The mindful leader: a review of leadership qualities derived from mindfulness meditation

Affiliations.

- 1 Business School, Nord University, Bodø, Norway.

- 2 Medical Yoga Sweden of California, Bodfish, CA, United States.

- PMID: 38505367

- PMCID: PMC10948432

- DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1322507

Mindfulness has been practiced by global leaders and companies as an efficient way to build effective leadership. Because of its popularity, plus the lack of a comprehensive theoretical framework that explains it in a leadership context, the research literature has called for a coherent account of the qualities that is derived by those leaders that practice mindfulness. Here, we aim to answer that call, by clarifying what leadership qualities can develop from practicing mindfulness . We report on a semi-systematic literature review of extant research, covering 19 research articles published between 2000 and 2021, plus other relevant supporting literature from the disciplines of leadership and neuropsychology. Our proposed framework consists of three main qualities of the mindful leader: attention, awareness, and authenticity. We call them the "three pillars of mindful leaders." We also propose that mindfulness meditation must be integrated into our proposed framework, as we are convinced that leaders who hope to benefit from these qualities must integrate a regular mindfulness meditation practice into their daily leadership life.

Keywords: leadership; meditation; mindful leader; mindfulness; neuropsychology.

Copyright © 2024 Doornich and Lynch.

Publication types

- Systematic Review

Grants and funding

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Traits of Effective Leaders: A Literature Review

ABSTRACT: Utilizing research to identify an effective leader is essential for creating a strategic business operational leadership model. The purpose of this literature review is to focus on select objective and less objective traits of leadership among individuals who are in those positions. We explore literature on objective leadership traits such as gender, age, education level, and job satisfaction level and on the less objective traits such as integrity, energy level, and business knowledge, among others. The goal is to evaluate the hypothesis that some, if not all, of these traits contribute significantly to effective leadership by analyzing the available literature about traits of an effective leader. We will explore the theories that have been proposed on this subject in the literature, identify to what degree researchers have investigated these theories, and try to confirm which of these traits continue to significantly be related to successful leadership. The purpose of th...

Related Papers

Joan Marques

Human Resource and Leadership Journal

John Githui

Purpose: It is argued that leadership qualities are very essential and important for the overall performance of organizations as those leaders who possess certain qualities influence the level of growth for organizations. This is notable in influencing decisions that concerns allocation of resources for the existing departments in organizations. The general assumption is that all leaders do possess the necessary and requisite qualities that would enhance the achievement of the desired goals and objectives of organizations. The foregoing is certainly not always the case as most individuals do have limited knowledge as regards the qualities that are important for individuals in the leadership positions. Methodology: The study provides the linkage between leadership qualities, followership styles or behaviors, and their impact to the overall performance of organizations. Findings: The study has established that various positive leadership qualities do positively affect individual and o...

Rashem Mothilal

papers.ssrn.com

Tim Lowder, PhD

Gomal University journal of research

liaquat hussain

Douglas Zubka

This paper presents an interpretation of the concept of great leadership. It also analyses traits, skills, and values of leadership based on both experience and research. These analyses also include insights about adaptive capacity, values and ethics.

Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal

Mohsin Shehzad

Zunair Ali Syed

In this dissertation, I examined the major leadership theories as psychological processes to determine whether such analyses can contribute to a prediction of effective leadership. I synthesized both trait theories and theories based on personal characteristics to explore leadership as a psychological process and showed that they can be used to predict effective leadership. An exploration of leadership as a psychological process demonstrated a significant role in determining how organizational psychology and different theoretical perspectives can be used to predict effective leadership. The study of major leadership theories and psychological concepts that can be used to predict leadership effectiveness has led researchers to realize several important findings. The core results obtained indicate that leadership effectiveness is dependent on an individual’s capacity to demonstrate specific behaviors, traits, and attributes (Bolden et al., 2003; Brouer et al., 2013; Cavazotte et al., 2012; Derue et al., 2011). Such behaviors serve an important role in determining the leadership styles used to improve performance, thereby emerging as predictors of leadership effectiveness (Datta, 2015; Mühlberger & Traut-Mattausch, 2015; Walumbwa et al., 2012). Some of these valuable and important traits that effective leaders must possess include: capacity to manage the interpersonal dynamics (Avolio et al., 2010; Boehm et al., 2015), ability to bring together diverse individuals tasks (Brouer et al., 2013; Caligiuri & Tarique, 2012), empower followers to perform tasks without manipulation or coercion (Burns, 2010; Michaelis et al., 2010), and consider their followers as an essential asset required for the execution of the developed plans (Oreg & Berson, 2015; Piccolo et al., 2012) among others. Furthermore, there are several skills that are linked to effective leader development. Such skills include self-awareness skills, such as emotional awareness abilities; self-regulation capabilities, such as self-control; and the capacity for self-motivation, including optimism (Brouer et al., 2013; Colbert et al., 2012).

Journal of applied …

Remus Ilies

RELATED PAPERS

Srini Kalyanaraman

Japanese Journal of Health Physics

yukinori narazaki

真实可查utk毕业证 田纳西大学毕业证本科学位文凭学历认证原版一模一样

Journal of Orthopaedics and Traumatology

Paritosh Gogna

Paolo Braca

Revista Amor Mundi

Liliane Inacia

Acta commercii

Micheline Naude

Ecosystem Services

Benedetto Rugani

Monnie McGee

João Pedro Fernandes

ENVIRONMENTAL SYSTEMS RESEARCH

Masahisa Nakamura

Yih-yuh Chen

Marine and Freshwater Research

Stefan Maier

Hormones and Behavior

Patrick Maroof

ISU毕业证书 伊利诺伊州立大学学位证

The Future of Talent Acquisition

Anderson Romanhuk

Jurnal Azimut

Hary Febrianto

Neuroscience

Clifton Callaway

Granthaalayah Publications and Printers

ShodhGyan-NU: Journal of Literature and Culture Studies

SK Publisher

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Cookies on GOV.UK

We use some essential cookies to make this website work.

We’d like to set additional cookies to understand how you use GOV.UK, remember your settings and improve government services.

We also use cookies set by other sites to help us deliver content from their services.

You have accepted additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

You have rejected additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

Register to vote Register by 18 June to vote in the General Election on 4 July.

- NLC Public Service Leadership Literature Reviews

- Cabinet Office

- Leadership College for Government

- National Leadership Centre

A Literature Review on Effective Leadership Qualities for the NLC by Dr Martin King and Professor Rob Wilson

Published 15 December 2020

© Crown copyright 2020

This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] .

Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned.

This publication is available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/nlc-public-service-leadership-literature-reviews/a-literature-review-on-effective-leadership-qualities-for-the-nlc-by-dr-martin-king-and-professor-rob-wilson

Executive summary

The review conducted did not produce evidence for a distinct ‘qualities approach’ drawing on the five identified qualities applied consistently across the literature. This is because the review presented a field of research into leadership that is characterised by fragmentation and conflicting nomenclature. These inconsistencies in the findings prevent us from drawing strong conclusions across the literature. Nevertheless, organising the various strands of debate into clusters that capture shared ways of talking about leadership across different theories in the literature can be helpful. The evidence that the five qualities as defined by the National Leadership Centre (NLC) are the most relevant ones is mixed. We summarise the evidence on this and suggestions on how to potentially adapt the descriptions on the five qualities in Section 2. In Section 3, we turn to a discussion about the challenges of a ‘qualities approach’ to the study of leadership. We describe three main clusters of theories in the literature (explained in more detail in the glossary in Appendix II) that challenge the notion that leadership derives exclusively from properties of the individual. These clusters can provide inspiration for an expansion of the NLC understanding of leadership. We then turn to the issue of the outcomes and goals that leadership is measured against in the literature in Section 4. Finally, in Section 5 we report the questions that emerged from this literature review and suggest ways in which the NLC could explore these, including co-productive and qualitative research methods.

