How to Write a Case Study: Bookmarkable Guide & Template

Published: November 30, 2023

Earning the trust of prospective customers can be a struggle. Before you can even begin to expect to earn their business, you need to demonstrate your ability to deliver on what your product or service promises.

Sure, you could say that you're great at X or that you're way ahead of the competition when it comes to Y. But at the end of the day, what you really need to win new business is cold, hard proof.

One of the best ways to prove your worth is through a compelling case study. In fact, HubSpot’s 2020 State of Marketing report found that case studies are so compelling that they are the fifth most commonly used type of content used by marketers.

Below, I'll walk you through what a case study is, how to prepare for writing one, what you need to include in it, and how it can be an effective tactic. To jump to different areas of this post, click on the links below to automatically scroll.

Case Study Definition

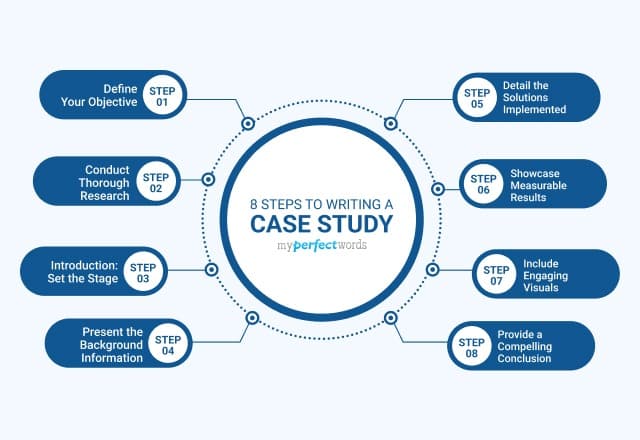

Case study templates, how to write a case study.

- How to Format a Case Study

Business Case Study Examples

A case study is a specific challenge a business has faced, and the solution they've chosen to solve it. Case studies can vary greatly in length and focus on several details related to the initial challenge and applied solution, and can be presented in various forms like a video, white paper, blog post, etc.

In professional settings, it's common for a case study to tell the story of a successful business partnership between a vendor and a client. Perhaps the success you're highlighting is in the number of leads your client generated, customers closed, or revenue gained. Any one of these key performance indicators (KPIs) are examples of your company's services in action.

When done correctly, these examples of your work can chronicle the positive impact your business has on existing or previous customers and help you attract new clients.

Free Case Study Templates

Showcase your company's success using these three free case study templates.

- Data-Driven Case Study Template

- Product-Specific Case Study Template

- General Case Study Template

You're all set!

Click this link to access this resource at any time.

Why write a case study?

I know, you’re thinking “ Okay, but why do I need to write one of these? ” The truth is that while case studies are a huge undertaking, they are powerful marketing tools that allow you to demonstrate the value of your product to potential customers using real-world examples. Here are a few reasons why you should write case studies.

1. Explain Complex Topics or Concepts

Case studies give you the space to break down complex concepts, ideas, and strategies and show how they can be applied in a practical way. You can use real-world examples, like an existing client, and use their story to create a compelling narrative that shows how your product solved their issue and how those strategies can be repeated to help other customers get similar successful results.

2. Show Expertise

Case studies are a great way to demonstrate your knowledge and expertise on a given topic or industry. This is where you get the opportunity to show off your problem-solving skills and how you’ve generated successful outcomes for clients you’ve worked with.

3. Build Trust and Credibility

In addition to showing off the attributes above, case studies are an excellent way to build credibility. They’re often filled with data and thoroughly researched, which shows readers you’ve done your homework. They can have confidence in the solutions you’ve presented because they’ve read through as you’ve explained the problem and outlined step-by-step what it took to solve it. All of these elements working together enable you to build trust with potential customers.

4. Create Social Proof

Using existing clients that have seen success working with your brand builds social proof . People are more likely to choose your brand if they know that others have found success working with you. Case studies do just that — putting your success on display for potential customers to see.

All of these attributes work together to help you gain more clients. Plus you can even use quotes from customers featured in these studies and repurpose them in other marketing content. Now that you know more about the benefits of producing a case study, let’s check out how long these documents should be.

How long should a case study be?

The length of a case study will vary depending on the complexity of the project or topic discussed. However, as a general guideline, case studies typically range from 500 to 1,500 words.

Whatever length you choose, it should provide a clear understanding of the challenge, the solution you implemented, and the results achieved. This may be easier said than done, but it's important to strike a balance between providing enough detail to make the case study informative and concise enough to keep the reader's interest.

The primary goal here is to effectively communicate the key points and takeaways of the case study. It’s worth noting that this shouldn’t be a wall of text. Use headings, subheadings, bullet points, charts, and other graphics to break up the content and make it more scannable for readers. We’ve also seen brands incorporate video elements into case studies listed on their site for a more engaging experience.

Ultimately, the length of your case study should be determined by the amount of information necessary to convey the story and its impact without becoming too long. Next, let’s look at some templates to take the guesswork out of creating one.

To help you arm your prospects with information they can trust, we've put together a step-by-step guide on how to create effective case studies for your business with free case study templates for creating your own.

Tell us a little about yourself below to gain access today:

And to give you more options, we’ll highlight some useful templates that serve different needs. But remember, there are endless possibilities when it comes to demonstrating the work your business has done.

1. General Case Study Template

Do you have a specific product or service that you’re trying to sell, but not enough reviews or success stories? This Product Specific case study template will help.

This template relies less on metrics, and more on highlighting the customer’s experience and satisfaction. As you follow the template instructions, you’ll be prompted to speak more about the benefits of the specific product, rather than your team’s process for working with the customer.

4. Bold Social Media Business Case Study Template

You can find templates that represent different niches, industries, or strategies that your business has found success in — like a bold social media business case study template.

In this template, you can tell the story of how your social media marketing strategy has helped you or your client through collaboration or sale of your service. Customize it to reflect the different marketing channels used in your business and show off how well your business has been able to boost traffic, engagement, follows, and more.

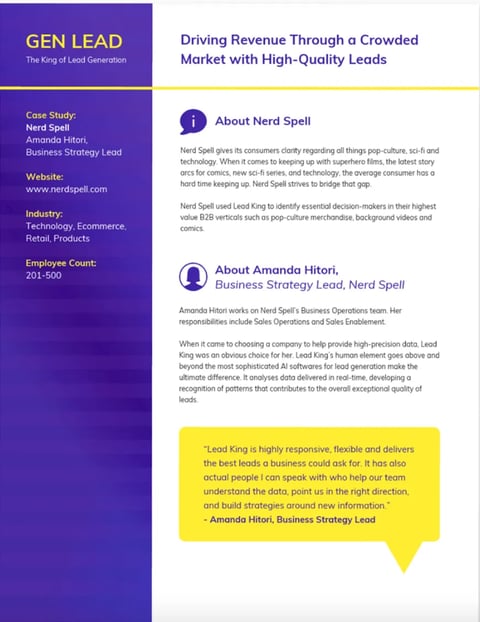

5. Lead Generation Business Case Study Template

It’s important to note that not every case study has to be the product of a sale or customer story, sometimes they can be informative lessons that your own business has experienced. A great example of this is the Lead Generation Business case study template.

If you’re looking to share operational successes regarding how your team has improved processes or content, you should include the stories of different team members involved, how the solution was found, and how it has made a difference in the work your business does.

Now that we’ve discussed different templates and ideas for how to use them, let’s break down how to create your own case study with one.

- Get started with case study templates.

- Determine the case study's objective.

- Establish a case study medium.

- Find the right case study candidate.

- Contact your candidate for permission to write about them.

- Ensure you have all the resources you need to proceed once you get a response.

