Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 22 September 2023

How does the COVID-19 pandemic influence students’ academic activities? An explorative study in a public university in Bangladesh

- Bijoya Saha 1 ,

- Shah Md Atiqul Haq ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9121-4028 1 &

- Khandaker Jafor Ahmed 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 602 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

6272 Accesses

1 Citations

Metrics details

The global impact of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) has spared no sector, causing significant socioeconomic, demographic, and particularly noteworthy educational repercussions. Among the areas significantly affected, the education systems worldwide have experienced profound changes, especially in countries like Bangladesh. In this context, numerous educational institutions in Bangladesh decided to temporarily suspend classes in situations where a higher risk of infection was perceived. Nevertheless, the tertiary education sector, including public universities, encountered substantial challenges when establishing and maintaining effective online education systems. This research uses a qualitative approach to explore the ways in which the COVID-19 pandemic has influenced the academic pursuits of students enrolled in public universities in Bangladesh. The study involved the participation of 30 students from a public university, who were interviewed in-depth using semi-structured interviews. Data analysis was conducted using thematic analysis. The findings of this study reveal unforeseen disruptions in students’ learning processes (e.g., the closure of libraries, seminars, and dormitories, and the postponement of academic and administrative activities), highlighting the complications associated with online education, particularly the limitations it presents for practical and laboratory-based learning. Additionally, a decline in both energy levels and study hours has been observed, along with an array of physical, mental, and financial challenges that directly correlate with educational activities. These outcomes emphasize the need for a hybrid academic approach within tertiary educational institutions in Bangladesh and other developing nations facing similar sociocultural and socioeconomic contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

The sudden transition to remote learning in response to COVID-19: lessons from Malaysia

Uncovering Covid-19, distance learning, and educational inequality in rural areas of Pakistan and China: a situational analysis method

Assessing the challenges of e-learning in Malaysia during the pandemic of Covid-19 using the geo-spatial approach

Introduction and background.

The current global issue, the COVID-19 pandemic caused by the novel coronavirus, is impacting both developed and developing nations (World Health Organization [WHO], 2020 ). Many countries have implemented worldwide lockdowns, enforced social isolation measures, bolstered healthcare services, and temporarily closed educational institutions in order to curb the spread of the virus. According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO, 2020a ), the closure of schools, colleges, universities, and other educational establishments due to COVID-19 has impacted over 60% of students worldwide. The pandemic is inflicting significant damage upon the global education sector. University students, in particular, are grappling with notable disruptions to their academic and social lives. The uncertainties surrounding their future goals and careers, coupled with the limitations on social interaction with friends and family (Cao et al., 2020 ), have left them contending with altered living conditions and increased workload demands compared to the time before traditional classroom teaching was suspended. Despite these challenges, the university setting and its associated activities have become the sole familiar constant amidst their otherwise transformed lives (Neuwirth et al., 2021 ). The pandemic’s interference with academic routines has substantially interrupted students’ educational journeys (Charles et al., 2020 ). The shutdown of physical classrooms and the halt of academic operations due to university closures (Jacob et al., 2020 ) have disrupted students’ study routines and performance. Prolonged periods of solitary studying at home have been linked to heightened stress levels (e.g., depression), feelings of cultural isolation (e.g., loneliness), and cognitive disorders (e.g., difficulty in retaining recent and past information) (Meo et al., 2020 ). Many educational institutions have responded to COVID-19 by transitioning from traditional face-to-face instruction to online alternatives to minimize educational disruptions. However, research indicates that students often feel uncomfortable and dissatisfied with online learning methods (Al-Tammemi et al., 2020 ). Beyond the challenges posed by online education, such as limited access to electronic devices, restricted internet connectivity, and high internet costs, students are also faced with adapting to new online assessment techniques and technologies, engaging with instructors, and navigating the complexities of the shift to online delivery (Owusu-Fordjour et al., 2020 ).

Bangladesh, a South Asian developing nation, has also been significantly impacted by COVID-19. To prevent the virus’s spread, the country opted to close its educational institutions, leading to students staying home to maintain social distancing (Institute of Epidemiology Disease Control and Research [IEDCR], 2020 ). The higher education sector in Bangladesh encountered challenges during this period. The closure of educational institutions disrupted students’ learning activities (UNESCO, 2020b ; Al-Tammemi et al., 2020 ). Modern technology tools and software have become the means through which most university students engage in study-related tasks at home during their free time. The shift to online education is seen as a fundamental transformation in higher education in Bangladesh, departing from the traditional academic approach. However, for many teachers and administrators at Bangladeshi institutions, online education is a new frontier. Face-to-face teaching and learning have been the predominant mode at Bangladeshi universities for a long time, making it challenging to embrace the shift to an advanced online environment.

Bangladesh hosts more than 5,000 higher education institutions, encompassing both government and private universities, vocational training centers, and affiliated colleges, with an enrollment of 4 million students (Ahmed, 2020 ). In response to the health crisis, the government introduced emergency online education methods to enable students to continue learning despite temporary school closures. Challenges such as overcrowding, unequal access to technology compared to pre-COVID-19 times, and the difficulties in swift adaptation led to delays, teaching interruptions, and the adoption of extended distance learning. These issues were further exacerbated by the ongoing overcrowding, which posed a risk for the resurgence or spread of COVID-19 if in-person teaching were to resume. Undoubtedly, COVID-19 has left a profound impact on university education in Bangladesh. Despite numerous studies on COVID-19’s impact on a range of topics, the effects on higher academic activities in Bangladesh have received limited research attention. Shahjalal University of Science and Technology (SUST), a public institution and one of Bangladesh’s universities, stands as an example. Given the COVID-19 regulations, this study aims to investigate the effects of online learning on the academic endeavors of university students in Bangladesh. The study also seeks to assess students’ satisfaction with online education, their adaptability to this new format, and their participation in extracurricular activities during the COVID-19 period, in addition to their academic pursuits.

Literature review

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a notable impact on the landscape of online teaching and learning (Aldowah et al., 2019 ; Basilaia and Kvavadze, 2020 ; Khan and Abdou, 2021 ). Notably, Rameez et al. ( 2020 ) emphasize that a critical hurdle faced in Sri Lanka revolves around the lack of virtual teaching and learning proficiency among both educators and students, impeding a smooth educational process. University shutdowns and dormitory quarantines due to COVID-19 have significantly disrupted students’ learning abilities (Burgess and Sievertsen, 2020 ; Kedraka and Kaltsidis, 2020 ). Difficulties have arisen, encompassing challenges related to online lectures, exams, evaluations, reviews, and tutoring. While Kedraka and Kaltsidis ( 2020 ) laud online learning as modern, relevant, suitable, and advantageous, they also underline its drawbacks. Notably, it has led to a substantial loss of student social interaction, interrupting group learning, in-person interactions, and connections with peers and educators (Kedraka and Kaltsidis, 2020 ; Rameez et al., 2020 ).

In the context of higher education institutions in Bangladesh, Khan and Abdou ( 2021 ) propose adopting the flipped classroom method to sustain teaching and learning during the COVID-19 epidemic, an approach echoed in Alam’s ( 2021 ) comparison of pre-and post-pandemic students. Alam’s findings reveal better academic performance among post-pandemic students. Conversely, Biswas et al. ( 2020 ) report a positive attitude toward mobile learning among most students in Bangladesh, finding it effective in bridging knowledge gaps created by the pandemic. Emon et al. ( 2020 ) highlight discontinuities in learning opportunities in Bangladesh, emphasizing the need for technical solutions to maintain effective education systems during the pandemic. Ahmed’s ( 2020 ) study on tertiary students unveils a lack of technology and connectivity, leading to delays in coursework, exams, results, and class promotions. These disruptions have exacerbated student anxiety, frustration, and disappointment. Burgess and Sievertsen ( 2020 ) note students’ concerns about falling behind academically, missing job opportunities, facing post-graduation employment challenges, and enduring emotional pressure.

