Literature Syntheis 101

How To Synthesise The Existing Research (With Examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | August 2023

One of the most common mistakes that students make when writing a literature review is that they err on the side of describing the existing literature rather than providing a critical synthesis of it. In this post, we’ll unpack what exactly synthesis means and show you how to craft a strong literature synthesis using practical examples.

This post is based on our popular online course, Literature Review Bootcamp . In the course, we walk you through the full process of developing a literature review, step by step. If it’s your first time writing a literature review, you definitely want to use this link to get 50% off the course (limited-time offer).

Overview: Literature Synthesis

- What exactly does “synthesis” mean?

- Aspect 1: Agreement

- Aspect 2: Disagreement

- Aspect 3: Key theories

- Aspect 4: Contexts

- Aspect 5: Methodologies

- Bringing it all together

What does “synthesis” actually mean?

As a starting point, let’s quickly define what exactly we mean when we use the term “synthesis” within the context of a literature review.

Simply put, literature synthesis means going beyond just describing what everyone has said and found. Instead, synthesis is about bringing together all the information from various sources to present a cohesive assessment of the current state of knowledge in relation to your study’s research aims and questions .

Put another way, a good synthesis tells the reader exactly where the current research is “at” in terms of the topic you’re interested in – specifically, what’s known , what’s not , and where there’s a need for more research .

So, how do you go about doing this?

Well, there’s no “one right way” when it comes to literature synthesis, but we’ve found that it’s particularly useful to ask yourself five key questions when you’re working on your literature review. Having done so, you can then address them more articulately within your actual write up. So, let’s take a look at each of these questions.

1. Points Of Agreement

The first question that you need to ask yourself is: “Overall, what things seem to be agreed upon by the vast majority of the literature?”

For example, if your research aim is to identify which factors contribute toward job satisfaction, you’ll need to identify which factors are broadly agreed upon and “settled” within the literature. Naturally, there may at times be some lone contrarian that has a radical viewpoint , but, provided that the vast majority of researchers are in agreement, you can put these random outliers to the side. That is, of course, unless your research aims to explore a contrarian viewpoint and there’s a clear justification for doing so.

Identifying what’s broadly agreed upon is an essential starting point for synthesising the literature, because you generally don’t want (or need) to reinvent the wheel or run down a road investigating something that is already well established . So, addressing this question first lays a foundation of “settled” knowledge.

Need a helping hand?

2. Points Of Disagreement

Related to the previous point, but on the other end of the spectrum, is the equally important question: “Where do the disagreements lie?” .

In other words, which things are not well agreed upon by current researchers? It’s important to clarify here that by disagreement, we don’t mean that researchers are (necessarily) fighting over it – just that there are relatively mixed findings within the empirical research , with no firm consensus amongst researchers.

This is a really important question to address as these “disagreements” will often set the stage for the research gap(s). In other words, they provide clues regarding potential opportunities for further research, which your study can then (hopefully) contribute toward filling. If you’re not familiar with the concept of a research gap, be sure to check out our explainer video covering exactly that .

3. Key Theories

The next question you need to ask yourself is: “Which key theories seem to be coming up repeatedly?” .

Within most research spaces, you’ll find that you keep running into a handful of key theories that are referred to over and over again. Apart from identifying these theories, you’ll also need to think about how they’re connected to each other. Specifically, you need to ask yourself:

- Are they all covering the same ground or do they have different focal points or underlying assumptions ?

- Do some of them feed into each other and if so, is there an opportunity to integrate them into a more cohesive theory?

- Do some of them pull in different directions ? If so, why might this be?

- Do all of the theories define the key concepts and variables in the same way, or is there some disconnect? If so, what’s the impact of this ?

Simply put, you’ll need to pay careful attention to the key theories in your research area, as they will need to feature within your theoretical framework , which will form a critical component within your final literature review. This will set the foundation for your entire study, so it’s essential that you be critical in this area of your literature synthesis.

If this sounds a bit fluffy, don’t worry. We deep dive into the theoretical framework (as well as the conceptual framework) and look at practical examples in Literature Review Bootcamp . If you’d like to learn more, take advantage of our limited-time offer to get 60% off the standard price.

4. Contexts

The next question that you need to address in your literature synthesis is an important one, and that is: “Which contexts have (and have not) been covered by the existing research?” .

For example, sticking with our earlier hypothetical topic (factors that impact job satisfaction), you may find that most of the research has focused on white-collar , management-level staff within a primarily Western context, but little has been done on blue-collar workers in an Eastern context. Given the significant socio-cultural differences between these two groups, this is an important observation, as it could present a contextual research gap .

In practical terms, this means that you’ll need to carefully assess the context of each piece of literature that you’re engaging with, especially the empirical research (i.e., studies that have collected and analysed real-world data). Ideally, you should keep notes regarding the context of each study in some sort of catalogue or sheet, so that you can easily make sense of this before you start the writing phase. If you’d like, our free literature catalogue worksheet is a great tool for this task.

5. Methodological Approaches

Last but certainly not least, you need to ask yourself the question: “What types of research methodologies have (and haven’t) been used?”

For example, you might find that most studies have approached the topic using qualitative methods such as interviews and thematic analysis. Alternatively, you might find that most studies have used quantitative methods such as online surveys and statistical analysis.

But why does this matter?

Well, it can run in one of two potential directions . If you find that the vast majority of studies use a specific methodological approach, this could provide you with a firm foundation on which to base your own study’s methodology . In other words, you can use the methodologies of similar studies to inform (and justify) your own study’s research design .

On the other hand, you might argue that the lack of diverse methodological approaches presents a research gap , and therefore your study could contribute toward filling that gap by taking a different approach. For example, taking a qualitative approach to a research area that is typically approached quantitatively. Of course, if you’re going to go against the methodological grain, you’ll need to provide a strong justification for why your proposed approach makes sense. Nevertheless, it is something worth at least considering.

Regardless of which route you opt for, you need to pay careful attention to the methodologies used in the relevant studies and provide at least some discussion about this in your write-up. Again, it’s useful to keep track of this on some sort of spreadsheet or catalogue as you digest each article, so consider grabbing a copy of our free literature catalogue if you don’t have anything in place.

Bringing It All Together

Alright, so we’ve looked at five important questions that you need to ask (and answer) to help you develop a strong synthesis within your literature review. To recap, these are:

- Which things are broadly agreed upon within the current research?

- Which things are the subject of disagreement (or at least, present mixed findings)?

- Which theories seem to be central to your research topic and how do they relate or compare to each other?

- Which contexts have (and haven’t) been covered?

- Which methodological approaches are most common?

Importantly, you’re not just asking yourself these questions for the sake of asking them – they’re not just a reflection exercise. You need to weave your answers to them into your actual literature review when you write it up. How exactly you do this will vary from project to project depending on the structure you opt for, but you’ll still need to address them within your literature review, whichever route you go.

The best approach is to spend some time actually writing out your answers to these questions, as opposed to just thinking about them in your head. Putting your thoughts onto paper really helps you flesh out your thinking . As you do this, don’t just write down the answers – instead, think about what they mean in terms of the research gap you’ll present , as well as the methodological approach you’ll take . Your literature synthesis needs to lay the groundwork for these two things, so it’s essential that you link all of it together in your mind, and of course, on paper.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

excellent , thank you

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- University of Oregon Libraries

- Research Guides

How to Write a Literature Review

- 6. Synthesize

- Literature Reviews: A Recap

- Reading Journal Articles

- Does it Describe a Literature Review?

