- Search Menu

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Reasons to Submit

- About Journal of Surgical Protocols and Research Methodologies

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, contents of a research study protocol, conflict of interest statement, how to write a research study protocol.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Julien Al Shakarchi, How to write a research study protocol, Journal of Surgical Protocols and Research Methodologies , Volume 2022, Issue 1, January 2022, snab008, https://doi.org/10.1093/jsprm/snab008

- Permissions Icon Permissions

A study protocol is an important document that specifies the research plan for a clinical study. Many funders such as the NHS Health Research Authority encourage researchers to publish their study protocols to create a record of the methodology and reduce duplication of research effort. In this paper, we will describe how to write a research study protocol.

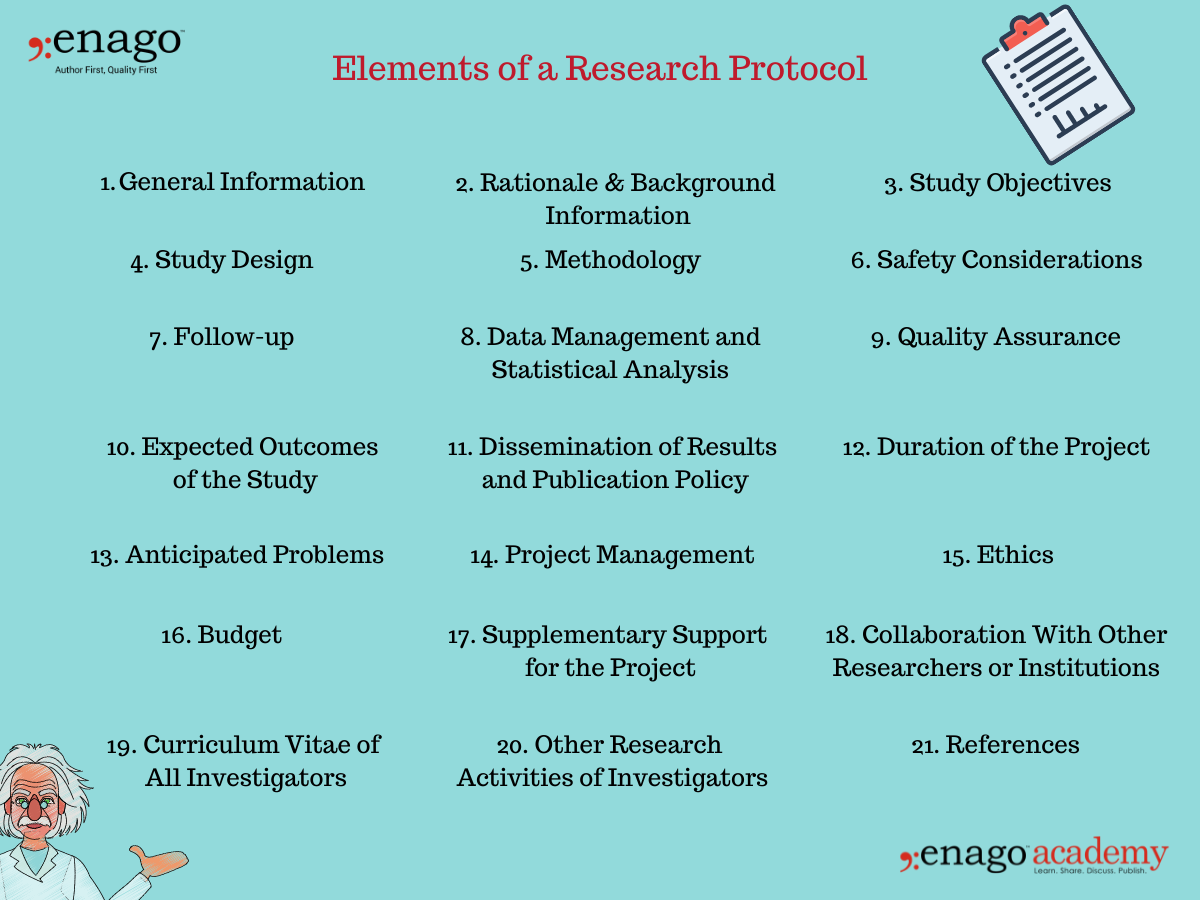

A study protocol is an essential part of a research project. It describes the study in detail to allow all members of the team to know and adhere to the steps of the methodology. Most funders, such as the NHS Health Research Authority in the United Kingdom, encourage researchers to publish their study protocols to create a record of the methodology, help with publication of the study and reduce duplication of research effort. In this paper, we will explain how to write a research protocol by describing what should be included.

Introduction

The introduction is vital in setting the need for the planned research and the context of the current evidence. It should be supported by a background to the topic with appropriate references to the literature. A thorough review of the available evidence is expected to document the need for the planned research. This should be followed by a brief description of the study and the target population. A clear explanation for the rationale of the project is also expected to describe the research question and justify the need of the study.

Methods and analysis

A suitable study design and methodology should be chosen to reflect the aims of the research. This section should explain the study design: single centre or multicentre, retrospective or prospective, controlled or uncontrolled, randomised or not, and observational or experimental. Efforts should be made to explain why that particular design has been chosen. The studied population should be clearly defined with inclusion and exclusion criteria. These criteria will define the characteristics of the population the study is proposing to investigate and therefore outline the applicability to the reader. The size of the sample should be calculated with a power calculation if possible.

The protocol should describe the screening process about how, when and where patients will be recruited in the process. In the setting of a multicentre study, each participating unit should adhere to the same recruiting model or the differences should be described in the protocol. Informed consent must be obtained prior to any individual participating in the study. The protocol should fully describe the process of gaining informed consent that should include a patient information sheet and assessment of his or her capacity.

The intervention should be described in sufficient detail to allow an external individual or group to replicate the study. The differences in any changes of routine care should be explained. The primary and secondary outcomes should be clearly defined and an explanation of their clinical relevance is recommended. Data collection methods should be described in detail as well as where the data will be kept secured. Analysis of the data should be explained with clear statistical methods. There should also be plans on how any reported adverse events and other unintended effects of trial interventions or trial conduct will be reported, collected and managed.

Ethics and dissemination

A clear explanation of the risk and benefits to the participants should be included as well as addressing any specific ethical considerations. The protocol should clearly state the approvals the research has gained and the minimum expected would be ethical and local research approvals. For multicentre studies, the protocol should also include a statement of how the protocol is in line with requirements to gain approval to conduct the study at each proposed sites.

It is essential to comment on how personal information about potential and enrolled participants will be collected, shared and maintained in order to protect confidentiality. This part of the protocol should also state who owns the data arising from the study and for how long the data will be stored. It should explain that on completion of the study, the data will be analysed and a final study report will be written. We would advise to explain if there are any plans to notify the participants of the outcome of the study, either by provision of the publication or via another form of communication.

The authorship of any publication should have transparent and fair criteria, which should be described in this section of the protocol. By doing so, it will resolve any issues arising at the publication stage.

Funding statement

It is important to explain who are the sponsors and funders of the study. It should clarify the involvement and potential influence of any party. The sponsor is defined as the institution or organisation assuming overall responsibility for the study. Identification of the study sponsor provides transparency and accountability. The protocol should explicitly outline the roles and responsibilities of any funder(s) in study design, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing and dissemination of results. Any competing interests of the investigators should also be stated in this section.

