Advisories | Goldlink | Goldmail | D2L | Safety | A-Z Index

Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University

- < Previous

Home > FACULTY-WORKS > ETSU Authors > 14

ETSU Authors Bookshelf

Report Writing for Criminal Justice Professionals

Larry S. Miller , East Tennessee State Universtiy Follow John T. Whitehead , East Tennessee State Universtiy Follow

Download or Purchase

Document Type

Publication date, description.

The criminal justice process is dependent on accurate documentation. Criminal justice professionals can spend 50-75% of their time writing administrative and research reports. Report Writing for Criminal Justice Professionals, Fifth Edition provides practical guidance--with specific writing samples and guidelines--for providing strong reports. Much of the legal process depends on careful documentation and the crucial information that lies within, but most law enforcement, security, corrections, and probation and parole officers have not had adequate training in how to provide well-written, accurate, brief, and complete reports. Report Writing for Criminal Justice Professionals covers everything officers need to learn--from basic English grammar to the difficult but often-ignored problem of creating documentation that will hold up in court. This new edition is updated to include timely information, including extensive coverage of digital reporting, updates on legal issues and privacy rights, and expanded coverage of forensics and scientific reporting.

Citation Information

Miller, Larry S.; and Whitehead, John T.. (Authors). 2015. Report Writing for Criminal Justice Professionals . 5th Edition. Boston, MA: Anderson Publishing is an imprint of Elsevier. ISBN: 9781455777693 http://amzn.com/1455777692

Since January 14, 2016

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

- Collections

- Disciplines

Author Corner

- Digital Scholarship Services

Sponsored by Charles C. Sherrod Library

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

A better path forward for criminal justice

- Download Full Report

Subscribe to Governance Weekly

George Floyd’s death at the hands of police in May 2020 and frequent events like it across America have added new urgency and momentum to the drive to reform our criminal justice system. Unfortunately, the debate has too often collapsed into an unhelpful binary: “support the blue” or “abolish the police.” Either of these poles would tend to have a negative impact on the very communities that have suffered disproportionately under our current criminal justice and law enforcement policies. Excessive policing and use of force, on one hand, and less public safety and social service resources on the other, can both be detrimental to communities that are exposed to high levels of criminal activity and violence. We must find a path of genuine reform, even transformation, that fosters safer, more peaceful, and more resilient communities.

In this volume, available to be downloaded as a full PDF here or to be read online as individual chapters below, experts from a broad spectrum of domains and policy perspectives offer policymakers with research-grounded analysis and recommendations to support sustained, bi-partisan reforms to move the criminal justice system toward a more humane and effective footing.

Read the introduction

Police reform

Authors: Rashawn Ray , Clark Neily

The deaths of unarmed Black Americans, including George Floyd, Elijah McClain, Breonna Taylor, and many others, at the hands of police are leading to calls for sweeping police reform . In Chapter 1, our experts lay out a series of sensible police reform ideas shared across the political spectrum, including reforming qualified immunity, addressing officer wellness, and changing the culture of “us versus them” policing.

Read Chapter 1

- Download a PDF of this chapter.

Reimagining pretrial and sentencing

Authors: Pamela K. Lattimore , Cassia Spohn , Matthew DeMichele

America’s incarceration rate is the highest in the world, a condition rooted in policies and practices that result in jail for millions of individuals charged with but not convicted of a crime and lengthy jail or prison sentences for those who are convicted. In Chapter 2, our experts argue that there is an urgent need for a pretrial justice and sentencing strategy that will reduce crime and victimization, ameliorate unwarranted racial and income disparities, and reclaim human capital lost to incarceration.

Read Chapter 2

Changing prisons to help people change

Authors: Christy Visher , John Eason

Most imprisoned people will be released into society, but are they prepared to rejoin their communities and avoid a return to prison? In Chapter 3, our experts note that the lack of vocational training, education, and reentry programs makes reintegration difficult for the formerly imprisoned. They propose programming such as cognitive behavioral therapy, education, and personal development to help ease this transition.

Read Chapter 3

Reconsidering police in schools

Authors: Ryan King , Marc Schindler

Although rates of juvenile crime and arrests have declined in recent decades, the rash of school shootings since Columbine in 1999 has catalyzed federal funding for more police in schools. But these school police officers have been linked with increased arrests for non-criminal, youthful behavior. In Chapter 4, our experts offer ways to reimagine public safety in schools and change the dominant but increasingly unpopular law enforcement paradigm.

Read Chapter 4

Fostering desistance

Authors: Shawn D. Bushway , Christopher Uggen

What makes people returning to civilian life from incarceration desist from committing crime? In Chapter 5, our experts review the literature on “desistance,” the study of why and how people stop committing crimes. They note that many people who become involved in the criminal justice system had never fully entered a pro-social adult life to begin with, and so programs designed to foster their “re-entry” into society should focus on fostering adult development .

Read Chapter 5

Training and employment for correctional populations

Authors: Grant Duwe , Makada Henry-Nickie

People involved in the criminal justice system tend to be undereducated and underemployed compared to the general population, and post-release employment rates eventually return to pre-prison levels. In Chapter 6, our experts call the employability of returning citizens a “moral imperative,” and so recommend policies designed to increase educational attainment and employment training for incarcerated individuals.

Read Chapter 6

Prisoner reentry

Authors: Annelies Goger , David J. Harding , Howard Henderson

Over 640,000 people return to their communities from prison each year, but more than half of the formerly incarcerated do not find stable employment in their first year of return, and three-quarters are rearrested within three years. In Chapter 7, our experts offer a range of policies to improve reentry outcomes and increase racial equity in the criminal justice system.

Read Chapter 7

Authors: Rashawn Ray , Brent Orrell

As we prepare to exit pandemic conditions, it is a crucial time to address criminal justice reform in America. In the Conclusion to “A better path forward for criminal justice,” our experts recommend a strategic pause to gather data that will help us understand why criminal activity has gone up in recent months and inform both immediate responses as well as longer-term initiatives.

Read the conclusion

The editors would like to thank Samantha Elizondo for her work on the project, particularly with chapter summaries and editing of the report.

Support for this publication was generously provided by the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation. The views expressed in this report are those of its authors and do not represent the views of the Foundation, their officers, or employees.

The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusion and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its authors, and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars.

The American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research is a nonpartisan, nonprofit 501(c)(3) educational organization. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors. AEI does not take institutional positions on any issues.

Governance Studies

Sarah Reber, Gabriela Goodman, Rina Nagashima

November 7, 2023

Katharine Meyer, Adrianna Pita

June 30, 2023

Harry Holzer

June 29, 2023

3 simple ways to instantly improve your report writing

Tactics keep you alive, but report writing keeps you out of trouble.

There are three techniques you can do to instantly improve your police report writing, avoid case dismissal and protect yourself as an officer.

Photo/PoliceOne

This article is part of a series, Report Writing for a New Generation: Merging Technology with Traditional Techniques , which covers general police report writing skills along with plain English instruction, professional and technical writing best practices, and how technology is changing the way officers write.

