- Franklin University |

- Help & Support |

- Locations & Maps |

- | Research Guides

To access Safari eBooks,

- Select not listed in the Select Your Institution drop down menu.

- Enter your Franklin email address and click Go

- click "Already a user? Click here" link

- Enter your Franklin email and the password you used to create your Safari account.

Continue Close

Literature Review

- Getting Started

- Framing the Literature Review

Literature Review Process

- Mistakes to Avoid & Additional Help

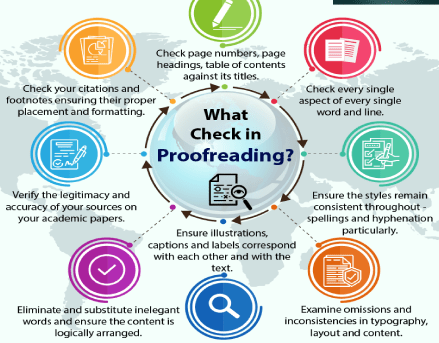

The structure of a literature review should include the following :

- An overview of the subject, issue or theory under consideration, along with the objectives of the literature review,

- Division of works under review into themes or categories (e.g. works that support of a particular position, those against, and those offering alternative approaches entirely),

- An explanation of how each work is similar to and how it varies from the others,

- Conclusions as to which pieces are best considered in their argument, are most convincing of their opinions, and make the greatest contribution to the understanding and development of their area of research

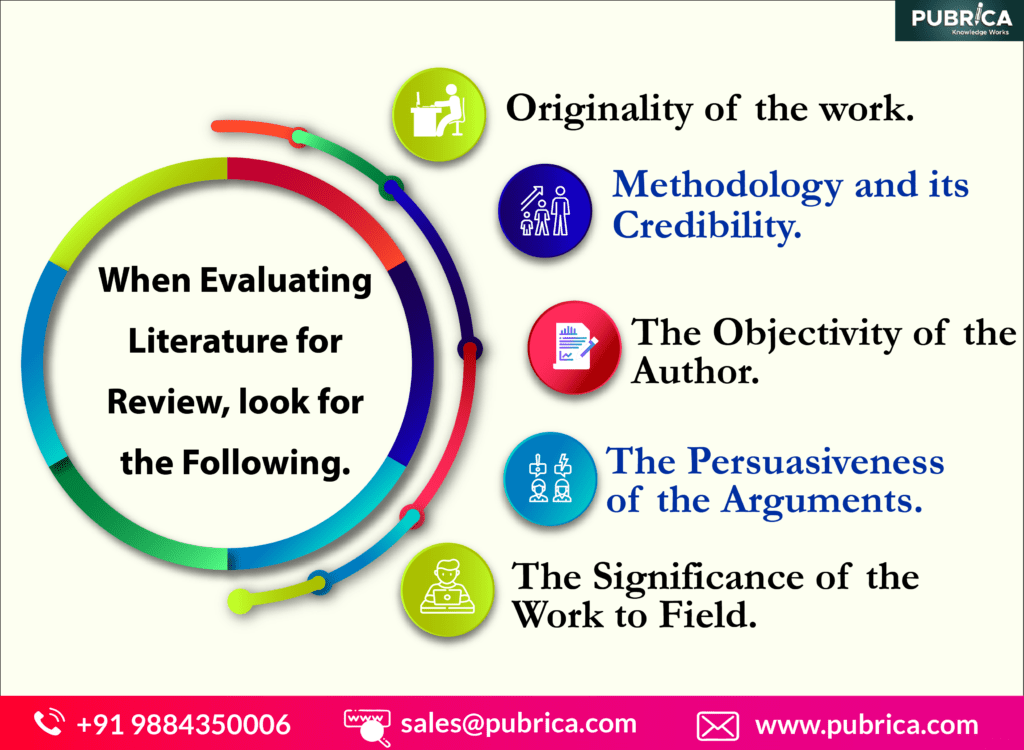

The critical evaluation of each work should consider :

- Provenance -- what are the author's credentials? Are the author's arguments supported by evidence (e.g. primary historical material, case studies, narratives, statistics, recent scientific findings)?

- Objectivity -- is the author's perspective even-handed or prejudicial? Is contrary data considered or is certain pertinent information ignored to prove the author's point?

- Persuasiveness -- which of the author's theses are most/least convincing?

- Value -- are the author's arguments and conclusions convincing? Does the work ultimately contribute in any significant way to an understanding of the subject?