Rajhans et al. ( 2020 ) observe that the pandemic has driven significant advancements in academies worldwide, particularly in adopting online learning. A similar impact is seen in India’s optometry academic activities, where quick adoption of online learning supports both students and practising optometrists (Stanistreet et al., 2020 ). Consequently, educational events like commencement ceremonies, seminars, and sports have been postponed or canceled (Liguori and Winkler, 2020 ; Sahu, 2020 ; Shrestha et al., 2022 ), necessitating remote work for academic support staff (Abidah et al., 2020 ).

In higher education, teachers play a pivotal role in implementing online learning. The sudden shift to online education due to the pandemic has left some instructors grappling with limited IT skills and a challenge in maintaining the same level of engagement as in face-to-face settings (Meo et al., 2020 ; Wu et al., 2020 ). Furthermore, the transition has led to concerns about effective scheduling, course organization, platform selection, and measuring online education’s impact (Wu et al., 2020 ; Toquero, 2020 ). Zawacki-Richter ( 2021 ) predicts digital advancements in German higher education, driven by the crisis, faculty dedication, and higher expectations.

COVID-19’s influence on education extends to students’ mental well-being. Some students’ inadequate home networks have hindered access to online materials, exacerbating their distress (Akour et al., 2020 ). Mental health challenges stem from various sources, including parental pressures, financial strains, and family losses (Bäuerle et al., 2020 ). Long-term quarantine intensifies psychological and learning challenges, impacting students’ overall performance and study time (Farris et al., 2021 ; Meo et al., 2020 ). Blake et al. ( 2021 ) advocate for colleges to address students’ isolation needs and prepare for long-term effects on student welfare.

With its large population, Bangladesh grapples with challenges in effective technology adoption, especially with online education becoming an alternative system during the pandemic. The overcrowding issue has been exacerbated by the need for distance learning, causing skill transfer difficulties and delays. Given these circumstances, this study delves into how COVID-19 affects online education and Bangladeshi university students’ academic endeavors, offering insights from the students’ perspective. Unlike prior studies focusing on challenges, this research also uncovers opportunities triggered by the pandemic. Such a nuanced view of the impacts of COVID-19 on education will help formulate effective policies and programs to elevate online learning quality in Bangladesh’s higher education.

Methodology

Research design.

This study employs a descriptive research approach, which aims to portray a situation, an individual, or an event and illustrate phenomena’ connections and natural occurrences (Blumberg et al., 2005 ). A qualitative approach was adopted to analyze specific circumstances thoroughly. Grounded theory, developed by Glaser and Strauss in 1967, served as the overarching framework for this research (Denscombe, 2007 ). Grounded theory follows an inductive research approach that refrains from starting with preconceived assumptions and instead generates new questions as insights emerge. This methodology rests upon participants’ perspectives, experiences, and realities (Bytheway, 2018 ).

For this study, in-depth interviews were employed to assess how the recent pandemic impacted students’ academic engagement and the factors related to COVID-19 that influenced their academic activities. This examination sought to understand the pandemic’s implications on students, the facets of these consequences, and which students might be more susceptible to these effects concerning academic performance and engagement. Conducted over the phone, the in-depth interviews featured a relatively small of participants, leading to the choice of a descriptive study design. This design, however, is unable to establish causal relationships, which could be explored and compared using quantitative methodologies. Moreover, the potential influence of the interviewer’s presence during phone interviews was considered.

Study locations, population, and sample

This study delves into the academic challenges encountered by students during the COVID-19 lockdown. Shahjalal University of Science and Technology (SUST), a public university in Bangladesh’s Sylhet district, was purposefully selected for the study due to its high student enrollment. The participants consist of students from diverse disciplines of SUST. Employing purposive sampling, a non-probability sample technique, the research collected qualitative data through volunteers recruited via social media advertisements within a university group on Facebook. Participants were informed of the study’s objectives, and the data collection spanned from September 20 to October 3, 2021, supplemented by additional interviews from December 24 to December 27, 2021, to ensure data saturation. Information from 30 university students was gathered, covering a range of faculties. Table 1 provides an overview of participant’s age, gender, and educational level: 56.7% of participants identified as female, and 43.3% as male. In terms of educational distribution, 87% were enrolled in Bachelor’s degree programs, while 13% were pursuing Master’s degrees. The participants’ ages from 18 to 25 years, with a mean of 21.37 and a standard deviation of 1.99.

Data collection and data analysis

The research team, comprising a graduate student (B.S.) with qualitative research training, a sociology professor (S.M.A.H., PhD) with extensive qualitative and quantitative experience, and a sociology postdoctoral fellow (K.J.A., PhD), handled data collection and analysis. In-depth interviews, facilitated by a semi-structured interview instrument, were employed to gather for this qualitative study. This approach allowed participants to provide substantial insights by responding to open-ended questions on the research topic. The interviews explored the impact of COVID-19 on students’ academic activities, their online learning experiences, and the effects of the pandemic on educational pursuits. Ethical guidelines concerning confidentiality, informed consent, the use of data only for the present study, and non-disclosure were followed throughout the data collection, and the participation was voluntary, and they could withdraw their participation at any time during the research process. Participants were informed about the research through a participation information sheet prior to their involvement, and their consent was obtained in written form through email correspondence. Interviews were carried out in Bengali by the first author (B.S.) phone calls and were recorded. Subsequently, the recorded interviews were promptly transcribed into English using a word processing program.

The collected data underwent thorough analysis involving coding in Microsoft Excel, interpretation, and validation through discussions among the research team. Themes and subthemes emerged during the coding process, guiding the categorization and organization of data. Saturation was achieved after the 30th interview, indicating data sufficiency. The research team, without prior relationship with participants, ensured the reliability and credibility of the analysis through verbatim transcripts, individual and group analysis, and written notes.

