Bringing rich technical talent and experience to bear on the persistent and emerging challenges of the developing world.

Reverse innovation: why it fails, and how it can succeed.

“The reverse innovation process succeeds when engineering creatively intersects with strategy,” writes Amos Winter in the Harvard Business Review.

Reverse innovation is a term coined by Vijay Govindarajan to describe the phenomenon of goods and services being produced in emerging markets (such as India) and then exported, with a few “tweaks,” to developed markets such as Europe and the United States.

This goes against the grain of a traditional system in which products and technologies and created by, and primarily for, the developed world. Govindarajan has argued that reverse innovation encourages–even enforces–better, more cost-effective design. And while numerous large corporations want to use this technique to improve their ability to design for a global market, few have truly succeeded.

In a new article published by Harvard Business Review , Govindarajan and Tata Center faculty member Amos Winter write that reverse innovation “allows companies to enjoy the best of both worlds,” but only if they do it right.

In that spirit, Winter and Govindarajan lay out five “traps” that businesses routinely fall into, along with corresponding design principles to avoid those mistakes. For example, many companies try to “reduce the price by eliminating features.” Instead, Winter and Govindarajan argue they should “create an optimal solution, not a watered-down one, using the design freedoms available in emerging markets.”

The challenge is strict: “To win over consumers in developing countries, multinationals’ products and services must match or beat the performance of existing ones but at a lower cost. In other words, they must provide 100% of the performance at 10% of the price, as product developers wryly put it.”

Winter, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at MIT and director of GEAR Lab, is no stranger to this kind of innovation. He spent six years designing the Leveraged Freedom Chair, a high-performance, low-cost wheelchair used in both India and the United States. Working with Tata Fellows, he is leading projects on water desalination , high-performance prosthetic limbs , design of tractors for small-scale farming , and more.

He and Govindarajan caution that many companies “still don’t realize that [the business world’s] center of gravity has pretty much shifted to emerging markets.” If they don’t figure out how to reach consumers there, the authors argue, they’re going to get left behind.

Full article in the Harvard Business Review

Photo: Amos Winter with a user of the Leveraged Freedom Chair in India.

- Harvard Business School →

- Faculty & Research →

- Research Summary

Reverse Innovation

Description.

VG and Chris Trimble reveal a bold discovery with far-reaching implications in REVERSE INNOVATION: Create Far From Home, Win Everywhere (Harvard Business Review Press; April 10, 2012; Foreword by Indra Nooyi): innovation flows uphill and its future lies in emerging markets.

Most global companies recognize that emerging markets have become today's last source of growth. But all they do is modify and export products that they developed in their home country. To capitalize on the full potential of emerging markets, they must head in the opposite direction - by innovating specifically for and in developing countries to create breakthroughs that will be adopted next at home and around the globe.

Today's poor countries are being tapped for breakthrough innovations that can unlock new markets in the rich world, and can even help solve its societal problems such as high cost - and poor access - to healthcare.

The book originated in 2008, when VG was chosen by CEO Jeffrey Immelt to advise GE on innovation as their first Professor-in-Residence and Chief Innovation Consultant. In these pages are an inside account of how reverse innovation is transforming GE's strategy, and secen additional in-depth case studies based on original interviews with senior leaders. They include:

- PepsiCo , which drew upon local teams and global resources to develop Aliva, a new savory cracker created by Indians for the Indian market, but with high global potential.

- Before employing reverse innovation, Logitech almost lost leadership of computer mice in China to an unexpected Chinese rival with a better understanding of local needs.

- P&G , which developed a globally successful tampon called Naturella in Mexico after discovering why its American product Always was losing market share to rivals there.

- In China and India, Harman designed from scratch a completely new infotainment system for emerging markets with functionality similar to their high-end products at half the price and one-third the cost . It has generated more than $3 billion in new business.

As these examples show, the biggest hurdles to reverse innovation are not scientific, technical, or budgetary. they ae managerial and organizational, and with the right mindset and tools can be overcome by any manager. Better yet, the evidence shows that companies can earn the same or even better margins and return on investment for a low-cost product designed for China or India than for a higher cost current product at home. The result is a win-win at home and abroad.

"Govindarajan and Trimble offer a framework for the next phase of globalization." - Jeffrey R. Immelt , Chairman of the Board and Chief Executive Officer , General Electric

"Reverse Innovation is a playbook for leaders who want to unlock growth in emerging markets." - Robert A. McDonald , Chairman of the Board, President and Chief Executive Officer, The Procter & Gamble Company

Advertisement

Reverse innovation: a conceptual framework

- Conceptual/Theoretical Paper

- Published: 11 November 2019

- Volume 48 , pages 1009–1029, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Suresh Malodia 1 ,

- Shaphali Gupta 1 , 2 &

- Anand Kumar Jaiswal 3

17k Accesses

29 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Reverse innovation (RI) has emerged as a new growth strategy for MNCs to innovate in emerging markets and then to further exploit the profit potential of such innovations by subsequently introducing them not only in other similar markets but also in developed markets, thereby delivering MNCs a sustainable growth globally. In this study, we propose an overarching conceptual framework to describe factors that contribute to the feasibility of RIs. Using grounded theory with a triangulation approach, we define RI as a multidimensional construct, identify the antecedents of RI, discuss the outcomes, and propose a set of moderating variables contributing to the success of RIs. We also present a set of research propositions with their relative effects on the relationships proposed in the conceptual framework. Additionally, we provide future research directions and discuss theoretical contributions along with managerial implications to realize the strategic goals of RI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Barriers and Facilitators of Reverse Innovation: An Integrative Review

Reverse Innovation in Emerging Markets

How social innovations spread globally through the process of reverse innovation: a case-study from the South Korea

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Multinational corporations (MNCs) are increasingly facing market stagnation, financial instability, and recession in developed economies. At the same time, the large, growing, and untapped customer base in emerging markets has attracted the attention of these MNCs which are seeking sustainable growth and new market opportunities (London and Hart 2004 ). However, the glocalization approach alone cannot yield the desired results. Firms are required to comprehend the peculiar need of the given market (emerging or/and BoP) to develop successful inroads leading to sustainable business outcomes (Govindarajan and Trimble 2012a , b ; London and Hart 2004 ). Creating or innovating the products addressing the needs of this market is suggested to be an appropriate strategy for MNCs to capture the value in these peculiar markets (Brown and Hegel 2005 ; Hart and Christensen 2002 ). In fact, such innovations not only gain traction in emerging markets but also receive acceptance in developed markets for the value they deliver in terms of cost and performance effectiveness (Govindarajan and Trimble 2012b ). The phenomenon whereby an innovation designed for/in emerging markets gets adopted in developed markets is commonly known as reverse innovation (RI) (Immelt et al. 2009 ). For example RIs such as the handheld ECG machine, lullaby baby warmer, and the Discovery IQ PET/CT scanner were first developed by an MNC (GE India) in an emerging market, and they not only were successfully diffused and adopted in India and China but also received significant success when launched in developed markets.

Though RI has been a topic of conversation among academicians and practitioners, it is only recently that RI has achieved visibility in the global marketplace. However, since few MNCs become involved in the process of RI, it is understandable that before any firm can deep-dive into the RI process, a thorough understanding around RI as a phenomenon is necessary. The RI literature is evolving but has remained fragmented and disjointed regarding the factors affecting RI. Extant studies also remain equivocal on whether RI is an outcome or a goal to be achieved (Furue and Washida 2014 ). However, little knowledge is available on the complete process of RI which can be leveraged by MNCs to gain from this phenomenon (Von Zedtwitz et al. 2015 ). Also, given the limited availability of RI evidence, the literature is anecdotal, ultimately falling short in explaining the underlying dimensions of RI and defining it as a construct (Furue and Washida 2014 ). There is also a need to understand the drivers which will provide a conducive environment to stimulate RI in the firm. Also, a clear understanding of the expected outcomes is critical for initiating the RI process. Given these constraints experienced by MNCs while operating their business in a global marketplace, it is imperative to discuss the boundary conditions associated with RI.

