How to Write a Professional Crime Scene Report

Feeling behind on ai.

You're not alone. The Neuron is a daily AI newsletter that tracks the latest AI trends and tools you need to know. Join 400,000+ professionals from top companies like Microsoft, Apple, Salesforce and more. 100% FREE.

A crime scene report is a vital document in investigations that provides an accurate and detailed account of the events that took place. It serves as the foundation for decisions made by investigators, prosecutors, and judges and, as such, must be properly written and formatted. In this article, we will discuss the components of a professional crime scene report and provide tips for effective report writing.

Understanding the Importance of a Crime Scene Report

A crime scene report is a written record of observations, interviews, and analyses conducted during an investigation. It documents the actions taken by investigators and provides a detailed account of the crime scene. The report is an objective document that should not contain personal opinions or biases. It should be written in a clear, concise, and organized manner to facilitate communication among investigators, prosecutors, and judges.

When it comes to solving crimes, the crime scene report is one of the most important pieces of evidence. It provides a detailed account of what happened at the crime scene and can be used to piece together the events leading up to and following the crime. Without a thorough and accurate crime scene report, investigators may miss crucial evidence or fail to identify key suspects.

The Role of a Crime Scene Report in Investigations

A crime scene report is a critical component of any investigation. It provides a visual representation of the crime scene, including the location of evidence, the condition of the victim, and other pertinent details. The report helps investigators and prosecutors to reconstruct the events that occurred at the crime scene, identify suspects, and determine the appropriate charges.

Crime scene reports are used by law enforcement agencies, forensic scientists, and legal professionals to ensure that justice is served. They are often used as evidence in court to support the prosecution's case and to help the judge and jury understand the events that took place at the crime scene.

Legal Implications of an Inaccurate or Incomplete Report

An inaccurate or incomplete crime scene report can have serious legal consequences. It can compromise the prosecution of a case and lead to wrongful convictions or acquittals. A poorly written report can also be challenged in court, casting doubt on the credibility of the investigator and the investigation as a whole. Therefore, it is crucial that the report accurately reflects the observations and actions of the investigating team.

It is important to note that crime scene reports are not only used to prosecute criminals, but they can also be used to exonerate innocent individuals. If a report is inaccurate or incomplete, it can lead to the wrong person being charged with a crime. This is why it is essential that investigators take the time to document every detail of the crime scene accurately.

In conclusion, a crime scene report is a vital component of any investigation. It provides a detailed account of what happened at the crime scene and can be used to identify suspects and prosecute criminals. It is essential that the report is accurate, complete, and free of personal biases to ensure that justice is served.

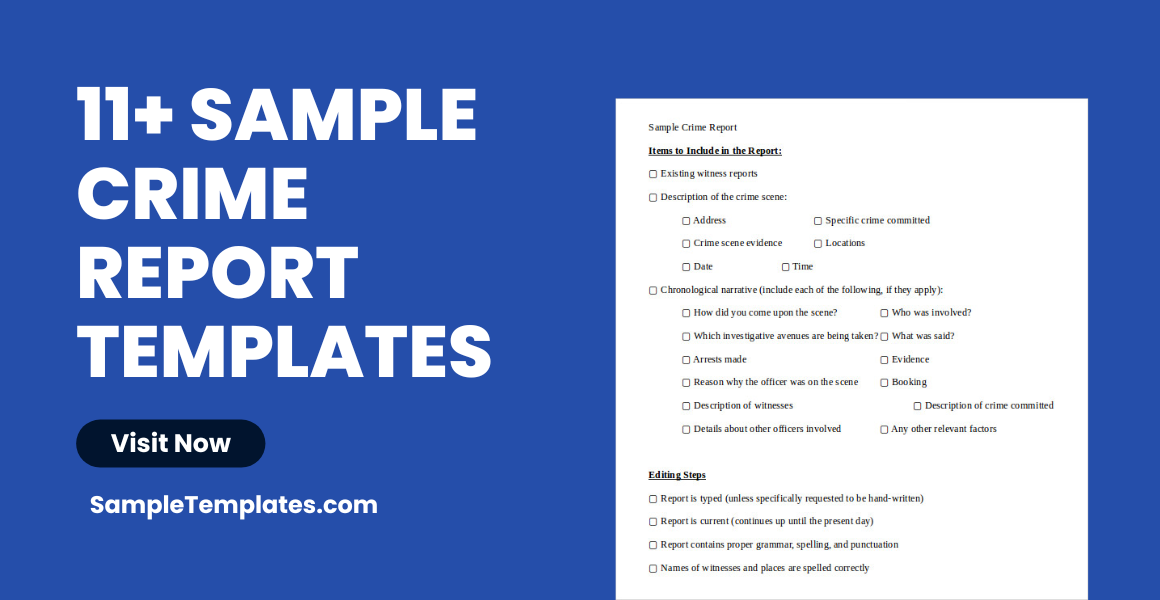

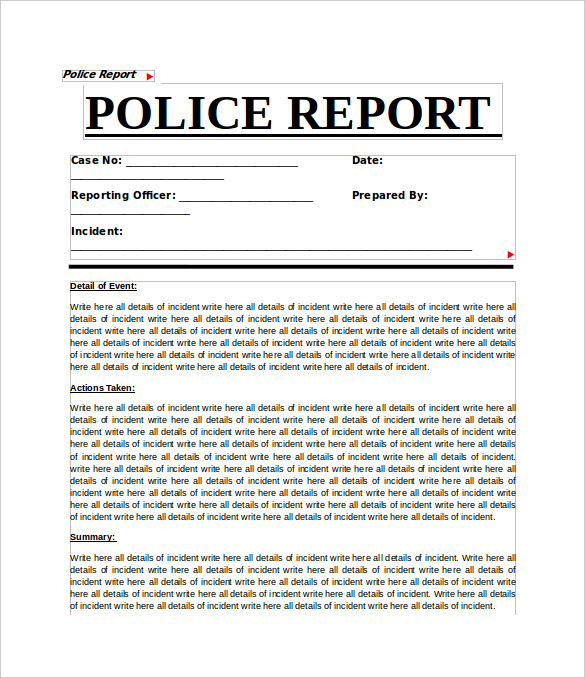

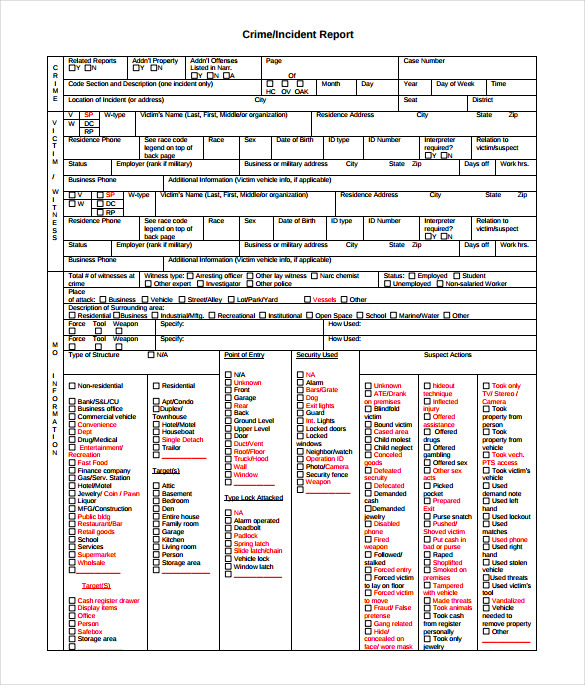

Essential Elements of a Professional Crime Scene Report

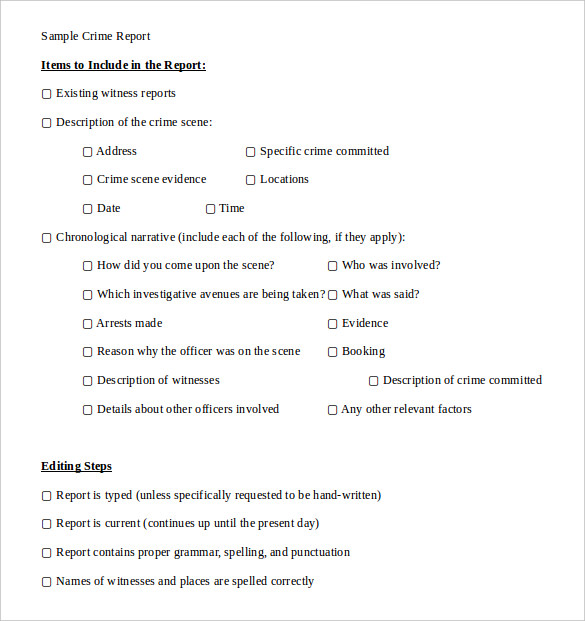

A professional crime scene report should include specific elements that are essential for an accurate and comprehensive document.