Table of contents

- Our approach to this literature review

- The evidence of the five qualities in the literature

- Critiques of a ‘qualities approach’ to leadership

- Measuring leadership impact

- Conclusions and recommendations for future research Appendix I: Search terms and key results Appendix II: Glossary Appendix III: Bibliography

1. Our approach to this literature review

The NLC identified five qualities of leadership based on a preliminary review of the leadership literature: ‘adaptive’, ‘connected’, ‘purposeful’, ‘questioning’, and ‘ethical’. The purpose of the brief was to undertake a wider review of the literature exploring the evidence base on public leadership and examining the support for the NLC five key qualities approach. The brief sought to address the following key questions:

- To what extent does the evidence base support the NLC’s assertion that there are five qualities exhibited by effective public service leaders?

- How could the NLC’s articulation and definition of the key attributes of effective public service leaders be iterated or improved to better reflect the evidence base?

Based on the questions in the brief, we approached the ‘rapid’ literature review through a general search and then separate ones for each of the five qualities. This review involved six searches of abstracts repeated across five academic databases capturing discussions of leadership across academic fields and disciplines. The results of these searches were analysed through an abstract review. The searches included keywords such as synonyms to capture wider discussion of the qualities, and additional phrases to capture discussion of leadership in the context of public services and under conditions of complexity or uncertainty. The searches returned 9318 results. These results were then filtered further to 575 papers based on the preferences expressed by the NLC, including a broad scope review capturing wider research into leadership qualities; a preferred focus on studies based in the UK and similar regional contexts; discussion of public administration at a senior level in the context of collaboration across sectors and organisations; and a focus on complex or ‘wicked problems’ in the public sector. A full breakdown of the search terms, databases, and results can be found in Appendix I, while the findings of each of the searches can be found in the separate Abstract Search documents.

The search produced results across disciplines (e.g. public administration studies, leadership studies), across theories and methodological approaches (e.g. transformational leadership, distributed leadership), and at different levels of focus (from abstract discussions of the nature of leadership to discussions specific to particular professions). In our review of the abstracts we summarised key themes and findings emerging from the literature, including findings relevant to specific qualities, additional ways of talking about leadership present in the literature, ideals and outcomes, methodological approaches, and theoretical models of leadership. The results of each search presented in the Abstract Search documents include an overall summary, collected themes, referenced papers, and a full list of abstracts. The process revealed a number of trends in the literature, notably a diversity of theoretical perspectives on leadership and a wealth of studies exploring leadership in relation to specific outcomes and goals. The full implications presented by these developments were not apparent through review of the abstracts alone. Therefore, in addition to the abstract review, we conducted deep dives into key papers. We draw out the conclusions from these studies in this paper. In addition, we provide a glossary in Appendix II that defines prominent leadership theories and related concepts featured in the literature.

2. The evidence of the five qualities in the literature

The literature review did not produce evidence for a distinct ‘qualities approach’ drawing on the five identified qualities applied consistently across the literature. The review presented a field of research into leadership that is characterised by fragmentation and conflicting nomenclature. While there was evidence of studies using the same terms outlined in the NLCs discussion of qualities, they were not necessarily writing from a self-consciously ‘qualities approach to leadership’, and there was a lack of unified understanding underpinning the debate. Many studies would talk about the attributes of leadership in terms of style, traits, skills, and competencies. Furthermore, while studies might be interpreted as interested in the quality of connectedness, they might talk about it and understand it in different ways, for example, talking instead of empathy or emotional intelligence. Additionally, studies may import broader theoretical frameworks in describing leadership attributes. Influential frameworks include ‘transformational leadership’, ‘charismatic leadership’, ‘collaborative leadership’, ‘authentic leadership’, ‘servant leadership’, ‘network leadership’, ‘place-based leadership’, and ‘complex leadership theory’, all of which are described in detail in Appendix II. These approaches frame discussion of qualities, meaning that people may use different words for the same concept, or the same word for different concepts, making it hard to assess the evidence available on specific qualities.

It does not necessarily follow from these findings that the five NLC qualities are not a helpful way of understanding leadership. Indeed, the review demonstrates that there is a lack of clarity and coherence in the debate on leadership that might be helpfully navigated by organising the various strands of debate into clusters that capture shared ways of talking about what is valued in leadership that cut across different theories and frameworks in the literature. There is mixed evidence that the five qualities might provide such a useful framework. In the case of ethical and adaptive leadership, there is direct evidence for discussion of these qualities, although there is variation in how they are understood. In the case of connected and purposeful, there is more indirect evidence for discussion of these qualities, and perhaps a need to adapt the articulation of these qualities to better reflect the direction of the literature. Discussion of the quality of questioning is arguably the weakest, or at least a case where there is a lot of overlap with other qualities. We discuss the findings of each individual quality in the tables below.

NLC definition

Adaptive leaders are able to change proactively and constantly learn in a complex, uncertain and volatile world. Number of abstracts reviewed: 141

Summary of findings

Adaptive leadership and the need to learn in the face of complex challenges featured prominently in the literature. The review revealed a more formalised understanding of ‘adaptive leadership’ presented in Appendix II. It should be noted that the discussions of this quality often encouraged a less individualistic understanding of adaptation, in some cases talking of adaptive organisations, relationships and cultures, and organisational agility.

In order to build on this the NLCs definition, it may be helpful to further explore the more specific understandings of adaptive leadership, as well as the relationship between individual adaptiveness and organizational-level adaptiveness.

Trends in the literature

- Discussion of adaptive leaders was common, including a formalised understanding of ‘adaptive leadership’, adaptive behaviours, and an adaptive leadership framework. Further ways of talking about this quality in the context of leadership included ‘learning’, ‘leaders as learners’, and related concepts included ‘self monitoring’.

- In addition to talking about adaptiveness as a quality of individual leaders, the literature also included discussion of adaptive organisations, relationships, and organisational agility.

- There was also some overlap with other qualities discussed in the brief, suggesting for example that in order to be an adaptive leader one also has to exhibit other qualities, such as attributes related to ethical leadership (e.g. trustworthy, authentic, purposeful, forward looking, visionary).

Ethical leaders consistently behave in ways that create trust, and they take a long-term, sustainable approach to fulfilling the organisation’s public service mission. Number of abstracts reviewed: 123

Ethical leadership featured prominently in the literature revealed the complex and multifaceted nature of the relationship between ethics and leadership. It was frequently discussed in the context of more formalised concepts such as ‘servant leadership’ and ‘authentic leadership’. The literature illustrated how the ethical implications of leadership can vary greatly depending on the professional context in which it is applied, and how leadership presents ethical dilemmas and potential tensions between the professional and ethical norms of leadership and what might be commonly perceived to be good.

Given the multi-faceted nature of ethical leadership, there may be a case for crafting a more specific definition, with thought given to how abstract-level definitions of ethical leadership interact with context-specific understandings of ethics.

- Ethical leadership was by far the most discussed quality of leadership, often in relation to frameworks of ‘servant leadership’ and ‘spiritual leadership’. It should be noted that ethics represents a much broader set of concerns than we might reasonably expect from the other qualities.

- Abstract-level discussions of the good leader can be contrasted with more context-specific discussions of leadership, including ethical frameworks, norms, and dilemmas encountered by specific professions such as nursing.

