- Case report

- Open access

- Published: 13 September 2021

Critical iron deficiency anemia with record low hemoglobin: a case report

- Audrey L. Chai ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5009-0468 1 ,

- Owen Y. Huang 1 ,

- Rastko Rakočević 2 &

- Peter Chung 2

Journal of Medical Case Reports volume 15 , Article number: 472 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

31k Accesses

8 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

Anemia is a serious global health problem that affects individuals of all ages but particularly women of reproductive age. Iron deficiency anemia is one of the most common causes of anemia seen in women, with menstruation being one of the leading causes. Excessive, prolonged, and irregular uterine bleeding, also known as menometrorrhagia, can lead to severe anemia. In this case report, we present a case of a premenopausal woman with menometrorrhagia leading to severe iron deficiency anemia with record low hemoglobin.

Case presentation

A 42-year-old Hispanic woman with no known past medical history presented with a chief complaint of increasing fatigue and dizziness for 2 weeks. Initial vitals revealed temperature of 36.1 °C, blood pressure 107/47 mmHg, heart rate 87 beats/minute, respiratory rate 17 breaths/minute, and oxygen saturation 100% on room air. She was fully alert and oriented without any neurological deficits. Physical examination was otherwise notable for findings typical of anemia, including: marked pallor with pale mucous membranes and conjunctiva, a systolic flow murmur, and koilonychia of her fingernails. Her initial laboratory results showed a critically low hemoglobin of 1.4 g/dL and severe iron deficiency. After further diagnostic workup, her profound anemia was likely attributed to a long history of menometrorrhagia, and her remarkably stable presentation was due to impressive, years-long compensation. Over the course of her hospital stay, she received blood transfusions and intravenous iron repletion. Her symptoms of fatigue and dizziness resolved by the end of her hospital course, and she returned to her baseline ambulatory and activity level upon discharge.

Conclusions

Critically low hemoglobin levels are typically associated with significant symptoms, physical examination findings, and hemodynamic instability. To our knowledge, this is the lowest recorded hemoglobin in a hemodynamically stable patient not requiring cardiac or supplemental oxygen support.

Peer Review reports

Anemia and menometrorrhagia are common and co-occurring conditions in women of premenopausal age [ 1 , 2 ]. Analysis of the global anemia burden from 1990 to 2010 revealed that the prevalence of iron deficiency anemia, although declining every year, remained significantly high, affecting almost one in every five women [ 1 ]. Menstruation is considered largely responsible for the depletion of body iron stores in premenopausal women, and it has been estimated that the proportion of menstruating women in the USA who have minimal-to-absent iron reserves ranges from 20% to 65% [ 3 ]. Studies have quantified that a premenopausal woman’s iron storage levels could be approximately two to three times lower than those in a woman 10 years post-menopause [ 4 ]. Excessive and prolonged uterine bleeding that occurs at irregular and frequent intervals (menometrorrhagia) can be seen in almost a quarter of women who are 40–50 years old [ 2 ]. Women with menometrorrhagia usually bleed more than 80 mL, or 3 ounces, during a menstrual cycle and are therefore at greater risk for developing iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia. Here, we report an unusual case of a 42-year-old woman with a long history of menometrorrhagia who presented with severe anemia and was found to have a record low hemoglobin level.

A 42-year-old Hispanic woman with no known past medical history presented to our emergency department with the chief complaint of increasing fatigue and dizziness for 2 weeks and mechanical fall at home on day of presentation.

On physical examination, she was afebrile (36.1 °C), blood pressure was 107/47 mmHg with a mean arterial pressure of 69 mmHg, heart rate was 87 beats per minute (bpm), respiratory rate was 17 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation was 100% on room air. Her height was 143 cm and weight was 45 kg (body mass index 22). She was fully alert and oriented to person, place, time, and situation without any neurological deficits and was speaking in clear, full sentences. She had marked pallor with pale mucous membranes and conjunctiva. She had no palpable lymphadenopathy. She was breathing comfortably on room air and displayed no signs of shortness of breath. Her cardiac examination was notable for a grade 2 systolic flow murmur. Her abdominal examination was unremarkable without palpable masses. On musculoskeletal examination, her extremities were thin, and her fingernails demonstrated koilonychia (Fig. 1 ). She had full strength in lower and upper extremities bilaterally, even though she required assistance with ambulation secondary to weakness and used a wheelchair for mobility for 2 weeks prior to admission. She declined a pelvic examination. No bleeding was noted in any part of her physical examination.

Koilonychia, as seen in our patient above, is a nail disease commonly seen in hypochromic anemia, especially iron deficiency anemia, and refers to abnormally thin nails that have lost their convexity, becoming flat and sometimes concave in shape

She was admitted directly to the intensive care unit after her hemoglobin was found to be critically low at 1.4 g/dL on two consecutive measurements with an unclear etiology of blood loss at the time of presentation. Note that no intravenous fluids were administered prior to obtaining the hemoglobin levels. Upon collecting further history from the patient, she revealed that she has had a lifetime history of extremely heavy menstrual periods: Since menarche at the age of 10 years when her periods started, she has been having irregular menstruation, with periods occurring every 2–3 weeks, sometimes more often. She bled heavily for the entire 5–7 day duration of her periods; she quantified soaking at least seven heavy flow pads each day with bright red blood as well as large-sized blood clots. Since the age of 30 years, her periods had also become increasingly heavier, with intermittent bleeding in between cycles, stating that lately she bled for “half of the month.” She denied any other sources of bleeding.

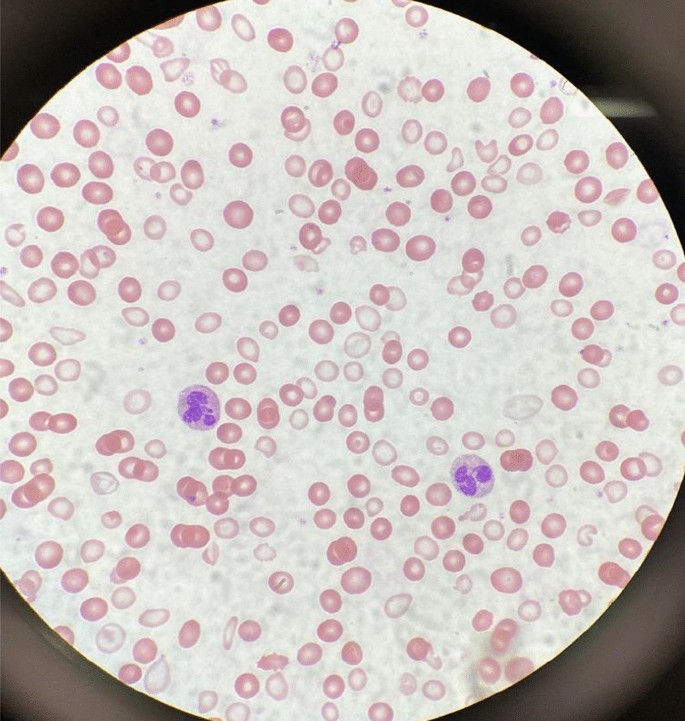

Initial laboratory data are summarized in Table 1 . Her hemoglobin (Hgb) level was critically low at 1.4 g/dL on arrival, with a low mean corpuscular volume (MCV) of < 50.0 fL. Hematocrit was also critically low at 5.8%. Red blood cell distribution width (RDW) was elevated to 34.5%, and absolute reticulocyte count was elevated to 31 × 10 9 /L. Iron panel results were consistent with iron deficiency anemia, showing a low serum iron level of 9 μg/dL, elevated total iron-binding capacity (TIBC) of 441 μg/dL, low Fe Sat of 2%, and low ferritin of 4 ng/mL. Vitamin B12, folate, hemolysis labs [lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), haptoglobin, bilirubin], and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) labs [prothrombin time (PT), partial thromboplastin time (PTT), fibrinogen, d -dimer] were all unremarkable. Platelet count was 232,000/mm 3 . Peripheral smear showed erythrocytes with marked microcytosis, anisocytosis, and hypochromia (Fig. 2 ). Of note, the patient did have a positive indirect antiglobulin test (IAT); however, she denied any history of pregnancy, prior transfusions, intravenous drug use, or intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). Her direct antiglobulin test (DAT) was negative.

