Publons upon mutually acceptable arrangements.

Listing reviewer accomplishments on an individual Publons profile showcases scholarly contributions of the account holder. The reviewer accomplishments placed next to the account holders’ own articles and editorial accomplishments point to the diversity of scholarly contributions. Researchers may establish links between their Publons and ORCID accounts to further benefit from complementary services of both platforms. Publons Academy ( https://publons.com/community/academy/ ) additionally offers an online training course to novice researchers who may improve their reviewing skills under the guidance of experienced mentors and journal editors. Finally, journal editors may conduct searches through the Publons platform to select the best reviewers across academic disciplines.

Peer review ethics

Prior to accepting reviewer invitations, scholars need to weigh a number of factors which may compromise their evaluations. First of all, they are required to accept the reviewer invitations if they are capable of timely submitting their comments. Peer review timelines depend on article type and vary widely across journals. The rules of transparent publishing necessitate recording manuscript submission and acceptance dates in article footnotes to inform readers of the evaluation speed and to help investigators in the event of multiple unethical submissions. Timely reviewer accomplishments often enable fast publication of valuable works with positive implications for healthcare. Unjustifiably long peer review, on the contrary, delays dissemination of influential reports and results in ethical misconduct, such as plagiarism of a manuscript under evaluation [ 31 ].

In the times of proliferation of open-access journals relying on article processing charges, unjustifiably short review may point to the absence of quality evaluation and apparently ‘predatory’ publishing practice [ 32 , 33 ]. Authors when choosing their target journals should take into account the peer review strategy and associated timelines to avoid substandard periodicals.

Reviewer primary interests (unbiased evaluation of manuscripts) may come into conflict with secondary interests (promotion of their own scholarly works), necessitating disclosures by filling in related parts in the online reviewer window or uploading the ICMJE conflict of interest forms. Biomedical reviewers, who are directly or indirectly supported by the pharmaceutical industry, may encounter conflicts while evaluating drug research. Such instances require explicit disclosures of conflicts and/or rejections of reviewer invitations.

Journal editors are obliged to employ mechanisms for disclosing reviewer financial and non-financial conflicts of interest to avoid processing of biased comments [ 34 ]. They should also cautiously process negative comments that oppose dissenting, but still valid, scientific ideas [ 35 ]. Reviewer conflicts that stem from academic activities in a competitive environment may introduce biases, resulting in unfair rejections of manuscripts with opposing concepts, results, and interpretations. The same academic conflicts may lead to coercive reviewer self-citations, forcing authors to incorporate suggested reviewer references or face negative feedback and an unjustified rejection [ 36 ]. Notably, several publisher investigations have demonstrated a global scale of such misconduct, involving some highly cited researchers and top scientific journals [ 37 ].

Fake peer review, an extreme example of conflict of interest, is another form of misconduct that has surfaced in the time of mass proliferation of gold open-access journals and publication of articles without quality checks [ 38 ]. Fake reviews are generated by manipulating authors and commercial editing agencies with full access to their own manuscripts and peer review evaluations in the journal editorial management systems. The sole aim of these reviews is to break the manuscript evaluation process and to pave the way for publication of pseudoscientific articles. Authors of these articles are often supported by funds intended for the growth of science in non-Anglophone countries [ 39 ]. Iranian and Chinese authors are often caught submitting fake reviews, resulting in mass retractions by large publishers [ 38 ]. Several suggestions have been made to overcome this issue, with assigning independent reviewers and requesting their ORCID IDs viewed as the most practical options [ 40 ].

Conclusions

The peer review process is regulated by publishers and editors, enforcing updated global editorial recommendations. Selecting the best reviewers and providing authors with constructive comments may improve the quality of published articles. Reviewers are selected in view of their professional backgrounds and skills in research reporting, statistics, ethics, and language. Quality reviewer comments attract superior submissions and add to the journal’s scientific prestige [ 41 ].

In the era of digitization and open science, various online tools and platforms are available to upgrade the peer review and credit experts for their scholarly contributions. With its links to the ORCID platform and social media channels, Publons now offers the optimal model for crediting and keeping track of the best and most active reviewers. Publons Academy additionally offers online training for novice researchers who may benefit from the experience of their mentoring editors. Overall, reviewer training in how to evaluate journal submissions and avoid related misconduct is an important process, which some indexed journals are experimenting with [ 42 ].