- Within the literature, there is a lot of focus on ‘building trust’ as outlined in the NLC definition with a focus on supporting others. There was some discussion around ‘sustainable’, ‘long-term’, and ‘public service ethos’, which is similar to public service mission.

- Some concepts that were mentioned in the literature that are not in the NLC definition include ‘integrity’, ‘credible leadership’, ‘authentic leadership’, ‘values’, and ‘self-efficacy’.

- Ethical leadership is also contrasted with administrative evil, mistrust, and narcissism.

Connected leaders are empathic, collaborative thinkers who consistently work across organisational boundaries to build strategic relationships across the public service. Number of abstracts reviewed: 127

Connected was not frequently discussed in the literature, however the elements of this quality described in the NLC definition were heavily discussed in relation to leadership. It was more common to talk of this quality in terms of empathy, while emotional intelligence can be interpreted as a related concept that features prominently in the research.

The results of the review present two general questions. The first is whether the NLC definition of connectedness is too rich as it encompasses both notions of empathy and collaboration. The second question is whether the notion of ‘collaborative thinkers’ captures the way in which the literature is talking about collaborative approaches as it potentially challenges the qualities approach (discussed in more depth in Section 3 of this paper). This is an area that would be helpful to explore further.

- Although connected leaders might be a helpful, more holistic way of talking about this quality of leadership, it was more common for this quality to be discussed in other terms including those listed such as ‘empathetic leadership’, but also through concepts like ‘emotional intelligence’ (although this terms obviously relates to a much more specific and contested concept).

- The description of ‘collaborative leaders’ who build strategic relationships is potentially relevant to a significant portion of the literature that deals with collaborative approaches and relational understandings of leadership (see for example the description of ‘network leadership’ and ‘collaborative leadership’ in Appendix II).

Purposeful leaders display absolute clarity about their mission and purpose, and they are able to see beyond the problems and pressures of the present. Number of abstracts reviewed: 36

Compared to other searches, such as ‘adaptive’ and ‘ethical’, ‘purposeful’ leadership did not return many results. This could be due to the fact that ‘adaptive’ and particularly ‘ethical’ are terms with much wider applications that are likely to be used in research. It may also be that the notion of purposeful leadership is not widely recognised or applied in the literature, even if related concepts feature more frequently.

The NLC could consider linking the idea of purposefulness with the ideas discussed in the literature of ‘boldness’ and ‘motivation’ on top of those of ‘mission’ and ‘clarity’ that are already present in the definition.

- Purposeful leadership is often discussed in terms of boldness, clarity, clear communication, clear goals, and planning. Related terms include ‘being bold’, ‘having vision’, and ‘thinking outside the box’. Studies also consider the relationship between these qualities and narcissism as a personality trait and charismatic leadership as a leadership type.

- One might argue though, that the notion of ‘purposeful leadership’ is implicit in the way people frame talk of ‘transformational leadership’ and ‘public service motivation’ (see Appendix II for more details)

Questioning

Questioning leaders are open minded and seek to understand the views and experiences of others. Number of abstracts reviewed: 42

There was little evidence to support ‘questioning’ as a distinct quality of leadership within the literature. It may be helpful to consider the purpose of distinguishing this quality from the ideas of ‘adaptive’ and ‘connected’ and what might be lost by merging it to these other attributes.

- Compared to other searches, such as ‘adaptive’ and ‘ethical’, ‘questioning’ leadership did not return many results. Those that it produced, emphasised the importance of ‘curiosity’ and the use of questions (rather than the quality per se) as a means of building trust, respect, constructing authority, and developing and building relationships. ‘Vigilance’ also appeared as a related concept.

- The concept description shares similarities to the description of ‘connected’ and ‘adapted’. For example, a person who is open minded and seeks to understand the views and experiences of others might be described as ‘empathetic’ in some contexts or perhaps receptive to change and capable of learning and adapting in other contexts. In this sense it may be that the literature tends to discuss these features in ways more aligned with that language.

3. Critiques of a ‘qualities approach’ to leadership

Stepping beyond the discussion of the evidence of individual qualities, the literature reviewed presented a number of challenges to taking a ‘qualities approach’ to the study of leadership altogether. Recent trends in the literature tend to depart from an understanding of leadership as deriving exclusively from properties of the individual. Based on deeper exploration of the key papers in this area, we explain the evolution of leadership studies towards less individualistic theories and the implications of these developments for a ‘qualities approach’ in the section below.

3.1 The evolution of leadership studies

Over the past fifty years, the understanding of public administration and governance in the literature has become increasingly nuanced and complex (Bussu and Galanti 2018, Horwath and Morrison 2007, Heifetz et al 2009). Many recent studies observe a shift from hierarchical, command and control mechanisms to coproduction and/or collaborative action across sectors, organisations and disciplines (Silvia 2011, Avolio et al 2009). In parallel to this, the study of leadership also evolved and branched out in this direction. Heroic, great-man theories that focused on traits and qualities unique to the leader used to be predominant, while now the literature presents more expansive understandings of leadership and its challenges that attend to the relational, situational, and context-specific elements (Bass and Bass 2008).

The shift to this more nuanced understanding of leadership is also a response to criticism of exclusively leader-centred approaches. Accounts of ‘charismatic’, and later ‘transformational leadership’, which emphasise the capacity of leaders to inspire and motivate followers to excel in their work and enhance performance (see Appendix II for more details), have been criticised for being too individualistic in their understanding of leadership. Stogdill (1948 in Bass and Bass 2008) argues that the qualities, characteristics, and skills required of a leader are determined to a large extent by the demands of the situation. Therefore, analysis of leadership cannot be abstracted from the context in which it occurs.

3.2 Three challenges to the qualities approach

As a result of these criticisms, there have been efforts to move beyond an individualistic account of leadership, resulting in a rich diversity of theories and models. These can broadly be grouped into three clusters of literature.

The first cluster (Bussu and Galanti 2018, Horwath and Morrison 2007, Tong et al 2018) responds to the increasingly horizontal and collaborative nature of public administration by rejecting heroic leadership approaches and encouraging us to reframe the leader’s role in terms of those around them. The unit of analysis remains individuals but rather than talking of leaders inspiring followers, these discussions will talk of leaders empowering others, fostering communication, building trust, and enhancing accountability. ‘Authentic’ and ‘servant’ theories of leadership belong to this strand of the literature (see Appendix II for more details).

A second cluster of the literature (Cullen-Lester and Yammarino 2016, Uhl-Bien and Marion 2009, Fairhurst 2007) rejects the individual as a focus of leadership, departing from talk of properties of individuals to properties of relationships, organisations, networks, and systems. Therefore we might talk of adaptive organisations rather than adaptive leaders, or we might think of qualities emerging through an intersubjective process of collaboration or relationship building. For example, the ‘leader member exchange’ theory (Dionne et al 2010) focuses on the relationship between leaders and followers where the quality of the relationship, not the qualities of leaders, determines effectiveness. Other examples of this strand are ‘distributed’ models of leadership (see Appendix II for more details), which consider the potential for leadership to emerge amongst different members of an organisation or network, regardless of their managerial role or seniority. The more extreme examples of this body of literature seek to transcend person-centred approach by focusing on sources of leadership outside of individual people (Ospina 2017). These approaches see leadership as an emergent process and practice intended to cultivate group members’ capacity to navigate to complexity, where leadership can emerge through relationships, system properties, networks as well as individual action. Theories that follow this approach include ‘network leadership theory’, ‘complexity leadership theory’, and ‘collective leadership’ (Ospina 2017, Bryson, Crosby and Stone 2015, Mandell and Keast 2009, Morse 2010) (see Appendix II for more details). These theories offer valuable insights and highlight the limitations of individualistic approaches, however they raise challenges of their own. Some of these more radical approaches are criticised in the literature for stretching the concept of leadership beyond any natural sense of the word, undermining the explanatory value of the term, and inviting one to consider whether such theories are meaningfully talking about leadership at all (Morrison 2010).

