161 Case Studies: Real Stories Of People Overcoming Struggles of Mental Health

At Tracking Happiness, we’re dedicated to helping others around the world overcome struggles of mental health.

In 2022, we published a survey of 5,521 respondents and found:

- 88% of our respondents experienced mental health issues in the past year.

- 25% of people don’t feel comfortable sharing their struggles with anyone, not even their closest friends.

In order to break the stigma that surrounds mental health struggles, we’re looking to share your stories.

Overcoming struggles

They say that everyone you meet is engaged in a great struggle. No matter how well someone manages to hide it, there’s always something to overcome, a struggle to deal with, an obstacle to climb.

And when someone is engaged in a struggle, that person is looking for others to join him. Because we, as human beings, don’t thrive when we feel alone in facing a struggle.

Let’s throw rocks together

Overcoming your struggles is like defeating an angry giant. You try to throw rocks at it, but how much damage is one little rock gonna do?

Tracking Happiness can become your partner in facing this giant. We are on a mission to share all your stories of overcoming mental health struggles. By doing so, we want to help inspire you to overcome the things that you’re struggling with, while also breaking the stigma of mental health.

Which explains the phrase: “Let’s throw rocks together”.

Let’s throw rocks together, and become better at overcoming our struggles collectively. If you’re interested in becoming a part of this and sharing your story, click this link!

Case studies

July 23, 2024

Surviving The Boston Marathon Bombings While Facing TBI and Medical Gaslighting

“As I literally lived on his couch, with my port-a-potty in his living room, my partner eventually applied for permanent disability status for me. But, even then doctor gaslighted me, told me I was physically able to work, and reported the same to the government. In reality, I was so dizzy with vertigo, this same doctor refused to let me walk to and from our car, by myself, fearing I’d fall and sue!”

Struggled with: CPTSD Traumatic Brain Injury

Helped by: Treatment

July 16, 2024

Somatic Therapy Helped Me Heal From CPTSD After Years of Childhood Abuse

“At 22 years old, I knew that I was dying of alcoholism. I accepted that. The trauma symptoms I experienced were too overwhelming to stop drinking. When I was sober, I would sometimes experience 30 to 40 body memories of being sexually assaulted–again and again in succession. I drank to feel numb.”

Struggled with: Abuse Addiction CPTSD Suicidal

Helped by: Social support Therapy

July 9, 2024

Learning To Live With Irritable Bowel Syndrome With Therapy And A Positive Mindset

“Raising four young children and battling a chronic illness with no cure was challenging for me. On the outside, I looked OK. But I wasn’t and in some ways today still have flare-ups and struggles, the difference is, I now know how to maintain it, especially knowing this will be the rest of my life regardless!”

Struggled with: Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Helped by: Therapy Treatment

July 4, 2024

How A Rescue Dog Helped Me Overcome TBI, Depression and Suicidal Ideation

“I sat on the summer-hot pavement, and no one stopped or asked me if I was okay. No one called the police. People walked around me as quickly as possible. When I was all cried out, I walked home to my empty house. I bought a set of knives, ostensibly for cooking, but that was not the reason. I had thought about pills, and every day I researched how many of each prescription drug I was on would I need to take to die. Using a sharp knife seemed so much easier.”

Struggled with: Depression Suicidal Traumatic Brain Injury

Helped by: Medication Pets Volunteering

July 2, 2024

Walking El Camino de Santiago Helped Me Reconnect With My Authentic Self

“Beneath the outward bravado, I battled with self-doubt and kept wondering why genuine connections seemed beyond my ability. Even though I put out valiant efforts to conceal it, my inner turmoil seeped out, leaving me feeling exposed and vulnerable. And, I knew they could tell.”

Struggled with: Feeling lost People-pleasing Self-doubt

Helped by: Self-acceptance Self-awareness

June 27, 2024

My Journey of Overcoming Heartbreak Thanks to Self-Care and The Support Of Friends

“I’ve learned that finding the right people to confide in, those who offer genuine support and empathy, can make a significant difference in navigating these challenges. It takes time and trust to build those connections, but they are invaluable.”

