How to Write an Article

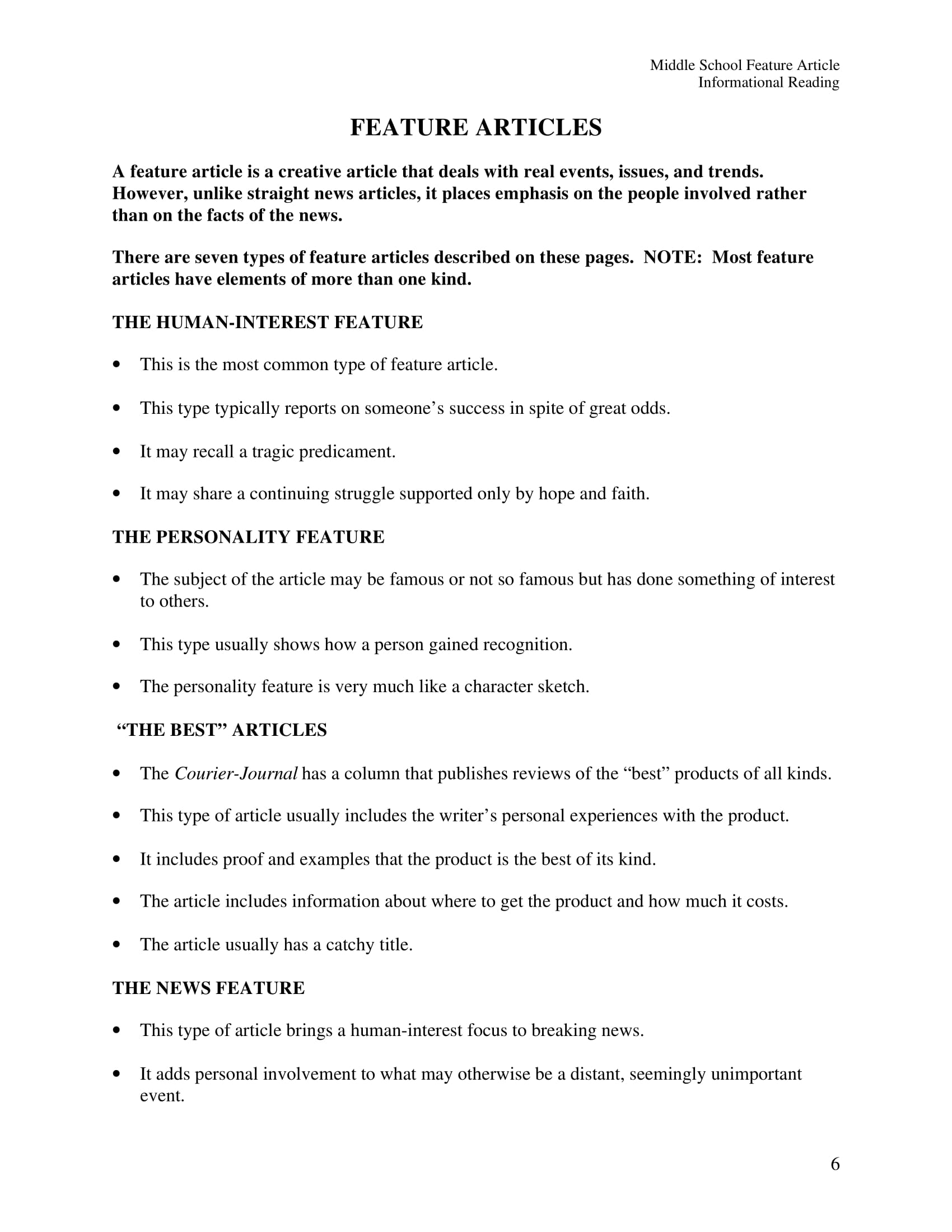

THE CRAFT OF ARTICLE WRITING

Writing is a complex skill. A very complex skill.

Not only do we put students under pressure to master the inconsistent spelling patterns and complex grammar of the English language, but we require them to know how to write for a variety of purposes in both fiction and nonfiction genres.

On top of this, writing is just one aspect of one subject among many.

The best way to help our students to overcome the challenge of writing in any genre is to help them to break things down into their component parts and give them a basic formula to follow.

In this article, we will break article writing down into its components and present a formulaic approach that will provide a basic structure for our students to follow.

Once this structure is mastered, students can, of course, begin to play with things.

But, until then, there is plenty of room within the discipline of the basic structure for students to express themselves in the article form.

A COMPLETE UNIT ON TEACHING NEWS REPORTING

With over FORTY GRAPHIC ORGANIZERS in this ENGAGING UNIT, you can complete a WEEKLY journalistic / Newspaper reporting task ALL YEAR LONG as classwork or homework.

These templates take students through a PROVEN four-step article writing process on some AMAZING images. Students will learn how to.

WHAT IS AN ARTICLE?

The Cambridge Dictionary defines an article as, “a piece of writing on a particular subject in a newspaper or magazine, or on the internet.”

An article’s shape and structure will vary depending on whether it’s intended for publication in a newspaper, magazine, or online.

Each of these media has its own requirements. For example, a magazine feature article may go into great depth on a topic, allowing for long, evocative paragraphs of exposition, while an online blog article may be full of lots of short paragraphs that get to the point without too much fanfare.

Each of these forms makes different demands on the writer, and it’s for this reason that most newspapers, magazines, and big websites provide writers with specific submission guidelines.

So, with such diverse demands placed on article writers, how do we go about teaching the diverse skill required to our students?

Luckily, we can break most types of articles down into some common key features.

Below we’ll take a look at the most important of these, along with an activity to get your students practicing each aspect right away.

Finally, we’ll take a look at a few general tips on article writing.