A peripheral smear from the patient after receiving one packed red blood cell transfusion is shown. Small microcytic red blood cells are seen, many of which are hypochromic and have a large zone of pallor with a thin pink peripheral rim. A few characteristic poikilocytes (small elongated red cells also known as pencil cells) are also seen in addition to normal red blood cells (RBCs) likely from transfusion

A transvaginal ultrasound and endometrial biopsy were offered, but the patient declined. Instead, a computed tomography (CT) abdomen and pelvis with contrast was performed, which showed a 3.5-cm mass protruding into the endometrium, favored to represent an intracavitary submucosal leiomyoma (Fig. 3 ). Aside from her abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB), the patient was without any other significant personal history, family history, or lab abnormalities to explain her severe anemia.

Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast was obtained revealing an approximately 3.5 × 3.0 cm heterogeneously enhancing mass protruding into the endometrial canal favored to represent an intracavitary submucosal leiomyoma

The patient’s presenting symptoms of fatigue and dizziness are common and nonspecific symptoms with a wide range of etiologies. Based on her physical presentation—overall well-appearing nature with normal vital signs—as well as the duration of her symptoms, we focused our investigation on chronic subacute causes of fatigue and dizziness rather than acute medical causes. We initially considered a range of chronic medical conditions from cardiopulmonary to endocrinologic, metabolic, malignancy, rheumatologic, and neurological conditions, especially given her reported history of fall. However, once the patient’s lab work revealed a significantly abnormal complete blood count and iron panel, the direction of our workup shifted towards evaluating hematologic causes.

With such a critically low Hgb on presentation (1.4 g/dL), we evaluated for potential sources of blood loss and wanted to first rule out emergent, dangerous causes: the patient’s physical examination and reported history did not elicit any concern for traumatic hemorrhage or common gastrointestinal bleeding. She denied recent or current pregnancy. Her CT scan of abdomen and pelvis was unremarkable for any pathology other than a uterine fibroid. The microcytic nature of her anemia pointed away from nutritional deficiencies, and she lacked any other medical comorbidities such as alcohol use disorder, liver disease, or history of substance use. There was also no personal or family history of autoimmune disorders, and the patient denied any history of gastrointestinal or extraintestinal signs and/or symptoms concerning for absorptive disorders such as celiac disease. We also eliminated hemolytic causes of anemia as hemolysis labs were all normal. We considered the possibility of inherited or acquired bleeding disorders, but the patient denied any prior signs or symptoms of bleeding diatheses in her or her family. The patient’s reported history of menometrorrhagia led to the likely cause of her significant microcytic anemia as chronic blood loss from menstruation leading to iron deficiency.

Over the course of her 4-day hospital stay, she was transfused 5 units of packed red blood cells and received 2 g of intravenous iron dextran. Hematology and Gynecology were consulted, and the patient was administered a medroxyprogesterone (150 mg) intramuscular injection on hospital day 2. On hospital day 4, she was discharged home with follow-up plans. Her hemoglobin and hematocrit on discharge were 8.1 g/dL and 24.3%, respectively. Her symptoms of fatigue and dizziness had resolved, and she was back to her normal baseline ambulatory and activity level.

Discussion and conclusions

This patient presented with all the classic signs and symptoms of iron deficiency: anemia, fatigue, pallor, koilonychia, and labs revealing marked iron deficiency, microcytosis, elevated RDW, and low hemoglobin. To the best of our knowledge, this is the lowest recorded hemoglobin in an awake and alert patient breathing ambient air. There have been previous reports describing patients with critically low Hgb levels of < 2 g/dL: A case of a 21-year old woman with a history of long-lasting menorrhagia who presented with a Hgb of 1.7 g/dL was reported in 2013 [ 5 ]. This woman, although younger than our patient, was more hemodynamically unstable with a heart rate (HR) of 125 beats per minute. Her menorrhagia was also shorter lasting and presumably of larger volume, leading to this hemoglobin level. It is likely that her physiological regulatory mechanisms did not have a chance to fully compensate. A 29-year-old woman with celiac disease and bulimia nervosa was found to have a Hgb of 1.7 g/dL: she presented more dramatically with severe fatigue, abdominal pain and inability to stand or ambulate. She had a body mass index (BMI) of 15 along with other vitamin and micronutrient deficiencies, leading to a mixed picture of iron deficiency and non-iron deficiency anemia [ 6 ]. Both of these cases were of reproductive-age females; however, our patient was notably older (age difference of > 20 years) and had a longer period for physiologic adjustment and compensation.

Lower hemoglobin, though in the intraoperative setting, has also been reported in two cases—a patient undergoing cadaveric liver transplantation who suffered massive bleeding with associated hemodilution leading to a Hgb of 0.6 g/dL [ 7 ] and a patient with hemorrhagic shock and extreme hemodilution secondary to multiple stab wounds leading to a Hgb of 0.7 g/dL [ 8 ]. Both patients were hemodynamically unstable requiring inotropic and vasopressor support, had higher preoperative hemoglobin, and were resuscitated with large volumes of colloids and crystalloids leading to significant hemodilution. Both were intubated and received 100% supplemental oxygen, increasing both hemoglobin-bound and dissolved oxygen. Furthermore, it should be emphasized that the deep anesthesia and decreased body temperature in both these patients minimized oxygen consumption and increased the available oxygen in arterial blood [ 9 ].

Our case is remarkably unique with the lowest recorded hemoglobin not requiring cardiac or supplemental oxygen support. The patient was hemodynamically stable with a critically low hemoglobin likely due to chronic, decades-long iron deficiency anemia of blood loss. Confirmatory workup in the outpatient setting is ongoing. The degree of compensation our patient had undergone is impressive as she reported living a very active lifestyle prior to the onset of her symptoms (2 weeks prior to presentation), she routinely biked to work every day, and maintained a high level of daily physical activity without issue.

In addition, while the first priority during our patient’s hospital stay was treating her severe anemia, her education became an equally important component of her treatment plan. Our institution is the county hospital for the most populous county in the USA and serves as a safety-net hospital for many vulnerable populations, most of whom have low health literacy and a lack of awareness of when to seek care. This patient had been experiencing irregular menstrual periods for more than three decades and never sought care for her heavy bleeding. She, in fact, had not seen a primary care doctor for many years nor visited a gynecologist before. We emphasized the importance of close follow-up, self-monitoring of her symptoms, and risks with continued heavy bleeding. It is important to note that, despite the compensatory mechanisms, complications of chronic anemia left untreated are not minor and can negatively impact cardiovascular function, cause worsening of chronic conditions, and eventually lead to the development of multiorgan failure and even death [ 10 , 11 ].

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Kassebaum NJ. The global burden of anemia. Hematol Oncol Clin. 2016;30(2):247–308.

Article Google Scholar

Donnez J. Menometrorrhagia during the premenopause: an overview. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2011;27(sup1):1114–9.

Cook JD, Skikne BS, Lynch SR, Reusser ME. Estimates of iron sufficiency in the US population. Blood. 1986;68(3):726–31.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Palacios S. The management of iron deficiency in menometrorrhagia. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2011;27(sup1):1126–30.

Can Ç, Gulactı U, Kurtoglu E. An extremely low hemoglobin level due to menorrhagia and iron deficiency anemia in a patient with mental retardation. Int Med J. 2013;20(6):735–6.

Google Scholar

Jost PJ, Stengel SM, Huber W, Sarbia M, Peschel C, Duyster J. Very severe iron-deficiency anemia in a patient with celiac disease and bulimia nervosa: a case report. Int J Hematol. 2005;82(4):310–1.

Kariya T, Ito N, Kitamura T, Yamada Y. Recovery from extreme hemodilution (hemoglobin level of 0.6 g/dL) in cadaveric liver transplantation. A A Case Rep. 2015;4(10):132.

