Cochrane Switzerland

Pharmacological treatments for psoriasis - living systematic review with network meta analysis.

Psoriasis is a frequent inflammatory skin disease affecting between 2% and 8% of the general population. Psoriasis affects deeply quality of life. There is currently no cure for psoriasis, but various treatments can help to control the symptoms; thus, long-term treatment is usually needed.

In an interview authors Dr Laurence Le Cleach and Emilie Sbidian explain their Cochrane Living Systematic Review .

What is a « Living Systematic Review » ?

A systematic review, which is continually updated, incorporating relevant new evidence as it becomes available.

Read the full Review

Cochrane Skin

Systemic treatments for chronic plaque psoriasis: a living nma.

Our first living systematic review has been published. Read the interview with the authors from our French Satellite https://www.cochrane.org/news/living-systematic-review-pharmacological-treatments-psoriasis-network-meta-analysis and the review itself. Monthly searches are ongoing and the team are working on an update for later this year.

Associations of novel complete blood count-derived inflammatory markers with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Published: 24 May 2024

- Volume 316 , article number 228 , ( 2024 )

Cite this article

- Yu-Cheng Liu 1 ,

- Shu-Han Chuang 2 ,

- Yu-Pin Chen 3 , 4 &

- Yi-Hsien Shih ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2095-7064 5 , 6

63 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Psoriasis is an immune-mediated disorder which primarily affects skin and has systemic inflammatory involvement. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), and monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR) are novel complete blood count (CBC)-derived markers which can reflect systemic inflammation. This study aimed to systematically investigate the associations of NLR, PLR, SII, and MLR with psoriasis. This study was performed in compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses statement. A comprehensive search of Pubmed, Embase, Scopus, and Google Scholar was conducted for relevant studies. Observational studies evaluating the correlations of NLR, PLR, SII, or MLR with psoriasis were included. The primary outcomes were the associations of these inflammatory markers with the presence and severity of psoriasis. The random-effect model was applied for meta-analysis. 36 studies comprising 4794 psoriasis patients and 55,121 individuals in total were included in the meta-analysis. All inflammatory markers were significantly increased in psoriasis groups compared to healthy controls (NLR: MD = 0.59, 95% CI: 0.47–0.7; PLR: MD = 15.53, 95% CI: 8.48–22.58; SII: MD = 111.58, 95% CI: 61.49-161.68; MLR: MD = 0.034, 95% CI: 0.021–0.048; all p < 0.001). Between-group mean differences in NLR and PLR were positively correlated with the mean scores of Psoriasis Area Severity Index (NLR: p = 0.041; PLR: p = 0.021). NLR, PLR, SII, and MLR are associated with the presence of psoriasis. NLR and PLR serve as significant indicators of psoriasis severity. These novel CBC-derived markers constitute potential targets in the screening and monitoring of psoriasis.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Associations between the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratios and the presence and severity of psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, platelet to lymphocyte ratio, and other hematological parameters in psoriasis patients

Data availability.

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Armstrong AW, Read C, Pathophysiology (2020) Clinical presentation, and treatment of psoriasis: a review. JAMA 323(19):1945–1960. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.4006

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Christophers E (2001) Psoriasis – epidemiology and clinical spectrum. Clin Exp Dermatol 26(4):314–320. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2230.2001.00832.x

Nestle FO, Kaplan DH, Barker J, Psoriasis (2009) N Engl J Med 361(5):496–509. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra0804595

Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, Ciragil P (2005) Serum levels of TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm 2005(5):273–279. https://doi.org/10.1155/mi.2005.273

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Korman NJ (2020) Management of psoriasis as a systemic disease: what is the evidence? Br J Dermatol 182(4):840–848. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.18245

Hjuler KF, Gormsen LC, Vendelbo MH, Egeberg A, Nielsen J, Iversen L (2017) Increased global arterial and subcutaneous adipose tissue inflammation in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 176(3):732–740. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.15149

Mehta NN, Yu Y, Saboury B, Foroughi N, Krishnamoorthy P, Raper A et al (2011) Systemic and vascular inflammation in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis as measured by [18F]-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission tomography–computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT): a pilot study. Arch Dermatol 147(9):1031–1039. https://doi.org/10.1001/archdermatol.2011.119

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Youn SW, Kang SY, Kim SA, Park GY, Lee WW (2015) Subclinical systemic and vascular inflammation detected by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography in patients with mild psoriasis. J Dermatol 42(6):559–566. https://doi.org/10.1111/1346-8138.12859

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Beygi S, Lajevardi V, Abedini R (2014) C-reactive protein in psoriasis: a review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 28(6):700–711. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.12257

Chuang SH, Chang CH (2024) Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio and lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio in glaucoma: a meta-analysis. Biomark Med 18(1):39–49. https://doi.org/10.2217/bmm-2023-0651

Erre GL, Paliogiannis P, Castagna F, Mangoni AA, Carru C, Passiu G et al (2019) Meta-analysis of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in rheumatoid arthritis. Eur J Clin Invest 49(1):e13037. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.13037

Fu W, Fu H, Ye W, Han Y, Liu X, Zhu S et al (2021) Peripheral blood neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in inflammatory bowel disease and disease activity: a meta-analysis. Int Immunopharmacol 101(Pt B):108235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2021.108235

Liu Y-C, Yang T-I, Huang S-W, Kuo Y-J, Chen Y-P (2022) Associations of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio with osteoporosis: a Meta-analysis. Diagnostics (Basel) 12(12):2968. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12122968

Wu Y, Chen Y, Yang X, Chen L, Yang Y (2016) Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) were associated with disease activity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Int Immunopharmacol 36:94–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2016.04.006

Cupp MA, Cariolou M, Tzoulaki I, Aune D, Evangelou E, Berlanga-Taylor AJ (2020) Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and cancer prognosis: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies. BMC Med 18(1):360. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01817-1

Kou J, Huang J, Li J, Wu Z, Ni L (2023) Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts prognosis and responsiveness to immunotherapy in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta–analysis. Clin Exp Med 23(7):3895–3905. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10238-023-01035-y

Ng WW-S, Lam S-M, Yan W-W, Shum H-P, NLR (2022) MLR, PLR and RDW to predict outcome and differentiate between viral and bacterial pneumonia in the intensive care unit. Sci Rep 12(1):15974. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-20385-3

Ni J, Wang H, Li Y, Shu Y, Liu Y (2019) Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) as a prognostic marker for in-hospital mortality of patients with sepsis: a secondary analysis based on a single-center, retrospective, cohort study. Med (Baltim) 98(46):e18029. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000018029

Article Google Scholar

Zhou X, Du Y, Huang Z, Xu J, Qiu T, Wang J et al (2014) Prognostic value of PLR in various cancers: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 9(6):e101119. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0101119

Paliogiannis P, Satta R, Deligia G, Farina G, Bassu S, Mangoni AA et al (2019) Associations between the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratios and the presence and severity of psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Exp Med 19(1):37–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10238-018-0538-x

Ye JH, Zhang Y, Naidoo K, Ye S (2024) Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dermatol Res 316(3):85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-024-02823-6

Kim DS, Shin D, Lee MS, Kim HJ, Kim DY, Kim SM et al (2016) Assessments of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and platelet to lymphocyte ratio in Korean patients with psoriasis vulgaris and psoriatic arthritis. J Dermatol 43(3):305–310. https://doi.org/10.1111/1346-8138.13061

Şener G, İnan Yuksel E, Gökdeniz O, Karaman K, Canat HD (2023) The relationship of hematological parameters and C-reactive protein (CRP) with Disease Presence, Severity, and response to systemic therapy in patients with psoriasis. Cureus 15(8):e43790. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.43790

Sugimoto E, Matsuda H, Shibata S, Mizuno Y, Koyama A, Li L et al (2023) Impact of pretreatment systemic inflammatory markers on treatment persistence with Biologics and Conventional systemic therapy: a retrospective study of patients with Psoriasis Vulgaris and Psoriatic Arthritis. J Clin Med 12(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12083046

Yorulmaz A, Hayran Y, Akpinar U, Yalcin B (2020) Systemic Immune-inflammation index (SII) predicts increased severity in Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis. Curr Health Sci J 46(4):352–357. https://doi.org/10.12865/chsj.46.04.05

Stang A (2010) Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol 25(9):603–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z

Luo D, Wan X, Liu J, Tong T (2018) Optimally estimating the sample mean from the sample size, median, mid-range, and/or mid-quartile range. Stat Methods Med Res 27(6):1785–1805. https://doi.org/10.1177/0962280216669183

Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T (2014) Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol 14:135. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-14-135

Aktaş Karabay E, Demir D, Aksu Çerman A (2020) Evaluation of monocyte to high-density lipoprotein ratio, lymphocytes, monocytes, and platelets in psoriasis. Bras Dermatol 95(1):40–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abd.2019.05.002