Struggled with: Breakup

Helped by: Self-Care Social support

June 19, 2024

How Therapy, Self-Help and Medication Help Me Live With Depression and Anxiety

“When the next depressive episode hit in 2018, I was devastated. How could this happen again when I thought I had it all figured out? I experienced some of the darkest moments of my life and a nearly complete loss of hope.”

Struggled with: Anxiety Bipolar Disorder Depression Suicidal

Helped by: Medication Therapy

June 11, 2024

Sharing My Journey From Alcohol and Substance Abuse to Sobriety and Happiness

“I felt prettier, smarter, funnier when alcohol entered my body so I simply continued numbing through the years. The progression of this disease of alcoholism turned into a nasty drug habit and those feelings of insecurity turned into deep darkness when I was “off my meds”. Or in other words, without alcohol or drugs.”

Struggled with: Addiction Depression Suicidal

Helped by: Rehab Therapy

June 4, 2024

Finding Happiness and Self-Love After Escaping Death From Burning 90% Of My Body

“It was like starting life over again, except you know how to do things you physically can’t do, which emotionally drains you. There was definitely a sense of resentment and feeling sorry for myself, I think that is natural. You wonder what you did to deserve that, you wonder if things are ever going to get better, you wonder how people will treat you. When you are confined to a bed for weeks on end, really all you can do is wonder.”

Struggled with: Physical trauma

Helped by: Self-improvement Social support

May 28, 2024

Cognitive Reframing and Mindfulness Helped Me Overcome Depression and Suicidal Ideation

“After exploring ways to end my life, I resolved to slash my wrist. I retrieved a steak knife from the kitchen and pressed it against my skin. Yet, an unexpected sensation washed over me—a profound sense of peace, love, and joy.”

Struggled with: Depression Suicidal

Helped by: Meditation Mindfulness Self-improvement

Case Examples

Examples of recommended interventions in the treatment of depression across the lifespan.

Children/Adolescents

A 15-year-old Puerto Rican female

The adolescent was previously diagnosed with major depressive disorder and treated intermittently with supportive psychotherapy and antidepressants. Her more recent episodes related to her parents’ marital problems and her academic/social difficulties at school. She was treated using cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

Chafey, M.I.J., Bernal, G., & Rossello, J. (2009). Clinical Case Study: CBT for Depression in A Puerto Rican Adolescent. Challenges and Variability in Treatment Response. Depression and Anxiety , 26, 98-103. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20457

Sam, a 15-year-old adolescent

Sam was team captain of his soccer team, but an unexpected fight with another teammate prompted his parents to meet with a clinical psychologist. Sam was diagnosed with major depressive disorder after showing an increase in symptoms over the previous three months. Several recent challenges in his family and romantic life led the therapist to recommend interpersonal psychotherapy for adolescents (IPT-A).

Hall, E.B., & Mufson, L. (2009). Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Depressed Adolescents (IPT-A): A Case Illustration. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 38 (4), 582-593. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410902976338

© Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology (Div. 53) APA, https://sccap53.org/, reprinted by permission of Taylor & Francis Ltd, http://www.tandfonline.com on behalf of the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology (Div. 53) APA.

General Adults

Mark, a 43-year-old male

Mark had a history of depression and sought treatment after his second marriage ended. His depression was characterized as being “controlled by a pattern of interpersonal avoidance.” The behavior/activation therapist asked Mark to complete an activity record to help steer the treatment sessions.

Dimidjian, S., Martell, C.R., Addis, M.E., & Herman-Dunn, R. (2008). Chapter 8: Behavioral activation for depression. In D.H. Barlow (Ed.) Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: A step-by-step treatment manual (4th ed., pp. 343-362). New York: Guilford Press.

Reprinted with permission from Guilford Press.