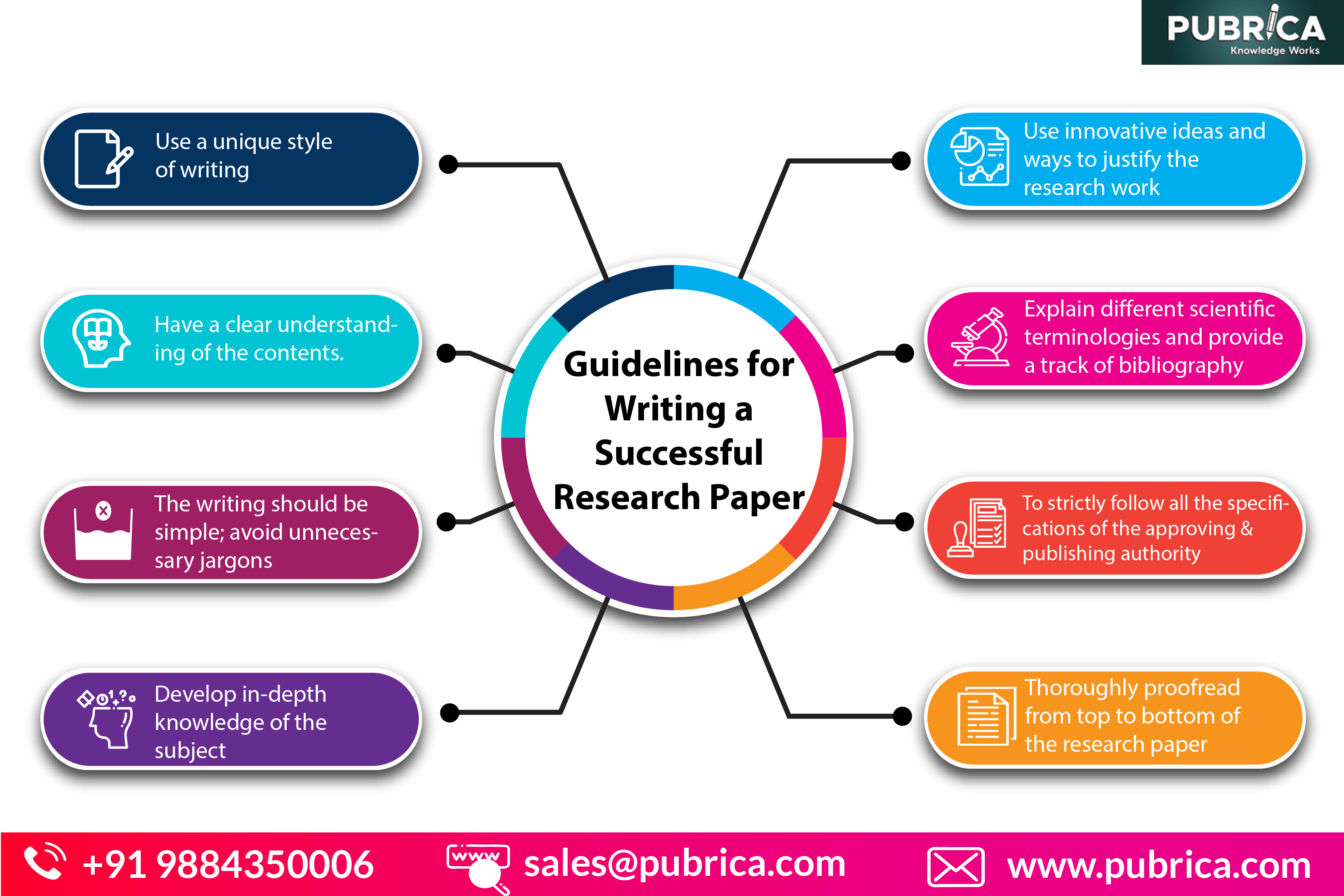

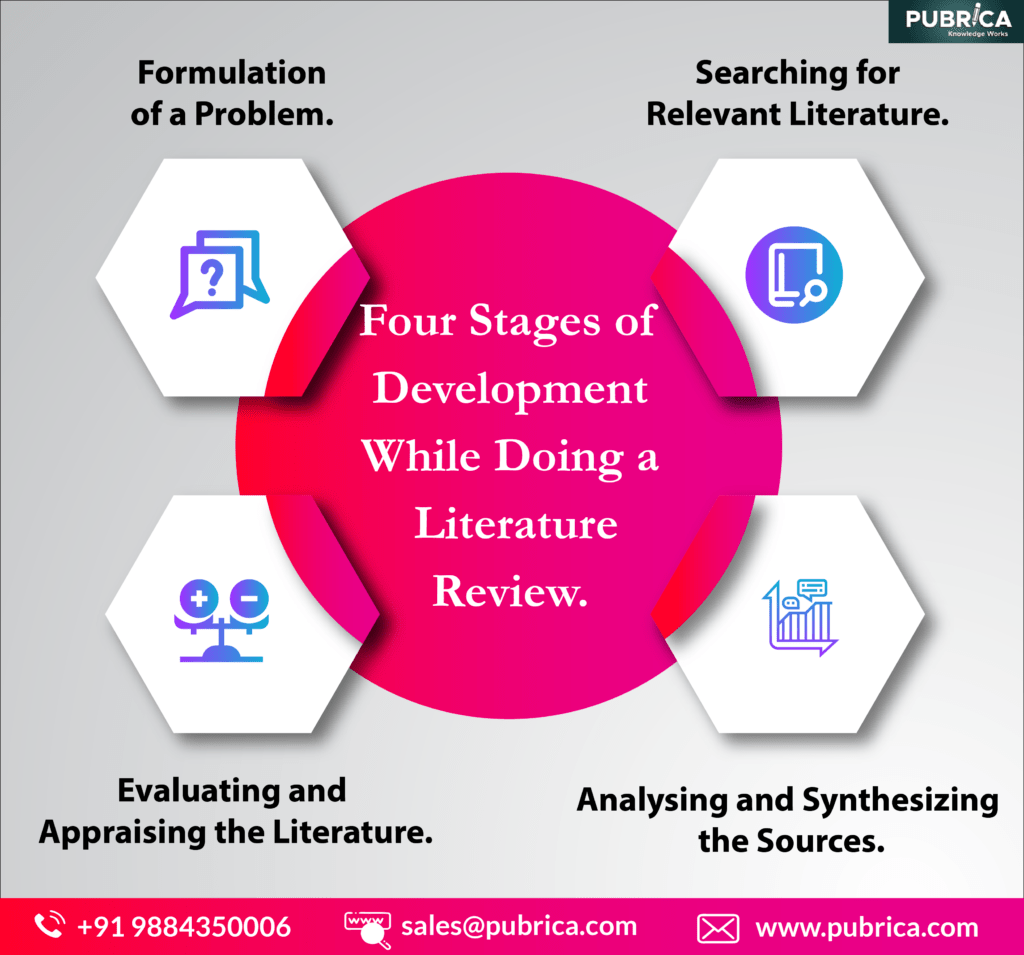

Development of the Literature Review

Four stages:.

- Introduce the reader to the importance of the topic being studied . The reader is oriented to the significance of the study and the research questions or hypotheses to follow.

- Places the problem into a particular context that defines the parameters of what is to be investigated.

- Provides the framework for reporting the results and indicates what is probably necessary to conduct the study and explain how the findings will present this information.

- Literature search -- finding materials relevant to the subject being explored.

- Evaluation of resources -- determining which literature makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the topic.