The series is exclusive content for Police1 members. Not a member? Register here. It is free and easy!

Last year, I attended a weeklong regional technical training course tailored for first-line supervisors. The course covered best practices in managing large-scale chaotic scenes and conducting after-action reviews . After the training, I spoke to one of the instructors, a retired LEO, for more information on after-action reports. I was quickly met with an interesting and borderline discouraging comment: “Officer’s don’t care about reports; they care about tactics. Focus on tactics, and someone else will do the after-action report.”

“Officers don’t care about reports; they care about tactics.” Was that statement true?

I returned to work and decided to review my internal training records. I had plenty of advanced defensive tactics, active shooter and mass casualty response training but to my surprise, I had nothing related to law enforcement report writing . My external training records were just as slim – lots of courses on teaching, fraud investigations and accounting, but very few on how to write a better police report.

My colleagues were in the same boat: lots of tactics training with little to no police report writing training.

Tactics keep you alive, but a well-written police report keeps you out of trouble; however, report writing is something most agencies dismiss as an important officer survival skill.

Luckily, there are three techniques you can do to instantly improve your police report writing, avoid case dismissal and protect yourself as an officer. And the best part is that you do not need formal training and it only takes minutes a day.

1. Don’t write when you are tired

OK, I hear you: “I am always tired, so how can I write when I am not tired?”

Police exhaustion is such a major concern for police agencies that Police1 dedicated an entire podcast segment to fighting fatal fatigue in law enforcement . Unfortunately, being tired is part of the career. So, let me rephrase the heading: Write when you are less tired .

Writing while alert is necessary because the police report-writing process is mentally taxing. An officer starts by reviewing their mental and physical notes, then progresses through a series of prewriting, writing, responding, revising, editing and publishing (sending the report to a supervisor for review). When an officer is mentally exhausted or physically tired, this will lead to mistakes. Note I didn’t say, “this may lead to mistakes.” Being tired will lead to mistakes.

Most police agencies make bad report writing worse with write-it-before-you-go-home policies. After a 10+ hour shift, the last thing any officer wants to do is sit down and write a shoplifting or found property report. Of course, some investigations should be written before going home because of due process rights, immediate follow-up, or investigators are still on scene. But most police reports can be held until the officer returns the next day.

Having a small break between shifts gives an officer’s mind time to process the information and organize their thoughts subconsciously. When an officer is alert and their thoughts are organized, they will be prepared to write accurate accounts of what happened.

Time helps the mind process information.

Even if your agency requires same-day reports, there is a little trick to help mitigate mistakes. In these cases, try to write your report directly after the incident but wait two to three hours to proofread it. You will be surprised at how much extra information your brain will naturally find during that short break. If you think of any additional information after you submitted your police report, just write a supplemental report when you get in the next day.

2. Use spelling and grammar checkers

Over the past five years, I have read thousands of police reports from around the United States. Many of these reports are packed full of simple grammar and spelling mistakes that a word processor’s spellcheck would have caught.

I know that many of these agencies, including mine, use Microsoft Word’s spellcheck feature. So why do we continue making basic spelling and grammar mistakes? I decided to do some digging, and each time I read an exceptionally bad report, I called the agency, not to complain or call them out, but to ask questions. I found that most poorly written reports from 2010 to the present day share three traits:

- The officer wrote the report directly in the agency’s records management system (RMS);

- The officer did not configure spellcheck; or,

- The officer wrote in UPPERCASE.

RMS spell checkers are improving, especially in the new AI integrated RMS 3.0 versions. But as of right now, even the most basic version of Microsoft’s Word spellcheck outperforms any RMS spellchecker. Try to write your report in a word processor first, then copy and paste it into your agency’s RMS.

(If you want to learn more about how to set up spellcheck correctly, read the next article in this series, How to set up spellcheck to proofread your police report , available for Police1 members only.)

Writing in uppercase is an unnecessary annoyance. If you are writing in uppercase, please stop. Your boss, your prosecutor and all the agencies reading your report will thank you. Writing in uppercase is an old technique used to correct bad penmanship, but since we are writing in a word processor, all uppercase writing is not needed. Spellcheck also must be configured correctly for it to catch mistakes in uppercase.

3. Read your report aloud

The best advice I ever received in school is to read reports aloud. Even if your spoken grammar is not perfect, reading your report aloud will help you catch many small grammar and sentence mistakes not caught by spellcheck. If a sentence sounds weird, change it. Nine times out of 10, you will be correct.

Just remember, you don’t need to read LOUD, just aloud. Be courteous of those around you by just whispering.

Good report-writing skills protect officers

You don’t have to become a novelist or a professional writer to be a good writer. But you should put a little effort into becoming a better writer than where you are now. These three techniques are simple and easy to apply and more importantly, they work. Good police report-writing skills will not only protect you on the street from overzealous anti-police lawyers but also in the courtroom, internal affairs investigations and school.

Bonus content: How to train your ear to catch writing mistakes

If you spend time training your ear for writing, you will catch even more mistakes. An excellent way to train your ear for good sentence structure and grammar is to read good literature aloud. I recommend “ The Stories of Vladimir Nabokov ” not because it is an enjoyable read but because his sentences are as close to perfect as they come, and he really focuses on the sound of a sentence. Read one page a day aloud. Ignore the content, just listen to the words and sounds. Your mind will automatically notice sentence parallelism, assonance, rhythm and alliteration – all critical features of a good sentence. When you read your police report aloud, your ear will suddenly pick up the smaller mistakes in your writing.

Next: How to set up spellcheck to proofread your police report

A step-by-step guide to configuring Microsoft’s spelling and grammar checker

- Our Mission

- Team Members

- TC Magazine

- Advisory Board

- 100K for 10

- Criminology at GMU

- Join Our Mailing List

- News & Announcements

- CEBCP in the News

- Calendar of Events

- Achievement Award

- Policing Hall of Fame

- News and Announcements

- Translational Criminology Magazine

- Symposia and Briefings

- Evidence-Based Policing

- Crime and Place

- Systematic Reviews

- Criminal Justice Policy

- CEBCP-W/B HIDTA

- Outreach, Symposia, & Briefings

- Translational Criminology

- CEBCP Video Library

- Criminology & Public Policy

- Technology Web Portal

- COVID-19 Projects

- Crime & Place Bibliography

- Important Links

Evidence-Based Policing Matrix

Home › Evidence-Based Policing › The Matrix › Using the Matrix

- Matrix Home

- Individuals

- Micro-Places

- “Neighborhood”

- Jurisdiction

- Nation/State

- Using the Matrix

- Inclusion Criteria/Methods Key

- Realms of Effectiveness

- Matrix Divided by Rigor

Below you will find tools and ideas on using the Evidence-Based Policing Matrix. Please use the quick links below to find out more information. Looking for information on the Matrix axes and coding? Click here for the Matrix Key .