Dai J, Tu W, Yang Z, Lin R. Intraoperative management of extreme hemodilution in a patient with a severed axillary artery. Anesth Analg. 2010;111(5):1204–6.

Koehntop DE, Belani KG. Acute severe hemodilution to a hemoglobin of 1.3 g/dl tolerated in the presence of mild hypothermia. J Am Soc Anesthesiol. 1999;90(6):1798–9.

Georgieva Z, Georgieva M. Compensatory and adaptive changes in microcirculation and left ventricular function of patients with chronic iron-deficiency anaemia. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 1997;17(1):21–30.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Lanier JB, Park JJ, Callahan RC. Anemia in older adults. Am Fam Phys. 2018;98(7):437–42.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

No funding to be declared.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Audrey L. Chai & Owen Y. Huang

Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Rastko Rakočević & Peter Chung

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

AC, OH, RR, and PC managed the presented case. AC performed the literature search. AC, OH, and RR collected all data and images. AC and OH drafted the article. RR and PC provided critical revision of the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Audrey L. Chai .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Chai, A.L., Huang, O.Y., Rakočević, R. et al. Critical iron deficiency anemia with record low hemoglobin: a case report. J Med Case Reports 15 , 472 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-021-03024-9

Download citation

Received : 25 March 2021

Accepted : 21 July 2021

Published : 13 September 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-021-03024-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Menometrorrhagia

- Iron deficiency

- Critical care

- Transfusion

Journal of Medical Case Reports

ISSN: 1752-1947

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter

- v.39(3); Jul-Sep 2017

Patients with very severe anemia: a case series

a Ospedale Civile di Cecina, Cecina, Italy

Alessandro Ferretti

b Ospedale Civile di Livorno, Livorno, Italy

Nicola Mumoli

Dear Editor,

Anemia occurs commonly worldwide and at all ages of life 1 and, although frequently overlooked, it affects mortality, morbidity and quality of life, even when mild. 2 , 3 The prevalence of anemia varies widely depending on its definition. The World Health Organization has established some cut-off hemoglobin (Hb) levels, stratified by gender and in part by age, to define the presence of anemia. 4 For adults, these levels are less than 12 g/dL for women and less than 13 g/dL for men, although these cut-off points may not be fully appropriate for the elderly. 5 Severe anemia has been defined as Hb <8.0 g/dL for both genders. However, hemoglobin is a simple surrogate marker for the disease that has provoked anemia. To treat anemias simply restoring a “safer” hemoglobin level (i.e., by means of transfusions or erythropoietin) may be very different than curing them by eliminating the causes that had provoked the condition. Moreover, several reports have shown that both transfusions and erythropoiesis stimulating agents may indeed carry an increased risk of adverse events. Therefore, it is quite surprisingly that in health services, anemia continues to be regarded as a “minor” disease, even when severe, to be assigned to the ambulatory setting in the absence of a robust body of literature to support this common practice.

In Italy, disorders of red blood cells in people older than 17 years [International Classification of Diseases – ninth revision Clinical Modification (ICD-IX-CM) codes 280–285] “outside urgencies” are considered not to be appropriate for hospital admission, regardless of the severity of the Hb deficiency or the presence of important comorbidities, including a reduced functional capacity in older people. 6 We believe that to rely on assumptions of this kind in advance of evidence may carry a risk to induce some potentially deleterious consequences, including overuse of blood transfusions to reach an Hb level “safe” for emergency room discharge rather than patient clinical status. Historically, and in current guidelines, 7 the indication for transfusion comes from both Hb concentration and the clinical scenario; to transfuse in order to avoid hospital admission should be regarded as unethical.

We conducted an observational, prospective study of all patients admitted to an Internal Medicine ward with very severe anemia, aiming to explore the clinical and assistential burden of severely anemic patients admitted to the hospital. Patients with an Hb concentration of 6 g/dL or less were eligible. Those presenting with overt hemorrhage or acute anemia were excluded. Patients were managed as usual, and no diagnostic or therapeutic procedure was performed for study purposes alone. In defining the main diagnosis at discharge, our standard procedure was to select first the procedure that had absorbed the largest amount of resources, accordingly to a predefined hierarchy ( Table 1 ) and then to choose the consequent diagnosis. Accordingly to our laboratory, we defined microcytic anemia as all cases with a mean corpuscular volume (MCV) of less than 81 fL, and macrocytic anemia as those with a MCV of more than 98 fL and normocytic anemia as all others. Thrombocytopenia was defined as an absolute platelet count of less than 150 × 10 9 /L; leukopenia as a white blood cell absolute count of less than 4.0 × 10 9 /L and lymphopenia as an absolute lymphocyte count of less than 1.1 × 10 9 /L.

Hierarchy of the procedures for International Classification of Diseases (ninth revision) Clinical Modification coding.

| 1. Open surgery |

| 2. Endoscopic surgical procedures |

| 3. Other invasive diagnostic or therapeutic procedures |

| 4. Procedures with closed biopsy of organ or tissues |

| 5. All other diagnostic or therapeutic procedures |

The main outcome of the study was all-cause, in-hospital mortality. Secondary outcomes were one-year mortality and the percentage of admissions for anemia that were lost to a retrospective analysis based only on coding. Continuous variables are expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD) or as medians with minimum and maximum values when data did not have a normal distribution; categorical data are given as counts and percentages. The Institutional Review Board approved the study, which was carried out and is reported according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for observational studies. 8

Between October 2009 and June 2015, 86 patients were admitted for very severe anemia. Of these, 61 (71%) were women and 25 (29%) were men; eight patients (9.3%) came from nursing homes, one from a prison and the remaining cases were from home. The mean age was 76.8 ± 15.6 (range: 33–100). Seventy-one patients (82.5%) were 65 years or older. Nine of the patients (six women and three men) died during hospitalization (10.5%); the remaining 77 patients were discharged and followed up for about 170 patient-years. Deceased patients were older than discharged patients: mean age was 90 ± 10 vs. 75.5 ± 15.7 ( p -value <0.01). During the same period, general in-hospital mortality was 12.3%. Mean follow-up was 806 days (range: 16–2072 days) during which time 32 more patients died. Mean time to death was 412 days. The cumulative percentages of death at 1, 3 and 12 months were 3.9%, 13.0% and 29.9%, respectively. When in-hospital mortality was included and added to one-month mortality, the corresponding figures became 13.9%, 22.1% and 37.2%. Hematological data are shown in Table 2 . There were no significant differences in mean Hb and MCV, or in the presence of cytopenias other than anemia. However, discharged patients more often had microcytic anemias (54.5%) compared to deceased patients, whose anemias were more often normocytic or macrocytic (77.8%). Patients with a normocytic anemia had an increased risk to die in the hospital when compared with those with microcytic anemia (OR 7.5; 95% confidence interval: 1.3–43.1; p -value <0.05). Lymphopenia, a surrogate marker for hyponutrition, was more prevalent in deceased patients (44.4% vs. 32.5%).

Hematological data.

| Discharged 77 (89.5%) | Deceased 9 (10.5%) | -Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Hb, g/dL – (SD) | 5.02 (0.81) | 5.43 (0.71) | ns |

| Mean MCV, fL – (SD) | 85.4 (20.7) | 88.4 (16.6) | ns |

| Microcytic – (%) | 42 (54.5) | 2 (22.2) | ns |

| Normocytic – (%) | 14 (18.2) | 5 (55.6) | <0.05 |

| Macrocytic – (%) | 21 (27.3) | 2 (22.2) | ns |

| Thrombocytopenia – (%) | 14 (18.2) | 2 (22.2) | ns |

| Leukopenia – (%) | 12 (15.6) | 1 (11.1) | ns |

| Lymphopenia – (%) | 25 (32.5) | 4 (44.4) | ns |

A total of 295 units of packed red cells were transfused to the 77 discharged patients (mean: 3.8), and 29 units to the nine deceased patients (mean: 3.2). One patient who died refused blood transfusions because of religious beliefs. Patients discharged alive were submitted to 77 invasive procedures: 39 to esophagogastroduodenoscopy, 23 to colonoscopy, four to capsular videoendoscopy (preceded by radiologic study of gastrointestinal tract in all four cases) and 11 to bone marrow biopsies. Administrative data was complete for 85 cases (98.8%). Diagnosis Related Groups (DRG) according to the ICD-IX-CM coding are shown in Table 3 ; three were surgical, and the remaining were clinical. Only 31/85 cases were coded as DRG 395 (red blood cell disorders – age >17), so about 63% of patients admitted for anemia would have been lost if this survey had been conducted retrospectively on discharge data. The mean reimbursement was 3165 euros.

