Cuneiform is a system of writing first developed by the ancient Sumerians of Mesopotamia c. 3500 BCE. It is considered the most significant among the many cultural contributions of the Sumerians and the greatest among those of the Sumerian city of Uruk , which advanced the writing of cuneiform c. 3200 BCE and allowed for the creation of literature .

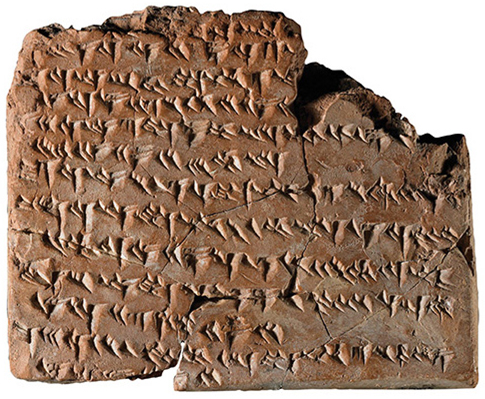

The name comes from the Latin word cuneus for wedge owing to the wedge-shaped style of writing. In cuneiform, a carefully cut writing implement known as a stylus is pressed into soft clay to produce wedge-like imprints that represent word-signs (pictographs) and, later, phonograms or word-concepts (closer to a modern-day understanding of a word). All of the great Mesopotamian civilizations used cuneiform until it was abandoned in favour of the alphabetic script at some point after 100 BCE, including:

When the ancient cuneiform tablets of Mesopotamia were discovered and deciphered in the late 19th century, they would literally transform human understanding of history. Prior to their discovery, the Bible was considered the oldest and most authoritative book in the world and nothing was known of the ancient Sumerian civilization .

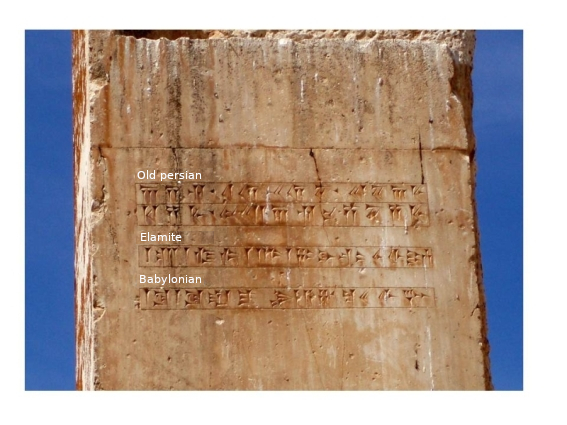

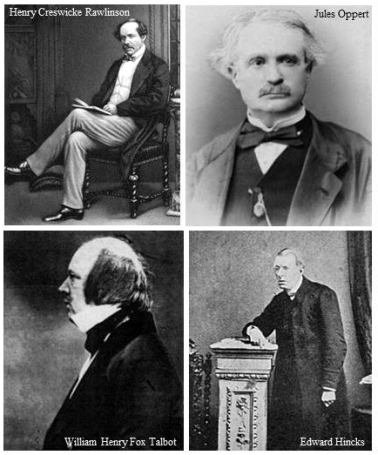

The German philologist Georg Friedrich Grotefend (l. 1775-1853) first deciphered cuneiform prior to 1823, and his work was furthered by Henry Creswicke Rawlinson (l. 1810-1895), who deciphered the Behistun Inscription in 1837, as well as the works of Reverend Edward Hincks (l. 1792-1866) and Jules Oppert (l. 1825-1905). The brilliant scholar and translator George Smith (l. 1840-1876), however, contributed significantly to the understanding of cuneiform with his translation of The Epic of Gilgamesh in 1872. This translation allowed other cuneiform tablets to be interpreted more accurately which overturned the traditional understanding of the biblical version of history of the time and made room for scholarly, objective explorations of the history of the Near East to move forward.

Early Cuneiform

The earliest cuneiform tablets, known as proto-cuneiform, were pictorial, as the subjects they addressed were more concrete and visible (a king, a battle , a flood) and were developed in response to the need for long-distance communication in trade . Sophisticated compositions were unnecessary since all that was required was an understanding of the type and quantity of goods shipped, their price, and the name and location of the seller. Scholar Jeremy Black comments on early cuneiform:

For centuries after the first appearance of writing in southern Iraq in the late fourth millennium BCE, it served an exclusively administrative function. Cuneiform was a mnemonic device designed to aid accountants and bureaucrats, rather than a vehicle for high art. (xlix)

These early pictographs came to be replaced by phonograms (symbols representing sounds) in the city of Uruk by c. 3200 BCE. Cuneiform had developed in complexity by the time of the Early Dynastic Period (2900-2334 BCE) as, once the craft of writing was understood, people found more concepts they wanted to express and preserve for the future. Once writing was discovered, the ancient Sumerians sought to record virtually all of the human experience.

Part of that experience naturally touched on the origin of humanity, which then suggested the origin of all aspects of the human experience. The goddess Nisaba , formerly an agricultural deity, now became the goddess of writing and accounts – even the divine scribe of the gods – in response to the development of the written word. As the subject matter became more intangible (the will of the gods, creation, the afterlife, the quest for immortality), the script became more complex so that, before 3000 BCE, it needed streamlining.

The representations on tablets were simplified, and the strokes of the stylus conveyed word-concepts (honor) rather than word-signs (an honorable man). The written language was further refined through the rebus, which isolated the phonetic value of a certain sign so as to express grammatical relationships and syntax to determine the meaning. In clarifying this, the scholar Ira Spar writes:

This new way of interpreting signs is called the rebus principle. Only a few examples of its use exist in the earliest stages of cuneiform from between 3200 and 3000 B.C. The consistent use of this type of phonetic writing only becomes apparent after 2600 B.C. It constitutes the beginning of a true writing system characterized by a complex combination of word-signs and phonograms—signs for vowels and syllables—that allowed the scribe to express ideas. By the middle of the Third Millennium B.C., cuneiform primarily written on clay tablets was used for a vast array of economic, religious, political, literary, and scholarly documents. (1)

Development of Cuneiform

One no longer had to struggle with the meaning of a pictograph; one now read a word-concept, which more clearly conveyed the meaning of the writer. The number of characters used in writing was also reduced from over 1,000 to 600 in order to simplify and clarify the written word. The best example of this is given by scholar Paul Kriwaczek who notes that in the time of proto-cuneiform:

All that had been devised thus far was a technique for noting down things, items and objects, not a writing system. A record of 'Two Sheep Temple God Inanna ' tells us nothing about whether the sheep are being delivered to, or received from, the temple, whether they are carcasses, beasts on the hoof, or anything else about them. (63)

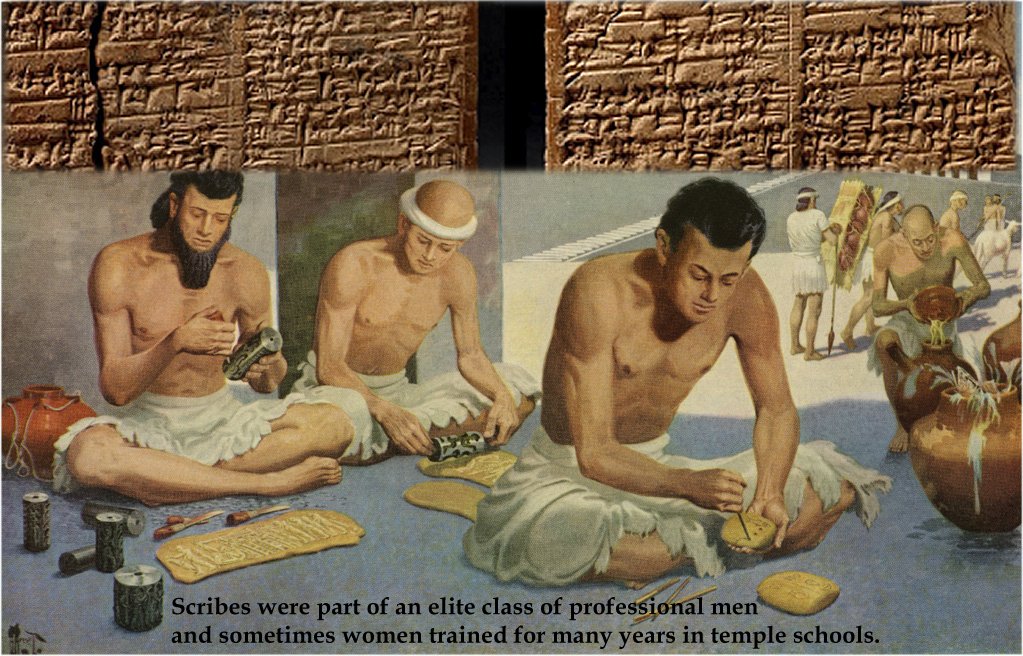

Cuneiform developed to the point where it could be made clear, to use Kriwaczek's example, whether the sheep were coming from or going to the temple, for what purpose, and whether they were living or dead. During the Early Dynastic Period, scribal schools were established to preserve, teach, and further develop the craft of writing. These schools were known as edubba ("House of Tablets") and were initially established and operated out of private homes. The teacher (supervisor) made the rules for each individual edubba at first, and these rules were strictly enforced. The edubba later developed and spread throughout Sumer and, it seems, operated out of buildings expressly designated for the purpose of education.

Boys of the upper class (and sometimes girls) would enter the edubba around the age of eight and continue their studies for the next twelve years. The curriculum progressed from the simplest act of manipulating a moist clay tablet and stylus to forming words and then sentences. The act of writing in cuneiform was not as simple as just holding a piece of clay and making impressions in it. One had to constantly turn the tablet as one was writing to make the marks correctly.

Students were first shown how to simply make the vertical, horizontal, and oblique wedge marks clearly, and they practiced this exercise until they had mastered how to do it properly to the correct depth and dimension. Once the skill of manipulating both clay tablet and stylus was mastered, students moved on to learn characters that conveyed meaning and then produce sentences. While students were mastering the craft of writing, they were also instructed in mathematics, accounting, history, religion , and the values of their culture . Scholar Samuel Noah Kramer comments:

In order to satisfy this pedagogical need, the Sumerian scribal teachers devised a system of instruction which consisted primarily in linguistic classification – that is, they classified the Sumerian language into groups of related words and phrases and had the students memorize and copy them until they could reproduce them with ease. In the third millennium BCE, these "textbooks" became increasingly more complete, and gradually grew to be more or less stereotyped and standard for all the schools of Sumer. Among them we find long lists of names of trees and reeds: of all sorts of animals, including insects and birds; of countries, cities , and villages; of stones and minerals. These compilations reveal a considerable acquaintance with what might be termed botanical, zoological, geographical, and mineralogical lore – a fact that is only now beginning to be realized by historians of science . ( History , 6)

Students progressed through their stages of education until they reached the level of the Tetrad (compositions of four) and Decad (compositions of ten) which were studied, memorized, and copied repeatedly. The Tetrad was comprised of simple texts, including the Hymn to Nisaba , while the Decad's texts were more complex in both composition and meaning. After the Decad, a student was expected to master even more complex compositions, such as A Supervisor's Advice to a Young Scribe or The Curse of Agade prior to graduation. Compositions were usually concluded with praise to Nisaba in gratitude for her inspiration and encouragement.