- Articles on the use of the Matrix

- The Matrix Demonstration Projects

- Video Training

- Other Ideas – for Police Agencies

- Other Ideas – for Researchers and Funding Agencies

Articles and Books on Using Evidence

- Lum, C. and Koper, C.S. (2017). Evidence-Based Policing: Translating Research into Practice (Oxford University Press).

- Lum, C. (2009). Translating Police Research into Practice . Ideas in American Policing Series. Washington, DC: Police Foundation.

- Lum, C., Koper, C., and Telep, C. (2011). The Evidence-Based Policing Matrix. Journal of Experimental Criminology 7(1): 3-26.

- Lum, C., Telep, C., Koper, C., and Grieco, J. (2012). Receptivity to Research in Policing. Justice Research and Policy 14(1).

- Lum, Cynthia and Christopher Koper. (forthcoming). Evidence-Based Policing. In The Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice (Gerben Bruinsma and David Weisburd, Editors). Springer-Verlag.

The Matrix Demonstration Project

The Matrix Demonstration Project provides examples of institutionalizing principles from the Matrix and also from police research more generally into practice. Agencies can download ideas, forms, guidelines, and videos from the MDP to develop their own efforts.

Video Training on Evidence-Based Policing and the Matrix

- Cynthia Lum – “The Evidence-Based Policing Matrix”

- Howard Veigas – “Assessing the Evidence-Base of Strategies and Tactics of Uniformed Patrol in Derbyshire Police”

- Evidence-Based Policing: Translating Research into Practice . Webinar by Cynthia Lum held on November 8, 2011

- Evidence-Based Policing Workshop held at George Mason August 13, 2012; includes presentations about the Matrix Demonstration Project.

Other Ideas – For Police Agencies

1. Officers in Patrol or Street-Level Units:

The Matrix generally indicates that patrol can improve its crime control effectiveness by balancing their reactive, rapid-response 911 approach, with proactivity at crime “hot spots” or problem places in between calls for service. Roughly between 40-60% of an officer’s time, even in high crime cities, is not committed to answering calls for service. The Matrix (and many others, including the POP Center, the COPS Office, or CrimeSolutions.gov) provides examples and ideas of directed patrol, problem-solving, and community-building ideas for patrol officers to consider. Further, the authors recommend applying the Koper Curve Principle in crime hot spots; that officers and units randomly hit hot spots and stay for limited amounts of time to maximize their deterrent effect.

Some general patrol deterrent strategies at places in the past have included crackdowns, proactive traffic stops, and arrest policies for disorder and quality of life crimes. More recently, technologies have helped facilitate general deterrent patrol in hot spots, including license plate readers and CCTVs. And, a number of problem-solving activities which extend partnerships to non-police and other community entities have also been developed. Officers should be cognizant, and sensitive (and consistently trained to be so) to concerns that some crackdown approaches can also result in racial profiling, excessive use of force, reductions of police legitimacy, and overcrowded jails. Educating and alerting communities about these strategies and working to professionally and constitutionally deliver proactive policing at places is an important part of implementing police tactics.

The Matrix also recommends problem solving and multi-agency approaches at smaller places. This can include civil remedies (nuisance abatement) such as those shown in Mazerolle’s studies (e.g. Mazerolle, Price, & Roehl, 2000) problem-oriented policing approaches as seen in the micro place slab of the Matrix, “Project Safe Neighborhood” approaches and other more specific community-level tactics. Another promising approach may be a “pulling levers” approach with regard to gang violence at places. Officers are encouraged to examine specific abstracts/summaries of the studies within these realms that have shown promise (the black dots) for further ideas.

2. Strategizing about Tactical Operations and Patrol Deployment:

These suggestions are similar to the uniformed officer discussion above, and should be read in addition to #1. Clusters of effective studies (indicated by the black dotes) indicate realms of effectiveness within the Matrix. Rather than try to apply a single study to an agency’s more specific concerns, these realms provide clues as to which three intersecting dimensions have clusters of effective studies within them.

For example, where the dimensions “micro place”, “focused” and “proactive” or “highly proactive” intersect, there are a number of studies which indicate interventions like these can be fruitful in reducing crime. Agencies developing crime prevention measures need not replicate a study’s specific intervention. Rather, the Matrix shows that if agencies develop patrol interventions that are aimed at micro-places, focused/tailored, and proactive, then they may be able to improve their ability to reduce crime. Agencies that undertake reactive and individual-based approaches may not be as productive. Thus, a strategy involving nuisance abatement of a house which is used to distribute drugs is more likely to be effective in reducing drug crimes than building a case against a street dealer using buy and bust or other traditional techniques.

The realms of effectiveness in the Matrix are a research translation tool for strategic development; rather than search for a study that is specifically relevant to a jurisdiction, the clustering of effective studies helps create generalizations (intersection dimensions) which can provide enough flexibility for jurisdiction-specific approaches, but at the same time are informed by evidence. Devising an overall strategy for patrol, specialized or even investigative units that is “housed” in a realm of effectiveness will prove more fruitful than a “random” patrol strategy at beats that is built from goals that are purely procedures-based.

3. Assessment and accountability at the command and agency level:

The Matrix can be interacted with at command meetings such as COMPSTAT or other managerial practices to determine if the most effective approaches are being used for a particular crime problem and also to foster evidence-based leadership in general deployment. For example, during a COMPSTAT meeting, the focus could be shifted from reciting monthly statistics and vague assertions of tactics to real-time mapping of tactical suggestions and existing strategies directly into the Matrix, discussing what alterations in tactics and strategies can push approaches towards more effective realms.

The Matrix could be also more broadly used to self-assess the agency’s overall tactical portfolio. Mapping an agency’s existing patrol interventions and tactics into the Matrix can provide a comparison between the tendencies of an agency’s patrol deployment and what is known from research.

4. Assessment and accountability at the first line-supervision and district levels:

Such assessments of tactical and strategic portfolios could also be carried out at the district, sector, squad, or individual level. In the U.S., first line supervisors (sergeants) have had more passive supervisory duties, such as approving reports, applying general orders to infractions, violations, or special concerns, handling administrative duties regarding personnel, or responding with officers to serious calls for service. Empowering first line supervisors with responsibility in developing their own tactics and strategies for their squads can increase the motivation and effectiveness of this rank, moving towards a more active model of first line supervision. The Matrix provides a quick visual guide for first line and district supervisors to determine whether their choices most likely will lead to positive results. It can also influence the use of crime analysis at the patrol and first-line supervisory level, given that most effective tactics require basic crime analysis. This is an essential step forward toward not only integrating crime analysis at the street-level, but also increasing the proactive tendencies of an agency.