- 1. Identify the Question

- 2. Review Discipline Styles

- Searching Article Databases

- Finding Full-Text of an Article

- Citation Chaining

- When to Stop Searching

- 4. Manage Your References

- 5. Critically Analyze and Evaluate

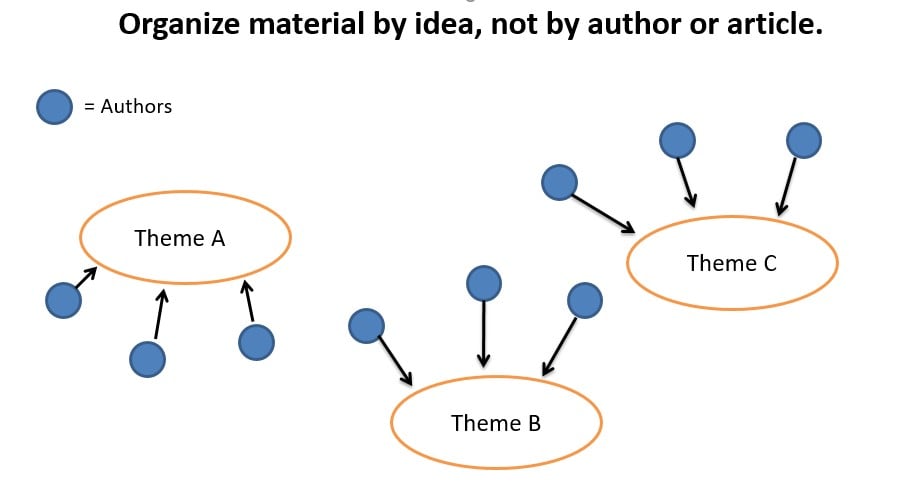

Synthesis Visualization

Synthesis matrix example.

- 7. Write a Literature Review

- Synthesis Worksheet

About Synthesis

Approaches to synthesis.

You can sort the literature in various ways, for example:

How to Begin?

Read your sources carefully and find the main idea(s) of each source

Look for similarities in your sources – which sources are talking about the same main ideas? (for example, sources that discuss the historical background on your topic)

Use the worksheet (above) or synthesis matrix (below) to get organized

This work can be messy. Don't worry if you have to go through a few iterations of the worksheet or matrix as you work on your lit review!

Four Examples of Student Writing

In the four examples below, only ONE shows a good example of synthesis: the fourth column, or Student D . For a web accessible version, click the link below the image.

Long description of "Four Examples of Student Writing" for web accessibility

- Download a copy of the "Four Examples of Student Writing" chart

Click on the example to view the pdf.

From Jennifer Lim

- << Previous: 5. Critically Analyze and Evaluate

- Next: 7. Write a Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: May 3, 2024 5:17 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.uoregon.edu/litreview

Contact Us Library Accessibility UO Libraries Privacy Notices and Procedures

1501 Kincaid Street Eugene, OR 97403 P: 541-346-3053 F: 541-346-3485

- Visit us on Facebook

- Visit us on Twitter

- Visit us on Youtube

- Visit us on Instagram

- Report a Concern

- Nondiscrimination and Title IX

- Accessibility

- Privacy Policy

- Find People

The Sheridan Libraries

- Write a Literature Review

- Sheridan Libraries

- Find This link opens in a new window

- Evaluate This link opens in a new window

Get Organized

- Lit Review Prep Use this template to help you evaluate your sources, create article summaries for an annotated bibliography, and a synthesis matrix for your lit review outline.

Synthesize your Information

Synthesize: combine separate elements to form a whole.

Synthesis Matrix

A synthesis matrix helps you record the main points of each source and document how sources relate to each other.

After summarizing and evaluating your sources, arrange them in a matrix or use a citation manager to help you see how they relate to each other and apply to each of your themes or variables.

By arranging your sources by theme or variable, you can see how your sources relate to each other, and can start thinking about how you weave them together to create a narrative.

- Step-by-Step Approach

- Example Matrix from NSCU

- Matrix Template

- << Previous: Summarize

- Next: Integrate >>

- Last Updated: Sep 26, 2023 10:25 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.jhu.edu/lit-review

How to Synthesize Written Information from Multiple Sources

Shona McCombes

Content Manager

B.A., English Literature, University of Glasgow

Shona McCombes is the content manager at Scribbr, Netherlands.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

When you write a literature review or essay, you have to go beyond just summarizing the articles you’ve read – you need to synthesize the literature to show how it all fits together (and how your own research fits in).

Synthesizing simply means combining. Instead of summarizing the main points of each source in turn, you put together the ideas and findings of multiple sources in order to make an overall point.

At the most basic level, this involves looking for similarities and differences between your sources. Your synthesis should show the reader where the sources overlap and where they diverge.

Unsynthesized Example

Franz (2008) studied undergraduate online students. He looked at 17 females and 18 males and found that none of them liked APA. According to Franz, the evidence suggested that all students are reluctant to learn citations style. Perez (2010) also studies undergraduate students. She looked at 42 females and 50 males and found that males were significantly more inclined to use citation software ( p < .05). Findings suggest that females might graduate sooner. Goldstein (2012) looked at British undergraduates. Among a sample of 50, all females, all confident in their abilities to cite and were eager to write their dissertations.

Synthesized Example

Studies of undergraduate students reveal conflicting conclusions regarding relationships between advanced scholarly study and citation efficacy. Although Franz (2008) found that no participants enjoyed learning citation style, Goldstein (2012) determined in a larger study that all participants watched felt comfortable citing sources, suggesting that variables among participant and control group populations must be examined more closely. Although Perez (2010) expanded on Franz’s original study with a larger, more diverse sample…

Step 1: Organize your sources

After collecting the relevant literature, you’ve got a lot of information to work through, and no clear idea of how it all fits together.

Before you can start writing, you need to organize your notes in a way that allows you to see the relationships between sources.

One way to begin synthesizing the literature is to put your notes into a table. Depending on your topic and the type of literature you’re dealing with, there are a couple of different ways you can organize this.

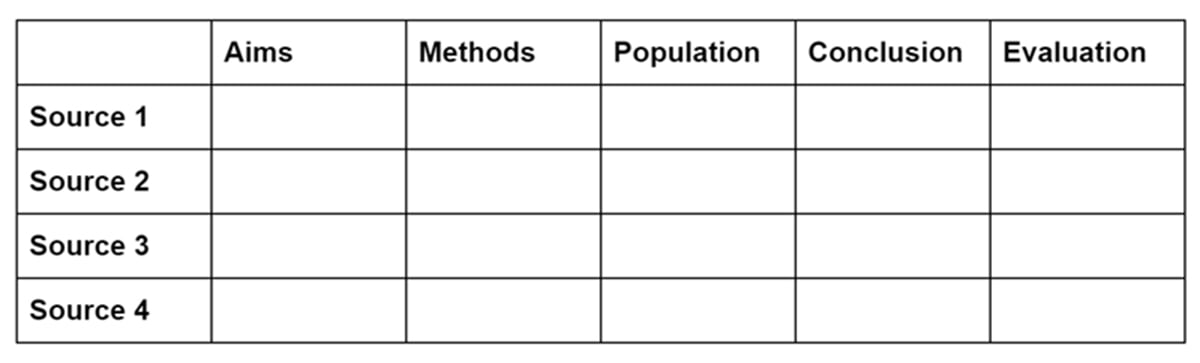

Summary table

A summary table collates the key points of each source under consistent headings. This is a good approach if your sources tend to have a similar structure – for instance, if they’re all empirical papers.

Each row in the table lists one source, and each column identifies a specific part of the source. You can decide which headings to include based on what’s most relevant to the literature you’re dealing with.

For example, you might include columns for things like aims, methods, variables, population, sample size, and conclusion.

For each study, you briefly summarize each of these aspects. You can also include columns for your own evaluation and analysis.

The summary table gives you a quick overview of the key points of each source. This allows you to group sources by relevant similarities, as well as noticing important differences or contradictions in their findings.

