- Open access

- Published: 01 October 2021

Oral health care for the critically ill: a narrative review

- Lewis Winning 1 ,

- Fionnuala T. Lundy 2 ,

- Bronagh Blackwood 2 ,

- Daniel F. McAuley 2 &

- Ikhlas El Karim ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5314-7378 2

Critical Care volume 25 , Article number: 353 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

21k Accesses

11 Citations

134 Altmetric

Metrics details

The link between oral bacteria and respiratory infections is well documented. Dental plaque has the potential to be colonized by respiratory pathogens and this, together with microaspiration of oral bacteria, can lead to pneumonia particularly in the elderly and critically ill. The provision of adequate oral care is therefore essential for the maintenance of good oral health and the prevention of respiratory complications.

Numerous oral care practices are utilised for intubated patients, with a clear lack of consensus on the best approach for oral care. This narrative review aims to explore the oral-lung connection and discuss in detail current oral care practices to identify shortcomings and offer suggestions for future research. The importance of adequate oral care has been recognised in guideline interventions for the prevention of pneumonia, but practices differ and controversy exists particularly regarding the use of chlorhexidine. The oral health assessment is also an important but often overlooked element of oral care that needs to be considered. Oral care plans should ideally be implemented on the basis of an individual oral health assessment. An oral health assessment prior to provision of oral care should identify patient needs and facilitate targeted oral care interventions.

Oral health is an important consideration in the management of the critically ill. Studies have suggested benefit in the reduction of respiratory complication such as Ventilator Associated Pneumonia associated with effective oral health care practices. However, at present there is no consensus as to the best way of providing optimal oral health care in the critically ill. Further research is needed to standardise oral health assessment and care practices to enable development of evidenced based personalised oral care for the critically ill.

Introduction

The oral cavity houses the second largest microbiota in the human body and includes bacteria, fungi, viruses, and archaea [ 1 ]. The majority of micro-organisms within the oral cavity are found within biofilms consisting of mostly commensal bacteria that are considered beneficial for the host. However, dysbiosis of the microbial biofilm can lead to dental diseases such as periodontitis and tooth decay [ 2 ]. Periodontitis is a chronic inflammatory disease affecting the supporting tissues of the teeth and is generally caused by oral anaerobic bacteria in a susceptible individual. The disease is highly prevalent, with severe forms affecting 10% of the population [ 3 ]. Tooth decay, on the other hand, is caused by acid produced by oral bacterial fermentation of dietary carbohydrates. Untreated dental caries is the 2nd most common chronic disease, with 2.4 billion individuals affected worldwide [ 4 ]. Untreated caries can ultimately lead to the death of the tooth and subsequent abscess formation in the underlying tissues.

Localised oral diseases, including periodontitis and caries-induced infections, have previously been shown to have systemic connections [ 5 ]. Oral bacteria commonly gain entrance to the circulation through ulcerated gingiva crevicular tissue that surrounds the teeth [ 6 ]. Invasion of the cariogenic Gram positive bacterium Streptococcus mutans into vascular endothelial cells is considered an exacerbating factor in infective endocarditis [ 7 ]. Additionally, oral bacteria including Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus sanguis, Enterococcus faecalis , and others have been implicated in the pathogenesis of infective endocarditis [ 8 ]. Poor oral hygiene in this regard, has been shown to be associated with an increased risk for infective endocarditis [ 9 ]. Gram negative oral bacteria and the local inflammatory response associated with periodontitis, can contribute to systemic inflammation and the initiation and progression of chronic inflammatory based diseases, including cardiovascular disease [ 10 ], diabetes [ 11 ] and respiratory disease [ 12 ].

This narrative review aims to provide an overview on the links between oral health and respiratory disease with particular consideration to the critically ill. We also consider the roles oral health assessment and oral care interventions have in the critically ill. A comprehensive search of the published English literature was conducted in PubMed, Medline, and Scopus until March 2021, using the following keywords: (“oral health” OR “oral disease” OR “periodontitis*” OR “caries” OR “oral health assessment” OR “oral health care” OR “oral prophylaxis”) AND (“critically ill” OR “critical care” OR “intensive care” OR “VAP”). Two of our investigators independently searched the databases (IEK and LW) and reviewed each of the retrieved articles.

Oral health and respiratory disease

The airway, including upper and lower segments, are a continuum of the oro-nasopharynx. Secretions of the upper airways are normally heavily contaminated with microorganisms originating from the oro-nasopharynx region. The lower airways, however, maintain a more sterile-like state supported by the cough reflex, the action of tracheobronchial secretions, mucociliary transport of inhaled microorganisms, and immune defence factors (cell-mediated immunity, humoral immunity, and neutrophils). In individuals with underlying chronic health problems, aspirated oral secretions containing potential pathogens are not always cleared effectively [ 13 ]. In these cases, pathogenic changes to the normal commensal microflora of the respiratory system, and more specifically potential infections that are derived from the oral cavity, represent a mechanistic pathway for an association with oral health.

The oral microbiome is comprised of over 600 prevalent taxa at the species level, with distinct subsets predominating in various oral habitats [ 1 ]. Dental caries and periodontitis are the most common oral diseases and are major causes of tooth loss [ 3 ]. Despite different aetiologies, caries and periodontal disease represent dysbiotic states of the oral microbiome [ 14 ]. In the absence of effective oral hygiene, initial dental plaque formation on a clean tooth surface will occur within 48 h. As the biofilm matures, its composition reflects the oral environment. If the pH in the oral cavity is low, then a cariogenic microbiota may predominate (Gram-positive bacteria and Candida albicans ), whereas if the gums are inflamed a periodontopathogenic microbiota is likely to predominate (anaerobic Gram-negative bacteria). Immunocompromised patients and individuals with low salivary flow rates will generally tend to be more susceptible to bacterial and fungal colonisation of the oral cavity. As well as leading to oral disease these pathogenic oral bacteria may be transported to the lungs where they have the potential to cause respiratory infections [ 15 ]. One cubic millimetre of dental plaque contains about 100 million bacteria [ 16 ], and may serve as a persistent reservoir for potential pathogens. Micro-aspiration of oral bacteria is common and frequently occurs during sleep. Studies have shown that typical aspirated volumes are of an amount likely to contain bacterial pathogens [ 17 ].

Amongst the associations between oral health and various respiratory diseases, the association with pneumonia has received much attention due to the strength of biological plausibility. Oral colonisation by respiratory pathogens, fostered by poor oral hygiene, has been associated with hospital-acquired pneumonia [ 12 , 18 ]. Hospital-acquired pneumonia is typically caused by bacteria that are not normally residents of the oropharynx but enter this milieu from the environment. These include Gram-negative bacilli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa , Staphylococcus aureus , and enteric species (such as Escherichia coli , Klebsiella pneumoniae, Serratia species, Enterobacter species ). In ventilator‐associated pneumonia (VAP), the placement of an endotracheal tube can transport oropharyngeal organisms into the lower airway [ 19 ]. The growth of a biofilm resistant to host defences and antibiotics, on the surface of the tube represents a further problem [ 20 ]. Recently, in an in vitro study, we showed that the opportunistic oral pathogen C. albicans enhanced bacterial numbers of the VAP pathogens; E . coli , S . aureus and MRSA in dual-species biofilms [ 21 ]. Studies have also linked community acquired pneumonia with poor oral hygiene [ 22 , 23 ].

There have been several systematic reviews that have aimed to investigate the association between oral health and pneumonia. Khadka et al. [ 24 ] performed a systematic review which included studies investigating pathogenic microorganisms in oral specimens of older people with aspiration pneumonia. Based on twelve studies (four cross-sectional, five cohort and three intervention) it was found that colonisation of the oral cavity by microorganisms commonly associated with respiratory infections. Furthermore, aspiration pneumonia occurred less in people who received professional oral care compared with no such care. In a systematic review focusing specifically on the association between periodontitis and nosocomial pneumonia, a meta-analysis was performed on 5 case–control studies that met the inclusion criteria [ 25 ]. A significant association was found between periodontitis and nosocomial pneumonia with an OR = 2.55, (95% CI 1.68–3.86). In a systematic review conducted by El-Rabbany et al. [ 26 ] focus was given to reviewing RCTs that evaluated the efficacy of prophylactic oral health procedures in reducing hospital-acquired pneumonia or ventilator-associated pneumonia. Twenty-eight trials were identified which found that good oral health care was associated with a reduction in the risk for hospital acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia in high-risk patients.