Amiri R, Iranmanesh B, Yazdizadeh K, Mohammadi S, Khalili M, Aflatoonian M (2023) The role of hematological markers in prediction of severity of psoriasis and associated arthritis. J Pak Assoc Dermatol 33(2):489–494

Google Scholar

Arısoy A, Karman K, Karayakalı M, Demirelli S, Seçkin HY, Çelik A et al (2017) Evaluation of ventricular repolarization features with novel electrocardiographic parameters (Tp-e, Tp-e/QT) in patients with psoriasis. Anatol J Cardiol 18(6):397–401. https://doi.org/10.14744/AnatolJCardiol.2017.7901

Arunadevi D, Raghavan V, Nott A (2022) Comparative and Correlative Study of Hematologic Parameters and selective inflammatory biomarkers in Psoriasis. Int J Nutr Pharmacol Neurol Dis 12(1):34–38. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijnpnd.ijnpnd_68_21

Ataseven A, Bilgin AU, Kurtipek GS (2014) The importance of neutrophil lymphocyte ratio in patients with psoriasis. Mater Sociomed 26(4):231–233

Çerman AA, Karabay EA, Altunay İK (2016) Evaluation of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and mean platelet volume in patients with psoriasis. Med Bull Sisli Etfal Hosp 50(2):137–141

COŞANSU NC, DİKİCİER BS (2020) Is there any association between the monocyte/lymphocyte ratio and the presence and severity of the disease in patients with psoriasis? A cross-sectional study. Sakarya Tıp Dergisi 10(3):430–436

Dincer Rota D, Tanacan E (2021) The utility of systemic-immune inflammation index for predicting the disease activation in patients with psoriasis. Int J Clin Pract 75(6):e14101. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.14101

Guo H-h, Chen R-x (2024) Association of systemic inflammation index with psoriasis risk and psoriasis severity: a retrospective cohort study of NHANES 2009 to 2014. Med (Baltim) 103(8):e37236. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000037236

Article CAS Google Scholar

Hammad R, Hamdino M, El-Nasser AM (2020) Role of Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, Mean platelet volume in Egyptian patients with Psoriasis Vulgaris. Egypt J Immunol 27(1):157–168

PubMed Google Scholar

Hoffmann JHO, Enk AH (2022) Evaluation of Psoriasis Area and Severity Index Thresholds as proxies for systemic inflammation on an individual patient level. Dermatology 238(4):609–614. https://doi.org/10.1159/000520163

Hong J, Lian N, Li M (2023) Association between the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and psoriasis: a cross-sectional study of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011–2014. BMJ Open 13(12):e077596. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-077596

Kemeriz F, Tuǧrul B, Tuncer SC (2020) C-reactive protein to albumin ratio: is a new parameter for the disease severity in patients with psoriasis vulgaris? Dermatologica Sinica 38(4):199–204. https://doi.org/10.4103/ds.ds_42_20

Ma R, Cui L, Cai J, Yang N, Wang Y, Chen Q et al (2024) Association between systemic immune inflammation index, systemic inflammation response index and adult psoriasis: evidence from NHANES. Front Immunol 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1323174

Melikoğlu M, Pala E (2023) Systemic Immune-inflammation index as a biomarker of Psoriasis Severity. Arch Basic Clin Res 5(2):291–295

Mishra S, Kadnur M, Jartarkar SR, Keloji H, Agarwal R, Babu S (2022) Correlation between serum uric acid, C-reactive protein, and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients with psoriasis: a case-control study. Turkderm - Turk Arch Dermatol Venereol 56(1):28–33. https://doi.org/10.4274/turkderm.galenos.2021.69797

Mondal S, Guha S, Saha A, Ghoshal L, Bandyopadhyay D (2022) Evaluation of Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in chronic plaque psoriasis. Indian J Dermatol 67(4):477. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijd.ijd_935_21

Nguyen HT, Hoang Vo LD, Pham NN (2023) Neutrophil-To-lymphocyte and platelet-To-lymphocyte ratios as inflammatory markers in psoriasis: a case-control study. Dermatol Rep 15(1). https://doi.org/10.4081/dr.2022.9516

Pektas SD, Tugbaalatas E, Yilmaz N (2016) Plateletcrit is potential biomarker for presence and severity of psoriasis vulgaris. Acta Med Mediterranea 32(6):1785–1790. https://doi.org/10.19193/0393-6384_2016_6_164

Polat M, Bugdayci G, Kaya H, Oğuzman H (2017) Evaluation of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in Turkish patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat 26(4):97–100. https://doi.org/10.15570/actaapa.2017.28

Pujani M, Agarwal C, Chauhan V, Agarwal S, Passi S, Singh K et al (2022) Platelet parameters, neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio, platelet lymphocyte ratio, red cell distribution width: can they serve as biomarkers in evaluation of severity of psoriasis? J Appl Hematol 13(2):95–102. https://doi.org/10.4103/joah.joah_195_20

Sen BB, Rifaioglu EN, Ekiz O, Inan MU, Sen T, Sen N (2014) Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio as a measure of systemic inflammation in psoriasis. Cutan Ocul Toxicol 33(3):223–227. https://doi.org/10.3109/15569527.2013.834498

Sikora M, Stec A, Chrabaszcz M, Waskiel-Burnat A, Zaremba M, Olszewska M et al (2019) Intestinal fatty acid binding protein, a Biomarker of Intestinal Barrier, is Associated with Severity of Psoriasis. J Clin Med 8(7). https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8071021

Sirin MC, Korkmaz S, Erturan I, Filiz B, Aridogan BC, Cetin ES et al (2020) Evaluation of monocyte to HDL cholesterol ratio and other inflammatory markers in patients with psoriasis. Bras Dermatol 95(5):575–582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abd.2020.02.008

Solak B, Dikicier BS, Erdem T (2017) Impact of elevated serum uric acid levels on systemic inflammation in patients with psoriasis. Angiology 68(3):266–270. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003319716657980

Sunbul M, Seckin D, Durmus E, Ozgen Z, Bozbay M, Bozbay A et al (2015) Assessment of arterial stiffness and cardiovascular hemodynamics by oscillometric method in psoriasis patients with normal cardiac functions. Heart Vessels 30(3):347–354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00380-014-0490-y

Toprak AE, Ozlu E, Ustunbas TK, Yalcınkaya E, Sogut S, Karadag AS (2016) Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio, serum endocan, and nesfatin-1 levels in patients with psoriasis vulgaris undergoing phototherapy treatment. Med Sci Monit 22:1232–1237. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.898240

Article CAS PubMed Central Google Scholar

Wang WM, Wu C, Gao YM, Li F, Yu XL, Jin HZ (2021) Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, platelet to lymphocyte ratio, and other hematological parameters in psoriasis patients. BMC Immunol 22(1):64. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12865-021-00454-4

Yavuz GÖ, Yavuz İH (2019) Novel inflammatory markers in patients with psoriasis. East J Med 24(1):63–68. https://doi.org/10.5505/ejm.2019.19327

Yildiz A, Ucmak D, Oylumlu M, Akkurt MZ, Yuksel M, Akil MA et al (2014) Assessment of atrial electromechanical delay and P-wave dispersion in patients with psoriasis. Echocardiography 31(9):1071–1076. https://doi.org/10.1111/echo.12530

Yurtdaş M, Yaylali YT, Kaya Y, Ozdemir M, Ozkan I, Aladağ N (2014) Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio may predict subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with psoriasis. Echocardiography 31(9):1095–1104. https://doi.org/10.1111/echo.12511

Zhao Y, Yang XT, Bai YP, Li LF (2023) Association of Complete Blood Cell Count-Derived inflammatory biomarkers with psoriasis and mortality. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 16:3267–3278. https://doi.org/10.2147/CCID.S437936

Chiang CC, Cheng WJ, Korinek M, Lin CY, Hwang TL (2019) Neutrophils in Psoriasis. Front Immunol 10:2376. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.02376

Golden JB, Groft SG, Squeri MV, Debanne SM, Ward NL, McCormick TS et al (2015) Chronic psoriatic skin inflammation leads to increased monocyte adhesion and aggregation. J Immunol 195(5):2006–2018. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1402307

Ingersoll MA, Platt AM, Potteaux S, Randolph GJ (2011) Monocyte trafficking in acute and chronic inflammation. Trends Immunol 32(10):470–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2011.05.001

Davizon-Castillo P, McMahon B, Aguila S, Bark D, Ashworth K, Allawzi A et al (2019) TNF-α-driven inflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction define the platelet hyperreactivity of aging. Blood 134(9):727–740. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2019000200

Herster F, Karbach S, Chatterjee M, Weber ANR, Platelets (2021) Underestimated regulators of Autoinflammation in Psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol 141(6):1395–1403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2020.12.025

Langewouters AM, van Erp PE, de Jong EM, van de Kerkhof PC (2008) Lymphocyte subsets in peripheral blood of patients with moderate-to-severe versus mild plaque psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res 300(3):107–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-007-0819-9

Núñez J, Miñana G, Bodí V, Núñez E, Sanchis J, Husser O et al (2011) Low lymphocyte count and cardiovascular diseases. Curr Med Chem 18(21):3226–3233. https://doi.org/10.2174/092986711796391633

Schulze-Koops H (2004) Lymphopenia and autoimmune diseases. Arthritis Res Ther 6(4):178. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar1208

Albayrak H (2023) Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, neutrophil-to-monocyte ratio, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, and systemic Immune-inflammation index in Psoriasis patients: response to treatment with Biological drugs. J Clin Med 12(17):5452. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12175452

Najar Nobari N, Shahidi Dadras M, Nasiri S, Abdollahimajd F, Gheisari M (2020) Neutrophil/platelet to lymphocyte ratio in monitoring of response to TNF-α inhibitors in psoriatic patients. Dermatol Ther 33(4):e13457. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.13457

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors have nothing to acknowledge.

