Related Expertise: Culture and Change Management , Business Strategy , Corporate Strategy

Five Case Studies of Transformation Excellence

November 03, 2014 By Lars Fæste , Jim Hemerling , Perry Keenan , and Martin Reeves

In a business environment characterized by greater volatility and more frequent disruptions, companies face a clear imperative: they must transform or fall behind. Yet most transformation efforts are highly complex initiatives that take years to implement. As a result, most fall short of their intended targets—in value, timing, or both. Based on client experience, The Boston Consulting Group has developed an approach to transformation that flips the odds in a company’s favor. What does that look like in the real world? Here are five company examples that show successful transformations, across a range of industries and locations.

VF’s Growth Transformation Creates Strong Value for Investors

Value creation is a powerful lens for identifying the initiatives that will have the greatest impact on a company’s transformation agenda and for understanding the potential value of the overall program for shareholders.

VF offers a compelling example of a company using a sharp focus on value creation to chart its transformation course. In the early 2000s, VF was a good company with strong management but limited organic growth. Its “jeanswear” and intimate-apparel businesses, although responsible for 80 percent of the company’s revenues, were mature, low-gross-margin segments. And the company’s cost-cutting initiatives were delivering diminishing returns. VF’s top line was essentially flat, at about $5 billion in annual revenues, with an unclear path to future growth. VF’s value creation had been driven by cost discipline and manufacturing efficiency, yet, to the frustration of management, VF had a lower valuation multiple than most of its peers.

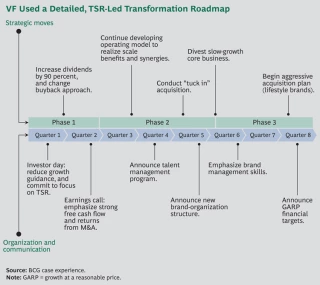

With BCG’s help, VF assessed its options and identified key levers to drive stronger and more-sustainable value creation. The result was a multiyear transformation comprising four components:

- A Strong Commitment to Value Creation as the Company’s Focus. Initially, VF cut back its growth guidance to signal to investors that it would not pursue growth opportunities at the expense of profitability. And as a sign of management’s commitment to balanced value creation, the company increased its dividend by 90 percent.

- Relentless Cost Management. VF built on its long-known operational excellence to develop an operating model focused on leveraging scale and synergies across its businesses through initiatives in sourcing, supply chain processes, and offshoring.

- A Major Transformation of the Portfolio. To help fund its journey, VF divested product lines worth about $1 billion in revenues, including its namesake intimate-apparel business. It used those resources to acquire nearly $2 billion worth of higher-growth, higher-margin brands, such as Vans, Nautica, and Reef. Overall, this shifted the balance of its portfolio from 70 percent low-growth heritage brands to 65 percent higher-growth lifestyle brands.

- The Creation of a High-Performance Culture. VF has created an ownership mind-set in its management ranks. More than 200 managers across all key businesses and regions received training in the underlying principles of value creation, and the performance of every brand and business is assessed in terms of its value contribution. In addition, VF strengthened its management bench through a dedicated talent-management program and selective high-profile hires. (For an illustration of VF’s transformation roadmap, see the exhibit.)

The results of VF’s TSR-led transformation are apparent. 1 1 For a detailed description of the VF journey, see the 2013 Value Creators Report, Unlocking New Sources of Value Creation , BCG report, September 2013. Notes: 1 For a detailed description of the VF journey, see the 2013 Value Creators Report, Unlocking New Sources of Value Creation , BCG report, September 2013. The company’s revenues have grown from $7 billion in 2008 to more than $11 billion in 2013 (and revenues are projected to top $17 billion by 2017). At the same time, profitability has improved substantially, highlighted by a gross margin of 48 percent as of mid-2014. The company’s stock price quadrupled from $15 per share in 2005 to more than $65 per share in September 2014, while paying about 2 percent a year in dividends. As a result, the company has ranked in the top quintile of the S&P 500 in terms of TSR over the past ten years.

A Consumer-Packaged-Goods Company Uses Several Levers to Fund Its Transformation Journey

A leading consumer-packaged-goods (CPG) player was struggling to respond to challenging market dynamics, particularly in the value-based segments and at the price points where it was strongest. The near- and medium-term forecasts looked even worse, with likely contractions in sales volume and potentially even in revenues. A comprehensive transformation effort was needed.

To fund the journey, the company looked at several cost-reduction initiatives, including logistics. Previously, the company had worked with a large number of logistics providers, causing it to miss out on scale efficiencies.

To improve, it bundled all transportation spending, across the entire network (both inbound to production facilities and out-bound to its various distribution channels), and opened it to bidding through a request-for-proposal process. As a result, the company was able to save 10 percent on logistics in the first 12 months—a very fast gain for what is essentially a commodity service.

Similarly, the company addressed its marketing-agency spending. A benchmark analysis revealed that the company had been paying rates well above the market average and getting fewer hours per full-time equivalent each year than the market standard. By getting both rates and hours in line, the company managed to save more than 10 percent on its agency spending—and those savings were immediately reinvested to enable the launch of what became a highly successful brand.

Next, the company pivoted to growth mode in order to win in the medium term. The measure with the biggest impact was pricing. The company operates in a category that is highly segmented across product lines and highly localized. Products that sell well in one region often do poorly in a neighboring state. Accordingly, it sought to de-average its pricing approach across locations, brands, and pack sizes, driving a 2 percent increase in EBIT.

Similarly, it analyzed trade promotion effectiveness by gathering and compiling data on the roughly 150,000 promotions that the company had run across channels, locations, brands, and pack sizes. The result was a 2 terabyte database tracking the historical performance of all promotions.

Using that information, the company could make smarter decisions about which promotions should be scrapped, which should be tweaked, and which should merit a greater push. The result was another 2 percent increase in EBIT. Critically, this was a clear capability that the company built up internally, with the objective of continually strengthening its trade-promotion performance over time, and that has continued to pay annual dividends.

Finally, the company launched a significant initiative in targeted distribution. Before the transformation, the company’s distributors made decisions regarding product stocking in independent retail locations that were largely intuitive. To improve its distribution, the company leveraged big data to analyze historical sales performance for segments, brands, and individual SKUs within a roughly ten-mile radius of that retail location. On the basis of that analysis, the company was able to identify the five SKUs likely to sell best that were currently not in a particular store. The company put this tool on a mobile platform and is in the process of rolling it out to the distributor base. (Currently, approximately 60 percent of distributors, representing about 80 percent of sales volume, are rolling it out.) Without any changes to the product lineup, that measure has driven a 4 percent jump in gross sales.

Throughout the process, management had a strong change-management effort in place. For example, senior leaders communicated the goals of the transformation to employees through town hall meetings. Cognizant of how stressful transformations can be for employees—particularly during the early efforts to fund the journey, which often emphasize cost reductions—the company aggressively talked about how those savings were being reinvested into the business to drive growth (for example, investments into the most effective trade promotions and the brands that showed the greatest sales-growth potential).

In the aggregate, the transformation led to a much stronger EBIT performance, with increases of nearly $100 million in fiscal 2013 and far more anticipated in 2014 and 2015. The company’s premium products now make up a much bigger part of the portfolio. And the company is better positioned to compete in its market.

