Elements of Literature

WHAT DO WE MEAN BY THE PHRASE ‘ELEMENTS OF LITERATURE?

The phrase ‘elements of literature’ refers to the constituent parts of a work of literature in whatever form it takes: poetry, prose, or drama.

Why are they important?

Students must understand these common elements if they are to competently read or write a piece of literature.

Understanding the various elements is particularly useful when studying longer works. It enables students to examine specific aspects of the work in isolation before piecing these separate aspects back together to display an understanding of the work as a whole.

Having a firm grasp on how the different elements work can also be very useful when comparing and contrasting two or more texts.

Not only does understanding the various elements of literature help us to answer literature analysis questions in exam situations, but it also helps us develop a deeper appreciation of literature in general.

what are the elements of literature ?

This article will examine the following elements: plot , setting, character, point-of-view, theme, and tone. Each of these broad elements has many possible subcategories, and there is some crossover between some elements – this isn’t Math , after all!

Hundreds of terms are associated with literature as a whole, and I recommend viewing this glossary for a complete breakdown of these.

WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN AN ELEMENT OF LITERATURE AND A LITERARY DEVICE?

Elements of literature are present in every literary text. They are the essential ingredients required to create any piece of literature, including poems, plays, novels, short stories, feature articles, nonfiction books, etc.

Literary devices , on the other hand, are tools and techniques that are used to create specific effects within a work. Think metaphor, simile, hyperbole, foreshadowing, etc. We examine literary devices in detail in other articles on this site.

While the elements of literature will appear in every literary text, not every literary device will.

Now, let’s look at each of these oh-so-crucial elements of literature.

A COMPLETE UNIT ON TEACHING STORY ELEMENTS

☀️This HUGE resource provides you with all the TOOLS, RESOURCES , and CONTENT to teach students about characters and story elements.

⭐ 75+ PAGES of INTERACTIVE READING, WRITING and COMPREHENSION content and NO PREPARATION REQUIRED.

Plot refers to all related things that happen in the sequence of a story. The shape of the plot comes from the order of these events and consists of several distinct aspects that we’ll look at in turn.

The plot comprises a series of cause-and-effect events that lead the reader from the story’s beginning, through the middle, to the story’s ending (though sometimes the chronological order is played with for dramatic effect).

Exposition: This is the introduction of the story. Usually, it will be where the reader acquires the necessary background information they’ll need to follow the various plot threads through to the end. This is also where the story’s setting is established, the main characters are introduced to the reader, and the central conflict emerges.

Conflict: The conflict of the story serves as the focus and driving force of most of the story’s actions. Essentially, conflict consists of a central (and sometimes secondary) problem. Without a problem or conflict, there is no story. Conflict usually takes the form of two opposing forces. These can be external forces or, sometimes, these opposing forces can take the form of an internal struggle within the protagonist or main character.

Rising Action: The rising action of the narrative begins at the end of the exposition. It usually forms most of the plot and begins with an inciting incident that kick-starts a series of cause-and-effect events. The rising action builds on tension and culminates in the climax.

Climax: After introducing the problem or central conflict of the story, the action rises as the drama unfolds in a series of causes and effects . These events culminate in the story’s dramatic high point, known as the climax. This is when the tension finally reaches its breaking point

Falling Action: This part of the narrative comprises the events that happen after the climax. Things begin to slow down and work their way towards the story’s end, tying up loose ends on the way. We can think of the falling action as a de-escalation of the story’s drama.

Resolution: This is the final part of the plot arc and represents the closing of the conflict and the return of normality – or new normality – in the wake of the story’s events. Often, this takes the form of a significant change within the main character. A resolution restores balance and order to the world or brings about a new balance and order.

PRACTICE ACTIVITY: PLOT

Discuss a well-known story in class. Fairytales are an excellent resource for this activity. Students must name a scene from each story that corresponds to each of the sections of the plot as listed above: exposition, conflict, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution.

Setting consists of two key elements: space and time. Space refers to the where of the story, most often the geographical location where the action of the story takes place. Time refers to the when of the story. This could be a historical period, the present, or the future.

The setting has other aspects for the reader or writer to consider. For example, drilling down from the broader time and place, elements such as the weather, cultural context, physical surroundings, etc., can be important.

The setting is a crucial part of a story’s exposition and is often used to establish the mood of the story. A carefully crafted setting can be used to skillfully hint at the story’s theme and reveal some aspects of the various characters.

PRACTICE ACTIVITY: SETTING

Gather up a variety of fiction and nonfiction texts. Students should go through the selected texts and write two sentences about each that identify the settings of each. The sentences should make clear where and when the stories take place.

3. CHARACTER

A story’s characters are the doers of the actions. Characters most often take human form, but, on occasion, a story can employ animals, fantastical creatures, and even inanimate objects as characters.

Some characters are dynamic and change over the course of a story, while others are static and do not grow or change due to the story’s action.

There are many different types of characters to be found in works of literature, and each serves a different function.

Now, let’s look at some of the most important of these.

Protagonist

The protagonist is the story’s main character. The story’s plot centers around these characters, who are usually sympathetic and likable to the reader; that is, they are most often the ‘hero’ of the story.

The antagonist is the bad guy or girl of the piece. Most of the plot’s action is borne of the conflict between the protagonist and the antagonist.

Flat Character

Flat characters are one-dimensional characters that are purely functional in the story. They are more a sketch than a detailed portrait, and they help move the action along by serving a simple purpose. We aren’t afforded much insight into the interior lives of such characters.

Rounded Character

Unlike flat characters, rounded characters are more complex and drawn in more detail by the writer. As well as being described in comprehensive physical detail, we will gain an insight into the character’s interior life, their hopes, fears, dreams, desires, etc.

Choose a play that has been studied in class. Students should look at the character list and then categorize each of the characters according to the abovementioned types: protagonist, antagonist, flat character, or rounded character. As an extension, can the students identify whether each character is dynamic or static by the end of the tale?

4: POINT OF VIEW

Point of view in literature refers to the perspective through which you experience the story’s events.

There are various advantages and disadvantages to the different points of view available for the writer, but they can all be usefully categorized according to whether they’re first-person, second-person, or third-person points of view.

Now, let’s look at some of the most common points of view in each category.

First Person

The key to recognizing this point of view is using pronouns such as I, me, my, we, us, our, etc. There are several variations of the first-person narrative , but they all have a single person narrating the story’s events either as it unfolds or in the past tense.

When considering a first-person narrative, the first question to ask is who is the person telling the story. Let’s look at two main types of the first-person point of view.

First-Person Protagonist : This is when the story’s main character relates the action first-hand as he or she experiences or experienced it. As the narrator is also the main character, the reader is placed right at the center of the action and sees events unfold through the main character’s eyes.

First-Person Periphery: In this case, we see the story unfold, not from the main character’s POV but from the perspective of a secondary character with limited participation in the story itself.

Second Person: This perspective is uncommon. Though it is hard to pull off without sounding corny, you will find it in some books, such as those Choose Your Own Adventure-type books. You can recognize this perspective by using the second person pronoun ‘you’.