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of General Medicine, Taipei Medical University Shuang Ho Hospital, New Taipei, 23561, Taiwan

Yu-Cheng Liu

Division of General Practice, Department of Medical Education, Changhua Christian Hospital, Changhua, 50006, Taiwan

Shu-Han Chuang

Department of Orthopedics, Taipei Municipal Wan Fang Hospital, Taipei, 11696, Taiwan

Yu-Pin Chen

Department of Orthopedics, School of Medicine, College of Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, 11031, Taiwan

Department of Dermatology, School of Medicine, College of Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, 11031, Taiwan

Yi-Hsien Shih

Department of Dermatology, Taipei Medical University Shuang Ho Hospital, New Taipei City, 23561, Taiwan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Yu-Cheng Liu and Yi-Hsien Shih contributed to the study conception and design. Outcome data synthesis, analysis, and interpretation was performed by Yu-Cheng Liu. Yu-Cheng Liu and Shu-Han Chuang were the main contributors in drafting the manuscript. Yu-Pin Chen and Yi-Hsien Shih revised the original manuscript and provided expert opinions on the relevance of the results to clinical practice. Yi-Hsien Shih was the corresponding author. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Yi-Hsien Shih .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Rights and permissions.

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Liu, YC., Chuang, SH., Chen, YP. et al. Associations of novel complete blood count-derived inflammatory markers with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dermatol Res 316 , 228 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-024-02994-2

Download citation

Received : 15 April 2024

Revised : 15 April 2024

Accepted : 26 April 2024

Published : 24 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-024-02994-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

- Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio

- Systemic immune-inflammation index

- Monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Topical treatments for chronic plaque psoriasis: an abridged Cochrane systematic review

Affiliations.

- 1 Center for Health Economics, University of York, York, United Kingdom. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 School of Medicine, Pharmacy, and Health, Durham University, Stockton-on-Tees, United Kingdom.

- 3 Academic Unit of Dermatology Research, University of Sheffield Medical School, Sheffield, United Kingdom.

- 4 Metaxis Ltd, Curbridge, United Kingdom.

- PMID: 24124809

- DOI: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.06.027

Background: Chronic plaque psoriasis is the most common type of psoriasis and is characterized by redness, thickness, and scaling. First-line management is with topical treatments.

Objective: We sought to undertake a Cochrane review of topical treatments for chronic plaque psoriasis.

Methods: We systematically searched major databases for randomized controlled trials. Trials reported improvement using a range of related measures; standardized, pooled findings were translated onto a 6-point improvement scale.

Results: The review included 177 randomized controlled trials with 34,808 participants, including 26 trials of scalp psoriasis and 6 trials of inverse and/or facial psoriasis. Typical trial duration was 3 to 8 weeks. When compared with placebo (emollient base), the average improvement for vitamin-D analogues and potent corticosteroids was approximately 1 point, dithranol 1.2 points, very potent corticosteroids 1.8 points, and combined vitamin-D analogue plus steroid 1.4 points once daily and 2.2 points twice daily. However, these are indicative benefits drawn from heterogeneous trial findings. Corticosteroids were more effective than vitamin D for treating psoriasis of the scalp. For both body and scalp psoriasis, potent corticosteroids were less likely than vitamin D to cause skin irritation.

Limitations: Reporting of benefits, adverse effects, and safety assessment methods was often inadequate. In many comparisons, heterogeneity made the size of treatment benefit uncertain.

Conclusions: Corticosteroids are as effective as vitamin-D analogues and cause less skin irritation. However, further research is needed to inform long-term maintenance treatment and provide appropriate safety data.

Keywords: BD; CI; IAGI; Investigator Assessment of Global Improvement; OD; SD; SMD; confidence interval; drug administration; drug safety; once daily; psoriasis; review; standard deviation; standardized mean difference; topical; treatment outcome; twice daily.

Copyright © 2013 American Academy of Dermatology, Inc. Published by Mosby, Inc. All rights reserved.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Systematic Review

- Administration, Topical

- Adrenal Cortex Hormones / therapeutic use

- Chronic Disease

- Psoriasis / drug therapy*

- Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

- Vitamin D / analogs & derivatives

- Vitamin D / therapeutic use

- Adrenal Cortex Hormones

- Systematic Review

- Open access

- Published: 23 May 2024

Systematic literature review of real-world evidence for treatments in HR+/HER2- second-line LABC/mBC after first-line treatment with CDK4/6i

- Veronique Lambert ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6984-0038 1 ,

- Sarah Kane ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0006-9341-4836 2 na1 ,

- Belal Howidi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1166-7631 2 na1 ,

- Bao-Ngoc Nguyen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6026-2270 2 na1 ,

- David Chandiwana ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0002-3499-2565 3 ,

- Yan Wu ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0008-3348-9232 1 ,

- Michelle Edwards ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0001-4292-3140 3 &

- Imtiaz A. Samjoo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1415-8055 2 na1

BMC Cancer volume 24 , Article number: 631 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

320 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 and 6 inhibitors (CDK4/6i) combined with endocrine therapy (ET) are currently recommended by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines and the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines as the first-line (1 L) treatment for patients with hormone receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative, locally advanced/metastatic breast cancer (HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC). Although there are many treatment options, there is no clear standard of care for patients following 1 L CDK4/6i. Understanding the real-world effectiveness of subsequent therapies may help to identify an unmet need in this patient population. This systematic literature review qualitatively synthesized effectiveness and safety outcomes for treatments received in the real-world setting after 1 L CDK4/6i therapy in patients with HR+/ HER2- LABC/mBC.

MEDLINE®, Embase, and Cochrane were searched using the Ovid® platform for real-world evidence studies published between 2015 and 2022. Grey literature was searched to identify relevant conference abstracts published from 2019 to 2022. The review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA guidelines (PROSPERO registration: CRD42023383914). Data were qualitatively synthesized and weighted average median real-world progression-free survival (rwPFS) was calculated for NCCN/ESMO-recommended post-1 L CDK4/6i treatment regimens.

Twenty records (9 full-text articles and 11 conference abstracts) encompassing 18 unique studies met the eligibility criteria and reported outcomes for second-line (2 L) treatments after 1 L CDK4/6i; no studies reported disaggregated outcomes in the third-line setting or beyond. Sixteen studies included NCCN/ESMO guideline-recommended treatments with the majority evaluating endocrine-based therapy; five studies on single-agent ET, six studies on mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors (mTORi) ± ET, and three studies with a mix of ET and/or mTORi. Chemotherapy outcomes were reported in 11 studies. The most assessed outcome was median rwPFS; the weighted average median rwPFS was calculated as 3.9 months (3.3-6.0 months) for single-agent ET, 3.6 months (2.5–4.9 months) for mTORi ± ET, 3.7 months for a mix of ET and/or mTORi (3.0–4.0 months), and 6.1 months (3.7–9.7 months) for chemotherapy. Very few studies reported other effectiveness outcomes and only two studies reported safety outcomes. Most studies had heterogeneity in patient- and disease-related characteristics.

Conclusions

The real-world effectiveness of current 2 L treatments post-1 L CDK4/6i are suboptimal, highlighting an unmet need for this patient population.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most diagnosed form of cancer in women with an estimated 2.3 million new cases diagnosed worldwide each year [ 1 ]. BC is the second leading cause of cancer death, accounting for 685,000 deaths worldwide per year [ 2 ]. By 2040, the global burden associated with BC is expected to surpass three million new cases and one million deaths annually (due to population growth and aging) [ 3 ]. Numerous factors contribute to global disparities in BC-related mortality rates, including delayed diagnosis, resulting in a high number of BC cases that have progressed to locally advanced BC (LABC) or metastatic BC (mBC) [ 4 , 5 , 6 ]. In the United States (US), the five-year survival rate for patients who progress to mBC is three times lower (31%) than the overall five-year survival rate for all stages (91%) [ 6 , 7 ].