A Leading Bank Uses a Lean Approach to Transform Its Target Operating Model

A leading bank in Europe is in the process of a multiyear transformation of its operating model. Prior to this effort, a benchmarking analysis found that the bank was lagging behind its peers in several aspects. Branch employees handled fewer customers and sold fewer new products, and back-office processing times for new products were slow. Customer feedback was poor, and rework rates were high, especially at the interface between the front and back offices. Activities that could have been managed centrally were handled at local levels, increasing complexity and cost. Harmonization across borders—albeit a challenge given that the bank operates in many countries—was limited. However, the benchmark also highlighted many strengths that provided a basis for further improvement, such as common platforms and efficient product-administration processes.

To address the gaps, the company set the design principles for a target operating model for its operations and launched a lean program to get there. Using an end-to-end process approach, all the bank’s activities were broken down into roughly 250 processes, covering everything that a customer could potentially experience. Each process was then optimized from end to end using lean tools. This approach breaks down silos and increases collaboration and transparency across both functions and organization layers.

Employees from different functions took an active role in the process improvements, participating in employee workshops in which they analyzed processes from the perspective of the customer. For a mortgage, the process was broken down into discrete steps, from the moment the customer walks into a branch or goes to the company website, until the house has changed owners. In the front office, the system was improved to strengthen management, including clear performance targets, preparation of branch managers for coaching roles, and training in root-cause problem solving. This new way of working and approaching problems has directly boosted both productivity and morale.

The bank is making sizable gains in performance as the program rolls through the organization. For example, front-office processing time for a mortgage has decreased by 33 percent and the bank can get a final answer to customers 36 percent faster. The call centers had a significant increase in first-call resolution. Even more important, customer satisfaction scores are increasing, and rework rates have been halved. For each process the bank revamps, it achieves a consistent 15 to 25 percent increase in productivity.

And the bank isn’t done yet. It is focusing on permanently embedding a change mind-set into the organization so that continuous improvement becomes the norm. This change capability will be essential as the bank continues on its transformation journey.

A German Health Insurer Transforms Itself to Better Serve Customers

Barmer GEK, Germany’s largest public health insurer, has a successful history spanning 130 years and has been named one of the top 100 brands in Germany. When its new CEO, Dr. Christoph Straub, took office in 2011, he quickly realized the need for action despite the company’s relatively good financial health. The company was still dealing with the postmerger integration of Barmer and GEK in 2010 and needed to adapt to a fast-changing and increasingly competitive market. It was losing ground to competitors in both market share and key financial benchmarks. Barmer GEK was suffering from overhead structures that kept it from delivering market-leading customer service and being cost efficient, even as competitors were improving their service offerings in a market where prices are fixed. Facing this fundamental challenge, Barmer GEK decided to launch a major transformation effort.

The goal of the transformation was to fundamentally improve the customer experience, with customer satisfaction as a benchmark of success. At the same time, Barmer GEK needed to improve its cost position and make tough choices to align its operations to better meet customer needs. As part of the first step in the transformation, the company launched a delayering program that streamlined management layers, leading to significant savings and notable side benefits including enhanced accountability, better decision making, and an increased customer focus. Delayering laid the path to win in the medium term through fundamental changes to the company’s business and operating model in order to set up the company for long-term success.

The company launched ambitious efforts to change the way things were traditionally done:

- A Better Client-Service Model. Barmer GEK is reducing the number of its branches by 50 percent, while transitioning to larger and more attractive service centers throughout Germany. More than 90 percent of customers will still be able to reach a service center within 20 minutes. To reach rural areas, mobile branches that can visit homes were created.

- Improved Customer Access. Because Barmer GEK wanted to make it easier for customers to access the company, it invested significantly in online services and full-service call centers. This led to a direct reduction in the number of customers who need to visit branches while maintaining high levels of customer satisfaction.

- Organization Simplification. A pillar of Barmer GEK’s transformation is the centralization and specialization of claim processing. By moving from 80 regional hubs to 40 specialized processing centers, the company is now using specialized administrators—who are more effective and efficient than under the old staffing model—and increased sharing of best practices.

Although Barmer GEK has strategically reduced its workforce in some areas—through proven concepts such as specialization and centralization of core processes—it has invested heavily in areas that are aligned with delivering value to the customer, increasing the number of customer-facing employees across the board. These changes have made Barmer GEK competitive on cost, with expected annual savings exceeding €300 million, as the company continues on its journey to deliver exceptional value to customers. Beyond being described in the German press as a “bold move,” the transformation has laid the groundwork for the successful future of the company.

Nokia’s Leader-Driven Transformation Reinvents the Company (Again)

We all remember Nokia as the company that once dominated the mobile-phone industry but subsequently had to exit that business. What is easily forgotten is that Nokia has radically and successfully reinvented itself several times in its 150-year history. This makes Nokia a prime example of a “serial transformer.”

In 2014, Nokia embarked on perhaps the most radical transformation in its history. During that year, Nokia had to make a radical choice: continue massively investing in its mobile-device business (its largest) or reinvent itself. The device business had been moving toward a difficult stalemate, generating dissatisfactory results and requiring increasing amounts of capital, which Nokia no longer had. At the same time, the company was in a 50-50 joint venture with Siemens—called Nokia Siemens Networks (NSN)—that sold networking equipment. NSN had been undergoing a massive turnaround and cost-reduction program, steadily improving its results.

When Microsoft expressed interest in taking over Nokia’s device business, Nokia chairman Risto Siilasmaa took the initiative. Over the course of six months, he and the executive team evaluated several alternatives and shaped a deal that would radically change Nokia’s trajectory: selling the mobile business to Microsoft. In parallel, Nokia CFO Timo Ihamuotila orchestrated another deal to buy out Siemens from the NSN joint venture, giving Nokia 100 percent control over the unit and forming the cash-generating core of the new Nokia. These deals have proved essential for Nokia to fund the journey. They were well-timed, well-executed moves at the right terms.

Right after these radical announcements, Nokia embarked on a strategy-led design period to win in the medium term with new people and a new organization, with Risto Siilasmaa as chairman and interim CEO. Nokia set up a new portfolio strategy, corporate structure, capital structure, robust business plans, and management team with president and CEO Rajeev Suri in charge. Nokia focused on delivering excellent operational results across its portfolio of three businesses while planning its next move: a leading position in technologies for a world in which everyone and everything will be connected.

Nokia’s share price has steadily climbed. Its enterprise value has grown 12-fold since bottoming out in July 2012. The company has returned billions of dollars of cash to its shareholders and is once again the most valuable company in Finland. The next few years will demonstrate how this chapter in Nokia’s 150-year history of serial transformation will again reinvent the company.

Managing Director & Senior Partner

San Francisco - Bay Area

Managing Director & Senior Partner, Chairman of the BCG Henderson Institute

ABOUT BOSTON CONSULTING GROUP

Boston Consulting Group partners with leaders in business and society to tackle their most important challenges and capture their greatest opportunities. BCG was the pioneer in business strategy when it was founded in 1963. Today, we work closely with clients to embrace a transformational approach aimed at benefiting all stakeholders—empowering organizations to grow, build sustainable competitive advantage, and drive positive societal impact.

