Haiku Poems: How to Write a Haiku

Sean Glatch | January 18, 2024 | 4 Comments

Haiku poems are short poems that use brevity and close observation, as well as natural imagery, to find powerful insight. Combining the restraint of short-form poetry with centuries of tradition, haiku poems are a popular form for poets both classic and contemporary, both Western and Eastern. The haiku poetry tradition is rich with history, and while many poets know about the 5-7-5 rule, they don’t know all the requirements of the haiku format—much less how to write a haiku poem.

This article looks at the history, poetics, and possibilities of haiku poems. We draw comparisons between Japanese haiku and Western/contemporary haiku poetry, with plenty of haiku examples and analysis. Finally, we make distinctions between the haiku form and the senryū, a similar Japanese form.

What is a haiku poem? How do you format it? Let’s dive into how to write a haiku poem, and first, we’ll examine the form’s long and complex history.

A Brief History of Haiku Poetry

Haiku vs. senryū, how many syllables in a haiku poem, classic vs. contemporary haiku poems, terminology of haiku poems, haiku examples, tips on how to write a haiku poem, where to submit haiku poetry, what is a haiku poem.

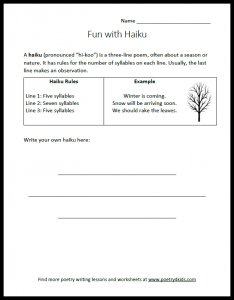

Haiku poems are short-form poems that originated in the 17th century, Japan. Traditionally, the poetry form requires the poet to arrange 17 syllables into three lines of 5, 7, and 5 syllables, respectively. Classical Japanese haiku requires the poem to use natural imagery; poems that don’t dwell on nature are called senryū.

What is a haiku poem?: a short-form poem from 17th century Japan that uses natural imagery.

Here’s an example of a haiku, from Modern Haiku’s Summer 2020 journal, from former U.S. Poet Laureate Billy Collins :

Although the classical form has strict requirements, contemporary haiku poems can be far more impressionistic and unconstrained. Let’s take a brief look at the history of haiku poetry, before turning to the rules of the haiku format.

Japanese haiku poetry evolved from several poetic traditions. Previous to the invention of the form, Japanese poets wrote waka, a form of poetry that followed a 5-7-5-7-7 syllabic format. Waka was primarily written by people of higher status, and often required countless hours of studying and crafting poetry—hours which were unavailable to the common folk.

Eventually, Japanese commoners produced their own modified form of waka, called renga (linked verse). In a renga poem, two or more poets take turns writing lines, linking those lines together in a waka. This tradition arose in dominance from the 13th to the 16th centuries, and poets like Sogi helped popularize this verse across the Japanese islands. In the 17th century, waka inspired a different form of linked verse, called haikai.

Starting in the 14th century, many linked verse poems were preceded by a hokku, or “first verse.” A hokku was a poem written in 5-7-5 which often introduced or summarized the themes of the linked poem.

Hokku eventually broke off to become its own form, the haiku. This official split did not occur until the Meiji Restoration in 1868, which opened Japan up to many countries where it had previously refused to trade or share its culture. Technically, most haiku poems preceding the Meiji Restoration are simply hokku, though some poets, like Bashō, are retrospectively considered haiku poets, as Bashō himself freed the hokku from always introducing linked verse.

The introduction of haiku poetry to the West was at first unsuccessful. However, in the 20th century, the Imagist Ezra Pound and the Jazz poet James Emanuel, alongside many French and Spanish poets, helped introduce the form to contemporary literary society. The Beat poets were similarly entranced with haiku poetry. Jack Kerouac often wrote haiku poems such as these. Allan Ginsberg, Philip Whalen, and Gary Snyder, among many other Beats, additionally stoked a certain mid-century haiku fanaticism. However, as we’ll point out later in the article, the haiku poetry of the Beat Generation was noticeably different from the more formulaic poetry of Classical Japan.

An important distinction is the difference between haiku and senryū. Senryū and haiku poems rely on the same format (described below), but differ in subject matter.

Haiku poetry dwells on nature, usually imparting wisdom about life and existence through observations of the natural world. (An exception to this is gendai , which refers to contemporary Japanese pieces that differ in values and topics from classical poetry.)

Haiku poetry dwells on nature, usually imparting wisdom about life and existence through observations of the natural world. Senryū poems dwell on the follies of human nature.

By contrast, senryū poems dwell on the follies of human nature. A senryū might make fun of certain human behaviors or limitations, and the tone of a senryū is usually humorous, cynical, or even satirical .

Additionally, senryū does not have a kireji or kigo , both of which are defined below.

Haiku Format

Traditional Japanese haiku poems are written in three lines. The first and the third lines have 5 syllables, while the second line has 7. If you’ve heard of the form before, you’re probably familiar with the haiku 5-7-5 rule. As we will discuss in a bit, contemporary examples do not have the same syllabic requirements, but most are still written in three lines.

Proper haiku poetry has three elements: a reference to nature ( kigo ), two juxtaposed images, and a kireji , or “cutting word” which marks a transition in the verse and pulls the poem together.

Proper haiku poetry has three elements: a reference to nature ( kigo ), two juxtaposed images, and a kireji , or “cutting word” which marks a transition in the verse and pulls the poem together. An individual image occupies lines 1 and 2, with the third line containing the kireji .

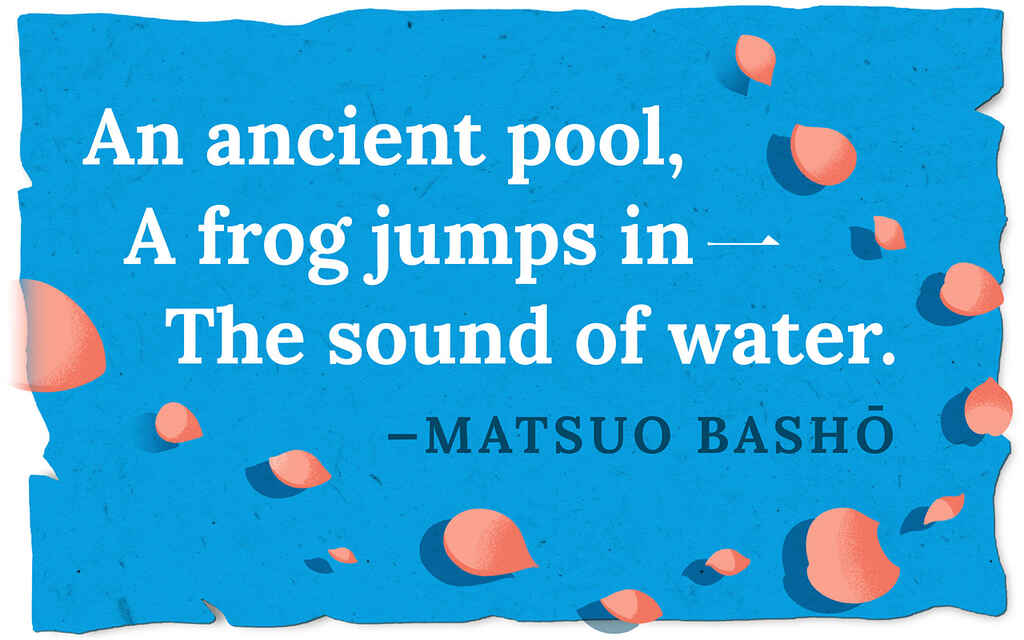

See this in action in the below poem, by Bashō:

The image in the first line is the old silent pond; the image in the second line is the frog jumping. The frog, also, is the “nature word” in the poem: frogs are traditional symbols of the springtime, and what’s lost in translation here is that the poem represents the passing of seasons, from the “old, silent” winter to the sudden arrival of spring. “Splash!” is the kireji , signifying the suddenness of seasonal transition.

Note: some English poems use punctuation, like the em dash (—), as the kireji .

If you want to learn how to write a haiku poem, practice juxtaposing simple, natural images against each other, using the final line to surprise the reader and pull the poem together.

The conventional haiku structure requires poets to write 17 syllables in 3 lines: 5, 7, and 5 again. However, as we’re about to explore, this syllabic requirement does not apply to contemporary English verse. Far more important is the philosophy of writing haiku.

