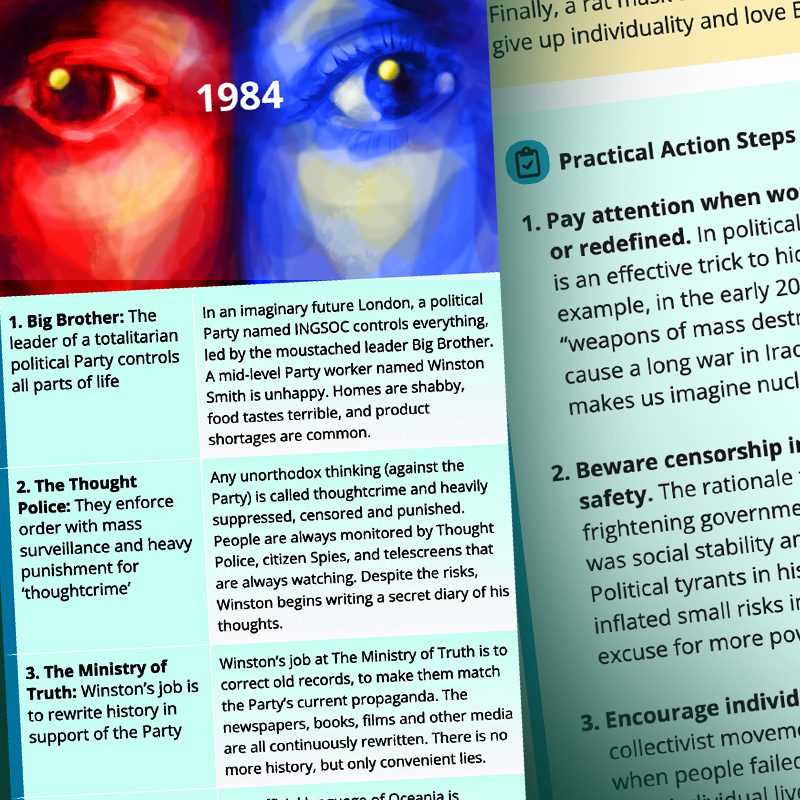

Thinking, Fast and Slow

Daniel kahneman, ask litcharts ai: the answer to your questions.

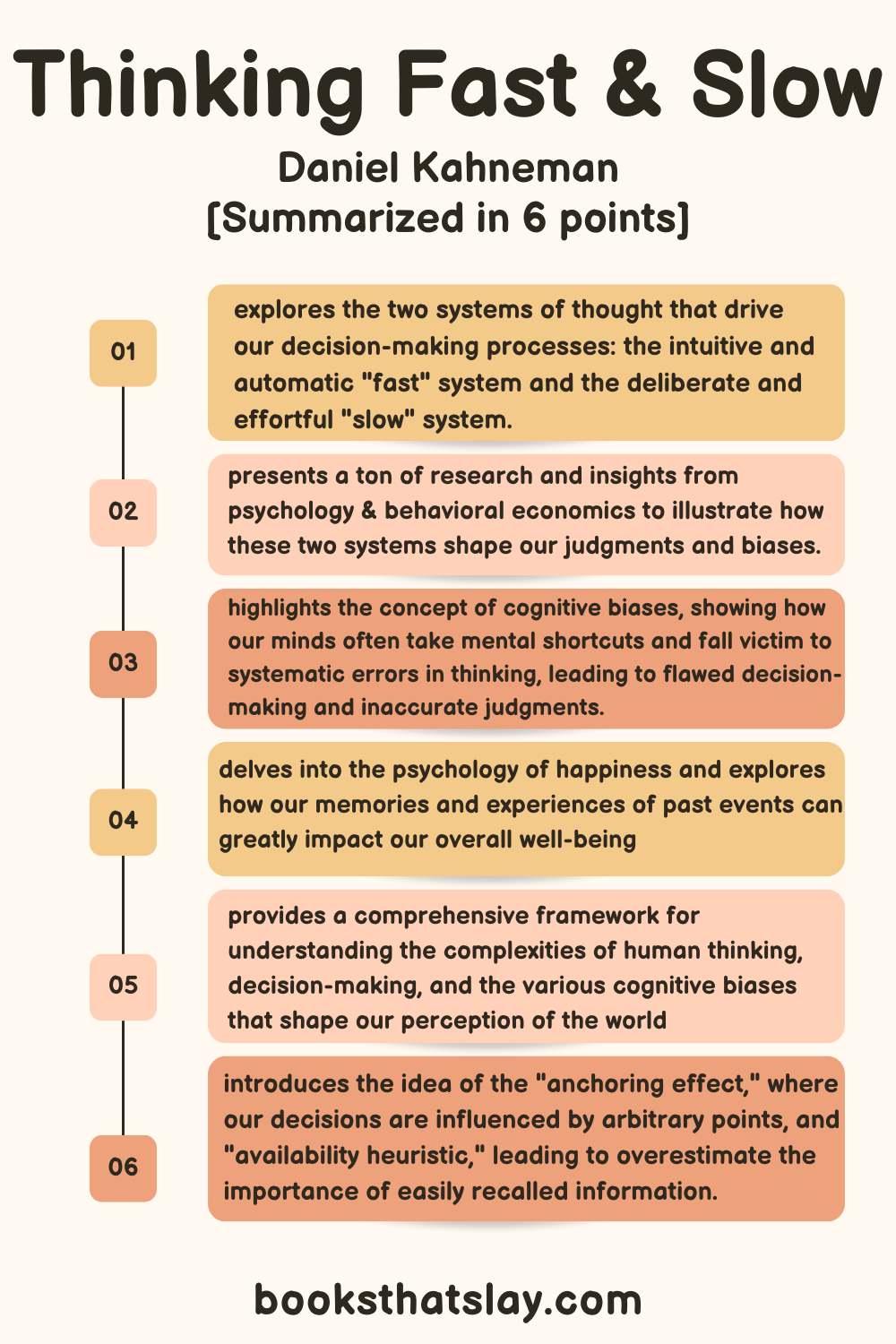

Daniel Kahneman begins by laying out his idea of the two major cognitive systems that comprise the brain, which he calls System 1 and System 2. System 1 operates automatically, intuitively, and involuntarily. We use it to calculate simple math problems, read simple sentences, or recognize objects as belonging to a category. System 2 is responsible for thoughts and actions that require attention and deliberation: solving problems, reasoning, and concentrating. System 2 requires more effort, and thus we tend to be lazy and rely on System 1. But this causes errors, particularly because System 1 has biases and can be easily affected by various environmental stimuli (called priming).

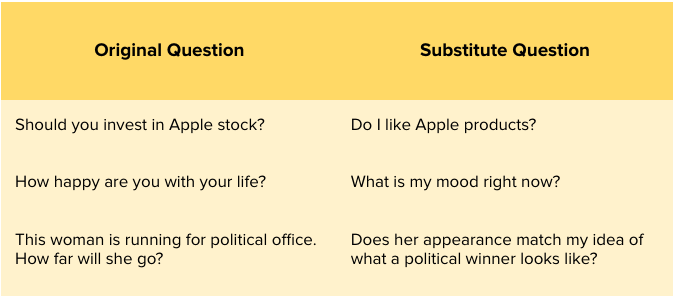

Kahneman elaborates on System 1’s biases: sentences that are easier to compute and more familiar seem truer than sentences that require additional thought (a feeling called cognitive ease). System 1 also tends to search for examples that confirm our previously held beliefs (the confirmation bias). This in turn causes us to like (or dislike) everything about a person, place or thing (the halo effect). System 1 also causes us to substitute easier questions for hard ones, like “What is my mood right now?” for the question “How happy am I these days?”

The second part of the book focuses on biases in calculations. Our brains have a difficult time with statistics, and we often don’t understand that small samples are inherently more extreme than large samples. This leads us to make decisions on insufficient data. Our brains also have the tendency to construct stories about statistical data, even if there is no true cause to explain certain statistical information.

If we are asked to estimate a number and are given a number to anchor us (like asking if Gandhi was over 35 when he died, and then asking how old Gandhi was when he died), that anchor will have a large effect on our estimation. If asked to estimate the frequency of a thing or event (like people who divorce over the age of 60), it is rare that we will try to calculate the basic statistical rate and instead we will overestimate if we can think of vivid examples of that thing, or have personal experience with that thing or event.