Denise, a 59-year-old widow

Denise is described as having “nonchronic depression” which appeared most recently at the onset of her husband’s diagnosis with brain cancer. Her symptoms were loneliness, difficulty coping with daily life, and sadness. Treatment included filling out a weekly activity log and identifying/reconstructing automatic thoughts.

Young, J.E., Rygh, J.L., Weinberger, A.D., & Beck, A.T. (2008). Chapter 6: Cognitive therapy for depression. In D.H. Barlow (Ed.) Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: A step-by-step treatment manual (4th ed., pp. 278-287). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Nancy, a 25-year-old single, white female

Nancy described herself as being “trapped by her relationships.” Her intake interview confirmed symptoms of major depressive disorder and the clinician recommended cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Persons, J.B., Davidson, J. & Tompkins, M.A. (2001). A Case Example: Nancy. In Essential Components of Cognitive-Behavior Therapy For Depression (pp. 205-242). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/10389-007

While APA owns the rights to this text, some exhibits are property of the San Francisco Bay Area Center for Cognitive Therapy, which has granted the APA permission for use.

Luke, a 34-year-old male graduate student

Luke is described as having treatment-resistant depression and while not suicidal, hoped that a fatal illness would take his life or that he would just disappear. His treatment involved mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, which helps participants become aware of and recharacterize their overwhelming negative thoughts. It involves regular practice of mindfulness techniques and exercises as one component of therapy.

Sipe, W.E.B., & Eisendrath, S.J. (2014). Chapter 3 — Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy For Treatment-Resistant Depression. In R.A. Baer (Ed.), Mindfulness-Based Treatment Approaches (2nd ed., pp. 66-70). San Diego: Academic Press.

Reprinted with permission from Elsevier.

Sara, a 35-year-old married female

Sara was referred to treatment after having a stillbirth. Sara showed symptoms of grief, or complicated bereavement, and was diagnosed with major depression, recurrent. The clinician recommended interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) for a duration of 12 weeks.

Bleiberg, K.L., & Markowitz, J.C. (2008). Chapter 7: Interpersonal psychotherapy for depression. In D.H. Barlow (Ed.) Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: a treatment manual (4th ed., pp. 315-323). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Peggy, a 52-year-old white, Italian-American widow

Peggy had a history of chronic depression, which flared during her husband’s illness and ultimate death. Guilt was a driving factor of her depressive symptoms, which lasted six months after his death. The clinician treated Peggy with psychodynamic therapy over a period of two years.

Bishop, J., & Lane , R.C. (2003). Psychodynamic Treatment of a Case of Grief Superimposed On Melancholia. Clinical Case Studies , 2(1), 3-19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534650102239085

Several case examples of supportive therapy

Winston, A., Rosenthal, R.N., & Pinsker, H. (2004). Introduction to Supportive Psychotherapy . Arlington, VA : American Psychiatric Publishing.

Older Adults

Several case examples of interpersonal psychotherapy & pharmacotherapy

Miller, M. D., Wolfson, L., Frank, E., Cornes, C., Silberman, R., Ehrenpreis, L.…Reynolds, C. F., III. (1998). Using Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT) in a Combined Psychotherapy/Medication Research Protocol with Depressed Elders: A Descriptive Report With Case Vignettes. Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research , 7(1), 47-55.

Social Work Practice with Carers

Case Study 2: Josef

Download the whole case study as a PDF file

Josef is 16 and lives with his mother, Dorota, who was diagnosed with Bipolar disorder seven years ago. Josef was born in England. His parents are Polish and his father sees him infrequently.

This case study looks at the impact of caring for someone with a mental health problem and of being a young carer , in particular the impact on education and future employment .

When you have looked at the materials for the case study and considered these topics, you can use the critical reflection tool and the action planning tool to consider your own practice.

- One-page profile

Support plan

Transcript (.pdf, 48KB)

Name : Josef Mazur

Gender : Male

Ethnicity : White European

Download resource as a PDF file

First language : English/ Polish

Religion : Roman Catholic

Josef lives in a small town with his mother Dorota who is 39. Dorota was diagnosed with Bi-polar disorder seven years ago after she was admitted to hospital. She is currently unable to work. Josef’s father, Stefan, lives in the same town and he sees him every few weeks. Josef was born in England. His parents are Polish and he speaks Polish at home.