To address these available gaps in the literature and the constraints experienced by firms, this study, employing a grounded theory approach, attempts to propose a conceptual framework for RI, define RI as a second-order construct, and identify antecedents, outcomes, and moderators. This study not only enhances the understanding around RI but also broadens the concept of RI as a multidimensional construct. Further, this study presents theoretical propositions regarding the determinants and strategic outcomes of RI, thereby providing implications to managers.

While proposing RI as a multidimensional construct, this study defines RI as clean slate, super value products that are technologically advanced created to meet the unique needs of relevant segments, initially adopted in the emerging markets followed by the developed countries. We recognize that as a process, fugal or local innovations would occur first in emerging markets, and subsequently RI would occur in developed markets. Although a large number of frugal/local innovations occur in emerging markets, only a few become RI. Further, a given frugal/local innovation may fail in emerging markets, but it can potentially be accepted in developed markets and become successful RI. The focus of our study remains on developing a conceptual framework of RI and identifying its determinants, consequences, and moderators.

We present our research as follows: First, we provide a review of the literature discussing the roots of the globalization of innovation and developing an understanding around RI. Then we explain the qualitative study (interviews and marketplace evidence) used for this study. Based on the grounded theory, incorporating the triangulation approach, we conceptualize RI explaining the underlying dimensions. Further, we propose a conceptual framework along with testable propositions followed by implications for firms and, finally, we provide future research directions.

Related literature

The onset of the twenty-first century witnessed a growing number of innovations coming out of emerging markets that eventually disrupted advanced markets (Brown and Hegel 2005 ; Hart and Christensen 2002 ; London and Hart 2004 ). Several factors such as the underserved large markets, growing purchasing power, and a greater talent pool contributed to shifting the loci of innovations gradually towards emerging markets. Perceived opportunities in emerging markets, in addition to the distinctiveness of market conditions and demand in these markets, encouraged MNCs to think of these markets as a place where innovation could take place (Birkinshaw and Hood 2001 ; Cantwell 1995 ). In an effort to comprehend the evolution of the innovation literature in the globalization context, especially occurring in the emerging market space, we attempt to capture various concepts evolved over the past few decades that explain the phenomenon of such innovations in the context of emerging markets and international business. We first discuss innovation concepts that are argued to be similar to RI and differentiate them from our conceptualization. Subsequently, we discuss the literature that explores RI to establish the gaps in the literature.

The emerging phenomenon of innovations originating from emerging markets, focusing on regular customers or specially bottom of the pyramid (BoP) customers, has been termed differently by different scholars. Bower and Christensen ( 1995 ) developed the theory of disruptive innovations, defining them as low-cost, cheaper alternatives to a premium product that is significantly lower in performance but still meets the basic need. Hart and Christensen ( 2002 ) referred to the disruptive innovations coming out of emerging markets as a “great leap.” Prahalad ( 2004 ) proposed the concept of “trickle up innovations” and defined them as innovations developed for BoP markets that later find their way to developed markets. Brown and Hegel ( 2005 ) proposed the concept of blowback innovations and defined them as innovations carried out by multinational enterprises from developed markets (DMNEs) in response to the competition created by multinational enterprises from emerging markets (EMNEs). Immelt et al. ( 2009 ) introduced the concept of RI, and explained the phenomenon by positioning RI as distinct from other innovations.

In this study, for better clarity around RI, we present a comparative analysis of RI with above discussed emerging market-based innovations. Table 1 concisely presents the comparison of all the pertinent innovation terms with RI. Likewise, there exist a few other innovation categories, such as grassroots innovation, social innovation, and jugaad innovation, which also originate in emerging markets to cater to the needs of either emerging markets generally or BoP customers specifically, therefore exhibiting some characteristic overlaps with RI (Gupta 2019 ; Gupta et al. 2019 ). However, the prevailing differences between these innovations are succinctly captured in Gupta et al. ( 2019 ) and Gupta ( 2019 ).

The concept of RI, coined by Immelt et al. ( 2009 ), was first introduced as antithetical to the concept of glocalization and a tool to pre-empt possible competition from emerging market competitors in developed markets. With an increase in the supply of technology and skills needed for innovations, domestic firms in emerging markets are likely to pose a severe competitive threat to MNCs from developed markets and hence would force MNCs to localize their R&D process to remain competitive (Corsi and Di Minin 2014 ; Govindarajan and Ramamurti 2011 ). Using examples from GE Healthcare, Immelt et al. ( 2009 ) provided anecdotal evidence highlighting the significance of factors such as investing in localized R&D centers, country-specific organizational structure, and financial autonomy. RIs coming out of GE’s Indian and Chinese subsidiaries were not only break-through for the local markets but were also successfully commercialized in developed markets. Govindarajan and Trimble ( 2012a , b ) further presented the adoption sequence as an important condition for defining RI and explained that RIs are first adopted in emerging markets and later flow back to developed markets. Von Zedtwitz et al. ( 2015 ) extended the discussion on the reversal of adoption of innovation and argued that reversal may happen at any stage during the innovation process, i.e., ideation, development, and diffusion, and further presented a typology of innovation flow.

The existing RI definitions and typologies provide insights on how innovation can be termed as reverse innovations (which is mostly based on the flow of diffusion from emerging to developed markets). However, a comprehensive definition of RI as a multidimensional construct is lacking in the existing literature. The literature provides various factors associated with RI; however, such factors are discussed in isolation and remain fragmented. Adopting the systematic literature review procedure, we classify RI-related factors as triggers, enablers, and barriers. We define triggers as a set of factors that initiate or cause MNCs to think divergently and innovate. They include factors such as market saturation in developed markets (Govindarajan and Trimble 2012b ; Leavy 2011 ; Li et al. 2013 ), increasing cost constraints in both emerging and developed markets (Judge et al. 2015 ), resource cum infrastructure constraints (Furue and Washida 2014 ; Govindarajan and Trimble, 2012a , b ; Judge et al. 2015 ; Zeschky et al. 2014 ), and cultural differences (Govindarajan and Trimble, 2012a , b ). Similarly, we define enablers as the factors that have contributed to the design and development of RIs. The current literature discusses enablers such as the internationalization of research and development (Govindarajan and Euchner 2012 ; Govindarajan and Trimble 2012b ), empowering local growth teams (Corsi and Di Minin 2014 ; Govindarajan and Euchner, 2012 ; Immelt et al. 2009 ), and building local partnerships and collaborations (Govindarajan and Ramamurti, 2011 ). In addition to the above triggers and enablers, MNCs face challenges in rolling out RIs effectively. We term these challenges as barriers of RI and define these barriers as factors that obstruct in the innovation process and lowers the possibility of creating RIs. The barriers discussed in the RI literature include factors such as centralized organizational structure (Wan et al. 2015 ), fear of cannibalization (Furue and Washida 2014 ; Immelt et al. 2009 ) and quality perception based on country of origin among developed market customers (von Zedtwitz et al. 2015 ).