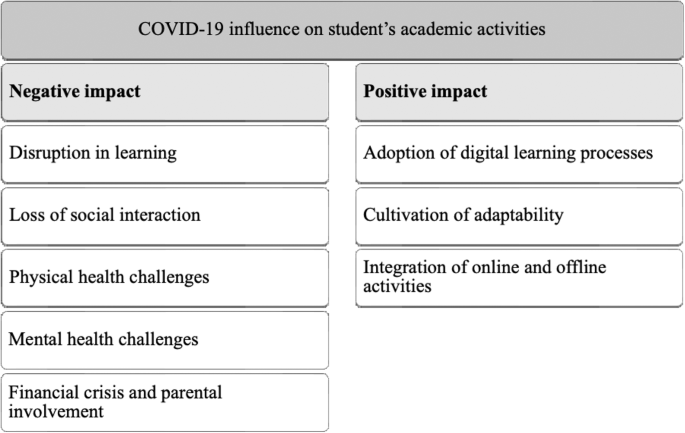

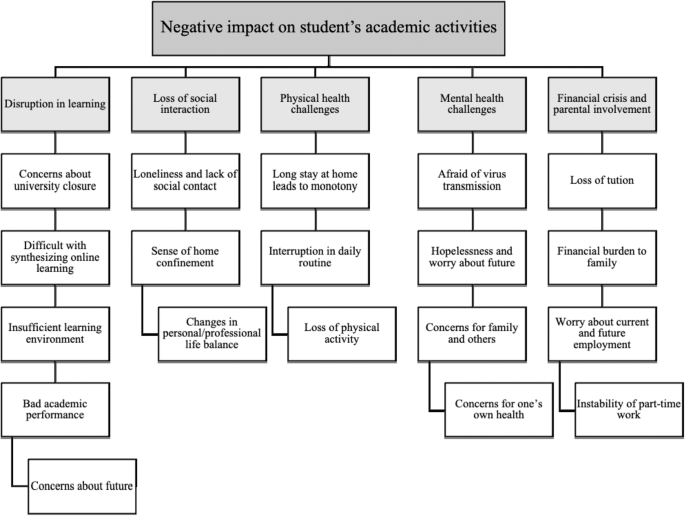

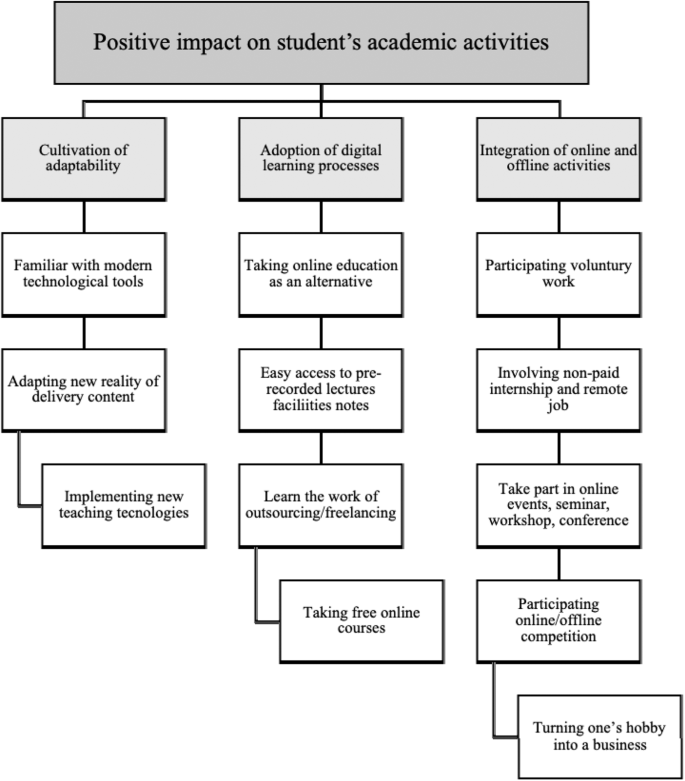

The research identified eight themes (see Fig. 1 ) that characterized two main factors: the negative impact on student academic activities (see Fig. 2 ) and the positive impact on academic activities (see Fig. 3 ). The negative impact encompassed themes such as learning disruption, loss of social interaction, physical and mental health issues, financial struggles, and parental involvement. The positive impact included themes such as digital learning, adaptability, and engagement in online/offline activities. In-depth analyses were conducted for each theme, accompanied by citations indicating the participant’s identification number and gender.

Note: see Figs. 2 and 3 for subthemes of academic activities.

Negative impacts on student’s academic activities.

Positive impact on student’s academic activities.

Negative impact on student’s academic activities

Disruption in learning.

In the early months of 2020, the global spread of COVID-19 prompted the government of Bangladesh to close all educational institutions due to suspicious incidents. Participants unanimously expressed their initial surprise and frustration at the abrupt closure but soon recognized its necessity in the face of the pandemic. Libraries, seminars, and dormitories were immediately shut down. This posed a challenge for students residing on campus, who had quickly departed and lacked access to necessary resources. Academic and administrative activities across these institutions came to a halt. Alongside the strain of crowded classrooms, students voiced discontent, uncertainty, and anxiety about their studies, assessments, and outcomes.

Several participants shared their experiences:

“I used to follow the teachers’ instructions, attend lectures, and complete projects. But now that classes are suspended, my studying has come to a halt. I worry this pause might be prolonged.” (M 7 , M 14 , F 17 )

These students identified various obstacles to effective learning. They found the absence of a structured routine for attending classes and lectures at home demotivating. Although they kept busy with other activities, they noted a decline in their enthusiasm for education. They struggled to retain and apply the knowledge gained from classes, attributing it to the sudden disruption. Limited access to educational materials and books, often left behind in campus dormitories, also hindered their learning progress. Reading from the library, they mentioned, was a costly alternative. As a result, the inability to access essential resources posed a challenge. Furthermore, students found it difficult to concentrate on their studies due to unsuitable home environments, impacting their academic performance.

A participant shared:

“I need a quiet study environment, which I can’t find at home. I used to study at departmental seminars or the library. Even though I’ve been home, I still struggle to concentrate.” (M 1 )

Another student added:

“The university closed shortly after I enrolled. As a result, I missed out on getting to know my peers, professors, and seniors. I couldn’t enjoy the university’s cultural activities and events.” (F 30 )

Several participants said,

“The vast majority of their courses are laboratory-based. Taking these classes online during COVID-19 made them difficult to understand, and even the teachers struggled to understand them.” (M 4, M 19, F 29, F 30 )

Loss of social interaction

Students strongly desired to return to their educational environment and reconnect with peers and professors. Collaborative problem-solving and discussions with batchmates were a common practice, and the absence of in-person interactions disrupted this dynamic. They found comfort in studying together on campus, rather than in isolation at home. The prolonged separation from friends and classmates resulted in a breakdown of peer learning processes. While attempts were made to stay connected through digital means, participants found these interactions lacking in the vibrancy of face-to-face communication. Recalling earlier interactions for study or leisure became challenging, eroding the motivation to learn.

One participant noted:

“Group study is no longer possible due to the pandemic, and my interest in studying has waned. This could pose communication challenges even after the pandemic subsides.” (M 19 )

Others explained:

“I can’t interact with my friends or have the same enjoyment as before due to extended periods at home. This saddens me. It’s made studying with them much harder. I anticipate a communication gap post-pandemic, as we might forget how to engage openly.” (F 12 )

Another student expressed:

“I was admitted to the university, but it closed just a month later. This meant that I didn’t have the chance to get to know my fellow students, teachers, or seniors. I also missed out on the university’s cultural activities, concerts, and festivals.” (F 29 )

Physical health challenges

The participants pointed out that COVID-19 had wide-ranging effects on their daily routines. They noted shifts in sleep patterns, eating habits, and physical activity levels, leading to daytime fatigue, disrupted sleep, reduced appetite, and sedentary behavior, resulting in weight gain. These physical symptoms contributed to a sense of exhaustion, weakness, and overall discomfort. Many participants linked these physical challenges to their waning interest in studying at home, creating a disconnect from their academic pursuits.

One participant shared:

“I have gained weight due to excessive eating and spending all day at home. My body feels heavy, my mind feels foggy, and I experience a mix of happiness and lethargy. Is this is an environment conducive to studying?” (M 4 )

Another student explained:

“I have polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), which requires a balanced lifestyle. I exercised and ate well on campus, keeping my physical condition in check. But with the shift to remote learning, my routine changed, worsening my physical health. This has affected my concentration on studies, adding to my frustration.” (F 9 )

Mental health challenges

Stress emerged as a prevailing mental health concern among participants. They exhibited heightened anxiety, not only due to the pandemic itself but also concerning their educational commitments. In addition to fears of contracting COVID-19, participants expressed concern about maintaining organization, motivation, and adapting to new learning methods. Worries extended to upcoming courses, exams, result publication, and starting a new academic year. The post-epidemic landscape was also concerned with the potential pressure to expedite course completion. These uncertainties overshadowed the primary goals of their educational journey.

A number of participants found themselves increasingly frustrated when contemplating their future professional aspirations. Their anxiety and anger stemmed from the inability to finish their final year of university as planned. The pandemic further amplified their concerns about securing employment and setting a stable foundation for themselves. They argued that an extended academic year could impede their career opportunities and create challenges in securing a post-graduation job. Moreover, there was a prevailing fear that their relatively advanced age might hinder their employability in Bangladesh.