By this progression, literature not only developed but was made available for comment and criticism in written form while, in the process, the history of Mesopotamian civilization and culture, in every era, was preserved. By the time of the priestess-poet Enheduanna (l. 2285-2250 BCE), who wrote her famous hymns to Inanna in the Sumerian city of Ur , cuneiform was sophisticated enough to convey emotional states such as love and adoration, betrayal and fear, longing and hope, as well as the precise reasons why the writer might be experiencing such states.

Cuneiform could also express the human fear of death and hope of a life beyond, the tales of the creation of the world, the relationship between humans and their gods, and the devastation of existential despair when it seemed as though the gods had disappointed one's hopes and expectations. Cuneiform writing expressed in tangible form the whole of the human experience for the first time in history. Cuneiform can be understood, in fact, as the beginning of human historical documentation.

Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

Cuneiform Decipherment & Impact

The great literary works of Mesopotamia such as the Atrahasis , The Descent of Inanna , The Myth of Etana , the Enuma Elish, and the famous Epic of Gilgamesh were all written in cuneiform and were completely unknown until the mid-19th century when men like George Smith, the Reverend Edward Hincks, Jules Oppert, and Rawlinson deciphered the language and translated it. Kramer writes:

The Sumerian literary documents range in size from large twelve- column tablets inscribed with hundreds of compactly written lines of text to tiny fragments run into the hundreds and vary in length from hymns of less than fifty lines to myths close to a thousand lines. As literary products, the Sumerian belles-lettres rank high among the aesthetic creations of civilized man. They compare not too unfavorably with the ancient Greek and Hebrew masterpieces and, like them, mirror the spiritual and intellectual life of an ancient culture which would otherwise have remained largely unknown. Their significance for a proper appraisal of the cultural and spiritual development of the entire ancient Near East can hardly be overestimated. ( Sumerians , 166)

Even so, as noted, these works were entirely unknown until the mid-19th century. Rawlinson's translations of Mesopotamian texts were first presented to the Royal Asiatic Society of London in 1837 and again in 1839. In 1846, he worked with the archaeologist Austin Henry Layard in his excavation of Nineveh and was responsible for the earliest translations from the library of Ashurbanipal discovered at that site.

Edward Hincks focused on Persian cuneiform, establishing its patterns and identifying vowels among his other contributions. Jules Oppert identified cuneiform's origins and established the grammar of Assyrian cuneiform. George Smith was responsible for deciphering T he Epic of Gilgamesh and, in 1872, famously, the Mesopotamian version of the Flood Story, which until then was thought to be original to the biblical Book of Genesis.

Many biblical texts were thought to be original until cuneiform was deciphered. The Fall of Man and the Great Flood were understood as literal events in human history dictated by God to the author (or authors) of Genesis but were now recognized as Mesopotamian myths which Hebrew scribes had embellished on from The Myth of Etana and the Atrahasis . The biblical story of the Garden of Eden could now be understood as a myth derived from the Enuma Elish and other Mesopotamian works. The Book of Job , far from being an actual historical account of an individual's unjust suffering, could now be recognized as a literary motif belonging to a Mesopotamian tradition following the discovery of the earlier Ludlul-Bel-Nemeqi text which relates a similar story.

The concept of a dying and reviving god who goes down into the underworld and then returns to life, presented as a novel concept in the gospels of the New Testament, was now understood as an ancient paradigm first expressed in Mesopotamian literature in the poem The Descent of Inanna . The very model of many of the narratives of the Bible, including the gospels , could now be read in light of the discovery of Mesopotamian naru literature which took a figure from history and embellished upon his achievements in order to relay an important moral and cultural message.

Prior to this time, as noted, the Bible was considered the oldest book in the world, and the Song of Solomon was thought to be the oldest love poem, but all of that changed with the discovery and decipherment of cuneiform. The oldest love poem in the world is now recognized as The Love Song of Shu-Sin dated to 2000 BCE, long before The Song of Solomon was written. These advances in understanding were all made by the 19th-century archaeologists and scholars sent to Mesopotamia to substantiate biblical stories through physical evidence, but, in fact, what they discovered was precisely the opposite of what they had been sent to find.

Along with other Assyriologists (among them, T. G. Pinches and Edwin Norris), Rawlinson spearheaded the development of Mesopotamian language studies, and his Cuneiform Inscriptions of Ancient Babylon and Assyria , along with his other works, became the standard reference on the subject following their publication in the 1860s and remain respected scholarly works into the present day.

George Smith, regarded as an intellect of the first rank, died on a field expedition to Nineveh in 1876 at the age of 36. Smith, a self-taught translator of cuneiform, made his first contributions to deciphering the ancient writing in his early twenties, and his death at such a young age has long been regarded as a significant loss to the advancement in translations of cuneiform in the 19th century.

The literature of Mesopotamia significantly informed written works which came after. Mesopotamian literary motifs can be detected in the works of Egyptian , Hebrew, Greek, and Roman works and still resonate in the present day through the biblical narratives which they inform. When George Smith deciphered cuneiform he dramatically changed the way human beings would understand their history.

The accepted version of the creation of the world, original sin, and many of the other precepts by which people had been living their lives were all challenged by the revelation of Mesopotamian – largely Sumerian – literature. Since the discovery and decipherment of cuneiform, the history of civilization and human progress has been radically revised from the understanding of only 200 years ago, and further revisions are expected as more cuneiform tablets are discovered and translated for the modern age.

Subscribe to topic Related Content Books Cite This Work License

Bibliography

- Bertman, S. Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Black, J., et al. The Literature of Ancient Sumer. Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Durant, W. Our Oriental Heritage. Simon & Schuster, 2010.

- Kramer, S. N. History Begins at Sumer. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1988.

- Kramer, S. N. The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. University of Chicago Press, 1971.

- Kriwaczek, P. Babylon: Mesopotamia and the Birth of Civilization. Thomas Dunne Books, 2012.

- Leick, G. The A to Z of Mesopotamia. Scarecrow Press, 2010.

- The Origins of Writing by Ira Spar Accessed 9 Nov 2022.

About the Author

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this definition into another language!

Questions & Answers

Is cuneiform the first written language, what does cuneiform mean, when was cuneiform first deciphered, why is cuneiform important, related content.

Hymn to Nisaba

Free for the World, Supported by You

World History Encyclopedia is a non-profit organization. For only $5 per month you can become a member and support our mission to engage people with cultural heritage and to improve history education worldwide.

Recommended Books

| , published by University of Pennsylvania Press (1988) |

| , published by Oxford University Press (2006) |

| , published by Scarecrow Press (2010) |

| , published by Oxford University Press (2005) |

| , published by University of Chicago Press (1971) |

External Links

Cite this work.

Mark, J. J. (2022, November 17). Cuneiform . World History Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/cuneiform/

Chicago Style

Mark, Joshua J.. " Cuneiform ." World History Encyclopedia . Last modified November 17, 2022. https://www.worldhistory.org/cuneiform/.

Mark, Joshua J.. " Cuneiform ." World History Encyclopedia . World History Encyclopedia, 17 Nov 2022. Web. 29 Jun 2024.

License & Copyright

Submitted by Joshua J. Mark , published on 17 November 2022. The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike . This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. When republishing on the web a hyperlink back to the original content source URL must be included. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.

World History Edu

- Ancient Mesopotamia

Cuneiform Writing: History, Meaning, Symbols, and Facts

by World History Edu · May 26, 2021

Cuneiform – the world’s oldest writing

Cuneiform was a writing system invented by the ancient Sumer people of the Mesopotamian region (ancient Middle East). According to historians, this form of writing emerged about 5,000 years ago, making it the world’s first-known written language. For over 3,000 years, the cuneiform script remained the dominant written language in the known world, before it was replaced by alphabetical scripts.

In the article below, World History Edu takes an in-depth look into the history, meaning, and significance of cuneiform writing.

Origin story of Cuneiform writing

Many consider the origin of writing as the origin of Sumerian cuneiform due to how old the cuneiform writing system is.

The ancient Sumerians of southern Mesopotamia (located in what is now southern Iraq) are widely held as the civilization that invented cuneiform writing around 3500 BCE. The writing form would then span from the early Bronze Age to the Common Era, around 75 CE.

Cuneiform was used by all the great civilizations that emerged from ancient Mesopotamia, including the Akkadians, the Babylonians, the Assyrians, the Elamites, Hatti, and the Persians. For centuries, those inscriptions on clay tablets were used by city administrators and priests of temples to keep record of ration allocation and the grain, sheep and other forms of goods that were received.

Cuneiform writing was also used to take records of activities pertaining to business and trade. It was also the primary writing language used by story writers, poets, and letter writers.

Beginning around 100 BCE, cuneiform script stated getting replaced by alphabetic script, primarily the Aramaean alphabet.

Due to the wedge-shaped stylus that was used in writing, the cuneiform system is sometimes known as the ancient wedge-shaped impressions of the Mesopotamians. The origin of the word has been stated to come from the Latin word cuneus which means ‘wedge’. The Latin word most likely stemmed from the cuneiform writing style in the first place.

The cuneiform writing was generally made with a writing implement/tool – i.e. a reed stylus – which was then pressed into a soft clay to give wedge-like impressions

Cuneiform tablets and how they were made

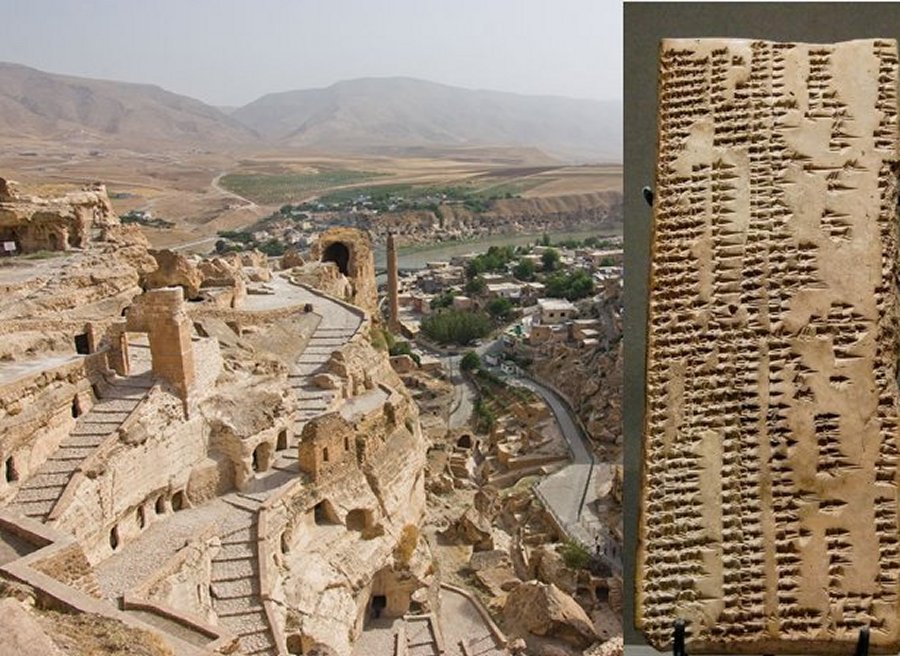

Based on archaeological findings, historians reason that Sumerian city of Uruk was the birthplace of the cuneiform writing system. It began with proto-cuneiform, a pictorial writing system that historians believe was used on many of the earliest cuneiform tablets.

