100 monumental novels from literary history

Almost 4,000 years ago, an unknown scholar in ancient Mesopotamia wrote the first known book on a series of clay tablets. The story was “The Epic of Gilgamesh,” a fictionalized recounting of the life of an ancient king of Uruk. While the art of telling stories dates back even further, this singular epic poem is in large part responsible for the development of literature as we know it today.

In the millennia since this story was first written down, there have been millions, if not billions, more books written and published. A voracious reader could charge through a stack a day and not even make a dent in the world’s literary canon. This truth poses a problem for many readers: How does one know which few thousand books to read in a lifetime? How do you determine which are worth the time and brain space, and which are not?

Today, Stacker helps readers solve this age-old quandary—at least when it comes to novels. We’ve dug through the literature of the world, using sources like Goodreads, awards lists, and New York Times Best Seller columns to round up 100 monumental novels everyone should read before they die. These books are important for a variety of reasons. Some made the list because of the powerful stories they tell. Some made the list because of the way their form or style changed writing as a whole. Some made the list because of the representation they give to underseen and undervalued cultures or identities, and some made the list simply because, like “The Epic of Gilgamesh,” their very existence changed the course of the world.

Two caveats to note before diving into the following pages. Only novels (including some ancient epic poems) were considered for the list. So many important and influential authors, like William Shakespeare and Niccolò Machiavelli, have been left out, not because their contributions aren’t great but because they never authored long-form fictional narratives. Also, for many of these works, especially the earlier ones, an exact publication date is difficult to nail down. In an effort to remain consistent, we consulted Goodreads for all publication years.

So, from ancient Greek epics like “The Odyssey” to modern hits like “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone,” read on to find out which novels Stacker considers must-reads.

The Epic of Gilgamesh

- Author: Anonymous - Date published: 1800 B.C.

Literary scholars agree that “ The Epic of Gilgamesh ” is the oldest existing piece of written fiction in the world. Early versions of the text, which is an epic poem detailing the adventures of a real-life Sumerian King named Gilgamesh, date as far back as approximately 1800 B.C. However, the most complete versions of this foundational text are more recent, dating from the 12th century B.C.

- Author: Homer - Date published: 750 B.C.

“ The Iliad ” is an epic poem about the roles of men and gods during the Trojan War. Another foundational text of world literature, the poem is attributed to the blind poet Homer. For centuries, scholars have debated whether Homer really existed , with many believing the poem may have actually been written by a group of individuals over a long period of time.

The Odyssey

- Author: Homer - Date published: 700 B.C.

You can hardly mention “The Iliad” without also mentioning “ The Odyssey .” The epic poem tells the story of Odysseus’s journey home from the Trojan War, as he battles monsters, fates, and gods to return to his home and family. Just as “The Iliad” set the stage for future groundbreaking pieces of war literature, so did “The Odyssey” set the stage for adventure tales.

The Panchatantra

- Author: Vishnu Sharma - Date published: 300 B.C.

Originally written in Sanskrit, “ The Panchatantra ” is a collection of fables and folklore that gives instruction on how to live. While the book itself is an important piece of Indian literature, it’s also representative of an entire genre of folklore, fairy tales, and fables that began to be transcribed around this time. Eventually, these types of stories went on to be the foundation for today’s fantasy genre.

- Author: Virgil - Date published: 19 B.C.

Another epic poem originally written in Latin, “ The Aeneid ” tells the story of Aeneas and includes legend of the founding of Rome. This tale from 19 B.C. is one of the earliest known examples of historical fiction.

Metamorphoses

- Author: Ovid - Date published: 8 A.D.

No list of monumental novels would be complete without Ovid’s “ Metamorphoses ,” a masterpiece of ancient literature. A narrative poem, the book chronicles the history of the world, tying together all existing myths and histories from the beginning of the world up through the rule of Julius Caesar. It is thought to have inspired later literary greats like William Shakespeare, Dante Alighieri, and Salman Rushdie.

The Satyricon

- Author: Petronius - Date published: 66

“ The Satyricon ” is a satiric mock epic about an impotent man’s quest to regain virility. It built on the satire established by the Roman writers who first introduced it. Similar in tone to books by authors like David Sedaris, the hilarious, tongue-in-cheek tale surely inspired other famous comic writers in the millennia since.

Daphnis and Chloe

- Author: Longus - Date published: 150

One of few surviving examples of an ancient Greek novel, “ Daphnis and Chloe ” is Longus’s only known work. A pastoral romance, the book follows two young orphans, a shepherdess, and a goatherd as they attempt to figure out how to consummate their love. The work has inspired dozens of artists since, including Shakespeare, Henry Fielding, and Maurice Ravel.

The Golden Ass

- Author: Apuleius - Date published: 158

“ The Golden Ass ” is the only novel written in Latin that has survived in its entirety. A story of magic and romance, it follows a young man who attempts to turn himself into a bird but ends up as a donkey instead. By turns bawdy, sweet, and fantastic, this early novel will hold your attention from beginning to end.

- Author: Anonymous - Date published: 900

Jumping ahead several hundred years, we come to “ Beowulf ,” an Anglo-Saxon epic poem. Written in Old English, the story follows the titular hero as he fights a monster, the monster’s mother, and a dragon, eventually becoming the king of modern-day Scotland. The book is similar to books like “Le Morte d’Arthur” and “The Once and Future King” in that it mixes fantasy with history.

The Tale of Genji

- Author: Murasaki Shikibu - Date published: 1008

Widely considered the world’s first novel, “ The Tale of Genji ” is a look at courtly life in Japan’s Heian period. The book is also significant in that it was written by a woman, Murasaki Shikibu, who worked as a lady-in-waiting at the imperial court. While the original manuscript, written in an archaic form of Japanese, no longer exists, scholars have around 300 others from the same time period.

The Song of the Cid

- Author: Anonymous - Date published: 1140

One of the earliest pieces of Spanish literature, “ The Song of the Cid ” is an epic based on real-life events that tells the tale of a Castilian hero who works to liberate his beloved Spain from its Moorish captors. The novel is significant in that it brought Islamic and Spanish literature to the world stage.

The Arabian Nights

- Author: Anonymous - Date published: 1315

Some scholars consider “ The Arabian Nights ” to be the greatest Arabic, Islamic, and Middle Eastern contribution to world literature. The novel is a collection of short stories (mainly fables and folklore) tied together by a framing device. The tales included in this work have shaped thousands of novels and Hollywood productions and continue to act collectively as a “ monument to the ageless art of storytelling ,” according to Arab culture specialist Dr. Muhannad Salhi.

The Divine Comedy

- Author: Dante Alighieri - Date published: 1320

When discussing Dante Alighieri’s “ Divine Comedy ,” the BBC called it “Western literature’s very own theory of everything.” A massively important piece of world literature, the nearly 1,000-page tome is an Italian poem from the Middle Ages about a man’s journey through hell, purgatory, and heaven in pursuit of his great love.

The Outlaws of the Marsh

- Author: Shi Nai’an - Date published: 1370

“ Outlaws of the Marsh ” is the first of China’s four great classical novels, works whose stories have permeated the country’s culture so thoroughly that citizens of all ages are familiar with them. Set during the Song Dynasty, it tells the story of 108 men and women forced into the hills by feudal governments who band together to form an army, are granted amnesty, and then fight for their country against various foes.

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

- Author: Unknown - Date published: 1397

Written by an unknown poet, “ Sir Gawain and the Green Knight ” is considered on par with Chaucer’s works and “Beowulf” in both content and form. One of the best-known Arthurian tales, the story follows a Knight of the Round Table who accepts a challenge from a mysterious knight, undertaking a year-long quest and entering into a chivalrous romance along the way. Famed fantasy writer J.R.R. Tolkien is a known fan of the novel.

The Canterbury Tales

- Author: Geoffrey Chaucer - Date published: 1400

There are over 90 manuscripts of Chaucer’s “ The Canterbury Tales ” from the 1400s that still exist, a testament to its enormous popularity in its time. Written in medieval English, the book follows a group of 31 pilgrims as they make their way from Tabard Inn to Canterbury Cathedral. In order to pass the time, the members of this fictional group agree to tell two tales each on the way out and two tales each on the way back. While the work was never finished, it remains hugely influential in pop culture today.