Oral health in critically ill intubated patients

Critically ill patients in the ICU represent a uniquely vulnerable group. Patients that are unconscious or sedated in ICUs often require mechanical ventilation with an associated risk of VAP. VAP significantly increases mortality and complications, resulting in an increased period of ventilation, longer ICU stay and associated increased costs [ 27 ]. It has been shown that oral health deteriorates following admission to ICU [ 28 ]. Dental plaque accumulates rapidly in the mouths of critically ill patients with a significant shift in plaque microbial community observed in mechanically ventilated patients, including colonisation with potential VAP pathogens [ 29 , 30 ]. This confirmed previous findings that respiratory pathogens isolated from the lung are often genetically indistinguishable from strains of the same species isolated from the oral cavity in patients who receive mechanical ventilation [ 31 ]. Plaque accumulation is exacerbated in the absence of adequate oral care and by the drying of the oral cavity due to prolonged mouth opening, leading to severe inflammation of soft tissues. Pre-existing poor oral health on admission to ICU further complicates the picture and has been recognised as a specific risk factor in VAP development [ 32 ]. More recently, a case control study has demonstrated the impact of poor oral health in the form of periodontitis, and the associated higher risk of ICU admission, need for assisted ventilation and mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic [ 33 ].

Oral health assessment

The oral health of intubated patients deteriorates with time in ICU and this is particularly problematic for those with pre-existing dental disease. Several studies have verified that teeth and other oral surfaces of patients in ICU subjects serve as reservoirs for respiratory pathogen colonization, with the pathogens causing pneumonia appearing to first colonize the dental plaque on teeth or dentures, rather than soft tissues [ 34 ]. In intubated patients with poor baseline dental health, such as periodontal disease and tooth decay, the dysbiotic plaque is likely to be mature and its removal requires special considerations. Oral health assessment prior to provision of oral care is therefore important to identify oral disease and subsequently target specific oral care needs. Oral health assessment is a descriptive health measurement needed to establish the patient’s baseline oral health status, changes in oral health during the course of care, and response to interventions [ 35 ]. An oral health assessment should include a general observation and an intra-oral examination to detect changes in the oral cavity, including, teeth, soft tissues and saliva [ 36 ]. The oral assessment should be performed frequently as part of a systematic patient assessment and should be used to identify those at increased risk of oral complications.

Despite the obvious benefits, an oral health assessment is not routinely performed for critically ill patients [ 37 , 38 ], as the process is considered time-consuming and requires the training of nursing staff to identify oral disease. Furthermore, the tools that are available for oral assessment are variable, mostly not validated and are mostly developed for oral health assessment in different settings but adapted for use in ICU (Table 1 ). It is therefore not surprising that wide variability in oral care assessment practices exists [ 39 ]. In a recent consensus paper, the British Association of Critical Nurses (BACCN) emphasised the importance of oral assessment and identified the need for further research [ 36 ]. Oral care protocols that were based on an oral health assessment were previously found to be more cost-effective and resulted in a significant reduction of VAP [ 40 , 41 , 42 ]. As the provision of oral care for the critically ill and in particular those who are mechanically ventilated is complex and demanding, oral health assessment prior to provision of oral care to identify the oral disease and subsequent targeted oral care interventions could result in more clinically and cost-effective care [ 40 , 41 ] .

Oral care interventions for the critically ill

The importance of adequate oral care has been recognised in guideline interventions for the prevention of VAP [ 43 ]. Different oral practices have been adopted for intubated patients, including toothbrushing and the use of oral care solutions such as antiseptic mouthwash. However, the most effective way to achieve good oral care in the ICU is not known, and there is currently a lack of consensus [ 44 ].

Among oral care solutions, the oral antiseptic chlorhexidine digluconate was reported as the most widely used antiseptic for oral hygiene in European ICU patients [ 45 ]. Multiple systematic reviews including both randomised and non-randomised clinical trials have reported the effectiveness of chlorhexidine (CHX) in reducing VAP and mortality (Table 2 ). A recent Cochrane review performed a meta-analysis based on 18 RCTs and found that CHX reduced the risk of VAP compared to placebo or usual care from 24% to about 18% (RR 0.75, 95% confidence intervals (CI) 0.62–0.91, P = 0.004) [ 46 ]. Despite this, the use of CHX has been brought into question by the finding that a possible (non-significant) increase in mortality was reported [ 44 , 47 , 48 ]. It not clear, however how CHX increases the risk of mortality which has led to calls for further research to investigate its safety in critical care settings [ 49 , 50 ]. CHX exhibits broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity and is considered stable, safe and effective in reducing plaque formation [ 51 ]. However, it has some disadvantages including, tooth discolouration and mucosal ulcerations when used in high concentrations, as well as emerging evidence of microbial resistance [ 52 ]. Furthermore, CHX has limited antimicrobial activities on established biofilms and therefore mechanical plaque removal, such as tooth brushing, is required prior to supplemental use of CHX [ 53 , 54 ]. Future studies should be designed with these limitations in mind. Within the critical care context, the method of application of chlorhexidine is also worthy of consideration, as the use of gels may be safer than solutions, to reduce the risk of microaspiration.

Although the adjunct use of chemical plaque control may be useful, effective control of dental plaque biofilm requires physical disruption with mechanical devices such as toothbrushing. Control of dental plaque and oral disease using mechanical means alone is well documented in the general population [ 55 , 56 ]. In the critically ill, mechanical plaque control is widely used, but its efficacy in reducing the incidence of VAP is debatable. A systematic review of four RCT that included 828 patients showed toothbrushing did not significantly reduce the incidence of VAP (RR, 0.77; 95% CI 0.50–1.21) and mortality (RR, 0.88; 95% CI 0.70–1.10) [ 57 ]. On the other hand, Zhao et al., showed in a combined meta-analysis of five studies (910 participants), that toothbrushing reduced the incidence of VAP (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.41–0.91, P = 0.01) [ 46 ]. In addition, toothbrushing compared to CHX was found to significantly reduce the duration of mechanical ventilation (MD − 1.46 days, 95% CI − 2.69 to − 0.23 days, P = 0.02) and ICU stay (MD − 1.89 days, 95% CI − 3.52 to − 0.27 days, P = 0.02), but had no effect on mortality (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.70–1.05, P = 0.14). It is important to note here that the efficacy of toothbrushing in reducing plaque in these studies was reported in only one study [ 58 ] where the reduction in plaque scores was associated with a reduction in VAP.

Toothbrushing combined with antiseptics is a commonly used oral hygiene practice and showed efficacy in controlling plaque and periodontal disease [ 59 ]. In their meta-analysis Zhao et al. combined two studies (649 participants), investigating toothbrushing with chlorhexidine compared to chlorhexidine alone and no difference in the incidence of VAP (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.50–1.09, P = 0.13), or mortality (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.68–1.12, P = 0.28) was found [ 46 ]. Another systematic review compared CHX alone to oral hygiene protocols involving mechanical removal of biofilm (toothbrushing, scrapping) together with chlorhexidine [ 60 ]. Their meta-analysis of six studies (1276 patients) showed a reduction in the incidence of VAP in oral care protocols that combined mechanical plaque removal and CHX (risk difference: − 0.06 (95% CI − 0.11 to − 0.02; P = 0.007). CHX is known to be deactivated if used immediately following toothbrushing with toothpaste containing anionic surfactants [ 61 ] and it is not clear from these studies whether such considerations were taken into account.

Other oral care interventions

Several other oral care solutions are used in ICU in addition to CHX. These include antiseptics such as povidone iodine, Listerine and triclosan as well as non-antiseptics such as saline and bicarbonate. In their systematic review, Zhao et al. compared povidone iodine rinse with a saline rinse or placebo in a meta-analysis of three studies (356 participants). They showed evidence of a reduction in VAP in the povidone iodine group (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.50–0.95, P = 0.02). On the contrary, their meta-analysis of 4 studies, which compared a saline rinse with a saline-soaked swab, found that saline rinse may reduce the incidence of VAP (RR 0.47, 95% CI 0.37–0.62, P < 0.001) [ 46 ]. A recent systematic review investigating the effectiveness of novel herbal oral care products in the prevention of VAP reported comparable affects to CHX [ 62 ]. However, with only a limited number of studies investigating these products, further studies are required.

