- Open access

- Published: 30 August 2021

Online teaching in physiotherapy education during COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: a retrospective case-control study on students’ satisfaction and performance

- Giacomo Rossettini 1 na1 ,

- Tommaso Geri 2 na1 ,

- Andrea Turolla 3 ,

- Antonello Viceconti 4 ,

- Cristina Scumà 1 ,

- Mattia Mirandola 1 ,

- Andrea Dell’Isola 5 , 6 ,

- Silvia Gianola 7 ,

- Filippo Maselli 4 , 8 &

- Alvisa Palese 9

BMC Medical Education volume 21 , Article number: 456 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

6838 Accesses

45 Citations

12 Altmetric

Metrics details

During COVID-19 pandemic, physiotherapy lecturers faced the challenge of rapidly shifting from face-to-face to online education. This retrospective case-control study aims to compare students’ satisfaction and performances shown in an online course to a control group of students who underwent the same course delivered face-to-face in the previous five years.

Between March and April 2020, a class (n = 46) of entry-level physiotherapy students (University of Verona - Italy), trained by an experienced physiotherapist, had 24-hours online lessons. Students exposed to the same course in the previous five academic years (n = 112), delivered with face-to-face conventional lessons, served as a historical control. The course was organized in 3 sequential phases: (1) PowerPoint presentations were uploaded to the University online platform, (2) asynchronous video recorded lectures were provided on the same platform, and (3) between online lectures, the lecturer and students could communicate through an email chat to promote understanding, dispel any doubts and collect requests for supplementary material (e.g., scientific articles, videos, webinars, podcasts). Outcomes were: (1) satisfaction as routinely measured by University with a national instrument and populated in a database; (2) performance as measured with an oral examination.

We compared satisfaction with the course, expressed on a 5-point Likert scale, resulting in no differences between online and face-to-face teaching (Kruskal-Wallis 2 = 0.24, df = 1, p = 0.62). We weighted up students’ results by comparing their mean performances with the mean performances of the same course delivered face-to-face in the previous five years, founding a statistical significance in favour of online teaching (Wilcoxon rank sum test W = 1665, p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Online teaching in entry-level Physiotherapy seems to be a feasible option to face COVID-19 pandemic, as satisfies students as well as face-to-face courses and leading to a similar performance. Entry-level Bachelors in Physiotherapy may consider moving to eLearning to facilitate access to higher education. Universities will have to train lecturers to help them develop appropriate pedagogical skills, and supply suitable support in terms of economic, organizational, and technological issues, aimed at guaranteeing a high level of education to their students.

Trial registration

Retrospectively registered.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The ongoing Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is still challenging educational systems worldwide. In those countries where governments decided to close educational institutions in an attempt to contain the spreading of the disease, students could not attend face-to-face activities [ 1 ]. Italy was particularly affected, with COVID-19 cases soaring already in February 2020 and lockdowns implemented as early as the 9th of March 2020 forcing all the educational institutions (from primary schools to universities) to switch to online learning [ 2 , 3 ]. Within this context, the online teaching was unprecedented for different institutions, as for the entry-level Bachelor in Physiotherapy [ 4 ].

With no time for extensive training on online teaching and learning and no possibility to change the course contents, physiotherapy lecturers were faced with the challenge of effectively teaching core skills to entry-level physiotherapy students online, assuring the same competence level gained by their predecessors [ 5 ]. In the meanwhile, physiotherapy students, who were already experiencing the impact of the pandemic on their psychosocial wellbeing, had to manage the amplification of the level of negative emotions due to rapid changes in learning habits [ 6 , 7 ].

Even if former systematic reviews reported that distance-online learning arouses the same satisfaction and has the same efficacy as traditional face-to-face teaching in physiotherapy [ 8 , 9 , 10 ], the protected experimental setting in which the included studies were conducted limits the external validity of the findings to the ongoing pandemic. A recent meta-synthesis investigated accessibility and educational methods of online education in the medical curriculum during the COVID-19 pandemic but none of the included studies investigated satisfaction and performance [ 11 ]. Thus, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first comparative study developed during COVID-19 pandemic that quantitatively evaluates students’ satisfaction and performances after attending online physiotherapy education.

Accordingly, the aims of this retrospective case-control study are: (1) to investigate students’ satisfaction and performance; and (2) to compare their degree of satisfaction and performance with those reported by students attending face-to-face courses.

Study design

This case-control study was developed using guidance and explanations from the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines [ 12 , 13 ].

We conducted this study in compliance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was assumed when respondents completed and submitted the survey after reading the purpose statement of the study, strategies to ensure confidentiality and privacy of the data collected. Data were fully and irreversibly anonymized by generalization of important variables [ 14 ]. Ethics approval during this pandemic was not required according to the “Ethics and data protection” regulations of the European advisory body and European Commission [ 14 , 15 , 16 ].

“Advanced methodologies in musculoskeletal physiotherapy” lectures at the entry-level Bachelor in Physiotherapy have been shifted from a face-to-face to an online course in only two weeks. Before and during the pandemic, the course covers 3 main topics: clinical reasoning, analysis of pain mechanisms and evidence-based physiotherapy practice. It provides 2 ECTS (European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System), with an estimated learning workload of 50–60 h of study, of which 24 were usually fulfilled by face-to-face lectures [ 17 ].

A physiotherapist lecturer with twelve years of teaching experience in musculoskeletal physiotherapy designed and conducted the course at the University of Verona - Italy for entry-level physiotherapy students. During the weeks between the outbreak of the pandemic and the teaching of the course, the lecturer was trained by the University exclusively on the use of the online platform (how to access the system; how to record lectures; and how to upload learning materials) during a 1-hour online course. No further training on how to prepare the online teaching and how to adapt the learning content was provided.

The course was delivered online between the end of March and the end of April 2020 adopting the Panopto Secure Online Videoplatform [ 18 ]. Students’ attendance was recorded automatically by The Panopto Secure Online Videoplatform as the students accessed the lectures.

The course was organized in 3 sequential phases:

Power-point presentations were uploaded to the University online platform, one to briefly introduce students to the course, and the others to serve as lecture notes.

One week after the upload, asynchronous video recorded lectures were provided on the same platform. Each lesson lasted a maximum of 30 min [ 19 ] and included the explanation of the topic approached, a summary of the key points and a clinical case focused on the subject proposed.

Between online lectures, the lecturer and students could communicate through an email chat to promote understanding, dispel any doubts and collect requests for supplementary materials. Accordingly, the lecturer provided supplementary references (e.g., scientific articles, videos), also suggesting online resources (e.g., webinars and podcasts) to enhance the effectiveness of the course.

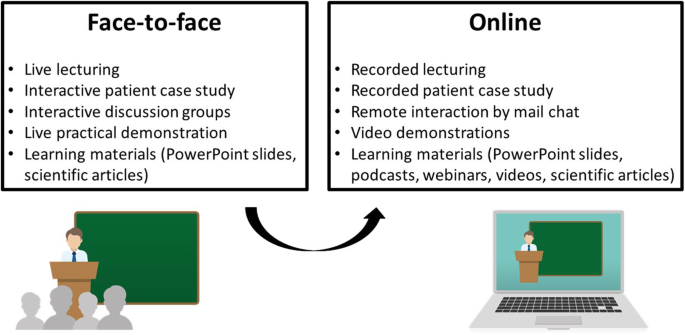

The previous five editions of the course, homogeneous in the aims and the contents, were conducted by the same lecturer. The same Syllabus developed for the face-to-face course and provided to former students was uploaded for the online edition. The admission to the oral exam was bound to 100 % attendance to the lectures both in the online and face-to-face editions. The educational strategies adopted during the transition from face-to-face to online teaching are presented in Fig. 1 .