KEY WRITTEN FEATURES OF AN ARTICLE

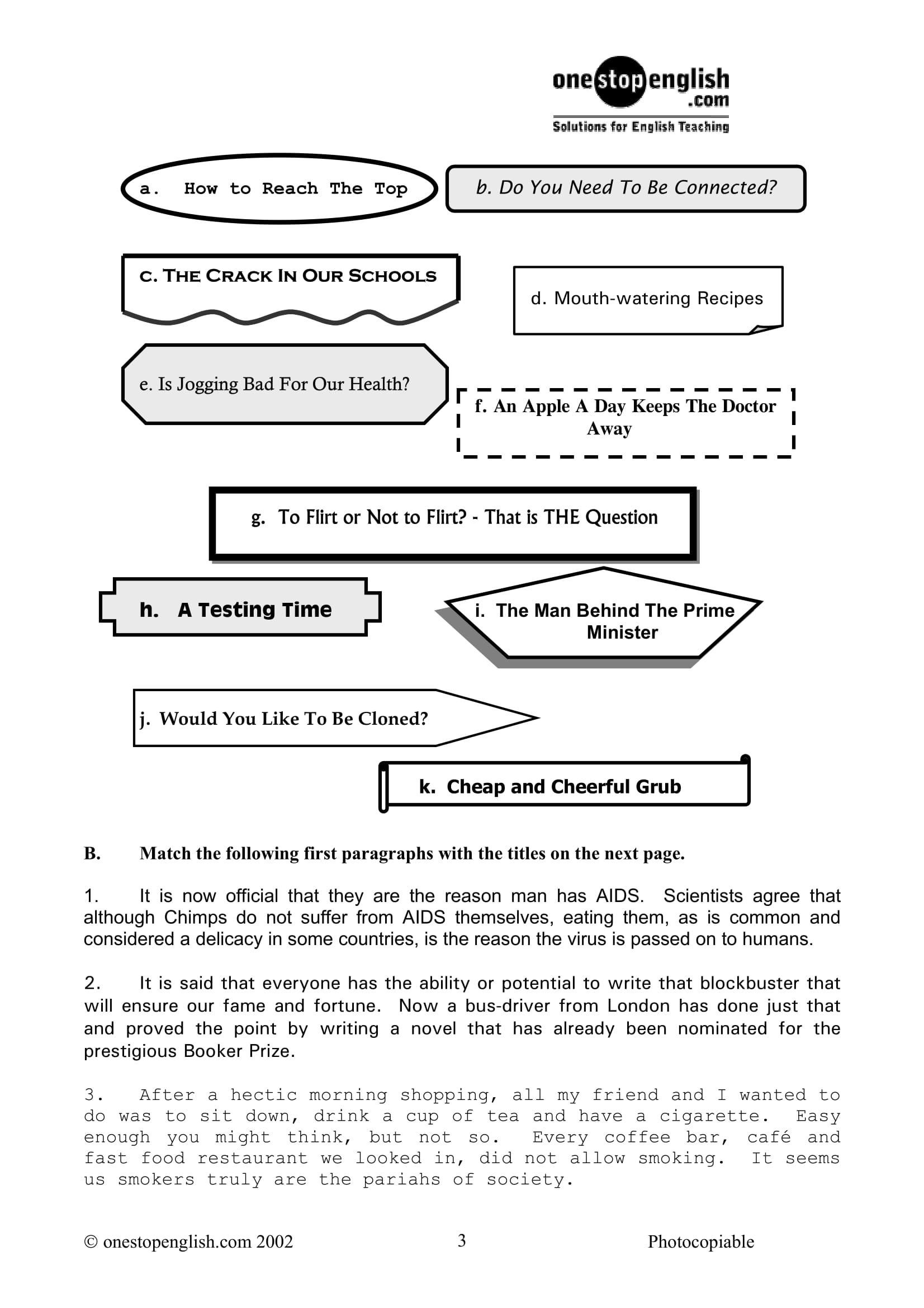

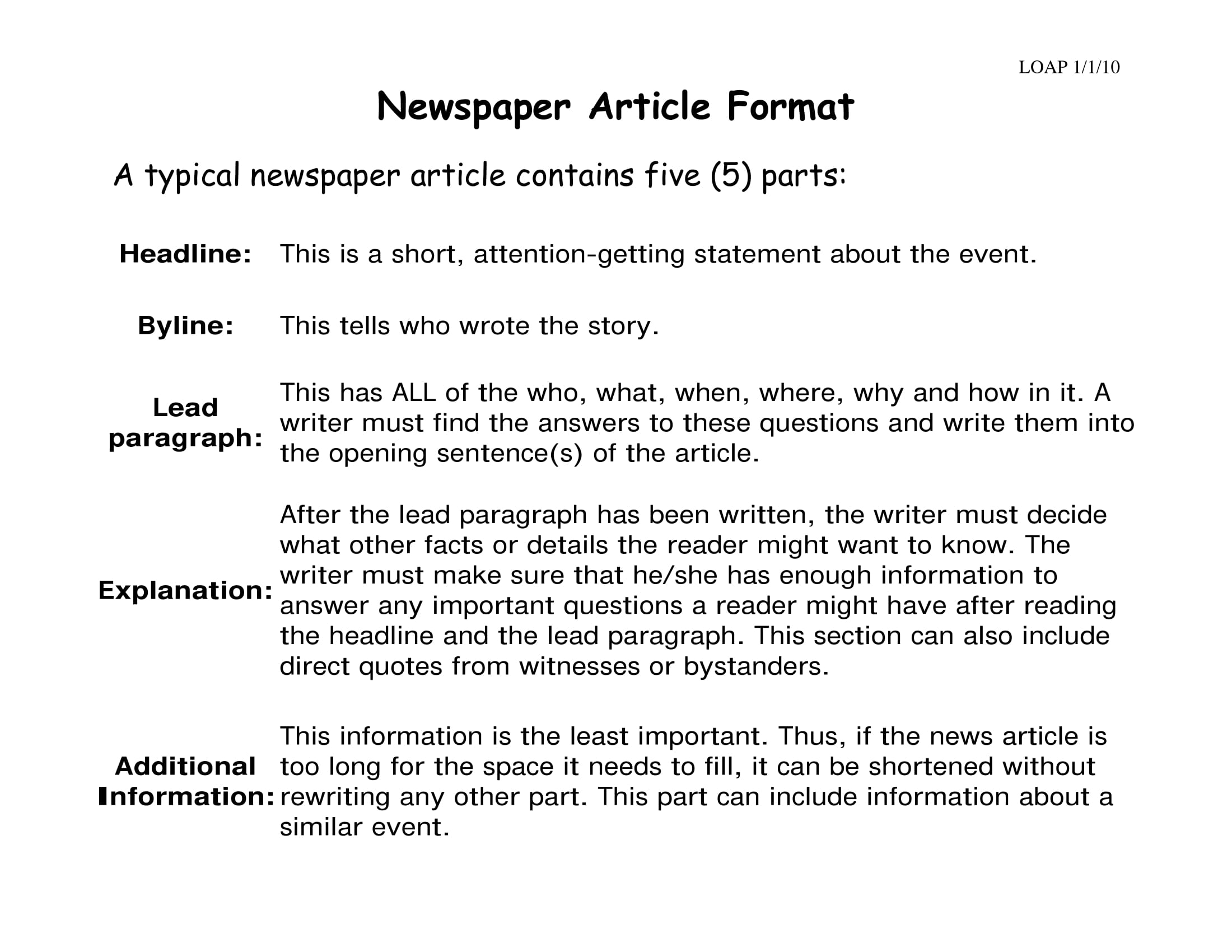

The headline.

The purpose of the headline is to capture the reader’s attention and let them know what the article is about. All of this in usually no more than 4 or 5 words!

There is an art to good headline writing and all sorts of literary devices (e.g alliteration and metaphor) can be used to create an eye-catching and intriguing headline.

The best way for students to learn how headlines work is to view some historical samples.

Newspaper headlines especially are known for being short and pithy. Here are just a few examples to whet the appetite:

- Hitler Is Dead

- Lincoln Shot

- Men Walk On The Moon

- Berlin Wall Crumbles

You could encourage students to find some pithy examples of their own. It’s amazing how much information can be condensed into so few words – this is the essence of good headline writing.

Headlines Practice Activity:

Give students opportunities to practice headline writing in isolation from article writing itself. For example, take sample stories from newspapers and magazines and challenge students to write new headlines for them. Set a word limit appropriate to the skills and age of the students. For example, younger, more inexperienced students might write 9-word headlines, while older, more skilled students might thrive with the challenge of a 4-word limit.

THE SUBHEADING

Subheadings give the reader more information on what the article is about. For this reason, they’re often a little longer than headlines and use a smaller font, though still larger (or in bold) than the font used in the body of the text.

Subheadings provide a little more of the necessary detail to inform readers what’s going on. If a headline is a jab, the subheading is the cross.

In magazines and online articles especially, there are often subheadings throughout the article. In this context, they let the reader know what each paragraph/section is about.

Subheadings also help the reader’s eye to scan the article and quickly get a sense of the story, for the writer they help immensely to organize the structure of the story.

Practice Activity:

One way to help organize paragraphs in an article is to use parallel structure.

Parallel structure is when we use similar words, phrases, and grammar structures. We might see this being used in a series of subheadings in a ‘How to’ article where the subheadings all start with an imperative such as choose , attach , cut , etc.

Have you noticed how all the sections in this ‘Key Features’ part of this article start simply with the word ‘The’? This is another example of a parallel structure.

Yet another example of parallel structure is when all the subheadings appear in the form of a question.

Whichever type of parallel structure students use, they need to be sure that they all in some way relate to the original title of the article.

To give students a chance to practice writing subheadings using parallel structure, instruct them to write subheadings for a piece of text that doesn’t already have them.

THE BODY PARAGRAPHS

Writing good, solid paragraphs is an art in itself. Luckily, you’ll find comprehensive guidance on this aspect of writing articles elsewhere on this site.

But, for now, let’s take a look at some general considerations for students when writing articles.

The length of the paragraphs will depend on the medium. For example, for online articles paragraphs are generally brief and to the point. Usually no more than a sentence or two and rarely more than five.

This style is often replicated in newspapers and magazines of a more tabloid nature.

Short paragraphs allow for more white space on the page or screen. This is much less daunting for the reader and makes it easier for them to focus their attention on what’s being said – a crucial advantage in these attention-hungry times.

Lots of white space makes articles much more readable on devices with smaller screens such as phones and tablets. Chunking information into brief paragraphs enables online readers to scan articles more quickly too, which is how much of the information on the internet is consumed – I do hope you’re not scanning this!

Conversely, articles that are written more formally, for example, academic articles, can benefit from longer paragraphs which allow for more space to provide supporting evidence for the topic sentence.

Deciding on the length of paragraphs in an article can be done by first thinking about the intended audience, the purpose of the article, as well as the nature of the information to be communicated.

A fun activity to practice paragraphing is to organize your students into groups and provide them with a copy of an article with the original paragraph breaks removed. In their groups, students read the article and decide on where they think the paragraphs should go.

To do this successfully, they’ll need to consider the type of publication they think the article is intended for, the purpose of the article, the language level, and the nature of the information.

When the groups have finished adding in their paragraph breaks they can share and compare their decisions with the other groups before you finally reveal where the breaks were in the original article.

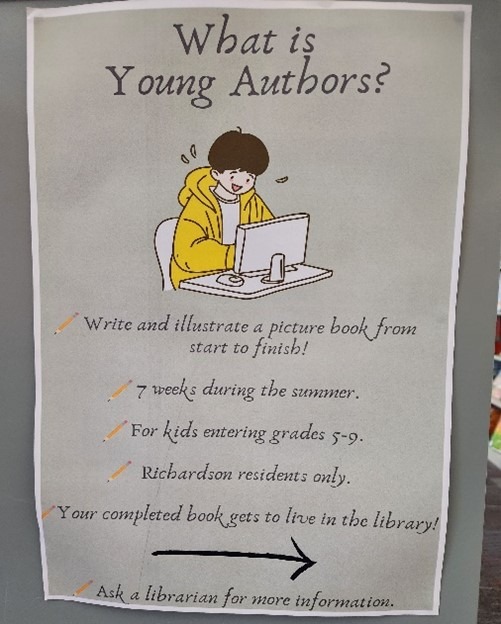

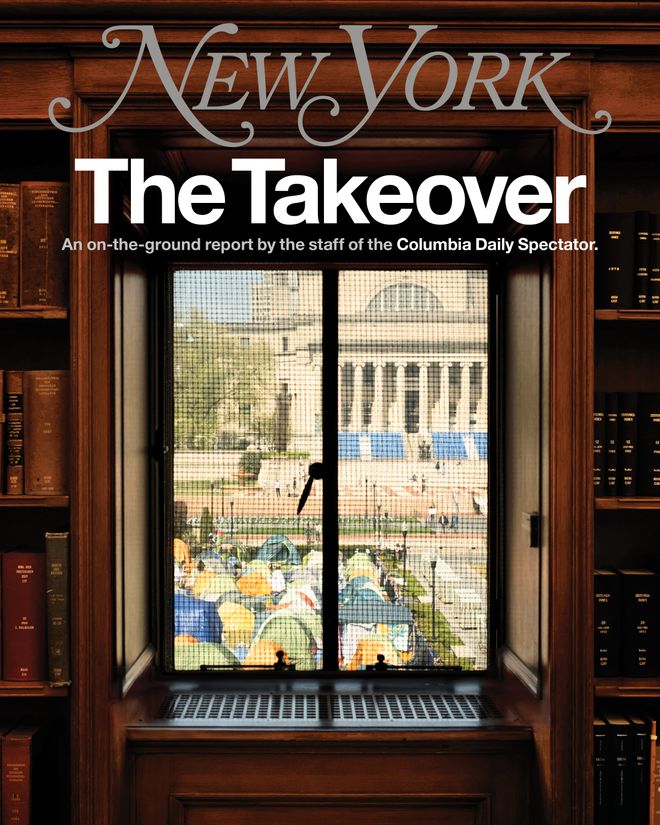

Article Photos and Captions

Photos and captions aren’t always necessary in articles, but when they are, our students must understand how to make the most of them.