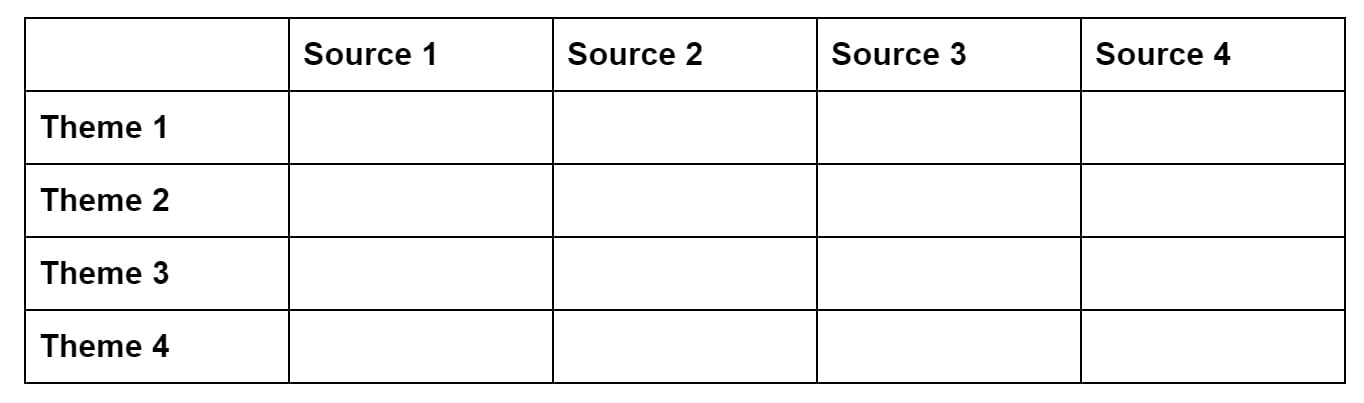

Synthesis matrix

A synthesis matrix is useful when your sources are more varied in their purpose and structure – for example, when you’re dealing with books and essays making various different arguments about a topic.

Each column in the table lists one source. Each row is labeled with a specific concept, topic or theme that recurs across all or most of the sources.

Then, for each source, you summarize the main points or arguments related to the theme.

The purposes of the table is to identify the common points that connect the sources, as well as identifying points where they diverge or disagree.

Step 2: Outline your structure

Now you should have a clear overview of the main connections and differences between the sources you’ve read. Next, you need to decide how you’ll group them together and the order in which you’ll discuss them.

For shorter papers, your outline can just identify the focus of each paragraph; for longer papers, you might want to divide it into sections with headings.

There are a few different approaches you can take to help you structure your synthesis.

If your sources cover a broad time period, and you found patterns in how researchers approached the topic over time, you can organize your discussion chronologically .

That doesn’t mean you just summarize each paper in chronological order; instead, you should group articles into time periods and identify what they have in common, as well as signalling important turning points or developments in the literature.

If the literature covers various different topics, you can organize it thematically .

That means that each paragraph or section focuses on a specific theme and explains how that theme is approached in the literature.

Source Used with Permission: The Chicago School

If you’re drawing on literature from various different fields or they use a wide variety of research methods, you can organize your sources methodologically .

That means grouping together studies based on the type of research they did and discussing the findings that emerged from each method.

If your topic involves a debate between different schools of thought, you can organize it theoretically .

That means comparing the different theories that have been developed and grouping together papers based on the position or perspective they take on the topic, as well as evaluating which arguments are most convincing.

Step 3: Write paragraphs with topic sentences

What sets a synthesis apart from a summary is that it combines various sources. The easiest way to think about this is that each paragraph should discuss a few different sources, and you should be able to condense the overall point of the paragraph into one sentence.

This is called a topic sentence , and it usually appears at the start of the paragraph. The topic sentence signals what the whole paragraph is about; every sentence in the paragraph should be clearly related to it.

A topic sentence can be a simple summary of the paragraph’s content:

“Early research on [x] focused heavily on [y].”

For an effective synthesis, you can use topic sentences to link back to the previous paragraph, highlighting a point of debate or critique:

“Several scholars have pointed out the flaws in this approach.” “While recent research has attempted to address the problem, many of these studies have methodological flaws that limit their validity.”

By using topic sentences, you can ensure that your paragraphs are coherent and clearly show the connections between the articles you are discussing.

As you write your paragraphs, avoid quoting directly from sources: use your own words to explain the commonalities and differences that you found in the literature.

Don’t try to cover every single point from every single source – the key to synthesizing is to extract the most important and relevant information and combine it to give your reader an overall picture of the state of knowledge on your topic.

Step 4: Revise, edit and proofread

Like any other piece of academic writing, synthesizing literature doesn’t happen all in one go – it involves redrafting, revising, editing and proofreading your work.

Checklist for Synthesis

- Do I introduce the paragraph with a clear, focused topic sentence?

- Do I discuss more than one source in the paragraph?

- Do I mention only the most relevant findings, rather than describing every part of the studies?

- Do I discuss the similarities or differences between the sources, rather than summarizing each source in turn?

- Do I put the findings or arguments of the sources in my own words?

- Is the paragraph organized around a single idea?

- Is the paragraph directly relevant to my research question or topic?

- Is there a logical transition from this paragraph to the next one?

Further Information

How to Synthesise: a Step-by-Step Approach

Help…I”ve Been Asked to Synthesize!

Learn how to Synthesise (combine information from sources)

How to write a Psychology Essay

Literature Reviews

- 5. Synthesize your findings

- Getting started

- Types of reviews

- 1. Define your research question

- 2. Plan your search

- 3. Search the literature

- 4. Organize your results

How to synthesize

Approaches to synthesis.

- 6. Write the review

- Artificial intelligence (AI) tools

- Thompson Writing Studio This link opens in a new window

- Need to write a systematic review? This link opens in a new window

Contact a Librarian

Ask a Librarian

In the synthesis step of a literature review, researchers analyze and integrate information from selected sources to identify patterns and themes. This involves critically evaluating findings, recognizing commonalities, and constructing a cohesive narrative that contributes to the understanding of the research topic.

Here are some examples of how to approach synthesizing the literature:

💡 By themes or concepts

🕘 Historically or chronologically

📊 By methodology

These organizational approaches can also be used when writing your review. It can be beneficial to begin organizing your references by these approaches in your citation manager by using folders, groups, or collections.

Create a synthesis matrix

A synthesis matrix allows you to visually organize your literature.

Topic: ______________________________________________

Topic: Chemical exposure to workers in nail salons

- << Previous: 4. Organize your results

- Next: 6. Write the review >>

- Last Updated: May 8, 2024 8:12 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.duke.edu/lit-reviews

Services for...

- Faculty & Instructors

- Graduate Students

- Undergraduate Students

- International Students

- Patrons with Disabilities

- Harmful Language Statement

- Re-use & Attribution / Privacy

- Support the Libraries

Literature Review Basics

- What is a Literature Review?

- Synthesizing Research

- Using Research & Synthesis Tables

- Additional Resources

Synthesis: What is it?

First, let's be perfectly clear about what synthesizing your research isn't :

- - It isn't just summarizing the material you read

- - It isn't generating a collection of annotations or comments (like an annotated bibliography)

- - It isn't compiling a report on every single thing ever written in relation to your topic

When you synthesize your research, your job is to help your reader understand the current state of the conversation on your topic, relative to your research question. That may include doing the following:

- - Selecting and using representative work on the topic

- - Identifying and discussing trends in published data or results

- - Identifying and explaining the impact of common features (study populations, interventions, etc.) that appear frequently in the literature

- - Explaining controversies, disputes, or central issues in the literature that are relevant to your research question

- - Identifying gaps in the literature, where more research is needed

- - Establishing the discussion to which your own research contributes and demonstrating the value of your contribution

Essentially, you're telling your reader where they are (and where you are) in the scholarly conversation about your project.

Synthesis: How do I do it?

Synthesis, step by step.

This is what you need to do before you write your review.

- Identify and clearly describe your research question (you may find the Formulating PICOT Questions table at the Additional Resources tab helpful).

- Collect sources relevant to your research question.