Finally, the third cluster of the literature departs entirely from grand theory of leadership altogether, focusing instead on specific types of challenges and barriers leaders face, as well as more specific goals and outcomes (Heifetz et al 2009, Ekstrom and Idvall 2015, Corazzini et al 2014). A prominent approach that belongs to this strand is ‘adaptive leadership theory’ (see Appendix II for more details). This is described not as a theory of leadership per se, but as a practice that mobilises people to tackle tough challenges and thrive (Heifetz et al 2009). The theory is oriented around specific types of challenges that have no ready answers and cannot be addressed with existing procedures and expertise. The activities recommended in the adaptive leadership theory literature may not be necessary or even desirable in other contexts. This approach draws our attention to the possibility that general theories of leadership may be too abstract to be helpful in understanding what is required in response to challenges that leaders face. A general leadership theory narrows our focus to a particular set of challenges anticipated by the theory, and this may neglect other barriers that might be experienced in practice.

An example of where this literature identifies challenges that might not be captured by general leadership theories is highlighted by Ekstrom and Idvall (2015). They discuss leadership challenges experienced by nursing staff, and the implications this has for retention of staff. A challenge the study highlights is the issue of nurses disassociating from their leadership role, concerned that they may appear lazy or bossy, and feeling uncomfortable in their role and therefore job. The discussion presents a specific challenge (the experience of disassociation) and its consequences for a specific outcome (staff retention). While this could be reinterpreted using the language of ‘transformational leadership’ or ‘leader member exchange’, it is not clear this would give us a better understanding of the problem or its potential solutions, rather it might obscure and over-complicate the issue. Intuitively this level of analysis is more helpful to understanding leadership in the context of nursing than the broader understanding introduced by general leadership theories. Further literature highlights the particular ethical dilemmas and frameworks for understanding ethics of leadership within particular professions, as these might present context-specific features (Storch et al 2013, Broussine and Miller 2005, Curtis and Hodge 1995). These discussions suggest a need to pay further attention to what is usefully gained, and also what is lost, by moving from the specific context to much more general understandings of leadership and leadership qualities.

3.3 Implications for the NLC’s qualities approach

To conclude, there is certainly a push from the literature to look beyond individual qualities of leaders and acknowledge the importance of the context and systems within which they operate. This doesn’t reject the validity of a ‘qualities approach’ but it calls for an expansive understanding of the qualities, which acknowledges that these may manifest in various ways and emerge from different sources other than the traditional leader. In this sense, in addition to thinking of adaptive qualities of individuals, the NLC could also consider how cultures or organisations demonstrate these qualities. Additionally, the literature would also suggest that attention needs to be paid to the situation in which leaders operate, including the specific challenges and barriers experienced by members of a system, and the specific goals or outcomes that would be desirable in a given professional context.

4. Measuring leadership impact

The discussion in the previous section considered sources of variety in how leadership is conceptualised and different approaches to understanding the challenges that leaders encounter. It is important to also reflect on variety in how good leadership is measured, and more specifically, the intended purpose of leadership — the goals and outcomes that leadership is judged against. The literature talks about leadership in the context of various outcomes, from the abstract to the context-specific, from outcomes relating to work output to satisfaction amongst employees or the wider public. The findings suggest a need to consider the compatibility and potential tensions between different goals and outcomes and therefore the need to understand the priorities of leadership in a given context, and the nature of the relationship between leadership style and particular outcomes.

4.1 Approaches to leadership outcomes

The impact of leadership is approached from a wide variety of theoretical perspectives and in many cases different theories are accompanied by specific methods of empirical measurement. For example, ‘authentic leadership’ has been approached through a leader authenticity scale and authentic leadership questionnaires (Avolio et al 2009). Nevertheless, it is helpful to note the presence of goals or outcomes that are applied across these different theoretical approaches as a measure of the impact of good leadership. We have captured numerous examples of these at the top of the Abstract Search documents, however the main ones identified in the literature reviewed are summarised in the table below.

This overview shows that the literature has explored leadership in relation to various outcomes. The measures of outcomes can vary; for example, Kotze and Venter (2011) measure an individual’s effectiveness by asking the individual and four colleagues to rate them, while Uster et al (2018) link effectiveness to external measures of performance. Some of the measures are easily verifiable (such as staff retention rates) to other outcomes such as trust or creativity that are more intangible and thus rely on more contested measures and indicators. Outcomes such as trust can be treated as a dependent variable by some studies (Agote et al 2016) and an independent variable by others (Lee et al 2010).

Finally outcomes are measured within different theoretical perspectives. For example, retention of staff has been explored from different theoretical frameworks, notably ‘leader member exchange’ and ‘transformational leadership’ (See Appendix II for more details). Joo (2010) and Joo (2012) both find a correlation between high-quality relationships between leaders and followers and staff retention in studies that utilise leader member exchange theory. Additionally, Wang et al (2018) explore the impact of transformational leadership and emotional intelligence on the retention of nursing staff, finding that transformational leadership and emotional intelligence were significant predictors of nurse intent to stay, with emotional intelligence found to partially mediate the relationship between transformational leadership and intent to stay.

In order to judge the significance of these findings, we would need to be able to establish the validity of the individual studies and the comparability of measures applied across studies to allow for meaningful comparisons, which is beyond the scope of this paper. An important consideration for the purpose of strengthening our understanding of leadership qualities is the extent to which the findings support a causal relationship between a given attribute of leadership and a given outcome, or whether they only establish correlation.

4.2 Implications for the NLC’s qualities approach

These examples from the literature illustrate multiple layers of variety in the research, from how leadership is understood and measured, to the variety of outcomes that are understood to be the desired goals of good leadership. It is beyond the scope of this paper to analyse the strength and validity of individual methodological approaches, the extent to which these studies establish a causal link between a given quality of leadership and a given outcome, or the most effective route to developing these qualities in leaders. Nevertheless, these questions are of importance to our understanding of a ‘qualities approach’ to leadership. For example, is the key to understanding how connected leaders are able to retain staff or enhance creativity emotional intelligence? If so, discussion on leadership development that focus specifically on enhancing emotional intelligence would be an important direction for further exploration. The developments in the literature suggest a need to think about the desired outcomes for leadership and the extent to which these are shared by different leaders, for example, whether particular outcomes are more relevant for particular fields, or specific challenges. Once there is a clearer sense of the desired outcomes and goals of leadership, it is possible to explore leadership attributes relevant to those outcomes and the strength of that research and potential for leader development.

5. Conclusions and recommendations for future research

The review undertaken here provides a wide ranging overview of leadership (with elements similar to a scoping review approach to the literature) through the lens of the NLC five qualities using the academic literature as its basis. Its strength is the breadth of the review and the broad grounding of the five qualities in relation to academic knowledge. The obvious weakness is the depth to which this review has been able to go into the details of the theoretical linkage of the literature with each quality. Another weakness is the limit of the academic literature generally — the context and contemporaneity — which are comparative strengths of the ‘grey’ literature. Literature reviews by their nature are prone to degrees of imprecision, particularly in an area as ambiguous as leadership and a context as complex as the public sector. Different approaches to reviews will always be prone to exaggerating aspects of a phenomenon and occluding others. Given these inevitable constraints, the key question is what to do with the knowledge base that this literature review provides.