Several participants elaborated:

“Most government and private sector jobs in Bangladesh have age restrictions. Exam topics often diverge from the academic curriculum. The prolonged academic year due to COVID-19 makes me uncertain about my job prospects. Global economic instability adds to my worries. This anxiety affects my ability to focus, leaving me disinterested in everything, including studying .” (M 16 , M 4 , F 10 )

For female participants, the pressure to marry before completing their education emerged as an additional concern, leading to emotional distress and academic setbacks. Some female participants added:

“Given the uncertainty surrounding when the pandemic would conclude and when we would have the opportunity to complete our studies, our families urged us to consider marriage before finishing our education. This predicament weighed heavily on us, causing a sense of melancholy, and subsequently, academic performance suffered as we grappled with the idea of getting married before our graduation.” (F 17 , F 20 , F 21 , F 10 )

Financial crisis and parental involvement

COVID-19’s economic impact was deeply felt among participants, who relied on part-time jobs or tuition to support themselves. The abrupt halt in academic and work activities severely impacted their financial stability. With local and global economies suffering, family incomes dwindled, making it harder for students to afford internet connectivity and online resources.

“My ability to attend online classes suffered due to my family’s limited finances. I feared my grades would suffer and I might fail courses.” (F 28 )

Additionally, the prolonged closure of institutions resulted in difficult conditions for many students. Financial hardships and familial challenges, such as job loss, reduced income, and parental pressure, further exacerbated students’ emotional distress. Having lost a parent before the pandemic, some students found it even harder to make ends meet.

One participant explained:

“I supported my family and myself with tuition before COVID-19. Losing my father earlier made me the sole provider. But with COVID-19, I had to forfeit my tuition and supporting my family became a struggle.” (M 27 )

Positive impact on student academic activities

Adoption of digital learning processes.

Amidst the challenges posed by the pandemic, integrating technology into education stands out as a significant advantage. The global situation intensified the strong connection between technology and education. The closure of institutions led to a swift transformation of on-campus courses into online formats, turning e-learning into a vital method of instruction. This shift extended beyond content delivery to encompass pedagogy and assessment methods changes. The participants adapted to Zoom, Google Meet, and Google Classroom platforms for attending online lectures. They found pre-recorded classes accessible through online media, simplifying note-taking. Asking questions online became convenient, and submitting online assignments posed no significant hurdles. Many students also embraced the opportunity to engage with the free online courses from platforms such as Coursera, edX, and Future Learn, further enhancing their skill sets.

“Recorded lectures are a boon; I can revisit them whenever I want. I don’t need to focus on note-taking during class since I can easily access the lectures later.” (F 3 )

Another participant noted:

“I enrolled in several free online courses during COVID-19, using platforms such as Coursera, edX, and Future Learn. These tasks boosted my productivity and introduced me to the world of freelancing.” (F 6 )

Cultivation of adaptability

The pandemic propelled digital technologies to the forefront of education. The transition to digital learning required both educators and students to enhance their technological literacy. This shift also paved the way for pedagogy and curriculum design innovation, fostering changes in learning methods and assessment techniques. As a result, a large group of students could simultaneously engage in learning. Forced to embrace technology due to the pandemic, participants improved their digital literacy.

Participants commended the Bangladeshi government’s shift from traditional face-to-face learning to online education as a necessity. They recognized the efficacy of online learning in the local context and found inspiration in mastering new technologies. Many educators sought to improve the effectiveness of online courses, making the most of available resources. Participants gained familiarity with technology tools and demonstrated their adaptability and commitment to mastering new skills.

A male participant said:

“An unexpected opportunity arose amidst the pandemic. Virtual learning was the need of the hour. Adapting to this sophisticated technology was initially challenging, but I eventually became comfortable with the new mode.” (M 29 )

Integration of online and offline activities

The pandemic prompted students to diversify their activities. They devoted time to hobbies such as farming, painting, gardening, and crafts. Engaging in extracurricular activities such as cooking, volunteering, attending religious events, and using social media platforms such as Facebook and Instagram became a norm. Some events created uplifting content for social media, using platforms as a potential source of income. Others embarked on online entrepreneurship ventures, reflecting their entrepreneurial spirit. Volunteering became appealing, bridging the gap between virtual and physical engagement.

Two participants shared:

“I wasn’t part of any groups during my student years. However, I joined several volunteer groups during COVID-19. These efforts included both offline initiatives such as distribution of food and masks, online initiatives.” (F 15 , M 18 )

Another participant shared:

“I had time for myself after extensive studying. I explored various creative pursuits, cooked using YouTube recipes, and found joy in them. I am considering a career in cooking.” (F 11 )

Another participant expressed:

“Amidst this time apart, many companies and organizations offer unpaid internships. I have participated in such an internship, attended seminars, conferences, workshops, and events. This period has enriched both my soft and hard skills, and I have participated in various physical and online events.” (M 22 )

The primary objective of this study was to assess the impact of COVID-19 on the academic activities of university students. The study aimed to understand students’ satisfaction with online education during the pandemic, their responses to this learning mode, and their engagement in non-academic activities. The pandemic has significantly disrupted not only regular teaching and learning at our university but also the lives of our students. Amid this outbreak, several students found solace in spending quality time with their families and tackling long-postponed household chores. It is crucial to acknowledge that a diverse range of circumstances, personalities, and coping mechanisms exist within human communities like ours. Despite these variations, the resilience exhibited by the individuals in this study stands out remarkably.

In recent research, educational institutions, particularly public universities, adopted digital online learning and assessment platforms to respond to the pandemic (Blake et al., 2021 ; Wu et al., 2020 ). Consequently, participants in our study discussed their experiences with digital platforms during COVID-19, highlighting both positive and negative impact on academic activities (see Figs. 1 – 3 ).

Our findings demonstrate that online learning offers benefits by enhancing educational flexibility through the accessibility and user-friendliness of digital platforms. These findings align with those of Kedraka and Kaltsidis ( 2020 ), who identified convenience and accessibility as primary advantages of remote learning. Moreover, Burgess and Sievertsen ( 2020 ) emphasized the potential of distance learning and technology-enabled indirect instruction, while Basilaia and Kvavadze ( 2020 ) underscored technology’s role in driving educational adaptation during a pandemic.

According to our study, the pandemic led to students’ significant loss of social connections. Collaborative group study plays a pivotal role in conceptual understanding and academic progress. However, due to the outbreak, students’ routine group study sessions in libraries or on campus, face-to-face interactions, and conversations with peers and educators suffered setbacks. These disruptions might potentially impact their motivation for sustained high-level learning. Participants voiced concerns about online learning, including the absence of human interaction, challenges in maintaining audience engagement, and, most notably, the inability to acquire practical skills. These limitations have been observed previously, indicating that these teaching and learning methods are hindered by constraints in conducting laboratory work, providing hands-on experience, and delivering comprehensive feedback to students, leading to reduced attention spans (Zawacki-Richter, 2021 ).

Likewise, Naciri et al. ( 2020 ) highlighted educators’ difficulties in sustaining student engagement, multitasking during virtual sessions, subpar audio and video quality, and connectivity issues. In our study, students reported that the quality of their internet connection directly influenced their online learning experience. They also expressed frustration at the extended screen time and feelings of fatigue. To address these concerns, experts recommended utilizing tools such as live chat, pop quizzes, virtual whiteboards, polls, and reflections to structure shorter, more interactive sessions.