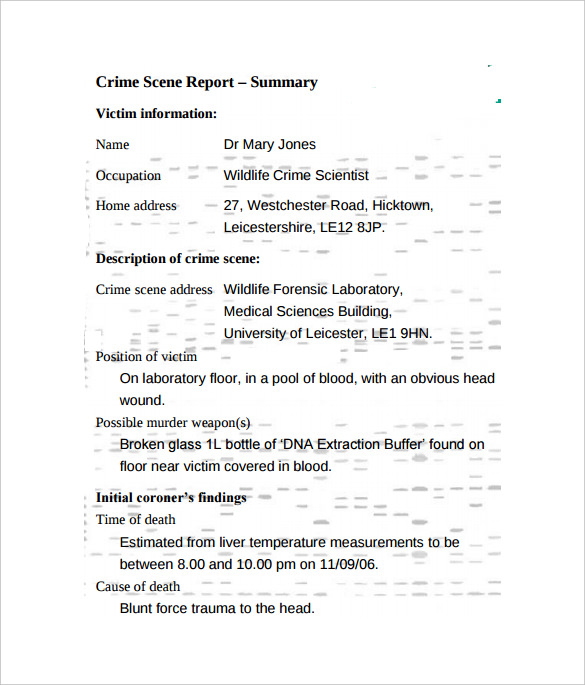

Accurate and Detailed Descriptions

The report should contain accurate and detailed descriptions of the crime scene, including the location, condition, and position of the victim, as well as any other relevant details such as the presence of weapons or drugs.

Proper Documentation of Evidence

The report should document any evidence found at the crime scene, including its location, condition, and how it was collected. All evidence should be properly labeled and packaged to ensure its integrity.

Inclusion of Photographs and Sketches

Photographs and sketches are essential elements of a crime scene report. They provide a visual representation of the crime scene and can help reconstruct the events that took place. All photographs and sketches should be properly labeled and dated.

Chronological Order of Events

The report should describe the events that took place at the crime scene in chronological order, including the actions taken by the investigating team. The report should be organized in a logical and concise manner to facilitate communication among investigators, prosecutors, and judges.

Tips for Effective Crime Scene Report Writing

Effective crime scene report writing requires attention to detail, clear communication, and objectivity. Here are some tips for writing an effective crime scene report.

Using Clear and Concise Language

The report should be written in clear and concise language that is free of technical jargon. The language used should be appropriate for the intended audience and should avoid the use of personal opinions or biases.

Avoiding Personal Opinions and Biases

The report should be objective and should not contain personal opinions or biases. The report should be based solely on the evidence found at the crime scene and the observations made by the investigating team.

Ensuring Accuracy and Consistency

The report should accurately reflect the observations and actions of the investigating team. The report should be consistent with any other reports or documentation related to the investigation.

Proofreading and Editing Your Report

The report should be proofread and edited to ensure accuracy and clarity. Any errors, inconsistencies, or inaccuracies should be corrected before the report is finalized.

Common Mistakes to Avoid in Crime Scene Reporting

Investigating crime scenes and writing crime scene reports can be challenging. Here are some common mistakes to avoid when writing a crime scene report.

Overlooking Important Details

It is important to take note of every observation and detail at the crime scene. Failing to document these details can lead to an incomplete or inaccurate report.

Relying on Memory Instead of Notes

Memory can be unreliable, especially in high-stress situations. Investigators should take detailed notes of their observations and actions at the crime scene to ensure accuracy and completeness of the report.

Using Jargon or Technical Terms Without Explanation

The report should be written for a general audience, so the use of technical jargon or terms should be avoided. If technical terms are necessary, they should be explained in simple language.

Failing to Update the Report as New Information Emerges

When new information emerges during the investigation, the report should be updated accordingly. Failing to update the report can lead to inconsistencies and inaccuracies.

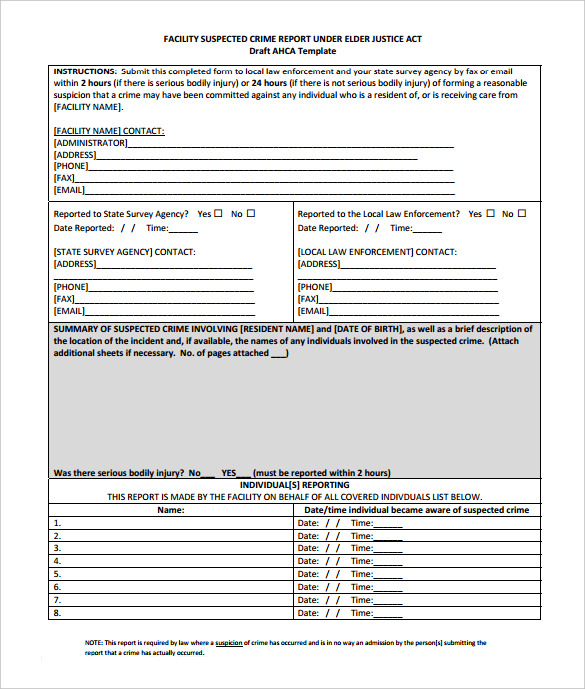

ChatGPT Prompt for Writing a Crime Scene Report

Use the following prompt in an AI chatbot . Below each prompt, be sure to provide additional details about your situation. These could be scratch notes, what you'd like to say or anything else that guides the AI model to write a certain way.

Please compose a thorough and detailed report of a crime scene, including all relevant information and evidence that may be useful in the investigation and prosecution of the crime. Your report should be comprehensive and accurate, providing a clear and detailed description of the scene, any witnesses or suspects present, and any physical evidence that may be relevant to the case. Please ensure that your report is written in a clear and concise manner, with all relevant details and information included.

[ADD ADDITIONAL CONTEXT. CAN USE BULLET POINTS.]

Writing a professional crime scene report is a vital component of any investigation. A well-written report provides an accurate and detailed account of the events that took place and facilitates communication among investigators, prosecutors, and judges. By following the guidelines and tips outlined in this article, investigators can ensure that their crime scene reports are accurate, comprehensive, and effective.

You Might Also Like...

- Written Documentation at a Crime Scene

Mike Byrd Miami-Dade Police Department Crime Scene Investigations

In an Organized step by step approach Scene Documentation is one of the stages in the proper processing of a crime scene. The final results of a properly documented crime scene is the ability of others to take our finished product to use in either reconstructing the scene or the chain of events in an incident and our court room presentation. In documenting the scene there are actually 3 functions or methods used to properly document the crime scene. Those methods consist of written notes which will ultimately be used in constructing a final report, crime scene photographs, and a diagram or sketch. Consistency between each of these functions is paramount.

Each method is important in the process of properly documenting the crime scene. The notes and reports should be done in a chronological order and should include no opinions, no analysis, or no conclusions . Just the facts!!!! The crime scene investigator or evidence recovery technician should document what he/she sees, not what he/she thinks. The final report should tell a descriptive story. A general description of the crime scene should be given just as the investigator sees it when he/she does the initial walk through of the scene.