Changes in teaching strategies adopted during the transition from face-to-face to online education.

Participants

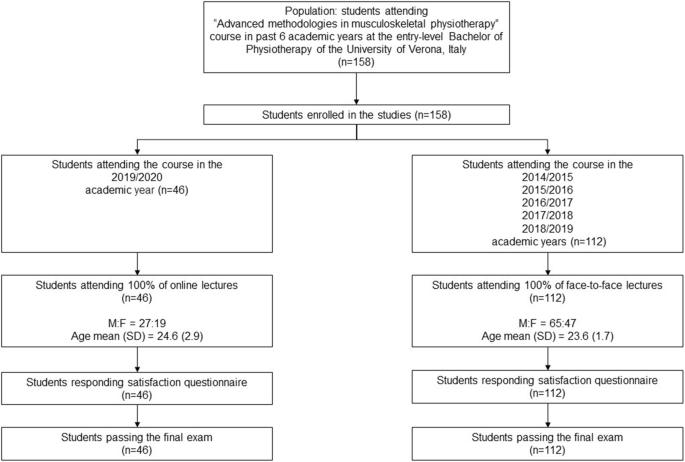

Convenience samples for both cases and controls were considered. Students attending the course in the 2019/2020 academic year, exposed to online teaching, were considered as the online group (n = 46). Students exposed to the same course taught face-to-face in the previous five academic years ( n = 112) were considered as a control group (face-to-face group).

Data collection and Outcome Measures

Demographic (e.g., age and gender) and course (e.g., number of participants attending the course, number of respondents, number of passed students) characteristics were collected. The primary outcomes of interest were students’ satisfaction and performance.

The assessment of students’ satisfaction was obtained from a standardized national-established 12-item questionnaire whose compilation by students is mandatory and takes place before the final exam of each course taught in Italian universities [ 20 ]. The questionnaire covered various aspects of the course (e.g., adequacy of preliminary knowledge, balance between the study load and the number of credits assigned to this course, clarity of information on the exam structure) [ 20 ]. As a summary of students’ satisfaction, we considered the following question “ Overall, are you satisfied with the organisation and the teaching of this course ?”. Answers are allowed upon a 5-point Likert scale (“I don’t know” - value 0, “Strongly disagree” - value 1, “Somewhat disagree” - value 2, “Somewhat agree” - value 3 and “Strongly agree” - value 4) [ 20 ].

The assessment of students’ performance occurred in July of each year and was obtained through an oral exam conducted by the same teacher who delivered the lessons for both face-to-face and online courses. While the online group was assessed remotely using a real-time video-chat (Zoom), the face-to-face group conducted the exam in person at the University. The oral exam lasted a maximum of 30 min for each student and comprised open questions and a patient case study aimed at evaluating both the knowledge acquired and the ability to apply it to a clinical scenario [ 21 ]. The final grade was expressed according to the standard national metrics on a scale from 0 to 31, where 0 is the lowest value and 31 is the highest, and the minimum score to pass the course was 18/31 [ 22 ].

Satisfaction and performances shown by the online group were compared with the face-to-face groups from the previous five academic years. All data were obtained from the personal account of the lecturer, rendered available by the University of Verona (Italy) at the end of each academic year with the purpose of continuous improvement of teaching quality. Reports are divided into academic years and include anonymized students’ demographics, degree of attendance, satisfaction questionnaire responses and performances.

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize characteristics and outcomes. To report values of the dependent variables Likert scores, continuous variables were reported as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs, 25th percentile, 75th percentile) and performances of the oral exams as mean with standard deviation (SD) or 95 %Confidence of Interval (CI). For the inferential statistics, the type of teaching (online vs. face-to-face) was considered as the independent variable. Differences in the Likert scores and the performances were explored, using the Wilcoxon rank sum test and the Kruskal Wallis test, respectively. Alpha was set at 0.05. On a preliminarily basis, given that face-to-face group included students from 2014/2015 to 2018/2019 academic years, homoscedasticity of relevant variables under study was assessed and no differences emerged (Levene’s test: Satisfaction, F 1 = 3.60, p = 0.06; Performances, F 1 = 0.41, p = 0.52). R software v3.4.1 was used for statistical analysis, using ggplot2 v3.0.0 for graphs [ 23 , 24 ].

All students of the online group ( n = 46; 100 %) attended the course entirely. Their mean age was 24.6 (SD 2.9) years distributed as 19 females and 27 males.

Participants of the face-to-face group were 112. They all attended the course entirely (100%). Their mean age was 23.6 (SD 1.7) years, distributed as 47 females and 65 males. The graphic representation of participants is reported in the study flowchart (Fig. 2 ).

Study flowchart

Students attending the online course all completed the final online oral exam, with a mean performance of 29 out of 31 (95 % CI 28.2–29.7), with none failing the course. All the students responded to the University quantitative survey about satisfaction, reporting a median Likert score of 4 (Q 1 = 3, Q 3 = 4 [IQR = 1]).

Students attending the course face-to-face all completed the final oral exam, with a mean performance of 27.6 out of 31 (95 % CI 27.1–28.1), with none failing the course. Each of them (100 %) responded to University quantitative survey about satisfaction, reporting a median Likert score of 4 (Q 1 = 3, Q 3 = 4 [IQR = 1]).

There was a significant difference in the mean performances (Wilcoxon rank sum test W = 1665, p < 0.001). No difference was observed between the two groups of students in the perceived satisfaction of the course (Kruskal-Wallis Χ 2 = 3, df = 1, p = 0.08) as reported in Table 1 .

Key results

COVID-19 emergency pushed universities to rethink teaching methodologies, forcing teachers to learn online options to continue education and to ensure adequate educational standards [ 1 ]. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first case-control study aimed at comparing satisfaction and performances of entry-level physiotherapy students experiencing online teaching during COVID-19 pandemic with former face-to-face students of the same Bachelor. According to the main findings, the entry-level students in Physiotherapy showed: (1) no differences in satisfaction whether they attended a face-to-face or an online course; (2) a higher performance in an online course as compared to face-to-face course.

Interpretation

Former systematic reviews, summarizing studies performed before COVID-19 pandemic, found that levels of satisfaction and performances are similar for both distance-online and face-to-face teaching [ 8 , 9 , 10 ]. Our study seems to support these findings, as our online course satisfied students as the face-to-face one. These findings seem to be consistent given that the content of the course, as well as the lecturer and the type of final exam, were homogenous over the years.

The same high satisfaction was expressed by both groups suggesting that students’ needs are evolving. Higher institutions should offer flexibility in the methodologies when these are consistent with the expected learning outcomes allowing students with limited possibility to attend classes (e.g., students working) by continuing their academic career especially in countries where higher education is scarcely widespread [ 25 ]. Even if technological and set up investments for online teaching are required, studies have shown that switching to online teaching can reduce costs for students [ 26 ] which in turn can increase students numbers, especially in those countries where loans for tuitions are a major barrier to university attendance [ 27 , 28 ]. However, building up a digital educational system may increase disparities towards people living in remote and rural regions, poorer social classes, and families experiencing financial difficulties due to COVID-19 induced economic crisis [ 26 , 29 , 30 ].

Moreover, a full eLearning Bachelor’s degree in Physiotherapy have been documented to not fulfil students’ expectations during COVID-19 [ 7 ]. First of all, online resources can act as supplementary material, but not as primary learning activities for acquiring practical skills [ 7 ]. Moreover, online-only learning has been suggested to increase distress and to hinder social interaction with peers and lecturers [ 7 ]. Even if both of these concerns can be easily related to the current uncertainty about the future [ 4 , 6 , 7 ], face-to-face activities have been reported more suitable to favour communication and social support also before the COVID-19 pandemic [ 31 ]. Blended teaching, combining online and face-to-face teaching, have been reported to balance benefits and drawbacks of online and face-to-face teaching [ 7 , 8 ].