Note: In the Japanese tradition, haiku poetry contained 17 on . (Linguists also refer to on as morae .) On , or onji , are slightly different from syllables, in that an on counts any variation in sound as a separate phonetic unit. This distinction is mostly irrelevant to English speakers, as we use a different set of vowel sounds than Japanese speakers use. None of this information is related to how to write a haiku poem in English, but if it interests you, you can learn more about morae here .

Classical Japanese haiku requires strict adherence to 17 on . This syllabic constraint does not apply to contemporary English haiku. Rather, the standard length for a modern day poem is that it should be spoken “in a single breath.”

The standard length for a modern day poem is that it should be spoken “in a single breath.”

What does this mean? If you read any of the haiku examples in this article out loud, you should be able to do so without inhaling twice or losing your breath.

As you write a haiku, don’t worry too much about syllables (though certainly keep your poem short). Rather, focus on the fundamentals: natural observation, the juxtaposition of images, and the use of surprising language that imparts on the reader an “aha!” moment. If it’s too wordy, you can omit needless words in revision.

Use this section as a reference for the various components and terms related to haiku poems.

- Gendai— Literally “contemporary,” a gendai haiku encompasses modern values and often dwells on themes of politics, urbanity, modern life, and war. These poems do not use kigo , and they sometimes include similes and metaphors , which a traditional piece lacks.

- Haibun —A specialized type of verse popularized by Bashō. A haibun includes a prose poem and a haiku, each of which draw upon natural observations with a high level of imagery and description. The haiku and the prose poem are related, but one does not explain the other, and the narrative jump between the two is not linear.

- Hokku —The opening 3 lines of a linked verse poem. Its form precedes the modern day haiku.

- Kigo —The “nature word” of a poem. Kigo words are usually seasonal. The word “autumn” is an obvious example, but so is the word “pomegranate,” which is traditionally harvested in, and thus signifies, autumn.

- Kireji —The “cutting word” of a poem, surprising the reader and tying together the juxtaposed images.

- On —A phonetic unit in the Japanese language. A Japanese haiku counts on , whereas an English poem counts syllables.

- Renga —A linked verse poem written by multiple authors, often preceded by a hokku.

- Saijiki —A list of kigo organized by seasonal terms, which poets can reference as they construct their haiku poems.

- Senryū —A humorous poem which utilizes the haiku format, but dwells on man’s foibles.

- Waka —A traditional linked verse poem in classical Japanese literature, usually written by a poet of higher status.

Writers of traditional haiku poems can reference this saijiki for seasonal kigo words.

The following haiku examples come from both classic Japanese and contemporary English literature. Remember: a contemporary piece does not need to have 17 syllables, it must merely be spoken in a single breath.

Matsuo Bashō (1644-1694)

Bashō is one of the most famous Japanese haiku poets, and his work popularized the form throughout all of Japan. In this poem, “Spring is passing” refers to an eternal parting, and the birds and fish represent the poet’s friends.

Fukuda Chiyo-ni (1703-1775)

Chiyo-ni was one of the greatest poets of the Edo period, and also one of the few popular female poets from classical Japan. This poem encompasses the importance of simple observation, and the profound thoughts one can have simply by witnessing nature.

Kobayashi Issa (1763-1828)

Issa, a name which roughly translates to “cup of tea,” wrote poetry that often attended to animals in nature. This poem is allegorical, referring to a traditional Japanese legend of a woman who was led to a Buddhist temple by a cow whose horns had stolen her drying clothes.

Masaoka Shiki (1867-1902)

Despite his short life, Shiki’s work is filled with humor. The name Shiki itself means “little cuckoo” a bird who, in legend, vomited blood from singing so much. (Shiki died from tuberculosis.) In this poem, Shiki juxtaposes the summer moon against the paper lanterns, perhaps commenting on the brightness of the moon despite the streetlights, or perhaps commenting on modernity’s rejection of nature.

Richard Wright (1908-1960)

Richard Wright was a prominent African-American writer, poet, and critic in the 20th century, who wrote countless haiku towards the end of his life. This breathtaking poem begins with an absence of self, juxtaposed against the sublime immensity of the sun, which has stripped the speaker of identity and left him in a field of mystery.

Elizabeth Searle Lamb (1917-2005)

Elizabeth Searle Lamb turned towards the power of haiku poetry in her 40s, and continued to write it throughout the rest of her life. Her work was often ekphrastic and inspired by classical art, such as this poem, which feels as though you are staring at Monet’s painting and falling into a deep, thoughtful tranquility.

James Emanuel (1921-2013)

Highly underrated during his lifetime, James Emanuel’s jazz-and-blues haiku defined the possibilities for the poetry form as its popularity grew in the West. Emanuel’s poems ought to be read accompanied with music, but because most of his poetry was performed in Europe and Africa before modern recording technology was universal, readers are encouraged to read his work rhythmically and out loud.

Jack Kerouac (1922-1969)

Kerouac, as well as the Beat Generation in general, re-popularized haiku poems for the West. Following the advice of “first thought, best thought,” Kerouac’s poems explored the landscape of modern America, yet still found depth and inspiration from natural observation.

Allan Ginsberg (1926-1997)

Alongside Kerouac, Ginsberg’s poetry encouraged writers to meditate, observe, and record thoughts as they arose.

Sonia Sanchez (1934- )

Sonia Sanchez was highly influential to the Black Arts Movement in the 1960s and 70s, and her work continues to inspire poets and artists of all stripes. Her haiku poems are decisively more contemporary and less reliant on natural imagery, which frees her to explore the intersections and juxtapositions of modern America.

While it’s easy to understand the haiku format and the requirements of the form, it can seem daunting to write a haiku that’s both brief and inspirational. Here are a few tips on how to write a haiku poem to get you started.

- Meditate, and stay in the present. Great haiku poetry comes from simple observations, and from accepting what comes to the mind without judgment or modification. Let your thoughts arise naturally, and try to transcribe those images into the poem.

- First thought, best thought . To put it another way: preserve naked thoughts. This advice, borrowed from the Beat Generation of poets, should free you to accept your own thoughts as rich source material for haiku poems and other pieces you write.

- Carry a mindfulness notebook. Throughout your day, use a little notebook to transcribe your dreams, observations, and thoughts as they arise. You might find the notes you jot down combine into powerful haiku poems. Again: do not self edit, simply record things as they occur.

- Lean into uncertainty. You don’t have to know what your own words mean. Many beautiful poems lean into the mystery of language and its countless possibilities.

- Imitate the classics. At least, to get a start in writing haiku poetry, spend some time observing the styles of other poets and trying to imitate them. You might learn how to observe and record the world simply by observing how other poets do it.

- Don’t be concerned with counting syllables. Yes, your poem should be concise and imagistic, and you don’t want to edit too much that you distort your naked thoughts. But, worrying about syllable count will only prevent you from jotting down your honest observations.

- Use representational, symbolic language. Good i magery can act as a symbol, allowing your poem to have multiple meanings. The haiku examples we use from Bashō are rife with symbolism and imagery, such as his poem which represents his friends as birds and fish.

- Use titles to clarify only when necessary. Generally, haiku poems don’t use titles. But, if your poem will make more sense to the reader with a brief, descriptive title, you can bend the rules a little and provide one. Only do this when the clarity is necessary—you might find that your poem benefits from leaning into mystery.

Let’s end with a prompt for writing a haiku, which comes to us from Allan Ginsberg. There are many other prompts for haiku poetry out there, but this one has a contemporary flair to it, and helps the poet rely on their own observations.

Line 1: What is your neurotic confusion? (Something that obsessively confuses you.)

Line 2: What do you really want or desire?

Line 3: What do you notice where you are now?

Here are some literary journals that frequently publish or specialize in haiku poetry.

- Haiku Journal ( link )

- 50 Haikus ( link )

- Nick Virgilio Haiku Association ( link )

- Modern Haiku ( link )

- Wales Haiku Journal ( link )

- Haikuniverse ( link )

- Failed Haiku (which publishes senryū) ( link )

- Acorn ( link )

- Frogpond ( link )

Learn More About Haiku Poems at Writers.com

Whether you take our mindfulness class, our workshop on haiku poems, or any of our other poetry writing classes , Writers.com will help you master the art of haiku. In the meantime, be present, draw upon natural observations, and accept your thoughts as they arise.