We overlook statistics in other ways: if we are given descriptions about a fictional person who fits the stereotype of a computer science student (Kahneman names him Tom W), we will overestimate the probability that he actually belongs to that group, as the number of computer science students is actually quite small relative to other fields. In the same vein, if a fictional person fits the stereotype of a feminist (Kahneman calls her Linda), people will be more likely to say that she is a feminist bank teller than just a bank teller—despite the fact that this violates the logic of probability because every feminist bank teller is, by default, a bank teller.

When trying to make predictions, we often overestimate the role of qualities like talent, stupidity, and intention, and underestimate the role of luck and randomness—like the fact that a golfer who has a good first day in a tournament is statistically likely to have a worse second day in the tournament, and no other causal explanation is necessary. In this continuous attempt to make more coherent sense of the world, we also create flawed explanations of the past and believe that we understand the future to a greater degree than we actually do. We have a tendency to overestimate our predictive abilities in hindsight, called the hindsight illusion.

Kahneman next focuses on overconfidence: that we sometimes confidently believe our intuitions, predictions, and point of view are valid even in the face of evidence that those predictions are completely useless. Kahneman gives an example in which he and a peer observed group exercises with soldiers and tried to identify good candidates for officer training. Despite the fact that their forecasts proved to be completely inaccurate, they did not change their forecasting methods or behavior. People also often overlook statistical information in favor of gut feelings, but it is more important to rely on checklists, statistics, and numerical records over subjective feelings. An example of this can be found in the development of the Apgar tests in delivery rooms. This helped standardize assessments of newborn infants to identify which babies might be in distress, and greatly reduced infant mortality.

Kahneman spends a good deal of time discrediting people like financial analysts and newscasters, whom he believes are treated like experts even though, statistically, they have no demonstrable predictive skills. He works with Gary Klein to identify when “expert” intuition can be trusted, and discovers that some environments lend themselves to developing expertise. To develop expertise, people must be exposed to environments that are sufficiently regular so as to be predictable, and must have the opportunity to learn these regularities through practice. Firefighters and chess masters are good examples of true experts.

Kahneman elaborates on other ways in which we are overconfident: we often take on risky projects because we assume the best-case scenario for ourselves. We are ignorant of others’ failures and believe that we will fare better than other people when we consider ventures like starting small businesses, or as Kahneman himself experienced, designing curricula.

Kahneman then moves on to writing about the theory he and Amos Tversky developed, called prospect theory. He first introduces Daniel Bernoulli ’s utility theory, which argues that money’s value is not strictly fixed: $10 dollars means the same thing to someone with $100 as $100 has to someone with $1,000. But Kahneman highlights a flaw in Bernoulli’s theory: it does not consider a person’s reference point. If one person had $1 million yesterday and another had $9 million, and today they both have $4 million, they are not equally happy—their wealth does not have the same utility to each of them.

Prospect theory has three distinct features from utility theory: 1) Prospects are considered with regard to a reference point—a person’s current state of wealth. 2) A principle of diminishing sensitivity applies to wealth—the difference between $900 and $1,000 is smaller than the difference between $100 and $200. 3) Losses loom larger than gains: in a gamble in which we have equal chances to win $150 or lose $100, most people do not take the gamble because they fear losing more than they want to win. Loss aversion applies to goods as well—the endowment effect demonstrates that a good is worth more to us when we own it because it is more painful to lose the good than it is pleasant to gain the good.

Standard economic theory holds that people are rational, and will weigh the outcomes of a decision in accordance with the probabilities of those outcomes. But prospect theory demonstrates that sometimes people do not weigh outcomes strictly by probability. For example, in a scenario in which people have 95% chance to win $10,000, people overweight the probability that they may not win the money. They become risk averse, and will often take a smaller, guaranteed amount. If there is a 5% chance of winning $10,000, people overweight the probability of winning and hope for a large gain (this explains why people buy lottery tickets).

Prospect theory explains why we overestimate the likelihood of rare events, and also why in certain scenarios we become so risk-averse that we avoid all gambles, even though not all gambles are bad. Our loss aversion also explains certain biases we have: we hesitate to cut our losses, and so we often double down on the money or resources that we have invested in a project, despite the fact that that money might be better spent on something else.

Our brains can lack rationality in other ways: for instance, we sometimes make decisions differently when we consider two scenarios in isolation versus if we consider them together. For example, people will on average contribute more to an environmental cause that aids dolphins than a fund that helps farmers get check-ups for skin cancer if the two scenarios are presented separately. But when viewed together, people will contribute more to the farmers because they generally value humans more than animals.

How a problem is framed can also affect our decisions: we are more likely to undergo surgery if it has a one month survival rate of 90% than if the outcome is framed as a 10% mortality rate. Frames are difficult to combat because we are not often presented with the alternative frame, and thus we often don’t realize how the frame we see affects our decisions.

Kahneman also worked on studies that evaluated measures of happiness and experiences. He found that we have an experiencing self and a remembering self, and that often the remembering self determines our actions more than the experiencing self. For example, how an experience ends seems to hold greater weight in our mind than the full experience. We also ignore the duration of experiences in favor of the memory of how painful or pleasurable something was. This causes us to evaluate our lives in ways that prioritize our global memories rather than the day-to-day experience of living.

Kahneman concludes by arguing for the importance of understanding the biases of our minds, so that we can recognize situations in which we are likely to make mistakes and mobilize more mental effort to avoid them.

Thinking Fast and Slow Summary

1-Sentence-Summary: Thinking Fast and Slow shows you how two systems in your brain are constantly fighting over control of your behavior and actions, and teaches you the many ways in which this leads to errors in memory, judgment and decisions, and what you can do about it.

Favorite quote from the author:

Table of Contents

Video Summary

Free audio & pdf summary, thinking fast and slow review, who would i recommend our thinking fast and slow summary to.

Say what you will, they don’t hand out the Nobel prize for economics like it’s a slice of pizza. Ergo, when Daniel Kahneman does something, it’s worth paying attention to.

His 2011 book, Thinking Fast and Slow , deals with the two systems in our brain, whose fighting over who’s in charge makes us prone to errors and false decisions.

It shows you where you can and can’t trust your gut feeling and how to act more mindfully and make better decisions.

Here are 3 good lessons to know what’s going on up there:

- Your behavior is determined by 2 systems in your mind – one conscious and the other automatic.

- Your brain is lazy and thus keeps you from using the full power of your intelligence.

- When you’re making decisions about money, leave your emotions at home.

Want to school your brain? Let’s take a field trip through the mind!

Want a Free Audio & PDF of This Summary?

Studies have shown that multimedia learning leads to quicker comprehension, better memory, and higher levels of achievement. Get the free audio and PDF version of this summary, and learn more faster, whenever and wherever you want!

Click the button below, enter your email, and we’ll send you both the audio and PDF version of this book summary, completely free of charge!

Lesson 1: Your behavior is determined by 2 systems in your mind – one conscious and the other automatic.

Kahneman labels the 2 systems in your mind as follows.

System 1 is automatic and impulsive .

It’s the system you use when someone sketchy enters the train and you instinctively turn towards the door and what makes you eat the entire bag of chips in front of the TV when you just wanted to have a small bowl.

System 1 is a remnant from our past, and it’s crucial to our survival. Not having to think before jumping away from a car when it honks at you is quite useful, don’t you think?

System 2 is very conscious, aware and considerate .

It helps you exert self-control and deliberately focus your attention. This system is at work when you’re meeting a friend and trying to spot them in a huge crowd of people, as it helps you recall how they look and filter out all these other people.

System 2 is one of the most ‘recent’ additions to our brain and only a few thousand years old. It’s what helps us succeed in today’s world, where our priorities have shifted from getting food and shelter to earning money, supporting a family and making many complex decisions.

However, these 2 systems don’t just perfectly alternate or work together. They often fight over who’s in charge and this conflict determines how you act and behave.

Lesson 2: Your brain is lazy and causes you to make intellectual errors.

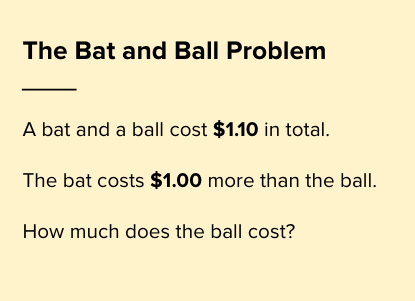

Here’s an easy trick to show you how this conflict of 2 systems affects you, it’s called the bat and ball problem.

A baseball bat and a ball cost $1.10. The bat costs $1 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?

I’ll give you a second.

If your instant and initial answer is $0.10, I’m sorry to tell you that system 1 just tricked you.

Do the math again.