Just like the previous key features on our list, there are specific things students need to know to make the most of this specific aspect of article writing.

The internet has given us the gift of access to innumerable copyright-free images to accompany our articles, but what criteria should students use when choosing an image?

To choose the perfect accompanying image/s for their article, students need to identify images that match the tone of their article.

Quirky or risque images won’t match the more serious tone of an academic article well, but they might work perfectly for that feature of tattoo artists.

Photos are meant to bring value to an article – they speak a thousand words after all. It’s important then that the image is of a high enough resolution that the detail of those ‘thousand words’ is clearly visible to the reader.

Just as the tone of the photo should match the tone of the article, the tone of the caption should match the tone of the photo.

Captions should be informative and engaging. Often, the first thing a reader will look at in an article is the photos and then the caption. Frequently, they’ll use the information therein to decide whether or not they’ll continue to read.

When writing captions, students must avoid redundancy. They need to add information to that which is already available to the reader by looking at the image.

There’s no point merely describing in words what the reader can clearly see with their own two eyes. Students should describe things that are not immediately obvious, such as date, location, or the name of the event.

One last point, captions should be written in the present tense. By definition, the photo will show something that has happened already. Despite this, students should write as if the action in the image is happening right now.

Remind students that their captions should be brief; they must be careful not to waste words with such a tight format.

For this fun activity, you’ll need some old magazines and newspapers. Cut some of the photos out minus their captions. All the accompanying captions should be cut out and jumbled up. It’s the students’ job to match each image with the correct accompanying caption.

Students can present their decisions and explanations when they’ve finished.

A good extension exercise would be to challenge the students to write a superior caption for each of the images they’ve worked on.

TOP 5 TIPS FOR ARTICLE WRITING

Now your students have the key features of article writing sewn up tightly, let’s take a look at a few quick and easy tips to help them polish up their general article writing skills.

1. Read Widely – Reading widely, all manner of articles, is the best way students can internalize some of the habits of good article writing. Luckily, with the internet, it’s easy to find articles on any topic of interest at the click of a mouse.

2. Choose Interesting Topics – It’s hard to engage the reader when the writer is not themselves engaged. Be sure students choose article topics that pique their own interest (as far as possible!).

3. Research and Outline – Regardless of the type of article the student is writing, some research will be required. The research will help an article take shape in the form of an outline. Without these two crucial stages, articles run the danger of wandering aimlessly and, worse still, of containing inaccurate information and details.

4. Keep Things Simple – All articles are about communicating information in one form or another. The most effective way of doing this is to keep things easily understood by the reader. This is especially true when the topic is complex.

5. Edit and Proofread – This can be said of any type of writing, but it still bears repeating. Students need to ensure they comprehensively proofread and edit their work when they’ve ‘finished’. The importance of this part of the writing process can’t be overstated.

And to Conclude…

With time and plenty of practice, students will soon internalize the formula as outlined above.

This will enable students to efficiently research, outline, and structure their ideas before writing.

This ability, along with the general tips mentioned, will soon enable your students to produce well-written articles on a wide range of topics to meet the needs of a diverse range of audiences.

HUGE WRITING CHECKLIST & RUBRIC BUNDLE

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ (92 Reviews)

TUTORIAL VIDEO ON HOW TO WRITE AN ARTICLE

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

How to Write a Magazine Article

Last Updated: October 11, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Gerald Posner . Gerald Posner is an Author & Journalist based in Miami, Florida. With over 35 years of experience, he specializes in investigative journalism, nonfiction books, and editorials. He holds a law degree from UC College of the Law, San Francisco, and a BA in Political Science from the University of California-Berkeley. He’s the author of thirteen books, including several New York Times bestsellers, the winner of the Florida Book Award for General Nonfiction, and has been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in History. He was also shortlisted for the Best Business Book of 2020 by the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing. There are 7 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 932,382 times.

Magazine articles can be a big boost for seasoned freelance writers or writers who are trying to jump-start their writing careers. In fact, there are no clear qualifications required for writing magazine articles except for a strong writing voice, a passion for research, and the ability to target your article pitches to the right publications. Though it may seem like magazines may be fading in the digital age, national magazines continue to thrive and can pay their writers $1 a word. [1] X Research source To write a good magazine article, you should focus on generating strong article ideas and crafting and revising the article with high attention to detail.

Generating Article Ideas

- Check if the bylines match the names on the masthead. If the names on the bylines do not match the masthead names, this may be an indication that the publication hires freelance writers to contribute to its issues.

- Look for the names and contact information of editors for specific areas. If you’re interested in writing about pop culture, identify the name and contact information of the arts editor. If you’re more interested in writing about current events, look for the name and contact information of the managing editor or the features editor. You should avoid contacting the executive editor or the editor-in-chief as they are too high up the chain and you will likely not interact with them as a freelance writer.

- Note recent topics or issues covered in the publication and the angle or spin on the topics. Does the publication seem to go for more controversial takes on a topic or a more objective approach? Does the publication seem open to experimentation in form and content or are they more traditional?

- Look at the headlines used by the publication and how the articles begin. Note if the headlines are shocking or vague. Check if the articles start with a quote, a statistic, or an anecdote. This will give you a good sense of the writing style that gets published in that particular publication.

- Note the types of sources quoted in the articles. Are they academic or more laymen? Are there many sources quoted, or many different types of sources quoted?

- Pay attention to how writers wrap up their articles in the publication. Do they end on a poignant quote? An interesting image? Or do they have a bold, concluding thought?

- These inspiring conversations do not need to be about global problems or a large issue. Having conversations with your neighbors, your friends, and your peers can allow you to discuss local topics that could then turn into an article idea for a local magazine.

- You should also look through your local newspaper for human interest stories that may have national relevance. You could then take the local story and pitch it to a magazine. You may come across a local story that feels incomplete or full of unanswered questions. This could then act as a story idea for a magazine article.

- You can also set your Google alerts to notify you if keywords on topics of interest appear online. If you have Twitter or Instagram, you can use the hashtag option to search trending topics or issues that you can turn into article ideas.

- For example, rather than write about the psychological problems of social media on teenagers, which has been done many times in many different magazines, perhaps you can focus on a demographic that is not often discussed about social media: seniors and the elderly. This will give you a fresh approach to the topic and ensure your article is not just regurgitating a familiar angle.

Crafting the Article

- Look for content written by experts in the field that relates to your article idea. If you are doing a magazine article on dying bee populations in California, for example, you should try to read texts written by at least two bee experts and/or a beekeeper who studies bee populations in California.

- You should ensure any texts you use as part of your research are credible and accurate. Be wary of websites online that contain lots of advertisements or those that are not affiliated with a professionally recognized association or field of study. Make sure you check if any of the claims made by an author have been disputed by other experts in the field or have been challenged by other experts. Try to present a well-rounded approach to your research so you do not appear biased or slanted in your research.

- You can also do an online search for individuals who may serve as good expert sources based in your area. If you need a legal source, you may ask other freelance writers who they use or ask for a contact at a police station or in the legal system.

- Prepare a list of questions before the interview. Research the source’s background and level of expertise. Be specific in your questions, as interviewees usually like to see that you have done previous research and are aware of the source’s background.

- Ask open-ended questions, avoid yes or no questions. For example, rather than asking, "Did you witness the test trials of this drug?" You can present an open-ended question, "What can you tell me about the test trials of this drug?" Be an active listener and try to minimize the amount of talking you do during the interview. The interview should be about the subject, not about you.

- Make sure you end the interview with the question: “Is there anything I haven’t asked you about this topic that I should know about?” You can also ask for referrals to other sources by asking, “Who disagrees with you on your stance on this issue?” and “Who else should I talk to about this issue?”

- Don’t be afraid to contact the source with follow-up questions as your research continues. As well, if you have any controversial or possibly offensive questions to ask the subject, save them for last.

- The best way to transcribe your interviews is to sit down with headphones plugged into your tape recorder and set aside a few hours to type out the interviews. There is no short and quick way to transcribe unless you decide to use a transcription service, which will charge you a fee for transcribing your interviews.

- Your outline should include the main point or angle of the article in the introduction, followed by supporting points in the article body, and a restatement or further development of your main point or angle in your conclusion section.

- The structure of your article will depend on the type of article you are writing. If you are writing an article on an interview with a noteworthy individual, your outline may be more straightforward and begin with the start of the interview and move to the end of the interview. But if you are writing an investigative report, you may start with the most relevant statements or statements that relate to recent news and work backward to the least relevant or more big picture statements. [10] X Research source

- Keep in mind the word count of the article, as specified by your editor. You should keep the first draft within the word count or just above the word count so you do not lose track of your main point. Most editors will be clear about the required word count of the article and will expect you not to go over the word count, for example, 500 words for smaller articles and 2,000-3,000 words for a feature article. Most magazines prefer short and sweet over long and overly detailed, with a maximum of 12 pages, including graphics and images. [11] X Research source

- You should also decide if you are going to include images or graphics in the article and where these graphics are going to come from. You may contribute your own photography or the publication may provide a photographer. If you are using graphics, you may need to have a graphic designer re create existing graphics or get permission to use the existing graphics.