Josef is doing a foundation art course at college. Dorota is quite isolated because she often finds it difficult to leave the house. Dorota takes medication and had regular visits from the Community Psychiatric Nurse when she was diagnosed and support from the Community Mental Health team to sort out her finances. Josef does the shopping and collects prescriptions. He also helps with letters and forms because Dorota doesn’t understand all the English. Dorota gets worried when Josef is out. When Dorota is feeling depressed, Josef stays at home with her. When Dorota is heading for a high, she tries to take Josef to do ‘exciting stuff’ as she calls it. She also spends a lot of money and is very restless.

Josef worries about his mother’s moods. He is worried about her not being happy and concerned at the money she spends when she is in a high mood state. Josef struggles to manage his day around his mother’s demands and to sleep when she is high. Josef has not told anyone about the support he gives to his mother. He is embarrassed by some of the things she does and is teased by his friends, and he does not think of himself as a carer. Josef has recently had trouble keeping up with course work and attendance. He has been invited to a meeting with his tutor to formally review attendance and is worried he will get kicked out. Josef has some friends but he doesn’t have anyone he can confide in. His father doesn’t speak to his mother.

Josef sees some information on line about having a parent with a mental health problem. He sends a contact form to ask for information. Someone rings him and he agrees to come into the young carers’ team and talk to the social worker. You have completed the assessment form with Josef in his words and then done a support plan with him.

Back to Summary

Josef Mazur

What others like and admire about me

Good at football

Finished Arkham Asylum on expert level

What is important to me

Mum being well and happy

Seeing my dad

Being an artist

Seeing my friends

How best to support me

Tell me how to help mum better

Don’t talk down to me

Talk to me 1 to 1

Let me know who to contact if I am worried about something

Work out how I can have some time on my own so I can do my college work and see my friends

Don’t tell mum and my friends

Date chronology completed : 7 March 2016

Date chronology shared with person: 7 March 2016

| 1997 | Josef’s mother and father moved to England from Poznan. | Both worked at the warehouse – Father still works there. |

| 11.11.1999 | Josef born. | Mother worked for some of the time that Josef was young. |

| 2006 | Josef reports that his mother and father started arguing about this time because of money and Josef’s mother not looking after household tasks. | Josef started doing household tasks e.g. cleaning, washing and ironing. |

| 2008 | Josef reports that his mother didn’t get out of bed for a few months. | Josef managed the household during this period. |

| October 2008 | Josef reports that his mother spent lots of money in catalogues and didn’t sleep. She was admitted to hospital. | Mother was in hospital for 6 weeks and was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Josef began looking after his mother’s medication and says that he started to ‘keep an eye on her.’ |

| May 2010 | Josef’s father moved out to live with his friend Kat. Josef stayed with his mother. | Josef reports that his mother was ‘really sad for a while and then she went round and shouted at them.’ Mother started on different medication and had regular visits from the Community Psychiatric Nurse. Josef said that the CPN told him about his mum’s illness and to let him know if he needed any help but he was managing ok. Josef saw his father every week for a few years and then it was more like every month. Father does not visit Josef or speak to his mother. |

| 2013/14 | Josef reports that his mother got into a lot of debt and they had eviction letters. | Josef’s father paid some of the bills and his mother was referred by the Community Mental Health Team for advice from CAB and started getting benefits. Josef started doing the correspondence. |

| 2015 | Josef left school and went to college. | Josef got an A (art), 4 Cs and 3 Ds GCSE. He says that he ‘would have done better but I didn’t do much work.’ |

| 26 Feb 2016 | Josef got a letter from his tutor at college saying he had to go to a formal review about attendance. | Josef saw information on-line about having a parent with a mental health problem and asked for some information. |

| 2 March 2016 | Phone call from young carer’s team to Josef. | Josef agreed to come in for an assessment. |

| 4 March 2016 | Social worker meets with Josef. | Carer’s assessment and support plan completed. |

| 7 March 2016 | Paperwork completed. | Sent to Josef. |

Young Carers Assessment

Do you look after or care for someone at home?