It is apparent from the discussion above that there is no clear consensus on the most clinically relevant and cost-effective oral care intervention. In an attempt to define the most effective oral care intervention for the prevention of VAP, Sankaran and Sonis [ 64 ] exploited the existing meta-analysis data of a Cochrane systematic review [ 63 ], and performed a network meta-analysis (NMA) to compare different oral care interventions across different studies and rank the efficacy of each in the context of all of the interventions studied. The NMA included 25 studies (4473 subjects), 16 treatments, 29 pairwise comparisons, and 15 designs. The results based on the NMA most frequent ranking probability scores (P) showed that tooth brushing (P fixed-0.94, P random-0.89), tooth brushing with povidone-iodine (P fixed-0.90, Prandom-0.88), and furacillin (P fixed-0.88, P random-0.84) were the best three interventions for preventing VAP. CHX of 0.2% concentration (P score fixed of 0.65, P score random of 0.65) ranked as the second-best intervention in the network along with Biotene (P score fixed of 0.59, P score random 0.54) and potassium permanganate (P score fixed of 0.53, P score random 0.54). The NMA demonstrated the superiority of toothbrushing or mechanical cleaning and when combined with a mouthwash, NMA showed that tooth brushing is superior to a mouthwash alone and toothbrushing with povidone iodine is superior to any other mouthwash. The results of this NMA are however based on a mix of low risk and high risk of bias studies and are not recommended for clinical treatment needs. High quality clinical trials are needed taking into account the outcome of this NMA to determine the best intervention taking into account patient-specific oral care needs. A further consideration, relates to potential barriers in the implementation of oral care protocols. An ethnographic investigation found that the complexity of performing oral care in ICU setting is underestimated and undervalued [ 65 ]. Technical barriers included oral crowding with tubes and aversive responses by patients such as biting. Contextual impediments to oral care included time constraints, lack of training, and limited opportunities for interprofessional collaboration.

The contribution of poor oral hygiene and oral bacteria to the development of pneumonia is well established. Within the context of critical care, however, controversy exists as to the best practice to achieve optimal oral health care and whether this is reflected in better overall outcomes for ICU patients. Further research is needed to standardise oral care practices and personalise individuals’ oral health needs within the ICU.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

British Association of Critical Nurses

Beck Oral Assessment Score

Bedside oral exam

- Chlorhexidine

Cardiac surgery

Intensive care units

Mucosal Plaque Score

Non cardiac surgery

Network meta-analysis

Oral Assessment Guide

Randomised control trials

Ventilator associated pneumonia

Dewhirst FE, Chen T, Izard J, Paster BJ, Tanner ACR, Yu WH, Lakshmanan A, Wade WG. The human oral microbiome. J Bacteriol. 2010;192(19):5002–17.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Marsh PD, Zaura E. Dental biofilm: ecological interactions in health and disease. J Clin Periodontol. 2017;44(Suppl 18):S12-s22.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Kassebaum NJ, Bernabe E, Dahiya M, Bhandari B, Murray CJ, Marcenes W. Global burden of severe periodontitis in 1990–2010: a systematic review and meta-regression. J Dent Res. 2014;93(11):1045–53.

Frencken JE, Sharma P, Stenhouse L, Green D, Laverty D, Dietrich T. Global epidemiology of dental caries and severe periodontitis: a comprehensive review. J Clin Periodontol. 2017;44(Suppl 18):S94-s105.

Han YW, Wang X. Mobile microbiome: oral bacteria in extra-oral infections and inflammation. J Dent Res. 2013;92(6):485–91.

Lockhart PB, Brennan MT, Sasser HC, Fox PC, Paster BJ, Bahrani-Mougeot FK. Bacteremia associated with toothbrushing and dental extraction. Circulation. 2008;117(24):3118–25.

Abranches J, Zeng L, Bélanger M, Rodrigues PH, Simpson-Haidaris PJ, Akin D, Dunn WA Jr, Progulske-Fox A, Burne RA. Invasion of human coronary artery endothelial cells by Streptococcus mutans OMZ175. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2009;24(2):141–5.

Del Giudice C, Vaia E, Liccardo D, Marzano F, Valletta A, Spagnuolo G, Ferrara N, Rengo C, Cannavo A, Rengo G. Infective endocarditis: a focus on oral microbiota. Microorganisms. 2021;9(6):1218.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Lockhart PB, Brennan MT, Thornhill M, Michalowicz BS, Noll J, Bahrani-Mougeot FK, Sasser HC. Poor oral hygiene as a risk factor for infective endocarditis–related bacteremia. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140(10):1238–44.

Sanz M, Marco Del Castillo A, Jepsen S, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR, D’Aiuto F, Bouchard P, Chapple I, Dietrich T, Gotsman I, Graziani F, et al. Periodontitis and cardiovascular diseases: consensus report. J Clin Periodontol. 2020;47(3):268–88.

Sanz M, Ceriello A, Buysschaert M, Chapple I, Demmer RT, Graziani F, Herrera D, Jepsen S, Lione L, Madianos P, et al. Scientific evidence on the links between periodontal diseases and diabetes: Consensus report and guidelines of the joint workshop on periodontal diseases and diabetes by the International Diabetes Federation and the European Federation of Periodontology. J Clin Periodontol. 2018;45(2):138–49.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Linden GJ, Lyons A, Scannapieco FA. Periodontal systemic associations: review of the evidence. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40(Suppl 14):S8–19.

PubMed Google Scholar

Azarpazhooh A, Leake JL. Systematic review of the association between respiratory diseases and oral health. J Periodontol. 2006;77(9):1465–82.

Mira A, Simon-Soro A, Curtis MA. Role of microbial communities in the pathogenesis of periodontal diseases and caries. J Clin Periodontol. 2017;44(S18):S23–38.

Manger D, Walshaw M, Fitzgerald R, Doughty J, Wanyonyi KL, White S, Gallagher JE. Evidence summary: the relationship between oral health and pulmonary disease. Br Dent J. 2017;222(7):527–33.

MThoden van Velzenanger SK, Abraham-Inpijn L, Moorer WR. Plaque and systemic disease: a reappraisal of the focal infection concept. J Clin Periodontol. 1984;11(4):209–20.

Article Google Scholar

Gleeson K, Eggli DF, Maxwell SL. Quantitative aspiration during sleep in normal subjects. Chest. 1997;111(5):1266–72.

Scannapieco FA, Bush RB, Paju S. Associations between periodontal disease and risk for nosocomial bacterial pneumonia and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A systematic review. Ann Periodontol. 2003;8(1):54–69.

Safdar N, Crnich CJ, Maki DG. The pathogenesis of ventilator-associated pneumonia: its relevance to developing effective strategies for prevention. Respir Care. 2005;50(6):725–39 (; discussion 739–741 ).

Feldman C, Kassel M, Cantrell J, Kaka S, Morar R, Goolam Mahomed A, Philips JI. The presence and sequence of endotracheal tube colonization in patients undergoing mechanical ventilation. Eur Respir J. 1999;13(3):546–51.

Luo Y, McAuley DF, Fulton CR, Sá Pessoa J, McMullan R, Lundy FT. Targeting Candida albicans in dual-species biofilms with antifungal treatment reduces Staphylococcus aureus and MRSA in vitro. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(4):e0249547.

van der Maarel-Wierink CD, Vanobbergen JNO, Bronkhorst EM, Schols JMGA, de Baat C. Oral health care and aspiration pneumonia in frail older people: a systematic literature review. Gerodontology. 2013;30(1):3–9.

Kaneoka A, Pisegna JM, Miloro KV, Lo M, Saito H, Riquelme LF, LaValley MP, Langmore SE. Prevention of healthcare-associated pneumonia with oral care in individuals without mechanical ventilation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36(8):899–906.

Khadka S, Khan S, King A, Goldberg LR, Crocombe L, Bettiol S. Poor oral hygiene, oral microorganisms and aspiration pneumonia risk in older people in residential aged care: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2021;50(1):81–7.

Jeronimo LS, Abreu LG, Cunha FA, Lima RPE. Association between periodontitis and nosocomial pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2020;18(1):11–7.