- Author: Thomas More - Date published: 1516

An early example of sociopolitical satirical fiction, Thomas More’s “ Utopia ” is the story of a fictional island’s various customs. Written in Latin, the book is seen by modern scholars as an example of utopian/dystopian science fiction and certainly must have influenced modern works like “The Handmaid’s Tale” or “The Hunger Games.”

Romance of the Three Kingdoms

- Author: Luo Guanzhong - Date published: 1522

Set toward the end of the Han Dynasty, “ Romance of the Three Kingdoms ” is another of China’s four great classical novels. A mix of real history, legend, and myth, the book has hundreds of characters but primarily follows three feudal lords as they attempt to replace and restore the crumbling dynasty. The most well-known section follows Liu Pei and his sworn brothers Chang Fei, a giant, and Kuan Yu, an invincible knight, who are aided by a wizard named Chuko Liang and fight for control over the Han throne.

The Life of Lazarillo de Tormes and of His Fortunes and Adversities

- Author: Anonymous - Date published: 1554

The crown jewel of the Spanish Golden Age, “ The Life of Lazarillo de Tormes and His Fortunes and Adversities ” is an example of a picaresque novel or one that follows the adventures of a lovable, low-class hero who relies on his wits and “street knowledge” to get by. For centuries scholars have worked to determine the author of the novel, but haven’t been able to come to a conclusive decision.

The Faerie Queene

- Author: Edmund Spenser - Date published: 1590

The first epic written in English, “ The Faerie Queene ” went on to inspire some of the world’s most famous poets and novelists like John Milton and Alfred Tennyson. Edmund Spenser’s allegorical work tells the story of several knights who are representative of different virtues, and the work as a whole is meant to glorify Queen Elizabeth I.

Monkey: The Journey to the West

- Author: Wu Cheng’en - Date published: 1592

The third of China’s four great classical novels, “ The Journey to the West ” is considered by some to be the most popular novel of all time in East Asia. (The addition of "Monkey" to the title comes from the definitive English translation.) Another picaresque novel, this book follows a monk as he journeys to the western regions of Asia in order to collect sacred texts, receiving help from spirits and gods, and fighting monsters and ogres along the way.

Don Quixote

- Author: Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra - Date published: 1605

Clocking in at over 1,000 pages, “ Don Quixote ” is considered by many to be the first modern novel . Published in 1605, the book is about a nobleman, Alonso Quijano, who is obsessed with chivalric romances and decides to become a knight errant himself. Unfortunately for the newly knighted Don Quixote de la Mancha, the world no longer has any use for medieval knights. Sancho Panza, the intelligent squire in "Don Quixote," established the enduring "sidekick" character.

Paradise Lost

- Author: John Milton - Date published: 1667

An epic work in both scale and ambition, John Milton’s “ Paradise Lost ” is one of the greatest novels-in-verse ever written in the English language. It tells the story of the biblical fall of man as it happened, taking place in heaven, hell, and on Earth.

The Pilgrim’s Progress

- Author: John Bunyan - Date published: 1678

At one point in history, Christianity and culture were so intertwined that almost every popular work had heavy religious influences. “ The Pilgrim’s Progress ” is a perfect example of this. Enormously influential in its time, the allegorical tale follows a man’s journey through life as he searches for salvation. Even today, John Bunyan’s book remains one of the most widely read books written in English.

Robinson Crusoe

- Author: Daniel Defoe - Date published: 1719

When Daniel Defoe’s “ Robinson Crusoe ” was first published, it listed Crusoe himself as the author , leading many to believe that it was a real-life travelogue and not a fictitious adventure tale. To this day, many critics point to the book, which covers 30 years of a castaway’s life on a deserted island, as the beginning of realistic fiction.

Gulliver’s Travels

- Author: Jonathan Swift - Date published: 1726

Where Daniel Defoe set out to write a realistic travelogue, Johnathan Swift set out to satirize the popular genre. Fans both past and present love the tale about a wayfaring seaman who finds himself in far-flung foreign lands like Lilliput and Laputa. Immensely popular when it was first released, “ Gulliver’s Travels ” sold out its initial print run in a matter of days.

- Author: Voltaire - Date published: 1759

Voltaire’s most celebrated work, “ Candide ” is, on its surface, the tale of a gentleman who embarks on grand and romantic adventures all around the world while constantly being battered by fate. On a deeper level, the story is an attack on the philosophical idea that “all is for the best” and that we live in the “best of all possible worlds.”

Dream of the Red Chamber

- Author: Xueqin Cao - Date published: 1791

The last of China’s four great classical novels, “ Dream of the Red Chamber ” has an entire field of scholarship called “Redology” devoted to it. Generally regarded as the greatest novel to ever come out of China , the book is one part romance, one part history of one of the world’s greatest nations, and one part family history. The full work spans three lengthy volumes, but the heart of the story has been edited down into a single book for modern readers.

Pride and Prejudice

- Author: Jane Austen - Date published: 1813

An immediate success upon publication, “ Pride and Prejudice ” remains one of the most read English language novels in the world. Jane Austen’s classic love story has inspired hundreds of other novels, movies, and TV shows, and her romantic leads, the opinionated Elizabeth and proud Mr. Darcy, are some of the most dazzling and recognizable characters ever written.

Frankenstein

- Author: Mary Wollstonecraft Shelly - Date published: 1818

Many literary scholars see Mary Wollstonecraft Shelly’s “ Frankenstein ” as the the first science-fiction story ever written. The gothic horror novel tells the story of a young scientist, Victor Frankenstein, who creates a sapient creature in his lab and then unleashes him on the world. It would be hard to overstate its influence on modern pop culture.

- Author: Nikolai Gogol - Date published: 1842

Although scholars and readers constantly debate what Gogol was attempting to do with “ Dead Souls ,” there’s no debating its importance in the canon of Russian literature. The novel, which ends in the middle of a sentence, follows a middle-class man, Pavel Ivanovich Chichikov, as he wanders around the motherland collecting the names of dead serfs while encountering dozens of other middle-class people. While the book certainly won’t appeal to everyone, it provides an excellent picture of Russia during the 19th century.

The Three Musketeers

- Author: Alexandre Dumas - Date published: 1844

“ The Three Musketeers ” is considered by some to be the most famous historical novel of all time. Alexandre Dumas’s most celebrated work is actually about four swordsmen (D’Artagnan, Athos, Porthos, and Aramis) whose bond of friendship carries them through many an adventure, battle, and romance relatively unharmed.

- Author: Charlotte Bronte - Date published: 1847

Literary critic Daniel S. Burt has called Charlotte Bronte “the first historian of the private consciousness” thanks to her novel “ Jane Eyre ,” the first to focus on a lead character’s moral and spiritual development. Well ahead of its time, this romantic novel follows the titular Jane Eyre through a rough childhood, as a student and teacher at a school, and then—in what readers remember best about the novel—as she accepts a job as governess and slowly begins to fall for her mysterious employer, Mr. Rochester.

Wuthering Heights

- Author: Emily Bronte - Date published: 1847

Charlotte Bronte’s younger sister Emily wrote “ Wuthering Heights ,” a classic example of a gothic novel. The book, about the ill-fated love between Heathcliff and Catherine, contains elements of the supernatural, a host of scandals, and more than one love triangle.

The Scarlet Letter

- Author: Nathaniel Hawthorne - Date published: 1850

Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “ The Scarlet Letter ” is significant for two reasons. It is the first novel to draw from the puritan roots of the United States, taking a good hard look at the negative effects our country’s rigid morality can have on individual lives. It is also one of the few examples of a novel influenced by the transcendentalist movement , which had a huge impact on modern American philosophy.