Many thanks to Marc Olmsted, Miho Kinnas, Richard Modianos, and Barbara Henning for their insights on the writing process.

Sean Glatch

Thank you Sean

Some of your tips helped my Students to produce more content than Students in my Class last year in the same Unit of Poetry and for World Poetry Day.

Thanks too for your technical support on the Writer’s.Com Courses I’ve taken.

My pleasure, Jen! I’m delighted to hear our poetry advice has helped your students write. Best feeling in the world!

I have loved haiku for many years. I really enjoyed this essay as it brings haiku into modern times and represents freedom from the old strict 5-7-5 syllable in english days. My suggestion to current writers is review, review, review! Eliminate any superfluous words, Pare down to the kernel of your intention. Don’t forget to try different line arrangements to help with the ‘aha’ moments. to write haiku, become haiku in your outlook on everything. Make haiku your record of lived experience, your diary in effect. Remember the power of haibun, study the masters, specially Basho, to see how they painted word pictures so beautifully finished with haiku. Haiku poetry is so much a part of my life that I can never forget it. It illuminates my vision and creates hope for a World so in need of healing.

Thank you for this piece Sean – an off the top of my head for an, I think, Senryu based on your “Lean into uncertainty” – ‘You don’t have to know what your own words mean’:

Therapists love this separated from yourself only one writer

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Writing Poetry

Writing a Haiku: Ideas, Format, and Process

Last Updated: June 24, 2024 Fact Checked

Brainstorming Ideas

Revising and polishing, template for a haiku poem.

This article was co-authored by Alicia Cook and by wikiHow staff writer, Jennifer Mueller, JD . Alicia Cook is a Professional Writer based in Newark, New Jersey. With over 12 years of experience, Alicia specializes in poetry and uses her platform to advocate for families affected by addiction and to fight for breaking the stigma against addiction and mental illness. She holds a BA in English and Journalism from Georgian Court University and an MBA from Saint Peter’s University. Alicia is a bestselling poet with Andrews McMeel Publishing and her work has been featured in numerous media outlets including the NY Post, CNN, USA Today, the HuffPost, the LA Times, American Songwriter Magazine, and Bustle. She was named by Teen Vogue as one of the 10 social media poets to know and her poetry mixtape, “Stuff I’ve Been Feeling Lately” was a finalist in the 2016 Goodreads Choice Awards. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 7,062,982 times.

If you like the idea of making a profound impact in just a few words, haiku might be the perfect poetry form for you. A haiku (俳句 pronounced similar to "high-koo") is a short, 17-syllable poem broken into 3 lines, meant to be read in a single breath. The most important thing about a haiku is that it captures and conveys a sensory image of a single moment in time, and in a well-written haiku, that image resonates on a deeper level, leaving the reader feeling enlightened and illuminated. [1] X Research source Read on to learn everything you need to know to write a powerful haiku poem of your own.

Haiku Format

- Haikus are made of 3 lines, 5 syllables in the first, 7 in the second, and 5 in the third.

- They contain a kireji , or cutting word, which separates the feeling of the poem into two parts, usually at the end of a line.

- Haikus don’t have to rhyme—instead they are supposed to paint a picture of a feeling or a season.

- Matsuo Basho

- Kobayashi Issa

- Winner and Runners-up of the Society of Classical Poets 2021 Haiku Competition

- For this to work, you need all of your senses present—don't take this walk while playing music through headphones. Take a notebook and a pen with you so you can write down your observations.

- You can also record your observations using the notes app on your smartphone. If you go that route, turn off notifications first so you don't have any distractions.

- Don't want to write about nature? That's technically a senryu , which follows the same basic structure, but is more about humanity than nature. [2] X Research source

- It can help to look at the big picture and then think of "zooming in" on a single thing and capturing every possible sensory detail associated with it. For example, you might be looking out at a forest and focus on a single leaf falling.

- For example, if it's fall, you might notice that the leaves are falling from the trees around you. Go smaller! A single leaf falling. A single leaf quivering on a branch before getting taken to the ground by a gust of wind.

- For example, if one of your moments is a single leaf falling, you might list words such as "brown," "crunchy," and "dry."

- Haiku poems aren't supposed to rhyme, so you don't have to worry about that as you're trying to think of words.

- For example, if it's currently fall, you might write down words such as "crisp," "cool," "harvest," and "dusk."

- For example, you might choose a leaf falling to the ground and a gust of wind as your 2 images.

- The second line of a haiku typically includes a "cutting word"—this is a Japanese concept that doesn't really exist in English, but you can think of this as a moment that pivots, or changes, your scene.

- For example, if your haiku is meditating on a single leaf falling to the ground, you might think about how beautiful the leaves are in the fall. They only get their colors because they're dying, though, and death is not something people normally consider beautiful. There's your surprise.

- You can also use wordplay to create your surprise. Throwing in a pun takes your poem beyond its literal meaning to surprise and amuse your readers. [9] X Research source

- Nothing in a haiku has to rhyme, but an unexpected rhyme could also fit the bill for the third line.

- In the first line, the leaf is still clinging to a branch of the tree. You might write, "Dry brown leaf quivers." That's 5 syllables, so there's your first line.

- The second line features the moment of the gust of wind, which also serves as your "cutting word." You might write, "A sudden gust of wind blows."

- Your third line surprises your reader by equating death with beauty. You might simply write, "Beauty in dying."

- What is this word showing my readers? Is there another word that would do a better job of showing the same thing?

- Are there any words that tell readers what to think or feel, rather than showing them? How can you show them the moment more directly?

- In the first line, the word "quivers" is really evocative, so you definitely want to keep that. "Dry" and "brown" aren't exactly inspired, though. Perhaps if you changed the order? "Brown leaf dry quivers" seems more interesting and poetic.

- The second line definitely has problems. "Gust of wind" is somewhat redundant, and "blows" seems totally unnecessary—what else does a gust of wind do, but blow? Try instead "A sudden gust; branches snap," which enables you to use the semi-colon as your "cutting word."

- The third line cleanly conveys your surprise, so you could leave it as it is.

- Other people often come up with things you wouldn't have thought of on your own. They can really inspire you and give you fresh insight into your poem.

- Feel free to revise your haiku even further based on the feedback you receive.

- Haiku traditionally don't have a title. You might add a short one for clarification, but it's usually not necessary and will only detract from the impact of your poem.

- To follow through with the example, the final haiku would be: brown leaf dry quivers a sudden gust; branches snap beauty in dying

Community Q&A

Reader Videos

Share a quick video tip and help bring articles to life with your friendly advice. Your insights could make a real difference and help millions of people!

- If you're writing a haiku for a class, try to stick closely to the 5-7-5 syllable format—your teacher will likely be pretty strict about that! But if you're just writing for yourself, don't worry about it too much. [14] X Research source Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- The plural of haiku is haiku —there's no need to add an "s" onto it if you're talking about more than one. Thanks Helpful 4 Not Helpful 0

Tips from our Readers

- While the haiku format that is most popular in the West is 5-7-5, haiku was actually written in a variety of meters, including 8-8-8 and versions that only use two lines.

- Try not to use similes in haikus (comparisons with the words “like” or “as”).

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://poets.org/glossary/haiku

- ↑ https://ideas.ted.com/i-wrote-a-haiku-every-day-for-a-week-heres-what-i-learned/

- ↑ https://classicalpoets.org/2016/11/13/how-to-write-a-haiku-and-much-much-more/#/

- ↑ https://tricycle.org/article/haiku-tips/

- ↑ https://powerpoetry.org/actions/how-write-haiku-poem

About This Article

To write a haiku poem, write a poem that's 3 lines long and make sure each line has the right number of syllables. Give the first line 5 syllables, the second line 7 syllables, and the third line 5 syllables. Haikus are supposed to help people clearly visualize something, so use sensory details by describing how your subject feels, smells, tastes, looks, and sounds. Also, use the present tense when you're writing your haiku. For more information on how to brainstorm ideas for your haiku from our co-author with an MFA in Creative Writing, keep reading! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Chris Small

Feb 1, 2017

Did this article help you?