5. Early training and socialization of officers:

Along these same lines, officers should be trained during the academy and in-service courses in the fundamental concepts of how to increase their effectiveness and legitimacy by exposing them to tactics (or more generally, realms of effectiveness) backed by scientific evidence, not by anecdotes, stories, or other ad hoc experiences. A basic skill of the entering officer should be the ability to identify which tactics have been shown to be effective in reducing crime and which have not, just as he or she also learns the procedures by which to make an arrest. Further, tactics in the most effective realms of the Matrix emphasize other approaches to policing than just reacting to 911 calls or cases on an individual basis. Transitioning police culture and mentality away from one that is reactive to one that is proactive is a fundamental need for early training as well as in-service education. The Matrix Demonstration Project web page has examples of how this might occur.

6. Promotions and advancement:

Candidates, when tested on crime prevention scenarios (which is often common at the first and second-level supervisor ranks), could be assessed on their ability to develop solutions that fall within effective realms. Or, the tactical resumes/portfolios of those in line for promotion could be mapped into the Matrix to discern whether contenders generally use approaches that are more evidence-based or if they tend to rely on methods that are more traditional.

7. Crime analysis units:

Crime analysts are the “applied criminologists” of agencies. They have the opportunity not only to assess the crime control and preventative effects of police tactics, but also to use the most believable scientific methods in their evaluations. The Matrix, especially the tab showing the Matrix “divided by rigor” provides ideas on evaluating new strategies using experimental methods, and ideas on what other analysts and researchers are doing to assess the effectiveness of tactics.

Further, the authors recommend agencies increase their analysis units if they take evidence-based approaches. The most effective realms of the Matrix are those that fall in place-based, proactive areas, requiring constant computerized crime mapping support for operational units, as well as crime analysis to discover crime trends for proactive deployment or predictive policing.

Other Ideas – For Research and Funding Agencies

1. Supplying methodologically rigorous research to meet the demand for research:

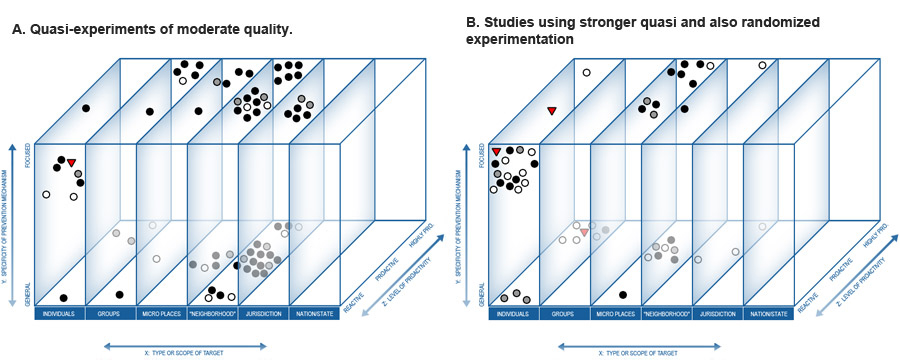

The Matrix not only shows researchers and funding agencies areas of police intervention that have not been researched but also areas that have not been researched well. To make this point, the Matrix is split below into two groups of studies. Figure A represents 71 studies (or 61% of the entire Matrix) that used moderately rigorous designs, while Figure B shows the 46 studies (39%) that used stronger methods. This separation shows that there are much fewer evaluations available of high quality. Thus, while we know some areas of the Matrix are “promising”, more is needed on being more convinced of this promise.

Comparisons of Studies in the Matrix of Moderate and Strong Methods:

A few other findings stand out in this division – higher quality studies that show positive effects are most consistently found in the proactive, micro place-based region. Figure B also tells us, with high certainty, that individual strategies are much less promising, and in some cases, harmful. Finally, notice that neighborhood and group-based studies almost completely disappear when only looking at the highest quality studies. If police are interested in using such strategies, then better information must be generated at these units of analysis. For example, the policing of gangs is a high priority issue for police, yet very little strong evaluation research exists in the “groups” slab of the Matrix to meet this demand for evaluation.

2. A common language for the research-practitioner relationship:

The Matrix also can be used as a “common ground” for conversations between researchers, police practitioners, and funding agencies when collaborating to evaluate, study, and ultimately reduce crime. In many ways, the Matrix builds on officer experience by connecting to officers with familiar vernacular. For example, a police agency may be interested in testing certain types of interventions such as crackdowns on gangs or illegal gun carrying. The researcher, however, may be interested in improving the quantity of high quality evaluations in the proactive place-based regions of the Matrix or conducting more rigorous experiments of neighborhood-level policing. In this scenario, the Matrix could be used to elicit discussion and negotiation between the researcher and the police agency in a way that keeps the agency grounded in evidence-based regions but that does not divorce the police researcher from the real needs of the police agency. Solutions might thus include a quasi-experimental study testing pulling levers approaches in multiple gang territories, or perhaps a randomized repeated measures study of crackdowns on gun carrying in high-risk patrol beats.

3. Evidence-based funding and “Smart Policing” efforts:

Funding agencies, such as NIJ, the BJA, or the COPS Office, can use tools like the Matrix to fund research and interventions in strategic ways that facilitate evidence-based policing, thus placing these agencies in more of a leadership role regarding improving the use of evidence in law enforcement. As shown in the figure below, such agencies might give priority, for example, to “low risk” funding that would support more research in understanding the nature of interventions that work, or in testing replications in diverse areas (for example – do place-based approaches work – and how – in rural or suburban areas as they do in urban areas?)

“Medium risk” areas of the Matrix point to intersection dimensions in which the research may be less rigorous, or findings might be more ambiguous. More rigorous research in these areas may be needed, or research that examines what aspects of these interventions lend to crime prevention.

“High risk” programs and research would fall within domains of the Matrix that have shown little promise or even backfire effects. Here, researchers and funding agencies might show constraint in funding within these areas. Or, if funding is necessary, focus on better understanding when such approaches might be used effectively.

Finally, there are areas of the Matrix that reflect high demand for research, but where the supply of research is low. Evaluations of gang and co-offending interventions, or jurisdiction-level policies may be good targets for innovative or exploratory research and research funding.

We use cookies on our website to support technical features that enhance your user experience, and to help us improve our website. By continuing to use this website, you accept our privacy policy .

- Student Login

- No-Cost Professional Certificates

- Call Us: 888-549-6755

- 888-559-6763

- Search site Search our site Search Now Close

- Request Info

Skip to Content (Press Enter)

What Should I Know Before Studying Criminal Justice? 10 Things to Keep in Mind

By Hope Rothenberg on 05/16/2024

If you're interested in studying criminal justice, odds are pretty high that you care about making a positive impact on your community. As laws evolve and reform takes hold, there's no question that it's an interesting—and an important—time to learn more about the criminal justice system we all live in.

“All of the justice careers are so interesting,” says Eileen Carlin, Professor of Criminal Justice at Rasmussen University. “No matter what you choose to go into, whether you wind up as a victim advocate or a parole officer, you’re going to love it.”

Whether you’re looking to explore anything from family services to security management, a criminal justice degree could be a perfect way to start. But what can you expect from a criminal justice degree program?

Here are 10 things to know before studying criminal justice.