Diagnosis Related Groups (DRG) accordingly to International Classification of Diseases (ninth revision) Clinical Modification coding.

| DRG | Type | Number of cases |

|---|---|---|

| 12 - Degenerative nervous system disorders | MED | 1 |

| 14 - Intracranial hemorrhage or cerebral infarction | MED | 1 |

| 122 - Circulatory disorders W AMI W/O major comp, discharged alive | MED | 1 |

| 123 - Circulatory disorders W AMI, expired | MED | 1 |

| 135 - Cardiac congenital & valvular disorders age >17W CC | MED | 1 |

| 138 - Cardiac arrhythmia & conduction disorders W CC | MED | 1 |

| 142 - Syncope & collapse W/O CC | MED | 1 |

| 144 - Other circulatory system diagnoses W CC | MED | 1 |

| 172 - Digestive malignancy W CC | MED | 6 |

| 174 - Gastrointestinal hemorrhage W CC | MED | 8 |

| 179 - Inflammatory bowel disease | MED | 1 |

| 180 - Gastrointestinal obstruction W CC | MED | 1 |

| 182 - Esophagitis, gastroent & misc digest disorders age >17W CC | MED | 4 |

| 188 - Other digestive system diagnoses AGE >17W CC | MED | 1 |

| 189 - Other digestive system diagnoses age >17 W/O CC | MED | 1 |

| 190 - Other digestive system diagnoses age 0–17 | MED | 1 |

| 239 - Pathological fractures & musculoskeletal & conn tiss malignancy | MED | 1 |

| 271 - Skin ulcers | MED | 1 |

| 304 - Kidney, ureter & major bladder proc for non-neopl W CC | SURG | 1 |

| 310 - Transurethral procedures W CC | SURG | 1 |

| 316 - Renal failure | MED | 2 |

| 395 - Red blood cell disorders age >17 | MED | 31 |

| • Iron deficiency anemia | 19 | |

| • Secondary or not specified anemia | 6 | |

| • Myelodysplasia | 2 | |

| • Pancytopenia | 2 | |

| • Megaloblastic anemia | 2 | |

| 397 - Coagulation disorders | MED | 2 |

| 403 - Lymphoma & non-acute leukemia W CC | MED | 2 |

| 473 - Acute leukemia W/O major O.R. procedure age >17 | MED | 1 |

| 570 - Major small & large bowel procedures W CC W/O major GI DX | SURG | 1 |

| 571 - Major esophageal disorders | MED | 1 |

| 574 - Major hematologic/immunologic dx excep sickle cell crisis & coag | MED | 6 |

| 576 - Septicemia w mechanical ventilator w/0 96+ hours age >17 | MED | 4 |

| All | 85 |

In this preliminary study, we report data on a sample of 86 consecutive, unselected elderly patients (82.5% of whom were 65 years or older). In-hospital mortality was 10.5%, but more than one third of these patients eventually died within a year after the index admission. Discharged patients, as compared with those who died in the hospital, had microcytic anemias more often (54.5% vs. 22.2%). Conversely, deceased patients had a high prevalence of normocytic anemias (18.2% vs. 55.6%). We speculate that microcytic anemia could have been more often the expression of a single and possibly curable disease, whereas normocytic anemias should be the result of multiple comorbidities that played the main role in causing death. In our study, we demonstrated that very severe anemia is not a benign condition with high mortality, and we question the advisability of hospitalization. In many cases anemia could be managed without transfusions (i.e., iron and vitamin B12 deficiency, chronic renal insufficiency, myelodysplasia and chemotherapy-related anemia), but this is often impossible without patient monitoring, and there is a risk of overuse of blood transfusions in this kind of patient in order to discharge them from the Emergency Department. To clarify this issue there is a need for prospective, randomized studies; indeed in our cohort, 63% of discharge diagnoses were not in the DRG 395 group, and would have been missed if we conducted an investigation based on administrative data only. We acknowledge some limitations of this study beyond its observational nature. This is a single-center experience, and results may not be reproducible in other contexts. However, we recruited all consecutive patients with very severe anemia over a period of more than five years, and we excluded only patients with acute anemia from bleeding. Furthermore, with about 170 patient-years of observation, we think that data on mortality are sufficiently robust. We enrolled patients on the basis of an arbitrary threshold of Hb that we defined as “very severe”. Indeed, 33 patients had Hb less than 5.0 g/dL, and 13 less than 4 g/dL, values that should be regarded as life threatening, especially in old, comorbid patients. There is little doubt that if we chose a more permissive approach (i.e., an Hb level of 7.0–8.0 g/dL), we would have recruited a wider sample of patients. To study patients with less severe anemia however, was not in our interest, since we focused on the prognosis of patients for whom there are scarce data in the literature. Our patients were transfused with three to four units of packed red cells each. Due to the observational design of the study, we were not able to elucidate if there was a detrimental effect of transfusions on patient outcomes. Finally, we did not evaluate the impact of comorbidities on mortality in this cohort of patients, but we are planning a follow-up study to address this important question.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Complete Your CE

Course case studies, external link, this link leads outside of the netce site to:.

While we have selected sites that we believe offer good, reliable information, we are not responsible for the content provided. Furthermore, these links do not constitute an endorsement of these organizations or their programs by NetCE, and none should be inferred.

Anemia in the Elderly

Course #99084 - $30 -

#99084: Anemia in the Elderly

Your certificate(s) of completion have been emailed to

- Back to Course Home

- Review the course material online or in print.

- Complete the course evaluation.

- Review your Transcript to view and print your Certificate of Completion. Your date of completion will be the date (Pacific Time) the course was electronically submitted for credit, with no exceptions. Partial credit is not available.

CASE STUDY 1

Patient H is a White woman, 89 years of age, who resides in a skilled nursing facility. She is being evaluated due to an Hgb level of 8.1 g/dL. She is ambulatory with a rolling walker, generally alert, and oriented with some mild cognitive impairment. She is compliant with medical treatments and takes medications as prescribed. Her medical history is positive for congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic kidney disease, and osteoarthritis. She is oxygen dependent on 2 L/minute per nasal cannula. She is bright and outgoing and verbalizes multiple vague physical complaints.

During her last hospitalization, one year ago for pneumonia, the nephrologist and pulmonologist told Patient H there was not much else that could be done for her. Despite the poor prognosis, her multiple medical conditions stabilized and she completed a rehabilitation program. She enjoys participating in activities and has developed friendships with some other residents. Over the past year, she has been treated for multiple infections, including bronchitis and multiple urinary tract infections.

Patient H's chief complaint is of feeling tired and short of breath at times. She also complains of arthritic pains in her neck and hands. Review of systems is notable for hearing loss, dentures, glasses, and dyspnea, mostly with exertion. She has occasional palpitations of the heart and orthopnea at times. Her bowel movements are regular, and she has not noticed any blood in the stool. She has 1+ chronic edema of the legs, which is about usual for her. She has not had a mammogram for five years, and she has not had a dual energy x-ray absorptiometry scan, colonoscopy, or other preventive care recently.