- Author: Herman Melville - Date published: 1851

Widely regarded as one of the “greatest works of imagination” in American literary history, per Goodreads, “ Moby-Dick ” is, at its heart, a meditation on America. On the surface, however, the book is an action-packed tale of a madman’s pursuit of an unknowable sea creature.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

- Author: Harriet Beecher Stowe - Date published: 1851

In the same way “Moby-Dick” is imaginative, “ Uncle Tom’s Cabin ” is unflinchingly based in reality. Scandalous in its time for its antislavery sentiments, the book has more than earned its place in American literary history. Abraham Lincoln credited the story, which was written by a white housewife morally opposed to slavery, with igniting the flame that became the Civil War .

Madame Bovary

- Author: Gustave Flaubert - Date published: 1857

A story about a bored wife’s affairs and romantic fantasies, “ Madame Bovary ” was so scandalous at the time of its publication that it caused a public outcry and wound up banned in multiple countries. With a complicated main character who is self-obsessed and morally corrupt, many readers feel that Flaubert’s central message was one of finding happiness and fulfillment with what life hands you, rather than always searching for greener grass somewhere else.

A Tale of Two Cities

- Author: Charles Dickens - Date published: 1859

No such list would be complete without an entry from Charles Dickens, who is often considered the best writer of the Victorian era. In “ A Tale of Two Cities ,” Dickens spins a story of political prisoners, reunited families, romantic love, and the events that lead up to the French Revolution. The book is one of the best-selling novels of all time.

Les Miserables

- Author: Victor Hugo - Date published: 1862

Another novel set in the midst of the French Revolution, “ Les Miserables ” made the radical move of featuring a working-class hero. A story of love and redemption, Victor Hugo’s famous work is, in simplistic terms, a cat-and-mouse tale featuring Jean Valjean, an altruistic ex-convict, and Inspector Javert, a policeman focused more on retribution than justice. Incredibly layered and nuanced, the 1,300-page novel rewards those who manage to read the whole thing.

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

- Author: Lewis Carroll - Date published: 1865

Ever since the first publication of Lewis Carroll’s “ Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland ” in 1865, the fantasy tale about a girl who falls into a subterranean world has never been out of print. Considered one of the best examples of literary nonsense fiction, the book has had an enormous impact on our culture and on more recent fantasy tales.

War and Peace

- Author: Leo Tolstoy - Date published: 1867

“ War and Peace ” is an epic saga that chronicles Napoleon’s invasion of czarist Russia and the multitude of ways it affected life for the average citizen. Arguably Leo Tolstoy’s best work, the novel is a world classic.

Little Women

- Author: Louisa May Alcott - Date published: 1868

Another author who was heavily influenced by the transcendentalist movement in America is Louisa May Alcott. Her book “ Little Women ,” about four sisters during the Civil War era, is far too often classified as girls’ or women’s literature. But the novel’s much deeper themes of family duty, death, gender roles, and personal ambition have value for all readers.

The Brothers Karamazov

- Author: Fyodor Dostoyevsky - Date published: 1879

No other book on our list has earned as much international acclaim as “ The Brothers Karamazov .” The Russian novel earned this praise thanks to the way it tackles tough topics like the existence of God, free will, faith, doubt, reason, and morality. A story of a murder within a family, the epic was author Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s last work.

The Seven Heroes and Five Gallants

- Author: Shi Yukun - Date published: 1879

Another well-known piece of Chinese literature, “ The Seven Heroes and Five Gallants ” follows a Robin Hood-esque character named Lord Bao and the men who make up his court as they fight crime and corruption all over China. An absorbing tale, the book also gives international audiences a look at how influential Confucian philosophies were in the country.

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

- Author: Mark Twain - Date published: 1884

“ The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn ” is a direct sequel to Mark Twain’s other famous work, “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer.” The novel follows the titular Huckleberry Finn, a boy who runs away from his small town with Jim, an enslaved boy who escapes his enslavers. The two go on a series of wild adventures on the Mississippi River. The novel is notable not just for its commentary on racism in America , but also for being the first book to use vernacular English throughout.

The Picture of Dorian Gray

- Author: Oscar Wilde - Date published: 1890

A study of man’s vanity, cruelty, selfishness, and hedonistic impulses, “ The Picture of Dorian Gray ” was considered so immoral when it was first published that it was heavily censored. The only novel ever written by Oscar Wilde, the book is about a young man who essentially sells his soul to the devil in order to obtain eternal youth. Although the story is incredibly dark, the slim novel is easily readable and accessible for modern-day audiences.

- Author: Bram Stoker - Date published: 1897

“ Dracula ” is a gothic horror novel about the vampire Count Dracula, who attempts to leave his native Transylvania in search of fresh blood and new victims. A genuinely chilling read, the book is notable not just for its own content but for the various ways it has shaped fantasy literature and the thousands of vampire stories it inspired.

Heart of Darkness

- Author: Joseph Conrad - Date published: 1899

The final 19th-century book on our list, “ Heart of Darkness ” is about a ferryboat captain’s obsession with an ivory trader and his suspicion that this trader is not a genius like everyone believes—but insane. At its core, the book is an argument that there is very little separating the "savage" (the protagonist’s racist conception of Black men) from civilized people—at heart, we’re really all the same. "Heart of Darkness" has inspired numerous adaptations, the most well-known probably being Francis Ford Coppola's "Apocalypse Now."

- Author: Upton Sinclair - Date published: 1905

Upton Sinclair’s “ The Jungle ” is about the tragic lives of an immigrant family in Chicago. Although Sinclair intended the book to reveal how horrifically immigrants were being exploited and how desperately he thought the country needed to turn to socialism, many readers walked away more focused on the unsanitary practices of the meat industry that he exposed. In this area, the novel did lead to an abundance of reforms and changes, including the Meat Inspection Act .

The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man

- Author: James Weldon Johnson - Date published: 1912

When “ The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man ” was first published, it was attributed to an anonymous author, as publishers weren’t sure how its unflinching examination of race in America was going to be received. The emotional novel follows a Black man who “passes” for white as he journeys from the rural South to the exclusive suburbs of the Northeast. Wildly successful, the book inspired a generation of Black authors and many Harlem Renaissance works.

Swann’s Way

- Author: Marcel Proust - Date published: 1913

“ Swann’s Way ” is the first volume in Marcel Proust’s “In Search of Lost Time,” which fictionalizes his youth in Belle Epoque France. Described as a “ perfect rendering of life in art ,” the book deals with the themes of childhood, involuntary memory, and the meaning of an individual life.

The Mysterious Affair at Styles

- Author: Agatha Christie - Date published: 1920

“ The Mysterious Affair at Styles ” was Agatha Christie’s debut novel. While the book, which sees Christie’s most beloved character Hercule Poirot solve a murder, may not be regarded as her best work, it still is worthy of inclusion as it started her on the path toward becoming the best-selling fiction author of all time.

- Author: Hermann Hesse - Date published: 1922

Written in German, “ Siddhartha ” is about a wealthy Indian man who leaves his charmed life behind in order to find spiritual fulfillment and meaning. A mix of various religious philosophies and cultures, the book didn’t become popular in the United States until the '50s and '60s, when it had a major influence on the counterculture generation.

- Author: James Joyce - Date published: 1922

A modernist masterpiece, “ Ulysses ” is about a single day in the life of a Dubliner named Leopold Bloom, alongside a host of his friends and acquaintances. Written in a stream of consciousness, nothing really notable happens in the book, leading many readers to give up far short of the 700-plus-page end. Still, the book is a major achievement in 20th-century literature thanks to its experimental narrative techniques and subtle humor.

The Magic Mountain

- Author: Thomas Mann - Date published: 1924

Hugely influential in German literary history, “ Magic Mountain ” is another novel that doesn’t have any real central plot. In fact, scholars and readers have debated for years over what this book is about, other than the destructiveness and cynical attitudes of civilization.

Mrs. Dalloway

- Author: Virginia Woolf - Date published: 1925

“ Mrs. Dalloway ” covers a single day in the titular character’s life as she prepares for a party. Going about her errands and chores, Mrs. Dalloway reflects on the choices that led her to this particular moment and wonders about what the future will hold. Virginia Woolf’s famous work is significant because it demonstrates that novels don’t only have to be about extraordinary adventures, but can be about everyday life, as well.