The literature further reveals that RIs are discussed mostly with anecdotal evidence and with only a handful of examples of successful cases of RI. However, there exists unsuccessful RIs too. For example, the Leveraged Freedom Chair developed by GRIT (Global Research Innovation and Technology, headquartered in Cambridge) did not receive the expected traction in developed markets, though it was successful in emerging markets (Hadengue et al. 2017 ). Similarly, Fiat 147 from Fiat Brazil, was not a success in Europe. Likewise, Renault’s Logan, the high-end TV set-top box designed by ST Microelectronics, and five finger shoes designed by Vibram could not do well in developed markets (von Zedtwitz et al. 2015 ). Therefore, the question arises as to how the process of developing RI can be induced in multinational firms. What are the factors that contribute to the development of successful RI in any firm? What kind of unique outcomes can be derived from the successful diffusion of a given RI? What underlying conditions should be met for the successful diffusion of RI in the targeted market? Overall, the phenomenon of RI lacks conceptual clarity and hence, there is a need to build a conceptualization of RI as a construct, identify its dimensionality to develop a comprehensive understanding (von Zedtwitz et al. 2015 ). Also, in the literature, there exists no discussion about the antecedents of RI, its consequences nor is there any exploration of how external and contextual environmental factors would moderate the success of RIs. Therefore, this study first defines RI as a multidimensional construct and then provides a conceptual framework for RI explaining its antecedents, consequences, and moderators. Further, Table 2 briefly explains the critical literature and positions this study accordingly.

Qualitative study

We undertook a qualitative study with the dual objectives of (1) conceptualizing and defining RI as a construct along with the underlying dimensions of RI and (2) identifying the antecedents, outcomes, and moderators of RI. Given the limited state of knowledge around RI as to how to achieve these broad research objectives, we found a grounded theory approach suitable. A grounded theory approach is an established and well-accepted methodology for theory building when either the theory is not proposed for a phenomenon or when the theoretical questions remain unanswered (Corbin and Strauss 1990 ) but there are instances of usage in the practitioner literature (Martin 2007 ). In this method, qualitative research is used for inductive theory building which is often combined with insights drawn from the literature (Glaser and Strauss 1967 ) using two approaches: (1) the Eisenhardt method, which is based on case study observations (single case or few cases) including in-depth interviews of the concerned stakeholders, and (2) the Gioia method, which is an iterative thematic coding process (Gioia et al. 2013 ). In the current study, we follow both approaches subsequently.

Since there is a growing number of RIs coming out of emerging markets such as India and China, it was appropriate to examine the process of RI in this context. For this study, the in-depth interviews were conducted with all the relevant stakeholders including the top management and relevant executives of an MNC, i.e., General Electric (GE), with its research facilities in India and China, end-users both in emerging and developed markets, prominent academicians, and experts working in the domain of innovation and RI (Table 3 captures a brief profile of the interviewees). GE, widely known for developing multiple successful RIs, makes an appropriate case for this study because it not only pioneered the concept of RI but has also successfully demonstrated rolling out over 25 RIs in the last decade from its India and China research centers.

Six rounds of interviews with the relevant stakeholders were conducted over four years from 2014 to 2018 (please refer Table 3 ). The interviewees were selected based on the following parameters: (1) The GE officials who were involved in the design and development of RIs at GE India, such as baby warmers, ECG machines, PET CT scanners, and anaesthesia administration units; (2) the experts in the field with substantial knowledge and more than a decade of experience dealing in the RI context; and (3) academics who have studied this phenomenon in-depth and have published relevant articles and journal papers in the area of innovation; and (4) end-users, who have used the products or are still using and adopting new RIs, implementing them in their day-to-day operations. These in-depth interviews helped us understand the micro and macro aspects of RI from an institutional lens. Each interview lasted for 60–90 min and was recorded and then transcribed verbatim, and the transcripts of these interviews were then analyzed to understand the organizational perspective and the strategic intent towards the RI.

The interviews provided us with insights on the following critical issues: (1) how the product team absorbed and deployed past learning in the next phase of innovation; (2) the process of identifying the unique need of the given customer segment by the product development team; (3) why organizations want to delve into RI, and what is the strategic intent of the firm in initiating the RI process; (4) the technological hiccups and opportunities firms observe during the process once they decides to go ahead with RI; (5) how to comprehend the process from the firm’s perspective and differentiate RI from other innovations such as frugal and cost innovation; (6) how managers understand the process of carrying out RIs from inception to the commercialization stage, including the internal and external challenges faced by them during the process; (7) the shared experience of the interviewees in rolling out subsequent RIs one after another, indicating common factors across different innovations; (8) the importance of RIs from the perspective of business strategy; and (9) the end-users’ experience, indicating their motivations for using the product and the feedback on product performance. Collectively, the interviews were informative and provided us with enough evidence to validate the conceptual framework explaining the RI process holistically. Follow-up data collection was conducted in subsequent years through telephonic interviews, virtual meetings, and face-to-face meetings with GE officials, and was completed in January 2018.

Further, we carefully studied over 25 RIs as individual case studies; Appendix Table 5 provides a brief description of all RIs, their outcomes, and benefits in detail. This exercise significantly helped us to extract the antecedents, relevant moderators and outcomes for the proposed framework and also in conceptualizing RI as a construct. Triangulation of data between the literature, interviews, and marketplace evidence was conducted to ensure construct validity (Patton 1987 ).

Conceptualizing reverse innovations

In order to conceptualize and define RI as a construct, we followed the Gioia method to undertake the thematic content analysis, according to which the insights gathered from the triangulation study were thoroughly analyzed. Thematic content analysis is a “systematic coding and categorizing approach used for exploring large amounts of textual information unobtrusively to determine trends and patterns of words used, their frequency, their relationships, the structures and discourses of communication” (Vaismoradi et al. 2013 ). This approach helped us extract the attributes and dimensions defining RI.

Initially, for thematic analysis, a panel of six members, two professors, two practising experts, and two research assistants was formed, who then extracted the themes and categorized the data in the relevant dimensions for RI. They also identified the first-order and second-order factors (antecedents and outcomes) in the conceptual framework. Later, for reliability analysis, a panel of nine members was formed, comprising of three PhD students, four research assistants, and two faculty members. They independently examined the coded categories and were asked to report their degree of agreement on a 5-point ordinal scale. Inter-coder reliability was established using Fleiss Kappa, as our approach involved multiple panel members. The initial Fleiss Kappa value of 0.41 represents moderate agreement. However, after using the negotiated agreement method (Garrison et al. 2006 ), it was raised to 0.72, which indicates a substantial agreement.

The analysis procedures and findings were shared with academicians with expertise in qualitative research methods, in innovation linked with BOP or both. They reviewed the methods, interpretations, and findings, and provided suggestions and feedback. Incorporating their input further strengthened the results. In the final phase of analysis, for the purpose of content analysis and face validity, the extracted attributes, themes, and dimensions were further shared with two assessors with market expertise from the field of RI. Their feedback and suggestions were incorporated to further strengthen the propositions and enhance the face validity. Finally, in this process, three dimensions were recognized for conceptualizing RI, i.e., “clean-slate,” “super value,” and “technologically advanced.” Table 4 exhibits the coding of all of the relevant factors with their order categorization. Next, we discuss the RI dimensions.