- Use an interesting or surprising example: This could be a personal experience that relates to the article topic or a key moment in an interview with a source that relates to the article topic. For example, you may start an article on beekeeping in California by using a discussion you had with a source: "Darryl Bernhardt never thought he would end up becoming the foremost expert on beekeeping in California."

- Try a provocative quotation: This could be from a source from your research that raises interesting questions or introduces your angle on the topic. For example, you may quote a source who has a surprising stance on bee populations: "'Bees are more confused than ever,' Darryl Bernhart, the foremost expert in bees in California, tells me."

- Use a vivid anecdote: An anecdote is a short story that carries moral or symbolic weight. Think of an anecdote that might be a poetic or powerful way to open your article. For example, you may relate a short story about coming across abandoned bee hives in California with one of your sources, an expert in bee populations in California.

- Come up with a thought provoking question: Think of a question that will get your reader thinking and engaged in your topic, or that may surprise them. For example, for an article on beekeeping you may start with the question: "What if all the bees in California disappeared one day?"

- You want to avoid leaning too much on quotations to write the article for you. A good rule of thumb is to expand on a quotation once you use it and only use quotations when they feel necessary and impactful. The quotations should support the main angle of your article and back up any claims being made in the article.

- You may want to lean on a strong quote from a source that feels like it points to future developments relating to the topic or the ongoing nature of the topic. Ending the article on a quote may also give the article more credibility, as you are allowing your sources to provide context for the reader.

Revising the Article

- Having a conversation about the article with your editor can offer you a set of professional eyes who can make sure the article fits within the writing style of the publication and reaches its best possible draft. You should be open to editor feedback and work with your editor to improve the draft of the article.

- You should also get a copy of the publication’s style sheet or contributors guidelines and make sure the article follows these rules and guidelines. Your article should adhere to these guidelines to ensure it is ready for publication by your deadline.

- Most publications accept electronic submissions of articles. Talk with your editor to determine the best way to submit the revised article.

Sample Articles

Expert Q&A

You Might Also Like

Expert Interview

Thanks for reading our article! If you'd like to learn more about writing an article, check out our in-depth interview with Gerald Posner .

- ↑ http://grammar.yourdictionary.com/grammar-rules-and-tips/tips-on-writing-a-good-feature-for-magazines.html

- ↑ https://www.writersdigest.com/writing-articles/20-ways-to-generate-article-ideas-in-20-minutes-or-less

- ↑ http://www.writerswrite.com/journal/jun03/eight-tips-for-getting-published-in-magazines-6036

- ↑ http://www.thepenmagazine.net/20-steps-to-write-a-good-article/

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0R5f2VV58pw

- ↑ https://www.writersdigest.com/write-better-nonfiction/how-many-different-kinds-of-articles-are-there

- ↑ http://libguides.unf.edu/c.php?g=177086&p=1163719

About This Article

To write a magazine article, start by researching your topic and interviewing experts in the field. Next, create an outline of the main points you want to cover so you don’t go off topic. Then, start the article with a hook that will grab the reader’s attention and keep them reading. As you write, incorporate quotes from your research, but be careful to stick to your editor’s word count, such as 500 words for a small article or 2,000 words for a feature. Finally, conclude with a statement that expands on your topic, but leaves the reader wanting to learn more. For tips on how to smoothly navigate the revision process with an editor, read on! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Smriti Chauhan

Sep 20, 2016

Did this article help you?

Jasskaran Jolly

Sep 1, 2016

Emily Jensen

Apr 5, 2016

May 5, 2016

Ravi Sharma

Dec 25, 2016

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Develop the tech skills you need for work and life

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

FreelanceWriting

Established Since 1997

Freelance Writing Jobs

Writing contests, make money writing, hottest topics, how to write an article for a student magazine.

As with any magazine article, the key to writing one for students is to pick a topic that will capture their interest, and thus is relevant to their situation.

Give your writing a personality

In a nutshell, work, money and travel all fit the bill in this sense, but within each of these broad themes lie a wealth of more specific ideas on which you can expand. Whether you’re currently a student yourself, or it’s been years since you attended a lecture, a good starting point is to see if you can draw on your own experience as this will provide immediate material first-hand, and writing from a personal slant often proves more inspiring than a factual piece from a purely objective viewpoint.

Describe your interesting experiences

For example, there may be aspects of your job that you could talk about in terms of career advice for students eager to work in a similar profession. Have you recently been on a gap year and feel your experience might motivate others to pursue similar options? Or perhaps you have a host of top tips to offer on the best way to manage money?

Since many of these subjects are already well-covered in student literature, an original approach is vital to holding your readers’ attention. Through the importance they attach to the latest trends, students tire quickly of anything run-of-the-mill and that applies not just to what you are talking about but also how you say it. Especially if you are writing about a well-worn topic, steer clear of clichés and giving the impression that they have heard it all before.

How about tackling your article from an unconventional perspective – talking about a summer job abroad by focusing on the relational and the benefits that can bring to bear on continuing studies, rather than merely the practical. Have you been responsible for hiring new recruits?

In which case why not present your guidance on what makes a good CV in the very format of a CV? Considering the huge role played by instant, online communication in student life today, could you spice up your words of wisdom on simple ways to save money by telling them through a student’s weekly status updates on Facebook?

Remember that, in their spirit of independence, students ultimately want to make up their own minds. So no matter how clear-cut you wish your counsel to be, subtle assistance conveyed in an entertaining, natural manner will make a much more positive impression than an in-your-face here’s-how.

Although the vast majority of students are in the 18-24 age bracket, the economic downturn is pushing up the numbers of mature students seeking a career change. This not only gives rise to new article ideas (juggling part-time studies, work and family for example), but also makes the tone of your writing all the more important. Avoid imbuing your message with a know-all or know-best attitude.

Your best source of inspiration – and approval for your idea – is today’s students themselves. Ask them what they’d like to read about, it’s a simple as that!

Reader Interactions

Related articles.

How to Write 'About Us' Pages that Engage Readers

About Us pages can be a wonderful opportunity to make a company or organization shine but most of them are too often wasted words on a page that no one...

Freelance Writing for Tech Startups

By providing quality content, startup companies get the boost they require to catch up with other existing companies or startups that have had a headstart.

How I Broke into Freelance Writing Based on One Idea

Everyone has a story about how they began their freelance writing career. Learn how to do the same from the experiences of one successful writer.

Freelance Writing for Pregnancy and Baby Magazines

The parenting writing niche is ripe with opportunity. Here are some useful tips to successfully approach pregnancy, baby, and parenting publications.

Submit New Contest

You can pick more than one

How can people enter your contest? Choose the best option.

Thanks for your submission!

FreelanceWriting.com hosts some of the most talented freelance writers on the web, so you’ve come to the right place to find contestants. We are proud to post your contest here, free of charge. Please come back and submit a new contest anytime!

Submit New Job

Choose the best option.

We only accept jobs that pay. When posting a job ad, you MUST include a salary, payment terms, or rate, otherwise we will reject your ad.

If you want make a change or wish to remove your job ad in the future, please email [email protected]

We strive to be the best source of freelance writing jobs on the web, and we maintain our quality thanks to employers like you. Please continue to submit jobs early and often!

Resources you can trust

Writing a magazine article

A useful overview for students learning how to write a magazine article, perfect for GCSE English Language non-fiction writing.

This resource is designed to support students in planning for article writing activities, including coming up with great article ideas, considerations about the right target audience for their creative writing and honing their writing style.

Packed with supportive writing tips to inspire students with their article or 'story' idea, this resource helps students to focus on the appropriate language, style and tone for their readership. It can also shape their responses in terms of writing about current events in a feature article.

Students will benefit from this step-by-step guide, particularly if they are interested in a future career as a magazine writer or blogger. It can also help students who might want to write for a local newspaper or launch a writing career in creative writing or copywriting.

More GCSE writing style resources to help develop students’ writing skills are available to browse, including additional creative writing and article writing resources.

An extract from the resource:

Your article should include:

An eye-catching headline which may include a pun, an abbreviation or an ambiguity. The task is to arouse the reader’s interest so a question might work. Do not make it too long.

The opening

A key sentence, which is, in effect, a summary of the main theme of the article and which will often contain the essential facts. Make it clear to the reader how you are connected to the issue and your view of the issue. You could begin by reliving an experience. Once you have stated it, you start again at the beginning of your information and work through to the end.

All reviews

Have you used this resource?

Resources you might like

Structure of a Magazine Article: The Full Guide

The complete guide to the structure of a magazine article offers an in-depth look at creating enthralling magazine pieces, keeping the structure of a magazine article in focus.

Table of Contents

This comprehensive resource emphasizes the importance of mastering key elements to captivate your audience and produce high-quality content that effectively showcases the structural aspects of a well-crafted magazine article.