The Great Gatsby

- Author: F. Scott Fitzgerald - Date published: 1925

A standard of the Jazz Age, “ The Great Gatsby ” perfectly embodies many of the values of its time, like personal freedom and the unapologetic pursuit of pleasure. Most folks, whether avid readers or not, are at least somewhat familiar with the story of the fabulously rich Jay Gatsby, who’s in love with the unattainable Daisy Buchanan and throws massive parties at his Long Island mansion in the hopes of earning her affections.

Home to Harlem

- Author: Claude McKay - Date published: 1928

The author of “ Home to Harlem ,” Claude McKay, was a central figure in the Harlem Renaissance. His most famous work follows two men from very different circumstances as they move through Harlem’s intense nighttime scene and navigate race in America by day.

- Author: Virginia Woolf - Date published: 1928

Another monumental novel by Virginia Woolf, “ Orlando ” has long been a classic in the LGBTQ+ community. Taking place over three centuries, the book follows its central character as a mysterious change transforms him from a man to a woman, and the subsequent ways her place in the world changes. Often studied by feminist, gender, and transgender students, the book has been adapted into several movies, plays, and even an opera.

All Quiet on the Western Front

- Author: Erich Maria Remarque - Date published: 1929

Although it’s fiction, “ All Quiet on the Western Front ” gives readers an all-too-real look at World War I. Written by a German veteran, the novel paints a vivid picture of the social and emotional stress felt by the soldiers, as well as the difficulty for many of them to readjust to civilian life after the fighting was over. During WWII, the heavy book was among those burned en masse by the Nazis.

- Author: Nella Larsen - Date published: 1929

Written by one of the most preeminent female writers of the Harlem Renaissance, “ Passing ” was an instant success upon publication in 1929. The story of two former childhood friends and their renewed fascination with each other’s lives, the book makes important points about Americans’ understanding of race and gender.

A Farewell to Arms

- Author: Ernest Hemingway - Date published: 1929

“ A Farewell to Arms ” was Ernest Hemingway’s first best-seller and America’s most important WWI novel. The semi-autobiographical book follows an ambulance driver who falls in love with an Italian nurse despite the horrors surrounding both of them. The novel was so important to Hemingway that he reportedly rewrote the ending almost 40 times in order to get the words exactly right.

The Sound and the Fury

- Author: William Faulkner - Date published: 1929

Set in Jefferson, Missouri, “ The Sound and the Fury ” centers on the Compson family, former Southern aristocrats and some of the most memorable characters in American literature. Separated into four sections, each piece of the book is told from the perspective of a different family member and in a different narrative style. The book’s success in the '30s certainly played a role in William Faulkner eventually winning the Nobel Prize in Literature.

The Good Earth

- Author: Pearl S. Buck - Date published: 1931

Written by the daughter of two missionaries in China, “ The Good Earth ” is about life in agrarian China and pits the humble and goodhearted Wang Lung against the greedy, noble House of Hwang. The book may feel slowly paced to a modern reader, but for 1930s audiences it was impactful enough to encourage them to consider the Chinese as allies in the impending WWII.

Brave New World

- Author: Aldous Huxley - Date published: 1932

Although “ Brave New World ” was published 90 years ago, it is incredibly relevant to the current moment and the world we live in. A dystopian novel, Aldous Huxley imagines a future World State where citizens are placed in a hierarchy based on their (genetically modified) intelligence and the entire culture is conditioned to follow the government blindly. The book acts as a warning against state control, consumerism, and the lack of individuality.

Their Eyes Were Watching God

- Author: Zora Neale Hurston - Date published: 1937

Initially ill-received, Zora Neale Hurston’s “ Their Eyes Were Watching God ” has become a classic in Black and feminist literature in the intervening years. The book follows a young Black woman in the '30s who’s desperately searching for her own identity through three marriages and a physical journey back to her roots.

The Grapes of Wrath

- Author: John Steinbeck - Date published: 1939

This Great Depression novel both won the Pulitzer Prize and was publicly banned the year it was published. “ The Grapes of Wrath ” follows the Joad family as they’re pushed off their Oklahoma farm by effects of the Dust Bowl and travel by car across the country to California, “the promised land.” The powerful drama underscores the vast gap between the haves and the have-nots in this country.

The Stranger

- Author: Albert Camus - Date published: 1942

“ The Stranger ” is a story of a senseless murder. It’s also a close look at the philosophies of existentialism and the absurd. Readers of this short and simple work either identify with the main character’s completely indifferent outlook on life—or hate it.

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn

- Author: Betty Smith - Date published: 1943

“ A Tree Grows in Brooklyn ” is a coming-of-age tale featuring a young woman raised in a tenement in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, at the start of the 20th century. Emotional, honest, and at times downright hilarious, the book reminds readers that all one really needs to get through life is a tenacious attitude and a strong sense of self.

Cry, the Beloved Country

- Author: Alan Paton - Date published: 1948

The most important novel to come out of South Africa’s apartheid era, “ Cry, the Beloved Country ” is about a Black man’s life in a Black country under white man’s rule. It follows a Zulu pastor, Stephen Kumalo, and his son, Absalom, as they do their best to navigate life in a country that’s torn apart by racial injustice.

- Author: George Orwell - Date published: 1949

Often paired with “A Brave New World,” “ 1984 ” is another dystopian novel that’s very relevant to today’s world. Often assigned reading for high school students, George Orwell imagines life in a totalitarian state where every move is watched by the Thought Police. When one man becomes disillusioned with the state and attempts to change things, the consequences are swift and heavy.

Invisible Man

- Author: Ralph Ellison - Date published: 1952

Narrated by a nameless character, “ Invisible Man ” examines the multitude of obstacles Black men face in America. Taking place in the Deep South, the streets of Harlem, Communist rallies, and underground “battle royals,” the book won the National Book Award for fiction in 1953.

The Fellowship of the Ring

- Author: J.R.R. Tolkien - Date published: 1954

While the content of “ The Fellowship of the Ring ” may not be as heavy as the subject matter of many of the other books on this list, J.R.R. Tolkien’s novel still earns its spot for its impact on fantasy literature. For the uninitiated, the book, which is the first in a trilogy, follows a band of adventurers as they set out across Middle Earth to destroy a ring of great, dark power. Tolkien established many of the fantasy tropes used by subsequent authors.

Giovanni’s Room

- Author: James Baldwin - Date published: 1956

Another classic of LGBTQ+ literature, “ Giovanni’s Room ” is about an American living in Paris who’s engaged to a woman and involved in a homosexual affair with an Italian bartender. Masterfully written, the book focuses on the inner turmoil of a person caught between the life society tells him he should live and the life he sees for himself. James Baldwin’s controversial work is credited with opening the door for a wider conversation about homosexuality and bisexuality.

Atlas Shrugged

- Author: Ayn Rand - Date published: 1957

Ayn Rand herself considered “ Atlas Shrugged ” to be her magnum opus. In the book, Rand fleshes out her philosophy of objectivism through a dystopian story where private business owners are increasingly put upon by the government and decide to leave everything behind to begin their own capitalist society. While not widely beloved at first, the book has demonstrated great staying power and is still read all over the world to this day.

Things Fall Apart

- Author: Chinua Achebe - Date published: 1958

One of the first African novels to achieve international acclaim, “ Things Fall Apart ” is about life in pre-colonial Nigeria as told through the eyes of a “strong man” named Okonkwo. Often compared to Greek and Roman tragedies, the book examines how clan and village life was negatively affected by the arrival of European colonizers and Christian missionaries.