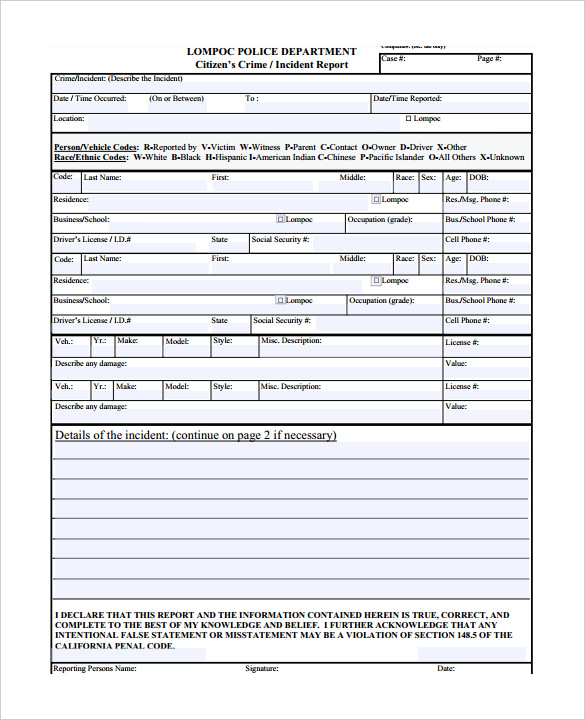

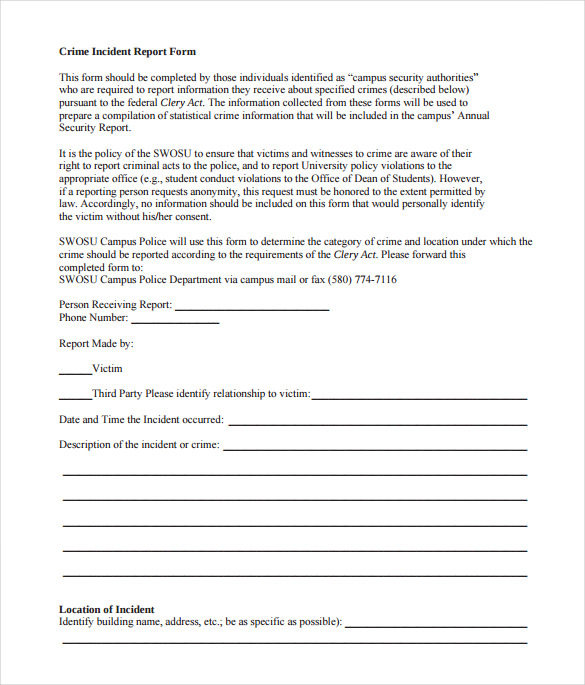

Each department or agency has a method which they use for written documentation of the crime scene. There investigator/technician should follow his/her departments assigned procedures for written documentation. The importance of sharing information can never be over-looked. This article is intended to share ideas in the area of uniform documentation as an example of the format that is used by my department. We use a narrative section of the report divided it into 5 categories. The categories are summary, scene (including a detailed body description if in a death investigation), processing, evidence collected, and pending.

The summary would basically give the details of how we were initiated into the investigation. For an example: " At the request of Robbery Detective J. Doe, this writer was requested to respond to assist in processing the scene of an armed robbery involving 4 unknown masked subjects. Det. J. Doe's preliminary investigation revealed that the subjects startled the victim as she returned home from shopping". For further details of this investigation refer to Det. J. Doe's report.. Our summary is brief and does not include a lot of he said, she said information.

In the scene section of the narrative we give a detailed description of the scene as it is seen upon our approach. The scene description usually includes anything that is unusual and out of place. Any weather or environment conditions are also included. Again this is a description of what we see not what we think. The Evidence observed, its location, condition, or anything remarkable about the item will be included in our scene description section. This would also correspond to any identification markers used to number or label the items of evidence. These remarks would all be consistent with any numbers, letters, or labels indicated in the photographs, or drawn into a sketch of the scene.

The processing section is for our units to describe what we did, if assistance was needed during the processing stages, who we had assisting, and what functions they did.

The evidence collection section is to organize what evidence we and others assisting were able to recover from the crime scene, where the items were recovered from, and what part of the lab the items were directed to for analysis.

The pending section would be for any known tasks that would need to be completed at a later date in the investigation.

Recently I was asked to give an opinion on the crime scene portion of a cold case investigation which had occurred more than 20 years earlier. I agreed to take a look at everything to give my interpretation of the crime scene from the work product. So the reports and pictures were ordered from the original files.

Earn a Degree in Crime Scene Investigation, Forensic Science, Computer Forensics or Forensic Psychology

When the items came in the mail the report consisted of a one page, one paragraph narrative. The scene photographs consisted of several overall prospective of a wooded area. I could be of no assistance to my fellow college. But the experience best illustrates how important it is to properly use the tools at hand. We are brought in to assist in the beginning stages of an investigation when very limited information is known. We should realize that our work product may need to be viewed extensively by someone years from now for interpretation. The written documentation, photographs, and simple sketch need to tell the scene story. Hopefully by sharing this simple organized method it will be of some assistance to you.

About the Author

How to write organized and concise police reports

Set the scene, by introducing the people, property and other information before it is discussed.

Police report writing sets the scene to explain and understand the incident. (Photo/West Midlands Police via Flickr)

The information and methods in this article are more fully discussed in John Bowden’s excellent book “ Report Writing For Law Enforcement & Corrections .” It is available from Amazon and other booksellers.

Article updated October 19, 2018

What is the secret to good police report writing ? The answer is organization and clarity. By following these two principles, you’re already on the path to a great report. A major problem for a lot of report writers is organization, not writing the report in chronological order.

One of the biggest challenges with the concept of chronological order is the order according to whom? Is it the writer, the victim, a witness or perhaps even the suspect? Each of these actors in the event has their own perspective to the order of events. Complete the “Access this Police1 Resource” box on this page to download a copy of this guide to print and keep at your desk.

Where should I begin the police report?

For the writer, the incident starts when they first arrive on the scene. For the victim, it is when they first realize they are the victim. For the witness, it is when they first see the action that makes them a witness. Of course, for the suspect, it is when they make that conscious decision to commit the crime. True chronological order means the order in which the events actually occurred.

Many reports begin this way:

While on patrol, (date and time) I received a call to (location). Upon my arrival, I spoke to the victim, (name) who said...

This format is told in the order in which the events occurred to the writer. It can work and has worked since report writing began, in simple cases with few principles, facts and evidence. In these cases, it is easy to use and can be understood fairly well.

The problems in clarity occur when there are multiple principals, a significant amount of evidence and events occurred over a longer time period of time.

You know you’re having problems organizing the report when it’s unclear where or how to begin the report.

Tell the incident story backward

This format is not what I would call a report. It is a statement from the writer saying what happened to them. In fact, in most cases, the crime has already occurred and the writer is telling the story backward. When asked why they write this way, many report writers will state that they don’t want to make it look like they are making it up — they want to emphasize where they received the information.

I have a simple startup paragraph that relieves this concern and makes it clear where the information came from:

I, (name), on (date and time) received a call to (location) reference to (the crime). My investigation revealed the following information.

This one short paragraph is interpreted to mean you talked to all the parties involved and examined the evidence. A report is not a statement of what the writer did (although this format can more or less work). A report tells the story of what happened, based on the investigation.

Some writers are concerned about being required to testify about what the report revealed. This is not a concern. You only testify to what you did, heard or saw.

When a witness tells you what they saw, you cannot testify to those facts, only that they said it to you. Their information should be thoroughly documented in their own written statements. Each witness, victim or suspect will testify to their own part in the case. Crime scene technicians and experts will testify to the evidence and how it relates to the case.

Your story, told in true chronological order, will be the guide to the prosecutor of what happened. It is like the outlines in a coloring book. The prosecutor will add the color with his presentation, using all the subjects and experts as his crayons to illustrate the picture – the story.

The investigating officer that writes the report is one of those crayons.

Set the scene

We start the process with the opening statement I outlined above. You can change the verbiage to suit your own style. The important phrase is the last sentence, “My investigation revealed the following information.” This tells the reader that this is the story of what happened. Your actions will be inserted in the story as it unfolds.

When you start, set the scene. Introduce the people, property and other information before it is discussed. For example, with a convenience store robbery, set the time, location and victim before you describe the action.

Mr. Jones was working as a store clerk on Jan 12th, 2013, at the Mid-Town Convenience store, 2501 E. Maple Street, at 2315 hours. Jones was standing behind the counter, facing the store. There were no other people in the store.

These first few sentences set the scene. The next sentence is the next thing that happens.

Approximately 2020 hours the suspect walked in the front door.

Each of the following sentences is merely a statement of what happened next.

- The suspect walked around the store in a counterclockwise direction.

- When he emerged from the back of the store he was wearing a stocking mask.

- He walked up to the counter and pointed a small revolver at the clerk.

- He said, “Give me all the money in the register...”

If you have multiple subjects involved in the event, introduce and place them all at the same time, before starting the action. A good example of this is a shoplifting case with multiple suspects and multiple loss prevention officers. Before starting the action, place all the people. This makes it easy to describe the action when it starts.

After you finish telling the story, you can add all the facts that need to be included in the report not brought out in the story. Here are facts that can be included, if available:

- Evidence collected

- Pictures taken

- Statements of witnesses, the victim and even the suspect.

- Property recovered

- Any facts needed to be documented in the case

Using this process will ensure your police report is clear and complete.

John Bowden is the founder and director of Applied Police Training and Certification. John retired from the Orlando Police Department as a Master Police Officer In 1994. His career spans a period of 21 years in law enforcement overlapping 25 years of law enforcement instruction. His total of more than 37 years of experience includes all aspects of law enforcement to include: uniform crime scene technician, patrol operations, investigations, undercover operations, planning and research for departmental development, academy coordinator, field training officer and field training supervisor.

Hilbert College Global Online Blog

The anatomy of a crime scene: examples, investigation and analysis, written by: hilbert college • jun 4, 2023.