Once you spent a minute or two actually thinking about it, you’ll see that the ball must cost $0.05. Then, if the bat costs $1 more, it comes out to $1.05, which, combined, gives you $1.10.

Fascinating, right? What happened here?

When system 1 faces a tough problem it can’t solve, it’ll call system 2 into action to work out the details.

But sometimes your brain perceives problems as simpler as they actually are. System 1 thinks it can handle it, even though it actually can’t, and you end up making a mistake .

Why does your brain do this? Just as with habits, it wants to save energy . The law of least effort states that your brain uses the minimum amount of energy for each task it can get away with.

So when it seems system 1 can handle things, it won’t activate system 2. In this case, though, it leads you to not use all of your IQ points, even though you’d actually need to, so our brain limits our intelligence by being lazy.

Lesson 3: When you’re making decisions about money, leave your emotions at home.

Even though Milton Friedman’s research about economics built the foundation of today’s work in the field, eventually we came to grips with the fact that the homo oeconomicus , the man (or woman) who only acts based on rational thinking, first introduced by John Stuart Mill , doesn’t quite resemble us.

Imagine these 2 scenarios:

- You’re given $1,000. Then you have the choice between receiving another, fixed $500, or taking a 50% gamble to win another $1,000.

- You’re given $2,000. Then you have the choice between losing $500, fixed, or taking a gamble with a 50% chance of losing another $1,000.

Which choice would you make for each one?

If you’re like most people, you would rather take the safe $500 in scenario 1, but the gamble in scenario 2. Yet the odds of ending up at $1,000, $1,500 or $2,000 are the exact same in both.

The reason has to do with loss aversion. We’re a lot more afraid to lose what we already have, as we are keen on getting more .

We also perceive value based on reference points. Starting at $2,000 makes you think you’re in a better starting position, which you want to protect.

Lastly, we get less sensitive about money (called diminishing sensitivity principle ), the more we have. The loss of $500 when you have $2,000 seems smaller than the gain of $500 when you only have $1,000, so you’re more likely to take a chance.

Be aware of these things. Just knowing your emotions try to confuse you when it’s time to talk money will help you make better decisions. Try to consider statistics, probability and when the odds are in your favor, act accordingly.

Don’t let emotions get in the way where they have no business. After all, rule number 1 for any good poker player is “Leave your emotions at home.”

Want the audio and PDF version of this summary, free of charge? Click below, enter your email, and we’ll send you both right away!

Download Audio & PDF

Kahneman’s thinking in Thinking Fast and Slow reminds a bit of Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s Antifragile . Very scientific, all backed up with math and facts, yet simple to understand. I highly recommend this book!

The 17 year old with an interest in biology and neuroscience, the 67 year old retiree with a secret passion for gambling, and anyone who’s bad at mental math.

Last Updated on May 3, 2024

Niklas Göke

Niklas Göke is an author and writer whose work has attracted tens of millions of readers to date. He is also the founder and CEO of Four Minute Books, a collection of over 1,000 free book summaries teaching readers 3 valuable lessons in just 4 minutes each. Born and raised in Germany, Nik also holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Business Administration & Engineering from KIT Karlsruhe and a Master’s Degree in Management & Technology from the Technical University of Munich. He lives in Munich and enjoys a great slice of salami pizza almost as much as reading — or writing — the next book — or book summary, of course!

*Four Minute Books participates in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising commissions by linking to Amazon. We also participate in other affiliate programs, such as Blinkist, MindValley, Audible, Audiobooks, Reading.FM, and others. Our referral links allow us to earn commissions (at no extra cost to you) and keep the site running. Thank you for your support.

Need some inspiration? 👀 Here are... The 365 Most Famous Quotes of All Time »

Share on mastodon.

This bestselling self-help book vastly improved my decision-making skills — and helped me spot my own confirmation bias

When you buy through our links, Business Insider may earn an affiliate commission. Learn more

- I read the book " Thinking, Fast and Slow " by Daniel Kahneman and it drastically changed how I think.

- Kahneman argues that we have two modes of thinking, System 1 and System 2, that impact our choices.

- Read below to learn how the book (audiobook also available) helped me think more mindfully.

During the pandemic, I embraced quarantine life by pursuing more of my hobbies. There was just one problem: All of them led to a much busier schedule. From writing to taking a dance class to volunteering, I felt like I was always hustling from one thing to the next.

As my days continued to fill up with more and more activities, it felt like I was constantly checking off something on a list and moving to the next item as quickly as possible. Groceries? Check. Laundry? Check. Zumba? Check.

While thinking fast is helpful for minuscule decisions like choosing an outfit, it's not beneficial when making big choices in my personal and professional life, like wondering if I should start a new business. At times, I've even been guilty of assuming things instead of thinking through them clearly, which negatively affected my actions.

To effectively slow down, especially for high stake situations, I needed to understand why I'm so prone to thinking quickly in the first place. In my quest to learn more about how my mind works , I came across " Thinking, Fast and Slow " by Daniel Kahneman, a world-famous psychologist and winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics.

" Thinking, Fast and Slow " is all about how two systems — intuition and slow thinking — shape our judgment, and how we can effectively tap into both. Using principles of behavioral economics, Kahneman walks us through how to think and avoid mistakes in situations when the stakes are really high.

If you're prone to making rash decisions that you sometimes regret — or feel too burned out to spend a lot of time weighing out the pros and cons of certain choices — this book is definitely worth checking out.

3 important things I learned from "Thinking Fast and Slow":

Solving complicated problems takes mental work, so our brain cuts corners when we're tired or stressed..

Sometimes we think fast and sometimes we think slow. One of the book's main ideas is to showcase how the brain uses these two systems for thinking and decision-making processes. System 1 operates intuitively and automatically – we use it to think fast, like when we drive a car or recall our age in conversation. Meanwhile, System 2 uses problem-solving and concentration – we use it to think slowly, like when we calculate a math problem or fill out our tax returns.

Since thinking slow requires conscious effort, System 2 is best activated when we have self-control, concentration, and focus. However, in situations when we don't have those – like when we feel tired or stressed — System 1 impulsively takes over, coloring our judgment.

I recognized that my fast thinking was attributed to the fact that I was busy all the time and didn't incorporate very many breaks into my schedule. I felt exhausted and distracted at the end of long days, so I was using System 1 to make decisions instead of System 2. To gain more concentration and focus, I started practicing more mindfulness strategies and incorporating more breaks, which have helped me tremendously in making better choices for myself.

One of the main reasons we jump to conclusions is confirmation bias.

Kahneman says our System 1 is gullible and biased, whereas our System 2 is doubting and questioning — and we need both to shape our beliefs and values. When I was making a decision, I found that I was searching for evidence that supported my choice, rather than finding counterexamples. I made decisions so quickly using System 1 that I didn't start questioning those decisions until I realized I didn't make the right choice.

Now, I make sure I'm truly weighing the pros and cons of each decision, especially when the stakes are high. For example, I'm moving to a different city in the next few months and am currently looking at apartments. I first thought about moving to a particular place based on a friend's recommendation, which seemed like the easiest thing to do.

But, after reading the book, I learned I was actually rushing the decision and looking for evidence to support moving there, instead of really thinking things through. Now, I'm making sure to look at a wide variety of options with things I like and things I dislike about each apartment, such as price, location, and amenities.

When making a decision, we should always focus on multiple factors.

When I read this part of the book, I found this point extremely relatable. Most decisions are tied to weighing multiple factors, but sometimes we only focus on the one factor we're getting the most pleasure from, which can be a big mistake, because the factor that we initially find fulfilling often gives us less pleasure as time progresses.

Using this logic, I look at the bigger picture and make sure I am attracted to a commitment for multiple reasons. In my apartment hunt, I'm now prioritizing moving into buildings with a rooftop, gym, and lobby, so I can not only enjoy those amenities but easily meet new people in a new city. There are always a few apartments I come across with a beautiful, renovated kitchen, and while it would be so nice to cook with a luxury oven and stove, I realize that I'd get used to those appliances and it wouldn't make a difference to me as much as being able to hang out with my neighbors or friends on the roof.

The bottom line

If you're having a tough time slowing down and making decisions, it can be a great time to explore and understand your thinking patterns to improve, and this book can help you do it.

- Main content

Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman: Summary & Notes

Rated : 9/10

Available at: Amazon

ISBN: 9780385676533

Related: Influence , Mistakes Were Made (But Not By Me)

Get access to my collection of 100+ detailed book notes

This is a widely-cited, occasionally mind-bending work from Daniel Kahneman that describes many of the human errors in thinking that he and others have discovered through their psychology research.