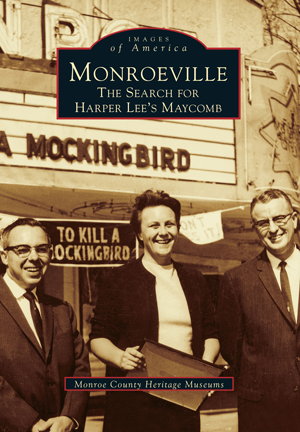

To Kill a Mockingbird

- Author: Harper Lee - Date published: 1960

“ To Kill a Mockingbird ” is set in a small Southern town and is at once a story of childhood and one of a place rocked by a crisis of conscience. While modern attitudes surrounding the book have shifted slightly, with many pointing to the “white savior” complex written into lawyer Atticus Finch, there’s no denying how big an impact this American classic had toward racist attitudes in the '60s. The impact was so big that it earned reclusive author Harper Lee the Pulitzer Prize the following year.

Samskara: A Rite for a Dead Man

- Author: U.R. Ananthamurthy - Date published: 1965

“ Samskara: A Rite for a Dead Man ” begins with the death of Naranappa, a renegade Brahmin who has flouted the Hindu rules of purity for years. As his village argues about whether or not his body should be given a proper burial, they are forced to reckon with the questions of God, religion, and rebirth.

Season of Migration to the North

- Author: Tayeb Salih - Date published: 1966

One of the most impactful novels in Arabic literature, “ Season of Migration to the North ” is concerned with the impact of Western colonialism on rural African societies, particularly in Sudan. This is the story of two men who return to their native Sudan after jaunts in Europe, one turned into a monster by the clash of cultures, the other doing his best to hold both parts of his identity together despite their obvious dissonance. The book itself is considered a turning point in postcolonial narratives.

One Hundred Years of Solitude

- Author: Gabriel Garcia Marquez - Date published: 1967

Columbian author Gabriel Garcia Marquez published his magical-realism masterpiece “ One Hundred Years of Solitude ” in 1967. The book follows several generations of the Buendia family, whose patriarch founded the fictional town of Macondo. It deals with themes like solitude, the repetition of history, the fluidity of time, and elitism.

Slaughterhouse-Five

- Author: Kurt Vonnegut Jr. - Date published: 1969

The science-fiction, antiwar novel “ Slaughterhouse-Five ” follows Billy Pilgrim through WWII as he survives a bombing, spends time in a prisoner-of-war camp, readjusts to civilian life, and occasionally time-travels. The novel has been subject to many banning and censorship campaigns thanks to its frank tone and often vulgar content.

Gravity’s Rainbow

- Author: Thomas Pynchon - Date published: 1973

A postmodern epic, “ Gravity’s Rainbow ” is to the second half of the 20th century what “Ulysses” was to the first half. Set in Europe post-WWII, the book primarily focuses on the program responsible for Germany’s V-2 rockets and the mysterious inclusion of a “black device” in one of these rockets. Although it won the National Book Award, Thomas Pynchon refused to accept or even acknowledge the victory .

Petals of Blood

- Author: Ngugi wa Thiong’o - Date published: 1977

On the surface, “ Petals of Blood ” is about the investigation of a triple murder in Kenya. However, a deeper read reveals that the book is actually speaking about the Mau Mau Rebellion and a people who are disillusioned with leadership that has failed to pull their country out of its “developing nation” status. The book made such an impact upon publication that its author, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, was jailed without charges—an incident that ignited protests around the world.

Midnight’s Children

- Author: Salman Rushdie - Date published: 1981

“ Midnight’s Children ” is essentially about India’s independence from colonialism and the partition of the country. Told through the eyes of one of the 1,001 children born at midnight on its independence day, the book examines what it means to be a master and a victim of a certain point in history. Massively popular in both the U.K. and the United States, the novel has won a host of international awards.

The Color Purple

- Author: Alice Walker - Date published: 1982

An epistolary novel, “ The Color Purple ” is a collection of letters written between sisters in rural Georgia during the early 20th century. A touchstone of Black American literature, the book was one of the first to break the silence on domestic and sexual abuse and violence. Because of that content, the book is often challenged and has even been banned at certain points.

The Handmaid’s Tale

- Author: Margaret Atwood - Date published: 1985

Over the past several years, Margaret Atwood’s “ The Handmaid’s Tale ” has benefited from renewed popularity, largely thanks to the release of the Hulu TV series based on the novel. Margaret Atwood's dystopian novel imagines a totalitarian state where women are property and their bodies tools used merely to advance the agenda and power of the state, the Republic of Gilead. A scathing, satirical warning, the book is a cornerstone of feminist literature.

- Author: Toni Morrison - Date published: 1987

Set just after the Civil War, “ Beloved ” was inspired by a real-life woman, Margaret Garner. It’s a story of a former enslaved woman who can’t beat back her memories of the past or its influence over her, no matter how hard she tries. Toni Morrison’s most acclaimed work, the novel is currently banned in some U.S. public schools thanks to its racial and sexual content.

The Alchemist

- Author: Paulo Coelho - Date published: 1988

“ The Alchemist ” holds the distinction of being one of the most translated books of all time, currently available to read in 67 languages . The enchanting and lyrical tale follows a shepherd boy as he travels from his native Spain to Egypt in search of an elusive treasure. Along the way, he learns invaluable lessons about life and the worth we all have inside ourselves.

The Remains of the Day

- Author: Kazuo Ishiguro - Date published: 1989

“ The Remains of the Day ” is a slow-paced novel filled with the musings of a butler near the end of his career. Stevens, devoted to a life of service, has missed out on several opportunities, including a possible romance with a former housekeeper. Nearing the end of his professional life, he begins to realize that the loyalty he’s shown to his work and master may have been misplaced. The novel won the Man Booker Prize the year of its release.

Like Water for Chocolate

- Author: Laura Esquivel - Date published: 1989

Mexican author Laura Esquivel’s “ Like Water for Chocolate ” was a #1 best-seller in her native country and in the United States for two years after its publication. It’s the story of a young Mexican woman, Tita, who is forbidden from marrying her lover, Pedro, and must care for her ailing mother instead. A tragic, heart-wrenching story, the book includes elements of magical realism similar to Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s work.

The Things They Carried

- Author: Tim O’Brien - Date published: 1990

A collection of linked fictional episodes, “ The Things They Carried ” follows a platoon of American soldiers through the Vietnam War and after returning home. A veteran himself, O’Brien makes every attempt to steer clear of the politicization of the war, but his work ensures that everyone back home understands what it was really like out there in the jungles.

- Author: Toni Morrison - Date published: 1992

While the content of Toni Morrison’s work always stands apart from her contemporaries, with “ Jazz ” it’s really the style of the novel that makes it such a must-read. Set in Harlem in the 1920s, the book mimics Jazz music, with individual characters “improvising” solo sections of the book, often in a “call and response” format, which all come together to create a melodic whole.

Stone Butch Blues

- Author: Leslie Feinberg - Date published: 1993

“ Stone Butch Blues ” was once an underground classic, but over the past decade it has become a much more widely read hit. The book follows Jess Goldberg, a masculine girl growing up in Upstate New York during the '50s and '60s and coming to terms with her own identity as a lesbian. Set in a pre-Stonewall world, when social pressures and politics kept many from living as their true selves, the book packs a powerful message about identity and acceptance.

The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle

- Author: Haruki Murakami - Date published: 1994

Haruki Murakami’s “ The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle ” is best described as sci-fi meets magical realism. The book follows a Japanese man who goes in search of his wife and her cat, both of whom have disappeared under mysterious circumstances. His search takes him into the netherworld and reveals long-buried secrets about WWII.

Infinite Jest

- Author: David Foster Wallace - Date published: 1996

Cataloged as an “encyclopedic” novel, “ Infinite Jest ” stands out for both its content and its form. Set in a tennis academy and a halfway house in a future mutation of our world, the novel follows one of the most messed-up families to appear in modern literature, a group of political radicals, a group of recovering addicts, and a group of elite tennis players. Throughout its 1,088 pages, it also experiments with endnotes, racking up nearly 400 in total by the end of the book. While a literary best-seller, the book is hardly for the faint of heart (or attention span).