Consistent with prior research, our recent poll findings suggested that participants were more surprised than disappointed by the swift decision to close educational institutions nationwide. Moreover, the study revealed that the prolonged closure of universities and confinement to homes led to substantial disruptions in students’ learning, aligning with findings from various studies that highlight disturbances in daily routines and studies (Meo et al., 2020 ), limited access to educational resources due to closed libraries, difficulties in learning at home, disruptions in the household environment, and challenges in retaining studied material (Bäuerle et al., 2020 ). All participants expressed some degree of apprehension. Staying at home exacerbated both physical and mental health issues. Study habits suffered, and interest in learning waned. Physical health concerns excessive daytime sleepiness, disrupted nocturnal sleep patterns, decreased appetite, sedentary behavior, weight gain or obesity, as well as feelings of fatigue, dizziness, and listlessness. Toquero ( 2020 ) noted similar issues, outlining the impact of COVID-19 on children’s mental health and educational performance. Delays in examinations, results, and promotions to the next academic level intensified student stress, echoing findings by Sahu ( 2020 ).

As an unintended outcome of the pandemic, online alternatives to traditional higher education have gained prominence, particularly in Bangladesh. However, these methods are not without their limitations. The study identified persistent challenges in Bangladesh’s online education system, including a lack of electronic devices such as laptops, smartphones, computers, and essential tools for online courses. Additionally, limited or absent internet access, expensive mobile data packages or broadband connections, disruptions during online classes due to slow or unstable internet speeds, and frequent power outages in both urban and rural areas hamper the efficacy of online learning. These findings echo prior research (Aldowah et al., 2019 ; Liguori and Winkler, 2020 ).

Amidst the challenges, the study also unveiled positive outcomes in academic pursuits. Students reported spending more time engaging with television, movies, YouTube videos, computer and mobile device gaming, and social networking platforms like Facebook and Instagram compared to pre-pandemic times. Some students even took a break from their studies due to university closures. They capitalized on online platforms such as Coursera, edX, and FutureLearn during their downtime at home, while others embraced hobbies like cooking and drawing. Furthermore, students actively participated in voluntary extracurricular activities, such as freelancing, unpaid internships, remote jobs, virtual conferences, seminars, webinars, workshops, and various competitions. These findings parallel those of Ali ( 2020 ), underscoring students’ varied engagement during the pandemic. In response, students proposed suggestions for enhancing educational operations, including reducing homework loads, minimizing screen time, and improving lecture delivery. Scholars like Ferrel and Ryan ( 2020 ) have recommended reducing cognitive load, enhancing engagement, implementing identity-based access, introducing case-based learning, and employing comprehensive assessments.

In conclusion, this study sheds light on the multifaceted impacts of COVID-19 on university students’ educational experiences. The pandemic prompted an accelerated shift towards digital learning, demonstrating advantages and limitations. Despite the challenges, students exhibited resilience and adaptability. As we navigate these uncharted waters, embracing the positive aspects of technology-enabled education while addressing its challenges will be pivotal for ensuring continued learning excellence.

Bangladesh boasts diverse educational institutions, ranging from colleges and universities to schools and beyond. The widespread repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic have jolted the global academic community. This study delves into how COVID-19 has influenced students’ academic performance, encompassing emotional well-being, physical health, financial circumstances, and social relationships. However, certain aspects of the curriculum, particularly science and technology-focused areas involving online lab assessments and practical courses, present challenges. Despite its adverse effects on academic activities, COVID-19 has ushered in positive outcomes for several students, revealing successful interactions with virtual education and contentment with online learning methods.

This study paves the way for further research to refine the online learning environment in Bangladeshi public universities. The findings indicate that the current strategies employed for online university teaching may lack the motivational impetus required to elevate students’ comprehension levels and actively involve them in the learning process. Consequently, there is room for conducting additional studies to enhance the online learning experience, benefiting both educators and students alike. Higher education institutions need to exert concerted efforts to establish sustainable solutions for Bangladesh’s educational challenges in the post-COVID era. A hybrid learning approach, blending online and offline components, emerges as a potentially effective strategy to navigate future situations akin to COVID-19. A collaborative effort involving governments, organizations, and educators is imperative to bridge educational gaps within this framework. Governments could play a pivotal role by providing ICT training to instructors and students, fostering a more technologically adept academic community.

This research furnishes policymakers with insights to devise strategies that mitigate the detrimental impacts of crises such as pandemics on the educational system. Notwithstanding its limitations, including a confined sample size and the sole focus on a single university within a specific country, the study contributes valuable data. This research serves as a foundation, particularly in a science and technology-focused institution where the transition to online formats is intricate due to the nature of practical courses and lab work. This information could prove invaluable to Bangladesh’s Ministry of Education as it formulates policies to counteract the adverse effects of crises on the educational realm.

Furthermore, this study serves as a springboard for subsequent investigations into the far-reaching implications of COVID-19 on academic engagement. Expanding the scope, larger-scale studies could be conducted in various locations to enrich the data pool. Additionally, considering the perspectives of professors and other stakeholders within higher education is an avenue for future exploration. Employing quantitative research methodologies with substantial sample sizes can ensure the broader applicability of the results. This study offers a multifaceted view of how COVID-19 has permeated students’ academic pursuits, opening doors for comprehensive research and proactive policy-making in education.

Data availability

The data collected from the participants in the study cannot be shared, since participants were explicitly informed during the qualitative data collection process that their information would remain confidential and not be disclosed. Participants provided consent solely for the collection of relevant data for the study.

Abidah A, Hidaayatullaah HN, Simamora RM et al. (2020) The impact of COVID-19 to Indonesian education and its relation to the philosophy of “Merdeka Belajar”. Stud Philos Sci Educ 1(1):38–49. http://scie-journal.com/index.php/SiPoSE

Article Google Scholar

Ahmed M (2020) Tertiary education during COVID-19 and beyond. The Daily Star. https://www.thedailystar.net/opinion/news/tertiary-education-during-covid-19-and-beyond-1897321

Akour A, Al-Tammemi AB, Barakat M et al. (2020) The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and emergency distance teaching on the psychological status of university teachers: a cross-sectional study in Jordan. Am J Trop Med Hygiene 103(6):2391–2399. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.20-0877

Article CAS Google Scholar

Alam GM (2021) Does online technology provide sustainable HE or aggravate diploma disease? Evidence from Bangladesh—a comparison of conditions before and during COVID-19. Technol Soc 66:101677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101677

Aldowah H, Al-Samarraie H, Ghazal S (2019) How course, contextual, and technological challenges are associated with instructors’ challenges to successfully implement e-learning: a developing country perspective. IEEE Access 7:48792–48806. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2910148

Al-Tammemi AB, Akour A, Alfalah L (2020) Is it just about physical health? An internet-based cross-sectional study exploring the psychological impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on university students in Jordan amid COVID-19 pandemic. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.562213

Ali W (2020) Online and remote learning in higher education institutes: a necessity in light of COVID-19 pandemic. Higher Educ Stud 10(3):16–25

Basilaia G, Kvavadze D (2020) Transition to online education in schools during a SARS-CoV-2 Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in Georgia. Pedagog Res 5(4):em0060. https://doi.org/10.29333/pr/7937

Bäuerle A, Skoda EM, Dörrie N et al. (2020) Correspondence psychological support in times of COVID-19: the essen community-based cope concept. J Public Health 42(3):649–650. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdaa053

Biswas B, Roy SK, Roy F (2020) Students perception of mobile learning during COVID-19 in Bangladesh: University student perspective. Aquademia 4(2):ep20023. https://doi.org/10.29333/aquademia/8443

Blake H, Knight H, Jia R et al. (2021) Students’ views towards SARS-Nov-2 mass asymptomatic testing, social distancing, and self-isolation in a university setting during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(8):4182. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/8/4182

Blumberg B, Cooper DR, Schindler PS (2005) Business research methods. McGraw-Hill, Maidenhead

Google Scholar

Burgess S, Sievertsen HH (2020) Schools, skills, and learning: the impact of COVID-19 on education. https://voxeu.org/article/impact-covid-19-education