ShayDC Chrisman

Apr 3, 2020

Sabrina Sam

May 5, 2016

May 22, 2019

Fred Fullerton

May 19, 2017

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Don’t miss out! Sign up for

wikiHow’s newsletter

Poetry Explained

How to Write a Haiku

Haiku is a form of traditional Japanese poetry that is known for its brevity and focus on capturing the essence of a moment or a feeling. Despite its simplicity, writing a haiku can be a challenging task.

Haiku has its roots in traditional Japanese poetry. The form was developed in the 17th century by the poet Matsuo Bashō , who is considered one of the greatest haiku poets of all time. At the time, haiku was known as hokku and was the opening stanza of a longer collaborative poem known as a renga .

A Brief History of Haiku

What is haiku, 1. choose a subject, 2. focus on a moment, 3. use sensory details, 4. stick to the syllable count, 5. use seasonal or nature imagery, 6. avoid rhyme and metaphors, example #1: everything i touch by kobayashi issa, example #2: after killing a spider by masaoka shiki, example #3: in the moonlight by yosa buson, haiku writing conclusion.

The first versions of haiku were written in the 13th century and were composed as the opening part of a renga or a poem that was read aloud. The opening “haiku” was only one small part of what was a very long poem.

Haiku evolved to become a standalone form of poetry in the 19th century, thanks to the efforts of poets such as Masaoka Shiki, who introduced the term “haiku” and established the 5-7-5 syllable pattern that is still used today.

Haiku gained popularity in Japan and eventually spread to other parts of the world, including the United States, where it became popular in the mid-20th century as part of the Beat Generation literary movement .

Haiku is practiced by poets all over the world and has become a respected and valued form of poetry that is appreciated for its simplicity, focus on a single moment or feeling, and ability to capture the beauty of nature and the human experience.

Haiku is a form of poetry that consists of three lines with a syllable count of 5-7-5. The traditional subject of haiku is nature, but modern haiku can be written about any subject matter .

Haiku is often characterized by its simplicity, its focus on a single moment or feeling, and its use of seasonal or natural imagery .

The first step in writing a haiku is to choose a subject. As mentioned earlier, haiku traditionally focuses on nature, but you can choose any subject that inspires you. Some common subjects for haiku include animals, landscapes, seasons, and emotions.

It’s helpful to consider what comes to mind about a particular place, season, or emotion. For example, if you want to write about fall, what comes to mind? Maybe colorful leaves, cooler weather, holidays, family, etc.

Haiku is all about capturing a moment in time. Choose a specific moment or image you want to convey in your haiku. This could be as simple as a bird taking flight or a leaf falling from a tree.

The best haiku transport the reader, through only a few words, to a place or feeling. Basho is well-known for doing this. For example, in ‘ The old pond ’ he writes:

The old pond; A frog jumps in — The sound of the water.

The reader is meant to imagine this short, beautiful moment. The elevated focus on this scene inspires an appreciation for the natural world and all its simple moments.

In terms of the haiku 5-7-5 , the above haiku does not conform to this, as it was a translation from Japanese (so syllable count won’t be like-for-like).

To make your haiku come alive, use sensory details to describe the moment you’re trying to capture. Use vivid language to describe what you see, hear, smell, taste, and feel.

This is seen through the poet’s use of phrases like “swaying gently / All day long,” as seen in ‘ Spring Ocean ’ by Yosa Buson , or “Fishes weep / With tearful eyes,” as seen in ‘The passing spring’ by Matsuo Bashō.

The syllable count of a haiku is 5-7-5. This means that the first line should have five syllables, the second line should have seven syllables, and the third line should have five syllables. It’s important to stick to this structure to create a true haiku.

When you read famous Japanese haiku, the translation usually eliminates the syllabic pattern. (Additionally, many early haiku did not use the syllabic pattern.) So, when looking for good examples of how the syllable pattern actually works, take a look at English-language haiku. For example, ‘The West Wind’ by R.M. Hansard:

The west wind whispered, And touched the eyelids of spring: Her eyes, Primroses.

While modern haiku can be about any subject matter, traditional haiku often include seasonal or natural imagery. This helps to create a sense of time and place in the poem. Look for ways to incorporate seasonal or nature imagery into your haiku.

Haiku is a form of poetry that relies on simplicity and understatement . Avoid using rhyme or metaphors in your haiku, as this can detract from the poem’s focus on a single moment or feeling.

Examples of Haiku

To help you better understand how to write a haiku, here are some examples:

Everything I touch with tenderness, alas, pricks like a bramble.

In this haiku, the focus is on describing an effort to touch with tenderness. The attempts fail, and the touches keep prickling like “bramble[s].” This is a good example of how nature-related images can be used as symbols for something far deeper.

After killing a spider, how lonely I feel in the cold of night!

This haiku captures a moment in time with the image of the spider and what happened after the speaker killed it. It was a simple choice that didn’t seem important at first. But, after the moment passes, it becomes clear that the poem is interested in the spider as a symbol .

In pale moonlight~ the wisteria’s scent comes from far away.

This haiku captures the sound and scent of leaves and flowers at night, specifically the smell of wisteria as it wafts in. The use of the word “pale” paints a very clear picture of the night sky, even though the poem is so short.

Writing a haiku may seem simple, but it can be a challenging task to create a truly effective and impactful one. However, by following the basic principles of haiku and keeping it simple, you can create a beautiful and meaningful poem that captures a moment in time.

Remember to choose a subject, focus on a moment, use sensory details, stick to the syllable count, use seasonal or natural imagery, and avoid rhyme and metaphors. By incorporating these elements into your haiku, you can create a poem that is both simple and powerful.

With practice and dedication, you can become a skilled haiku writer and explore the many possibilities of this beautiful and unique form of poetry.

The three traditional rules of haiku are: 1. The poem must consist of three lines. 2. The first and third lines must have five syllables, while the second line must have seven syllables. 3. The poem usually focuses on nature or the seasons and usually contains a “cutting word” that emphasizes a contrast or a change.

One of the most famous haiku poems was written by Matsuo Basho, a Japanese poet who lived in the 17th century. The poem is: “An old pond / A frog jumps in / The sound of water.”

Haiku does not need to rhyme . In fact, traditional Japanese haiku rarely use rhyme , as the focus is on the syllable count and the juxtaposition of images or ideas.

Yes, grammar does matter in haiku . While haiku is known for its brevity and simplicity, it still follows the rules of grammar and syntax in order to convey its meaning effectively.

Judging the quality of a haiku is subjective , as it depends on individual taste and the specific elements that one values in a poem. The best haiku follow the syllable pattern, focus on nature-related imagery (often connected to the seasons), and evoke some kind of emotion.

Home » Poetry Explained » How to Write a Haiku

About Emma Baldwin

Experts in poetry.

Our work is created by a team of talented poetry experts, to provide an in-depth look into poetry, like no other.

Cite This Page

Baldwin, Emma. "How to Write a Haiku". Poem Analysis , https://poemanalysis.com/poetry-explained/how-to-write-a-haiku/ . Accessed 30 June 2024.

Help Center

Request an Analysis

(not a member? Join now)

Poem PDF Guides

PDF Learning Library

Poetry + Newsletter

Poetry Archives

Poet Biographies

Useful Links

Poem Explorer

Poem Generator

Poem Solutions Limited, International House, 36-38 Cornhill, London, EC3V 3NG, United Kingdom

Discover and learn about the greatest poetry, straight to your inbox

Unlock the Secrets to Poetry

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

What is a haiku?

What are haiku traditionally about, which notable poets wrote haiku.

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Literary Devices - Haiku

- Association for Asian Studies - Transplanting the Haiku

- Academy of American Poets - Haiku: Poetic Form

- Art in Context - What is a Haiku? – The Art of Writing Japanese Haiku Poetry

- Academia - Haiku Poetry: An Introductory Study

- Encyclopaedia Iranica - Haiku

- haiku - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

The haiku is a Japanese poetic form that consists of three lines, with five syllables in the first line, seven in the second, and five in the third. The haiku developed from the hokku, the opening three lines of a longer poem known as a tanka. The haiku became a separate form of poetry in the 17th century.