- Analysis and interpretation -- discussing the findings and conclusions of pertinent literature.

Consider the following issues before writing the literature review:

Sources and expectations. if your assignment is not very specific about what form your literature review should take, seek clarification from your professor by asking these questions:.

- Roughly how many sources should I include?

- What types of sources should I review (books, journal articles, websites)?

- Should I summarize, synthesize, or critique your sources by discussing a common theme or issue?

- Should I evaluate the sources?

- Should I provide subheadings and other background information, such as definitions and/or a history?

Find Models. When reviewing the current literature, examine how authors in your discipline or area of interest have organized their literature reviews. Read not only for information, but also to get a sense of the types of themes you might want to look for in your own research review.

Narrow the topic. the narrower your topic, the easier it will be to limit the number of sources you need to read in order to obtain a good survey of relevant resources., consider whether your sources are current and applicable. s ome disciplines require that you use information that is as current as possible. this is very common in the sciences where research conducted only two years ago could be obsolete. however, when writing a review in the social sciences, a survey of the history of the literature may be what is needed because what is important is how perspectives have changed over the years or within a certain time period. try sorting through some other current bibliographies or literature reviews in the field to get a sense of what your discipline expects. you can also use this method to consider what is consider by scholars to be a "hot topic" and what is not., follow the bread crumb trail. the bibliography or reference section of sources you read are excellent entry points for further exploration. you might find resourced listed in a bibliography that points you in the direction you wish to take your own research., ways to organize your literature review, chronologically: .

If your review follows the chronological method, you could write about the materials according to when they were published or the time period they cover.

By Publication:

Order your sources chronologically by publication date, only if the order demonstrates a more important trend. For instance, you could order a review of literature on environmental studies of brown fields if the progression revealed, for example, a change in the soil collection practices of the researchers who wrote and/or conducted the studies.

Conceptual Categories:

The literature review is organized around a topic or issue, rather than the progression of time. However, progression of time may still be an important factor in a thematic review. For example, a review of the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics could focus on the development of online political satire. While the study focuses on one topic, the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics, it will still be organized chronologically reflecting technological developments in media. The only difference here between a "chronological" and a "thematic" approach is what is emphasized the most.

Methodological:

A methodological approach focuses on the methods utilized by the researcher. A methodological scope will influence either the types of documents in the review or the way in which these documents are discussed.

Sections of Your Literature Review:

Once you've decided on the organizational method for your literature review, the sections you need to include should be easy to figure out because they arise from your organizational strategy.

Here are examples of other sections you may need to include depending on the type of review you write:

- Current Situation : information necessary to understand the topic or focus of the literature review.

- History : the chronological progression of the field, the literature, or an idea that is necessary to understand the literature review, if the body of the literature review is not already a chronology.

- Selection Methods : the criteria you used to select (and perhaps exclude) sources in your literature review. For instance, you might explain that your review includes only peer-reviewed articles and journals.

- Standards : the way in which you present your information.

- Questions for Further Research : What questions about the field has the review sparked? How will you further your research as a result of the review?

Writing Your Literature Review

Once you've settled on how to organize your literature review, you're ready to write each section. When writing your review, keep in mind these issues.

Use Evidence:

A literature review in this sense is just like any other academic research paper. Your interpretation of the available sources must be backed up with evidence to show that what you are saying is valid.

Be Selective:

Select only the most important points in each source to highlight in the review. The type of information you choose to mention should relate directly to the research problem, whether it is thematic, methodological, or chronological.

Use Quotes Sparingly:

Some short quotes are okay if you want to emphasize a point, or if what the author said just cannot be rewritten in your own words. Sometimes you may need to quote certain terms that were coined by the author, not common knowledge, or taken directly from the study. Do not use extensive quotes as a substitute your own summary and interpretation of the literature.

Summarize and Synthesize:

Remember to summarize and synthesize your sources within each paragraph as well as throughout the review. Recapitulate important features of a research study, but then synthesize it by rephrasing the study's significance and relating it to their own work.

Keep Your Own Voice:

While the literature review presents others' ideas, your voice (the writer's) should remain front and center. For example, weave references to other sources into what you are writing but maintain your own voice by starting and ending the paragraph with your own ideas and wording.

Use Caution When Paraphrasing:

When paraphrasing a source that is not your own, be sure to represent the author's information or opinions accurately and in your own words. Even when paraphrasing an author’s work, you still must provide a citation to that work.

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: Mistakes to Avoid & Additional Help >>

- Last Updated: Oct 3, 2023 2:44 PM

- URL: https://guides.franklin.edu/LITREVIEW

- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

Steps in the literature review process.

- What is a literature review?

- Define your research question

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Analyze Results

- Librarian Support

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) Tools

- You may need to some exploratory searching of the literature to get a sense of scope, to determine whether you need to narrow or broaden your focus

- Identify databases that provide the most relevant sources, and identify relevant terms (controlled vocabularies) to add to your search strategy

- Finalize your research question

- Think about relevant dates, geographies (and languages), methods, and conflicting points of view

- Conduct searches in the published literature via the identified databases

- Check to see if this topic has been covered in other discipline's databases

- Examine the citations of on-point articles for keywords, authors, and previous research (via references) and cited reference searching.

- Save your search results in a citation management tool (such as Zotero, Mendeley or EndNote)

- De-duplicate your search results

- Make sure that you've found the seminal pieces -- they have been cited many times, and their work is considered foundational

- Check with your professor or a librarian to make sure your search has been comprehensive

- Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of individual sources and evaluate for bias, methodologies, and thoroughness

- Group your results in to an organizational structure that will support why your research needs to be done, or that provides the answer to your research question

- Develop your conclusions

- Are there gaps in the literature?

- Where has significant research taken place, and who has done it?

- Is there consensus or debate on this topic?

- Which methodological approaches work best?