1. It's a bigger field than you may realize

The justice system spans from crime prevention to legal careers to corrections and rehabilitation. A lawyer, a private investigator, a crime victim advocate , a social work assistant—these can all fall under the realm of criminal justice.

Depending on the role, you may need additional education beyond an associate’s degree or bachelor’s degree in criminal justice to pursue some of the above career paths. It is important to check the education and work experience requirements for any role you’re interested in.

“There’s so much you can do with it,” Carlin says. “I’m just so proud of our students. A lot of them have gone on to law school—and that’s not easy. They’re just amazing.”

If you’re interested in that path, check the bachelor’s degree major, Law School Admission Test ® (LSAT ® ) score, and GPA required for any law schools you might apply to.

Carlin says many students go on to work as parole and corrections officers, police officers and 911 dispatchers. 1 “It’s the best part of my job,” Carlin says. “Students will stay in touch and ask me for letters of recommendation, and I see them get into these professions so quickly.”

Graduates with an associate's degree may consider roles in investigation and security services, probation and parole and individual and family services. Possible career paths for graduates with a bachelor’s degree include becoming a crime victim advocate, security manager, corporate security supervisor, court clerk or a security officer.

2. Most justice careers involve a ton of writing

This is the main thing Carlin wishes all her students knew before studying criminal justice—pretty much every role is writing-heavy.

“Court clerks are writing constantly; victim advocates need to record everything that happens when they meet with a victim; Judges, defense attorneys and juries all rely on police reports…If there’s even one mistake, one word spelled wrong, you can jeopardize a case,” Carlin says.

Because of this need for precision, justice studies programs really need to include lots of training in writing. Carlin explains that sometimes students come into the program expecting a law enforcement career to be totally hands-on.

“You’re used to watching cop shows where they spend maybe ten minutes responding to a call, then it sort of cuts away,” Carlin laughs. “What they don’t show you is because of that call, those officers will spend the next 3-4 hours writing a report. The secretary doesn’t do that. We do it.”

But for Carlin, the writing is actually pretty soothing. “I don’t mind writing reports, especially if you can get comfortable. But sometimes you’re sitting in the patrol car, sort of sideways, typing on a computer while wearing 25 pounds of gear, which does feel more like a chore.”

3. Some programs are made for working adults

Going to school (or back to school) is a big commitment. But what many prospective students don't realize is that you can work on it without putting your life on hold.

Criminal justice degree programs like the ones offered at Rasmussen University are online, and they're specifically designed to fit into the schedule of a working adult’s life. The format of the courses can enable you to schedule schoolwork around your other responsibilities as you complete your degree.

4. There are multiple criminal justice degree paths

When it comes to choosing a criminal justice degree program, you'll likely come across two main pathways: an associate's degree in criminal justice or a bachelor's degree in criminal justice . These are two separate programs that differ in a few ways. Here's a brief breakdown of each, using the Rasmussen University programs as an example.

Criminal Justice Associate's Degree

Created to help you earn your degree online and prepare to protect and serve your community, the associate's degree program requires about half as many credits as the bachelor's degree program, and it can be completed in a few as 18 months. 1

Designed to help students understand the history and development of the criminal justice system and its effect on society, an associate's degree in criminal justice could lead to roles in investigation and security services, probation and parole and individual and family services. For more on that, check out the Criminal Justice Associate’s Degree program page.

Criminal Justice Bachelor's Degree

A bachelor's degree in criminal justice requires about twice as many credits as an associate's degree, and subsequently takes roughly twice as long to complete. That said, you can still complete the program in as few as 36 months with no previous experience or credits. 2

Since it’s a higher degree level, completing a criminal justice major in a bachelor's degree program could lead to additional roles and opportunities in the field. Get more details at the Criminal Justice Bachelor’s Degree page.

5. You’ll be exposed to diverse coursework

In any comprehensive criminal justice program, you’ll learn through live interactive sessions with faculty and peers, and engage in real-world projects like analyzing real interrogation videos.

From studying human behavior to diving deep into the law, criminal justice coursework covers a wide range of topics and learning formats. Some example courses? Cultural Diversity and Justice, Values-Based Leadership in Criminal Justice, and Mental Health and Substance Abuse in Criminal Justice. For detailed descriptions, take a look at the Rasmussen University 2023 - 2024 course catalog .

6. Your instructors might be intimidating

Once you head down a criminal justice degree pathway, you may be surprised to find you'll be taught by real-life criminal justice professionals. The curriculum for the Rasmussen University criminal justice programs is developed and refreshed with the assistance of industry subject matter experts—which is to say, experts who have lots of experience in different criminal justice careers.

These instructors bring years of experience in law enforcement, narcotics, combating human trafficking and corrections to the classroom—and they'll be equally committed to your success as a criminal justice student. Rather than be intimidated, take it as an opportunity to learn as much as possible from those with experience in the field, and form lasting connections you can carry through your career.

7. You won't just be writing papers and taking tests

In a program like Rasmussen’s, criminal justice students practice career-ready criminal justice skills through realistic scenarios that include police ride-alongs, interrogation analysis videos and drafting search warrants.

Yes, there’s still a lot of writing to do—but Rasmussen’s program was designed to help students understand the day-to-day realities of each career area they are working toward.

8. You'll gain a variety of skill sets

While it may seem like a rigid or straightforward career path, a criminal justice program can teach you a range of valuable interpersonal and transferable skills that can make you a more effective worker across a variety of roles. By pursuing a criminal justice degree, you can expect to learn and accomplish the following.

- Strong foundational knowledge. Your coursework is ultimately designed to help you understand the history and development of the criminal justice system and its impact on society. At the end of it all, you'll be able to truly understand what criminal law is and the legal procedures required to enforce it.

- Serving with integrity. You'll develop an understanding of the relationships—and tensions—between the criminal justice system and the diverse populations it serves. This awareness will help you act ethically, responsibly and with the right amount of personal character.

- Quick critical thinking. You'll be equipped to apply critical-thinking skills and appropriately react to fast-paced, constantly changing issues in criminal justice—including everything from security to juvenile justice to domestic violence.

- Compassionate communication. Whether you’re helping a coworker complete paperwork or speaking with crime victims, strong communication skills are key to a successful criminal justice career, and you’ll have every opportunity to improve yours.

As you make your way from the classroom to a career in the field, you'll find yourself relying on the skills listed above and many more—and sometimes the most critical ones will be the ones you least expect.

9. Continuing education is really encouraged, and sometimes reimbursed

“While I was a police officer, I knew I’d retire, and I’d still be fairly young, so I got my master's degree,” says Carlin. “My department paid for it. It’s very common, almost every department gives some form of tuition reimbursement. It helps to have that educational background if you want promotion.”

The level of education encouraged often depends on the specific department and state. In some places, the more formal education you have, the more options you’ll have.

“In New Jersey for example, you get hired, and then the department sends you to the police academy,” continues Carlin. “Education helps there. You’re more likely to get called back. But in Minnesota, you put yourself through the skills academy after graduating a program.”