El-Rabbany M, Zaghlol N, Bhandari M, Azarpazhooh A. Prophylactic oral health procedures to prevent hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(1):452–64.

Zimlichman E, Henderson D, Tamir O, Franz C, Song P, Yamin CK, Keohane C, Denham CR, Bates DW. Health care-associated infections: a meta-analysis of costs and financial impact on the US health care system. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(22):2039–46.

Terezakis E, Needleman I, Kumar N, Moles D, Agudo E. The impact of hospitalization on oral health: a systematic review. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38(7):628–36.

Sands KM, Twigg JA, Lewis MAO, Wise MP, Marchesi JR, Smith A, Wilson MJ, Williams DW. Microbial profiling of dental plaque from mechanically ventilated patients. J Med Microbiol. 2016;65(2):147–59.

Sands KM, Wilson MJ, Lewis MAO, Wise MP, Palmer N, Hayes AJ, Barnes RA, Williams DW. Respiratory pathogen colonization of dental plaque, the lower airways, and endotracheal tube biofilms during mechanical ventilation. J Crit Care. 2017;37:30–7.

Heo SM, Haase EM, Lesse AJ, Gill SR, Scannapieco FA. Genetic relationships between respiratory pathogens isolated from dental plaque and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients in the intensive care unit undergoing mechanical ventilation. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(12):1562–70.

Takahama A Jr, de Sousa VI, Tanaka EE, Ono E, Ito FAN, Costa PP, Pedriali MBBP, de Lima HG, Fornazieri MA, Correia LS, et al. Analysis of oral risk factors for ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill patients. Clin Oral Invest. 2021;25(3):1217–22.

Marouf N, Cai W, Said KN, Daas H, Diab H, Chinta VR, Hssain AA, Nicolau B, Sanz M, Tamimi F. Association between periodontitis and severity of COVID-19 infection: a case–control study. J Clin Periodontol. 2021;48(4):483–91.

Terpenning M, Bretz W, Lopatin D, Langmore S, Dominguez B, Loesche W. Bacterial colonization of saliva and plaque in the elderly. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16(Suppl 4):S314-316.

Abidia RF. Oral care in the intensive care unit: a review. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2007;8(1):76–82.

Collins T, Plowright C, Gibson V, Stayt L, Clarke S, Caisley J, Watkins CH, Hodges E, Leaver G, Leyland S, et al. British association of critical care nurses: evidence-based consensus paper for oral care within adult critical care units. Nurs Crit Care. 2021;26(4):224–33.

Grap MJ, Munro CL. Preventing ventilator-associated pneumonia: evidence-based care. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2004;16(3):349–58.

Berry AM, Davidson PM. Beyond comfort: oral hygiene as a critical nursing activity in the intensive care unit. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2006;22(6):318–28.

Labeau S, Vandijck D, Rello J, Adam S, Rosa A, Wenisch C, Bäckman C, Agbaht K, Csomos A, Seha M, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia: results of a knowledge test among European intensive care nurses. J Hosp Infect. 2008;70(2):180–5.

Ames NJ, Sulima P, Yates JM, McCullagh L, Gollins SL, Soeken K, Wallen GR. Effects of systematic oral care in critically ill patients: a multicenter study. Am J Crit Care. 2011;20(5):e103-114.

Labeau SO, Conoscenti E, Blot SI. Less daily oral hygiene is more in the ICU: not sure. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(3):334–6.

Prendergast V, Kleiman C, King M. The bedside oral exam and the barrow oral care protocol: translating evidence-based oral care into practice. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2013;29(5):282–90.

Hellyer TP, Ewan V, Wilson P, Simpson AJ. The Intensive Care Society recommended bundle of interventions for the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia. J Intensive Care Soc. 2016;17(3):238–43.

Torres A, Niederman MS, Chastre J, Ewig S, Fernandez-Vandellos P, Hanberger H, Kollef M, Li Bassi G, Luna CM, Martin-Loeches I, et al. International ERS/ESICM/ESCMID/ALAT guidelines for the management of hospital-acquired pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(3):1700582.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Rello J, Koulenti D, Blot S, Sierra R, Diaz E, De Waele JJ, Macor A, Agbaht K, Rodriguez A. Oral care practices in intensive care units: a survey of 59 European ICUs. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(6):1066–70.

Zhao T, Wu X, Zhang Q, Li C, Worthington HV, Hua F. Oral hygiene care for critically ill patients to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;12(12):008367.

Google Scholar

Klompas M, Speck K, Howell MD, Greene LR, Berenholtz SM. Reappraisal of routine oral care with chlorhexidine gluconate for patients receiving mechanical ventilation: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(5):751–61.

Price R, MacLennan G, Glen J. Selective digestive or oropharyngeal decontamination and topical oropharyngeal chlorhexidine for prevention of death in general intensive care: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ Br Med J. 2014;348:g2197.

Cuthbertson BH, Dale CM. Less daily oral hygiene is more in the ICU: yes. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(3):328–30.

Wittekamp BH, Plantinga NL. Less daily oral hygiene is more in the ICU: no. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(3):331–3.

Bonez PC, dos Santos Alves CF, Dalmolin TV, Agertt VA, Mizdal CR, et al. Chlorhexidine activity against bacterial biofilms. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41(12):e119–22.

Saleem HG, Seers CA, Sabri AN, Reynolds EC. Dental plaque bacteria with reduced susceptibility to chlorhexidine are multidrug resistant. BMC Microbiol. 2016;16:214.

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

ten Cate JM. Biofilms, a new approach to the microbiology of dental plaque. Odontology. 2006;94(1):1–9.

deLacerdaVidal CF, Vidal AKdL, Monteiro JGDM, Cavalcanti A, Henriques APDC, Oliveira M, Godoy M, Coutinho M, Sobral PD, Vilela CÂ, et al. Impact of oral hygiene involving toothbrushing versus chlorhexidine in the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a randomized study. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):112–112.

van der Weijden F, Slot DE. Oral hygiene in the prevention of periodontal diseases: the evidence. Periodontol 2000. 2011;55(1):104–23.

Slot DE, Valkenburg C, Van der Weijden GAF. Mechanical plaque removal of periodontal maintenance patients: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2020;47(Suppl 22):107–24.

Gu WJ, Gong YZ, Pan L, Ni YX, Liu JC. Impact of oral care with versus without toothbrushing on the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care. 2012;16(5):R190.

Yao LY, Chang CK, Maa SH, Wang C, Chen CC. Brushing teeth with purified water to reduce ventilator-associated pneumonia. J Nurs Res. 2011;19(4):289–97.

Figuero E, Roldán S, Serrano J, Escribano M, Martín C, Preshaw PM. Efficacy of adjunctive therapies in patients with gingival inflammation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2020;47(Suppl 22):125–43.

Pinto A, Silva BMD, Santiago-Junior JF, Sales-Peres SHC. Efficiency of different protocols for oral hygiene combined with the use of chlorhexidine in the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia. J Bras Pneumol. 2021;47(1):e20190286.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Balagopal S, Arjunkumar R. Chlorhexidine: the gold standard antiplaque agent. J Pharm Sci Res. 2013;5:270–4.

Mojtahedzadeh M, et al. Systematic review: effectiveness of herbal oral care products on ventilator-associated pneumonia. Phytother Res. 2021;35(7):3665–72.

Hua F, Xie H, Worthington HV, Furness S, Zhang Q, Li C: Oral hygiene care for critically ill patients to prevent ventilator‐associated pneumonia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016(10).

Sankaran SP, Sonis S. Network meta-analysis from a pairwise meta-analysis design: to assess the comparative effectiveness of oral care interventions in preventing ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill patients. Clin Oral Invest. 2021;25(5):2439–47.

Dale CM, Angus JE, Sinuff T, Rose L. Ethnographic investigation of oral care in the intensive care unit. Am J Crit Care. 2016;25(3):249–56.

Beck S. Impact of a systematic oral care protocol on stomatitis after chemotherapy. Cancer Nurs. 1979;2(3):185–99.

Henriksen BM, Ambjørnsen E, Axéll TE. Evaluation of a mucosal-plaque index (MPS) designed to assess oral care in groups of elderly. Spec Care Dentist. 1999;19(4):154–7.