Introduction to the Structure of a Magazine Article: Laying the Foundation

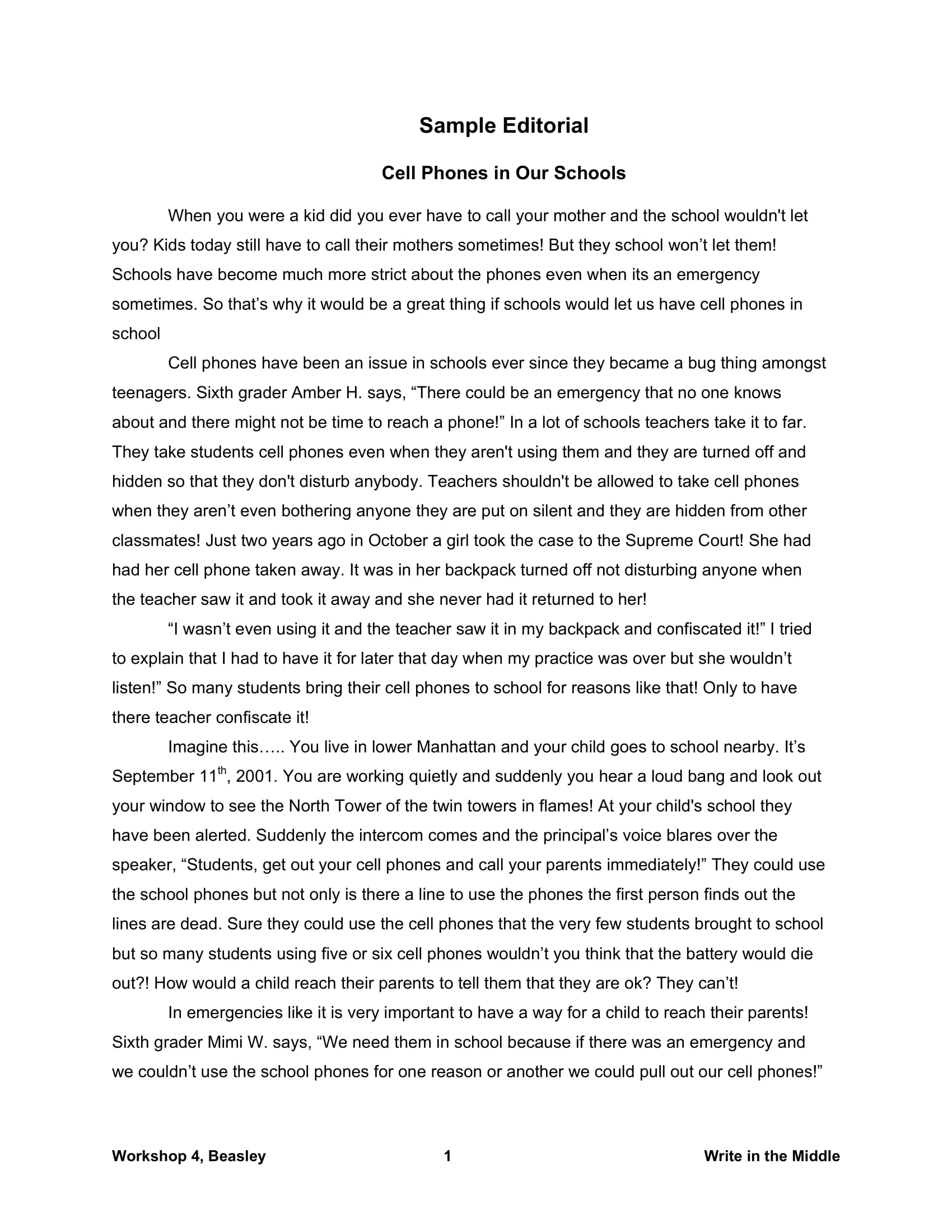

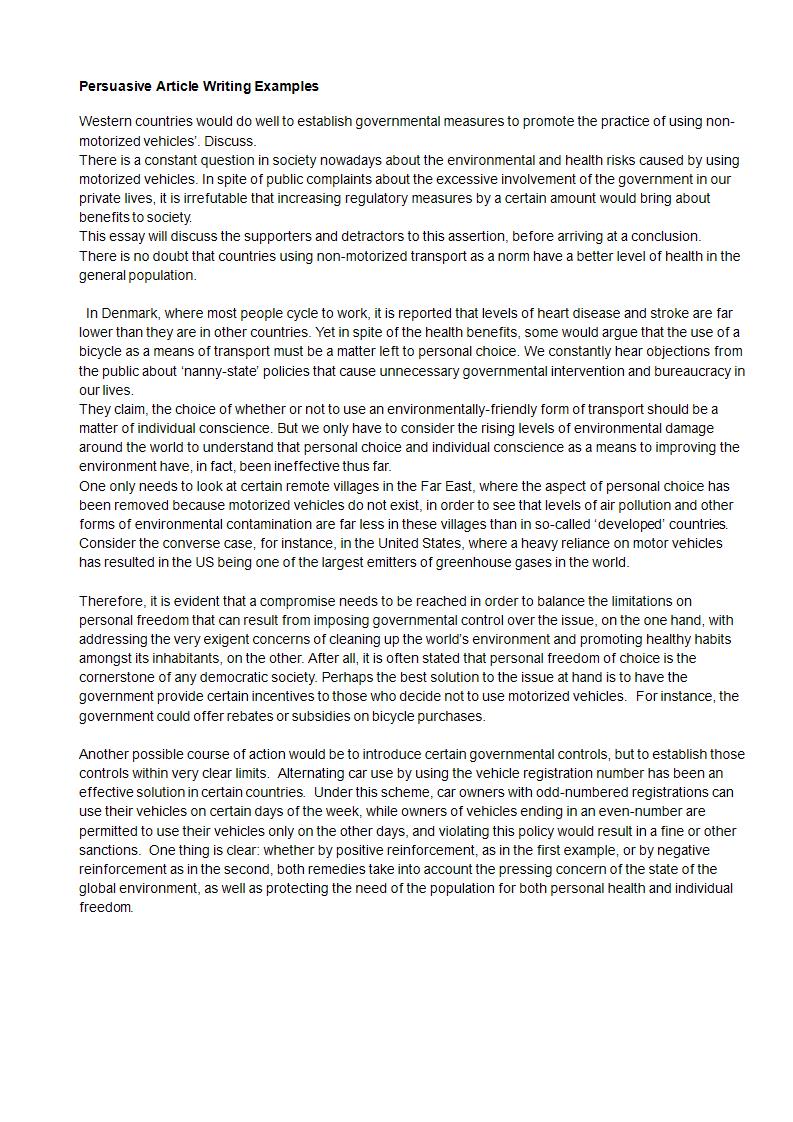

Instead of a standard article, a magazine editorial often presents the writer’s opinion on a particular subject or issue. Although the content may be subjective, the structure of a magazine editorial should still follow a coherent and logical pattern. This ensures readers can easily follow the author’s argument and find the piece enjoyable.

The structure of a magazine editorial generally consists of several key components, including an attention-grabbing headline, an engaging lead, a well-organized body, and a firm conclusion. Each element plays a vital role in capturing the reader’s interest and effectively conveying the message.

The headline should be succinct yet powerful enough to pique the reader’s curiosity. It sets the tone for the entire editorial and helps readers decide whether to engage with the content further. A captivating lead follows the headline, briefly introducing the topic and drawing the reader into the heart of the editorial.

The body of the magazine editorial is where the author develops their argument or opinion. It is essential to present the information logically and coherently, using clear headings and subheadings to guide the reader through the narrative. Including compelling evidence, anecdotes, or quotes can also strengthen the writer’s argument and keep the reader interested.

Finally, a firm conclusion should summarize the editorial, summarizing the key points and providing a clear call to action or a thought-provoking statement. This creates a lasting impact on the reader and promotes further engagement with the topic.

Understanding the structure of a magazine editorial is vital for creating impactful and engaging content. By mastering the art of crafting powerful headlines, captivating leads, coherent body text, and firm conclusions, you can establish the groundwork for a successful magazine article that resonates with your audience and leaves a lasting impression.

Structure of a Magazine Article: Crafting Engaging Headlines and Subheadings

The power of an engaging headline and well-crafted subheadings cannot be understated when it comes to the success of a magazine article. These elements are instrumental in capturing the reader’s attention and guiding them through the content, playing a significant role in the overall magazine structure.

An enticing headline is the first point of contact between the reader and the article, and it can either facilitate or hinder their decision to delve further into the content. It should be short, impactful, and thought-provoking, effectively conveying the article’s essence in just a few words. Writing a captivating headline involves striking a balance between being informative and intriguing while remaining true to the subject.

Subheadings, on the other hand, break up the body of the article into digestible sections, making it easier for the reader to navigate through the content. They provide a clear roadmap of the article’s main points, helping the reader understand the flow of ideas and the magazine structure. Compelling subheadings should be concise, informative, and engaging, enticing the reader to continue reading and ensuring they can quickly grasp the key points being discussed.

In addition to their practical purposes, headlines and subheadings also contribute to the overall visual appeal of a magazine article. They help create a sense of hierarchy and organization, essential for maintaining the reader’s interest and making the content more accessible. By using varying font sizes, styles, and formatting techniques, designers can further emphasize the importance of these elements and enhance the article’s overall aesthetic.

Engaging headlines and subheadings are crucial to the magazine structure, serving functional and aesthetic purposes. By mastering the art of crafting these essential elements, writers and designers can ensure their magazine articles capture the reader’s attention, provide a straightforward and accessible narrative, and, ultimately, leave a lasting impression.

Structure of a Magazine Article: How to Hook Your Readers from the Start

In magazine writing, the lead is crucial in captivating readers from the outset. Serving as the opening paragraph, it establishes the foundation for the remainder of the content and is a vital component in the structure of articles. A well-crafted lead piques the reader’s interest and encourages them to continue reading the entire piece.

The primary objective of a leader is to provide a glimpse into the central theme or argument of the article while leaving the reader wanting more. It should be engaging, concise, and informative, offering just enough information to entice the reader without giving away all the details. Striking the right balance between mystery and clarity is essential in creating a compelling lead that successfully hooks readers.

The structure of articles often varies depending on the subject matter and the target audience. Nevertheless, there are several tried-and-true approaches to crafting compelling leads. One such approach is the anecdotal lead, which opens with a captivating story or personal experience that sets the tone for the article. Another popular option is the question lead, which poses a thought-provoking inquiry that piques the reader’s curiosity and encourages them to read on in search of an answer.