Clean slate

RIs are clean slate in nature because they are mostly designed and created using a ground-up approach with a focus on identifying new solutions for the existing problems (Govindarajan and Trimble 2012a , b ; Leavy 2011 ). The attribute “clean slate” finds its roots in the value innovation theory that demands firms look beyond the lens of their existing assets and capabilities and start afresh (Kim and Maubourge 1997 ). For instance, the RI “embrace baby warmer” was designed as a blanket using a wax-like substance that can retain heat for a longer duration compared to a conventional photo-therapy bassinet, which was based on lighting technology to keep infants warm. RIs that exhibit clean slate thinking beyond the existing production platforms available to MNCs and which are designed from scratch are likely to achieve greater success in terms of adoption and diffusion (Borini et al. 2012 ; Leavy 2011 ). Clean slate also provides an opportunity to create a solution for unserved or underserved markets adopting entirely new technology or a new application of existing technology (Ali 1994 ; Lee and Na 1994 ). Such innovations being clean slate emerge as ideal solutions to emerging markets and may later appear as RIs (Govindarajan and Ramamurti, 2011 ; Leavy 2012).

Super value

Affordability has been the central theme of innovations originating from and targeted to emerging market customers (Angeli and Jaiswal 2015 ; Gupta 2019 ; Hammond et al. 2007 ; Hossain et al. 2016; Prahalad 2004 ). In the context of RI, the term super-value refers to disproportionate value creation, i.e., offering superior product benefits at a significantly lower cost. It is argued that customers in emerging markets require affordable solutions that are good enough to meet their basic needs (Bower and Christensen 1995 ). However, the above argument proves invalid in light of value innovation theory (Kim and Mauborgne 2005 ), suggesting that value innovations aim at creating a super value product focusing on reducing the cost without compromising the outcome performance aligned with the industry benchmark; rather, the idea is to further enhance the performance in the best cost scenario. For example, GE India’s $500 ECG machine offers a scan at less than 10 cents without compromising on the clinical efficacy that a $10,000 ECG machine would achieve at a much higher operating cost, and has been accepted favorably worldwide. RIs studied in the current study have showcased the super value phenomenon in multiple ways that include reducing the operating cost for users, offering superior features with improved functionality, and replacing the consumables/single-use components with reusable components that are of superior quality.

Technologically advanced

Most of the RIs adopt cutting-edge technologies to come up with novel products encompassing high performance at a low cost (Zeschky et al. 2014 ). RIs, initially designed with developing/emerging markets in mind, intend to provide solutions/products that are easy to use and require simpler operations skills. Such solutions are usually born out of ingenuity and backed up with progressive technology (Radjou et al. 2012 ). In this study, we observed that RIs encompass the application of a technology or an amalgamation of technologies that are radical and discontinuous (Dosi 1982 ). In the process, RI attains novelty, creating modular designs that are scalable, affordable, and technologically advanced. For example, the Discovery IQ PET/CT scanner has a modular design and is 40% cheaper, with increased efficiency in scanning technology, lower radioactive material exposure to the patient, and a reduced operating cost. Hence, RIs, unlike other cost innovations, are superior in the manifestation of advanced technology to come up with an innovative solution serving the needs of both emerging and developed markets.

The three dimensions discussed above jointly define and characterize the RI. Though there exist a few other emerging market-focused innovations that have similar characteristics, the presence of all of these underlying dimensions in unison constitutes an RI. Nonetheless, each element discussed above will have to be present in different proportions and degree of intensity across various product categories. In the following section based on this conceptualization, we attempt to define RI and present a conceptual framework along with research propositions.

Conceptual framework

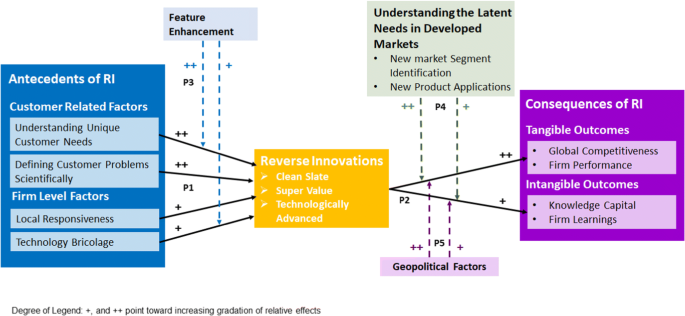

RIs have the potential to make an impact in both emerging markets and developed markets. Identifying and understanding the determinants and factors that are important in creating RIs would help MNCs in crafting and realizing the full potential of RIs in all relevant markets. It would also interest policymakers to design conducive policy frameworks that would encourage RIs to benefit the customers in both emerging and developed markets. Hence, we propose an overarching conceptual framework of RI by extracting insights from the triangulation study (Fig. 1 ). The proposed framework identifies the antecedents, moderators and consequences of RI. Additionally, we advance several research propositions based on the relationships between the identified constructs. Given the paucity of literature around RI, we draw arguments for our propositions from the qualitative study as explained in the previous section.

Conceptual framework: Factors influencing RI and its outcomes

In the proposed framework, we first discuss the antecedents of RI, wherein the observed innovation routines are categorized as customer-related factors and firm-specific factors. Customer-related factors include understanding unique customer needs and defining customer problems scientifically . The firm-specific factors consist of local responsiveness (i.e., the firm’s ability to respond to the local requirements/problems in emerging markets) and technology bricolage (i.e., making use of the available technology) in order to provide a solution to the problem. The outcomes of RI were categorized based on the value RIs would generate for the firm as tangible and intangible outcomes. Tangible outcomes are comprised of global competitiveness and firm performance , whereas intangible outcomes reflect on knowledge capital and firm learning .

The proposed framework further discusses the moderating factors (boundary conditions) affecting the various proposed relationship paths. The moderators are categorized as feature enhancement , understanding the latent needs in developed markets , and geopolitical factors . For example, having an understanding of the latent needs of customers in developed markets would help MNCs in achieving the enhanced tangible and intangible outcomes. Next, we explain the proposed framework and propositions.

Antecedents to reverse innovation

Customer-related factors.

MNCs in emerging markets are losing their market share to domestic firms serving the low-income market segment (Angeli and Jaiswal 2015 ). The liability of foreignness Footnote 1 explains this disadvantage and institutional dualism Footnote 2 explains the root cause of the lack of customer centricity in emerging markets. Therefore, it is critical for the MNCs to comprehend the customer-related factors before carrying out the process of value innovations in the emerging markets. In the context of RI, the value innovation theory, which is driven by the knowledge-based view, may guide firms’ comprehension of the customer-related factors. Based on the tenet of value innovation theory, an innovation value may be significantly improved if it can address issues critical to the customers, thereby creating new markets for the innovation (Kim and Mauborgne 1999 ). This study proposes that understanding unique customer needs and defining customer problems scientifically in emerging markets will facilitate RI among MNCs.

Understanding unique customer needs refers to generating insights about the stated as well as unstated needs of emerging market customers in the context of their unique cultural, contextual, and cognitive environments along with their resource constraints. The knowledge-based logic in value innovation theory suggests that in order to create value, firms must match their offerings to the customers’ unique needs (Kim and Mauborgne 1999 ). MNCs address emerging market customer needs based on their similarities to developed market customers, assuming that the emerging markets will evolve similarly to developed markets (Govindarajan and Ramamurti 2011 ; Levitt 1993 ). Unlike developed markets, the emerging market customer needs are a function of constrained resources, lack of product knowledge, cognitive limitations, and socio-cultural barriers (Varadarajan and Jayachandran 1999 ). Therefore, understanding dissimilarities and unique customer needs in emerging markets is likely to promote lateral thinking and help firms to develop clean slate innovations that may become RIs serving the peculiar developed market customer segment. For example, the initial design of the low-cost ECG device launched by GE in India demanded higher skills to operate, whereas the end-user in the target segment required a user-friendly and an easy-to-operate device. One senior leader at GE stated:

When our engineers visited tier II and III towns, they learned that, the healthcare infrastructure in the segment was poor and trained manpower was the major constraint. Doctors and medical staff in these markets felt intimidated with our state of the art devices and expected equipment that were easy to operate. [ Respondent 1 ]

Leveraging this information, GE designed a user-centric, clean slate ECG machine with a simple one-touch operation that generated an easy-to-read report.