Hayes J, Jones C. A collaborative approach to oral care during critical illness. Dent Health. 1995;34(3):6–10.

Silvestri L, Weir WI, Gregori D, Taylor N, Zandstra DF, van Saene JJM, van Saene HKF. Impact of oral chlorhexidine on bloodstream infection in critically Ill patients: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2017;31(6):2236–44.

Villar CC, Pannuti CM, Nery DM, Morillo CM, Carmona MJ, Romito GA. Effectiveness of intraoral chlorhexidine protocols in the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia: meta-analysis and systematic review. Respir Care. 2016;61(9):1245–59.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Dublin Dental University Hospital, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

Lewis Winning

Centre for Experimental Medicine, School of Medicine, Dentistry and Biomedical Sciences, Queen’s University Belfast, The Wellcome-Wolfson Building, 97 Lisburn Road, Belfast, BT9 7AE, Northern Ireland, UK

Fionnuala T. Lundy, Bronagh Blackwood, Daniel F. McAuley & Ikhlas El Karim

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

IEK, LW: conceptualization, draft preparation, FL, DMcA and BO’N: writing—original draft preparation, reviewing and editing. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ikhlas El Karim .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Winning, L., Lundy, F.T., Blackwood, B. et al. Oral health care for the critically ill: a narrative review. Crit Care 25 , 353 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-021-03765-5

Download citation

Received : 17 June 2021

Accepted : 11 September 2021

Published : 01 October 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-021-03765-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Oral health

- Oral bacteria

Critical Care

ISSN: 1364-8535

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 07 April 2017

Evidence summary: the relationship between oral health and pulmonary disease

- D. Manger 1 ,

- M. Walshaw 2 ,

- R. Fitzgerald 3 ,

- J. Doughty 4 ,

- K. L. Wanyonyi 5 ,

- S. White 6 &

- J. E. Gallagher 7

British Dental Journal volume 222 , pages 527–533 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

65 Citations

40 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Respiratory tract diseases

- Tooth brushing

Presents moderate evidence of an association between oral health and two pulmonary conditions: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and pneumonia.

Presents strong evidence that frail populations (such as ventilated, or community-living and hospital-based patients) would have a lower incidence of pneumonia after regular oral hygiene interventions which include use of chlorhexidine or povidone iodine, with stronger evidence supporting chlorhexidine in mouthwash, gel, or other forms.

Highlights that although evidence suggests that chlorhexidine reduces the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia, other outcomes such as mortality are not affected.

Introduction This paper is the second of four reviews exploring the relationships between oral health and general medical conditions, in order to support teams within Public Health England, health practitioners and policymakers.

Aim This review aimed to explore the most contemporary evidence on whether poor oral health and pulmonary disease occurs in the same individuals or populations, to outline the nature of the relationship between these two health outcomes, and discuss the implication of any findings for health services and future research.

Methods The work was undertaken by a group comprising consultant clinicians from medicine and dentistry, trainees, public health, and academics. The methodology involved a streamlined rapid review process and synthesis of the data.

Results The results identified a number of systematic reviews of medium to high quality which provide evidence that oral health and oral hygiene habits have an impact on incidence and outcomes of lung diseases, such as pneumonia and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in people living in the community and in long-term care facilities. The findings are discussed in relation to the implications for service and future research.

Conclusion The cumulative evidence of this review suggests an association between oral and pulmonary disease, specifically COPD and pneumonia, and incidence of the latter can be reduced by oral hygiene measures such as chlorhexidine and povidone iodine in all patients, while toothbrushing reduces the incidence, duration, and mortality from pneumonia in community and hospital patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Enhanced oral hygiene interventions as a risk mitigation strategy for the prevention of non-ventilator-associated pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Perspectives of community-dwelling older adults with dementia and their carers regarding their oral health practices and care: rapid review

Knowledge, attitudes and practices of patients and healthcare professionals regarding oral health and COPD in São Paulo, Brazil: a qualitative study

Pulmonary diseases can be broadly divided into lung infections, lung cancer, and those which obstruct airflow (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma). Lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and lower respiratory tract infections were three of the top six causes of years of life lost in England in 2013. 1 COPD and lung cancer are major causes of morbidity and mortality throughout the world. Pneumonia occurs in 1–2 individuals per 1,000, 2 is the cause of over 5% of all deaths for all ages in 2014, 3 and, together with influenza, accounted for the second-highest hospital bed days in the UK in 2014–2015. 4

Pneumonia is an inflammation of the lung, usually caused by infection. 5 Three common causes are bacteria, viruses and fungi, which may colonise the oral cavity and upper airway. 6 It is also possible to contract pneumonia by accidentally inhaling a liquid or chemical. People most at risk are aged over 65 or below two years, or have existing health problems; for example, mechanically ventilated patients who have an endotracheal tube placed from the oral cavity to the trachea to ensure a patent airway.

Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is a known complication of mechanical ventilation and defined as 'serious inflammation of the lung in patients who required the use of pulmonary ventilator'. 5 A patient may be ventilated for several reasons, primarily when they require critical care in intensive care units (ICUs) such as post-cardiac surgery, trauma, neurological or respiratory conditions, and for varying time periods.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is a type of obstructive lung disease characterised by chronically poor airflow. The main symptoms include shortness of breath, cough, and sputum. Tobacco smoking is the most common cause of COPD, with a number of other factors such as air pollution and genetics playing a smaller role. 5 It is diagnosed by a combination of clinical judgement, patient factors, and spirometry.

The two most common diseases affecting oral health are dental caries and periodontitis. Dental caries (caries) is the localised destruction of susceptible dental hard tissues by acidic by-products from bacterial fermentation of dietary carbohydrates. 7 Periodontitis is a chronic inflammatory disease caused by bacterial infection of the supporting tissues around the teeth. 8 Approximately half of all adults in the UK are affected by some level of irreversible periodontitis, which increases with age, and almost one third have obvious dental decay. 9

It is suggested that there is biological plausibility for a causal link between pulmonary disease and oral health related to oral disease pathogens aspirated into the pulmonary tissues. In the absence of effective oral care, initial plaque formation will occur within forty-eight hours; the composition of the oropharyngeal flora becomes more heavily colonised by virulent gram-negative pathogens that, as well as leading to oral disease, may be transported to the lungs where they have the potential to cause respiratory infections. 10 The aim of good mouth care is to maintain oral cleanliness, remove plaque and thereby prevent infection. 11 Twice daily brushing is recommended to control both periodontal diseases and caries; 12 however, the extent to which this may impact on pulmonary disease is unclear. In view of the serious outcomes and high prevalence related to both pulmonary and oral diseases, the aim of this review is to collate the most contemporary evidence on any links between the two.

A rapid review methodology was employed to synthesise the evidence from articles published between 2005 and 2015 that explored the relationship between pulmonary and oral health. A rapid review is a synthesis of the most current and best evidence to inform decision-makers. 13 It combines elements of systematic reviews with a streamlined approach to summarise available evidence in a timely manner.

Search syntax was developed based on subject knowledge, MeSH terms, and task group agreements ( Box. 1 ), followed by duplicate systematic title and abstract searches of three electronic databases: Cochrane, PubMed, OVID (Embase, MEDLINE (R), and PsycINFO). Two independent searches were carried out: screening papers by abstract, and title, for relevance and duplication.

Studies were included if they were either a systematic review and/or meta-analysis, and explored a link between pulmonary and oral health. Disagreements between the reviewers and the wider research group were resolved by discussion. Papers were excluded for the following reasons: did not mention any term related to oral health or pulmonary health; were not available in English or in full text after contacting primary authors; or if a more up-to-date review covering the same topics by the same authors was found.

The following information was extracted from each paper: author, year, population studied, oral disease/intervention, definitions used, methods, comparison/intervention and controls, outcomes, results, authors' conclusions, quality and quality justification, as shown in data extraction Supplementary Table 1 .