While the standards are different everywhere, Carlin says a foundational associate's or bachelor’s level criminal justice degree, students can pursue work throughout the justice and corrections systems—leading to a variety of criminal justice career opportunities to explore.

10. The criminal justice system isn't perfect

Of course, you already know this. And it's a big part of why you're motivated to study the current criminal justice system and make a positive difference in your community. Whether you opt for an associate's degree or a bachelor's degree, you're embarking on a meaningful path—and one that can lead you to a whole range of places.

So you might be wondering—how do these programs work? How much does a criminal justice program cost? Get those answers and read more at Rasmussen’s online Criminal Justice Degree program page.

LSAT ® is a registered trademark of LAW SCHOOL ADMISSION COUNCIL, INC. Law School Admission Test ® is a registered trademark of Law School Admission Council, Inc. 1 Rasmussen University’s Criminal Justice Associate’s and Criminal Justice Bachelor degree programs are not designed to meet the educational requirements for professional licensure or certification in any state. In Minnesota, the Criminal Justice Associate’s degree program does not meet the standards established by the Minnesota Peace Officer Standards and Training Board for persons who seek employment as a peace officer. For further information on professional licensing requirements, please contact the appropriate board or agency in your state of residence. Additional education, training, experience, and/or other eligibility criteria may apply. 2 Completion time is dependent on transfer credits accepted and the number of courses completed each term.

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Pinterest

- Share on LinkedIn

Request More Information

Talk with an admissions advisor today. Fill out the form to receive information about:

- Program Details and Applying for Classes

- Financial Aid and FAFSA (for those who qualify)

- Customized Support Services

- Detailed Program Plan

There are some errors in the form. Please correct the errors and submit again.

Please enter your first name.

Please enter your last name.

There is an error in email. Make sure your answer has:

- An "@" symbol

- A suffix such as ".com", ".edu", etc.

There is an error in phone number. Make sure your answer has:

- 10 digits with no dashes or spaces

- No country code (e.g. "1" for USA)

There is an error in ZIP code. Make sure your answer has only 5 digits.

Please choose a School of study.

Please choose a program.

Please choose a degree.

The program you have selected is not available in your ZIP code. Please select another program or contact an Admissions Advisor (877.530.9600) for help.

The program you have selected requires a nursing license. Please select another program or contact an Admissions Advisor (877.530.9600) for help.

Rasmussen University is not enrolling students in your state at this time.

By selecting "Submit," I authorize Rasmussen University to contact me by email, phone or text message at the number provided. There is no obligation to enroll. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

About the author

Hope Rothenberg

Hope Rothenberg is a creative copywriter with agency, in-house, and freelance experience. She's written about everything from area rugs to artificial intelligence, and a ton in between.

Posted in General Justice Studies

- justice studies education

- justice studies careers

- justice studies trends

- justice studies

- criminal justice

Related Content

Noelle Hartt | 04.16.2024

Brianna Flavin | 09.19.2022

Patrick Flavin | 07.18.2022

Will Erstad | 03.21.2022

This piece of ad content was created by Rasmussen University to support its educational programs. Rasmussen University may not prepare students for all positions featured within this content. Please visit www.rasmussen.edu/degrees for a list of programs offered. External links provided on rasmussen.edu are for reference only. Rasmussen University does not guarantee, approve, control, or specifically endorse the information or products available on websites linked to, and is not endorsed by website owners, authors and/or organizations referenced. Rasmussen University is accredited by the Higher Learning Commission, an institutional accreditation agency recognized by the U.S. Department of Education.

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

United States Drug Enforcement Administration

- Get Updates

- Submit A Tip

DEA Releases 2024 National Drug Threat Assessment

WASHINGTON – Today, DEA Administrator Anne Milgram announced the release of the 2024 National Drug Threat Assessment (NDTA), DEA’s comprehensive strategic assessment of illicit drug threats and trafficking trends endangering the United States.

For more than a decade, DEA’s NDTA has been a trusted resource for law enforcement agencies, policy makers, and prevention and treatment specialists and has been integral in informing policies and laws. It also serves as a critical tool to inform and educate the public.

DEA’s top priority is reducing the supply of deadly drugs in our country and defeating the two cartels responsible for the vast majority of drug trafficking in the United States. The drug poisoning crisis remains a public safety, public health, and national security issue, which requires a new approach.

“The shift from plant-based drugs, like heroin and cocaine, to synthetic, chemical-based drugs, like fentanyl and methamphetamine, has resulted in the most dangerous and deadly drug crisis the United States has ever faced,” said DEA Administrator Anne Milgram. “At the heart of the synthetic drug crisis are the Sinaloa and Jalisco cartels and their associates, who DEA is tracking world-wide. The suppliers, manufacturers, distributors, and money launderers all play a role in the web of deliberate and calculated treachery orchestrated by these cartels. DEA will continue to use all available resources to target these networks and save American lives.”

Drug-related deaths claimed 107,941 American lives in 2022, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Fentanyl and other synthetic opioids are responsible for approximately 70% of lives lost, while methamphetamine and other synthetic stimulants are responsible for approximately 30% of deaths.

Fentanyl is the nation’s greatest and most urgent drug threat. Two milligrams (mg) of fentanyl is considered a potentially fatal dose. Pills tested in DEA laboratories average 2.4 mg of fentanyl, but have ranged from 0.2 mg to as high as 9 mg. The advent of fentanyl mixtures to include other synthetic opioids, such as nitazenes, or the veterinary sedative xylazine have increased the harms associated with fentanyl. Seizures of fentanyl, in both powder and pill form, are at record levels. Over the past two years seizures of fentanyl powder nearly doubled. DEA seized 13,176 kilograms (29,048 pounds) in 2023. Meanwhile, the more than 79 million fentanyl pills seized by DEA in 2023 is almost triple what was seized in 2021. Last year, 30% of the fentanyl powder seized by DEA contained xylazine. That is up from 25% in 2022.

Social media platforms and encrypted apps extend the cartels’ reach into every community in the United States and across nearly 50 countries worldwide. Drug traffickers and their associates use technology to advertise and sell their products, collect payment, recruit and train couriers, and deliver drugs to customers without having to meet face-to-face. This new age of digital drug dealing has pushed the peddling of drugs off the streets of America and into our pockets and purses.

The cartels have built mutually profitable partnerships with China-based precursor chemical companies to obtain the necessary ingredients to manufacturer synthetic drugs. They also work in partnership with Chinese money laundering organizations to launder drug proceeds and are increasingly using cryptocurrency.

Nearly all the methamphetamines sold in the United States today is manufactured in Mexico, and it is purer and more potent than in years past. The shift to Mexican-manufactured methamphetamine is evidenced by the dramatic decline in domestic clandestine lab seizures. In 2023, DEA’s El Paso Intelligence Center (EPIC) documented 60 domestic methamphetamine clandestine lab seizures, which is a stark comparison to 2004 when 23,700 clandestine methamphetamine labs were seized in the United States.