Regarding the higher students’ performance, our findings are in line with the growing body of evidence showing that distance-online courses can prepare students as well as face-to-face courses [ 8 , 9 , 10 ].

Although the difference in performance (27.6 in online vs. 29 in face-to-face group) seems to have limited practical meaning, several explanations could justify the higher performance of students in the online group. During the COVID-19 pandemic, other academic activities at universities (e.g., workshops, laboratories, clinical rotations) were suspended to ensure social distancing and physical isolation [ 4 ]. Thus, students could have spent more time studying and delving into the topics of the course. Furthermore, compared to previous years, students benefited from both different teaching strategies (e.g., PowerPoint slides, videos, podcasts, webinars) and the possibility of reviewing the recorded lecturing. This could have better matched the students’ different learning styles [ 32 ], facilitating the acquisition of knowledge for the exam. Finally, it is plausible that the evaluation of students could be less adequate, resulting in an overestimation of the performance. Indeed, an unfamiliar model of assessment (online), as well as the lack of vigilance during the exam performed at home, could lead students to academic misconduct (e.g., cheating, hint) [ 33 ]. Furthermore, the high workload to produce didactic resources, the need to perform concomitant extra academic duties (e.g., clinical service in challenging circumstances), and the difficulty to separate professional and personal activities [ 4 , 5 ], could have impacted the educator and may have in turn influenced the assessment process.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, we analysed one course from a single Italian University, significantly limiting their generalizability. Moreover, the study protocol was not pre-planned but reflected circumstances imposed by the pandemic, that were worldwide unexpected [ 34 ], thus the quality of the study might have been affected. However, we decided to turn our unpreparedness into an opportunity to learn something new about didactic methodologies, and to scrutinise their effect. In this context, we could not have a synchronous control group, as Italian laws did not allow face-to-face teaching for several months [ 3 ]. In fact, one year later the declaration of the state of pandemic, all lessons are still mainly online [ 3 ]. Waiting for face-to-face teaching was not considered a feasible option, as it would have meant an unpredictable delay in students’ graduation. Thus, future studies should investigate the efficacy of online teaching using primary study design (e.g., randomized controlled trial, prospective cohort study) and including also new digital technologies (e.g., augmented and virtual reality) for educational purposes [ 35 , 36 ].

Another limitation was the insufficient lecturer training in online teaching. We quickly adapted the contents of a face-to-face course to online modalities, without specific instructional design based on eLearning. If online courses in physiotherapy education will be implemented in the future, teachers will need specialised support [ 31 ]. On the other hand, teaching provided by the same experienced lecturer improved inter-groups comparability and mitigated discrepancies even if the external validity can be limited.

Online teaching in entry-level Physiotherapy seems to be a feasible option to face COVID-19 pandemic, as satisfies students as well as face-to-face courses and leading to a similar performance. However, further studies should be undertaken to cumulate evidence in the field. Entry-level Bachelors in Physiotherapy may consider moving to eLearning to facilitate access to higher education. Universities will have to train lecturers to help them develop appropriate pedagogical skills, and supply suitable support in terms of economic, organizational, and technological issues, aimed at guaranteeing a high level of education to their students.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable requests.

Abbreviations

Coronavirus disease 2019

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology

European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System

Interquartile range

Standard deviation

95 %Confidence of Interval

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). COVID-19 Response. Education: From disruption to recovery. 2019. Available at: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse . Accessed 28 June 2021.

Remuzzi A, Remuzzi G. COVID-19 and Italy: what next? Lancet . 2020; 395:1225–1228. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30627-9 .

Article Google Scholar

Governo Italiano Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri. Coronavirus, la normative vigente. 2020. Available at: http://www.governo.it/it/coronavirus-normativa . Accessed 28 June 2021.

World Physiotherapy. World Physiotherapy response to COVID-19 - briefing paper 1. Immediate impact on the higher education sector and response to delivering physiotherapist entry level education. 2020. https://world.physio/covid-19-information-hub/covid-19-briefing-papers . Accessed 28 June 2021.

Plummer L, Belgen Kaygısız B, Pessoa Kuehner C, Gore S, Mercuro R, Chatiwala N, Naidoo K. Teaching online during the COVID-19 pandemic: a phenomenological study of physical therapist faculty in Brazil, Cyprus, and The United States. Education Sciences. 2021;11:130. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11030130 .

World Physiotherapy. World Physiotherapy response to COVID-19 - briefing paper 3. Immediate impact on students and the response to delivering physiotherapist entry level education. 2020. https://world.physio/covid-19-information-hub/covid-19-briefing-papers . Accessed 28 June 2021.

Ng L, Seow KC, Mac Donald L, et al. eLearning in physical therapy: lessons learned from transitioning a professional education program to full eLearning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Phys Ther . 2021;101:pzab082. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzab082

Pradeep PG, Papachristou N, Belisario JM, et al. Online eLearning for undergraduates in health professions: a systematic review of the impact on knowledge, skills, attitudes and satisfaction. J Glob Health . 2014;4:010406. doi: https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.04.010406 .

Mącznik AK, Ribeiro DC, Baxter GD. Online technology use in physiotherapy teaching and learning: a systematic review of effectiveness and user’s perceptions. BMC Med Educ . 2015;15:160. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-015-0429-8 .

Ødegaard NB, Myrhaug HT, Dahl-Michelsen T, Røe Y. Digital learning designs in physiotherapy education: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med Educ . 2021;21:48. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02483-w .

Camargo CP, Tempski PZ, Busnardo FF, Martins MA, Gemperli R. Online learning and COVID-19: a meta-synthesis analysis. Clinics (Sao Paulo) . 2020;75:e2286. doi: https://doi.org/10.6061/clinics/2020/e2286 .

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. STROBE initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med . 2007;147:573–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010 .

Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, et al. STROBE Initiative. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med . 2007;4:e297. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0040297 .

Article 29 Data Protection Working Party. Opinion 05/2014 on Anonymisation Techniques. 2014, Apr 10. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/justice/article-29/documentation/opinion-recommendation/files/2014/wp216_en.pdf . Accessed 28 June 2021.

Gazzetta ufficiale dell’Unione europea. L 295/39 Regolamento (UE) 2018/1725 del Parlamento Europeo e del Consiglio. 2018, Nov 18. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/IT/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018R1725 &from=en%20 %C2 %B0. Accessed 28 June 2021.

European Commission. Ethics and Data Protection. 2018, Nov 14. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/data/ref/h2020/grants_manual/hi/ethics/h2020_hi_ethics-data-protection_en.pdf . Accessed 28 June 2021.

European Commission. European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS). 2015. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/education/resources-and-tools/european-credit-transfer-and-accumulation-system-ects_en . Accessed 28 June 2021.

Università di Verona. Panopto: piattaforma di video content management. 2020. Available at: https://www.univr.it/it/panopto . Accessed 28 June 2021.

Gewin V. Five tips for moving teaching online as COVID-19 takes hold. Nature . 2020;580: 295–6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-00896-7 .

Agenzia Nazionale di Valutazione del Sistema Universitario e della Ricerca (ANVUR). Valutazione della didattica e assicurazione della qualità. 2020. Available at: https://www.anvur.it/atti-e-pubblicazioni/lavori-di-ricerca/valutazione-della-didattica-e-assicurazione-della-qualita/ . Accessed 28 June 2021.