Based on the findings and conversations with the NLC team, the following questions emerged as potential areas for future exploration that can advance both the NLC understanding of leadership and its goals as an organisation:

- What is the most useful balance of considerations between the individual qualities of leaders and the wider relational and contextual elements of leadership in public service contexts?

- How can the NLC make use of the plethora of theories of leadership that exist within the literature and judge the ways in which these may be helpfully applied in practice?

- How should the NLC understand the desired outcomes of leadership, how these might change depending on the context and how to navigate tensions between them?

- To what extent do findings and recommendations on leadership support leaders in interpreting challenges and providing effective leadership in practice?

- How can leadership qualities be usefully identified, learned, and practised through training?

- How can the NLC evolve their understanding of leadership overtime to ensure it accounts for the challenges and experiences of today’s leaders and supports their practice?

These are difficult questions and the first step in addressing them is identifying where the relevant knowledge can be found. The review provides a helpful resource to direct further exploration of the existing evidence base relevant to the issues raised by these questions. Further in-depth academic research could yield useful results, potentially in conjunction with ‘grey’ literature. However, the people best placed to provide the answers to these questions are the leaders themselves. Academic research helps to frame the debate but understanding the value of these theoretical insights, where and how they can be improved, requires closer collaboration and co-production with leaders and those who will translate these lessons into practice.

The NLC is uniquely positioned to tap into the knowledge of its network of public service leaders and gain primary insights into the challenges and attributes of leadership. It has the opportunity to genuinely co-produce with leaders the generation of insights into the way they operate in public service contexts and bring about better outcomes. This could be achieved through introducing co-production into the delivery of its programme or through using qualitative/participatory research methods. Using these methods would build the findings of this and other reviews and connect what is a rich but fragmented literature with the practice of leadership in a complex and ambiguous reality.

Appendix I: Search terms and key results

Appendix ii: glossary.

The literature review revealed how the study of leadership has been approached from a wide variety of theoretical perspectives appealing to specialised concepts and understandings of leadership and governance. The glossary below provides an introductory summary of the most prominent theoretical perspectives and concepts that were identified in the review. In each case, the definition is accompanied by a table providing references to papers discussing the theory, where the columns indicate where the theory has been applied in general leadership literature and in discussion of the five NLC qualities. The specific papers referenced in the columns can be found in the six Abstract search documents.

As for notation, papers are referenced by a number (e.g. [17]), where this refers to where the abstract appears in the search documents. An ‘! indicates a particularly important or relevant paper (e.g. [17!]), an ‘n’ indicates where no abstract was present (e.g. [17n]), a ‘-’ indicates limited information available (e.g. [17-]).

Charismatic leadership

Until the 1940s study of leadership primarily focused on individual traits. ‘Great-man’ theories and the ‘warrior model of leadership’ (see Machiavelli, Suntzu) understood leadership, as well as much historical and social progress, as attributable to the qualities of extraordinary individuals. Max Weber introduced the religious concept of ‘charisma’ into social sciences to describe leaders with extraordinary abilities and this notion of charismatic leadership has proven an influential modern continuation of the individual traits approach to leadership. Charismatic leaders are expressive, articulate and emotionally appealing. They are self-confident, determined, active and energetic. They have a positive effect on their followers who identify with them and have complete faith in them. House (1997) presented a theory of charismatic leadership resulting in renewed interest and empirical study of the concept.

Although theories that focus purely on traits have fallen out of favour and have been modified and adapted in recent literature. Charismatic leadership can be understood as a significant modern example of this approach to leadership. It has been influential on further developments such as ‘transformational’ and ‘authentic leadership’ (see p.23 and p.25 respectively), and remains part of the language of the study of leadership.

Transformational leadership

Transformational leadership is a theory of leadership that highlights a leader’s capacity to inspire their followers and thus enhance motivation, morale and performance. This is commonly understood to involve acting as a role model for followers, encouraging followers to act beyond their own self-interest and work for the good of the group, organisation or cause, take greater ownership for their work, to excel and self-actualise. It is commonly contrasted with ‘transactional leadership (see p.24) in which leaders rely on extrinsic rewards and punishments to produce more short term change in behaviour.

Transformational leadership was first mentioned by Downton (1973 in Bass and Bass 2008) and formalised in Burns (1978 in Bass and Bass 2008). Most articulations of transformational leadership treat charismatic leadership as an important dimension of transformational leadership, while including other elements such as inspirational leadership, intellectual stimulation and individualised consideration. Transformational leadership has also been understood to co-exist and indeed augment the results of transactional leadership. Scholars have noted limitations to transformational leadership, principally that the focus on leaders and followers is individualistic and represents only one way to understand and perform leadership (Ospina 2017). Furthermore the framework may be limited in its application to more collaborative and horizontal forms of leadership. Further theoretical developments in the study of leadership have moved away from the individual highlighting the importance of relationships and networks (for example see ‘network leadership’ and ‘collaborative leadership’).

Transactional leadership

Transactional leadership understands leadership in terms of an exchange or transaction between leader and follower, for example the exchange of reward for work. Transactional is often contrasted with transformational (see p.23). The main criticism of transactional approaches is that the rewards provide only basic motivation, may increase work rather than quality and may produce poorer results relative to transformational leadership.

Servant leadership

Servant leadership was formulated by Greenleaf (1977) who argues that leaders are required to curb their egos, convert their followers into leaders, and become the first among equals. The needs of others are the leaders’ highest priority, they are expected to build relationships that help their followers grow, while power has to be shared by empowering followers. According to Bass and Bass (2008) servant leadership shares much in common with transformational leadership such as vision, influence, credibility and trust. It is also linked with other models of leadership including self-sacrificial leaders.

Authentic leadership

Authentic leadership is a nascent but popular concept in the leadership literature that emphasises self-awareness, openness, fair-mindedness and the ethical foundations of leadership. The concept is related to ‘charismatic’ and ‘transformational leadership (see p.22 and p.23 respectively); the suggestion that there are pseudo (i.e inspirational but self serving) versus authentic transformational leaders led to research into authentic leadership (Avolio et al 2009:423). The moral or ethical component of authentic leadership has been questioned. Some have speculated on whether people can remain true or authentic to a value system or organisation that is itself damaging, harmful or corrupt. Similarly one might be able to inspire or build trust in people through superficial means without being trustworthy or honest in your interaction with them. These considerations highlight a distinction and potential tension between the norms or ideals of good leadership and broader considerations of the good. The philosophical foundations and methods of empirical study have also been challenged in the literature.

Adaptive leadership

Heifetz et al (2009) argue that adaptive leadership is a practice not a position. They define it as the practice of mobilising people to tackle tough challenges and thrive. It is an example of a ‘distributed leadership’ model (see p. 31), meaning leadership can be displayed by people across an organisation regardless of managerial role or seniority of position. Adaptive challenges have no ready answers and cannot be met by existing procedures or expertise. Adaptive change is uncomfortable, challenging our assumptions, beliefs and habits. Adaptive leadership requires non-traditional leadership behaviour, whereby leaders do not provide answers and accept a degree of conflict and discomfort to sustain adaptive change.

Three activities said to be core to adaptive leadership are

- Observing events and patterns without forming judgements about the data’s meaning.

- Tentatively interpreting observations by developing multiple hypotheses about what is going on.

- Designing interventions based on observations and interpretations in the service of making progress on the adaptive challenge.

