An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- PLoS Comput Biol

- v.17(12); 2021 Dec

Ten simple rules for effective presentation slides

Kristen m. naegle.

Biomedical Engineering and the Center for Public Health Genomics, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia, United States of America

Introduction

The “presentation slide” is the building block of all academic presentations, whether they are journal clubs, thesis committee meetings, short conference talks, or hour-long seminars. A slide is a single page projected on a screen, usually built on the premise of a title, body, and figures or tables and includes both what is shown and what is spoken about that slide. Multiple slides are strung together to tell the larger story of the presentation. While there have been excellent 10 simple rules on giving entire presentations [ 1 , 2 ], there was an absence in the fine details of how to design a slide for optimal effect—such as the design elements that allow slides to convey meaningful information, to keep the audience engaged and informed, and to deliver the information intended and in the time frame allowed. As all research presentations seek to teach, effective slide design borrows from the same principles as effective teaching, including the consideration of cognitive processing your audience is relying on to organize, process, and retain information. This is written for anyone who needs to prepare slides from any length scale and for most purposes of conveying research to broad audiences. The rules are broken into 3 primary areas. Rules 1 to 5 are about optimizing the scope of each slide. Rules 6 to 8 are about principles around designing elements of the slide. Rules 9 to 10 are about preparing for your presentation, with the slides as the central focus of that preparation.

Rule 1: Include only one idea per slide

Each slide should have one central objective to deliver—the main idea or question [ 3 – 5 ]. Often, this means breaking complex ideas down into manageable pieces (see Fig 1 , where “background” information has been split into 2 key concepts). In another example, if you are presenting a complex computational approach in a large flow diagram, introduce it in smaller units, building it up until you finish with the entire diagram. The progressive buildup of complex information means that audiences are prepared to understand the whole picture, once you have dedicated time to each of the parts. You can accomplish the buildup of components in several ways—for example, using presentation software to cover/uncover information. Personally, I choose to create separate slides for each piece of information content I introduce—where the final slide has the entire diagram, and I use cropping or a cover on duplicated slides that come before to hide what I’m not yet ready to include. I use this method in order to ensure that each slide in my deck truly presents one specific idea (the new content) and the amount of the new information on that slide can be described in 1 minute (Rule 2), but it comes with the trade-off—a change to the format of one of the slides in the series often means changes to all slides.

Top left: A background slide that describes the background material on a project from my lab. The slide was created using a PowerPoint Design Template, which had to be modified to increase default text sizes for this figure (i.e., the default text sizes are even worse than shown here). Bottom row: The 2 new slides that break up the content into 2 explicit ideas about the background, using a central graphic. In the first slide, the graphic is an explicit example of the SH2 domain of PI3-kinase interacting with a phosphorylation site (Y754) on the PDGFR to describe the important details of what an SH2 domain and phosphotyrosine ligand are and how they interact. I use that same graphic in the second slide to generalize all binding events and include redundant text to drive home the central message (a lot of possible interactions might occur in the human proteome, more than we can currently measure). Top right highlights which rules were used to move from the original slide to the new slide. Specific changes as highlighted by Rule 7 include increasing contrast by changing the background color, increasing font size, changing to sans serif fonts, and removing all capital text and underlining (using bold to draw attention). PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor.

Rule 2: Spend only 1 minute per slide

When you present your slide in the talk, it should take 1 minute or less to discuss. This rule is really helpful for planning purposes—a 20-minute presentation should have somewhere around 20 slides. Also, frequently giving your audience new information to feast on helps keep them engaged. During practice, if you find yourself spending more than a minute on a slide, there’s too much for that one slide—it’s time to break up the content into multiple slides or even remove information that is not wholly central to the story you are trying to tell. Reduce, reduce, reduce, until you get to a single message, clearly described, which takes less than 1 minute to present.

Rule 3: Make use of your heading

When each slide conveys only one message, use the heading of that slide to write exactly the message you are trying to deliver. Instead of titling the slide “Results,” try “CTNND1 is central to metastasis” or “False-positive rates are highly sample specific.” Use this landmark signpost to ensure that all the content on that slide is related exactly to the heading and only the heading. Think of the slide heading as the introductory or concluding sentence of a paragraph and the slide content the rest of the paragraph that supports the main point of the paragraph. An audience member should be able to follow along with you in the “paragraph” and come to the same conclusion sentence as your header at the end of the slide.

Rule 4: Include only essential points

While you are speaking, audience members’ eyes and minds will be wandering over your slide. If you have a comment, detail, or figure on a slide, have a plan to explicitly identify and talk about it. If you don’t think it’s important enough to spend time on, then don’t have it on your slide. This is especially important when faculty are present. I often tell students that thesis committee members are like cats: If you put a shiny bauble in front of them, they’ll go after it. Be sure to only put the shiny baubles on slides that you want them to focus on. Putting together a thesis meeting for only faculty is really an exercise in herding cats (if you have cats, you know this is no easy feat). Clear and concise slide design will go a long way in helping you corral those easily distracted faculty members.

Rule 5: Give credit, where credit is due

An exception to Rule 4 is to include proper citations or references to work on your slide. When adding citations, names of other researchers, or other types of credit, use a consistent style and method for adding this information to your slides. Your audience will then be able to easily partition this information from the other content. A common mistake people make is to think “I’ll add that reference later,” but I highly recommend you put the proper reference on the slide at the time you make it, before you forget where it came from. Finally, in certain kinds of presentations, credits can make it clear who did the work. For the faculty members heading labs, it is an effective way to connect your audience with the personnel in the lab who did the work, which is a great career booster for that person. For graduate students, it is an effective way to delineate your contribution to the work, especially in meetings where the goal is to establish your credentials for meeting the rigors of a PhD checkpoint.

Rule 6: Use graphics effectively

As a rule, you should almost never have slides that only contain text. Build your slides around good visualizations. It is a visual presentation after all, and as they say, a picture is worth a thousand words. However, on the flip side, don’t muddy the point of the slide by putting too many complex graphics on a single slide. A multipanel figure that you might include in a manuscript should often be broken into 1 panel per slide (see Rule 1 ). One way to ensure that you use the graphics effectively is to make a point to introduce the figure and its elements to the audience verbally, especially for data figures. For example, you might say the following: “This graph here shows the measured false-positive rate for an experiment and each point is a replicate of the experiment, the graph demonstrates …” If you have put too much on one slide to present in 1 minute (see Rule 2 ), then the complexity or number of the visualizations is too much for just one slide.

Rule 7: Design to avoid cognitive overload

The type of slide elements, the number of them, and how you present them all impact the ability for the audience to intake, organize, and remember the content. For example, a frequent mistake in slide design is to include full sentences, but reading and verbal processing use the same cognitive channels—therefore, an audience member can either read the slide, listen to you, or do some part of both (each poorly), as a result of cognitive overload [ 4 ]. The visual channel is separate, allowing images/videos to be processed with auditory information without cognitive overload [ 6 ] (Rule 6). As presentations are an exercise in listening, and not reading, do what you can to optimize the ability of the audience to listen. Use words sparingly as “guide posts” to you and the audience about major points of the slide. In fact, you can add short text fragments, redundant with the verbal component of the presentation, which has been shown to improve retention [ 7 ] (see Fig 1 for an example of redundant text that avoids cognitive overload). Be careful in the selection of a slide template to minimize accidentally adding elements that the audience must process, but are unimportant. David JP Phillips argues (and effectively demonstrates in his TEDx talk [ 5 ]) that the human brain can easily interpret 6 elements and more than that requires a 500% increase in human cognition load—so keep the total number of elements on the slide to 6 or less. Finally, in addition to the use of short text, white space, and the effective use of graphics/images, you can improve ease of cognitive processing further by considering color choices and font type and size. Here are a few suggestions for improving the experience for your audience, highlighting the importance of these elements for some specific groups:

- Use high contrast colors and simple backgrounds with low to no color—for persons with dyslexia or visual impairment.

- Use sans serif fonts and large font sizes (including figure legends), avoid italics, underlining (use bold font instead for emphasis), and all capital letters—for persons with dyslexia or visual impairment [ 8 ].

- Use color combinations and palettes that can be understood by those with different forms of color blindness [ 9 ]. There are excellent tools available to identify colors to use and ways to simulate your presentation or figures as they might be seen by a person with color blindness (easily found by a web search).

- In this increasing world of virtual presentation tools, consider practicing your talk with a closed captioning system capture your words. Use this to identify how to improve your speaking pace, volume, and annunciation to improve understanding by all members of your audience, but especially those with a hearing impairment.