- Download a case study email template.

- Define the process you want to follow with the client.

- Ensure you're asking the right questions.

- Layout your case study format.

- Publish and promote your case study.

1. Get started with case study templates.

Telling your customer's story is a delicate process — you need to highlight their success while naturally incorporating your business into their story.

If you're just getting started with case studies, we recommend you download HubSpot's Case Study Templates we mentioned before to kickstart the process.

2. Determine the case study's objective.

All business case studies are designed to demonstrate the value of your services, but they can focus on several different client objectives.

Your first step when writing a case study is to determine the objective or goal of the subject you're featuring. In other words, what will the client have succeeded in doing by the end of the piece?

The client objective you focus on will depend on what you want to prove to your future customers as a result of publishing this case study.

Your case study can focus on one of the following client objectives:

- Complying with government regulation

- Lowering business costs

- Becoming profitable

- Generating more leads

- Closing on more customers

- Generating more revenue

- Expanding into a new market

- Becoming more sustainable or energy-efficient

3. Establish a case study medium.

Next, you'll determine the medium in which you'll create the case study. In other words, how will you tell this story?

Case studies don't have to be simple, written one-pagers. Using different media in your case study can allow you to promote your final piece on different channels. For example, while a written case study might just live on your website and get featured in a Facebook post, you can post an infographic case study on Pinterest and a video case study on your YouTube channel.

Here are some different case study mediums to consider:

Written Case Study

Consider writing this case study in the form of an ebook and converting it to a downloadable PDF. Then, gate the PDF behind a landing page and form for readers to fill out before downloading the piece, allowing this case study to generate leads for your business.

Video Case Study

Plan on meeting with the client and shooting an interview. Seeing the subject, in person, talk about the service you provided them can go a long way in the eyes of your potential customers.

Infographic Case Study

Use the long, vertical format of an infographic to tell your success story from top to bottom. As you progress down the infographic, emphasize major KPIs using bigger text and charts that show the successes your client has had since working with you.

Podcast Case Study

Podcasts are a platform for you to have a candid conversation with your client. This type of case study can sound more real and human to your audience — they'll know the partnership between you and your client was a genuine success.

4. Find the right case study candidate.

Writing about your previous projects requires more than picking a client and telling a story. You need permission, quotes, and a plan. To start, here are a few things to look for in potential candidates.

Product Knowledge

It helps to select a customer who's well-versed in the logistics of your product or service. That way, he or she can better speak to the value of what you offer in a way that makes sense for future customers.

Remarkable Results

Clients that have seen the best results are going to make the strongest case studies. If their own businesses have seen an exemplary ROI from your product or service, they're more likely to convey the enthusiasm that you want prospects to feel, too.

One part of this step is to choose clients who have experienced unexpected success from your product or service. When you've provided non-traditional customers — in industries that you don't usually work with, for example — with positive results, it can help to remove doubts from prospects.

Recognizable Names

While small companies can have powerful stories, bigger or more notable brands tend to lend credibility to your own. In fact, 89% of consumers say they'll buy from a brand they already recognize over a competitor, especially if they already follow them on social media.

Customers that came to you after working with a competitor help highlight your competitive advantage and might even sway decisions in your favor.

5. Contact your candidate for permission to write about them.

To get the case study candidate involved, you have to set the stage for clear and open communication. That means outlining expectations and a timeline right away — not having those is one of the biggest culprits in delayed case study creation.

Most importantly at this point, however, is getting your subject's approval. When first reaching out to your case study candidate, provide them with the case study's objective and format — both of which you will have come up with in the first two steps above.

To get this initial permission from your subject, put yourself in their shoes — what would they want out of this case study? Although you're writing this for your own company's benefit, your subject is far more interested in the benefit it has for them.

Benefits to Offer Your Case Study Candidate

Here are four potential benefits you can promise your case study candidate to gain their approval.

Brand Exposure

Explain to your subject to whom this case study will be exposed, and how this exposure can help increase their brand awareness both in and beyond their own industry. In the B2B sector, brand awareness can be hard to collect outside one's own market, making case studies particularly useful to a client looking to expand their name's reach.

Employee Exposure

Allow your subject to provide quotes with credits back to specific employees. When this is an option for them, their brand isn't the only thing expanding its reach — their employees can get their name out there, too. This presents your subject with networking and career development opportunities they might not have otherwise.

Product Discount

This is a more tangible incentive you can offer your case study candidate, especially if they're a current customer of yours. If they agree to be your subject, offer them a product discount — or a free trial of another product — as a thank-you for their help creating your case study.

Backlinks and Website Traffic

Here's a benefit that is sure to resonate with your subject's marketing team: If you publish your case study on your website, and your study links back to your subject's website — known as a "backlink" — this small gesture can give them website traffic from visitors who click through to your subject's website.

Additionally, a backlink from you increases your subject's page authority in the eyes of Google. This helps them rank more highly in search engine results and collect traffic from readers who are already looking for information about their industry.

6. Ensure you have all the resources you need to proceed once you get a response.

So you know what you’re going to offer your candidate, it’s time that you prepare the resources needed for if and when they agree to participate, like a case study release form and success story letter.

Let's break those two down.

Case Study Release Form

This document can vary, depending on factors like the size of your business, the nature of your work, and what you intend to do with the case studies once they are completed. That said, you should typically aim to include the following in the Case Study Release Form:

- A clear explanation of why you are creating this case study and how it will be used.

- A statement defining the information and potentially trademarked information you expect to include about the company — things like names, logos, job titles, and pictures.

- An explanation of what you expect from the participant, beyond the completion of the case study. For example, is this customer willing to act as a reference or share feedback, and do you have permission to pass contact information along for these purposes?

- A note about compensation.

Success Story Letter

As noted in the sample email, this document serves as an outline for the entire case study process. Other than a brief explanation of how the customer will benefit from case study participation, you'll want to be sure to define the following steps in the Success Story Letter.

7. Download a case study email template.

While you gathered your resources, your candidate has gotten time to read over the proposal. When your candidate approves of your case study, it's time to send them a release form.

A case study release form tells you what you'll need from your chosen subject, like permission to use any brand names and share the project information publicly. Kick-off this process with an email that runs through exactly what they can expect from you, as well as what you need from them. To give you an idea of what that might look like, check out this sample email:

8. Define the process you want to follow with the client.

Before you can begin the case study, you have to have a clear outline of the case study process with your client. An example of an effective outline would include the following information.

The Acceptance

First, you'll need to receive internal approval from the company's marketing team. Once approved, the Release Form should be signed and returned to you. It's also a good time to determine a timeline that meets the needs and capabilities of both teams.

The Questionnaire

To ensure that you have a productive interview — which is one of the best ways to collect information for the case study — you'll want to ask the participant to complete a questionnaire before this conversation. That will provide your team with the necessary foundation to organize the interview, and get the most out of it.

The Interview

Once the questionnaire is completed, someone on your team should reach out to the participant to schedule a 30- to 60-minute interview, which should include a series of custom questions related to the customer's experience with your product or service.

The Draft Review

After the case study is composed, you'll want to send a draft to the customer, allowing an opportunity to give you feedback and edits.

The Final Approval

Once any necessary edits are completed, send a revised copy of the case study to the customer for final approval.

Once the case study goes live — on your website or elsewhere — it's best to contact the customer with a link to the page where the case study lives. Don't be afraid to ask your participants to share these links with their own networks, as it not only demonstrates your ability to deliver positive results and impressive growth, as well.

9. Ensure you're asking the right questions.

Before you execute the questionnaire and actual interview, make sure you're setting yourself up for success. A strong case study results from being prepared to ask the right questions. What do those look like? Here are a few examples to get you started:

- What are your goals?