Regardless of the chosen approach, keeping the lead concise and relevant to the article’s central theme is essential. Additionally, the lead should transition seamlessly into the body of the article, maintaining a logical flow that maintains the reader’s interest and involvement in the content.

Structure of a Magazine Article: Building a Compelling Narrative

In magazine writing, the body text forms the backbone of the article, providing the substance and depth required to convey the author’s message or argument effectively. Drawing inspiration from magazine editorial examples can help writers build a compelling narrative that keeps readers engaged and maintains their interest throughout the article.

One of the essential aspects of crafting a captivating body text is maintaining a clear and coherent structure. This can be achieved by using subheadings to break the content into smaller, digestible sections, making it easier for readers to follow the narrative and absorb the information presented. Magazine editorial examples often demonstrate how effective subheadings can guide the reader through the article, ensuring they can easily comprehend the key points and arguments.

Another critical aspect of constructing an engaging body text is to vary the sentence structure and maintain a natural, conversational tone. This helps the content feel more approachable and enjoyable to read, as opposed to overly formal or rigid. Examining magazine editorial examples can provide valuable insights into how experienced writers maintain a consistent voice and style throughout their articles, fostering a connection with the reader and making the content more relatable.

Furthermore, using compelling evidence, anecdotes, quotes, or statistics can significantly enhance the credibility and impact of the body text. These elements not only lend weight to the author’s arguments but also help to keep the reader’s interest piqued, encouraging them to continue reading and engage with the content more deeply.

Structure of a Magazine Article: Visual Elements and Their Role

In magazine publishing, visual elements play a vital role in enhancing the reader’s experience and contributing to the overall structure of an article. As the adage states, “A picture is worth a thousand words,” and this concept holds true when considering the structure of an article. Images, graphics, and other visual components can bring the written content to life, adding depth, context, and appeal to the magazine piece.

Functions of Visual Elements

One of the primary functions of visual elements in a magazine article is to break up large blocks of text, making the content more digestible and visually appealing. By incorporating relevant images or graphics throughout the article, writers and designers can create a more engaging and enjoyable reading experience for the audience. This not only makes the content more accessible but also helps to maintain the reader’s interest and attention.

Another essential function of visual elements is to provide additional context or information that may be difficult to convey through text alone. For example, data visualizations, such as charts or infographics , can effectively present complex information or statistics in a more easily understandable format. This enhances the reader’s comprehension of the subject matter and strengthens the overall impact of the article.

Furthermore, visual elements can also contribute to a magazine article’s overall aesthetic and design. By strategically using color, typography, and other design elements, designers can create a cohesive visual language that complements the written content and reflects the article’s theme or mood. This adds to the reader’s enjoyment and reinforces the magazine’s brand identity and style.

Understanding the structure of an article is complete by considering the role of visual elements. By incorporating relevant images, graphics, and design elements, writers and designers can create a more engaging and visually appealing magazine piece that captures the reader’s attention and enhances their overall experience.

Structure of a Magazine Article: Crafting a Memorable Ending

A well-crafted conclusion is an essential component of any compelling magazine article. It reinforces the main points and ideas, leaving the reader with a lasting impression and closure. Understanding how to structure an article involves organizing the content logically and ensuring that the conclusion ties everything together, providing a strong and memorable finish.

When crafting a memorable ending, it is crucial to reiterate the key points discussed throughout the article, summarizing the central argument or message. However, this should be done concisely, avoiding repetition or regurgitation of information. Instead, the conclusion should offer a fresh perspective or insight that adds depth to the article and encourages readers to further reflect on the subject.

Another effective technique when considering how to structure an article is to end with a call to action, a thought-provoking question, or a prediction. This can inspire the reader to engage with the topic beyond the article, fostering a sense of curiosity and leaving them with something to ponder. The conclusion can impact the reader by provoking an emotional response or encouraging further exploration.

In addition, the tone of the conclusion should be consistent with the rest of the article, maintaining a sense of cohesion and harmony. Whether the article is informative, persuasive, or narrative-driven, the conclusion should reflect the same style and voice, ensuring a smooth and satisfying reading experience.

Mastering how to structure an article involves organizing the content effectively and crafting a powerful and memorable conclusion. By summarizing the key points, offering fresh insights, and provoking thought or action, writers can ensure that their magazine articles resonate with readers and leave a lasting impact. By incorporating these techniques, you can create a compelling, engaging magazine article that stands out.

What are the critical components of a magazine article structure?

The critical components of a magazine article structure include an attention-grabbing headline, an engaging lead, a well-organized body, and a firm conclusion.

How do I write a captivating headline for my magazine article?

A captivating headline should be short, impactful, and thought-provoking, conveying the article’s essence in just a few words. Strive to balance being informative and intriguing while remaining true to the subject.

What role do subheadings play in the structure of a magazine article?

Subheadings break up the body of the article into digestible sections, making it easier for the reader to navigate through the content. They provide a clear roadmap of the article’s main points, helping the reader understand the flow of ideas and the magazine structure.

How can I write an engaging lead for my magazine article?

To write an engaging lead, provide a glimpse into the central theme or argument of the article while leaving the reader wanting more. Keep it concise and relevant to the article’s theme, striking the right balance between mystery and clarity.

What are some tips for crafting a compelling body text?

Craft a compelling body text, maintain a clear and coherent structure, vary sentence structure, and maintain a natural, conversational tone. Use subheadings, compelling evidence, anecdotes, quotes, or statistics to enhance the credibility and impact of the content.

Learn How To Develop Launch-Ready Creative Products

Download How to Turn Your Creativity into a Product, a FREE starter kit.

Advertisement

Create a Memorable Social Media Experience

Get the content planner that makes social media 10x easier.

Invite Your Customers To A Whole New World

Create a unique user experience.

Maximize Your Brand and Make Your Mark

Custom brand assets will take you to new heights.

Side Hustle: How to Balance with Full-time Work

Niche Markets: How to Integrate Customer Feedback

Business Ideas in Tech: How to Find Potential

Headlines: How to Craft for Social Media

Email Marketing vs. SMS Marketing: How to Choose

Side Hustle: How to Start One from Home

How to Write a Compelling School Magazine Article People Want to Read

- Writing Tips

Say what you want about traditional school communications, but no matter how trends shift and change, there are some staples that will always hold a special place in school storytelling.

For example: the school magazine.

Whether an alumni magazine, an annual report/magazine hybrid, or an online version of a traditional publication, school magazines have the important job of both keeping legacy alive and documenting current happenings for posterity — all while driving diverse audiences to take action.

That’s quite a job description.

I’ve seen beautiful, impressive magazines in the school marketing space, and my clients dedicate both their hearts and their resources to perfecting these publications and maintaining their integrity year after year. So how can school marketers ensure these intense efforts create tangible results? How can schools better utilize this important communications tool to connect with their communities and grow school influence?

Here’s how to craft school magazine content that makes all the effort worthwhile.

Recommended Resource: Audience-First Storytelling Kit

ACCESS NOW ON-DEMAND

Want to learn exactly how to win over dream families with breakthrough school storytelling? This on-demand kit includes instant access to:

- In-depth video workshop

- Workshop workbook

- Family survey template

- Email template

- Voice of Customer research spreadsheet

- Audience persona template

- Sample dream family persona

The key to ensuring people are reading the school magazine you put so much time, effort, and love into is simple:

Make it something they want to read.

Ok, I know that’s simpler to state than to practice, but the sentiment is something that is so easy to forget when we’re deep in deadlines and page counts and design changes.

If we want readers to open our school magazine and actually flip from front to back, engaging with the stories we’re telling, we need to give them stories they care about . We need to make the news, updates, changes, and reflections shared on those pages matter to their lives. And how do we do that?

Audience-first, always.

Those who have been reading this blog for a while may have guessed where I was going with that, but it’s always where I begin when I’m writing feature school magazine articles. I look at the story or concept that my client wants to share and ask myself, “ So what? Why will the reader care about this? What about this will they find most interesting, or appealing, or shocking? What will capture and keep their fickle interest?”

You may have a wonderful story to tell, important updates to deliver, or a heartwarming retrospective to share, but just because you want to tell it doesn’t mean your audience wants to read it. However, you can entice them to read it if you write with their cares and concerns in mind.

For alumni, perhaps that means tugging at their heartstrings and reminding them of a special moment in their lives, or it’s giving them the opportunity to see themselves in the school’s future. For donors, it could be demonstrating the tangible difference their generosity has made. For current families, it may be updating them on new opportunities that will have a direct impact on their child’s life.

Whatever the article topic, make sure you have your specific audience in mind before you put pen to paper (or fingertips to keyboard). And once you begin writing…

Hook them quick.

Repeat after me: NO MORE BORING HEADLINES.

Too often, school feature articles are given a title such as, “A Look Back!” or “Celebrating the Graduating Class” or “Our Theatre Program!” While factually correct, these headlines don’t connect with the reader’s desire to learn more, or answer a question, or find out how or why.

Instead of using a headline as a label, try writing your school magazine article headlines with these tips in mind:

- Be specific. Tell people the problem you are going to solve and the solution you are going to provide. Use figures and facts.

- Promise your reader something valuable. Be bold, and deliver on that promise.

- Make sure it stands alone. If readers only read the headline, will they take away a clear message?

- Be clear. Avoid being creative if it costs you clarity.

- Prompt action. Convey a sense of urgency.

For example, I recently used the headline “A Call to Excellence for Generations of [School] Students” on an article that spoke about the history of the school’s motto (a much more compelling headline than “The History of Our Motto.”). By connecting the reader to the motto and what it meant to them as a student and now as an alum, the headline drew the reader into an article they might have otherwise overlooked.