Rule 8: Design the slide so that a distracted person gets the main takeaway

It is very difficult to stay focused on a presentation, especially if it is long or if it is part of a longer series of talks at a conference. Audience members may get distracted by an important email, or they may start dreaming of lunch. So, it’s important to look at your slide and ask “If they heard nothing I said, will they understand the key concept of this slide?” The other rules are set up to help with this, including clarity of the single point of the slide (Rule 1), titling it with a major conclusion (Rule 3), and the use of figures (Rule 6) and short text redundant to your verbal description (Rule 7). However, with each slide, step back and ask whether its main conclusion is conveyed, even if someone didn’t hear your accompanying dialog. Importantly, ask if the information on the slide is at the right level of abstraction. For example, do you have too many details about the experiment, which hides the conclusion of the experiment (i.e., breaking Rule 1)? If you are worried about not having enough details, keep a slide at the end of your slide deck (after your conclusions and acknowledgments) with the more detailed information that you can refer to during a question and answer period.

Rule 9: Iteratively improve slide design through practice

Well-designed slides that follow the first 8 rules are intended to help you deliver the message you intend and in the amount of time you intend to deliver it in. The best way to ensure that you nailed slide design for your presentation is to practice, typically a lot. The most important aspects of practicing a new presentation, with an eye toward slide design, are the following 2 key points: (1) practice to ensure that you hit, each time through, the most important points (for example, the text guide posts you left yourself and the title of the slide); and (2) practice to ensure that as you conclude the end of one slide, it leads directly to the next slide. Slide transitions, what you say as you end one slide and begin the next, are important to keeping the flow of the “story.” Practice is when I discover that the order of my presentation is poor or that I left myself too few guideposts to remember what was coming next. Additionally, during practice, the most frequent things I have to improve relate to Rule 2 (the slide takes too long to present, usually because I broke Rule 1, and I’m delivering too much information for one slide), Rule 4 (I have a nonessential detail on the slide), and Rule 5 (I forgot to give a key reference). The very best type of practice is in front of an audience (for example, your lab or peers), where, with fresh perspectives, they can help you identify places for improving slide content, design, and connections across the entirety of your talk.

Rule 10: Design to mitigate the impact of technical disasters

The real presentation almost never goes as we planned in our heads or during our practice. Maybe the speaker before you went over time and now you need to adjust. Maybe the computer the organizer is having you use won’t show your video. Maybe your internet is poor on the day you are giving a virtual presentation at a conference. Technical problems are routinely part of the practice of sharing your work through presentations. Hence, you can design your slides to limit the impact certain kinds of technical disasters create and also prepare alternate approaches. Here are just a few examples of the preparation you can do that will take you a long way toward avoiding a complete fiasco:

- Save your presentation as a PDF—if the version of Keynote or PowerPoint on a host computer cause issues, you still have a functional copy that has a higher guarantee of compatibility.

- In using videos, create a backup slide with screen shots of key results. For example, if I have a video of cell migration, I’ll be sure to have a copy of the start and end of the video, in case the video doesn’t play. Even if the video worked, you can pause on this backup slide and take the time to highlight the key results in words if someone could not see or understand the video.

- Avoid animations, such as figures or text that flash/fly-in/etc. Surveys suggest that no one likes movement in presentations [ 3 , 4 ]. There is likely a cognitive underpinning to the almost universal distaste of pointless animations that relates to the idea proposed by Kosslyn and colleagues that animations are salient perceptual units that captures direct attention [ 4 ]. Although perceptual salience can be used to draw attention to and improve retention of specific points, if you use this approach for unnecessary/unimportant things (like animation of your bullet point text, fly-ins of figures, etc.), then you will distract your audience from the important content. Finally, animations cause additional processing burdens for people with visual impairments [ 10 ] and create opportunities for technical disasters if the software on the host system is not compatible with your planned animation.

Conclusions

These rules are just a start in creating more engaging presentations that increase audience retention of your material. However, there are wonderful resources on continuing on the journey of becoming an amazing public speaker, which includes understanding the psychology and neuroscience behind human perception and learning. For example, as highlighted in Rule 7, David JP Phillips has a wonderful TEDx talk on the subject [ 5 ], and “PowerPoint presentation flaws and failures: A psychological analysis,” by Kosslyn and colleagues is deeply detailed about a number of aspects of human cognition and presentation style [ 4 ]. There are many books on the topic, including the popular “Presentation Zen” by Garr Reynolds [ 11 ]. Finally, although briefly touched on here, the visualization of data is an entire topic of its own that is worth perfecting for both written and oral presentations of work, with fantastic resources like Edward Tufte’s “The Visual Display of Quantitative Information” [ 12 ] or the article “Visualization of Biomedical Data” by O’Donoghue and colleagues [ 13 ].

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the countless presenters, colleagues, students, and mentors from which I have learned a great deal from on effective presentations. Also, a thank you to the wonderful resources published by organizations on how to increase inclusivity. A special thanks to Dr. Jason Papin and Dr. Michael Guertin on early feedback of this editorial.

Funding Statement

The author received no specific funding for this work.

Loading metrics

Open Access

Ten simple rules for effective presentation slides

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Biomedical Engineering and the Center for Public Health Genomics, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia, United States of America

- Kristen M. Naegle

Published: December 2, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009554

- Reader Comments

Citation: Naegle KM (2021) Ten simple rules for effective presentation slides. PLoS Comput Biol 17(12): e1009554. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009554

Copyright: © 2021 Kristen M. Naegle. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: The author received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The author has declared no competing interests exist.

Introduction

The “presentation slide” is the building block of all academic presentations, whether they are journal clubs, thesis committee meetings, short conference talks, or hour-long seminars. A slide is a single page projected on a screen, usually built on the premise of a title, body, and figures or tables and includes both what is shown and what is spoken about that slide. Multiple slides are strung together to tell the larger story of the presentation. While there have been excellent 10 simple rules on giving entire presentations [ 1 , 2 ], there was an absence in the fine details of how to design a slide for optimal effect—such as the design elements that allow slides to convey meaningful information, to keep the audience engaged and informed, and to deliver the information intended and in the time frame allowed. As all research presentations seek to teach, effective slide design borrows from the same principles as effective teaching, including the consideration of cognitive processing your audience is relying on to organize, process, and retain information. This is written for anyone who needs to prepare slides from any length scale and for most purposes of conveying research to broad audiences. The rules are broken into 3 primary areas. Rules 1 to 5 are about optimizing the scope of each slide. Rules 6 to 8 are about principles around designing elements of the slide. Rules 9 to 10 are about preparing for your presentation, with the slides as the central focus of that preparation.

Rule 1: Include only one idea per slide

Each slide should have one central objective to deliver—the main idea or question [ 3 – 5 ]. Often, this means breaking complex ideas down into manageable pieces (see Fig 1 , where “background” information has been split into 2 key concepts). In another example, if you are presenting a complex computational approach in a large flow diagram, introduce it in smaller units, building it up until you finish with the entire diagram. The progressive buildup of complex information means that audiences are prepared to understand the whole picture, once you have dedicated time to each of the parts. You can accomplish the buildup of components in several ways—for example, using presentation software to cover/uncover information. Personally, I choose to create separate slides for each piece of information content I introduce—where the final slide has the entire diagram, and I use cropping or a cover on duplicated slides that come before to hide what I’m not yet ready to include. I use this method in order to ensure that each slide in my deck truly presents one specific idea (the new content) and the amount of the new information on that slide can be described in 1 minute (Rule 2), but it comes with the trade-off—a change to the format of one of the slides in the series often means changes to all slides.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

Top left: A background slide that describes the background material on a project from my lab. The slide was created using a PowerPoint Design Template, which had to be modified to increase default text sizes for this figure (i.e., the default text sizes are even worse than shown here). Bottom row: The 2 new slides that break up the content into 2 explicit ideas about the background, using a central graphic. In the first slide, the graphic is an explicit example of the SH2 domain of PI3-kinase interacting with a phosphorylation site (Y754) on the PDGFR to describe the important details of what an SH2 domain and phosphotyrosine ligand are and how they interact. I use that same graphic in the second slide to generalize all binding events and include redundant text to drive home the central message (a lot of possible interactions might occur in the human proteome, more than we can currently measure). Top right highlights which rules were used to move from the original slide to the new slide. Specific changes as highlighted by Rule 7 include increasing contrast by changing the background color, increasing font size, changing to sans serif fonts, and removing all capital text and underlining (using bold to draw attention). PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009554.g001

Rule 2: Spend only 1 minute per slide

When you present your slide in the talk, it should take 1 minute or less to discuss. This rule is really helpful for planning purposes—a 20-minute presentation should have somewhere around 20 slides. Also, frequently giving your audience new information to feast on helps keep them engaged. During practice, if you find yourself spending more than a minute on a slide, there’s too much for that one slide—it’s time to break up the content into multiple slides or even remove information that is not wholly central to the story you are trying to tell. Reduce, reduce, reduce, until you get to a single message, clearly described, which takes less than 1 minute to present.