- What challenges were you experiencing before purchasing our product or service?

- What made our product or service stand out against our competitors?

- What did your decision-making process look like?

- How have you benefited from using our product or service? (Where applicable, always ask for data.)

Keep in mind that the questionnaire is designed to help you gain insights into what sort of strong, success-focused questions to ask during the actual interview. And once you get to that stage, we recommend that you follow the "Golden Rule of Interviewing." Sounds fancy, right? It's actually quite simple — ask open-ended questions.

If you're looking to craft a compelling story, "yes" or "no" answers won't provide the details you need. Focus on questions that invite elaboration, such as, "Can you describe ...?" or, "Tell me about ..."

In terms of the interview structure, we recommend categorizing the questions and flowing them into six specific sections that will mirror a successful case study format. Combined, they'll allow you to gather enough information to put together a rich, comprehensive study.

Open with the customer's business.

The goal of this section is to generate a better understanding of the company's current challenges and goals, and how they fit into the landscape of their industry. Sample questions might include:

- How long have you been in business?

- How many employees do you have?

- What are some of the objectives of your department at this time?

Cite a problem or pain point.

To tell a compelling story, you need context. That helps match the customer's need with your solution. Sample questions might include:

- What challenges and objectives led you to look for a solution?

- What might have happened if you did not identify a solution?

- Did you explore other solutions before this that did not work out? If so, what happened?

Discuss the decision process.

Exploring how the customer decided to work with you helps to guide potential customers through their own decision-making processes. Sample questions might include:

- How did you hear about our product or service?

- Who was involved in the selection process?

- What was most important to you when evaluating your options?

Explain how a solution was implemented.

The focus here should be placed on the customer's experience during the onboarding process. Sample questions might include:

- How long did it take to get up and running?

- Did that meet your expectations?

- Who was involved in the process?

Explain how the solution works.

The goal of this section is to better understand how the customer is using your product or service. Sample questions might include:

- Is there a particular aspect of the product or service that you rely on most?

- Who is using the product or service?

End with the results.

In this section, you want to uncover impressive measurable outcomes — the more numbers, the better. Sample questions might include:

- How is the product or service helping you save time and increase productivity?

- In what ways does that enhance your competitive advantage?

- How much have you increased metrics X, Y, and Z?

10. Lay out your case study format.

When it comes time to take all of the information you've collected and actually turn it into something, it's easy to feel overwhelmed. Where should you start? What should you include? What's the best way to structure it?

To help you get a handle on this step, it's important to first understand that there is no one-size-fits-all when it comes to the ways you can present a case study. They can be very visual, which you'll see in some of the examples we've included below, and can sometimes be communicated mostly through video or photos, with a bit of accompanying text.

Here are the sections we suggest, which we'll cover in more detail down below:

- Title: Keep it short. Develop a succinct but interesting project name you can give the work you did with your subject.

- Subtitle: Use this copy to briefly elaborate on the accomplishment. What was done? The case study itself will explain how you got there.

- Executive Summary : A 2-4 sentence summary of the entire story. You'll want to follow it with 2-3 bullet points that display metrics showcasing success.

- About the Subject: An introduction to the person or company you served, which can be pulled from a LinkedIn Business profile or client website.

- Challenges and Objectives: A 2-3 paragraph description of the customer's challenges, before using your product or service. This section should also include the goals or objectives the customer set out to achieve.

- How Product/Service Helped: A 2-3 paragraph section that describes how your product or service provided a solution to their problem.

- Results: A 2-3 paragraph testimonial that proves how your product or service specifically benefited the person or company and helped achieve its goals. Include numbers to quantify your contributions.

- Supporting Visuals or Quotes: Pick one or two powerful quotes that you would feature at the bottom of the sections above, as well as a visual that supports the story you are telling.

- Future Plans: Everyone likes an epilogue. Comment on what's ahead for your case study subject, whether or not those plans involve you.

- Call to Action (CTA): Not every case study needs a CTA, but putting a passive one at the end of your case study can encourage your readers to take an action on your website after learning about the work you've done.

When laying out your case study, focus on conveying the information you've gathered in the most clear and concise way possible. Make it easy to scan and comprehend, and be sure to provide an attractive call-to-action at the bottom — that should provide readers an opportunity to learn more about your product or service.

11. Publish and promote your case study.

Once you've completed your case study, it's time to publish and promote it. Some case study formats have pretty obvious promotional outlets — a video case study can go on YouTube, just as an infographic case study can go on Pinterest.

But there are still other ways to publish and promote your case study. Here are a couple of ideas:

Lead Gen in a Blog Post

As stated earlier in this article, written case studies make terrific lead-generators if you convert them into a downloadable format, like a PDF. To generate leads from your case study, consider writing a blog post that tells an abbreviated story of your client's success and asking readers to fill out a form with their name and email address if they'd like to read the rest in your PDF.

Then, promote this blog post on social media, through a Facebook post or a tweet.

Published as a Page on Your Website

As a growing business, you might need to display your case study out in the open to gain the trust of your target audience.

Rather than gating it behind a landing page, publish your case study to its own page on your website, and direct people here from your homepage with a "Case Studies" or "Testimonials" button along your homepage's top navigation bar.

Format for a Case Study

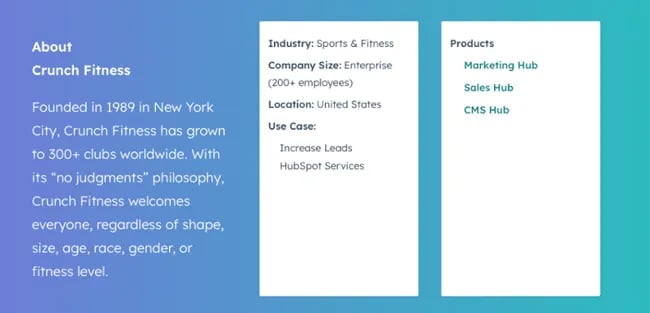

The traditional case study format includes the following parts: a title and subtitle, a client profile, a summary of the customer’s challenges and objectives, an account of how your solution helped, and a description of the results. You might also want to include supporting visuals and quotes, future plans, and calls-to-action.

Image Source

The title is one of the most important parts of your case study. It should draw readers in while succinctly describing the potential benefits of working with your company. To that end, your title should:

- State the name of your custome r. Right away, the reader must learn which company used your products and services. This is especially important if your customer has a recognizable brand. If you work with individuals and not companies, you may omit the name and go with professional titles: “A Marketer…”, “A CFO…”, and so forth.

- State which product your customer used . Even if you only offer one product or service, or if your company name is the same as your product name, you should still include the name of your solution. That way, readers who are not familiar with your business can become aware of what you sell.

- Allude to the results achieved . You don’t necessarily need to provide hard numbers, but the title needs to represent the benefits, quickly. That way, if a reader doesn’t stay to read, they can walk away with the most essential information: Your product works.

The example above, “Crunch Fitness Increases Leads and Signups With HubSpot,” achieves all three — without being wordy. Keeping your title short and sweet is also essential.

2. Subtitle

Your subtitle is another essential part of your case study — don’t skip it, even if you think you’ve done the work with the title. In this section, include a brief summary of the challenges your customer was facing before they began to use your products and services. Then, drive the point home by reiterating the benefits your customer experienced by working with you.

The above example reads:

“Crunch Fitness was franchising rapidly when COVID-19 forced fitness clubs around the world to close their doors. But the company stayed agile by using HubSpot to increase leads and free trial signups.”

We like that the case study team expressed the urgency of the problem — opening more locations in the midst of a pandemic — and placed the focus on the customer’s ability to stay agile.