Our diverse, global teams bring deep industry and functional expertise and a range of perspectives that question the status quo and spark change. BCG delivers solutions through leading-edge management consulting, technology and design, and corporate and digital ventures. We work in a uniquely collaborative model across the firm and throughout all levels of the client organization, fueled by the goal of helping our clients thrive and enabling them to make the world a better place.

© Boston Consulting Group 2024. All rights reserved.

For information or permission to reprint, please contact BCG at [email protected] . To find the latest BCG content and register to receive e-alerts on this topic or others, please visit bcg.com . Follow Boston Consulting Group on Facebook and X (formerly Twitter) .

Subscribe to our Business Transformation E-Alert.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Quality strategy for transformation: a case study

2011, The TQM Journal

RELATED PAPERS

Januar Aziz Zaenurrohman

International Archives of Nursing and Health Care

Susan Steele-Moses

Robert Markley

Pandamic Sumon

Materials Science and Technology

neville baker

Revista Hispanoamericana de Hernia

Alfredo Moreno Egea

Fiorella Minchola

Troy Buzynski

Ciência Animal Brasileira

José Nörnberg

Innovative Biosystems and Bioengineering

Larysa Bondarenko

Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health

Aga Purwiga

加拿大SFU毕业证书制作 办理西蒙弗雷泽大学毕业证书成绩单修改

Revista médica de Chile

Claudia Morales

The Journal of Neuroscience

Godfrey Getz

Nature Reviews Immunology

Elisabeth Kugelberg

Chemical Science

Max C Holthausen

Bulletin of the American Physical Society

Russell Composto

Abdur Rehman Shah

Colombia: avances y desafíos frente a la delincuencia organizada transnacional

Sello Editorial Escuela Militar de Cadetes

Nanomaterials and Nanotechnology

Sunny Iyuke

Jos Seegers

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, quality strategy for transformation: a case study.

The TQM Journal

ISSN : 1754-2731

Article publication date: 11 January 2011

This paper aims to address the issue of sustainability of excellence in today's turbulent environment and evaluates the effectiveness (to achieve objectives) of quality strategy in a DAP‐winning company.

Design/methodology/approach

A face‐to‐face interview and a literature review were carried out in a case study mode.

The paper finds that total quality management (TQM) implemented in the Deming Application Prize (DAP) framework has a positive effect on business performance. To sustain excellence, it is important to maintain strategic focus, match strategic options with aspirations, link the human resource mission with the company vision, and work for transformation.

Research limitations/implications

Information provided/reported by the case company is fully relied upon and the required data are extracted.

Originality/value

Working definitions of TQM and business excellence are presented and the issue of “transformation” is explored. The study adopts creative approach for identifying critical success factors, discovers the possibility of including “flexibility” as the fifth angle in DAP examination, and proposes a framework for further research.

- Quality management

- Total quality management

- Deming Prize

- Organizational change

- Business excellence

Breja, S.K. , Banwet, D.K. and Iyer, K.C. (2011), "Quality strategy for transformation: a case study", The TQM Journal , Vol. 23 No. 1, pp. 5-20. https://doi.org/10.1108/17542731111097452

Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2011, Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Replicating success: Scaling up quality transformation across a network

This article is part of the 2014 compendium Flawless: From Measuring Failure to Building Quality Robustness in Pharma .

Quality transformations can have tremendous impact—reducing quality incidents by 30 to 50 percent, for instance, or unleashing the energy and capacity of thousands of employees. Transformation in a small pilot area is often successful, but many pharmacos have struggled to replicate the success of a pilot throughout the network. What are the best replication mechanisms?

Transforming quality in an entire organization that comprises thousands of production steps and employees and tens of thousands of SKUs is one of the most difficult challenges for any pharmaceutical company. By nature, every pharmaceutical product is unique, which means its production process cannot be standardized. By nature, every person working on a line is unique, which means a standardized intervention will not always work. Although pharmacos have found that significant management attention can foster a successful pilot of a quality transformation on the shop floor, scaling the transformation across a network has been an elusive goal for many.

What elements do successful transformations at scale have in common? They start with a clear aspiration and feature strong and consistent communication. The transformation’s leaders lead by example and set ambitious but attainable targets and balanced incentives. And the organization is supported with tools, capability building, better practices, and other factors.

However, although successful transformations have common elements, the approaches that companies use to scale up their quality transformations are quite diverse. The starting points to determine the choice of approach are typically the scope of the transformation (a few pain points versus the whole quality system) and the company’s maturity (that is, how much intervention is needed to improve the capabilities and culture). Below are four different approaches, each of which has proven successful in different contexts, and a detailed discussion of how to choose the right one for your company.

Cascading mini-transformations

How it works

This approach breaks down the organization into manageable units (each typically having 50 to 100 full-time equivalents.) The scaling mechanism is a series of heavily structured local transformations, called “mini-transformations” or “mini-T.” 1 1. Alvaro Carpintero, Wolf-Christian Gerstner “Stop fighting fires: Transforming quality on the shop floor one unit at a time,” Flawless: From Measuring Failure to Building Quality Robustness in Pharma , McKinsey & Company, July 2014. Mini-transformations achieve the benefits of scale by repeating the same transformation approach throughout the organization and applying the knowledge gained in early phases to later phases.

Each mini-transformation is achieved through a standardized process conducted in three to four months. It entails simultaneous and radical changes on the three dimensions of operational excellence: operating system, management infrastructure, and mind-sets and capabilities. Intensive engagement of operators and middle management in root-cause problem solving and reducing the gap to best practices can lead to dramatic performance improvements in just a few weeks for a select set of key performance indicators (KPIs)—such as reducing deviations by a factor of 2 or 3 or reducing line clearance events by 40 to 80 percent. The mini-transformation is not only about introducing concrete improvements, however. It also emphasizes leaving behind a mechanism that allows units to continuously develop further improvements.

Why it is successful

The mini-transformation approach succeeds because it creates both tremendous energy in the organization and changes that are visible immediately. Intense coaching, significant attention to capability building, and energy from the bottom up are the ingredients for creating a profound cultural transformation.

When to choose and what it takes

The approach of cascading mini-transformations is best suited to organizations faced with a wide variety of challenges, such as undermotivated teams, an absence of standards or respect for them, too many issues blamed on “human errors,” or a lack of execution discipline. To be fully effective, the approach requires a significant investment in a team of “change agents,” who can help to replicate the transformation throughout the organization. This team (typically representing less than 1 percent of the workforce) is composed of people who have strong skills in problem solving, coaching, and change management. Team members need to be engaged as change agents for two to three years. Often, the speed of the transformation depends on this team’s capacity and effectiveness.

Designing a holistic production system

The holistic production system, derived from the renowned Toyota Production System, aims to bring together elements of the quality system and standard production processes in a comprehensive management philosophy. A production system defines the guiding principles a company uses to run its operations within a business and continuously improve its performance. It is a set of standards, practices, principles, and tools (including lean, Six Sigma, and other change management methods) that fully describe the best-in-class and expected operating practices across the network. In contrast to the formal setup of quality systems oriented toward compliance, production systems put a stronger emphasis on sharing learning and best practices across the network, training and capability building, and developing people. The best production systems are a living knowledge repository, simple to understand (from top management to shop-floor staff), and easy to access.