Rule 3: Make use of your heading

When each slide conveys only one message, use the heading of that slide to write exactly the message you are trying to deliver. Instead of titling the slide “Results,” try “CTNND1 is central to metastasis” or “False-positive rates are highly sample specific.” Use this landmark signpost to ensure that all the content on that slide is related exactly to the heading and only the heading. Think of the slide heading as the introductory or concluding sentence of a paragraph and the slide content the rest of the paragraph that supports the main point of the paragraph. An audience member should be able to follow along with you in the “paragraph” and come to the same conclusion sentence as your header at the end of the slide.

Rule 4: Include only essential points

While you are speaking, audience members’ eyes and minds will be wandering over your slide. If you have a comment, detail, or figure on a slide, have a plan to explicitly identify and talk about it. If you don’t think it’s important enough to spend time on, then don’t have it on your slide. This is especially important when faculty are present. I often tell students that thesis committee members are like cats: If you put a shiny bauble in front of them, they’ll go after it. Be sure to only put the shiny baubles on slides that you want them to focus on. Putting together a thesis meeting for only faculty is really an exercise in herding cats (if you have cats, you know this is no easy feat). Clear and concise slide design will go a long way in helping you corral those easily distracted faculty members.

Rule 5: Give credit, where credit is due

An exception to Rule 4 is to include proper citations or references to work on your slide. When adding citations, names of other researchers, or other types of credit, use a consistent style and method for adding this information to your slides. Your audience will then be able to easily partition this information from the other content. A common mistake people make is to think “I’ll add that reference later,” but I highly recommend you put the proper reference on the slide at the time you make it, before you forget where it came from. Finally, in certain kinds of presentations, credits can make it clear who did the work. For the faculty members heading labs, it is an effective way to connect your audience with the personnel in the lab who did the work, which is a great career booster for that person. For graduate students, it is an effective way to delineate your contribution to the work, especially in meetings where the goal is to establish your credentials for meeting the rigors of a PhD checkpoint.

Rule 6: Use graphics effectively

As a rule, you should almost never have slides that only contain text. Build your slides around good visualizations. It is a visual presentation after all, and as they say, a picture is worth a thousand words. However, on the flip side, don’t muddy the point of the slide by putting too many complex graphics on a single slide. A multipanel figure that you might include in a manuscript should often be broken into 1 panel per slide (see Rule 1 ). One way to ensure that you use the graphics effectively is to make a point to introduce the figure and its elements to the audience verbally, especially for data figures. For example, you might say the following: “This graph here shows the measured false-positive rate for an experiment and each point is a replicate of the experiment, the graph demonstrates …” If you have put too much on one slide to present in 1 minute (see Rule 2 ), then the complexity or number of the visualizations is too much for just one slide.

Rule 7: Design to avoid cognitive overload

The type of slide elements, the number of them, and how you present them all impact the ability for the audience to intake, organize, and remember the content. For example, a frequent mistake in slide design is to include full sentences, but reading and verbal processing use the same cognitive channels—therefore, an audience member can either read the slide, listen to you, or do some part of both (each poorly), as a result of cognitive overload [ 4 ]. The visual channel is separate, allowing images/videos to be processed with auditory information without cognitive overload [ 6 ] (Rule 6). As presentations are an exercise in listening, and not reading, do what you can to optimize the ability of the audience to listen. Use words sparingly as “guide posts” to you and the audience about major points of the slide. In fact, you can add short text fragments, redundant with the verbal component of the presentation, which has been shown to improve retention [ 7 ] (see Fig 1 for an example of redundant text that avoids cognitive overload). Be careful in the selection of a slide template to minimize accidentally adding elements that the audience must process, but are unimportant. David JP Phillips argues (and effectively demonstrates in his TEDx talk [ 5 ]) that the human brain can easily interpret 6 elements and more than that requires a 500% increase in human cognition load—so keep the total number of elements on the slide to 6 or less. Finally, in addition to the use of short text, white space, and the effective use of graphics/images, you can improve ease of cognitive processing further by considering color choices and font type and size. Here are a few suggestions for improving the experience for your audience, highlighting the importance of these elements for some specific groups:

- Use high contrast colors and simple backgrounds with low to no color—for persons with dyslexia or visual impairment.

- Use sans serif fonts and large font sizes (including figure legends), avoid italics, underlining (use bold font instead for emphasis), and all capital letters—for persons with dyslexia or visual impairment [ 8 ].

- Use color combinations and palettes that can be understood by those with different forms of color blindness [ 9 ]. There are excellent tools available to identify colors to use and ways to simulate your presentation or figures as they might be seen by a person with color blindness (easily found by a web search).

- In this increasing world of virtual presentation tools, consider practicing your talk with a closed captioning system capture your words. Use this to identify how to improve your speaking pace, volume, and annunciation to improve understanding by all members of your audience, but especially those with a hearing impairment.

Rule 8: Design the slide so that a distracted person gets the main takeaway

It is very difficult to stay focused on a presentation, especially if it is long or if it is part of a longer series of talks at a conference. Audience members may get distracted by an important email, or they may start dreaming of lunch. So, it’s important to look at your slide and ask “If they heard nothing I said, will they understand the key concept of this slide?” The other rules are set up to help with this, including clarity of the single point of the slide (Rule 1), titling it with a major conclusion (Rule 3), and the use of figures (Rule 6) and short text redundant to your verbal description (Rule 7). However, with each slide, step back and ask whether its main conclusion is conveyed, even if someone didn’t hear your accompanying dialog. Importantly, ask if the information on the slide is at the right level of abstraction. For example, do you have too many details about the experiment, which hides the conclusion of the experiment (i.e., breaking Rule 1)? If you are worried about not having enough details, keep a slide at the end of your slide deck (after your conclusions and acknowledgments) with the more detailed information that you can refer to during a question and answer period.

Rule 9: Iteratively improve slide design through practice

Well-designed slides that follow the first 8 rules are intended to help you deliver the message you intend and in the amount of time you intend to deliver it in. The best way to ensure that you nailed slide design for your presentation is to practice, typically a lot. The most important aspects of practicing a new presentation, with an eye toward slide design, are the following 2 key points: (1) practice to ensure that you hit, each time through, the most important points (for example, the text guide posts you left yourself and the title of the slide); and (2) practice to ensure that as you conclude the end of one slide, it leads directly to the next slide. Slide transitions, what you say as you end one slide and begin the next, are important to keeping the flow of the “story.” Practice is when I discover that the order of my presentation is poor or that I left myself too few guideposts to remember what was coming next. Additionally, during practice, the most frequent things I have to improve relate to Rule 2 (the slide takes too long to present, usually because I broke Rule 1, and I’m delivering too much information for one slide), Rule 4 (I have a nonessential detail on the slide), and Rule 5 (I forgot to give a key reference). The very best type of practice is in front of an audience (for example, your lab or peers), where, with fresh perspectives, they can help you identify places for improving slide content, design, and connections across the entirety of your talk.

Rule 10: Design to mitigate the impact of technical disasters

The real presentation almost never goes as we planned in our heads or during our practice. Maybe the speaker before you went over time and now you need to adjust. Maybe the computer the organizer is having you use won’t show your video. Maybe your internet is poor on the day you are giving a virtual presentation at a conference. Technical problems are routinely part of the practice of sharing your work through presentations. Hence, you can design your slides to limit the impact certain kinds of technical disasters create and also prepare alternate approaches. Here are just a few examples of the preparation you can do that will take you a long way toward avoiding a complete fiasco:

- Save your presentation as a PDF—if the version of Keynote or PowerPoint on a host computer cause issues, you still have a functional copy that has a higher guarantee of compatibility.

- In using videos, create a backup slide with screen shots of key results. For example, if I have a video of cell migration, I’ll be sure to have a copy of the start and end of the video, in case the video doesn’t play. Even if the video worked, you can pause on this backup slide and take the time to highlight the key results in words if someone could not see or understand the video.

- Avoid animations, such as figures or text that flash/fly-in/etc. Surveys suggest that no one likes movement in presentations [ 3 , 4 ]. There is likely a cognitive underpinning to the almost universal distaste of pointless animations that relates to the idea proposed by Kosslyn and colleagues that animations are salient perceptual units that captures direct attention [ 4 ]. Although perceptual salience can be used to draw attention to and improve retention of specific points, if you use this approach for unnecessary/unimportant things (like animation of your bullet point text, fly-ins of figures, etc.), then you will distract your audience from the important content. Finally, animations cause additional processing burdens for people with visual impairments [ 10 ] and create opportunities for technical disasters if the software on the host system is not compatible with your planned animation.