The Anatomy of a Crime Scene: Examples, Investigation and Analysis ¶

Law enforcement is trained to gather evidence and solve crimes. However, a crime scene involves many people and many steps, so everyone involved must work together to effectively process a crime scene. Understanding the anatomy of a crime scene can make or break a case.

To learn more, check out the infographic below, created by Hilbert College Global’s online Bachelor of Science in Criminal Justice.

What Is a Crime Scene? ¶

A crime scene describes the location where a crime takes place. It can also include where evidence is found or where a suspect lives.

Robberies ¶

A robbery is a theft that involves violence or the threat of violence. Robbery crime scenes may include, convenience stores, commercial establishments, banks, private residences, parking lots or the streets. Basically, it’s anywhere a person was robbed.

Homicides ¶

A homicide is a murder committed intentionally or during the commission of another crime. Homicide crime scenes may include where a victim was killed and where the body was found. It may also include where a murder was planned or where the murder weapon was discarded.

Secondary Locations ¶

A secondary location is a site important to identifying and prosecuting a suspect. Secondary locations may include the paths a suspect traveled during the commission of a crime, where a second crime was committed, or a location where suspects convened before or after a crime. These crime scenes may be found after the initial crime is discovered.

An assault is the intentional harming of another person physically. Assault crime scenes may include a residence, highways and sidewalks, parking garages and lots, convenience stores or hotels and motels. An assault may happen anywhere, so crime scenes can vary.

Digital Crime Scenes ¶

Some crimes are committed online or through invasive malware. For cybercrimes, investigators go through victims’ digital devices to find evidence. Suspects’ computers and mobile devices are also considered crime scenes.

Who’s on the Scene? ¶

- Investigators interview witnesses and gather information from law enforcement on the scene. They also manage information given to the press.

- Crime scene technicians identify physical evidence at the scene. They also photograph crime scenes so law enforcement and lawyers can see the original scene. Once they’ve finished at the crime scene, they write final reports of their findings.

- Police officers are often first at the scene and alert necessary law enforcement. They protect the crime scene by cordoning it off. They will also keep witnesses so the Investigator can interview them.

- Medical examiners and coroners examine victims’ bodies and in the morgue. They also collect physical evidence from victims. Once they’ve analyzed the scene, they will provide law enforcement with information.

How Long Is It a Crime Scene? ¶

A crime scene isn’t considered cleared until the investigative team has gathered all possible evidence and information. This may take between one and two days. If a crime takes place over multiple locations, it may take longer to process each crime scene and clear them all.

What Happens at a Crime Scene? ¶

At the crime scene, law enforcement dispatches a crime scene detail to process the scene through:

Evidence Gathering ¶

Evidence can prove motive, opportunity, intent, planning and identity. A perimeter must be established to keep the crime scene from being compromised. Law enforcement searches the scene for physical evidence and any clues about the subject.

Technicians photograph blood evidence, victims’ wounds, surrounding areas and physical evidence before being bagged. The scene is sketched with measurements. Everything is put into evidence bags, labeled and sent to the appropriate authorities.

Witness Questioning ¶

Law enforcement establishes witnesses and obtains valid identification. Then, they separate each witness and record their name, birthday, address and all phone numbers. Finally, witnesses are interviewed individually on scene or at the office location.

Investigation ¶

The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) lists the steps of a well-planned investigation as:

- First responders notify correct personnel.

- The prosecutor, the forensic doctor and scientific/technical assistance are assigned to the case.

- Parties arrive at the crime scene.

- Cordon off the crime scene.

- Determine the proper procedures and apply.

- Keep the location secure.

- Medical personnel takes responsibility for the scene.

- Decide what information the media will receive.

- Interview witnesses.

- Disperse uninvolved bystanders.

- Record the crime scene.

- Notify involved civilians.

- Take statements and gather information.

Processing ¶

USAID lists the most important steps while processing a scene as follows:

- Determine where to search for evidence and suspects.

- Describe the immediate setting as evidence.

- Properly gather and remove evidence.

- Identify, label and tag evidence.

- Establish the chain of custody from the scene.

- Analyze the evidence for information.

- Preserve the evidence for trial.

- Use available information to interpret the crime scene.

What Happens Next? ¶

Once all possible information has been gathered from a crime scene, investigators and attorneys build a case to either convict or exonerate a suspect.

Forensic Analysis ¶

Forensic analysts examine the crime scene evidence. Whether the evidence is physical or digital, forensic analysts extract information and provide it to the defense and prosecution. Forensic analysts may also serve as expert witnesses.

Identifying Suspects ¶

Through examining the crime scene and data provided by forensic analysts, investigators assemble a list of suspects. Investigators interview possible suspects and reinterview witnesses. When suspects are identified, they may be brought in for questioning or arrested.

Preparing for Court ¶

Investigators turn over their findings to prosecutors and defense lawyers. The lawyers may return to the crime scene to better understand the crime. Suspects work with the defense to prove their innocence. Both parties gather expert witnesses to strengthen their cases.

Presenting the Case ¶

During trial, witnesses take the stand to explain what they saw. Lawyers reconstruct the crime scene to either prove or disprove a defendant’s guilt. Evidence gathered at the crime scene is presented to the judge and jury.

Analysis of a Crime Scene ¶

Every crime leaves evidence behind, and law enforcement is trained to identify it. At the crime scene, technicians, officers and investigators gather all available evidence and do their best to find a suspect. Many steps and different professionals are involved, and they all must understand their roles and how crime scenes function.

Britannica, Homicide

Encyclopedia.com, Crime Scene Investigation

Federal Bureau of Investigation, Trend of Violent Crime from 2011 to 2021

Find Law, Robbery Overview

My Law Questions, “What Is A Crime Scene?

National Institute of Justice, Digital Evidence and Forensics

NOLO, “Assault, Battery, and Aggravated Assault” United States Attorney General, Homicide Scene Investigation: A Manual for Public Prosecutors

United States Attorney General, Homicide Scene Investigation: A Manual for Public Prosecutors

Recent Articles

Learn more about the benefits of receiving your degree from hilbert college.

Case IQ’s newest version includes pre-set templates, as well as AI-powered copilots for case summarization and translation. Register here to join our live run-down of these new features on June 5th!

- Resource Center

Investigation Report Example: How to Write an Investigative Report

- What is the Importance of an Investigative Report?

- How to Write an Investigative Report: "Musts"

- How CaseIQ Can Help

Preliminary Case Information

Here’s how to write an investigation report that is clear, complete, and compliant.

Do you dread the end of an investigation because you hate writing investigative reports? You’re not alone.

However, because it’s an important showcase of the investigation, you can’t cut corners on this critical investigation step. Your investigation report reflects on you and your investigation, so make sure it’s as clear, comprehensive, accurate, and polished.

How do you write an investigation report? What are the parts of an investigation report? What's an investigation report example? In this guide, you’ll learn how to make your workplace incident reports effective and efficient.

How mature are your workplace investigations?

An investigations maturity model can reveal your investigations program's strong points and areas for improvement. Learn how to evaluate your program in our upcoming fireside chat with investigations expert Meric Bloch.

An investigation report can:

- Spark some sort of action based on the findings it presents

- Record of the steps of the investigation

- Provide information for legal actions

- Provide valuable data to inform control and preventive measures

In short, your report documents what happened during the investigation and suggests what to do next.

In addition, the process of writing an investigation report can help you approach the investigation in a new way. You might think of more questions to ask the parties involved or understand an aspect of the incident that was unclear.

How to Write an Investigative Report: “Musts”

Before you begin, it’s important to understand the three critical tasks of a workplace investigative report.

- It must be organized in a such way that anybody internally or externally can understand it without having to reference other materials. That means it should have little to no jargon or specialized language and be a stand-alone summary of your investigation from start to finish.

- It must document the investigative findings objectively and accurately and provide decision makers with enough information to determine whether they should take further action. With just one read-through, stakeholders should be able to understand what happened and how to handle it.

- It must indicate whether the allegations were substantiated, unsubstantiated, or whether there’s something missing that is needed to reach a conclusion. Use the evidence you’ve gathered to back up your analysis.

You might be wondering, “What are the contents of an investigation report?” Now that you know what your report should accomplish, we’ll move on to the sections it should include.

Want to streamline the report-writing process?

Download our free investigation report template to ensure you have consistent, compliant, and complete reports for every case.

Get the Template

Investigation Report Format: What to Include in Your Workplace Incident Report

Executive summary, incident summary, allegation subject, investigation details & notes, investigation interviews, conclusion & recommendations, final edits, how case iq can help.