A study protocol is an important document that specifies the research plan for a clinical study. It should be written in detail and researchers should aim to publish their study protocols as it is encouraged by many funders. The spirit 2013 statement provides a useful checklist on what should be included in a research protocol [ 1 ]. In this paper, we have explained a straightforward approach to writing a research study protocol.

None declared.

Chan A-W , Tetzlaff JM , Gøtzsche PC , Altman DG , Mann H , Berlin J , et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials . BMJ 2013 ; 346 : e7586 .

Google Scholar

- conflict of interest

- national health service (uk)

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- JSPRM Twitter

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 2752-616X

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press and JSCR Publishing Ltd

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, developing a robust case study protocol.

Management Research Review

ISSN : 2040-8269

Article publication date: 4 July 2023

Issue publication date: 11 January 2024

Case study research has been applied across numerous fields and provides an established methodology for exploring and understanding various research contexts. This paper aims to aid in developing methodological rigor by investigating the approaches of establishing validity and reliability.

Design/methodology/approach

Based on a systematic review of relevant literature, this paper catalogs the use of validity and reliability measures within academic publications between 2008 and 2018. The review analyzes case study research across 15 peer-reviewed journals (total of 1,372 articles) and highlights the application of validity and reliability measures.

The evidence of the systematic literature review suggests that validity measures appear well established and widely reported within case study–based research articles. However, measures and test procedures related to research reliability appear underrepresented within analyzed articles.

Originality/value

As shown by the presented results, there is a need for more significant reporting of the procedures used related to research reliability. Toward this, the features of a robust case study protocol are defined and discussed.

- Case study research

- Systematic literature review

Burnard, K.J. (2024), "Developing a robust case study protocol", Management Research Review , Vol. 47 No. 2, pp. 204-225. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-11-2021-0821

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2023, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

A case study research paper examines a person, place, event, condition, phenomenon, or other type of subject of analysis in order to extrapolate key themes and results that help predict future trends, illuminate previously hidden issues that can be applied to practice, and/or provide a means for understanding an important research problem with greater clarity. A case study research paper usually examines a single subject of analysis, but case study papers can also be designed as a comparative investigation that shows relationships between two or more subjects. The methods used to study a case can rest within a quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-method investigative paradigm.

Case Studies. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010 ; “What is a Case Study?” In Swanborn, Peter G. Case Study Research: What, Why and How? London: SAGE, 2010.

How to Approach Writing a Case Study Research Paper

General information about how to choose a topic to investigate can be found under the " Choosing a Research Problem " tab in the Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper writing guide. Review this page because it may help you identify a subject of analysis that can be investigated using a case study design.

However, identifying a case to investigate involves more than choosing the research problem . A case study encompasses a problem contextualized around the application of in-depth analysis, interpretation, and discussion, often resulting in specific recommendations for action or for improving existing conditions. As Seawright and Gerring note, practical considerations such as time and access to information can influence case selection, but these issues should not be the sole factors used in describing the methodological justification for identifying a particular case to study. Given this, selecting a case includes considering the following:

- The case represents an unusual or atypical example of a research problem that requires more in-depth analysis? Cases often represent a topic that rests on the fringes of prior investigations because the case may provide new ways of understanding the research problem. For example, if the research problem is to identify strategies to improve policies that support girl's access to secondary education in predominantly Muslim nations, you could consider using Azerbaijan as a case study rather than selecting a more obvious nation in the Middle East. Doing so may reveal important new insights into recommending how governments in other predominantly Muslim nations can formulate policies that support improved access to education for girls.

- The case provides important insight or illuminate a previously hidden problem? In-depth analysis of a case can be based on the hypothesis that the case study will reveal trends or issues that have not been exposed in prior research or will reveal new and important implications for practice. For example, anecdotal evidence may suggest drug use among homeless veterans is related to their patterns of travel throughout the day. Assuming prior studies have not looked at individual travel choices as a way to study access to illicit drug use, a case study that observes a homeless veteran could reveal how issues of personal mobility choices facilitate regular access to illicit drugs. Note that it is important to conduct a thorough literature review to ensure that your assumption about the need to reveal new insights or previously hidden problems is valid and evidence-based.

- The case challenges and offers a counter-point to prevailing assumptions? Over time, research on any given topic can fall into a trap of developing assumptions based on outdated studies that are still applied to new or changing conditions or the idea that something should simply be accepted as "common sense," even though the issue has not been thoroughly tested in current practice. A case study analysis may offer an opportunity to gather evidence that challenges prevailing assumptions about a research problem and provide a new set of recommendations applied to practice that have not been tested previously. For example, perhaps there has been a long practice among scholars to apply a particular theory in explaining the relationship between two subjects of analysis. Your case could challenge this assumption by applying an innovative theoretical framework [perhaps borrowed from another discipline] to explore whether this approach offers new ways of understanding the research problem. Taking a contrarian stance is one of the most important ways that new knowledge and understanding develops from existing literature.

- The case provides an opportunity to pursue action leading to the resolution of a problem? Another way to think about choosing a case to study is to consider how the results from investigating a particular case may result in findings that reveal ways in which to resolve an existing or emerging problem. For example, studying the case of an unforeseen incident, such as a fatal accident at a railroad crossing, can reveal hidden issues that could be applied to preventative measures that contribute to reducing the chance of accidents in the future. In this example, a case study investigating the accident could lead to a better understanding of where to strategically locate additional signals at other railroad crossings so as to better warn drivers of an approaching train, particularly when visibility is hindered by heavy rain, fog, or at night.

- The case offers a new direction in future research? A case study can be used as a tool for an exploratory investigation that highlights the need for further research about the problem. A case can be used when there are few studies that help predict an outcome or that establish a clear understanding about how best to proceed in addressing a problem. For example, after conducting a thorough literature review [very important!], you discover that little research exists showing the ways in which women contribute to promoting water conservation in rural communities of east central Africa. A case study of how women contribute to saving water in a rural village of Uganda can lay the foundation for understanding the need for more thorough research that documents how women in their roles as cooks and family caregivers think about water as a valuable resource within their community. This example of a case study could also point to the need for scholars to build new theoretical frameworks around the topic [e.g., applying feminist theories of work and family to the issue of water conservation].

Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. “Building Theories from Case Study Research.” Academy of Management Review 14 (October 1989): 532-550; Emmel, Nick. Sampling and Choosing Cases in Qualitative Research: A Realist Approach . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2013; Gerring, John. “What Is a Case Study and What Is It Good for?” American Political Science Review 98 (May 2004): 341-354; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Seawright, Jason and John Gerring. "Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research." Political Research Quarterly 61 (June 2008): 294-308.

Structure and Writing Style

The purpose of a paper in the social sciences designed around a case study is to thoroughly investigate a subject of analysis in order to reveal a new understanding about the research problem and, in so doing, contributing new knowledge to what is already known from previous studies. In applied social sciences disciplines [e.g., education, social work, public administration, etc.], case studies may also be used to reveal best practices, highlight key programs, or investigate interesting aspects of professional work.

In general, the structure of a case study research paper is not all that different from a standard college-level research paper. However, there are subtle differences you should be aware of. Here are the key elements to organizing and writing a case study research paper.