Conclusions

These rules are just a start in creating more engaging presentations that increase audience retention of your material. However, there are wonderful resources on continuing on the journey of becoming an amazing public speaker, which includes understanding the psychology and neuroscience behind human perception and learning. For example, as highlighted in Rule 7, David JP Phillips has a wonderful TEDx talk on the subject [ 5 ], and “PowerPoint presentation flaws and failures: A psychological analysis,” by Kosslyn and colleagues is deeply detailed about a number of aspects of human cognition and presentation style [ 4 ]. There are many books on the topic, including the popular “Presentation Zen” by Garr Reynolds [ 11 ]. Finally, although briefly touched on here, the visualization of data is an entire topic of its own that is worth perfecting for both written and oral presentations of work, with fantastic resources like Edward Tufte’s “The Visual Display of Quantitative Information” [ 12 ] or the article “Visualization of Biomedical Data” by O’Donoghue and colleagues [ 13 ].

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the countless presenters, colleagues, students, and mentors from which I have learned a great deal from on effective presentations. Also, a thank you to the wonderful resources published by organizations on how to increase inclusivity. A special thanks to Dr. Jason Papin and Dr. Michael Guertin on early feedback of this editorial.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 3. Teaching VUC for Making Better PowerPoint Presentations. n.d. Available from: https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/making-better-powerpoint-presentations/#baddeley .

- 8. Creating a dyslexia friendly workplace. Dyslexia friendly style guide. nd. Available from: https://www.bdadyslexia.org.uk/advice/employers/creating-a-dyslexia-friendly-workplace/dyslexia-friendly-style-guide .

- 9. Cravit R. How to Use Color Blind Friendly Palettes to Make Your Charts Accessible. 2019. Available from: https://venngage.com/blog/color-blind-friendly-palette/ .

- 10. Making your conference presentation more accessible to blind and partially sighted people. n.d. Available from: https://vocaleyes.co.uk/services/resources/guidelines-for-making-your-conference-presentation-more-accessible-to-blind-and-partially-sighted-people/ .

- 11. Reynolds G. Presentation Zen: Simple Ideas on Presentation Design and Delivery. 2nd ed. New Riders Pub; 2011.

- 12. Tufte ER. The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. 2nd ed. Graphics Press; 2001.

Home Blog Business Conference Presentation Slides: A Guide for Success

Conference Presentation Slides: A Guide for Success

In our experience, a common error when preparing a conference presentation is using designs that heavily rely on bullet points and massive chunks of text. A potential reason behind this slide design mistake is aiming to include as much information as possible in just one slide. In the end, slides become a sort of teleprompter for the speaker, and the audience recalls boredom instead of an informative experience.

As part of our mission to help presenters deliver their message effectively, we have summarized what makes a good conference presentation slide, as well as tips on how to design a successful conference slide.

Table of Contents

What is a conference presentation

Common mistakes presenters make when creating conference presentation slides, how can a well-crafted conference presentation help your professional life, how to start a conference presentation, how to end a conference presentation, tailoring your message to different audiences, visualizing data effectively, engaging with your audience, designing for impact, mastering slide transitions and animation, handling time constraints, incorporating multimedia elements, post-presentation engagement, crisis management during presentations, sustainability and green presentations, measuring presentation success, 13 tips to create stellar conference presentations, final thoughts.

The Britannica Dictionary defines conferences as

A formal meeting in which many people gather in order to talk about ideas or problems related to a particular topic (such as medicine or business), usually for several days.

We can then define conference presentations as the combination of a speaker, a slide deck , and the required hardware to introduce an idea or topic in a conference setting. Some characteristics differentiate conference presentations from other formats.

Time-restricted

Conference presentations are bounded by a 15-30 minute time limit, which the event’s moderators establish. These restrictions are applied to allow a crowded agenda to be met on time, and it is common to count with over 10 speakers on the same day.

To that time limit, we have to add the time required for switching between speakers, which implies loading a new slide deck to the streaming platform, microphone testing, lighting effects, etc. Say it is around 10-15 minutes extra, so depending on the number of speakers per day during the event, the time available to deliver a presentation, plus the questions & answers time.

Delivery format

Conferences can be delivered in live event format or via webinars. Since this article is mainly intended to live event conferences, we will only mention that the requirements for webinars are as follows:

- Voice-over or, best, speaker layover the presentation slides so the speaker interacts with the audience.

- Quality graphics.

- Not abusing the amount of information to introduce per slide.

On the other hand, live event conferences will differ depending on the category under which they fall. Academic conferences have a structure in which there’s a previous poster session; then speakers start delivering their talks, then after 4-5 speakers, we have a coffee break. Those pauses help the AV crew to check the equipment, and they also become an opportunity for researchers to expand their network contacts.

Business conferences are usually more dynamic. Some presenters opt not to use slide decks, giving a powerful speech instead, as they feel much more comfortable that way. Other speakers at business conferences adopt videos to summarize their ideas and then proceed to speak.

Overall, the format guidelines are sent to speakers before the event. Adapt your presentation style to meet the requirements of moderators so you can maximize the effect of your message.

The audience

Unlike other presentation settings, conferences gather a knowledgeable audience on the discussed topics. It is imperative to consider this, as tone, delivery format, information to include, and more depend on this sole factor. Moreover, the audience will participate in your presentation at the last minute, as it is a common practice to hold a Q&A session.

Mistake #1 – Massive chunks of text

Do you intend your audience to read your slides instead of being seduced by your presentation? Presenters often add large amounts of text to each slide since they need help deciding which data to exclude. Another excuse for this practice is so the audience remembers the content exposed.

Research indicates images are much better retained than words, a phenomenon known as the Picture Superiority Effect ; therefore, opt to avoid this tendency and work into creating compelling graphics.

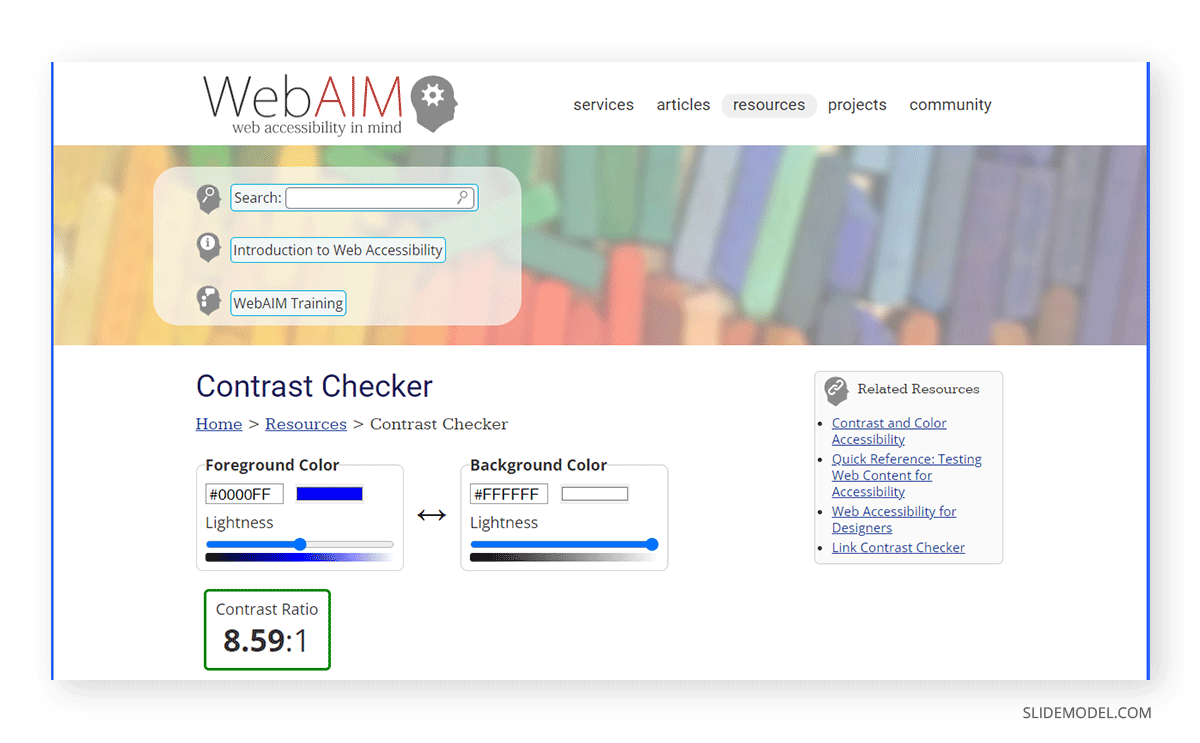

Mistake #2 – Not creating contrast between data and graphics

Have you tried to read a slide from 4 rows behind the presenter and not get a single number? This can happen if the presenter is not careful to work with the appropriate contrast between the color of the typeface and the background. Particularly if serif fonts are used.