Vendrely A. Assessment Methods in Physical Therapy Education: An Overview and Literature Review. J Phys Ther Educ . 2002;16:64–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/00001416-200207000-00010 .

Regolamento didattico di Ateneo. 2020. Available at: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/serie_generale/caricaArticolo?art.progressivo=0&art.idArticolo=1&art.versione=1&art.codiceRedazionale=08A03704&art.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=2008-06-05&art.idGruppo=0&art.idSottoArticolo1=10&art.idSottoArticolo=1&art.flagTipoArticolo=1 . Accessed 28 June 2021.

R Development Core Team: R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2009.

Google Scholar

Wickham H: ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2009 Available at: https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9780387981413 . Accessed 28 June 2021.

Istituto Nazionale di Statistica (ISTAT). Livelli di istruzione e ritorni occupazionali. 2020, Jul 22. Available at: https://www.istat.it/it/files/2020/07/Livelli-di-istruzione-e-ritorni-occupazionali.pdf Accessed 28 June 2021.

World Health Organisation (WHO). ELearning for undergraduate health professional education - a systematic review informing a radical transformation of health workforce development. Published 2015, Jan. Available at: https://www.who.int/hrh/documents/elearning_hwf/en/ . Accessed 28 June 2021.

Ambler SB. The debt burden of entry-level physical therapists. Phys Ther . 2020;100:591–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzz179 .

Jette D. Physical therapist student loan debt. Phys Ther . 2016;96:1685–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20160307 .

Misra V, Chemane N, Maddocks S, Chetty V. Community-based primary healthcare training for physiotherapy: students’ perceptions of a learning platform. S Afr J Physiother . 2019;75:471. doi: https://doi.org/10.4102/sajp.v75i1.471 .

Cleland J, Tan ECP, Tham KY, Low-Beer N. How Covid-19 opened up questions of sociomateriality in healthcare education. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract . 2020;25:479–482. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-020-09968-9 .

Nicklen P, Keating JL, Paynter S, Storr M, Maloney S. Remote-online case-based learning: a comparison of remote-online and face-to-face, case-based learning - a randomized controlled trial. Educ Health. 2016;29:195–202. doi: https://doi.org/10.4103/1357-6283.204213 .

Stander J, Grimmer K, Brink Y. Learning styles of physiotherapists: a systematic scoping review. BMC Med Educ . 2019;19:2. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1434-5 .

Sahu P. Closure of universities due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): impact on education and mental health of students and academic staff. Cureus . 2020;12:e7541. doi: https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.7541 .

Hamam H. COVID-19 surprised us and empowered technology to be its own master. Tapuya: Latin American Science, Technology and Society . 2020;3:272–281. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/25729861.2020.1822072 .

Singh RP, Javaid M, Kataria R, Tyagi M, Haleem A, Suman R. Significant applications of virtual reality for COVID-19 pandemic. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:661–4. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.011 .

Javaid M, Haleem A, Singh RP, Suman R. Dentistry 4.0 technologies applications for dentistry during COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainable Operations and Computers . 2021;2:87–96. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susoc.2021.05.002

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank Miss Angie Rondoni for her valuable advices during the advancement of this manuscript.

Authors’ information (optional) : All the authors have a direct experience of distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic and teaching activity in the healthcare.

The authors declare that they have no funding for this manuscript. Open Access funding provided by Lund University.

Author information

Giacomo Rossettini and Tommaso Geri contributed equally to this work.

Authors and Affiliations

School of Physiotherapy, University of Verona, Verona, Italy

Giacomo Rossettini, Cristina Scumà & Mattia Mirandola

Physiotherapist, Private practitioner, Pistoia, Italy

Tommaso Geri

Laboratory of Rehabilitation Technologies, San Camillo IRCCS srl, Venice, Italy

Andrea Turolla

Department of Neuroscience, Rehabilitation, Ophthalmology, Genetics, Maternal and Child Health, University of Genoa, Campus of Savona, Savona, Italy

Antonello Viceconti & Filippo Maselli

Clinical Epidemiology Unit, Orthopedics, Department of Clinical Sciences Lund, Lund University, Entrégatan 8 Lund 22100, Lund, Sweden

Andrea Dell’Isola

Department of Clinical Sciences Orthopaedics, Clinical Epidemiology Unit, Lund University, Lund, Sweden

Unit of Clinical Epidemiology, IRCCS Istituto Ortopedico Galeazzi, Milan, Italy

Silvia Gianola

Sovrintendenza Sanitaria Regionale Puglia, Direzione Regionale Puglia INAIL, Bari, Italy

Filippo Maselli

Department of Medical and Biological Sciences, University of Udine, Udine, Italy

Alvisa Palese

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors conceived, designed, drafted and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Andrea Dell’Isola .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

We conducted this study in compliance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was assumed when respondents completed and submitted the survey after reading the purpose statement of the study, strategies to ensure confidentiality and privacy of the data collected. Data were fully and irreversibly anonymized by generalization of important variables. Ethics approval during this pandemic was not required according to the “Ethics and data protection” regulations of the European advisory body and European Commission.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Rossettini, G., Geri, T., Turolla, A. et al. Online teaching in physiotherapy education during COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: a retrospective case-control study on students’ satisfaction and performance. BMC Med Educ 21 , 456 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02896-1

Download citation

Received : 28 June 2021

Accepted : 17 August 2021

Published : 30 August 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02896-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Physiotherapy

- Entry-level

- SARS-CoV-2.

BMC Medical Education

ISSN: 1472-6920

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Research Reviews

- Masterclass

A Guide to Study Designs in Physiotherapy Research

Physiotherapists rely on research to inform their own practice in evidence-based medicine (1). Evidence-based medicine is defined as the combination of research, clinical expertise, and patient values to guide decision-making in the care of patients.

In order to practice the research component of evidence-based medicine, physiotherapists must stay up-to-date on the vast body of scientific literature. They must also understand the hierarchy of study designs and how they are represented in physiotherapy research.

Here we will break down the different study designs you will find in physiotherapy research. For each study design, we will discuss scenarios in which they are used, as well as provide examples in physiotherapy research.

Randomized Controlled Trials

Randomized controlled trials are the highest level of research design, often considered the “gold standard” for determining effectiveness of a new treatment (2). They are prospective, meaning they are planned before any data collection occurs. They involve the random assignment of participants into an experimental or a control group.

Specific to physiotherapy research, the control group will often receive some kind of therapy, instead of no therapy like a true control group. For example, here is a randomized controlled trial that compared supervised resistance training to home-based resistance training (rather than no training) for patients with subacromial shoulder pain.

Randomization creates an equal opportunity for participants to be in either group. This reduces bias by balancing participant characteristics between the groups. Oftentimes, participants don’t know to which group they are assigned (also known as “blinding”).

Randomized controlled trials are the best way to determine causation (i.e. outcomes due to the intervention rather than other factors).

Cohort Studies

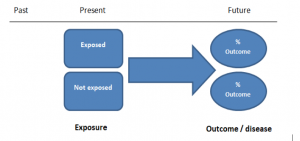

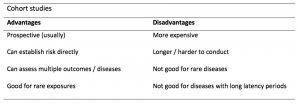

Cohort studies follow participants who share a common characteristic. They are longitudinal, meaning researchers observe participants for a certain period of time. They can be prospective (following participants forward in time) or retrospective (following participants back in time).

Cohort studies are best for determining the external factors that influence health. They also help determine risk factors for injuries or conditions.