The questions in this paper are designed to help you think about your caring role and what support you might need to make your life a little easier or help you make time for more fun stuff.

Please feel free to make notes, draw pictures or use the form however is best for you.

What will happen to this booklet?

This is your booklet and it is your way to tell an adult who you trust about your caring at home. This will help you and the adult find ways to make your life and your caring role easier.

The adult who works with you on your booklet might be able to help you with everything you need. If they can’t, they might know other people who can.

Our Agreement

- I will share this booklet with people if I think they can help you or your family

- I will let you know who I share this with, unless I am worried about your safety, about crime or cannot contact you

- Only I or someone from my team will share this booklet

- I will make sure this booklet is stored securely

- Some details from this booklet might be used for monitoring purposes, which is how we check that we are working with everyone we should be

Signed: ___________________________________

Young person:

- I know that this booklet might get shared with other people who can help me and my family so that I don’t have to explain it all over again

- I understand what my worker will do with this booklet and the information in it (written above).

Signed: ____________________________________

Name : Josef Mazur Address : 1 Green Avenue, Churchville, ZZ1 Z11 Telephone: 012345 123456 Email: [email protected] Gender : Male Date of birth : 11.11.1999 Age: 16 School : Green College, Churchville Ethnicity : White European First language : English/ Polish Religion : Baptised Roman Catholic GP : Dr Amp, Hill Surgery

The best way to get in touch with me is:

Do you need any support with communication?

*Josef is bilingual – English and Polish. He speaks English at school and with his friends, and Polish at home. Josef was happy to have this assessment in English, however, another time he may want to have a Polish interpreter. It will be important to ensure that Josef is able to use the words he feels best express himself.

About the person/ people I care for

I look after my mum who has bipolar disorder. Mum doesn’t work and doesn’t really leave the house unless she is heading for a high. When Mum is sad she just stays at home. When she is getting hyper then she wants to do exciting stuff and she spends lots of money and she doesn’t sleep.

Do you wish you knew more about their illness?

Do you live with the person you care for?

What I do as a carer It depends on if my mum has a bad day or not. When she is depressed she likes me to stay home with her and when she is getting hyper then she wants me to go out with her. If she has new meds then I like to be around. Mum doesn’t understand English very well (she is from Poland) so I do all the letters. I help out at home and help her with getting her medication.

Tell us what an average week is like for you, what kind of things do you usually do?

Monday to Friday

Get up, get breakfast, make sure mum has her pills, tell her to get up and remind her if she’s got something to do.

If mum hasn’t been to bed then encourage her to sleep a bit and set an alarm

College – keep phone on in case mum needs to call – she usually does to ask me to get something or check when I’m coming home

Go home – go to shops on the way

Remind mum about tablets, make tea and pudding for both of us as well as cleaning the house and fitting tea in-between, ironing, hoovering, hanging out and bringing in washing

Do college work when mum goes to bed if not too tired

More chores

Do proper shop

Get prescription

See my friends, do college work

Sunday – do paper round

Physical things I do….

(for example cooking, cleaning, medication, shopping, dressing, lifting, carrying, caring in the night, making doctors appointments, bathing, paying bills, caring for brothers & sisters)

I do all the housework and shopping and cooking and get medication

Things I find difficult

Emotional support I provide…. (please tell us about the things you do to support the person you care for with their feelings; this might include, reassuring them, stopping them from getting angry, looking after them if they have been drinking alcohol or taking drugs, keeping an eye on them, helping them to relax)

If mum is stressed I stay with her

If mum is depressed I have to keep things calm and try to lighten the mood

She likes me to be around

When mum is heading for a high wants to go to theme parks or book holidays and we can’t afford it