The executive summary should be a concise overview of the investigation from beginning to end. It should not contain any information that is not already in the investigation report.

This may be the most important component of the investigation report because many readers won’t need to go beyond this section. High-level stakeholders get an overall picture of the allegations, investigation, and outcome without having to pore over the details.

To make this section easy to read, write in an active voice. For example: “I interviewed Carrie Smith,” not “Carrie Smith was interviewed.”

Example: On February 23 rd , 2023, the Human Resources Manager received a written complaint of sexual harassment submitted by Carrie Smith, the stockroom manager. Smith claimed that on February 22 nd , 2023, her supervisor, Mark Robinson, pushed her against the wall in the boardroom and groped her breasts. Smith also alleged that Robinson on another occasion told her she was “too pretty” to be working in the stockroom and that he could arrange for a promotion for her.

On February 24th, the Human Resources Manager assigned the case to me.

On February 25th, I interviewed Carrie Smith and two witnesses to the alleged February 22 nd incident, John Jones and Pamela Miller. Jones and Miller did not corroborate the groping allegation but said they saw Smith running out of the boardroom in tears. Miller also reported hearing Robinson tell another employee, Sara Brown, that she had “a great rack”.

On February 26 th , I interviewed Mark Robinson. He denied the groping incident and said he was “just joking around” with her in the boardroom but did not actually touch her and that Smith was too sensitive. He admitted to telling Smith she was too pretty to work in the stockroom, but contends that it was meant as a compliment.

Based on the interviews with the complainant and the alleged offender, I find that the complainant’s allegation of sexual harassment is substantiated.

It is my recommendation that the company provide the respondent with a written account of the findings of the investigation and a reminder of the company’s expectations for employee behavior. I also recommend that the respondent receive sexual harassment training and be advised that repeated harassing behavior may result in further discipline up to and including termination.

This section outlines the preliminary case information in a concise format, with only the most important details. It can go either before or after the executive summary.

- Your name and investigator identification number, if you have one

- Case number

- Date the case was assigned to you

- The date the report was reviewed

- How the report was received (e.g. hotline, email to HR manager, verbal report to supervisor)

- Name of the reporter/complainant

If the reporter is an employee, record their:

- Email address

- Work telephone number

- Employment level/position

- Employee identification number

- Department identification number

If the source is not an employee, only record their:

- Personal telephone number

In either case, note the date that the report was submitted, as well as the date(s) of the alleged incident(s).

The purpose of this section is to answer the who, what, where, and when about the incident.

- What type of case is it? For example, is the case alleging harassment, discrimination, fraud, or other workplace misconduct?

- Specify the case type further. For example, is it sexual harassment, gender discrimination, accounts payable fraud, etc.

- Who is the alleged victim? For example, is it the reporter, another employee, a customer, or the whole company?

- If the alleged victim is an employee, identify the person’s supervisor.

- Were any other people involved besides the subject and the alleged victim?

- Where did the incident(s) take place?

- When did the incident(s) occur?

- Capture details of the allegation. Example : Stacey Smith alleges that John Jones, an accounts payables clerk, has been funneling payments to a dummy supplier that he has set up in the company’s procurement system. Stacey says that she noticed a discrepancy when one of the suppliers she deals with questioned a payment and she had to ask an accounts payable clerk, Tom Tierney, to pull the file for her. When Tom accidentally brought Stacey the wrong file, she saw that monthly payments were being made to a supplier she had never heard of, and that the address of the supplier was John Jones’s address. Stacey knows John’s address because her sister is John’s next-door neighbor.

Describe the allegation or complaint in simple, clear language. Avoid using jargon, acronyms, or technical terms that the average reader outside the company may not understand.

In this section, note details about the alleged bad actor. Some of this information might be included in the initial report/complaint, but others you might have to dig for, especially if the subject isn’t an employee of the organization.

For every subject, include their:

- Email (work contact if they’re an employee, personal if not)

- Telephone number (see above)

If the subject of the allegation is an employee, also include their:

- Employment status (e.g. full-time, part-time, intern, contractor, etc.)

- Business location

Begin outlining the investigation details by defining the scope. It’s important to keep the scope of the investigation focused narrowly on the allegation and avoid drawing separate but related investigations into the report.

Example: The investigation will focus on the anonymous tip received through the whistleblower hotline. The objective of the investigation is to determine whether the allegation reported via the hotline is true or false.

Next, record a description of each action taken during the investigation. This becomes a diary of your investigation, showing everything that was done during the investigation, who did it, and when.

For each action, outline:

- Type of action (e.g. initial review, meeting, contacting parties, conducting an interview, following up)

- Person responsible for the action

- Date when the action was completed

- Brief description of the action (i.e. who you met with, where, and for how long)

Be thorough and detailed, because this section of your report can be an invaluable resource if you are ever challenged on any details of your investigation.

Write a summary of each interview. These should be brief outlines listed separately for each interview.

Include the following information:

- Who conducted the interview

- Who was interviewed

- Where the interview took place

- Date of the interview

Include a list of people who refused to be interviewed or could not be interviewed and why.

Write a Report for Each Interview

This is an expanded version of the summaries documented above. Even though some of the information is repeated, be sure to include it so that you can use the summaries and reports separately as standalone documentation of the interviews conducted.

For each interview, document:

- Location of the interview

- Summary of the substance of the interview, based on your interview notes or recording.

Example: I asked Jane Jameson to describe the events of July 13 th , 2016. She said: “After work, Peter approached me as I was leaving the building and asked me if I would like to work on his team. When I said that I was happy working with my current team, he told me that my team had too many women on it and that ‘all those hormones are causing problems’ so I should think about moving to a ‘sane’ team.”

I asked her how she reacted to that. She said: I told him that I found that offensive and he said that I needed to stop being so sensitive. I just walked away.”

I asked Jane to describe the events of the next day. She said: “The next day he came to my desk and asked me if I had given any thought to moving to his team. I repeated that I was happy where I was. At that point he started massaging my shoulders and said that moving to his team would have its ‘perks’. I asked him to stop twice and he wouldn’t. Sally walked over and told him to get lost and ‘leave Jane alone’ and he left.”

I thanked Jane for her cooperation and concluded the interview.

Assess Credibility

Aside from collecting the evidence, it is also an investigator’s job to analyze the evidence and reach a conclusion. Include a credibility assessment for each interview subject in the interview report. Describe your reasons for determining that the interviewee is or isn’t a credible source of information.

This involves assessing the credibility of the witness. The EEOC has published guidelines that recommend examining the following factors:

- Plausibility – Is the testimony believable and does it make sense?

- Demeanor – Did the person seem to be telling the truth?

- Motive to falsify – Does the person have a reason to lie?

- Corroboration – Is there testimony or evidence that corroborates the witness’s account?

- Past record – Does the subject have a history of similar behavior?

Example: I consider Jane to be a credible interviewee based on the corroboration of her story with Sally and also because she has nothing to gain by reporting these incidents. She has no prior relationship with Peter and seemed genuinely upset by his behavior.

A well-written report is the only way to prove that an investigation was carried out thoroughly.

Download this free cheat sheet to learn best practices of writing investigation reports.

Get the Cheat Sheet

In this section, describe all the evidence obtained. This could include:

- Video or audio footage

- Email or messaging (e.g. Slack, Teams, etc.) records

- Employee security access records

- Computer or other device login records

- Documents or papers

- Physical objects (e.g. photos, posters, broken objects, etc.)

Number each piece of evidence for easy reference in your chain of evidence document.

As you gather and analyze evidence , it’s critically important to include and fully consider everything you find. Ignoring evidence that doesn’t support your conclusion will undermine your investigation and your credibility as an investigator. If you aren’t weighing some pieces as heavily as others, make sure you have a good explanation as to why.

In the final section of your report, detail your findings and conclusion. In other words, answer the questions that your investigation set out to answer.

This is where your analysis comes into play. However, be sure to only address the issue(s) being examined only, and don’t include any information that is not supported by fact. Otherwise, you could be accused of bias or speculation if the subject challenges your findings.

Investigation Findings Example: My findings indicate that, based on the evidence, Bill’s allegation that Jim blocked him from the promotion is true. Jim’s behavior towards Bill is consistent with the definition of racial discrimination. The company’s code of conduct forbids discrimination; therefore, Jim’s behavior constitutes employee misconduct.

It’s important for your conclusion to be defensible, based on the evidence you have presented in your investigation report. Reference reliable evidence that is relevant to the case. Finally, explain that you’ve considered all the evidence, not just pieces that support your conclusion.