Production systems ensure that everyone in the enterprise shares the same operational culture, speaks the same language, and applies a standard approach to work. Defining a unique way of working and deploying it gradually across the network can foster dramatic operational improvements, transparent performance levels for plants, and strong internal people development.

Production systems are still relatively rare in pharma but are commonly seen in the automotive, aerospace, and high-tech industries. Benchmarks in those industries have demonstrated that implementing a production system allows companies to build a sustainable competitive advantage.

Production systems are typically implemented in companies after some basic lean or quality skills are in place and well recognized. For example, a company that has gone through the mini-transformation approach will have a significant set of experiences. Best practices emerging from the transformation are then codified into the production system.

Creating a production system requires strong top management involvement, an easy-to-access central repository, and a clear deployment model. To sustain the system, an adequate organization must be in place, along with processes for capability building and practice sharing. Training of new hires, evaluation of people, training modules, and process descriptions all typically need to be closely aligned with the production system. The implementation of the production system is typically accompanied by cultural-change activities.

Setting priorities for process excellence

In this approach, a company selects a few quality processes as priorities for improvement efforts, such as change controls, line clearance, or cleaning validation. It centrally sets ambitions for the processes to attain a certain level of maturity. The selection of the right processes is quite critical, given that the limited scope of this intervention means major shortcomings could be missed if the wrong processes are selected. Therefore, the exercise is often preceded by a thorough, global quality-management-system diagnostic.

From every site in the network, subject matter experts for each process are selected on the basis of their technical skills and their skills as change agents (in particular, collaboration and change management) and are empowered to make decisions. The experts convene for a limited period (up to two weeks) in a “kaizen workshop” to design the process from end to end. The central team travels to the sites, where it checks local against global best practices and prepares the site to adapt the global process design to the local products and processes and to the site’s starting point. The same local quality assurance experts who participated in the global design workshop oversee implementation of the new process in each location.

The process excellence approach works because it offers very precise prescriptions and best practices that are easy to implement.

Convening subject matter experts from each location allows a company to leverage the best knowledge within the organization. The approach also ensures that this knowledge is broadly shared and aligned with as many people in the organization as possible. Success strongly depends on senior management buy-in, in particular the willingness to hold all organizational units to the same standard. This also makes the approach faster to implement than many others.

The process excellence approach works best when the organization recognizes that a few processes have clear weaknesses that need to be fixed fast. It requires strong top-down coordination to gather all the subject matter experts and to prepare for efficient and effective one- to two-week kaizen workshops.

Process changes may be more difficult to sustain, because site-level staff have little influence in the practices chosen by the subject matter experts (unlike for mini- transformations). The team of experts also needs to be careful not to create unnecessarily complex or ineffective processes—because one size does not always fit all. Also, the process excellence approach is truly “one off,” seeking to fix one process or set of processes, rather than setting the stage for continuous improvements.

Unit transformation in a box

“Unit transformation in a box” relies on a structured and fully developed tool kit for a unit or plant that is centrally developed on the basis of benchmarks, existing standards, and best practices among all relevant quality system elements. The tool kit comprises key quality parameters, benchmark metrics, a methodology for target setting, tools for idea generation, and a structure for implementation, among other elements. The organization supports the model through systematic capability building and a leadership development program for the key leaders with on-the-job breakthrough projects pertaining to quality. Such projects, typically almost a year long, help individuals build their leadership skills and learn how to deliver business impact, such as reducing batch failures or improving audit readiness. A continued effort by a central team is vital for this setup to work.

The approach allows all sites to start the transformation simultaneously and to use it “off the shelf.” The use of benchmarks means that there is less requirement for people to travel and review data at different sites. The most beneficial aspect of this model is the ability to significantly increase the pace and scale of the rollout with fewer resources. Because the approach focuses on fast improvements, it allows the organization to make early course corrections to ensure a positive trajectory for impact. This also helps to institutionalize the approach.

Companies should consider choosing this model if they need to accelerate the rollout of a transformation where the challenges are varied but many of the solutions are known. The pace and scale of the transformation make the approach especially useful for high-performing companies engaged in a transformation “from good to great.” Yet the approach does not work as well when the plant still has fundamental issues to be fixed—in that scenario, a more hands-on approach would be required. The approach is also well suited to capturing value in cross-functional areas and in cases in which there are few “low-hanging fruits” for capturing value.

Which approach is right for your company?

The right approach for a company strongly depends on its starting point (Exhibit 1). Companies that face a very significant cultural or capability challenge are better off choosing the mini-transformation approach, because it has the strongest focus on building capabilities and changing mind-sets and behaviors throughout the organization. Companies that want to integrate their lean, Six Sigma, quality, safety, and other approaches throughout the whole organization but that already have reasonably mature culture and capabilities can select a production system approach.

Both these approaches, however, are relatively slower than the others, because they rely on rolling out the transformation across many waves or years and require the organization to dedicate resources over that time period to address all processes throughout the network. The process excellence approach could be called “quick and dirty” in this respect: it is the quickest of the implementation approaches and doesn’t depend on the company having advanced skills and mature culture, but it also focuses least on long-term sustainability. As a result, it works best if there is a well-defined problem that is limited in scope and reasonably similar across sites, and if other mechanisms already exist to guarantee sustainability. Unit transformation in a box combines some characteristics of mini-transformations and process excellence. It is not as resource intensive as mini-transformations, but it requires more top-down steering and a more mature culture. Given the use of a broader tool box, it is slightly more bottom up and flexible than the process excellence approach, but it also carries more implementation risk.

Companies often combine elements of the four approaches and emphasize the elements that are most beneficial in their situation. For example, many companies pursing mini-transformations soon find that their change management process is not equipped to deal with the significantly greater number of changes. In these cases, a quick process excellence intervention on change control processes is often needed to make the mini-transformations effective. Similarly, after running several mini-transformations, some companies choose to put in place systems and approaches for knowledge management that are quite similar to a production system.

To avoid the need for a mid-transformation course change, companies should make a thorough assessment of their starting point before embarking on a transformation. The appropriate scale-up method is easier to evaluate by considering the biggest pain points, the urgency required, and the organization’s capacity to invest in a full quality transformation. In some cases, a few brief site visits can highlight similarities and differences across the network. With regard to quality maturity, a reasonably simple survey concentrated on culture elements such as leadership focus, employee ownership, capabilities, and risk attitude could provide good guidance on the organization’s ability to undertake each type of transformation. 2 2. Katy George, Wolf-Christian Gerstner, Vanya Telpis “Effective quality metrics: The starting point of quality management,” Flawless: From Measuring Failure to Building Quality Robustness in Pharma , McKinsey & Company, July 2014.

The benefits of quality transformation are substantial—but the energy, willpower, resources, and investment required to get the transformation right can be daunting. To overcome the challenges, pharmacos need to invest in carefully designing the dominant architecture for the transformation. What works in your culture? What works in your enterprise? There are many ways to Rome—but all of them are easier if you have a clear map to guide your approach.

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Henrik Jørck Nielsen and Eric Auschitzky to this article.