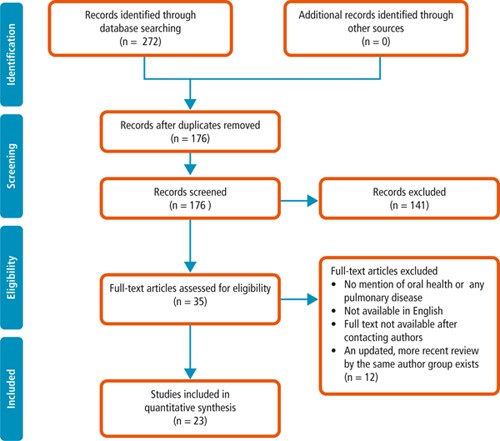

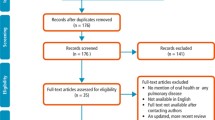

From a total of 272 papers initially identified based on title and abstract, 35 remained after removal of duplicates, title screening and reviewing abstracts for relevance. These papers were examined in full and 23 papers were identified as relevant for the rapid review and synthesis of findings. A flow diagram of the process is provided in Figure 1 .

PRISMA 2009 Flow Diagram

Papers were reviewed and the following themes identified: association between oral health and pulmonary diseases; association of oral health interventions with the onset and outcomes of pneumonia in both (i) community-living and non-ventilated hospital-based patients (henceforth referred to simply as 'community' and 'hospital' patients respectively), and (ii) ventilated patients. The majority of evidence relates to patients who had difficulty in managing, or were unable to manage, their own oral hygiene measures; this included children, older people, patients with dementia, mechanically ventilated patients, and patients with functional disabilities and/or critical illness. Quality assessment was undertaken for each systematic review. An AMSTAR assessment was carried out on all papers with the methodological quality of the review being rated as 'High' with a score between eleven and eight, 'Moderate' between seven and four, and 'Low' between four and zero. The quality of all papers was also assessed by group discussion to reinforce the conclusion reached by the quality score.

The quality of the selected studies varied. Of the 23 systematic reviews, 13 were deemed to be high quality in line with the AMSTAR scoring system, following group discussion. Nine papers were found to be of moderate and one of low quality. Common AMSTAR missing points were the inclusion of grey literature, the listing of excluded papers with reasons for their exclusion, and the quality assessment of the included studies. Quality scores, as well as rationale for these scores, are presented for each paper included in this review in the data extraction table ( Supplementary Table 1 ).

Within the themes identified by this review, the papers examining oral hygiene interventions in ventilated patients were of particularly strong quality, 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 with all but five systematic reviews, 21 , 23 , 24 , 26 , 27 of high quality, while the systematic reviews examining community and hospital patients were more mixed with three of high, 28 , 29 , 30 and three of moderate quality. 31 , 32 , 33 Finally, the papers examining a direct association between oral health and pulmonary diseases were all of moderate quality. 33 , 34 , 35

Box 1 Search terms

1. (pulmonary or respiratory or lung) and (disease$ or infection$ or condition$) (all fields)

2. (pneumonia or respiratory tract infection or RTI) (all fields)

3. (chronic obstructive pulmonary dis$ or COPD) (all fields)

4. (dysphagia or aspirat$ or ventil$) (all fields)

5. (pulmonary or lung or respiratory) and (cancer or neoplasm) (all fields)

6. asthma or tuberculosis (all fields)

7. (oral or dental) and (health or hygiene or disease$ or care or infection) (all fields)

8. (periodon$ or gum) and disease (all fields)

9. (caries or tooth decay or DMFT) (all fields)

10. (plaque or oral bacteria or respiratory pathogen) (all fields)

11. (toothbrush$ or tooth brush $ or chlorhexidine) (all fields)

12. (systematic review) (all fields)

13. (meta ana$ or meta-ana$) (all fields)

Cochrane, PubMed, OVID (Embase, MEDLINE (R), PsycINFO)

Results: evidence synthesis

The findings are reported in two main sections. First, the nature of association between oral and pulmonary disease, including whether or not the latter is more likely in patients with oral disease. Second, the evidence from studies that have tested the impact of oral hygiene measures on pulmonary disease incidence and outcomes.

A] Association between oral and pulmonary disease

Overall the literature suggests associations of varying strength between oral health (periodontitis, caries, and plaque) and pulmonary disease (COPD and pneumonia). This was demonstrated by the increased presence of oral disease, or oral pathogens, in those participants who developed pulmonary disease when compared with those who did not. No evidence was discovered regarding any association between oral health and the presence of other conditions, notably lung cancer or tuberculosis. In the next sections, evidence of the associations between individual oral diseases and COPD and pneumonia are presented.

I] Periodontitis and COPD

In the case of periodontitis and COPD, three reviews of moderate methodological quality highlight an association between COPD and periodontal disease. The first, by Azarpazhooh and Leake, 35 provided weak evidence of an association between COPD and periodontal disease, suggesting study participants with significantly higher alveolar bone loss (ABL) and loss of clinical attachment had a higher risk of COPD than their counterparts. The second review by Sjogren et al . 33 also highlighted a weak association between ABL and dental plaque with COPD. And a third by Zeng et al . 34 reviewed fourteen observational studies assessing the relationship between COPD and periodontal disease and included pooled data stratified to control for smoking and other risk factors associated with the two diseases; the stratified results showed an attenuated, but significant, association between COPD and periodontal disease (P <0.001).

II] Periodontitis and pneumonia

Azarpazhooh and Leake (2006) 35 reviewed five studies that explored the relationship between pneumonia and oral health, suggesting that periodontal pathogens in saliva are a potentially important risk factor for pneumonia. No evidence was found linking periodontal disease itself with pneumonia.

III] Caries and pneumonia

The presence of caries was linked to the development of pneumonia in one moderate quality review, 35 which reported evidence from a nine-year cohort study indicating that decayed teeth (that is, dental caries) ([OR] ∼ 1.2 per decayed tooth) and cariogenic bacteria in saliva and plaque ([OR] 4 to 9.6) were associated with a higher risk of pneumonia. 35

IV] Plaque and pneumonia

Plaque, and its association with pulmonary disease, was examined by one moderate quality review. The evidence to support this was mixed with two prospective cohort studies suggesting that higher plaque scores were associated with a previous history of respiratory tract infection, whilst a third found no such significant association between pneumonia and plaque scores. 35

In summary, there is moderate evidence to suggest that patients with caries and plaque have a higher likelihood of developing pneumonia, and weak evidence suggesting an increased likelihood of people with more alveolar bone loss developing COPD than comparable counterparts.

B] Effect of oral hygiene interventions on incidence and outcomes of pulmonary disease

In this section the impact of oral hygiene interventions is reported in two sub-sections: first in relation to community or hospital patients; and, second, in relation to ventilated patients.

I] Effect of oral hygiene interventions on incidence and outcomes of pulmonary disease in community or hospital patients

Several reviews described oral hygiene interventions and their impact on incidence, or outcomes, of pneumonia in non-ventilated patients in community or hospital environments, while no evidence was found regarding any other pulmonary disease (including COPD). Therefore, this section will solely deal with oral hygiene inventions and their effects on pneumonia. These interventions include the use of chlorhexidine with concentrations between 0.12–2.0%, povidone iodine, the cleaning of prostheses, and mechanical interventions such as toothbrushing or professional care involving scaling and polishing.

a) Incidence of pneumonia in community and hospital patients

Seven systematic reviews investigated the relationship between oral hygiene interventions and incidence of pneumonia in these patients, and all suggest there is good evidence that oral hygiene interventions (chlorhexidine, toothbrushing, professional oral care, povidone iodine) reduce the risk of pneumonia. 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 35 The review quality ranged from high, 16 , 26 , 28 which included a meta-analysis, to moderate. 31 , 32 , 33 , 35 Two reviews suggest that there is a reduced risk of pneumonia with combined effect of mechanical and professional care, 28 , 33 and a third by Van der Maarel-Wierink et al . 32 suggests that manual toothbrushing, with or without povidone iodine, reduced the risk of pneumonia in frail older people by 67%. Of note, while mechanical plaque removal was shown to reduce pneumonia incidence in non-ventilated patients, this result was not repeated for ventilated patients.