This book has influenced many, and can be considered one of the most significant books on psychology (along with books like Influence ), in recent years. Should be read by anyone looking to improve their own decision-making, regardless of field (indeed, most of the book is applicable throughout daily life).

Introduction

- Valid intuitions develop when experts have learned to recognize familiar elements in a new situation and to act in a manner that is appropriate to it.

- The essence of intuitive heuristics: when faced with a difficult question, we often answer an easier one instead, usually without noticing the substitution.

- We are prone to overestimate how much we understand about the world and to underestimate the role of chance in events. Overconfidence is fed by the illusory certainty of hindsight. My views on this topic have been influenced by Nassim Taleb, the author of The Black Swan .

Part 1: Two Systems

Chapter 1: the characters of the story.

- System 1 operates automatically and quickly, with little or no effort and no sense of voluntary control.

- System 2 allocates attention to the effortful mental activities that demand it, including complex computations. The operations of System 2 are often associated with the subjective experience of agency, choice, and concentration.

- I describe System 1 as effortlessly originating impressions and feelings that are the main sources of the explicit beliefs and deliberate choices of System 2. The automatic operations of System 1 generate surprisingly complex patterns of ideas, but only the slower System 2 can construct thoughts in an orderly series of steps.

In rough order of complexity, here are some examples of the automatic activities that are attributed to System 1:

- Detect that one object is more distant than another.

- Orient to the source of a sudden sound.

The highly diverse operations of System 2 have one feature in common: they require attention and are disrupted when attention is drawn away. Here are some examples:

- Focus on the voice of a particular person in a crowded and noisy room.

- Count the occurrences of the letter a in a page of text.

- Check the validity of a complex logical argument.

- It is the mark of effortful activities that they interfere with each other, which is why it is difficult or impossible to conduct several at once.

- The gorilla study illustrates two important facts about our minds: we can be blind to the obvious , and we are also blind to our blindness.

- One of the tasks of System 2 is to overcome the impulses of System 1. In other words, System 2 is in charge of self-control.

- The best we can do is a compromise: learn to recognize situations in which mistakes are likely and try harder to avoid significant mistakes when the stakes are high.

Chapter 2: Attention and Effort

- People, when engaged in a mental sprint, become effectively blind.

- As you become skilled in a task, its demand for energy diminishes. Talent has similar effects.

- One of the significant discoveries of cognitive psychologists in recent decades is that switching from one task to another is effortful, especially under time pressure.

Chapter 3: The Lazy Controller

- It is now a well-established proposition that both self-control and cognitive effort are forms of mental work. Several psychological studies have shown that people who are simultaneously challenged by a demanding cognitive task and by a temptation are more likely to yield to the temptation.

- People who are cognitively busy are also more likely to make selfish choices, use sexist language, and make superficial judgments in social situations. A few drinks have the same effect, as does a sleepless night.

- Baumeister’s group has repeatedly found that an effort of will or self-control is tiring; if you have had to force yourself to do something, you are less willing or less able to exert self-control when the next challenge comes around. The phenomenon has been named ego depletion.

- The evidence is persuasive: activities that impose high demands on System 2 require self-control, and the exertion of self-control is depleting and unpleasant. Unlike cognitive load, ego depletion is at least in part a loss of motivation. After exerting self-control in one task, you do not feel like making an effort in another, although you could do it if you really had to. In several experiments, people were able to resist the effects of ego depletion when given a strong incentive to do so.

- Restoring glucose levels can have a counteracting effect to mental depletion.

Chapter 4: The Associative Machine

- Priming effects take many forms. If the idea of EAT is currently on your mind (whether or not you are conscious of it), you will be quicker than usual to recognize the word SOUP when it is spoken in a whisper or presented in a blurry font. And of course you are primed not only for the idea of soup but also for a multitude of food-related ideas, including fork, hungry, fat, diet, and cookie.

- Priming is not limited to concepts and words; your actions and emotions can be primed by events of which you are not even aware, including simple gestures.

- Money seems to prime individualism: reluctance to be involved with, depend on, or accept demands from others.

- Note: the effects of primes are robust but not necessarily large; likely only a few in a hundred voters will be affected.

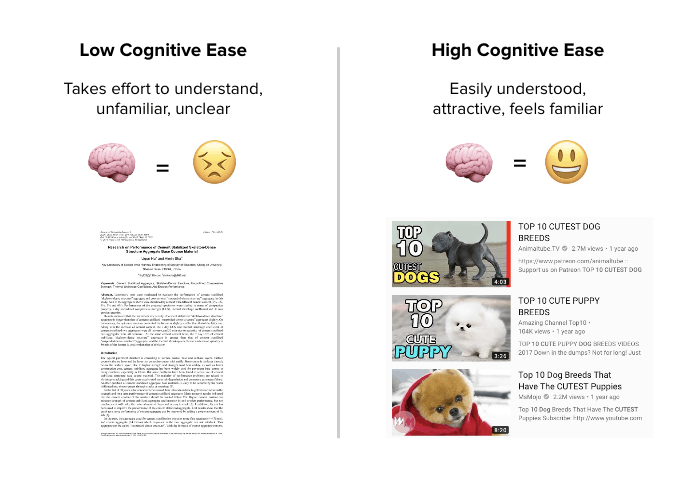

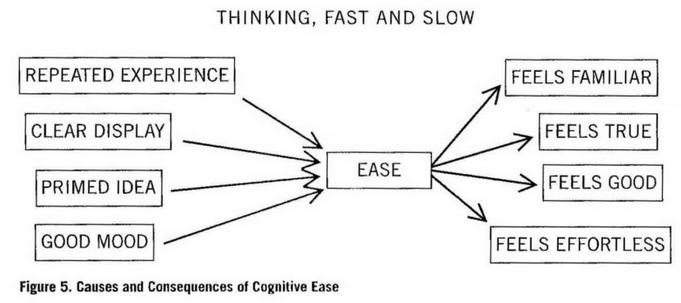

Chapter 5: Cognitive Ease

- Cognitive ease: no threats, no major news, no need to redirect attention or mobilize effort.

- Cognitive strain: affected by both the current level of effort and the presence of unmet demands; requires increased mobilization of System 2.

- Memories and thinking are subject to illusions, just as the eyes are.

- Predictable illusions inevitable occur if a judgement is based on an impression of cognitive ease or strain.

- A reliable way to make people believe in falsehoods is frequent repetition, because familiarity is not easily distinguished from truth.

- If you want to make recipients believe something, general principle is to ease cognitive strain: make font legible, use high-quality paper to maximize contrasts, print in bright colours, use simple language, put things in verse (make them memorable), and if you quote, make sure it’s an easy name to pronounce.

- Weird example: stocks with pronounceable tickers do better over time.

- Mood also affects performance: happy moods dramatically improve accuracy. Good mood, intuition, creativity, gullibility and increased reliance on System 1 form a cluster.

- At the other pole, sadness, vigilance, suspicion, an analytic approach, and increased effort also go together. A happy mood loosens the control of System 2 over performance: when in a good mood, people become more intuitive and more creative but also less vigilant and more prone to logical errors.

Chapter 6: Norms, Surprises, and Causes

- We can detect departures from the norm (even small ones) within two-tenths of a second.

Chapter 7: A Machine for Jumping to Conclusions

- Jumping to conclusions is efficient if the conclusions are likely to be correct and the costs of an occasional mistake acceptable, and if the jump saves much time and effort. Jumping to conclusions is risky when the situation is unfamiliar, the stakes are high, and there is no time to collect more information.

A Bias to Believe and Confirm

- The operations of associative memory contribute to a general confirmation bias . When asked, "Is Sam friendly?" different instances of Sam’s behavior will come to mind than would if you had been asked "Is Sam unfriendly?" A deliberate search for confirming evidence, known as positive test strategy , is also how System 2 tests a hypothesis. Contrary to the rules of philosophers of science, who advise testing hypotheses by trying to refute them, people (and scientists, quite often) seek data that are likely to be compatible with the beliefs they currently hold.

Exaggerated Emotional Coherence (Halo Effect)

- If you like the president’s politics, you probably like his voice and his appearance as well. The tendency to like (or dislike) everything about a person—including things you have not observed—is known as the halo effect.

- To counter, you should decor relate error - in other words, to get useful information from multiple sources, make sure these sources are independent, then compare.

- The principle of independent judgments (and decorrelated errors) has immediate applications for the conduct of meetings, an activity in which executives in organizations spend a great deal of their working days. A simple rule can help: before an issue is discussed, all members of the committee should be asked to write a very brief summary of their position.