Hormone receptor (HR) positive (i.e., estrogen receptor and/or progesterone receptor positive) coupled with negative human epidermal growth factor 2 (HER2) expression is the most common subtype of BC, accounting for ∼ 60–70% of all BC cases [ 8 , 9 ]. Historically, endocrine therapy (ET) through estrogen receptor modulation and/or estrogen deprivation has been the standard of care for first-line (1 L) treatment of HR-positive/HER2-negative (HR+/HER2-) mBC [ 10 ]. However, with the approval of the cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor (CDK4/6i) palbociclib in combination with the aromatase inhibitor (AI) letrozole in 2015 by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), 1 L treatment practice patterns have evolved such that CDK4/6i (either in combination with AIs or with fulvestrant) are currently considered the standard of care [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ]. Other CDK4/6i (ribociclib and abemaciclib) in combination with ET are approved for the treatment of HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC; 1 L use of ribociclib in combination with an AI was granted FDA approval in March 2017 for postmenopausal women (with expanded approval in July 2018 for pre/perimenopausal women and for use in 1 L with fulvestrant for patients with disease progression on ET as well as for postmenopausal women), and abemaciclib in combination with fulvestrant was granted FDA approval in September 2017 for patients with disease progression following ET and as monotherapy in cases where disease progression occurs following ET and prior chemotherapy in mBC (with expanded approval in February 2018 for use in 1 L in combination with an AI for postmenopausal women) [ 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 ].

Clinical trials investigating the addition of CDK4/6i to ET have demonstrated significant improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) and significant (ribociclib) or numerical (palbociclib and abemaciclib) improvement in overall survival (OS) compared to ET alone in patients with HR+/HER2- advanced or mBC, making this combination treatment the recommended option in the 1 L setting [ 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ]. However, disease progression occurs in a significant portion of patients after 1 L CDK4/6i treatment [ 28 ] and the optimal treatment sequence after progression on CDK4/6i remains unclear [ 29 ]. At the time of this review (literature search conducted December 14, 2022), guidelines by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) recommend various options for the treatment of HR+/HER2- advanced BC in the second-line (2 L) setting, including fulvestrant monotherapy, mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors (mTORi; e.g., everolimus) ± ET, alpelisib + fulvestrant (if phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha mutation positive [PIK3CA-m+]), poly-ADP ribose polymerase inhibitors (PARPi) including olaparib or talazoparib (if breast cancer gene/partner and localizer of BRCA2 positive [BRCA/PALB2m+]), and chemotherapy (in cases when a visceral crisis is present) [ 15 , 16 ]. CDK4/6i can also be used in 2 L [ 16 , 30 ]; however, limited data are available to support CDK4/6i rechallenge after its use in the 1 L setting [ 15 ]. Depending on treatments used in the 1 L and 2 L settings, treatment in the third-line setting is individualized based on the patient’s response to prior treatments, tumor load, duration of response, and patient preference [ 9 , 15 ]. Understanding subsequent treatments after 1 L CDK4/6i, and their associated effectiveness, is an important focus in BC research.

Treatment options for HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC continue to evolve, with ongoing research in both clinical trials and in the real-world setting. Real-world evidence (RWE) offers important insights into novel therapeutic regimens and the effectiveness of treatments for HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC. The effectiveness of the current treatment options following 1 L CDK4/6i therapy in the real-world setting highlights the unmet need in this patient population and may help to drive further research and drug development. In this study, we conducted a systematic literature review (SLR) to qualitatively summarize the effectiveness and safety of treatment regimens in the real-world setting after 1 L treatment with CDK4/6i in patients with HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC.

Literature search

An SLR was performed in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [ 31 ] and reported in alignment with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Literature Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [ 32 ] to identify all RWE studies assessing the effectiveness and safety of treatments used for patients with HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC following 1 L CDK4/6i therapy and received subsequent treatment in 2 L and beyond (2 L+). The Ovid® platform was used to search MEDLINE® (including Epub Ahead of Print and In-Process, In-Data-Review & Other Non-Indexed Citations), Ovid MEDLINE® Daily, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews by an experienced medical information specialist. The MEDLINE® search strategy was peer-reviewed independently by a senior medical information specialist before execution using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) checklist [ 33 ]. Searches were conducted on December 14, 2022. The review protocol was developed a priori and registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Review (PROSPERO; CRD42023383914) which outlined the population, intervention, comparator, outcome, and study design (PICOS) criteria and methodology used to conduct the review (Table 1 ).

Search strategies utilized a combination of controlled vocabulary (e.g., “HER2 Breast Cancer” or “HR Breast Cancer”) and keywords (e.g., “Retrospective studies”). Vocabulary and syntax were adjusted across databases. Published and validated filters were used to select for study design and were supplemented using additional medical subject headings (MeSH) terms and keywords to select for RWE and nonrandomized studies [ 34 ]. No language restrictions were included in the search strategy. Animal-only and opinion pieces were removed from the results. The search was limited to studies published between January 2015 and December 2022 to reflect the time at which FDA approval was granted for the first CDK4/6i agent (palbociclib) in combination with AI for the treatment of LABC/mBC [ 35 ]. Further search details are presented in Supplementary Material 1 .

Grey literature sources were also searched to identify relevant abstracts and posters published from January 2019 to December 2022 for prespecified relevant conferences including ESMO, San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (SABCS), American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR US), and the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR). A search of ClinicalTrials.gov was conducted to validate the findings from the database and grey literature searches.

Study selection, data extraction & weighted average calculation

Studies were screened for inclusion using DistillerSR Version 2.35 and 2.41 (DistillerSR Inc. 2021, Ottawa, Canada) by two independent reviewers based on the prespecified PICOS criteria (Table 1 ). A third reviewer was consulted to resolve any discrepancies during the screening process. Studies were included if they reported RWE on patients aged ≥ 18 years with HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC who received 1 L CDK4/6i treatment and received subsequent treatment in 2 L+. Studies were excluded if they reported the results of clinical trials (i.e., non-RWE), were published in any language other than English, and/or were published prior to 2015 (or prior to 2019 for conference abstracts and posters). For studies that met the eligibility criteria, data relating to study design and methodology, details of interventions, patient eligibility criteria and baseline characteristics, and outcome measures such as efficacy, safety, tolerability, and patient-reported outcomes (PROs), were extracted (as available) using a Microsoft Excel®-based data extraction form (Microsoft Corporation, WA, USA). Data extraction was performed by a single reviewer and was confirmed by a second reviewer. Multiple publications identified for the same RWE study, patient population, and setting that reported data for the same intervention were linked and extracted as a single publication. Weighted average median real-world progression-free survival (rwPFS) values were calculated by considering the contribution to the median rwPFS of each study proportional to its respective sample size. These weighted values were then used to compute the overall median rwPFS estimate.

Quality assessment

The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for nonrandomized (cohort) studies was used to assess the risk of bias for published, full-text studies [ 36 ]. The NOS allocates a maximum of nine points for the least risk of bias across three domains: (1) Formation of study groups (four points), (2) Comparability between study groups (two points), (3) Outcome ascertainment (three points). NOS scores can be categorized in three groups: very high risk of bias (0 to 3 points), high risk of bias (4 to 6), and low risk of bias (7 to 9) [ 37 ]. Risk of bias assessment was performed by one reviewer and validated by a second independent reviewer to verify accuracy. Due to limited methodological data by which to assess study quality, risk of bias assessment was not performed on conference abstracts or posters. An amendment to the PROSPERO record (CRD42023383914) for this study was submitted in relation to the quality assessment method (specifying usage of the NOS).