In physiotherapy, researchers could use a cohort study to follow patients who have undergone physiotherapy treatment for a specific condition. All participants received the treatment and were not randomly assigned like in a randomized controlled trial. Researchers determine if factors (such as age, injury severity, compliance to therapy, etc.) affect outcomes of the treatment. This research review by Dr Mariana Wingwood provides an example of a retrospective cohort study that evaluated early rehab on function in patients with vertebral compression fractures.

Prospective cohort studies are a strong study design and quite common in physiotherapy research. Another review by Stacey Harden is an example of a prospective cohort study that followed professional football (soccer) players to evaluate risk factors for hip and groin pain which you can find here .

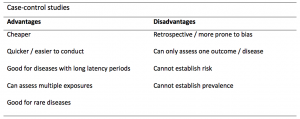

Case-Control Studies

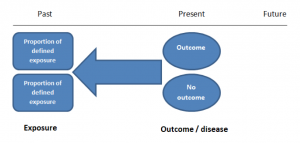

Case-control studies are studies that look back in time to compare patients who have an injury/condition (cases) to patients who do not have injury/condition (controls). The controls are usually matched to the cases on several demographic variables, such as age, sex, and physical activity status.

Case-control studies are helpful in determining risk factors for injuries or conditions. Many researchers will conduct them as an initial study to learn more about an injury/condition prior to conducting a prospective trial.

Case-control studies are common in physiotherapy, such as this research review by Dr Melinda Smith on the investigation of risk factors in runners with medial tibial stress syndrome compared to matched asymptomatic runners.

Cross-Sectional Studies

Cross-sectional studies are observational studies that evaluate data from participants at a single time point. They are used to determine associations between two variables. For example, this research review by Steve Kamper used a cross-sectional design to determine if posture and smartphone use were related to neck pain in young adults.

Physiotherapy researchers use cross-sectional studies for survey-based research, as well as clinical-based studies. Cross-sectional studies are usually more time and cost effective, and are therefore more appealing and tangible in physiotherapy clinical settings.

Case Series and Case Studies

The last and weakest study designs are case series (~<10 people in a study) and case studies (1 person in a study). They are considered the weakest of study designs because due to the small sample size, they are less likely to be generalizable to the population of interest.

However, case series/studies can be extremely informative to physiotherapy practice, as they usually describe rare or unusual injuries or conditions. They provide a glimpse into the clinical practice of another therapist and healthcare team, which can help inform your own practice. An example you can find here was reviewed by Robin Kerr in a case series of 5 patients who underwent an alternative treatment approach for frozen shoulder.

Wrapping Up

In practicing evidence-based medicine, it is important to be familiar with the different study designs that can be found in physiotherapy research. Understanding the indications for each study design will aid physiotherapists in determining if the study should affect or change their clinical practice.

Keep in mind that each type of study has its advantages and disadvantages. Although they are ordered in a hierarchy of strongest (i.e., randomized controlled trials) to weakest (i.e., case studies) design, we have covered some considerations specific to physiotherapy research that make certain designs more common and efficient than others.

📚 Stay on the cutting edge of physio research!

📆 Every month our team of experts break down clinically relevant research into five-minute summaries that you can immediately apply in the clinic.

🙏🏻 Try our Research Reviews for free now for 7 days!

- Manchikanti L, Boswell MV, Giordano J. Evidence-based interventional pain management: principles, problems, potential and applications. Pain Physician. 2007 Mar;10(2):329-56. PMID: 17387356.

- Hariton E, Locascio JJ. Randomised controlled trials – the gold standard for effectiveness research: Study design: randomised controlled trials. BJOG. 2018;125(13):1716. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.15199.

Don’t forget to share this blog!

Leave a comment.

If you have a question, suggestion or a link to some related research, share below!

You must be logged in to post or like a comment.

Related blogs

Elevate your physio knowledge every month.

Get free blogs, infographics, research reviews, podcasts & more.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Online teaching in physiotherapy education during COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: a retrospective case-control study on students’ satisfaction and performance

2021, BMC Medical Education

Background During COVID-19 pandemic, physiotherapy lecturers faced the challenge of rapidly shifting from face-to-face to online education. This retrospective case-control study aims to compare students’ satisfaction and performances shown in an online course to a control group of students who underwent the same course delivered face-to-face in the previous five years. Methods Between March and April 2020, a class (n = 46) of entry-level physiotherapy students (University of Verona - Italy), trained by an experienced physiotherapist, had 24-hours online lessons. Students exposed to the same course in the previous five academic years (n = 112), delivered with face-to-face conventional lessons, served as a historical control. The course was organized in 3 sequential phases: (1) PowerPoint presentations were uploaded to the University online platform, (2) asynchronous video recorded lectures were provided on the same platform, and (3) between online lectures, the lecturer and students ...

RELATED PAPERS

South African Journal of Physiotherapy

Michael Rowe , Vivienne Bozalek , Jose Frantz

Proceedings of INTED2021 Conference

Roberta Matkovic

IRJET Journal

Revista Española de Educación Médica

Javier Jesús Joya Jiménez

https://ijshr.com/IJSHR_Vol.7_Issue.1_Jan2022/IJSHR-Abstract.03.html

International Journal of Science and Healthcare Research (IJSHR)

Pakistan Journal of Medical and Health Sciences

Interdisciplinary Journal of Virtual Learning in Medical Sciences (IJVLMS) , Dr Pinki Rai , Poulomi Chatterji , Vipin Narwal

Albert Balaguer

Australian Journal of Clinical Education

Irmina nahon

Journal of Education and e-Learning Research

Education Sciences

Online Learning

Dr. Orchida Fayez

Zenodo (CERN European Organization for Nuclear Research)

Prof.Dr.SoHayla Attalla

IOSR Journals

Naga Sri Latha Bathala

Afif Faishal Najib

Concurrent Disorders Society Inc.

Studia Universitatis Babeș-Bolyai Negotia

Elisabeta Butoi

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Europe PMC requires Javascript to function effectively.

Either your web browser doesn't support Javascript or it is currently turned off. In the latter case, please turn on Javascript support in your web browser and reload this page.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Sports Phys Ther

- v.7(5); 2012 Oct

RESEARCH DESIGNS IN SPORTS PHYSICAL THERAPY

1 Baton Rouge, Louisiana, USA [email protected]

Research is designed to answer a question or to describe a phenomenon in a scientific process. Sports physical therapists must understand the different research methods, types, and designs in order to implement evidence‐based practice. The purpose of this article is to describe the most common research designs used in sports physical therapy research and practice. Both experimental and non‐experimental methods will be discussed.

INTRODUCTION

Evidence‐based practice requires that physical therapists are able to analyze and interpret scientific research. When performing or evaluating research for clinical practice, sports physical therapists must first be able to identify the appropriate study design. Research begins by identifying a specific aim or purpose; researchers should always attempt to use a methodologically superior design when performing a study. Research design is one of the most important factors to understand because:

- 1. Research design provides validity to the study;

- 2. The design must be appropriate to answer the research question; and

- 3. The design provides a “level of evidence” used in making clinical decisions.

Research study designs must have appropriate validity, both internally and externally. Internal validity refers to the design itself, while external validity refers to the study's applicability in the real world. While a study may have internal validity, it may not have external validity; however, a study without internal validity is not useful at all.

Most clinical research suffers from a conflict between internal and external validity. Internally valid studies are well‐controlled with appropriate designs to ensure that changes in the dependent variable result from manipulation of an independent variable. Well‐designed research provides controls for managing or addressing extraneous variables that may influence changes in the dependent variable. This is often accomplished by ensuring a homogenous population; however, clinical populations are rarely homogenous. An internally‐valid study with control of extraneous variables may not represent a more heterogeneous clinical population; therefore, clinicians should always consider the conflict between internal and external validity both when choosing a research design and when applying the results of research on order to make evidence‐based clinical decisions.