Understanding the unique needs of customer requires the ability to measure the unique value derived from the innovation as perceived by the customer, i.e., value-in-context and co-creation of that value by building trust (Raymond 1999 ). Value-in-context refers to understanding the customers’ needs in the context of their operating environment, i.e., their “setting of usage” (Von Hippel and Katz 2002 ). For example, it was reported during in-depth interviews that most of the scaled down versions of the high-end products failed, as they could not survive in the operating conditions of these markets. Similarly, building trust among the users is a pre-condition for receiving deep access in their environment. Highlighting the need for creating trust, one GE executive recalled:

In an attempt to conduct market research, the research team found that people were not willing to cooperate and the investigators were perceived as auditors and inspectors. To overcome this challenge, we collaborated with MART (a rural marketing research organization) which has deep access in rural markets. This allows us to build trust with the customers and therefore, we could successfully conduct research in more than 250 villages. [ Respondent 2 ]

In light of the above evidence, we propose that MNCs’ sincere efforts to understand unique customer needs will positively stimulate the process of creating innovations with greater acceptance in emerging markets (Dawar and Chattopadhyay 2002 ) and such innovations further can become prospective candidates for RIs.

Defining customer problems scientifically enables MNCs to address complex problems by considering the possible constraints in the environment of emerging markets and providing a solution by innovating a unique product. The essence of value innovation theory lies in creating value for the customer by adopting an inside-out problem-solving approach that enables firms to define problems by letting go of the existing methods and allowing space for fresh solutions (Barney 1986 ; Zhou et al. 2005 ). Therefore, defining customer problems scientifically facilitates discontinuous innovations that are clean slate and building a conducive case for RIs.

In the field interviews, it was reported that the starting point for all RIs is re-defining the customers’ problems using a “scientific approach” which was independent of the existing production platforms and had at least three underlying dimensions, i.e., the generic cause of the problem, contextual cause of the problem, and the customer’s cognitive perception about the problem. For example, while designing a ‘baby warmer’ to be a successful RI, the innovation team first comprehended the generic cause of jaundice, which was identified as inflated bilirubin. Second, the contextual issues around jaundice, i.e., the patient and his/her environment, were considered, and third, the cognitive understanding among the stakeholders around the occurrence of jaundice at the time of birth was taken into account. Referring to the need for scientifically defining the problem, one respondent recalled:

Jaundice is one of the major causes of infant mortality and is caused by inflated bilirubin. This can be cured with an exposure to light having a wavelength of 420 nano-meters. Hence, we started looking at the solution around the scientific explanation of the problem and not around our existing line of products. [ Respondent 3 ]

This understanding of the scientific cause and solution helped the product development team to explore and develop a light-based solution that could generate light waves in the specified range. Across over 25 innovations, the scientific approach of looking at the problem provided significant insights to GE’s Indian R&D centre to develop cost-effective, high-value solutions. Such solutions are not only technologically advanced and reliable but also offer easy-to-use functionality (Bessant et al. 2005 ; Winter and Govindarajan 2015 ). Understanding the customer’s unique needs and scientifically defining customer problems also helps firms to build adaptability and technological advancement in the RI to accommodate the need of customization if demanded by the customers in developed markets at the latter stages of the innovation adoption curve.

Firm-level factors

Firms vary in their ability to innovate, which can be attributed to several factors based on the dynamic capability theory, organizational agility theory, and bricolage theory (Damanpour 1991 ; Eisenhardt and Martin 2000 ; Hurley and Hult 1998 ; Teece et al. 1997 ; Teece et al. 2016 ; Winter 2003 ). Dynamic capability refers to the firm’s ability to “integrate, build and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environment” (Teece et al. 1997 ). Similarly, the organizational agility refers to “capacity of an organization to efficiently and effectively redeploy/redirect its resources to value-creating and value protecting higher-yield activities as internal and external circumstances warrant” (Teece et al. 2016 ). Bricolage theory is primarily focused on the “construction or creation of work from a diverse range of things that are readily available, or a work created by mixed-media” (Senyard et al. 2014 ). The above-mentioned theories indicate that firms develop the capability to create high value by being responsive to the dynamic environment via efficiently deploying the available resources. Conforming to this discussion and based on grounded theory insights, this study proposes local responsiveness and technology bricolage as critical firm-level factors conducive to the process of creating RI in the MNCs.

Local responsiveness is the extent to which MNCs structure their emerging market subsidiary to respond to the local distinctions and specific needs arising from the emerging market’s external environment (Bartlett and Ghoshal 1989 ). The dynamic capability theory emphasizes “continuously adjusting, adapting and reconfiguring strategic directions in core business to match the requirements of the changing environment and create value” (O'Connor 2008 ). We identify that the firm’s local responsiveness can be reflected through component localization, promoting an “in-country-for-country” organizational structure, empowering local growth teams (LGTs), and building local partnerships.

Component localization refers to the ability of firms to use locally available resources efficiently. MNCs employ local resources mostly to gain a cost advantage; however, sometimes it is imposed by local legal and business regulations. In order to capitalize on the benefits of component localization, the firm needs innovative processes for efficiently selecting and integrating the locally procured components and resources (Martinez and Dacin 1999 ). Our interview insights suggest that component localization adds to the ability of MNCs to produce super value products by significantly reducing the operational cost. As one of the respondents recalled:

While sourcing components locally for MAC 400, we not only kept our product development costs significantly low but also generated deep knowledge about locally available resources equivalent to the USA quality standards at a lower cost. [ Respondent 7 ]

The organizational agility theory suggests that in order to capitalize on the available local market potential, the organization must develop a set of capabilities including realignment of the organizational structure (Dove 2001 ; Lu and Ramamurthy 2011 ) and its resources (Rugman and Hodgetts 2001 ; Subramaniam and Venkatraman 2001 ; Teece and Pisano 1994 ). The in-country-for-country attribute of local responsiveness refers to having an independent matrix organizational structure for emerging market operations, which is treated as an independent strategic business unit with its own profit and loss (P&L) account with its own separate growth strategy. One respondent during our interviews commented:

“In India for India” strategy allowed taking decisions about what projects to undertake, what resources to invest. This not only fast tracked the overall process of innovation but also permitted us to decide locally on providing adequate financial support for funding innovations. [ Respondent 5 ]

Emerging markets are often complex and characterized by a high level of heterogeneity (Angeli and Jaiswal 2016 ) and an in-country-for-country structure would grant a greater degree of autonomy to the firms, enabling them to respond locally (Luo et al. 2011 ). This also helps firms to create super-value, clean slate solutions targeted to the local marketplace. Further, to achieve local responsiveness, firms are required to empower LGTs. During our interviews, one respondent mentioned:

The innovation success was an outcome of shifting the power to the local growth teams in which the focus was to integrate technological R&D with a deeper understanding of local knowledge and issues. Localization helped us in technology transformation keeping the developmental cost and time significantly low. The new ECG device was developed within a short span of 22 months and with a development cost as low as $500,000. [ Respondent 1 ]

By empowering LGTs, there is a higher probability that the firm develops clean slate solutions with the help of LGT’s deep understanding of the context along with the firm’s accessibility to the technological prowess available at the global level (Ambos et al. 2010 ; Govindarajan and Ramamurti 2011 ). To be locally responsive, MNCs are required to build critical local partnerships to achieve technological diversity and lateral thinking necessary to innovate super-value, technologically advanced product that is clean slate in nature (Almeida and Kogut 1997 ).