Sasikanth Dola is an associate principal in McKinsey's Mumbai office, Jean-Baptiste Pelletier is a principal in the Lyon office, Lorenzo Positano is an associate principal in the Rome office, and Paul Rutten is a principal in the Amsterdam office.

Explore a career with us

5 Lessons from Bostik's Quality Culture Transformation [Case Study]

Follow @MrG00dwin

But how is this accomplished? What steps and initiatives must a company take to align its culture to meet the goals and objectives of continuously improving quality?

Providing perspective on this, LNS Research had the opporutnity in December 2013 to speak with Louis Cheung, Head of Quality & Supply Chain for the Americas Region of Bostik Corporation, a global adhesives supplier. In the conversation, Cheung shared his experiences with transforming quality culture and standardizing processes at his company to improve performance and create a more customer-driven operation.

Below, we'll share our key findings from this case study. The whole report can be downloaded here for a more in-depth analysis.

Shifting Culture and Building Effective Leadership

Bostik is a division of French oil and gas giant, Total, S.A. With approximately 47 manufacturing sites and a workforce of around 4,800 people across 50 countries, its annual revenue exceeds $2 billion.

Although the company had strong quality processes, systems, and development expertise, due to its history of mergers and acquisitions, it faced a number of cultural challenges from this legacy stemming from a structural shift in the value chain and the diversity of customer practices and needs. Louis Cheung played a major role in this transformation. Below are five major lessons to take from his experiences.

1. Change Your Thinking and Approach

With a new CEO at the helm in 2010 focused on initiating a global company transformation, one of the overall goals at Bostik was to unify and reorganize company culture and streamline processes. The first crucial step was to engrain a change of perception around quality—from it being throught of as a “department” to a shared responsibility. Cheung explained that the company has an expansive, end-to-end view of quality that is always top-of-mind.

“We look at quality to be in everything that we do across the entire supply chain from the time that demand is identified,” said Cheung.

Tweet this lesson

2. Define and Cultivate Effective Leadership

Of the many important traits of effective quality leadership , Cheung believes the two most important in shifting culture are:

- Unconditional accountability and responsibility

- The ability to be a mobilizer for the entire organization

The “buck stops with me” mentality is vital in ensuring tasks are carried out. Leaders need to be continually searching for ways to improve their respective functions as related to suppliers and other functions in the value chain, as they are constantly in flux. The second bullet point refers to a “go-getter” confident in sharing his or her insight with others to act as an agent of change within the organization.

3. Focus on Roles and Responsibilities, Not Titles

Bostik has moved away from traditional titles like “director” or “manager” and changed to ones based on the specific roles that leaders perform and are responsible for. Building on this concept, leaders’ evaluation and compensation is based more on span of influence than their number of direct reports. Additionally, the company has developed a formalized succession plan to ensure uninterrupted leadership.

4. Extend Leadership Down to the Center of the Organization

In ensuring that the organizational focus on quality extends throughout departments, Cheung has also focused on extending leadership and decision-making to the center of the organization, rather than having the executive level dictate all decisions.

This means that contributions to thought leadership and best practices around quality and supply chain operations are expected to come from local management as well as the top level . Even when these leaders may not have direct reports into their roles, they are still required to guide and influence the organization’s Continuous Improvement initiatives.

5. Enforce Your New Business Model with Proven Tools and Methodologies

Bostik has implemented a set of tools and training programs to support this cultural shift that are based on Lean, Six Sigma, and various inventory and project management tools to aid employees in cross-functional collaboration and executing the business plan.

Last year, the company created an Office of Continuous Improvement (OCI) that staffed Lean, Six Sigma, and project management experts to be full-time agents of change within the company. The goals of the OCI are to develop future leaders in these programs and to extend the mindset of Continuous Improvement throughout the organization.

Bostik Improvements in Quality Metrics to Date

Though Bostik is less than a year into this cultural shift initiative, Cheung noted a few examples of measurable improvements in the following areas:

- Standard process capability (CpK)

- New Product Request (NPR)

- Increased inventory turn

Key Takeaways from Bostik

Transforming a quality culture is a lofty goal for sure, but it’s critical to achieving long-term goals and Operational Excellence. By instilling a mindset of unconditional accountability and shared leadership responsibility across organizational functions and supporting this with proven tools and methodologies, organizations can create an atmosphere of continuous improvement that results in better operational execution to meet business goals.

Cheung spoke at LNS Research's Global Executive Council in 2013. To find out more about our Global Executive Council Meetings, follow this link . The next meeting is scheduled for March 6, and is on the topic of managing supplier quality in today's complex global economy.

Subscribe Now

Become an lns research member.

As a member-level partner of LNS Research, you will receive our expert and proven Advisory Services. These exclusive benefits give your team:

- Regular advisory sessions with our highly experienced LNS Research Analysts

- Access to the complete LNS Research Library

- Participation in members-only executive Roundtable events

- Important, continuous knowledge of Industrial Transformation (IX)

Let us help you with key decisions based on our solid research methodology and vast industrial experience.

Trending Now

The Definitive Guide to Manufacturing Acronyms

Understanding Out-of-the-Box vs. Configured vs. Customized Software

28 Manufacturing Metrics that Actually Matter (The Ones We Rely On)

The Emerson – AspenTech Merger and the Need for Speed

What’s the Difference Between MOM & MES?

What Our Analysts Are Saying

- Allison Kuhn (20)

- Andrew Hughes (77)

- Bob Francis (9)

- Chris Follis (4)

- Dan Jacob (86)

- Dan Miklovic (170)

- Diane Murray (30)

- Greg Goodwin (89)

- James Wells (25)

- Jason Kasper (31)

- Joe Perino (50)

- LNS Research (1)

- Mark Davidson (63)

- Matthew Littlefield (214)

- Mehul Shah (24)

- Niels Andersen (9)

- Patrick Fetterman (13)

- Peter S Bussey (71)

- | Research Team | (344)

- Tom Comstock (50)

- Vivek Murugesan (26)

Similar posts

Companies with eqms outperform others in oee performance [data].

Learn which Enterprise Quality Management Software Functionalities organizations are using to realize improvement in the OEE metric.

5 EQMS Vendors to Consider for Global Roll-Outs in Life Sciences

Learn about the top providers of enterprise quality management software solutions for global life sciences organizations.

How a Large Company Overcame Quality Disconnect with EQMS [Case Study]

Learn how a global organization brought together disconnected IT and quality management systems to drive improvements in business performance.

SUBSCRIBE TO THE LNS RESEARCH BLOG

Stay on top of the latest industrial transformation insights from our expert analysts.

The Industrial Transformation and Operational Excellence Blog is an informal environment for our analysts to share thoughts and insights on a range of technology and business topics.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Inside IKEA’s Digital Transformation

- Thomas Stackpole

A Q&A with Barbara Martin Coppola, IKEA Retail’s chief digital officer.

How does going digital change a legacy retail brand? According to Barbara Martin Coppola, CDO at IKEA Retail, it’s a challenge of remaining fundamentally the same company while doing almost everything differently. In this Q&A, Martin Coppola talks about how working in tech for 20 years prepared her for this challenge, why giving customers control over their data is good business, and how to stay focused on the core mission when you’re changing everything else.