3. Executive Summary

The executive summary should provide a snapshot of your customer, their challenges, and the benefits they enjoyed from working with you. Think it’s too much? Think again — the purpose of the case study is to emphasize, again and again, how well your product works.

The good news is that depending on your design, the executive summary can be mixed with the subtitle or with the “About the Company” section. Many times, this section doesn’t need an explicit “Executive Summary” subheading. You do need, however, to provide a convenient snapshot for readers to scan.

In the above example, ADP included information about its customer in a scannable bullet-point format, then provided two sections: “Business Challenge” and “How ADP Helped.” We love how simple and easy the format is to follow for those who are unfamiliar with ADP or its typical customer.

4. About the Company

Readers need to know and understand who your customer is. This is important for several reasons: It helps your reader potentially relate to your customer, it defines your ideal client profile (which is essential to deter poor-fit prospects who might have reached out without knowing they were a poor fit), and it gives your customer an indirect boon by subtly promoting their products and services.

Feel free to keep this section as simple as possible. You can simply copy and paste information from the company’s LinkedIn, use a quote directly from your customer, or take a more creative storytelling approach.

In the above example, HubSpot included one paragraph of description for Crunch Fitness and a few bullet points. Below, ADP tells the story of its customer using an engaging, personable technique that effectively draws readers in.

5. Challenges and Objectives

The challenges and objectives section of your case study is the place to lay out, in detail, the difficulties your customer faced prior to working with you — and what they hoped to achieve when they enlisted your help.

In this section, you can be as brief or as descriptive as you’d like, but remember: Stress the urgency of the situation. Don’t understate how much your customer needed your solution (but don’t exaggerate and lie, either). Provide contextual information as necessary. For instance, the pandemic and societal factors may have contributed to the urgency of the need.

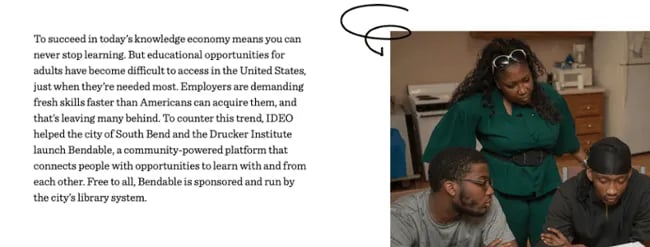

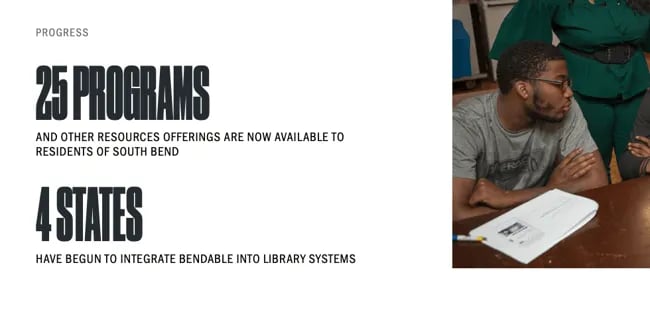

Take the above example from design consultancy IDEO:

“Educational opportunities for adults have become difficult to access in the United States, just when they’re needed most. To counter this trend, IDEO helped the city of South Bend and the Drucker Institute launch Bendable, a community-powered platform that connects people with opportunities to learn with and from each other.”

We love how IDEO mentions the difficulties the United States faces at large, the efforts its customer is taking to address these issues, and the steps IDEO took to help.

6. How Product/Service Helped

This is where you get your product or service to shine. Cover the specific benefits that your customer enjoyed and the features they gleaned the most use out of. You can also go into detail about how you worked with and for your customer. Maybe you met several times before choosing the right solution, or you consulted with external agencies to create the best package for them.

Whatever the case may be, try to illustrate how easy and pain-free it is to work with the representatives at your company. After all, potential customers aren’t looking to just purchase a product. They’re looking for a dependable provider that will strive to exceed their expectations.

In the above example, IDEO describes how it partnered with research institutes and spoke with learners to create Bendable, a free educational platform. We love how it shows its proactivity and thoroughness. It makes potential customers feel that IDEO might do something similar for them.

The results are essential, and the best part is that you don’t need to write the entirety of the case study before sharing them. Like HubSpot, IDEO, and ADP, you can include the results right below the subtitle or executive summary. Use data and numbers to substantiate the success of your efforts, but if you don’t have numbers, you can provide quotes from your customers.

We can’t overstate the importance of the results. In fact, if you wanted to create a short case study, you could include your title, challenge, solution (how your product helped), and result.

8. Supporting Visuals or Quotes

Let your customer speak for themselves by including quotes from the representatives who directly interfaced with your company.

Visuals can also help, even if they’re stock images. On one side, they can help you convey your customer’s industry, and on the other, they can indirectly convey your successes. For instance, a picture of a happy professional — even if they’re not your customer — will communicate that your product can lead to a happy client.

In this example from IDEO, we see a man standing in a boat. IDEO’s customer is neither the man pictured nor the manufacturer of the boat, but rather Conservation International, an environmental organization. This imagery provides a visually pleasing pattern interrupt to the page, while still conveying what the case study is about.

9. Future Plans

This is optional, but including future plans can help you close on a more positive, personable note than if you were to simply include a quote or the results. In this space, you can show that your product will remain in your customer’s tech stack for years to come, or that your services will continue to be instrumental to your customer’s success.

Alternatively, if you work only on time-bound projects, you can allude to the positive impact your customer will continue to see, even after years of the end of the contract.

10. Call to Action (CTA)

Not every case study needs a CTA, but we’d still encourage it. Putting one at the end of your case study will encourage your readers to take an action on your website after learning about the work you've done.

It will also make it easier for them to reach out, if they’re ready to start immediately. You don’t want to lose business just because they have to scroll all the way back up to reach out to your team.

To help you visualize this case study outline, check out the case study template below, which can also be downloaded here .

You drove the results, made the connection, set the expectations, used the questionnaire to conduct a successful interview, and boiled down your findings into a compelling story. And after all of that, you're left with a little piece of sales enabling gold — a case study.

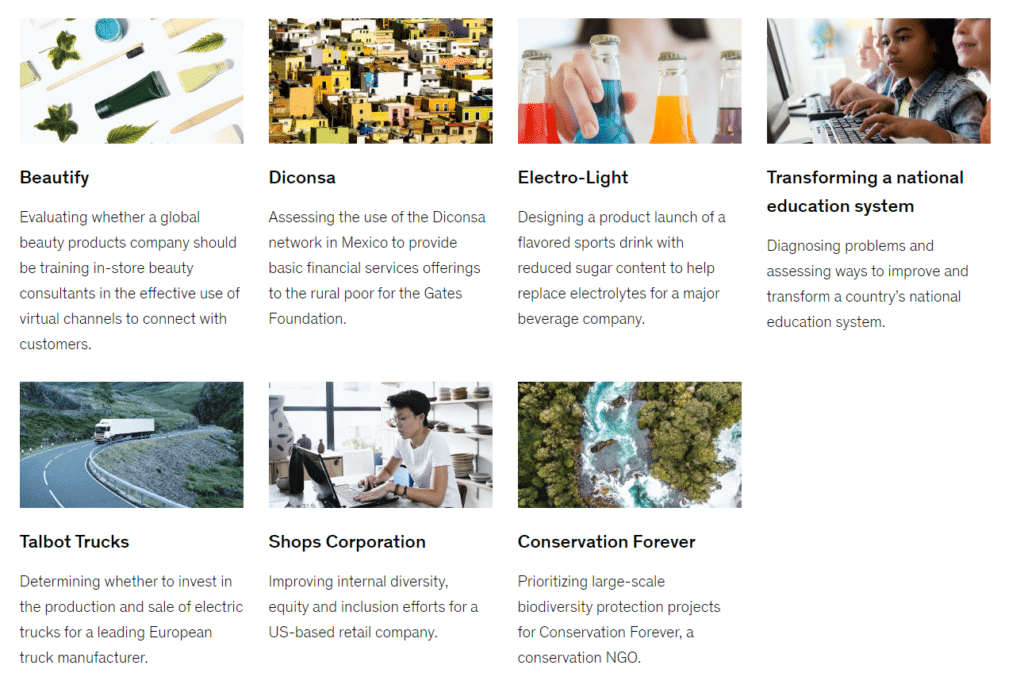

To show you what a well-executed final product looks like, have a look at some of these marketing case study examples.