Use online tools such as WebAIM’s Contrast Checker to make your slides legible for your audience. Creating an overlay with a white or black transparent tint can also help when you place text above images.

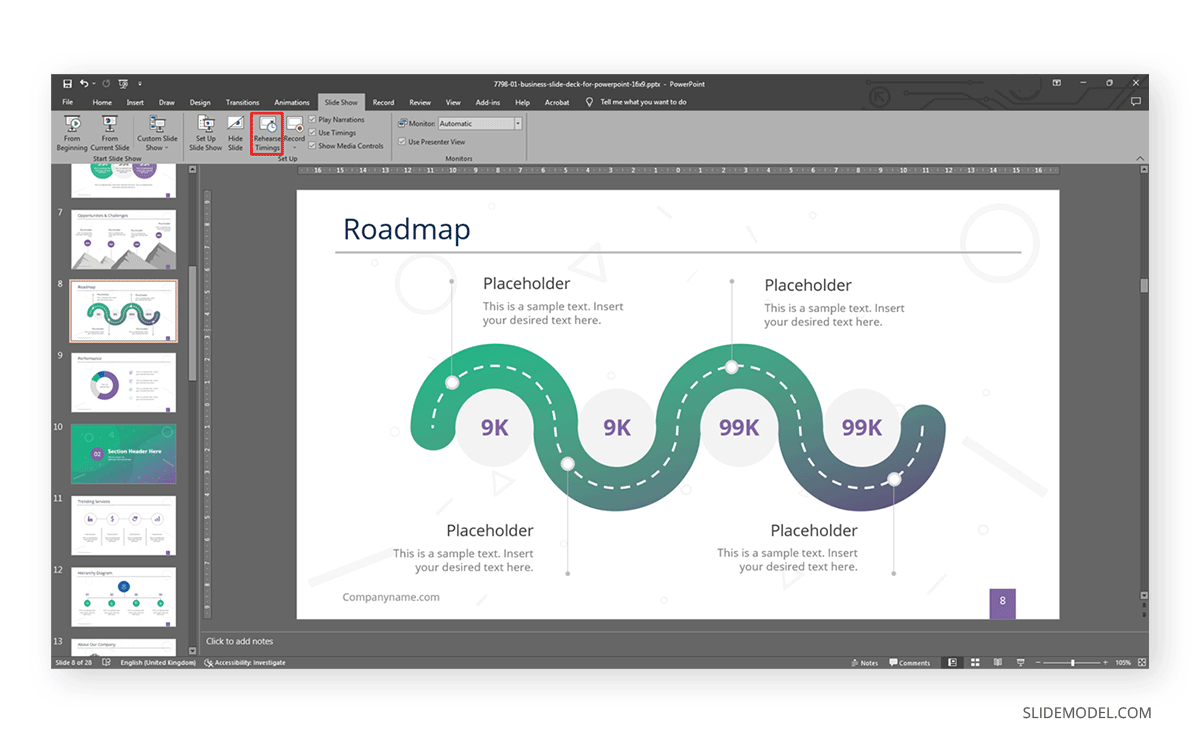

Mistake #3 – Not rehearsing the presentation

This is a sin in conference presentations, as when you don’t practice the content you intend to deliver, you don’t have a measure of how much time it is actually going to take.

PowerPoint’s rehearse timing feature can help a great deal, as you can record yourself practising the presentation and observe areas for improvement. Remember, conference presentations are time-limited , don’t disrespect fellow speakers by overlapping their scheduled slot or, worse, have moderators trim your presentation after several warnings.

Mistake #4 – Lacking hierarchy for the presented content

Looking at a slide and not knowing where the main point is discouraging for the audience, especially if you introduce several pieces of content under the same slide. Instead, opt to create a hierarchy that comprehends both text and images. It helps to arrange the content according to your narrative, and we’ll see more on this later on.

Consider your conference presentation as your introduction card in the professional world. Maybe you have a broad network of colleagues, but be certain there are plenty of people out there that have yet to learn about who you are and the work you produce.

Conferences help businesspeople and academics alike to introduce the results of months of research on a specific topic in front of a knowledgeable audience. It is different from a product launch as you don’t need to present a “completed product” but rather your views or advances, in other words, your contribution with valuable insights to the field.

Putting dedication into your conference presentation, from the slide deck design to presentation skills , is definitely worth the effort. The audience can get valuable references from the quality of work you are able to produce, often leading to potential partnerships. In business conferences, securing an investor deal can happen after a powerful presentation that drives the audience to perceive your work as the very best thing that’s about to be launched. It is all about how your body language reflects your intent, how well-explained the concepts are, and the emotional impact you can drive from it.

There are multiple ways on how to start a presentation for a conference, but overall, we can recap a good approach as follows.

Present a fact

Nothing grabs the interest of an audience quicker than introducing an interesting fact during the first 30 seconds of your presentation. The said fact has to be pivotal to the content your conference presentation will discuss later on, but as an ice-breaker, it is a strategy worth applying from time to time.

Ask a question

The main point when starting a conference presentation is to make an impact on the audience. We cannot think of a better way to engage with the audience than to ask them a question relevant to your work or research. It grabs the viewer’s interest for the potential feedback you shall give to those answers received.

Use powerful graphics

The value of visual presentations cannot be neglected in conferences. Sometimes an image makes a bigger impact than a lengthy speech, hence why you should consider starting your conference presentation with a photo or visual element that speaks for itself.

For more tips and insights on how to start a presentation , we invite you to check this article.

Just as important as starting the presentation, the closure you give to your conference presentation matters a lot. This is the opportunity in which you can add your personal experience on the topic and reflect upon it with the audience or smoothly transition between the presentation and your Q&A session.

Below are some quick tips on how to end a presentation for a conference event.

End the presentation with a quote

Give your audience something to ruminate about with the help of a quote tailored to the topic you were discussing. There are plenty of resources for finding suitable quotes, and a great method for this is to design your penultimate slide with an image or black background plus a quote. Follow this with a final “thank you” slide.

Consider a video

If we say a video whose length is shorter than 1 minute, this is a fantastic resource to summarize the intent of your conference presentation.

If you get the two-minute warning and you feel far off from finishing your presentation, first, don’t fret. Try to give a good closure when presenting in a conference without rushing information, as the audience wouldn’t get any concept clear that way. Mention that the information you presented will be available for further reading at the event’s platform site or your company’s digital business card , and proceed to your closure phase for the presentation.

It is better to miss some of the components of the conference than to get kicked out after several warnings for exceeding the allotted time.

Tailoring your conference presentation to suit your audience is crucial to delivering an impactful talk. Different audiences have varying levels of expertise, interests, and expectations. By customizing your content, tone, and examples, you can enhance the relevance and engagement of your presentation.

Understanding Audience Backgrounds and Expectations

Before crafting your presentation, research your audience’s backgrounds and interests. Are they professionals in your field, students, or a mix of both? Are they familiar with the topic, or must you provide more context? Understanding these factors will help you pitch your content correctly and avoid overwhelming or boring your audience.

Adapting Language and Tone for Relevance

Use language that resonates with your audience. Avoid jargon or technical terms that might confuse those unfamiliar with your field. Conversely, don’t oversimplify if your audience consists of experts. Adjust your tone to match the event’s formality and your listeners’ preferences.

Customizing Examples and Case Studies

Incorporate case studies, examples, and anecdotes that your audience can relate to. If you’re speaking to professionals, use real-world scenarios from their industry. For a more general audience, choose examples that are universally relatable. This personal touch makes your content relatable and memorable.