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone

- Author: J.K. Rowling - Date published: 1997

While it remains to be seen whether or not “ Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone ” will stand the test of time, the effect the book has had on literature as a whole is indisputable. The tale about a boy wizard launched a series that would go on to sell more than 450 million copies , be translated into 67 languages, and make J.K. Rowling the first billionaire author.

The Kite Runner

- Author: Khaled Hosseini - Date published: 2003

“ The Kite Runner ” is set in Afghanistan during the fall of the country’s monarchy, the Soviet-Afghan War, and the rise of the Taliban. The story of fathers and sons, friendship, redemption, and reading, the book primarily follows Amir and Hassan, childhood friends torn apart by a horrific act. The novel spent over two years on the New York Times Best Seller list.

- Author: Betool Khedairi - Date published: 2004

Partly a coming-of-age novel, “ Absent ” follows a teenage girl, Dalal, who lives with her uncle and aunt in a Baghdad apartment as she undertakes real responsibility for the first time and begins to fall in love. The book is also an examination of life under restrictions and amid unthinkable violence, as well as the power of the human spirit.

Trending Now

50 best colleges on the east coast.

50 most meaningful jobs in America

30 best nature documentaries of all time

60 historic photos from American military history

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- The ALH Review

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Submit?

- About American Literary History

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

– Support for our author and subscriber community

Professor Gordon Hutner

About the journal

Covering the study of US literature from its origins through the present, American Literary History provides a much-needed forum for the various, often competing voices of contemporary literary inquiry …

The ALH Review

The ALH Review is a source for in-depth reviews assessing the significance of new books for specialists in American literary history. The Review engages new scholarly and critical studies by deliberating on important shifts and advances in various sub-fields, and exploring major developments in research.

Read now

The ALH Forum is a new, free to read, online feature of American Literary History.

Check out the latest entry, Abolition's Afterlives , a collection of essays that considers the ongoing legacy of nineteenth-century abolitionism.

What American literature can teach us about human rights

Explore the latest blog post from American Literary History featured on the OUPblog. Author of the article, The Ends of Human Rights in US Literary Studies , Brian Goodman discusses american literature and the future terrain of human rights.

Latest articles

Latest posts on x.

Email alerts

Never miss out on the latest content from ALH. Register to receive email alerts as soon as new issues of American Literary History are published online.

Recommend to your library

Fill out our simple online form to recommend American Literary History to your library.

Recommend now

The journal features essay-reviews, commentaries, and critical exchanges. It welcomes articles on historical and theoretical problems as well as writers and works. Submit to ALH .

Related Titles

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1468-4365

- Print ISSN 0896-7148

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Places on our 2024 summer school are filling fast. Don’t miss out. Enrol now to avoid disappointment

- 12 Great Books to Read to Understand Periods in Literature

English literature has a long and illustrious history that has spawned some of the world’s most famous writers, novels, plays and poems.

You should also read…

- A Guide to Britain’s Most Famous Writers

- 12 Essential English Novels Everyone Should Read

That history can be broken down into a number of distinct literary eras, in each of which a set of characteristics or beliefs shaped the works of literature produced. Sometimes the best way of understanding different periods of literary history is to read the works that each period produced. It’s often hard to narrow down the wealth of literature springing from each era of literature to just one or two exemplary texts, but this article seeks to give you a beginner’s guide to the most prominent periods in English literary history.

Medieval Literature (500 – 1500)

The earliest works of English literature arose from the writing down of tales that had probably been around for centuries before, surviving via the oral tradition. Medieval literature tends to be split into Old English (658-1100) and Middle English (1100-1500), and these are two of the most prominent works from this period.

English Literature is said to begin with Beowulf , an epic Anglo-Saxon poem by an unknown author, thought to have been penned anywhere between the 8th and 11th centuries. It speaks of Scandinavian kings, mythical beasts and battles, and is extremely important for being the the longest surviving epic poem in Old English.

2. Geoffrey Chaucer – The Canterbury Tales

Later in the medieval period, a civil servant named Geoffrey Chaucer popularised the use of vernacular English, with the writing of his most famous work, The Canterbury Tales . More than twenty individual stories are presented in the context of a story-telling contest that takes place between a group of pilgrims who are en route to Canterbury Cathedral. Thanks to this and other works, Chaucer is often thought of as “the Father of English Literature”.

The Renaissance Era (1500 – 1670)

Stemming from the period of huge cultural advance known as the Renaissance (which began in Italy in the 13th century but took a while to reach England), this period in English literature is dominated by Elizabethan playwrights such as William Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe and John Webster. Other notable writers include Sir Philip Sidney and Edmund Spenser. A key influence in this period was the revival in interest in classical literature, which had a profound influence not only on writing, but on art and philosophy.

3. William Shakespeare – Henry IV Parts 1 and 2

All Shakespeare is worth reading, and will help you get a sense of this period of English literature; but Henry IV, particularly Part I, is noted for being amongst the playwright’s best. Contrasting between serious and funny scenes, between solemn kings and bawdy drinking houses, it’s a superb example of the kind of contrasts Elizabethan audiences would have enjoyed. It also introduces one of Shakespeare’s greatest and most enduringly popular characters: the roguish knight, Sir John Falstaff.

4. Edmund Spenser – The Faerie Queene

A contemporary of Shakespeare, Edmund Spenser was another highly influential Elizabethan poet, who exemplified Elizabethan literature with his defining masterpiece, The Faerie Queene , an allegorical poem written in celebration of the Tudor dynasty and the reign of Elizabeth I. It’s one of the longest poems in the English language, and represents an important development in modern English verse. Her Majesty must have approved: on the strength of this poem, its author was granted a pension for life.

The Restoration (1660 – 1700)

This relatively narrow period of literary history coincides with the end of the Stuart monarchs, and is generally thought of as literature that flourished under the restored court of Charles II. It’s difficult to pin it down to exact dates, though, as literature was in a state of flux during this period, with new genres (such as the laudatory ode) springing up and responding to the political, social and economic state of play at the time; this influenced different literary genres at different times. Poetry is by far the most important genre of this period.

5. John Bunyan – The Pilgrim’s Progress

The allegorical elements of Spenser’s Faerie Queene likely influenced John Bunyan in his writing of The Pilgrim’s Progress , an important religious poem that is an allegorical treatment of Christian life, particularly the idea of personal salvation. Its protagonist, Christian, is an ‘everyman’ character, and the poem is differentiated from similar preceding texts by the simplicity of its style.

6. John Milton – Paradise Lost

More than seventy years after The Faerie Queene brought fame to Edmund Spenser, John Milton brought out another epic poem that would secure his reputation as another of the country’s finest poets. Paradise Lost , more than ten thousand lines in length, tells the Biblical story of the Fall of Man, and it’s an achievement made all the more impressive by the fact that it was dictated in its entirety, Milton having gone blind some years before he wrote it. Though Paradise Lost isn’t archetypal Restoration literature, and Milton is studied separately from other Restoration literature, this is certainly one of the most famous and influential works that sprung from this period.

The Age of Enlightenment (1700 – 1800)

The Age of Enlightenment, sometimes referred to as the Age of Reason, was a cultural movement led by philosophers such as Francis Bacon and René Descartes. It was characterised by a scientific, rational approach to the issues of the day, challenging prevailing beliefs, which had a religious basis. The movement advocated the logical working out of problems, the use of empirical evidence to support beliefs, and the rejection of superstition. Isaac Newton and Mozart are two of the famous names this era spawned.

7. Alexander Pope – The Rape of the Lock

Based on an incident said to have been described to Pope by a friend, The Rape of the Lock is his most famous poem. It’s a witty satire of England’s ruling classes, written in the style of the classical heroic epics (such as the works of Homer) that he also devoted his time to translating. The work is an important example of satire during this period (of which Jonathan Swift’s A Modest Proposal is also an excellent example), the aim of which was to poke fun at society’s failings and corruption, particularly when contrasted with the prevailing ideals.

The Romantic Period (1798 – 1870)

The Romantic period was a response to the major social change taking place in England at the time, with the Industrial Revolution seeing a move from countryside to town, and the advent of polluted, overcrowded industrial cities. The Romantic period was also a reaction against the thoughts and ideals of the Age of Enlightenment, in which poets in particular rejected the scientific rationalisation of nature.