Adaptive leadership has been criticised for failing to conform to traditional views of the leader, stretching the concept of leader to the point where it might be better described as a theory of facilitation. McCrimmon (n.d) develops an argument against the concept that suggests not all leadership occurs in the context of a problem, and not all change entails a response to an adaptive challenge. It is not clear that adaptive leadership makes such assumptions, though it may be better understood as a recommended response to a specific type of challenge rather than a general theory of leadership.

Complexity Leadership Theory

According to Uhl-Bien et al (2007), complexity leadership theory is a leadership paradigm that focuses on enabling learning, creative and adaptive capacity of complex adaptive systems within the context of knowledge-producing organisations. The conceptual framework includes three entangled leadership roles (adaptive leadership, administrative leadership, and enabling leadership) that reflect a dynamic relationship between the bureaucratic, administrative functions of the organisation and the emergent, informal dynamics of complex adaptive systems.

Morrison (2010) provides a critique of complexity theory. While acknowledging its rise in popularity and the valuable insights it offers, Morrison presents a range of concerns with the approach. These include the claim that it can be regarded as disguised ideology conflating description and prescription and that it risks exonerating leaders from expectations of accountability and responsibility.

Related theories: Complex Adaptive Systems: General [75]

Collaborative leadership

Collaborative leadership entails working across boundaries and in multisector and multi actor relationships (O’Leary et al 2010). In discussion of collaborative governance, Getha-Taylor and Morse (2013), observe that the traditional model of leadership development focused on leading within bounded hierarchy and via command and control mechanisms. This approach, they argue, fails to accurately reflect the nature and challenges of leadership encountered in contemporary joint public service delivery, which involves multiple government and for profit and nonprofit agencies. Such an approach must therefore be moderated with a focus on collaborative problem solving, working in flattened structures and incentivising behaviour in new ways. Collaborative governance, collaborative leadership and collaborative management are prominently discussed in leadership literature to highlight these considerations.

Related theories: Collaborative management: General [1][17] Collaborative governance: General:[24][27][29][51] [67][71][87] [107] Adaptive: [34]

Network leadership

According to Ospina (2017), network leadership theory views leader or follower attributions as properties of the system, in which influence relationships define relational structures, whether they be within a single organisation or across inter-organisational and cross sector networks. Silvia (2011) describes understandings of governance moving from hierarchical or command and control mechanisms to public services jointly produced by networks including government and private and third sector organisations. Network leadership can be understood as the study of leadership and management within these collaborations. For example, Silvia and McGuire (2010 in Silvia 2011) find differences in leadership between these two contexts, with an increased emphasis on people oriented behaviours such as motivating personnel, creating trust, maintaining a close-knit group and treating others as equals. The concept is also discussed in terms of collaborative leadership (see p.27). While the discussion of collaborative leadership is often framed as a response to a change in the nature of public administration, requiring consideration of factors including networks, discussion of network leadership appears to centre discussion on those networks and understand further features of the system through this lens.

Leader Member Exchange

Leader member exchange (LMX) refers to the exchange relationship between a leader and member (follower). LMX theory claims that the quality of the relationship between leader and member determines the effectiveness of leadership. High quality LMX relationships yield high levels of mutual trust, support and obligation, while low quality relationships are more instrumental and less effective (Ospina 2017). Associated with Graen (1976 in Bass and Bass 2008), LMX theory assumes that the leader behaves differently toward each follower and that these differences must be analysed separately. This theory is contrasted with most earlier theories that assume leaders behave in much the same way to all group members. Graen (1976) categorises followers as belonging to an in-group and an out-group with different behaviour expected of leaders in relation to these groups. Although it is less leader-centred it remains person-centred, and therefore has received some criticism from those seeking to broaden the object of study to factors external to the individual (such as ‘collective leadership’ on p.31 for example).

Related theories: See also Relational leadership [13]

Distributive leadership

Distributive models of leadership decouple leadership roles from formal positions of authority and propose that leadership may emerge in different locations, drawing on the collective intelligence of an organisational system in which interdependence and connectedness are critical. According to Ospina (2017), shared/distributed theories focus more directly on the relational nature of leadership and its collective dimensions by attending to new demands associated with horizontal relationships of accountability in contemporary organisations. The terms ‘distributive’, ‘distributed’ and occasionally ‘distributary’ leadership appear to be used interchangeably in the literature to capture the same issue.

Collective leadership

Collective leadership theories locate the source of leadership one level up from the individual or the relationship at the system of relationships — the collective (Ospina 2017). The primary source of leadership is not exclusively the leader (see transformational), the dyadic relationship (see leader member exchange), or the shifting roles (see shared/distributed), leadership can also emerge from other system properties such as the networks of interdependent relationships influencing what its members can and ought to do or other processes associated with the new demands of organising to achieve joint results (Ospina 2017:281).

Discussion of collaborative leadership focuses on shifts in the nature of public administration and the changing requirements of leaders, there is more flexibility in how leadership is discussed relative to these changes. In contrast, discussion of collective leadership reflects a more deliberate effort to reimagine the nature of leadership. Relative to some of the more traditional approaches to leadership, collective leadership can be understood as seeking to incorporate these approaches yet also broaden the scope of the object of study. It shares similar theoretical strands with network leadership and complexity leadership theory (p. 28 and p.27 respectively). Ospina et al (2017) argues that collective leadership lenses are particularly helpful in the study of leadership in networked governing arrangements.

The risks presented by expansive projects such as collective leadership is that they are vulnerable to concept stretching, distorting talk of leadership to the point that it loses explanatory value. When the focus moves beyond individual catalysts and persons, it is reasonable to question whether we are meaningfully talking about leadership at all.

Public Service Motivation

Public Service Motivation (PSM) is not a theory of leadership in itself but it is a widely referenced concept in discussions of public leadership. It is defined as an attribute of government and NGO employment that explains why individuals have a desire to serve the public and link their personal actions with the overall public interest. This concept features prominently in literature on leadership, notably in relation to transformational leadership (p.23) and discussions of roles, identity and motivation relating to both leaders and followers.

Leadership of place

Leadership of place is described as an inclusive model of leadership based on systems thinking in a spatial context. It is discussed within the context of New Civic Leadership (NCL), an approach which is understood as an alternative to New Public Management, and a response to the challenges of the complex multi-level, multi-disciplinary environment of a knowledge based economy (Gibney et al 2009). NCL, and by extension leadership of place, draws attention to the power of place in policy making. It is argued that the strong feelings of commitment people have to their locality have been neglected by other approaches to public management theory and practice. NCL highlights the role of place based leadership in spurring the co-creation of enhancing life in a locality. It has been associated with a number of aims, including drawing on the commitment of leaders to their locality in delivering long term benefits for the local community, using and building on local knowledge and building relationships and capacity within a community and local context. It has been observed that the concept of leadership of place is in its infancy and is used by different organisations to mean subtly different things.

Appendix III: Bibliography

Avolio, B., Walumbwa, F & Weber, T (2009). ‘Leadership: Current Theories, Research and Future Directions’ in Annual Review of Psychology, Volume 60

Bass, B. M. & Bass, R., 2008. The Bass Handbook of Leadership; Theory, Research, and Managerial Applications. New York: Free Press

Broussine, M., & Miller, C. (2005). Leadership, ethical dilemmas and ‘good’ authority in public service partnership working. Business Ethics: A European Review, 14(4), 379–391. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8608.2005.00419.x

Bryson, John M., Barbara C. Crosby, and Melissa Middleton Stone (2015). Designing and Implementing Cross-Sector Collaborations: Needed and Challenging. Public Administration Review 75(5): 647–63

Bussu, S., & Galanti, M. T. (2018). Facilitating coproduction: the role of leadership in coproduction initiatives in the UK. Policy and Society, 37(3), 347–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2018.1414355

Corazzini, K., White H. Buhr G T,, McConnell E, & Colón-Emeric C (2015). Implementing Culture Change in Nursing Homes: An Adaptive Leadership Framework. The Gerontologist, 55(4), 616. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnt170

Cullen-Lester, K L., and Yammarino, F. (2016). Collective and Network Approaches to Leadership. Leadership Quarterly 27(2): 173–80.