I. Introduction

As with any research paper, your introduction should serve as a roadmap for your readers to ascertain the scope and purpose of your study . The introduction to a case study research paper, however, should not only describe the research problem and its significance, but you should also succinctly describe why the case is being used and how it relates to addressing the problem. The two elements should be linked. With this in mind, a good introduction answers these four questions:

- What is being studied? Describe the research problem and describe the subject of analysis [the case] you have chosen to address the problem. Explain how they are linked and what elements of the case will help to expand knowledge and understanding about the problem.

- Why is this topic important to investigate? Describe the significance of the research problem and state why a case study design and the subject of analysis that the paper is designed around is appropriate in addressing the problem.

- What did we know about this topic before I did this study? Provide background that helps lead the reader into the more in-depth literature review to follow. If applicable, summarize prior case study research applied to the research problem and why it fails to adequately address the problem. Describe why your case will be useful. If no prior case studies have been used to address the research problem, explain why you have selected this subject of analysis.

- How will this study advance new knowledge or new ways of understanding? Explain why your case study will be suitable in helping to expand knowledge and understanding about the research problem.

Each of these questions should be addressed in no more than a few paragraphs. Exceptions to this can be when you are addressing a complex research problem or subject of analysis that requires more in-depth background information.

II. Literature Review

The literature review for a case study research paper is generally structured the same as it is for any college-level research paper. The difference, however, is that the literature review is focused on providing background information and enabling historical interpretation of the subject of analysis in relation to the research problem the case is intended to address . This includes synthesizing studies that help to:

- Place relevant works in the context of their contribution to understanding the case study being investigated . This would involve summarizing studies that have used a similar subject of analysis to investigate the research problem. If there is literature using the same or a very similar case to study, you need to explain why duplicating past research is important [e.g., conditions have changed; prior studies were conducted long ago, etc.].

- Describe the relationship each work has to the others under consideration that informs the reader why this case is applicable . Your literature review should include a description of any works that support using the case to investigate the research problem and the underlying research questions.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research using the case study . If applicable, review any research that has examined the research problem using a different research design. Explain how your use of a case study design may reveal new knowledge or a new perspective or that can redirect research in an important new direction.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies . This refers to synthesizing any literature that points to unresolved issues of concern about the research problem and describing how the subject of analysis that forms the case study can help resolve these existing contradictions.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research . Your review should examine any literature that lays a foundation for understanding why your case study design and the subject of analysis around which you have designed your study may reveal a new way of approaching the research problem or offer a perspective that points to the need for additional research.

- Expose any gaps that exist in the literature that the case study could help to fill . Summarize any literature that not only shows how your subject of analysis contributes to understanding the research problem, but how your case contributes to a new way of understanding the problem that prior research has failed to do.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important!] . Collectively, your literature review should always place your case study within the larger domain of prior research about the problem. The overarching purpose of reviewing pertinent literature in a case study paper is to demonstrate that you have thoroughly identified and synthesized prior studies in relation to explaining the relevance of the case in addressing the research problem.

III. Method

In this section, you explain why you selected a particular case [i.e., subject of analysis] and the strategy you used to identify and ultimately decide that your case was appropriate in addressing the research problem. The way you describe the methods used varies depending on the type of subject of analysis that constitutes your case study.

If your subject of analysis is an incident or event . In the social and behavioral sciences, the event or incident that represents the case to be studied is usually bounded by time and place, with a clear beginning and end and with an identifiable location or position relative to its surroundings. The subject of analysis can be a rare or critical event or it can focus on a typical or regular event. The purpose of studying a rare event is to illuminate new ways of thinking about the broader research problem or to test a hypothesis. Critical incident case studies must describe the method by which you identified the event and explain the process by which you determined the validity of this case to inform broader perspectives about the research problem or to reveal new findings. However, the event does not have to be a rare or uniquely significant to support new thinking about the research problem or to challenge an existing hypothesis. For example, Walo, Bull, and Breen conducted a case study to identify and evaluate the direct and indirect economic benefits and costs of a local sports event in the City of Lismore, New South Wales, Australia. The purpose of their study was to provide new insights from measuring the impact of a typical local sports event that prior studies could not measure well because they focused on large "mega-events." Whether the event is rare or not, the methods section should include an explanation of the following characteristics of the event: a) when did it take place; b) what were the underlying circumstances leading to the event; and, c) what were the consequences of the event in relation to the research problem.

If your subject of analysis is a person. Explain why you selected this particular individual to be studied and describe what experiences they have had that provide an opportunity to advance new understandings about the research problem. Mention any background about this person which might help the reader understand the significance of their experiences that make them worthy of study. This includes describing the relationships this person has had with other people, institutions, and/or events that support using them as the subject for a case study research paper. It is particularly important to differentiate the person as the subject of analysis from others and to succinctly explain how the person relates to examining the research problem [e.g., why is one politician in a particular local election used to show an increase in voter turnout from any other candidate running in the election]. Note that these issues apply to a specific group of people used as a case study unit of analysis [e.g., a classroom of students].

If your subject of analysis is a place. In general, a case study that investigates a place suggests a subject of analysis that is unique or special in some way and that this uniqueness can be used to build new understanding or knowledge about the research problem. A case study of a place must not only describe its various attributes relevant to the research problem [e.g., physical, social, historical, cultural, economic, political], but you must state the method by which you determined that this place will illuminate new understandings about the research problem. It is also important to articulate why a particular place as the case for study is being used if similar places also exist [i.e., if you are studying patterns of homeless encampments of veterans in open spaces, explain why you are studying Echo Park in Los Angeles rather than Griffith Park?]. If applicable, describe what type of human activity involving this place makes it a good choice to study [e.g., prior research suggests Echo Park has more homeless veterans].

If your subject of analysis is a phenomenon. A phenomenon refers to a fact, occurrence, or circumstance that can be studied or observed but with the cause or explanation to be in question. In this sense, a phenomenon that forms your subject of analysis can encompass anything that can be observed or presumed to exist but is not fully understood. In the social and behavioral sciences, the case usually focuses on human interaction within a complex physical, social, economic, cultural, or political system. For example, the phenomenon could be the observation that many vehicles used by ISIS fighters are small trucks with English language advertisements on them. The research problem could be that ISIS fighters are difficult to combat because they are highly mobile. The research questions could be how and by what means are these vehicles used by ISIS being supplied to the militants and how might supply lines to these vehicles be cut off? How might knowing the suppliers of these trucks reveal larger networks of collaborators and financial support? A case study of a phenomenon most often encompasses an in-depth analysis of a cause and effect that is grounded in an interactive relationship between people and their environment in some way.

NOTE: The choice of the case or set of cases to study cannot appear random. Evidence that supports the method by which you identified and chose your subject of analysis should clearly support investigation of the research problem and linked to key findings from your literature review. Be sure to cite any studies that helped you determine that the case you chose was appropriate for examining the problem.

IV. Discussion

The main elements of your discussion section are generally the same as any research paper, but centered around interpreting and drawing conclusions about the key findings from your analysis of the case study. Note that a general social sciences research paper may contain a separate section to report findings. However, in a paper designed around a case study, it is common to combine a description of the results with the discussion about their implications. The objectives of your discussion section should include the following:

Reiterate the Research Problem/State the Major Findings Briefly reiterate the research problem you are investigating and explain why the subject of analysis around which you designed the case study were used. You should then describe the findings revealed from your study of the case using direct, declarative, and succinct proclamation of the study results. Highlight any findings that were unexpected or especially profound.