I worry that mum might end up in hospital again

Mum gets cross if I go out

Other support

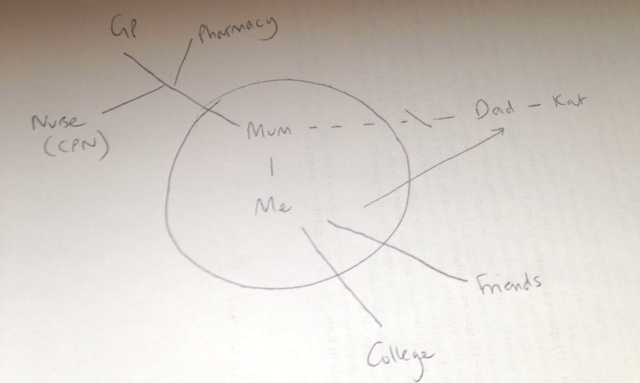

Please tell us about any other support the person you care for already has in place like a doctor or nurse, or other family or friends.

The GP sees mum sometimes. She has a nurse who she can call if things get bad.

Mum’s medication comes from Morrison’s pharmacy.

Dad lives nearby but he doesn’t talk to mum.

Mum doesn’t really have any friends.

Do you ever have to stop the person you care for from trying to harm themselves or others?

Some things I need help with

Sorting out bills and having more time for myself

I would like mum to have more support and to have some friends and things to do

On a normal week, what are the best bits? What do you enjoy the most? (eg, seeing friends, playing sports, your favourite lessons at school)

Seeing friends

When mum is up and smiling

Playing football

On a normal week, what are the worst bits? What do you enjoy the least? (eg cleaning up, particular lessons at school, things you find boring or upsetting)

Nagging mum to get up

Reading letters

Missing class

Mum shouting

Friends laugh because I have to go home but they don’t have to do anything

What things do you like to do in your spare time?

Do you feel you have enough time to spend with your friends or family doing things you enjoy, most weeks?

Do you have enough time for yourself to do the things you enjoy, most weeks? (for example, spending time with friends, hobbies, sports)

Are there things that you would like to do, but can’t because of your role as a carer?

Can you say what some of these things are?

See friends after college

Go out at the weekend

Time to myself at home

It can feel a bit lonely

I’d like my mum to be like a normal mum

School/ College Do you think being your caring role makes school/college more difficult for you in any way?

If you ticked YES, please tell us what things are made difficult and what things might help you.

Things I find difficult at school/ college

Sometimes I get stressed about college and end up doing college work really late at night – I get a bit angry when I’m stressed

I don’t get all my college work done and I miss days

I am tired a lot of the time

Things I need help with…

I am really worried they will kick me out because I am behind and I miss class. I have to meet my tutor about it.

Do your teachers know about your caring role?

Are you happy for your teachers and other staff at school/college to know about your caring role?

Do you think that being a carer will make it more difficult for you to find or keep a job?

Why do you think being a carer is/ will make finding a job more difficult?

I haven’t thought about it. I don’t know if I’ll be able to finish my course and do art and then I won’t be able to be an artist.

Who will look after mum?

What would make it easier for you to find a job after school/college?

Finishing my course

Mum being ok

How I feel about life…

Do you feel confident both in school and outside of school?

Somewhere in the middle

In your life in general, how happy do you feel?

Quite unhappy

In your life in general, how safe do you feel?

How healthy do you feel at the moment?

Quite healthy

Being heard

Do you think people listen to what you are saying and how you are feeling?

If you said no, can you tell us who you feel isn’t listening or understanding you sometimes (eg, you parents, your teachers, your friends, professionals)

I haven’t told anyone

I can’t talk to mum

My friends laugh at me because I don’t go out

Do you think you are included in important decisions about you and your life? (eg, where you live, where you go to school etc)

Do you think that you’re free to make your own choices about what you do and who you spend your time with?

Not often enough

Is there anybody who knows about the caring you’re doing at the moment?

If so, who?