- For example: Background, Current Practices, Critics and Proponents, Where/How this study will fit in

- Organize your citations and focus on your research question and pertinent studies

- Compile your bibliography

Note: The first four steps are the best points at which to contact a librarian. Your librarian can help you determine the best databases to use for your topic, assess scope, and formulate a search strategy.

Videos Tutorials about Literature Reviews

This 4.5 minute video from Academic Education Materials has a Creative Commons License and a British narrator.

Recommended Reading

- Last Updated: Jun 18, 2024 1:00 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved July 4, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 5. The Literature Review

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

A literature review surveys prior research published in books, scholarly articles, and any other sources relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, and by so doing, provides a description, summary, and critical evaluation of these works in relation to the research problem being investigated. Literature reviews are designed to provide an overview of sources you have used in researching a particular topic and to demonstrate to your readers how your research fits within existing scholarship about the topic.

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . Fourth edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2014.

Importance of a Good Literature Review

A literature review may consist of simply a summary of key sources, but in the social sciences, a literature review usually has an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis, often within specific conceptual categories . A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information in a way that informs how you are planning to investigate a research problem. The analytical features of a literature review might:

- Give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations,

- Trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates,

- Depending on the situation, evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant research, or

- Usually in the conclusion of a literature review, identify where gaps exist in how a problem has been researched to date.

Given this, the purpose of a literature review is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to understanding the research problem being studied.

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies.

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important].

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2011; Knopf, Jeffrey W. "Doing a Literature Review." PS: Political Science and Politics 39 (January 2006): 127-132; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012.

Types of Literature Reviews

It is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the primary studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally among scholars that become part of the body of epistemological traditions within the field.

In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews. Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are a number of approaches you could adopt depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study.

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply embedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews [see below].

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses or research problems. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication. This is the most common form of review in the social sciences.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical literature reviews focus on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [findings], but how they came about saying what they say [method of analysis]. Reviewing methods of analysis provides a framework of understanding at different levels [i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches, and data collection and analysis techniques], how researchers draw upon a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection, and data analysis. This approach helps highlight ethical issues which you should be aware of and consider as you go through your own study.

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyze data from the studies that are included in the review. The goal is to deliberately document, critically evaluate, and summarize scientifically all of the research about a clearly defined research problem . Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?" This type of literature review is primarily applied to examining prior research studies in clinical medicine and allied health fields, but it is increasingly being used in the social sciences.

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review helps to establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

NOTE: Most often the literature review will incorporate some combination of types. For example, a review that examines literature supporting or refuting an argument, assumption, or philosophical problem related to the research problem will also need to include writing supported by sources that establish the history of these arguments in the literature.

Baumeister, Roy F. and Mark R. Leary. "Writing Narrative Literature Reviews." Review of General Psychology 1 (September 1997): 311-320; Mark R. Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147; Petticrew, Mark and Helen Roberts. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide . Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 2006; Torracro, Richard. "Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples." Human Resource Development Review 4 (September 2005): 356-367; Rocco, Tonette S. and Maria S. Plakhotnik. "Literature Reviews, Conceptual Frameworks, and Theoretical Frameworks: Terms, Functions, and Distinctions." Human Ressource Development Review 8 (March 2008): 120-130; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Thinking About Your Literature Review

The structure of a literature review should include the following in support of understanding the research problem :

- An overview of the subject, issue, or theory under consideration, along with the objectives of the literature review,

- Division of works under review into themes or categories [e.g. works that support a particular position, those against, and those offering alternative approaches entirely],

- An explanation of how each work is similar to and how it varies from the others,

- Conclusions as to which pieces are best considered in their argument, are most convincing of their opinions, and make the greatest contribution to the understanding and development of their area of research.

The critical evaluation of each work should consider :

- Provenance -- what are the author's credentials? Are the author's arguments supported by evidence [e.g. primary historical material, case studies, narratives, statistics, recent scientific findings]?

- Methodology -- were the techniques used to identify, gather, and analyze the data appropriate to addressing the research problem? Was the sample size appropriate? Were the results effectively interpreted and reported?

- Objectivity -- is the author's perspective even-handed or prejudicial? Is contrary data considered or is certain pertinent information ignored to prove the author's point?

- Persuasiveness -- which of the author's theses are most convincing or least convincing?

- Validity -- are the author's arguments and conclusions convincing? Does the work ultimately contribute in any significant way to an understanding of the subject?

II. Development of the Literature Review

Four Basic Stages of Writing 1. Problem formulation -- which topic or field is being examined and what are its component issues? 2. Literature search -- finding materials relevant to the subject being explored. 3. Data evaluation -- determining which literature makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the topic. 4. Analysis and interpretation -- discussing the findings and conclusions of pertinent literature.

Consider the following issues before writing the literature review: Clarify If your assignment is not specific about what form your literature review should take, seek clarification from your professor by asking these questions: 1. Roughly how many sources would be appropriate to include? 2. What types of sources should I review (books, journal articles, websites; scholarly versus popular sources)? 3. Should I summarize, synthesize, or critique sources by discussing a common theme or issue? 4. Should I evaluate the sources in any way beyond evaluating how they relate to understanding the research problem? 5. Should I provide subheadings and other background information, such as definitions and/or a history? Find Models Use the exercise of reviewing the literature to examine how authors in your discipline or area of interest have composed their literature review sections. Read them to get a sense of the types of themes you might want to look for in your own research or to identify ways to organize your final review. The bibliography or reference section of sources you've already read, such as required readings in the course syllabus, are also excellent entry points into your own research. Narrow the Topic The narrower your topic, the easier it will be to limit the number of sources you need to read in order to obtain a good survey of relevant resources. Your professor will probably not expect you to read everything that's available about the topic, but you'll make the act of reviewing easier if you first limit scope of the research problem. A good strategy is to begin by searching the USC Libraries Catalog for recent books about the topic and review the table of contents for chapters that focuses on specific issues. You can also review the indexes of books to find references to specific issues that can serve as the focus of your research. For example, a book surveying the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict may include a chapter on the role Egypt has played in mediating the conflict, or look in the index for the pages where Egypt is mentioned in the text. Consider Whether Your Sources are Current Some disciplines require that you use information that is as current as possible. This is particularly true in disciplines in medicine and the sciences where research conducted becomes obsolete very quickly as new discoveries are made. However, when writing a review in the social sciences, a survey of the history of the literature may be required. In other words, a complete understanding the research problem requires you to deliberately examine how knowledge and perspectives have changed over time. Sort through other current bibliographies or literature reviews in the field to get a sense of what your discipline expects. You can also use this method to explore what is considered by scholars to be a "hot topic" and what is not.