1. "Shopify Uses HubSpot CRM to Transform High Volume Sales Organization," by HubSpot

What's interesting about this case study is the way it leads with the customer. This reflects a major HubSpot value, which is to always solve for the customer first. The copy leads with a brief description of why Shopify uses HubSpot and is accompanied by a short video and some basic statistics on the company.

Notice that this case study uses mixed media. Yes, there is a short video, but it's elaborated upon in the additional text on the page. So, while case studies can use one or the other, don't be afraid to combine written copy with visuals to emphasize the project's success.

2. "New England Journal of Medicine," by Corey McPherson Nash

When branding and design studio Corey McPherson Nash showcases its work, it makes sense for it to be visual — after all, that's what they do. So in building the case study for the studio's work on the New England Journal of Medicine's integrated advertising campaign — a project that included the goal of promoting the client's digital presence — Corey McPherson Nash showed its audience what it did, rather than purely telling it.

Notice that the case study does include some light written copy — which includes the major points we've suggested — but lets the visuals do the talking, allowing users to really absorb the studio's services.

3. "Designing the Future of Urban Farming," by IDEO

Here's a design company that knows how to lead with simplicity in its case studies. As soon as the visitor arrives at the page, he or she is greeted with a big, bold photo, and two very simple columns of text — "The Challenge" and "The Outcome."

Immediately, IDEO has communicated two of the case study's major pillars. And while that's great — the company created a solution for vertical farming startup INFARM's challenge — it doesn't stop there. As the user scrolls down, those pillars are elaborated upon with comprehensive (but not overwhelming) copy that outlines what that process looked like, replete with quotes and additional visuals.

4. "Secure Wi-Fi Wins Big for Tournament," by WatchGuard

Then, there are the cases when visuals can tell almost the entire story — when executed correctly. Network security provider WatchGuard can do that through this video, which tells the story of how its services enhanced the attendee and vendor experience at the Windmill Ultimate Frisbee tournament.

5. Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Boosts Social Media Engagement and Brand Awareness with HubSpot

In the case study above , HubSpot uses photos, videos, screenshots, and helpful stats to tell the story of how the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame used the bot, CRM, and social media tools to gain brand awareness.

6. Small Desk Plant Business Ups Sales by 30% With Trello

This case study from Trello is straightforward and easy to understand. It begins by explaining the background of the company that decided to use it, what its goals were, and how it planned to use Trello to help them.

It then goes on to discuss how the software was implemented and what tasks and teams benefited from it. Towards the end, it explains the sales results that came from implementing the software and includes quotes from decision-makers at the company that implemented it.

7. Facebook's Mercedes Benz Success Story

Facebook's Success Stories page hosts a number of well-designed and easy-to-understand case studies that visually and editorially get to the bottom line quickly.

Each study begins with key stats that draw the reader in. Then it's organized by highlighting a problem or goal in the introduction, the process the company took to reach its goals, and the results. Then, in the end, Facebook notes the tools used in the case study.

Showcasing Your Work

You work hard at what you do. Now, it's time to show it to the world — and, perhaps more important, to potential customers. Before you show off the projects that make you the proudest, we hope you follow these important steps that will help you effectively communicate that work and leave all parties feeling good about it.

Editor's Note: This blog post was originally published in February 2017 but was updated for comprehensiveness and freshness in July 2021.

Don't forget to share this post!

Related articles.

How to Market an Ebook: 21 Ways to Promote Your Content Offers

![case study beginners guide 7 Pieces of Content Your Audience Really Wants to See [New Data]](https://blog.hubspot.com/hubfs/most%20popular%20types%20of%20content.jpg)

7 Pieces of Content Your Audience Really Wants to See [New Data]

![case study beginners guide How to Write a Listicle [+ Examples and Ideas]](https://blog.hubspot.com/hubfs/listicle-1.jpg)

How to Write a Listicle [+ Examples and Ideas]

28 Case Study Examples Every Marketer Should See

![case study beginners guide What Is a White Paper? [FAQs]](https://blog.hubspot.com/hubfs/business%20whitepaper.jpg)

What Is a White Paper? [FAQs]

What is an Advertorial? 8 Examples to Help You Write One

How to Create Marketing Offers That Don't Fall Flat

20 Creative Ways To Repurpose Content

16 Important Ways to Use Case Studies in Your Marketing

11 Ways to Make Your Blog Post Interactive

Showcase your company's success using these free case study templates.

Marketing software that helps you drive revenue, save time and resources, and measure and optimize your investments — all on one easy-to-use platform

How to write a case study — examples, templates, and tools

It’s a marketer’s job to communicate the effectiveness of a product or service to potential and current customers to convince them to buy and keep business moving. One of the best methods for doing this is to share success stories that are relatable to prospects and customers based on their pain points, experiences, and overall needs.

That’s where case studies come in. Case studies are an essential part of a content marketing plan. These in-depth stories of customer experiences are some of the most effective at demonstrating the value of a product or service. Yet many marketers don’t use them, whether because of their regimented formats or the process of customer involvement and approval.

A case study is a powerful tool for showcasing your hard work and the success your customer achieved. But writing a great case study can be difficult if you’ve never done it before or if it’s been a while. This guide will show you how to write an effective case study and provide real-world examples and templates that will keep readers engaged and support your business.

In this article, you’ll learn:

What is a case study?

How to write a case study, case study templates, case study examples, case study tools.

A case study is the detailed story of a customer’s experience with a product or service that demonstrates their success and often includes measurable outcomes. Case studies are used in a range of fields and for various reasons, from business to academic research. They’re especially impactful in marketing as brands work to convince and convert consumers with relatable, real-world stories of actual customer experiences.

The best case studies tell the story of a customer’s success, including the steps they took, the results they achieved, and the support they received from a brand along the way. To write a great case study, you need to:

- Celebrate the customer and make them — not a product or service — the star of the story.

- Craft the story with specific audiences or target segments in mind so that the story of one customer will be viewed as relatable and actionable for another customer.

- Write copy that is easy to read and engaging so that readers will gain the insights and messages intended.

- Follow a standardized format that includes all of the essentials a potential customer would find interesting and useful.

- Support all of the claims for success made in the story with data in the forms of hard numbers and customer statements.

Case studies are a type of review but more in depth, aiming to show — rather than just tell — the positive experiences that customers have with a brand. Notably, 89% of consumers read reviews before deciding to buy, and 79% view case study content as part of their purchasing process. When it comes to B2B sales, 52% of buyers rank case studies as an important part of their evaluation process.

Telling a brand story through the experience of a tried-and-true customer matters. The story is relatable to potential new customers as they imagine themselves in the shoes of the company or individual featured in the case study. Showcasing previous customers can help new ones see themselves engaging with your brand in the ways that are most meaningful to them.