Patient H's record indicates an allergy to sulfa drugs and penicillin. She also has completed advance directives (a do not resuscitate order and a living will). She is taking the following medications:

Amlodipine besylate (Norvasc): 5 mg/day

Calcium carbonate (OsCal) with vitamin D twice daily

Polyethylene glycol powder (Miralax): 17 g in 8 oz liquid daily

Furosemide (Lasix): 40 mg/day

Escitalopram (Lexapro): 20 mg/day

Prednisone: 10 mg/day

Omeprazole (Prilosec): 20 mg/day

Cinacalcet (Sensipar): 30 mg/day

Simvastatin (Zocor): 20 mg at bedtime

Tiotropium oral inhalation (Spiriva): 1 cap per inhalation device daily

Vitamin B12: 1,000 mcg twice daily

Enteric-coated aspirin: 81 g/day

Upon physical examination, Patient H appears well-nourished and groomed. She is mildly short of breath at rest but in no apparent pain or distress. She is 5 feet 6 inches tall and weighs 156 pounds. Her vital signs indicate a blood pressure of 132/84 mm Hg; pulse 72 beats/minute; temperature 97.4 degrees F; respirations 20 breaths/minute; and oxygen saturation 94% on 2 L/minute. Her oropharynx is clear, and her neck is supple. There is no lymphadenopathy. The patient is hard of hearing and wears glasses for distance and reading.

Patient H's heart rate is slightly irregular, with a soft systolic ejection murmur. Evaluation of her lungs indicates diminished breath sounds in the bases with no adventitious sounds. The abdomen is soft and non-tender, with active bowel sounds and no signs of hepatosplenomegaly. As noted, Patient H has 1+ pitting chronic edema and vascular changes to lower extremities. There are no active skin lesions. Neurologic assessment shows no focal deficit. Extremity strength is rated 4 out of 5. A mini-mental status exam is administered, and the patient scores 22/30, indicating mild cognitive impairment.

Blood is drawn and sent to the laboratory for CBC and a basic metabolic panel. The results are:

Leukocytes: 5,700 cells/mcL

RBC: 3.02 million cells/mcL

Hgb: 8.1 g/dL

MCH: 26.5 Hgb/cell

RDW-CV: 15.8%

Platelets: 150,000 cells/mcL

Glucose: 82 mg/dL

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN): 34 mg/dL

Creatinine: 1.4 mg/dL

GFR: 38 mL/minute/1.73 m2

Patient H is in no apparent distress at present, but she appears to have anemia, as evidenced by the low Hgb. She has chronic kidney disease (stage 3), which may be contributing to the anemia. Further laboratory evaluation is necessary to determine the etiology of the anemia and to determine if specialty referral to gastroenterologist or hematologist is necessary. The clinician orders an iron profile, vitamin B12 and folate levels, reticulocyte count, and stool for occult blood. The results of this testing are:

Vitamin B12: 1,996 pg/mL

Folate: 9.9 mcM

Ferritin: 20 ng/mL

Serum iron: 26 mcg/dL

Unsaturated iron binding capacity: 216 mcg/dL

Total iron binding capacity: 242 mcg/dL

Transferrin saturation: 11%

Reticulocyte count: 1%

Stool for occult blood: Negative (three samples)

Vitamin B12 is a water-soluble vitamin that is excreted in urine, so a high level is generally not significant. The folate level is sufficient, while the ferritin level is considered low-to-normal. The iron profile shows a low level of iron in the blood; this may be caused by gastrointestinal bleeding or by inadequate absorption of iron by the body. Patient H has medical conditions that can cause elevated cytokines, which would interfere with iron absorption. If her ferritin level was high, which it is not, it would suggest AI/ACD. Therefore, the patient appears to have anemia secondary to chronic kidney disease and possibly inadequate iron absorption and processing.

Prior to initiating treatment with an ESA, the patient is evaluated for a history of cancer, as these agents may cause progression/recurrence of cancer. Before writing the prescription for darbepoetin alfa, the clinician signs the ESA APPRISE Oncology Patient and Healthcare Professional Acknowledgement Form to document discussing the risks associated with darbepoetin alfa with the patient. The lowest dose that will prevent blood transfusion is prescribed.

The multidisciplinary team works with Patient H to develop a treatment plan. It is determined that treating the anemia will improve the patient's quality of life. The patient is prescribed ferrous sulfate 325 mg twice daily. Because vitamin C facilitates iron absorption, the iron can be given with a glass of orange juice or other citrus juice (not grapefruit). Iron must not be given with calcium, milk products, and certain medications as they can interfere with absorption. The patient should be monitored for the development of constipation and the need for stool softeners. In addition, darbepoetin alfa 40 mcg is prescribed, to be administered subcutaneously every week. This requires significant monitoring. Hgb and HCT should be measured on the day patient is to receive the injection, and the drug should be held if the Hgb is greater than 11.5 g/dL. If a current Hgb level is unavailable, the drug should not be given.

Blood pressure should be measured twice daily after treatment with darbepoetin alfa is initiated. Staff must also monitor for symptoms of a deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolus (e.g., unilateral edema, cough, and/or hemoptysis). Daily exercise is encouraged to help reduce the risk of a blood clot.

After one month, Patient H has received darbepoetin alfa weekly for four weeks. She is also taking the ferrous sulfate and a stool softener. The review of systems is unchanged from the previous evaluation. The physical examination is also unchanged aside from a 1-pound weight loss. No new complaints or problems are reported. A review of the patient's vital signs shows a blood pressure of 130/80 mm Hg; pulse 78 beats/minute; temperature 97.8 degrees F; and oxygen saturation 97 on 2 L/minute. Her Hgb levels over the last month have improved:

Week 1: 8.4 g/dL

Week 2: 9.2 g/dL

Week 3: 9.6 g/dL

Week 4: 10.1 g/dL

No side effects from darbepoetin alfa have been observed. Patient H's blood pressure remains stable, with no signs or symptoms of a blood clot.

The clinician orders the weekly monitoring of Hgb and HCT to continue with the darbepoetin alfa held if the Hgb is greater than 11.5 g/dL. If the medication is held more than once, the clinician will re-evaluate the dosage and frequency. The patient may only need the injection once or twice a month after the anemia is stabilized. The clinician also reduces the patient's vitamin B12 supplement to daily (rather than twice daily) and reduces her prednisone dose to 5 mg/day.

Patient H's initial complaint was of shortness of breath and fatigue. These symptoms may have been related to the anemia or may have been a chronic complaint secondary to her congestive heart failure and COPD. The decreased hematocrit level is likely contributing to the patient's symptomatic heart failure. By exploring her condition further, it was determined that treating the anemia might improve the patient's quality of life and prevent the necessity for more extreme interventions (e.g., blood transfusion). Patient H was informed of the potential side effects of darbepoetin alfa and agreed to take it to prevent transfer to the hospital for blood transfusion.

The patient's condition was monitored closely, with weekly blood draws for Hgb. Her blood pressure remained stable, and no signs of complications were detected. Her shortness of breath and fatigue improved as the treatment progressed and her Hgb level rose above 10 g/dL. This allowed her to be more active.

For patients with terminal or end-stage conditions, treatment of anemia can restore or preserve their quality of life. Treating problems that could potentially cause suffering, while avoiding futile care, is the goal for patients with a life-limiting condition. Anemia affects the quality of life in elders by causing fatigue, poor endurance, and shortness of breath, and alleviating these symptoms can allow for more activity and comfort.

CASE STUDY 2

Patient P is a White man, 92 years of age, who resides in an assisted living facility. He uses a motorized scooter for mobility but can ambulate short distances with his rolling walker. He requires assistance with medication administration and attends community meals three times a day. His daughter visits once a week and assists with laundry and transports to medical appointments.

Patient P is brought to the primary care clinic by his daughter. She states that he is very fatigued and is not performing his usual daily tasks. He sleeps more than is usual and must be coaxed to attend the community meals. At times, he has refused to take medications that the staff attempt to administer. The patient minimizes his symptoms saying, "What do you expect? I'm 92 years old." Patient P's medical history is positive for Parkinson disease, hypertension, COPD, osteoporosis, compression fracture to the lumbosacral spine, and weight loss. He is a widower and reports no tobacco use and rarely drinking beer or wine. His chief presenting complaints are fatigue, shortness of breath, chronic back and leg pain, and poor appetite.