In some cases, you might have been asked to provide recommendations, too. Depending on your conclusion, you may recommend that the company:

- Does nothing

- Provides counseling or training

- Disciplines the employee(s)

- Transfers the employee(s)

- Terminates or demotes the employee(s)

Example: It is my recommendation that the company provide the respondent (Jim) with a written account of the findings of the investigation and a reminder of the company’s expectations for employee behavior. I also recommend that the respondent (Jim) receive anti-discrimination training and be advised that repeated discriminatory behavior may result in further discipline up to and including termination.

Grammatical errors or missed words can take even the best investigation report from professional to sloppy. That’s why checking your work before submitting the report is perhaps the most important step of them all.

Keep in mind that your investigative report may be seen by your supervisors, directors, and even C-level executives in your company, as well as attorneys and judges if the case goes to court.

If spelling, grammar, and punctuation aren’t your strong suit, enlist the services of a writer-friend or colleague to proofread your report. Or, if you’re a lone wolf kind of worker, upgrade your skills with a writing course or a read-through of books like The Elements of Style by Strunk and White. At the very least, remember to run a spell check before you pass on any document to others.

Finally, do a quick scan to make sure you’ve included all the necessary sections and that case details are consistent.

Want more report-writing tips?

Watch our free webinar to get advice on what to include (and not include), proper language and tone, formatting tips, and more on how to effectively make an investigation report.

Watch the Webinar

RELATED: 3 Investigation Report Writing Mistakes You’re Still Making

Frequently Asked Questions

How do i write an investigation report.

To write an investigation report, you should ensure it's clear, comprehensive, accurate, and organized, documenting findings objectively and providing decision-makers with enough information to determine further action.

What are the basic parts of an investigation report?

The basic parts of an investigation report include an executive summary, preliminary case information, incident summary, allegation subject details, investigation details and notes, investigation interviews, evidence documentation, conclusion and recommendations, and final edits.

What is the purpose of an investigation report?

The purpose of an investigation report is to document the steps and findings of an investigation, providing a clear record of what occurred, suggesting actions to be taken, and potentially serving as valuable data for legal actions or informing control and preventive measures.

If you’re still managing cases with spreadsheets or outdated systems, you’re putting your organization at risk.

With all your investigation information stored in one place, you can create comprehensive, compliant investigation reports with a single click. Case IQ’s powerful case management software pulls all the information from the case file automatically, so you can close cases faster.

Learn more about how Case IQ can reduce resolution time and improve your organization’s investigations here.

Related Resources

What to ask in a whistleblower hotline use survey (and why it’s important), how an hr analyst can help your organization reduce risk.

How to Write a Crime Scene: Really Useful Links by Lucy O’Callaghan

Lucy O’Callaghan

- 16 June 2022

Attention to detail is essential when writing a crime scene; the little things can become important, and they can create the biggest problems. As it is National Crime Reading Month, this week’s column on writing a crime scene. Checking the process of how a crime scene is dealt with, and the stages of investigation to be taken wherever the story is based is a necessary part of writing. I have put together some articles, podcasts, and YouTube videos with tips and information worth considering when writing your crime scenes.

- https://www.livewritethrive.com/2015/03/02/10-tips-on-how-to-write-believable-crime-and-murder-scenes/

This article from a former Canadian homicide detective shares his tips for writing crime scenes, including understanding the mechanism of death, understanding scene access, and getting the terminology right. He encourages the writer to expand their story by using more than autopsies, toxicology, and document examination. He advises using the multitude of resources available such as undercover agents, psychological profiling, room bugs, and wires.

- https://www.crime-scene-investigator.net/document.html

Three methods usually used to document a crime scene are written notes, crime scene photographs, and a diagram or sketch. Each method is important in the process of properly documenting the crime scene. The notes and reports should be completed in chronological order and shouldn’t include opinion, analysis, or conclusions. Just the facts. Mike Byrd shares a format used by his department that uses a narrative section of the report divided into 5 categories. The categories are summary, scene, processing, evidence collected, and pending. This article explains each category. All this information is great for the writer to figure out what might go wrong or what might slip the detective’s notice.

- https://www.thecreativepenn.com/2012/07/22/writing-death-crime-scenes/

Although this is an old article it is full of great information about writing a crime scene. It discusses what writers often get wrong when writing about death, including the mechanism of death, time of death, DNA/ dental records, and how a body is identified.

- https://litreactor.com/columns/writing-the-crime-scene-winter-forensics

This article focuses on cold weather forensics, giving the writer things to consider to make your story realistic and authentic. It covers hypothermia, frostbite, frozen firearms, and snowy corpses.

- https://www.forensicsciencesimplified.org/csi/how.html

This is a simplified guide to crime scene investigations. It discusses samples that may be collected at a crime scene, the types of evidence collected, who examines the scenes, how a crime scene investigation is conducted, and how and where tests on the evidence are conducted.

- https://www.writersdetective.com/episodes/

The Writer’s Detective Bureau is a podcast hosted by veteran Police Detective Adam Richardson. Adam answers questions about criminal investigation and police work posed by crime-fiction authors and screenwriters writing crime-related stories.

- https://www.livewriters.com/podcast/sps-253-how-to-write-an-authentic-crime-scene-with-patrick-odonnell/

The Self-publishing show podcast discusses writing authentic crime and how the devil is in the details.

This video is about the fundamentals of crime scene processing. It shares tips to avoid transfer, loss, and contamination of evidence.

Dr Ian Turner, from the University of Derby, introduces the concept of crime scenes, explains how they may be different and what they have in common. He also discusses the role of a Crime Scene Investigator within a crime scene.

Writing crime scenes is not just about getting the words on the page, the process has to be accurate and the details are important. Your reader might know nothing about the police procedures or they may be a detective in the police force, so the writer must strive for accuracy in these scenes. Research is key. Asking people in the know can be really helpful and, for the most part, these people will only be delighted to help you out as long as you credit them in your novel! I hope this week’s column has been helpful. As always, let me know if there are any topics you would like me to cover. Enjoy the rest of National Crime Reading Month.

(c) Lucy O’Callaghan

Instagram: lucy.ocallaghan.31.

Facebook: @LucyCOCallaghan

Twitter: @LucyCOCallaghan

About the author

Writing since she was a child, Lucy penned her first story with her father called Arthur’s Arm, at the ripe old age of eight. She has been writing ever since. Inspired by her father’s love of the written word and her mother’s encouragement through a constant supply of wonderful stationary, she wrote short stories for her young children, which they subsequently illustrated. A self-confessed people watcher, stories that happen to real people have always fascinated her and this motivated her move to writing contemporary women’s fiction. Her writing has been described as pacy, human, moving and very real. Lucy has been part of a local writing group for over ten years and has taken creative writing classes with Paul McVeigh, Jamie O’Connell and Curtis Brown Creative. She truly found her tribe when she joined Writer’s Ink in May 2020. Experienced in beta reading and critiquing, she is currently editing and polishing her debut novel. Follow her on Instagram: lucy.ocallaghan.31. Facebook and Twitter: @LucyCOCallaghan

Subscribe to our newsletter

Get all of the latest from writing.ie delivered directly to your inbox., featured books.

Your complete online writing magazine.

Guest blogs, courses & events.

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Finance and Business

- Legal Matters

- Law Enforcement

How to Write a Police Report

Last Updated: April 13, 2024 Approved

This article was co-authored by Saul Jaeger, MS . Saul Jaeger is a Police Officer and Captain of the Mountain View, California Police Department (MVPD). Saul has over 17 years of experience as a patrol officer, field training officer, traffic officer, detective, hostage negotiator, and as the traffic unit’s sergeant and Public Information Officer for the MVPD. At the MVPD, in addition to commanding the Field Operations Division, Saul has also led the Communications Center (dispatch) and the Crisis Negotiation Team. He earned an MS in Emergency Services Management from the California State University, Long Beach in 2008 and a BS in Administration of Justice from the University of Phoenix in 2006. He also earned a Corporate Innovation LEAD Certificate from the Stanford University Graduate School of Business in 2018. wikiHow marks an article as reader-approved once it receives enough positive feedback. This article received 13 testimonials and 85% of readers who voted found it helpful, earning it our reader-approved status. This article has been viewed 1,144,518 times.

If you're a police officer or security guard, knowing how to write up a detailed and accurate report is important. A well written incident report gives a thorough account of what happened and sticks to the facts. If you're trying to write a police report, or are curious about how the police put together their reports, learning what to include and how to format the report is helpful.

Following Protocol

- Try to do your write-up using word processing software. It will look neater and you'll be able to use spellcheck to polish it when you're finished. If you write your report by hand, print clearly instead of using cursive.