Furthermore, research can be basic or applied. Basic science research is often done on animals or in a controlled laboratory setting using tissue samples, for example. Applied research involves humans, including patient populations; therefore, applied research provides more clinical relevance and clinical application (i.e., external validity) than basic science research.

One of the most important considerations in research design for internal validity is to minimize bias. Bias represents the intentional or unintentional favoring of something in the research process. Within research designs, there are 5 important features to consider in establishing the validity of a study: sample, perspective, randomization, control, and blinding.

- Sample size and representation is very important for both internal and external validity. Sample size is important for statistical power, but also increases the representativeness of the target population. Unfortunately, some studies use a ‘convenience sample’, often consisting of college students, which may not represent a typical clinical population. Obviously, a representative clinical population can provide a higher level of external validity than a convenience sample.

- In terms of perspective, a study can be prospective (before the fact) or retrospective (after the fact). A prospective study has more validity because of more control of the variables at the beginning of and throughout the study, whereas a retrospective study has less control since it is performed after the end of an event. A prospective design provides a higher level of evidence to support cause‐and‐effect relationships, while retrospective studies are often associated with confounding variables and bias.

- Random assignment to an experimental or control group is performed to represent a ‘normal distribution’ of the population. Randomization reduces selection bias to ensure one group doesn't have an advantage over the other. Sometimes groups, rather than individual subjects, are randomly assigned to an experimental or control group; this is referred to as “block randomization.” Sample bias can also occur when a “convenience sample” is used that might not be representative of the target population. This is often seen when healthy, college‐aged students are included, rather than a representative sample of the population.

- A control group helps ensure that changes in the dependent variable are due to changes in the independent variable, and not due to chance. A control group receives no intervention, while the experimental group receives some type of intervention. In some situations, a true control group is not possible or ethical; therefore, “quasi‐experimental” designs are often used in clinical research where the control group receives a “standard treatment.” Sometimes, the experimental group can be used as it's “own control” by testing different conditions over time.

- Blinding (also known as “masking”) is performed to minimize bias. Ideally, both the subjects and the investigator should be blinded to group assignment and intervention. For example, a “double‐blind” study is one in which the subjects are not aware if they are receiving the experimental intervention or a placebo and at the same time, and the examiner is not aware which intervention the subjects received.

While considering these 5 features, a large sample size of patients, prospective, randomized, controlled, double‐blinded clinical outcome study would likely provide the best design to assure very high internal and external validity.

Most research follows the “scientific method”. The scientific method progresses through four steps:

- 1. Identification of the question or problem;

- 2. Formulation of a hypothesis (or hypotheses);

- 3. Collection of data; and

- 4. Analysis and interpretation of data.

Different research designs applying apply are used to answer a question or address a problem. Different authors provide different classifications of research designs. 1 ‐ 4

Within the scientific method, there are 2 main classifications of research methodology: experimental and non‐experimental. Both employ systematic collection of data. Experimental research is used to determine cause‐and‐effect relationships, while non‐experimental is used to describe observations or relationships in a systematic manner. Both experimental and non‐experimental research consist of several types and designs. ( Table 1 )

Research Designs.

| Method | Experimental | Non-Experimental | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | True | Quasi | Descriptive | Exploratory | Analytical |

| Design | Pre-post test control group | One group pre-post test | Survey | Cohort | Systematic Review |

| Post- test only control group | One-way repeated measures | Normative | Case Control | Meta-Analysis | |

| Multi-factorial | Two-group pre-post test | Observational | Epidemiological | ||

| Mixed Design | Two-way repeated measures | Developmental | Correlational | ||

| Non-equivalent pre-post test control | Case | Methodological | |||

| Historical control | Qualitative | ||||

| Cross-over design | |||||

| Time-series design | |||||

| Single subject designs | |||||

Experimental Methods

Experimental methods follow the scientific method in order to examine changes in one variable by manipulating other variables to attempt to establish cause‐and‐effect. The dependent variable is measured under controlled conditions while controlling for confounding variables. It is important to remember that statistics do not establish cause‐and‐effect; rather, the design of the study does. Experimental statistics can only reject a null hypothesis and identify variance accounted for by the independent variable. Thomas et al. 4 provide three criteria to establish cause‐and‐effect:

- 1. Cause must precede effect in time;

- 2. Cause and effect must be correlated with each other; and

- 3. Relationship cannot be explained by another variable.

There are 3 elements of research to consider when evaluating experimental designs: groups, measures, and factors. Subjects in experimental research are generally classified into groups such as an experimental (those receiving treatment) or control group. Technically speaking, however, “groups” refers to the treatment of the data, not how the treatment is administered 2 . Groups are sometimes called “treatment arms” in order to denote subjects receiving different treatments. True experimental designs generally use randomized assignment to groups, while quasi‐experimental research may not.

Next, the order of measurements and treatments should be considered. “Time” refers to the course of the study from start to finish. Observations, or measurements of the dependent variables, can be performed one or several times throughout a study. The term, “repeated measures” denotes any measurement that is repeated on a group of subjects in the study. Repeated measures are often used in pseudo‐experimental research when the subjects act as their own control in one group, while true experimental research can use repeated measurements of the dependent variable as a single factor (“time”).

Since experimental designs are used to identify changes in a dependent variable by manipulating an independent variable, “factors” are used. Factors are essentially the independent variables. Individual factors can also have several levels. Single‐factor designs are referred to as “one‐way” designs with one independent variable and any number of levels. One‐way designs may have multiple dependent variables (measurements), but only one independent variable (treatment). Studies involving more than one independent variable are considered “multi‐factorial” and are referred to as “two‐way” or “three‐way” (and so on) designs. Multi‐factorial designs are used to investigate interactions within and between different variables. A “mixed design” factorial study includes 2 more independent variables with one repeated across all subjects and the other randomized to independent groups. Figure 1 is an example of a 2‐way repeated measures design including a true control group.

Two‐way repeated measures experimental design to determine interactions within and between groups.

Factorial designs are denoted with numbers representing the number of levels of each factor. A two‐way factorial (2 independent variables) with 2 levels of each factor is designated by “2 × 2”. The total number of groups in a factorial design can be determined by multiplying the factors together; for example, a 2×2 factorial has 4 groups while a 2×3×2 factorial has 12. Table 2 describes the differences in factorial designs using an example of 3 studies examining strength gains of the biceps during exercise. Each factor has multiple levels. In the 1‐way study, strength of the biceps is examined after performing flexion or extension with standard isotonic resistance. In the 2‐way study, a 3‐level factor is added by comparing different types of resistance during the same movements. In the 3‐way study, 2 different intensity levels are added to the design.

Examples of progressive factorial designs.

| 1-way | Factor A (2 levels): Exercise Movement (Flexion and Extension) |

| 2-way (2 × 3) | Factor A (2 levels): Exercise Movement (Flexion and Extension) |

| Factor B (3 levels): Resistance Type (Isotonic, Isokinetic, Elastic) | |

| 3-way (2 × 3 × 2) | Factor A (2 levels): Exercise Movement (Flexion and Extension) |

| Factor B: (3 levels) Resistance Type (Isotonic, Isokinetic, Elastic) | |

| Factor C: (2 levels) Intensity (High and Low) |

Statistical analysis of a factorial design begins by determining a main effect, which is an overall effect of a single independent variable on dependent variables. If a main effect is found, post‐hoc analysis examines the interaction between independent variables (factors) to identify the variance in the dependent variable.