Traditionally, writers of haiku have focused on expressing emotionally suggestive moments of insight into natural phenomena. This approach was solidified and popularized by the 17th-century poet Bashō , many of whose haiku reflected his own emotional state when communing with nature. After the 19th century, haiku subjects expanded beyond natural themes.

Influential haiku poets included Bashō , Buson , Issa , Masaoka Shiki , Takahama Kyoshi , and Kawahigashi Hekigotō . Bashō is usually credited as the most influential haiku poet and the writer who popularized the form in the 17th century. Outside Japan, Imagist writers such as Ezra Pound and T.E. Hulme wrote haiku in English.

When did the haiku become popular in the English-speaking world?

The haiku began gaining mainstream recognition outside Japan in the early 20th century. In the English-speaking world, the form was popularized by Imagists such as Ezra Pound and later by Beat poets such as Allen Ginsberg .

haiku , unrhymed poetic form consisting of 17 syllables arranged in three lines of 5, 7, and 5 syllables respectively. The haiku first emerged in Japanese literature during the 17th century, as a terse reaction to elaborate poetic traditions, though it did not become known by the name haiku until the 19th century.

The term haiku is derived from the first element of the word haikai (a humorous form of renga , or linked-verse poem) and the second element of the word hokku (the initial stanza of a renga ). The hokku, which set the tone of a renga , had to mention in its three lines such subjects as the season, time of day, and the dominant features of the landscape, making it almost an independent poem. The hokku (often interchangeably called haikai) became known as the haiku late in the 19th century, when it was entirely divested of its original function of opening a sequence of verse. Today the term haiku is used to describe all poems that use the three-line 17-syllable structure, even the earlier hokku.

Originally, the haiku form was restricted in subject matter to an objective description of nature suggestive of one of the seasons, evoking a definite, though unstated, emotional response. The form gained distinction early in the Tokugawa period (1603–1867) when the great master Bashō elevated the hokku to a highly refined and conscious art. He began writing what was considered this “new style” of poetry in the 1670s, while he was in Edo (now Tokyo). Among his earliest haiku is

On a withered branch A crow has alighted; Nightfall in autumn.

Bashō subsequently traveled throughout Japan , and his experiences became the subject of his verse. His haiku were accessible to a wide cross section of Japanese society, and these poems’ broad appeal helped to establish the form as the most popular form in Japanese poetry.

After Bashō, and particularly after the haiku’s revitalization in the 19th century, its range of subjects expanded beyond nature. But the haiku remained an art of expressing much and suggesting more in the fewest possible words. Other outstanding haiku masters were Buson in the 18th century, Issa in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Masaoka Shiki in the later 19th century, and Takahama Kyoshi and Kawahigashi Hekigotō in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. At the turn of the 21st century there were said to be a million Japanese who composed haiku under the guidance of a teacher.

A poem written in the haiku form or a modification of it in a language other than Japanese is also called a haiku. In English the haiku composed by the Imagists were especially influential during the early 20th century. The form’s popularity beyond Japan expanded significantly after World War II , and today haiku are written in a wide range of languages.

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

How to Write a Haiku: Format, Rules, Structure, and Examples

Hannah Yang

Table of Contents

What is a haiku, haiku format, syllables, and rules, examples of haiku, use prowritingaid’s word explorer to create your own haiku, conclusion on how to write a haiku.

Do you like poems? If you do, try a haiku. It’s a lovely form!

Haiku are short poems that follow a specific three-line format, where the first line has five syllables, the second line has seven syllables, and the last line has five syllables again—just like the first line.

Read on to learn what a haiku is and how you can write one of your own.

A haiku is a short, concise poem that consists of three lines. Traditionally, the first line has five syllables, the second line has seven, and the final line has five.

Each haiku is so short and succinct that you need to choose each syllable carefully. The art of haiku is all about expressing as much as possible in very few words.

This form of poetry originated in Japan. In its earliest form, it was known as hokku.

Japanese poets have been writing hokku for centuries, originally as parts of a longer collaborative poem known as a renga, which sometimes consisted of more than a hundred lines. Poets worked in groups of two or three to take turns composing three-line stanzas and two-line stanzas until they created a complete renga .

Around the 17th century, poets began writing short self-contained poems in the same form as the opening hokku of a renga. Late in the 19th century, renowned poet Masaoka Shiki renamed the stand-alone hokku to haiku .

Most traditional haiku describe a moment in time that captures the beauty or power of the natural world. Classic Japanese poets often used haiku to describe seasonal changes or other natural phenomena.

These days, people all over the world write haiku in various languages about countless different themes. Many poets even break the standard rules of how many syllables each line needs to have, choosing to adhere to the spirit of a haiku rather than the technical rules a haiku usually follows.

The traditional structure of an English haiku consists of three nonrhyming lines with the following syllable counts:

First line: five syllables

Second line: seven syllables

Third line: five syllables

That’s it! If you stick to these syllable counts, you’ll be writing a haiku in no time. The hard part is choosing words that fit perfectly into this format.

Another important decision involves choosing the subject of your haiku.

If you want to stick with the traditional version of haiku, you should describe a moment of time that’s related to the power of nature. Traditional Japanese haiku are supposed to include a kigo , which is a seasonal reference.

Many haiku also juxtapose two distinct images, such as a small cricket with a large mountain or a laughing child with a bitter storm.

Ultimately, you can also use the form to write about anything that resonates with you, the same way you would use any other poetic form. You can write a haiku about love, death, parenthood, corporate office culture, or any other theme you care about.

The rules of haiku format vary between languages, since each language has distinct grammar, punctuation, and formatting conventions. There are some aspects of Japanese haiku format that don’t apply to English haiku format.

For example, traditional Japanese haiku include at least one kireji , which means “cutting word.” The purpose of a kireji is to make a “cut” in a sentence, which cements the end of a stream of thought or creates a pause between two separate ideas.

There’s no exact equivalent to kireji in the English language, so the English haiku format doesn’t include this rule. If you want, you can try to replicate the effect of kireji by using a punctuation mark that creates a “cut” in a sentence, such as an exclamation point, an em dash, or an ellipsis.

The best way to learn poetry is by reading masterful haiku examples so you can learn from the greats.

Four of the greatest haiku masters of all time are Matsuo Bashō (1644–1694), Yosa Buson (1716–1784), Kobayashi Issa (1763–1828), and Masaoka Shiki (1867–1902).

Let’s look at a few examples of Japanese haiku written by these four masters.

“The Old Pond” by Matsuo Bashō

An old silent pond… A frog jumps into the pond— Splash! Silence again.

You can clearly see the contrasting images in this haiku by Matsuo Bashō, which describes a moment in nature. The pond in the poem is silent and still, while the frog is full of motion.

These two images are separated by the kireji, which are represented in the English translation by the ellipsis and the em dash.

One common interpretation of this poem is that Bashō is using the pond as a metaphor for the human mind. External stimuli, like the frog, can momentarily disrupt a mind at rest, but soon, the mind returns to its original state.

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

“Calligraphy of Geese” by Yosa Buson

Calligraphy of geese against the sky— the moon seals it.

Yosa Buson was a painter as well as a poet. He often wrote poems that depicted striking visual imagery.

This poem paints a clear picture, showing geese flying on a moonlit night. The kireji , represented in English by an em dash, creates a pause in the poem that separates the “calligraphy” of the geese and the “seal” of the round moon.

“A World of Dew” by Kobayashi Issa

This world of dew, is a world of dew, and yet…and yet…

“A World of Dew” is one of Issa’s most famous poems. He wrote this poem a month after his young daughter passed away.

Dewdrops are often used in Japanese literature to represent the transience of human life, since dewdrops vanish when the sun comes up. With this simple poem, Issa creates a nuanced feeling about life and death using only a few words.

“Pain From Coughing” by Masaoka Shiki

Pain from coughing the long night's lamp flame small as a pea

Masaoka Shiki contracted tuberculosis in his twenties, which eventually took his life. He often wrote poems that depicted short sketches of his life, including poems that described his illness.