Saul Jaeger, MS

Did You Know? If you call 911, a police report may or may not be generated, depending on the outcome of the call. If a police report isn't generated and you want to file one later, you can call the non-emergency number, and an officer will come out and take the report. However, if you're ever in need of emergency services, call 911.

- If you can’t write the report on the day that the incident happened, record some notes about what happened to help you when you do write the report.

- The time, date and location of the incident (Be specific. Write the exact street address, etc.).

- Your name and ID number

- Names of other officers who were present

- For example, a report might say: On 8/23/10 at approximately 2340, officer was assigned to 17 Dist. response vehicle. Officer was notified via radio by central dispatch of a 911 call at 123 Maple Street. Officer was also informed by central dispatch that this 911 call may be domestic in nature.

Describing What Happened

- For example, an officer's report could say: Upon arrival, I observed a 40 year old white male, known as Johnny Doe, screaming and yelling at a 35 year old white female, known as Jane Doe, in the front lawn of 123 Maple Street. I separated both parties involved and conducted field interviews. I was told by Mr. Johnny that he had come home from work and discovered that dinner was not ready. He then stated that he became upset at his wife Mrs. Jane for not having the dinner ready for him.

- Use specific descriptions. For example, instead of saying "I found him inside and detained him," write something like, "I arrived at 2005 Everest Hill at 12:05. I walked to the house and knocked on the door. I tried the knob and found it to be unlocked..."

- Police officers often have to write reports about auto accidents. It can be much clearer to illustrate with a picture or a diagram how the accident occurred. You can draw a picture of the street and use arrows to show how where each car was headed when they hit each other.

- For example, instead of saying “when I arrived, his face was red,” you could say, “when I arrived, he was yelling, out of breath, his face was red, and he seemed angry.” The second example is better than the first because there are multiple reasons someone’s face is red, not just that they are angry.

- Even though it is hearsay, make sure to write down what each individual at the scene said to you. It may be important, even if he or she is lying. Include any information about the witness’ demeanor, in case what he or she told you becomes controversial.

- Use the party’s name when possible, so you can avoid confusion when talking about multiple people. Also, spell out abbreviations. For example, say “personal vehicle” instead of “P.O.V.” (personally owned vehicle), and “scene of the crime” instead of “code 11,” which is a police term for “on the scene.”

- Preserve your integrity and the institution you represent by telling the truth.

Editing Your Report

- For example, if you forget to include the one party's reason why the argument started, then that would leave a gap.

- For example, if you included phrases that start with "I feel" or "I believe," then you would want to remove these to eliminate any bias in your report.

- If you have to mail or email your report, follow up with a phone call within a 10 day period. Do this to make sure your report was received.

Sample Police Report and Things to Include

Expert Q&A

- Ask your department for any templates or forms that they use, in order to make sure the report is in the proper format. Thanks Helpful 4 Not Helpful 1

- Keep a copy of the report for your records. You may need to refer back to it in the future. Thanks Helpful 4 Not Helpful 1

- Add to the report, if new information comes to light. Add an addendum that reports the new information, rather than deleting information from your original report. That information may also be important. Thanks Helpful 3 Not Helpful 1

- Do not ignore facts as irrelevant. At the time of a preliminary police report, investigators may not know the motive or suspect, so it is important to give as much objective detail as possible. Some details that seem irrelevant, may be important with new evidence or testimony. Thanks Helpful 36 Not Helpful 12

- Do not use opinions in a police report, unless you are asked to do so. A police report should be objective rather than subjective. Thanks Helpful 18 Not Helpful 5

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://www.lapdonline.org/lapd_manual/

- ↑ http://www.securityguardtraininghq.com/how-to-write-a-detailed-incident-report/

About This Article

To write a police report, you should include the time, date, and location of the incident you're reporting, as well as your name and ID number and any other officers that were present. You should also include a thorough description of the incident, like what brought you to the scene and what happened when you arrived. If you're having trouble explaining something in words, draw a picture or diagram to help. Just remember to be as thorough, specific, and objective as possible. To learn what other important details you should include in a police report, keep reading. Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Did this article help you?

Andre Robinson Sr.

Jan 7, 2022

Leah Dawson

Aug 14, 2016

Mar 25, 2017

Chelle Warnars

Sep 11, 2016

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Level up your tech skills and stay ahead of the curve

Writing Realistic Crime Scenes

These chats take place every Wed. from 3-4 p.m. EDT. You can send in your questions at any time by tweeting to me @SueColetta1 with the hashtag #ACrimeChat . They’ll be saved under the hashtag until our next chat, and you’ll be notified of the answers, as well as receiving a recap of the entire chat. Here’s how it works: I take the questions in the order they are received and RT, marking each question with Q1 (Question #1), Q2, Q3, etc. The experts answer with the corresponding A1 (Answer #1), A2, A3, etc., so those watching can follow along. We launched two weeks ago with Crime Scenes (<- the link will take you to the recap). Last week, we covered Evidence. And this week, the topic is Forensics. At the conclusion of each chat I announce the following week’s topic. You can also find the topics under the hashtag in case you’re not with us live.

These chats are a lot of fun and very informative. Because all of the experts are writers and/or crime writing consultants, if the answer to your question isn’t what you hoped, often times we can help you create a logical, realistic way around it so your story still rings true. I hope you’ll join us by going to #ACrimeChat . Incidentally, I’ve linked each member’s name with their Twitter handle so you can follow them, if you wish. I’ve also included their websites.

Now, without further ado, please welcome Captain (Ret.) Joe Broadmeadow.

In Writing Realistic Crime Stories, It’s all about the Little Things

One mistake many writers make in attempting to create an interesting scenario is they try too hard. In the real world of homicide investigations, or any serious crime for that matter, it’s the little things that create the biggest problem.

Here are two examples of actual cases where investigators faced a crime scene which told them one story and, after wasting precious time looking in the wrong direction, turned out to be something entirely different.

These are actual cases with identifying information removed to protect privacy. By understanding real-life scenarios, the writer finds unlimited possibilities.

Okay, first case.

“911, what is the nature of your emergency?”

“Help, someone shot my wife, oh my god, help. She’s bleeding, there’s blood everywhere.”

“Hold on, sir. I have help on the way…”

Thus began a series of events which would bring a veteran police officer to his knees, his own department accusing him of murdering his wife while his newborn child lay sleeping nearby.

Rescue personnel arrived first. The two paramedics were experienced and well-versed in dealing with victims and their families. They began to work on the victim, a 32-year old female, noting a gunshot wound to the head. Within a short timeframe, it became apparent the victim was deceased.

Several issues complicated the scene.

The body had been moved, forcing investigators to recreate the original position to determine trajectory.

The husband, a police officer, discovered the body after returning home from the overnight shift. He worked as a dispatcher that night and had left work at 8:00 am. When he found his wife he tried to revive her. Because he had come in contact with her, his hands were stained with blood. He told investigators he left his service weapon at home since he knew he would not be on the road that night.

On the floor next to the victim laid his department service weapon. It had been fired only once. Later examination found the husband’s prints on the barrel as well as all six cartridges, including the expended bullet. The investigator’s recovered a single round lodged in the ceiling of the bedroom. Based on the position of the body, the round would have been fired from the side, below the level of the bed, as if someone had crawled along the floor and then pressed the weapon to her temple and fired.

Stippling and powder burns surrounded the wound, indicating close contact.

At the time, the couple was in the midst of a reconciliation. Their first-born child, age two months, was still asleep in the same room where his mother died.

Based on the physical evidence and known circumstances it appeared to investigators that this was a homicide staged to look like a suicide.

All they needed was a statement from the husband, who insisted his wife had been depressed and had shot herself. But once they began the interrogation, he asked to speak to a lawyer.

Investigators went back to the scene to search for something more definitive.

One aspect of any investigation is to have early arrivers re-enact their actions. Investigators had the rescue team return to the scene along with the first responding officer. As the rescue personnel took their positions around the bed, the husband told investigators he had gone to the far side of the bed in order to assist as best he could. When he did, he moved a small changing table, pushing it further away from the bed.

This was not in his original statement.

When CSI detectives put the table back into its original position, they noticed a clear dent on the edge of the table that appeared to be a ricochet mark from the round. Once the scene had been put back into the untouched condition, it changed the entire situation.

Investigators re-examined the trajectory, and it matched perfectly with a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the temple.

Mary Jones repeatedly called her 17-year old daughter who was home sick from school. All she got was a busy signal. Concerned that something was wrong, she called a neighbor to go check.

The neighbor, an off-duty firefighter, went to the house. He knocked on the door and got no response. Sensing something was wrong, he sent his wife home to call the police.

The door was unlocked.