As described in Table 1 previously, there are 2 types of experimental designs: true experimental and quasi‐experimental.

True Experimental Designs

True experimental designs are used to determine cause‐and‐effect by manipulating an independent variable and measuring its effect on a dependent variable. These designs always have at least 2 groups for comparison.

In a true experimental design, subjects are randomized into at least 2 independent, separate groups, including an experimental and “true” control. This provides the strongest internal validity to establish a cause‐and‐effect relationship within a population. A true control group consists of subjects that receive no treatment while the experimental group receives treatment. The randomized, controlled trial design is the “gold standard” in experimental designs, but may not be the best choice for every project.

Table 3 provides common true experimental designs that include 2 independent, randomly assigned groups and a true control group. Notation is often used to illustrate research designs:

Common true experimental designs.

| True Experimental Design | Brief Description | Notation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-posttest control group (one-way factorial) | Experimental and control groups with pre- and post test; only experimental group receives treatment | : – – |

| : – – | ||

| Post-test only control group | Same as above, but no pre-test | : – |

| : – | ||

| Multi-factorial (2-way, 3-way, etc) | multiple experimental groups with one true control group | : – – |

| : – – | ||

| : – – | ||

| : – – | ||

| Mixed Design | 1 experimental and 1 true control group with repeated measures | : – – – |

| : – – – |

n = subjects in a group (n 1 refers to experimental group while n 0 refers to control group)

T = treatment (T 1 . refers to sequential treatments)

0 = observation (O 0 refers to baseline, O 1 refers to sequential observations)

Quasi‐Experimental Designs

Clinical researchers often find it difficult to use true experimental designs with a ‘true’ control because it may be unethical and sometimes illegal to withhold treatment within a patient population. In addition, clinical trials are often affected by a conflict between internal and external validity. Internal validity requires rigorous control of variables; however, that control does not support real‐world generalizability (external validity). As previously described, clinical researchers must seek balance between internal and external validity.

Quasi‐experimental designs are those that do not include a true control group or randomization of subjects. While these types of designs may reduce the internal validity of a study, they are often used to maximize a study's external validity. Quasi‐experimental designs are used when true randomization or a true control group is unethical or difficult. For example, a ‘pseudo‐control’ group may include a group of patients receiving traditional treatment rather than a true control group receiving nothing.

Block‐randomization or cluster grouping may also be more practical when examining groups, rather than individual randomization. Subjects are grouped by similar variables (age, gender, etc) to help control for extraneous factors that may influence differences between groups. The block factor must be related to dependent variable (i.e., the factor affecting response to treatment).

A cross‐over or counterbalanced design may also be used in a quasi‐experimental study. This design is often used when only 2 levels of an independent variable are repeated to control for order effects. 3 A cross‐over study may require twice as long since both groups must undergo the intervention at different times. During the cross‐over, both groups usually go through a ‘washout’ period of no intervention to be sure prolonged effects are not a factor in the outcome.

Examples of quasi‐experimental designs can include both single and multiple groups ( Table 4 ). Quasi‐experimental designs generally do not randomize group assignment or use true control groups. (Note: One‐group pre‐post test designs are sometimes classified as “pre‐experimental” designs.)

Quasi-Experimental designs.

| Quasi Experimental Design | Brief Description | Notation Example |

|---|---|---|

| One group pre-post test | 1 group evaluated before and after intervention | : – – |

| One–way repeated measures | 1 group evaluated multiple times (with or without baseline) | : – – – – |

| Two–group pre–post test (no true control) | 2 groups evaluated before and after intervention with pseudo–control or no control | : – – |

| : – – | ||

| Two–way repeated measures (2×3) | 2 groups, multiple observations, no true control | : – – – |

| : – – – | ||

| Non–equivalent pre–post test control | 2 groups not randomized; often healthy versus patient groups | : – – |

| : – – | ||

| Historical control | Control group was evaluated earlier as part of a previous study | : – – |

| : | ||

| Cross–over design | 2 groups switch intervention after wash–out period (X) | : – – – X – |

| : – – X – – | ||

| (X denotes the washout) | ||

| Time–series design | Multiple measures before and after treatment, usually used for behavioral or community interventions | : – – – |

| : – – – – |

T = treatment (T 1 refers to sequential treatments)

O = observation (O 0 refers to baseline, O 1 refers to sequential observations

Single‐subject designs are also considered quasi‐experimental as they draw conclusions about the effects of a treatment based on responses of single patients under controlled conditions. 3 These designs are used when withholding treatment is considered unethical or when random assignment is not possible or when it is difficult to recruit subjects as is commonly seen in rare diseases or conditions. Single subject designs have 2 essential elements: design phases and repeated measures. 3 Design phases include baseline and intervention phases. The baseline measure serves as a ‘pseudo‐control.” Repeated measurement over time (for example, during each treatment session) can occur during the baseline and intervention phases. Common single‐subject designs are commonly denoted by the letters ‘A’ ‘(baseline phases) and ‘B’ (intervention phases): A‐B; A‐B‐A; and A‐B‐A‐B. Other single‐subject designs include withdrawal, multiple baselines, alternating treatment, multiple treatment, and interactive design. For more detailed descriptions on single subject designs, see Portney and Watkins. 3

Non‐Experimental Methods

Studies involving non‐experimental methods include descriptive, exploratory, and analytic designs. These designs do not infer cause‐and‐effect by manipulating variables; rather, they are designed to describe or explain phenomena. Non‐experimental designs help provide an early understanding about clinical conditions or situations, without a full clinical study through systematic collection of data.

Descriptive Designs

Descriptive designs are used to describe populations or phenomena, and can help identify groups and variables for new research questions. 3 Descriptive designs can be prospective or retrospective, and may use longitudinal or cross‐sectional methods. Phenomena can be evaluated in subjects either over a period time (longitudinal studies) or through sampling different age‐grouped subjects (cross‐sectional studies). Descriptive research designs are used to describe results of surveys, provide norms or descriptions of populations, and to describe cases. Descriptive designs generally focus on describing one group of subjects, rather than comparing different groups.

Surveys are one of the most common descriptive designs. 4 They can be in the form of questionnaires or interviews. The most important component of an effective survey is to have an appropriate sample that is representative of the population of interest. There are generally 2 types of survey questions: open‐ended and closed‐ended. Open‐ended questions have no fixed answer, while closed‐ended questions have definitive answers including rank, scale, or category. Investigators should be careful not to lead answers of subjects one way or another, and to keep true to the objectives of the study. Surveys are limited by the sample and the questions asked. External validity is threatened, for example, if the sample was not representative of the research question and design.

A special type of survey is the Delphi technique that uses expert opinions to make decisions about practices, needs, and goals. 4 The Delphi technique uses a series of questionnaires in successive stages called “rounds.” The first round of the survey focuses on opinions of the respondents, and the second round of questions is based on the results of the first round, where respondents are asked to reconsider their answers in context of other's responses. Delphi surveys are common in establishing expert guidelines where consensus around an issue is needed.

Observational

A descriptive observational study evaluates specific behaviors or variables in a specific group of subjects. The frequency and duration of the observations are noted by the researcher. An investigator observing a classroom for specific behaviors from students or teachers would use an observational design.

Normative research describes typical or standard values of characteristics within a specific population. 3 These “norms” are usually determined by averaging the values of large samples and providing an acceptable range of values. For example, goniometric measures of joint range of motion are reported with an accepted range of degrees, which may be recorded as “within normal limits.” Samples for normative studies must be large, random, and representative of the population heterogeneity. 3 The larger the target population, the larger sample required to establish norms; however, sample sizes of at least 100 are often used in normative research. Normative data is extremely useful in clinical practice because it serves as a basis for determining the need for an intervention, as well as an expected outcome or goal.