In summary, there is good evidence that oral hygiene interventions reduce the risk of pneumonia in community and hospital patients.

b) Outcomes of pneumonia

Three high to moderate quality reviews found that mortality was reduced by mechanical plaque removal in community and hospital patients. 19 , 28 , 32 One high quality review by Silvestri et al . suggested no significant impact of chlorhexidine on pneumonia-associated mortality, although this paper included both ventilated and non-ventilated hospital patients. 29 Kaneoka et al . 28 in a high quality review, suggest that there is moderate evidence from two randomised, controlled trials, that mechanical oral care can lead to a risk reduction in fatal pneumonia but highlight a need for caution due to a risk of possible bias in the included studies. 19 Similarly, two studies included in the systematic review by Van der Maarel-Wierink et al . 32 found that toothbrushing without povidone iodine reduced pneumonia mortality (RR = 2.40 and 95% CI = 1.54–3.74 and OR = 3.57; 95% CI = 1.13–13.70).

Two high quality reviews suggest that the number of febrile days may be reduced by implementing oral health interventions. 17 , 29 One review found that toothbrushing with 1% iodine, or scaling combined with electric toothbrushing led to a reduction in febrile days. 30 These reviews do not include meta-analysis and should therefore be considered with caution.

Use of topical antiseptics and professional oral health care both appear to reduce microbial colonisation of the oral cavity. In a high quality review, Silvestri et al ., 29 report that chlorhexidine controls both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria-related pneumonia as well as most (but not all) specific pneumonia-causing bacteria such as Streptococcus pneumoniae or Haemophilus influenza . However, when micro-organisms are classified into 'normal' and 'abnormal', chlorhexidine significantly reduces pneumonia due to 'normal' flora only. 29 One study in the review by Van der Maarel-Wierink et al . 32 suggests a reduction in levels of potential respiratory pathogens ( Streptococci, Staphylococci, Candida, Pseudomonas , and Black-pigmented Bacteroides species) after weekly professional oral healthcare. Professional oral care being defined as mechanical cleaning by a dentist/hygienist which varied in frequency from one to three times weekly.

A moderate quality review by Van der Maarel-Wierink et al ., which examined known risk factors for aspiration pneumonia reported an improvement in four out of five risk factors (swallowing latency time, activities of daily living scale, swallowing reflex, cough reflex sensitivity; but not salivary substance P) associated with regular oral hygiene. 32

In summary, good to moderate evidence suggests that oral hygiene interventions reduce many of the outcomes of pneumonia including febrile days, microbial colonisation, and mortality with the latter primarily being reduced by mechanical plaque removal.

II] The effect of oral hygiene interventions on incidence and outcomes of pulmonary disease in ventilated patients

There is a significant body of evidence relating to the effect of oral hygiene interventions on VAP, although no evidence regarding any other pulmonary disease. Again, this section focused on pneumonia and examines their impact on incidence and outcome, as well as cost-effectiveness and the role of different agents.

a) Incidence of VAP

In mechanically ventilated patients there is strong evidence from 13 systematic reviews that use of chlorhexidine (gel or mouthwash), when used in concentrations varying from 0.12–2.0%, reduces the risk of incidence of VAP. 14 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 24 , 26 , 27 , 29 , 30 , 31 Only one moderate-quality study, 25 the oldest included, did not find a significant reduction. The pooled relative risk of acquiring VAP reduced by approximately 40% when chlorhexidine-based oral decontamination was provided to ventilated patients in comparison to control groups (specifics of control groups varied among studies and included toothbrushing, 'standard oral care', placebo, other oral decontaminants, sterile water. Five reviews (two high, two moderate and one low quality) suggest the number needed to treat (NNT) as between 8 and 21 (with the high quality reviews finding a NNT of 14 and 15); meaning that between 8 and 21 ventilated patients in intensive care need to receive chlorhexidine oral decontamination for one case of VAP to be prevented. 20 , 22 , 26 , 27 , 33 Mechanical toothbrushing in addition to the use of chlorhexidine was not found to reduce the incidence of VAP by three high quality, and one moderate quality reviews. 14 , 15 , 20 , 23

In summary, there is strong evidence that regular chlorhexidine use in ventilated patients reduces the risk of VAP; with no evidence to show that mechanical plaque removal in addition to chlorhexidine provides further benefit.

b) Outcomes of VAP

No significant effect on mortality, duration of mechanical ventilation or duration of hospital stay was demonstrated, 14 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 22 , 24 , 25 , 26 and no evidence was found of a difference between chlorhexidine and placebo for the outcomes of VAP and mortality in children. 20 Other notable outcomes were that the use of chlorhexidine had a greater treatment effect in cardio-surgical patients, 24 , 29 , 36 and authors postulated that this was related to the planned nature of the intubation and the physical status of the patient at the time.

In relation to the impact of oral interventions on the use of systemic antibiotic therapy, Shi et al ., 20 a high quality review based on two randomised clinical trials, reported no significant difference in duration of antibiotic therapy, for the management of VAP, between intervention and control groups. One high quality systematic review, including four randomised-controlled trials, found no significant difference in antibiotic-free days between patients who received oral care and the control group. 15

Four reviews, 20 , 23 , 24 , 30 of high to medium quality, include evidence regarding oral health indices, in particular plaque scores. El-Rabbany et al ., 30 in a high quality review suggest that toothbrushing does improve oral health and has a positive effect on plaque scores when used on ventilated patients. It is suggested that this will reduce VAP, although as mentioned above, four reviews found toothbrushing had no effect. They do clarify that the studies reviewed were of moderate to high risk of bias. Two reviews, 23 , 24 report lower plaque levels in chlorhexidine groups versus controls in five trials, while one trial showed no such difference.

Shi et al . 20 reported the effect on plaque scores for toothbrushing versus no brushing and the use of chlorhexidine plus brushing versus a control group with chlorhexidine alone. The studies were of moderate to high risk of bias and presented ambivalent conclusions, when compared. One study indicated that plaque scores were improved, whereas the other three showed no difference.

In relation to microbial colonisation, Shi et al . found insufficient reliable and consistent evidence to confirm whether microbial colonisation of dental plaque varied between intervention and control groups for VAP. 20 On adverse effects of the interventions, two high and one moderate quality review 18 , 20 , 24 considered adverse effects in the evidence from the studies they included. One study reported that three patients receiving chlorhexidine complained of a transient, unpleasant taste and this compared to five patients in the control arm of the study. 20 In a further study, 9.8% of patients receiving chlorhexidine complained of mucosal irritation compared with 1% of the control group. 20 Snyder et al . 18 concurred with the comments from this study but added that further instruction to staff to be more gentle reduced the reports of irritation. Chlebicki et al . 24 reported no adverse effects.

Adverse effects/side effects reported were transient in nature and were reported in relation to both the chlorhexidine intervention and the control groups. The adverse effects of chlorhexidine were not unexpected and are those described within the drug proprietary literature. There was no reported evidence on the effect of oral hygiene interventions on the number of febrile days for ventilated patients.

In summary, there is moderate to low quality evidence that chlorhexidine does not have an effect on the following outcomes of VAP: mortality; duration of hospital stay; duration of ventilation; antibiotic use; plaque scores; microbial colonisation; or VAP in children. No unexpected side-effects of chlorhexidine were found.

c) Cost-effectiveness

Three systematic reviews reported on the cost-effectiveness of chlorhexidine as an oral care intervention. 16 , 18 , 24 Where chlorhexidine reduced the incidence of VAP by 43%, the comparative cost of a ye ar's supply of chlorhexidine (Peridex) was less than 10% of the cost associated with a single case of VAP. 16 The cost of chlorhexidine therapy for fourteen patients was suggested to be less than 10% of the cost of antibiotic therapy alone for one case of VAP. 16

Snyders et al . 18 also included two trials that considered the cost-effectiveness of chlorhexidine. Both suggested that chlorhexidine was cost-effective, and one suggested that the cost-effectiveness may be as much as ten times less per patient than the cost of antibiotics to treat VAP. 18 Chlebicki et al . 24 quotes studies examining costs of chlorhexidine, but notes no formal cost-effective analysis.

In summary, good evidence suggests that chlorhexidine is cost-effective when used to reduce pneumonia incidence.

d) Other antimicrobial agents

The effectiveness of topical application of povidone iodine for oral disinfection was considered in five systematic reviews of which four were high quality. 16 , 19 , 27 , 29 There is weak evidence that povidone iodine reduces the incidence of pneumonia, but this mode of oral disinfection was less effective than the use of chlorhexidine. 17 , 20 , 28 , 30 , 32

In summary, moderate evidence suggests both mechanical and chemical interventions have an impact on the incidence and outcomes of pneumonia in community and hospital patients. In regards to VAP, there is strong evidence that chemical interventions in general reduce incidence but do not affect other patient outcomes.