What You See is All There is (WYSIATI)

- The measure of success for System 1 is the coherence of the story it manages to create. The amount and quality of the data on which the story is based are largely irrelevant. When information is scarce, which is a common occurrence, System 1 operates as a machine for jumping to conclusions.

- WYSIATI: What you see is all there is.

- WYSIATI helps explain some biases of judgement and choice, including:

- Overconfidence: As the WYSIATI rule implies, neither the quantity nor the quality of the evidence counts for much in subjective confidence. The confidence that individuals have in their beliefs depends mostly on the quality of the story they can tell about what they see, even if they see little.

- Framing effects : Different ways of presenting the same information often evoke different emotions. The statement that the odds of survival one month after surgery are 90% is more reassuring than the equivalent statement that mortality within one month of surgery is 10%.

- Base-rate neglect : Recall Steve, the meek and tidy soul who is often believed to be a librarian. The personality description is salient and vivid, and although you surely know that there are more male farmers than male librarians, that statistical fact almost certainly did not come to your mind when you first considered the question.

Chapter 9: Answering an Easier Question

- We often generate intuitive opinions on complex matters by substituting the target question with a related question that is easier to answer.

- The present state of mind affects how people evaluate their happiness.

- affect heuristic: in which people let their likes and dislikes determine their beliefs about the world. Your political preference determines the arguments that you find compelling.

- If you like the current health policy, you believe its benefits are substantial and its costs more manageable than the costs of alternatives.

Part 2: Heuristics and Biases

Chapter 10: the law of small numbers.

- A random event, by definition, does not lend itself to explanation, but collections of random events do behave in a highly regular fashion.

- Large samples are more precise than small samples.

- Small samples yield extreme results more often than large samples do.

A Bias of Confidence Over Doubt

- The strong bias toward believing that small samples closely resemble the population from which they are drawn is also part of a larger story: we are prone to exaggerate the consistency and coherence of what we see.

Cause and Chance

- Our predilection for causal thinking exposes us to serious mistakes in evaluating the randomness of truly random events.

Chapter 11: Anchoring Effects

- The phenomenon we were studying is so common and so important in the everyday world that you should know its name: it is an anchoring effect . It occurs when people consider a particular value for an unknown quantity before estimating that quantity. What happens is one of the most reliable and robust results of experimental psychology: the estimates stay close to the number that people considered—hence the image of an anchor.

The Anchoring Index

- The anchoring measure would be 100% for people who slavishly adopt the anchor as an estimate, and zero for people who are able to ignore the anchor altogether. The value of 55% that was observed in this example is typical. Similar values have been observed in numerous other problems.

- Powerful anchoring effects are found in decisions that people make about money, such as when they choose how much to contribute to a cause.

- In general, a strategy of deliberately "thinking the opposite" may be a good defense against anchoring effects, because it negates the biased recruitment of thoughts that produces these effects.

Chapter 12: The Science of Availability

- The availability heuristic , like other heuristics of judgment, substitutes one question for another: you wish to estimate the size of a category or the frequency of an event, but you report an impression of the ease with which instances come to mind. Substitution of questions inevitably produces systematic errors.

- You can discover how the heuristic leads to biases by following a simple procedure: list factors other than frequency that make it easy to come up with instances. Each factor in your list will be a potential source of bias.

- Resisting this large collection of potential availability biases is possible, but tiresome. You must make the effort to reconsider your impressions and intuitions by asking such questions as, "Is our belief that thefts by teenagers are a major problem due to a few recent instances in our neighborhood?" or "Could it be that I feel no need to get a flu shot because none of my acquaintances got the flu last year?" Maintaining one’s vigilance against biases is a chore—but the chance to avoid a costly mistake is sometimes worth the effort.

The Psychology of Availability

For example, people:

- believe that they use their bicycles less often after recalling many rather than few instances

- are less confident in a choice when they are asked to produce more arguments to support it

- are less confident that an event was avoidable after listing more ways it could have been avoided

- are less impressed by a car after listing many of its advantages

The difficulty of coming up with more examples surprises people, and they subsequently change their judgement.

The following are some conditions in which people "go with the flow" and are affected more strongly by ease of retrieval than by the content they retrieved:

- when they are engaged in another effortful task at the same time

- when they are in a good mood because they just thought of a happy episode in their life

- if they score low on a depression scale

- if they are knowledgeable novices on the topic of the task, in contrast to true experts

- when they score high on a scale of faith in intuition

- if they are (or are made to feel) powerful

Chapter 13: Availability, Emotion, and Risk

- The affect heuristic is an instance of substitution, in which the answer to an easy question (How do I feel about it?) serves as an answer to a much harder question (What do I think about it?).

- Experts sometimes measure things more objectively, weighing total number of lives saved, or something similar, while many citizens will judge “good” and “bad” types of deaths.

- An availability cascade is a self-sustaining chain of events, which may start from media reports of a relatively minor event and lead up to public panic and large-scale government action.

- The Alar tale illustrates a basic limitation in the ability of our mind to deal with small risks: we either ignore them altogether or give them far too much weight—nothing in between.

- In today’s world, terrorists are the most significant practitioners of the art of inducing availability cascades.

- Psychology should inform the design of risk policies that combine the experts’ knowledge with the public’s emotions and intuitions.

Chapter 14: Tom W’s Specialty

- The representativeness heuristic is involved when someone says "She will win the election; you can see she is a winner" or "He won’t go far as an academic; too many tattoos."

One sin of representativeness is an excessive willingness to predict the occurrence of unlikely (low base-rate) events. Here is an example: you see a person reading The New York Times on the New York subway. Which of the following is a better bet about the reading stranger?

- She has a PhD.

- She does not have a college degree.

Representativeness would tell you to bet on the PhD, but this is not necessarily wise. You should seriously consider the second alternative, because many more nongraduates than PhDs ride in New York subways.

The second sin of representativeness is insensitivity to the quality of evidence.

There is one thing you can do when you have doubts about the quality of the evidence: let your judgments of probability stay close to the base rate.

The essential keys to disciplined Bayesian reasoning can be simply summarized:

- Anchor your judgment of the probability of an outcome on a plausible base rate.

- Question the diagnosticity of your evidence.

Chapter 15: Linda: Less is More

- When you specify a possible event in greater detail you can only lower its probability. The problem therefore sets up a conflict between the intuition of representativeness and the logic of probability.

- conjunction fallacy: when people judge a conjunction of two events to be more probable than one of the events in a direct comparison.

- Representativeness belongs to a cluster of closely related basic assessments that are likely to be generated together. The most representative outcomes combine with the personality description to produce the most coherent stories. The most coherent stories are not necessarily the most probable, but they are plausible , and the notions of coherence, plausibility, and probability are easily confused by the unwary.

Chapter 17: Regression to the Mean

- An important principle of skill training: rewards for improved performance work better than punishment of mistakes. This proposition is supported by much evidence from research on pigeons, rats, humans, and other animals.

Talent and Luck

- My favourite equations:

- success = talent + luck

- great success = a little more talent + a lot of luck

Understanding Regression

- The general rule is straightforward but has surprising consequences: whenever the correlation between two scores is imperfect, there will be regression to the mean.

- If the correlation between the intelligence of spouses is less than perfect (and if men and women on average do not differ in intelligence), then it is a mathematical inevitability that highly intelligent women will be married to husbands who are on average less intelligent than they are (and vice versa, of course).

Chapter 18: Taming Intuitive Predictions

- Some predictive judgements, like those made by engineers, rely largely on lookup tables, precise calculations, and explicit analyses of outcomes observed on similar occasions. Others involve intuition and System 1, in two main varieties:

- Some intuitions draw primarily on skill and expertise acquired by repeated experience. The rapid and automatic judgements of chess masters, fire chiefs, and doctors illustrate these.

- Others, which are sometimes subjectively indistinguishable from the first, arise from the operation of heuristics that often substitute an easy question for the harder one that was asked.

- We are capable of rejecting information as irrelevant or false, but adjusting for smaller weaknesses in the evidence is not something that System 1 can do. As a result, intuitive predictions are almost completely insensitive to the actual predictive quality of the evidence.

A Correction for Inuitive Predictions

- Recall that the correlation between two measures—in the present case reading age and GPA—is equal to the proportion of shared factors among their determinants. What is your best guess about that proportion? My most optimistic guess is about 30%. Assuming this estimate, we have all we need to produce an unbiased prediction. Here are the directions for how to get there in four simple steps:

- Start with an estimate of average GPA.