Explain the Meaning of the Findings and Why They are Important Systematically explain the meaning of your case study findings and why you believe they are important. Begin this part of the section by repeating what you consider to be your most important or surprising finding first, then systematically review each finding. Be sure to thoroughly extrapolate what your analysis of the case can tell the reader about situations or conditions beyond the actual case that was studied while, at the same time, being careful not to misconstrue or conflate a finding that undermines the external validity of your conclusions.

Relate the Findings to Similar Studies No study in the social sciences is so novel or possesses such a restricted focus that it has absolutely no relation to previously published research. The discussion section should relate your case study results to those found in other studies, particularly if questions raised from prior studies served as the motivation for choosing your subject of analysis. This is important because comparing and contrasting the findings of other studies helps support the overall importance of your results and it highlights how and in what ways your case study design and the subject of analysis differs from prior research about the topic.

Consider Alternative Explanations of the Findings Remember that the purpose of social science research is to discover and not to prove. When writing the discussion section, you should carefully consider all possible explanations revealed by the case study results, rather than just those that fit your hypothesis or prior assumptions and biases. Be alert to what the in-depth analysis of the case may reveal about the research problem, including offering a contrarian perspective to what scholars have stated in prior research if that is how the findings can be interpreted from your case.

Acknowledge the Study's Limitations You can state the study's limitations in the conclusion section of your paper but describing the limitations of your subject of analysis in the discussion section provides an opportunity to identify the limitations and explain why they are not significant. This part of the discussion section should also note any unanswered questions or issues your case study could not address. More detailed information about how to document any limitations to your research can be found here .

Suggest Areas for Further Research Although your case study may offer important insights about the research problem, there are likely additional questions related to the problem that remain unanswered or findings that unexpectedly revealed themselves as a result of your in-depth analysis of the case. Be sure that the recommendations for further research are linked to the research problem and that you explain why your recommendations are valid in other contexts and based on the original assumptions of your study.

V. Conclusion

As with any research paper, you should summarize your conclusion in clear, simple language; emphasize how the findings from your case study differs from or supports prior research and why. Do not simply reiterate the discussion section. Provide a synthesis of key findings presented in the paper to show how these converge to address the research problem. If you haven't already done so in the discussion section, be sure to document the limitations of your case study and any need for further research.

The function of your paper's conclusion is to: 1) reiterate the main argument supported by the findings from your case study; 2) state clearly the context, background, and necessity of pursuing the research problem using a case study design in relation to an issue, controversy, or a gap found from reviewing the literature; and, 3) provide a place to persuasively and succinctly restate the significance of your research problem, given that the reader has now been presented with in-depth information about the topic.

Consider the following points to help ensure your conclusion is appropriate:

- If the argument or purpose of your paper is complex, you may need to summarize these points for your reader.

- If prior to your conclusion, you have not yet explained the significance of your findings or if you are proceeding inductively, use the conclusion of your paper to describe your main points and explain their significance.

- Move from a detailed to a general level of consideration of the case study's findings that returns the topic to the context provided by the introduction or within a new context that emerges from your case study findings.

Note that, depending on the discipline you are writing in or the preferences of your professor, the concluding paragraph may contain your final reflections on the evidence presented as it applies to practice or on the essay's central research problem. However, the nature of being introspective about the subject of analysis you have investigated will depend on whether you are explicitly asked to express your observations in this way.

Problems to Avoid

Overgeneralization One of the goals of a case study is to lay a foundation for understanding broader trends and issues applied to similar circumstances. However, be careful when drawing conclusions from your case study. They must be evidence-based and grounded in the results of the study; otherwise, it is merely speculation. Looking at a prior example, it would be incorrect to state that a factor in improving girls access to education in Azerbaijan and the policy implications this may have for improving access in other Muslim nations is due to girls access to social media if there is no documentary evidence from your case study to indicate this. There may be anecdotal evidence that retention rates were better for girls who were engaged with social media, but this observation would only point to the need for further research and would not be a definitive finding if this was not a part of your original research agenda.

Failure to Document Limitations No case is going to reveal all that needs to be understood about a research problem. Therefore, just as you have to clearly state the limitations of a general research study , you must describe the specific limitations inherent in the subject of analysis. For example, the case of studying how women conceptualize the need for water conservation in a village in Uganda could have limited application in other cultural contexts or in areas where fresh water from rivers or lakes is plentiful and, therefore, conservation is understood more in terms of managing access rather than preserving access to a scarce resource.

Failure to Extrapolate All Possible Implications Just as you don't want to over-generalize from your case study findings, you also have to be thorough in the consideration of all possible outcomes or recommendations derived from your findings. If you do not, your reader may question the validity of your analysis, particularly if you failed to document an obvious outcome from your case study research. For example, in the case of studying the accident at the railroad crossing to evaluate where and what types of warning signals should be located, you failed to take into consideration speed limit signage as well as warning signals. When designing your case study, be sure you have thoroughly addressed all aspects of the problem and do not leave gaps in your analysis that leave the reader questioning the results.

Case Studies. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Gerring, John. Case Study Research: Principles and Practices . New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007; Merriam, Sharan B. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education . Rev. ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1998; Miller, Lisa L. “The Use of Case Studies in Law and Social Science Research.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 14 (2018): TBD; Mills, Albert J., Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Putney, LeAnn Grogan. "Case Study." In Encyclopedia of Research Design , Neil J. Salkind, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010), pp. 116-120; Simons, Helen. Case Study Research in Practice . London: SAGE Publications, 2009; Kratochwill, Thomas R. and Joel R. Levin, editors. Single-Case Research Design and Analysis: New Development for Psychology and Education . Hilldsale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1992; Swanborn, Peter G. Case Study Research: What, Why and How? London : SAGE, 2010; Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods . 6th edition. Los Angeles, CA, SAGE Publications, 2014; Walo, Maree, Adrian Bull, and Helen Breen. “Achieving Economic Benefits at Local Events: A Case Study of a Local Sports Event.” Festival Management and Event Tourism 4 (1996): 95-106.

Writing Tip

At Least Five Misconceptions about Case Study Research

Social science case studies are often perceived as limited in their ability to create new knowledge because they are not randomly selected and findings cannot be generalized to larger populations. Flyvbjerg examines five misunderstandings about case study research and systematically "corrects" each one. To quote, these are:

Misunderstanding 1 : General, theoretical [context-independent] knowledge is more valuable than concrete, practical [context-dependent] knowledge. Misunderstanding 2 : One cannot generalize on the basis of an individual case; therefore, the case study cannot contribute to scientific development. Misunderstanding 3 : The case study is most useful for generating hypotheses; that is, in the first stage of a total research process, whereas other methods are more suitable for hypotheses testing and theory building. Misunderstanding 4 : The case study contains a bias toward verification, that is, a tendency to confirm the researcher’s preconceived notions. Misunderstanding 5 : It is often difficult to summarize and develop general propositions and theories on the basis of specific case studies [p. 221].