When he entered the residence he glanced down the hallway. Someone’s legs protruded from one of the bedrooms. Running quickly to the body, he then checked for a pulse and breathing .

Within seconds, Officers arrived on scene. The local firemen weren’t far behind. Unfortunately, it was no use. The woman had already succumbed to her injuries.

They secured the crime scene.

The firefighter who discovered the body was brought to the station for a statement. Investigators’ first impression of the crime scene showed no indication of forced entry. There was apparent sexual assault and the victim had been manually strangled.

Everything indicated the victim knew the perpetrator and let him in the house.

Under these circumstances, suspicion falls immediately on family and friends. Officers notified the father and asked him to come to the station. One of the most difficult tasks an officer faces is telling a parent their child is dead.

This is compounded when the parent is also considered a suspect. The reaction to the news can be telling and useful to the investigation.

In this case, the father showed genuine emotional responses to the news. Investigators were able to learn that the victim had stayed out of school, did not have a steady boyfriend, and there was no concern on the parent’s part that she would have someone over to the house without their knowledge.

The circumstances still lent itself to a person known to the victim.

Investigators again returned to the scene to continue their search.

A uniform sergeant, who’d been at the scene within minutes of the call, told investigators he had picked up a small table next to the door and placed the telephone back on the table. When he first arrived the phone was lying on the floor. Which explained the busy signal when the mother tried to call. Before this, he had not spoken to investigators.

Once investigators learned this new information, it changed how they viewed the crime scene.

By talking to the parents, they learned the table was normally located next to the door. From the position described by the sergeant and with the table moved back into its original position, it became apparent that someone had forced themselves through the open door, knocking the table over.

Once again, a tiny detail changed by someone who should have known better sent investigators down the wrong path.

In this case, armed with a new theory, investigators were able to locate a subject on prison work release, attending a training program in the area.

How The Murder Really Happened

The subject was attempting to break into the house. Knocking at the door, he was startled when the girl opened it. Panicked that he was not supposed to be away from his assigned training location, he forced his way inside, knocking the table over and the phone off the hook. At trial, the jury convicted him, the judge sentencing him to life.

When creating scenarios for your characters, the force combining to create tension and drama do not have to be complex or labyrinthine, often it’s the simplest things that work best. They’re also what will bite you every time if you get them wrong. Television and movies give a false impression of the nature of criminal investigations. Experience taught everyone a lesson here. The smallest detail can have serious consequences, giving writers many opportunities to wreak havoc on their characters.

Joe Broadmeadow retired with the rank of Captain from the East Providence, Rhode Island Police Department after twenty years. Assigned to various divisions within the department, including Commander of Investigative Services, he also worked in the Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Force and on special assignment to the FBI Drug Task Force. He has testified in State and Federal Court as an expert in Electronic Surveillance and Computer Forensics.

You can learn more about Joe and his books at his website and Amazon author page .

If you enjoyed this post, please share. Thank you!

- StumbleUpon

- Share on Tumblr

Sue Coletta

Sue Coletta is an award-winning crime writer and an active member of Mystery Writers of America, Sisters in Crime, and International Thriller Writers. Feedspot and Expertido.org named her Murder Blog as “Best 100 Crime Blogs on the Net.” She also blogs on the Kill Zone (Writer's Digest "101 Best Websites for Writers"), Writers Helping Writers, and StoryEmpire. Sue lives with her husband in the Lakes Region of New Hampshire. Her backlist includes psychological thrillers, the Mayhem Series (books 1-3) and Grafton County Series, and true crime/narrative nonfiction. Now, she exclusively writes eco-thrillers, Mayhem Series (books 4-9 and continuing). Sue's appeared on the Emmy award-winning true crime series, Storm of Suspicion, and three episodes of A Time to Kill on Investigation Discovery. When she's not writing, she loves spending time with her murder of crows, who live free but come when called by name. And nature feeds her soul.

You May Also Like

Serial Killer Couples: Madness Shared by Two

Talking Crime with Detective (Ret.) Kim McGath

20 comments.

EVE ANDERSON

Just little details change the whole perspective. Here we had a crime & the justice official in charge (a novice), let the family clean, removed & burn the mattress.

To this day the Justice Department try to convict someone & 2 times the Judges say Um, No.

Something is fishy & is clear that the Justice Dept. is trying to deviate the attention. The Lawyer & his group (Defensors of Poor Peiple) of the supposely murderer Lcdo. Moczó, just crush the opposition in 2 turns at the bat..

Poor child as of today the criminal is free.

Oh, how sad, Eve. Sounds like that official really messed up that crime scene…to the point where a conviction would be nearly impossible now. And unfortunately, it’s the family who suffers.

Jennifer Chase

Great post! Interesting details as the cases unfolded. Thanks for posting 🙂

Thanks, Jen. It’s nice to see you. 🙂

Extremely intriguing to see how these scenes played out and the minute details that made a difference in the findings. Thank you, Richard, for sharing your knowledge and experience with us, and thank you, Sue for having such a wonderful guest.

BTW, I think the #ACrimeChat is an awesome idea. I hope to be tweeting questions once I have some time to focus on my WIPs. I’m assuming that it’s best to only ask questions related to the topic at the time? Thanks for organizing it, Sue, and to all your experts for taking the time to share their knowledge!

We try to stay on topic, Mae, but if you reach a point in your story where you need an answer, just tweet it to me regardless of topic. The whole crew is easy-going. We all want this to work for writers, so that’s the most important thing.

I’m glad you enjoyed Joe’s post. Enjoy your week!

Joe Broadmeadow

Mae, We are always looking for topics to explore. If you have a question ask it on #ACrimeChat and we’ll add it to our list of topics

Very cool post. I assumed they weren’t all intricately woven layers of plot and false evidence. There is a balance between making things obvious and getting enough mystery to tell a good story.

Exactly, Craig. Totally agree.

As to case #1 It shows how important it is to get detailed statements from all involved. One reason why (in Canada) we don’t let anyone but the forensic investigators onto the scene while investigating is too many cooks in the kitchen. I’ve had something similar and furniture that has been moved recently usually leaves a tell. carpet leaves indentation marks, floors, lack of dust or dirt where the legs or base was located. We use the right hand rule on scenes. start to your right and go completely around the room examining and photographing everything. It is time consuming but works. The forensic investigator should have found the table to be moved and the mark left by the bullet. that information could then be brought to the husband. Never let the suspect onto the scene.

I had what looked like a natural death. the body was on the bed and was supposedly discovered by the tenant who was renting the main house while the deceased stayed in the cottage. the tenant stated that he had tried to knock on the door but when he got no response he went to the back of the cottage and looked into the room. when he saw the deceased on the bed he stated to the police officers that he opened the window and climbed in. The man was still at the scene when I arrived and I noticed he was acting strange. after hearing his story i ordered the officers to remove him. the rear window was indeed open but an examination of the siding and the window trim showed no evidence that anyone had climbed in. fingerprint examination showed only the tenants prints on the bottom of the window frame but reversed. (the prints were made while standing inside the room) further investigation of the bed sheets and pillow case showed that the deceased had been smothered. A conviction was registered.

Forensic Investigation isnt just about photographing and collecting evidence. you have to read the scene, read the evidence and go through a process of eliminations.

I enjoyed reading about your two cases, Richard. We can never have too much information for crime writers, so I thank you!

Richard, One of the problems within most agencies is the immediacy of the moment often clouds the best-laid plans. In Case #1 the position of the table in the initial view appeared to be normal. There was no reason to move it. The realities of crime scene procedures and the expectations of the perfect scene are often far apart

Garry Rodgers

Great points, Joe. Definitely coming from someone who’s been there. In my experience, most crime scenes are fairly straightforward as long as they’re investigated objectively. A big mistake I’ve seen investigators make is to form a theory and then try to make the details fit, rather than just look at what the details are saying. Like you point out, one of the biggest hindrances is when a scene has been disturbed. (Hate it when that happens 🙂

Interpretation of crime scene details is an art on its own and is something I think most crime readers enjoy working out. I guess that’s why red herrings have been such a popular device and why the “Ah-ha!” moments are so rewarding.

Thanks for weighing in, Garry. Always happy to hear your two-cents. As you know, I watch a ton of true crime on ID. My favorite is Homicide Hunter. I mention him because often times when his team gets off track they go back to the beginning and start again. It helps him clear any misconceptions that’ve crept up in the investigation and many times, he finds new information that leads him to the correct conclusion, like the cases here.

Garry, There’s an interesting case in Rhode Island that illustrates this point. A woman is found murdered. There’s some significant injuries to the victim indicating rage and perhaps a personal connection.

The body was found by an off-duty officer.