After a wedge-tipped stylus is pushed into wet clay to make the writing, the tablet is then placed in kilns in order to for it to be baked hard. The writers that did not want to leave a permanent record used moist clay, allowing them to easily alter the record at later date.

Archaeologists opine that many of the discovered cuneiform tablets that we see today were likely preserved by chance after invading armies burnt down buildings that contained a relatively moist clay tablet. The fire acted like an oven, baking those clay tablets into what we see today.

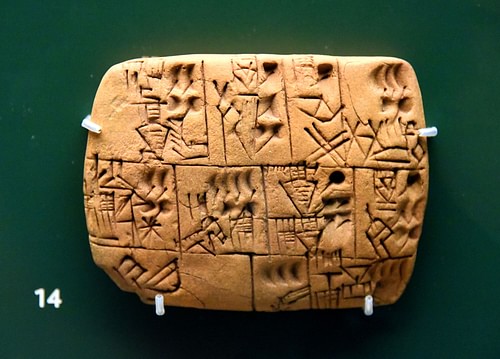

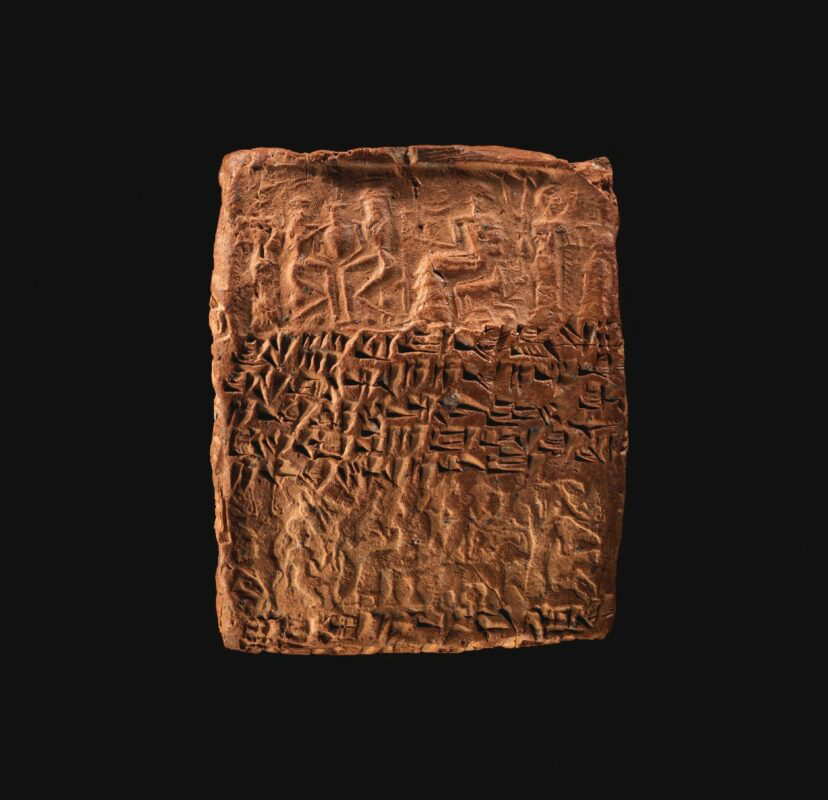

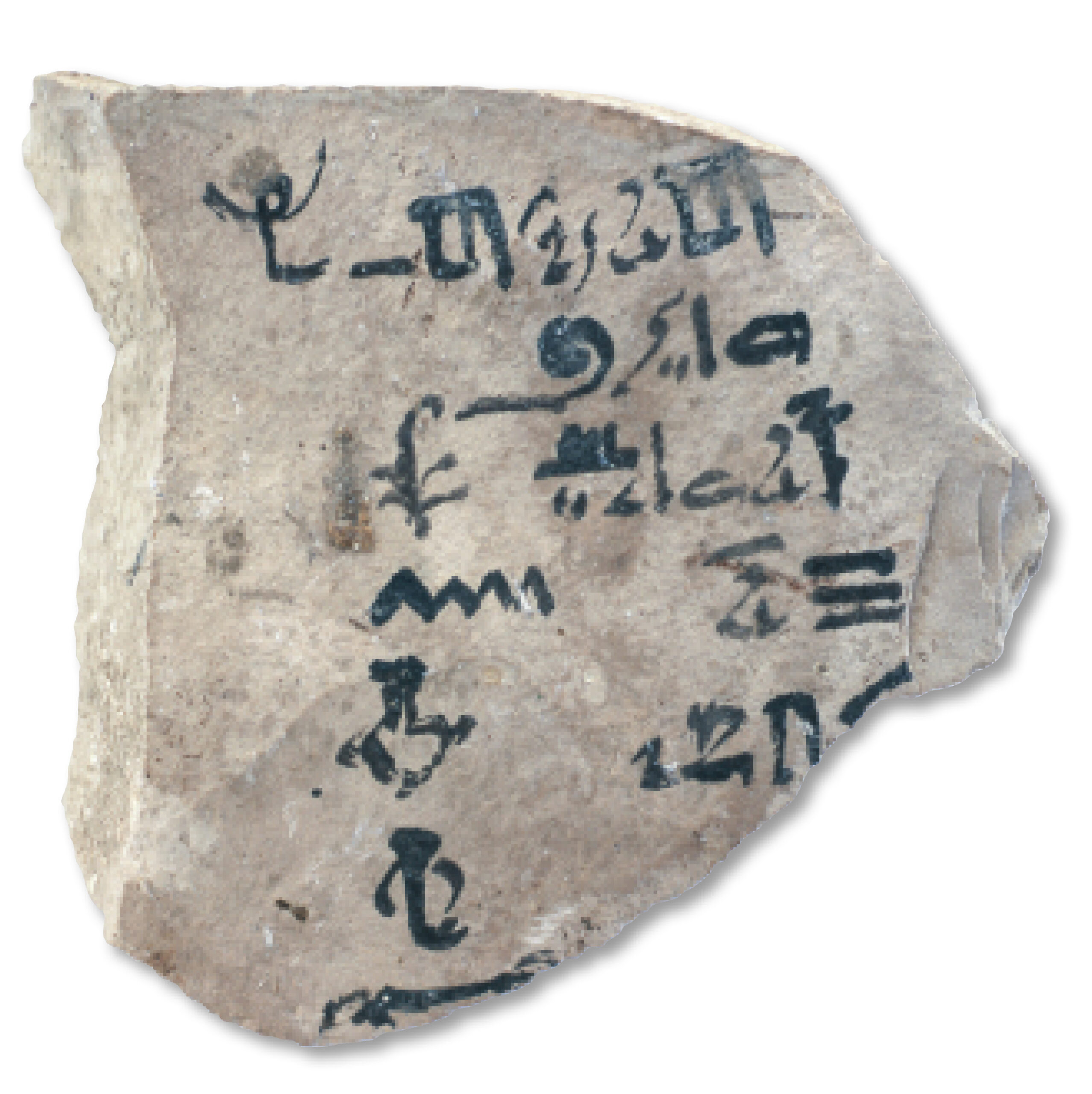

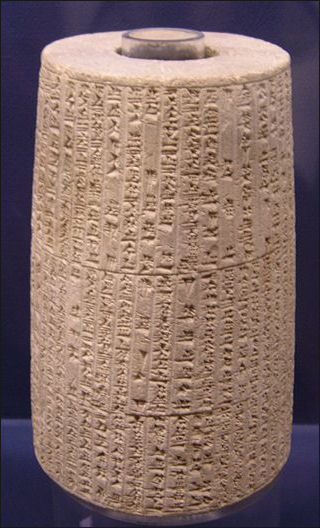

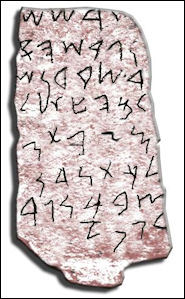

Cuneiform – The Kish tablet, a limestone tablet from Kish with pictographic, early cuneiform, writing, 3500 BC. Possibly the earliest known example of writing. Ashmolean Museum.

Cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphs

Cuneiform, along with the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, constitutes the oldest known writing system. However, the Egyptian hieroglyphs are believed to have emerged a few centuries after the birth of the Sumerian proto-cuneiform. Some historians posit that the hieroglyphs may have taken some inspiration from the Mesopotamian cuneiform writing.

Ancient Mesopotamian rulers had the habit of inscribing cuneiform script into commemorative stelae, detailing how mighty a ruler they were, or in some cases, how divine their rule was.

- 12 Most Famous Ancient Mesopotamian Gods and Goddesses

- 10 Most Famous Kings of Ancient Mesopotamia

- 9 Greatest Ancient Mesopotamian Cities

Evolution of Cuneiform writing

The pre-cuneiform writing was not advanced enough to convey more than concrete and visible subjects. It relied solely on pictographic technique. This was around the late 4th millennium BCE. Those pictographic techniques were in turn influenced by near eastern token system, which dates to the 9 th millennium BCE. This type of cuneiform writing spanned from 3400 BCE to 3100 BCE.

With the passage of time, the subjects on the cuneiform tablets became more complex and difficult (i.e. from a modern scholar’s perspective) to interpret. Those changes started with the proto-cuneiform writing of around 3100 BCE, when slight syllabic elements began to appear in the writing. On the back of the introduction of a modified wedge-tipped stylus around 2500 BCE, early dynastic cuneiform writing became relatively easier and quicker to produce.

As signs in the cuneiform system changed from pictograms to syllabograms, the ancient Mesopotamians could convey subjects like immortality and the commands of the gods. This was starkly different from the previous versions that could only note down things and objects. Say there was a bird and the god Marduk pictorially used in the system, readers would struggle to decipher what those objects tell in relation to each other. Was the bird an embodiment of Marduk? Or was the bird being sacrificed to Marduk?

The early dynastic cuneiform system of around the late 3 rd millennium BCE was a bit more refined and could communicate grammatical relationships and syntax. It could easily convey ideas as it combined word-signs and phonograms. This allowed for the writing system to be used communicating ideas in religion, economics, politics and literature.

Also, the characters were reduced from more than 1000 to 600 in order to allow for more clarity. By the 23 rd Century BCE, cuneiform had reached a point where emotional concepts like loyalty, trust, love, fear, hate, hope, and anger could be communicated. This explains how Enheduanna , the famous priestess of Inanna, in Ur (a Sumerian city) could write her poems and hymns in praise of the Mesopotamian goddess Inanna.

Proto-cuneiform tablet, Jemdet Nasr period, c. 3100–2900 BCE

When were cuneiform inscriptions deciphered?

For several centuries, Common Era scholars worked day and night trying to decipher cuneiform writings. For example Arabo-Persian historians of the Islamic Golden Age (8 th century to 14 th century CE) tried their hardest to unravel the mysteries of cuneiform writings littered across Mesopotamia region. All of those attempts ended in disappointment.

Many Middle Ages European scholars – like the Venetian explorer Giosafat Barbaro and theology professor Antonio de Gouvea – share with the rest of Europe about how they had encountered very strange writing in a number of ancient ruins in the Middle East, particularly in Persepolis (present-day Iran). In the 17 th century, English traveler and historian Sir Thomas Herbert rightly stated how those strange characters were not Egyptian hieroglyphics. Sir Thomas noted that they were words and syllables instead of letters.