Third Person Limited: From this perspective, we see events unfold from the point of view of one person in the story. As the name suggests, we are limited to seeing things from the perspective of the third-person narrator and do not gain insight into the internal life of the other characters other than through their actions as described by the third-person narrator (he, she, they, etc.).

Third Person Omniscient: The great eye in the sky! The 3rd person omniscient narrator, as the name suggests, knows everything about everyone. From this point of view, nothing is off-limits. This allows the reader to peek behind every curtain and into every corner of what is going on as the narrator moves freely through time and space, jumping in and out of the characters’ heads along the way.

Advantages and Disadvantages

As we’ve mentioned, there are specific advantages and disadvantages to each of the different points of view. While the third-person omniscient point of view allows the reader full access to each character, the third-person limited point of view is great for building tension in a story as the writer can control what the reader knows and when they know it.

The main advantage of the first-person perspective is that it puts the reader into the head of the narrator. This brings a sense of intimacy and personal detail to the story.

We have a complete guide to point of view here for further details.

PRACTICE ACTIVITY: POINT OF VIEW

Take a scene from a story or a movie that the student is familiar with (again, fairytales can serve well here). Students must rewrite the scene from each of the different POVs listed above: first-person protagonist, first-person periphery, second-person, third-person limited, and third-person omniscient. Finally, discuss the advantages and disadvantages of writing the scene from each POV. Which works best and why?

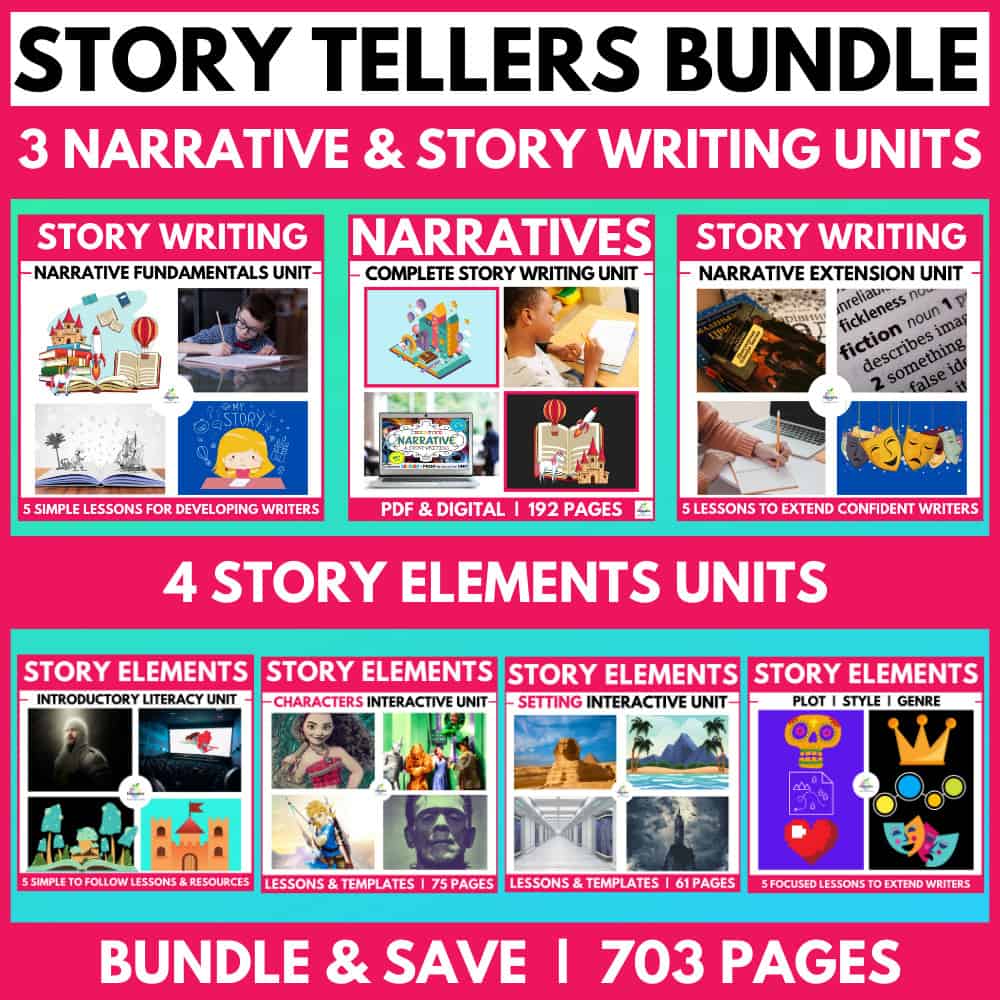

THE STORY TELLERS BUNDLE OF TEACHING RESOURCES

A MASSIVE COLLECTION of resources for narratives and story writing in the classroom covering all elements of crafting amazing stories. MONTHS WORTH OF WRITING LESSONS AND RESOURCES, including:

If the plot refers to what happens in a story, then the theme is to do with what these events mean.

The theme is the big ideas explored in a work of literature. These are often universal ideas that transcend the limits of culture, ethnicity, or language. The theme is the deeper meaning behind the events of the story.

Notably, the theme of a piece of writing is not to be confused with its subject. While the subject of a text is what it is about, the theme is more about how the writer feels about that subject as conveyed in the writing.

It is also important to note that while all works of literature have a theme, they never state that theme explicitly. Although many works of literature deal with more than one theme, it’s usually possible to detect a central theme amid the minor ones.

The most commonly asked question about themes from students is, ‘ How do we work out what the theme is? ’

The truth is, how easy or how difficult it will be to detect a work’s theme will vary significantly between different texts. The ease of identification will depend mainly on how straightforward or complex the work is.

Students should look for symbols and motifs within the text to identify the theme. Especially symbols and motifs that repeat.

Students must understand that symbols are when one thing is used to stand for another. While not all symbols are related to the text’s theme, when symbols are used repeatedly or found in a cluster, they usually relate to a motif. This motif will, in turn, relate to the theme of the work.

Of course, this leads to the question: What exactly is a motif?

A motif is a recurring idea or an element that has symbolic significance. Uncovering this significance will reveal the theme to a careful reader.

We can further understand the themes as concepts and statements. Concepts are the broad categories or issues of the work, while statements are the position the writer takes on those issues as expressed in the text.

Here are some examples of thematic concepts commonly found in literature:

- Forgiveness

When discussing a work’s theme in detail, identifying the thematic concept will not be enough. Students will need to explore what the thematic statements are in the text. That is, they need to identify the opinions the writer expresses on the thematic concepts in the text.

For example, we might identify that a story is about forgiveness, that is, that forgiveness is the primary thematic concept. When we identify what the work says about forgiveness, such as it is necessary for a person to move on with their life, we identify a thematic statement.

PRACTICE ACTIVITY: THEME

Again, choose familiar stories to work with. For each story, identify and write the thematic concept and statement. For more complex stories, multiple themes may need to be identified.

AN EXCELLENT VIDEO TUTORIAL ON STORY ELEMENTS

Tone refers to how the theme is treated in a work. Two works may have the same theme, but each may adopt a different tone in dealing with that theme. For example, the tone of a text can be serious, comical, formal, informal, gloomy, joyful, sarcastic, or sentimental, to name but eight.