In this poem, you can see a moment in Shiki’s struggle with illness. His description of the dwindling lamp flame evokes the image of a light going out at the end of a life.

More recently, many haiku poets have also written modern haiku poems that are powerful and evocative.

Here are some examples of haiku written in English.

“In a Station of the Metro” by Ezra Pound

The apparition of these faces in the crowd; Petals on a wet, black bough.

Ezra Pound was an American poet and critic. His poem “In a Station of the Metro” is widely considered the first English haiku, even though it doesn’t follow the three-line structure of a standard haiku.

Like traditional haiku, this poem captures a single moment in time. It also juxtaposes two distinct images: human faces in a busy metro station and flower petals on a tree branch.

“The West Wind Whispered” by R.M. Hansard

The west wind whispered, And touched the eyelids of spring: Her eyes, Primroses.

This poem won the first British haiku competition in 1899.

It personifies the west wind, portraying it as something capable of whispering and touching. Hansard describes the arrival of spring in a way that gives nature agency.

“Picasso’s ‘Bust of Sylvette’” by Elizabeth Searle Lamb

Picasso’s “ Bust of Sylvette ” not knowing it is a new year smiles in the same old way

Elizabeth Searle Lamb was a 20th century poet. The prominent poet Father Raymond Roseliep called her “The First Lady of American Haiku.”

In this poem, she portrays the arrival of a new year by describing a sculpture that has smiled the same way across all the years because it’s carved in stone. The poem captures timelessness and change in a single stroke.

“Haiku [for you]” by Sonia Sanchez

love between us is speech and breath. loving you is a long river running.

Sonia Sanchez is an American poet, playwright, and professor who was a leading figure in the Black Arts Movement.

In this haiku, Sanchez compares love to speech, breath, and a long river running. All three of these things are natural and simple, which makes the love she describes feel just as instinctive and effortless.

Writing a haiku is all about choosing the right words to express exactly what you mean.

ProWritingAid’s Word Explorer gives you a wealth of words to choose from. It gives you all the word options a dictionary or thesaurus would, along with plenty of other insights into that word.

The tool can let you look at a word based on alliteration, rhyme, pronunciations, common phrases, collocations, and more. It’s a great way to make sure each of the words you choose is perfect in as many ways as possible.

So, if you’re trying to write a haiku and you can’t think of a word with the right syllable count for that line, try the Word Explorer to find a perfect replacement.

There you have it—a complete guide to how haiku poetry works and how you can write a haiku poem of your own.

Good luck, and happy writing!

Hannah is a speculative fiction writer who loves all things strange and surreal. She holds a BA from Yale University and lives in Colorado. When she’s not busy writing, you can find her painting watercolors, playing her ukulele, or hiking in the Rockies. Follow her work on hannahyang.com or on Twitter at @hannahxyang.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

- Join for Free

How To Write Haiku Poems With Examples

- by Domestika @domestika

Explore the art of haiku poetry: Discover its history, unique format, and immerse yourself in examples from renowned poets.

Haiku poems have persisted for centuries, capturing the essence of brief moments in nature. In this article, you will learn what a haiku is, what its format is and some examples. Let's take a look!

What is a Haiku?

What is the format of a haiku poem.

Steps on how to write a Haiku poem

1. Choose a subject: A good starting point is to pick a subject that inspires you. Nature, emotions, and everyday experiences can form the foundation of your poem.

2. Focus on a moment: These poems usually capture a specific moment or feeling. Try to convey the essence of that moment without any unnecessary details or explanations.

3. Use sensory details: Engage your readers' senses by incorporating vivid and descriptive language. Haikus often emphasize imagery, which helps paint a picture in the reader's mind.

4. Stick to the syllable count: Its structure follows a 5-7-5 syllable pattern, with five syllables in the first line, seven in the second, and five in the third. Although this rule is not always strictly followed, adhering to it can provide structure and ensure the poem is concise.

5. Use seasonal or nature imagery: In many classic haikus, the poet references nature or the seasons to set the scene and evoke emotions. This can help enhance the poem's imagery and establish a connection with the reader.

6. Avoid rhyme and metaphors: It's often best to avoid using rhyming schemes or overusing metaphors. This keeps the poem direct and unadorned, allowing the vivid imagery to shine through.

Examples of Haiku

Haiku poems about love Haiku poems about love offer a unique perspective on the theme, capturing moments of romance and connection within the brevity of the three-line format. Let's take a look at these two examples from Japanese poet, Bashō

1. Love Haiku poem by Bashō Easing in her slender forearm for his pillow

This haiku captures a fleeting moment of tenderness and intimacy between two lovers. The simplicity of the act – using one's arm as a pillow – is a testament to their deep connection.

2. Another love haiku poem by Bashō Leaf-wrapping the rice cakes, with one hand she tucks back her hair.

Bashō's haiku captures a fleeting, intimate moment in everyday life: a woman wrapping rice cakes in leaves. The delicate gesture hint at the deeper emotional connections and the profound beauty in the small, shared experiences that often define relationships.

Haiku poems about nature Haiku poems about nature beautifully capture fleeting moments in the natural world, using vivid imagery to evoke emotions and sensations.

1. Nature Haiku poem by Bashō: Old pond... A frog jumps in: The sound of water.

This simple yet powerful haiku encapsulates the essence of a brief moment in time. The image of a frog jumping into an old pond creates a sense of movement and vitality, while the sound of water resonates with the reader, transporting them to the scene.

2. Nature Haiku poem by Masaoka Shiki: Repeatedly, How is the snow depth? I asked.

Shiki's haiku reflects anticipation and curiosity about snow's depth, suggesting deep engagement and possibly eagerness for environmental change. Both Bashō and Shiki emphasize the brevity of life and the appreciation of simple, fleeting moments in nature.

Haiku poems about life They offer a glimpse into the beauty and complexities of the human experience, connecting us with our surroundings and the natural world.

1. Haiku poem about life: Anonymous Life’s a mystery We search for answers every day Few are ever found

The haiku talks about how life is mysterious and even though we always look for answers, we rarely find them.

2. Haiku poem about life: Anonymous Life is a journey A story only you can write Make your own destiny

The haiku says that everyone's life is their own unique journey. It tells us to take control, make our own choices, and not let others decide our path. The poem encourages us to be independent and shape our own destiny. In just a few lines, haiku poems about life capture the essence of existence, offering insight into the human condition and encouraging us to cherish each passing moment.

You may also like: - Check out our writing courses - What is poetry? Definition, characteristics and types

Recommended courses

Writing Exercises: From the Blank Page to Everyday Practice

A course by Aniko Villalba

Engage in creative writing exercises that document and generate ideas, and transform it into a regular practice

- 98% ( 1.2K )

Writing a Novel Step by Step

A course by Cristina López Barrio

Learn the keys to writing a novel and stimulate your imagination with practical exercises that connect you with your inner world

- 98% ( 2.4K )

- Follow Domestika

How to Write a Haiku Poem

by Pamela Hodges | 61 comments

Haiku are a type of traditional Japanese poetry. Only three lines long, haiku are fun to write and share. Let's find out what a haiku poem is and what we need to write our own!

Definition: What Is a Traditional Haiku Poem?

Haiku originated in Japan and as a poetic form, they are arranged in three lines, each line with a specific number of syllables. Here are the elements you need for a traditional haiku:

- Three lines that don't rhyme, with seventeen syllables in a 5-7-5 pattern. Five syllables in the first and third line, and seven syllables in the second line.

- Each haiku “must contain a kigo . A word that indicates the season in which the poem is set,” according to the World Book Encyclopedia, page eight, volume nine, between the words Douglas Haig and Hail, and according to Japanese Haiku tradition. The word that indicates season can be obvious, like “ice” to indicate winter. Or it can be more subtle, like using the expression “fragrant blossom” to indicate spring.

- The words and expressions in the poem are usually simple and deal with everyday situations, usually capturing a moment in time, often in nature.

- Usually, the haiku form does not contain metaphors and similes.