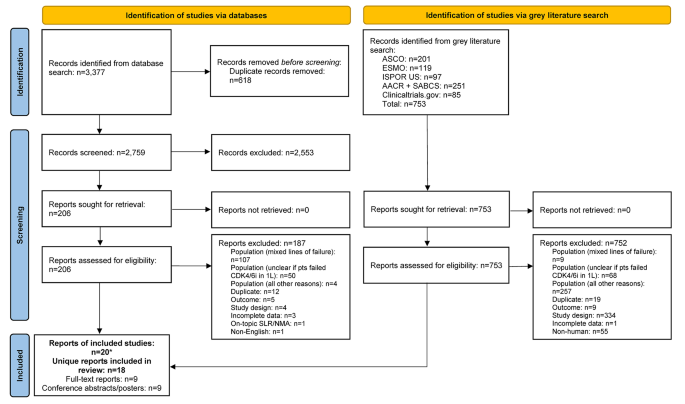

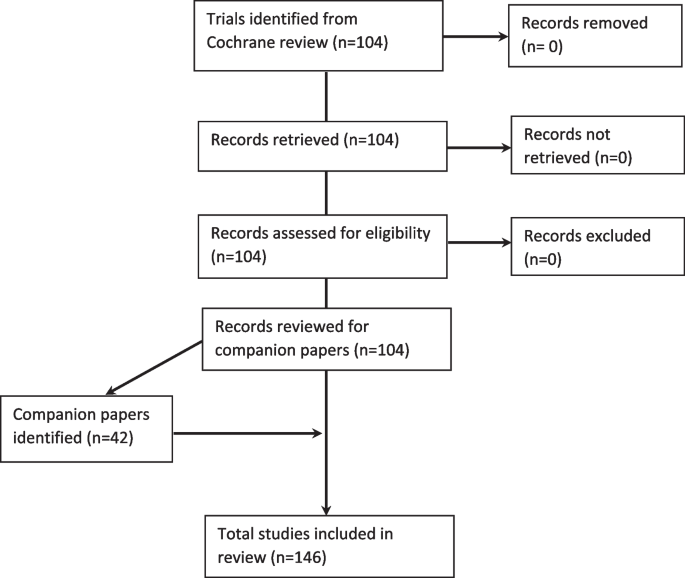

The database search identified 3,377 records; after removal of duplicates, 2,759 were screened at the title and abstract stage of which 2,553 were excluded. Out of the 206 reports retrieved and assessed for eligibility, an additional 187 records were excluded after full-text review; most of these studies were excluded for having patients with mixed lines of CDK4/6i treatment (i.e., did not receive CDK4/6i exclusively in 1 L) (Fig. 1 and Table S1 ). The grey literature search identified 753 records which were assessed for eligibility; of which 752 were excluded mainly due to the population not meeting the eligibility criteria (Fig. 1 ). In total, the literature searches identified 20 records (9 published full-text articles and 11 conference abstracts/posters) representing 18 unique RWE studies that met the inclusion criteria. The NOS quality scores for the included full-text articles are provided in Table S2 . The scores ranged from four to six points (out of a total score of nine) and the median score was five, indicating that all the studies suffered from a high risk of bias [ 37 ].

Most studies were retrospective analyses of chart reviews or medical registries, and all studies were published between 2017 and 2022 (Table S3 ). Nearly half of the RWE studies (8 out of 18 studies) were conducted in the US [ 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 ], while the remaining studies included sites in Canada, China, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the United Kingdom [ 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 ]. Sample sizes ranged from as few as 4 to as many as 839 patients across included studies, with patient age ranging from 26 to 86 years old.

Although treatment characteristics in the 1 L setting were not the focus of the present review, these details are captured in Table S3 . Briefly, several RWE studies reported 1 L CDK4/6i use in combination with ET (8 out of 18 studies) or as monotherapy (2 out of 18 studies) (Table S3 ). Treatments used in combination with 1 L CDK4/6i included letrozole, fulvestrant, exemestane, and anastrozole. Where reported (4 out of 18 studies), palbociclib was the most common 1 L CDK4/6i treatment. Many studies (8 out of 18 studies) did not report which specific CDK4/6i treatment(s) were used in 1 L or if its administration was in combination or monotherapy.

Characteristics of treatments after 1 L CDK4/6i therapy

Across all studies included in this review, effectiveness and safety data were only available for treatments administered in the 2 L setting after 1 L CDK4/6i treatment. No studies were identified that reported outcomes for patients treated in the third-line setting or beyond after 1 L CDK4/6i treatment. All 18 studies reported effectiveness outcomes in 2 L, with only two of these studies also describing 2 L safety outcomes. The distribution of outcomes reported in these studies is provided in Table S4 . Studies varied in their reporting of outcomes for 2 L treatments; some studies reported outcomes for a group of 2 L treatments while others described independent outcomes for specific 2 L treatments (i.e., everolimus, fulvestrant, or chemotherapy agents such as eribulin mesylate) [ 42 , 45 , 50 , 54 , 55 ]. Due to the heterogeneity in treatment classes reported in these studies, this data was categorized (as described below) to align with the guidelines provided by NCCN and ESMO [ 15 , 16 ]. The treatment class categorizations for the purpose of this review are: single-agent ET (patients who exclusively received a single-agent ET after 1 L CDK4/6i treatment), mTORi ± ET (patients who exclusively received an mTORi with or without ET after 1 L CDK4/6i treatment), mix of ET and/or mTORi (patients who may have received only ET, only mTORi, and/or both treatments but the studies in this group lacked sufficient information to categorize these patients in the “single-agent ET” or “mTOR ± ET” categories), and chemotherapy (patients who exclusively received chemotherapy after 1 L CDK4/6i treatment). Despite ESMO and NCCN guidelines indicating that limited evidence exists to support rechallenge with CDK4/6i after 1 L CDK4/6i treatment [ 15 , 16 ], two studies reported outcomes for this treatment approach. Data for such patients were categorized as “ CDK4/6i ± ET ” as it was unclear how many patients receiving CDK4/6i rechallenge received concurrent ET. All other patient groups that lacked sufficient information or did not report outcome/safety data independently (i.e., grouped patients with mixed treatments) to categorize as one of the treatment classes described above were grouped as “ other ”.

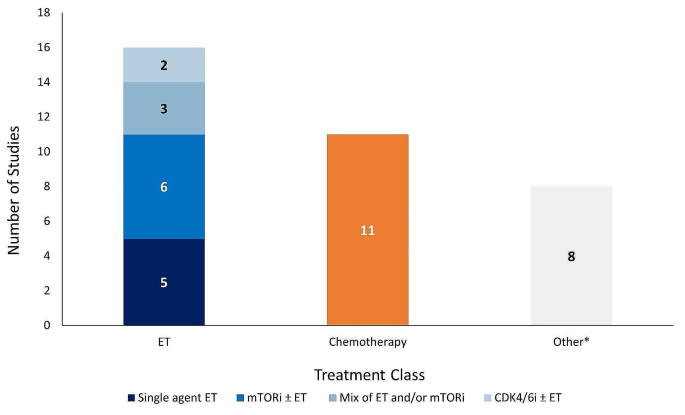

The majority of studies reported effectiveness outcomes for endocrine-based therapy after 1 L CDK4/6i treatment; five studies for single-agent ET, six studies for mTORi ± ET, and three studies for a mix of ET and/or mTORi (Fig. 2 ). Eleven studies reported effectiveness outcomes for chemotherapy after 1 L CDK4/6i treatment, and only two studies reported effectiveness outcomes for CDK4/6i rechallenge ± ET. Eight studies that described effectiveness outcomes were grouped into the “other” category. Safety data was only reported in two studies: one study evaluating the chemotherapy agent eribulin mesylate and one evaluating the mTORi everolimus.

Effectiveness outcomes

Real-world progression-free survival

Median rwPFS was described in 13 studies (Tables 2 and Table S5 ). Across the 13 studies, the median rwPFS ranged from 2.5 months [ 49 ] to 17.3 months [ 39 ]. Out of the 13 studies reporting median rwPFS, 10 studies reported median rwPFS for a 2 L treatment recommended by ESMO and NCCN guidelines, which ranged from 2.5 months [ 49 ] to 9.7 months [ 45 ].

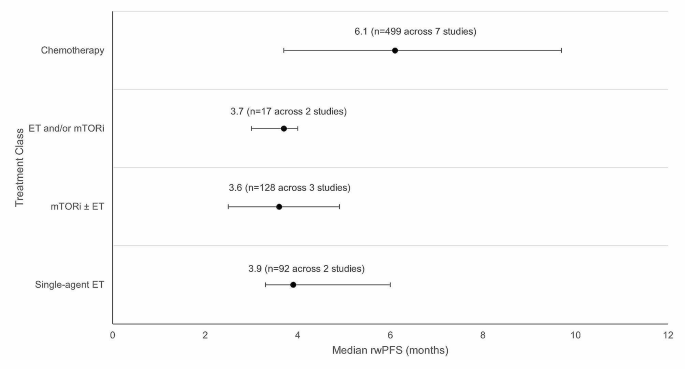

Weighted average median rwPFS was calculated for 2 L treatments recommended by both ESMO and NCCN guidelines (Fig. 3 ). The weighted average median rwPFS for single-agent ET was 3.9 months ( n = 92 total patients) and was derived using data from two studies reporting median rwPFS values of 3.3 months ( n = 70) [ 38 ] and 6.0 months ( n = 22) [ 40 ]. For one study ( n = 7) that reported outcomes for single agent ET, median rwPFS was not reached during the follow-up period; as such, this study was excluded from the weighted average median rwPFS calculation [ 49 ].

The weighted average median rwPFS for mTORi ± ET was 3.6 months ( n = 128 total patients) and was derived based on data from 3 studies with median rwPFS ranging from 2.5 months ( n = 4) [ 49 ] to 4.9 months ( n = 25) [ 54 ] (Fig. 3 ). For patients who received a mix of ET and/or mTORi but could not be classified into the single-agent ET or mTORi ± ET treatment classes, the weighted average median rwPFS was calculated to be 3.7 months ( n = 17 total patients). This was calculated based on data from two studies reporting median rwPFS values of 3.0 months ( n = 5) [ 46 ] and 4.0 months ( n = 12) [ 49 ]. Notably, one study of patients receiving ET and/or everolimus reported a median rwPFS duration of 3.0 months; however, this study was excluded from the weighted average median rwPFS calculation for the ET and/or mTORi class as the sample size was not reported [ 53 ].