The tone that the writer adopts influences how the reader reads that text. It informs how the reader will feel about the characters and events described.

Tone helps to create the mood of the piece and gives life to the story as a whole.

PRACTICE ACTIVITY: TONE

Find examples of texts that convey each of the eight tones listed above: serious, comical, formal, informal, gloomy, joyful, sarcastic, and sentimental. Give three examples from each text that convey that specific tone. The examples can be drawn from direct quotations of the narrative or dialogue or a commentary on the structure of the text.

Conclusion:

Though the essential elements of literature are few in number, they can take a lifetime to master. The more experience a student gains in creating and analyzing texts regarding these elements, the more adept they will become in their use.

Time invested in this area will reap rich rewards regarding the skill with which a student can craft a text and the level of enjoyment and meaning they can derive from their reading.

Time well spent, for sure.

TEACHING RESOURCES

Other great articles related to elements of literature.

7 ways to write great Characters and Settings | Story Elements

Teaching The 5 Story Elements: A Complete Guide for Teachers & Students

Short Story Writing for Students and Teachers

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Introduction

Reviewing the essential elements of literature will give you a clear picture as to how to interpret stories that you are reading and also how to implement various elements in your own essays, narratives, and creative works.

Analyzing things like setting, plot, mood, theme, and point of view will allow you to dig deeper to determine the author’s true intention behind his or her writing. You will also learn to consider the type of narrator, their reliability, and whether or not they have objective, limited, or omniscient views.

In addition to the author’s intention for their writing, you will also consider the style within the work. Setting, characterization, and rising action will hold an important role in analyzing any piece of literature.

The activities within this section will give you a solid understanding of what each of the elements of literature mean, how they work within a piece of writing, and questions to ask yourself (while reading or writing) to address each category.

Elements of Literature

How to analyze a short story, what is a short story.

A short story is a work of short, narrative prose that is usually centered around one single event. It is limited in scope and has an introduction, body and conclusion. Although a short story has much in common with a novel (See How to Analyze a Novel), it is written with much greater precision. You will often be asked to write a literary analysis. An analysis of a short story requires basic knowledge of literary elements. The following guide and questions may help you:

Setting is a description of where and when the story takes place. In a short story there are fewer settings compared to a novel. The time is more limited. Ask yourself the following questions:

- How is the setting created? Consider geography, weather, time of day, social conditions, etc.

- What role does setting play in the story? Is it an important part of the plot or theme? Or is it just a backdrop against which the action takes place?

Study the time period, which is also part of the setting, and ask yourself the following:

- When was the story written?

- Does it take place in the present, the past, or the future?

- How does the time period affect the language, atmosphere or social circumstances of the short story?

Characterization

Characterization deals with how the characters in the story are described. In short stories there are usually fewer characters compared to a novel. They usually focus on one central character or protagonist. Ask yourself the following:

- Who is the main character?

- Are the main character and other characters described through dialogue – by the way they speak (dialect or slang for instance)?

- Has the author described the characters by physical appearance, thoughts and feelings, and interaction (the way they act towards others)?

- Are they static/flat characters who do not change?

- Are they dynamic/round characters who DO change?

- What type of characters are they? What qualities stand out? Are they stereotypes?

- Are the characters believable?

Plot and structure

The plot is the main sequence of events that make up the story. In short stories the plot is usually centered around one experience or significant moment. Consider the following questions:

- What is the most important event?

- How is the plot structured? Is it linear, chronological or does it move around?

- Is the plot believable?

Narrator and Point of view

The narrator is the person telling the story. Consider this question: Are the narrator and the main character the same?

By point of view we mean from whose eyes the story is being told. Short stories tend to be told through one character’s point of view. The following are important questions to consider:

- Who is the narrator or speaker in the story?

- Does the author speak through the main character?

- Is the story written in the first person “I” point of view?

- Is the story written in a detached third person “he/she” point of view?

- Is there an “all-knowing” third person who can reveal what all the characters are thinking and doing at all times and in all places?

Elements of Literature with Mr. Taylor (Part 1). Authored by: Kenny Taylor. Located at: https://youtu.be/9E6JJojgCew. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

How to Analyze a Short Story. Authored by: Carol Dwankowski. Provided by: ndla.no. Located at: http://ndla.no/en/node/9075?fag=42&meny=102113. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

Conflict or tension is usually the heart of the short story and is related to the main character. In a short story there is usually one main struggle.

- How would you describe the main conflict?

- Is it an internal conflict within the character?

- Is it an external conflict caused by the surroundings or environment the main character finds himself/herself in?

The climax is the point of greatest tension or intensity in the short story. It can also be the point where events take a major turn as the story races towards its conclusion. Ask yourself:

- Is there a turning point in the story?

- When does the climax take place?

The theme is the main idea, lesson, or message in the short story. It may be an abstract idea about the human condition, society, or life. Ask yourself:

- How is the theme expressed?

- Are any elements repeated and therefore suggest a theme?

- Is there more than one theme?

The author’s style has to do with the his or her vocabulary, use of imagery, tone, or the feeling of the story. It has to do with the author’s attitude toward the subject. In some short stories the tone can be ironic, humorous, cold, or dramatic.

- Is the author’s language full of figurative language?

- What images are used?

- Does the author use a lot of symbolism? Metaphors (comparisons that do not use “as” or “like”) or similes (comparisons that use “as” or “like”)?

Elements of Literature with Mr. Taylor (Part 2). Authored by: Kenny Taylor. Located at: https://youtu.be/O7c_SjKcGbE. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

To review, considering the various elements of literature is essential while analyzing a work of literature. Things like setting, plot, mood, theme, and point of view could give you a better idea of an author’s intention. The type of narrator, their reliability, and their type of view (objective, limited, or omniscient) will allow you to dive deeper into the trustworthiness of the information they provide.

In addition to the author’s intention for their writing, you will also consider the style within the work. Setting, characterization, and rising action will hold an important role in analyzing literature.

The elements of literature within this section are applicable as you are reading or writing on your own. You should be able to apply the definitions for the elements of literature, describe how they work within a piece of writing, and understand the questions to ask yourself while reading and/or writing.

ENG134 – Literary Genres Copyright © by The American Women's College and Jessica Egan is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

4.5: How to Analyze Fiction - Elements of Literature

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 40396

- Heather Ringo & Athena Kashyap

- City College of San Francisco via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Elements of Literature

Before you dive straight into your analysis of symbolism, diction, imagery, or any other rhetorical device, you need to have a grasp of the basic elements of what you're reading. When we read critically or analytically, we might disregard character, plot, setting, and theme as surface elements of a text. Aside from noting what they are and how they drive a story, we sometimes don't pay much attention to these elements. However, characters and their interactions can reveal a great deal about human nature. Plot can act as a stand-in for real-world events just as setting can represent our world or an allegorical one. Theme is the heart of literature, exploring everything from love and war to childhood and aging.