The timelines and rigour of the peer review may change during the current pandemic. However, journal editors should mobilize their resources to avoid publication of unchecked and misleading reports. Additional efforts are required to monitor published contents and encourage readers to post their comments on publishers’ online platforms (blogs) and other social media channels [ 43 , 44 ].

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

- Richard G. Trefry Library

Q. What does "peer reviewed" mean?

- Course-Specific

- Textbooks & Course Materials

- Tutoring & Classroom Help

- Writing & Citing

- 44 Articles & Journals

- 4 Artificial Intelligence

- 11 Capstone/Thesis/Dissertation Research

- 37 Databases

- 56 Information Literacy

- 9 Interlibrary Loan

- 9 Need help getting started?

- 22 Technical Help

Answered By: Priscilla Coulter Last Updated: Jul 29, 2022 Views: 285649

Essentially, peer review is an academic term for quality control . Each article published in a peer-reviewed journal was closely examined by a panel of reviewers who are experts on the article's topic (that is, the author’s professional peers…hence the term peer review). The reviewers assess the author’s proper use of research methods, the significance of the paper’s contribution to the existing literature, and check on the authors’ works on the topic in any discussions or mentions in citations. Papers published in these journals are expert-approved…and the most authoritative sources of information for college-level research papers.

Articles from popula r publications, on the other hand (like magazines, newspapers, or many sites on the Internet), are published with minimal editing (for spelling and grammar, perhaps; but, typically not for factual accuracy or intellectual integrity). While interesting to read, these articles aren’t sufficient to support research at an academic level.

But, with so many articles out there, how do you know which are peer-reviewed?

- Searching the library’s databases can save you a lot of time …allowing you to limit your search to scholarly or peer-reviewed articles only . Most internet search engines (like Google and Yahoo) can’t do this for you, leaving you to determine for yourself which of those thousands of articles are peer-reviewed.

- If you’ve already found an article that you’d like to use in a research paper, but you’re not sure if it’s popular or scholarly, there are ways to tell. The table below lists some of the most obvious clues (but your librarians will be happy to help you figure it out as well).

See also: What does "scholarly" mean? Is it the same as "peer-reviewed?"

|

|

|

| Authors’ names are given, and occasionally some biographical information, but (degrees, professional status, expertise). You may be left wondering if the author is really an expert on the topic he or she is writing about. | are almost always included (so that interested researchers can correspond). . |

| Articles are written for a using everyday language (any technical terms will be explained). People of all ages and/or levels of knowledge could read these. Usually written in a more . | Papers are (or college students!) in the field (lots of which is seldom defined). Always written in a . |

| Articles may have or news…or may even reflect the authors’ (without support from data or literature). | Papers typically report, in , the authors’ (and include support from other research)…these papers will be more than just 1 or 2 pages. |

| Authors , and don’t include a list of references at the end of the article. | Authors always throughout the paper and include a list of (a bibliography or works cited page) at the end. |

| Articles typically include many (often pretty to look at). | Papers seldom include photographs, but may include (may seem bland at a glance). |

| The journal has an editor, but , or peer-review process. | The journal has very (often this information can be found on the journal’s website), and a rigorous peer-review process (each paper will list when it was submitted to the reviewers, and when it was accepted for publication…often several months apart!). |

Need a visual? Watch this quick video from the North Carolina State University Libraries:

- Share on Facebook

Was this helpful? Yes 10066 No 5

Related Topics

- Articles & Journals

- Information Literacy

Need personalized help? Librarians are available 365 days/nights per year! See our schedule.

Learn more about how librarians can help you succeed.

How to Recognize Peer-Reviewed (Refereed) Journals

Find all the information you need on recognizing and citing sources for your research papers.

In many cases, professors will require that students utilize articles from “peer-reviewed” journals. Sometimes the phrases “refereed journals” or “scholarly journals” are used to describe the same type of journals. But what are peer-reviewed (or refereed or scholarly) journal articles, and why do faculty require their use?

Popular, Trade and Scholarly Information

- “Popular” newspapers and magazines containing news - Articles are written by reporters who may or may not be experts in the field of the article. Consequently, articles may contain incorrect information.

- Journals containing articles written by professionals and/or academics - Some trade or academic journals have articles that are written by a single person with little review. Although the articles are written by “experts,” any particular “expert” may have some ideas that are really “out there!”