Bytheway J (2018) Using grounded theory to explore learners’ perspectives of workplace learning. Int J Work Integrated Learn 19(3):249–259

Cao W, Fang Z, Hou G et al. (2020) The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res 287:112934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Charles NE, Strong SJ, Burns LC et al. (2020) Increased mood disorder symptoms, perceived stress, and alcohol use among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res 296:113706, https://psyarxiv.com/rge9k10.31234/osf.io/rge9k

Denscombe M (2007) The good research guide for small-scale social research projects, 3rd ed. Open University Press, Maidenhead, UK

Emon EKH, Alif AR, Islam MS (2020) Impact of COVID-19 on the institutional education system and its associated students in Bangladesh. Asian J Educ Soc Stud 11(2):34–46. https://doi.org/10.9734/ajess/2020/v11i230288

Farris SR, Grazzi L, Holley M (2021) Online mindfulness may target psychological distress and mental health during COVID-19. Glob Adv Health Med. https://doi.org/10.1177/21649561211002461

Ferrel MN, Ryan JJ (2020) The impact of COVID-19 on medical education. Cureus 12(3):e7492. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.7492

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Institute of Epidemiology, Disease Control and Research (IEDCR) (2020) COVID-19 vital statistics. IEDCR, Dhaka. https://iedcr.gov.bd

Jacob ON, Abigeal I, Lydia AE (2020) Impact of COVID-19 on the higher institutions development in Nigeria. Electron Res J Soc Sci Humanit 2:126–135. http://www.eresearchjournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/0.-Impact-of-COVID.pdf

Kedraka K, Kaltsidis C (2020) Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on university pedagogy: students’ experiences and consideration. Eur J Educ Stud 7(8):3176. https://doi.org/10.46827/ejes.v7i8.3176

Khan MSH, Abdou BO (2021) Flipped classroom: how higher education institutions (HEIs) of Bangladesh could move forward during COVID-19 pandemic. Soc Sci Humanit Open 4(1):100187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2021.100187

Liguori E, Winkler C (2020) From offline to online: challenges and opportunities for entrepreneurship education following the COVID-19 pandemic. Entrep Educ Pedagogy 3(4):346–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515127420916738

Meo SA, Abukhalaf AA, Alomar AA et al. (2020) COVID-19 pandemic: impact of quarantine on medical students’ mental wellbeing and learning behaviors. Pakistan J Med Sci 36(COVID19-S4):S43–S48. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.36.COVID19-S4.2809

Naciri A, Baba MA, Achbani A et al. (2020) Mobile learning in higher education: unavoidable alternative during COVID-19. Academia 4(1):ep20016. https://doi.org/10.29333/aquademia/8227

Neuwirth LS, Jović S, Mukherji BR (2021) Reimagining higher education during and post-COVID-19: challenges and opportunities. J Adult Continuing Educ 27(2):141–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477971420947738

Owusu-Fordjour C, Koomson CK, Hanson D (2020) The impact of COVID-19 on the learning-the perspective of the Ghanaian student. Eur J Educ Stud. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3753586

Rajhans V, Memon U, Patil V et al. (2020) Impact of COVID-19 on academic activities and way forward in Indian Optometry. J Optom 13(4):216–226. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1888429620300558

Rameez A, Fowsar MAM, Lumna N (2020) Impact of COVID-19 on higher education sectors in Sri Lanka: a study based on the South Eastern University of Sri Lanka. J Educ Soc Res 10(6):341–349. http://192.248.66.13/bitstream/123456789/5076/1/12279-Article%20Text-44384-1-10-20201118.pdf

Sahu P (2020) Closure of universities due to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): impact on education and mental health of students and academic staff. Cureus 12(4):e7541. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.7541

Shrestha S, Haque S, Dawadi S et al. (2022) Preparations for and practices of online education during the COVID-19 pandemic: a study of Bangladesh and Nepal. Educ Inf Technol 27(1):243–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10659-0

Stanistreet P, Elfert M, Atchoarena D (2020) Education in the age of COVID-19: understanding the consequences. Int Rev Educ 66(5–6):627–633. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-020-09880-9

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Toquero CM (2020) Challenges and opportunities for higher education amid the COVID-19 pandemic: yhe Philippine context. Pedagog Res 5(4):em0063. https://doi.org/10.29333/pr/7947

UNESCO (2020a) Adverse consequences of school closures. https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse/consequences

UNESCO (2020b) Education: from disruption to recovery. https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse

World Health Organization (WHO) (2020) Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) situation report-1. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronavirus/situationreports/20200121-sitrep-1-2019-ncov.pdf?sfvrsn=20a99c10_4

Wu Y, Xu X, Chen Z et al. (2020) Nervous system involvement after infection with COVID-19 and other coronaviruses. Brain Behav Immun 87:18–22. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1603.091216

Zawacki-Richter O (2021) The current state and impact of COVID-19 on digital higher education in Germany. Hum Behav Emerg Technol 3(1):218–226. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.238

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Sociology, Shahjalal University of Science and Technology, Sylhet, 3114, Bangladesh

Bijoya Saha & Shah Md Atiqul Haq

The Institute for the Study of International Migration (ISIM), Walsh School of Foreign Service, Georgetown University, 3700 O Street NW, Washington, DC, 20057, USA

Khandaker Jafor Ahmed

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Shah Md Atiqul Haq .

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval.

At the time the study was undertaken, there was no official ethics committee. Since it is crucial that ethical reviews occur before the start of every research, retrospective approval for completed studies like this study is not practicable. To ensure the safety of participants and the validity of the study, the research, nevertheless, complies with accepted ethical standards. Potential conflicts of interest were handled openly, and data management protocols respected anonymity.

Informed consent

Before engaging in the study, participants were informed about the objectives of the study by the interviewer. Furthermore, they were assured that any data they contributed would remain confidential and exclusively used only for the study. Transparency was emphasized in conveying that the study’s results and findings would be disseminated in a published format. As a critical component of ethical research practice, participants were requested to give their informed consent prior to their active involvement in the study.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Saha, B., Atiqul Haq, S.M. & Ahmed, K.J. How does the COVID-19 pandemic influence students’ academic activities? An explorative study in a public university in Bangladesh. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10 , 602 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02094-y

Download citation

Received : 20 October 2022

Accepted : 06 September 2023

Published : 22 September 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02094-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Article Writing

- Article On Covid 19

Article on COVID-19

COVID-19 or Coronavirus is a term the world has been uttering for almost two years now. The coronavirus disease is an infectious disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 virus. Since the birth of the pandemic, the world has shifted to a new normal where masks are the new accessory and sanitisers are used like sunscreens. There is a lot of information out there about the pandemic, but when you are asked to write an article on COVID-19, do not just pick information at random; instead, try to gather details that would explain the dawn of the virus, the harmful effects and the precautionary measures to be taken to keep one safe and secure.

To know more about the virus and for sample articles, go through the topics given below:

- Article On COVID-19 – Symptoms And Precautions

- Short Article On COVID-19

- FAQs On COVID-19

Article on COVID-19 – Symptoms and Precautions

The effects of the virus are different from person to person. For most people, it starts with a common cold and fever that develops into serious respiratory problems, fatigue, soreness and loss of taste and smell. The virus has developed into a lot of variants, and each one becomes even more severe with the onset of a new variant.

The spread of the virus takes place when an individual comes into contact with an infected person. It spreads from the person’s nose or mouth when they sneeze, yawn, cough, breathe, speak or sing. We have been taught respiratory etiquette, covering our mouth and nose when coughing or sneezing and isolating ourselves when we are unwell. These are the same rules that apply to keep ourselves and others from being infected by the virus.