On review of systems, the patient is noted to be hard of hearing and wearing a hearing aid. Vision is adequate with correction. He wears dentures and denies pain or difficulty with mastication. He has difficulty swallowing large pills, and his caregivers crush his medications. He states his appetite is not good; he has lost 15 pounds over the last year. Patient P denies chest pain, but complains of shortness of breath. This occurs when he exerts himself and often when he lays down. He has a regular bowel movement every one to two days and denies nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea. He has not had dyspepsia but does state he does not seem to be able to eat as much as he used to (early satiety). He complains of nonradiating pain in his lower back. All other review of systems is non-contributory. Patient P has previously been tried on antiparkinsonian medications and osteoporosis medications that were discontinued due to unacceptable side effects. He is currently taking the following medications:

Atenolol (Tenormin): 25 mg twice daily

Vitamin D3: 1,000 units/day

Calcium carbonate: 500 mg three times every day

Vitamin B12: 1,000 mcg/day

Amlodipine (Norvasc): 10 mg/day

Omeprazole: 20 mg/day

Multivitamin daily

Acetaminophen (Tylenol): 650 mg three times daily routinely

Stool softener twice daily

Tramadol (Ultram): 50 mg every six hours as needed

Upon physical examination, Patient P appears frail but well groomed; he is in no apparent distress. He is 5 feet 5 inches tall and weighs 134 pounds. His vital signs indicate a blood pressure of 110/64 mm Hg; pulse 82 beats/minute (regular rate and rhythm); temperature 97.8 degrees F; respirations 22 breaths/minute; and oxygen saturation 91% on room air.

As noted, the patient is hard of hearing with hearing aid and wears glasses. There is no evidence of lymphadenopathy or carotid bruit. His oropharynx is clear. His lungs are clear to auscultations, with diminished air flow in lung bases. The abdomen is soft and non-tender, not distended, with bowel sounds active in four quadrants. There is no hepatosplenomegaly. Extremities are clear of edema. Vascular changes are noted on both legs, and the toenails are thickened. The patient displays dry, flaky skin of lower extremities. Tenderness is noted over the lumbar spine with palpation. Disuse atrophy is noted to the extremities. Chronic skin lesions are also present, with actinic keratoses on the nose and forehead. Neurologic assessment reveals fine resting tremor of both hands and flat affect. Strength is equal bilaterally with strong hand grasps. Gait and balance are unsteady.

The clinician orders Patient P's medical records and diagnostics from previous care providers. She also requests a CBC with differential, a complete metabolic profile, and thyroid studies. A home health care evaluation is also recommended to determine if rehabilitation services would be appropriate. Patient P's laboratory studies indicate:

Leukocytes: 5,400 cells/mcL

RBC: 2.95 million cells/mcL

Hgb: 8.7 g/dL

MCH: 29.4 Hgb/cell

MCHC: 33.3%

RDW-CV: 13.7%

Platelets: 289,000 cells/mcL

Glucose: 77 mg/dL

BUN: 20 mg/dL

Sodium: 139 mEq/L

Potassium: 4.5 mEq/L

Chloride: 104 mmol/L

Carbon dioxide: 27 mmol/L

Creatinine: 0.9 mg/dL

Calcium: 8.8 mg/dL

GFR: Greater than 60 mL/minute/1.73 m2

Thyroid-stimulating hormone: 2.88 mIU/L

The low RBC, Hgb, and HCT indicate that the patient has a normocytic, normochromic anemia. However, blood-loss anemia is not ruled out by lack of microcytosis. If the blood loss is recent, changes to the cells may not yet be evident. The RDW-CV is normal, which may indicate a lack of erythropoietic response. Further laboratory evaluation is indicated.

The clinician requests an iron profile, ferritin level, folate level, vitamin B12 level, reticulocyte count, and stool for occult blood. The results of this testing are:

Vitamin B12: 1,006 pg/mL

Folate: 17.2 mcM

Ferritin: 246 ng/mL

Serum iron: 38 mcg/dL

Total iron binding capacity: 197 mcg/dL

Transferrin saturation: 27%

Reticulocyte count: 1.2%

Stool for occult blood: Negative on two samples, mildly positive on third sample

These findings indicate the patient is not deficient in vitamin B12 or folate. The serum iron is low while the ferritin level is high, suggesting adequate iron stores that are not being utilized by the body. This is a diagnostic indicator of anemia of chronic inflammation. The total iron binding capacity is low, showing that the blood's ability to bind transferrin with iron is reduced. Patient P has signs of a "mixed" anemia, the result of both ACI and gastrointestinal blood loss. Elderly patients often have more than one etiology contributing to the anemia, and all the possible causes should be thoroughly evaluated.

One of the stools for occult blood is positive, which may be representative of intermittent gastrointestinal bleeding. The clinician refers the patient to a gastroenterologist for further diagnostic evaluation. An endoscopy and colonoscopy should be performed if the patient and healthcare surrogate are willing. He is also prescribed a 5% lidocaine patch to be applied to his lower back in the morning and to be removed at bedtime.

Patient P visits a gastroenterologist, who performs an endoscopy and a colonoscopy. He is found to have several polyps in the large intestine, which are removed and biopsied during the colonoscopy. He tolerates the procedures well and has no adverse effects. The polyps are found to be benign.

One month later, Patient P returns to the clinic for follow-up. His review of systems is unchanged, although he reports improvement in his lower back pain. His vital signs are all stable. A CBC is completed to monitor the anemia, and the results are:

Leukocytes: 5,600 cells/mcL

RBC: 3.36 million cells/mcL

Hgb: 9.6 g/dL

MCV: 88.0 fL

MCH: 28.7 Hgb/cell

MCHC: 32.5%

RDW-CV: 14.9%

Platelets: 262,000 cells/mcL

Patient P's RBC, Hgb, and HCT have improved slightly. The RDW-CV has also increased, indicating an improved erythropoietic response. The removal of the colon polyps, which may have been causing some intermittent bleeding contributing to the anemia, appears to have improved the patient's condition. Patient P is instructed to return in one month for additional follow-up.

Patient P is a frail, elderly patient with multiple medical problems. From a primary care perspective, it is important to identify any new or existing medical problems that can be treated and improved. Elderly persons often present with multiple vague complaints that do not point to any one disorder. Laboratory evaluation is crucial to narrow down the diagnostic differential.

Because there is an upward trend in the CBC values, the necessity of a blood transfusion is reduced. However, if the anemia worsens, a hematology consult may be necessary. At 92 years of age, the patient is at risk for myelodysplasia, but if present, lower values of leukocytes, RBCs, and platelets would be expected.

While the use of an ESA might result in an improvement in elderly patients, there are multiple side effects and precautions associated with their use. For Patient P, they should be avoided unless truly necessary to prevent the need for transfusions.

- About NetCE

- About TRC Healthcare

- Do Not Sell My Personal Information

Copyright © 2024 NetCE · Contact Us

- ASH Foundation

- Log in or create an account

- Publications

- Diversity Equity and Inclusion

- Global Initiatives

- Resources for Hematology Fellows

- American Society of Hematology

- Hematopoiesis Case Studies

Case Study: A 12-Year-Old Boy With Normocytic Anemia and Bone Pain

- Agenda for Nematology Research

- Precision Medicine

- Genome Editing and Gene Therapy

- Immunologic Treatment

- Research Support and Funding

The following case study focuses on a 12-year-old boy from Guyana who is referred by his family physician for jaundice, normocytic anemia, and recurrent acute bone pains. Test your knowledge by reading the background information below and making the proper selections.

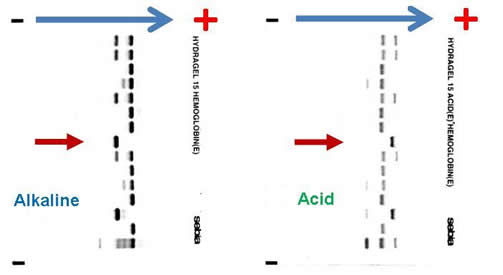

Complete blood count (CBC) reveals a hemoglobin of 6.5 g/dL, MCV 82.3 fL, platelet count 465,000 /µL, white blood cell count 9,800 /µL, absolute neutrophil count 8,500 /µL, reticulocyte count 7 percent, and bilirubin 84 mg/dL. Blood film revealed numerous sickle cells. Sickle solubility test is positive. Alkaline and acid electrophoresis reveal the following (The patient’s sample is denoted by red arrow.):

What is the patient’s hemoglobinopathy genotype based on these results?