Curtis, L. C., & Hodge, M. (1995). Ethics and boundaries in community support services: New challenges.New Directions for Mental Health Services, 1995(66), 43–60. https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.23319950206

Dionne, S. D., Sayama, H., Hao, C., & Bush, B. J. (2010). The role of leadership in shared mental model convergence and team performance improvement An agent-based computational model. Leadership Quarterly, 21(6), 1035–1049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.10.007

Silvia, C. (2011). Collaborative Governance Concepts for Successful Network Leadership. State and Local Government Review, 43(1), 66–71. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/870998417?accountid=14987

Fairhurst, Gail (2007). Discursive Leadership. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Getha-Taylor, H., Fowles, J., Silvia, C., & Merritt, C. C. (2015). Considering the Effects of Time on Leadership Development: A Local Government Training Evaluation. Public Personnel Management, 44(3), 295–316.https://doi.org/10.1177/0091026015586265

Getha-Taylor, H., & Morse, R. S. (2013). Collaborative Leadership Development for Local Government Officials: Exploring Competencies and Program Impact. Public Administration Quarterly, 37(1), 72–103. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/1429625262?accountid=14987

Gibney, J Copeland, S & Murie, A (2009) Toward a “New” Strategic Strategic Leadership of Place for the Knowledge-based Economy. Leadership,5(1), 5–23

Heifetz, R., Grashow, A. & Linsky, M., 2009. The Practice of Adaptive Leadership; Tools and Tactics for Changing Your Organization and the World. Boston: Harvard Business Press.

Horwath, J., & Morrison, T. (2007). Collaboration, integration and change in children’s services: Critical issues and key ingredients. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31(1), 55–69. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.01.007

Joo, B.-K. (Brian). (2010). Organizational commitment for knowledge workers: The roles of perceived organizational learning culture, leader–member exchange quality, and turnover intention. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 21(1), 69–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.20031

Joo, B.-K. (Brian). (2012). Leader–Member Exchange Quality and In-Role Job Performance: The Moderating Role of Learning Organization Culture. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 19(1), 25–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051811422233

Mandell, Myrna P., and Robyn Keast. 2009. A New Look at Leadership in Collaborative Networks: Process Catalysts. In Public Sector Leadership: International Challenges and Perspectives, edited by Jeffrey A. Raffel, Peter Leisink, and Anthony E. Middlebrooks, 163–78. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar

Kotze, M., & Venter, I. (2011). Differences in emotional intelligence between effective and ineffective leaders in the public sector: an empirical study. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 77(2), 397–427. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0020852311399857

Lee, P., Gillespie, N., Mann, L., & Wearing, A. (2010). Leadership and trust: Their effect on knowledge sharing and team performance. Management Learning, 41(4), 473–491. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507610362036

Morrison, K. (2010). Complexity Theory, School Leadership and Management: Questions for Theory and Practice. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 38(3), 374–393.

Morse, Ricardo S. (2010). Integrative Public Leadership: Catalyzing Collaboration to Create Public Value. Leadership Quarterly 21(2): 231–45

O’Leary, R., Bingham, L. B., & Choi, Y. (2010). Teaching Collaborative Leadership: Ideas and Lessons for the Field. Journal of Public Affairs Education - J-PAE, 16(4), 565–592.

Ospina, S. M. (2017). Collective Leadership and Context in Public Administration: Bridging Public Leadership Research and Leadership Studies. Public Administration Review, 77(2), 275–286

Storch, J., Makaroff, K. S., Pauly, B., & Newton, L. (2013). Take me to my leader: The importance of ethical leadership among formal nurse leaders. Nurs Ethics, 20(2), 150–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733012474291

Tong, C. E., Franke, T., Larcombe, K., & Gould, J. S. (2018). Fostering Inter-Agency Collaboration for the Delivery of Community-Based Services for Older Adults. British Journal of Social Work, 48(2), 390–411. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcx044

Uhl-Bien, Mary, Russ Marion, and Bill McKelvey. 2007. Complexity Leadership Theory: Shifting Leadership from the Industrial Age to the Knowledge Era. Leadership Quarterly 18(4): 298–318

Uhl-Bien, Mary, and Russ Marion. 2009. Complexity Leadership in Bureaucratic Forms of Organizing: A Meso Model. Leadership Quarterly 20(4): 631–50

Uster, A., Beeri, I., & Vashdi, D. (2019). Don’t push too hard. Examining the managerial behaviours of local authorities in collaborative networks with nonprofit organisations. Local Government Studies, 45(1), 124–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2018.1533820

Wang, L., Tao, H., Bowers, B. J., Brown, R., & Zhang, Y. (2018). When nurse emotional intelligence matters: How transformational leadership influences intent to stay. Journal of Nursing Management, 26(4), 358–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12509

Is this page useful?

- Yes this page is useful

- No this page is not useful

Help us improve GOV.UK

Don’t include personal or financial information like your National Insurance number or credit card details.

To help us improve GOV.UK, we’d like to know more about your visit today. Please fill in this survey (opens in a new tab) .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Wiley Open Access Collection

An integrative review of leadership competencies and attributes in advanced nursing practice

Maud heinen.

1 Radboud University Medical Center, Radboud Institute for Health Sciences, Scientific Institute for Quality of Healthcare, Nijmegen The Netherlands

Catharina van Oostveen

2 Spaarne Gasthuis Hospital, Spaarne Gasthuis Academy, Haarlem The Netherlands

3 Erasmus School of Health Policy & Management, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Rotterdam The Netherlands

Jeroen Peters

4 Hogeschool van Arnhem en Nijmegen, HAN University of Applied Sciences, Nijmegen The Netherlands

Hester Vermeulen

5 HAN University of Applied Sciences, Nijmegen The Netherlands

Associated Data

To establish what leadership competencies are expected of master level‐educated nurses like the Advanced Practice Nurses and the Clinical Nurse Leaders as described in the international literature.

Developments in health care ask for well‐trained nurse leaders. Advanced Practice Nurses and Clinical Nurse Leaders are ideally positioned to lead healthcare reform in nursing. Nurses should be adequately equipped for this role based on internationally defined leadership competencies. Therefore, identifying leadership competencies and related attributes internationally is needed.

Integrative review.