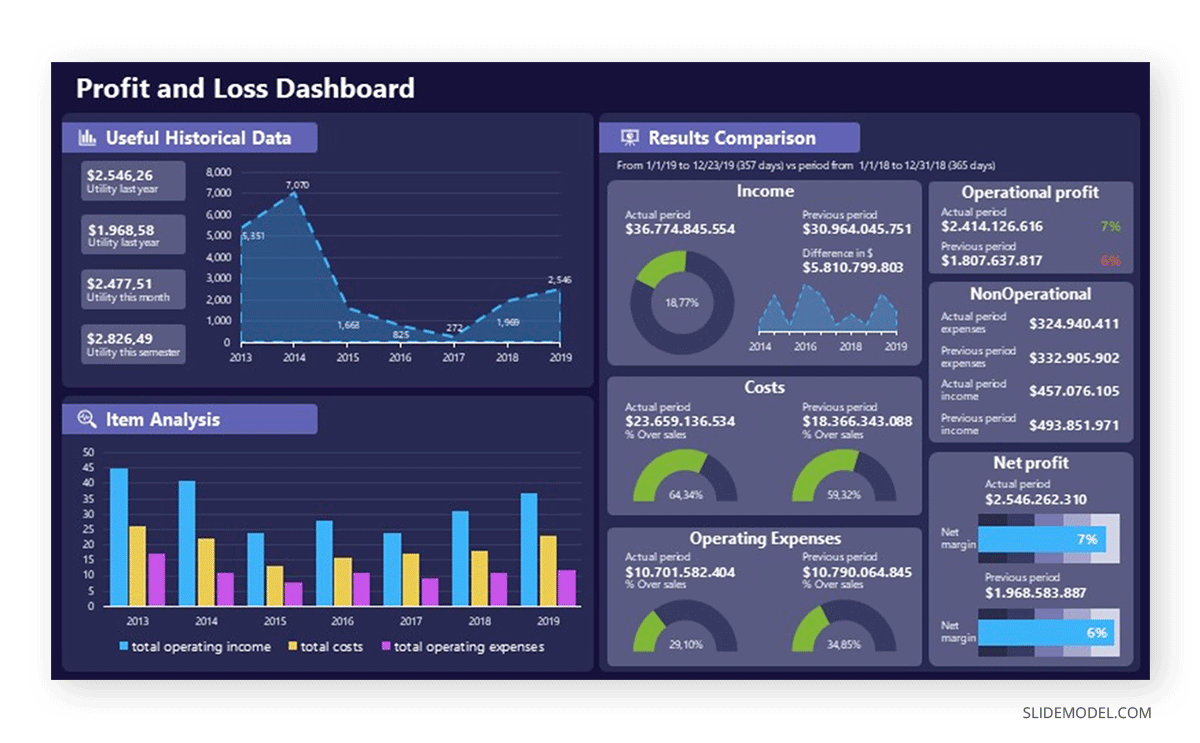

Effectively presenting data is essential for conveying complex information to your audience. Visualizations can help simplify intricate concepts and make your points more digestible.

Choosing the Right Data Representation

Select the appropriate type of graph or chart to illustrate your data. Bar graphs, pie charts, line charts, and scatter plots each serve specific purposes. Choose the one that best supports your message and ensures clarity.

Designing Graphs and Charts for Clarity

Ensure your graphs and charts are easily read. Use clear labels, appropriate color contrasts, and consistent scales. Avoid clutter and simplify the design to highlight the most important data points.

Incorporating Annotations and Explanations

Add annotations or callouts to your graphs to emphasize key findings. Explain the significance of each data point to guide your audience’s understanding. Utilize visual cues, such as arrows and labels, to direct attention.

Engaging your audience is a fundamental skill for a successful presentation for conference. Captivate their attention, encourage participation, and foster a positive connection.

Establishing Eye Contact and Body Language

Maintain eye contact with different audience parts to create a sense of connection. Effective body language, such as confident posture and expressive gestures, enhances your presence on stage.

Encouraging Participation and Interaction

Involve your audience through questions, polls, or interactive activities. Encourage them to share their thoughts or experiences related to your topic. This engagement fosters a more dynamic and memorable presentation.

Using Humor and Engaging Stories

Incorporate humor and relatable anecdotes to make your presentation more enjoyable. Well-timed jokes or personal stories can create a rapport with your audience and make your content more memorable.

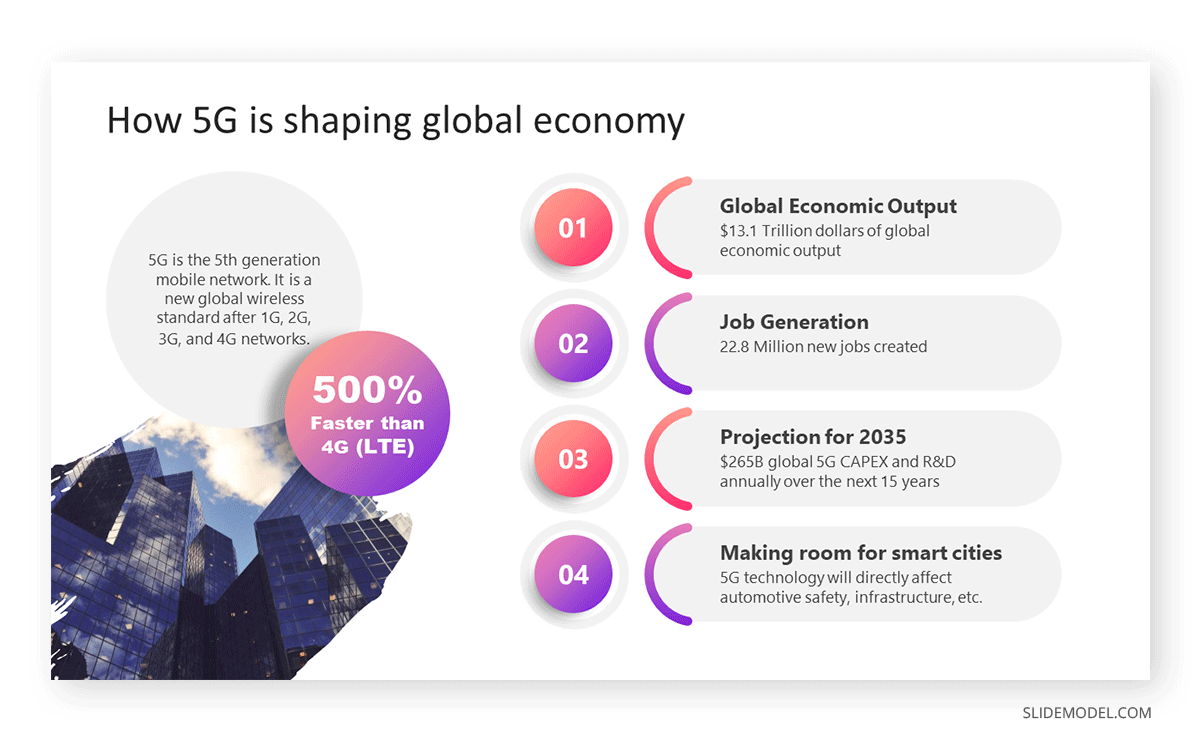

The design of your conference presentation slides plays a crucial role in capturing and retaining your audience’s attention. Thoughtful design can amplify your message and reinforce key points. Take a look at these suggestions to boost the performance of your conference presentation slides, or create an entire slide deck in minutes by using SlideModel’s AI Presentation Maker from text .

Creating Memorable Opening Slides

Craft an opening slide that piques the audience’s curiosity and sets the tone for your presentation. Use an engaging visual, thought-provoking quote, or intriguing question to grab their attention from the start.

Using Visual Hierarchy for Emphasis

Employ visual hierarchy to guide your audience’s focus. Highlight key points with larger fonts, bold colors, or strategic placement. Organize information logically to enhance comprehension.

Designing a Powerful Closing Slide

End your presentation with a compelling closing slide that reinforces your main message. Summarize your key points, offer a memorable takeaway, or invite the audience to take action. Use visuals that resonate and leave a lasting impression.

Slide transitions and animations can enhance the flow of your presentation and emphasize important content. However, their use requires careful consideration to avoid distractions or confusion.

Enhancing Flow with Transitions

Select slide transitions that smoothly guide the audience from one point to the next. Avoid overly flashy transitions that detract from your content. Choose options that enhance, rather than disrupt, the presentation’s rhythm.

Using Animation to Highlight Points

Animate elements on your slides to draw attention to specific information. Animate text, images, or graphs to appear as you discuss them, helping the audience follow your narrative more effectively.

Avoiding Overuse of Effects

While animation can be engaging, avoid excessive use that might overwhelm or distract the audience. Maintain a balance between animated elements and static content for a polished presentation.

Effective time management is crucial for delivering a concise and impactful conference presentation within the allocated time frame.

Structuring for Short vs. Long Presentations

Adapt your content and pacing based on the duration of your presentation. Clearly outline the main points for shorter talks, and delve into more depth for longer sessions. Ensure your message aligns with the time available.

Prioritizing Key Information

Identify the core information you want your audience to take away. Focus on conveying these essential points, and be prepared to trim or elaborate on supporting details based on the available time.