I told dad but he can’t do anything

Would you like someone to talk to?

Supporting me Some things that would make my life easier, help me with my caring or make me feel better

I don’t know

Fix mum’s brain

People to help me if I’m worried and they can do something about it

Not getting kicked out of college

Free time – time on my own to calm down and do work or have time to myself

Time to go out with my friends

Get some friends for mum

I don’t want my mum to get into trouble

Who can I turn to for advice or support?

I would like to be able to talk to someone without mum or friends knowing

Would you like a break from your caring role?

How easy is it to see a Doctor if you need to?

To be used by social care assessors to consider and record measures which can be taken to assist the carer with their caring role to reduce the significant impact of any needs. This should include networks of support, community services and the persons own strengths. To be eligible the carer must have significant difficulty achieving 1 or more outcomes without support; it is the assessors’ professional judgement that unless this need is met there will be a significant impact on the carer’s wellbeing. Social care funding will only be made available to meet eligible outcomes that cannot be met in any other way, i.e. social care funding is only available to meet unmet eligible needs.

Date assessment completed : 7 March 2016

Social care assessor conclusion

Josef provides daily support to his mum, Dorota, who was diagnosed with bipolar disorder seven years ago. Josef helps Dorota with managing correspondence, medication and all household tasks including shopping. When Dorota has a low mood, Josef provides support and encouragement to get up. When Dorota has a high mood, Josef helps to calm her and prevent her spending lots of money. Josef reports that Dorota has some input from community health services but there is no other support. Josef’s dad is not involved though Josef sees him sometimes, and there are no friends who can support Dorota.

Josef is a great support to his mum and is a loving son. He wants to make sure his mum is ok. However, caring for his mum is impacting: on Josef’s health because he is tired and stressed; on his emotional wellbeing as he can get angry and anxious; on his relationship with his mother and his friends; and on his education. Josef is at risk of leaving college. Josef wants to be able to support his mum better. He also needs time for himself, to develop and to relax, and to plan his future.

Eligibility decision : Eligible for support

What’s happening next : Create support plan

Completed by Name : Role : Organisation :

Name: Josef Mazur

Address 1 Green Avenue, Churchville, ZZ1 Z11

Telephone 012345 123456

Email [email protected]

Gender: Male

Date of birth: 11.11.1999 Age: 16

School Green College, Churchville

Ethnicity White European

First language English/ Polish

Religion Baptised Roman Catholic

GP Dr Amp, Hill Surgery

My relationship to this person son

Name Dorota Mazur

Gender Female

Date of birth 12.6.79 Age 36

First language Polish

Religion Roman Catholic

Support plan completed by

Organisation

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

| ||

|

| ||

Date of support plan: 7 March 2016

This plan will be reviewed on: 7 September 2016

Signing this form

Please ensure you read the statement below in bold, then sign and date the form.

I understand that completing this form will lead to a computer record being made which will be treated confidentially. The council will hold this information for the purpose of providing information, advice and support to meet my needs. To be able to do this the information may be shared with relevant NHS Agencies and providers of carers’ services. This will also help reduce the number of times I am asked for the same information.

If I have given details about someone else, I will make sure that they know about this.

I understand that the information I provide on this form will only be shared as allowed by the Data Protection Act.

Josef has given consent to share this support plan with the CPN but does not want it to be shared with his mum.

Mental health

The social work role with carers in adult mental health services has been described as: intervening and showing professional leadership and skill in situations characterised by high levels of social, family and interpersonal complexity, risk and ambiguity (Allen 2014). Social work with carers of people with mental health needs, is dependent on good practice with the Mental Capacity Act where practitioner knowledge and understanding has been found to be variable (Iliffe et al 2015).