While writing your paper, think introspectively about how you addressed these misconceptions because to do so can help you strengthen the validity and reliability of your research by clarifying issues of case selection, the testing and challenging of existing assumptions, the interpretation of key findings, and the summation of case outcomes. Think of a case study research paper as a complete, in-depth narrative about the specific properties and key characteristics of your subject of analysis applied to the research problem.

Flyvbjerg, Bent. “Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 12 (April 2006): 219-245.

- << Previous: Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Next: Writing a Field Report >>

- Last Updated: May 7, 2024 9:45 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

Implementing Alternative Technical Concepts in All Types of Highway Project Delivery Methods (2020)

Chapter: appendix c: case study protocol and questionnaire.

Below is the uncorrected machine-read text of this chapter, intended to provide our own search engines and external engines with highly rich, chapter-representative searchable text of each book. Because it is UNCORRECTED material, please consider the following text as a useful but insufficient proxy for the authoritative book pages.

C-1 Appendix C: Case Study Protocol and Questionnaire The key step in Task 2.1 was developing a case study protocol for the case study interviews and data collection plan. The protocol included a research synopsis of objectives, projects, field procedures that detail the logistical aspects of the investigation, interview questions, and documentation to collect and a format for documenting and analyzing the individual case studies (Eisenhardt 1989; Yin 1994). In addition, a plan will be developed for cross case comparisons to determine similarities and differences between cases (Eisenhardt 1989; Miles and Huberman 1994). The case study protocol permits the research team to conduct case studies separately in different parts of the country, while maintaining the reliability of the case study results. Internal validity is addressed by attending to multiple sources of evidence and the use of multiple case studies improves the external validity of the project delivery and project control tools that may be identified as promoting ATC project success. Case Study Protocol Background Information The following information is summarized from the Interim Report: Alternative contracting methods (ACM), such as Design-build (DB), Construction Management/General Contractor (CMGC), and Public-Private Partnerships (P3), have been proven to accelerate the construction, reconstruction, and rehabilitation of aging, structurally deficient infrastructure because they generally permit early contractor involvement during the procurement and in some cases, ACMs also allow construction to begin before the design is 100 percent complete. ACMs also allow the DOT to shift some of the responsibility for completing the necessary preconstruction tasks to support the design after the award of the DB, CMGC, or P3 contract. This creates a different risk profile than when the project owner has full responsibility for design in a traditional design-bid-build (DBB) project. ATCs augment the ability to increase integration in both DBB and ACM projects. Therefore, the primary thrust of the case study data collection effort is to document the effectives practices found in each DOT for implementing ATCs in each project delivery method. The following are the objectives of the case study research data collection plan. ⢠To identify and compare the advantages and disadvantages of each ACM with respect to determining applicability and appropriateness to support the DOT ATC selection decision process. ⢠The following are the specific objectives taken from the Phase 2 workplan that will be addressed by the data collected in the case study task: 1. Develop a decision-making tool that will guide project sponsors in determining when to incorporate ATCs into the entire range of ACMs and DBB to determine the potential benefits based on project characteristics, agency goals, and context in which the project will be delivered and operated over the projectâs life cycle. 2. Obtain input on the ATC Toolkit (including the analytical tools and decision-making tool) from stakeholders.

C-2 3. Pilot test the ATC Toolkit on projects proposed in two DOTs with varying degrees of ATC experience to check the reasonableness of results from the Toolkit and thereafter incorporate any lessons learned into the final Toolkit. Relevant Definitions Across the highway construction and engineering industry, terms relating to quality often have multiple meanings that in some cases overlap with one another and in others supersede each other. To prevent confusion among several vital terms important to this study, the following definitions have been provided. These definitions are in accordance with the most recent issuance of the TRB Circular Glossary of Highway Quality Assurance Terms E-C137 and the NCHRP Synthesis 376. ï§ Design-bid-build (DBB): A project delivery system in which the design is completed either by in-house professional engineering staff or a design consultant before the construction contract is advertised. [The design-bid-build method is sometimes referred to as the traditional method.] ï§ Design-build (DB): A project delivery system in which both the design and the construction of the project are simultaneously awarded to a single entity. [The main advantage of the designâ build method is that it can decrease project delivery time.] ï§ Construction manager/general contractor (CMGC) Also called Construction manager-at- risk (CMR): A project delivery system that entails a commitment by the construction manager to deliver the project within a guaranteed maximum price (GMP), in most cases. The construction manager acts as consultant to the owner in the development and design phases and as the equivalent of a general contractor during the construction phase. ï§ Public-private partnership (P3): A government service or private business venture that is funded and operated through a partnership of government and one or more private-sector companies. Statement of Purpose The primary research objectives for this project are as follows: ⢠Document and categorize current practices and applications for selecting a given ATC for the general population of all project delivery methods. ⢠Explore how highway construction projects of all project delivery methods are effectively applying ATCs. ⢠Identify benefits and limitations of the approaches. ⢠Explore how to implement and apply project performance metrics and evaluation methods for all methods of project delivery specific to ATCs. ⢠Produce a decision-making tool to that will guide project sponsors in determining when to use ATCs on the entire range of project delivery methods. ⢠Produce an ATC Toolkit, including decision-making and ATC performance evaluation tools. Field Procedures Project Researchers ï§ Doug Gransberg, G&A

C-3 ï§ Mike Loulakis CPS ï§ Keith Molenaar, CU ï§ Jorge Rueda, AU ï§ Ghada Gad, CPP ï§ Debra Brisk DRB ï§ Steve DeWitt, TIS Case study delegation ï§ Gransberg â Georgia, Missouri, and Ohio, DOT ï§ Rueda â Alabama and Minnesota DOT ï§ Molenaar â Colorado and Washington DOT ï§ Gad â California and Utah DOT ï§ Brisk â Minnesota DOT ï§ DeWitt â North Carolina DOT Case study project selection criteria In the interim report, it was stated that a concerted effort will be made to select case study projects from transportation agencies that have mature experience with at least two different project delivery methods. The following selection rubric was used to select the DOTs found in the previous section. ⢠Mature ACM program â Have completed more than 10 DB projects with ATCs. ⢠ACM program authorized to use more than one ACM with ATCs used on at least one. ⢠ATC program has been institutionalized by the development of standard guidance in the form of manuals, guidebooks, policy documents, etc. containing ATC selection and/or evaluation methodologies. ⢠Project performance data is available for both ACM and DBB projects on a program basis. Case study informant selection Once a case study DOT has been selected, several members of the team directly associated with the agencyâs ACM selection decision process and if possible, the agencyâs project performance measurement process will be contacted and asked for an appointment for an interview. Potential interviewees include the following: ï§ Agency-level ACM office directors or equivalent for centralized DOTs. ï§ District engineers and staff responsible for selecting ACMs for decentralized DOTs. ï§ Project-level project managers, construction managers, design managers, etc.