Practicing Time Management

Rehearse your presentation while timing yourself to ensure you stay within the allocated time. Adjust your delivery speed to match your time limit, allowing for smooth transitions and adequate Q&A time.

Multimedia elements, such as videos, audio clips, and live demonstrations, can enrich your presentation and provide a dynamic experience for your audience.

Integrating Videos and Audio Clips

Use videos and audio clips strategically to reinforce your points or provide real-world examples. Ensure that the multimedia content is of high quality and directly supports your narrative.

Showcasing Live Demonstrations

Live demonstrations can engage the audience by showcasing practical applications of your topic. Practice the demonstration beforehand to ensure it runs smoothly and aligns with your message.

Using Hyperlinks for Additional Resources

Incorporate hyperlinks into your presentation to direct the audience to additional resources, references, or related content. This allows interested attendees to explore the topic further after the presentation.

Engaging with your audience after your presentation can extend the impact of your talk and foster valuable connections.

Leveraging Post-Presentation Materials

Make your presentation slides and related materials available to attendees after the event. Share them through email, a website, or a conference platform, allowing interested individuals to review the content.

Sharing Slides and Handouts

Provide downloadable versions of your slides and any handouts you used during the presentation. This helps attendees revisit key points and share the information with colleagues.

Networking and Following Up

Utilize networking opportunities during and after the conference to connect with attendees who are interested in your topic. Exchange contact information and follow up with personalized messages to continue the conversation.

Preparing for unexpected challenges during your presenting at a conference can help you maintain professionalism and composure, ensuring a seamless delivery.

Dealing with Technical Glitches

Technical issues can occur, from projector malfunctions to software crashes. Stay calm and have a backup plan, such as having your slides available on multiple devices or using printed handouts.

Handling Unexpected Interruptions

Interruptions, such as questions from the audience or unforeseen disruptions, are a normal part of live presentations. Address them politely, stay adaptable, and seamlessly return to your prepared content.

Staying Calm and Professional

Maintain a composed demeanor regardless of unexpected situations. Your ability to handle challenges gracefully reflects your professionalism and dedication to delivering a successful presentation.

Creating environmentally friendly presentations demonstrates your commitment to sustainability and responsible practices.

Designing Eco-Friendly Slides

Minimize the use of resources by designing slides with efficient layouts, avoiding unnecessary graphics or animations, and using eco-friendly color schemes.

Reducing Paper and Material Waste

Promote a paperless approach by encouraging attendees to access digital materials rather than printing handouts. If print materials are necessary, consider using recycled paper.

Promoting Sustainable Practices

Advocate for sustainability during your presentation by discussing relevant initiatives, practices, or innovations that align with environmentally conscious values.

Measuring the success of your conference presentation goes beyond the applause and immediate feedback. It involves assessing the impact of your presentation on your audience, goals, and growth as a presenter.

Collecting Audience Feedback

After presenting at a conference, gather feedback from attendees. Provide feedback forms or online surveys to capture their thoughts on the content, delivery, and visuals. Analyzing their feedback can reveal areas for improvement and give insights into audience preferences.

Evaluating Key Performance Metrics

Consider objective metrics such as audience engagement, participation, and post-presentation interactions. Did attendees ask questions? Did your content spark discussions? Tracking these metrics can help you gauge the effectiveness of your presentation in conveying your message.

Continuous Improvement Strategies

Use the feedback and insights gathered to enhance your future presentations. Identify strengths to build upon and weaknesses to address. Continuously refine your presentation skills , design choices, and content to create even more impactful presentations in the future.

Tip #1 – Exhibit a single idea per slide

Just one slide per concept, avoiding large text blocks. If you can compile the idea with an image, it’s better that way.

Research shows that people’s attention span is limited ; therefore, redirect your efforts in what concerns presentation slides so your ideas become crystal clear for the spectators.

Tip #2 – Avoid jargon whenever possible

Using complex terms does not directly imply you fully understand the concept you are about to discuss. In spite of your work being presented to a knowledgeable audience, avoid jargon as much as possible because you run the risk of people not understanding what you are saying.

Instead, opt to rehearse your presentation in front of a not-knowledgeable audience to measure the jargon volume you are adding to it. Technical terms are obviously expected in a conference situation, but archaic terms or purely jargon can be easily trimmed this way.

Tip #3 – Replace bulleted listings with structured layouts or diagrams

Bullet points are attention grabbers for the audience. People tend to instantly check what’s written in them, in contrast to waiting for you to introduce the point itself.

Using bullet points as a way to expose elements of your presentation should be restricted. Opt for limiting the bullet points to non-avoidable facts to list or crucial information.

Tip #4 – Customize presentation templates

Using presentation templates is a great idea to save time in design decisions. These pre-made slide decks are entirely customizable; however, many users fall into using them as they come, exposing themselves to design inconsistencies (especially with images) or that another presenter had the same idea (it is extremely rare, but it can happen).

Learning how to properly change color themes in PowerPoint is an advantageous asset. We also recommend you use your own images or royalty-free images selected by you rather than sticking to the ones included in a template.

Tip #5 – Displaying charts

Graphs and charts comprise around 80% of the information in most business and academic conferences. Since data visualization is important, avoid common pitfalls such as using 3D effects in bar charts. Depending on the audience’s point of view, those 3D effects can make the data hard to read or get an accurate interpretation of what it represents.

Tip #6 – Using images in the background

Use some of the images you were planning to expose as background for the slides – again, not all of them but relevant slides.

Be careful when placing text above the slides if they have a background image, as accessibility problems may arise due to contrast. Instead, apply an extra color layer above the image with reduced opacity – black or white, depending on the image and text requirements. This makes the text more legible for the audience, and you can use your images without any inconvenience.

Tip #7 – Embrace negative space

Negative space is a concept seen in design situations. If we consider positive space as the designed area, meaning the objects, shapes, etc., that are “your design,” negative space can be defined as the surrounding area. If we work on a white canvas, negative space is the remaining white area surrounding your design.

The main advantage of using negative space appropriately is to let your designs breathe. Stuffing charts, images and text makes it hard to get a proper understanding of what’s going on in the slide. Apply the “less is more” motto to your conference presentation slides, and embrace negative space as your new design asset.

Tip #8 – Use correct grammar, spelling, and punctuation

You would be surprised to see how many typos can be seen in slides at professional gatherings. Whereas typos can often pass by as a humor-relief moment, grammatical or awful spelling mistakes make you look unprofessional.

Take 5 extra minutes before submitting your slide deck to proofread the grammar, spelling, and punctuation. If in doubt, browse dictionaries for complex technical words.

Tip #10 – Use an appropriate presentation style

The format of the conference will undoubtedly require its own presentation style. By this we mean that it is different from delivering a conference presentation in front of a live audience as a webinar conference. The interaction with the audience is different, the demands for the Q&A session will be different, and also during webinars the audience is closely looking at your slides.

Tip #11 – Control your speaking tone

Another huge mistake when delivering a conference presentation is to speak with a monotonous tone. The message you transmit to your attendees is that you simply do not care about your work. If you believe you fall into this category, get feedback from others: try pitching to them, and afterward, consider how you talk.

Practicing breathing exercises can help to articulate your speech skills, especially if anxiety hinders your presentation performance.

Tip #12 – On eye contact and note reading

In order to connect with your audience, it is imperative to make eye contact. Not stare, but look at your spectators from time to time as the talk is directed at them.

If you struggle on this point, a good tip we can provide is to act like you’re looking at your viewers. Pick a good point a few centimeters above your viewer and direct your speech there. They will believe you are communicating directly with them. Shift your head slightly on the upcoming slide or bullet and choose a new location.

Regarding note reading, while it is an acceptable practice to check your notes, do not make the entire talk a lecture in which you simply read your notes to the audience. This goes hand-by-hand with the speaking tone in terms of demonstrating interest in the work you do. Practice as often as you need before the event to avoid constantly reading your notes. Reading a paragraph or two is okay, but not the entire presentation.

Tip #13 – Be ready for the Q&A session

Despite it being a requirement in most conference events, not all presenters get ready for the Q&A session. It is a part of the conference presentation itself, so you should pace your speech to give enough time for the audience to ask 1-3 questions and get a proper answer.

Don’t be lengthy or overbearing in replying to each question, as you may run out of time. It is preferable to give a general opinion and then reach the interested person with your contact information to discuss the topic in detail.

Observing what others do at conference events is good practice for learning a tip or two for improving your own work. As we have seen throughout this article, conference presentation slides have specific requirements to become a tool in your presentation rather than a mixture of information without order.

Employ these tips and suggestions to craft your upcoming conference presentation without any hurdles. Best of luck!