In the 18 th century, scholars such as German cartographer and explorer Carsten Niebuhr and French Indologist Anquietil-Duperron paved the way for the likes of George Smith, Edward Hincks, Jules Oppert (1825-1905), and Henry Creswicke Rawlinson (1810-1895) to properly decipher the various ancient Mesopotamian cuneiforms. For example Rawlinson finished deciphering Old Persian cuneiform in the 1830s. Hincks contributed tremendously in analyzing the patterns and vowels found in Persian cuneiform.

Borrowing on the techniques used to decipher Old Persian cuneiform, scholars were able to decipher Akkadian and then Sumerian cuneiforms.

It is worth mentioning that George Smith played an instrumental role in translating those cuneiforms into English. The acclaimed historian and archaeologist died at the age of 36 while deeply engrossed in his work during the excavation of Nineveh (what is now Kuyunjik) in 1876. Smith is praised for having taught himself how to translate cuneiform.

Cuneiform writing | English archaeologist George Smith is most known for translating the ancient Mesopotamian epic, The Epic of Gilgamesh

Most famous cuneiform literature

Since the mid-19th century CE, archaeologists have discovered many cuneiform tablets that contain Mesopotamian literature and epics like the Atrahasis , The Myth of Etana , The Enuma Elish and The Epic of Gilgamesh. The Library of Ashurbanipal, which was discovered by English traveler and archaeologist Sir Austen Henry Layard and Hormuzd Rassam in 1849, had a collection of more than 30,000 clay tablets, mostly written in Akkadian language. The library, which was built by King Ashurbanipal of the Assyrian Empire, contained the famous Epic of Gilgamesh .

The 1933 discovery of a collection of close to 20,000 cuneiform tablets in Persepolis, Iran was welcomed with joy by the archeology community.

The Epic of Gilgamesh

Critically acclaimed Assyriologist George Smith (1840-1876) is credited with translating The Epic of Gilgamesh in 1872 CE. It turned out that the account of the Great Flood was not original to the Book of Genesis in the Bible. Smith’s numerous trips and excavations of the Library of Ashurbanipal in Nineveh ( Kuyunjik in present-day Iraq) unearthed a number of cuneiform clay tablets relating to ancient Mesopotamian creation story. Those discoveries and many other more opened the flood gates for other cuneiform tablets to be translated. It enabled historians objectively reinterpret the history of those ancient civilizations.

Significance

Cuneiform writing system was significant in the sense that it helped many Mesopotamian civilizations convey a great chunk of knowledge and history. It ranks as the most important contribution of the Sumerian civilization, influencing the culture, scholarship and religion of ancient Egyptians, ancient Greeks and Romans.

After cuneiform tablets were deciphered, historians gained access to a great chunk of human history that was penned in cuneiform. This transformed how historians understood the history of those ancient civilizations.

Cuneiform writing and the Bible

Before the discovery of cuneiform on ancient Mesopotamian clay tablets, it was widely accepted that the Bible, specifically the Song of Solomon, was the oldest book in the world. The Song of Solomon for example was seen as the oldest love poem. With the discovery of cuneiform, that title currently belongs to the ancient Mesopotamian love poem titled The Love Song of Shu-Sin. This particular poem goes all the way back to around 2000 BCE.

The deciphering and translation of cuneiform challenged the Bible’s authority on the creation story and the original sin. It also meant that historians no longer considered the Bible as the oldest known-authoritative book in human history.

Many stories and texts in the Bible that were thought original to the Bible turned out to have been adapted from Mesopotamian stories as shown in the discovered cuneiform tablets. For example, the stories about The Fall of Man and the Great Flood in the biblical Book of Genesis were said to have been given to human beings by God, making them appear as being written by God. Archaeological findings show that many of those stories were adapted from Mesopotamian myths. The Hebrew scholars garnished them to make them fit the narrative of the prevailing religion at the time.

The Garden of Eden story in the Bible and the Book of Job were most likely derived from Mesopotamian myths The Enuma Elish and Ludlul-Bel-Nimeqi respectively. The gospels of the New Testament – i.e. the concept of a deity or superhuman dying and resurrecting – likely came from the Mesopotamian poem The Descent of Inanna.

Cuneiform writing | The invention of writing according to an ancient Mesopotamian poem, Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta (c. 1800 BCE). Kulaba is the name for the ancient Mesopotamian city of Uruk

More facts about cuneiform

- As late as 75 AD, cuneiform writing was still in usage.

- The Sumerian city of Uruk (located east of the Euphrates River in present-day Iraq) holds the title of being the first-known place to have the first recorded writing. The writing was done around the 4 th millennium BCE.

- Famed English orientalist Thomas Hyde (1636-1703) was the first scholar to term the characters “cuneiform”. However, he opined wrongly that the inscriptions were used by the ancient Mesopotamians for decorative purposes.

- More than 500,000 cuneiform tablets have been discovered so far in modern times, many of them are housed in museums across the world. With more than 130,000 cuneiform tablets, the British Museum has the largest collections of cuneiform tablets in the world. Other museums that possess considerable number of cuneiform tablets include the Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin, the Istanbul Archaeology Museums (in Eminonu, Istanbul, Turkey), the Yale Babylonian Collection, Penn Museum in Philadelphia, U.S., and the Louvre in France.

Tags: Cunieform writing Gilgamesh Sumerian civilization Ur Uruk

You may also like...

Ancient Mesopotamia: History and Timeline

June 5, 2019

Hammurabi Code of Laws: Meaning, Summary, Examples, and Significance

April 20, 2020

Ancient Mesopotamia: 9 Greatest Cities

June 4, 2020

- Pingbacks 0

Irrefutable proof that the christian church has been stealing and rebranding information much earlier than previously proven.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Next story Nabopolassar: History, Accomplishments and Facts

- Previous story 12 Major Achievements of Ancient Babylonia

- Popular Posts

- Recent Posts

Why are there two Virginias?

Who were the greatest generals of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars?

Michel Ney: The French Military Commander Described by Napoleon as “the Bravest of the Brave”

The Battle of San Jacinto and why it is considered a defining moment in Texas history

The Compromise of 1850: History & Major Facts

Greatest African Leaders of all Time

Queen Elizabeth II: 10 Major Achievements

Donald Trump’s Educational Background

Donald Trump: 10 Most Significant Achievements

8 Most Important Achievements of John F. Kennedy

Odin in Norse Mythology: Origin Story, Meaning and Symbols

Ragnar Lothbrok – History, Facts & Legendary Achievements

9 Great Achievements of Queen Victoria

12 Most Influential Presidents of the United States

Most Ruthless African Dictators of All Time

Kwame Nkrumah: History, Major Facts & 10 Memorable Achievements

Greek God Hermes: Myths, Powers and Early Portrayals

8 Major Achievements of Rosa Parks

Kamala Harris: 10 Major Achievements

Trail of Tears: Story, Death Count & Facts

10 Most Famous Pharaohs of Egypt

How did Captain James Cook die?

5 Great Accomplishments of Ancient Greece

The Exact Relationship between Elizabeth II and Elizabeth I

How and when was Morse Code Invented?

- Adolf Hitler Alexander the Great American Civil War Ancient Egyptian gods Ancient Egyptian religion Apollo Athena Athens Black history Carthage China Civil Rights Movement Cold War Constantine the Great Constantinople Egypt England France Germany Hera Horus India Isis Julius Caesar Loki Medieval History Military Generals Military History Napoleon Bonaparte Nobel Peace Prize Odin Osiris Ottoman Empire Pan-Africanism Queen Elizabeth I Religion Set (Seth) Soviet Union Thor Timeline Turkey Women’s History World War I World War II Zeus

Cuneiform: The World’s Oldest Writing System

Cuneiform, the world’s first writing system, is a fascinating window into the lives of our ancestors.

Developed over 5,000 years ago in Mesopotamia, cuneiform was used to record everything – including everyday transactions, personal letters, and epic poems, like the Epic of Gilgamesh.

Today, it leaves historians and archaeologists with an invaluable source of information about ancient history, literature, religion, and science.

One might picture a scribe living in ancient Babylon, carefully etching the wedges onto a clay tablet as the sun sets around him.

Understanding cuneiform and its history allows us to unlock not only the thoughts, secrets, and sagas of such a scribe; but those of an entire ancient world.

The Origin of Cuneiform Writing

Cuneiform is the earliest known writing system that we know of today. It was originally developed in ancient Mesopotamia for the Sumerian language around 3500 BC.

While the Sumerians were the earliest known users of cuneiform writing, the earliest written records in ancient Sumer are pictographic tablets from Uruk. This early form could only express the basic ideas of concrete objects.

However, the need to represent proper names would eventually bring about the use of pictographic shapes to evoke in the reader’s mind an underlying sound – phonetic writing.

Few physical examples of proto-cuneiform survive from its earliest period – between 3200 and 3000 BC – but by the middle of the third millennium BC, cuneiform was everywhere, utilized for all things economic, religious, political, literary, and scholarly.

Over time, the cuneiform script evolved and was used for various languages beyond Sumerian, like Akkadian , Hittite, and Elamite.

As far as modern archaeology has uncovered, the latest known use of cuneiform was likely around 75 AD, after which the script is thought to have fallen out of use. It was completely forgotten until its rediscovery and decipherment in more modern times.

Its Discovery and Decipherment

Early attempts at cuneiform decipherment date back to medieval Arabo-Persian historians.

Later in the 15th century, European explorers like Giosafat Barbaro, Antonio de Gouvea, and Pietro Della Valle recorded and publicized the early writing systems, including Old Persian inscriptions.

Later, in 1638, Sir Thomas Herbert from England claimed cuneiform as legible and intelligible, and the linguist Thomas Hyde coined the term “cuneiform” in 1700.

The race to decipher and translate cuneiform inscriptions would quicken throughout the late 1700s and into the 1800s.

Finally, the script was cracked open with the identification of the word “king” and the name of the great Persian king, Darius the Great , by Georg Friedrich Grotefend.

Old Persian cuneiform would be successfully deciphered by linguists, historians, and archaeologists across Europe, followed by the cuneiform scripts in other languages such as Elamite, Babylonian, Akkadian, and Sumerian.

Deciphering cuneiform inscriptions took decades of intense, dedicated work by hundreds of scholars, but in the end, their findings opened an entirely new world to the annals of history.

Clay Tablets and a Written Language

But how did cuneiform work? How did the ancient Mesopotamians write it?

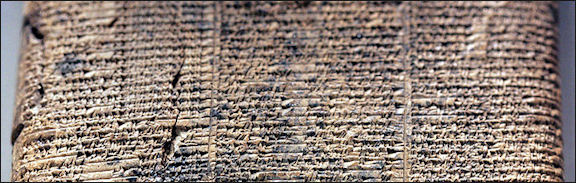

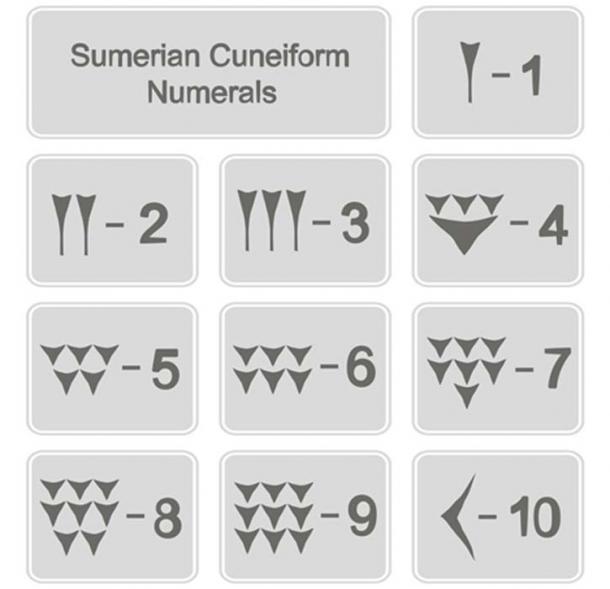

In short, cuneiform writing is logo-syllabic, meaning each of its written symbols – themselves composed of wedges pressed into the soft clay by a reed stylus – is representative of a spoken syllable or of a certain character or word.