- Organize and describe the sources you've found -- your job is to identify what types of sources you've collected (reviews, clinical trials, etc.), identify their purpose (what are they measuring, testing, or trying to discover?), determine the level of evidence they represent (see the Levels of Evidence table at the Additional Resources tab ), and briefly explain their major findings . Use a Research Table to document this step.

- Study the information you've put in your Research Table and examine your collected sources, looking for similarities and differences . Pay particular attention to populations , methods (especially relative to levels of evidence), and findings .

- Analyze what you learn in (4) using a tool like a Synthesis Table. Your goal is to identify relevant themes, trends, gaps, and issues in the research. Your literature review will collect the results of this analysis and explain them in relation to your research question.

Analysis tips

- - Sometimes, what you don't find in the literature is as important as what you do find -- look for questions that the existing research hasn't answered yet.

- - If any of the sources you've collected refer to or respond to each other, keep an eye on how they're related -- it may provide a clue as to whether or not study results have been successfully replicated.

- - Sorting your collected sources by level of evidence can provide valuable insight into how a particular topic has been covered, and it may help you to identify gaps worth addressing in your own work.

- << Previous: What is a Literature Review?

- Next: Using Research & Synthesis Tables >>

- Last Updated: Sep 26, 2023 12:06 PM

- URL: https://usi.libguides.com/literature-review-basics

Methodological Approaches to Literature Review

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 09 May 2023

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Dennis Thomas 2 ,

- Elida Zairina 3 &

- Johnson George 4

512 Accesses

1 Citations

The literature review can serve various functions in the contexts of education and research. It aids in identifying knowledge gaps, informing research methodology, and developing a theoretical framework during the planning stages of a research study or project, as well as reporting of review findings in the context of the existing literature. This chapter discusses the methodological approaches to conducting a literature review and offers an overview of different types of reviews. There are various types of reviews, including narrative reviews, scoping reviews, and systematic reviews with reporting strategies such as meta-analysis and meta-synthesis. Review authors should consider the scope of the literature review when selecting a type and method. Being focused is essential for a successful review; however, this must be balanced against the relevance of the review to a broad audience.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Akobeng AK. Principles of evidence based medicine. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90(8):837–40.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Alharbi A, Stevenson M. Refining Boolean queries to identify relevant studies for systematic review updates. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27(11):1658–66.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Article Google Scholar

Aromataris E MZE. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. 2020.

Google Scholar

Aromataris E, Pearson A. The systematic review: an overview. Am J Nurs. 2014;114(3):53–8.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Aromataris E, Riitano D. Constructing a search strategy and searching for evidence. A guide to the literature search for a systematic review. Am J Nurs. 2014;114(5):49–56.

Babineau J. Product review: covidence (systematic review software). J Canad Health Libr Assoc Canada. 2014;35(2):68–71.

Baker JD. The purpose, process, and methods of writing a literature review. AORN J. 2016;103(3):265–9.

Bastian H, Glasziou P, Chalmers I. Seventy-five trials and eleven systematic reviews a day: how will we ever keep up? PLoS Med. 2010;7(9):e1000326.

Bramer WM, Rethlefsen ML, Kleijnen J, Franco OH. Optimal database combinations for literature searches in systematic reviews: a prospective exploratory study. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):1–12.

Brown D. A review of the PubMed PICO tool: using evidence-based practice in health education. Health Promot Pract. 2020;21(4):496–8.

Cargo M, Harris J, Pantoja T, et al. Cochrane qualitative and implementation methods group guidance series – paper 4: methods for assessing evidence on intervention implementation. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;97:59–69.

Cook DJ, Mulrow CD, Haynes RB. Systematic reviews: synthesis of best evidence for clinical decisions. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(5):376–80.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Counsell C. Formulating questions and locating primary studies for inclusion in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(5):380–7.

Cummings SR, Browner WS, Hulley SB. Conceiving the research question and developing the study plan. In: Cummings SR, Browner WS, Hulley SB, editors. Designing Clinical Research: An Epidemiological Approach. 4th ed. Philadelphia (PA): P Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. p. 14–22.

Eriksen MB, Frandsen TF. The impact of patient, intervention, comparison, outcome (PICO) as a search strategy tool on literature search quality: a systematic review. JMLA. 2018;106(4):420.

Ferrari R. Writing narrative style literature reviews. Medical Writing. 2015;24(4):230–5.

Flemming K, Booth A, Hannes K, Cargo M, Noyes J. Cochrane qualitative and implementation methods group guidance series – paper 6: reporting guidelines for qualitative, implementation, and process evaluation evidence syntheses. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;97:79–85.

Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf Libr J. 2009;26(2):91–108.

Green BN, Johnson CD, Adams A. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade. J Chiropr Med. 2006;5(3):101–17.

Gregory AT, Denniss AR. An introduction to writing narrative and systematic reviews; tasks, tips and traps for aspiring authors. Heart Lung Circ. 2018;27(7):893–8.

Harden A, Thomas J, Cargo M, et al. Cochrane qualitative and implementation methods group guidance series – paper 5: methods for integrating qualitative and implementation evidence within intervention effectiveness reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;97:70–8.

Harris JL, Booth A, Cargo M, et al. Cochrane qualitative and implementation methods group guidance series – paper 2: methods for question formulation, searching, and protocol development for qualitative evidence synthesis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;97:39–48.

Higgins J, Thomas J. In: Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.3, updated February 2022). Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.: Cochrane; 2022.

International prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO). Available from https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/ .

Khan KS, Kunz R, Kleijnen J, Antes G. Five steps to conducting a systematic review. J R Soc Med. 2003;96(3):118–21.

Landhuis E. Scientific literature: information overload. Nature. 2016;535(7612):457–8.

Lockwood C, Porritt K, Munn Z, Rittenmeyer L, Salmond S, Bjerrum M, Loveday H, Carrier J, Stannard D. Chapter 2: Systematic reviews of qualitative evidence. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI; 2020. Available from https://synthesismanual.jbi.global . https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-03 .

Chapter Google Scholar

Lorenzetti DL, Topfer L-A, Dennett L, Clement F. Value of databases other than medline for rapid health technology assessments. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2014;30(2):173–8.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, the PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for (SR) and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;6:264–9.

Mulrow CD. Systematic reviews: rationale for systematic reviews. BMJ. 1994;309(6954):597–9.

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143.

Munthe-Kaas HM, Glenton C, Booth A, Noyes J, Lewin S. Systematic mapping of existing tools to appraise methodological strengths and limitations of qualitative research: first stage in the development of the CAMELOT tool. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19(1):1–13.

Murphy CM. Writing an effective review article. J Med Toxicol. 2012;8(2):89–90.

NHMRC. Guidelines for guidelines: assessing risk of bias. Available at https://nhmrc.gov.au/guidelinesforguidelines/develop/assessing-risk-bias . Last published 29 August 2019. Accessed 29 Aug 2022.

Noyes J, Booth A, Cargo M, et al. Cochrane qualitative and implementation methods group guidance series – paper 1: introduction. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018b;97:35–8.

Noyes J, Booth A, Flemming K, et al. Cochrane qualitative and implementation methods group guidance series – paper 3: methods for assessing methodological limitations, data extraction and synthesis, and confidence in synthesized qualitative findings. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018a;97:49–58.

Noyes J, Booth A, Moore G, Flemming K, Tunçalp Ö, Shakibazadeh E. Synthesising quantitative and qualitative evidence to inform guidelines on complex interventions: clarifying the purposes, designs and outlining some methods. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(Suppl 1):e000893.

Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Healthcare. 2015;13(3):141–6.

Polanin JR, Pigott TD, Espelage DL, Grotpeter JK. Best practice guidelines for abstract screening large-evidence systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Res Synth Methods. 2019;10(3):330–42.

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7(1):1–7.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. Brit Med J. 2017;358

Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. Br Med J. 2016;355

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–12.

Tawfik GM, Dila KAS, Mohamed MYF, et al. A step by step guide for conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis with simulation data. Trop Med Health. 2019;47(1):1–9.