With this in mind, you can begin your examination of literature with a “who, what, when, where, how?” approach. Ask yourself “Who are the characters?” “What is happening?” “When and where is it happening?” and “How does it happen?” The answers will give you character (who), plot (what and how), and setting (when and where). When you put these answers together, you can begin to figure out theme, and you will have a solid foundation on which to base your analysis.

We will be exploring several of the following literary elements in the following pages so that we can have a common vocabulary to talk about fiction:

- Rhetorical Devices

Here are a few questions to ask when looking at some of the main elements of fiction. We will be looking at each of these in more detail in the following pages.

Setting is a description of where and when the story takes place.

- Geography, weather, time of day, social conditions?

- What role does setting play in the story? Is it an important part of the plot or theme? Or is it just a backdrop against which the action takes place?

- Study the time period which is also part of the setting

- Does it take place in the present, the past, or the future?

- How does the time period affect the language, atmosphere, or social circumstances of the novel?

Characterization

Characterization deals with how the characters are described.

- through dialogue?

- by the way they speak?

- physical appearance? thoughts and feelings?

- interaction – the way they act towards other characters?

- Are they static characters who do not change?

- Do they develop by the end of the story?

- What type of characters are they?

- What qualities stand out?

- Are they stereotypes?

- Are the characters believable?

Plot and structure

The plot is the main sequence of events that make up the story.

- What are the most important events?

- How is the plot structured? Is it linear and chronological or does it move back and forth?

- Are there turning points, a climax, and/or an anticlimax?

- Is the plot believable?

Narrator and Point of View

The narrator is the person telling the story. Point of view : whose eyes the story is being told through.

- Who is the narrator or speaker in the story?

- Is the narrator the main character?

- Does the author speak through one of the characters?

- Is the story written in the first person “I” point of view?

- Is the story written in a detached third person “he/she/they” point of view?

- Is the story written in an “all-knowing” third person who can reveal what all the characters are thinking and doing at all times and in all places?

Conflict or tension is usually the heart of the novel and is related to the main character.

- Is it internal where the character suffers inwardly?

- Is it external, caused by the surroundings or environment the main character finds themself in?

The theme is the main idea, lesson, or message in the novel. It is usually an abstract, universal idea about the human condition, society or life, to name a few.

- How does the theme shine through in the story?

- Are any elements repeated that may suggest a theme?

- What other themes are there?

The author’s style has to do with the author’s vocabulary, use of imagery, tone, or feeling of the story. It has to do with his attitude towards the subject. In some novels the tone can be ironic, humorous, cold, or dramatic.

- Is the text full of figurative language?

- Does the author use a lot of symbolism? Metaphors, similes? An example of a metaphor is when someone says, "My love, you are a rose." An example of a simile is "My darling, you are like a rose."

- What images are used?

Your literary analysis of a novel will often be in the form of an essay or book report where you will be asked to give your opinions of the novel at the end. To conclude, choose the elements that made the greatest impression on you. Point out which characters you liked best or least and always support your arguments. Try to view the novel as a whole and try to give a balanced analysis.

These are the Elements of Literature, the things that make up every story. This is the first of two videos.

Video 4.5.1 : Elements of literature with Mr. Taylor: Part I

Video 4.5.2 Elements of literature with Mr. Taylor: Part II

Contributors and Attributions

- Adapted from Writing About Literature: The Basics by CK-12, license CC-BY-NC

- Adapted from How to Analyze a Novel by Carol Dwankowski, provided by NDLA, license CC-BY-SA

Make sure to remember your password. If you forget it there is no way for StudyStack to send you a reset link. You would need to create a new account. Your email address is only used to allow you to reset your password. See our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service .

Already a StudyStack user? Log In

Unit III test reveiw

Bob jones elements of literature unit 3 test review.

Use these flashcards to help memorize information. Look at the large card and try to recall what is on the other side. Then click the card to flip it. If you knew the answer, click the green Know box. Otherwise, click the red Don't know box.

When you've placed seven or more cards in the Don't know box, click "retry" to try those cards again.

If you've accidentally put the card in the wrong box, just click on the card to take it out of the box.

You can also use your keyboard to move the cards as follows:

- SPACEBAR - flip the current card

- LEFT ARROW - move card to the Don't know pile

- RIGHT ARROW - move card to Know pile

- BACKSPACE - undo the previous action

If you are logged in to your account, this website will remember which cards you know and don't know so that they are in the same box the next time you log in.

When you need a break, try one of the other activities listed below the flashcards like Matching, Snowman, or Hungry Bug. Although it may feel like you're playing a game, your brain is still making more connections with the information to help you out.

To see how well you know the information, try the Quiz or Test activity.

Find what you need to study

📚 AP English Literature

📌 exam date: may 8, 2024.

Cram Finales

Study Guides

Practice Questions

AP Cheatsheets

Study Plans

Attend a live cram event

Review all units live with expert teachers & students

AP English Lit Unit 3 Study Guides

Unit 3 – intro to longer fiction & drama.

Unit 3 Overview: Introduction to Longer Fiction and Drama

written by Minna Chow

Interpreting character description and perspective

Character evolution throughout a narrative

Conflict and plot development

Interpreting symbolism

Identifying evidence and supporting literary arguments

Additional Resources

Study tools.

2024 AP English Literature Exam Guide

15 min read

written by Emery

Frequently Asked Questions

Most Frequently Cited on the AP English Literature Exam

What Is Poetry and How Can It Be Analyzed?

AP Lit Reading List

10 min read

What is Classic Literature?

How Can I Be Prepared for the AP English Literature FRQs?

written by Samantha Himegarner

Best AP English Literature Quizlet Decks by Unit

written by Brandon Wu

Exam Skills

Score Higher on AP Literature 2024: MCQ Tips from Students

Score Higher on AP Literature 2024: Tips for FRQ 1 (Poetry Analysis)

Score Higher on AP Literature 2024: Tips for FRQ 2 (Prose Fiction Analysis)

Score Higher on AP Literature 2024: Tips for FRQ 3 (Literary Argument)

AP Lit Prose Analysis Practice Essays & Feedback

26 min read

written by Candace Moore

Short Fiction Overview

17 min read

written by Laura Walton

AP Cram Sessions 2021

Download AP Literature Cheat Sheet PDF Cram Chart

🌶️ AP Lit Cram Review: Long Fiction I

streamed by Kevin Coughlin

AP English Literature Cram Unit 1: Short Fiction I

slides by Kevin Coughlin

🌶️ AP Lit Cram Review: Unit 2: Poetry I

AP English Literature Cram Unit 2: Poetry I

AP English Literature Cram Unit 3: Longer Fiction or Drama I

Live Cram Sessions 2020

Function of Structure - Slides

slides by Candace Moore

Prose Analysis: Foundation of Function

streamed by Candace Moore

Explaining Figurative Language - Slides

Prose Analysis: Figuratively Speaking

Prose-based Argument: What + Where = Why

Lit Cram 3 - Slides

Previous Exam Prep

Intro to AP Lit for Teachers - Slides

Intro to AP Lit for Teachers

What Lit Is: Exam and Course Overview

streamed by Laura Walton

What Lit Is: Exam and Course Overview - Slides

slides by Laura Walton

Stay Connected

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.