Besides sharing the perspective of another customer, case studies stand out from other content marketing forms because they are based on evidence. Whether pulling from client testimonials or data-driven results, case studies tend to have more impact on new business because the story contains information that is both objective (data) and subjective (customer experience) — and the brand doesn’t sound too self-promotional.

Case studies are unique in that there’s a fairly standardized format for telling a customer’s story. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t room for creativity. It’s all about making sure that teams are clear on the goals for the case study — along with strategies for supporting content and channels — and understanding how the story fits within the framework of the company’s overall marketing goals.

Here are the basic steps to writing a good case study.

1. Identify your goal

Start by defining exactly who your case study will be designed to help. Case studies are about specific instances where a company works with a customer to achieve a goal. Identify which customers are likely to have these goals, as well as other needs the story should cover to appeal to them.

The answer is often found in one of the buyer personas that have been constructed as part of your larger marketing strategy. This can include anything from new leads generated by the marketing team to long-term customers that are being pressed for cross-sell opportunities. In all of these cases, demonstrating value through a relatable customer success story can be part of the solution to conversion.

2. Choose your client or subject

Who you highlight matters. Case studies tie brands together that might otherwise not cross paths. A writer will want to ensure that the highlighted customer aligns with their own company’s brand identity and offerings. Look for a customer with positive name recognition who has had great success with a product or service and is willing to be an advocate.

The client should also match up with the identified target audience. Whichever company or individual is selected should be a reflection of other potential customers who can see themselves in similar circumstances, having the same problems and possible solutions.

Some of the most compelling case studies feature customers who:

- Switch from one product or service to another while naming competitors that missed the mark.

- Experience measurable results that are relatable to others in a specific industry.

- Represent well-known brands and recognizable names that are likely to compel action.

- Advocate for a product or service as a champion and are well-versed in its advantages.

Whoever or whatever customer is selected, marketers must ensure they have the permission of the company involved before getting started. Some brands have strict review and approval procedures for any official marketing or promotional materials that include their name. Acquiring those approvals in advance will prevent any miscommunication or wasted effort if there is an issue with their legal or compliance teams.

3. Conduct research and compile data

Substantiating the claims made in a case study — either by the marketing team or customers themselves — adds validity to the story. To do this, include data and feedback from the client that defines what success looks like. This can be anything from demonstrating return on investment (ROI) to a specific metric the customer was striving to improve. Case studies should prove how an outcome was achieved and show tangible results that indicate to the customer that your solution is the right one.

This step could also include customer interviews. Make sure that the people being interviewed are key stakeholders in the purchase decision or deployment and use of the product or service that is being highlighted. Content writers should work off a set list of questions prepared in advance. It can be helpful to share these with the interviewees beforehand so they have time to consider and craft their responses. One of the best interview tactics to keep in mind is to ask questions where yes and no are not natural answers. This way, your subject will provide more open-ended responses that produce more meaningful content.

4. Choose the right format

There are a number of different ways to format a case study. Depending on what you hope to achieve, one style will be better than another. However, there are some common elements to include, such as:

- An engaging headline

- A subject and customer introduction

- The unique challenge or challenges the customer faced

- The solution the customer used to solve the problem

- The results achieved

- Data and statistics to back up claims of success

- A strong call to action (CTA) to engage with the vendor

It’s also important to note that while case studies are traditionally written as stories, they don’t have to be in a written format. Some companies choose to get more creative with their case studies and produce multimedia content, depending on their audience and objectives. Case study formats can include traditional print stories, interactive web or social content, data-heavy infographics, professionally shot videos, podcasts, and more.

5. Write your case study

We’ll go into more detail later about how exactly to write a case study, including templates and examples. Generally speaking, though, there are a few things to keep in mind when writing your case study.

- Be clear and concise. Readers want to get to the point of the story quickly and easily, and they’ll be looking to see themselves reflected in the story right from the start.

- Provide a big picture. Always make sure to explain who the client is, their goals, and how they achieved success in a short introduction to engage the reader.

- Construct a clear narrative. Stick to the story from the perspective of the customer and what they needed to solve instead of just listing product features or benefits.

- Leverage graphics. Incorporating infographics, charts, and sidebars can be a more engaging and eye-catching way to share key statistics and data in readable ways.

- Offer the right amount of detail. Most case studies are one or two pages with clear sections that a reader can skim to find the information most important to them.

- Include data to support claims. Show real results — both facts and figures and customer quotes — to demonstrate credibility and prove the solution works.

6. Promote your story

Marketers have a number of options for distribution of a freshly minted case study. Many brands choose to publish case studies on their website and post them on social media. This can help support SEO and organic content strategies while also boosting company credibility and trust as visitors see that other businesses have used the product or service.

Marketers are always looking for quality content they can use for lead generation. Consider offering a case study as gated content behind a form on a landing page or as an offer in an email message. One great way to do this is to summarize the content and tease the full story available for download after the user takes an action.

Sales teams can also leverage case studies, so be sure they are aware that the assets exist once they’re published. Especially when it comes to larger B2B sales, companies often ask for examples of similar customer challenges that have been solved.

Now that you’ve learned a bit about case studies and what they should include, you may be wondering how to start creating great customer story content. Here are a couple of templates you can use to structure your case study.

Template 1 — Challenge-solution-result format

- Start with an engaging title. This should be fewer than 70 characters long for SEO best practices. One of the best ways to approach the title is to include the customer’s name and a hint at the challenge they overcame in the end.

- Create an introduction. Lead with an explanation as to who the customer is, the need they had, and the opportunity they found with a specific product or solution. Writers can also suggest the success the customer experienced with the solution they chose.

- Present the challenge. This should be several paragraphs long and explain the problem the customer faced and the issues they were trying to solve. Details should tie into the company’s products and services naturally. This section needs to be the most relatable to the reader so they can picture themselves in a similar situation.

- Share the solution. Explain which product or service offered was the ideal fit for the customer and why. Feel free to delve into their experience setting up, purchasing, and onboarding the solution.

- Explain the results. Demonstrate the impact of the solution they chose by backing up their positive experience with data. Fill in with customer quotes and tangible, measurable results that show the effect of their choice.

- Ask for action. Include a CTA at the end of the case study that invites readers to reach out for more information, try a demo, or learn more — to nurture them further in the marketing pipeline. What you ask of the reader should tie directly into the goals that were established for the case study in the first place.

Template 2 — Data-driven format

- Start with an engaging title. Be sure to include a statistic or data point in the first 70 characters. Again, it’s best to include the customer’s name as part of the title.

- Create an overview. Share the customer’s background and a short version of the challenge they faced. Present the reason a particular product or service was chosen, and feel free to include quotes from the customer about their selection process.

- Present data point 1. Isolate the first metric that the customer used to define success and explain how the product or solution helped to achieve this goal. Provide data points and quotes to substantiate the claim that success was achieved.

- Present data point 2. Isolate the second metric that the customer used to define success and explain what the product or solution did to achieve this goal. Provide data points and quotes to substantiate the claim that success was achieved.

- Present data point 3. Isolate the final metric that the customer used to define success and explain what the product or solution did to achieve this goal. Provide data points and quotes to substantiate the claim that success was achieved.

- Summarize the results. Reiterate the fact that the customer was able to achieve success thanks to a specific product or service. Include quotes and statements that reflect customer satisfaction and suggest they plan to continue using the solution.

- Ask for action. Include a CTA at the end of the case study that asks readers to reach out for more information, try a demo, or learn more — to further nurture them in the marketing pipeline. Again, remember that this is where marketers can look to convert their content into action with the customer.

While templates are helpful, seeing a case study in action can also be a great way to learn. Here are some examples of how Adobe customers have experienced success.