What does it mean for one of the world’s most recognizable retail brands to go digital? For almost 80 years, IKEA has been in the very analogue business of selling its distinct brand of home goods to people. Three years ago, IKEA Retail (Ingka Group) hired Barbara Martin Coppola — a veteran of Google, Samsung, and Texas Instruments — to guide the company through a digital transformation and help it enter the next era of its history. HBR spoke with Martin Coppola about the particular challenge of transformation at a legacy company, how to sustain your culture when you’re changing almost everything, and how her 20 years in the tech industry prepared her for this task.

- Thomas Stackpole is a senior editor at Harvard Business Review.

Partner Center

Leading a Retail Major Through a Successful Quality Engineering Transformation

InfoVision brought about a complete outcome-driven quality engineering transformation for a global retail major, with a focus on capability building and future-proofing.

Download Now

Explore how InfoVision instilled an ‘automation first’ approach to achieve exceptional ROI

2.5X Increase in Automation Development Speed

25% Efficiency Improvement

2X Coverage Improvement

End-To-End Ownership Of Our Customer’s Quality Engineering Transformation

To drive an impactful change, we applied a global delivery model and a seamless implementation strategy. We utilized the following key principles to bring about Quality Engineering transformation:

Higher Test coverage

Automation First Approach

Continuous Testing

3 Case Studies on Digital Quality Transformation

Hear from Michael Jovanis, Vice President, Vault Quality, on how top pharma companies are implementing QMS and the business impacts they are seeing.

Learn how you can enable proactive quality management .

Interested in learning more about how Veeva can help?

The New Equation

Executive leadership hub - What’s important to the C-suite?

Tech Effect

Shared success benefits

Loading Results

No Match Found

All in on digital transformation: Creating a stronger, nimbler, more resilient PwC

/content/dam/pwc/us/en/library/case-studies/assets/case-study-logo-pwc-v2.svg

Business and professional services

Changing how business gets done with BXT, automation and a focus on people

BXT <br/> Emerging Tech

Growth was strong, but costs and frustrations were rising

For more than 165 years, PwC was known for delivering high quality services and for being a place where employees could thrive. But we knew we needed to raise the bar even higher to meet the demands of the digital age. We had to keep growing, make work less manual and more data-driven for our people and deliver an ever-better and more tech-driven experience for clients. And we had to do it without costs getting out of control.

Our business was growing, but costs were rising even faster. So were tech-related frustrations among our employees. If we didn’t make changes we’d fall behind our competitors and our financial goals, and most importantly, be unable to deliver for our clients and our people.

We needed to go all in on a digital transformation to change the course of the firm and to bring our people with us into the future. That meant overhauling our business from the inside out to be more nimble, cut unnecessary costs, increase automation and allow people to do more meaningful work. If we could stop doing the things that weren’t productive or helping us get to those outcomes, we could invest those dollars into technology, experiences and strategies that would help drive the business forward. We had to reinvest to secure our future in a way that would bring our strategy to life and provide return on our investment. As critical: we had to stay focused on our shared values and purpose and keep our people and culture at the heart of these changes. This was going to be a community effort, even the hard parts, from the start. The transformation had to make all of us stronger, more resilient and much more agile.

Key drivers for our change

What drives change? It’s never just one thing. These triggers, combined, drove our transformation. They’re not so different from the motivations of many companies. The difference: We dove in and are seeing the results.

In 2016, leadership changes within PwC prompted a new strategic direction that more clearly aligned our organization with our values and purpose to support long-term sustainable growth. We focused on why we do what we do, what we want to achieve, and how we could innovate the way we do it.

Workforce of the Future

New leadership

In 2016, PwC set a new strategic direction

For nearly a decade, our revenues continued to grow each year, but costs to run the firm were increasing faster. We applied PwC’s own Fit for Growth approach to streamline processes and technology, enabling our people to help drive efficiencies and reduce cost to run the business.

Fit for Growth

Profit pressures

Costs to run the firm were increasing

We knew we had to disrupt how we work to meet our clients’ demand for more value, higher quality and a technology-enabled experience, at a lower cost. We leveraged cost savings to strategically reinvest in our people, processes and technology.

Growth strategy

We knew we had to disrupt how we work

Our people wanted skills to remain relevant in a digital world and be leaders in their field. We invested in tools, technologies and our people to help future-proof our workforce and establish a continuous improvement culture.

New World. New Skills.

Workforce Transformation

Our people wanted skills to grow in their careers

By listening to the “voice of the customer,” we identified pain points in functions and processes that were slowing our people down. We invested in cloud technology and used human-centered design to help improve the customer experience across business services functions.

Finance transformation

IT transformation

Legacy processes

Outdated processes and technologies were slowing us down

We needed a way to empower people to develop and share citizen-led innovations across the firm. We established a technology strategy arm to centralize intellectual property IP and help us efficiently address clients’ needs.

Workforce productivity

We needed to enable our people to create efficiencies and work smarter

A people-first approach to save time and money, and boost the client experience

We began our digital transformation in 2016 by examining PwC Business Services, our back office and shared services center and functions, located primarily in Tampa, Florida. We identified operational improvements that could reduce costs and reinvested some of those savings into a transformation, based on PwC’s Fit for Growth methodology. We committed to “leave no one behind” with a firm-wide program that would help both accelerate adoption and upskill employees.

Bringing together people with business strategy focus (B), human-centered design experience (X), along with the right technologies (T), we used our BXT approach to plan, develop and implement solutions together.

The only way we could transform our back office was to put the experience of our people first. We needed to know exactly where the pain points were in Business Services. First, we sent a survey to our 3,500 partners, asking what slowed down their work and the work of the people who worked for them.

By tapping into the entire community, we quickly identified 25 processes that had to change, including human resources, learning and development, finance, IT, real estate and administrative services. Everyone had something to address to help transform our process and our people, especially since our processes impact multiple activities.

We also asked leaders of our individual Business Services functions to help us figure out how to use that information to create more value from our transformation for the people who do the work day to day. And that also had to create a better user experience for their people. They identified approximately $100 million in cost savings, largely from eliminating manual and repetitive activities that took up employee time. As importantly, these leaders, with the help of their teams, identified areas that would benefit from investments in automation as well as other types of service delivery. Every leader and staffer also thought about what new skills were needed to help our people deliver greater value.

Ultimately, all of this would bring our back office talents to the “front office” to help our client service teams develop products and services that benefit our clients and society.

“Going all-in on digital transformation has made us resilient in a turbulent 2020, allowing us to be nimble and meet the evolving needs of our people and seamlessly guide our clients through some of the toughest decisions of their careers.”

Tim Ryan US Chairman and Senior Partner, PwC

Toss what isn’t working and strategically re-invest in what works for the future

We needed to focus on a strategy that could simplify our business and invest in new, technology-focused areas. We focused on automation to help eliminate transaction-related inefficiencies, and we launched a new intranet and cognitive assistant that gets stronger as it integrates with other applications. It helps our people do almost everything from resetting passwords to recording time, quickly and easily, to save them time for more important tasks and the firm money to reinvest in the transformation.