The weighted average median rwPFS for chemotherapy was 6.1 months ( n = 499 total patients), calculated using data from 7 studies reporting median rwPFS values ranging from 3.7 months ( n = 249) [ 38 ] to 9.7 months ( n = 121) [ 45 ] (Fig. 3 ). One study with a median rwPFS duration of 5.6 months was not included in the weighted average median rwPFS calculation as the study did not report the sample size [ 53 ]. A second study was excluded from the calculation since the reported median rwPFS was not reached during the study period ( n = 7) [ 41 ].

Although 2 L CDK4/6i ± ET rechallenge lacks sufficient information to support recommendation by ESMO and NCCN guidelines, the limited data currently available for this treatment have shown promising results. Briefly, two studies reported median rwPFS for CDK4/6i ± ET with values of 8.3 months ( n = 302) [ 38 ] and 17.3 months ( n = 165) (Table 2 ) [ 39 ]. The remaining median rwPFS studies reported data for patients classified as “Other” (Table S5 ). The “Other” category included median rwPFS outcomes from seven studies, and included a myriad of treatments (e.g., ET, mTOR + ET, chemotherapy, CDK4/6i + ET, alpelisib + fulvestrant, chidamide + ET) for which disaggregated median rwPFS values were not reported.

Overall survival

Median OS for 2 L treatment was reported in only three studies (Table 2 ) [ 38 , 42 , 43 ]. Across the three studies, the 2 L median OS ranged from 5.2 months ( n = 3) [ 43 ] to 35.7 months ( n = 302) [ 38 ]. Due to the lack of OS data in most of the studies, weighted averages could not be calculated. No median OS data was reported for the single-agent ET treatment class whereas two studies reported median OS for the mTORi ± ET treatment class, ranging from 5.2 months ( n = 3) [ 43 ] to 21.8 months ( n = 54) [ 42 ]. One study reported 2 L median OS of 24.8 months for a single patient treated with chemotherapy [ 43 ]. The median OS data in the CDK4/6i ± ET rechallenge group was 35.7 months ( n = 302) [ 38 ].

Patient mortality was reported in three studies [ 43 , 44 , 45 ]. No studies reported mortality for the single-agent ET treatment class and only one study reported this outcome for the mTORi ± ET treatment class, where 100% of patients died ( n = 3) as a result of rapid disease progression [ 43 ]. For the chemotherapy class, one study reported mortality for one patient receiving 2 L capecitabine [ 43 ]. An additional study reported eight deaths (21.7%) following 1 L CDK4/6i treatment; however, this study did not disclose the 2 L treatments administered to these patients [ 44 ].

Other clinical endpoints

The studies included limited information on additional clinical endpoints; two studies reported on time-to-discontinuation (TTD), two reported on duration of response (DOR), and one each on time-to-next-treatment (TTNT), time-to-progression (TTP), objective response rate (ORR), clinical benefit rate (CBR), and stable disease (Tables 2 and Table S5 ).

Safety, tolerability, and patient-reported outcomes

Safety and tolerability data were reported in two studies [ 40 , 45 ]. One study investigating 2 L administration of the chemotherapy agent eribulin mesylate reported 27 patients (22.3%) with neutropenia, 3 patients (2.5%) with febrile neutropenia, 10 patients (8.3%) with peripheral neuropathy, and 14 patients (11.6%) with diarrhea [ 45 ]. Of these, neutropenia of grade 3–4 severity occurred in 9 patients (33.3%) [ 45 ]. A total of 55 patients (45.5%) discontinued eribulin mesylate treatment; 1 patient (0.83%) discontinued treatment due to adverse events [ 45 ]. Another study reported that 5 out of the 22 patients receiving the mTORi everolimus combined with ET in 2 L (22.7%) discontinued treatment due to toxicity [ 40 ]. PROs were not reported in any of the studies included in the SLR.

The objective of this study was to summarize the existing RWE on the effectiveness and safety of therapies for patients with HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC after 1 L CDK4/6i treatment. We identified 18 unique studies reporting specifically on 2 L treatment regimens after 1 L CDK4/6i treatment. The weighted average median rwPFS for NCCN- and ESMO- guideline recommended 2 L treatments ranged from 3.6 to 3.9 months for ET-based treatments and was 6.1 months when including chemotherapy-based regimens. Treatment selection following 1 L CDK4/6i therapy remains challenging primarily due to the suboptimal effectiveness or significant toxicities (e.g., chemotherapy) associated with currently available options [ 56 ]. These results highlight that currently available 2 L treatments for patients with HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC who have received 1 L CDK4/6i are suboptimal, as evidenced by the brief median rwPFS duration associated with ET-based treatments, or notable side effects and toxicity linked to chemotherapy. This conclusion is aligned with a recent review highlighting the limited effectiveness of treatment options for HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC patients post-CDK4/6i treatment [ 56 , 57 ]. Registrational trials which have also shed light on the short median PFS of 2–3 months achieved by ET (i.e., fulvestrant) after 1 L CDK4/6i therapy emphasize the need to develop improved treatment strategies aimed at prolonging the duration of effective ET-based treatment [ 56 ].

The results of this review reveal a paucity of additional real-world effectiveness and safety evidence after 1 L CDK4/6i treatment in HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC. OS and DOR were only reported in two studies while other clinical endpoints (i.e., TTD, TTNT, TTP, ORR, CBR, and stable disease) were only reported in one study each. Similarly, safety and tolerability data were only reported in two studies each, and PROs were not reported in any study. This hindered our ability to provide a comprehensive assessment of real-world treatment effectiveness and safety following 1 L CDK4/6i treatment. The limited evidence may be due to the relatively short period of time that has elapsed since CDK4/6i first received US FDA approval for 1 L treatment of HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC (2015) [ 35 ]. As such, almost half of our evidence was informed by conference abstracts. Similarly, no real-world studies were identified in our review that reported outcomes for treatments in the third- or later-lines of therapy after 1 L CDK4/6i treatment. The lack of data in this patient population highlights a significant gap which limits our understanding of the effectiveness and safety for patients receiving later lines of therapy. As more patients receive CDK4/6i therapy in the 1 L setting, the number of patients requiring subsequent lines of therapy will continue to grow. Addressing this data gap over time will be critical to improve outcomes for patients with HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC following 1 L CDK4/6i therapy.

There are several strengths of this study, including adherence to the guidelines outlined in the Cochrane Handbook to ensure a standardized and reliable approach to the SLR [ 58 ] and reporting of the SLR following PRISMA guidelines to ensure transparency and reproducibility [ 59 ]. Furthermore, the inclusion of only RWE studies allowed us to assess the effectiveness of current standard of care treatments outside of a controlled environment and enabled us to identify an unmet need in this patient population.

This study had some notable limitations, including the lack of safety and additional effectiveness outcomes reported. In addition, the dearth of studies reporting PROs is a limitation, as PROs provide valuable insight into the patient experience and are an important aspect of assessing the impact of 2 L treatments on patients’ quality of life. The studies included in this review also lacked consistent reporting of clinical characteristics (e.g., menopausal status, sites of metastasis, prior surgery) making it challenging to draw comprehensive conclusions or comparisons based on these factors across the studies. Taken together, there exists an important gap in our understanding of the long-term management of patients with HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC. Additionally, the effectiveness results reported in our evidence base were informed by small sample sizes; many of the included studies reported median rwPFS based on less than 30 patients [ 39 , 40 , 41 , 46 , 49 , 51 , 60 ], with two studies not reporting the sample size at all [ 47 , 53 ]. This may impact the generalizability and robustness of the results. Relatedly, the SLR database search was conducted in December 2022; as such, novel agents (e.g., elacestrant and capivasertib + fulvestrant) that have since received FDA approval for the treatment of HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC may impact current 2 L rwPFS outcomes [ 61 , 62 ]. Finally, relative to the number of peer-reviewed full-text articles, this SLR identified eight abstracts and one poster presentation, comprising half (50%) of the included unique studies. As conference abstracts are inherently limited by how much content that can be described due to word limit constraints, this likely had implications on the present synthesis whereby we identified a dearth of real-world effectiveness outcomes in patients with HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC treated with 1 L CDK4/6i therapy.

Future research in this area should aim to address the limitations of the current literature and provide a more comprehensive understanding of optimal sequencing of effective and safe treatment for patients following 1 L CDK4/6i therapy. Specifically, future studies should strive to report robust data related to effectiveness, safety, and PROs for patients receiving 2 L treatment after 1 L CDK4/6i therapy. Future studies should also aim to understand the mechanism underlying CDK4/6i resistance. Addressing these gaps in knowledge may improve the long-term real-world management of patients with HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC. A future update of this synthesis may serve to capture a wider breadth of full-text, peer-reviewed articles to gain a more robust understanding of the safety, effectiveness, and real-world treatment patterns for patients with HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC. This SLR underscores the necessity for ongoing investigation and the development of innovative therapeutic approaches to address these gaps and improve patient outcomes.