- Hb SC compound heterozygote

- Hb SS homozygote

- Hb S/beta-0-thalassemia compound heterozygote

- Hb S/C-Harlem (aka C-Georgetown) compound heterozygote

- Hb S/D-Punjab

Two years later, at age 14, the patient presented to the emergency department with acute onset (3 hours) of left hemiparesis. Non-contrast computed tomography of the brain demonstrated an acute right MCA infarct. The patient has no history of thromboembolic disease, no family history of venous or arterial thrombosis, and no artherosclerotic risk factors for stroke. His CBC at the time demonstrated a hemoglobin of 87 g/dL, hematocrit 0.240, MCV 89.0 fL, platelet count 650,000 /µL, white blood cell count 11,200 /µL, and ANC 9,800 /µL. You are consulted as the hematologist on call along with stroke team.

What would be the best treatment option for this patient?

- Acetylsalicylic acid 160 mg chewable

- Thrombolytic therapy (e.g., tissue plasminogen activator)

- Red cell “top-up” transfusion with target hematocrit of 0.300

- Red cell exchange transfusion with target hematocrit of 0.300 and hemoglobin S of less than 30 percent

- Unfractionated heparin IV infusion

Answers: 1. B; 2. D

Explanation

The combination of the patient’s ethnic origin, medical history, current presentation, CBC, and peripheral blood film findings are most suggestive of a sickling disorder. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and hemoglobin gel electrophoresis are the two most commonly employed techniques in the investigation of hemoglobinopathies. The diagnosis of any sickling disorder, however, requires two laboratory investigations, one of which must be the sickle solubility test. The lower limit of detection of hemoglobin S in a sickle solubility test is approximately 15 to 20 percent. All possibilities listed in question 1 will result in a positive sickle solubility test, provided that it is not performed under the following conditions: infant < 6 months or post-transfusion, both of which may result in a false negative result.

Hemoglobin gel electrophoresis separates hemoglobin variants based on the overall charge of the hemoglobin molecule. There is a single band aligned at the S position on the alkaline gel (pH 8.6), given that the orientation of the reference marker from anode (positive) to cathode (negative) is A F S C. Several other hemoglobin variants co-migrate with the S on the alkaline electrophoresis, the most notable of which are hemoglobin D, G, and Lepore. Similarly E, O-Arab, and A2 co-migrate with C. On the acid gel (pH 6.8), there is also one band aligned at the S position, given that the orientation of the reference marker from cathode (negative) to anode (cathode) is F A S C. O-Arab co-migrates with S on the acid gel, and D, G, Lepore, E, A2 co-migrate with A. The interpretation most compatible with the evidence provided above is that the patient is an Hb SS homozygote. He cannot be an Hb SC compound heterozygote, or there would be two bands on the alkaline and acid gel, at the S and C positions, respectively. If he is an Hb S/C-Harlem (aka C-Georgetown) compound heterozygote, he would have a band at the S and C positions (C-Harlem co-migrate with C), respectively, on the alkaline gel and a band in the S position on the acid gel. Interestingly, Hb C-Harlem is actually a hemoglobin variant with two mutations on the β-globin chain and was thought to have risen from a crossover between an Hb S ( Glutamic acid to Valine substitution at the 6th position) and Hb Korle-Bu (Aspartic acid to Asparagine at the 73 rd position) β-globin gene. Thus Hb C-Harlem was thought to have arisen from a cross-over between an Hb S and Hb Korle-Bu beta-globin gene. Also, he cannot have Hb S/D-Punjab, since this would produce two bands on the acid gel, one at the A position (Hb D-Punjab co-migrates with Hb A) and the other at the S position. Finally, he is very unlikely to be an Hb S/β-0-thalassemia compound heterozygote given his normal MCV.

The most likely cause of this patient’s right MCA territory cerebral infarction is sickle cell disease (SCD). The yearly stroke rate of a child with SCD is between 0.5 and 1.0 percent compared with 0.003 percent in a healthy child. Children with trans-cranial Doppler velocity of > 200 cm/s are at even higher risk of stroke, between 10.0 and 13.0 percent yearly. Moreover, 22 percent of SCD patients have evidence of silent cerebral infarcts. Risk factors for stroke include prior transient ischemic attack, low steady-state hemoglobin, acute chest syndrome, and elevated systolic blood pressure. Transfusion with the goal of Hb S > 30 percent and hematocrit of 0.300 is the only proven method of treating stroke in an acute setting and in primary and secondary prophylaxis against stroke in patients with SCD. In an acute setting, the only feasible means of achieving this goal is by exchange transfusion. Although transfusion has not been tested as part of a randomized control trial in SCD patients with acute stroke, retrospective cohort studies have demonstrated that transfusion can reduce the acute mortality and morbidity with the aggressive use of exchange transfusion at presentation. The STOP trial has shown that chronic transfusion therapy with a pre-transfusion Hb S target of < 30 percent is effective in preventing stroke in SCD patients with high transcranial Doppler velocity (> 200 cm/s) compared with no transfusion. STOP2 further shows that the discontinuation of transfusion for SCD patients with elevated transcranial Doppler velocity results in a reversion to high rate of stroke. Currently, the Silent Cerebral Infarct Transfusion (SIT) trial is evaluating whether transfusion will reduce the risk of overt strokes or further silent infarcts in patients with proven silent cerebral infarcts.

The author would like to acknowledge Dr. William F. Brien from Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, for providing the image of the alkaline and acid gel electrophoresis.

Further Reading

- Bain BJ. Haemoglobinopathy Diagnosis, 2nd ed. 2006. Blackwell Publishing. Oxford, UK.

- Adams RJ. Big strokes in small persons . Arch Neurol. 2007;64:1567-1574.

- Platt OS. Prevention and management of stroke in sickle cell anemia . Hematology 2006. 2006;1:54-57.

- Swerdlow PS. Red cell exchange in sickle cell disease . Hematology 2006. 2006;1:48-53. Adams RJ, McKie VC, Hsu L, et al. Prevention of a first stroke by transfusions in children with sickle cell anemia and abnormal results on transcranial Doppler ultrasonography . N Engl J Med. 1998;339:5-11.

- Adams RJ, Brambilla D. Discontinuing prophylactic transfusions used to prevent stroke in sickle cell disease . N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2769-2778.

Case study submitted by Kevin Kuo, MD, University of Toronto.

American Society of Hematology. (1). Case Study: A 12-Year-Old Boy With Normocytic Anemia and Bone Pain. Retrieved from https://www.hematology.org/education/trainees/fellows/case-studies/child-normocytic-anemia-bone-pain .

American Society of Hematology. "Case Study: A 12-Year-Old Boy With Normocytic Anemia and Bone Pain." Hematology.org. https://www.hematology.org/education/trainees/fellows/case-studies/child-normocytic-anemia-bone-pain (label-accessed July 02, 2024).

"American Society of Hematology." Case Study: A 12-Year-Old Boy With Normocytic Anemia and Bone Pain, 02 Jul. 2024 , https://www.hematology.org/education/trainees/fellows/case-studies/child-normocytic-anemia-bone-pain .

Citation Manager Formats

The Daily Show Fan Page

Explore the latest interviews, correspondent coverage, best-of moments and more from The Daily Show.

The Daily Show

S29 E68 • July 8, 2024

Host Jon Stewart returns to his place behind the desk for an unvarnished look at the 2024 election, with expert analysis from the Daily Show news team.

Extended Interviews

The Daily Show Tickets

Attend a Live Taping

Find out how you can see The Daily Show live and in-person as a member of the studio audience.