Since the Sumerian language was monosyllabic, the cuneiform signs typically represented syllables, resulting in a word-syllabic script.

The writing became increasingly complex as time passed, and the pictographs evolved into conventionalized linear drawings.

The writing system developed in stages, starting with pictographs and abstract signs and progressing to the more well-known wedge-shaped signs.

As cuneiform transitioned from pure words to a partially phonetic script, the ‘rebus principle’ became necessary, where pictographic shapes were used to evoke an underlying sound form rather than the basic notion of the drawn object.

With time, the written script would become quite complex. Still, until the first century AD, written Sumerian continued to be utilized as a scribal language. The spoken language, on the other hand, eventually died out around 2000 BC.

Clay tablets were the most common writing material, and as a result, the marks took on a wedge shape from the slanted edge of a stylus.

About 6,000 of these early cuneiform tablets have been discovered, while hundreds of thousands of later, more developed cuneiform tablets are housed in museums worldwide.

Cuneiform’s Regional Influence

The Sumerian script became a complex system that could express just about any topic of human endeavor, and the written word quickly evolved into the backbone of a growing civilization.

It even played a crucial role in disseminating writing to neighboring regions, such as Egypt, with its Egyptian hieroglyphs and the Indus Valley, where writing appeared not long after on official seals featuring individuals’ names and titles.

Cuneiform was adopted by many of these neighboring Mesopotamian and ancient Near East cultures, each of whom adapted it to their different languages.

For example, Linear A and B, the phonetic scripts of Crete and mainland Greece, were likely influenced in this way.

In many ancient societies, cuneiform was used at many levels, from basic functional knowledge for average citizens to technical use for medicine, math, and business.

It could even be considered a complex skill and art form for scholars and played a significant role in Babylonian scribal education.

Ultimately, cuneiform played a crucial role across the ancient Near East.

Legacy and Importance

Cuneiform is largely regarded as the ancient Sumerian culture’s most important and influential contribution. Its creation spurred the birth of literature, allowing for legendary epics, like the Epic of Gilgamesh, to be recorded for all time.

Moreover, the historical significance of cuneiform lies in its role as a precursor to modern writing. Its ability to record and preserve critical information about ancient societies and civilizations enables us today to understand what life must have been like then.

Cuneiform provides not just a window into the past, but in its time, it represented a new technology, driving civilization and history ever forward.

“Cuneiform.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 1 Jan. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/topic/cuneiform.

F., Walker C B. Reading the Past: Cuneiform. Univ. of California Press, 1988, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/Walker.C.ReadingThePastCuneiform/mode/2up, Accessed 27 Feb. 2023.

Radner, Karen, and Eleanor Robson. “Introduction.” The Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2020, pp. xxvi-xxxii, https://academic.oup.com/edited-volume/27992/chapter/211695261. Accessed 27 Feb. 2023.

Spar, Ira. “The Origins of Writing.” The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1 Jan. 1AD, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/wrtg/hd_wrtg.htm.

Watkins, Lee, and Dean Snyder. “The Digital Hammurabi Project.” Digital Hammurabi Project, The Johns Hopkins University, 2003, https://pages.jh.edu/dighamm/version2/.

Related Posts

Henry Lee Lucas: The Self-Proclaimed Greatest Serial Killer

Why Are the Early Middle Ages Called the Dark Ages?

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

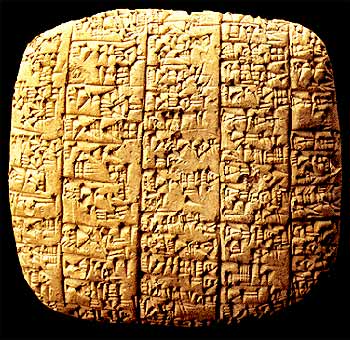

Cuneiform, an introduction

The earliest writing we know of dates back to around 3000 B.C.E. and was probably invented by the Sumerians , living in major cities with centralized economies in what is now southern Iraq. The earliest tablets with written inscriptions represent the work of administrators, perhaps of large temple institutions, recording the allocation of rations or the movement and storage of goods. Temple officials needed to keep records of the grain, sheep, and cattle entering or leaving their stores and farms and it became impossible to rely on memory. So, an alternative method was required and the very earliest texts were pictures of the items scribes needed to record (known as pictographs).

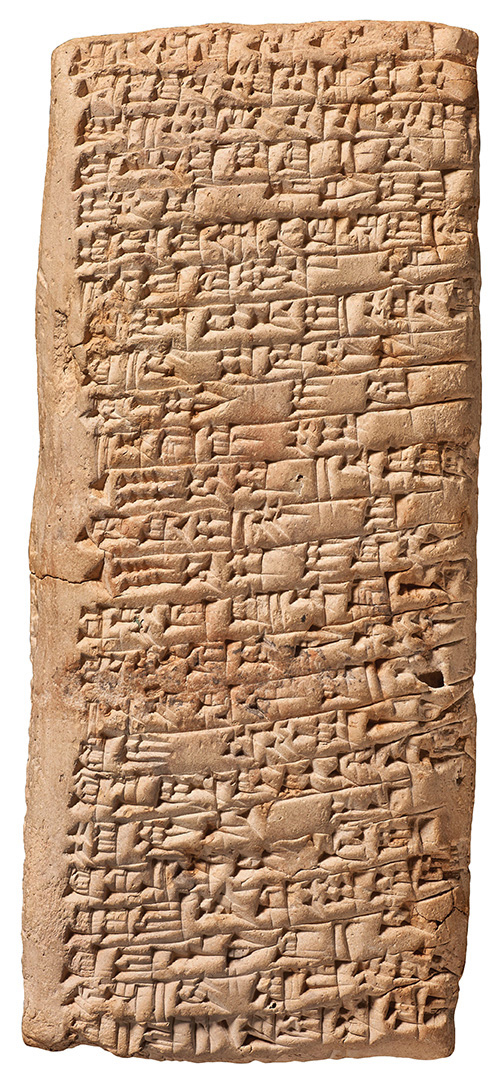

Early writing tablet recording the allocation of beer, 3100–3000 B.C.E, Late Prehistoric period, clay, probably from southern Iraq. (© Trustees of the British Museum ) The symbol for beer, an upright jar with pointed base, appears three times on the tablet. Beer was the most popular drink in Mesopotamia and was issued as rations to workers. Alongside the pictographs are five different shaped impressions, representing numerical symbols. Over time these signs became more abstract and wedge-like, or “cuneiform.” The signs are grouped into boxes and, at this early date, are usually read from top to bottom and right to left. One sign, in the bottom row on the left, shows a bowl tipped towards a schematic human head. This is the sign for “to eat.”

Writing, the recording of a spoken language, emerged from earlier recording systems at the end of the fourth millennium. The first written language in Mesopotamia is called Sumerian. Most of the early tablets come from the site of Uruk , in southern Mesopotamia, and it may have been here that this form of writing was invented.

These texts were drawn on damp clay tablets using a pointed tool . It seems the scribes realized it was quicker and easier to produce representations of such things as animals, rather than naturalistic impressions of them. They began to draw marks in the clay to make up signs, which were standardized so they could be recognized by many people.

From these beginnings, cuneiform signs were put together and developed to represent sounds, so they could be used to record spoken language. Once this was achieved, ideas and concepts could be expressed and communicated in writing.

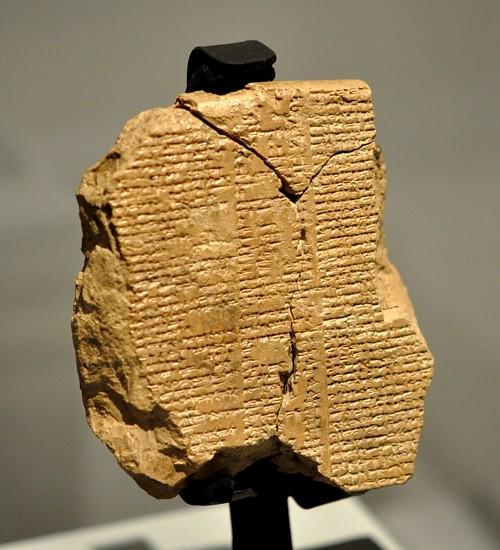

Cuneiform is one of the oldest forms of writing known. It means “wedge-shaped,” because people wrote it using a reed stylus cut to make a wedge-shaped mark on a clay tablet. Letters enclosed in clay envelopes, as well as works of literature, such as the Epic of Gilgamesh have been found. Historical accounts have also come to light, as have huge libraries such as that belonging to the Assyrian king, Ashurbanipal . Cuneiform writing was used to record a variety of information such as temple activities, business, and trade. Cuneiform was also used to write stories, myths, and personal letters. The latest known example of cuneiform is an astronomical text from 75 C.E. During its 3,000-year history, cuneiform was used to write around 15 different languages including Sumerian, Akkadian , Babylonian , Assyrian, Elamite, Hittite , Urartian, and Old Persian .

Cuneiform tablets at the British Museum

The department’s collection of cuneiform tablets is among the most important in the world. It contains approximately 130,000 texts and fragments and is perhaps the largest collection outside of Iraq. The centerpiece of the collection is the Library of Ashurbanipal, comprising many thousands of the most important tablets ever found. The significance of these tablets was immediately realized by the Library’s excavator, Austin Henry Layard, who wrote:

They furnish us with materials for the complete decipherment of the cuneiform character, for restoring the language and history of Assyria, and for inquiring into the customs, sciences, and . . . literature, of its people.

The Library of Ashurbanipal is the oldest surviving royal library in the world. British Museum archaeologists discovered more than 30,000 cuneiform tablets and fragments at his capital, Nineveh (modern Kuyunjik). Alongside historical inscriptions, letters, and administrative and legal texts, were found thousands of divinatory, magical, medical, literary and lexical texts. This treasure-house of learning has held unparalleled importance to the modern study of the ancient Near East ever since the first fragments were excavated in the 1850s.