We aim to build innovative technology solutions that differentiate us from our competitors and digitize the business. From a business strategy perspective, putting flexible and adaptive processes in place helped us create an industry-leading back office that’s able to meet the needs of our business faster, while generating better insights, and at a lower cost of delivery.

Part of that included a strategic decision to invest in upskilling programs so our 55,000 people could learn how to use digital tools for data visualization as well as automation, data cleansing and more. If our people could use these tools to solve common problems, they’d help us become more efficient and growth-oriented now and more innovative later in Business Services and beyond. Now, employees are learning to build bots – over 2,400 have been created so far – to automate workflows. We continue to invest to make processes more intuitive using machine learning and eventually artificial intelligence (AI). These are key to working faster and solving problems differently for ourselves and our clients.

Making everything easier, faster and more intuitive

We know that the way people work will keep changing, which is why we have worked hard to create a culture of infinite learning where everyone can understand and feel connected to our organization’s purpose, values and goals. That required reassessment of how our people would adapt and learn, and importantly, apply what they learned immediately (which is a better way to incorporate training and new skills). We had to inspire people to challenge themselves and make it stick. We brought together people from individual functions—from finance to human resources—and had client services professionals from across the firm join in for a BXT-style session and used what we learned from our Partner survey as a guide.

We wanted better insights from the data we were gathering. That meant improving self-service options, for people to build automations themselves to help make their work easier. This was key to changing the experience for our people. Getting there hinged on a culture of citizen-led digital innovation , introduced through digital academies for our people so they could learn how to make data work harder, faster. Rather than just offer up a process and press go, we taught everyone how to make their own automations.

We also selected people across the firm to become digital ambassadors, training them with deeper experiences in digital, agile thinking and problem solving so they could go back to their teammates and bring them forward. Creating easy and usable interfaces, quick courses and incentives has made it simpler for employees to create and use our automation tools, which in turn helps them reduce their time spent on repetitive tasks. We created an interactive lab for our people to collaborate on and share new automations and ideas, incenting time spent exploring and creating. And digital badges let our people learn and earn credentials.

We began to see time and cost savings as people applied the new tools and learnings in their day-to-day work. More than this, we saw our culture shift to one of innovation and experimentation.

“We were trying to get to new ways of doing things faster and better, and at a lower cost for us and our clients. And if you can't replicate that across all employees, then it's not going to be a success. You're just going to have little pockets of change.”

Joe Killian US Finance and Shared Services Leader, PwC

Simplify, integrate, scale and innovate for the win

To succeed, we needed to streamline processes, from contracts to our firm-wide analytics platform. We invested in and adopted Robotics Process Automation (RPA) and Business Process Integration (BPI), which helped automate a lot of the transactional work we do. We also replaced hundreds of pages of written business rules with an automated process and as a result, created a more intuitive experience for client service professionals. At the same time, we adopted user friendly, mobile cloud solutions to provide self-service access to data and insights that help meet the needs of our people no matter where they are working. This end-to-end automation transformed processes to help eliminate inefficiencies in our routine transactions.

By investing more in data analytics and artificial intelligence to pull data from disparate systems and platforms into one visual dashboard, we get a snapshot into team performance and business metrics. This will easily integrate and give more insights as a new intranet and cognitive digital assistant are added. The system can also nudge people to take important actions and meet critical deadlines.

Saving, improving and change at every level

Simplifying helped us save millions of dollars and created a workforce that is more satisfied, productive and skilled. We eliminated more than 50 processes in Business Services to save money and time. For example, simplifying with RPA has allowed us to reduce the time it takes to complete a contract by as much as 80%. Many manual processes are now automated. Data to drive insights is easy to pull, analyze and visualize so every team can make decisions more confidently.

In fiscal 2019, we saved almost 160,000 hours through automation across our Internal Firm Services functions including administrative support, controller operations, HR shared services and real estate operations.

A focused investment in our people and their skills changed the culture and abilities at the firm—jobs and functions that either did not exist or required external hires can now be filled by our own staff. Learning & Development (L&D) expanded virtual training programs to help reduce resource needs and travel costs—which made continuing and enhancing training when travel stopped due to the pandemic simple and seamless.

More than this, the firm is agile, more purpose-focused and people-driven. We’re better positioned to control costs and the quality of Business Services is higher than ever.

Results by function:

A focus on digital upskilling, tighter coordination through an end-to-end process that lasered in on collaboration among teams and technologies and automating once-manual processes, helped drive our transformation. Every back office function in Business Services improved some processes and eliminated certain costs, though headcount in the division declined by just 2% overall.

Information technology

Administrative services, learning and development, security and real estate, human resources, acceleration centers.

We shifted from a traditional waterfall delivery approach toward agile delivery using the scrum framework where people work in short sprints and solve problems as they arise, to deliver value quickly and continuously. IT filled more than 100 positions within six months to equip the team with the skills needed to make change real. That meant hiring scrum masters to embed agile principles in delivery teams, developers and cloud engineers to help build strong technology and application development skill sets.

Our IT transformation has been instrumental in helping drive change companywide and delivering the firm’s tech-enabled priorities. Everyone in IT, regardless of their role, is trained in agile methodology and lean process training, the backbone of this new way of working. Business owners now have a closely linked IT team leader for end-to-end collaboration – in many cases, they no longer have to move between different groups. Leaders are also learning agile methodology to work alongside IT. The agile model is helping to vastly improve the employee experience across our teams, and that is helping lead to better outcomes.

We used to have a 1:1 ratio of executive assistants to senior leaders. Now our administrative services work with people throughout the firm via a centralized, virtual executive concierge structure. Our teams pool resources and while they still specialize, they’re also getting broader experience. As a result, people are better able to support client teams tackling specific problems that in the past 1:1 assistants might never have encountered. We adopted human-centered approaches to help keep the culture of trusted relationships alive. “We provided new hires with rigorous onboarding and training, which was a combination of existing soft skills, technical skills, and teaming activities so they can rely on one another to help deliver white-glove service,” said Jose Limardo, Support Operations Leader.

Four of the top nine issues identified in the initial 2016 assessment were finance-related processes. The insights gleaned from the finance function’s challenges helped validate and steer our entire transformation efforts. “It was painfully obvious we had a user experience problem that we needed to fix,” said Controller Tom Alexander. The group, which wanted to be an industry leading, modern finance team, allocated resources to innovation and shifted their culture to help drive continuous improvement. They reimagined the way they work by adopting a structure centered on the skills needed to succeed and scale.

The Controller Operations (CO) saved 30,000 hours each year for nearly four years by automating repetitive tasks, reimagining processes and applying more agile ways of working, which has led to efficiencies, improved job satisfaction and more time spent on activities that are adding value. Today, more than 40% of the Controller Operations team consists of data engineers, data scientists and data architects who are helping to pinpoint and address the business’s data needs.

As we continue to upskill people, we are making L&D a better experience. We shifted 70% in-person training to about 40% in-person, and created a virtual learning environment and infrastructure that made for seamless delivery when the pandemic of 2020 turned our workforce remote. As a result, the firm saved nearly $70 million, while also saving our people the burden of travel and hotel stays.