Best of Jon Stewart

The Weekly Show with Jon Stewart

New Episodes Thursdays

Jon Stewart and special guests tackle complex issues.

Powerful Politicos

The Daily Show Shop

Great Things Are in Store

Become the proud owner of exclusive gear, including clothing, drinkware and must-have accessories.

About The Daily Show

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Case Study 89: Anemia - Oncologic and Hematologic Disorders. Which lab values are normal, and which are abnormal? Normal Values: I. WBC - 7600/mm II. Platelets - 151,00/mm III. Vitamin B12 - 414 pg/mL Abnormal Values: I. HCT - 27% II. HGB - 8 mg/dL III. Red Blood Cells Indices - a.

Name: Lubna Hameed Case Study 89 Anemia G. is a 78-year-old widow who relies on her late husband's Social Security income for all of her expenses. Over the past few years, G. has eaten less and less meat because of her financial situation and the trouble of preparing a meal "just for me." She struggles financially to buy medicines for the ...

Case Study 89: Anemia. SCENARIO: G.C. is a 78- year-old widow who relies on her late husband' s Social Security income f or all of her. expens es. Over the past fe w years, G.C. has eat en less and less meat because of her financial situation. and the trouble of preparing a meal "just f or me. " She str uggles financially to buy medicines ...

Question: Case Study 89 AnemiaDifficulty: BeginningSetting: Senior clinicIndex Words: iron deficiency anemia, laboratory values, data interpretation, iron therapy, iron-rich foodsScenarioG.C. is a 78-year-old widow who relies on her late husband's Social Security income for all of her expenses.

Case Study 89 Monique Mesa Erica Porras Jessica Scheller Amy Tran Lindsay Wood Danielle Wright 4. What are some causative factors for the type of anemia G.C. has? A slight decrease in Hgb occurs with aging (Mauk, 2014)But more often the disorder is attributed to an iron

Sickle cell anemia case study 89. Hemolytic anemias. Click the card to flip 👆. Characterized by premature destruction of RBCs , retention in the body of iron, biliruben, and other products of hemoglobin breakdown, and an increase in erythrooiesis (RBC REPRODUCTION) Click the card to flip 👆. 1 / 16.

Anemia and menometrorrhagia are common and co-occurring conditions in women of premenopausal age [1, 2].Analysis of the global anemia burden from 1990 to 2010 revealed that the prevalence of iron deficiency anemia, although declining every year, remained significantly high, affecting almost one in every five women [].Menstruation is considered largely responsible for the depletion of body iron ...

Background. Anemia and menometrorrhagia are common and co-occurring conditions in women of premenopausal age [1, 2].Analysis of the global anemia burden from 1990 to 2010 revealed that the prevalence of iron deficiency anemia, although declining every year, remained significantly high, affecting almost one in every five women [].Menstruation is considered largely responsible for the depletion ...

Between October 2009 and June 2015, 86 patients were admitted for very severe anemia. Of these, 61 (71%) were women and 25 (29%) were men; eight patients (9.3%) came from nursing homes, one from a prison and the remaining cases were from home. The mean age was 76.8 ± 15.6 (range: 33-100).

View case study 89.docx from NURSING MISC at Alverno College. Diana Le Case Study 89 - Oncologic and Hematologic Disorders - Anemia 1. WBC= WNL (normal:5,000-10,000) Hct=low (normal:38-47) Hgb=low

CASE STUDY 89 SICKLE CELL ANEMIA For the Disease Summary for this case study see the CD-ROM PATIENT CASE s Chief Complaints My arms and legs hurt a lot more than usual today. The ibuprofen has stopped working and I need something stronger. I may have overdone it at the gym." History I.T. is an 18-year-old African American male with sickle cell ...

View Notes - Case Study 89 Anemia.doc from NUR 112 at Forsyth Technical Community College. Bethany Shelton February 21, 2017 Case Study 89 1. Which lab values are normal, and which are abnormal? 2.

Case Study 89 Sickle Cell Anemia Both sets of Questions Full Copy.pdf. Solutions Available. West Coast University. NURSING 420. Case Study # 88 (1).pdf. Solutions Available. Chaffey College. PATHO 403. Case_Study_89. University of New Mexico, Main Campus. NURS 240. Case Study 89 Sickle Cell.docx. Solutions Available.

Case Study 89 Anemia G.C. is a 78-year-old widow who relies on her late husband's Social Security income for all of her expenses. Over the past few years, G.C. has eaten less and less meat because of her financial situation and the trouble of preparing a meal "just for me." She struggles financially to buy medicines for the treatment of hyper- tension and arthritis.

Anemia-2: Overview and Select Cases. Marc Zumberg Associate Professor Division of Hematology/Oncology. Complete blood count with indices. MCV-indication of RBC size. RDW-indication of RBC size variation. Examination of the peripheral blood smear. Reticulocyte count-measurement of newly produced young rbc's. Stool guiac.

Case Study 89 - Sickle Cell Anemia. What precipitating factors probably triggered this painful crisis? The precipitating factors that probably triggered this painful crisis include working out and playing basketball, low oxygen levels due to lack of profusion from over exertion and dehydration.

CASE STUDY 1. Patient H is a White woman, 89 years of age, who resides in a skilled nursing facility. She is being evaluated due to an Hgb level of 8.1 g/dL. ... Anemia affects the quality of life in elders by causing fatigue, poor endurance, and shortness of breath, and alleviating these symptoms can allow for more activity and comfort. CASE ...

NUR 1460 Case Study 89 Anemia/Case Study 89 Anemia/Case Study 89 Anemia/Case Study 89 Anemia/Case Study 89 Anemia/Case Study 89 Anemia/Case Study 89 Anemia/Case Study ...

The following case study focuses on a 12-year-old boy from Guyana who is referred by his family physician for jaundice, normocytic anemia, and recurrent acute bone pains. Test your knowledge by reading the background information below and making the proper selections. Complete blood count (CBC) reveals a hemoglobin of 6.5 g/dL, MCV 82.3 fL ...

Dr. Nicole de Paz (Pediatrics): A 20-month-old boy was admitted to the pediatric inten-sive care unit of this hospital because of severe anemia. The patient was well until 5 days before admission ...

Case Study 89 Anemia.pdf - Pages 4. Total views 12. Florida State College at Jacksonville. NUR. NUR 1460C. woodmn4. 10/6/2020. View full document. Students also studied. Case Study Neuro.pdf. Chamberlain College of Nursing.

Case Studies /. Anemia in a 42-year-old woman. Brought to you by Merck & Co, Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA (known as MSD outside the US and Canada) — dedicated to using leading-edge science to save and improve lives around the world. Learn more about the MSD Manuals and our commitment to Global Medical Knowledge.

Yu-Han Chao Case Study 89. Sickle Cell Anemia. The precipitating factors that probably triggered this painful crisis are "a workout at the gym that was more vigorous than usual" and dehydration as the patient forgot his water bottle. The strain of decreased oxygenation can cause RBCs to sickle in a patient with HbS, and dehydration ...

The source for The Daily Show fans, with episodes hosted by Jon Stewart, Ronny Chieng, Jordan Klepper, Dulcé Sloan and more, plus interviews, highlights and The Weekly Show podcast.

HCR 240 - Case Study 89 ( Sickle Cell Anemia). / HCR 240 - Case Study 89 ( Sickle Cell Anemia). 1) What precipitating factors probably triggered this painful crisis? The precipitating factors that probably triggered this painful crisis include working out and playing basketball, low oxygen level... [Show more]

3. Discussion. The first case of aplastic anemia described in the literature was a pregnant woman who died of postpartum hemorrhage in 1888. Although there has been no proven causal association between pregnancy and aplastic anemia, it cannot be ruled out that pregnancy may have some influence on the disease [].In some cases, women with aplastic anemia experience worsening symptoms or relapse ...

Patho case study answers to everything. quincey hamilton case study 89 sickle cell anemia what precipitating factors probably triggered this painful crisis? Skip to document. University; High School. Books; ... Case Study 89. Sickle Cell Anemia. 1.)