Juniper Networks

One example is the Adobe and Juniper Networks case study , which puts the reader in the customer’s shoes. The beginning of the story quickly orients the reader so that they know exactly who the article is about and what they were trying to achieve. Solutions are outlined in a way that shows Adobe Experience Manager is the best choice and a natural fit for the customer. Along the way, quotes from the client are incorporated to help add validity to the statements. The results in the case study are conveyed with clear evidence of scale and volume using tangible data.

The story of Lenovo’s journey with Adobe is one that spans years of planning, implementation, and rollout. The Lenovo case study does a great job of consolidating all of this into a relatable journey that other enterprise organizations can see themselves taking, despite the project size. This case study also features descriptive headers and compelling visual elements that engage the reader and strengthen the content.

Tata Consulting

When it comes to using data to show customer results, this case study does an excellent job of conveying details and numbers in an easy-to-digest manner. Bullet points at the start break up the content while also helping the reader understand exactly what the case study will be about. Tata Consulting used Adobe to deliver elevated, engaging content experiences for a large telecommunications client of its own — an objective that’s relatable for a lot of companies.

Case studies are a vital tool for any marketing team as they enable you to demonstrate the value of your company’s products and services to others. They help marketers do their job and add credibility to a brand trying to promote its solutions by using the experiences and stories of real customers.

When you’re ready to get started with a case study:

- Think about a few goals you’d like to accomplish with your content.

- Make a list of successful clients that would be strong candidates for a case study.

- Reach out to the client to get their approval and conduct an interview.

- Gather the data to present an engaging and effective customer story.

Adobe can help

There are several Adobe products that can help you craft compelling case studies. Adobe Experience Platform helps you collect data and deliver great customer experiences across every channel. Once you’ve created your case studies, Experience Platform will help you deliver the right information to the right customer at the right time for maximum impact.

To learn more, watch the Adobe Experience Platform story .

Keep in mind that the best case studies are backed by data. That’s where Adobe Real-Time Customer Data Platform and Adobe Analytics come into play. With Real-Time CDP, you can gather the data you need to build a great case study and target specific customers to deliver the content to the right audience at the perfect moment.

Watch the Real-Time CDP overview video to learn more.

Finally, Adobe Analytics turns real-time data into real-time insights. It helps your business collect and synthesize data from multiple platforms to make more informed decisions and create the best case study possible.

Request a demo to learn more about Adobe Analytics.

https://business.adobe.com/blog/perspectives/b2b-ecommerce-10-case-studies-inspire-you

https://business.adobe.com/blog/basics/business-case

https://business.adobe.com/blog/basics/what-is-real-time-analytics

How To Write A Consulting Case Study: Guide, Template, & Examples

When you deliver a successful project, do you publish a consulting case study about it?

A consulting case study is a short story about a successful project that explains…

- The problem your client was dealing with before hiring you;

- your expertise and process for solving that problem;

- and the results your expertise and process created for the client and their business.

In my experience, our consulting case studies are among the most powerful pieces of content we publish. They’re a big reason why people are comfortable signing up for our Clarity Coaching Program .

Because our case studies prove our program helps our clients get results.

I can say that our coaching program is the best on the market until I’m blue in the face.

But it’s much more powerful for consultants to see the results others have experienced for themselves: through our case studies and testimonials.

If you don’t have something of value on your website like a case study — something that actually shows you can achieve results for your clients — then your website will only serve as “confirmational marketing.”

It will confirm what people hear about you. But it won’t help you generate interest and leads.

So, if you want to shift your website beyond mere confirmational marketing to an asset that helps you generate leads and conversions, consider writing consulting case studies using the method below.

In this article, you’ll learn how to write compelling case studies that help you win more consulting clients.

Ready? Let’s dive in…

Your case study is proof that not only can you talk the talk, but you can also walk the walk.

What Is A Consulting Case Study?

When a potential client is deciding on whether they will hire you or not, a big question in their mind is…

“Can this person or company really do what they say they can for my business?”

There are many forms of thought leadership you can use to prove you can deliver results.

The consulting case study is one of them.

A case study, in the context of consulting, is typically a written document that describes…

- the problem a client was facing,

- the actions you took to solve that problem,

- and the outcomes it created for your client.

You write case studies to demonstrate the results and value you created for a past or current client.

What makes them so effective as marketing material?

- They are relatively easy to put together (especially when you use our template below).

- Your potential clients enjoy reading them.

- And they are a highly effective way to demonstrate your authority and expertise in your field.

Next, I’ll walk you through how to write a consulting case study.

In our program, one of the things we teach consultants is how to better understand their clients’ problems and articulate their ability to solve those problems in a way that will attract new clients.

How To Write A Consulting Case Study

Here are the steps to writing your consulting case study. You can follow along with our consulting case study template .

1. Get Permission From The Client

You shouldn’t write a case study that names your client without their permission.

So, before you start writing it, ask them if they’d be OK with you publishing a case study about the project.

Now, I’m not a lawyer, and nothing in this article or anything I write is legal or financial advice. But here’s what we’ve found, through running consulting businesses for over two decades, often works best:

A question we often receive from consultants is “What if I can’t use the name of my client or the company I worked with?” Generally, this isn’t an issue. If your contract says you can’t use the client’s company name, or the client says “No” to your request, all is not lost.

What tends to work extremely well is still writing the case study, but without using the client’s name. Instead, describe the client.

For example, let’s say your client is the automaker Mazda. If you can’t use their name, consider “Working with a top 20 global automaker…”

This gives prospective buyers a good idea of the caliber and type of company you worked with.

When you ask your client for their permission to create a case study that features them, you’ll generally find that 9 times out of 10 they won’t have a problem with you doing so, but make sure you ask before publishing.

2. Introduce The Client’s Business

Once you’ve gotten permission from the client, you’ll begin writing your case study. Follow along using our template .

The first section is the introduction. Set the stage here by introducing your client, their business, and their industry.

This section gives context to the case study. Ideally, your ideal client is intrigued by being in a similar industry or situation as the client in your case study.

3. Describe The Problem Or Challenge

In this section, you outline the problem your client was facing.

Be as specific as you can be.

Simply saying they had marketing issues or a problem with their PR is not enough.

The more detail you include the clearer the picture will become and the more effective your case study copywriting will be.

If your ideal client reads this and has a similar problem as the client in the case study, you can guarantee that their eyes will be glued to the screen, salivating to learn how you solved it.

4. Summarize Your Action Steps

Now that you’ve described the problem your client was up against, you’ll explain what you did to help solve the problem.

In this section, break down each part of the process you used or the steps you took to solve it.

The reader should get the sense that you have a process or system capable of solving the problem and getting results.

This is where you get to demonstrate your know-how and expertise. Get as technical as you can. Show your reader “Hey, this is how I can get YOU results too.”

5. Share The Results

It’s time to demonstrate results.

Write the results that were achieved and how they impacted the business/organization/person.

In many cases, the outcome isn’t just dollars and cents — it can also be less tangible value.

Are they less stressed? Do they have more free time? Are they finding more meaning and enjoyment in their work?

Mention if you’re continuing to work with this client through a retainer . If you’re not, describe how the results will impact their business in the future.

This is also a great place to include a quote or testimonial from your client.

The “Results” section is key because it shows prospective clients that you’ve solved the problems they are facing and have delivered the actual results that they likely desire.

6. Write A Call To Action

At the end of the case study, you should always include a sentence or two inviting the ideal client to reach out.

They’ve just read about the problems you can solve, how you solve them, and the results you can create.

They are primed and ready to reach out to inquire about how you can do it for them.

But if you don’t have a direct call to action for them to do that, many of them will leave without taking action.