C-4 Case Study Basic Data and Research Delegation Tables # Case Study Name Location Organization Contact (Information) 1 2 3 4 5 6 # Case Study Name Contacted? Lead Investigator Interview Type Interview Date Follow-up Date 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 # Case Study Name Materials/Documents Received 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Case study field procedures A case study structured interview is not merely an oral survey. This research instrument is used to not only answer the what and where questions, but more importantly the why and how questions that cannot be reliably collected through standard survey research. The primary input to the case studies will be gathered through structured interviews with agency personnel, contractors, and consultants that have been part of teams involved with complex projects. The structured interview questionnaires will be developed on lines prescribed by the US Government Accounting Office (GAO 1991). The GAO method states that structured interviews can be used where âinformation must be obtained from program participants or members of a comparison group⦠or when essentially the same information must be obtained from numerous people for a multiple case-study evaluationâ (GAO 1991). Both these conditions apply to this project therefore, the tool is appropriate for the research. The process involves developing a questionnaire that was made available to each interviewee prior to the interview and then collecting responses in the same order using the same questions for each interviewee. The information can be gathered by both face-to-face and telephonic interviews. Time is given per the GAO method to ensure that the interviewee understands each question and that the data collector understands the answer. Additionally, interviewees are also allowed to digress as desired, which allows the researchers to collect potentially valuable information that was not

C-5 originally contemplated. The output is used to present the agenciesâ perspective on various points analyzed in the subsequent tasks. The interview process generally follows the below set of steps: 1. Once an appointment for the interview has been made, send the questionnaire to the point of contact with instructions to review it prior to the interview. Also request that the interviewee obtain access to any relevant documents and have them available at the interview. 2. Commence the interview with a short explanation of the project, the desired information, and a statement that nothing will be published before the interviewee has had an opportunity to review the draft material and correct it as required. 3. Next, explain the questioning process. You will ask a question and then ask the respondents if they understand it. If not, further explanation will be provided. After the answer is given and recorded, you will read it back to the interviewee and give them an opportunity to refine it if required. 4. The process then proceeds question by questions until it is complete. 5. It is particularly important to allow the interviewee to digress if the tangent appears to be of interest to the research. The questionnaire is not in and of itself complete and generally applicable to all agencies. Therefore, the local variations and subtleties will be found in the digressions from the questions. 6. Complete the interview by recapping the major findings that you have drawn from the interview and ensure that you have correctly interpreted them. 7. Be sensitive to local semantics/jargon and ask for clarifications even if you think you understand. Donât assume that your past experiences are in any way reflective of how things work in the interviewed agency. Data Analysis The data collected will be synthesized and evaluated to produce the following output: ï§ Advantages and disadvantages to each system from the agencyâs point of view. ï§ Identification of trends and common finding between the literature review, survey and case studies. ï§ Triangulate the common findings from these three sources of data to arrive at valid conclusions. ï§ Case studies will be summarized individually in the lens of the ATC selection decision model. ï§ Using literature review and previous phone survey information, compare key attributes of the baseline approach to key attributes in the ACM models. ï§ Individual findings will be analyzed across the cases using pattern matching techniques. ï§ Comparison to baseline DBB project delivery approaches. Draft Individual Case Study Report Outline The following is an outline of the case study summary that each data collector will produce. 1. Agency: 2. Locations: 3. Average annual construction program: $

C-6 4. Average annual ACM program: $ 5. See Table ACM Approx Total # Approx Annual # Average Project Value System for Selection? Primary Reason for Selecting DBB CMGC DB PDB P3 6. See Table ACM Procurement Method Used (check all) Primary Reason for Selecting Procurement Method QBS Best Value Low Bid Other DBB CMGC DB PDB P3 7. Detailed description of agency ACM selection process. Include copies of any documents that may be available for this process. 8. Detailed description of agency ACM performance evaluation process. Include copies of any documents that may be available for this process. 9. Short discussion on interviewees perceptions of the following: a. Impact of each ATC on internal staffing requirements. b. Impact of each ATC on cost/budget certainty. c. Impact of each ATC on schedule certainty. d. Impact of each ATC on final constructed quality. e. Major disadvantage of ATCs for each ACM. 10. Summary â Brief synopsis of the case study that includes statements on the following topics: a. Assessment of the agencyâs ATC experience, organizational maturity, and potential to be used as a model for the tool set. b. Agency ATC selection process, if any. c. Agency ATC project evaluation process, if any. d. Agency ATC tools, if any. e. Key findings that will lend authority to the tool set under development. f. Other key findings. 11. Observations of the Researchers â This section is reserved for comments that are important to understanding the case study agency but are not covered in the above report format. Items like specific innovations, anecdotal negative experiences, opinions formed by the interviewers, etc. will go in this section.

C-7 Post Collection Analysis The case study output will be analyzed to determine candidate effective practices and best practices using a rigorous method based on importance index theory, as published by Gransberg et al. (2017) in Transportation Research Record No. 2630 entitled: âA Framework for Objectively Determining Alternative Contracting Method Best Practices.â First, the researchers will augment the set of ATC effective practices that were identified in NCHRP Synthesis 455: Alternative Technical Concepts for Contract Delivery Methods and augment it with ATC related practices found during the Task 1.1 Benchmarking effort to produce a list of candidate practices. Secondly, the candidate ATC practices will be sorted into one of three categories based on a breakdown found in a report sponsored by the Connecticut Academy of Science and Technology on project deliverability (Lownes et al. 2012). The documents were classified into the following categories: 1. Organizational structure 2. Project delivery method selection process 3. Contracting techniques Each given practice will then be evaluated to determine if it qualified as a candidate for classification as an effective practice using the definition of having been âidentified through high quality quantitative study.â The last stage will impose an additional condition that the practice had to have been observed as used by more than one state DOT by using the survey results from NCHRP and SPR research reports or similar documents, compiling a comprehensive list of all synthesis survey respondents that reported using the given practice. Once the list of candidates is identified in each category, they will be ranked using a rubric termed the âImportance Indexâ (II) (Assaf and Al-Hejji, 2006). The II is a combination of the frequency at which a specific practice was observed in the content analysis of the literature and its influence measured by the number of state DOTs that have adopted the practice. As such, the II holds that practices that are used frequently and are of high influence are more important that low frequency, low influence practices. This permits an objective ranking of candidate effective practices, which can then be used to infer the relative importance of adopting a specific ATC effective practice. The II is derived by first computing a Frequency Index (FI) and an Adoption Index (AI) based on Equations 1 and 2 to furnish input in the II calculation shown in Equation 3: Frequency Index (FI) (%) = â(n/ N)*100/Tn [Eqn 1] Where: n = Number of observations of a practice in a specific category N = Total observations of all practices in a specific category Tn = Total observations of all practices in all categories Adoption Index (AI) (%) = â(d/ D)*100/Td [Eqn 2] Where: d = Number of DOTs using a practice in a specific category D = Total DOTs using all practices in a specific category Td = Total DOTs using all practices in all categories