However, a good headline can’t do all the work. An article’s intro is equally as important.

Engage them with a story.

Consider this your permission to stop being so literal. Instead of jumping right into the main point of the article, paint a picture. Draw the reader in. Get them thinking, imagining, questioning.

This is how I approached one recent feature article for a client, which was supposed to be a simple “then/now” retrospective. Instead of diving in with an introduction that read, “So much has changed in the past 10 years…,” I decided to talk about nostalgia . How does it affect us? Why do we feel it so deeply? The article began:

Have you ever heard a forgotten song from childhood and felt instantly transported back to a specific moment in time? Caught the lingering scent of pine trees or felt the leaves crunch underfoot in just the right way, and you’re suddenly sixteen again, walking across your high school quadrangle on the way to AP Bio class?

By prompting the reader to mind-travel back to their high school years, the article instantly connects on both an emotional and rational level. It then goes on to briefly talk about the science behind nostalgia and links that to why the school’s heritage and legacy are meaningful today. The final article does everything a traditional retrospective would — it provides updates, reports statistics, and talks about the future — yet in a way that’s more engaging than a typical timeline.

Keep the meaningful. Cut the rest.

William Faulkner said: “In writing, you must kill all your darlings.” And then Stephen King took it up a notch, saying: “Kill your darlings, kill your darlings, even when it breaks your egocentric little scribbler’s heart, kill your darlings.”

It’s the best writing advice I’ve ever heard.

If you want to write a fantastic school magazine, you need to be willing to cut, delete, and forget elements that you may love but that may not serve the reader. This means that not every point on the timeline, every update on the program, every key message from the strategic plan can and should make it into print.

Remember: Every article should pass the “So What?” test . Every story should be written for the reader. Keep the meaningful, and cut the rest.

Those are my top tips for writing a school magazine article that your audiences will want to read. Want more school marketing and storytelling tips? Get them FREE in our Resource Library — the ultimate collection of ebooks, worksheets, and on-demand tutorials created specifically for school marketers.

MORE ARTICLES

Set Your School Marketing Up For Success.

- Get free resources

- Work with us

- Our Mission

Honoring Student Voice and Choice With the Magazine Project

When students create a magazine about a topic of their choice, it encourages them to write and rewrite carefully.

I was talking recently with the parent of a student who was in my class nearly 15 years ago. “He still has his magazine! I know exactly where it is,” his mom said. I might be surprised that a young adult has kept an eighth-grade English assignment for over a decade, but I hear this often about my favorite activity of all time: the magazine project.

This project has evolved over the years to encompass a wide variety of skills, but originally it was designed to address one persistent frustration in the teaching of writing: How can we so thoroughly engage students in writing that they will take the time to proofread, edit, revise, and polish their work? Too often, students submit the first draft of a piece of writing and leave it at that. Close editing and revision call for a level of investment that can be difficult to inspire in young writers.

The Power of Choice

I know that letting students choose their writing topics can improve engagement , so I created a project that asks students to choose a topic of personal interest and spend most of a semester writing, designing, and publishing their own magazine on that topic. The combination of topic choice and a final published magazine greatly improves my students’ investment in their writing all semester long.

When I introduce the project, I explain to students that since they will be doing a lot of writing about that topic over the next few months, they need to choose their topic carefully. It might be a topic they already know really well, or they might choose one they want to learn more about. We brainstorm potential topics on paper, in small groups, and together as a class to help them decide on their favorite topics.

This big choice usually entices students, but many don’t believe that they really do get to choose, and they pepper me with questions:

- “Can I write about gum?” “Sure, if that’s what interests you.”

- “My whole magazine can be about gum?” “Yep. The whole thing.”

- “What about LGBTQ+ issues? Can I write about that?” “Of course. If that interests you, go for it.”

- “I love roller coasters. Can I write about that all semester?” “How fun! I can’t wait to read your magazine.”

But when a student tells me, “I would like to write about the vast enigma of space,” I am reminded that I can’t possibly anticipate what kinds of writing might engage every eighth grader, and giving them a choice is the best way to do that.

Topics range from the silly (gum) to the serious (civil rights, school safety, mental health) and everything in between (fashion, college life, travel, puppies, and, of course, the vast enigma of space). Not only does this choice mean that students will be more invested in their writing, but our classroom becomes abuzz with writers eagerly sharing ideas.

A Lesson Guide

Once they’ve been introduced to the project, I distribute a packet of directions that will guide them through the next few months. The packet has been an evolving work in progress as all the eighth-grade English teachers on our campus collaborate on the best ways to support our students through the production of their magazines.

We have found the packet to be invaluable to keep students on track whether they are at school, home with a cold, or away on a family trip. Our resource teachers also have told us they appreciate having all the directions in one place, as it helps them support our students throughout the semester. The packet includes the following:

- A list of required pieces for their magazine (essays, research notes, advertisements, letters to the editor, table of contents, front and back covers)

- Criteria for each required piece

- Brainstorm pages for topics, titles, advertisements, and captions

- A research note-taking page

- Graphic organizers for each essay

- Mentor texts for each essay

- Directions for formatting with technology

- Directions for an online magazine (optional)

- A final magazine rubric

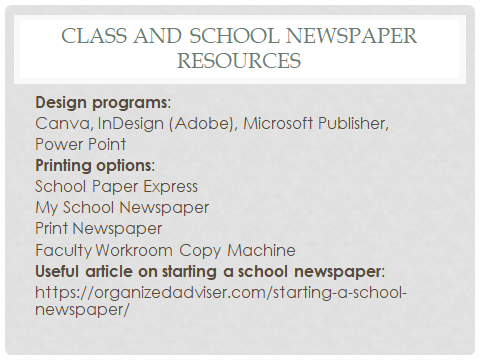

The primary focus of the project is nonfiction writing: argumentative, informative, and biographical. But since all this writing is in the context of a magazine, students also learn a host of technology and design skills, like how to search for copyright-free images, illustrate essays with pictures and captions, use Google Drawings to design page layouts, and create an online publication.

In order to support our students as they work through the many stages of the project, we set deadlines and give feedback throughout. Essays are submitted for feedback, and students are given guidelines and class time to revise their work. We break up the writing time by assigning graphic design work in between the essays. Students enjoy creating their ads and front cover, but those assignments also need feedback and revision time. We look at how magazines have ads that relate specifically to the content of the magazine, which helps students create an ad to accompany each essay they write.

Twenty-five years ago, students glued their pages onto four pieces of folded 11 x 17 paper, and I used a long-arm stapler to secure the pages through the spine, just like a real magazine. But now we give students the option of creating an online magazine. This eliminates printing expenses, while also incorporating valuable technology skills. We have used Adobe Express , Canva , and Google Sites for student magazines, and our students have been thrilled with the professional quality of their final publications.

We schedule the final due date of the magazines for a week or so prior to open house so we can have them out on display for the community to see. These student-centered, uniquely individual magazines make a powerful statement about what matters to our students, what they are learning, and how they are able to demonstrate their learning through words, images, and design. And every time I encounter a former student, they say, “Mrs. Bradley! I still have my magazine!” That kind of pride confirms for us the power of this project.

Article Writing for Students

Ai generator.

It is quite a common activity for students to write something intended for publication. That task can mean writing an article , an entry for a competition, and a review, and all possible write-ups that can be published in an English magazine. It is a good activity to harness the students’ writing skills, creativity, attention to details, and many other skills related to writing that can be beneficial to them with any career they decide to pursue.

You may think that writing these kinds of write-ups is simply just a waste of time, but contrary to that belief, this exercise helps your creative juice flowing. Aside from that, it can help improve your techniques and styles when it comes to this activity, it can also help you develop a new approach that will improve your outputs, and overall, it improves your writing skills making you a better writer in the end.

In addition, it can either be formal writing and informal writing depending on the audience. Since the article could possibly be published in a publication, it must be informative writing and must be written in an interesting or entertaining manner in order to captivate the readers’ attention and retain their interest. If you look at it in another perspective, an article is in a less formal style than that of a report since their are no needs for graphs, does not use bullet points and sections.

An article is usually written to spread information, but more than that, it also describes an event, person, experience, etc. It can also be written with the intention of sharing a balanced opinion about a certain topic. Articles are useful sources of information as well as entertainment. In a journalistic point of view, there are quite a few types of articles namely news articles, feature articles, sports articles, editorial articles, and so on. Although these articles use different approaches and have varying standards, the one thing in common about them is that they are based on facts.

Therefore, articles are factual pieces of writing that can inform, entertain, describe, persuade, etc., the readers. As mentioned, the different types of articles may enforce different standards, thus, it can either be a short or lengthy article. In addition to that, articles are the different writings you usually read in a publication.

Structure of Article Writing

An effective article is structured with a captivating introduction that grabs the reader’s attention and briefly introduces the topic. This is followed by detailed body paragraphs that present evidence, examples, and arguments to thoroughly explore the subject. Each section is seamlessly linked with transition words, ensuring a smooth flow. The article concludes with a strong summary that reiterates the key points and reinforces the article’s main message.

Format of Article Writing for Students

Captivating and Relevant: Choose a title that immediately captures the interest of the reader and gives an idea of what the article is about.

Introduction

Hook: Start with an attention-grabbing sentence or question to pique the reader’s interest. Background Information: Provide a brief overview of the topic or issue being discussed. Thesis Statement: Present the main idea or argument of your article, setting the tone for the discussion that follows.

The body is where you delve into the details of your topic. It can be structured in several paragraphs, each with a specific focus.