1. Conference PowerPoint Template

Use This Template

2. Free Conference Presentation Template

Like this article? Please share

Presentation Approaches, Presentation Skills, Presentation Tips Filed under Business

Related Articles

Filed under Google Slides Tutorials • May 22nd, 2024

How to Add Audio to Google Slides

Making your presentations accessible shouldn’t be a hard to accomplish task. Learn how to add audios to Google Slides and improve the quality and accessibility of your presentations.

How to Translate Google Slides

Whereas Google Slides doesn’t allow to natively translate slides, such process is possible thanks to third-party add-ons. Learn how to translate Google Slides with this guide!

Filed under Design • May 22nd, 2024

Exploring the 12 Different Types of Slides in PowerPoint

Become a better presenter by harnessing the power of the 12 different types of slides in presentation design.

Leave a Reply

10 Rules for Paper Presentation in Conference

Are you gearing up for a conference presentation? If so, then navigating the world of academic conferences can be a daunting task, but fear not, as we unveil the key to a stellar performance: 10 rules for paper presentation in conference.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll walk you through the essential principles that will not only boost your confidence but also ensure your research leaves a lasting impression. Whether you’re a seasoned presenter or new to the conference scene, these rules are your roadmap to success.

From crafting compelling visuals to mastering the art of engaging your audience, we’ve got you covered. Join us on this journey as we unravel the secrets to delivering a conference presentation that captivates, educates, and inspires.

What Does the Paper Presentation Mean?

Paper presentation is a vital aspect of academic and professional communication. It serves as a means to spread research findings, innovative ideas, and valuable insights to a diverse audience. These conference paper presentations play a crucial role in conference on arts and education by exchanging knowledge and scholarly discourses.

Effective paper presentations require clear articulation of research objectives, methodologies, and results. Engaging visuals, concise messaging, and audience interaction are crucial elements in conveying complex information. Presenters must also navigate challenges such as time constraints, technical issues, and audience questions gracefully to ensure a successful delivery.

Conference paper presentations often serve as a platform to showcase expertise, establish professional networks, and garner feedback for future research endeavors. Whether in an academic setting or an industry conference, mastering the art of paper presentation is a skill that can significantly impact one’s career and contribute to the advancement of knowledge in various fields.

Types of Paper Presentations

Paper presentations come in various formats, each tailored to specific goals and audiences. These diverse types of presentations are vital in academic and professional settings, serving as vehicles for sharing research findings, ideas, and insights. Here’s a brief overview of some common types:

Oral Presentations

Poster Presentations

In this format, presenters use posters to visually represent their research. Poster sessions offer a more informal setting for one-on-one discussions and are common at academic conferences. They provide a chance to showcase research in a concise and visually engaging manner.

Panel Discussions

Panel presentations involve a group of experts discussing a specific topic or issue. Each panelist shares insights, providing multiple perspectives and fostering in-depth exploration of the subject. Panel discussions are valuable for presenting a well-rounded view of complex topics.

Lightning Talks

Lightning talks are brief, typically 5-10 minute presentations designed to provide quick overviews of research projects or ideas. They are concise and often used to introduce a topic or concept swiftly, making them ideal for conveying key points in a short timeframe.

Symposia are organized sessions that bring together multiple presenters to address a broader theme or research area. They usually consist of several related presentations and discussions, offering attendees a comprehensive exploration of the symposium’s overarching topic.

Workshops are interactive sessions where presenters engage the audience in hands-on activities, skill-building exercises, or collaborative problem-solving. They offer a more immersive learning experience, allowing participants to actively engage with the material presented.

Presenting your research at conferences is a vital opportunity, and the ’10 Rules for Paper Presentation in Conference’ can help you excel. These rules cover key aspects to make your presentations more effective and impactful.

1. Know Your Audience

Understanding your audience’s background, interests, and expertise allows you to tailor your presentation to their specific needs. It enables you to choose the most relevant examples, terminology, and delivery style that will resonate with your audience, fostering a deeper connection and engagement.

2. Craft a Clear Message

A well-structured presentation in a conference with a clear message not only helps your audience follow your research effortlessly but also ensures that they leave with a strong understanding of your key findings. Use a logical flow and a narrative structure that guides them from the problem to the solution, making it easy to absorb complex information.

3. Engage with Compelling Visuals

Utilizing compelling visuals, such as charts, graphs, and images, not only enhances comprehension but also keeps your audience engaged and interested. Well-designed visuals can simplify complex concepts and make your presentation more memorable.

4. Practice, Practice, Practice

Thorough rehearsal is essential to boost your confidence, minimize anxiety, and ensure a polished delivery. It allows you to refine your timing, pacing, and transitions, making your presentation smooth and engaging. Practice in front of peers or mentors to receive constructive feedback.

5. Manage Your Time Wisely

Staying within your allotted presentation time is vital to maintain audience interest and accommodate questions and discussions. Allocate time for each section of your presentation, including a buffer for potential delays, to ensure a smooth and controlled delivery.

6. Dress and Act Professionally

Professional attire and confident body language create a positive impression, helping you establish credibility and captivate your audience. Maintain eye contact, use gestures purposefully, and exhibit enthusiasm for your topic.

7. Connect with Your Audience

Engaging with your audience through eye contact, relatable anecdotes, and interactive elements fosters a stronger connection and enhances understanding. Encourage questions and participation to create a dynamic and engaging atmosphere.

8. Handle Questions with Grace

Effective handling of questions, whether expected or unexpected, demonstrates your expertise and keeps the audience engaged. Be polite, concise, and confident in your responses, and use questions as an opportunity to further emphasize your key points.

9. Rehearse the Q&A Session

Preparation for the Q&A segment is essential. Anticipate potential questions and practice your responses to ensure a smooth and informative discussion. Prepare concise and insightful answers that provide added value to your presentation.

10. Seek Feedback and Continuous Improvement

Gathering feedback from peers and mentors is essential for refining your presentation skills. Act on constructive criticism to improve your future presentations, ensuring that each one is better than the last and aligns more closely with your goals and audience expectations.

With these 10 rules, you can confidently navigate the world of conference presentations, captivate your audience, and make a significant impact with your research.

Why Is Paper Presentation Important at A Conference?

They serve as a vital medium for knowledge dissemination, allowing researchers to share their findings, insights, and innovations with a diverse and knowledgeable audience. This dissemination fosters the exchange of ideas and facilitates collaboration, potentially leading to advancements in various fields of study.

Paper presentations offer a platform for constructive critique and feedback, enabling presenters to refine their research and ideas. Engaging with fellow experts and peers during the Q&A sessions and discussions promotes critical thinking and enhances the quality of research work.

Conference paper presentations contribute significantly to one’s professional development. They provide opportunities to showcase expertise, gain recognition, and establish a presence in a particular field. Additionally, the networking opportunities that conferences offer can lead to valuable collaborations and career-enhancing connections.

The importance of paper presentations at conferences lies in their role as a conduit for the dissemination of knowledge, a forum for constructive engagement, and a catalyst for professional growth and recognition within the academic and professional communities.

Bottom Line

The ’10 Rules for Paper Presentation in Conference’ offer essential guidance for successful presentations. These rules help you connect with your audience, communicate your research effectively, and leave a lasting impression. Whether you’re a seasoned presenter or new to conferences, these rules serve as valuable tools for success.

Paper presentations are key in sharing knowledge, receiving feedback, and building your professional network. They bridge the gap between researchers and their audience, fostering collaboration and idea exchange.

So, as you prepare for your next conference, keep these rules in mind. They will empower you to deliver impactful presentations, connect with your audience, and make a meaningful contribution to your field.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Don’t miss our future updates! Get subscribed today!

Sign up for email updates and stay in the know about all things Conferences including price changes, early bird discounts, and the latest speakers added to the roster.

Meet and Network With International Delegates from Multidisciplinary Backgrounds.

Useful Links

Quick links, secure payment.

Copyright © Global Conference Alliance Inc 2018 – 2024. All Rights Reserved. Developed by Giant Marketers Inc .

Conference Papers

What this handout is about.

This handout outlines strategies for writing and presenting papers for academic conferences.

What’s special about conference papers?

Conference papers can be an effective way to try out new ideas, introduce your work to colleagues, and hone your research questions. Presenting at a conference is a great opportunity for gaining valuable feedback from a community of scholars and for increasing your professional stature in your field.

A conference paper is often both a written document and an oral presentation. You may be asked to submit a copy of your paper to a commentator before you present at the conference. Thus, your paper should follow the conventions for academic papers and oral presentations.

Preparing to write your conference paper

There are several factors to consider as you get started on your conference paper.