8. William Wordsworth – Lyrical Ballads

William Wordsworth was one of a group of poets whose work exemplifies Romanticism, and his poems, many of which were written at his home in the Lake District, are some of the finest examples of Romantic literature. The Lyrical Ballads was a collection of poems mostly by Wordsworth, with a few contributed by his friend, Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Though the response to the collection at the time of its publication was underwhelming, it is now seen as an important development in English literature because the simpler language used – a reaction against the florid, overly intellectual language of 18th century poetry – made the poems accessible to anybody. This was also an acknowledgement of the fact that human emotion is a universal experience, whether rich or poor – an idea also reflected in the title of the collection and the use of the ballad form, which came from a long tradition of oral storytelling beloved of the poor.

Transcendental Movement (1830 – 1860)

While the likes of Wordsworth, Coleridge and Shelley dominated the Romantic scene here in England, another movement was developing over in America, where Romanticism influenced New England Transcendentalism. Followers of this movement believed in the innate goodness of the individual and of nature, but also that the individual is prone to corruption by society and its organised religion and politics. Like Romanticism, Transcendentalism reacted against rationalisation and advocated the power of inherent human spirituality.

9. Louisa May Alcott – Little Women

The Transcendentalist writer of whom most British people will have heard is Louisa May Alcott, author of the much-loved Little Women series. Her father, Amos Bronson Alcott, was a prominent figure in the movement, and his ideas shaped Alcott’s education and upbringing, making the movement an important backdrop to her literary career. Her family and its transcendental thinking formed the inspiration for Little Women – the character of Jo being a loose portrayal of Alcott herself. The novel is still a childhood staple in homes in the USA and Britain alike.

Literary Realism (1820-1920)

Literary realism began in France in the mid-19th century, though a move towards realism had begun earlier; Jane Austen’s novels are part of the transition. Its focus was on realistic depictions of contemporary life and society, including realistic details of day-to-day life – the kind of scenes previously shunned in favour of the idealised subjects of the Romantics.

10. George Eliot – Middlemarch

The true masterpiece of this period is George Eliot’s Middlemarch , its realism evident even from its subtitle: “A Study of Provincial Life”. The Middlemarch of the novel’s title is a fictional Midlands town populated by the many characters whose lives intermingle in a series of masterfully woven plotlines. The realistic details with which Eliot narrates her characters’ problems and their reactions to the real-life issues of the day (such as the development of the railways) are what makes the novel so impressive, earning it high praise from literary critics, some of whom have described it as the greatest of all English novels.

Victorian Literature (1837 – 1901)

The reign of Queen Victoria saw the novel come to the fore as the leading literary genre, and it was a period that saw the emergence of some of the country’s most famous writers, including Charles Dickens, Thomas Hardy, William Thackeray and the Bronte sisters. Poetry was still a prominent literary genre, with Browning and Tennyson two of the most famous Victorian poets; but this form was far less significant than it had been during the Romantic period. Later in the Victorian period we see drama emerge as a significant genre again for the first time since the Renaissance, with Gilbert and Sullivan’s comic operas, and the plays of George Bernard Shaw and Oscar Wilde.

11. Charles Dickens – Oliver Twist

Victorian novelist Charles Dickens is one of the most famous of all English authors, and his novels are often seen as the archetypal Victorian novels. They’ve been so influential that the term “Dickensian” is often used to describe anything reminiscent of his novels, in particular the atmosphere conjured up in his tales of young street urchins living in urban poverty in grim Victorian London. The atmosphere of one of his most famous novels, Oliver Twist , is a good example of this. It tells the tale of a young orphan, who’s living in appalling conditions in a workhouse before he’s sent to live with an undertaker – from whom he escapes and goes on to join a group of juvenile pickpockets. It speaks powerfully about the treatment of orphans in Victorian London, and is also a good example of Dickens’ superb characterisation – notably the character of Fagin, ringleader of the pickpockets.

Modernism (1901-1939)

Just as previous literary movements had rebelled against the attitudes of those that had gone before them, so literary modernism reacted against the conservative attitudes of the Victorian period; the First World War was also a key influence. An important characteristic of modernism is self-consciousness, which saw a spate of literary experimentation; the stream-of-consciousness novel was one such innovation.

12. James Joyce – Ulysses

In James Joyce’s Ulysses , the idea of stream-of-consciousness was taken to the extreme in a novel described as “a demonstration and summation of the entire [Modernist] movement”. In a way, it’s a modern retelling of Homer’s The Odyssey , based on the experiences of its protagonist throughout the course of a day in Dublin. The novel broke new ground in many ways, but its most famous characteristic is its use of a different literary genre or experiment for each chapter; one, for example, has no punctuation, while another is written as though it were a play.

The Ten Best History Books of 2021

Our favorite titles of the year resurrect forgotten histories and help explain how the U.S. got to where it is today

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

Meilan Solly

Associate Editor, History

:focal(1400x1053:1401x1054)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/17/09/17095acb-748c-476b-b985-ec5b7529607a/inarticle-history-books2021-1400w.jpg)

After 2020 brought the most devastating global pandemic in a century and a national reckoning with systemic racism , 2021 ushered in a number of welcome developments, including Covid vaccines , the return of beloved social traditions like the Olympics and public performances , and incremental but measurable progress in the fight against racial injustice .

During this year of change, these ten titles collectively serve a dual purpose. Some offer a respite from reality, transporting readers to such varied locales as ancient Rome, Gilded Age America and Angkor in Cambodia. Others reflect on the fraught nature of the current moment, detailing how the nation’s past—including the mistreatment of Japanese Americans during World War II and police brutality—informs its present and future. From a chronicle of civilization told through clocks to a quest for Indigenous justice in colonial Pennsylvania, these were some of our favorite history books of 2021.

Four Lost Cities: A Secret History of the Urban Age by Annalee Newitz

“It’s terrifying to realize that most of humanity lives in places that are destined to die,” writes Annalee Newitz in the opening pages of Four Lost Cities . This stark statement sets the stage for the journalist’s incisive exploration of how cities collapse—a topic with clear ramifications for the “global-warming present,” as Kirkus notes in its review of the book. Centered on the ancient metropolises of Çatalhöyük , a Neolithic settlement in southern Anatolia; Pompeii , the Roman city razed by Mount Vesuvius’ eruption in 79 C.E.; Angkor , the medieval Cambodian capital of the Khmer Empire; and Cahokia , a pre-Hispanic metropolis in what is now Illinois, Four Lost Cities traces its subjects’ successes and failures, underscoring surprising connections between these ostensibly disparate societies.

All four cities boasted sophisticated infrastructure systems and ingenious feats of engineering. Angkor, for instance, became an economic powerhouse in large part due to its complex network of canals and reservoirs, while Cahokia was known for its towering earthen pyramids , which locals imbued with spiritual significance. Despite these innovations, the featured urban hubs eventually succumbed to what Newitz describes as “prolonged periods of political instability”—often precipitated by poor leadership and social hierarchies—“coupled with environmental collapse.” These same problems plague modern cities, the writer argues, but the past offers valuable lessons for preventing such disasters in the future, including investing in “resilient infrastructure, … public plazas, domestic spaces for everyone, social mobility and leaders who treat the city’s workers with dignity.”

Four Lost Cities: A Secret History of the Urban Age

A quest to explore some of the most spectacular ancient cities in human history―and figure out why people abandoned them

Covered With Night: A Story of Murder and Indigenous Justice in Early America by Nicole Eustace

In the winter of 1722, two white fur traders murdered Seneca hunter Sawantaeny after he refused their drunken, underhanded attempts to strike a deal. The ensuing furor, writes historian Nicole Eustace in Covered With Night , threatened to spark outright war between English colonists and the Indigenous inhabitants of the mid-Atlantic. Rather than enter into a prolonged, bloody battle, the Susquehanna River valley’s Native peoples forged an agreement, welcoming white traders back into their villages once Sawantaeny’s body had been metaphorically “covered,” or laid to rest in a “respectful, ritualized way,” as Eustace told Smithsonian magazine’ s Karin Wulf earlier this year.