The cumulative evidence of this review suggests an association between oral and pulmonary disease, specifically COPD and pneumonia, and incidence of the latter can be reduced by oral hygiene measures such as chlorhexidine and povidone iodine in all patients, while toothbrushing reduces the incidence, duration, and mortality from pneumonia in community and hospital patients.

This review has a number of strengths and limitations which should be recognised. First, the review process conducted by a multidisciplinary team containing medical, dental, and public health professionals allowed for broad input and feedback and was thus considered a strength. Second, this is a 'rapid review', and so was intended to summarise existing evidence, rather than undertake quantitative synthesis of evidence. Third, there was large heterogeneity in the methodology of the studies in the literature reviewed including: variations in oral care interventions; varying measures of the chemical interventions such as chlorhexidine; and varying definitions/diagnoses of oral and pulmonary diseases; nonetheless there is important learning to inform future research.

The evidence has significant implications for research and services. First, the findings that highlight a reduction in the incidence of pneumonia in community and hospital patients after the implementation of oral hygiene measures (namely: toothbrushing, chlorhexidine, professional oral cleaning, and povidone iodine), provide useful data in planning for the oral health components of care pathways for patients with pneumonia. Second, a number of reviews demonstrated a reduction in the incidence of pneumonia after both chlorhexidine use and toothbrushing in community and hospital patients; and some studies, with a high risk of bias, additionally suggested that toothbrushing reduced the duration (days of fever) and mortality of pneumonia. Overall, this evidence supports the implementation of oral health protocols for pneumonia patients.

There was a greater volume of evidence on the role of oral hygiene interventions in reducing the incidence of VAP. Chlorhexidine was shown to be effective in reducing the incidence of VAP which has implications for patient well-being; it is also cost-effective, and without unexpected or severe adverse effects. In contrast to non-ventilated patients, toothbrushing alone had no effect on VAP incidence.

There is a clear need for further research, particularly around the cost-effectiveness and feasibility of implementation of oral hygiene interventions and their outcomes, as part of the care pathway for community-living and hospitalised frail patients in particular ( Table 1 ).

Although chlorhexidine was found to reduce the incidence of pneumonia as outlined in the paragraph above; other outcomes related to VAP, such as mortality or duration of ventilation/hospital-stay, were not affected by either chlorhexidine or toothbrushing. This seems contradictory and certainly warrants further investigation, especially as a low sample size and low attributable mortality of VAP may be the explanation. 37

So what can, and should, clinicians caring for community, hospital and ventilated patients do while waiting for this research? Numerous guidelines 38 , 39 , 40 recommend regular oral care, at least twice daily, to prevent oral disease and maintain oral health; this review highlights the additional importance of good oral hygiene for general health. Therefore, alongside oral health benefits, patients, carers, and relatives should be informed that improved oral hygiene may prevent episodes of pneumonia, and has been shown in some studies to reduce the incidence of mortality. In order to maintain optimal oral health, mechanical plaque removal by twice-daily toothbrushing is recommended. 12 Furthermore, the preventative effects of oral hygiene for the reduction of pneumonia can be further augmented by the oral application of chlorhexidine mouthwash, gels or other forms of delivery.

Where possible, this regimen can be carried out by the patient, with assistance from carers as required. An oral care plan should be created, implemented and reviewed at regular intervals; either by, or in consultation with, a dental professional. This is particularly important for patients who are unable to care for themselves. To prevent and improve the outcomes of pneumonia, commissioners and managers of services are advised to provide oral hygiene training for carers. Improving patients', relatives' and carers' knowledge of the effects of poor oral health has the potential to support health maintenance in vulnerable patients, deliver cost-effective care, and improve patient quality of life.

Newton J N, Briggs A D, Murray C J et al. Changes in health in England, with analysis by English regions and areas of deprivation, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015; 386 : 2257–2274.

Article Google Scholar

Torres A, Peetermans W E, Viegi G, Blasi F . Risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia in adults in Europe: a literature review. Thorax 2013; 68 : 1057–1065.

Office for National Statistics. Mortality Statistics: Deaths Registered in England and Wales (Series DR). Available online at https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/deathsregistrationsummarytables/2015-07-15 (accessed March 2017).

Health and Social Care Information Centre. Hospital Episode Statistics. Admitted Patient Care – England, 2014–2015. 2015.

World Health Organisation. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision. 2016.

Scannapieco F A, Shay K . Oral health disparities in older adults: oral bacteria, inflammation, and aspiration pneumonia. Dent Clin North Am 2014; 58 : 771–782.

Fejerskov O, Nyvad B, Kidd E . Dental caries: the disease and its clinical management . Third edition. Wiley-Blackwell, 2015.

Google Scholar

Eke P I, Page R C, Wei L, Thornton-Evans G, Genco R J . Update of the case definitions for population-based surveillance of periodontitis. J Periodontol 2012; 83 : 1449–1454.

Steele J, O'Sullivan I . Adult Dental Health Survey 2009. 2010. Available online at http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB01061/adul-dent-heal-surv-firs-rele-2009-rep.pdf (accessed March 2017).

Eley B, Manson J . Periodontics . Fifth edition. Wright, 2004.

Mallett J D, Lisa. The Royal Marsden Hospital Manual of Clinical Nursing Procedures. 2000.

NHS Public Health England. Delivering better oral health: an evidence-based toolkit for prevention. 2014.

Khangura S, Konnyu K, Cushman R, Grimshaw J, Moher D . Evidence summaries: the evolution of a rapid review approach. Syst Rev. 2012; 1 : 10.

Alhazzani W, Smith O, Muscedere J, Medd J, Cook D . Toothbrushing for critically ill mechanically ventilated patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials evaluating ventilator-associated pneumonia. Crit Care Med 2013; 41 : 646–655.

Gu W J, Gong Y Z, Pan L, Ni Y X, Liu J C . Impact of oral care with versus without toothbrushing on the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care 2012; 16 : R190.

Zhang T T, Tang S S, Fu L J . The effectiveness of different concentrations of chlorhexidine for prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a meta-analysis. J Clin Nurs 2014; 23 : 1461–1475.

Li L, Ai Z, Li L, Zheng X, Jie L . Can routine oral care with antiseptics prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia in patients receiving mechanical ventilation? An update meta-analysis from 17 randomized controlled trials. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015; 8 : 1645–1657.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Snyders O, Khondowe O, Bell J . Oral chlorhexidine in the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill adults in the ICU: A systematic review. S Afr J Crit Care 2011; 27.

Klompas M, Speck K, Howell M D, Greene L R, Berenholtz S M . Reappraisal of routine oral care with chlorhexidine gluconate for patients receiving mechanical ventilation: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2014; 174 : 751–761.

Shi Z, Xie H, Wang P et al. Oral hygiene care for critically ill patients to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 8 : CD008367.

Kola A, Gastmeier P . Efficacy of oral chlorhexidine in preventing lower respiratory tract infections. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Hosp Infect 2007; 66 : 207–216.

Chan E Y, Ruest A, Meade M O, Cook D J . Oral decontamination for prevention of pneumonia in mechanically ventilated adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2007; 334 : 889.

Berry A M, Davidson P M, Masters J, Rolls K . Systematic literature review of oral hygiene practices for intensive care patients receiving mechanical ventilation. Am J Crit Care 2007; 16 : 552–562; quiz 63.

PubMed Google Scholar

Chlebicki M P, Safdar N . Topical chlorhexidine for prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a meta-analysis. Crit Care Med 2007; 35 : 595–602.

Pineda L A, Saliba R G, El Solh AA . Effect of oral decontamination with chlorhexidine on the incidence of nosocomial pneumonia: a meta-analysis. Crit Care 2006; 10 : R35.

Balamurugan E, Kanimoxhi A, Kumari G . Effectiveness of chlorhexidine oral decontamination in reducing the incidence of ventilator associated pneumonia: a meta-analysis. Br J Med Pract 2012; 5.

Tantipong H, Morkchareonpong C, Jaiyindee S, Thamlikitkul V . Randomized controlled trial and meta-analysis of oral decontamination with 2% chlorhexidine solution for the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2008; 29 : 131–136.