PwC’s security team uses a tool that enables our people to report back to us during a critical event, whether in office, during travel or at a client site, instead of piecing together information from different systems. This has proven to be invaluable for our employees throughout the pandemic and during natural disasters. But it doesn’t stop there. Our real estate business intelligence teams are using occupancy sensors to gather data about how workspaces are used. Through dashboards and data visualization tools, they are turning millions of reports into clear snapshots of how people use workspaces today and how they may be used over the next three to five years.

Our HR professionals have always been a repository of institutional knowledge of our business and operations. We developed an internal platform to help automate staffing needs. It is a go-to for teams to look at skills and availability of staff, and to help forecast engagement needs and assign our internal client service staff to those projects. The process of staffing and projecting now takes minutes, not days. Leveraging automation in the platform can help significantly reduce the resources and time required to process information that’s needed in order to staff an engagement. As a result, we are able to move our own people to higher-value work.

Over the last few years, PwC Business Services has automated about 400,000 hours of work that would have otherwise been done by our client service professionals, on- or offshore, or by third parties. Our Acceleration Centers (ACs) have been at the heart of this transformation, helping drive new, digital ways of working and creating savings for our firm and our clients. For our back offices alone, this translated into cost savings of around $50 million for work that was previously done by third parties.

Since 2018, PwC Labs has become integral to our technology strategy. We are empowering our people and our clients to reach their digital potential, at scale. We are leading the charge on creating innovative solutions designed for humans, driven by data, that utilize intelligent automation. Our people are reimagining how we build technology, collaborate and improve the quality of our deliverables. By embedding the latest AI and automation into our culture, our people can develop a growing digital inventory that can be tailored to meeting our clients’ unique needs.

Explore PwC's case study library

Share this case study.

See how PwC transformed its business services and finance groups through BXT, automation and a focus on people.

{{filterContent.facetedTitle}}

{{item.publishDate}}

{{item.title}}

{{item.text}}

Joe Killian

US/MX Business Services Leader & Tampa Campus Leader, PwC US

Dr. Deniz Caglar

Principal, Strategy&, Strategy& US

Thank you for your interest in PwC

We have received your information. Should you need to refer back to this submission in the future, please use reference number "refID" .

Required fields are marked with an asterisk( * )

Please correct the errors and send your information again.

By submitting your email address, you acknowledge that you have read the Privacy Statement and that you consent to our processing data in accordance with the Privacy Statement (including international transfers). If you change your mind at any time about wishing to receive the information from us, you can send us an email message using the Contact Us page.

© 2017 - 2024 PwC. All rights reserved. PwC refers to the PwC network and/or one or more of its member firms, each of which is a separate legal entity. Please see www.pwc.com/structure for further details.

- Data Privacy Framework

- Cookie info

- Terms and conditions

- Site provider

- Your Privacy Choices

Federal Facilities Beyond the 1990s: Ensuring Quality in an Era of Limited Resources: Summary of a Symposium (1997)

Chapter: organization transformation: a case study, organizational transformation: a case study.

Charles I. Homan

Michael Baker Corporation

The Michael Baker Corporation provides a case study of a private sector organization in transition. About one-third of our business is with federal agencies. I personally work often with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). In the past few years, FEMA, like my company, has undergone great change. I have been able to draw on many of the strategies that Director James Lee Witt employed at FEMA.

The Michael Baker Corporation—a highly diversified engineering, construction, and operations and maintenance firm—was very successful until the 1990s. In the mid-1980s, we began to change the core of our business. Around 1993, we reached a crisis. But we have begun to succeed in turning the company around.

The company was founded in 1940 near Pittsburgh. In 1995, we had revenues of $355 million. The company's 3,200 employees hold 42 percent of the stock of the publicly traded firm. Nearly 85 percent of the eligible employees hold stock, giving the company good access to capital and the employees a liquid form of participation (upon retirement). This is not always the case in employee stock ownership plans. Baker's offices are mainly on the East and Gulf coasts, with a few offices overseas.

The Roots of Crisis

Figure 1 traces some of the roots of the recent crisis. In 1983, the company was restructured. Michael Baker, Jr., the founder, had died in 1977, and the company had not prepared new leadership at that time. By

Figure 1.

Revenue and market value of the Michael Baker Corporation 1983 to present.

the early 1980s the company was in trouble, intensified by the recession in the Pittsburgh area. The employee stock ownership plan was formed at that time, to give employees the incentives of ownership. Baker began to perform well, concentrating on its core engineering business.

In 1987, the company made its first acquisition. The object was to diversify the company, moving into operations and maintenance, and ultimately construction. We saw the coming trends of outsourcing, privatization, and design-build, and we wanted to position the company to take advantage of them. Baker acquired three companies that operate and maintain facilities: one that operates public facilities, and two that operate private facilities in oil and gas. Then, in 1991, we acquired the Mellon-Stuart Construction Company in Pittsburgh.

Revenue began to grow rapidly, peaking at about $430 million in 1994. We proceeded to lose $20 million in 1993, and another $10 million the next year, by failing to understand, integrate, and control the acquired companies. The company's market value, which had grown significantly along with revenues and profits, dropped, too. However, we did complete those projects we were committed to.

Deep financial losses damaged our credibility with all of our constituencies except, perhaps, our clients, with whom we maintained our standards of service and commitment. The financial community was frustrated with Baker, as were employees and other shareholders.

We experienced significant litigation. We had taken over a construction company that had a culture of litigation and adversarial relations with clients. Many construction companies share that attitude. The Baker Company had not only litigation to resolve, but a corporate culture to change.

Baker's long-standing credit facility was withdrawn by the bank in the fourth quarter of 1994, at a time when the company had $15 million borrowed on that facility. Baker was in a difficult situation.

The company also faced growing competition, especially in the individual areas of engineering, construction, and operations.

Organizational Transformation

We needed to change the company dramatically and very immediately, and we needed to do it so that we could be profitable in 1995. The company began to transform itself to meet these challenges. With all

of the bad news, we did have a few advantages. First, the market was changing rapidly. If we could create an entrepreneurial organization that was creative and innovative, we could take advantage of that market change.

Baker also had a very strong core engineering business, operating rather independently of the other businesses. It had a strong internal infrastructure (including project management, finance, and technology) and an excellent, seasoned management team. It had done many things right, such as implementing a total quality management practice in 1991, which touched every major process in the company.

The board of directors made a national search for a chief executive officer and was leaning toward an outsider, because they recognized that we needed significant change. But, with my understanding of the company, and working with key people from the engineering part of the company, I was able to put together a restructuring plan to present to the board. I knew that I had to take a great deal of risk. When Baker competes for projects, if we think we have a good position we tend to be cautious. But if not, we take some risks. I felt I was in that position. The board accepted the plan.

The approach, briefly, was threefold:

- Build on strengths . Our central strength was the core engineering business, which now had the design-build-operate capability of which the marketplace was demanding more. Another strength was our established reputation; we had served our clients well throughout this time. Market trends were positive for the company; as I noted, the market has been full of change, which has been helpful.

- Remove barriers . One serious barrier was the managers of the acquired companies, who did not share the values of Baker's engineering culture.

- Fix weaknesses . Weaknesses existed mainly in reporting systems, human resources, and technology—all those infrastructure systems that make an organization healthy.