The Critical Appraisal Program. Critical appraisal skills program. Available at https://casp-uk.net/ . 2022. Accessed 29 Aug 2022.

The University of Melbourne. Writing a literature review in Research Techniques 2022. Available at https://students.unimelb.edu.au/academic-skills/explore-our-resources/research-techniques/reviewing-the-literature . Accessed 29 Aug 2022.

The Writing Center University of Winconsin-Madison. Learn how to write a literature review in The Writer’s Handbook – Academic Professional Writing. 2022. Available at https://writing.wisc.edu/handbook/assignments/reviewofliterature/ . Accessed 29 Aug 2022.

Thompson SG, Sharp SJ. Explaining heterogeneity in meta-analysis: a comparison of methods. Stat Med. 1999;18(20):2693–708.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16(1):15.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Yoneoka D, Henmi M. Clinical heterogeneity in random-effect meta-analysis: between-study boundary estimate problem. Stat Med. 2019;38(21):4131–45.

Yuan Y, Hunt RH. Systematic reviews: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(5):1086–92.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre of Excellence in Treatable Traits, College of Health, Medicine and Wellbeing, University of Newcastle, Hunter Medical Research Institute Asthma and Breathing Programme, Newcastle, NSW, Australia

Dennis Thomas

Department of Pharmacy Practice, Faculty of Pharmacy, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia

Elida Zairina

Centre for Medicine Use and Safety, Monash Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Monash University, Parkville, VIC, Australia

Johnson George

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Johnson George .

Section Editor information

College of Pharmacy, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar

Derek Charles Stewart

Department of Pharmacy, University of Huddersfield, Huddersfield, United Kingdom

Zaheer-Ud-Din Babar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Thomas, D., Zairina, E., George, J. (2023). Methodological Approaches to Literature Review. In: Encyclopedia of Evidence in Pharmaceutical Public Health and Health Services Research in Pharmacy. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50247-8_57-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50247-8_57-1

Received : 22 February 2023

Accepted : 22 February 2023

Published : 09 May 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-50247-8

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-50247-8

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Biomedicine and Life Sciences Reference Module Biomedical and Life Sciences

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 11 August 2009

Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review

- Elaine Barnett-Page 1 &

- James Thomas 1

BMC Medical Research Methodology volume 9 , Article number: 59 ( 2009 ) Cite this article

196k Accesses

1065 Citations

40 Altmetric

Metrics details

In recent years, a growing number of methods for synthesising qualitative research have emerged, particularly in relation to health-related research. There is a need for both researchers and commissioners to be able to distinguish between these methods and to select which method is the most appropriate to their situation.

A number of methodological and conceptual links between these methods were identified and explored, while contrasting epistemological positions explained differences in approaches to issues such as quality assessment and extent of iteration. Methods broadly fall into 'realist' or 'idealist' epistemologies, which partly accounts for these differences.

Methods for qualitative synthesis vary across a range of dimensions. Commissioners of qualitative syntheses might wish to consider the kind of product they want and select their method – or type of method – accordingly.

Peer Review reports

The range of different methods for synthesising qualitative research has been growing over recent years [ 1 , 2 ], alongside an increasing interest in qualitative synthesis to inform health-related policy and practice [ 3 ]. While the terms 'meta-analysis' (a statistical method to combine the results of primary studies), or sometimes 'narrative synthesis', are frequently used to describe how quantitative research is synthesised, far more terms are used to describe the synthesis of qualitative research. This profusion of terms can mask some of the basic similarities in approach that the different methods share, and also lead to some confusion regarding which method is most appropriate in a given situation. This paper does not argue that the various nomenclatures are unnecessary, but rather seeks to draw together and review the full range of methods of synthesis available to assist future reviewers in selecting a method that is fit for their purpose. It also represents an attempt to guide the reader through some of the varied terminology to spring up around qualitative synthesis. Other helpful reviews of synthesis methods have been undertaken in recent years with slightly different foci to this paper. Two recent studies have focused on describing and critiquing methods for the integration of qualitative research with quantitative [ 4 , 5 ] rather than exclusively examining the detail and rationale of methods for the synthesis of qualitative research. Two other significant pieces of work give practical advice for conducting the synthesis of qualitative research, but do not discuss the full range of methods available [ 6 , 7 ]. We begin our Discussion by outlining each method of synthesis in turn, before comparing and contrasting characteristics of these different methods across a range of dimensions. Readers who are more familiar with the synthesis methods described here may prefer to turn straight to the 'dimensions of difference' analysis in the second part of the Discussion.

Overview of synthesis methods

Meta-ethnography.

In their seminal work of 1988, Noblit and Hare proposed meta-ethnography as an alternative to meta-analysis [ 8 ]. They cited Strike and Posner's [ 9 ] definition of synthesis as an activity in which separate parts are brought together to form a 'whole'; this construction of the whole is essentially characterised by some degree of innovation, so that the result is greater than the sum of its parts. They also borrowed from Turner's theory of social explanation [ 10 ], a key tenet of which was building 'comparative understanding' [[ 8 ], p22] rather than aggregating data.

To Noblit and Hare, synthesis provided an answer to the question of 'how to "put together" written interpretive accounts' [[ 8 ], p7], where mere integration would not be appropriate. Noblit and Hare's early work synthesised research from the field of education.

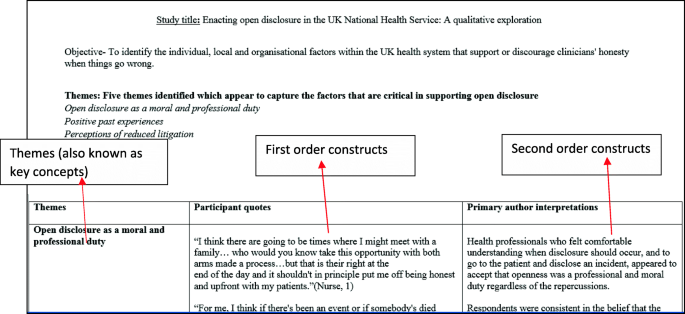

Three different methods of synthesis are used in meta-ethnography. One involves the 'translation' of concepts from individual studies into one another, thereby evolving overarching concepts or metaphors. Noblit and Hare called this process reciprocal translational analysis (RTA). Refutational synthesis involves exploring and explaining contradictions between individual studies. Lines-of-argument (LOA) synthesis involves building up a picture of the whole (i.e. culture, organisation etc) from studies of its parts. The authors conceptualised this latter approach as a type of grounded theorising.

Britten et al [ 11 ] and Campbell et al [ 12 ] have both conducted evaluations of meta-ethnography and claim to have succeeded, by using this method, in producing theories with greater explanatory power than could be achieved in a narrative literature review. While both these evaluations used small numbers of studies, more recently Pound et al [ 13 ] conducted both an RTA and an LOA synthesis using a much larger number of studies (37) on resisting medicines. These studies demonstrate that meta-ethnography has evolved since Noblit and Hare first introduced it. Campbell et al claim to have applied the method successfully to non-ethnographical studies. Based on their reading of Schutz [ 14 ], Britten et al have developed both second and third order constructs in their synthesis (Noblit and Hare briefly allude to the possibility of a 'second level of synthesis' [[ 8 ], p28] but do not demonstrate or further develop the idea).

In a more recent development, Sandelowski & Barroso [ 15 ] write of adapting RTA by using it to ' integrate findings interpretively, as opposed to comparing them interpretively' (p204). The former would involve looking to see whether the same concept, theory etc exists in different studies; the latter would involve the construction of a bigger picture or theory (i.e. LOA synthesis). They also talk about comparing or integrating imported concepts (e.g. from other disciplines) as well as those evolved 'in vivo'.