C-8 Importance Index (II) (%) = (FI * AI) [Eqn 3] The result is a list of ranked candidate practices within each category as well as a second list of all practices ranked as a total population. This is done because each of the categories describes a separate facet of ATC implementation and it is important to understand the relative importance within each category. The overall ranking informs the analyst regarding those practices which when combined enhance the effectiveness of the ATC program. To test the criterion proposed by Accardo (2009) regarding âhigh quality quantitative study,â a Research Index (RI) and a Verification Index (VI) are computed using Equations 4 and 5 based on the Assaf and Al-Hejjiâs (2006) II theory. Research Index (RI) (%) = â(c/ C)*100/Tc [Eqn 4] Where: c = Number of literature citations reporting a practice in a specific category C = Total literature citations using all practices in a specific category Tc = Total literature citations using all practices in all categories Verification Index (VI) (%) = (RI * I) [Eqn 5] Lastly, a criterion will be developed based on the Task 1.1 benchmarking results to differentiate a best practice from an effective practice. The TRR paper used the criterion proposed by Michaelson and Stacks (2011) that consists of two objective criteria, which permit the analyst to identify a best practice from a practice that a given author believes to be sound. Their definition is: âA method or technique that has consistently shown results superior to those achieved with other means, and that is used as a benchmark.â The terms âsuperior to other meansâ and âused as a benchmarkâ furnish a means to distinguish a best practice from all other practices when evaluating the content of a particular document. As one would expect to be both consistently superior and a benchmark is a pretty lofty standard and will not often be attained. The team will pilot the case study protocol to ensure that it will provide the desired information. In the pilot test, case study participants will also be asked to comment on the protocol, covering topics such as ease of understanding, ease of response, amount of required pre-interview preparation required, etc. The protocol will then be modified as required. Once the team has scheduled case studies with the DOT, consultant, and contractor organizations, the case study data collection will commence. The primary objective of these case studies is to build solid theory for each delivery method. This theory will be developed by conducting several forms of data collection, including objective project risk model characteristic measurement, subjective interviews, and project performance metrics. The goal for case study selection is to generate a cross section of cases that permits the analysis of the advantages and disadvantages of the various ATC models across the various project characteristics. To ensure that this goal is met, the following criteria will be placed on the case study selection.

C-9 ⢠Completed projects delivered using DBB, CMGC, DB, P3 and other ACMs. ⢠Agency solicitation documents are available for content analysis. ⢠Financial and schedule progress data available. ⢠Design consultant and construction contractor available for interviews ⢠Agency information â construction volume, outsourcing of design, seasonal issues, and so forth. ⢠Alternative project delivery experience data â number, type, cost/schedule performance, project-specific legal issues, claims, protests, and so forth. The case study data collection plan will include the procedures for assembling the necessary input data to calculate metrics that can be used to identify potential effective practices for use in the Task 2.2 draft guidebook. During each case study interview, the DOT will be asked to furnish quantitative data on the case study project. The focus will be on projects where ATCs resulted in documented benefits as well as projects where the ATC process was not considered successful. It is hoped that the outcomes can also be mapped to create the tools for the Task 2.6 implementation toolkit in addition to furnishing definitive guidance that can be provided in the final guidebook. Upon completion of the case studies, the team will reduce and analyze the case study data to identify trends and disconnects, gaps in the body of knowledge, needs for contract clause guidance, examples of successful practices, lessons learned and candidate best practices Figure C.1 is a flow chart showing the logic used in the research methodology for gleaning both best and effective practices from the case study data.

C-10 Figure C. 1. Best Practice Determination Flow Chart NCHRP Project Survey Output DOT ACM Policy Documents Academic ACM Literature Identify ACM Effective Practice Candidates Content Analysis Content Analysis Content Analysis ACM Practices Reported in Surveys ACM Practices Formally Adopted ACM Practices Evaluated by Research Candidate Set of Effective Practices Compute Frequency Index Compute Adoption Index Compute Research Index Compute Importance Index Compute Verification Index Compute Average Composite Rank Ranked Best Practices Candidates Rank by Importance Index Ranked Effective Practices by Category Ranked Effective Practices by Population Rank by Verification Index Ranked Effective Practices by Category Ranked Effective Practices by Population Meets âBestâ Criteria? Effective Practice List Best Practice ListYES NO

C-11 Case Study Interview Questionnaire Case study DOTs and rationale State Level PDM Rationale Remarks California Program DB/CMGC/ P3 Recent DB ATC program Georgia Program DB/P3 P3 ATC program Minnesota Program DB/ CMGC Pre-approved Element (PAE) program (risk management tool) Missouri Program DBB/DB DBB ATC program + Conceptual ATC (CATC) Washington Program DB Long standing DB ATC program Single Project Case Studies Alabama Project DBB DBB ATC for the first time Colorado Project DB Alternative Configuration Concept (ACC) North Carolina Project P3 P3 ATC Ohio Project DB Geotechnical DB ATC (risk management tool) Rhode Island Project DB Limited scope utility ATC DB Unable to arrange interview with project team members Utah Project CMGC Proposed Technical Concept (PTC) CMGC NOTE: Program level case studies will also conduct a project-level case study.

C-12 Case Study Project Structured Interview INTRODUCTION/BACKGROUND: The purpose of this questionnaire is to identify state highway agency effective policies and procedures for delivering construction projects using alternative technical concepts (ATCs). The objective of this research is to produce a practical guidebook in AASHTO standard format that presents effective practices for establishing and implementing ATCs in project delivery methods. Its specific focus is on the specific policies and contractual content used during procurements that include ATCs as well as the benefits and/or costs associated with the use of ATCs. DEFINITIONS: The following definitions are used in conjunction with this questionnaire: ⢠Alternative technical concepts (ATC): A procedure where the designers and/or contractors are asked to furnish alternative design solutions for features of work designated by the agency in its procurement documents. The proposed changes must be equal to or better than the baseline design contained in the solicitation documents. ⢠ATC project: A project delivered using any project delivery method that includes ATCs as part of the pre-award process. ⢠Design-bid-build (DBB): A project delivery method where the design is completed either by in-house professional engineering staff or a design consultant before the construction contract is advertised. Also called the âtraditional method.â ⢠Construction Manager/General Contractor (CMGC): A project delivery method where the contractor is selected during design and furnishes preconstruction services. Also called CM-at-Risk. ⢠Design-build (DB): A project delivery method where both the design and the construction of the project are simultaneously awarded to a single entity. ⢠Public-Private Partnership (P3): A project delivery methods where private funding is involved. There are many variations. ⢠Best Value: An award method that utilizes cost and other factors to select the winning bidders. Examples are cost-plus-time bidding, qualifications, design approach, etc. ⢠One-on-One meetings: Confidential meetings between the agency and individual entities that are competing for the same project whose purpose is to propose, review, and approve/disapprove ATCs before the entityâs bid or proposal is submitted. ⢠Open records act: A statutory requirement to disclose all information pertaining to public project upon request by a member of the public. Also termed âSunshine Law.â

C-13 I. Agency and Interviewee General Information: 1. DOT: 2. On average, how many projects using the ATC process does your agency deliver each year? In the past year, approximately how many projects allowed for the submission of ATCs? On average, how many contractors submit ATCs for each project? On average, how many ATCs were submitted by each proposer? What percentage of ATCs are approved? Rough estimate is acceptable. 3. What project delivery methods does your organization use? For which of them does your organization use ATC provisions? Check all that apply. Project Delivery Method Typical Project ATC Project DBB CM-at-Risk or CMGC DB Other, please specify Procurement Method Low Bid Best Qualified Best Value Other, please specify II. Agency ATC Practices â General Information 4. Does your agency have a manual or solicitation document that specifically describes the procedures to be used with projects using the ATC process? Yes No 5. How does your agency define an ATC? 6. Which of the following reasons motivates the use of ATC provisions in contracts awarded by your agency? Check all that apply. Which of the below is the single most significant reason for the use of ATC provisions? (Interviewer circle the check box) Reduce project duration Increase quality Encourage innovation Project size Increase agency control over budget Reduce preconstruction costs Reduce risk related to contractors poor performance Optimize use of agency resources Third party issues (permits, utilities, etc.) Low complexity of scope of work High complexity of scope of work Reduce agency staffing requirements Transfer design liability to contractor The confidentiality of pre-proposal communications with contractors The greater integration between the agency and the contractors The ability to identify issues in the solicitation documents before awarding the contract Other