People affected by coronavirus show a range of symptoms from mild to severe conditions. The symptoms include cold, cough, fever, soreness, fatigue, difficulty in breathing, loss of taste and smell. These symptoms start appearing from 2-14 days after the individual has been exposed to the virus. Make sure that you get yourself tested the moment you witness any of these symptoms to prevent it from getting any worse.

Precautions

To keep yourself from being affected by coronavirus, see to that you

- Wear your masks covering your nose and mouth every time you step out of your house

- Wash your hands thoroughly

- Sanitise yourself

- Avoid eating or drinking anything cold

- Eat nutritious food to build immunity

- Maintain a physical distance when you are in contact with a group of people

- Avoid all sorts of direct physical contact

Taking care of yourself means taking care of others too. If each one is conscious about the complications this disease can bring into their lives, it would be a lot easier to curb the spread of the virus. Be cautious. Create awareness. Stay safe.

Short Article on COVID-19

Research has shown that the outbreak of COVID-19 was in December 2019, and from then, there have been more than 600 million people who were infected with the virus and around 6.5 million deaths all around the world, according to WHO reports, as of September 30, 2022. The daily reports of people being infected and people dying have been going up, and down and the numbers vary from country to country.

Every country has been following different procedures and doing all that is possible to stop the spread of COVID-19. It is, however, dependent on the individuals. It is in our best interest that the authorities are laying out rules and regulations, and it is our responsibility to follow them and keep ourselves hygienic, which in turn will keep everyone around us safe too.

Researchers and medical practitioners have worked really hard to develop vaccines for COVID-19. COVID-19 vaccines, like any other vaccine, have side effects like fever, soreness and weakness. Many people have already been vaccinated. However, it is good to remember that being vaccinated is not the license to roam around without wearing masks and making close contact with people you meet. New variants of the virus have been evolving every now and then, and the seriousness of the disease is becoming worse with every variant. Only with collective efforts can we stop the spread of the disease.

FAQs on COVID-19

What is covid-19.

COVID-19 is an infectious disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 virus. The symptoms of the disease vary from individual to individual ranging from mild symptoms like cold and fever to severe symptoms including shortness of breath, chest pain, loss of speech or mobility and even death.

What are the organs most affected by coronavirus?

According to researchers, the organs that are most affected by the virus are the lungs.

What are the possible complications post COVID-19?

People seem to continue experiencing difficulty in breathing, soreness, fatigue, etc., even after recovering from COVID-19.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request OTP on Voice Call

Post My Comment

- Share Share

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

Academic writing and ChatGPT: Students transitioning into college in the shadow of the COVID-19 pandemic

- Perspective

- Open access

- Published: 10 January 2024

- Volume 3 , article number 6 , ( 2024 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Daniela Fontenelle-Tereshchuk ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1632-108X 1

3443 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This paper reflects on an educator's perceived experiences and observations on the complex process of ‘passage’ when students transitioning from high school into their first-year of post-secondary education often struggle to adapt to academic writing standards. It relies on literature to further explore such a process. Written communication has become increasingly popular in formal academic and professional settings, stressing the need for effective formal writing skills. The development of online tools for aiding writing is not a new concept, but a new software development known as ChatGPT, may add to the many challenges academic writing has faced over the years. This paper reflects on the students' struggles as they navigate different courses seeking to adapt their writing skills to formal and structured written academic requirements. The COVID-19 pandemic forced many recent high school students into virtual education, uncertain of its effectiveness in developing the writing skills high school graduates require in academia. Many unknowns exist in using ChatGPT in academic contexts, especially in writing. ChatGPT can generate texts independently, raising concerns about plagiarism and its impact on students' critical thinking and writing skills. This paper hopes to contribute to pedagogical discussions on the current challenges surrounding the use of artificial intelligence technology and how better to support beginner writers in academia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Students’ voices on generative AI: perceptions, benefits, and challenges in higher education

Artificial Intelligence (AI) Student Assistants in the Classroom: Designing Chatbots to Support Student Success

Examining science education in chatgpt: an exploratory study of generative artificial intelligence.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The COVID-19 crisis highlighted an old problem for most students transitioning from high school into college, the deficiencies in structural and critical analytical writing and reading skills in relation to what is expected of these students in the different courses at the college level [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. This first-year of college is like a ceremony of ‘passage’ into the adulthood of education and the premise of a potentially successful academic and professional life. Students often navigate this new learning environment unaware of the many layers of complexities involved in writing at the academic level.

This paper mainly focuses on three important educational considerations:

Noticeable deficiencies in writing skills preparation among high school graduates as a consequence of systemic challenges in high school curricula and grading policies [ 1 , 2 , 3 ].

The accentuation of education such challenges during the COVID-19 crisis and its pressures on pedagogy, assessment, and mental health at the high school and higher institution levels [ 4 , 5 ].

The popularization of a generative AI illusion of written communications made ‘easy and competence-free’ as a ‘solution’ or ‘fix’ for one’s struggles to adapt their already deficient foundational writing skills to meet the standards and expectations of academic papers across the disciplines [ 6 ]. This has led to further challenges in instructional and assessment strategies as well as policies regulating the use of AI technology in education.

Since the COVID-19 crisis started, writing has taken a new role in communication, as in-person interactions were not always possible due to lockdowns. Academically and professionally, emailing and sharing knowledge through a written format were further popularized during this period. For students transitioning from high school into post-secondary educational institutions, the academic writing challenges were accentuated due to academic losses, and unstable learning environments, sometimes online and other times in-person or alternating depending on lockdowns due to the number of COVID-19 infections affecting students’ mental health and learning. Advances in technology have been available in the educational context, especially writing tools such as editing software, which are easily found. For instance, Microsoft Word and Grammarly are used widely as editing tools. Microsoft WORD, as well as Grammarly, have been evolving their capabilities, offering students autocorrection suggestions, including how to re-write complete paragraphs, but mainly flagging potential grammar mistakes. These editing tools may help students improve their paper drafts but in a more limited manner compared to other technological tools available online. Generative Artificial Intelligence—AI software such as ChatGPT, due to its ability to create original but derivative text, has raised concerns about plagiarism, academic conduct, and the process of learning and becoming proficient in formal writing styles such as academic writing.

This paper discusses the struggles of junior college students as they navigate different courses seeking to adapt their often-deficient academic writing skills to a more formal and structured form of writing standard to most post-secondary institutions’ paper writing style. It explores these challenges in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and the popularization of writing platforms using Artificial Intelligence—AI such as ChatGPT. The topic is relevant as educators strive to address the potential impact of the pandemic legacy. The paper focuses on the potential deterioration of pre-existing academic deficiencies, a decline in mental health as well as the role of technology in academic writing, especially looking at ChatGPT’s potential impact on first-year college student writing. It may also contribute to pedagogical discussions on the current challenges surrounding the use of artificial intelligence technology and how better to support beginner student writers in an academic context.

2 Literature review

Canada is a diverse country. Such human diversity is often found in classrooms composed of students from many cultures, languages, and socioeconomic backgrounds, leading to a wide range of learning needs and challenges impacting education [ 7 ]. Some studies suggest that high school Province Diploma Examination outcomes do not always translate into an acute picture of students’ literacy skills, as many first-year college students who obtained good results in the Alberta diploma exam may struggle to meet the standards of academic writing required at the university level [ 8 , 9 ]. They point to the need for better literacy practices in high school to support students transitioning from high school to university, especially English Language Learners.