- Determine the GPA that matches your impression of the evidence.

- Estimate the correlation between your evidence and GPA.

- If the correlation is .30, move 30% of the distance from the average to the matching GPA.

Part 3: Overconfidence

Chapter 19: the illusion of understanding.

- From Taleb: narrative fallacy : our tendency to reshape the past into coherent stories that shape our views of the world and expectations for the future.

- As a result, we tend to overestimate skill, and underestimate luck.

- Once humans adopt a new view of the world, we have difficulty recalling our old view, and how much we were surprised by past events.

- Outcome bias : our tendency to put too much blame on decision makers for bad outcomes vs. good ones.

- This both influences risk aversion, and disproportionately rewarding risky behaviour (the entrepreneur who gambles big and wins).

- At best, a good CEO is about 10% better than random guessing.

Chapter 20: The Illusion of Validity

- We often vastly overvalue the evidence at hand; discount the amount of evidence and its quality in favour of the better story, and follow the people we love and trust with no evidence in other cases.

- The illusion of skill is maintained by powerful professional cultures.

- Experts/pundits are rarely better (and often worse) than random chance, yet often believe at a much higher confidence level in their predictions.

Chapter 21: Intuitions vs. Formulas

A number of studies have concluded that algorithms are better than expert judgement, or at least as good.

The research suggests a surprising conclusion: to maximize predictive accuracy, final decisions should be left to formulas, especially in low-validity environments.

More recent research went further: formulas that assign equal weights to all the predictors are often superior, because they are not affected by accidents of sampling.

In a memorable example, Dawes showed that marital stability is well predicted by a formula:

- frequency of lovemaking minus frequency of quarrels

The important conclusion from this research is that an algorithm that is constructed on the back of an envelope is often good enough to compete with an optimally weighted formula, and certainly good enough to outdo expert judgment.

Intuition can be useful, but only when applied systematically.

Interviewing

To implement a good interview procedure:

- Select some traits required for success (six is a good number). Try to ensure they are independent.

- Make a list of questions for each trait, and think about how you will score it from 1-5 (what would warrant a 1, what would make a 5).

- Collect information as you go, assessing each trait in turn.

- Then add up the scores at the end.

Chapter 22: Expert Intuition: When Can We Trust It?

When can we trust intuition/judgements? The answer comes from the two basic conditions for acquiring a skill:

- an environment that is sufficiently regular to be predictable

- an opportunity to learn these regularities through prolonged practice

When both these conditions are satisfied, intuitions are likely to be skilled.

Whether professionals have a chance to develop intuitive expertise depends essentially on the quality and speed of feedback, as well as on sufficient opportunity to practice.

Among medical specialties, anesthesiologists benefit from good feedback, because the effects of their actions are likely to be quickly evident. In contrast, radiologists obtain little information about the accuracy of the diagnoses they make and about the pathologies they fail to detect. Anesthesiologists are therefore in a better position to develop useful intuitive skills.

Chapter 23: The Outside View

The inside view : when we focus on our specific circumstances and search for evidence in our own experiences.

- Also: when you fail to account for unknown unknowns.

The outside view : when you take into account a proper reference class/base rate.

Planning fallacy: plans and forecasts that are unrealistically close to best-case scenarios could be improved by consulting the statistics of similar cases

Reference class forecasting : the treatment for the planning fallacy

The outside view is implemented by using a large database, which provides information on both plans and outcomes for hundreds of projects all over the world, and can be used to provide statistical information about the likely overruns of cost and time, and about the likely underperformance of projects of different types.

The forecasting method that Flyvbjerg applies is similar to the practices recommended for overcoming base-rate neglect:

- Identify an appropriate reference class (kitchen renovations, large railway projects, etc.).

- Obtain the statistics of the reference class (in terms of cost per mile of railway, or of the percentage by which expenditures exceeded budget). Use the statistics to generate a baseline prediction.

- Use specific information about the case to adjust the baseline prediction, if there are particular reasons to expect the optimistic bias to be more or less pronounced in this project than in others of the same type.

- Organizations face the challenge of controlling the tendency of executives competing for resources to present overly optimistic plans. A well-run organization will reward planners for precise execution and penalize them for failing to anticipate difficulties, and for failing to allow for difficulties that they could not have anticipated—the unknown unknowns.

Chapter 24: The Engine of Capitalism

Optimism bias : always viewing positive outcomes or angles of events

Danger: losing track of reality and underestimating the role of luck, as well as the risk involved.

To try and mitigate the optimism bias, you should a) be aware of likely biases and planning fallacies that can affect those who are predisposed to optimism, and,

Perform a premortem:

- The procedure is simple: when the organization has almost come to an important decision but has not formally committed itself, Klein proposes gathering for a brief session a group of individuals who are knowledgeable about the decision. The premise of the session is a short speech: "Imagine that we are a year into the future. We implemented the plan as it now exists. The outcome was a disaster. Please take 5 to 10 minutes to write a brief history of that disaster."

Part 4: Choices

Chapter 25: bernoulli’s error.

- theory-induced blindness : once you have accepted a theory and used it as a tool in your thinking, it is extraordinarily difficult to notice its flaws.

Chapter 26: Prospect Theory

- It’s clear now that there are three cognitive features at the heart of prospect theory. They play an essential role in the evaluation of financial outcomes and are common to many automatic processes of perception, judgment, and emotion. They should be seen as operating characteristics of System 1.

- Evaluation is relative to a neutral reference point, which is sometimes referred to as an "adaptation level."

- For financial outcomes, the usual reference point is the status quo, but it can also be the outcome that you expect, or perhaps the outcome to which you feel entitled, for example, the raise or bonus that your colleagues receive.

- Outcomes that are better than the reference points are gains. Below the reference point they are losses.

- A principle of diminishing sensitivity applies to both sensory dimensions and the evaluation of changes of wealth.

- The third principle is loss aversion. When directly compared or weighted against each other, losses loom larger than gains. This asymmetry between the power of positive and negative expectations or experiences has an evolutionary history. Organisms that treat threats as more urgent than opportunities have a better chance to survive and reproduce.

Loss Aversion

- The “loss aversion ratio” has been estimated in several experiments and is usually in the range of 1.5 to 2.5.

Chapter 27: The Endowment Effect

- Endowment effect : for certain goods, the status quo is preferred, particularly for goods that are not regularly traded or for goods intended “for use” - to be consumed or otherwise enjoyed.

- Note: not present when owners view their goods as carriers of value for future exchanges.

Chapter 28: Bad Events

- The brain responds quicker to bad words (war, crime) than happy words (peace, love).

- If you are set to look for it, the asymmetric intensity of the motives to avoid losses and to achieve gains shows up almost everywhere. It is an ever-present feature of negotiations, especially of renegotiations of an existing contract, the typical situation in labor negotiations and in international discussions of trade or arms limitations. The existing terms define reference points, and a proposed change in any aspect of the agreement is inevitably viewed as a concession that one side makes to the other. Loss aversion creates an asymmetry that makes agreements difficult to reach. The concessions you make to me are my gains, but they are your losses; they cause you much more pain than they give me pleasure.

Chapter 29: The Fourfold Pattern

- Whenever you form a global evaluation of a complex object—a car you may buy, your son-in-law, or an uncertain situation—you assign weights to its characteristics. This is simply a cumbersome way of saying that some characteristics influence your assessment more than others do.

- The conclusion is straightforward: the decision weights that people assign to outcomes are not identical to the probabilities of these outcomes, contrary to the expectation principle. Improbable outcomes are overweighted—this is the possibility effect. Outcomes that are almost certain are underweighted relative to actual certainty.

- When we looked at our choices for bad options, we quickly realized that we were just as risk seeking in the domain of losses as we were risk averse in the domain of gains.

- Certainty effect : at high probabilities, we seek to avoid loss and therefore accept worse outcomes in exchange for certainty, and take high risk in exchange for possibility.

- Possibility effect: at low probabilities, we seek a large gain despite risk, and avoid risk despite a poor outcome.

Indeed, we identified two reasons for this effect.

- First, there is diminishing sensitivity. The sure loss is very aversive because the reaction to a loss of $900 is more than 90% as intense as the reaction to a loss of $1,000.

- The second factor may be even more powerful: the decision weight that corresponds to a probability of 90% is only about 71, much lower than the probability.

- Many unfortunate human situations unfold in the top right cell. This is where people who face very bad options take desperate gambles, accepting a high probability of making things worse in exchange for a small hope of avoiding a large loss. Risk taking of this kind often turns manageable failures into disasters.