Grounded theory

Kearney [ 16 ], Eaves [ 17 ] and Finfgeld [ 18 ] have all adapted grounded theory to formulate a method of synthesis. Key methods and assumptions of grounded theory, as originally formulated and subsequently refined by Glaser and Strauss [ 19 ] and Strauss and Corbin [ 20 , 21 ], include: simultaneous phases of data collection and analysis; an inductive approach to analysis, allowing the theory to emerge from the data; the use of the constant comparison method; the use of theoretical sampling to reach theoretical saturation; and the generation of new theory. Eaves cited grounded theorists Charmaz [ 22 ] and Chesler [ 23 ], as well as Strauss and Corbin [ 20 ], as informing her approach to synthesis.

Glaser and Strauss [ 19 ] foresaw a time when a substantive body of grounded research should be pushed towards a higher, more abstract level. As a piece of methodological work, Eaves undertook her own synthesis of the synthesis methods used by these authors to produce her own clear and explicit guide to synthesis in grounded formal theory. Kearney stated that 'grounded formal theory', as she termed this method of synthesis, 'is suited to study of phenomena involving processes of contextualized understanding and action' [[ 24 ], p180] and, as such, is particularly applicable to nurses' research interests.

As Kearney suggested, the examples examined here were largely dominated by research in nursing. Eaves synthesised studies on care-giving in rural African-American families for elderly stroke survivors; Finfgeld on courage among individuals with long-term health problems; Kearney on women's experiences of domestic violence.

Kearney explicitly chose 'grounded formal theory' because it matches 'like' with 'like': that is, it applies the same methods that have been used to generate the original grounded theories included in the synthesis – produced by constant comparison and theoretical sampling – to generate a higher-level grounded theory. The wish to match 'like' with 'like' is also implicit in Eaves' paper. This distinguishes grounded formal theory from more recent applications of meta-ethnography, which have sought to include qualitative research using diverse methodological approaches [ 12 ].

- Thematic Synthesis

Thomas and Harden [ 25 ] have developed an approach to synthesis which they term 'thematic synthesis'. This combines and adapts approaches from both meta-ethnography and grounded theory. The method was developed out of a need to conduct reviews that addressed questions relating to intervention need, appropriateness and acceptability – as well as those relating to effectiveness – without compromising on key principles developed in systematic reviews. They applied thematic synthesis in a review of the barriers to, and facilitators of, healthy eating amongst children.

Free codes of findings are organised into 'descriptive' themes, which are then further interpreted to yield 'analytical' themes. This approach shares characteristics with later adaptations of meta-ethnography, in that the analytical themes are comparable to 'third order interpretations' and that the development of descriptive and analytical themes using coding invoke reciprocal 'translation'. It also shares much with grounded theory, in that the approach is inductive and themes are developed using a 'constant comparison' method. A novel aspect of their approach is the use of computer software to code the results of included studies line-by-line, thus borrowing another technique from methods usually used to analyse primary research.

Textual Narrative Synthesis

Textual narrative synthesis is an approach which arranges studies into more homogenous groups. Lucas et al [ 26 ] comment that it has proved useful in synthesising evidence of different types (qualitative, quantitative, economic etc). Typically, study characteristics, context, quality and findings are reported on according to a standard format and similarities and differences are compared across studies. Structured summaries may also be developed, elaborating on and putting into context the extracted data [ 27 ].

Lucas et al [ 26 ] compared thematic synthesis with textual narrative synthesis. They found that 'thematic synthesis holds most potential for hypothesis generation' whereas textual narrative synthesis is more likely to make transparent heterogeneity between studies (as does meta-ethnography, with refutational synthesis) and issues of quality appraisal. This is possibly because textual narrative synthesis makes clearer the context and characteristics of each study, while the thematic approach organises data according to themes. However, Lucas et al found that textual narrative synthesis is 'less good at identifying commonality' (p2); the authors do not make explicit why this should be, although it may be that organising according to themes, as the thematic approach does, is comparatively more successful in revealing commonality.

Paterson et al [ 28 ] have evolved a multi-faceted approach to synthesis, which they call 'meta-study'. The sociologist Zhao [ 29 ], drawing on Ritzer's work [ 30 ], outlined three components of analysis, which they proposed should be undertaken prior to synthesis. These are meta-data-analysis (the analysis of findings), meta-method (the analysis of methods) and meta-theory (the analysis of theory). Collectively, these three elements of analysis, culminating in synthesis, make up the practice of 'meta-study'. Paterson et al pointed out that the different components of analysis may be conducted concurrently.

Paterson et al argued that primary research is a construction; secondary research is therefore a construction of a construction. There is need for an approach that recognises this, and that also recognises research to be a product of its social, historical and ideological context. Such an approach would be useful in accounting for differences in research findings. For Paterson et al, there is no such thing as 'absolute truth'.

Meta-study was developed to study the experiences of adults living with a chronic illness. Meta-data-analysis was conceived of by Paterson et al in similar terms to Noblit and Hare's meta-ethnography (see above), in that it is essentially interpretive and seeks to reveal similarities and discrepancies among accounts of a particular phenomenon. Meta-method involves the examination of the methodologies of the individual studies under review. Part of the process of meta-method is to consider different aspects of methodology such as sampling, data collection, research design etc, similar to procedures others have called 'critical appraisal' (CASP [ 31 ]). However, Paterson et al take their critique to a deeper level by establishing the underlying assumptions of the methodologies used and the relationship between research outcomes and methods used. Meta-theory involves scrutiny of the philosophical and theoretical assumptions of the included research papers; this includes looking at the wider context in which new theory is generated. Paterson et al described meta-synthesis as a process which creates a new interpretation which accounts for the results of all three elements of analysis. The process of synthesis is iterative and reflexive and the authors were unwilling to oversimplify the process by 'codifying' procedures for bringing all three components of analysis together.

Meta-narrative

Greenhalgh et al [ 32 ]'s meta-narrative approach to synthesis arose out of the need to synthesise evidence to inform complex policy-making questions and was assisted by the formation of a multi-disciplinary team. Their approach to review was informed by Thomas Kuhn's The Structure of Scientific Revolutions [ 33 ], in which he proposed that knowledge is produced within particular paradigms which have their own assumptions about theory, about what is a legitimate object of study, about what are legitimate research questions and about what constitutes a finding. Paradigms also tend to develop through time according to a particular set of stages, central to which is the stage of 'normal science', in which the particular standards of the paradigm are largely unchallenged and seen to be self-evident. As Greenhalgh et al pointed out, Kuhn saw paradigms as largely incommensurable: 'that is, an empirical discovery made using one set of concepts, theories, methods and instruments cannot be satisfactorily explained through a different paradigmatic lens' [[ 32 ], p419].

Greenhalgh et al synthesised research from a wide range of disciplines; their research question related to the diffusion of innovations in health service delivery and organisation. They thus identified a need to synthesise findings from research which contains many different theories arising from many different disciplines and study designs.

Based on Kuhn's work, Greenhalgh et al proposed that, across different paradigms, there were multiple – and potentially mutually contradictory – ways of understanding the concept at the heart of their review, namely the diffusion of innovation. Bearing this in mind, the reviewers deliberately chose to select key papers from a number of different research 'paradigms' or 'traditions', both within and beyond healthcare, guided by their multidisciplinary research team. They took as their unit of analysis the 'unfolding "storyline" of a research tradition over time' [[ 32 ], p417) and sought to understand diffusion of innovation as it was conceptualised in each of these traditions. Key features of each tradition were mapped: historical roots, scope, theoretical basis; research questions asked and methods/instruments used; main empirical findings; historical development of the body of knowledge (how have earlier findings led to later findings); and strengths and limitations of the tradition. The results of this exercise led to maps of 13 'meta-narratives' in total, from which seven key dimensions, or themes, were identified and distilled for the synthesis phase of the review.

Critical Interpretive Synthesis

Dixon-Woods et al [ 34 ] developed their own approach to synthesising multi-disciplinary and multi-method evidence, termed 'critical interpretive synthesis', while researching access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. Critical interpretive synthesis is an adaptation of meta-ethnography, as well as borrowing techniques from grounded theory. The authors stated that they needed to adapt traditional meta-ethnographic methods for synthesis, since these had never been applied to quantitative as well as qualitative data, nor had they been applied to a substantial body of data (in this case, 119 papers).

Dixon-Woods et al presented critical interpretive synthesis as an approach to the whole process of review, rather than to just the synthesis component. It involves an iterative approach to refining the research question and searching and selecting from the literature (using theoretical sampling) and defining and applying codes and categories. It also has a particular approach to appraising quality, using relevance – i.e. likely contribution to theory development – rather than methodological characteristics as a means of determining the 'quality' of individual papers [ 35 ]. The authors also stress, as a defining characteristic, critical interpretive synthesis's critical approach to the literature in terms of deconstructing research traditions or theoretical assumptions as a means of contextualising findings.

Dixon-Woods et al rejected reciprocal translational analysis (RTA) as this produced 'only a summary in terms that have already been used in the literature' [[ 34 ], p5], which was seen as less helpful when dealing with a large and diverse body of literature. Instead, Dixon-Woods et al adopted a lines-of-argument (LOA) synthesis, in which – rejecting the difference between first, second and third order constructs – they instead developed 'synthetic constructs' which were then linked with constructs arising directly from the literature.

The influence of grounded theory can be seen in particular in critical interpretive synthesis's inductive approach to formulating the review question and to developing categories and concepts, rejecting a 'stage' approach to systematic reviewing, and in selecting papers using theoretical sampling. Dixon-Woods et al also claim that critical interpretive synthesis is distinct in its 'explicit orientation towards theory generation' [[ 34 ], p9].

Ecological Triangulation

Jim Banning is the author of 'ecological triangulation' or 'ecological sentence synthesis', applying this method to the evidence for what works for youth with disabilities. He borrows from Webb et al [ 36 ] and Denzin [ 37 ] the concept of triangulation, in which phenomena are studied from a variety of vantage points. His rationale is that building an 'evidence base' of effectiveness requires the synthesis of cumulative, multi-faceted evidence in order to find out 'what intervention works for what kind of outcomes for what kind of persons under what kind of conditions' [[ 38 ], p1].

Ecological triangulation unpicks the mutually interdependent relationships between behaviour, persons and environments. The method requires that, for data extraction and synthesis, 'ecological sentences' are formulated following the pattern: 'With this intervention, these outcomes occur with these population foci and within these grades (ages), with these genders ... and these ethnicities in these settings' [[ 39 ], p1].

Framework Synthesis

Brunton et al [ 40 ] and Oliver et al [ 41 ] have applied a 'framework synthesis' approach in their reviews. Framework synthesis is based on framework analysis, which was outlined by Pope, Ziebland and Mays [ 42 ], and draws upon the work of Ritchie and Spencer [ 43 ] and Miles and Huberman [ 44 ]. Its rationale is that qualitative research produces large amounts of textual data in the form of transcripts, observational fieldnotes etc. The sheer wealth of information poses a challenge for rigorous analysis. Framework synthesis offers a highly structured approach to organising and analysing data (e.g. indexing using numerical codes, rearranging data into charts etc).

Brunton et al applied the approach to a review of children's, young people's and parents' views of walking and cycling; Oliver et al to an analysis of public involvement in health services research. Framework synthesis is distinct from the other methods outlined here in that it utilises an a priori 'framework' – informed by background material and team discussions – to extract and synthesise findings. As such, it is largely a deductive approach although, in addition to topics identified by the framework, new topics may be developed and incorporated as they emerge from the data. The synthetic product can be expressed in the form of a chart for each key dimension identified, which may be used to map the nature and range of the concept under study and find associations between themes and exceptions to these [ 40 ].

'Fledgling' approaches

There are three other approaches to synthesis which have not yet been widely used. One is an approach using content analysis [ 45 , 46 ] in which text is condensed into fewer content-related categories. Another is 'meta-interpretation' [ 47 ], featuring the following: an ideographic rather than pre-determined approach to the development of exclusion criteria; a focus on meaning in context; interpretations as raw data for synthesis (although this feature doesn't distinguish it from other synthesis methods); an iterative approach to the theoretical sampling of studies for synthesis; and a transparent audit trail demonstrating the trustworthiness of the synthesis.

In addition to the synthesis methods discussed above, Sandelowski and Barroso propose a method they call 'qualitative metasummary' [ 15 ]. It is mentioned here as a new and original approach to handling a collection of qualitative studies but is qualitatively different to the other methods described here since it is aggregative; that is, findings are accumulated and summarised rather than 'transformed'. Metasummary is a way of producing a 'map' of the contents of qualitative studies and – according to Sandelowski and Barroso – 'reflect [s] a quantitative logic' [[ 15 ], p151]. The frequency of each finding is determined and the higher the frequency of a particular finding, the greater its validity. The authors even discuss the calculation of 'effect sizes' for qualitative findings. Qualitative metasummaries can be undertaken as an end in themselves or may serve as a basis for a further synthesis.

Dimensions of difference

Having outlined the range of methods identified, we now turn to an examination of how they compare with one another. It is clear that they have come from many different contexts and have different approaches to understanding knowledge, but what do these differences mean in practice? Our framework for this analysis is shown in Additional file 1 : dimensions of difference [ 48 ]. We have examined the epistemology of each of the methods and found that, to some extent, this explains the need for different methods and their various approaches to synthesis.

Epistemology

The first dimension that we will consider is that of the researchers' epistemological assumptions. Spencer et al [ 49 ] outline a range of epistemological positions, which might be organised into a spectrum as follows:

Subjective idealism : there is no shared reality independent of multiple alternative human constructions

Objective idealism : there is a world of collectively shared understandings

Critical realism : knowledge of reality is mediated by our perceptions and beliefs

Scientific realism : it is possible for knowledge to approximate closely an external reality

Naïve realism : reality exists independently of human constructions and can be known directly [ 49 , 45 , 46 ].

Thus, at one end of the spectrum we have a highly constructivist view of knowledge and, at the other, an unproblematized 'direct window onto the world' view.

Nearly all of positions along this spectrum are represented in the range of methodological approaches to synthesis covered in this paper. The originators of meta-narrative synthesis, critical interpretive synthesis and meta-study all articulate what might be termed a 'subjective idealist' approach to knowledge. Paterson et al [ 28 ] state that meta-study shies away from creating 'grand theories' within the health or social sciences and assume that no single objective reality will be found. Primary studies, they argue, are themselves constructions; meta-synthesis, then, 'deals with constructions of constructions' (p7). Greenhalgh et al [ 32 ] also view knowledge as a product of its disciplinary paradigm and use this to explain conflicting findings: again, the authors neither seek, nor expect to find, one final, non-contestable answer to their research question. Critical interpretive synthesis is similar in seeking to place literature within its context, to question its assumptions and to produce a theoretical model of a phenomenon which – because highly interpretive – may not be reproducible by different research teams at alternative points in time [[ 34 ], p11].

Methods used to synthesise grounded theory studies in order to produce a higher level of grounded theory [ 24 ] appear to be informed by 'objective idealism', as does meta-ethnography. Kearney argues for the near-universal applicability of a 'ready-to-wear' theory across contexts and populations. This approach is clearly distinct from one which recognises multiple realities. The emphasis is on examining commonalities amongst, rather than discrepancies between, accounts. This emphasis is similarly apparent in most meta-ethnographies, which are conducted either according to Noblit and Hare's 'reciprocal translational analysis' technique or to their 'lines-of-argument' technique and which seek to provide a 'whole' which has a greater explanatory power. Although Noblit and Hare also propose 'refutational synthesis', in which contradictory findings might be explored, there are few examples of this having been undertaken in practice, and the aim of the method appears to be to explain and explore differences due to context, rather than multiple realities.