III. Ways to Organize Your Literature Review

Chronology of Events If your review follows the chronological method, you could write about the materials according to when they were published. This approach should only be followed if a clear path of research building on previous research can be identified and that these trends follow a clear chronological order of development. For example, a literature review that focuses on continuing research about the emergence of German economic power after the fall of the Soviet Union. By Publication Order your sources by publication chronology, then, only if the order demonstrates a more important trend. For instance, you could order a review of literature on environmental studies of brown fields if the progression revealed, for example, a change in the soil collection practices of the researchers who wrote and/or conducted the studies. Thematic [“conceptual categories”] A thematic literature review is the most common approach to summarizing prior research in the social and behavioral sciences. Thematic reviews are organized around a topic or issue, rather than the progression of time, although the progression of time may still be incorporated into a thematic review. For example, a review of the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics could focus on the development of online political satire. While the study focuses on one topic, the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics, it would still be organized chronologically reflecting technological developments in media. The difference in this example between a "chronological" and a "thematic" approach is what is emphasized the most: themes related to the role of the Internet in presidential politics. Note that more authentic thematic reviews tend to break away from chronological order. A review organized in this manner would shift between time periods within each section according to the point being made. Methodological A methodological approach focuses on the methods utilized by the researcher. For the Internet in American presidential politics project, one methodological approach would be to look at cultural differences between the portrayal of American presidents on American, British, and French websites. Or the review might focus on the fundraising impact of the Internet on a particular political party. A methodological scope will influence either the types of documents in the review or the way in which these documents are discussed.

Other Sections of Your Literature Review Once you've decided on the organizational method for your literature review, the sections you need to include in the paper should be easy to figure out because they arise from your organizational strategy. In other words, a chronological review would have subsections for each vital time period; a thematic review would have subtopics based upon factors that relate to the theme or issue. However, sometimes you may need to add additional sections that are necessary for your study, but do not fit in the organizational strategy of the body. What other sections you include in the body is up to you. However, only include what is necessary for the reader to locate your study within the larger scholarship about the research problem.

Here are examples of other sections, usually in the form of a single paragraph, you may need to include depending on the type of review you write:

- Current Situation : Information necessary to understand the current topic or focus of the literature review.

- Sources Used : Describes the methods and resources [e.g., databases] you used to identify the literature you reviewed.

- History : The chronological progression of the field, the research literature, or an idea that is necessary to understand the literature review, if the body of the literature review is not already a chronology.

- Selection Methods : Criteria you used to select (and perhaps exclude) sources in your literature review. For instance, you might explain that your review includes only peer-reviewed [i.e., scholarly] sources.

- Standards : Description of the way in which you present your information.

- Questions for Further Research : What questions about the field has the review sparked? How will you further your research as a result of the review?

IV. Writing Your Literature Review

Once you've settled on how to organize your literature review, you're ready to write each section. When writing your review, keep in mind these issues.

Use Evidence A literature review section is, in this sense, just like any other academic research paper. Your interpretation of the available sources must be backed up with evidence [citations] that demonstrates that what you are saying is valid. Be Selective Select only the most important points in each source to highlight in the review. The type of information you choose to mention should relate directly to the research problem, whether it is thematic, methodological, or chronological. Related items that provide additional information, but that are not key to understanding the research problem, can be included in a list of further readings . Use Quotes Sparingly Some short quotes are appropriate if you want to emphasize a point, or if what an author stated cannot be easily paraphrased. Sometimes you may need to quote certain terminology that was coined by the author, is not common knowledge, or taken directly from the study. Do not use extensive quotes as a substitute for using your own words in reviewing the literature. Summarize and Synthesize Remember to summarize and synthesize your sources within each thematic paragraph as well as throughout the review. Recapitulate important features of a research study, but then synthesize it by rephrasing the study's significance and relating it to your own work and the work of others. Keep Your Own Voice While the literature review presents others' ideas, your voice [the writer's] should remain front and center. For example, weave references to other sources into what you are writing but maintain your own voice by starting and ending the paragraph with your own ideas and wording. Use Caution When Paraphrasing When paraphrasing a source that is not your own, be sure to represent the author's information or opinions accurately and in your own words. Even when paraphrasing an author’s work, you still must provide a citation to that work.

V. Common Mistakes to Avoid

These are the most common mistakes made in reviewing social science research literature.

- Sources in your literature review do not clearly relate to the research problem;

- You do not take sufficient time to define and identify the most relevant sources to use in the literature review related to the research problem;

- Relies exclusively on secondary analytical sources rather than including relevant primary research studies or data;

- Uncritically accepts another researcher's findings and interpretations as valid, rather than examining critically all aspects of the research design and analysis;

- Does not describe the search procedures that were used in identifying the literature to review;

- Reports isolated statistical results rather than synthesizing them in chi-squared or meta-analytic methods; and,

- Only includes research that validates assumptions and does not consider contrary findings and alternative interpretations found in the literature.

Cook, Kathleen E. and Elise Murowchick. “Do Literature Review Skills Transfer from One Course to Another?” Psychology Learning and Teaching 13 (March 2014): 3-11; Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . London: SAGE, 2011; Literature Review Handout. Online Writing Center. Liberty University; Literature Reviews. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. and Rebecca Frels. Seven Steps to a Comprehensive Literature Review: A Multimodal and Cultural Approach . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2016; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012; Randolph, Justus J. “A Guide to Writing the Dissertation Literature Review." Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation. vol. 14, June 2009; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016; Taylor, Dena. The Literature Review: A Few Tips On Conducting It. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Writing a Literature Review. Academic Skills Centre. University of Canberra.