Technology bricolage is defined as “making things do by applying combinations of the resources at hand to new problems and opportunities” (Baker and Nelson 2005 ). Though bricolage theory is discussed in the context of small firms, recently it is suggested that adopting bricolage holds equal significance for MNCs operating in emerging markets. It facilitates super-value innovations by creatively improvising upon the scarce resources and/or whatever else is at hand (Baker and Nelson 2005 ; Ernst et al. 2015 ; Garud and Karnøe 2003 ; Halme et al. 2012 ). Systematically extracting insights from the extant literature, we propose two strategic dimensions to bricolage: resource bricolage and component bricolage (Baker and Nelson 2005 ). In resource bricolage, the firm starts with mobilizing the resources it is closely familiar with and integrating them to overcome internal resource constraints (Baker et al. 2003 ; Ferneley and Bell 2006 ). During the interviews, a senior leadership official mentioned:

We start any new project now by looking at our global portfolio and charitably borrow resources from our other divisions and businesses. For example, when we started working on our phototherapy equipment, we approached our lighting business and requested them to develop a LED-based solution for the new product. [ Respondent 3 ]

Component bricolage is “creating a new application by using off-shelf components originally designed for other products” (Baker et al. 2003 ). It was reported during interviews that developing indigenous technology for all functionalities is not always a priority of product development teams. Rather, they first consider the available off-shelf technologies (i.e., existing technology) that could readily be used in the product development process. Since the broad architecture of the product is pre-defined and the interfaces of off-shelf are standardized, leveraging existing technologies brings in high synergies and cost advantages (Vanhaverbeke et al. 2002 ).

Leveraging technologies from multiple sources has received limited attention in the innovation literature (Howells et al. 2003 ; Tsai and Wang 2009 ). However, in the RI context, both resource and component bricolage is adopted extensively compared to any other mainstream innovations. In the mainstream innovation process, firms refrain from adopting open-source technologies subjected to the associated risk, whereas in RI, since the core technology remains with the organization, the cost and time advantage makes the risk relatively unimportant.

Innovations that are conceptualized and executed to satisfy unmet needs are more successful than innovations that are merely an extension of existing technologies and incremental in nature (Crawford 1987 ; Ortt and Schoormans 1993 ; Zirger and Maidique 1990 ). In this study, the firm-related factors, i.e., local responsiveness and technology bricolage facilitate the innovation process more than just the extension of existing technologies and adopting local practices, and therefore help convert the customer insights into an innovative product. Through marketplace evidence, it is evident that the success of RI largely depends upon the quality and accuracy of customer insights. MNCs often look at the customer insights from the lens of their world-wide learning and global efficiency, thereby failing to make successful inroads lacking the understanding of the unique needs of customers in emerging markets (London and Hart 2004 ). In the context of RI, it becomes even more important for MNCs to concentrate heavily on comprehending the unique needs of emerging market customers and further define them scientifically, independent of existing solutions (Judge et al. 2015 ; London and Hart 2004 ). Unless the needs are understood holistically, firms cannot initiate the process of RI to accomplish the requirements of both markets i.e. emerging and developed. Hence, we conclude that a better understanding of the customer-related factors will have a higher positive influence on the creation of RIs compared to the firm-related factors. Therefore,

The customer-related factors will have a higher impact on the development of RI compared to firm-related factors.

Outcomes of reverse innovation

The theories of the firm suggest that firms adopt business strategies such as globalization with the ultimate aim of attaining sustainable growth along with building innovation capabilities and organizational learning (Anderson 1982 ; Knight and Cavusgil 2004 ). However, the globalization strategy falls short in delivering the above goal and hence, RI has been proposed as a new firm strategy to deliver sustainable growth at a global level with positive outcomes both tangible and intangible (Govindarajan and Trimble 2012a , b ). We identify global competitiveness and firm performance as tangible outcomes and knowledge capital and firm learnings as intangible outcomes of RI.

Tangible outcomes

Global competitiveness at the firm level is defined as “the ability of the firm to design, produce, and/or market products superior to those by competitors” (D'Cruz 1992 ). Though the business firms in the environment of dynamic customer expectations acknowledge the importance of innovations across global markets, it is critical for the MNCs to focus on innovations that create superior value for the customers and help firms attain a long-term competitive advantage (Kim and Mauborgne 2005 ). The marketplace evidence considered in this study exhibits the ability of RIs to create a competitive advantage not only in emerging markets but also in developed markets. Carefully designed RIs open up new opportunities of growth as they facilitate MNCs to tap into new emerging markets and meet the requirements of resource-constrained customers, test the product concept, and later introduce them into developed markets (Zeschky et al. 2014 ). The developed market customers are looking for RIs since these markets have a growing segment of customers similar to the emerging market in terms of their affordability constraints. For example, Obamacare covers a significant section of the American population who cannot afford high-end treatment, and low-cost devices such as Discovery IQ can significantly bring down the cost of cancer treatment in the USA. Also, the micro-credit concept in the banking service industry has achieved a significant foothold in developed markets (Govindarajan and Trimble 2012b ). Therefore, RIs with their inherent super-value and technologically advanced attributes provide MNCs with a competitive edge in the global marketplace.

Firm performance is defined as achievement of the stated business goals measured in terms of profitability, market share, and shareholder value (Hult et al. 2004 ). The positive impact of innovation on firm performance has been documented unequivocally in the literature and is principally intended to deliver superior firm performance (Damanpour 1991 ; Hult et al. 2004 ). RIs are aimed at addressing unique customer needs, serving new markets segments, and positioning products differently with an objective to boost sales helping firms to attain greater market share. Besides market share, by embracing the principles of RI, firms also develop dynamic capabilities that boost firm performance by restructuring the firm’s resources, operational routines, and innovation competencies which deliver tangible benefits in terms of better economic performance (Helfat and Raubitschek 2000 ). Therefore, RIs positively influence firm performance by helping firms deal with the complexities and uncertainties of the business environment to accomplish business goals effectively.

Intangible outcomes

Intangible resources are becoming increasingly important with a global shift towards the knowledge economy, and firms are increasingly competing for knowledge and information (Subramaniam and Venkatraman 2001 ). The ability to seize and harness knowledge locally and the ability to transfer and deploy this knowledge are jointly becoming an important source of sustainable growth. RIs are capable of delivering intangible outcomes and can help MNCs gain a steep learning curve adding to the knowledge capital that may help firms to build superior product development capabilities using customer insights. This knowledge capital would help firms respond to the fast-changing business environment and foster synergies between various functions/departments/units within the firm. Additionally, creating RI over a period of time delivers enhanced firm learnings and helps firms to improve in their actions through a better understanding of new insights, need for new structures in organizations, creation of new systems and processes, and new actions points (Fiol and Lyles 1985 ). From interview insights, it is evident that RIs significantly affect the productivity of the firms by contributing to the process of developing new product development capabilities, attaining cross-functional integrations, and leveraging existing technologies in creating super-value products. It also enhances the firm’s capabilities to understand the latent and stated needs of the customers and the local environment. For instance, one of the interviewees mentioned:

There have been certain learning along the way while practising RIs, for an instance our initial ECG product was targeted at physician and small clinics, but we realized that we have not yet reached to the majority of the market. There are 700,000 doctors in India but there is no exhaustive list of these doctors with their details, no common magazine gets published which these doctors could read, no sales organization had the extensive data to call to these 700,000 doctors. So how do we apprise them about the innovative ECG machine they should consider in their day-to-day medical practices, how do we sell our innovation to them? How do we connect with them? How do we provide them product training to help them understand the innovation better? [ Respondent 1 ]

In the process of exploring the answers to all of these questions, the learnings become manifested in terms of building the knowledge capital for the firm and increases the overall firm learnings on multiple aspects such as a better marketplace understanding, go-to-market strategy, post-sales service strategy, building local distribution networks, and strengths of local suppliers. By creating over 25 RIs, GE has continuously demonstrated the manifestation of these learnings extending from one innovation to other innovations.