As shown in the 2018 PISA results [ 10 ], overall literacy skills among Alberta students also suggest a decline in reading and, consequently, in writing abilities among high school students in recent years [ 11 ]. The root of the academic writing struggles often observed among first-year post-secondary students may be unclear. Still, the COVID-19 pandemic may have worsened these students’ ability to adapt or develop the academic writing skills needed in an academic setting. According to Aurini and Davies [ 12 ], “lengthy periods of time out of school generally create losses of literacy and numeracy skills and widen student achievement gaps” [p. 165]. For instance, the National Assessment of Educational Progress—NAEP [ 5 ] suggests that students who were already academically struggling were most likely affected by the pandemic, and academic deficiencies became more accentuated, especially among visible minorities.

The coronavirus crisis has impacted the higher education community and learning settings [ 13 , 14 ]. Hawley et al. [ 15 ] explain that “to ensure student health and abide by governmental recommendations, universities worldwide have mostly transitioned to online teaching” impacting academic calendars, and students’ daily educational routine and learning experiences [p. 13]. Online courses have been available to college students for years, but the virtual learning approach experienced by students and educators during COVID-19 university lockdowns led to further testing of the limitations of home learning [ 13 ]. This process is characterized by the use of virtual platforms as learning tools. These learning tools were important to facilitate learning during school lockdowns. The virtual learning experiences during this period may have also broadened our understanding of how these learning tools can be used and how effective they are [ 4 ].

Many studies point to first-year college students' challenges transitioning from high school into college, adapting high school-level writing skills into much more refined and structured standardized practices required in college-level papers [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. Academic deficiencies were further accentuated during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially for the students who were already struggling with academic shortcomings prior to the coronavirus pandemic [ 5 ].

In addition, a survey conducted by the Office of National Statistics in the United Kingdom suggests that most higher education students were dissatisfied with their learning experience during the COVID-19 crisis lockdowns [ 14 ]. The survey results indicate two major concerns for these students: Learning delivery (75%) and quality of learning (71%). They suggest that the lack of opportunities for social interactions and face-to-face learning experiences impacted the students’ learning experiences. They may have also contributed to accentuating mental health issues, often leading to depression and academic loss. These factors add to other mental health stressors first-year post-secondary students may already face, such as “social relationships, loneliness, academic demands, and finances” [ 16 , p. 885]. Duffy et al. [ 16 ] suggest increasing demands for mental health support among novice students.

Another study, based on an online survey performed between April 29 and May 31, 2020, which included students from the United States, Ireland, Malaysia, the Netherlands, China, Taiwan and South Korea points to university students’ concerns “about the quality of online learning, progress with their education, and maintaining interaction with peers and professors” [16, p. 4]. Interestingly, the study suggests that students shared similar concerns regarding academic progression and interactions prior to the pandemic. It also notes that mental health concerns were mostly higher among American students compared to other students surveyed.

Academic writing deficiencies and educational inequalities among first-year college students have been a complex problem over the years, especially in Canada and the United States [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 17 ]. Some scholars point to grade inflation in high schools that ultimately may grant students a Grade Point Average—GPA high enough to enter most programs at the university level but does not correspond to the writing skills needed to carry on more advanced analytical writing skills required at the university level [ 18 , 19 ]. For instance, Cosh [ 20 ] argues that in Ontario, high school grades trended up over the years, but during the COVID-19 pandemic, they climbed substantially compared to previous years. He suggests two main reasons for the sudden increase in high school students’ grades:

First, inadequate government grading policy may not clearly and accurately portray learning outcomes. The author explains that in an attempt to address any shortfall from the pandemic, the Ontario Ministry of Education issued a directive that high school students’ grades should not be lower than they were before the pandemic.

Secondly, grade inflation during the challenging times of the pandemic, where teachers may have prioritized students’ well-being over academics, believing that higher grades could contribute to students’ resilience and sense of optimism amid such a challenging time.

Cosh [ 20 ] concludes that while grade inflation may have benefited many academically struggling students to enter specific postsecondary programs, it might have been detrimental to truly high-achiever students. He explains that as most students averaged 90 percent, such grades became meaningless and kept some of these students whose academic merits matched their grades out of their desired postsecondary programs. I would add that another potential problem with grade inflation is student retention, widening the struggles in subjects such as academic writing, which may impact student dropout rates and increase student debt without the prospect of finishing a degree.

Graff [ 1 ] explores the many problems within the problem faced by students transitioning from high school into college. He suggests that such problems are complex and have many ramifications, from the failure of high schools to offer these students proper opportunities to develop their academic writing skills to the inability of higher institutions to effectively bridge this ‘passage’ stage in students’ academic journey. According to Birenbaum et al. [ 21 ], “current context of accountability of Canadian public schools, assessment for learning policies and protocols are beginning to emerge in an effort to support teacher practice in this area” [p. 123], suggesting that some teachers may lack the skills to assess students in a way that grades reflect the student’s knowledge of writing.

Research also points to high education potential stigmas towards teaching how to write at the university level such as the belief that novice university students will eventually learn how to write, perhaps justifying the minor emphasis on writing courses compared to other disciplines [ 2 , 3 , 13 , 22 ]. Gómez-García et al. [ 13 ] explain that even though some institutions offer academic writing classes, often these courses are taught by contract staff. Some faculty staff occasionally refer to them in a depreciative tone as ‘grammar’ courses, suggesting that anybody can teach them and it is not higher in priority for most tenured faculty [ 13 ]. More than generalizing the students’ writing ability needs, Wilder and Yagelski [ 3 ] argue that students are all at different writing levels. They note that the number of courses institutions often offer students is insufficient to address the student's needs to develop their academic reading and writing analytical skills required to succeed in academic writing. The authors also suggest a correlation between students' academic writing skill level and their grades. That is to say, students with more developed analytical writing abilities often receive higher grades.

Volante and DeLuca [ 19 ] point to grade inflation as another potential contributor to novice postsecondary students' challenges due to “the fact that some students, presumably from high schools with more generous grading, have a false sense of their academic ability which may lead to a rude awakening at university” [p. 1]. It likely adds to the frustrations and sometimes the discontent among some junior college students about taking academic writing courses, as one may assume students already have the required writing skills based on their high school grades. It may also contribute to some myths, such as students’ popular belief that ‘guessing’ what the professor wants them to write will lead to higher grades or if the professor’s ‘dislike’ for a student will result in low grades at the university level.

In the mists of the pandemic, which has impacted students’ and contributed to grade inflation, aggravating the challenges for first-year college students writing; ChatGPT—an AI tool that can be used to produce texts, increasingly started to become part of class conversations as students, as well as educators, are often curious to see how it works and the potential benefits and challenges to education [ 6 , 23 ]. While some students may find the use of AI in writing as a possible solution to the knowledge gap between high school and college expected writing skills, educators are often concerned the overreliance on technology would be detrimental to actual learning, and add to the difficulties students may have to adjust to more permanent in-person learning.

Dobrin [ 6 ] defines AI as the “theory and development of computer systems that can perform tasks that previously required human intelligence” [p. 4]. The author argues that, like human abilities, these systems learn from performing various tasks, adapting and improving to become more efficient over time. However, unlike humans, these systems lack a critical understanding of discerning information accuracy. Dobrin [ 6 ] also points to how introducing such systems may change how we perceive plagiarism. Ultimately, the popularization of AI for academic writing purposes is complex and problematic, and it might be connected to a vacuum in responsive practices addressing the challenges students have experienced transitioning from high school into university over the years. Namely, high schools and postsecondary educational institutions may be failing to provide students with meaningful opportunities to develop and grow their writing abilities, an essential skill in academic and professional success prospects.

3 Discussion: Reflections of an educator

3.1 academic losses and managing learning from home.

I was teaching high school when classes started transitioning from in-person to virtual classes due to the first COVID-19 school lockdown. At that point, many high school students were already struggling with writing and often not writing at grade level. Reflecting on the transition of high school students into a postsecondary setting, the researcher in me wants to know: Are academic writing skills any different for English language learners compared to English native speakers?