This SLR qualitatively summarized the existing real-world effectiveness data for patients with HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC after 1 L CDK4/6i treatment. Results of this study highlight the limited available data and the suboptimal effectiveness of treatments employed in the 2 L setting and underscore the unmet need in this patient population. Additional studies reporting effectiveness and safety outcomes, in addition to PROs, for this patient population are necessary and should be the focus of future research.

PRISMA flow diagram. *Two included conference abstracts reported the same information as already included full-text reports, hence both conference abstracts were not identified as unique. Abbreviations: 1 L = first-line; AACR = American Association of Cancer Research; ASCO = American Society of Clinical Oncology; CDK4/6i = cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor; ESMO = European Society for Medical Oncology; ISPOR = Professional Society for Health Economics and Outcomes Research; n = number of studies; NMA = network meta-analysis; pts = participants; SABCS = San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; SLR = systematic literature review.

Number of studies reporting effectiveness outcomes exclusively for each treatment class. *Studies that lack sufficient information on effectiveness outcomes to classify based on the treatment classes outlined in the legend above. Abbreviations: CDK4/6i = cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor; ET = endocrine therapy; mTORi = mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor.

Weighted average median rwPFS for 2 L treatments (recommended in ESMO/NCCN guidelines) after 1 L CDK4/6i treatment. Circular dot represents weighted average median across studies. Horizontal bars represent the range of values reported in these studies. Abbreviations: CDK4/6i = cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor; ESMO = European Society for Medical Oncology; ET = endocrine therapy, mTORi = mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor; n = number of patients; NCCN = National Comprehensive Cancer Network; rwPFS = real-world progression-free survival.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files]. This study is registered with PROSPERO (CRD42023383914).

Abbreviations

Second-line

Second-line treatment setting and beyond

American Association of Cancer Research

Aromatase inhibitor

American Society of Clinical Oncology

- Breast cancer

breast cancer gene/partner and localizer of BRCA2 positive

Clinical benefit rate

Cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor

Complete response

Duration of response

European Society for Medical Oncology

Food and Drug Administration

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 negative

Hormone receptor

Hormone receptor positive

Professional Society for Health Economics and Outcomes Research

Locally advanced breast cancer

Metastatic breast cancer

Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online

Medical subject headings

Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor

National Comprehensive Cancer Network

Newcastle Ottawa Scale

Objective response rate

Poly-ADP ribose polymerase inhibitor

Progression-free survival

Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome, Study Design

Partial response

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Literature Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Patient-reported outcomes

- Real-world evidence

San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium

- Systematic literature review

Time-to-discontinuation

Time-to-next-treatment

Time-to-progression

United States

Łukasiewicz S, Czeczelewski M, Forma A, Baj J, Sitarz R, Stanisławek A, Breast, Cancer—Epidemiology. Risk factors, classification, prognostic markers, and current treatment Strategies—An. Updated Rev Cancers. 2021;13(17):4287.

Google Scholar

World Health Organization (WHO). Breast Cancer Facts Sheet [updated July 12 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/breast-cancer .

Arnold M, Morgan E, Rumgay H, Mafra A, Singh D, Laversanne M, et al. Current and future burden of breast cancer: global statistics for 2020 and 2040. Breast. 2022;66:15–23.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Wilkinson L, Gathani T. Understanding breast cancer as a global health concern. Br J Radiol. 2022;95(1130):20211033.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Giaquinto AN, Sung H, Miller KD, Kramer JL, Newman LA, Minihan A et al. Breast Cancer Statistics, 2022. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2022;72(6):524– 41.

National Cancer Institute (NIH). Cancer Stat Facts: Female Breast Cancer [updated 2020. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html .

American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Breast Cancer [ https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer/about/how-common-is-breast-cancer.html .

Zagami P, Carey LA. Triple negative breast cancer: pitfalls and progress. npj Breast Cancer. 2022;8(1):95.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Matutino A, Joy AA, Brezden-Masley C, Chia S, Verma S. Hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer: redrawing the lines. Curr Oncol. 2018;25(Suppl 1):S131–41.

Lloyd MR, Wander SA, Hamilton E, Razavi P, Bardia A. Next-generation selective estrogen receptor degraders and other novel endocrine therapies for management of metastatic hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: current and emerging role. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2022;14:17588359221113694.

Cardoso F, Senkus E, Costa A, Papadopoulos E, Aapro M, André F, et al. 4th ESO-ESMO International Consensus guidelines for advanced breast Cancer (ABC 4)†. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(8):1634–57.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

US Food Drug Administration. Palbociclib (Ibrance) 2017 [updated March 31, 2017. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/palbociclib-ibrance .

US Food Drug Administration. FDA expands ribociclib indication in HR-positive, HER2-negative advanced or metastatic breast cancer 2018 [updated July 18. 2018. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-expands-ribociclib-indication-hr-positive-her2-negative-advanced-or-metastatic-breast-cancer .

US Food Drug Administration. FDA approves abemaciclib for HR positive, HER2-negative breast cancer 2017 [updated Sept 28. 2017. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-abemaciclib-hr-positive-her2-negative-breast-cancer .

NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®). Breast Cancer 2022 [ https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf .

Gennari A, André F, Barrios CH, Cortés J, de Azambuja E, DeMichele A, et al. ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for the diagnosis, staging and treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(12):1475–95.

Beaver JA, Amiri-Kordestani L, Charlab R, Chen W, Palmby T, Tilley A, et al. FDA approval: Palbociclib for the Treatment of Postmenopausal Patients with estrogen Receptor-Positive, HER2-Negative metastatic breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(21):4760–6.

US Food Drug Administration. Ribociclib (Kisqali) [ https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/ribociclib-kisqali#:~:text=On%20March%2013%2C%202017%2C%20the,hormone%20receptor%20(HR)%2Dpositive%2C .

US Food Drug Administration. FDA approves new treatment for certain advanced or metastatic breast cancers [ https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-treatment-certain-advanced-or-metastatic-breast-cancers .

US Food Drug Administration. FDA expands ribociclib indication in HR-positive, HER2-negative advanced or metastatic breast cancer. 2018 [ https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-expands-ribociclib-indication-hr-positive-her2-negative-advanced-or-metastatic-breast-cancer .

US Food Drug Administration. FDA approves abemaciclib as initial therapy for HR-positive, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer [ https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-abemaciclib-initial-therapy-hr-positive-her2-negative-metastatic-breast-cancer .

Turner NC, Slamon DJ, Ro J, Bondarenko I, Im S-A, Masuda N, et al. Overall survival with Palbociclib and fulvestrant in advanced breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(20):1926–36.

Slamon DJ, Neven P, Chia S, Fasching PA, De Laurentiis M, Im SA, et al. Phase III randomized study of Ribociclib and Fulvestrant in hormone Receptor-Positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-Negative advanced breast Cancer: MONALEESA-3. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(24):2465–72.

Goetz MP, Toi M, Campone M, Sohn J, Paluch-Shimon S, Huober J, et al. MONARCH 3: Abemaciclib as initial therapy for advanced breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(32):3638–46.

Gopalan PK, Villegas AG, Cao C, Pinder-Schenck M, Chiappori A, Hou W, et al. CDK4/6 inhibition stabilizes disease in patients with p16-null non-small cell lung cancer and is synergistic with mTOR inhibition. Oncotarget. 2018;9(100):37352–66.

Watt AC, Goel S. Cellular mechanisms underlying response and resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors in the treatment of hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2022;24(1):17.

Goetz M. MONARCH 3: final overall survival results of abemaciclib plus a nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor as first-line therapy for HR+, HER2- advanced breast cancer. SABCS; 2023.

Munzone E, Pagan E, Bagnardi V, Montagna E, Cancello G, Dellapasqua S, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of post-progression outcomes in ER+/HER2– metastatic breast cancer after CDK4/6 inhibitors within randomized clinical trials. ESMO Open. 2021;6(6):100332.

Gennari A, André F, Barrios CH, Cortés J, de Azambuja E, DeMichele A, et al. ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for the diagnosis, staging and treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Annals of Oncology. 2021;32(12):1475-95.

European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO). ESMO Metastatic Breast Cancer Living Guideline: ER-positive HER2-negative Breast Cancer [updated May 2023. https://www.esmo.org/living-guidelines/esmo-metastatic-breast-cancer-living-guideline/er-positive-her2-negative-breast-cancer .

Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Welch PM VA, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.2 (updated February 2021). www.training.cochrane.org/handbook : Cochrane; 2021.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 2021;18(3):e1003583.

McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40–6.