Subheadings: Use subheadings to break down the article into manageable sections, each addressing a specific aspect of the topic. Supporting Information: Present facts, statistics, examples, or quotes to support your main idea. Ensure the information is accurate and relevant. Visual Elements: Where appropriate, include charts, graphs, or images to complement the text and enhance understanding.

Analysis and Discussion

Personal Insight: Share your analysis or interpretation of the information. This is where you can express opinions or offer a new perspective. Counterarguments: If presenting an argument, acknowledge opposing viewpoints and offer counterarguments to show a balanced understanding of the topic.

Summary: Briefly recap the main points discussed in the article, reinforcing the thesis statement. Call to Action: Encourage the reader to think, act, or further explore the topic. This could be a question, a suggestion, or a directive. Final Thought: Leave the reader with something to ponder, which could be a thought-provoking statement or a rhetorical question.

Example of Article Writing for Students

Introduction Have you ever felt like there are not enough hours in the day? You’re not alone. Many students struggle with balancing schoolwork, extracurricular activities, and personal time. This article delves into the significance of time management for students and offers practical tips to help you make the most of your day. Understanding Time Management Time management refers to the process of organizing and planning how to divide your time between specific activities. Good time management enables students to work smarter, not harder, so that they get more done in less time, even when time is tight and pressures are high. Benefits of Effective Time Management Improved Performance: By organizing your tasks and having a clear plan, you can focus better and achieve higher quality in your work. Reduced Stress: Managing your time well decreases stress levels by removing the pressure of last-minute deadlines and cramming sessions. More Free Time: Efficient scheduling means more leisure time to spend with friends and family, pursuing hobbies, or resting. Strategies for Better Time Management Set Clear Goals: Identify what you want to achieve in your study session. Setting SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-bound) goals can help keep you focused. Create a To-Do List: List everything you need to do, and tackle tasks in order of priority. Use a Planner: A planner can help you keep track of deadlines, appointments, and when you plan to complete each task. Break Tasks into Smaller Steps: Large tasks can seem overwhelming, but breaking them down into smaller, manageable steps can make them feel more achievable. Eliminate Distractions: Identify what commonly distracts you in your study environment and try to eliminate or reduce these distractions. Practice Saying No: It’s okay to turn down additional responsibilities if you think it might interfere with your existing commitments and study time. Conclusion Time management is a crucial skill that benefits students not just academically but in all aspects of life. By implementing effective time management strategies, you can improve your productivity, reduce stress, and increase your free time. Start by integrating one or two of the strategies mentioned above and gradually incorporate more as you become comfortable. Remember, the goal is to work smarter, not harder.

Article Writing for Students Samples to Edit & Download

- Mental health awareness

- Technology in education

- Climate change action

- Diversity in schools

- Social media impact

- Study techniques

- Youth activism

- Remote learning

- Financial literacy

- Extracurricular benefits

- Arts in education

- Cyberbullying prevention

- Career exploration

- Community service

- Gender equality

- Peer pressure effects

- Mental health stigma

- Sustainable living

- Youth representation in media

- Critical thinking skills.

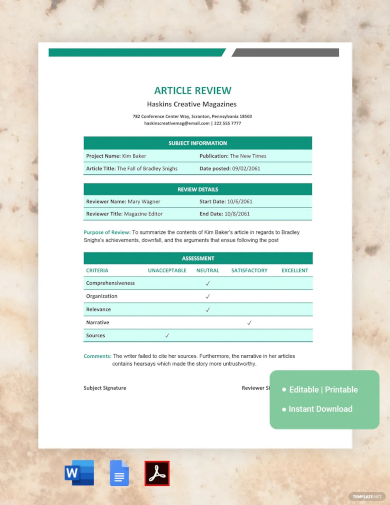

Article Writing for Students Examples & Templates

1. article review template.

2. Article Summary Template

3. Magazine Article Writing Exercises Example

4. Article Writing Worksheet Example

5. Article Examples for Students

tea.texas.gov

6. Newspaper Article Example

7. Feature Article Writing Worksheet Example

8. Short Editorial Article Example

9. Newspaper Article Format Example

10. Persuasive Article Example

11. Article for School Magazine Example

12. College Newspaper/Online Article Example

13. Sports and Academic Performance Article Example

14. Current Events Article Worksheet Example

Essential Information About Writing Articles for Students

Before you proceed in writing articles , you need to understand what makes it different from other forms of writing first. If you are not able to determine and understand what makes an article an article , you may end writing an essay or another form of writing instead. To help you with that, listed below are essential information about writing articles:

1. The reader is identified

An article is basically a direct conversation with your reader. If a portion in an exam is for you to write an article, the reader may be identified or specified as part of the instructions. That way you can write your article as if you are directly discussing your topic with them. In this sense, the tone, sentences, and words you use in your article must be conversational and easy to understand for your readers. More importantly, you need to remember that the main goal is to cater to your readers; you need to be able to spark their interest and sustain in all throughout the article.

2. It needs to be attention-getting

The main thing that sparks you readers’ interest is your title. Since the title is the first few descriptive writing words your readers will be able to read before the content of the article, it must be attention-getting, meaning, it must be catchy but still has substance. The title of your article must represent the entirety of your article, therefore, it must be accurate but at the same time interesting. After establishing a good title for your article, the content should definitely match what is in the title; it must be accurate and at the same time factual.

3. It has to be interesting

Similarly to what has been discussed above, an article needs to be interesting. Aside from being informative and factual, another goal should be to be able to maintain the readers’ interest in your content. The article must be engaging from start to finish. If you are writing an article for an exam, you must remember that your teacher has to read quite a few articles of the same main topic. You have to think of a way to make your article interesting and memorable, maybe try a new approach, use more engaging sentences; you have to find a way to make you reader want to read your article up to the last word. For example, you can add humor (if appropriate), real-life or made-up examples, or make up quotes.

4. It should be easy to read

One common mistake when writing articles is being overwhelmed by the topic and writing an entire page of monotonous rambles. Although in some cases it is necessary, like in a news or editorial article. However, there are ways when you can make it a breeze to read for your readers; for example, you can use subheadings to break up the text and make clear paragraphs. Make sure that your ideas are organized in a way that your readers can easily comprehend, you can write in a semi-informal, conversational style; however, you may want to abide to the instructions that you will be given. Remember that in an article, there is no need to reiterate the issue or topic, you really only have to explore and expand the topic to encourage your reader to read on.

5. There should be a good ending

The difference with an essay and an article is that in an essay you need to sum up the point you have made in the entire write-up in your conclusion while in an article, there is no need for that; the best way to end your article is to give the reader something to ponder even after reading the entirety of the article. Most of the time, the best endings link back to the starting point in some way. You can ask a question or some powerful or impactful sentence that will make your readers think about what they have read.

Tips to Write Good Articles for Students

By now, you basically have an idea how to write an article. However, there is quite a distinction between a mediocre and good article. To help you produce a good and effective article, listed below are some useful tips in writing good articles:

- Your opening or lead should be easy to read. Meaning it should be simple and short, but at the same time, it should also be able to provide a good overview of the article.

- Keep your paragraphs short and your text visually appealing.

- Provide context on the 5 Ws: Who, What, Where, When, and Why. Occasionally, there might be room for the How provide insightful context.

- Give meaningful substance.

- Show then tell. State or present your main goal, then explain and expand it.

- Learn to quote properly.

- Research, research, research! If there is an opportunity or the topic is already given, always do advance research.

- It’s acceptable to use semi-formal language unlike in an essay.

- Always be accurate and factual.

- Proofread and edit. Always.

Article writing is an exercise commonly practiced by students; it may not be as easy as it sounds, the skills developed with this exercise is as useful as any other skills. It has the ability to help students develop and improve their communication skills as well as harness their creativity. It may even be the starting point of a student in deciding to pursue journalism or any other course that offers the opportunity to write about significant matters. Although it is quite similar to essay writing, it is still different in a way topics are discussed and presented. We hope that you have learned something about article writing especially when this is a reoccurring exercise in your classes. The examples given above are for your own use. May it give you more knowledge about the fact and inspiration.

- Clearly defined subject matter or theme that unifies the photographs and tells a cohesive story.

- An intentional narrative structure that guides the viewer through the photo essay, whether chronological, thematic, or conceptual.

- A strong introduction that captures the viewer’s attention and sets the tone for the photo essay.

- A series of high-quality and visually compelling images that effectively convey the chosen theme or story.

- A variety of shots, including wide-angle, close-ups, detail shots, and different perspectives, to add visual interest and depth.

- Careful sequencing of images to create a logical flow and emotional impact, guiding the viewer through the narrative.

- Thoughtful captions or accompanying text that provide context, additional information, or insights, enhancing the viewer’s understanding.

- A concluding section that brings the photo essay to a satisfying close, leaving a lasting impression on the viewer.

- The incorporation of images that evoke emotions and connect with the viewer on a personal or empathetic level.

- Consideration of the audience, aiming to engage and connect with viewers by addressing universal themes or issues.

How to Write an Article for Students

1. understand your audience:.

- Consider the age group and educational level of your target audience.

- Identify their interests, concerns, and common challenges.

2. Choose a Relevant Topic:

- Select a topic that resonates with students’ experiences or addresses their needs.

- Make it interesting and relevant to their daily lives.

3. Create a Catchy Title:

- Craft a title that grabs attention and gives a clear idea of the article’s content.

- Keep it concise but intriguing.

4. Introduction:

- Start with a hook to capture the reader’s interest.

- Provide background information on the topic.

- Clearly state the purpose or main idea of the article.

5. Body Paragraphs:

- Organize your content into logical paragraphs.

- Each paragraph should focus on a specific point or subtopic.

- Use clear and simple language.

- Support your ideas with examples, anecdotes, or relevant information.