AP® and SAT® are trademarks registered by the College Board, which is not affiliated with, and does not endorse this website.

Literature Review: 3 Essential Ingredients

The theoretical framework, empirical research and research gap

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewer: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | July 2023

Writing a comprehensive but concise literature review is no simple task. There’s a lot of ground to cover and it can be challenging to figure out what’s important and what’s not. In this post, we’ll unpack three essential ingredients that need to be woven into your literature review to lay a rock-solid foundation for your study.

This post is based on our popular online course, Literature Review Bootcamp . In the course, we walk you through the full process of developing a literature review, step by step. If it’s your first time writing a literature review, you definitely want to use this link to get 50% off the course (limited-time offer).

Overview: Essential Ingredients

- Ingredients vs structure

- The theoretical framework (foundation of theory)

- The empirical research

- The research gap

- Summary & key takeaways

Ingredients vs Structure

As a starting point, it’s important to clarify that the three ingredients we’ll cover in this video are things that need to feature within your literature review, as opposed to a set structure for your chapter . In other words, there are different ways you can weave these three ingredients into your literature review. Regardless of which structure you opt for, each of the three components will make an appearance in some shape or form. If you’re keen to learn more about structural options, we’ve got a dedicated post about that here .

1. The Theoretical Framework

Let’s kick off with the first essential ingredient – that is the theoretical framework , also called the foundation of theory .

The foundation of theory, as the name suggests, is where you’ll lay down the foundational building blocks for your literature review so that your reader can get a clear idea of the core concepts, theories and assumptions (in relation to your research aims and questions) that will guide your study. Note that this is not the same as a conceptual framework .

Typically you’ll cover a few things within the theoretical framework:

Firstly, you’ll need to clearly define the key constructs and variables that will feature within your study. In many cases, any given term can have multiple different definitions or interpretations – for example, different people will define the concept of “integrity” in different ways. This variation in interpretation can, of course, wreak havoc on how your study is understood. So, this section is where you’ll pin down what exactly you mean when you refer to X, Y or Z in your study, as well as why you chose that specific definition. It’s also a good idea to state any assumptions that are inherent in these definitions and why these are acceptable, given the purpose of your study.

Related to this, the second thing you’ll need to cover in your theoretical framework is the relationships between these variables and/or constructs . For example, how does one variable potentially affect another variable – does A have an impact on B, B on A, and so on? In other words, you want to connect the dots between the different “things” of interest that you’ll be exploring in your study. Note that you only need to focus on the key items of interest here (i.e. those most central to your research aims and questions) – not every possible construct or variable.

Lastly, and very importantly, you need to discuss the existing theories that are relevant to your research aims and research questions . For example, if you’re investigating the uptake/adoption of a certain application or software, you might discuss Davis’ Technology Acceptance Model and unpack what it has to say about the factors that influence technology adoption. More importantly, though, you need to explain how this impacts your expectations about what you will find in your own study . In other words, your theoretical framework should reveal some insights about what answers you might expect to find to your research questions .

If this sounds a bit fluffy, don’t worry. We deep dive into the theoretical framework (as well as the conceptual framework) and look at practical examples in Literature Review Bootcamp . If you’d like to learn more, take advantage of the limited-time offer (60% off the standard price).

Need a helping hand?

2. The Empirical Research

Onto the second essential ingredient, which is empirical research . This section is where you’ll present a critical discussion of the existing empirical research that is relevant to your research aims and questions.

But what exactly is empirical research?

Simply put, empirical research includes any study that involves actual data collection and analysis , whether that’s qualitative data, quantitative data, or a mix of both . This contrasts against purely theoretical literature (the previous ingredient), which draws its conclusions based exclusively on logic and reason , as opposed to an analysis of real-world data.

In other words, theoretical literature provides a prediction or expectation of what one might find based on reason and logic, whereas empirical research tests the accuracy of those predictions using actual real-world data . This reflects the broader process of knowledge creation – in other words, first developing a theory and then testing it out in the field.

Long story short, the second essential ingredient of a high-quality literature review is a critical discussion of the existing empirical research . Here, it’s important to go beyond description . You’ll need to present a critical analysis that addresses some (if not all) of the following questions:

- What have different studies found in relation to your research questions ?

- What contexts have (and haven’t been covered)? For example, certain countries, cities, cultures, etc.

- Are the findings across the studies similar or is there a lot of variation ? If so, why might this be the case?

- What sorts of research methodologies have been used and how could these help me develop my own methodology?

- What were the noteworthy limitations of these studies?

Simply put, your task here is to present a synthesis of what’s been done (and found) within the empirical research, so that you can clearly assess the current state of knowledge and identify potential research gaps , which leads us to our third essential ingredient.

The Research Gap

The third essential ingredient of a high-quality literature review is a discussion of the research gap (or gaps).

But what exactly is a research gap?

Simply put, a research gap is any unaddressed or inadequately explored area within the existing body of academic knowledge. In other words, a research gap emerges whenever there’s still some uncertainty regarding a certain topic or question.

For example, it might be the case that there are mixed findings regarding the relationship between two variables (e.g., job performance and work-from-home policies). Similarly, there might be a lack of research regarding the impact of a specific new technology on people’s mental health. On the other end of the spectrum, there might be a wealth of research regarding a certain topic within one country (say the US), but very little research on that same topic in a different social context (say, China).

These are just random examples, but as you can see, research gaps can emerge from many different places. What’s important to understand is that the research gap (or gaps) needs to emerge from your previous discussion of the theoretical and empirical literature . In other words, your discussion in those sections needs to start laying the foundation for the research gap.

For example, when discussing empirical research, you might mention that most studies have focused on a certain context , yet very few (or none) have focused on another context, and there’s reason to believe that findings may differ. Or you might highlight how there’s a fair deal of mixed findings and disagreement regarding a certain matter. In other words, you want to start laying a little breadcrumb trail in those sections so that your discussion of the research gap is firmly rooted in the rest of the literature review.

But why does all of this matter?

Well, the research gap should serve as the core justification for your study . Through your literature review, you’ll show what gaps exist in the current body of knowledge, and then your study will then attempt to fill (or contribute towards filling) one of those gaps. In other words, you’re first explaining what the problem is (some sort of gap) and then proposing how you’ll solve it.

Key Takeaways

To recap, the three ingredients that need to be mixed into your literature review are:

- The foundation of theory or theoretical framework

- The empirical or evidence-based research

As we mentioned earlier, these are components of a literature review and not (necessarily) a structure for your literature review chapter. Of course, you can structure your chapter in a way that reflects these three components (in fact, in some cases that works very well), but it’s certainly not the only option. The right structure will vary from study to study , depending on various factors.

If you’d like to get hands-on help developing your literature review, be sure to check out our private coaching service , where we hold your hand through the entire research journey, step by step.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

very good , as the first writer of the thesis i will need ur advise . please give me a piece of idea on topic -impact of national standardized exam on students learning engagement . Thank you .

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Elements of literature. Third course

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

2,297 Views

22 Favorites

Better World Books

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by ttscribe22.hongkong on December 11, 2018

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

Module 2: Literary Conventions

Elements of literature.