Chapter 30: Rare Events

- The probability of a rare event is most likely to be overestimated when the alternative is not fully specified.

- Emotion and vividness influence fluency, availability, and judgments of probability—and thus account for our excessive response to the few rare events that we do not ignore.

- Adding vivid details, salience and attention to a rare event will increase the weighting of an unlikely outcome.

- When this doesn’t occur, we tend to neglect the rare event.

Chapter 31: Risk Policies

There were two ways of construing decisions i and ii:

- narrow framing: a sequence of two simple decisions, considered separately

- broad framing: a single comprehensive decision, with four options

Broad framing was obviously superior in this case. Indeed, it will be superior (or at least not inferior) in every case in which several decisions are to be contemplated together.

Decision makers who are prone to narrow framing construct a preference every time they face a risky choice. They would do better by having a risk policy that they routinely apply whenever a relevant problem arises. Familiar examples of risk policies are "always take the highest possible deductible when purchasing insurance" and "never buy extended warranties." A risk policy is a broad frame.

Chapter 32: Keeping Score

- Agency problem : when the incentives of an agent are in conflict with the objectives of a larger group, such as when a manager continues investing in a project because he has backed it, when it’s in the firms best interest to cancel it.

- Sunk-cost fallacy: the decision to invest additional resources in a losing account, when better investments are available.

- Disposition effect : the preference to end something on a positive, seen in investment when there is a much higher preference to sell winners and “end positive” than sell losers.

- An instance of narrow framing .

- People expect to have stronger emotional reactions (including regret) to an outcome produced by action than to the same outcome when it is produced by inaction.

- To inoculate against regret: be explicit about your anticipation of it, and consider it when making decisions. Also try and preclude hindsight bias (document your decision-making process).

- Also know that people generally anticipate more regret than they will actually experience.

Chapter 33: Reversals

- You should make sure to keep a broad frame when evaluating something; seeing cases in isolation is more likely to lead to a System 1 reaction.

Chapter 34: Frames and Reality

- The framing of something influences the outcome to a great degree.

- For example, your moral feelings are attached to frames, to descriptions of reality rather than to reality itself.

- Another example: the best single predictor of whether or not people will donate their organs is the designation of the default option that will be adopted without having to check the box.

Part 5: Two Selves

Chapter 35: two selves.

- Peak-end rule : The global retrospective rating was well predicted by the average of the level of pain reported at the worst moment of the experience and at its end.

- We tend to overrate the end of an experience when remembering the whole.

- Duration neglect : The duration of the procedure had no effect whatsoever on the ratings of total pain.

- Generally: we tend to ignore the duration of an event when evaluating an experience.

- Confusing experience with the memory of it is a compelling cognitive illusion—and it is the substitution that makes us believe a past experience can be ruined.

Chapter 37: Experienced Well-Being

- One way to improve experience is to shift from passive leisure (TV watching) to active leisure, including socializing and exercising.

- The second-best predictor of feelings of a day is whether a person did or did not have contacts with friends or relatives.

- It is only a slight exaggeration to say that happiness is the experience of spending time with people you love and who love you.

- Can money buy happiness? Being poor makes one miserable, being rich may enhance one’s life satisfaction, but does not (on average) improve experienced well-being.

- Severe poverty amplifies the effect of other misfortunes of life.

- The satiation level beyond which experienced well-being no longer increases was a household income of about $75,000 in high-cost areas (it could be less in areas where the cost of living is lower). The average increase of experienced well-being associated with incomes beyond that level was precisely zero.

Chapter 38: Thinking About Life

- Experienced well-being is on average unaffected by marriage, not because marriage makes no difference to happiness but because it changes some aspects of life for the better and others for the worse (how one’s time is spent).

- One reason for the low correlations between individuals’ circumstances and their satisfaction with life is that both experienced happiness and life satisfaction are largely determined by the genetics of temperament. A disposition for well-being is as heritable as height or intelligence, as demonstrated by studies of twins separated at birth.

- The importance that people attached to income at age 18 also anticipated their satisfaction with their income as adults.

- The people who wanted money and got it were significantly more satisfied than average; those who wanted money and didn’t get it were significantly more dissatisfied. The same principle applies to other goals— one recipe for a dissatisfied adulthood is setting goals that are especially difficult to attain.

- Measured by life satisfaction 20 years later, the least promising goal that a young person could have was "becoming accomplished in a performing art."

The focusing illusion :

- Nothing in life is as important as you think it is when you are thinking about it.

Miswanting: bad choices that arise from errors of affective forecasting; common example is the focusing illusion causing us overweight the effect of purchases on our future well-being.

Conclusions

Rationality

- Rationality is logical coherence—reasonable or not. Econs are rational by this definition, but there is overwhelming evidence that Humans cannot be. An Econ would not be susceptible to priming, WYSIATI, narrow framing, the inside view, or preference reversals, which Humans cannot consistently avoid.

- The definition of rationality as coherence is impossibly restrictive; it demands adherence to rules of logic that a finite mind is not able to implement.

- The assumption that agents are rational provides the intellectual foundation for the libertarian approach to public policy: do not interfere with the individual’s right to choose, unless the choices harm others.

- Thaler and Sunstein advocate a position of libertarian paternalism, in which the state and other institutions are allowed to nudge people to make decisions that serve their own long-term interests. The designation of joining a pension plan as the default option is an example of a nudge.

Two Systems

- What can be done about biases? How can we improve judgments and decisions, both our own and those of the institutions that we serve and that serve us? The short answer is that little can be achieved without a considerable investment of effort. As I know from experience, System 1 is not readily educable. Except for some effects that I attribute mostly to age, my intuitive thinking is just as prone to overconfidence, extreme predictions, and the planning fallacy as it was before I made a study of these issues. I have improved only in my ability to recognize situations in which errors are likely: "This number will be an anchor…," "The decision could change if the problem is reframed…" And I have made much more progress in recognizing the errors of others than my own

- The way to block errors that originate in System 1 is simple in principle: recognize the signs that you are in a cognitive minefield, slow down, and ask for reinforcement from System 2.

- Organizations are better than individuals when it comes to avoiding errors, because they naturally think more slowly and have the power to impose orderly procedures. Organizations can institute and enforce the application of useful checklists, as well as more elaborate exercises, such as reference-class forecasting and the premortem.

- At least in part by providing a distinctive vocabulary, organizations can also encourage a culture in which people watch out for one another as they approach minefields.

- The corresponding stages in the production of decisions are the framing of the problem that is to be solved, the collection of relevant information leading to a decision, and reflection and review. An organization that seeks to improve its decision product should routinely look for efficiency improvements at each of these stages.

- There is much to be done to improve decision making. One example out of many is the remarkable absence of systematic training for the essential skill of conducting efficient meetings.

- Ultimately, a richer language is essential to the skill of constructive criticism.

- Decision makers are sometimes better able to imagine the voices of present gossipers and future critics than to hear the hesitant voice of their own doubts. They will make better choices when they trust their critics to be sophisticated and fair, and when they expect their decision to be judged by how it was made, not only by how it turned out.

Want to get my latest book notes? Subscribe to my newsletter to get one email a week with new book notes, blog posts, and favorite articles.

Filter by Keywords

Book Summaries

‘thinking, fast and slow’ book summary: key takeaways and review.

Senior Content Marketing Manager

February 5, 2024

A lot goes on behind the scenes in our minds when making decisions. Our mind operates in two distinct modes—intuitive ‘fast’ thinking and deliberate ‘slow’ thinking. The two systems together are why we often overestimate our ability to make correct decisions.

Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman explores this fascinating interplay in his seminal work, ‘Thinking, Fast and Slow.’ The book uses principles of behavioral economics to show us how to think and to explain why we shouldn’t believe everything that comes to our mind.

In this comprehensive Thinking Fast and Slow summary, we delve into the key takeaways from Kahneman’s groundbreaking book, explore insightful quotes that encapsulate its wisdom, and discover practical applications using ClickUp’s decision-making templates.

Thinking Fast and Slow Summary at Glance

1. functioning quickly without thinking too much , 2. giving full attention to all your complex decisions, 3. cognitive biases and heuristics, 4. prospect theory, 5. endowment effect, 6. regression to the mean, 7. planning fallacy, 8. intuitive expertise, 9. experiencing and remembering the self, popular thinking fast and slow quotes, apply thinking fast and slow learnings with clickup.

If you’re a person who takes a lot of time to make a decision or makes rash decisions that cause regret later, then this Thinking, Fast and Slow summary is for you.