“Native people believe that a crisis of murder makes a rupture in the community and that rupture needs to be repaired,” Eustace added. “They are not focused on vengeance; they are focused on repair, on rebuilding community. And that requires a variety of actions. They want emotional reconciliation. They want economic restitution.”

The months of negotiation that followed culminated in the Albany Treaty of 1722 , which provided both “ritual condolences and reparation payments” for Sawantaeny’s murder, according to Eustace. Little known today, the historian argues, the agreement underscores the differences between Native and colonial conceptions of justice. Whereas the former emphasized what would now be considered restorative justice (an approach that seeks to repair harm caused by a crime), the latter focused on harsh reprisal, meting out swift executions for suspects found guilty. “The Pennsylvania colonists never really say explicitly, ‘We’re following Native protocols. We’re accepting the precepts of Native justice,’” Eustace explained to Smithsonian . “But they do it because in practical terms they didn’t have a choice if they wanted to resolve the situation.”

Covered with Night: A Story of Murder and Indigenous Justice in Early America

An immersive tale of the killing of a Native American man and its far-reaching implications for the definition of justice from early America to today

Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty by Patrick Radden Keefe

The Sackler family’s role in triggering the U.S. opioid epidemic attracted renewed attention this year with the release of “ Dopesick ,” a Hulu miniseries based on Beth Macy’s 2018 book of the same name , and Patrick Radden Keefe ’s award-winning Empire of Pain , which exhaustively examines the rise—and very public fall—of the drug-peddling American “dynasty.”

Meticulously researched, the book traces its roots to the early 2010s, when the journalist was reporting on Mexican drug cartels for the New York Times magazine . As Keefe tells the London Times , he realized that 25 percent of the revenue generated by OxyContin, the most popular pill pushed by Sackler-owned Purdue Pharma, came from the black market. Despite this trend, the family was better known for its donations to leading art museums than its part in fueling opioid addiction. “There was a family that had made billions of dollars from the sale of a drug that had such a destructive legacy,” Keefe says, “yet hadn’t seemed touched by that legacy.” Infuriated, he began writing what would become Empire of Pain .

The resulting 560-page exposé draws on newly released court documents, interviews with more than 200 people and the author’s personal accounts of the Sacklers’ attempts to intimidate him into silence. As the New York Times notes in its review, the book “paint[s] a devastating portrait of a family consumed by greed and unwilling to take the slightest responsibility or show the least sympathy for what it wrought.”

Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty

A grand, devastating portrait of three generations of the Sackler family, famed for their philanthropy, whose fortune was built by Valium and whose reputation was destroyed by OxyContin

Until I Am Free: Fannie Lou Hamer's Enduring Message to America by Keisha N. Blain

Historian Keisha N. Blain derived the title of her latest book from a well-known quote by its subject, voting rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer : “We have a long fight and this fight is not mine alone, but you are not free whether you are white or Black, until I am free.” As Blain wrote for Smithsonian last year, Hamer, who grew up in the Jim Crow South in a family of sharecroppers , first learned about her right to vote in 1962, at the age of 44. After attempting to register to vote in Mississippi, she faced verbal and physical threats of violence—experiences that only strengthened her resolve.

Blain’s book is one of two new Hamer biographies released in 2021. The other, Walk With Me by historian Kate Clifford Larson , offers a more straightforward account of the activist’s life. Comparatively, Blain’s volume situates Hamer in the broader political context of the civil rights movement. Both titles represent a long-overdue celebration of a woman whose contributions to the fight for equal rights have historically been overshadowed by men like Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X.

Until I Am Free: Fannie Lou Hamer's Enduring Message to America

Explores the Black activist’s ideas and political strategies, highlighting their relevance for tackling modern social issues including voter suppression, police violence, and economic inequality

Into the Forest: A Holocaust Story of Survival, Triumph, and Love by Rebecca Frankel

On April 30, 1942, 11-year-old Philip Lazowski found himself separated from his family during a Nazi selection in the Polish town of Zhetel. Realizing that the elderly, the infirm and unaccompanied children were being sent in one direction and families with work permits in the other, he tried to blend in with the children of a woman he recognized, only to hear her hiss , “Don’t stand next to us. You don’t belong in this group.” Looking around, Lazowski soon spotted another stranger and her daughters. Desperate, he pleaded with her to let him join them. After pausing momentarily, the woman— Miriam Rabinowitz —took his hand and said, “If the Nazis let me live with two children, they’ll let me live with three.”

All four survived the selection. From there, however, their paths temporarily diverged. Lazowski reunited with his family, remaining imprisoned in the Zhetel ghetto before fleeing into the nearby woods, where he remained hidden for the next two and a half years. Miriam, her husband Morris and their two children similarly sought refuge in a forest but did not encounter Lazowski again until after the war. (Lazowski later married one of the Rabinowitz daughters, Ruth, after running into Miriam at a 1953 wedding in Brooklyn—a “stroke of luck that … mirrors the random twists of fate that enabled the family to survive while so many others didn’t,” per Publishers Weekly .)

As journalist Rebecca Frankel writes in Into the Forest , the Rabinowitzes and Lazowski were among the roughly 25,000 Jews who survived the war by hiding out in the woods of Eastern Europe. The majority of these individuals (about 15,000) joined the partisan movement , eking out a meager existence as ragtag bands of resistance fighters, but others, like the Rabinowitzes, formed makeshift family camps, “aiming not for revenge but survival,” according to the Forward . Frankel’s account of the family’s two-year sojourn in the woods captures the harsh realities of this lesser-known chapter in Holocaust history, detailing how forest refugees foraged for food (or stole from locals when supplies were scarce), dug underground shelters and remained constantly on the move in hopes of avoiding Nazi raids. Morris, who worked in the lumber business, used his pre-war connections and knowledge of the forest to help his family survive, avoiding the partisans “in the hope of keeping outside the fighting fray,” as Frankel writes for the New York Times . Today, she adds, the stories of those who escaped into the woods remain “so elusive” that some scholars have referred to them as “the margins of the Holocaust.”

Into the Forest: A Holocaust Story of Survival, Triumph, and Love

From a little-known chapter of Holocaust history, one family’s inspiring true story

The Man Who Hated Women: Sex, Censorship, and Civil Liberties in the Gilded Age by Amy Sohn

Though its title might suggest otherwise, The Man Who Hated Women focuses far more on the American women whose rights Anthony Comstock sought to suppress than the sexist government official himself. As novelist and columnist Amy Sohn explains in her narrative non-fiction debut, Comstock , a dry goods seller who moonlighted as a special agent to the U.S. Post Office and the secretary of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, spent more than four decades hounding activists who advocated for women’s reproductive rights. In 1873, he lobbied Congress to pass the Comstock Act , which made it illegal to send “obscene, lewd or lascivious” material—including documents related to birth control and sexual health —through the mail; in his view, the author adds, “obscenity, which he called a ‘hydra-headed-monster,’ led to prostitution, illness, death, abortions and venereal disease.”

The Man Who Hated Women centers on eight women activists targeted by Comstock: among others, Victoria Claflin Woodhull, the first woman to run for president; anarchist and labor organizer Emma Goldman; Planned Parenthood founder and notorious eugenicist Margaret Sanger ; abortionist Ann “ Madam Restell ” Lohman; and homeopath Sarah Chase , who fought back against censorship by dubbing a birth control device the “Comstock Syringe.” Weaving together these women’s stories, Sohn identifies striking parallels between 19th- and 20th-century debates and contemporary threats to abortion rights. “Risking destitution, imprisonment and death,” writes the author in the book’s introduction, “[these activists] defined reproductive liberty as an American right, one as vital as those enshrined in the Constitution. … Without understanding [them], we cannot fight the assault on women’s bodies and souls that continues even today.”

The Man Who Hated Women: Sex, Censorship, and Civil Liberties in the Gilded Age