These are the Elements of Literature, the things that make up every story. This is the first of two videos.

These are the elements of literature with Mr. Taylor.

- Elements of Literature with Mr. Taylor (Part 1). Authored by : Kenny Taylor. Located at : https://youtu.be/9E6JJojgCew . License : All Rights Reserved . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- Elements of Literature with Mr. Taylor (Part 2). Authored by : Kenny Taylor. Located at : https://youtu.be/O7c_SjKcGbE . License : All Rights Reserved . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

Doc’s Things and Stuff

Section 4.3: Elements of a Literature Review

In crafting a comprehensive literature review, various critical elements ensure clarity, relevance, and meaningful contributions to the academic conversation. Beginning by introducing the overarching problem area provides context for readers while highlighting specific, influential studies that underscore their significance in the broader dialogue.

Table of Contents

Landmark and replication studies offer insight into foundational works and their subsequent validations. Leveraging existing review articles and addressing side issues allows for a more expansive coverage while acknowledging gaps and inconsistencies adds depth and honesty. Finally, justifying the importance of your study solidifies its place within the academic landscape. The subsequent sections delve deeper into each of these pivotal components, providing a roadmap for an effective literature review.

- How is a stand-alone scientific literature review different from a research proposal?

Beginning with the Problem Area

When embarking on a literature review, particularly within the realms of the social and behavioral sciences, it is paramount to ground readers with a clear understanding of the overarching problem area under investigation. This sets the stage for them, offering a backdrop against which all subsequent discussions will be framed. By first introducing the broader issues or challenges pertinent to the field, you lay the groundwork for a systematic exploration that gradually narrows down to the crux of the matter. This transition from the general to the specific serves as a funnel, guiding readers through the complexities of the subject matter, ensuring they grasp the wider context before diving into the intricacies.

However, a word of caution is in order. While it’s essential to commence with a generalized overview, it’s equally critical to strike a balance, ensuring that these introductory statements aren’t so broad as to become ambiguous or nebulous. The introduction should not merely brush the surface or be too encompassing, but rather should subtly hint at the specific topic or niche that will be the focus of the review. In the vast and multifaceted world of social and behavioral sciences, clarity in this initial phase is key, providing readers with a beacon that illuminates the path ahead, ensuring they remain oriented and engaged as they journey deeper into the review.

Importance of Specific Studies

When you’re looking at a lot of research, you’ll notice that some studies stand out more than others. That’s because certain studies have done something really special or different that makes them important. So, when you’re writing about what you’ve found, it’s a good idea to point out these standout studies to your readers. One thing to look for is if a study is super big. Bigger studies can give a lot of information and can help us see the bigger picture.

Another thing to think about is whether a study has changed the way people do things, like making new rules or policies. This shows that the study had some big real-world effects. Also, pay attention to how the study was done. If they used a really good method to get their information, that’s a plus! It means their findings are probably more trustworthy. So, when you tell your readers about these studies, they’ll know why they’re a big deal and why they should care about them.

Landmark Studies

When you dive into your research, you’ll find some studies that stand out as game-changers. These are known as “landmark” or “classic” studies. They’re like those foundational books or moments in history that everyone should know about because they’ve made a big impact. These studies have shared groundbreaking ideas or findings that have become key talking points in the field. They’ve helped shape the direction of research and have given others a solid base to build on.

Now, why are these landmark studies so important? They often introduce ideas or terms that many people in the field adopt and use. Imagine a foundational book in a subject that everyone refers to or quotes. In research, these landmark studies have similar significance. They pave the way for new ways of thinking and become a standard reference. So, when you’re writing your literature review, highlighting these significant studies helps your readers grasp what’s been influential and foundational in the area you’re exploring.

Replication Studies

Landmark studies are a big deal in research, kind of like setting a trend everyone wants to follow. Because they’re so influential, they often lead to more research where people try to see if they can get the same results. These are called “replication studies.” It’s like double-checking to make sure the findings from the big landmark study weren’t just a one-time thing. These replication studies help us see if the results from the original study are solid and can be counted on in different situations or with different groups of people.

Now, when talking about these replication studies, it’s important to point out whether they back up the original findings or if they found something different. Imagine telling a story and having a friend share it too. If both stories match up, it’s likely true. But if they’re different, people might raise an eyebrow. Similarly, if a replication study supports the original findings, it strengthens the case. If it doesn’t, it’s worth digging into why. Highlighting this in your literature review helps readers understand how trustworthy and reliable the original study’s findings are.

Utilizing Review Articles

When you’re diving into your research, you might find someone else has already written a review on your topic. It’s like finding out someone made a movie with a similar plot to the one you’ve been thinking about. But that’s okay! Use it to your advantage and weave it into your own work. Here’s what you should think about:

First, figure out how your review brings something new to the table. Is yours fresher with more up-to-date info? Maybe yours covers more ground or perhaps it hones in on a specific area the earlier one missed. The key is to make sure you’re not just rehashing what’s already been said. Think about it – if you’re reading two papers and they both say the same thing, you’ll probably get bored or wonder why the second person even bothered. So, aim to give fresh insights. Just repeating what’s already out there won’t make your paper stand out. It’s like baking – if you’re using the same recipe and ingredients as everyone else, your cake won’t stand out. But add a twist, and it becomes memorable! Your review should do the same.

Alright, so while finding a review article on your topic might seem like someone beat you to the punch, there’s a silver lining. Think of that review article as a treasure map. One of the most valuable sections of any review article is the reference page or bibliography. For student writers, this is pure gold!

Here’s the thing: The reference page of an existing review article is like a curated list of key sources and studies related to your topic. Instead of scouring the internet or library databases for hours, you’ve got a starting point handed to you on a silver platter. It can point you to some of the most important works in the field, saving you a ton of time and effort. Plus, by exploring these sources, you can gain a deeper understanding of your topic, which will help make your own review more robust.

But wait, there’s more! By digging into these references, you can also find gaps or areas that the original review might have missed or not delved deeply into. This gives you a chance to fill in those gaps with your own insights and make your review unique. It’s like having a roadmap where some paths are marked, but you also find some hidden trails to explore on your own. So, don’t just skim through that existing review; use its reference page as a launchpad for your own research.

Reviews on Side Issues

When you’re deep into your research and writing, you’ll often find yourself stumbling upon topics or issues that are super interesting, but not exactly the main focus of your paper. It’s like going on a road trip with a set destination, but spotting some intriguing side roads along the way. You might want to explore them, but you also know you’ve got to stick to your main route.

So, what do you do when you come across these side issues in your research? Instead of taking a full detour or ignoring them entirely, a smart move is to acknowledge them and point your readers to review articles that explore these topics in depth. This way, you’re giving a nod to these interesting side topics without derailing your main argument or discussion.

By directing readers to other review articles, you’re essentially giving them optional reading material. For those super curious or keen on diving deeper, these references can be a treasure trove of additional information. Plus, it shows you’ve done your homework and are aware of the broader landscape of your topic. In short, even if some issues are on the sidelines of your main topic, they can still enrich your paper and offer readers a fuller picture if you handle them wisely.

Here’s an example of how you might format it:

“While the primary focus of this research is on the effects of sunlight on mood, there have been related studies on the impact of artificial lighting that are also noteworthy (see Johnson & Lee, 2019).”

Addressing Gaps in the Literature

Research isn’t just about highlighting what we know; it’s equally vital to point out what we don’t. When you’re delving into a topic, there will often be areas that haven’t been thoroughly studied or questions that remain unanswered. These areas are what we call “gaps” in the literature. Recognizing and pointing out these gaps is essential because it not only shows that you’ve done a comprehensive review of existing work, but it also identifies potential avenues for future studies. Addressing these gaps can lead to new discoveries and deeper insights into the subject matter.

However, you don’t have to identify all these gaps on your own. A valuable approach is to refer to recent articles where other researchers have highlighted gaps in the field. Often, seasoned researchers or authors will note areas that require more exploration in their discussions or conclusions. Citing these observations serves a dual purpose: it supports your claim of a gap in the literature and shows that you’re building on the collective understanding of the research community. But whether you’ve identified the gaps yourself or are building upon insights from other scholars, it’s crucial to be transparent about your sources and methods. This not only bolsters your credibility but also provides a clear perspective for readers and potential future researchers interested in filling those gaps.

Handling Inconsistent Results

Navigating the world of academic research is akin to piecing together a puzzle. And like any puzzle, sometimes the pieces don’t quite fit together perfectly. This is especially true when dealing with inconsistent results across different studies. Differing outcomes can emerge due to a multitude of reasons: varying methodologies, diverse sample populations, or even evolving frameworks and understandings within the discipline itself. It’s important to acknowledge that inconsistencies aren’t necessarily a sign of flawed research, but rather they showcase the complexity and multifaceted nature of many topics.

When presenting your literature review, clarity is paramount. If Study A found X and Study B found Y, ensure you distinctly delineate these findings rather than melding them into an indistinct summary. It’s tempting, especially when faced with a multitude of sources, to generalize or group findings together for simplicity’s sake. However, doing so risks obfuscating the unique contributions and nuances of each study. It’s a bit like describing the plots of two different novels just because they belong to the same genre; while there may be thematic overlaps, the individual stories and their implications can be vastly different.

Furthermore, being transparent about inconsistencies offers readers a comprehensive view of the current landscape of research on that topic. It fosters critical thinking, inviting readers to ponder why such discrepancies exist, and what factors might account for them. Perhaps even more importantly, by laying out these inconsistencies clearly, you provide a foundation for future researchers to dive deeper, exploring these gaps and further advancing the field. So, instead of viewing inconsistent results as a hurdle, treat them as an opportunity to shed light on the rich tapestry of research, with all its intricacies and divergences.

Justifying Your Study

Every piece of academic work, from the shortest essay to the most exhaustive research paper, carries with it a core message or purpose. The finale of your study shouldn’t just be a period at the end of a sentence; it should resonate, offering readers clarity on why your work matters in the grand scheme of things. After all, in a world brimming with endless sources of information, you must answer the pivotal question: Why should anyone dedicate precious time to digesting your paper?

The justification for your study is the compass that directs and gives meaning to your research journey. Perhaps you’ve ventured into uncharted territory, addressing gaps in the existing literature and shedding light on topics previously overshadowed. Or maybe you’ve revisited established theories, questioning their applicability or introducing fresh perspectives that challenge traditional notions. Replicating key studies is also invaluable; by either reaffirming or debunking past results, you contribute to the evolving accuracy and reliability of academic knowledge. And innovation shouldn’t be understated: utilizing novel methods to dissect age-old hypotheses can revitalize discussions, ushering them into contemporary dialogues. At other times, your work might serve as a mediator, aiming to resolve conflicts within the literature by offering a synthesis or a new lens of analysis.

Ultimately, the essence of your justification should translate into a clear takeaway for your readers. It’s not just about stating facts and presenting findings; it’s about weaving a narrative that underscores the relevance and significance of your study in the broader academic conversation. By ensuring readers grasp this importance, you not only validate the worth of your study but also inspire deeper engagement, discussion, and further exploration in your chosen domain.

Things to Avoid

Avoid nonspecific references . There are two purposes to a citation in academic writing: 1) to give credit where it is due, and 2) to demonstrate the breadth of coverage of the paper. A long list of nonspecific cites at the end of a paragraph leaves the reader wondering many things: Are these empirical studies? Are these statements research results or speculation? Are all these studies of equal weight, or do some provide more solid evidence than others do? Introduce studies with specificity .

Introducing references after the review section . Cite all of your references in the literature review of your document. By the time the readers get to your discussion section, they should already have been introduced to all the important works on your topic. Make sure your literature review is comprehensive (especially for a thesis or dissertation).

Bad English . Misspellings, capitalization errors, and easily recognizable grammar errors make you look like an idiot. Proofread your paper. Fix your mistakes. If you have less-than-perfect grammar skills, get someone else to help you with editing. Most universities have a writing center where you can get help. (Help with English usage—do not expect writing center personnel to be experts in your field or the APA style!). There are software plugins available that can automate many editing tasks, making your work better quickly. (I personally use Grammarly ).

Overreliance on Direct Quotations . While using direct quotes from sources can be useful, excessive reliance on them can make your paper feel less original. Instead, aim to paraphrase or summarize key points from your sources, integrating them smoothly into your narrative. This not only demonstrates your understanding of the content but also makes the paper more engaging to readers.

Neglecting Contradictory Evidence . Only discussing studies or viewpoints that align with your argument can make your work seem biased. A comprehensive literature review acknowledges all significant perspectives, even those that might contradict your stance. Addressing and counter-arguing such points strengthens your position.

Overuse of Jargon . While academic writing often requires specialized language, avoid excessive use of jargon or overly complex terms that might alienate readers unfamiliar with the terminology. Aim for clarity and simplicity, providing definitions or explanations for terms that aren’t widely recognized outside your specific field.

Lack of Structure and Flow . It’s crucial to organize your literature review or paper logically. Ensure there’s a clear structure, with ideas and points flowing seamlessly from one to the next. This helps readers follow your argument and understand the progression of your discussion.

Ignoring Updates in Your Style . Publication guidelines, including the APA and Chicago style, occasionally undergo revisions. Ensure you’re using the most up-to-date version of the style guide when formatting your paper. If your professor provides a template, use it! Even if it’s wrong, your professor thinks it is correct, and that is all that matters for your grade.

Reliance on a Limited Range of Sources . Diversifying your sources ensures a richer and more balanced understanding of your topic. Relying too heavily on one type of source, such as only articles from a single journal or only older publications, can limit the breadth of your insights. Ensure you’re exploring a mix of both seminal works and recent studies from various reputable sources.

Using Outdated Sources . In many fields, knowledge and research evolve rapidly. While older articles can provide foundational knowledge, relying heavily on dated sources can make your work seem out of touch with recent developments. As a rule of thumb, prioritize sources published within the last five years to ensure the relevance and currency of your information. If you do choose to cite an older article, there should be a clear justification for its inclusion. For instance, it might be a landmark study that introduced pivotal concepts or findings to the field. However, even in such cases, it’s crucial to contextualize the older source and, where possible, complement it with more recent research that builds upon or critiques that seminal work. This approach ensures that your literature review or paper reflects both the historical context and the current state of the field.