C-14 7. Which of the below policies or procedures apply to a project delivery method that uses ATCs? (Check all that apply) DBB CMGC DB Doesnât apply The scope of what can be submitted as an ATC is limited. The features of work where changes from ATCs may be proposed is specified. Confidential one-on-one meetings are held. The contractor may choose to include or not include any of its approved ATCs in its proposal. ATCs submitted for approval must include an estimate/statement of cost impact. ATCs submitted for approval must include an estimate/statement of schedule impact. ATCs submitted for approval must include a statement of quality impact. Cost estimates from ATCs are reviewed by an independent cost estimator. Stipends are paid and permit the agency to use ATCs proposed by entities other than the winner. Stipends are paid and do NOT permit the agency to use ATCs proposed by entities other than the winner. ATCs are reviewed and approved by the project evaluation, selection, or award panel. ATCs are reviewed and approved by personnel other than the project evaluation, selection, and/or award panel. If required, the agency can refer an ATC to a third party for technical review. The number of ATCs submitted by a single entity is limited. If the ATC is a design change, the contractor must prove that it has been reviewed by an engineer licensed in the agencyâs state. Design concepts/standards/specifications from other states/agencies are permissible. ATCs can be used to propose changes to the general provisions to the contract. ATCs can be used to propose changes to the special provisions to the contract. Use of formal risk allocation techniques to draft contract provisions regarding ATCs 8. How does your local open records act impact the use of ATCs by your agency? No impact, we are able to adequately protect the confidentiality of the content of all ATCs submitted regardless if they come from a winning or losing proposer. Minimal impact, we are able to adequately protect the confidentiality of the content of all ATCs submitted throughout the procurement process and only the contents of ATCs that are included in the winning proposal are exposed to the public record after award. Minimal impact, we are able to adequately protect the confidentiality of the content of all ATCs submitted throughout the procurement process and only the contents of ATCs that are included in the winning proposal plus those from losing proposers who accept a stipend are exposed to the public record after award. Major impact, all ATCs submitted as parts of the procurement are exposed to the public record after award. Major impact, all ATCs submitted as parts of the procurement are at risk of being exposed to the public record before award. Our open records act makes it functionally impossible to reasonably consider ATCs in a manner that is fair and equitable to our industry partners. 9. Have you ever received a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request from a contractor in order to obtain information about approved ATCs submitted by other bidders? Yes No Donât know If yes; how did you respond to the FOIA request(s)?

C-15 10. Rate the following factors based on their importance to the success of the ATC during the procurement process. Factor Essential Important Not Important No Opinion Confidential one-on-one meetings Confidentiality of pre-proposal communications between agency and contractors on matters other than ATCs Ability to safeguard ATCs containing proprietary content Ability to guarantee ATC confidentially Offering a stipend to use ideas from losing entities. Ability to grant design criteria variances Excluding ATCs that would exceed permitting constraints Allowing ATCs that would exceed permitting constraints Ability to measure the benefits upon project completion Independent technical review of ATC designs Independent review of ATC cost estimates Agency buy-in to the ATC process Industry buy-in to the ATC process Incentives/disincentive schemes 11. How do you assign design liability to ATCs? Assignment DBB CMGC DB Agency retains liability Liability is shifted to contractor Liability is shifted to the contractorâs design consultant Other; please specify. III. Case Study Project - General Information: 12. Case Study Project Title: 13. Project Delivery Method: 14. Short Scope Description: 15. Expected contract duration: 16. Actual project duration: 17. Award amount: 18. Actual cost at project completion: 19. How was this project funded? State funds Federal funds State and Federal funds 20. General Composition of Project Scope: Road Construction Bridge Construction/Replacement

C-16 Road Repair Bridge Repair Road Routine Maintenance Bridge Routine Maintenance Hazardous waste treatment, mitigation, removal Landscaping Erosion Control/Stormwater Mitigation Environmental Mitigation Bike lanes, sidewalks, transportation enhancement ADA-Related Improvements Traffic Signalization Drainage Maintenance Rest Area Improvements Pavement Markings Roadway Safety Improvement/Maintenance Other: {explain} A. Does your agency limit the use of ATC provisions to this type project? Yes No 21. Number of proposers and ATCs How many contractors submitted proposals on this project? How Many contractors submitted proposals with approved ATCs? How many proposals were submitted for review? How many proposals were approved? 22. Do you believe the number of proposals submitted for this project was impacted by the use ATC provisions? Yes No If yes, explain: IV. Case Study â Procurement Process 23. How did you advertise and award the case study contract? Advertise/Award Method Invitation for Bids (IFB), full open competition, low bid IFB, competition restricted to prequalified entities, low bid 1-step full open competition RFQ, QBS, no price competition 1-step full open competition RFP, includes qualifications, technical, and price 2-step full open competition, RFQ/RFP 1-step competition restricted to prequalified entities RFQ, QBS, no price competition 1-step competition restricted to prequalified entities RFP, includes qualifications, technical, and price 2-step competition restricted to prequalified entities, RFQ/RFP Sole source Other, please specify 24. Refer to question 23. Is this advertise/award approach the usual approach used when allowing ATCs with other project delivery methods? Yes No Donât know If no, explain why it is different: 25. Refer to question 23. Is this advertise/award approach the usual approach used in non- ATC contracts executed under the same project delivery method? Yes No Donât know If no, explain why it is different: 26. Did you develop a shortlist for this project

C-17 Yes No Donât know If yes; how many contractors were in the shortlist: 27. What is the disposition of an approved ATC? Check all that apply. Approved ATCs remain confidential through award of final contract. Approved ATCs of winning contractor are revealed upon award. Approved ATCs from losing contractors are revealed upon award. Approved ATCs from losing contractors remain confidential after award. Approved ATC triggers an addendum to the solicitation to all competitors Other please describe: 28. Have you had a protest of an awarded contract related to the ATC process? Yes No If yes, what was the basis of the protest? Please describe: 29. Refer to question 28. What was the result of the protest? Protest was upheld Protest was overturned Protest was dropped Comments? 30. Please check all of the applicable features that describe the process you use for you confidential one-on-one meetings that involve ATCs. One-on-one Meeting Features One or more one-on-one meetings are required for all competing contractors One or more one-on-one meetings are optional for all competing contractorsâ agencyâs decision One or more one-on-one meetings are optional for all competing contractorsâ contractorâs decision Agency members at the meeting are from the evaluation panel Agency members at the meeting are not necessarily from the evaluation panel â relevant agencyâs staff One-on-one meetings are held before submitting the Initial ATC One-on-one meetings are held after submitting the Initial ATC One-on-one meetings are held at the moment of submitting the Initial ATC V. Case Study â Payment Provisions 31. What type of compensation method was used in this project? Was the compensation method the same for the ATC and non-ATC work? ATC Non-ATC Other: Unit Price Lump Sum Cost-Reimbursable Other: 32. Refer to question 31. Is this the usual compensation approach used when allowing ATCs with other project delivery methods? Yes No Donât know If no, explain why it is different: