- Skip to main content

- Skip to secondary menu

Wylie Communications, Inc.

Writing workshops, communication consulting and writing services

How to write a good feature lead

Show, don’t tell, in the first paragraph.

Get more tips on feature leads on Rev Up Readership.

Share this:

Reach more readers with our writing tips.

Learn to get the word out with our proven-in-the-lab techniques in our email newsletter.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 6: Feature Writing

26 Feature leads

Unlike the traditional summary lead, feature leads can be several sentences long, and the writer may not immediately reveal the story’s main idea. The most common types used in feature articles are anecdotal leads and descriptive leads. An anecdotal lead unfolds slowly. It lures the reader in with a descriptive narrative that focuses on a specific minor aspect of the story that leads to the overall topic. The following is an example of an anecdotal lead:

Sharon Jackson was sitting at the table reading an old magazine when the phone rang. It was a reporter asking to set up an interview to discuss a social media controversy involving Jackson and another young woman.“Sorry,” she said. “I’ve already spoken to several reporters about the incident and do not wish to make any further comments.”

Notice that the lead unfolds more slowly than a traditional lead and centers on a particular aspect of the larger story. The nut graph, or a paragraph that reveals the importance of the minor story and how it fits into the broader story, would come after the lead. There will be more on the nut graph later in this chapter.

Descriptive leads begin the article by describing a person, place, or event in vivid detail. They focus on setting the scene for the piece and use language that taps into the five senses in order to paint a picture for the reader. This type of lead can be used for both traditional news and feature stories. The following is an example of a descriptive lead:

Thousands dressed in scarlet and gray T-shirts eagerly shuffled into the football stadium as the university fight song blared.

For each article below, identify whether it uses a descriptive or anecdotal lead:

- A thin line of defense

- Pediatric patient

- Inside Jay Z’s Roc Nation

Writing for Strategic Communication Industries Copyright © 2016 by Jasmine Roberts is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

from training.npr.org: https://training.npr.org/2016/10/12/leads-are-hard-heres-how-to-write-a-good-one/

- Style Guide

A good lead is everything — here's how to write one

- More on Digital

- Subscribe to Digital

(Deborah Lee/NPR)

I can’t think of a better way to start a post about leads than with this:

“The most important sentence in any article is the first one. If it doesn’t induce the reader to proceed to the second sentence, your article is dead.” — William Zinsser, On Writing Well

No one wants a dead article! A story that goes unread is pointless. The lead is the introduction — the first sentences — that should pique your readers’ interest and curiosity. And it shouldn’t be the same as your radio intro, which t ells listeners what the story is about and why they should care. In a written story, that’s the function of the “nut graph” (which will be the subject of a future post) — not the lead.

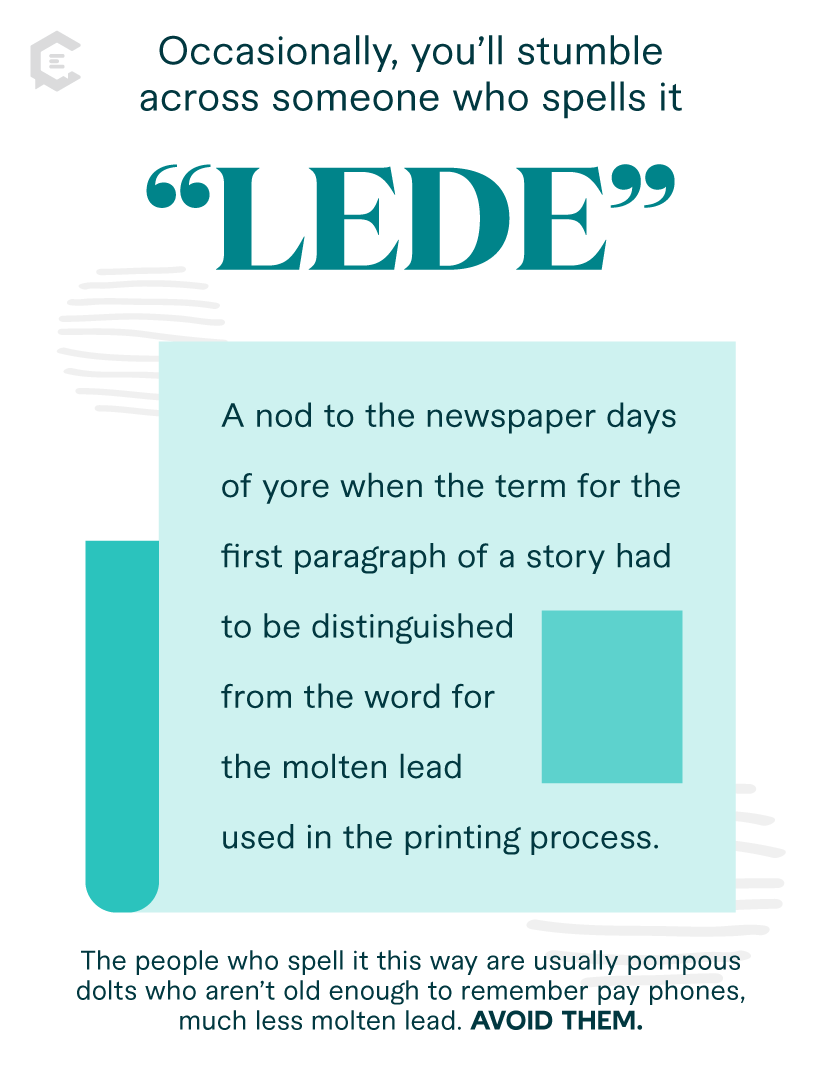

The journalism lead’s main job (I’m personally fond of the nostalgic spelling , “lede,” that derives from the bygone days of typesetting when newspaper folks needed to differentiate the lead of a story from the lead of hot type) is to make the reader want to stay and spend some precious time with whatever you’ve written. It sets the tone and pace and direction for everything that follows. It is the puzzle piece on which the rest of the story depends. To that end, please write your lead first — don’t undermine it by going back and thinking of one to slap on after you’ve finished writing the rest of the story.

Coming up with a good lead is hard. Even the most experienced and distinguished writers know this. No less a writer than John McPhee has called it “ the hardest part of a story to write.” But in return for all your effort, a good lead will do a lot of work for you — most importantly, it will make your readers eager to stay awhile.

There are many different ways to start a story. Some examples of the most common leads are highlighted below. Sometimes they overlap. (Note: These are not terms of art.)

Straight news lead

Just the facts, please, and even better if interesting details and context are packed in. This kind of lead works well for hard news and breaking news.

Some examples:

“After mass street protests in Poland, legislators with the country’s ruling party have abruptly reversed their positions and voted against a proposal to completely ban abortion.” (By NPR’s Camila Domonoske )

“The European Parliament voted Tuesday to ratify the landmark Paris climate accord, paving the way for the international plan to curb greenhouse gas emissions to become binding as soon as the end of this week.” (By NPR’s Rebecca Hersher )

“The United States announced it is suspending efforts to revive a cease-fire in Syria, blaming Russia’s support for a new round of airstrikes in the city of Aleppo.” (By NPR’s Richard Gonzales )

All three leads sum up the news in a straightforward, clear way — in a single sentence. They also hint at the broader context in which the news occurred.

Anecdotal lead

This type of lead uses an anecdote to illustrate what the story is about.

Here’s a powerful anecdotal lead to a story about Brazil’s murder rate and gun laws by NPR’s Lulu Garcia-Navarro :

“At the dilapidated morgue in the northern Brazilian city of Natal, Director Marcos Brandao walks over the blood-smeared floor to where the corpses are kept. He points out the labels attached to the bright metal doors, counting out loud. It has not been a particularly bad night, yet there are nine shooting victims in cold storage.”

We understand right away that the story will be about a high rate of gun-related murder in Brazil. And this is a much more vivid and gripping way of conveying it than if Lulu had simply stated that the rate of gun violence is high.

Lulu also does a great job setting the scene. Which leads us to …

Scene-setting lead

Byrd Pinkerton, a 2016 NPR intern, didn’t set foot in this obscure scholarly haven , but you’d never guess it from the way she draws readers into her story:

“On the second floor of an old Bavarian palace in Munich, Germany, there’s a library with high ceilings, a distinctly bookish smell and one of the world’s most extensive collections of Latin texts. About 20 researchers from all over the world work in small offices around the room.”

This scene-setting is just one benefit of Byrd’s thorough reporting. We even get a hint of how the place smells.

First-person lead

The first-person lead should be used sparingly. It means you, the writer, are immediately a character in your own story. For purists, this is not a comfortable position. Why should a reader be interested in you? You need to make sure your first-person presence is essential — because you experienced something or have a valuable contribution and perspective that justifies conveying the story explicitly through your own eyes. Just make sure you are bringing your readers along with you.

Here, in the spirit of first-personhood, is an example from one of my own stories :

“For many of us, Sept. 11, 2001, is one of those touchstone dates — we remember exactly where we were when we heard that the planes hit the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. I was in Afghanistan.”

On a historic date, I was in a place where very few Americans were present, meaning I’m able to serve as a guide to that place and time. Rather than stating I was in Afghanistan in the first sentence, I tried to draw in readers by reminding them that the memory of Sept. 11 is something many of us share in common, regardless of where we were that day.

Observational lead

This kind of lead steps back to make an authoritative observation about the story and its broader context. For it to work, you need to understand not just the immediate piece you’re writing, but also the big picture. These are useful for stories running a day or more after the news breaks.

Here’s one by the Washington Post’s Karen Tumulty , a political reporter with decades of experience:

“At the lowest point of Donald Trump’s quest for the presidency, the Republican nominee might have brought in a political handyman to sand his edges. Instead, he put his campaign in the hands of a true believer who promises to amplify the GOP nominee’s nationalist message and reinforce his populist impulses.”

And here’s another by NPR’s Camila Domonoske , who knows her literary stuff, juxtaposing the mundane (taxes) with the highbrow (literary criticism):

“Tax records and literary criticism are strange bedfellows. But over the weekend, the two combined and brought into the world a literary controversy — call it the Ferrante Furor of 2016.”

Zinger lead

Edna Buchanan, the legendary, Pulitzer Prize-winning crime reporter for the Miami Herald , once said that a good lead should make a reader sitting at breakfast with his wife “spit out his coffee, clutch his chest and say, ‘My god, Martha. Did you read this?’”

That’s as good a definition as any of a “zinger” lead. These are a couple of Buchanan’s:

“His last meal was worth $30,000 and it killed him.” (A man died while trying to smuggle cocaine-filled condoms in his gut.)

“Bad things happen to the husbands of Widow Elkin.” (Ms. Elkin, as you might surmise, was suspected of bumping off her spouses.)

After Ryan Lochte’s post-Olympic Games, out-of-the-water escapades in Rio, Sally Jenkins, writing in the Washington Post , unleashed this zinger:

“Ryan Lochte is the dumbest bell that ever rang.”

Roy Peter Clark, of the Poynter Institute, deconstructs Jenkins’ column here , praising her “short laser blast of a lead that captures the tone and message of the piece.”

Here are a few notes on things to avoid when writing leads:

- Clichés and terrible puns. This goes for any part of your story, and never more so than in the lead. Terrible puns aren’t just the ones that make a reader groan — they’re in bad taste, inappropriate in tone or both. Here’s one example .

- Long, rambling sentences. Don’t try to cram way too much information into one sentence or digress and meander or become repetitive. Clarity and simplicity rule.

- Straining to be clever. Don’t write a lead that sounds better than it means or promises more than it can deliver. You want your reader to keep reading, not to stop and figure out something that sounds smart but is actually not very meaningful. Here’s John McPhee again: “A lead should not be cheap, flashy, meretricious, blaring: After a tremendous fanfare of verbal trumpets, a mouse comes out of a hole, blinking.”

- Saying someone “could never have predicted.” It’s not an informative observation to say someone “could never have imagined” the twists and turns his or her life would take. Of course they couldn’t! It’s better to give the reader something concrete and interesting about that person instead.

- The weather . Unless your story is about the weather, the weather plays a direct role in it or it’s essential for setting the scene, it doesn’t belong in the lead. Here’s a story about Donald Trump’s financial dealings that would have lost nothing if the first, weather-referenced sentence had been omitted.

One secret to a good lead

Finally, good reporting will lead to good leads. If your reporting is incomplete, that will often show up in a weak lead. If you find yourself struggling to come up with a decent lead or your lead just doesn’t seem strong, make sure your reporting is thorough and there aren’t unanswered questions or missing details and points. If you’ve reported your story well, your lead will reflect this.

Further reading:

- A Poynter roundup of bad leads

- A classic New Yorker story by Calvin Trillin with a great lead about one of Buchanan’s best-known leads.

- A long read by John McPhee , discussing, among other things, “fighting fear and panic, because I had no idea where or how to begin a piece of writing for The New Yorker .” It happens to everyone!

Hannah Bloch is a digital editor for international news at NPR.

Editing & Structure Reporting Writing & Voice

We have a newsletter. Subscribe!

- APPLY ONLINE

- APPOINTMENT

- PRESS & MEDIA

- STUDENT LOGIN

- 09811014536

}}/assets/Images/paytm.jpg)

How to Write a Feature Article: A Step-by-Step Guide

Feature stories are one of the most crucial forms of writing these days, we can find feature articles and examples in many news websites, blog websites, etc. While writing a feature article a lot of things should be kept in mind as well. Feature stories are a powerful form of journalism, allowing writers to delve deeper into subjects and explore the human element behind the headlines. Whether you’re a budding journalist or an aspiring storyteller, mastering the art of feature story writing is essential for engaging your readers and conveying meaningful narratives. In this blog, you’ll find the process of writing a feature article, feature article writing tips, feature article elements, etc. The process of writing a compelling feature story, offering valuable tips, real-world examples, and a solid structure to help you craft stories that captivate and resonate with your audience.

Read Also: Top 5 Strategies for Long-Term Success in Journalism Careers

Table of Contents

Understanding the Essence of a Feature Story

Before we dive into the practical aspects, let’s clarify what a feature story is and what sets it apart from news reporting. While news articles focus on delivering facts and information concisely, feature stories are all about storytelling. They go beyond the “who, what, when, where, and why” to explore the “how” and “why” in depth. Feature stories aim to engage readers emotionally, making them care about the subject, and often, they offer a unique perspective or angle on a topic.

Tips and tricks for writing a Feature article

In the beginning, many people can find difficulty in writing a feature, but here we have especially discussed some special tips and tricks for writing a feature article. So here are some Feature article writing tips and tricks: –

Do you want free career counseling?

Ignite Your Ambitions- Seize the Opportunity for a Free Career Counseling Session.

- 30+ Years in Education

- 250+ Faculties

- 30K+ Alumni Network

- 10th in World Ranking

- 1000+ Celebrity

- 120+ Countries Students Enrolled

Read Also: How Fact Checking Is Strengthening Trust In News Reporting

1. Choose an Interesting Angle:

The first step in feature story writing is selecting a unique and compelling angle or theme for your story. Look for an aspect of the topic that hasn’t been explored widely, or find a fresh perspective that can pique readers’ curiosity.

2. Conduct Thorough Research:

Solid research is the foundation of any feature story. Dive deep into your subject matter, interview relevant sources, and gather as much information as possible. Understand your subject inside out to present a comprehensive and accurate portrayal.

3. Humanize Your Story:

Feature stories often revolve around people, their experiences, and their emotions. Humanize your narrative by introducing relatable characters and sharing their stories, struggles, and triumphs.

4. Create a Strong Lead:

Your opening paragraph, or lead, should be attention-grabbing and set the tone for the entire story. Engage your readers from the start with an anecdote, a thought-provoking question, or a vivid description.

5. Structure Your Story:

Feature stories typically follow a narrative structure with a beginning, middle, and end. The beginning introduces the topic and engages the reader, the middle explores the depth of the subject, and the end provides closure or leaves readers with something to ponder.

6. Use Descriptive Language:

Paint a vivid picture with your words. Utilize descriptive language and sensory details to transport your readers into the world you’re depicting.

7. Incorporate Quotes and Anecdotes:

Quotes from interviews and anecdotes from your research can breathe life into your story. They add authenticity and provide insights from real people.

8. Engage Emotionally:

Feature stories should evoke emotions. Whether it’s empathy, curiosity, joy, or sadness, aim to connect with your readers on a personal level.

Read Also: The Ever-Evolving World Of Journalism: Unveiling Truths and Shaping Perspectives

Examples of Feature Stories

Here we are describing some of the feature articles examples which are as follows:-

“Finding Beauty Amidst Chaos: The Life of a Street Artist”

This feature story delves into the world of a street artist who uses urban decay as his canvas, turning neglected spaces into works of art. It explores his journey, motivations, and the impact of his art on the community.

“The Healing Power of Music: A Veteran’s Journey to Recovery”

This story follows a military veteran battling post-traumatic stress disorder and how his passion for music became a lifeline for healing. It intertwines personal anecdotes, interviews, and the therapeutic role of music.

“Wildlife Conservation Heroes: Rescuing Endangered Species, One Baby Animal at a Time”

In this feature story, readers are introduced to a group of dedicated individuals working tirelessly to rescue and rehabilitate endangered baby animals. It showcases their passion, challenges, and heartwarming success stories.

What should be the feature a Feature article structure?

Read Also: What is The Difference Between A Journalist and A Reporter?

Structure of a Feature Story

A well-structured feature story typically follows this format:

Headline: A catchy and concise title that captures the essence of the story. This is always written at the top of the story.

Lead: A captivating opening paragraph that hooks the reader. The first 3 sentences of any story that explains 5sW & 1H are known as lead.

Introduction : Provides context and introduces the subject. Lead is also a part of the introduction itself.

Body : The main narrative section that explores the topic in depth, including interviews, anecdotes, and background information.

Conclusion: Wraps up the story, offers insights, or leaves the reader with something to ponder.

Additional Information: This may include additional resources, author information, or references.

Read Also: Benefits and Jobs After a MAJMC Degree

Writing a feature article is a blend of journalistic skills and storytelling artistry. By choosing a compelling angle, conducting thorough research, and structuring your story effectively, you can create feature stories that captivate and resonate with your readers. AAFT also provides many courses related to journalism and mass communication which grooms a person to write new articles, and news and learn new skills as well. Remember that practice is key to honing your feature story writing skills, so don’t be discouraged if it takes time to perfect your craft. With dedication and creativity, you’ll be able to craft feature stories that leave a lasting impact on your audience.

What are the characteristics of a good feature article?

A good feature article is well-written, engaging, and informative. It should tell a story that is interesting to the reader and that sheds light on an important issue.

Why is it important to write feature articles?

Feature articles can inform and entertain readers. They can also help to shed light on important issues and to promote understanding and empathy.

What are the challenges of writing a feature article?

The challenges of writing a feature article can vary depending on the topic and the audience. However, some common challenges include finding a good angle for the story, gathering accurate information, and writing in a clear and concise style.

Aaditya Kanchan is a skilled Content Writer and Digital Marketer with experience of 5+ years and a focus on diverse subjects and content like Journalism, Digital Marketing, Law and sports etc. He also has a special interest in photography, videography, and retention marketing. Aaditya writes in simple language where complex information can be delivered to the audience in a creative way.

- Feature Article Writing Tips

- How to Write a Feature Article

- Step-by-Step Guide

- Write a Feature Article

Related Articles

Is Citizen Journalism the Future of News?

Adapting to a Changing Media Landscape 2024

The Impact of Commercial Radio & Scope of Radio Industry in India

The Different Types of News in Journalism: What You Need to Know

Enquire now.

- Advertising, PR & Events

- Animation & Multimedia

- Data Science

- Digital Marketing

- Fashion & Design

- Health and Wellness

- Hospitality and Tourism

- Industry Visit

- Infrastructure

- Mass Communication

- Performing Arts

- Photography

- Student Speak

- 5 Reasons Why Our Fashion Design Course Will Set You Apart May 10, 2024

- Nutrition & Dietetics Course After 12th: Courses Details, Eligibility, and Fee 2024 May 9, 2024

- Fashion Design Courses After 12th: Course Details, Fee, and Eligibility 2024 May 4, 2024

- Film Making Courses After 12th: Course Details, Fees, and Eligibility 2024 May 3, 2024

- The Wellness Wave: Trends in Nutrition and Dietetics Training 2024 April 27, 2024

- Sustainable and Stylish: Incorporating Eco-Friendly Practices in Interior Design Courses April 25, 2024

- Why a Fine Arts Degree is More Than Just Painting Pictures April 24, 2024

- Beyond the Lines: Exploring Creativity and Expression in Fine Arts April 24, 2024

- How Music Classes Can Help You Achieve Your Musical Goals April 23, 2024

- How Artificial Intelligence is Reshaping Animation Production? April 22, 2024

}}/assets/Images/about-us/whatsaap-img-1.jpg)

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

5 Tips for Writing a Great Lead for a News Story

- 5-minute read

- 14th June 2021

A great lead (or “lede”) will set out the key points from a news story in the first lines. This helps to grab readers’ attention, as well as giving them the context they need to understand the story that follows. But how can you write a strong lead for a news or feature article? We have five simple tips to follow:

- Consider the type of lead you want to use for your article.

- Think about the “Five Ws and an H” to pinpoint the key details for your lead.

- Use clear, concise language, avoiding jargon or unnecessary wordiness.

- Resist puns and other newspaper lead clichés.

- Test your lead by reading it out loud to see if it reads smoothly.

For more advice on writing a lead for an article , read on below.

1. Types of Leads

Article leads come in various forms. Three common examples include:

- Summary leads are typically used when writing about current events. As the name indicates, summary leads aim to summarize the key details from a story. Usually, they are no more than one or two sentences long.

- Anecdotal leads are two to three paragraphs long and most common in “feature” articles rather than news stories (e.g., profile or opinion pieces). They work by setting out an anecdote related to the story, helping to make it feel more personal or emotive. This is then followed by a nut graph , where you will explain how the anecdote relates to the main topic of the article.

- Question leads start a story with a question, posed to the reader, about the topic of the article. This would then be followed by a summary.

The key here is to choose a type of lead paragraph that will work best for your news story. Traditionally, news focused stories start with a factual summary lead. Anecdotal and question leads, meanwhile, are great for more personal stories.

2. The Five Ws and H

In journalism, the Five Ws and H refer to six questions you should ask about the story you’re writing. These are also helpful when writing a lead for a story:

- Who is involved or affected? Who will benefit or be harmed?

- What happened? What is the article about in simple terms?

- Where does/did/will it happen? Does the location affect what happened?

- When does/did/will it happen? Is it relevant to the story?

- Why did this happen? Why is it important?

- How did it happen? How does it affect those involved?

Answering the questions above will help you pick out the most important details for the story, which you can then use as the basis for your lead. The story will then cover the other details in the rest of the story, starting with the most relevant points .

Even if you’re not writing a summary lead, considering the Five Ws and H is a good exercise! Picking out the most important details means you can then plan your lead to fit the story, as well as helping you to structure the overall article.

3. Use Clear, Concise Language

Article leads, especially summary leads, need to communicate the key details of a story in as few words as possible. This will usually mean:

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

- Using everyday language rather than jargon or buzzwords.

- Writing in the active voice where possible.

- Keeping sentences short (ideally, no more than 15 to 20 words).

- Avoiding various forms of wordiness .

- Omitting unnecessary details (e.g., if you know your readers will be familiar with the background information on a story, you can leave it out of the lead).

This is essential for summary leads, which may only be a few sentences long. But clear, concise language is valuable no matter what type of lead you’re writing.

4. Resist Puns and Other Clichés

Puns are a common trope in tabloid headlines . It may even be tempting to include one in your lead, but try to resist this urge! If nothing else, puns suggest a lack of seriousness, which could undermine the tone of the rest of the story.

But puns are also a cliché in article leads, so they should be avoided on that count, too. In fact, there are several clichéd leads you might want to avoid, including:

- Dictionary leads (e.g., The dictionary defines X as… )

- Time-related phrases (e.g., Since the beginning of time… )

- “Good news, bad news” leads (e.g., The good news is… )

- “Thanks to” leads (e.g., Thanks to the internet, we now… )

There are occasions where a pun or cliché might be appropriate. But it’s always worth thinking carefully about how such things will affect the tone of your story.

5. Test and Revise Your Lead

Finally, test your lead by reading it out loud. It should read clearly and smoothly. If you find yourself stumbling, look for minor changes you can make to improve it. This might mean cutting a few words or rephrasing the sentence slightly.

Don’t forget, too, that your lead is just part of a story! It is thus wise to revisit your lead once you’ve written the full article and tweak it to fit what you’ve written.

Expert Proofreading Services

If you are writing a news story or article, make sure to get it proofread! Our expert editors can help you polish and perfect your writing – leads and all – so submit a free trial document today to find out how our services work.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

4-minute read

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

How to Ace Slack Messaging for Contractors and Freelancers

Effective professional communication is an important skill for contractors and freelancers navigating remote work environments....

3-minute read

How to Insert a Text Box in a Google Doc

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

How to Write a Lead: 10 Do’s, 10 Don’ts, 10 Good Examples

- Written By Megan Krause

- Updated: November 15, 2023

What is lead writing?

It’s the opening hook that pulls you in to read a story. The lead should capture the essence of the who , what , when , where , why, and how — but without giving away the entire show. A good lead is enticing. It beckons. It promises the reader their time will be well-spent and sets the tone and direction of the piece. All great content starts with a great lead.

Old-school reporting ace and author of ‘The Word: An Associated Press Guide to Good News Writing,’ Jack Cappon, rightly called lead writing “the agony of square one.” A lot if hinging on your lead. From it, readers will decide whether or not they’ll continue investing time and energy into your content or jump ship. And with our culture’s currently short attention spans and patience, if your content doesn’t hook people up front, they’ll bolt. The “back” button is just a thumb tap away.

So, let’s break down the types of leads, which ones you should be writing, and the top 10 do’s and don’ts. We’ll get you hooking customers in no time.

Two Types of Leads

There are two main types of leads and many, many variations thereof. These are:

The summary lead

Most often found in straight news reports, this is the trusty inverted-pyramid lead we learned about in Journalism 101. It sums up the situation succinctly, giving the reader the most important facts first. In this type of lead, you want to determine which aspect of the story — who, what, when, where, why, and how — is most important to the reader and present those facts.

An alleged virgin gave birth to a son in a barn just outside of Bethlehem last night. Claiming a celestial body guided them to the site, magi attending the birth say the boy will one day be king. Herod has not commented.

A creative or descriptive lead

This can be an anecdote, an observation, a quirky fact, or a funny story, among other things. Better suited to feature stories and blog posts, these leads are designed to pique readers’ curiosity and draw them into the story. If you go this route, make sure to provide broader detail and context in the few sentences following your lead. A creative lead is great — just don’t make your reader hunt for what the story’s about much after it.

Mary didn’t want to pay taxes anyway.

A note about the question lead. A variation of the creative lead, the question lead is just what it sounds like: leading with a question. Most editors (myself included) don’t like this type of lead. It’s lazy writing. People are reading your content to get answers, not to be asked anything. It feels like a cop-out, like a writer couldn’t think of a compelling way to start the piece. Do you want to learn more about the recent virgin birth? Well duh, that’s why I clicked in here in the first place.

Is there no exception? Sure there is. If you can make your question lead provocative, go for it — Do you think you have it bad? This lady just gave birth in a barn — just know that this is accomplished rarely.

Which Type of Lead Should You Write?

This depends on a few factors. Ask yourself:

Who is your audience?

Tax attorneys looking for recent changes in the law don’t want to wade through your witty repartee about the IRS, just as millennials searching for craft beer recipes don’t want to read a technical discourse on the fermentation process. Tailor your words to those reading the post.

Where will this article be published?

Match the site’s tone and language. There are some things you can get away with on Vice.com that would be your demise on the Chronicle of Higher Education .

What are you writing about?

Certain topics naturally lend themselves to creativity, while others beg for a “Just the facts, ma’am” presentation. Writing about aromatherapy for a yoga blog gives you a little more leeway than writing about investment tips for a retirement blog.

Lead Writing: Top 10 do’s

1. determine your hook..

Look at the 5 Ws and 1 H. Why are readers clicking on this content? What problem are they trying to solve? What’s new or different? Determine which aspects are most relevant and important, and lead with that.

2. Be clear and succinct.

Simple language is best. Mark Twain said it best: “Don’t use a five-dollar word when a fifty-cent word will do.”

3. Write in the active voice.

Use strong verbs and decided language. Compare “Dog bites man” to “A man was bitten by a dog” — the passive voice is timid and bland (for the record, Stephen King feels the same way).

4. Address the reader as “you.”

This is the writer’s equivalent to breaking the fourth wall in theatre, and while some editors will disagree with me on this one, we stand by it. People know you’re writing to them. Not only is it OK to address them as such, we think it helps create a personal connection with them.

5. Put attribution second.

What’s the nugget, the little gem you’re trying to impart? Put that information first, and then follow it up with who said it. The “according to” part is almost always secondary to what he or she actually said.

6. Go short and punchy.

Take my recent lead for this Marketing Land post : “Freelance writers like working with me. Seriously, they do.” Short and sweet makes the reader want to know where you’re going with that.

7. If you’re stuck, find a relevant stat.

If you’re trying to be clever or punchy or brilliant, and it’s just not happening, search for an interesting stat related to your topic and lead with that. This is especially effective if the stat is unusual or unexpected, as in, “A whopping 80 percent of Americans are in debt.”

8. Or, start with a story.

If beginning with a stat or fact isn’t working for your lead, try leading with an anecdote instead. People absorb data, but they feel stories. Here’s an example of an anecdotal lead that works great in a crime story: “It’s just after 11 p.m., and Houston police officer Al Leonard has his gun drawn as the elderly black man approaches the patrol car. The 9mm pistol is out of sight, pointing through the car door. Leonard rolls down his window and casually greets the man. ‘What can I do for you?'” You want to know what happens next, don’t you?

9. Borrow this literary tactic.

Every good story has these three elements : a hero we relate to, a challenge (or villain) we fear, and an ensuing struggle. Find these elements in the story you’re writing and lead with one of those.

10. When you’re staring at a blank screen.

Just start. Start writing anything. Start in the middle of your story. Once you begin, you can usually find your lead buried a few paragraphs down in this “get-going” copy. Your lead is in there — you just need to cut away the other stuff first.

Lead Writing: Top 10 don’ts

1. don’t make your readers work too hard..

Also known as “burying the lead,” this happens when you take too long to make your point. It’s fine to take a little creative license, but if readers can’t figure out relatively quickly what your article is about, they’ll bounce.

2. Don’t try to include too much.

Does your lead contain too many of the 5 Ws and H? Don’t try to jam everything in there — you’ll overwhelm the reader.

3. Don’t start sentences with “there is” or “there are” constructions.

It’s not wrong, but similar to our question lead, it’s lazy, boring writing.

4. Don’t be cliche.

We beg of you .

5. Don’t have any errors.

Include typos or grammatical errors, and it’s game over — you’ve lost the reader.

6. Don’t say anything is “right around the corner.”

Just trust us. We’ve seen it used way too much. “Valentine’s Day is right around the corner,” “The first day of school is right around the corner,” Mother’s Day sales are right around the corner” … Zzzz. Boring .

7. Don’t make puns. Even ironically.

It’s an old example but it proves the point. From a Huffington Post story about a huge swastika found painted on the bottom of a swimming pool in Brazil: “Authorities did Nazi this coming.” Boo. Absolutely not. Don’t make the reader groan.

8. Don’t state the obvious.

Don’t tell readers what they already know. We call it “water is wet” writing. Some examples: “The internet provides an immense source of useful information.” “Today’s digital landscape is moving fast.” Really! You don’t say?

9. Don’t cite the dictionary.

“Merriam-Webster defines marketing as…” This is the close cousin of “water is wet” writing. It’s a better tactic for essay-writing middle-schoolers. Don’t do this.

10. Don’t imagine anything. You are not John Lennon.

“Imagine a world where everyone recycled,” “Imagine how good it must feel to save a life,” “Imagine receiving a $1,000 tip from your favorite customer on Christmas Eve.” Imagine we retired this hackneyed, worn-out lead.

10 Worthy Examples of Good Lead Writing

1. short and simple..

Edna Buchanan, the Pulitzer Prize-winning crime reporter for The Miami Herald, wrote a story about an ex-con named Gary Robinson. One drunken night in the ‘80s, Robinson stumbled into a Church’s Chicken, where he was told there was no fried chicken, only nuggets. He decked the woman at the counter, and in the ensuing melee, he was shot by a security guard. Buchanan’s lead:

Gary Robinson died hungry.

2. Ooh, tell me more.

A 2010 piece in the New York Times co-authored by Sabrina Tavernise and Dan Froschjune begins:

An ailing, middle-age construction worker from Colorado, on a self-proclaimed mission to help American troops, armed himself with a dagger, a pistol, a sword, Christian texts, hashish and night-vision goggles and headed to the lawless tribal areas near the border of Afghanistan and Pakistan to personally hunt down Osama bin Laden.

3. Meanwhile, at San Quentin.

From the 1992 story titled, “After Life of Violence Harris Goes Peacefully,” written by Sam Stanton for The Sacramento Bee:

In the end, Robert Alton Harris seemed determined to go peacefully, a trait that had eluded him in the 39 violent and abusive years he spent on earth.

Remember Olympic jerk Ryan Lochte, the American swimmer who lied to Brazilian authorities about being robbed at gunpoint while in Rio for 2016 games? Sally Jenkins’ story on Lochte for The Washington Post begins:

Ryan Lochte is the dumbest bell that ever rang.

5. An oldie but man, what a goodie.

This beautiful lead is from Shirley Povich’s 1956 story in The Washington Post & Times Herald about a pitcher’s perfect game:

The million‑to‑one shot came in. Hell froze over. A month of Sundays hit the calendar. Don Larsen today pitched a no-hit, no‑run, no‑man‑reach‑first game in a World Series.

6. Dialogue lead.

Diana Marcum wrote this compelling lead for the Los Angeles Times , perfectly capturing the bleakness of the California drought in 2014:

The two fieldworkers scraped hoes over weeds that weren’t there. “Let us pretend we see many weeds,” Francisco Galvez told his friend Rafael. That way, maybe they’d get a full week’s work.

7. The staccato lead.

Ditto; we found this one in an online journalism quiz , but can’t track the source. It reads like the first scene of a movie script:

Midnight on the bridge… a scream… a shot… a splash… a second shot… a third shot. This morning, police recovered the bodies of Mr. and Mrs. R. E. Murphy, estranged couple, from the Snake River. A bullet wound was found in the temple of each.

8. Hey, that’s us.

Sure, we’ll include our own former Dear Megan column railing against exclamation points:

This week’s question comes to us from one of my kids, who will remain nameless because neither wants to appear in a dorky grammar blog written by their uncool (but incredibly good-looking) mom. I will oblige this request for anonymity because, despite my repeated claims about how lucky they are to have me, apparently I ruin their lives on a semi-regular basis. Why add to their torment by naming them here? I have so many other ways I’d rather torment them.

9. The punch lead.

From numerous next-day reports following the Kennedy assassination:

The president is dead.

10. Near perfection.

Finally, this lead comes from a 1968 New York Times piece written by Mark Hawthorne. It was recently featured in the writer’s obituary :

A 17-year-old boy chased his pet squirrel up a tree in Washington Square Park yesterday afternoon, touching off a series of incidents in which 22 persons were arrested and eight persons, including five policemen, were injured.

Time to Put That Lead Writing to Good Use

Alright, now that you’ve read this article, you’re going to be hooking readers left and right with captivating leads. What’s next? Well, if you want to showcase your new skills while working with top brands, join our Talent Network . We’ll match you with companies that fit your talent and expertise to take your career to the next level.

Stay in the know.

We will keep you up-to-date with all the content marketing news and resources. You will be a content expert in no time. Sign up for our free newsletter.

Elevate Your Content Game

Transform your marketing with a consistent stream of high-quality content for your brand.

You May Also Like...

The Strategic Ensemble Behind Effective Content

Everything to Know About the Power of SEO Personalization

Personalized Content Strategies: Gaining the Competitive Edge

- Content Production

- Build Your SEO

- Amplify Your Content

- For Agencies

Why ClearVoice

- Talent Network

- How It Works

- Freelance For Us

- Statement on AI

- Talk to a Specialist

Get Insights In Your Inbox

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Intellectual Property Claims

- Data Collection Preferences

CURATE YOUR FUTURE

My weekly newsletter “Financialicious” will help you do it.

In This Post:

How to write a lead: 9 ways to nail your opening.

The lead, also spelled lede, is the all-important opening of your article. Here’s what to know.

The lead can refer to an opening section, paragraph, or sentence of a written piece.

I enrolled in night school at UCLA because I wanted to develop my skills with something other than an online course. I’m a little burnt out on online courses and the funnels that sell them. I’ve been buying courses for eight years and not finishing them for nine. And I felt ready to learn from more seasoned experts — professors and editors who had decades of experience under their belts.

The UCLA night school building sits on the edge of campus in Westwood, about half a mile from the intersection of Sepulveda and Santa Monica boulevards. When I showed up to class, I sat alongside a dozen other adults ranging in age from 19 to 65 as our teacher handed out the first writing exercise.

“This is the most important skill you will learn in journalism school,” he said.

The assignment was to write a lead. Sometimes misspelled “lede” for journalism shorthand, a lead is a single sentence, paragraph, or section that summarizes the who, what, where, when, why, and how of your story.

Think of leads as being like movie trailers. You get a sense of what the movie is about, yet the teaser leaves you wanting more. There are also many variations on the lead — there is something for everyone.

Headlines are vital for successful content marketing , but to keep readers or viewers intrigued, you need a great lead, too. Here’s how this classic journalism technique can help you reach your goals.

Table of Contents

What is a lead (lede), types of leads for writing online, how to write a lead: best practices to consider, when should you write the lead for your news story, practice writing great leads today.

Before delving into the intricacies of a lead, it’s crucial to understand its purpose.

The lead is the opening paragraph or sentence of an article, designed to capture readers’ attention and entice them to continue reading. A well-crafted lead sets the tone for the rest of your writing and serves as a guide for the reader, highlighting the main points and generating curiosity.

In news, a lede serves readers by communicating what they need to know about current events. Marketers can benefit from this skill, too.

A lede will help you do the following:

- Reduce bounce rate. Readers will be less likely to dip out after just a few seconds, and may explore other pages on your website.

- Increase time on page. The longer readers stay on a page, the better it is for SEO. Time on page is a common quality metric in corporate media.

- Feed your sales funnel. Ledes aren’t just for articles; their logic applies to video scripts and sales pages, too. If readers hang around, you’re doing something right.

(For clarity, this definition of lead is different than a marketing lead — someone who has entered your sales funnel — and is distinct from the word lead as other parts of speech, such as “lead me to the nearest food truck, please.” 🌮)

Although there’s no one correct way to write a lead, some approaches are better than others based on the type of article. Journalists learn a core set of leads in year one to attract and engage readers. Here are nine different lead styles to know about.

Limited-Time Offer: ‘Pitching Publications 101’ Workshop

Get the ‘Pitching Publications 101’ Workshop and two other resources as part of the Camp Wordsmith® Sneak Peek Bundle , a small-bite preview of my company's flagship publishing program. Offer expires one hour from reveal.

- Summary lead / straight news lead.

- Single-item lead.

- Anecdotal lead / analogous lead.

- Delayed identification lead.

- Scene-setting lead.

- Short sentence lead / zinger lead.

- First-person lead.

- Observational lead.

- Question lead.

@nickwolny1 Amazon/iRobot Deal Called Off Due to Regulation - Jan. 29, 2023: Amazon will pay a $94 million termination fee to abandon its purchase of Roomba maker iRobot. Was this the right move? Here’s what to know. In 2022, Amazon announced they were acquiring iRobot, maker of the Roomba vacuum and other products, for $1.7 billion. But since then, the deal has been mired by antitrust regulators in the EU, who are blocking the deal on grounds that it gives Amazon too much marketplace control, as they could delist or degrade access to competitors. Antitrust regulators ensure mergers and acquisitions don’t result in monopolies. Market competition keeps product prices down, which is better for consumers. In response, iRobot announced today they would lay off 31% of staff, about 350 employees. iRobot made $891 million in revenue in 2023, but ended at around a $275 million loss. In a joint statement, Amazon and iRobot said there was “no path to regulatory approval for the deal.” Should Amazon have been able to acquire iRobot? #news #journalist #journalism #amazon #smarthome #newsanchor #technews #regulation #europeanunion #vacuum #acquisition #layoffs ♬ original sound - Nick Wolny | News Journalist

In this TikTok, I use a lead sentence to get the point across quickly.

No. 1: Summary Lead / Straight News Lead

Of all the types of leads summary lead is the most common. It’s very popular when writing about hard news or breaking news, and if you’re new to writing, you can’t go wrong with a summary lead. This approach is also called a news lead or a direct lead.

Hannah Block, international news editor for National Public Radio (NPR), describes it well: “Just the facts, please, and even better if interesting details and context are packed in.”

The summary lead formula is simple: aspire to communicate most of the who, what, where, when, why, and how of your story (referred to hereafter as “the W’s”) in a single sentence.

This approach is preferred in news writing, which aspires to remain neutral and unbiased in its delivery of information, and creates immediate clarity. Prioritize active voice, journalistic writing, and proper AP style in a summary lead.

Here is an example from the Associated Press (AP).

“Intensifying its fight against high inflation, the Federal Reserve raised its key interest rate by a substantial three-quarters of a point for a third straight time and signaled more large rate hikes to come — an aggressive pace that will heighten the risk of an eventual recession.” ( 1 )

AP’s business section has a “business highlights” subsection in which each article is a collection of leads and summary paragraphs. Read through it to get a feel for how to create clarity and context in a single paragraph that includes the most important information. AP News is free to read.

Here’s another example from Reuters:

“The Philadelphia Phillies ended their long wait for a World Series title with a short burst of baseball last night as they clinched the crown by completing a rain-suspended 4-3 win over the Tampa Bay Rays.” ( 2 )

No. 2: Single-Item Lead

The single-item lead is similar to the summary lead, but this approach focuses just one or two of the W’s, rather than trying to stuff most or all of them into a single sentence.

This approach is good if your news story or article is very much driven by one particular detail or feeling, and since it’s shorter, it usually results in a bigger punch. Aim to land your idea in as few words as possible, preferably all in one sentence.

Let's rewrite the previous Reuters lead to demonstrate how it could be expressed as a single-item lead instead.

“The Philadelphia Phillies are World Champions again.”

No. 3: Anecdotal Lead / Analogy Lead

If the information you’re introducing to your audience is complex or overly conceptual, a more effective approach might be to use an analogy or anecdote instead.

The anecdotal lead is unique in that it does not communicate the W’s of the story, but rather leans on details or analogies to help the reader infer what the story is going to be about. The result is a more emotionally charged or stylistic lead that goes beyond hard facts and can pull readers in.

Pro Tip : An anecdote is any short story that illustrates a point.

These leads can use an overt analogy or be more descriptive. Here are examples of each.

The Cincinnati Post

“From Dan Ralescu’s sun-warmed beach chair in Thailand, the Indian Ocean began to look, oddly, not so much like waves but bread dough.”

ProPublica/The New York Times

“"I tucked Joel in, but I feel so guilty I didn’t hold him longer,” Julie Rea said, her voice welling with emotion. That is all she can muster about the worst night of her life. As she tries to say more, she breaks down." ( 3 )

Resist the urge to use an anecdotal lead that is too cheesy or cliché. The objective of this lead is to use an anecdote to create depth and intrigue.

No. 4: Delayed Identification Lead

This lead focuses on an action or situation without revealing who is involved at first. It is good to use when someone wants to emphasize a scenario or situation effectively before revealing the W’s. When done well, it pulls people in.

In the first debate for the United States Democratic Primary in 2020, Kamala Harris used a delayed-identification lead in one of her talking points on busing legislation to great effect.

“There was a little girl in California who was part of the second class to integrate their public schools, and she was bused to school every day. That little girl was me.”

No. 5: Scene-Setting Lead

The scene-setting lead creates depth and detail. It is more lush and narrative, and is great for creating vividness or setting the stage for longer pieces.

Usually, the primary intention of the lead is to establish clarity quickly, but in literary journalism and other more longform approaches, taking the time to set the stage at the beginning often results in a more effective piece.

Here is an example of a scene-setting lead from BuzzFeed.

“For seven years before the murder, Dee Dee and Gypsy Rose Blancharde lived in a small pink bungalow on West Volunteer Way in Springfield, Missouri. Their neighbors liked them. “'Sweet' is the word I’d use,” a former friend of Dee Dee’s told me not too long ago. Once you met them, people said, they were impossible to forget.” ( 4 )

Here is another example, a sentence from the book Beloved by Toni Morrison.

“Winter in Ohio was especially rough if you had an appetite for color. Sky provided the only drama, and counting on a Cincinnati horizon for life’s principal joy was reckless indeed.”

No. 6: Short Sentence Lead / Zinger Lead

This type of lead is when you pack a punch with the first sentence of your article to capture a reader’s attention. It can be sassy, shocking, unexpected, compelling, or all of the above.

Usually, when using a zinger lead, the following paragraphs fill in missing details and function like a regular lead.

Here is a sassy example from the Philadelphia Enquirer.

“Philadelphians don’t need anyone’s approval, especially not New Yorkers. But that doesn’t mean we don’t care when we get recognition.” ( 5 )

Here is another example from the Miami Herald. This was a story about a man who attempted to smuggle cocaine by swallowing balloons of it.

“His last meal was worth $30,000 and it killed him.” ( 6 )

No. 7: First-Person Lead

A first-person lead is the battle ax of many a mom blogger or aspiring opinion columnist. First-person leads are fine for blogging, and they’ve become increasingly popular in our social media-first culture.

However, they also break the fourth wall; if you’re writing a journalistic article or reporting, introducing yourself as a character in your story may be a risk.

Remember, the main goal of a lead is to get a point across quickly. If your personal experience doesn’t contribute to that goal, readers won’t understand what they’re reading, and they’ll check out.

Here is an example from a story by National Public Radio (NPR).

“For many of us, Sept. 11, 2001, is one of those touchstone dates — we remember exactly where we were when we heard that the planes hit the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. I was in Afghanistan.” ( 7 )

No. 8: Observational Lead

In an observational lead, you project authority by talking about an issue at hand and relating the information back to the big picture.

Observational leads usually aren’t used for breaking news, and they focus more on giving overall context to a situation, rather than just basic facts. They’re a great opportunity to share your perspective, industry savvy, or writing style.

Here are the opening two sentences of a feature from The New York Times that leveraged the observational lead.

“In 2018, senior executives at one of the country’s largest nonprofit hospital chains, Providence, were frustrated. They were spending hundreds of millions of dollars providing free health care to patients. It was eating into their bottom line.” ( 8 )

No. 9: Question Lead

A question lead uses question format to create curiosity and intrigue. Since a question lead is not providing details, the second paragraph of your piece will need to pull extra weight and deliver missing details.

Ensure you have this one-two punch in place so that the rhythm of your article reads properly.

Here's a terrific question lead from an article in The Las Vegas Sun.

“What’s increasing faster than the price of gasoline? Apparently, the cost of court lobbyists.

District and Justice Court Judges want to hire lobbyist Rick Loop for $150,000 to represent the court system in Carson City through the 2009 legislative session. During the past session, Loop’s price tag was $80,000.” ( 9 )

Question leads are also popular in SEO writing , especially questions addressed directly to the reader. Most search engine traffic is people with intent who are trying to have their questions answered; this approach is an easier way to hook readers, but it is sometimes considered low-brow.

Let's look at a question lead from Social Media Examiner that followed this format.

“Are you using TikTok or Instagram for business? Looking for a content strategy that works and won’t leave you exhausted?

In this article, you’ll discover a three-step strategy to create highly engaging TikTok and Instagram content that will scale your audience while helping you avoid burnout.” ( 10 )

Come Up With a Good Hook

To write an effective lead, begin with a strong hook that instantly grabs your readers' attention.

Consider using a thought-provoking question, a surprising fact, or an engaging anecdote that relates to the topic. The key is to make your readers curious and eager to find out more.

For example, if you're writing an article about the benefits of exercise, you could start your lead with a captivating question like, "Did you know that just 30 minutes of daily exercise can add years to your life?"

Related: How to Write Powerful Headlines

Know Your Audience

Understanding your target audience is essential to create a lead that resonates well. Consider your readers’ demographics, interests, and motivations.

For instance, if you are writing a lead for a tech-savvy audience, you may want to start with a powerful statistic or a cutting-edge technological breakthrough. On the other hand, if your audience consists of beginners, you could begin with a relatable storytelling approach to ease them into the topic.

Tailoring your lead to the specific interests of your readers will increase their engagement and make them more likely to continue reading. This is a core concept of positioning.

Keep It Short and Concise

In our fast-paced digital age, attention spans are shrinking. To capture your readers' interest and keep them engaged, keep your lead short and concise.

Use clear and concise language to convey your message effectively. Long-winded leads tend to lose readers' interest quickly, so aim for brevity.

Pro Tip : Avoid unnecessary jargon or complex sentences that may confuse or bore your audience. Instead, focus on making your point succinctly and compellingly.

Use Keywords Strategically

In today's digital landscape, search engine optimization (SEO) is a crucial element in writing leads. Strategic placement of relevant keywords helps search engines recognize the relevance of your content and boost its visibility in search results.

When writing your lead, identify the primary keyword or key phrase that represents your topic. For instance, if you're writing an article on budget travel tips, the primary keyword may be "budget travel." Integrate the keyword naturally in your lead to make it more search-engine-friendly and increase your chances of attracting organic traffic.

Limited-Time Offer: ‘The Medium Workshop’

Get The Medium Workshop and two other resources as part of the Camp Wordsmith® Sneak Peek Bundle , a small-bite preview of my company's flagship publishing program. Offer expires one hour from reveal.

Consider writing your lead first, then editing your lead last.

The lead will give you a running start, and is usually one of the first things you will write when you sit down in front of a blank page. However, since the lead needs to accurately capture the essence of your article, it’s helpful to have the rest of your piece developed before attempting to summarize it.

Leads are surprisingly challenging to write, but when done well, they make an article sing.

When you’re able to communicate a message quickly — whether it be yours or someone else’s — your words will reach more people and make a bigger impact in the long run. ◆

Thanks For Reading 🙏🏼

Keep up the momentum with one or more of these next steps:

💬 Leave a comment below. Let me know a takeaway or thought you had from this post.

📣 Share this post with your network or a friend. Sharing helps spread the word, and posts are formatted to be both easy to read and easy to curate – you'll look savvy and informed.

📲 Follow on another platform. I'm active on Medium, Instagram, and LinkedIn ; if you're on any of those, say hello.

📬 Sign up for my free email list. “The Morning Walk” is a free newsletter about commerce, technology, and personal entrepreneurship. Learn more and browse past editions here .

🏕 Up your writing game. Camp Wordsmith® is a content marketing strategy program for small business owners, service providers, and online professionals. Learn more here.

📊 Hire me for consulting. I provide 1-on-1 consultations through my company, Hefty Media Group. We're a certified diversity supplier with the National Gay & Lesbian Chamber of Commerce. Learn more here.

Welcome to the blog. Nick Wolny is a writer, editor and copy consultant based in Los Angeles.

- Follow us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Criminal Justice

- Environment

- Politics & Government

- Race & Gender

Expert Commentary

Feature writing: Crafting research-based stories with characters, development and a structural arc

Semester-long syllabus that teaches students how to write stories with characters, show development and follow a structural arc.

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

by The Journalist's Resource, The Journalist's Resource January 22, 2010

This <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org/home/syllabus-feature-writing/">article</a> first appeared on <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org">The Journalist's Resource</a> and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.<img src="https://journalistsresource.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cropped-jr-favicon-150x150.png" style="width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;">

The best journalism engages as it informs. When articles or scripts succeed at this, they often are cast as what is known as features or contain elements of a story. This course will teach students how to write compelling feature articles, substantive non-fiction stories that look to a corner of the news and illuminate it, often in human terms.

Like news, features are built from facts. Nothing in them is made up or embellished. But in features, these facts are imbedded in or interwoven with scenes and small stories that show rather than simply tell the information that is conveyed. Features are grounded in time, in place and in characters who inhabit both. Often features are framed by the specific experiences of those who drive the news or those who are affected by it. They are no less precise than news. But they are less formal and dispassionate in their structure and delivery. This class will foster a workshop environment in which students can build appreciation and skill sets for this particular journalistic craft.

Course objective

To teach students how to interest readers in significant, research-based subjects by writing about them in the context of non-fiction stories that have characters, show development and follow a structural arc from beginning to end.

Learning objectives

- Explore the qualities of storytelling and how they differ from news.

- Build a vocabulary of storytelling.

- Apply that vocabulary to critiquing the work of top-flight journalists.

- Introduce a writing process that carries a story from concept to publication.

- Introduce tools for finding and framing interesting features.

- Sharpen skills at focusing stories along a single, clearly articulated theme.

- Evaluate the importance of backgrounding in establishing the context, focus and sources of soundly reported stories.

- Analyze the connection between strong information and strong writing.

- Evaluate the varied types of such information in feature writing.

- Introduce and practice skills of interviewing for story as well as fact.

- Explore different models and devices for structuring stories.

- Conceive, report, write and revise several types of feature stories.

- Teach the value of “listening” to the written word.

- Learn to constructively critique and be critiqued.

- Examine markets for journalism and learn how stories are sold.

Suggested reading

- The Art and Craft of Feature Writing , William Blundell, Plume, 1988 (Note: While somewhat dated, this book explicitly frames a strategy for approaching the kinds of research-based, public affairs features this course encourages.)

- Writing as Craft and Magic (second edition), Carl Sessions Stepp, 2007, Oxford University Press.

- On Writing Well (30th anniversary edition), William Zinsser, Harper Paperbacks, 2006.

- The Associated Press Stylebook 2009 , Associated Press, Basic Books, 2009.

Recommended reading

- America’s Best Newspaper Writing , edited by Roy Peter Clark and Christopher Scanlan, Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2006.

- Writing for Story , Jon Franklin, Penguin, 1986.

- Telling True Stories: A Nonfiction Writers’ Guide from the Nieman Foundation at Harvard University , edited by Mark Kramer and Wendy Call, Plume, 2007.

- The Journalist and the Murderer , Janet Malcolm, Vintage, 1990.

- Writing for Your Readers , Donald Murray, Globe Pequot, 1992.

Assignments

Students will be asked to write and report only four specific stories this semester, two shorter ones, one at the beginning of the semester and one at the end, and two longer ones, a feature looking behind or beyond a news development, and an institutional or personal profile.

They will, however, be engaged in substantial writing, much of it focused on applying aspects of the writing-process method suggested herein. Throughout the class, assignments and exercises will attempt to show how approaching writing as a process that starts with a story’s inception can lead to sharper story themes, stronger story reporting and more clearly defined story organization. As they report and then revise and redraft the semester’s two longer assignments, students will craft theme or focus statements, write memos that help the class troubleshoot reporting weaknesses, outline, build interior scenes, workshop drafts and workshop revisions. Finally, in an attempt to place at least one of their pieces in a professional publication, an important lesson in audience and outlet, the students will draft query letters.

Methodology

This course proceeds under the assumption that students learn to report and write not only through practice (which is essential), but also by deconstructing and critiquing award-winning professional work and by reading and critiquing the work of classmates.

These workshops work best when certain rules are established:

- Every student will read his or her work aloud to the class at some point during the semester. It is best that these works be distributed in advance of class.

- Every student should respond to the work honestly but constructively. It is best for students to first identify what they like best about a story and then to raise questions and suggestions.

- All work will be revised after it is workshopped.

Weekly schedule and exercises (13-week course)

We encourage faculty to assign students to read on their own at least the first 92 pages of William Zinsser’s On Writing Well before the first class. The book is something of a contemporary gold standard for clear, consistent writing and what Zinsser calls the contract between writer and reader.

The assumption for this syllabus is that the class meets twice weekly.

Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | Week 6 | Week 7 Week 8 | Week 9 | Week 10 | Week 11 | Week 12 | Week 13

Week 1: What makes feature stories different?

Previous week | Next week | Back to top

Class 1: News reports versus stories

The words “dispassionate,” “factual” and “front-loaded” might best describe the traditional news story. It is written to convey information quickly to the hurried reader. Features, on the other hand, are structured and told so that readers engage in and experience a story — with a beginning, middle and end — even as they absorb new information. It is features that often are the stories emailed to friends or linked on their Facebook pages. Nothing provides more pleasure than a “good read” a story that goes beyond basic information to transport audiences to another place, to engage an audience in others’ lives, to coax a smile or a tear.

This class will begin with a discussion of the differences in how journalists approach both the reporting and writing of features. In news, for example, reporters quote sources. In features, they describe characters, sometimes capturing their interaction through dialogue instead of through disembodied quotes. Other differences between news and story are summarized eloquently in the essays “Writing to Inform, Writing to Engage” and “Writing with ‘Gold Coins'” on pages 302 to 304 of Clark and Scanlan’s America’s Best Newspaper Writing . These two essays will be incorporated in class discussion.

The second part of the introductory class will focus on writing as a continuum that begins with the inception of an idea. In its cover blurb, William Blundell’s book is described as “a step-by-step guide to reporting and writing as a continuous, interrelated process.”

Notes Blundell: “Before flying out the door, a reporter should consider the range of his story, its central message, the approach that appears to best fit the tale, and even the tone he should take as a storyteller.” Such forethought defines not only how a story will be reported and written but the scope of both. This discussion will emphasize that framing and focusing early allows a reporter to report less broadly and more deeply, assuring a livelier and more authoritative story.

READING (assignments always are for the next class unless otherwise noted):

- Blundell, Chapter 1

- Clark/Scanlan, “The Process of Writing and Reporting,” pages 290-294.

ASSIGNMENT:

Before journalists can capture telling details and create scenes in their feature stories, they need to get these details and scenes in their notebooks. They need, as Blundell says, to be keen observers “of the innocuous.” In reporting news, journalists generally gather specific facts and elucidating quotes from sources. Rarely, however, do they paint a picture of place, or take the time to explore the emotions, the motives and the events that led up to the news. Later this semester, students will discuss and practice interviewing for story. This first assignment is designed to make them more aware of the importance of the senses in feature reporting and, ultimately, writing.

Students should read the lead five paragraphs of Hal Lancaster’s piece on page 56 of Blundell and the lead of Blundell’s own story on page 114. They should come prepared to discuss what each reporter needed to do to cast them, paying close attention to those parts based on pure observation and those based on interviewing.

Finally, they should differentiate between those parts of the lead that likely were based on pure observation and those that required interviewing and research. This can be done in a brief memo.

Class 2: Building observational and listening skills

Writing coach Don Fry, formerly of the Poynter Institute, used the term “gold coins” to describe those shiny nuggets of information or passages within stories that keep readers reading, even through sections based on weighty material. A gold coin can be something as simple as a carefully selected detail that surprises or charms. Or it can be an interior vignette, a small story within a larger story that gives the reader a sense of place or re-engages the reader in the story’s characters.

Given the feature’s propensity to apply the craft of “showing” rather than merely “telling,” reporters need to expand their reporting skill set. They need to become keen observers and listeners, to boil down what they observe to what really matters, and to describe not for description’s sake but to move a story forward. To use all the senses to build a tight, compelling scene takes both practice and restraint. It is neither license to write a prose-poem nor to record everything that’s seen, smelled or heard. Such overwriting serves as a neon exit sign to almost any reader. Yet features that don’t take readers to what Blundell calls “street level” lack vibrancy. They recount events and measure impact in the words of experts instead of in the actions of those either affected by policy, events or discovery of those who propel it.

In this session, students will analyze and then apply the skill sets of the observer, the reporter who takes his place as a fly on the wall to record and recount the scene. First students will discuss the passive observation at the heart of the stories assigned above. Why did the writers select the details they did? Are they the right ones? Why or why not?

Then students will be asked to report for about 30 to 45 minutes, to take a perch someplace — a cafeteria, a pool hall, a skateboard park, a playground, a bus stop — where they can observe and record a small scene that they will be asked to recapture in no more than 150 to 170 words. This vignette should be written in an hour or less and either handed in by the end of class or the following day.

Four fundamental rules apply:

- The student reporters can only write what they observe or hear. They can’t ask questions. They certainly can’t make anything up.

- The students should avoid all opinion. “I” should not be part of this story, either explicitly or implicitly.

- The scene, which may record something as slight as a one-minute exchange, should waste no words. Students should choose words and details that show but to avoid words and details that show off or merely clutter.

- Reporters should bring their lens in tight. They should write, for example, not about a playground but about the jockeying between two boys on its jungle gym.

Reading: Blundell, Chapter 1, Stepp, pages 64 to 67. Students will be assigned to read one or more feature articles built on the context of recently released research or data. The story might be told from the perspective of someone who carried out the research, someone representative of its findings or someone affected by those findings. One Pulitzer Prize-winning example is Matt Richtel’s “Dismissing the Risks of a Deadly Habit,” which began a series for which The New York Times won a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting in 2010. Richtel told of the dangers of cell phones and driving through the experiences of Christopher Hill, a young Oklahoma driver with a clean record who ran a light and killed someone while talking on the phone. Dan Barry’s piece in The Times , “From an Oyster in the Gulf, a Domino Effect,” tells the story of the BP oil spill and its impact from the perspective of one oysterman, placing his livelihood into the context of those who both service and are served by his boat.

- Finish passive observational exercise (see above).

- Applying Blundell’s criteria in Chapter 1 (extrapolation, synthesis, localization and projection), students should write a short memo that establishes what relationship, if any, exists between the features they were assigned to read and the news or research developments that preceded them. They should consider whether the reporter approached the feature from a particular point of view or perspective. If so, whose? If not, how is the story structured? And what is its main theme? Finally, students should try to identify three other ways feature writers might have framed a story based on the same research.

Week 2: The crucial early stages: Conceiving and backgrounding the story

Class 1: Finding fresh ideas

In the first half of class, several students should be asked to read their observed scenes. Writing is meant to be heard, not merely read. After each student reads a piece, the student should be asked what he or she would do to make it better. Then classmates should be encouraged to make constructive suggestions. All students should be given the opportunity to revise.

In the second half of class, students will analyze the origins of the features they were assigned to read. The class might be asked to form teams and to identify other ways of approaching the material thematically by using Blundell’s methods of looking at an issue.

Feature writers, the author writes, are expected to find and frame their own ideas.