Writing Tip

Break Out of Your Disciplinary Box!

Thinking interdisciplinarily about a research problem can be a rewarding exercise in applying new ideas, theories, or concepts to an old problem. For example, what might cultural anthropologists say about the continuing conflict in the Middle East? In what ways might geographers view the need for better distribution of social service agencies in large cities than how social workers might study the issue? You don’t want to substitute a thorough review of core research literature in your discipline for studies conducted in other fields of study. However, particularly in the social sciences, thinking about research problems from multiple vectors is a key strategy for finding new solutions to a problem or gaining a new perspective. Consult with a librarian about identifying research databases in other disciplines; almost every field of study has at least one comprehensive database devoted to indexing its research literature.

Frodeman, Robert. The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity . New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Another Writing Tip

Don't Just Review for Content!

While conducting a review of the literature, maximize the time you devote to writing this part of your paper by thinking broadly about what you should be looking for and evaluating. Review not just what scholars are saying, but how are they saying it. Some questions to ask:

- How are they organizing their ideas?

- What methods have they used to study the problem?

- What theories have been used to explain, predict, or understand their research problem?

- What sources have they cited to support their conclusions?

- How have they used non-textual elements [e.g., charts, graphs, figures, etc.] to illustrate key points?

When you begin to write your literature review section, you'll be glad you dug deeper into how the research was designed and constructed because it establishes a means for developing more substantial analysis and interpretation of the research problem.

Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1 998.

Yet Another Writing Tip

When Do I Know I Can Stop Looking and Move On?

Here are several strategies you can utilize to assess whether you've thoroughly reviewed the literature:

- Look for repeating patterns in the research findings . If the same thing is being said, just by different people, then this likely demonstrates that the research problem has hit a conceptual dead end. At this point consider: Does your study extend current research? Does it forge a new path? Or, does is merely add more of the same thing being said?

- Look at sources the authors cite to in their work . If you begin to see the same researchers cited again and again, then this is often an indication that no new ideas have been generated to address the research problem.

- Search Google Scholar to identify who has subsequently cited leading scholars already identified in your literature review [see next sub-tab]. This is called citation tracking and there are a number of sources that can help you identify who has cited whom, particularly scholars from outside of your discipline. Here again, if the same authors are being cited again and again, this may indicate no new literature has been written on the topic.

Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. and Rebecca Frels. Seven Steps to a Comprehensive Literature Review: A Multimodal and Cultural Approach . Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2016; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

- << Previous: Theoretical Framework

- Next: Citation Tracking >>

- Last Updated: Jul 3, 2024 10:07 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library

- Collections

- Research Help

YSN Doctoral Programs: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Biomedical Databases

- Global (Public Health) Databases

- Soc. Sci., History, and Law Databases

- Grey Literature

- Trials Registers

- Data and Statistics

- Public Policy

- Google Tips

- Recommended Books

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an integrated analysis -- not just a summary-- of scholarly writings and other relevant evidence related directly to your research question. That is, it represents a synthesis of the evidence that provides background information on your topic and shows a association between the evidence and your research question.

A literature review may be a stand alone work or the introduction to a larger research paper, depending on the assignment. Rely heavily on the guidelines your instructor has given you.

Why is it important?

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Identifies critical gaps and points of disagreement.

- Discusses further research questions that logically come out of the previous studies.

APA7 Style resources

APA Style Blog - for those harder to find answers

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by your central research question. The literature represents background and research developments related to a specific research question, interpreted and analyzed by you in a synthesized way.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow. Is it manageable?

- Begin writing down terms that are related to your question. These will be useful for searches later.

- If you have the opportunity, discuss your topic with your professor and your class mates.

2. Decide on the scope of your review

How many studies do you need to look at? How comprehensive should it be? How many years should it cover?

- This may depend on your assignment. How many sources does the assignment require?

3. Select the databases you will use to conduct your searches.

Make a list of the databases you will search.

Where to find databases:

- use the tabs on this guide

- Find other databases in the Nursing Information Resources web page

- More on the Medical Library web page

- ... and more on the Yale University Library web page

4. Conduct your searches to find the evidence. Keep track of your searches.

- Use the key words in your question, as well as synonyms for those words, as terms in your search. Use the database tutorials for help.

- Save the searches in the databases. This saves time when you want to redo, or modify, the searches. It is also helpful to use as a guide is the searches are not finding any useful results.

- Review the abstracts of research studies carefully. This will save you time.

- Use the bibliographies and references of research studies you find to locate others.

- Check with your professor, or a subject expert in the field, if you are missing any key works in the field.

- Ask your librarian for help at any time.

- Use a citation manager, such as EndNote as the repository for your citations. See the EndNote tutorials for help.

Review the literature

Some questions to help you analyze the research:

- What was the research question of the study you are reviewing? What were the authors trying to discover?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze its literature review, the samples and variables used, the results, and the conclusions.

- Does the research seem to be complete? Could it have been conducted more soundly? What further questions does it raise?

- If there are conflicting studies, why do you think that is?

- How are the authors viewed in the field? Has this study been cited? If so, how has it been analyzed?

Tips:

- Review the abstracts carefully.

- Keep careful notes so that you may track your thought processes during the research process.

- Create a matrix of the studies for easy analysis, and synthesis, across all of the studies.

- << Previous: Recommended Books

- Last Updated: Jun 20, 2024 9:08 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/YSNDoctoral

Research Process :: Step by Step

- Introduction

- Select Topic

- Identify Keywords

- Background Information

- Develop Research Questions

- Refine Topic

- Search Strategy

- Popular Databases

- Evaluate Sources

- Types of Periodicals

- Reading Scholarly Articles

- Primary & Secondary Sources

- Organize / Take Notes

- Writing & Grammar Resources

- Annotated Bibliography

- Literature Review

- Citation Styles

- Paraphrasing

- Privacy / Confidentiality

- Research Process

- Selecting Your Topic

- Identifying Keywords

- Gathering Background Info

- Evaluating Sources

Organize the literature review into sections that present themes or identify trends, including relevant theory. You are not trying to list all the material published, but to synthesize and evaluate it according to the guiding concept of your thesis or research question.