Although RIs have the potential to deliver both tangible and intangible firm-related outcomes, the fact is that while developing RIs the primary aim of the firms is to achieve the tangible outcome in the form of global competitiveness and increased firm performance. However, tangible outcomes are delivered by exhibiting operational excellence at all levels in a firm to bring about synergies both in upstream and downstream activities that lead to the realization of intangible benefits of RI such as building knowledge capital along with enhanced firm learnings. With enhanced global competitiveness, firms are likely to sell a higher number of innovation units and, as a result, gain a higher market share relative to other competitors. This ultimately provides firms with a positive learning curve with their experience with the new product. In the future, these intangible outcomes will pull in more tangible benefits. However, in the first place, the selling of the product in the targeted space is critical to facilitate these two-way interactions between the tangible and intangible outcome of RI.

The successful diffusion of RI would bring higher tangible outcomes as compared to intangible ones.

Moderating variables

Employing the triangulation approach and grounded theory, we identify and categorize moderators as follows: feature enhancement (moderator between antecedents and RI); and ‘geopolitical factors’ and ‘understanding latent needs’(moderators between RI and its outcomes).

Feature enhancement is defined as incorporating extra components and features in the primary model of the innovation that can offer additional benefits to the customers beyond the core offering of the product. RI initially offers a value innovation bundled with a set of core features and performance indices to the customers of emerging markets and then tries to make its way to developed markets in order to realize that value innovation as a RI. However, developed market customers demand for customization and use of sophisticated technology in the given value innovation (Corsi and Di Minin 2014 ; Hart 1995 ; Zeschky et al. 2014 ). Firms are required to identify and understand the need for feature enhancement prevailing in the developed market segments and incorporate the innovative design to bring about better functionality and enhance the perceived value of the given RIs. Enhancing the product features also strengthens the underlying dimensions of RI, i.e., super-value and technology advancement (Corsi and Di Minin 2014 ; Zeschky et al. 2014 ). Emphasizing on the need for feature enhancement one respondent recalled:

After launching RI- MAC 400, a super-value ECG device in India and China, we realized the potential in the product if launched in developed markets. However, given the developed market users are tech-savvy and use computers extensively we added features like USB and Ethernet port in MAC 400 to provide computer connectivity. The modified version was rebranded as MAC 800 in developed markets. With the added features, it achieved a high degree of acceptance and appreciation in these markets. [ Respondent 6 ]

Additionally, RIs make use of technology bricolage since it can enhance the value of innovations by using off-shelf technologies. Furthermore, a comprehensive understanding of the need for feature enhancement in developed markets can boost the process of RI by using technology bricolage effectively. It significantly enhances the value of innovation by keeping the design and product development time unchanged (Drucker 1985 ; Schumpeter and Backhaus 2003 ). For example, John Deere modified its tractor, initially designed for the Indian market, by adding more power, sophisticated features such as GPS, and an air-conditioned cabin targeted to the developed market users. With these enhanced features, the tractors proved successful in the USA. In the year 2010, almost 50% of tractors manufactured by John Deere India were sold in developed markets (Govindarajan and Euchner 2012 ).

Feature enhancement as discussed above is expected to influence the relationship between both understanding unique customer needs and RI as well as technology bricolage and RI. However, it is likely to have a higher impact on the former relationship for the following reasons. First, the primary aim of feature enhancement is to enable firms to serve to the unique needs of developed market customers such as technological compatibility and need for sophistication (Judge et al. 2015 ), therefore a thorough understanding of the unique needs of emerging market customer along with feature enhancement required by developed market customers would enhance the feasibility of RI. Second, indirectly, feature enhancement contributes to technology bricolage by engineering additional functional requirement employing existing technologies and components (Judge et al. 2015 ). Third, in the process of feature enhancement, super-value and technologically advanced dimensions of RI are strengthened (Corsi and Di Minin 2014 ; Judge et al. 2015 ) which may further enhance the diffusion and adoption of RI in the developed markets. Therefore, unless the firm precisely comprehends the additional features that are valued by developed market customers, technology bricolage would not be able to bring in the desired product up-gradation. Hence, we propose that.

Feature enhancement is expected to have a greater influence on the relationship between understanding unique customer needs and RI compared to technology bricolage and RI.

Understanding latent needs in developed markets refers to the unidentified and/or unaddressed needs existing among the diverse customer segments in the developed market context (Narver et al. 2004 ). Latent needs are manifested as new market segment identification and new product applications . The existence of latent needs provides an opportunity to the firms by placing their innovations in these heterogeneous customer segments by offering the multiple applications of the given RI. This allows firms to position the innovative products in the varied segments serving to the different needs and further facilitate the diffusion of RI in the developed markets, bringing about a higher value outcome. Innovations that target latent needs have the potential to change the structure of the marketplace by addressing the unstated needs or by satisfying the existing needs with a significantly different approach (Judge et al. 2015 ). Since the choice to introduce RIs by MNCs in their home or other developed markets is driven by the goal of attaining significant growth, the ability to identify latent needs in these markets is likely to boost the global competitiveness. One of the respondents recalled:

With a market share of 35% (approximately) in the USA ultrasound market, we were sceptical of cannibalizing our own high-end ECG machine market when we planned to launch the low-cost MAC 800 in the USA market. However, we realized that there is a huge opportunity in terms of addressing latent needs. For instance, MAC 800 opened up completely new market opportunities for us such as serving to primary care doctors, rural clinics, emergency rooms, ambulances, and accident sites. [ Respondent 4 ]

In another case, Ingersoll Rand (India) Ltd., innovated a battery-operated refrigeration unit for small-sized vehicles in emerging markets (especially for small size trucks and vans in India). Such vehicles have small engines and hence cannot support engine-powered refrigeration unit. Later Ingersoll Rand successfully reverse innovated this product to developed markets where the RI was adopted by restaurant owners and small catering firms. Since the refrigeration unit was easy to install and did not require engine power, these customers installed the unit in their delivery vehicles to keep the food fresh for small deliveries. Therefore, identifying the latent need for their innovation not only helped Ingersoll Rand to gain a competitive advantage but also improved their profitability. Similarly, identifying the newer applications of the given RI is likely to produce enhanced tangible and intangible outcomes. For example, the primary application of any baby warmer is in neonatal intensive care units (NICU) in hospitals to incubate premature babies. However, GE positioned one of its RIs, the ‘Lullaby Warmer,’ in US hospitals as an additional facility within the mothers’ private rooms. The size of the equipment and ease of use created this new application for the Lullaby Warmer, thereby unlocking the substantial demand for such baby warmers in the USA market and providing a significant competitive edge.

Though understanding the latent needs in developed markets will have an influence on both RI outcomes, it is expected to have higher influence over tangible outcomes compared to intangible outcomes for the following few reasons. First, a better understanding of the latent needs in the target market would enhance the diffusion of RIs by creating new markets, helping the firms to increase their profitability, extend the product life cycle of RIs, and reduce the negative consequences of RI, i.e., cannibalization of incumbent products of high-margin firms. Second, while serving the new set of customers (either by exploring a new segment or by developing a new application of the innovation) will offer better customer understanding contributing to the firm’s knowledge capital and learnings which ultimately equip a firm to receive better competitive advantage and firm performance at a global level. Therefore, we propose:

Understanding the latent needs in developed markets will have a higher impact on tangible outcomes of RI than on intangible outcomes.