Developmental

Developmental research helps describe the developmental change and the sequencing of human behavior over time. 3 This type of research is particularly useful in describing the natural course of human development. For example, understanding the normal developmental sequencing of motor skills can be useful in both the evaluation and treatment of young athletes. Developmental designs are classified by the method used to collect data; they can be either cross‐sectional or longitudinal.

Case Designs

Case designs offer thoughtful descriptions and analysis of clinical information; 2 they include case reports, case studies, and case series. A case report is an in‐depth understanding of a unique patient, while a case study focuses on a unique situation. These cases may involve a series of patients or situations, which is referred to as a ‘case series’ design. Case designs are often useful in developing new hypotheses and contributing to theory and practice. They also provide a springboard for moving toward more quasi‐experimental or experimental designs in order to investigate cause and effect.

Qualitative

Research measures can also be classified as quantitative or quantitative. Quantitative measures explain differences, determines causal relationships, or describes relationships; these designs include those previously discussed. Qualitative research, on the other hand, emphasizes attempting to discern process and meaning without measuring quantity. Qualitative studies focus on analysis in trying to describe a phenomenon. Qualitative research examines beliefs, understanding, and attitudes through skillful interview and content analysis. 5 These designs are used to describe specific situations, cultures, or everyday activities. Table 5 provides a comparison between qualitative and quantitative designs.

Comparison of quantitative and qualitative designs (Adapted from Thomas et al4 and Carter et al 2 ).

| Research Component | Qualitative | Quantitative |

|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis | Inductive, grounded | Deductive, set a-priori |

| Sample | Purposeful, small | Random, large groups |

| Setting | Natural, real-world | Laboratory |

| Data gathering | Researcher is primary instrument; relies on language & words for data | Objective instrumentation; relies on numerical data |

| Design | Flexible; may change | Determined in advance |

| Data analysis | Descriptive interpretation | Statistical methods |

| Variable manipulation | Absent | Present |

Exploratory Designs

Exploratory designs establish relationships without manipulating variables while using non‐experimental methods. These designs include cohort studies, case control studies, epidemiological research, correlational studies, and methodological research. Exploratory research usually involves comparison of 2 or more groups.

Cohort Studies

A cohort is a group of subjects being studied. Cohort studies may evaluate single groups or differences between specific groups. These observations may be made in subjects one time, or over periods of time, using either cross‐sectional or longitudinal methods.

In contrast to experimental designs, non‐experimentally designed cohort studies do not manipulate the independent variable, and lack randomization and blinding. A prospective analysis of differences in cohort groups is similar to an experimental design, but the independent variable is not manipulated. For example, outcomes after 2 different surgeries in 2 different groups can be followed without randomization of subjects using a prospective cohort design.

Some authors 2 have classified “Outcomes Research” as a retrospective, non‐experimental cohort design, where differences in groups are evaluated ‘after the fact’ without random allocation to groups or manipulation of an independent variable. This design would include chart reviews examining outcomes of specific interventions.

Case Control Studies

Case control studies are similar to cohort studies comparing groups of subjects with a particular condition to a group without the condition. Both groups are observed over the same period of time, therefore requiring a shorter timeframe compared to cohort studies. Case control studies are better for investigations of rare disease or conditions because the sample size required is less than a cohort study. The control group (injury/disease‐free) is generally matched to the injury/disease group by confounding variables consistent in both groups such as age, gender, and ethnicity.

Case control studies sometimes use “odds ratios” in order to estimate the relative risk if a cohort study would have been done. 4 An odds ratio greater than 1 suggests an increased risk, while a ratio less than 1 suggests reduced risk.

Epidemiological Research

Studies that evaluate the exposure, incidence rates, and risk factors for disease, injury, or mortality are descriptive studies of epidemiology. According to Thomas et al, 4 epidemiological studies evaluate “naturally occurring differences in a population.” Epidemiological studies are used to identify a variety of measures in populations ( Table 6 ).

Measurement terminology used in epidemiological research.

| Ratio | Incidence in group A / Incidence in group B |

| Proportion | Incidence in group A / (Incidence in group A + Incidence in group B) |

| Rate | Incidence over time, usually multiplied by a constant (per 1000) |

| Prevalence | Incidence in group / Total Population (at one point in time) |

| Incidence | Number of new cases over a specified length of time |

| Distribution | Frequency or incidence and pattern in a population |

| Determinants | Characteristic factors related to the disease or injury (Including risk factors) |

| Relative Risk | Likelihood of injury or disease in those exposed compared to non-exposed |

| Odds ratio | Odds of developing an injury or condition |

“Relative risk,” (RR) which is associated with exposure and incidence rates. Portney and Watkins 3 use a “contingency table” ( Table 7 ) to determine the relative risk and odds ratio. Usually, incidence rates are compared between 2 groups by dividing the incidence of one group by the other.

Contingency Table to determine risk (Adapted from Portney and Watkins 3 ).

| Injured | |||

| Exposed | Yes | No | |

| Yes | A | b | |

| No | C | d | |

Using Table 7 ,

With these formulas, the “null value” is 1.0. A risk or odds ratio less than 1.0 suggests reduced risk or odds, while a value greater than 1.0 suggests increased risk or odds. For example, if the risk is 1.5 in a group, there is a 1.5 times greater risk of suffering an injury in that group. Relative risk should be reported with a confidence interval, typically 95%.

Epidemiological studies can also be used to test a hypothesis of the effectiveness of an intervention on on injury prevention by using incidence as a dependent variable. These studies help link exposures and outcomes with observations, and can include case control and cohort studies mentioned previously.

Correlational Studies

Correlations studies examine relationships among variables. Correlations are expressed using the Pearson's “r” value that can range from −1 to +1. A Pearson's “r” value of +1 indicates a perfect linear correlation, noting the increase in one variable is directly dependent on the other. In contrast, an “r” value of −1 indicates a perfect inverse relationship. An “r” value of 0 indicates that the variables are independent of each other. The most important thing to remember is that correlation does not infer causation; in other words, correlational studies can't be used to establish cause‐and‐effect. In addition, 2 variables may have a high correlation (r>.80), but lack statistical significance if the p‐value is not sufficient. Finally, be aware that correlational studies must have a representative sample in order to establish external validity.

Methodological

The usefulness of clinical research and decision‐making heavily depends on the validity and reliability of measurements. 3 Methodological research is used to develop and test measuring instruments and methods used in practice and research. Methodological studies are important because they provide the reliability and validity of other studies. First, the reliability of the rater (inter‐rater and intra‐rater reliability) must be established when administering a test in order to support the accuracy of measurements. Inter‐rater reliability supports consistent measurements between different raters, while intra‐rater reliability supports consistent measures for the same individual rater. Reliability can also be established for instruments by demonstrating consistent measurements over time. Reliability is related to the ability to control error, and thus associated with internal validity.

Methodological studies are also used to establish validity for a measurement, which may include clinical diagnostic tests, performance batteries, or measurement devices. Measurement validity establishes the extent to which an instrument measures what it intends to measure. Different types of validity can be measured, including face validity, content validity, criterion‐related validity and construct validity ( Table 8 ).

Different types of validity in scientifi c research.

| Face Validity | Measurement appears to measure what it is supposed to |

| Content Validity | Items making up a measurement are representative and consistent with intended use |

| Criterion-related Validity | Measurements can predict results of another ‘gold standard' test (may be concurrent or predictive) |

| Construct Validity | Ability of a measurement to measure an abstract concept (ie, construct) |