Fraser C, Murray A, Burr J. Identifying observational studies of surgical interventions in MEDLINE and EMBASE. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6(1):41.

US Food Drug Administration. Palbociclib (Ibrance). Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; 2017.

Book Google Scholar

GA Wells BS, D O’Connell J, Peterson V, Welch M, Losos PT. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses [ https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp .

Lo CK-L, Mertz D, Loeb M. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale: comparing reviewers’ to authors’ assessments. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14(1):45.

Martin JM, Handorf EA, Montero AJ, Goldstein LJ. Systemic therapies following progression on first-line CDK4/6-inhibitor treatment: analysis of real-world data. Oncologist. 2022;27(6):441–6.

Kalinsky KM, Kruse M, Smyth EN, Guimaraes CM, Gautam S, Nisbett AR et al. Abstract P1-18-37: Treatment patterns and outcomes associated with sequential and non-sequential use of CDK4 and 6i for HR+, HER2- MBC in the real world. Cancer Research. 2022;82(4_Supplement):P1-18-37-P1-18-37.

Choong GM, Liddell S, Ferre RAL, O’Sullivan CC, Ruddy KJ, Haddad TC, et al. Clinical management of metastatic hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer (MBC) after CDK 4/6 inhibitors: a retrospective single-institution study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2022;196(1):229–37.

Xi J, Oza A, Thomas S, Ademuyiwa F, Weilbaecher K, Suresh R, et al. Retrospective Analysis of Treatment Patterns and effectiveness of Palbociclib and subsequent regimens in metastatic breast Cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17(2):141–7.

Rozenblit M, Mun S, Soulos P, Adelson K, Pusztai L, Mougalian S. Patterns of treatment with everolimus exemestane in hormone receptor-positive HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer in the era of targeted therapy. Breast Cancer Res. 2021;23(1):14.

Bashour SI, Doostan I, Keyomarsi K, Valero V, Ueno NT, Brown PH, et al. Rapid breast Cancer Disease Progression following cyclin dependent kinase 4 and 6 inhibitor discontinuation. J Cancer. 2017;8(11):2004–9.

Giridhar KV, Choong GM, Leon-Ferre R, O’Sullivan CC, Ruddy K, Haddad T, et al. Abstract P6-18-09: clinical management of metastatic breast cancer (MBC) after CDK 4/6 inhibitors: a retrospective single-institution study. Cancer Res. 2019;79:P6–18.

Article Google Scholar

Mougalian SS, Feinberg BA, Wang E, Alexis K, Chatterjee D, Knoth RL, et al. Observational study of clinical outcomes of eribulin mesylate in metastatic breast cancer after cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor therapy. Future Oncol. 2019;15(34):3935–44.

Moscetti LML, Riggi L, Sperduti I, Piacentini FOC, Toss A, Barbieri E, Cortesi L, Canino FMA, Zoppoli G, Frassoldati A, Schirone A, Dominici MECF. SEQUENCE OF TREATMENTS AFTER CDK4/6 THERAPY IN ADVANCED BREAST CANCER (ABC), A GOIRC MULTICENTER RETRO/ PROSPECTIVE STUDY. PRELIMINARY RESULTS IN THE RETROSPECTIVE SERIES OF 116 PATIENTS. Tumori. 2022;108(4S):80.

Menichetti AZE, Giorgi CA, Bottosso M, Leporati R, Giarratano T, Barbieri C, Ligorio F, Mioranza E, Miglietta F, Lobefaro R, Faggioni G, Falci C, Vernaci G, Di Liso E, Girardi F, Griguolo G, Vernieri C, Guarneri V, Dieci MV. CDK 4/6 INHIBITORS FOR METASTATIC BREAST CANCER: A MULTICENTER REALWORLD STUDY. Tumori. 2022;108(4S):70.

Marschner NW, Harbeck N, Thill M, Stickeler E, Zaiss M, Nusch A, et al. 232P Second-line therapies of patients with early progression under CDK4/6-inhibitor in first-line– data from the registry platform OPAL. Annals of Oncology. 2022;33:S643-S4

Gousis C, Lowe KMH, Kapiris M. V. Angelis. Beyond First Line CDK4/6 Inhibitors (CDK4/6i) and Aromatase Inhibitors (AI) in Patients with Oestrogen Receptor Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer (ERD MBC): The Guy’s Cancer Centre Experience. Clinical Oncology2022. p. e178.

Endo Y, Yoshimura A, Sawaki M, Hattori M, Kotani H, Kataoka A, et al. Time to chemotherapy for patients with estrogen receptor-positive breast Cancer and cyclin-dependent kinase 4 and 6 inhibitor use. J Breast Cancer. 2022;25(4):296–306.

Li Y, Li W, Gong C, Zheng Y, Ouyang Q, Xie N, et al. A multicenter analysis of treatment patterns and clinical outcomes of subsequent therapies after progression on palbociclib in HR+/HER2- metastatic breast cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2021;13:17588359211022890.

Amaro CP, Batra A, Lupichuk S. First-line treatment with a cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor plus an aromatase inhibitor for metastatic breast Cancer in Alberta. Curr Oncol. 2021;28(3):2270–80.

Crocetti SPM, Tassone L, Marcantognini G, Bastianelli L, Della Mora A, Merloni F, Cantini L, Scortichini L, Agostinelli V, Ballatore Z, Savini A, Maccaroni E. Berardi R. What is the best therapeutic sequence for ER-Positive/HER2- Negative metastatic breast cancer in the era of CDK4/6 inhibitors? A single center experience. Tumori. 2020;106(2S).

Nichetti F, Marra A, Giorgi CA, Randon G, Scagnoli S, De Angelis C, et al. 337P Efficacy of everolimus plus exemestane in CDK 4/6 inhibitors-pretreated or naïve HR-positive/HER2-negative breast cancer patients: A secondary analysis of the EVERMET study. Annals of Oncology. 2020;31:S382

Luhn P, O’Hear C, Ton T, Sanglier T, Hsieh A, Oliveri D, et al. Abstract P4-13-08: time to treatment discontinuation of second-line fulvestrant monotherapy for HR+/HER2– metastatic breast cancer in the real-world setting. Cancer Res. 2019;79(4Supplement):P4–13.

Mittal A, Molto Valiente C, Tamimi F, Schlam I, Sammons S, Tolaney SM et al. Filling the gap after CDK4/6 inhibitors: Novel Endocrine and Biologic Treatment options for metastatic hormone receptor positive breast Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(7).

Ashai N, Swain SM. Post-CDK 4/6 inhibitor therapy: current agents and novel targets. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(6).

Higgins JPTTJ, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.3 (updated February 2022). www.training.cochrane.org/handbook : Cochrane; 2022.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

Serdar CC, Cihan M, Yücel D, Serdar MA. Sample size, power and effect size revisited: simplified and practical approaches in pre-clinical, clinical and laboratory studies. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2021;31(1):010502.

US Food Drug Administration. FDA approves elacestrant for ER-positive, HER2-negative, ESR1-mutated advanced or metastatic breast cancer [updated January 27 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-elacestrant-er-positive-her2-negative-esr1-mutated-advanced-or-metastatic-breast-cancer .

US Food Drug Administration. FDA approves capivasertib with fulvestrant for breast cancer [updated November 16 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-capivasertib-fulvestrant-breast-cancer .

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Joanna Bielecki who developed, conducted, and documented the database searches.

This study was funded by Pfizer Inc. (New York, NY, USA) and Arvinas (New Haven, CT, USA).

Author information

Sarah Kane, Belal Howidi, Bao-Ngoc Nguyen and Imtiaz A. Samjoo contributed equally to this work.

Authors and Affiliations

Pfizer, 10017, New York, NY, USA

Veronique Lambert & Yan Wu

EVERSANA, Burlington, ON, Canada

Sarah Kane, Belal Howidi, Bao-Ngoc Nguyen & Imtiaz A. Samjoo

Arvinas, 06511, New Haven, CT, USA

David Chandiwana & Michelle Edwards

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

VL, IAS, SK, BH, BN, DC, YW, and ME participated in the conception and design of the study. IAS, SK, BH and BN contributed to the literature review, data collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data. VL, IAS, SK, BH, BN, DC, YW, and ME contributed to the interpretation of the data and critically reviewed for the importance of intellectual content for the work. VL, IAS, SK, BH, BN, DC, YW, and ME were responsible for drafting or reviewing the manuscript and for providing final approval. VL, IAS, SK, BH, BN, DC, YW, and ME meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Imtiaz A. Samjoo .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors of this manuscript declare that the research presented was funded by Pfizer Inc. and Arvinas. While the support from Pfizer Inc. and Arvinas was instrumental in facilitating this research, the authors affirm that their interpretation of the data and the content of this manuscript were conducted independently and without bias to maintain the transparency and integrity of the research. IAS, SK, BH, and BN are employees of EVERSANA, Canada, which was a paid consultant to Pfizer in connection with the development of this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.