Daniel Kahneman’s book ‘Thinking, Fast, and Slow’ is about two systems, intuition and slow thinking, which help us form our judgment. In the book he walks us through the principles of behavioral economics and how we can avoid mistakes when the stakes are high.

He does this by discussing everything from human psychology and decision-making to stock market gambles and self-control.

The book tells us that our mind combines two systems: System 1, the fast-thinking mode, operates effortlessly and instinctively, relying on intuition and past experiences. In contrast, System 2, the slow-thinking mode, engages in deliberate, logical analysis, often requiring more effort.

Kahneman highlights the “Law of Least Effort”; the human mind is programmed to take the path of least resistance, and solving complex problems depletes our mental capacity for thinking. This explains why we can’t often think deeply when tired or stressed.

He also explains how both systems function simultaneously to affect our perceptions and decision-making. Humans require both systems, and the key is to become aware of how we think so we can avoid significant mistakes when the stakes are high.

Key Takeaways from Thinking Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

The first system of the human mind makes fast decisions and reacts quickly. When playing any game, you have a few minutes to decide your next move; these decisions depend on your intuition.

We use System 1 to think and function intuitively during emergencies without overthinking.

System 1 involves automatic, swift thinking, lacking voluntary control. For instance, perceiving a woman’s facial expression on a date, you intuitively conclude she’s angry. This exemplifies fast thinking, operating with little voluntary control.

The second system of the human mind requires more effort to pay attention to details and critical thinking. System 2 engages in reflective and deliberate thought processes for problem-solving.

You engage in deliberate, methodical thought if you’re given a division problem to solve, like 293/7. This reflects slow thinking, requiring mental activities and conscious effort.

When we face any big challenge or try to take a deep look at situations by employing System 2, we can solve critical situations by focusing our attention on the situation at hand. While the first system generates ideas, intuitions, and impressions, the second system is responsible for exercising self-control and overriding System 1’s impulses.

The author discusses cognitive biases and heuristics in decision-making. Biases like anchoring, availability, confirmation bias, and overconfidence significantly influence our judgments, often leading to suboptimal choices. Awareness of these biases is the first step towards mitigating their impact.

The writer explains this with a bat and ball problem. A bat and a ball cost $1.10 together, and the bat costs $1 more than the ball. What is the cost of the ball?

Most people will answer $0.10, which is incorrect. Intuition and rash thinking force people to assume that the ball costs 10 cents. However, looking at the problem mathematically, if the cost for a ball is $0.10 and the bat is $1 more, then that would mean the bat costs $1.10, making the total $1.20, which is wrong. It is a System 2 problem, requiring the brain to see a $0.05 ball plus a $1.05 bat equals $1.10.

Similarly, people often assume that a small sample size can accurately represent a larger picture, simplifying their world perception. However, as per Kahneman, you should avoid trusting statements based on limited data.

Heuristics and biases pose decision-making challenges due to System 1. System 2’s failure to process information promptly can result in individuals relying on System 1’s immediate and biased impressions, leading to wrong conclusions.

As per the Prospect Theory by Kahneman, humans weigh losses and gains differently. Individuals can make decisions based on perceived gains instead of perceived losses.

Elaborating on this loss aversion theory, Kahneman observes that given a choice between two equal options—one with a view of potential gains and the other with potential losses—people will choose the option with the gain because that’s how the human mind works.

Kahneman also highlights a psychological phenomenon called The Endowment Effect. The theory focuses on our tendency to ascribe higher value to items simply because we own them. This bias has profound implications for economic transactions and negotiations.

The author explains this by telling the story of a professor who collected wines. The professor would purchase bottles ranging in value from $35 to $100, but if any of his students offered to buy one of the bottles for $1,000, he would refuse.

The bottle of wine is a reference point, and then psychology takes over, making the potential loss seem more significant than any corresponding gains.

Kahneman delves into the concept of regression to the mean—extreme events are often followed by more moderate outcomes.

Recognizing this tendency allows accurate predictions and avoids undue optimism or pessimism. For instance, an athlete who does well in their first jump tends to under-perform in the second attempt because their mind is occupied with maintaining the lead.

The Planning Fallacy highlights our inherent tendency to underestimate the time, costs, and risk-taking involved in future actions. Awareness of this fallacy is essential for realistic project planning and goal-setting.

Suppose you are preparing for an upcoming project and predict that one week should be enough to complete it, given your experience. However, as you start the project, you discover new challenges.

Moreover, you fall sick during the implementation phase and become less productive. You realize that your optimism forced you to miscalculate the time and effort needed for the project . This is an example of a planning fallacy.

Kahneman explores the concept of intuitive expertise, emphasizing that true mastery in a field leads to intuitive judgments.

We have all seen doctors with several years of experience instantly recognizing an illness based on the symptoms exhibited by a patient. However, even experts are susceptible to biases, and constant vigilance helps avoid errors of subjective confidence.

Kahneman writes about the Two Selves , i.e. the experiencing self and the remembering self.

Let’s try to understand this with a real-life experience. You listen to your favorite music track on a disc which is scratched at the end and makes a squeaky sound. You might say the ending ruined your music-listening experience. However, that’s incorrect; you listened to the music, and the bad ending couldn’t mar the experience that has already happened. This is simply you mistaking memories for experience.

Rules of memory work by figuring out preferences based on past experiences. The remembering self plays a crucial role in the decision-making process , often influencing choices according to past preferences. For example, if you have a good memory about a past choice, and are asked to make a similar choice again, your memory will influence you to pick the same thing again.

It is important to distinguish between intuition and actual experiences. The experiencing self undergoes events in the present, while the remembering self shapes choices based on memories. Understanding this duality prevents overemphasis on negative experiences.

Below are some of our favorite quotes from the Thinking, Fast and Slow summary:

The main function of System 1 is to maintain and update a model of your personal world, which represents what is normal in it.

One of the primary functions of System 1 is to reinforce the worldview we carry in our mind, which helps us interpret the world regularly, reflecting what is considered normal in our environment and differentiating it from the unexpected Nothing in life is as important as you think it is while you are thinking about it.

Our perceptions of importance are often exaggerated when actively thinking about something at the moment. We often miss the bigger picture by limiting our thinking to a singular thing at the moment

The illusion that we understand the past fosters overconfidence in our ability to predict the future.

The human mind can sometimes think that it can fully comprehend the past, which leads to overconfidence in predicting future events. Often, we keep telling our mind, “I know how this situation ends,” as we have faced a situation in the past that made us overconfident about the outcome You are more likely to learn something by finding surprises in your own behavior than by hearing surprising facts about people in general.

Personal self-discovery through unexpected aspects of one’s own behavior is a more effective learning process than being presented with surprising facts about people in general. After all, a lived experience is a better teacher

The idea that the future is unpredictable is undermined every day by the ease with which the past is explained.

People often oversimplify and confidently explain the past because of the hindsight bias. However, the future truly is unpredictable, and human beings have a tendency to underestimate the complexity of historical events

If you enjoyed this Thinking Fast and Slow summary, you might want to read our summary of Six Thinking Hats . Let’s now understand how you can implement learnings from ‘Thinking, Fast and Slow’ more effectively using ClickUp as a problem-solving software .

ClickUp’s project management platform and decision-making and communication plan templates streamline and improve your thought process.

ClickUp’s Decision-Making Framework Document Template guides users through a structured decision-making process, incorporating both the systems of fast and focused thinking. This ClickUp framework prompts critical considerations, ensuring a comprehensive approach to decision-making.

Making decisions for large projects can be complex. Using ClickUp’s Decision Making Framework Document Template, make your decisions quickly and accurately, weighing the pros and cons of any decision in an intuitive template.

Using different decision-making templates , create a detailed analysis of any topic area you want to implement.

Gather the facts and information reference points around the issue and visualize it with your team in ClickUp’s Board View .

Once you have all the information in front of you, your team can use ClickUp Whiteboard to generate potential ideas and solutions collaboratively to come up with a collective decision.

ClickUp’s Decision Tree Template is a powerful visual aid for mapping out potential outcomes based on different choices and work styles . Like Kahneman’s principles and ideologies, this template assists in creating logical and informed decision pathways.

Use the template to evaluate every path and potential outcome in your project, track the progress of decisions and outcomes by creating tasks, and categorize and add attributes wherever needed.

Leverage your Two Systems Effectively with ClickUp

‘Thinking, Fast and Slow’ digs into the human mind and tries to decode human psychology. It covers the dual systems of thinking and the pitfalls of cognitive biases that shape our decision-making.