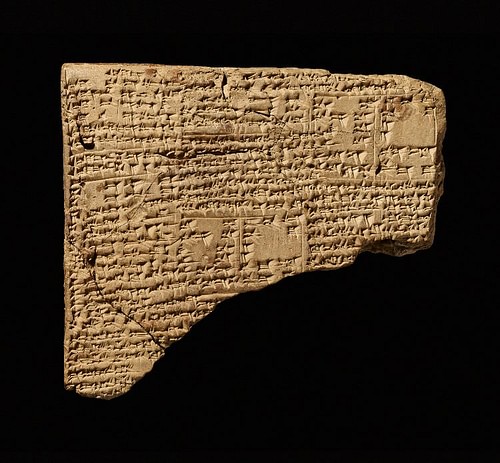

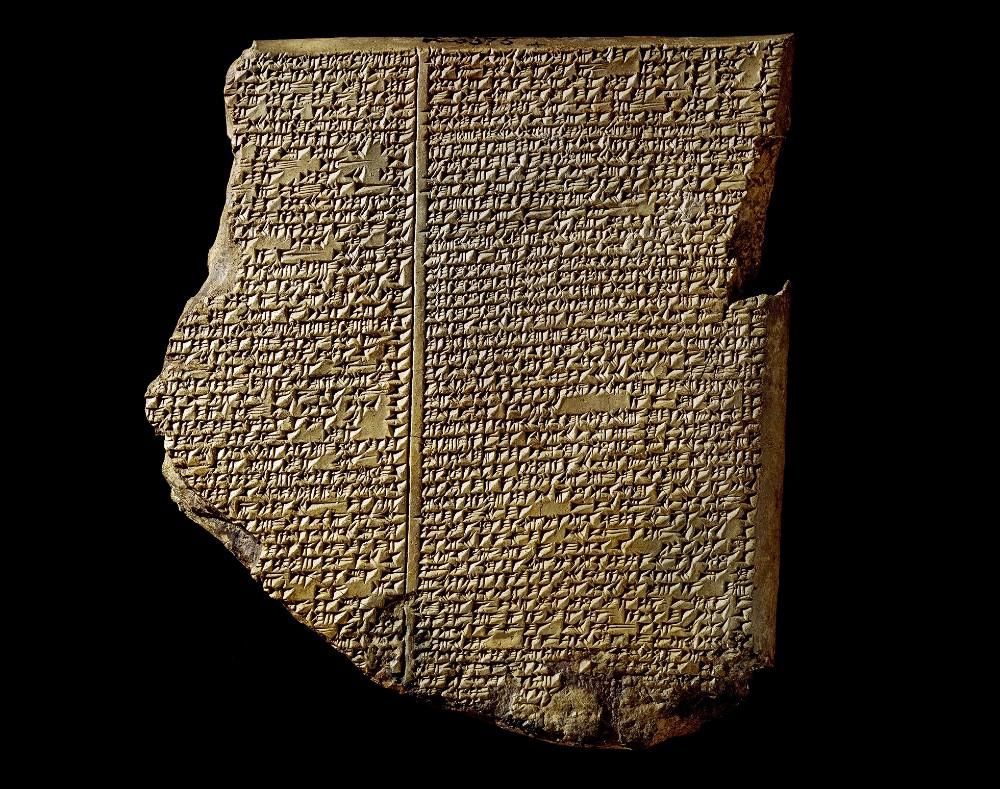

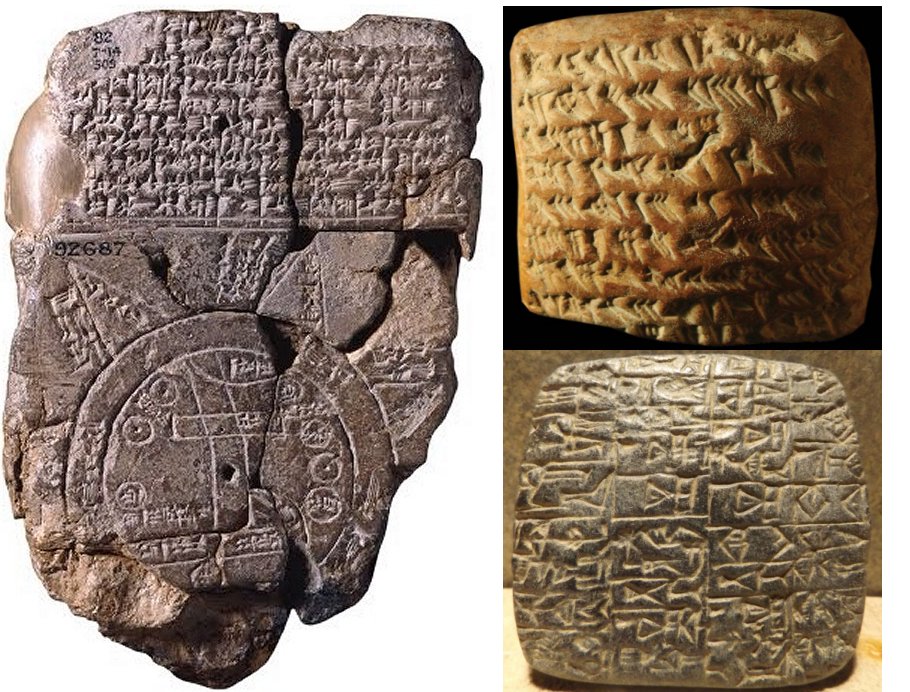

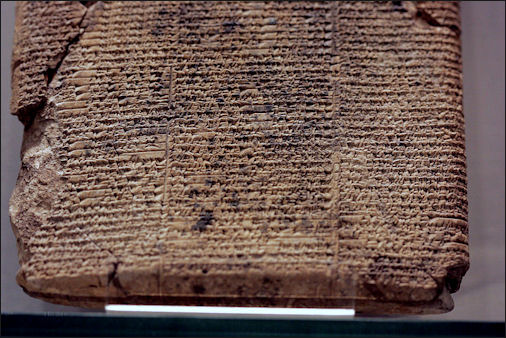

The Flood Tablet, part of the “Epic of Gilgamesh,” 7th century B.C.E., Neo-Assyrian, 15.24 x 13.33 x 3.17 cm, from Nineveh, northern Iraq (© Trustees of the British Museum )

Epic of Gilgamesh and The Flood Tablet

The best known piece of literature from ancient Mesopotamia is the story of Gilgamesh, a legendary ruler of Uruk, and his search for immortality. The Epic of Gilgamesh is a huge work, the longest piece of literature in Akkadian (the language of Babylonia and Assyria). It was known across the ancient Near East, with versions also found at Hattusas (capital of the Hittites), Emar in Syria, and Megiddo in the Levant .

This, the eleventh tablet of the Epic, describes the meeting of Gilgamesh with Utnapishtim. Like Noah in the Hebrew Bible , Utnapishtim had been forewarned of a plan by the gods to send a great flood. He built a boat and loaded it with all his precious possessions, his kith and kin, domesticated and wild animals and skilled craftsmen of every kind.

Utnapishtim survived the flood for six days while mankind was destroyed, before landing on a mountain called Nimush. He released a dove and a swallow but they did not find dry land to rest on, and returned. Finally a raven that he released did not return, showing that the waters must have receded.

This Assyrian version of the Old Testament flood story is the most famous cuneiform tablet from Mesopotamia. It was identified in 1872 by George Smith, an assistant in The British Museum. On reading the text “he … jumped up and rushed about the room in a great state of excitement, and, to the astonishment of those present, began to undress himself.”

This tablet contains both a cuneiform inscription and a unique map of the Mesopotamian world. Babylon is shown in the centre (the rectangle in the top half of the circle), and Assyria, Elam, and other places are also named. Map of the World , Late Babylonian, c. 500 B.C.E., clay, findspot: Abu Habba, 12.2 x 8.2 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum )

Map of the world

This tablet contains both a cuneiform inscription and a unique map of the Mesopotamian world. Babylon is shown in the center (the rectangle in the top half of the circle), and Assyria, Elam, and other places are also named.

The central area is ringed by a circular waterway labelled “Salt-Sea.” The outer rim of the sea is surrounded by what were probably originally eight regions, each indicated by a triangle, labelled “Region” or “Island,” and marked with the distance in between. The cuneiform text describes these regions, and it seems that strange and mythical beasts as well as great heroes lived there, although the text is far from complete. The regions are shown as triangles since that was how it was visualized that they first would look when approached by water.

The map is sometimes taken as a serious example of ancient geography, but although the places are shown in their approximately correct positions, the real purpose of the map is to explain the Babylonian view of the mythological world.

Observations of Venus

Thanks to Assyrian records, the chronology of Mesopotamia is relatively clear back to around 1200 B.C.E. However, before this time dating is less certain.

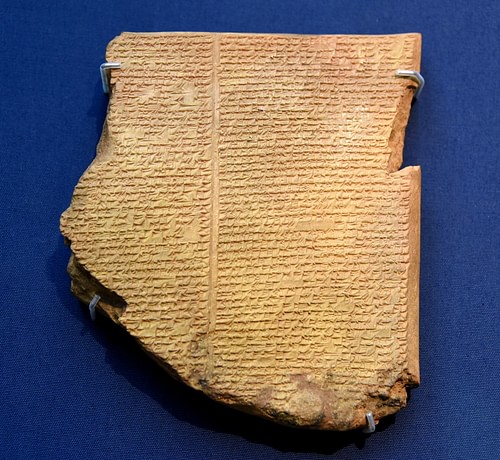

Cuneiform tablet with observations of Venus, Neo-Assyrian, 7th century B.C.E., from Nineveh, northern Iraq, clay, 17.14 x 9.20 x 2.22 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum )

This tablet is one of the most important (and controversial) cuneiform tablets for reconstructing Mesopotamian chronology before around 1400 B.C.E.

The text of the tablet is a copy, made at Nineveh in the seventh century B.C.E., of observations of the planet Venus made in the reign of Ammisaduqa, king of Babylon, about 1000 years earlier. Modern astronomers have used the details of the observations in an attempt to calculate the dates of Ammisaduqa. Ideally this process would also allow us to date the Babylonian rulers of the early second and late third millennium B.C.E. Unfortunately, however, there is much uncertainty in the dating because the records are so inconsistent. This has led to different chronologies being adopted with some scholars favoring a “high” chronology while others adopt a “middle” or “low” range of dates. There are good arguments for each of these.

Literacy was not widespread in Mesopotamia. Scribes, nearly always men, had to undergo training, and having successfully completed a curriculum became entitled to call themselves dubsar , which means “scribe.” They became members of a privileged élite who, like scribes in ancient Egypt , might look with contempt upon their fellow citizens.

Understanding of life in Babylonian schools is based on a group of Sumerian texts of the Old Babylonian period. These texts became part of the curriculum and were still being copied a thousand years later. Schooling began at an early age in the é-dubba , the “tablet house.” Although the house had a headmaster, his assistant, and a clerk, much of the initial instruction and discipline seems to have been in the hands of an elder student—the scholar’s “big brother.” All these had to be flattered or bribed with gifts from time to time to avoid a beating.

Apart from mathematics, the Babylonian scribal education concentrated on learning to write Sumerian and Akkadian using cuneiform and on learning the conventions for writing letters, contracts, and accounts. Scribes were under the patronage of the Sumerian goddess Nisaba. In later times her place was taken by the god Nabu, whose symbol was the stylus (a cut reed used to make signs in damp clay).

Deciphering cuneiform

The decipherment of cuneiform began in the eighteenth century as European scholars searched for proof of the places and events recorded in the Bible. Travelers, antiquaries, and some of the earliest archaeologists visited the ancient Near East where they uncovered great cities such as Nineveh. They brought back a range of artifacts, including thousands of clay tablets covered in cuneiform.