Despite an assumption of a reality which is perhaps less contestable than those of meta-narrative synthesis, critical interpretive synthesis and meta-study, both grounded formal theory and meta-ethnography place a great deal of emphasis on the interpretive nature of their methods. This still supposes a degree of constructivism. Although less explicit about how their methods are informed, it seems that both thematic synthesis and framework synthesis – while also involving some interpretation of data – share an even less problematized view of reality and a greater assumption that their synthetic products are reproducible and correspond to a shared reality. This is also implicit in the fact that such products are designed directly to inform policy and practice, a characteristic shared by ecological triangulation. Notably, ecological triangulation, according to Banning, can be either realist or idealist. Banning argues that the interpretation of triangulation can either be one in which multiple viewpoints converge on a point to produce confirming evidence (i.e. one definitive answer to the research question) or an idealist one, in which the complexity of multiple viewpoints is represented. Thus, although ecological triangulation views reality as complex, the approach assumes that it can be approximately knowable (at least when the realist view of ecological triangulation is adopted) and that interventions can and should be modelled according to the products of its syntheses.

While pigeonholing different methods into specific epistemological positions is a problematic process, we do suggest that the contrasting epistemologies of different researchers is one way of explaining why we have – and need – different methods for synthesis.

Variation in terms of the extent of iteration during the review process is another key dimension. All synthesis methods include some iteration but the degree varies. Meta-ethnography, grounded theory and thematic synthesis all include iteration at the synthesis stage; both framework synthesis and critical interpretive synthesis involve iterative literature searching – in the case of critical interpretive synthesis, it is not clear whether iteration occurs during the rest of the review process. Meta-narrative also involves iteration at every stage. Banning does not mention iteration in outlining ecological triangulation and neither do Lucas or Thomas and Harden for thematic narrative synthesis.

It seems that the more idealist the approach, the greater the extent of iteration. This might be because a large degree of iteration does not sit well with a more 'positivist' ideal of procedural objectivity; in particular, the notion that the robustness of the synthetic product depends in part on the reviewers stating up front in a protocol their searching strategies, inclusion/exclusion criteria etc, and being seen not to alter these at a later stage.

Quality assessment

Another dimension along which we can look at different synthesis methods is that of quality assessment. When the approaches to the assessment of the quality of studies retrieved for review are examined, there is again a wide methodological variation. It might be expected that the further towards the 'realism' end of the epistemological spectrum a method of synthesis falls, the greater the emphasis on quality assessment. In fact, this is only partially the case.

Framework synthesis, thematic narrative synthesis and thematic synthesis – methods which might be classified as sharing a 'critical realist' approach – all have highly specified approaches to quality assessment. The review in which framework synthesis was developed applied ten quality criteria: two on quality and reporting of sampling methods, four to the quality of the description of the sample in the study, two to the reliability and validity of the tools used to collect data and one on whether studies used appropriate methods for helping people to express their views. Studies which did not meet a certain number of quality criteria were excluded from contributing to findings. Similarly, in the example review for thematic synthesis, 12 criteria were applied: five related to reporting aims, context, rationale, methods and findings; four relating to reliability and validity; and three relating to the appropriateness of methods for ensuring that findings were rooted in participants' own perspectives. Studies which were deemed to have significant flaws were excluded and sensitivity analyses were used to assess the possible impact of study quality on the review's findings. Thomas and Harden's use of thematic narrative synthesis similarly applied quality criteria and developed criteria additional to those they found in the literature on quality assessment, relating to the extent to which people's views and perspectives had been privileged by researchers. It is worth noting not only that these methods apply quality criteria but that they are explicit about what they are: assessing quality is a key component in the review process for both of these methods. Likewise, Banning – the originator of ecological triangulation – sees quality assessment as important and adapts the Design and Implementation Assessment Device (DIAD) Version 0.3 (a quality assessment tool for quantitative research) for use when appraising qualitative studies [ 50 ]. Again, Banning writes of excluding studies deemed to be of poor quality.

Greenhalgh et al's meta-narrative review [ 32 ] modified a range of existing quality assessment tools to evaluate studies according to validity and robustness of methods; sample size and power; and validity of conclusions. The authors imply, but are not explicit, that this process formed the basis for the exclusion of some studies. Although not quite so clear about quality assessment methods as framework and thematic synthesis, it might be argued that meta-narrative synthesis shows a greater commitment to the concept that research can and should be assessed for quality than either meta-ethnography or grounded formal theory. The originators of meta-ethnography, Noblit and Hare [ 8 ], originally discussed quality in terms of quality of metaphor, while more recent use of this method has used amended versions of CASP (the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme tool, [ 31 ]), yet has only referred to studies being excluded on the basis of lack of relevance or because they weren't 'qualitative' studies [ 8 ]. In grounded theory, quality assessment is only discussed in terms of a 'personal note' being made on the context, quality and usefulness of each study. However, contrary to expectation, meta-narrative synthesis lies at the extreme end of the idealism/realism spectrum – as a subjective idealist approach – while meta-ethnography and grounded theory are classified as objective idealist approaches.

Finally, meta-study and critical interpretive synthesis – two more subjective idealist approaches – look to the content and utility of findings rather than methodology in order to establish quality. While earlier forms of meta-study included only studies which demonstrated 'epistemological soundness', in its most recent form [ 51 ] this method has sought to include all relevant studies, excluding only those deemed not to be 'qualitative' research. Critical interpretive synthesis also conforms to what we might expect of its approach to quality assessment: quality of research is judged as the extent to which it informs theory. The threshold of inclusion is informed by expertise and instinct rather than being articulated a priori.

In terms of quality assessment, it might be important to consider the academic context in which these various methods of synthesis developed. The reason why thematic synthesis, framework synthesis and ecological triangulation have such highly specified approaches to quality assessment may be that each of these was developed for a particular task, i.e. to conduct a multi-method review in which randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were included. The concept of quality assessment in relation to RCTs is much less contested and there is general agreement on criteria against which quality should be judged.

Problematizing the literature

Critical interpretive synthesis, the meta-narrative approach and the meta-theory element of meta-study all share some common ground in that their review and synthesis processes include examining all aspects of the context in which knowledge is produced. In conducting a review on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups, critical interpretive synthesis sought to question 'the ways in which the literature had constructed the problematics of access, the nature of the assumptions on which it drew, and what has influenced its choice of proposed solutions' [[ 34 ], p6]. Although not claiming to have been directly influenced by Greenhalgh et al's meta-narrative approach, Dixon-Woods et al do cite it as sharing similar characteristics in the sense that it critiques the literature it reviews.

Meta-study uses meta-theory to describe and deconstruct the theories that shape a body of research and to assess its quality. One aspect of this process is to examine the historical evolution of each theory and to put it in its socio-political context, which invites direct comparison with meta-narrative synthesis. Greenhalgh et al put a similar emphasis on placing research findings within their social and historical context, often as a means of seeking to explain heterogeneity of findings. In addition, meta-narrative shares with critical interpretive synthesis an iterative approach to searching and selecting from the literature.

Framework synthesis, thematic synthesis, textual narrative synthesis, meta-ethnography and grounded theory do not share the same approach to problematizing the literature as critical interpretive synthesis, meta-study and meta-narrative. In part, this may be explained by the extent to which studies included in the synthesis represented a broad range of approaches or methodologies. This, in turn, may reflect the broadness of the review question and the extent to which the concepts contained within the question are pre-defined within the literature. In the case of both the critical interpretive synthesis and meta-narrative reviews, terminology was elastic and/or the question formed iteratively. Similarly, both reviews placed great emphasis on employing multi-disciplinary research teams. Approaches which do not critique the literature in the same way tend to have more narrowly-focused questions. They also tend to include a more limited range of studies: grounded theory synthesis includes grounded theory studies, meta-ethnography (in its original form, as applied by Noblit and Hare) ethnographies. The thematic synthesis incorporated studies based on only a narrow range of qualitative methodologies (interviews and focus groups) which were informed by a similarly narrow range of epistemological assumptions. It may be that the authors of such syntheses saw no need for including such a critique in their review process.