So, write a direct, clear call to action that takes them to a page where it’s easy to book a consultation with you or where you provide your contact information.

7. Share It

Marketing for consultants is all about providing value to your ideal clients, being known for something specific, and positioning yourself as an expert and authority that your ideal clients want to work with. So, whenever you publish a piece of valuable content like a case study, your mission is to get as many eyes on the case study as possible.

The best place to publish your case study is on your website or blog.

You can also submit case studies to industry publications. These are a great way to spread the word about you and your client’s business.

Make sure to also share your case study on all social media platforms where your ideal clients hang out online. For consultants, that means LinkedIn.

Work your “marketing muscle” by actively promoting your case study, and you’ll reap the rewards of this powerful piece of authority-building content.

Writing case studies for your consulting business not only helps you land new clients, but it’s also a great way for you to review past projects.

Doing this helps you to find what worked and what didn’t.

And you’ll continue to learn from your experiences and implement your best practices into your next consulting project.

Consulting Case Study Template

Click here to access our Consulting Case Study Template .

This template is designed using a “fill in the blank” style to make it easy for you to put together your case studies.

Save this template for yourself. Use it to follow along with the examples below.

Consulting Case Study Examples

Here are some example case studies from our Clarity Coaching Program clients.

1. Larissa Stoddart

Larissa Stoddart teaches charities and nonprofits how to raise money.

To do that, she provides her clients with a training and coaching program that walks them through twelve modules of content on raising money for their organization, creating a fundraising plan, putting an information management system into place, finding prospects, and asking those prospects for money.

Through her case studies, Larissa provides a comprehensive overview of how she helps her clients build robust fundraising plans and achieve and win more donations.

2. Dan Burgos

Danila “Dan” Burgos is the president and CEO of Alphanova Consulting, which works with US manufacturers to help them increase their profitability through operational improvements.

The goal of Alphanova is to increase their clients’ quality and on-time delivery by 99 percent and help them increase their net profits by over 25 percent.

Through his case studies, Dan lays out the problem, his solution, and the results in a clear simple way.

He makes it very easy for his prospects to envision working with his firm — and then schedule a consultation to make it happen.

3. Vanessa Bennet

Through her company Next Evolution Performance, Vanessa Bennett and her business partner Alex Davides, use neuroscience to help driven business leaders improve their productivity, energy, profitability, and staff retention, while avoiding burnout.

Through her “Clients” page, she provides a list of the specific industries she works with as well as specific case studies from clients within those industries.

She then displays in-depth testimonials that detail the results that her consulting services create for her clients.

These are powerful stories that help Vanessa’s clients see their desired future state — and how her firm is the right choice to help them get there.

As you see, our clients have taken our template and made them work for their unique style, clients, and services.

I encourage you to do the same.

And if you’d benefit from personal, 1-on-1 coaching and support from like-minded consultants, check out our Clarity Coaching Program .

Get Help & Feedback Writing Consulting Case Studies

If writing and demonstrating your authority were easy, then every consultant would be publishing case studies.

But that’s not the case.

Sometimes it helps to have a consulting coach to walk you through each step — and a community of like-minded consultants with whom you can share your work and get feedback from.

That’s why we’ve built the Clarity Coaching Program.

Inside the program, we teach you how to write case studies (among dozens of other critical subjects for consulting business founders).

And we’ve also created a network of coaches and other consultants who are in the trenches — and who are willing to share their hard-fought knowledge with you.

Inside the Clarity Coaching program , we’ve helped over 850 consultants to build a more strategic, profitable, and scalable, consulting business.

Learn More About Clarity Coaching

We’ll work hands-on with you to develop a strategic plan and then dive deep and work through your ideal client clarity, strategic messaging, consulting offers, use an effective and proven consulting pricing strategy, help you to increase your fees, business model optimization, and help you to set up your marketing engine and lead generation system to consistently attract ideal clients.

15 thoughts on “ How To Write A Consulting Case Study: Guide, Template, & Examples ”

This is a great outline and I found it quite helpful. Thanks.

Shana – glad you found this post helpful!

I have used case studies to get new clients and you're right, They work.

Jay – thanks for sharing. I've worked with many clients to implement case studies and have used them in several businesses and have always found them to be great at supporting proof and establishing authority and credibility.

Dumb question: guess you can't charge if you're doing a case study, huh?

Terri – No such thing as a dumb question where I come from. Always good to ask.

You definitely can charge for case studies. Michael Stelzner has a lot more information on writing white papers (and case studies) as projects.

This post was really aimed at using case studies to win more business and attract clients. But you can definitely offer this service to companies and they'll pay handsomely for it.

That was a great question!

Hello,I am really glad I stumbled upon your consulting site. This outline is very helpful and I love the e-mails I recieve as well Thanks!

Happy to hear that

This is a great site for consultants – great information for the team to share with consultants that reach out to us. Thank you!

Thanks Deborah

It is a good steps if we know how we start and control our working.

All I wanted to know about putting together a case study I have got. Thanks so much.

to put together your consulting case study: to put together your consulting case study:

I have used your outline today to write one case. Thank you for sharing.

Hi – This is a great piece, and covers all the core elements of a case study with impact.

Couple of extra points…

1. it’s really powerful to provide a mix of qualitative and quantitative results where possible e.g. ‘we saved the client $500 per month and feedback tells us morale improved’

2. We are seeing more and more consultancies include images and video in their case studies. This obviously depends on the context, so while it’s not necessarily appropriate within the confines of a bid, it is definitely something to think about for those case studies that you want to publish online or in a marketing brochure.

Leave a Comment, Join the Conversation! Cancel reply

Your Email will be kept private and will not be shown publicly.

Privacy Overview

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is a Case Study?

Weighing the pros and cons of this method of research

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Cara Lustik is a fact-checker and copywriter.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Cara-Lustik-1000-77abe13cf6c14a34a58c2a0ffb7297da.jpg)

Verywell / Colleen Tighe

- Pros and Cons

What Types of Case Studies Are Out There?

Where do you find data for a case study, how do i write a psychology case study.

A case study is an in-depth study of one person, group, or event. In a case study, nearly every aspect of the subject's life and history is analyzed to seek patterns and causes of behavior. Case studies can be used in many different fields, including psychology, medicine, education, anthropology, political science, and social work.

The point of a case study is to learn as much as possible about an individual or group so that the information can be generalized to many others. Unfortunately, case studies tend to be highly subjective, and it is sometimes difficult to generalize results to a larger population.

While case studies focus on a single individual or group, they follow a format similar to other types of psychology writing. If you are writing a case study, we got you—here are some rules of APA format to reference.

At a Glance

A case study, or an in-depth study of a person, group, or event, can be a useful research tool when used wisely. In many cases, case studies are best used in situations where it would be difficult or impossible for you to conduct an experiment. They are helpful for looking at unique situations and allow researchers to gather a lot of˜ information about a specific individual or group of people. However, it's important to be cautious of any bias we draw from them as they are highly subjective.

What Are the Benefits and Limitations of Case Studies?

A case study can have its strengths and weaknesses. Researchers must consider these pros and cons before deciding if this type of study is appropriate for their needs.

One of the greatest advantages of a case study is that it allows researchers to investigate things that are often difficult or impossible to replicate in a lab. Some other benefits of a case study:

- Allows researchers to capture information on the 'how,' 'what,' and 'why,' of something that's implemented

- Gives researchers the chance to collect information on why one strategy might be chosen over another

- Permits researchers to develop hypotheses that can be explored in experimental research

On the other hand, a case study can have some drawbacks:

- It cannot necessarily be generalized to the larger population

- Cannot demonstrate cause and effect