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. Occasionally you will be asked to write one as a separate assignment, but more often it is part of the introduction to an essay, research report, or thesis. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries

A literature review must do these things:

- be organized around and related directly to the thesis or research question you are developing

- synthesize results into a summary of what is and is not known

- identify areas of controversy in the literature

- formulate questions that need further research

Ask yourself questions like these:

- What is the specific thesis, problem, or research question that my literature review helps to define?

- What type of literature review am I conducting? Am I looking at issues of theory? methodology? policy? quantitative research (e.g. on the effectiveness of a new procedure)? qualitative research (e.g., studies of loneliness among migrant workers)?

- What is the scope of my literature review? What types of publications am I using (e.g., journals, books, government documents, popular media)? What discipline am I working in (e.g., nursing psychology, sociology, medicine)?

- How good was my information seeking? Has my search been wide enough to ensure I've found all the relevant material? Has it been narrow enough to exclude irrelevant material? Is the number of sources I've used appropriate for the length of my paper?

- Have I critically analyzed the literature I use? Do I follow through a set of concepts and questions, comparing items to each other in the ways they deal with them? Instead of just listing and summarizing items, do I assess them, discussing strengths and weaknesses?

- Have I cited and discussed studies contrary to my perspective?

- Will the reader find my literature review relevant, appropriate, and useful?

Ask yourself questions like these about each book or article you include:

- Has the author formulated a problem/issue?

- Is it clearly defined? Is its significance (scope, severity, relevance) clearly established?

- Could the problem have been approached more effectively from another perspective?

- What is the author's research orientation (e.g., interpretive, critical science, combination)?

- What is the author's theoretical framework (e.g., psychological, developmental, feminist)?

- What is the relationship between the theoretical and research perspectives?

- Has the author evaluated the literature relevant to the problem/issue? Does the author include literature taking positions she or he does not agree with?

- In a research study, how good are the basic components of the study design (e.g., population, intervention, outcome)? How accurate and valid are the measurements? Is the analysis of the data accurate and relevant to the research question? Are the conclusions validly based upon the data and analysis?

- In material written for a popular readership, does the author use appeals to emotion, one-sided examples, or rhetorically-charged language and tone? Is there an objective basis to the reasoning, or is the author merely "proving" what he or she already believes?

- How does the author structure the argument? Can you "deconstruct" the flow of the argument to see whether or where it breaks down logically (e.g., in establishing cause-effect relationships)?

- In what ways does this book or article contribute to our understanding of the problem under study, and in what ways is it useful for practice? What are the strengths and limitations?

- How does this book or article relate to the specific thesis or question I am developing?

Text written by Dena Taylor, Health Sciences Writing Centre, University of Toronto

http://www.writing.utoronto.ca/advice/specific-types-of-writing/literature-review

- << Previous: Annotated Bibliography

- Next: Step 5: Cite Sources >>

- Last Updated: Jun 13, 2024 4:27 PM

- URL: https://libguides.uta.edu/researchprocess

University of Texas Arlington Libraries 702 Planetarium Place · Arlington, TX 76019 · 817-272-3000

- Internet Privacy

- Accessibility

- Problems with a guide? Contact Us.

Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

A literature review is a critical analysis and synthesis of existing research on a particular topic. It provides an overview of the current state of knowledge, identifies gaps, and highlights key findings in the literature. 1 The purpose of a literature review is to situate your own research within the context of existing scholarship, demonstrating your understanding of the topic and showing how your work contributes to the ongoing conversation in the field. Learning how to write a literature review is a critical tool for successful research. Your ability to summarize and synthesize prior research pertaining to a certain topic demonstrates your grasp on the topic of study, and assists in the learning process.

Table of Contents

- What is the purpose of literature review?

- a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

- b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

- c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

- d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

How to write a good literature review

- Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Select Databases for Searches:

- Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Review the Literature:

- Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

- Frequently asked questions

What is a literature review?

A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the existing literature, establishes the context for their own research, and contributes to scholarly conversations on the topic. One of the purposes of a literature review is also to help researchers avoid duplicating previous work and ensure that their research is informed by and builds upon the existing body of knowledge.

What is the purpose of literature review?

A literature review serves several important purposes within academic and research contexts. Here are some key objectives and functions of a literature review: 2

1. Contextualizing the Research Problem: The literature review provides a background and context for the research problem under investigation. It helps to situate the study within the existing body of knowledge.

2. Identifying Gaps in Knowledge: By identifying gaps, contradictions, or areas requiring further research, the researcher can shape the research question and justify the significance of the study. This is crucial for ensuring that the new research contributes something novel to the field.

Find academic papers related to your research topic faster. Try Research on Paperpal

3. Understanding Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks: Literature reviews help researchers gain an understanding of the theoretical and conceptual frameworks used in previous studies. This aids in the development of a theoretical framework for the current research.

4. Providing Methodological Insights: Another purpose of literature reviews is that it allows researchers to learn about the methodologies employed in previous studies. This can help in choosing appropriate research methods for the current study and avoiding pitfalls that others may have encountered.

5. Establishing Credibility: A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with existing scholarship, establishing their credibility and expertise in the field. It also helps in building a solid foundation for the new research.

6. Informing Hypotheses or Research Questions: The literature review guides the formulation of hypotheses or research questions by highlighting relevant findings and areas of uncertainty in existing literature.

Literature review example

Let’s delve deeper with a literature review example: Let’s say your literature review is about the impact of climate change on biodiversity. You might format your literature review into sections such as the effects of climate change on habitat loss and species extinction, phenological changes, and marine biodiversity. Each section would then summarize and analyze relevant studies in those areas, highlighting key findings and identifying gaps in the research. The review would conclude by emphasizing the need for further research on specific aspects of the relationship between climate change and biodiversity. The following literature review template provides a glimpse into the recommended literature review structure and content, demonstrating how research findings are organized around specific themes within a broader topic.

Literature Review on Climate Change Impacts on Biodiversity:

Climate change is a global phenomenon with far-reaching consequences, including significant impacts on biodiversity. This literature review synthesizes key findings from various studies:

a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

Climate change-induced alterations in temperature and precipitation patterns contribute to habitat loss, affecting numerous species (Thomas et al., 2004). The review discusses how these changes increase the risk of extinction, particularly for species with specific habitat requirements.

b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

Observations of range shifts and changes in the timing of biological events (phenology) are documented in response to changing climatic conditions (Parmesan & Yohe, 2003). These shifts affect ecosystems and may lead to mismatches between species and their resources.

c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

The review explores the impact of climate change on marine biodiversity, emphasizing ocean acidification’s threat to coral reefs (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007). Changes in pH levels negatively affect coral calcification, disrupting the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

Recognizing the urgency of the situation, the literature review discusses various adaptive strategies adopted by species and conservation efforts aimed at mitigating the impacts of climate change on biodiversity (Hannah et al., 2007). It emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary approaches for effective conservation planning.

Strengthen your literature review with factual insights. Try Research on Paperpal for free!

Writing a literature review involves summarizing and synthesizing existing research on a particular topic. A good literature review format should include the following elements.

Introduction: The introduction sets the stage for your literature review, providing context and introducing the main focus of your review.

- Opening Statement: Begin with a general statement about the broader topic and its significance in the field.

- Scope and Purpose: Clearly define the scope of your literature review. Explain the specific research question or objective you aim to address.

- Organizational Framework: Briefly outline the structure of your literature review, indicating how you will categorize and discuss the existing research.

- Significance of the Study: Highlight why your literature review is important and how it contributes to the understanding of the chosen topic.

- Thesis Statement: Conclude the introduction with a concise thesis statement that outlines the main argument or perspective you will develop in the body of the literature review.

Body: The body of the literature review is where you provide a comprehensive analysis of existing literature, grouping studies based on themes, methodologies, or other relevant criteria.

- Organize by Theme or Concept: Group studies that share common themes, concepts, or methodologies. Discuss each theme or concept in detail, summarizing key findings and identifying gaps or areas of disagreement.

- Critical Analysis: Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each study. Discuss the methodologies used, the quality of evidence, and the overall contribution of each work to the understanding of the topic.

- Synthesis of Findings: Synthesize the information from different studies to highlight trends, patterns, or areas of consensus in the literature.

- Identification of Gaps: Discuss any gaps or limitations in the existing research and explain how your review contributes to filling these gaps.

- Transition between Sections: Provide smooth transitions between different themes or concepts to maintain the flow of your literature review.

Write and Cite as you go with Paperpal Research. Start now for free.

Conclusion: The conclusion of your literature review should summarize the main findings, highlight the contributions of the review, and suggest avenues for future research.

- Summary of Key Findings: Recap the main findings from the literature and restate how they contribute to your research question or objective.

- Contributions to the Field: Discuss the overall contribution of your literature review to the existing knowledge in the field.

- Implications and Applications: Explore the practical implications of the findings and suggest how they might impact future research or practice.

- Recommendations for Future Research: Identify areas that require further investigation and propose potential directions for future research in the field.

- Final Thoughts: Conclude with a final reflection on the importance of your literature review and its relevance to the broader academic community.

Conducting a literature review

Conducting a literature review is an essential step in research that involves reviewing and analyzing existing literature on a specific topic. It’s important to know how to do a literature review effectively, so here are the steps to follow: 1

Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Select a topic that is relevant to your field of study.

- Clearly define your research question or objective. Determine what specific aspect of the topic do you want to explore?

Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Determine the timeframe for your literature review. Are you focusing on recent developments, or do you want a historical overview?

- Consider the geographical scope. Is your review global, or are you focusing on a specific region?

- Define the inclusion and exclusion criteria. What types of sources will you include? Are there specific types of studies or publications you will exclude?

Select Databases for Searches:

- Identify relevant databases for your field. Examples include PubMed, IEEE Xplore, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

- Consider searching in library catalogs, institutional repositories, and specialized databases related to your topic.

Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Develop a systematic search strategy using keywords, Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT), and other search techniques.

- Record and document your search strategy for transparency and replicability.

- Keep track of the articles, including publication details, abstracts, and links. Use citation management tools like EndNote, Zotero, or Mendeley to organize your references.

Review the Literature:

- Evaluate the relevance and quality of each source. Consider the methodology, sample size, and results of studies.

- Organize the literature by themes or key concepts. Identify patterns, trends, and gaps in the existing research.

- Summarize key findings and arguments from each source. Compare and contrast different perspectives.

- Identify areas where there is a consensus in the literature and where there are conflicting opinions.

- Provide critical analysis and synthesis of the literature. What are the strengths and weaknesses of existing research?

Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- Literature review outline should be based on themes, chronological order, or methodological approaches.

- Write a clear and coherent narrative that synthesizes the information gathered.

- Use proper citations for each source and ensure consistency in your citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.).

- Conclude your literature review by summarizing key findings, identifying gaps, and suggesting areas for future research.

Whether you’re exploring a new research field or finding new angles to develop an existing topic, sifting through hundreds of papers can take more time than you have to spare. But what if you could find science-backed insights with verified citations in seconds? That’s the power of Paperpal’s new Research feature!

How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

Paperpal, an AI writing assistant, integrates powerful academic search capabilities within its writing platform. With the Research feature, you get 100% factual insights, with citations backed by 250M+ verified research articles, directly within your writing interface with the option to save relevant references in your Citation Library. By eliminating the need to switch tabs to find answers to all your research questions, Paperpal saves time and helps you stay focused on your writing.

Here’s how to use the Research feature: