Writing Dialogue [20 Best Examples + Formatting Guide]

Have you ever found yourself cringing at clunky dialogue while reading a book or watching a movie? I know I have.

It’s like nails on a chalkboard, completely ruining the experience. But on the flip side, well-written dialogue can transform a story. It’s the magic that makes characters leap off the page, immersing us in their world.

As a writer, I’m fascinated by the mechanics of great dialogue.

So here are 20 of the best examples of writing dialogue that brings your story to life.

Example 1: Dialogue that Reveals Character

Table of Contents

One of the most powerful functions of dialogue is to shed light on your characters’ personalities.

The way they speak – their word choice, tone, even their hesitations – can tell us so much about who they are. Check out this example:

“Look, I ain’t gonna sugarcoat this,” the detective growled, his knuckles whitening as he gripped the chair. “You were spotted leaving the scene, and the murder weapon’s got your prints all over it.”

Without any lengthy description, we get a sense of this detective as a no-nonsense, direct type of guy.

Example 2: Dialogue that Builds Tension

Dialogue can become this amazing tool to ratchet up the tension in a scene.

Short, clipped exchanges and carefully placed silences can leave the reader on the edge of their seat.

Here’s how it might play out:

“Do you hear that?” Sarah whispered. “Hear what?” A scratching noise echoed from the attic. Sarah’s eyes widened. “It’s coming back.”

The suspense is killing me just writing that!

Example 3: Dialogue that Drives the Plot

Conversations aren’t just about characters sitting around and chatting.

Great dialogue should actively push the story forward. It can set up a conflict, reveal key information, or change the course of events.

Take a look at this:

“I’ve made my decision,” the king declared, the crown heavy on his brow. “We go to war.”

A single line, and the whole trajectory of the story shifts.

Formatting Tips: The Basics

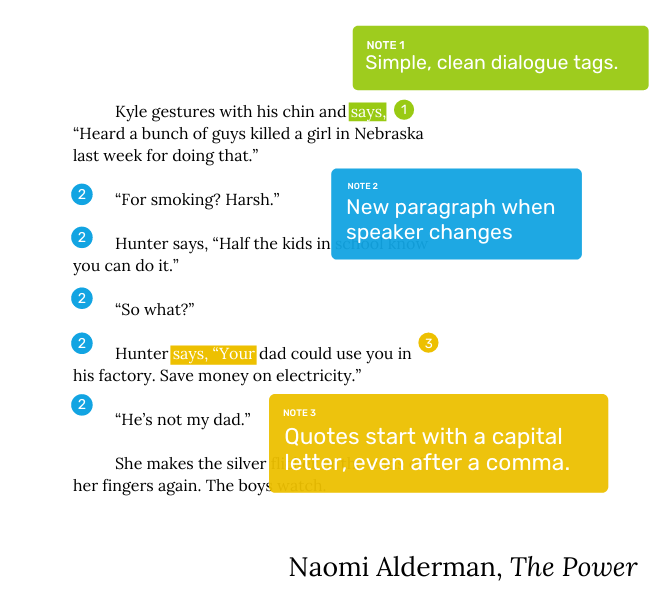

Now, before we get carried away, let’s cover some essential dialogue formatting rules.

Think of these as the grammar of a good conversation.

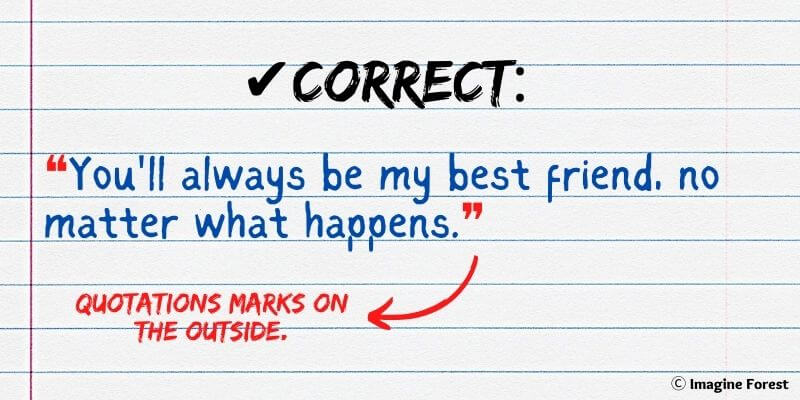

- Quotation Marks: Yep, those little squiggles are your best friend. They signal to the reader: “Hey! Someone’s talking!”

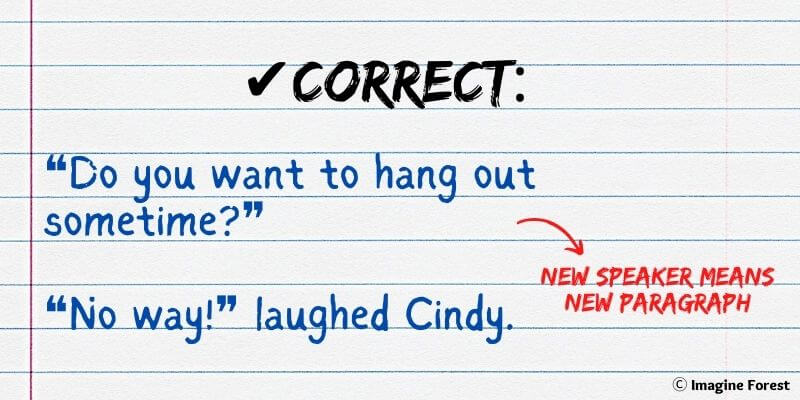

- New Speaker, New Paragraph: Whenever a different character starts talking, give them a new paragraph. It’s all about keeping things easy to follow.

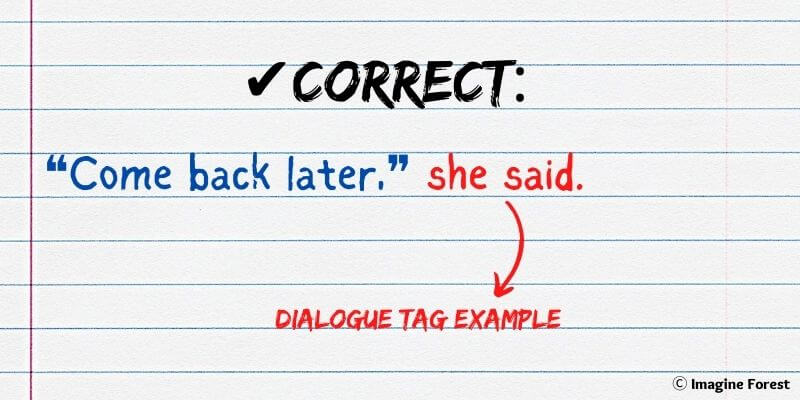

- Dialogue Tags: These are the little phrases like “he said” or “she replied.” Use them, but try not to overuse them. A well-placed action beat can often do a better job of showing who’s speaking.

Example 4: Dialogue that Creates Humor

Dialogue can be ridiculously funny when done well.

The key? Snappy exchanges, playful misunderstandings, and just a dash of absurdity. Consider this:

“I saw the weirdest thing at the grocery store today,” Tom said, “A woman arguing with a head of lettuce.” “Was she winning?” Lily asked, a grin playing on her lips.

You can almost hear the deadpan delivery, can’t you?

Example 5: Dialogue that Shows Relationships

The way characters speak to each other says a ton about the dynamics between them.

Is there warmth, hostility, an underlying power struggle? Dialogue can paint a crystal-clear picture. Imagine this exchange:

“You didn’t do the dishes again?” Sarah sighed, hands planted on her hips. “Aw, c’mon babe. I was busy,” Mike whined, avoiding her gaze.

We instantly sense the long-suffering tone from Sarah and the playful guilt from Mike.

Example 6: Dialogue with Subtext

The most interesting dialogue often has layers. What the characters say might not be exactly what they mean.

This is where subtext comes in – the unspoken thoughts and feelings bubbling beneath the surface.

Take this snippet:

“It’s a nice ring,” Emily said, her voice flat. “You don’t like it?” Mark’s brow furrowed. Emily shrugged. “It’s fine.”

Is Emily truly indifferent? Or is she masking disappointment, perhaps a sense of something not being quite right? Subtext makes us read between the lines.

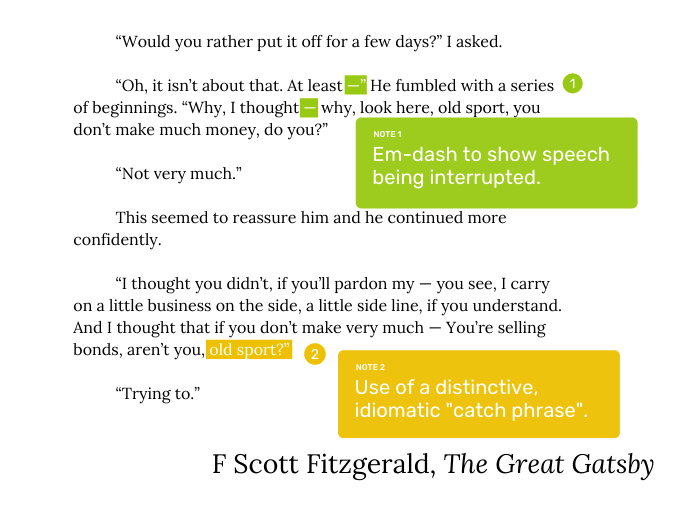

Formatting Tips: Getting Fancy

Now, let’s spice things up with a few more advanced formatting tricks:

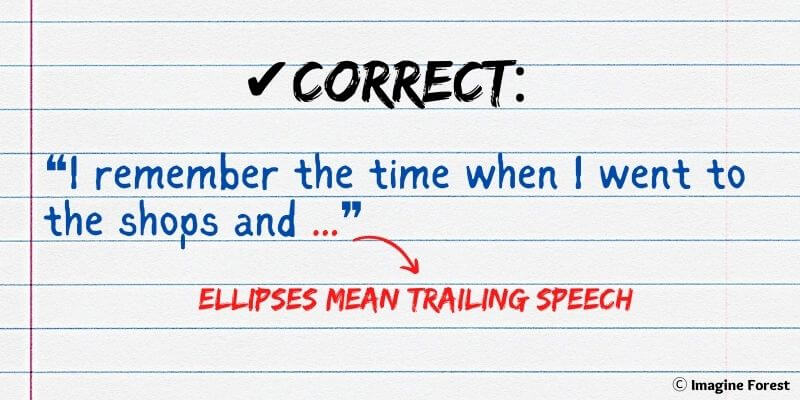

- Ellipses (…): These little dots are perfect for showing a character trailing off, hesitating, or searching for words. Example: “I…I don’t know what to say.”

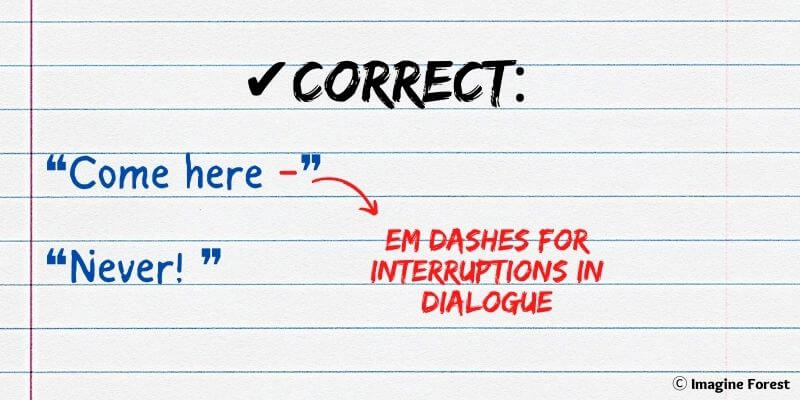

- Em Dashes (—): These guys can interrupt a thought or indicate a sudden change in direction. Example: “I was going to apologize, but then — well, you’re still being a jerk.”

- Internal Dialogue: Instead of quotation marks, sometimes you’ll want to italicize a character’s inner thoughts. Example: Why did I say that? I’m such an idiot.

Cautionary Note

It’s important to remember: dialogue shouldn’t feel like an interrogation. Avoid rigid “question-answer, question-answer” patterns. Real conversations flow and meander naturally.

Example 7: Dialogue with Dialects and Accents

Regional dialects and accents can bring so much flavor to your characters, but it’s a delicate balance.

You want to add authenticity without it becoming a caricature or making it hard to understand.

Here’s a subtle example:

“Well, I’ll be darned,” drawled the farmer, squinting at the sky. “Looks like a storm’s brewin’.”

Notice how just a few word choices and a slight change in pronunciation hint at the speaker’s background.

Example 8: Dialogue in Groups

Writing conversations with more than two people can get chaotic fast. The key is clarity.

Here are a few tips:

- Strong Dialogue Tags: Sometimes, you need to be more specific than just “he said” or “she said”. Example: “Don’t be ridiculous,” scoffed Sarah.

- Action Beats: Break up chunks of dialogue with actions that show who’s speaking. Example: Tom slammed his fist on the table. “I won’t stand for this!”

Example 9: Dialogue Over the Phone (or Other Technology)

Conversations where characters aren’t physically together pose unique challenges.

You can’t rely on body language cues. Instead, focus on conveying tone and potential misunderstandings.

For instance:

“Hello?” Sarah’s voice crackled through the phone. A long pause. “Sarah, is that you?” “Mom? Why are you whispering?”

Instantly there’s a sense of distance and something not being quite right.

Example 10: Inner Monologue with a Twist

We often think of internal dialogue as a single character reflecting, but sometimes our inner voices can argue.

This can be a powerful way to showcase internal conflict.

Here’s how it might look:

You should just tell him how you feel, one voice chimed. Are you crazy? the other shrieked back. He’ll never feel the same way .

This creates a vivid picture of a character torn between opposing desires.

Example 11: Dialogue With a Manipulative Character

Manipulative characters often use language as a weapon.

They might use guilt trips, flattery, or veiled threats to get what they want.

Consider this:

“After everything I’ve done for you…” The old woman sighed, a flicker of disappointment in her eyes. “Well, I guess I shouldn’t expect gratitude.”

Notice how she doesn’t directly ask for anything, instead hinting at a debt, leaving the listener feeling uneasy and obligated.

Example 12: Dialogue Across Time Periods

If you’re writing historical fiction or anything with time travel elements, you’ll need to capture the distinct speech patterns of different eras.

Imagine this exchange:

“Gadzooks! What manner of contraption is this?” The Victorian gentleman exclaimed, staring in bewilderment at the smartphone. “It’s a phone,” the teenager replied, barely suppressing a laugh. “Let me show you.”

This little snippet highlights the potential for both humor and linguistic challenges when worlds collide.

Formatting Tip: Dialogue Without Tags

Sometimes, for a rapid-fire or dreamlike effect, you might want to ditch the “he said” or “she asked” altogether.

It’s a bold move, but it can be effective if done sparingly.

Check this out:

“Where are you going?” “Away.” “When will you be back?” “I don’t know.” “Please don’t leave me.”

This creates a sense of urgency, the raw exchange forcing us to focus solely on the words themselves.

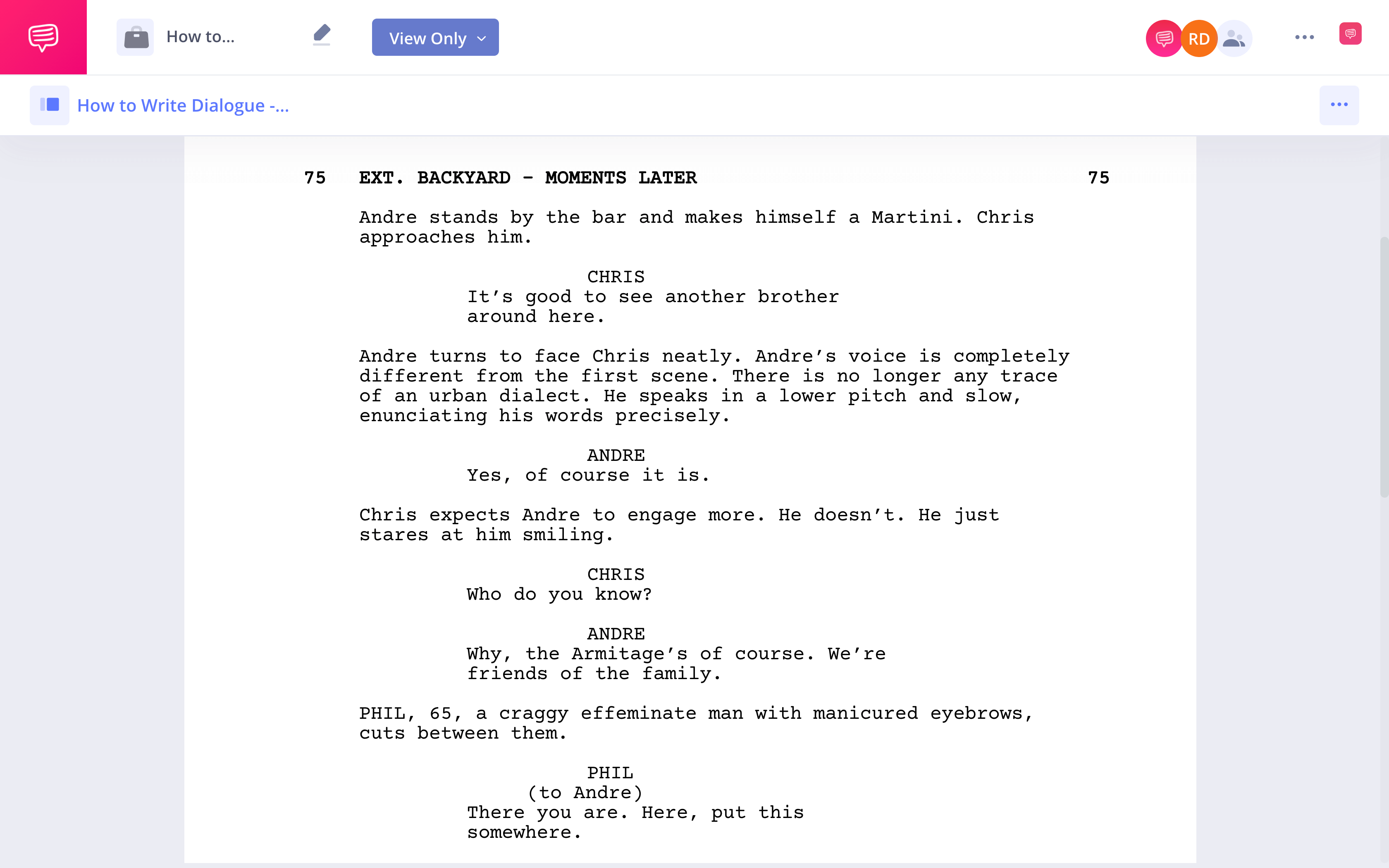

Example 13: Dialogue that Shows Transformation

A great way to showcase how a character develops is through shifts in how they speak.

Maybe they become bolder, quieter, or their vocabulary changes.

Let’s see an example:

Scene 1: “I-I don’t know,” Emily whimpered, cowering in the corner. Scene 2 (Later in the story): “That’s it. I’m not taking this anymore!” Emily declared, her chin held high.

The dialogue itself reflects her transformation from victim to someone ready to stand up for herself.

Example 14: Dialogue that’s Just Plain Weird

It’s okay to get strange sometimes.

Absurdist humor or unsettling conversations can add a unique flavor to your story. Just be sure it fits the overall tone.

“Do you believe in cucumbers?” the man asked, his eyes wide and unblinking. “Excuse me?” “Cucumbers, my dear. Agents of the underground vegetable kingdom.”

This immediately creates a sense of oddness and perhaps a touch of unease. Is this guy crazy, or is there something more going on?

Example 15: Dialogue with a Purpose

Remember, good dialogue isn’t just about being entertaining.

It should move your story along. Here are some functions dialogue can serve:

- Providing Exposition: Sometimes, you need to inform the reader of backstory or world-building details. Trickle information through natural conversation rather than an information dump.

- Foreshadowing: Subtle hints within a conversation can foreshadow future events or create a sense of unease for the reader.

- Revealing a Twist: A single line of dialogue can completely flip the script and reframe everything that came before.

Example 16: Dialogue with Non-Verbal Elements

So much of communication happens beyond just words.

Sighs, laughs, and gestures can add richness to dialogue on the page.

“I’m fine,” she said, crossing her arms and looking away.

Notice how the body language contradicts her words, hinting at inner turmoil.

Example 17: Silence as Dialogue

Sometimes, what isn’t said is the most powerful thing of all.

A pregnant pause or a character refusing to speak can convey volumes.

Imagine this:

“So, will you help me or not?” Tom pleaded. Sarah stared at him, her lips a thin line. Finally, she turned and walked away.

The lack of a verbal response speaks louder than any words could.

Example 18: Dialogue With Humorous Effect

A well-timed O.S. voice can deliver a funny remark or punchline, undercutting the seriousness of a scene or taking a moment in an unexpected comedic direction.

INT. CLASSROOM – DAY The teacher drones on about the causes of the American Revolution, his voice as dull as the worn textbook in front of him. KEVIN tries to stifle his yawns, failing miserably. STUDENT (O.S.) Is he ever going to stop talking? My brain just turned to mush. Snickers ripple through the class. The teacher pauses, a look of annoyance flickering across his face. Kevin shoots a desperate look towards the source of the O.S. voice.

- Timing is everything. The best comedic O.S. lines act as a witty reaction to something else happening in a scene. The student’s comment comes right as Kevin’s boredom peaks.

- Subverting expectations is funny. The audience expects the scene to continue with a stern reprimand for speaking out of turn, but the script doesn’t give us that. This leaves room for further humor.

- Consider the tone of the voice – sarcastic, matter-of-fact, or outright whiny? This adds to the comedic effect.

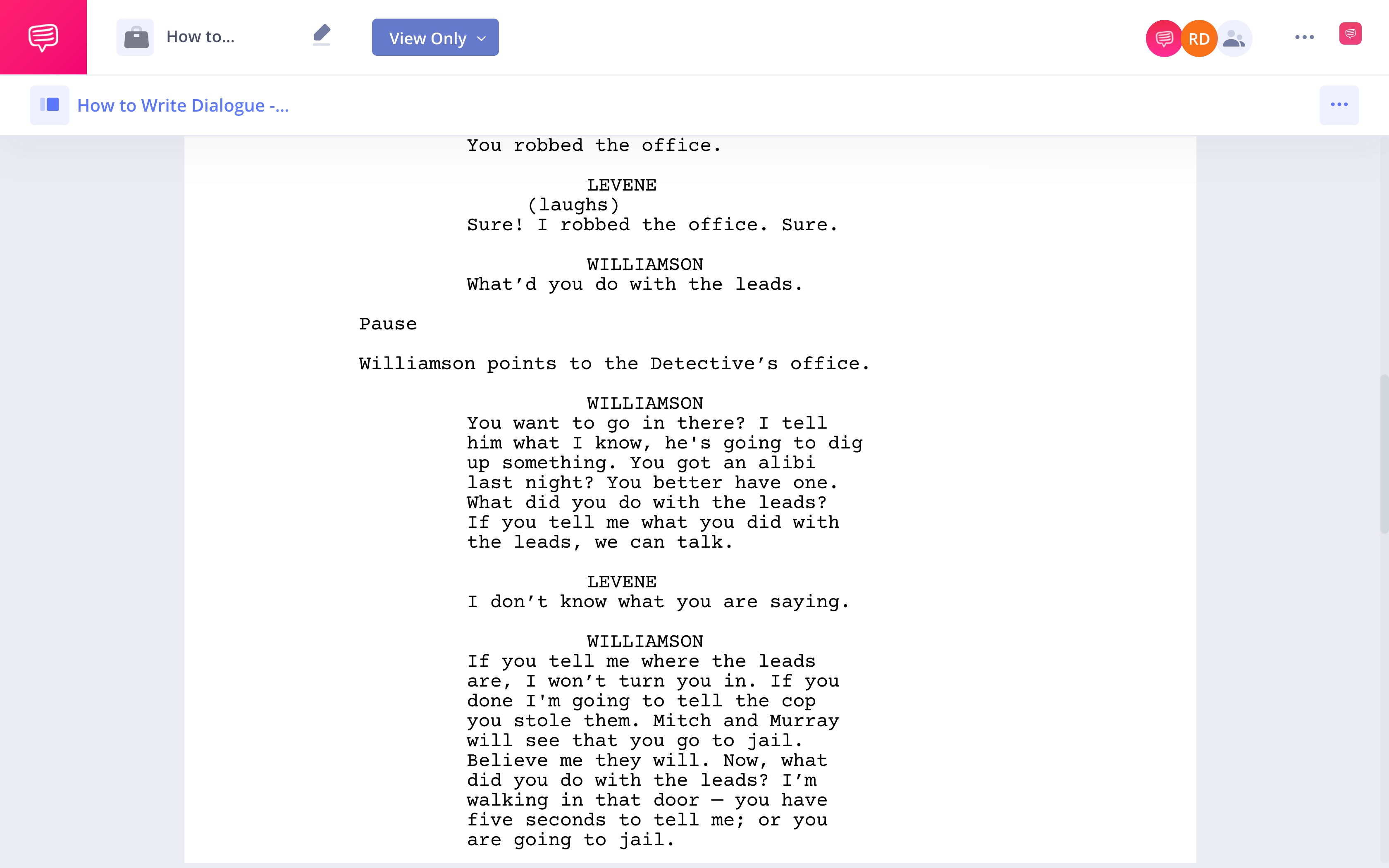

Example 19: Dialogue With Unexpected Reveals

Think of this as a surprise twist using O.S. dialogue.

The audience (and maybe even some characters) are led to believe one thing, only for an O.S. voice to reveal something completely unexpected, shifting the scene’s dynamic.

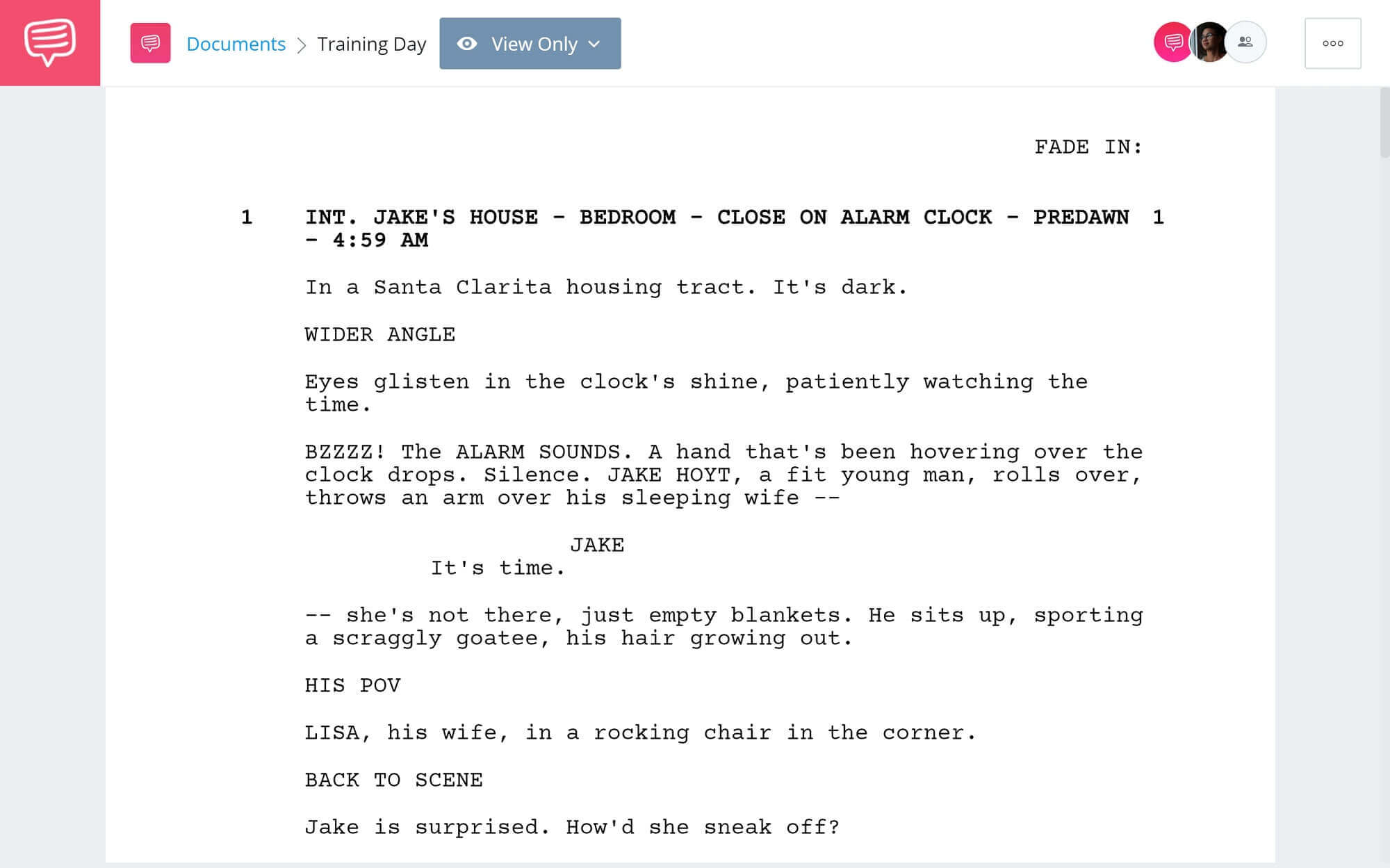

INT. POLICE INTERROGATION ROOM – NIGHTDETECTIVE HARRIS paces in front of a nervous SUSPECT. Photos of the crime scene are scattered on the table. HARRIS Don’t lie to me! We’ve got witnesses who saw you at the scene. SUSPECT I – I swear, I had nothing to do with it! I was… I was with my girlfriend. Harris leans in, a triumphant glint in her eyes. She claps her hands sharply, startling the suspect. WOMAN (O.S.) That’s a lie! He was nowhere near me last night! The suspect whips around. His face pales as we hear the sound of the interrogation room door swinging open…

- The power lies in the build-up. The initial dialogue and the characters’ reactions should lead the audience to believe one outcome, making the O.S. interruption all the more impactful.

- Consider who speaks the O.S. line. Is it someone the audience recognizes, or a totally new character whose identity becomes a new mystery?

- Play with the proximity of the voice. Is it right outside the room, adding to the dramatic reveal as the door opens, or is it more distant – perhaps a voice over an intercom – for an even more unsettling effect?

Example 20: Dialogue With a “Haunted” Feeling

Explanation: O.S. can be used to create an eerie or unsettling atmosphere, particularly in horror or psychological thrillers. This could be unexplained voices, creepy whispers, or sounds that hint at a supernatural (or simply unnerving) presence.

INT. OLD MANSION – NIGHTSARAH explores the abandoned mansion, flashlight cutting through the thick dust. Cobwebs cling to every surface. A faint WHISPER drifts through the air, seeming to come from everywhere at once. Sarah freezes. VOICE (O.S.) Get out… leave this place… Sarah’s breath catches in her throat. She hesitantly follows the direction of the voice, her flashlight beam trembling.

- Less is more. The vaguer and more inexplicable the O.S. voice, the more chilling it becomes.

- Layer sounds for a full creepy effect. Combine whispers with unexpected bangs, creaks, or the faint sound of footsteps following behind Sarah.

- Play with audience expectations. If the script initially leads the audience to think the house is merely abandoned, the O.S. voices become that much more terrifying.

Here is a good video about writing dialogue:

Additional Dialogue Tips & Tricks

- Read Your Dialogue Aloud: This is the best way to catch awkward phrasing or unnatural rhythms. Our ears often pick up on what our eyes might miss.

- Less is More: Don’t feel the need to have every single interaction be profound. Sometimes a simple “Hey” or “Thanks” can do the job just fine.

- Eavesdrop: Paying attention to real-life conversations is fantastic research. Note the pauses, the filler words, the way people interrupt each other.

Final Thoughts: Writing Dialogue

Phew! We did it!

Does that feel like a solid collection of dialogue examples? We haven’t covered absolutely every scenario, but I hope these illustrate the vast potential within dialogue to bring your stories to life.

Read This Next:

- How To Use Action Tags in Dialogue: Ultimate Guide

- How Do Writers Fill a Natural Pause in Dialogue? [7 Crazy Effective Ways]

- Can You Start a Novel with Dialogue?

- How To Write A Southern Accent (17 Tips + Examples)

- How to Write a French Accent (13 Best Tips with Examples)

Writing dialogue in a story requires us to step into the minds of our characters. When our characters speak, they should speak as fully developed human beings, complete with their own linguistic quirks and unique pronunciations.

Indeed, dialogue writing is essential to the art of storytelling . In real life, we learn about other people through their ideas and the words they use to express them. It is much the same for dialogue in fiction. Knowing how to write dialogue in a story will transform your character development , your prose style , and your story as a whole.

We’ve packed this article with dialogue writing tips and good examples of dialogue in a story. These tools will help your characters speak with their full uniqueness and complexity, while also helping you fully inhabit the people that populate your stories.

Let’s get into how to write dialogue effectively. First, what is dialogue in a story?

Inner Dialogue Definition

Indirect dialogue definition.

- How to Write Dialogue: Elements of Good Dialogue Writing

How to Write Dialogue in a Story: 4 DOs of Dialogue Writing

- How to Write Dialogue in a Story: 4 DON’Ts of Dialogue Writing

9 Devices for Writing Dialogue in a Story

Dialogue writing exercises, how to format dialogue, what is dialogue in a story.

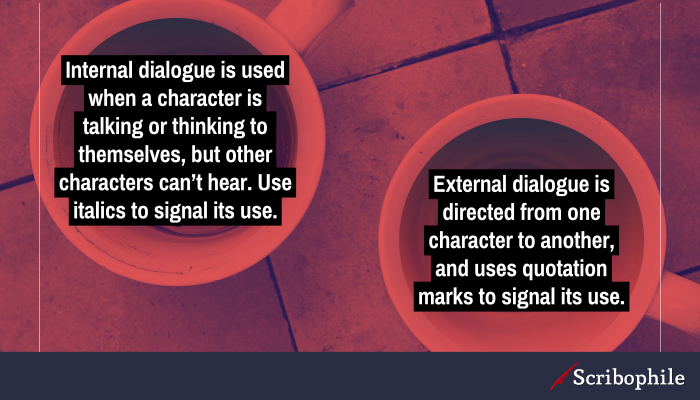

Dialogue refers to any direct communication from one or more characters in the text. This communication is almost always verbal, except for instances of inner dialogue, where the character is speaking to themselves.

Dialogue definition: Direct communication from one or more characters in the text.

In works of Fantasy or Science Fiction, characters might communicate with each other telepathically or through non-human means. This would also count as dialogue in a story.

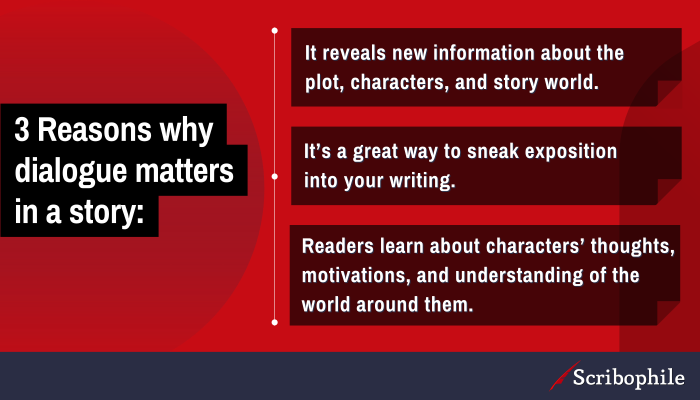

The importance of dialogue in a story cannot be overstated. The words that characters speak act as windows into their psyches: we can learn lots about people by what they say, as well as what they omit.

Additionally, dialogue allows for the exchange of information, which will advance the story’s plot. Any story that involves conflict between two or more people must involve dialogue, or else the story will never reach its climax and resolution.

Inner dialogue is a form of communication in which a character speaks with themselves. This is, essentially, a form of monologue or soliloquy . Inner dialogue allows the reader to view the character’s thoughts as they happen, transcribing their doubts, ideas, and emotions onto the page.

Inner dialogue definition: a form of communication in which a character speaks with themselves.

Inner dialogue can also be a memory or reminiscence, even if the character is not consciously speaking to themselves. If the narrator shows us a memory that the character is currently thinking about, then that character is still offering something to the narrative by means of unspoken conversation.

It is not necessary for any story to have inner dialogue. However, if you plan to use dynamic characters in your writing, then it probably makes sense to show the reader what that character’s inner world looks like. Developing complex, three dimensional characters is essential to telling a good story, which requires us to have some sort of window into those characters’ minds.

Indirect dialogue is dialogue, summarized. It is not put in quotes or italics; rather, it neatly sums up what a character said, without going into detail.

Indirect dialogue definition: dialogued, summarized.

In other words, we don’t get to see how the character said something , we are only told what they said. This is useful for when the information is better summarized than told in excruciating details, because the narrator wants to get to the important dialogue, the dialogue that introduces new information or reveals important aspects of the character’s personality.

Haruki Murakami gives us a great example in Kafka on the Shore :

I tell her that I’m actually fifteen, in junior high, that I stole my father’s money and ran away from my home in Nakano Ward in Tokyo. That I’m staying in a hotel in Takamatsu and spending my days reading at a library. That all of a sudden I found myself collapsed outside a shrine, covered in blood. Everything. Well, almost everything. Not the important stuff I can’t talk about.

How to Write Dialogue: The Elements of Good Dialogue Writing

Every story needs dialogue. Unless you’re writing highly experimental fiction , your story will have main characters, and those characters will interact with the world and its other people.

That said, there’s no “correct” way to write dialogue. It all depends on who your characters are, the decisions they make, and how they interact with one another.

Nonetheless, good dialogue writing should do the following:

Develop Your Characters

A close study in how to write dialogue requires a close study in characterization. Your characters reveal who they are through dialogue: by paying close attention to your characters’ word choice , you can clue your reader into their personality traits and hidden psyches.

Your characters will often reveal key aspects of their personality through dialogue.

One character who can’t stop characterizing himself is Holden Caulfield from The Catcher in the Rye . J. D. Salinger’s anti-hero could be psychoanalyzed for hours. Take, for example, this excerpt from Holden’s inner dialogue:

“Grand. There’s a word I really hate. It’s a phony. I could puke every time I hear it.”

What do we learn about Holden through this line? For starters, we learn that Holden is the type of person who analyzes and scrutinizes each word – just like writers do, perhaps. We also learn that Holden hates anything positive. Always a downer, Holden despises words of praise or grandeur, thinking the whole world is irresolvably flat, boring, and monotonous. He hates grandness almost as much as he hates phoniness, and both concepts are sure to make him sick.

Holden is a character who puts his entire personality on the page, and as readers, we can’t help but understand him – no matter how much we like him or hate him.

Set the Scene

Dialogue is a great way to explore the setting of your story. When the setting is explored through dialogue writing, both the characters and the reader experience the world of the story at the same time, making the writing feel more intimate and immediate.

When the setting is explored through dialogue writing, the writing feels more intimate and immediate.

You might have your character wander through the streets of New York, as Theo does in The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt. Here’s an excerpt of inner dialogue:

“It was rainy, trees leafing out, spring deepening into summer; and the forlorn cry of horns on the street, the dank smell of the wet pavement had an electricity about it, a sense of crowds and static, lonely secretaries and fat guys with bags of carry-out, everywhere the ungainly sadness of creatures pushing and struggling to live.”

Notice Theo’s attention to detail, and the vibrant imagery he uses to capture the city’s energy. Of course, you might set the scene more simply, as Dorothy does when she says:

“Toto, I’ve a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore.”

In only a few words, this line of dialogue advances not only the setting but also Dorothy’s characterization. She is innocent and operating from a limited frame of reference, and the setting could not be more different from her homely Kansas background.

Both methods of scene setting help advance the world that the reader is exploring. However, don’t explore the setting exclusively through dialogue. Characters are not objective observers of their world, so some information is better explained through narration since the narrator is (often) a more reliable voice.

Advance the Plot

Dialogue doesn’t just tell us about the story and the people inside it; good dialogue writing also advances the plot . We often need dialogue to reveal important details to the protagonist , and sometimes, an emotionally tense conversation will lead to the next event in the story.

At times, dialogue will advance the plot by offering a twist or revealing sudden information. We can all agree that the following lines of dialogue advanced the plot of Star Wars :

“Obi-Wan never told you what happened to your father.”

“He told me enough! He told me you killed him!”

“No. I am your father.”

And the following bit of dialogue catalyzed the plot of the entire Harry Potter series:

“You’re a wizard, Harry.”

The exchange of information is often what accelerates (0r resolves) a story’s conflict. Paying attention to word choice and the strategic revelation of information is key to using dialogue in a story.

Just like in real life, your characters don’t always say what they mean. Characters can lie, hint, suggest, confuse, conceal, and deceive. But one of the most powerful uses of dialogue writing is to foreshadow future events.

In Shakespeare’s Romeo & Juliet , Romeo foreshadows the death of both lovers when he exclaims to Juliet:

“Life were better ended by their hate, / Than death prorogued, wanting of thy love.”

In saying he would rather die lovers than live in longing, Romeo unknowingly predicts what will soon happen in the play.

Foreshadowing is an important literary device that many fiction stories should utilize. Foreshadowing helps build suspense in the story, and it also underlines the important events that make your story worth reading. Don’t try to trick your readers, but definitely use foreshadowing to keep them reading.

Learn more about foreshadowing here:

Foreshadowing Definition: How to Use Foreshadowing in Your Fiction

We’ve talked about what dialogue writing should accomplish, but that doesn’t answer the question of how to write dialogue in a story. Let’s answer that question now—with some more dialogue writing examples in the mix.

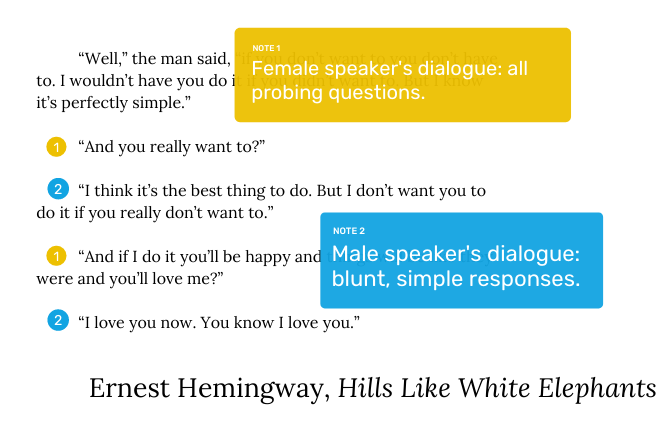

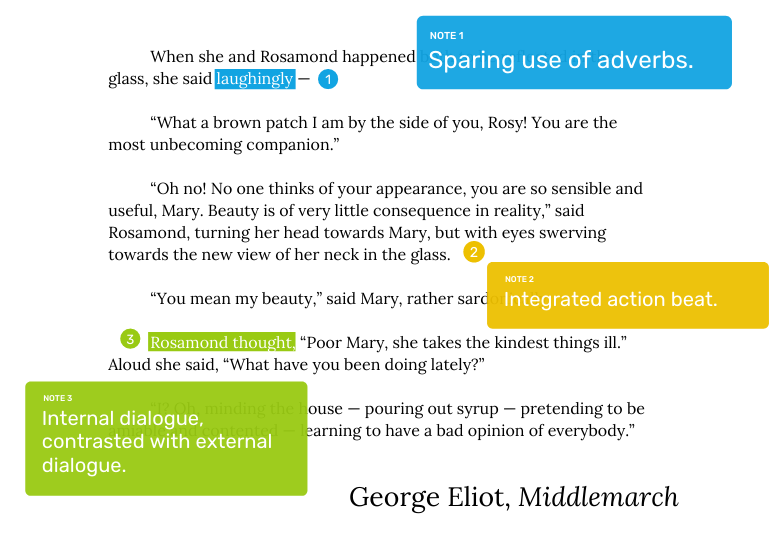

1. How to Write Dialogue in a Story: Differentiate Each Character

Each character will have their own style of speaking, and will emphasize different things when they talk.

Your characters’ dialogue should be like thumbprints, because no two people are alike. Each character will have their own style of speaking, and will emphasize different things when they talk. You can make each character unique by altering the following elements of dialogue style:

- Sentence length: Some people are verbose and loquacious, others terse and stoic.

- Dialogue Punctuation: Do your characters let their sentences linger… or do they ask a lot of questions? Are they really excited all the time?! Or do they interrupt themselves frequently—always remembering something they forgot to mention—struggling to put their complex thoughts into words?

- Adjectives/adverbs: Characters that are expressive and verbose tend to use a lot of adjectives and adverbs, whereas characters that are quiet or less expressive might stick to their nouns and verbs.

- Spellings and pronunciation: Do your characters omit certain vowels? Do they lisp? The way you write a line of dialogue might reveal a character’s dialect, and adding consistent quirks to a character’s speech will certainly make them more memorable.

- Repetitions and emphasis: Do your characters have any catchphrases? Do they use any words or phrases as crutches? Maybe they emphasize words periodically, or have a strange cadence as they speak. We tend to repeat certain words and phrases in our own everyday vocabularies; repetition is also a useful device for writing dialogue in a story.

You’ve already seen character differentiation from the previous quotes in this article. In this scene from The Catcher in the Rye , notice how differently Holden Caulfield speaks from the young woman he’s talking to—and just how much characterization is implied in their divergent voices:

“You don’t come from New York, do you?” I said finally. That’s all I could think of.

“Hollywood,” she said. Then she got up and went over to where she’d put her dress down, on the bed. “Ya got a hanger? I don’t want to get my dress all wrinkly. It’s brand-clean.”

“Sure,” I said right away. I was only too glad to get up and do something.

Aside from these two characters being different from one another, Holden speak differently than characters in other works of fiction. Can you imagine Holden Caulfield being Romeo in R&J ? He’d say something stupid, like “Juliet’s family are all phonies, but the funny thing is you can’t help but fall half in love with her.”

A more contemporary example comes from White Teeth by Zadie Smith. Every character in this novel is exceptionally well differentiated, even the minor characters—like Brother Ibrahim ad-Din Shukrallah, who appears only briefly towards the novel’s end. Here’s an excerpt:

“Look around you. And what do you see? What is the result of this so-called democracy, this so-called freedom, this so-called liberty ? Oppression, persecution, slaughter . Brothers, you can see it on national television every day, every evening, every night ! Chaos, disorder, confusion . They are not ashamed or embarrassed or self-conscious ! They don’t try to hide, to conceal, to disguise . They know as we know: the entire world is in a turmoil!”

Pay attention to the dialogue. What do you notice? What’s odd about the way he speaks? If you don’t notice it, the novel’s narrator gives us a hint:

“No one in the hall was going to admit it, but Brother Ibrahim ad-Din Shukrallah was no great speaker, when you got down to it. Even if you overlooked his habit of using three words where one would do, of emphasizing the last word of such triplets with his see-saw Caribbean inflections, even if you ignored these as everybody tried to, he was still physically disappointing.”

For more advice on characterization, check out our article on character development.

https://writers.com/character-development-definition

2. How to Write Dialogue in a Story: Consider the Context

A common mistake writers often make when writing dialogue in a story: they use the same speaking style for that character throughout the entire story.

For example, if you have a character that tends to speak in wordy, roundabout sentences, you might think that every sentence of dialogue should be wordy and roundabout.

However, your character’s dialogue needs to take context into consideration. A wordy character probably won’t be so wordy if they’re being held at gunpoint, and their words might stammer or falter when talking to a crush. Or, in the case of Jane Eyre , the context might make your statement more powerful. Jane proclaims:

“Do you think, because I am poor, obscure, plain and little, I am soulless and heartless? You think wrong! I have as much soul as you—and full as much heart!”

As she lives in a society with strict gender roles, Jane’s statement—to a man, no less—is thrillingly bold and controversial for its time.

Your characters aren’t monotonous, they’re dynamic and fluid, so let them speak according to their surroundings.

3. How to Write Dialogue in a Story: Space Out Moments of Dialogue

If your characters just had a lengthy conversation, give them a page or two before they start speaking again. Dialogue is an important part of storytelling, but equally important is narration and description.

The following excerpt from Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy has a great balance of dialogue (underlined) and narration.

“Are there any papers from the office?” asked Stepan Arkadyevitch, taking the telegram and seating himself at the looking-glass.

“On the table,” replied Matvey, glancing with inquiring sympathy at his master; and, after a short pause, he added with a sly smile, “ They’ve sent from the carriage-jobbers.”

Stepan Arkadyevitch made no reply, he merely glanced at Matvey in the looking-glass. In the glance, in which their eyes met in the looking-glass, it was clear that they understood one another. Stepan Arkadyevitch’s eyes asked: “Why do you tell me that? don’t you know?”

Matvey put his hands in his jacket pockets, thrust out one leg, and gazed silently, good-humoredly, with a faint smile, at his master.

“I told them to come on Sunday, and till then not to trouble you or themselves for nothing,” he said. He had obviously prepared the sentence beforehand.

You can see, in the above text, that about 1/3 of the writing is dialogue. This allows the reader to see the full scene while still viewing the conversation, making this an excellent balance of narration and dialogue writing.

Simply put: balance dialogue with your narrator’s voice, or else the reader might lose their attention, or else miss out on key information.

4. How to Write Dialogue in a Story: Use Consistent Formatting

There are several different ways to format your dialogue, which we explain later in this article. For now, make sure you’re consistent with how you format your dialogue. If you choose to indent your characters’ speech, make sure every new exchange is indented. Inconsistent formatting will throw the reader out of the story, and it could also prevent your story from being published.

How to Write Dialogue in a Story: 4 DON’Ts of Dialogue Writing

Just as important as the DOs, the DON’Ts of dialogue writing are just as important to crafting an effective story. Let’s further our discussion of how to write dialogue in a story: we’ll dive into what you shouldn’t do when writing dialogue, alongside some more dialogue examples.

1. DON’T Include Every Verbal Interjection

When people talk, they don’t always talk linearly. People interrupt themselves, they change direction, they forget what they were talking about, they use pauses and “ums” and “ohs” and “ehs.” You can include a few of these verbal interjections from time to time, but don’t make your dialogue too true-to-life. Otherwise, the dialogue becomes hard to read, and the reader loses interest.

Let’s take a famous line from The Catcher in the Rye and fill it in with verbal interjections.

“I have a feeling that you are riding for some kind of a terrible, terrible fall. But I don’t honestly know what kind.”

With interjections:

Oh, man—I have a feeling, like, that you are riding for some kind of… a terrible, terrible fall. But, uh, I don’t honestly know what kind?

What do you think of the edited quote? The interjections make it much harder to read, much less personable, and honestly, they become kind of annoying. However, the quote with interjections is much more “true to life” than the original quote. Your characters don’t need to speak perfectly, but the dialogue needs to be enjoyable to read.

2. DON’T Overwrite Dialogue Tags

Dialogue tags are how your character expresses what they say. In the quote “‘You’re all phonies,’ Holden said,” the dialogue tag is “Holden said.”

Unique dialogue tags are fine to use on occasion. Your characters might yell, stammer, whisper, or even explode with words! However, don’t use these tags too frequently—the tag “said” is often perfectly fine. Notice how overused dialogue tags ruin the following conversation:

“How are you?” I stammered.

“Great! How are you?” she inquired.

“I’m hungry,” I announced.

“We should get lunch,” she blurted.

“I’m on a diet,” I cried.

“You poor thing,” she rejoined.

Sure, the conversation isn’t interesting to begin with, but the dialogue tags make this writing cringe-worthy. All of this dialogue can be described with “said” or “replied,” and many of these quotes don’t even need dialogue tags, because it’s clear who’s speaking each time.

This is doubly serious when dialogue tags are combined with adverbs : adjectives that modify the verbs themselves. Our intent with these adverbs is to intensify our writing, but what results is a strong case of diminishing returns. Let’s see an example:

“I don’t love you anymore,” she said.

“I don’t love you anymore,” she spat contemptuously.

Yikes! If your dialogue tags start distracting the reader, then your dialogue isn’t doing enough work on its own. The reader’s focus should be on the character’s statement, not on the way they delivered that statement. If she spoke those words with contempt, show the reader this in the dialogue itself, or even in the character’s body language.

Lastly: if you’re going to use a dialogue tag other than “said,” make sure the verb you use actually corresponds to dialogue. In other words, there needs to be a speaking verb before you describe some other sort of action.

Here’s an example of what NOT to do:

“I don’t love you anymore,” she stomped.

She might have stomped while saying that line, but “to stomp” is not a kind of communication.

The dialogue tag “said” is perfectly fine for most situations.

3. DON’T Stereotype

Everybody’s speech has a myriad of influences. Your characters’ way of speaking will be influenced by their parents, upbringing, schooling, socioeconomic status, race, gender, sexual orientation, and their own unique personality traits.

Of course, these personal backgrounds will influence your character’s dialogue. However, you shouldn’t let those traits overpower the character’s dialogue—otherwise, you’ll end up stereotyping.

Stereotyped characters are both glaringly obvious and embarrassing for the author. For example, J. K. Rowling didn’t do herself any favors by naming a character Cho Chang—both of which are Korean last names. Similarly, if all of your male characters are strong, charismatic, and loud, while all of your female characters are meek, helpless, and insecure, your writing will be both offensive and inaccurate to life.

Let’s explore this with two ways of writing a policeman.

“Don’t stand here,” said the policeman in front of the caution tape. “We need to keep this street clear.”

And here is lazy writing that takes no real interest in the character beyond one-dimensional surface traits:

“Move it along, folks, move it along,” said the policeman in front of the caution tape. “Nothing to see here.”

Neither policeman is going to win a dialogue award, but the second policeman doesn’t even seem like a real person . He’s written in unconsidered cliché: phrases we’ve all heard a thousand times, general ideas of what policemen tend to say.

Simply put, stereotyped dialogue is bad writing. Not only does it make your characters one-dimensional, it’s also offensive to whomever your characters resemble. If you’re going to be writing your characters from a careless, surface-level take, you might reconsider whether you want to write them at all.

What to do about this? The safest way to avoid stereotyping is to write using identities that you know both personally and intimately. If your writing takes you beyond those identities, then do your research: seek out, and truly work to internalize, a diverse array of input from people whose identities resemble those you’d like to write about.

4. DON’T Get Discouraged

For some writers, dialogue is the hardest part about writing fiction. It’s much easier to describe a character than to get in the character’s head, transcribing their thoughts into language.

If you feel like your characters aren’t saying the right things, or if the dialogue feels tricky to master, don’t get discouraged. Dialogue writing is difficult!

The following devices and exercises will help you master the art of writing dialogue in a story.

An important consideration for your characters is giving them distinct speech patterns. In real life, everyone talks differently; in fiction it’s much the same. The following devices will help you write dialogue in a story, as they offer ways to make your characters unique, compelling, and conversational.

Note: don’t try to use all nine of these devices for one character. Your dialogue should flow and feel consistent with the way people speak in real life, but if you overload your character’s speech with idioms, colloquialisms, proverbs, slang, and jargon, they won’t speak like anyone in the real world.

Use these devices as quirks for your characters. You can even use colloquialisms and vernacular to establish the setting, or use jargon to assign your character their occupation and social standing. Be wise, be strategic, and keep an ear for how people sound in real life.

Now, here’s how to write dialogue using 9 specific devices.

1. Colloquialism

A colloquialism is a word or phrase that’s specific to a language, geographical region, and/or historical period. Mostly used in informal speech, colloquialisms will rarely show up in the boardroom or the courtroom, but they pop up all the time in casual conversation.

We often use colloquialisms without realizing it. Take, for example, the shopping cart. Someone in the U.S. Northeast might call it a “cart,” while someone in the South might call it a “buggy.”

In fact, colloquialisms abound in the history of the English language. When it rains but the sun is out, a native Floridian might call it a sunshower. A Wisconsinite will call a water fountain a “bubbler.” In the 1950s, a small child might have been called an “ankle-biter.” Nowadays, a New Yorker might describe cold weather as being “brick outside.” (Yes, brick.)

Colloquialisms help define a character’s geographic background and historical time period. They also help signify when the character feels comfortable and informal, versus when they are speaking in an uncomfortable or professional situation.

2. Vernacular

Vernacular refers to language that is simple and commonplace. When a character’s speech is unadorned and everyday, they are speaking in vernacular, using words that can be understood by every person in that character’s time period. (A colloquialism is often an example of vernacular.) For dialogue in a story, your characters will likely use vernacular, unless they try to avoid it at all costs.

The opposite of vernacular would be dialect, which is speech that is tailored to a specific setting, and is therefore not commonplace or universally understood. An example of vernacular is contrasted with dialect below.

A dialect is a type of speech reserved for a particular time period, geographical location, social class, group of people, or other specific setting. It is language that the entire population might not comprehend, as it uses words, phrases, and grammatical decisions that aren’t universally understood.

Here’s an example of modern day vernacular. The same sentence has been rewritten as though it were spoken by someone with a Southern dialect.

Vernacular: I am craving some coleslaw and a soft drink.

Southern Dialect: I’m fixin’ for some slaw and soda pop.

An English speaker who doesn’t hail from the American South may be tripped up by “fixing” and “slaw,” as those terms aren’t universally understood.

Do note: the words “coleslaw” and “soft drink” can also be considered dialects of other regions in the United States. However, these words will likely be understood across the nation.

A slang is a word or phrase that is not part of conventional language usage, but which is still used in everyday speech. Generally, younger generations coin slang words, as well as queer communities and communities of color. (Some of the terms below started in AAVE , or African American Vernacular English.) Those words then become dictionary entries when the word has circulated long enough in popular usage. Slang is a form of colloquialism, as well as a form of dialect, because slang terms are not universally understood and are often associated with a specific age group in a specific region.

Some recent examples of slang words and phrases include:

- No cap—“no lie.”

- Boots—this is a sort of grammatical intensifier, placed after the thing being intensified. “I’m hungry, boots” is basically the same as “I’m so hungry.”

- Bop—a catchy or irresistible song.

- Drip—a particularly fashionable or interesting style of clothes.

- It’s sending me—“that’s hilarious.”

- Periodt—a more “final” use of the word “period” when a salient point has been made.

- Snatched—used when someone’s fashion is impeccable. In the case of someone’s waist size, snatched refers to an hourglass figure.

- Pressed—“stressed” or “annoyed.”

- Slaps—“exceptionally good.”

- Stan—stan is a portmanteau of “stalker fan,” but really what it means is that you enjoy something intensely or obsessively. You “stan” a song or a movie, for example.

- Werk—a term to describe something done exceedingly well. If you’re dancing tremendously, I might just yell “werk!”

- Wig—when something shocks, excites, or moves you, just say “wig.”

Jargon is a word or phrase that is specific to a profession or industry. Usually, a jargon word intentionally obfuscates the meaning of what it represents, as the word is meant to be understood solely by people within a certain profession.

Often, people let jargon slip from their tongues without realizing the word is inaccessible. For example, a doctor might tell their friend they have rhinitis, rather than a seasonal allergy. Or, someone well-versed in mid-century diner lingo might ask for “Adam and Eve on a raft” rather than “two poached eggs on toast.”

When it comes to dialogue in a story, the occasional use of jargon can help characterize someone through their profession. However, too much jargon usage will start to sound comical and inane, as most people don’t speak in jargon all the time.

An idiom is a phrase that is specifically understood by speakers of a certain language, and which has a figurative meaning that differs from its literal one. Idioms are incredibly hard to translate, because the meaning conveyed by the idiom does not appear within the words themselves.

For example, a common idiom in the United States is to say someone is “under the weather” when they’re feeling ill. No part of the phrase “under the weather” conveys a sense of sickness; at most, it might communicate that that person feels pushed down by the weather. But then, what weather? Could they be under “good” weather, too? These are questions that someone who doesn’t speak English natively will likely ask.

So, the literal meaning of “under the weather” is different from the figurative meaning, which is “ill.” Some other idioms in the English language include:

- Pulling your leg—just having fun with someone or messing with them.

- Bat a thousand—to be successful 100% of the time.

- The last straw—the final incident before something (usually negative) occurs.

- Big fish in a little sea—someone is famous or hugely successful, but in a very small corner of the world.

- Eat your heart out—be envious of something.

An idiom can also reveal regionality, as some idioms are only spoken in certain dialects. For example, when it rains while the sun is shining, a common idiom in the South is that “the devil is beating his wife.” This phrase is understood in other parts of the U.S. and might have its roots in folklore, but it is primarily spoken by people in the American South.

7. Euphemism

A euphemism is the substitution of one word for another, more innocuous word. We often use euphemisms in place of words and phrases that are sexual, uncomfortable, or otherwise taboo.

For example, when someone dies, you might hear their family member say “they kicked the bucket.” Or, if someone were unemployed but didn’t want to say it, they might say they are “between jobs” or “searching for better opportunities.”

Euphemisms present something psychologically interesting to a person’s dialogue. We often use language to mask that which upsets us most but which we are unwilling to confront or communicate. A euphemism for death is intended to mask the pain of death; a euphemism about unemployment is intended to mask the shame of unemployment.

We might also use euphemisms to hide information from people we don’t trust. Let’s say you’re in an intimate relationship, and don’t want the person you’re conversing with to know about it. You might pull out your knowledge of Middle English and say you’re “giving a girl a green gown.” Or, you might simply say you’re rolling in the hay with someone, to communicate your relationship while also communicating you don’t want to talk about it.

Note: even “intimate relationship” is a bit of a euphemism!

In dialogue writing, use euphemisms as hints to your characters’ psyches. In speech, what is omitted often says more than what is included.

A proverb is a short, oft-repeated saying that bears a wise and powerful message. Proverbs are often based on common sense advice, but they use metaphors and symbols to convey that advice, prompting the listener to place themselves in the world of the proverb.

For example, a common English proverb is “a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.” This means that it’s better to take away modest gains than to sacrifice those gains for something that may be unobtainable. Sacrificing the bird in your hand for two birds which may be impossible to own is a risky endeavor.

When it comes to writing dialogue in a story, proverbs educate both the protagonist and the audience. A proverb will often be spoken by an elder or someone with relevant experience to help guide the protagonist. The story’s events might also be a reaction to that proverb, either fulfilling or complicating it. Finally, a proverb might characterize the speaker themselves, cluing the reader into the speaker’s beliefs. Not all stories have proverbs, but stories with wise characters often do.

9. Neologism

A neologism is a coined word that describes something new. Some neologisms are coined by authors themselves—Shakespeare, for example, coined over 2,000 words, many of which we use today. “Baseless,” “footfall,” and “murkiest” come from The Tempest , just one of Shakespeare’s many plays and poems.

Nowadays, most neologisms describe advancements in technology, medicine, and society. “Doomscrolling,” for example, describes the act of consuming large quantities of negative news, often to the detriment of one’s mental health. The word was likely invented in 2018, due in part to the increased access to information that technology gives us.

Other modern day neologisms include:

- Google (as a verb: to google something)

- Crowdsourcing

Some neologisms are portmanteaus, which is a word made from two other words combined in both sound and meaning. For example, “smog” is a portmanteau of “smoke and fog,” and it’s a neologism only relevant to the Industrial Revolution and beyond.

Neologisms are not to be confused with grandiloquent words , which are invented words used for the sole purpose of sounding intelligent (and which have become enduring facets of modern English).

In dialogue writing, neologisms primarily help situate the reader in the story’s temporal setting. No one would use the word malware in the year 1920. Additionally, words like “crowdsourcing” are far more likely to be used by younger generations, and they signify a certain sense of tech savviness and modernity that not everyone has.

Finally, neologisms are fun! You might even invent some new words in your own writing, though a neologism should be elegant and relevant, without drawing too much attention to itself.

Of course, the best way to learn how to write dialogue in a story is to practice it yourself. Below are some dialogue writing exercises to try in your fiction.

Dialogue Writing Exercise: Write out a character’s “personal vocabulary.”

All of us have a personal vocabulary, meaning that we tend to choose the same set of words to describe something, even though our vocabularies are much larger. For example, I have a tendency to use the word “scandalous” when describing something. I often use it ironically or as a compliment, which is a trait of word-usage associated with Millennials and older Gen Z kids. This word is a part of my personal vocabulary, and though I don’t say it constantly, I often use it when I can’t think of a better word.

Your characters are the same way! Writing out a personal vocabulary for your characters might jumpstart your dialogue writing, and it also gives you something to fall back on in your dialogue while still providing depth and character.

Coming back—once again—to Holden Caulfield, his personal vocabulary might include words like: phony , prostitute , goddam , miserable , lousy , jerk . These words and phrases are rare overall, but they’re exceedingly common in his own personal way of verbalizing his experience of the world.

Dialogue Writing Exercise: Consider different settings.

Sometimes, you just need to generate dialogue until you come across the right line or turn-of-phrase. One way to do that is to write what your character would say in different situations.

On a separate document or piece of paper, write what would happen if your character was talking to different people or talking in different situations. For example, your character might:

- Talk to a grocery store clerk

- Be a hostage in a bank robbery

- Take the SAT

- Run into their crush

- Get pulled over for speeding

Explore what your character would say in each of these (and other) different scenarios, and you might just trick your brain into writing the next sentence of your story.

Dialogue Writing Exercise: Pretend you are your character.

Instead of writing your character in different settings, be your character in different settings. Think about what your character would think while you’re doing the laundry, driving to work, or paying the bills. This habit will help you approach this character’s dialogue, as you develop the ability to turn their personality on in your brain, like a switch!

(Hopefully, you’re never caught in a bank robbery. If you are, maybe your character can save you.)

We’ve covered how to write dialogue in a story, but not how to format dialogue. Dialogue formatting is a relatively minor concern for fiction writers, but it’s still important to format correctly. Otherwise, you’ll waste hours of your writing time trying to fix formatting errors, and you might prevent your stories from finding publication.

There are a few different ways to format dialogue; for each of these examples, we will reformat the sentence “You’re gonna need a bigger boat,” said Chief Brody.

Most writers and publishers use standard quotation marks at the beginning and end of the dialogue.

“You’re gonna need a bigger boat,” said Chief Brody.

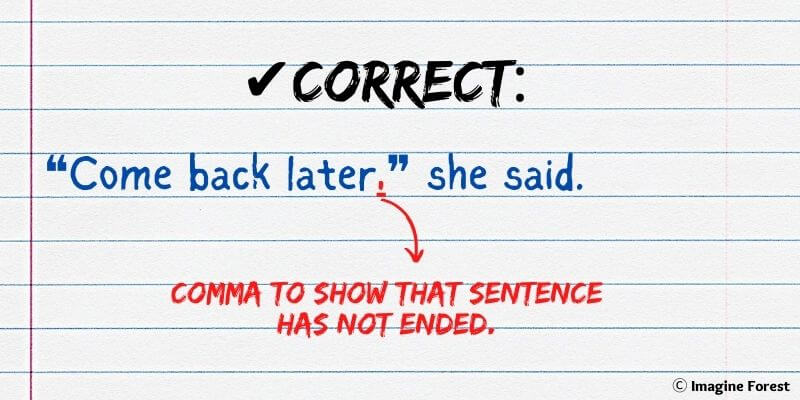

A comma always separates the dialogue from the speaker. In this case, the comma goes inside of the quotation marks. Periods, semicolons, and em dashes also go inside the quotation marks. If you’re writing in British English, some conventions place the dialogue punctuation outside of the quotation, but both ways are acceptable.

Another way some people format their dialogue is by italicizing instead of using quotation marks.

You’re gonna need a bigger boat, said Chief Brody.

In this instance, you would fit the comma within the italicized text, as you would any other punctuation in the dialogue. Only the quote is italicized; the speaker remains unitalicized. The drawback of this formatting is that your dialogue might be confused with the character’s inner dialogue, which should also be italicized.

Finally, your dialogue formatting can eschew the use of quotation marks and italics. In this case, you would indent any part of the text that is dialogue, and leave narration un-indented.

Suddenly, the shark loomed behind the orca.

This way of formatting makes it easier to write without worrying about punctuation marks, but be warned that most publishers will change that formatting before publication.

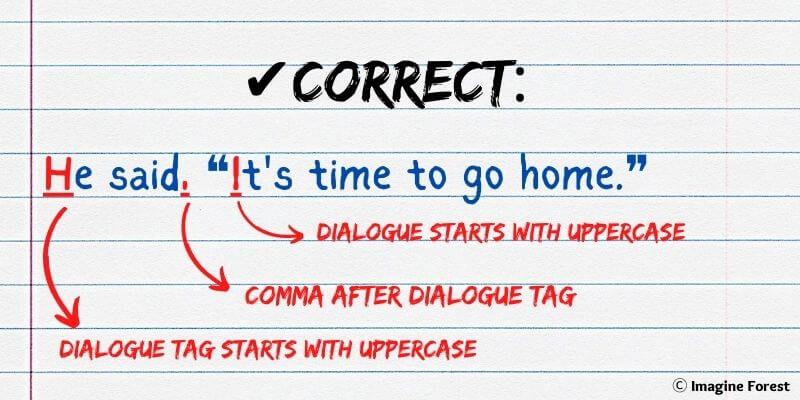

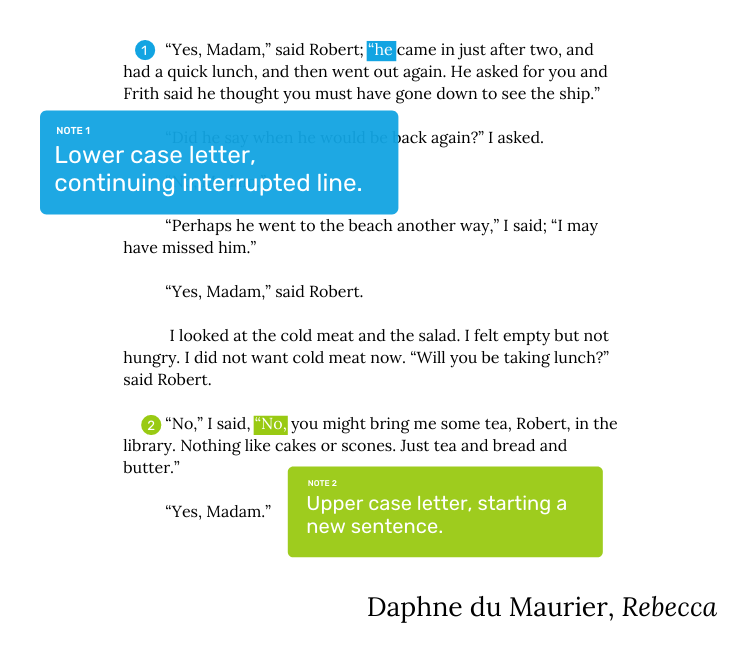

If your sentence starts with the dialogue tag, put a comma before the quotation mark. Do capitalize the first letter inside the quotation marks, as this is, grammatically, the start of a sentence.

Chief Brody said, “You’re gonna need a bigger boat.”

And, if your dialogue spans multiple paragraphs, do not use the end-quote until the very end of the dialogue, but start each paragraph with a new start-quote.

“You’re gonna need a bigger boat. “A boat this size can’t handle a shark,” Chief Brody continued.

Looking for More Dialogue Writing Tips?

Great dialogue is the true test of whether you understand your characters or not. However, developing this skill takes a lot of time and practice. If you’re looking for more advice on how to write dialogue in a story, check out our online fiction writing courses for dialogue writing tips from the best instructors on the net!

Sean Glatch

10 comments.

This was very helpful: I’m a French Canadian, living here in the US for the past 28 years, very fluent in English and this article will help me to polish my stories telling. I love to write spending a lot of time doing so, whether it’s a story, an email, documentation in my field (I’m an IT guy) and I’m now more confident about my writing.

I’m so happy to hear that, Richard. Happy writing!

As an aspiring writer, this helped me a lot!

Great article! Nice job capturing so many elements and explaining things so well. I enjoyed it from beginning to end.

The only thing that puzzled me was in the following section (watch for the **):

If your sentence starts with the dialogue tag, put a comma before the quotation mark. **In this case, do not capitalize the first letter inside the quotation marks.**

Chief Brody said, “you’re gonna need a bigger boat.”

I’ve never seen that guidance before. I thought you were supposed to capitalize the first word of complete dialogue sentences regardless of speaker attribution placement. Might this be a mistake? Or a vestige from a previous edit?

You’re absolutely right–that bit of advice was written in error. The start of a new sentence of dialogue should always begin with a capital letter. I’ve updated the text accordingly. Many thanks for your comment!

[…] How to Write Dialogue in a Story […]

Thank you, Nicole! I’m so glad you found it helpful. Happy writing!

Directed here from somewhere else. A novice when it comes to fiction writing and the proper use of English. I fid dialogue my most difficult in writing. I am glad for this. I get most of the gist now.

I came across your website while doing some research for my writing students and I have to say this is one of the best resources I’ve found when it comes to writing dialogue. Thank you for taking the time to put together such a valuable resource and one which I’ll be passing on to my students.

Thank you again!

Really great advice. One thing I often do is get my students to ‘capture conversations’ so they can hear the cadence of real dialogue. Then we look at how to make it more powerful by taking out most if not all of the ‘um’s, ah’s’ and other interruptions or interjections. It has improved the quality of my students written dialogue immensely. 🙂

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- How-To Guides

How To Write Dialogue In A Story (With Examples)

One of the biggest mistakes made by writers is how they use dialogue in their stories. Today, we are going to teach you how to write dialogue in a story using some easy and effective techniques. So, get ready to learn some of the best techniques and tips for writing dialogue!

There are two main reasons why good dialogue is so important in works of fiction. First, good dialogue helps keep the reader interested and engaged in the story. Second, it makes your work easier to write, read and understand. So, if you want to write dialogue that is interesting, engaging and easy to read, keep on reading. We will be teaching you the best techniques and tips for writing dialogue in a story.

Internal vs External Dialogue

Direct vs indirect dialogue, 20 tips for formatting dialogue in stories, step 1: use a dialogue outline, step 2: write down a script, step 3: edit & review your script, step 4: sprinkle in some narrative, step 5: format your dialogue, what is dialogue .

Dialogue is the spoken words that are spoken between the characters of a story. It is also known as the conversation between the characters. Dialogue is a vital part of a story. It is the vehicle of the characters’ thoughts and emotions. Good dialogue helps show the reader how the characters think and feel. It also helps the reader better understand what is happening in the story. Good dialogue should be interesting, informative and natural.

In a story, dialogue can be expressed internally as thoughts, or externally through conversations between characters. A character thinking to themself would be considered internal dialogue. Here there is no one else, just one character thinking or speaking to themselves:

Mary thought to herself, “what if I can do better…”

While two or more characters talking to each other in a scene would be an external dialogue:

“Watch out!” cried Sam. “What’s wrong with you?” laughed Kate.

In most cases, the words spoken by your character will be inside quotation marks. This is called direct dialogue. And then everything outside the quotation marks is called narrative:

“What do you want?” shrieked Penelope as she grabbed her notebooks. “Oh, nothing… Just checking if you needed anything,” sneered Peter as he tried to peek over at her notes.

Indirect dialogue is a summary of your dialogue. It lets the reader know that a conversation happened without repeating it exactly. For example:

She was still fuming from last night’s argument. After being called a liar and a thief, she had no choice but to leave home for good.

Direct dialogue is useful for quick conversations, while indirect dialogue is useful for summarising long pieces of dialogue. Which otherwise can get boring for the reader. Writers can combine both types of dialogue to increase tension and add drama to their stories.

Now you know some of the different types of dialogue in stories, let’s learn how to write dialogue in a story.

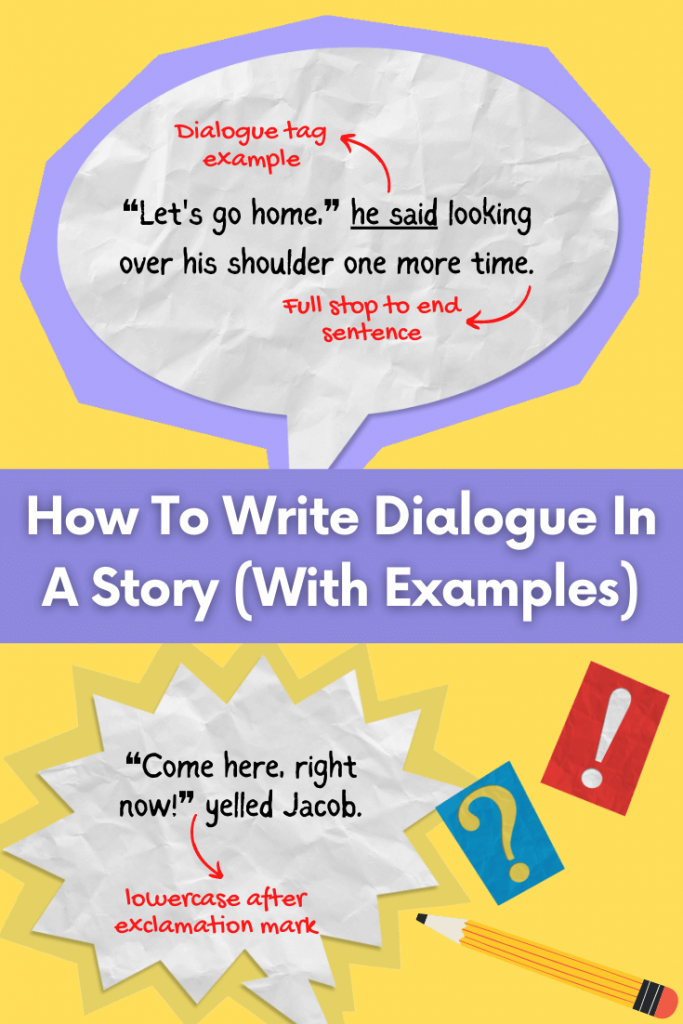

Here are the main tips to remember when formatting dialogue in stories or works of fiction:

- Always use quotation marks: All direct dialogue is written inside quotation marks, along with any punctuation relating to that dialogue.

- Don’t forget about dialogue tags: Dialogue tags are used to explain how a character said something. Each tag has at least one noun or pronoun, and one verb indicating how the dialogue is spoken. For example, he said, she cried, they laughed and so on.

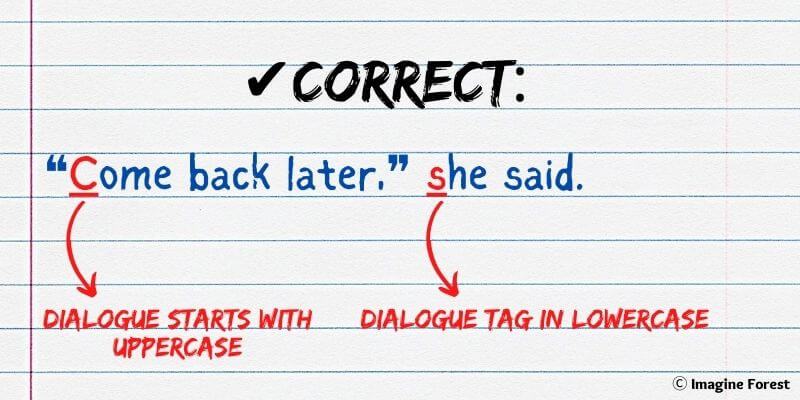

- Dialogue before tags: Dialogue before the dialogue tags should start with an uppercase. The dialogue tag itself begins with a lowercase.

- Dialogue after tags: Both the dialogue and dialogue tags start with an uppercase to signify the start of a conversation. The dialogue tags also have a comma afterwards, before the first set of quotation marks.

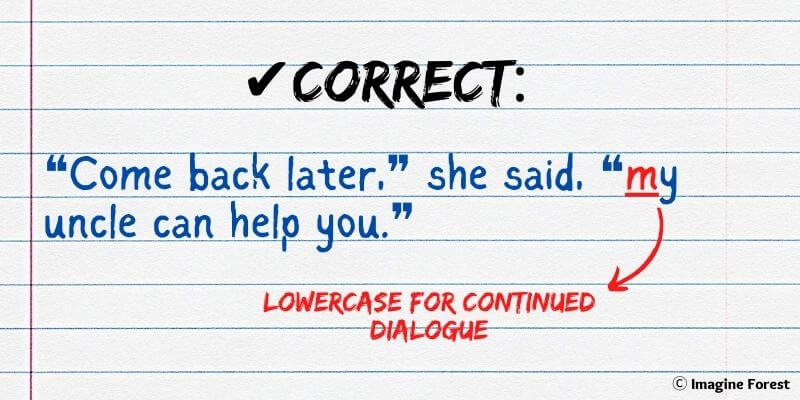

- Lowercase for continued dialogue: If the same character continues to speak after the dialogue tags or action, then this dialogue continues with a lowercase.

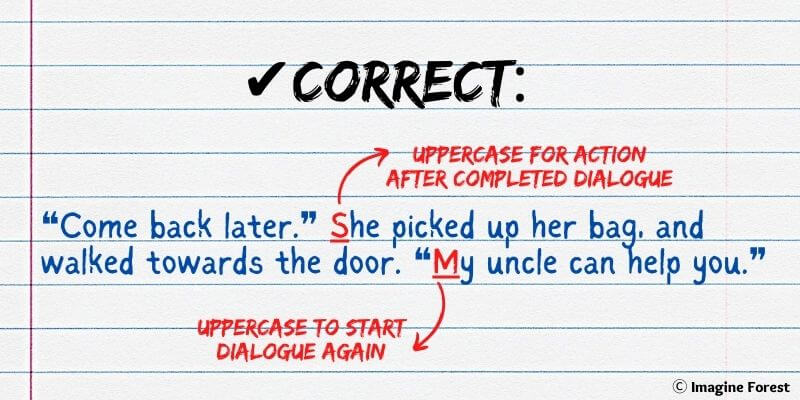

- Action after complete dialogue: Any action or narrative text after completed dialogue starts with an uppercase as a new sentence.

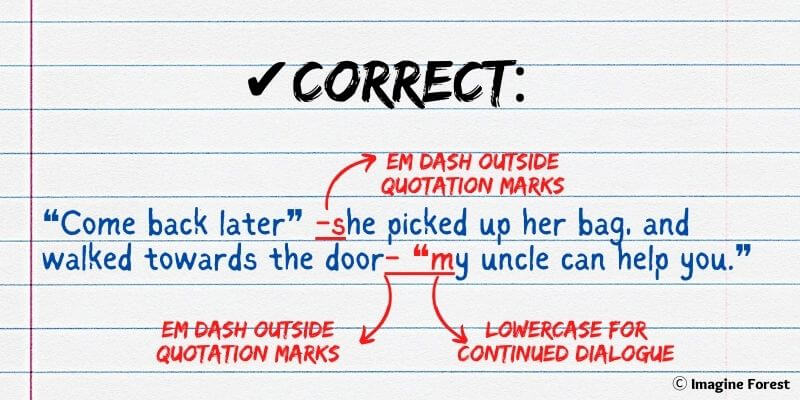

- Action interrupting dialogue: If the same character pauses their dialogue to do an action, then this action starts with a lowercase.

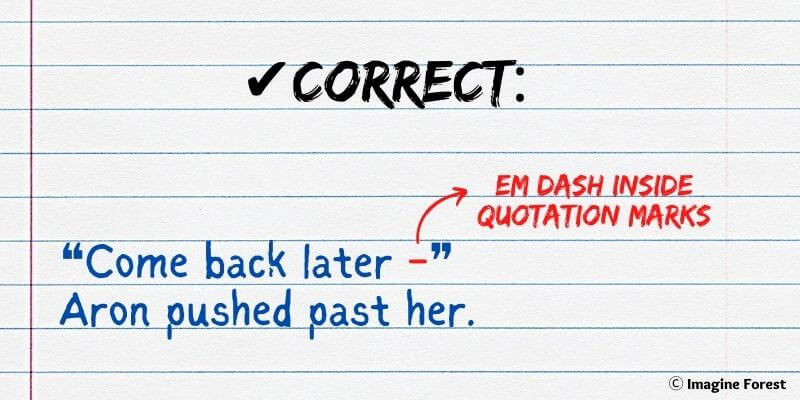

- Interruptions by other characters: If another character Interrupts a character’s dialogue, then their action starts with an uppercase on a new line. And an em dash (-) is used inside the quotation marks of the dialogue that was interrupted.

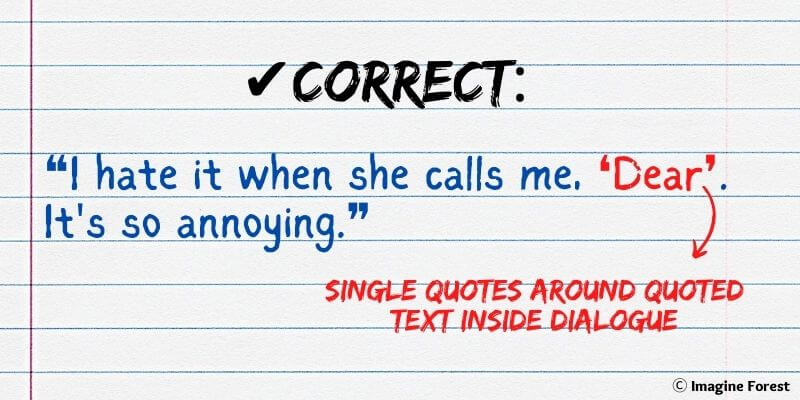

- Use single quotes correctly: Single quotes mean that a character is quoting someone else.

- New paragraphs equal new speaker: When a new character starts speaking, it should be written in a new paragraph.

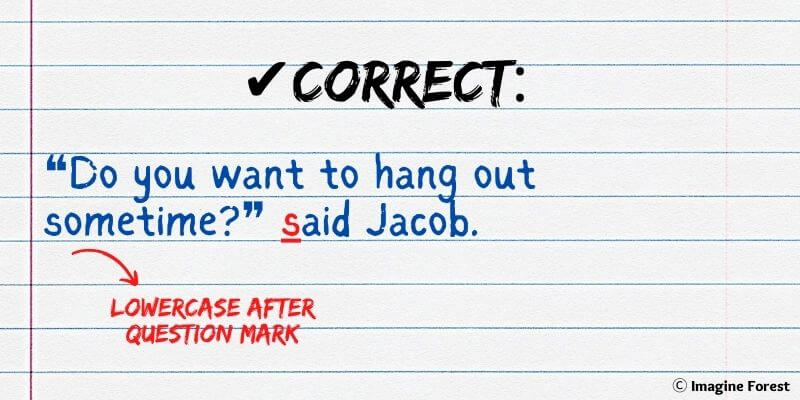

- Use question marks correctly: If the dialogue ends with a question mark, then the part after the dialogue should begin with a lowercase.

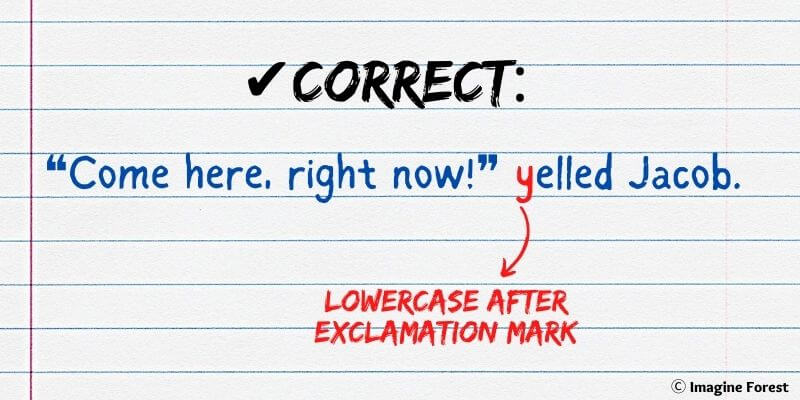

- Exclamation marks: Similar to question marks, the next sentence should begin with a lowercase.

- Em dashes equal being cut off: When a character has been interrupted or cut off in the middle of their speech, use an em dash (-).

- Ellipses mean trailing speech: When a character is trailing off in their speech or going on and on about something use ellipses (…). This is also good to use when a character does not know what to say.

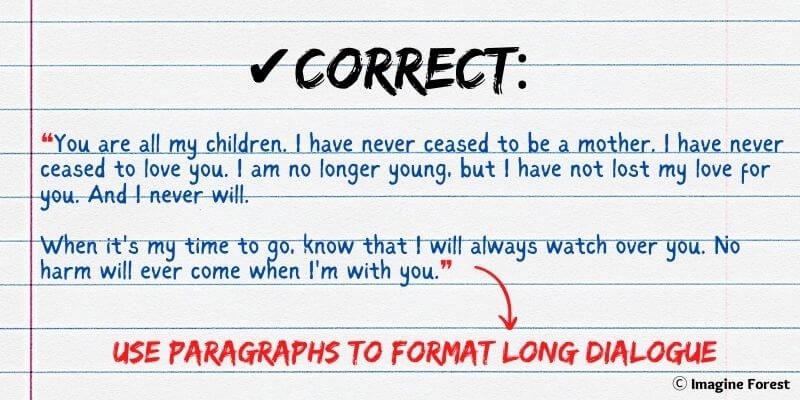

- Spilt long dialogue into paragraphs: If a character is giving a long speech, then you can split this dialogue into multiple paragraphs.

- Use commas appropriately: If it is not the end of the sentence then end the dialogue with a comma.

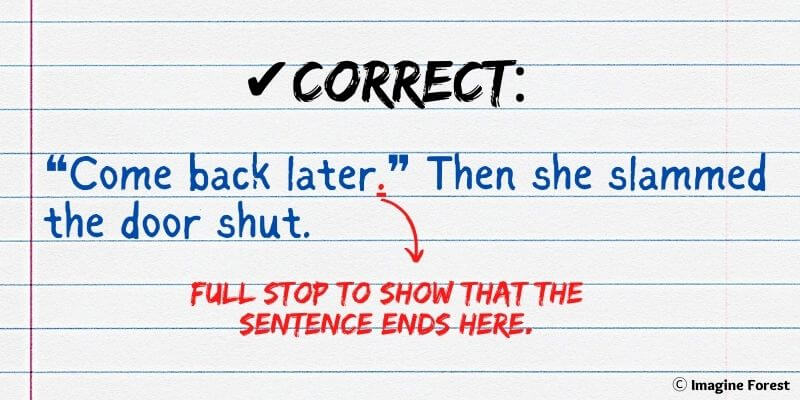

- Full stops to end dialogue: Dialogue ending with a full stop means it is the end of the entire sentence.

- Avoid fancy dialogue tags: For example, ‘he moderated’ or ‘she articulated’. As this can distract the reader from what your characters are actually saying and the content of your story. It’s better to keep things simple, such as using he said or she said.

- No need for names: Avoid repeating your character’s name too many times. You could use pronouns or even nicknames.

- Keep it informal: Think about how real conversations happen. Do people use technical or fancy language when speaking? Think about your character’s tone of voice and personality, what would they say in a given situation?

Remember these rules, and you’ll be able to master dialogue writing in no time!

How to Write Dialogue in 5 Steps

Dialogue is tricky. Follow these easy steps to write effective dialogue in your stories or works of fiction:

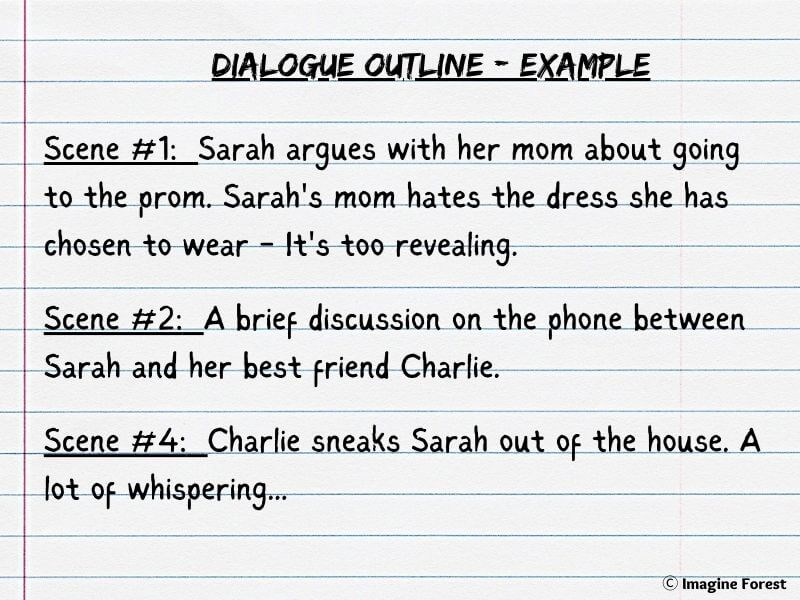

A dialogue outline is a draft of what your characters will say before you actually write the dialogue down. This draft can be in the form of notes or any scribblings about your planned dialogue. Using your overall book outline , you can pinpoint the areas where you expect to see the most dialogue used in your story. You can then plan out the conversation between characters in these areas.

A good thing about using a dialogue outline is that you can avoid your characters saying the same thing over and over again. You can also skim out any unnecessary dialogue scenes if you think they are unnecessary or pointless.

Here is an example of a dialogue outline for a story:

You even use a spreadsheet to outline your story’s dialogue scenes.

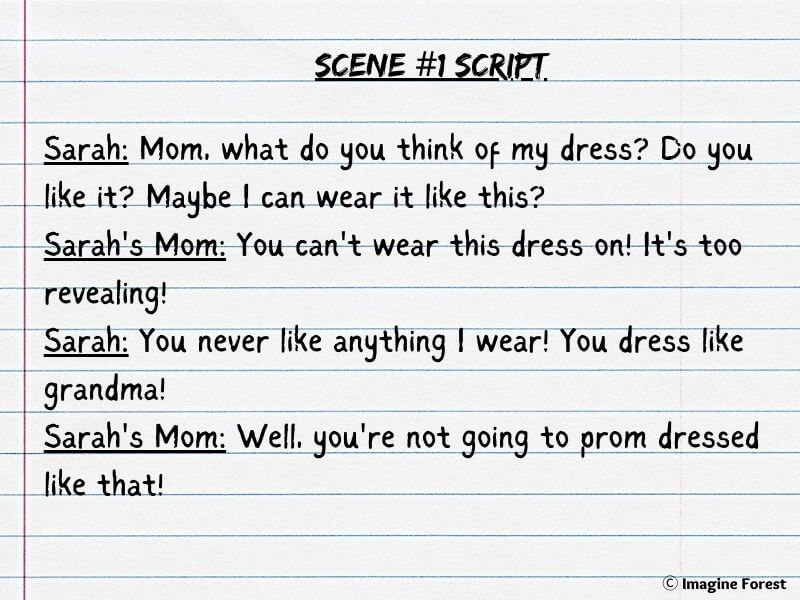

In this step, you will just write down what the characters are saying in full. Don’t worry too much about punctuation and the correct formatting of dialogue. The purpose of this step is to determine what the characters will actually say in the scene and whether this provides any interesting information to your readers.

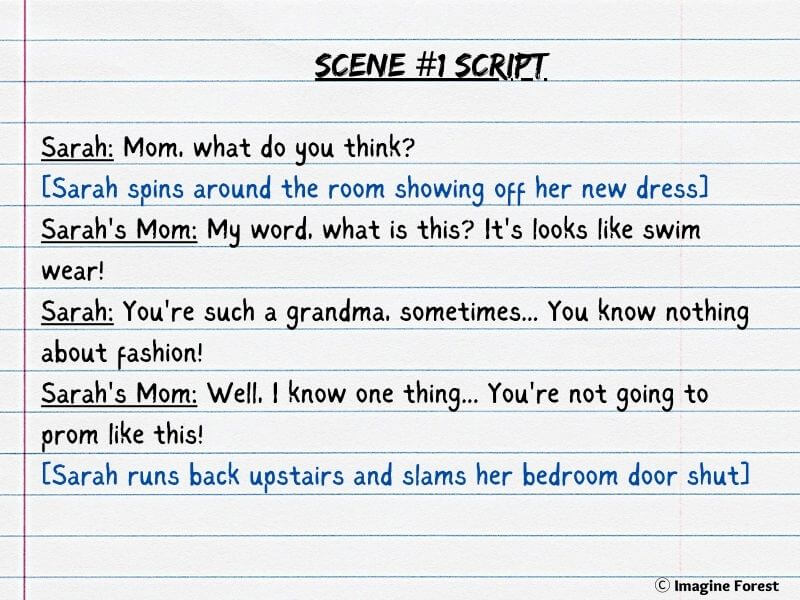

Start by writing down the full script of your character’s conversations for each major dialogue scene in your story. Here is an example of a dialogue script for a story:

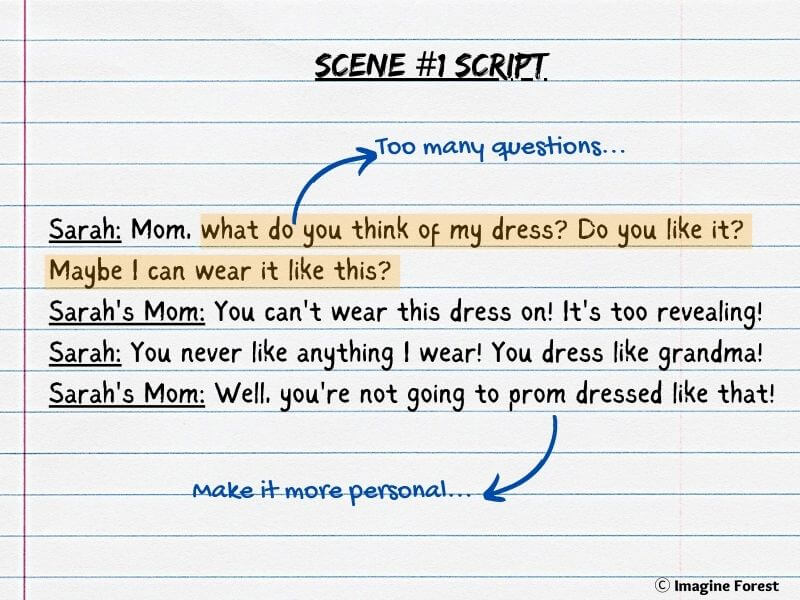

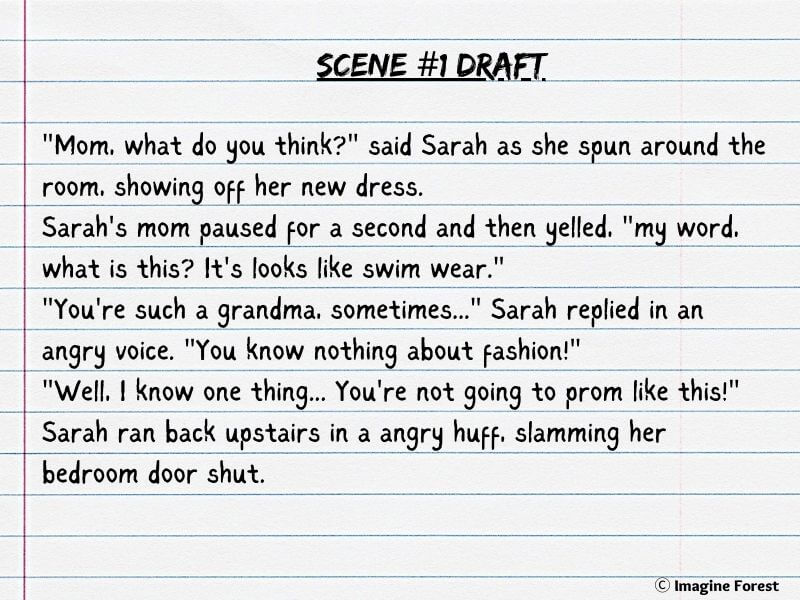

Review your script from the previous step, and think about how it can be shortened or made more interesting. You might think about changing a few words that the characters use to make it sound more natural. Normally the use of slang words and informal language is a great way to make dialogue between characters sound more natural. You might also think about replacing any names with nicknames that characters in a close relationship would use.

The script might also be too long with plenty of unnecessary details that can be removed or summarised as part of the narration in your story (or as indirect dialogue). Remember the purpose of dialogue is to give your story emotion and make your characters more realistic. At this point you might also want to refer back to your character profiles , to see if the script of each character matches their personality.

Once your script has been perfected, you can add some actions to make your dialogue feel more believable to readers. Action or narrative is the stuff that your characters are actually doing throughout or in between dialogue. For example, a character might be packing up their suitcase, as they are talking about their holiday plans. This ‘narrative’ is a great way to break up a long piece of dialogue which otherwise could become boring and tedious for readers.

You have now planned your dialogue for your story. The final step is to incorporate these dialogue scenes into your story. Remember to follow our formatting dialogue formatting rules explained above to create effective dialogue for your stories!

That’s all for today! We hope this post has taught you how to write dialogue in a story effectively. If you have any questions, please let us know in the comments below!

Marty the wizard is the master of Imagine Forest. When he's not reading a ton of books or writing some of his own tales, he loves to be surrounded by the magical creatures that live in Imagine Forest. While living in his tree house he has devoted his time to helping children around the world with their writing skills and creativity.

Related Posts

Comments loading...

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

How to Write Dialogue: 7 Great Tips for Writers (With Examples)

Hannah Yang

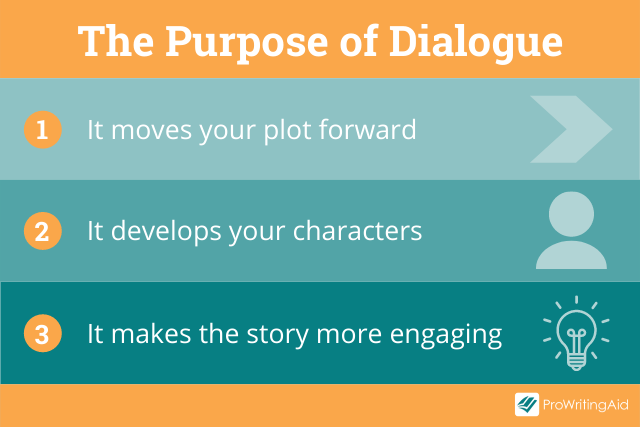

Great dialogue serves multiple purposes. It moves your plot forward. It develops your characters and it makes the story more engaging.

It’s not easy to do all these things at once, but when you master the art of writing dialogue, readers won’t be able to put your book down.

In this article, we will teach you the rules for writing dialogue and share our top dialogue tips that will make your story sing.

Dialogue Rules

How to format dialogue, 7 tips for writing dialogue in a story or book, dialogue examples.

Before we look at tips for writing powerful dialogue , let’s start with an overview of basic dialogue rules.

- Start a new paragraph each time there’s a new speaker. Whenever a new character begins to speak, you should give them their own paragraph. This rule makes it easier for the reader to follow the conversation.

- Keep all speech between quotation marks . Everything that a character says should go between quotation marks, including the final punctuation marks. For example, periods and commas should always come before the final quotation mark, not after.

- Don’t use end quotations for paragraphs within long speeches. If a single character speaks for such a long time that you break their speech up into multiple paragraphs, you should omit the quotation marks at the end of each paragraph until they stop talking. The final quotation mark indicates that their speech is over.

- Use single quotes when a character quotes someone else. Whenever you have a quote within a quote, you should use single quotation marks (e.g. She said, “He had me at ‘hello.’”)

- Dialogue tags are optional. A dialogue tag is anything that indicates which character is speaking and how, such as “she said,” “he whispered,” or “I shouted.” You can use dialogue tags if you want to give the reader more information about who’s speaking, but you can also choose to omit them if you want the dialogue to flow more naturally. We’ll be discussing more about this rule in our tips below.

Let’s walk through some examples of how to format dialogue .

The simplest formatting option is to write a line of speech without a dialogue tag. In this case, the entire line of speech goes within the quotation marks, including the period at the end.

- Example: “I think I need a nap.”

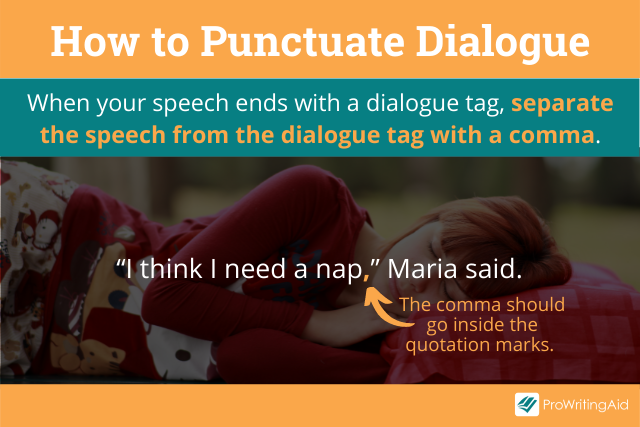

Another common formatting option is to write a single line of speech that ends with a dialogue tag.

Here, you should separate the speech from the dialogue tag with a comma, which should go inside the quotation marks.

- Example: “I think I need a nap,” Maria said.

You can also write a line of speech that starts with a dialogue tag. Again, you separate the dialogue tag with a comma, but this time, the comma goes outside the quotation marks.

- Example: Maria said, “I think I need a nap.”

As an alternative to a simple dialogue tag, you can write a line of speech accompanied by an action beat. In this case, you should use a period rather than a comma, because the action beat is a full sentence.

- Example: Maria sat down on the bed. “I think I need a nap.”

Finally, you can choose to include an action beat while the character is talking.

In this case, you would use em-dashes to separate the action from the dialogue, to indicate that the action happens without a pause in the speech.

- Example: “I think I need”—Maria sat down on the bed—“a nap.”

Now that we’ve covered the basics, we can move on to the more nuanced aspects of writing dialogue.

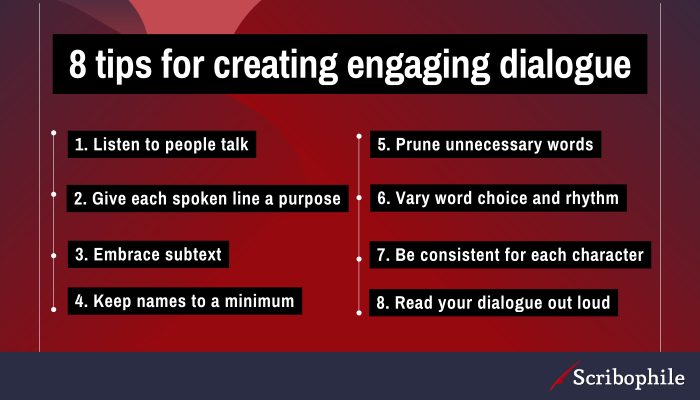

Here are our seven favorite tips for writing strong, powerful dialogue that will keep your readers engaged.

Tip #1: Create Character Voices

Dialogue is a great way to reveal your characters. What your characters say, and how they say it, can tell us so much about what kind of people they are.

Some characters are witty and gregarious. Others are timid and unobtrusive.

Speech patterns vary drastically from person to person.

To make someone stop talking to them, one character might say “I would rather not talk about this right now,” while another might say, “Shut your mouth before I shut it for you.”

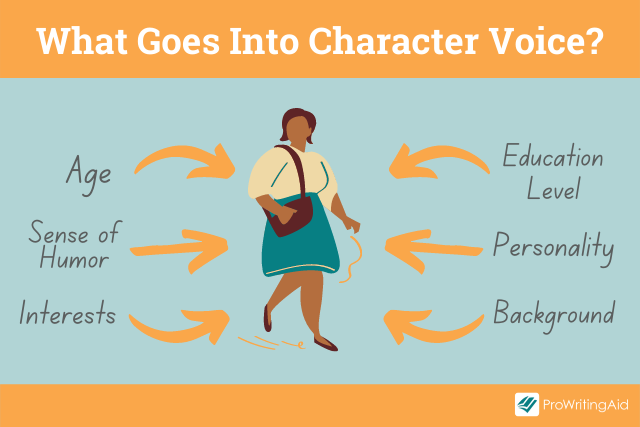

When you’re writing dialogue, think about your character’s education level, personality, and interests.

- What kind of slang do they use?

- Do they prefer long or short sentences?

- Do they ask questions or make assertions?

Each character should have their own voice.

Ideally, you want to write dialogue that lets your reader identify the person speaking at any point in your story just by looking at what’s between the quotation marks.

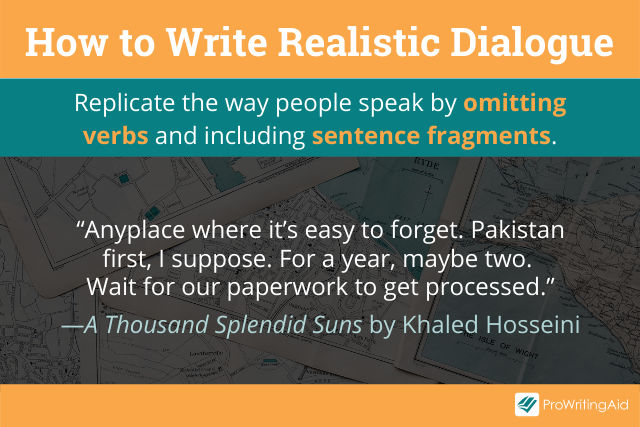

Tip #2: Write Realistic Dialogue

Good dialogue should sound natural. Listen to how people talk in real life and try to replicate it on the page when you write dialogue.

Don’t be afraid to break the rules of grammar, or to use an occasional exclamation point to punctuate dialogue.

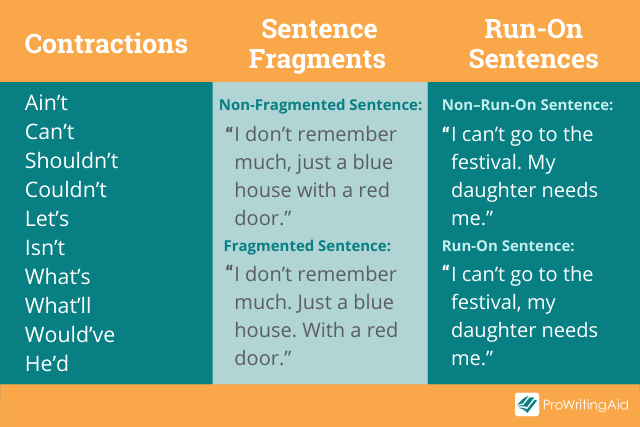

It’s okay to use contractions , sentence fragments , and run-on sentences , even if you wouldn’t use them in other parts of the story.

This doesn’t mean that realistic dialogue should sound exactly like the way people speak in the real world.

If you’ve ever read a court transcript, you know that real-life speech is riddled with “ums” and “ahs” and repeated words and phrases. A few paragraphs of this might put your readers to sleep.

Compelling dialogue should sound like a real conversation, while still being wittier, smoother, and better worded than real speech.

Tip #3: Simplify Your Dialogue Tags

A dialogue tag is anything that tells the reader which character is talking within that same paragraph, such as “she said” or “I asked.”

When you’re writing dialogue, remember that simple dialogue tags are the most effective .

Often, you can omit dialogue tags after the conversation has started flowing, especially if only two characters are participating.

The reader will be able to keep up with who’s speaking as long as you start a new paragraph each time the speaker changes.

When you do need to use a dialogue tag, a simple “he said” or “she said” will do the trick.

Our brains generally skip over the word “said” when we’re reading, while other dialogue tags are a distraction.

A common mistake beginner writers make is to avoid using the word “said.”

Characters in amateur novels tend to mutter, whisper, declare, or chuckle at every line of dialogue. This feels overblown and distracts from the actual story.

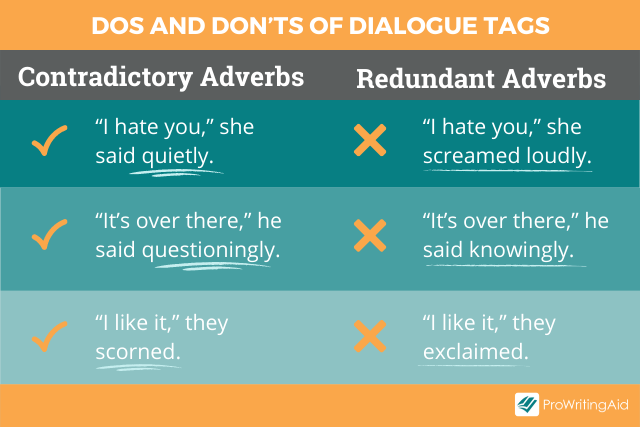

Another common mistake is to attach an adverb to the word “said.” Characters in amateur novels rarely just say things—they have to say things loudly, quietly, cheerfully, or angrily.

If you’re writing great dialogue, readers should be able to figure out whether your character is cheerful or angry from what’s within the quotation marks.

The only exception to this rule is if the dialogue tag contradicts the dialogue itself. For example, consider this sentence:

- “You’ve ruined my life,” she said angrily.

The word “angrily” is redundant here because the words inside the quotation marks already imply that the character is speaking angrily.

In contrast, consider this sentence:

- “You’ve ruined my life,” she said thoughtfully.

Here, the word “thoughtfully” is well-placed because it contrasts with what we might otherwise assume. It adds an additional nuance to the sentence inside the quotation marks.

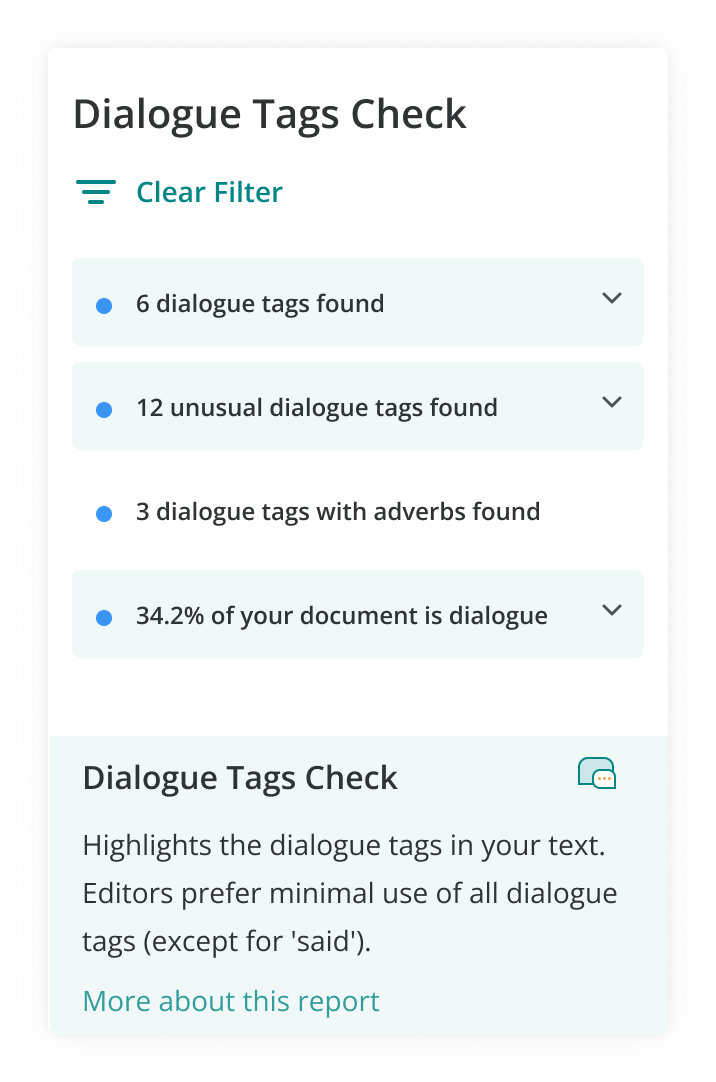

You can use the ProWritingAid dialogue check when you write dialogue to make sure your dialogue tags are pulling their weight and aren’t distracting readers from the main storyline.

Sign up for your free ProWritingAid account to check your dialogue tags today.

Tip #4: Balance Speech with Action

When you’re writing dialogue, you can use action beats —descriptions of body language or physical action—to show what each character is doing throughout the conversation.

Learning how to write action beats is an important component of learning how to write dialogue.

Good dialogue becomes even more interesting when the characters are doing something active at the same time.

You can watch people in real life, or even characters in movies, to see what kinds of body language they have. Some pick at their fingernails. Some pace the room. Some tap their feet on the floor.

Including physical action when writing dialogue can have multiple benefits:

- It changes the pace of your dialogue and makes the rhythm more interesting

- It prevents “white room syndrome,” which is when a scene feels like it’s happening in a white room because it’s all dialogue and no description

- It shows the reader who’s speaking without using speaker tags

You can decide how often to include physical descriptions in each scene. All dialogue has an ebb and flow to it, and you can use beats to control the pace of your dialogue scenes.

If you want a lot of tension in your scene, you can use fewer action beats to let the dialogue ping-pong back and forth.

If you want a slower scene, you can write dialogue that includes long, detailed action beats to help the reader relax.

You should start a separate sentence, or even a new paragraph, for each of these longer beats.

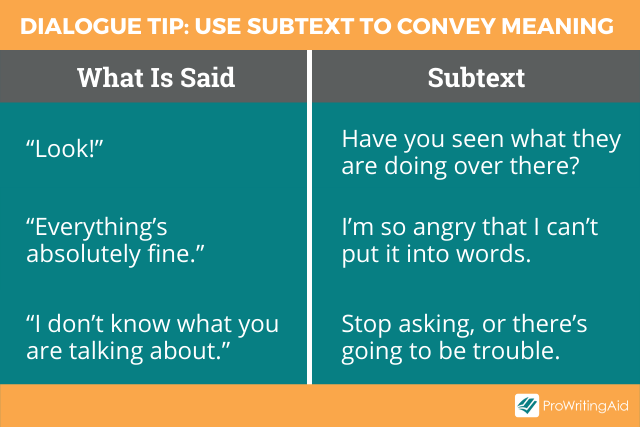

Tip #5: Write Conversations with Subtext

Every conversation has subtext , because we rarely say exactly what we mean. The best dialogue should include both what is said and what is not said.