Subject matter: Haikus Are About a Single Moment

“Haiku explores a single moment's precise perception and resinous depths.” — Jane Hirshfield, The Heart of Haiku

Matsuo Bashō, a popular Japanese poet, composed this poem in the late 1600's.

furuike ya kawazu tobikomu mizu no oto

In English:

old pond: frog leaps in the sound of water

The English version doesn't follow the syllabic pattern due to translation differences, but you can see all the other elements of haiku in play. It's arranged in three lines with the traditional number of syllables in each. Its subject matter is the small splash a frog makes leaping into an old pond.

Why focus on a single moment?

Good question. Haiku invite us to slow down as readers and experience a single moment, to pay attention . And isn't that part of what fuels great writing?

Let's turn again to Japanese poet Bashō to show us how to write a haiku poem.

Jane Hirshfield explains in her book, The Heart of Haiku , how Bashō encourages us to see for ourselves and hear for ourselves, and if we enter deeply enough this seeing and hearing, all things will speak with and through us.

“To learn about the pine tree go to the pine tree; to learn from the bamboo, study bamboo.” — Matsu Bashō , Jane Hirshfield, The Heart of Haiku

Using the four guidelines mentioned above, think of an everyday situation, feeling, or a precious moment, such as a blade of grass, a sink full of dirty dishes in the spring, a warm cat, or the sound of snow falling.

If your haiku poem is about something that has happened in your past, if you are remembering a snowfall from last winter, then sit in a quiet spot and go to the memory in your mind.

Use all of your senses. Think of what you heard, felt, tasted, smelled and saw. Let us live the moment with you through distinct images.

If your haiku is about a blade of grass, as Bashō said, go to the grass. Yes, that's right. Go outside right now and lay down in the grass and let the single blade of grass speak through you. Study the grass.

If you are writing about a warm cat, go to the cat and study the cat. Study the sink full of dirty dishes while you wash them. To learn about snow go to the snow.

Ready to Write Your Haiku?

Now that you've tried to immerse yourself in an experience to use for your inspiration, pick out some words that describe the sensations you felt. Remember to choose precise words that capture the moment. Arrange them into three lines and count out those syllables for each.

If you are not sure how many syllables are in a word, you can check out your word on Mirriam-Webster , an on-line dictionary.

You might find that the practice of writing haiku is meditative and a little addicting. It's great practice for using language to show but not tell. The art of haiku is a perfect way to practice creating strong images that will benefit your other forms of writing as well.

I hope you'll give it a try today!

Do you have a favorite haiku? Have any tricks you use to write them? Share in the comments .

Practice staring at a blade of grass for fifteen minutes . No, I have a better idea. Come and help me wash my dishes. We can both write about washing dishes.

Okay, seriously now. Please write your thoughts down about something you see in your everyday world or focus on nature, and then try to fit it to the five-seven-five pattern.

Write a haiku poem and share it with us in the practice box below. Then comment on someone else's work. I hope you enjoy this old form in new ways!

Pamela Hodges

Pamela writes stories about art and creativity to help you become the artist you were meant to be. She would love to meet you at pamelahodges.com .

61 Comments

Am I missing something or does the sample not follow the syllable rule?

Hello Concordriverlady,

The Japanese language does not have syllables like English does. So their words don’t translate into our English syllables. The center line, “kaqaza tobikama” has seven sounds, seven individual sounds – ka-ga-za – to-bi-ka-ma. But, when you translate it into english, you don’t get seven syllables. Thank you for pointing out the syllable variable in the example. xo Pamela

For those serious about a study of haiku, Harold G. Henderson’s An Introduction to Haiku (1958) is perhaps the definitive little tome. For each haiku, he gives you the lines in Romaji (phonetically spelling out the words as they sound in Japanese but using the alphabet) and English translations. It is fascinating to see how Japanese syntax and thus the emphasis they place on the elements of the poem are different from English. Pamela, your transcription of Basho’s haiku in Japanese does not reflect the correct translation of the individual words in English. Henderson’s rendering of the poem is as follows: Furuike ya / kawazu tobi-komu/ mizu-no-oto…This is the standard translation and conforms perfectly to the form here. Thanks for your post!

Thank you Jeanne, I corrected the spelling of the Haiku by Matsuo Bashō. Thank you for pointing it out. The book you suggested sounds great. I will have to check it out. There is so much more to this art form I would love to learn. xo Pamela

the syllable count in the 5-7-5 format is old and distorted information and not a true rule. Haiku experts around the world debunk this all the time- see http://www.nahaiwrimo.com/home/why-no-5-7-5 great description of the art form! But the syllable rule was taught that way in USA schools for decades so it has deep hold as fact, but its really innacurate. There are many various forms of haiku but all with similar components, and though it can be fun and informative to writing discipline to limit ones writing to a a certain # of syllables or characters (as in Tweets), it is not an imperative of haiku at all. The more important elements are the seasons, the objects of the senses, the perceptions of a moment in time, all in few words and lines, and what i think is the most difficult aspect, and the kicker as I like to call it or kirejji/ “cutting” word that cuts the poem, turns it subtly to a previously unseen or unexpected perspective.

Great link Sheila. You are so right that the focus should not be on the strict syllabic count but the elements referenced in the linked post. Though I personally like the challenge of that stricture 🙂

Hello Sheila B, Thank you for the link to the article about the 5-7-5 rule. There is so much to learn about this art form. Thank you for sharing your knowledge about haiku. I want to learn more about haiku, especially the element of the cutting word. All my best, xo Pamela

The tree wears white lace Each branch and twig atwinkle First frost in new morn

Hello Jay, Thank you for writing a haiku. 🙂 The frost and the white lace are very vivid images. xo Pamela

thanks Pamela, I took your advice and went outside. The frost on the tree was very striking to me.

Wow, is that beautiful imagery.

thank you, Katherine.

Sunset reflects light Off the fresh fallen snow drifts Sinks and all is black

Hello Katherine Rebekah, Your first two lines created a strong feeling of light, reflection, fresh fallen, and then the word fallen lead to sinking and black. A strong powerful contrast. Thank you sharing your writing. xo Pamela

I’m glad you liked it. Always happy to share. 🙂

My first time commenting here! This was a great prompt for me as I am trying to write a poem every day so it fit into my established routine, besides I love haiku even though I don’t have much practice with them!

Such a lot of noise Galahs tumbling through open air Before midday heat

That one is outside my window this morning. This one reuses the first line,

Such a lot of noise So much fuss about what she’s done Chicken has laid an egg

Thanks so much for a great prompt and article! 🙂

Hello Zuop, Thank you for sharing your writing, and for being brave to make your first comment. How is your daily poetry writing habit going? Your poetry created strong feelings of nature, (and a noisy chicken.) xo Pamela

Hey Pamela, thanks! I am very inspired by nature because I live in a rural area. Yes it’s going pretty well so far, it’s good to get in a habit of writing something every day 🙂 I really enjoyed your article too, love your writing style 🙂

As colored leaves fall Blending with gentle breezes Harmonies of life

I like this, felicia_d. I wanted to write about autumn leaves but wrote about my cat instead.

Hello felica_d Your leaves felt like they were really falling, as though I was there, feeling the gentle breeze. It brought back memories of being beneath a giant Maple tree in the fall in Minnesota. Thank you, xo Pamela

Thanks, Pamela!

Seed awaits heaven’s breath immanent I am

Wrote this ignorant of Haiku structure so not following the 3 line structure or syllabic rules more 1, 2, 3, 3, 2

Hello Masterman, Your poem has a pattern that is very gentle, thank you for showing the structure you used. The seed felt very real. xo Pamela

My foot squinched a bug Flat, wet, two-dimensional. Candle drew it in.

Very expressive, Winnie. I can feel the bug underfoot.

Really like your haiku. But I believe the first line has 6 syllables–that is, if squinched has 2

My squinched has only one. I imagine Shakespeare would have made it two.

pretty good 🙂

Hello Winniw, Oh dear, the thought of stepping on a bug, really made the poem feel real. The words, flat and wet. The candle drew me in too. xo Pamela

This is quite new to me and I don’t know if I’ve got it right. You be the judge.

My cat purrs softly Curled on the Persian rug Winter’s at the door.