Creating a comprehensive literature review is vital for a meaningful contribution to academic discussions. One should begin by introducing the overarching problem area, setting the stage from a broad overview and progressively honing in on the specific topic, ensuring that the introduction is clear without being overly general or ambiguous.

It’s also crucial to underscore influential studies when discussing the literature. Considerations like the size of the study, its real-world impact, and the soundness of its methodologies can highlight its significance. Among these studies, there are those considered “landmark,” foundational works that have left a lasting imprint on the field. Such studies set the tone and context for subsequent research and are integral to any in-depth literature review.

Equally important are replication studies that aim to reaffirm the findings of these landmark studies. By confirming or challenging the original research’s outcomes, they either solidify the landmark study’s conclusions or suggest alternative perspectives.

One should also not overlook existing review articles on the topic. Even if someone has previously tackled the subject, newer reviews can bring fresh insights, newer data, or different angles. An existing review article can also be a valuable resource, especially its reference page, which provides a curated list of key sources.

As the review progresses, it’s essential to acknowledge side issues and tangential topics, pointing readers towards comprehensive articles on those subjects. This practice gives a holistic view of the research landscape without diverting from the main topic. Acknowledging and addressing gaps in the existing literature adds depth, while pointing out inconsistencies across studies showcases the multifaceted nature of many subjects.

Lastly, justifying the study’s relevance and importance in the academic sphere ensures readers understand its significance, encouraging deeper engagement and future exploration. And throughout, clarity, updated references, and diversified sources are paramount to avoid pitfalls in the literature review process.

You are welcome to print a copy of pages from this Open Educational Resource (OER) book for your personal use. Please note that mass distribution, commercial use, or the creation of altered versions of the content for distribution are strictly prohibited. This permission is intended to support your individual learning needs while maintaining the integrity of the material.

This work is licensed under an Open Educational Resource-Quality Master Source (OER-QMS) License .

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Improve your writing in one of the largest and most successful writing groups online

Join our writing group!

Literary Elements: What are the 7 Elements of Literature?

by Fija Callaghan

Literary elements in storytelling can cause a lot of confusion, and even a bit of fear, among new writers. Once you’re able to recognize the literary elements of a story you’ll realize that they’re present in absolutely everything.

All stories are made up of basic structural building blocks such as plot, character, and theme, whether it’s a riveting Friday night TV series, a two-hundred-thousand-word Dickensian novel of redemption, or a trashy paperback about fifty shades of highly inappropriate workplace relations. Once you understand how these elements of story take shape from our literary elements list, you’ll be able to use them to explore entire worlds of your own.

What are literary elements?

Literary elements are the common structural elements that every story needs to be successful. The seven elements of literature are character, setting, perspective, plot, conflict, theme, and voice. These elements are the building blocks of good stories because if any are missing, the story will feel incomplete and unsatisfying. Applying these elements is critical to crafting an effective story.

Here’s an example of why literary elements matter in storytelling:

The cat sat on the chair is an event. A small, quiet happenstance with a beginning and an ending so closely entwined that you almost can’t tell one from the other.

The cat sat on the dog’s chair is a story.

Why? Because with the addition of one little word, suddenly this quiet happenstance is glowing with possibility. We have our characters—a cat and a dog, whose relationship is gently hinted at with the promise of being further explored. We have our setting—a chair, which has taken on new importance as the central axis of this moment. And, perhaps most importantly, we have our conflict. An inciting moment where two characters want something and we know that these desires can’t exist side by side. This is a story.

All stories come from these basic building blocks that we call “literary elements.” Without them, seeds of a story like this one can’t grow into rich, full narratives.

You may already be able to identify some or all of these literary elements from the stories you’ve experienced throughout your life, whether that’s through reading them or from watching them in films or on television. Once you know what these literary elements of a story are and how they fit together, you’ll be able to create vivid, engaging stories from your own little seeds.

What’s the difference between literary elements vs. literary devices?

Sometimes you’ll see a “literary elements list” or “literary devices list” that toss the two together in one big storytelling melange, but literary elements and literary devices are actually two very distinct things. Let’s take a closer look at each one.

Literary elements

These are things that every single story needs to have in order to exist—they’re the architectural foundation. Without them, your story is like a house without any supports; it’ll collapse into a sad, lifeless pile of rubble, and you’ll hear your parents tossing around unfeeling words like “day job” when talking about your writing.

Literary devices

A literary device , on the other hand, refers to the many tools and literary techniques that a writer uses to bring a story to life for the reader. The difference is like the difference between making a home instead of merely building a house.

You can have a very simple story without any literary devices at all, but it would do little other than serve a functional purpose of showing a beginning, middle, and end. Literary devices are what bring that basic story scaffolding to life for the reader. They’re what make the story yours .

Some of the most common literary devices are things like metaphors, similes, imagery, language, and tons more. By experimenting with different literary devices and literary techniques in your own writing, you open up the full expanse of potential in creating literary works.

Once you’ve got a handle on the literary elements that we’re going to show you and how to apply them to your own narrative, you can check out our lesson on popular literary devices to find ways to bring new richness and depth to your work.

The 7 elements of literature

1. character.

The most fundamental of the literary elements, the root of all storytelling, is this: character .

No matter what species your main character belongs to, what their socio-ethno-economic background is, what planet they come from, or what time period they occupy, your characters will have innate needs and desires that we as human beings can see within ourselves. The longing for independence, the desire to be loved, the need to feel safe are all things that most of us have experienced and can relate to when presented through the filter of story.

The first step to using this literary element is easy, and what most new writers think of when they start thinking about characters. it’s simply asking yourself, who is this person? (And again, I’m using “person” in the broadest possible sense.) What makes them interesting? Why is this protagonist someone I might enjoy reading about?

The second step is a little harder. Ask yourself, what does this person want? To be chosen for their high school basketball team? To get accepted into a university across the country? To find a less stressful job?

The third step is the most difficult, and the most important. Ask yourself what they need . Do they want to join the basketball team because they need the approval of their parents? Do they want to move across the country because they need a fresh start in a new place? Do they want a new job because they need to feel that their contribution is valued?

Once you’re able to answer these questions you’ll already feel the bones of a narrative taking shape.

Types of characters you’ll find in every story

Since character is the primary building block of all good literature, you’ll want your character to be as engaging and true to real life as can be. Let’s take a quick look at some of the different character types you’ll encounter in your story world.

Protagonist

Your protagonist is the main character of your story. Often they’ll be the hero, but not always—antiheroes and complex morally grey leads make for interesting plots, too. This is the character through which your reader goes on a journey and learns the valuable lessons illustrated in your themes (more on theme down below).

Your antagonist is the person standing in the way of your protagonist’s goal. These two central characters have opposing desires, and it’s the conflict born out of that opposition that drives the events of the plot. Sometimes an antagonist will be a villain bent on world destruction, and sometimes it’ll be an average person who simply sees the world in a different way.

Supporting characters