Scholars began the incredibly difficult job of trying to decipher these strange signs representing languages no-one had heard for thousands of years. Gradually the cuneiform signs representing these different languages were deciphered thanks to the work of a number of dedicated people.

Confirmation that they had succeeded came in 1857. The Royal Asiatic Society sent copies of a newly found clay record of the military and hunting achievements of King Tiglath-pileser I to four scholars: Henry Creswicke Rawlinson, Edward Hincks, Julius Oppert, and William H. Fox Talbot. They each worked independently and returned translations that broadly agreed with each other.

This was accepted as proof that cuneiform had been successfully deciphered, but there are still elements that we don’t completely understand and the study continues. What we have been able to read, however, has opened up the ancient world of Mesopotamia. It has not only revealed information about trade, building, and government, but also great works of literature, history, and everyday life in the region.

© Trustees of the British Museum

Additional resources

Read a chapter in our textbook, Reframing Art History , about rethinking how we approach the art of the Ancient Near East.

I.L. Finkel, “A join to the Map of the World: a notable discovery,” British Museum Magazine : 5 (Winter 1995), p. 26–27.

W. Horowitz, Mesopotamian Cosmic Geography (Winona Lake, Eisenbrauns, 1998).

I.L. Finkel, Gilgamesh: the Hero King (London, The British Museum Press, 1998).

M. Roaf, “Observations of Venus,” in The Cultural Atlas of Mesopotamia and the Ancient Near East (New York, 1990).

Cite this page

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

Visiting Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion?

You must join the virtual exhibition queue when you arrive. If capacity has been reached for the day, the queue will close early.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

The origins of writing.

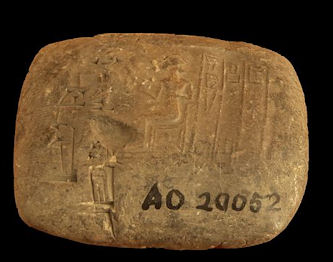

Proto-Cuneiform tablet with seal impressions: administrative account of barley distribution with cylinder seal impression of a male figure, hunting dogs, and boars

Cuneiform tablet: administrative account with entries concerning malt and barley groats

Cylinder seal and modern impression: three "pigtailed ladies" with double-handled vessels

Ira Spar Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 2004

The alluvial plains of southern Mesopotamia in the later half of the fourth millennium B.C. witnessed a immense expansion in the number of populated sites. Scholars still debate the reasons for this population increase, which seems too large to be explained simply by normal growth. One site, the city of Uruk , surpassed all others as an urban center surrounded by a group of secondary settlements. It covered approximately 250 hectares, or .96 square miles, and has been called “the first city in world history.” The site was dominated by large temple estates whose need for accounting and disbursing of revenues led to the recording of economic data on clay tablets. The city was ruled by a man depicted in art with many religious functions. He is often called a “ priest-king .” Underneath this office was a stratified society in which certain professions were held in high esteem. One of the earliest written texts from Uruk provides a list of 120 officials including the leader of the city, leader of the law, leader of the plow, and leader of the lambs, as well as specialist terms for priests, metalworkers, potters, and others.

Many other urban sites existed in southern Mesopotamia in close proximity to Uruk. To the east of southern Mesopotamia lay a region located below the Zagros Mountains called by modern scholars Susiana. The name reflects the civilization centered around the site of Susa. There temples were built and clay tablets, dating to about 100 years after the earliest tablets from Uruk, were inscribed with numerals and word-signs. Examples of Uruk-type pottery are found in Susiana as well as in other sites in the Zagros mountain region and in northern and central Iran, attesting to the important influence of Uruk upon writing and material culture. Uruk culture also spread into Syria and southern Turkey, where Uruk-style buildings were constructed in urban settlements.

Recent archaeological research indicates that the origin and spread of writing may be more complex than previously thought. Complex state systems with proto-cuneiform writing on clay and wood may have existed in Syria and Turkey as early as the mid-fourth millennium B.C. If further excavations in these areas confirm this assumption, then writing on clay tablets found at Uruk would constitute only a single phase of the early development of writing. The Uruk archives may reflect a later period when writing “took off” as the need for more permanent accounting practices became evident with the rapid growth of large cities with mixed populations at the end of the fourth millennium B.C. Clay became the preferred medium for recording bureaucratic items as it was abundant, cheap, and durable in comparison to other mediums. Initially, a reed or stick was used to draw pictographs and abstract signs into moistened clay. Some of the earliest pictographs are easily recognizable and decipherable, but most are of an abstract nature and cannot be identified with any known object. Over time, pictographic representation was replaced with wedge-shaped signs, formed by impressing the tip of a reed or wood stylus into the surface of a clay tablet. Modern (nineteenth-century) scholars called this type of writing cuneiform after the Latin term for wedge, cuneus .

Today, about 6,000 proto-cuneiform tablets, with more than 38,000 lines of text, are now known from areas associated with the Uruk culture, while only a few earlier examples are extant. The most popular but not universally accepted theory identifies the Uruk tablets with the Sumerians, a population group that spoke an agglutinative language related to no known linguistic group.

Some of the earliest signs inscribed on the tablets picture rations that needed to be counted, such as grain, fish, and various types of animals. These pictographs could be read in any number of languages much as international road signs can easily be interpreted by drivers from many nations. Personal names, titles of officials, verbal elements, and abstract ideas were difficult to interpret when written with pictorial or abstract signs. A major advance was made when a sign no longer just represented its intended meaning, but also a sound or group of sounds. To use a modern example, a picture of an “eye” could represent both an “eye” and the pronoun “I.” An image of a tin can indicates both an object and the concept “can,” that is, the ability to accomplish a goal. A drawing of a reed can represent both a plant and the verbal element “read.” When taken together, the statement “I can read” can be indicated by picture writing in which each picture represents a sound or another word different from an object with the same or similar sound.

This new way of interpreting signs is called the rebus principle. Only a few examples of its use exist in the earliest stages of cuneiform from between 3200 and 3000 B.C. The consistent use of this type of phonetic writing only becomes apparent after 2600 B.C. It constitutes the beginning of a true writing system characterized by a complex combination of word-signs and phonograms—signs for vowels and syllables—that allowed the scribe to express ideas. By the middle of the third millennium B.C. , cuneiform primarily written on clay tablets was used for a vast array of economic, religious, political, literary, and scholarly documents.

Spar, Ira. “The Origins of Writing.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/wrtg/hd_wrtg.htm (October 2004)

Further Reading

Glassner, Jean-Jacques. The Invention of Cuneiform Writing in Sumer . Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003.

Houston, Stephen D. The First Writing: Script Invention as History and Process . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Nissen, Hans J. "The Archaic Texts from Uruk." World Archaeology 17 (1986), pp. 317–34. n/a: n/a, n/a.

Nissen, Hans J., Peter Damerow, and Robert K. Englund. Archaic Bookkeeping: Early Writing and Techniques of Economic Administration in the Ancient Near East . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993.

Walker, C. B. F. Cuneiform . Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987.

Additional Essays by Ira Spar

- Spar, Ira. “ Mesopotamian Creation Myths .” (April 2009)

- Spar, Ira. “ Flood Stories .” (April 2009)

- Spar, Ira. “ Gilgamesh .” (April 2009)

- Spar, Ira. “ Mesopotamian Deities .” (April 2009)

- Spar, Ira. “ The Gods and Goddesses of Canaan .” (April 2009)

Related Essays

- The Amarna Letters

- Art of the First Cities in the Third Millennium B.C.

- The Isin-Larsa and Old Babylonian Periods (2004–1595 B.C.)

- The Middle Babylonian / Kassite Period (ca. 1595–1155 B.C.) in Mesopotamia

- Assyria, 1365–609 B.C.

- Early Dynastic Sculpture, 2900–2350 B.C.

- Early Excavations in Assyria

- Etruscan Language and Inscriptions

- Flood Stories

- The Gods and Goddesses of Canaan

- Mesopotamian Creation Myths

- The Old Assyrian Period (ca. 2000–1600 B.C.)

- Uruk: The First City

List of Rulers

- List of Rulers of Mesopotamia

- Iran, 2000–1000 B.C.

- Iran, 8000–2000 B.C.

- Mesopotamia, 1000 B.C.–1 A.D.

- Mesopotamia, 1–500 A.D.

- Mesopotamia, 2000–1000 B.C.

- Mesopotamia, 8000–2000 B.C.

- 3rd Millennium B.C.

- 4th Millennium B.C.

- Agriculture

- Anatolia and the Caucasus

- Ancient Near Eastern Art

- Archaeology

- Architecture

- Deity / Religious Figure

- Eastern Mediterranean

- Literature / Poetry

- Mesopotamian Art

- Religious Art

- Sumerian Art

- Uruk Period

- Writing Implement

Online Features

- Connections: “Taste” by George Goldner and Diana Greenwald

- Corrections

Cuneiform Writing: How Clay And Reeds Changed the World

Cuneiform writing was a powerful form of written communication in the ancient Middle East. It served as the vital cornerstone upon which modern writing was developed.

Cuneiform writing was the most widespread form of written communication created and used in the ancient Middle East. Clay cuneiform tablets and reed styluses were used to produce something that had great historical significance and contributed to the development of many modern writing forms.

The Origin Of Cuneiform Writing’s Name

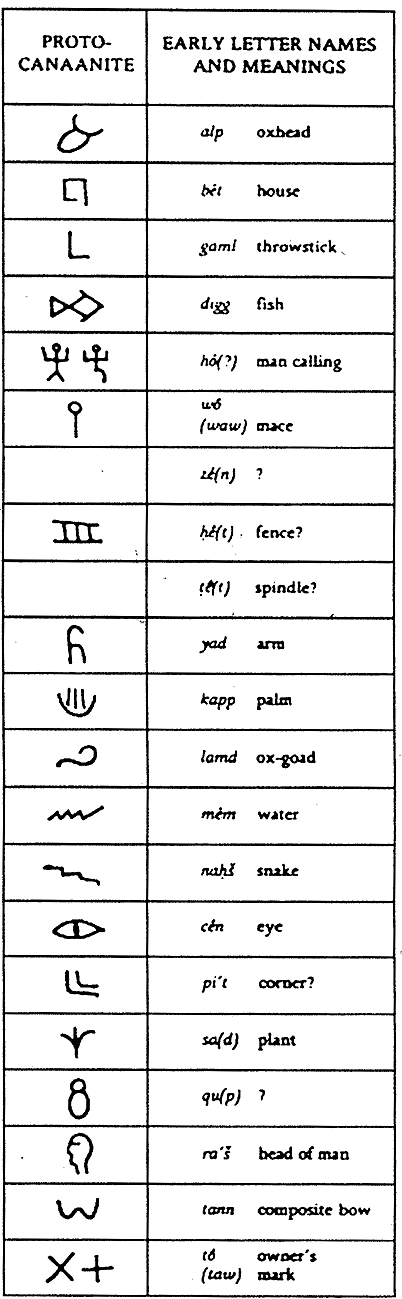

The word “cuneiform” comes from the original Latin “cuneus”, meaning “wedge-shaped” in reference to the appearance of the writing style. To create cuneiform symbols and letters, writers would use a stylus to press wedge-shaped symbols into soft clay tablets. These shapes represented various “word-signs,” also known as pictographs, and, later, “word-concepts,” the closest approximation to modern-day words.

The original pictographic symbols that predated cuneiform writing were largely organized into vertical columns, but once the wedge-shaped pen was created, that changed. Instead, people began writing in horizontal rows using the wedge shape to push signs into the malleable clay. That method was far easier to maintain than the original carving of symbols into clay with a sharpened reed , allowing cuneiform to spread farther across the Middle East than any writing system that came before it.

The Creators Of Cuneiform

The creation of cuneiform writing is attributed to the ancient Sumerians of Mesopotamia in modern-day Iraq. The Sumerians are among the oldest civilizations in history, predating even the Pyramids of Giza . They created a great many useful things, but the cuneiform stands out as their most significant cultural contribution.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription.

Despite its Sumerian origins, cuneiform was also adopted, improved, and expounded upon by several other ancient civilizations. Among these were the Akkadians, the Babylonians, the Elamites, the Hittites, the Assyrians, and the Hurrians. Each culture improved the writing form in one way or another, enhancing its economic utility until the Phoenecian alphabet eventually replaced it. It is important to note that because of all the various changes and enhancements made to cuneiform, by the time the system was dismissed as a relevant means of communication, it had split to encompass multiple different writing styles that used individual wedge-shapes and was no longer a singular method.

Proto-Cuneiform

The earliest version of cuneiform writing is known today as “proto-cuneiform.” It originally was developed near the end of the fourth millennium B.C. and was widely embraced. This type of writing centered entirely on pictures of highly concrete images and ideas. Subjects for early cuneiform tablets included such things as kings, battles, grains, and floods. Still, they could also communicate numbers, as represented by circular impressions, and economic information used in temples or other large gathering places to hold land records.

Wide-Spread Use Of Cuneiform Tablets and Writing

Until the alphabetic script was developed after 100 BCE, cuneiform writing was widely used across every great Mesopotamian civilization. The Akkadians, Babylonians, Elamites, Hittites, and Assyrians were several among a long list of ancient societies that embraced cuneiform. They all had many reasons for doing so, as a writing system was becoming an invaluable asset to developing societies.

Originally, the cuneiform writing style was developed to play an economic role–maintaining inventories, counting items, and general related purposes. However, with the ease of its use and readily-available materials, the clay-and-reed writing system soon spread. Cuneiform began to be used to record maps, laws, medical manuals, and religious stories as it was developed. The clay cuneiform tablets created for preserving writings were also extensively used in schools, often recycled by students unless the information they contained was too valuable to lose. If it were, the tablet would be baked in a kiln to preserve the writing, and many of these cuneiform tablets still exist to be seen today in various museums.

The Epic Of Gilgamesh

One of the greatest and most well-known literature pieces to come from cuneiform writing was the Epic of Gilgamesh . This epic poem is thought to date back to 2100 B.C. in the Third Dynasty of Ur, but the surviving cuneiform tablets available today only date to 1800 B.C. It was recorded on Babylonian cuneiform tablets by Sumerians in Mesopotamia, and it is predated as a religious text only by the Pyramid Texts .

The original epic tells the story of Uruk’s king, Bilgamesh, and Enkido, a wild man sent to stop the king from oppressing his people. The two undertake many quests and adventures together once Enkido becomes civilized, and they become good friends. However, once the pair kills a beast sent by a goddess, Enkido is put to death by the goddess, thus completing the first half of the story. In the second, Bilgamesh, or Gilgamesh in the modern translation, commits himself to a long, danger-filled journey to discover the secret of immortal life in light of his friend’s passing. Many great stories have been written about Gilgamesh and his trials, and they are featured in many modern adaptations. These include The Twelve Dancing Princesses (1857), collected by Jakob and Wilhelm Grimm, The Great American Novel (1973) by Phillip Roth, and Warm Bodies (2011) by Isaac Marion.

The Extinction Of Cuneiform

By the year 1,000 A.D., cuneiform writing became almost entirely extinct. Everyone had turned to more diverse writing methods that allowed for greater communication, and cuneiform essentially became a dead writing system until the 19th century. By then, researchers began to decipher the various symbols and meanings to translate great Mesopotamian works of previously unknown literature.

Cuneiform’s Contribution To Class-Free Literacy

Aside from unifying a writing system for the ancient Middle East, cuneiform also developed into styles that any citizen could read. It was meant to be used by all–not just the upper class. Various scripts and basic symbols were put in place specifically because of how easy to use they were. That is not to say that all cuneiform was easy to read and interpret by everyone. Rather, the ancient Sumerians intentionally took steps to ensure that everyone had the same ability to communicate via clay and reed.

Average citizens in any Mesopotamian culture were able to pick up the most basic, functional knowledge of cuneiform that they could then put to work for them in many ways. Most citizens did not need to keep lengthy economic or medical documents, but they still maintained various personal letters and business-related texts. Meanwhile, those with more scholastic inclinations were able to study the writing system more thoroughly. They began recording medicines, diagnoses, mathematical equations, and much, much more. People also used cuneiform to embrace creativity. This was done largely by those with the highest amount of literacy . These people could fine-tune their writing abilities to produce great stories, epic poems, and other artworks still admired today.

The Evolution Of Cuneiform Writing

Thanks to the wide-spread use of cuneiform writing, people soon realized how important it was to have a means by which they could record various pieces of information. From cuneiform symbols to hieroglyphs and beyond, ancient societies’ pictographic writing systems were greatly appreciated in their time. But as time progressed and societies advanced, people wanted a new way of writing. A way that wouldn’t limit them with pictures and symbols but would grant them access to their entire vocabularies in written form. The need for an alphabet soon became blindingly apparent.

Therefore, around 1500 B.C., the Proto-Sinaitic alphabet came into existence. Drawing largely from the easy pictographs of cuneiform and hieroglyphics, the system entered a three-phase cycle. The first phase was based on acrophony–using signs to take the place of the first letter of the word they represented. For example, the letter “H” could be represented by a picture of a house since the first letter in “house” is “H.” This phase most closely resembled the writing forms to date.

The second phase was consonantal, focusing on spelling words based on closures in the breathing channel when certain letters like “B,” “M,” and “P,” were pronounced. Finally, the third phase was a compilation and summation of all other writing styles in developing twenty-two signs to represent different letters instead of the previous hundreds of options. It was this writing form, derived from cuneiform, that is the origin of Western writing today.

Cuneiform Writing: Key Takeaways

Cuneiform writing was a system that used the most basic of tools to bring about one of the greatest inventions of the ancient Middle East . It allowed for records to be kept, art to be created, and societies to be more economically successful while promoting literacy for all and not just the aristocrats. Cuneiform is a system that is out of date as a whole now, but one that is time-honored because it is the cornerstone upon which the basis for modern writing sits.

Ancient Sumer & The Sumerian Civilization: Here’s What We Know

By Hannah McCall BA Criminal Justice & Legal Studies, BA English Hannah graduated college with twin B.A.s in English and Criminal Justice & Legal Studies and intentionally made time throughout her education to pursue her lifelong love of history by serving on staff for her university’s history club. Hannah particularly loves studying mythologies and legends from a variety of cultures but enjoys Greek, Norse, Egyptian, and Hindu mythologies most of all.

Frequently Read Together

12 Surprising Facts About the Egyptian Pyramids

How Ancient Writing Was Developed For Use in Religion & Magic

The Epic of Gilgamesh: 3 Parallels from Mesopotamia to Ancient Greece

The World's Oldest Writing

Features May/June 2016

By The Editors

- Share to Facebook

- Share via Email

- Copy permalink to clipboard https://archaeology.org/collection/the-worlds-oldest-writing/ Copied to clipboard

In early 2016 , hundreds of media outlets around the world reported that a set of recently deciphered ancient clay tablets revealed that Babylonian astronomers were more sophisticated than previously believed. The wedge-shaped writing on the tablets, known as cuneiform, demonstrated that these ancient stargazers used geometric calculations to predict the motion of Jupiter. Scholars had assumed it wasn’t until almost A.D. 1400 that these techniques were first employed—by English and French mathematicians. But here was proof that nearly 2,000 years earlier, ancient people were every bit as advanced as Renaissance-era scholars. Judging by the story’s enthusiastic reception on social media, this discovery captured the public imagination. It implicitly challenged the perception that cuneiform tablets were used merely for basic accounting, such as tallying grain, rather than for complex astronomical calculations. While most tablets were, in fact, used for mundane bookkeeping or scribal exercises, some of them bear inscriptions that offer unexpected insights into the minute details of and momentous events in the lives of ancient Mesopotamians.

First developed around 3200 B.C. by Sumerian scribes in the ancient city-state of Uruk, in present-day Iraq, as a means of recording transactions, cuneiform writing was created by using a reed stylus to make wedge-shaped indentations in clay tablets. Later scribes would chisel cuneiform into a variety of stone objects as well. Different combinations of these marks represented syllables, which could in turn be put together to form words. Cuneiform as a robust writing tradition endured 3,000 years. The script—not itself a language—was used by scribes of multiple cultures over that time to write a number of languages other than Sumerian, most notably Akkadian, a Semitic language that was the lingua franca of the Assyrian and Babylonian Empires.

After cuneiform was replaced by alphabetic writing sometime after the first century A.D. , the hundreds of thousands of clay tablets and other inscribed objects went unread for nearly 2,000 years. It wasn’t until the early nineteenth century, when archaeologists first began to excavate the tablets, that scholars could begin to attempt to understand these texts. One important early key to deciphering the script proved to be the discovery of a kind of cuneiform Rosetta Stone, a circa 500 B.C. trilingual inscription at the site of Bisitun Pass in Iran. Written in Persian, Akkadian, and an Iranian language known as Elamite, it recorded the feats of the Achaemenid king Darius the Great (r. 521–486 B.C. ). By deciphering repetitive words such as “Darius” and “king” in Persian, scholars were able to slowly piece together how cuneiform worked. Called Assyriologists, these specialists were eventually able to translate different languages written in cuneiform across many eras, though some early versions of the script remain undeciphered.

Today, the ability to read cuneiform is the key to understanding all manner of cultural activities in the ancient Near East—from determining what was known of the cosmos and its workings, to the august lives of Assyrian kings, to the secrets of making a Babylonian stew. Of the estimated half-million cuneiform objects that have been excavated, many have yet to be catalogued and translated. Here, a few fine and varied examples of some of the most interesting ones that have been.

The World's Oldest Writing May/June 2016

Last Tablets

Recommended Articles

Digs & Discoveries July/August 2024

Bronze Age Beads Go Abroad

Rubber Ball Recipe

Black Magic Seeds

A Friend for Hercules

More to Discover

Letter from Guatemala March/April 2016

Maya Metropolis

Beneath Guatemala’s modern capital lies the record of the rise and fall of an ancient city

Artifacts March/April 2016

Egyptian Ostracon

Around the World March/April 2016

Digs & Discoveries March/April 2016

Legends of Glastonbury Abbey

Features March/April 2016

Öland, Sweden. Spring, A.D. 480

A hastily built refuge—a grisly massacre—a turbulent period in European history

NEVER MISS AN UPDATE

Next steps: sync an email add-on.

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

- Writing as a system of signs

- The functions of writing

- Types of writing systems

Sumerian writing

- Alphabetic systems

- Chinese writing

- Japanese writing

- Korean writing

- The rise of literacy

- Literacy and schooling

- Where did writing first develop?

- Why was writing invented?