DEA’s NDTA gathers information from many data sources, such as drug investigations and seizures, drug purity, laboratory analysis, and information on transnational and domestic criminal groups.

It is available DEA.gov to view or download.

Simpson Thacher’s Top Partners to Make $20 Million This Year (1)

By Roy Strom

Top partners at Simpson Thacher & Bartlett are expected to earn more than $20 million this year after the Wall Street law firm widened the spread between its highest and lowest-paid equity partners.

The move, which Simpson Thacher confirmed on Thursday, comes amid signs that the competition to hire and retain partners at the top of the market has never been fiercer . Other Wall Street firms have introduced compensation changes to offer higher pay to some new hires or their highest-performing partners.

“We intentionally made the decision to adjust our compensation structure to attract and retain the best talent across our global platform,” Alden Millard, the firm’s chairman, said in a statement. “Our partners have embraced the change and are excited about the Firm’s continued growth and success.”

VIDEO: Big Law’s Big Paychecks: Partner Compensation, Explained

The spread between Simpson Thacher’s highest and lowest paid partners is now 9-to-1, the firm confirmed. Partner compensation spreads have been widening across the industry.

Davis Polk & Wardwell this month said it would adjust its compensation system to “lean into” the lateral partner market. The decision marks a sharp change for the Manhattan firm, which historically has made relatively few outside hires.

Sullivan & Cromwell, another high-end firm that has not been among the most historically active in the lateral market, this week made a splash hire of two Silicon Valley dealmakers from Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom.

Those moves came after Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison reportedly adjusted its compensation structure amid a bevvy of lateral hires, notably poaching top partners in London from Kirkland & Ellis.

The Simpson Thacher compensation change was first reported by The American Lawyer.

To contact the reporter on this story: Roy Strom in Chicago at [email protected]

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Chris Opfer at [email protected] ; John Hughes at [email protected] ; Alessandra Rafferty at [email protected]

Learn more about Bloomberg Law or Log In to keep reading:

Learn about bloomberg law.

AI-powered legal analytics, workflow tools and premium legal & business news.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools.

Michael Cohen testifies on Stormy Daniels payment in Trump trial

- Cohen says Trump promised to pay him back for Stormy Daniels money

- Cohen said he worked on behalf of the Trump campaign

- Cohen talks about getting salacious articles about Trump taken down

Here's what to know:

Here's what to know, live coverage contributors 18.