The diffusion of innovations across nations is a complex phenomenon, which is closely regulated by various geopolitical factors (Fichman and Kemerer 1999 ; Harris et al. 2016 ). In the context of international business, geopolitical factors can be defined as the existence of formal and informal rules and regulations in global trade such as regional treaties, trade barriers and lobbying. Since RIs are seen in the context of international business where the firms attempt to introduce their emerging market-focused innovations to the developed markets, the geopolitical factors play a major role in the process (Foxon and Pearson 2008 ; Harris et al. 2016 ). With the potentially disruptive effect of RIs in the global marketplace, MNCs have raised various concerns regarding such geopolitical factors resulting from the change in political leadership and increased instances of protectionism and trade barriers (Rowthorn 2016 ). One respondent shared:

In one of the developed market, we carefully use the term reverse innovation, as the current political leadership is not in favor to the innovations coming from emerging markets even if it originates from our own subsidiary situated in emerging markets. [ Respondent 9 ]

Similarly, lobbying by local manufacturers in defence of their home markets is also reported to impact the diffusion of RIs in developed markets (Corsi and von Zedtwitz 2016 ). Therefore, firms with the ability to manage geopolitical factors are likely to enhance their competitiveness by successfully rolling out RIs in the global marketplace.

Since geopolitical factors are macro and often dynamic, dealing with these factors develops the upstream and downstream capabilities of the given firm, and in the process enhances the overall knowledge capital of the firm (Gupta and Govindarajan 1991 ). For example, GE circumvented the imposed trade barriers by manufacturing one of its products in their home country. Though the product ideation, designing, and prototyping occurred in the emerging market, the product was manufactured in the home market and later was imported to the targeted emerging markets. Therefore, firms that can effectively manage the geopolitical factors in the global business environment are expected to leverage their tangible (i.e., firm performance and global competitiveness) and intangible outcome (i.e., firm learning and knowledge capital).

Though geopolitical factors are expected to have its influence on both tangible and intangible outcomes, it is likely to have a greater influence over the tangible outcome of RI. We identify the following reasons for our proposed recommendation. First, geopolitical factors directly affect the ability of a firm to do business in international markets. For example, tariff war between the nations restrict multinational firms to do business in a particular geographic region limiting their profitability (Foxon and Pearson 2008 ) which is likely to affect firm’s overall performance in the global context. However, firms that can mitigate these barriers by exploring solutions such as benefitting from free trade zones can explore opportunities in markets beyond geographical boundaries and ensure better margins. Second, geopolitical factors directly affect the international business decisions such as selection of manufacturing plant location, setting up the R&D centers and recruitments of employee. These decisions are critical in any business as it directly affects the bottom-line of the business, therefore, influence the tangible outcomes of the firm (Rowthorn 2016 ). Hence, we propose:

Geopolitical factors will have a greater influence over the tangible outcomes of RI compared to the intangible outcomes.

Implications of the study

Following the grounded theory approach and triangulating the literature, interviews, and marketplace evidence, this study suggests that various customer-related and firm-related factors constitute antecedents that may foster RI in any given firm. In particular, understanding unique customer needs, defining customer problems scientifically, local responsiveness, and technology bricolage appear to support and enable RIs. Further, factors such as feature enhancement, understanding the latent needs in developed market and geopolitical factors provide important boundary conditions for implementing RIs successfully and leveraging the potential outcomes of RI. Additionally, this study for the first time provides a comprehensive conceptualization of RI and defines it as a multidimensional construct, contributing to the literature as well to the practice by comprehending RI compared to other available emerging market-based innovation typologies.

This study recommends that it is important for MNCs to revisit their globalization goal by embracing RI as a strategy to achieve sustainable growth. This study proposes that RIs can be adopted as a well-thought-of strategy for attaining sustainable growth and achieving a competitive advantage, especially in the emerging marketplace. Also, rolling out such innovations back to their home country can be seen as a great opportunity in achieving a global competitive advantage and serving the untapped market segment in the developed markets by creating value both in upstream and downstream activities. However, for two reasons it is critical for MNCs to pay attention and comprehend the emerging markets holistically in the RI context.

First, the emerging markets such as India and other BRIC and VISTA countries have emerged as significant markets in their own right, not only due to their sizeable customer bases but also because of the constant rise in the average family income, resulting in the vast demand for products and services. The scaled-down versions of products from the developed world often do not find customer acceptance in these markets. Therefore, it is significant that MNCs produce the offerings aligned with the requirements of the customers in such markets. The accrued benefits are apparent in terms of generating huge top-line volumes in BoP markets (Prahalad 2004 ) as well as the possibility of increasing the bottom-line margins by selling these innovations in developed markets. Mastering the art of RI, therefore, will add up to the capabilities of the organization to succeed both in the emerging and developed markets, which will play a crucial role in surviving global competition (Knight and Cavusgil 2004 ).

The second reason is the major shift in innovation trends globally. A continuous increase in the contribution of innovations from emerging markets to the global portfolio of innovations is reported in the recent literature (Borini et al. 2012 ; Hart and Christensen 2002 ; Wan et al. 2015 ; Zedtwitz et al. 2015). Therefore, MNCs seeking growth by adopting RI startegy need to revisit their parent–subsidiary relationships. This entails restructuring the organizational matrix and the strategic orientation of R&D function housed at their emerging market subsidiaries (Borini et al. 2012 ) in the light of antecedents and moderators proposed in our conceptual framework. Similarly, domestic firms from emerging markets are also opening up their markets and are becoming competitive globally, and the context in which these companies are globalizing is in stark contrast to the initial phases of globalization (Govindarajan and Trimble, 2012a , b ). The segment of marginalized customers in developed markets has grown substantially in the aftermath of the global recession and subprime crisis. This has resulted in a steep decline in the real income of the working population in developed countries, and it is expected that the downward trend in wages is likely to continue (Wan et al. 2015 ). With a constant decline in wage and employment levels, demand for super-value products in developed markets has shown a significant rise, making RI consequential. Therefore, it is important for MNCs operating in emerging markets not only to guard their existing market share and preempt disruption from the emerging market giants but also to grow their market size by addressing the latent needs of this segment in the developed markets with the help of innovations frugally designed in emerging markets.

A successful response to the above situation requires both a shift in the mindset and reorientation of approach towards innovations. Defining problems scientifically will not only enable the understanding of cognitive and contextual issues through indigenous problem solving but will also bring about a leap in the price–performance ratio and deliver higher-value propositions essential for unlocking mass markets in the emerging markets (Wan et al. 2015 ). Adopting a bricolage approach reduces both the time and cost of innovation. At the same time, the firm’s comprehending the unique customer needs and local responsiveness can deliver innovations congruent with the underlying expectations of the given market customers. This process ensures the scalability and brings in a high degree of customization which is beneficial in addressing the needs of both emerging and developed markets. For example, having a provision of adding sophisticated features in the given innovation (occurring in the emerging market) opens up enormous opportunities for reversal of innovation to the mainstream markets in the developed world. The marketplace evidence strongly suggests that the discussed antecedents and moderators such as feature enhancement are critical for implementing RI once the pre-conditions (Govindarajan and Trimble, 2012a , b ) of RIs are in place. It is equally important for the organizations to understand and adopt these antecedents because conventionally the innovation process predominantly focuses on technological or functional improvement with a focus on cost competitiveness.