Sure seems to have the right number of syllables. Your haiku evokes a really sweet image.

Thanks, Louise.

Hello Lillian, Thank you for trying a new form of writing. Your haiku is hi-cool. The words create such a warm atmosphere. softly curled and the last sentence is such a contrast. It words very well. And the cat is on a Persian rug, not a tile floor, it make the room feel warmer. xo Pamela

Hello Pam, You are sensitive and observant to note the difference from a Persian rug and tile floor. Actually, your words did the trick! You asked us to connect physically with something to create the verse and I did just that. Please hug Harper for me and for Minnie, too. Lilian

I love this!

Thanks, Haylee. 🙂

crisp fog stains twilight breath afloat on morning air promise for new day

oh david, i won’t capitalize anything here too or use punctuation the words took on the shape of the fog without capital letters these words really created the mood crisp stains breath afloat and promise helped me get out of the fog it is sort of like the fog would be real in the air but also the fog of depression that is how it spoke to me xo pamela

Darkness falls Light awaits Ocean of people living in routine

Hello Crystal Johnson, Oh my, an ocean of people living in routine. I felt the monotony of people living in routine, day after day. Dark then light, dark then light. Makes me want to climb out of the ocean. xo Pamela

That was awesome, I need to practice more. I feel the wrong element of people in my life and I need to let go of, but it seems that element won’t let go of me.

Leaves scatter around Sky full of brittle gold birds The cold cuts my face

Really like ‘The cold cuts my face’

Me too Louise Rita, The cold cuts my face, is such a strong image. And “brittle” gold birds, with the word cuts, makes me think the birds might break apart in the cold. Very strong images. I felt cold after I read it. xo Pamela

Outline so simple 5 Evokes painful memories 7 Makes it hard to write 5

Hello Louise Rita, Oh dear, I am sorry about the painful memories. I felt them too. In your three lines, you expressed your pain. Perhaps it was the word, “evokes.: And in the hard writing you still wrote. xo Pamela

Yes. I live in the macalester Groveland area of St. Paul.

I posted this yesterday on my Facebook page (Mike Schoenberg). Please visit:for more haiku.

Gutter full rainfall, autumn monsoon thunderstorm in the dark of night.

Hello St.Paul Mike, Does this mean you live in St. Paul, Minnesota? We use to live there, on the East Side, close to Payne Avenue, Gutter full, expresses heavy rain so well. A small glimpse of a storm moment. xo Pamela

I live in the Macalester – Groveland area. Thanks for the comment.

Laying on the ground Sun shining on snow and ice I feel the murmer

Hello Vanessa, Laying on the ground, you became one with the snow and ice. You felt the murmer, and I did too. xo Pamela

Thanks! It’s been fun, I am going through back injections so spending a lot of time on the ground, but I seem to be coming up with Haiku’s through the day and all inspired by you 🙂 I did not spend much time on my Haiku it was just a fun exercise, but I like it better written On the ground laying Snow and Ice the sun shining I feel the murmur…..Thanks again for the prompt!

Hello LaCresha Lawson, Please share your son’s work. It would be a pleasure to read their writing. xo Pamela

I sure will. Thank you.☺

November 15, 2015

Luke Ramirez, 13

My son’s Haiku Poem

For the Write Practice

LaCresha Lawson

Sitting on my bed

Wondering when I got it,

remembering now.

Writing Haiku past midnight is an exercise in futility

Window veiled in frost Inside they smile and fire burns Yet I am outside

Laura, this is fabulous. What a vivid picture your words evoke.

Hi Pamela, I’m very late with my comment on this post. Nanowrimo has turned my schedule upside down. 🙂

Actually there often is a metaphor in haiku, but it tends to be understood by the original writers because they used words with a double meaning, such as “scarecrow” which tended to stand for “old man” or “old age.” Consider that as you read this verse: scarecrows are the first heroes to fall in the rush of the autumn wind Kyoroku

Chrysanthemums and cherry blossoms likewise say something to the Japanese that they don’t say to us, giving a verse like this meaning we wouldn’t as soon catch: even stones in streams of mountain water compose songs to wild cherries Onitsuba

I see there’s often a hidden implication in the verse. For example you fleas seem to find the night as long as I do are you lonely, too Issa One can picture both the poet’s loneliness (his wife died young); that loneliness, as well as the fleas, tormented him all night.

I’ve tried my hand at haiku as well. Here’s one of my best liked verses: roadside sunflowers faces turned from the rude wind looking for summer

And my scarecrow one, complaining about my own achy old age: 🙂 this sorry scarecrow grown stiff in autumn’s frosts sighs for the tasseling corn

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- Why You Should Write Poetry in the Midst of Tragedy - BlogYetu - […] wrote a blog, but that was to keep people aware that I was doing just fine. Then I started…

- Haiku and Watercolor Fun | Never Give Up by Joan Y. Edwards - […] Pamela Hodges. “How to Write a Haiku Poem:” https://thewritepractice.com/write-haiku […]

- How to Find Writing Inspiration in Your Garden - How To Write Shop - […] Write a haiku (3 lines, first and last lines have 5 syllables and the middle line has 7). […]

- Haiku and Watercolor Fun | Joan Y. Edwards - […] Pamela Hodges. “How to Write a Haiku Poem:” https://thewritepractice.com/write-haiku […]

- Can Constrained Writing Make You a Better Writer? - […] is a literary technique where you create rules and limits for your writing. For example, haiku is a popular…

- Can Constrained Writing Make You a Better Writer? – Charlotte’s Blog - […] is a literary technique where you create rules and limits for your writing. For example, haiku is a popular…

- Can Constrained Writing Make You a Better Writer? – Top News Rocket - […] writing” is a literary technique where you create rules and limits for your writing. For example, haiku is a…

- Can Constrained Writing Make You a Better Writer? - - […] writing” is a literary technique where you create rules and limits for your writing. For example, haiku is a…

- Can Constrained Writing Make You a Better Writer? – GaleForceNews.com - […] writing” is a literary technique where you create rules and limits for your writing. For example, haiku is a…

- Can Constrained Writing Make You a Better Writer? – The News Stories - […] writing” is a literary technique where you create rules and limits for your writing. For example, haiku is a…

- Can Constrained Writing Make You a Better Writer? – My WordPress - […] writing” is a literary technique where you create rules and limits for your writing. For example, haiku is a…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Submit Comment

Join over 450,000 readers who are saying YES to practice. You’ll also get a free copy of our eBook 14 Prompts :

Popular Resources

Book Writing Tips & Guides Creativity & Inspiration Tips Writing Prompts Grammar & Vocab Resources Best Book Writing Software ProWritingAid Review Writing Teacher Resources Publisher Rocket Review Scrivener Review Gifts for Writers

Books By Our Writers

You've got it! Just us where to send your guide.

Enter your email to get our free 10-step guide to becoming a writer.

You've got it! Just us where to send your book.

Enter your first name and email to get our free book, 14 Prompts.

Want to Get Published?

Enter your email to get our free interactive checklist to writing and publishing a book.

- Poetry Contests

How to Write a Haiku

A quick haiku guide , a traditional haiku should….

1. Be three lines. The first line should have five syllables, the second seven syllables, the third five syllables. Seventeen syllables total.

2. Contain a nature or seasonal reference: the crumbling leaves, the cold air, the smell of manure, the taste of fresh black berries, the cicadas’ buzzing.

3. Be in the present tense (swims rather than swam).

4. Be subtle and observational.

5. Contain some sort of twist in the third line: a shift in perspective or mood, a surprise, a new interpretation of the first or second line.

6. Not worry about rhyming, although it can be a bonus.

An In-depth Haiku Guide

by G. M. H. Thompson

The Japanese-inspired haiku is perhaps the most well-known and often used form of poetry today. Schoolchildren the English-speaking-world over know that a haiku is five syllables in the first line followed by seven syllables in the second line followed by a final five syllables in the third and final line. It’s as simple as counting, right? Well, if that was right, this essay would end right here.

For, although the haiku is perhaps the most well-known form of poetry, it is also probably the least well-understood. The contents of a legitimate and interesting haiku must do about five different things all at once in a very tight space.