4:41 p.m. EDT 4:41 p.m. EDT

4:39 p.m. EDT 4:39 p.m. EDT

4:31 p.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 4:31 p.m. EDT

4:26 p.m. EDT 4:26 p.m. EDT

4:22 p.m. EDT 4:22 p.m. EDT

4:15 p.m. EDT 4:15 p.m. EDT

4:07 p.m. EDT 4:07 p.m. EDT

3:54 p.m. EDT 3:54 p.m. EDT

3:51 p.m. EDT 3:51 p.m. EDT

3:36 p.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 3:36 p.m. EDT

3:31 p.m. EDT 3:31 p.m. EDT

3:23 p.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 3:23 p.m. EDT

3:09 p.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 3:09 p.m. EDT

3:06 p.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 3:06 p.m. EDT

2:50 p.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 2:50 p.m. EDT

2:48 p.m. EDT 2:48 p.m. EDT

2:41 p.m. EDT Key update 2:41 p.m. EDT

2:36 p.m. EDT Key update 2:36 p.m. EDT

2:33 p.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 2:33 p.m. EDT

2:21 p.m. EDT 2:21 p.m. EDT

2:13 p.m. EDT 2:13 p.m. EDT

2:04 p.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 2:04 p.m. EDT

2:00 p.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 2:00 p.m. EDT

1:59 p.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 1:59 p.m. EDT

1:57 p.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 1:57 p.m. EDT

1:30 p.m. EDT 1:30 p.m. EDT

1:15 p.m. EDT 1:15 p.m. EDT

1:02 p.m. EDT 1:02 p.m. EDT

12:58 p.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 12:58 p.m. EDT

12:56 p.m. EDT 12:56 p.m. EDT

12:54 p.m. EDT 12:54 p.m. EDT

12:53 p.m. EDT 12:53 p.m. EDT

12:45 p.m. EDT Key update 12:45 p.m. EDT

12:35 p.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 12:35 p.m. EDT

12:34 p.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 12:34 p.m. EDT

12:32 p.m. EDT 12:32 p.m. EDT

12:31 p.m. EDT Key update 12:31 p.m. EDT

12:29 p.m. EDT 12:29 p.m. EDT

12:27 p.m. EDT 12:27 p.m. EDT

12:09 p.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 12:09 p.m. EDT

12:08 p.m. EDT 12:08 p.m. EDT

11:56 a.m. EDT 11:56 a.m. EDT

11:48 a.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 11:48 a.m. EDT

11:44 a.m. EDT 11:44 a.m. EDT

11:43 a.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 11:43 a.m. EDT

11:42 a.m. EDT Key update 11:42 a.m. EDT

11:40 a.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 11:40 a.m. EDT

11:39 a.m. EDT 11:39 a.m. EDT

11:27 a.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 11:27 a.m. EDT

11:25 a.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 11:25 a.m. EDT

11:25 a.m. EDT 11:25 a.m. EDT

11:13 a.m. EDT 11:13 a.m. EDT

11:00 a.m. EDT 11:00 a.m. EDT

10:59 a.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 10:59 a.m. EDT

10:56 a.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 10:56 a.m. EDT

10:54 a.m. EDT 10:54 a.m. EDT

10:50 a.m. EDT 10:50 a.m. EDT

10:49 a.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 10:49 a.m. EDT

10:42 a.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 10:42 a.m. EDT

10:38 a.m. EDT 10:38 a.m. EDT

10:36 a.m. EDT 10:36 a.m. EDT

10:19 a.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 10:19 a.m. EDT

10:18 a.m. EDT Key update 10:18 a.m. EDT

10:16 a.m. EDT 10:16 a.m. EDT

10:13 a.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 10:13 a.m. EDT

10:12 a.m. EDT 10:12 a.m. EDT

10:04 a.m. EDT 10:04 a.m. EDT

9:59 a.m. EDT 9:59 a.m. EDT

9:58 a.m. EDT 9:58 a.m. EDT

9:58 a.m. EDT Key update 9:58 a.m. EDT

9:56 a.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 9:56 a.m. EDT

9:55 a.m. EDT 9:55 a.m. EDT

9:53 a.m. EDT 9:53 a.m. EDT

9:50 a.m. EDT 9:50 a.m. EDT

9:49 a.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 9:49 a.m. EDT

9:44 a.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 9:44 a.m. EDT

9:43 a.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 9:43 a.m. EDT

9:41 a.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 9:41 a.m. EDT

9:40 a.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 9:40 a.m. EDT

9:35 a.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 9:35 a.m. EDT

9:33 a.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 9:33 a.m. EDT

9:31 a.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 9:31 a.m. EDT

9:29 a.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 9:29 a.m. EDT

9:26 a.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 9:26 a.m. EDT

9:25 a.m. EDT 9:25 a.m. EDT

9:23 a.m. EDT 9:23 a.m. EDT

9:16 a.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 9:16 a.m. EDT

9:13 a.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 9:13 a.m. EDT

9:09 a.m. EDT 9:09 a.m. EDT

9:02 a.m. EDT 9:02 a.m. EDT

8:54 a.m. EDT 8:54 a.m. EDT

8:48 a.m. EDT Key update 8:48 a.m. EDT

8:37 a.m. EDT 8:37 a.m. EDT

8:33 a.m. EDT REPORTING FROM THE NEW YORK COURTHOUSE 8:33 a.m. EDT

8:30 a.m. EDT Key update 8:30 a.m. EDT

8:29 a.m. EDT 8:29 a.m. EDT

8:28 a.m. EDT 8:28 a.m. EDT

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Stages of Report Writing. Like any writing task, report writing proceeds in three stages: Preparation, drafting, and revising. Preparation includes observing, interviewing, investigating, and taking notes. Drafting involves organizing and recording the information on paper or a laptop.

Next, the effective case summary lays out your investigation and findings succinctly and in an orderly, logical and easy to read format. This allows the prosecutor to quickly gain a solid understanding of the facts of the case, as well as any potential defenses. A complete list of witnesses, evidence and analysis will provide the prosecutor ...

76545. Author (s) R C Levie; L E Ballard. Date Published. 1981. Length. 218 pages. Annotation. This handbook for criminal justice personnel outlines a basic process for writing reports on investigations and then presents sample reports on a variety of cases in law enforcement, corrections, probation, parole, and security.

Report Writing for Criminal Justice Professionals covers everything officers need to learn—from basic English grammar to the difficult but often-ignored problem of creating documentation that will hold up in court. This new edition includes updates to reference materials and citations, as well as further supporting examples and new procedures ...

Assignment: Complete the assignment, Create a Criminal Justice Report Summary. Week 3 - To Do List Learn: Read Chapters 5 and 9 from Report Writing for Criminal Justice Professionals. Discuss: Complete the discussion, Capturing Essential Information. Quiz: Complete the Quiz on Chapters 1, 2, 4, 5, and 9.

The final project for this course is the creation of an executive summary report. You will write a summary, conduct a crime assessment, and create a profile of a criminal. You will then develop a conclusion and consider the investigative use of the information you have compiled. Criminal psychology encompasses a wide range of information about ...

The section on the modernization of report writing contains one chapter on innovations and predictions in criminal justice. The discussion of innovations focuses on the use of translated forms and the automation of report writing. Other topics covered in this section include report dictation, computer-aided dispatching systems and records ...

The criminal justice process is dependent on accurate documentation. Criminal justice professionals can spend 50-75 percent of their time writing administrative and research reports. The information provided in these reports is crucial to the functioning of our system of justice. Report Writing for Criminal Justice Professionals, Sixth Edition, provides practical guidance—with specific ...

The criminal justice process is dependent on accurate documentation. Criminal justice professionals can spend 50-75% of their time writing administrative and research reports. Report Writing for Criminal Justice Professionals, Fifth Edition provides practical guidance--with specific writing samples and guidelines--for providing strong reports.

The purpose of this manual is to provide guidance to police and community service officers at the Sacramento State Police Department regarding report writing. A law enforcement officer's ability to document the facts and activities of an incident directly reflects of the professionalism of the officer and the department, and also affects the ...

criminal and terrorism activities. Analytical personnel initiate inquiries, conduct information searches, and act as points of contact for information gathered. 2. Increases the ability to prosecute criminals.Personnel assigned to the analytical function develop summary tables, charts, maps, and other graphics for use in a grand jury or trial.

A better path forward for criminal justice. George Floyd's death at the hands of police in May 2020 and frequent events like it across America have added new urgency and momentum to the drive to ...

Writing in uppercase is an old technique used to correct bad penmanship, but since we are writing in a word processor, all uppercase writing is not needed. Spellcheck also must be configured correctly for it to catch mistakes in uppercase. 3. Read your report aloud. The best advice I ever received in school is to read reports aloud.

-- Created using PowToon -- Free sign up at http://www.powtoon.com/youtube/ -- Create animated videos and animated presentations for free. PowToon is a free...

Other Ideas - For Police Agencies. 1. Officers in Patrol or Street-Level Units: The Matrix generally indicates that patrol can improve its crime control effectiveness by balancing their reactive, rapid-response 911 approach, with proactivity at crime "hot spots" or problem places in between calls for service.

Date Published: October 1, 2020. Based on the experiences of nine medium-to- large law enforcement agencies that participated in crime analysis assessments under the Bureau of Justice Assistance's (BJA's) National Public Safety Partnership (PSP) program, this report summarizes the common findings and recommendations of these agencies from their ...

within the criminal and juvenile justice systems.This report presents more than 250 recommendations targeted to nearly every profession that comes in contact with crime victims—from justice practitioners,to victim service,health care,mental health,legal,educational,faith,news media, and business communities—and encourages them to redouble their

2 Create A Criminal Justice Report Summary The chief has asked me to lead a seminar for you all pertaining to the five commonly used criminal justice reports. In this seminar you will learn how to determine the type of criminal justice report to use for a given situation. You'll also become familiar with the different types of reports our department uses.

Summary Report Week 2 Assignment-Incident Reports An incident report is used to document injuries, accidents, property damage, health and safety, and security breaches. It essentially is used for any type of incident that has occurred. This type of report is used by most agencies, that report and document the things that occur.

a report or screenshot of the programming results, affidavit of acceptance of work, or summary database). Data collection cooperation agreements with other county offices and departments are strongly recommended so that the county can demonstrate it will be able to meet data collection and evaluation goals. vi.

Talk with an admissions advisor today. Fill out the form to receive information about: Program Details and Applying for Classes; Financial Aid and FAFSA (for those who qualify)

WASHINGTON - Today, DEA Administrator Anne Milgram announced the release of the 2024 National Drug Threat Assessment (NDTA), DEA's comprehensive strategic assessment of illicit drug threats and trafficking trends endangering the United States. For more than a decade, DEA's NDTA has been a trusted resource for law enforcement agencies, policy makers, and prevention and treatment ...

Simpson Thacher & Bartlett has widened its pay spread for equity partners Firm's top earners can make more than $20 million annually Top partners at Simpson Thacher & Bartlett are expected to earn more than $20 million this year after the Wall Street law firm widened the spread between its highest ...

Justice Juan M. Merchan, the judge presiding over Mr. Trump's criminal trial in Lower Manhattan, on Monday warned the former president that should he continue to defy a gag order, he might end ...

Michael Cohen, Donald Trump's fixer-turned-nemesis, testified Monday in his former boss's criminal trial in New York, recounting how he came to pay off Stormy Daniels, an adult-film actress ...