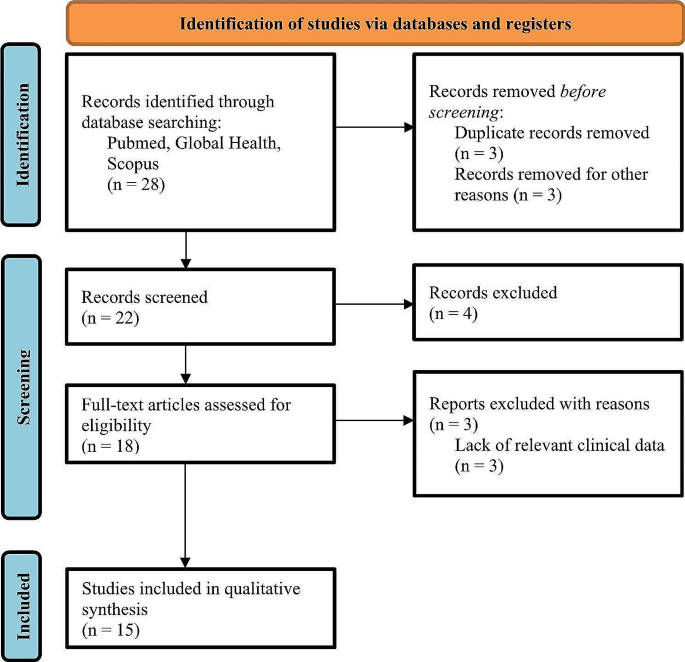

Embase, Medline and CINAHL databases were searched (January 2005–December 2018). Also, websites of international professional nursing organizations were searched for frameworks on leadership competencies. Study and framework selection, identification of competencies, quality appraisal of included studies and analysis of data were independently conducted by two researchers.

Fifteen studies and seven competency frameworks were included. Synthesis of 150 identified competencies led to a set of 30 core competencies in the clinical, professional, health systems. and health policy leadership domains. Most competencies fitted in one single domain the health policy domain contained the least competencies.

Conclusions

This synthesis of 30 core competencies within four leadership domains can be used for further development of evidence‐based curricula on leadership. Next steps include further refining of competencies, addressing gaps, and the linking of knowledge, skills, and attributes.

These findings contribute to leadership development for Advanced Practice Nurses and Clinical Nurse Leaders while aiming at improved health service delivery and guiding of health policies and reforms.

1. INTRODUCTION

Developments in health care, like a growing number of patients with chronic diseases, an increased complexity of patients, a stronger focus on person‐centred care and a demand for less institutionalized care ask for well‐trained master level‐educated nurses operating as partners in integrated care teams, with leadership qualities at all levels of the healthcare system. Changes in health care are also underlined by a definition of health as proposed by Huber et al. (Huber et al., 2011 ) where health is defined as ‘the ability to adapt and self manage in the face of social, physical and emotional challenges’ as a refinement of the World Health Organization (WHO) definition where health is ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well being’ (WHO, 1948 ). This stipulates the de‐medicalization of health care and society and emphasizes the need for change in the way health care is organized. Also the Institute of Medicine with their report on ‘The Future of Nursing’ supports the urge for nurses to take their roles to address changes in health care (IOM, 2011 ). However leading change is a complex and not yet well understood process (Nelson‐Brantley & Ford, 2017 ). Therefore, especially master level‐educated nurses have to be trained in leadership based on internationally established leadership competencies. This review investigates what leadership competencies are expected from and can be identified for master educated nurses from an international perspective.

1.1. Background

Clinical nurses who are trained at master's level, for example, Advanced Practice Nurses (APNs) and Clinical Nurse Leaders (CNLs), are in a unique position to take a leadership role, in collaboration with other healthcare professionals, to shape healthcare reform, as they use extended and expanded skills and are trained to focus on improved patient outcomes, the application of evidence‐based practice and assessing cost‐effectiveness of care (Stanley et al., 2008 ). The focus of this review is on APNs and CNLs, where APN is regarded as a general designation for all nurses with an advanced degree in a nursing program, that is, Certified Nurse Practitioner (NP), Certified Registered Nurse Anaesthetist, Certified Nurse Midwife and Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS) (APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008 ) . APNs are prepared with specialized education in a defined clinical area of practice. With APN in this review, we refer to the NP and the CNS. The CNL is educated to improve the quality of care and coordinate care in general through collaboration at the microsystems level in the entire healthcare team (APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2007 ). Both groups of professionals are trained to integrate science in practice and education, have increased degrees of autonomy in judgments and clinical interventions and are expected to be engaged in collaborative and inter professional practices to achieve the best outcomes for patients, personnel and organization (American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2011 ). They are also expected to substantially contribute to clinical outcomes through, that is, continuous quality improvement in patient care and creating a supportive environment for their colleagues, and to contribute to the development of their profession, healthcare systems and healthcare policy. (American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2004 ; Bender, Williams, & Su, 2016 ; Hamric, Hanson, Tracy, & O'Grady, 2014 ). Therefore developing leadership competencies is an essential prerequisite for these master educated nurses, APNs however appear to experience a lot of difficulties in enacting their leadership role (Begley, Murphy, Higgins, & Cooney, 2014 ; Elliott, Begley, Sheaf, & Higgins, 2016a ).

Leadership is subject of many discussions can be regarded from different perspectives and is mostly related to specific contexts. Hence, there is no single definition applicable to all settings and professions. Leadership is mostly regarded in relation to managing a team or organization (Gosling & Mintzberg, 2003 ) but can also be defined as a set of personal skills or traits, or focussing on the relation between leaders and followers (Alimo‐Metcalfe & Alban‐Metcalfe, 2004 ; Bolden, 2004 ). Transformational and situational leadership are also commonly used concepts where transformational leadership is regarded as the process of leading and inspiring a group to achieve a common goal (Northouse, 2014 ) and situational leadership is focusing on the interaction between individual leadership styles and the features of the environment or situation where the leader is operating. (Fiedler, 1967 ; Hamric et al., 2014 ; Lynch, McCormack, & McCance, 2011 ). In this review, leadership is regarded as a process where nurses can develop observable leadership competencies and attributes needed to improve patient outcomes, and personnel and organizational outcomes (Kouzes & Posner, 2012 ). This implies that leadership competencies can be viewed as intended and defined outcomes of learning and that leadership and leadership competencies are not restricted to one single theory. A competency can be defined as ‘an expected level of performance that results from an integration of knowledge, skills, abilities and judgment’ (American Nurses Association, 2013 ).

The lack of an unambiguous definition of leadership in clinical practice, including clearly defined leadership competencies in nursing, is reflected in education. For most training programs and curricula, it is unclear whether the profiles used in education are up‐to‐date and aiming` at internationally accepted leadership competencies with evidence‐based methods to achieve these competencies. To enhance leadership qualities in master educated nurses, it is necessary to explicitly define what leadership competencies are expected from APNs and CNLs (Delamaire & Lafortune, 2010 ). Identifying and establishing internationally agreed on leadership competencies in master educated nurses is a first step to developing evidence‐based curricula on leadership (Falk‐Rafael, 2005 ; Vance & Larson, 2002 ). Such a curriculum facilitates APN and CNL students to not only become competent clinical and professional leaders but also well‐prepared for organizational systems and political leadership (Hamric et al., 2014 ). As such, it enables them to have a positive and significant impact on patient, personnel and organizational level outcomes. Accordingly, this review aims to identify and integrate leadership competencies of the master level‐educated nurse (APN and CNL) from an international perspective.

2. THE REVIEW

Based on the decision flowchart developed by Flemming et al. (Flemming, Booth, Hannes, Cargo, & Noyes, 2018 ), this review was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses statement (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009 ) and the Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research statement (Tong, Flemming, McInnes, Oliver, & Craig, 2012 ).

To identify and integrate leadership competencies of the master level‐educated nurse (APN and CNL) from an international perspective.

2.2. Design

An integrative review design was used, which allows for the combination of various study designs and data sources to be included. In using this methodology, a rigorous and systematic approach is ensured (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005 ). We followed the five stage methodology by Whittemore and Knafl (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005 ), however for the data synthesis phase, we used the four leadership domains of Hamric et al (Hamric et al., 2014 ; Hamric, Spross, & Hanson, 2009 ) as an a priori framework to integrate the extracted data.