- Carers Trust (2015) Mental Health Act 1983 – Revised Code of Practice Briefing

- Carers Trust (2013) The Triangle of Care Carers Included: A Guide to Best Practice in Mental Health Care in England

- Mind, Talking about mental health

- Tool 1: Triangle of care: self-assessment for mental health professionals – Carers Trust (2013) The Triangle of Care Carers Included: A Guide to Best Practice in Mental Health Care in England Second Edition (page 23 Self-assessment tool for organisations)

Mental capacity, confidentiality and consent

Social work with carers of people with mental health needs, is dependent on good practice with the Mental Capacity Act where practitioner knowledge and understanding has been found to be variable (Iliffe et al 2015). Research highlights important issues about involvement, consent and confidentiality in working with carers (RiPfA 2016, SCIE 2015, Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland 2013).

- Beddow, A., Cooper, M., Morriss, L., (2015) A CPD curriculum guide for social workers on the application of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 . Department of Health

- Bogg, D. and Chamberlain, S. (2015) Mental Capacity Act 2005 in Practice Learning Materials for Adult Social Workers . Department of Health

- Department of Health (2015) Best Interest Assessor Capabilities , The College of Social Work

- RiPfA Good Decision Making Practitioner Handbook

- SCIE Mental Capacity Act resource

- Tool 2: Making good decisions, capacity tool (page 70-71 in good decision making handbook)

Young carers

A young carer is defined as a person under 18 who provides or intends to provide care for another person. The concept of care includes practical or emotional support. It is the case that this definition excludes children providing care as part of contracted work or as voluntary work. However, the local authority can ignore this and carry out a young carer’s need assessment if they think it would be appropriate. Young carers, young adult carers and their families now have stronger rights to be identified, offered information, receive an assessment and be supported using a whole-family approach (Carers Trust 2015).

- SCIE (2015) Young carer transition in practice under the Care Act 2014

- SCIE (2015) Care Act: Transition from children’s to adult services – early and comprehensive identification

- Carers Trust (2015) Rights for young carers and young adult carers in the Children and Families Act

- Carers Trust (2015) Know your Rights: Support for Young Carers and Young Adult Carers in England

- The Children’s Society (2015) Hidden from view: The experiences of young carers in England

- DfE (2011) Improving support for young carers – family focused approaches

- ADASS and ADCS (2015) No wrong doors: working together to support young carers and their families

- Carers Trust, Supporting Young Carers and their Families: Examples of Practice

- Refugee toolkit webpage: Children and informal interpreting

- SCIE (2010) Supporting carers: the cared for person

- SCIE (2015) Care Act Transition from children’s to adults’ services – Video diaries

- Tool 3: Young carers’ rights – The Children’s Society (2014) The Know Your Rights pack for young carers in England!

- Tool 4: Vision and principles for adults’ and children’s services to work together

Young carers of parents with mental health problems

The Care Act places a duty on local authorities to assess young carers before they turn 18, so that they have the information they need to plan for their future. This is referred to as a transition assessment. Guidance, advocating a whole family approach, is available to social workers (LGA 2015, SCIE 2015, ADASS/ADCS 2011).

- SCIE (2012) At a glance 55: Think child, think parent, think family: Putting it into practice

- SCIE (2008) Research briefing 24: Experiences of children and young people caring for a parent with a mental health problem

- SCIE (2008) SCIE Research briefing 29: Black and minority ethnic parents with mental health problems and their children

- Carers Trust (2015) The Triangle of Care for Young Carers and Young Adult Carers: A Guide for Mental Health Professionals

- ADASS and ADCS (2011) Working together to improve outcomes for young carers in families affected by enduring parental mental illness or substance misuse

- Ofsted (2013) What about the children? Joint working between adult and children’s services when parents or carers have mental ill health and/or drug and alcohol problems

- Mental health foundation (2010) MyCare The challenges facing young carers of parents with a severe mental illness

- Children’s Commissioner (2012) Silent voices: supporting children and young people affected by parental alcohol misuse

- SCIE, Parental mental health and child welfare – a young person’s story

Tool 5: Family model for assessment

- Tool 6: Engaging young carers of parents with mental health problems or substance misuse

Young carers and education/ employment

Transition moments are highlighted in the research across the life course (Blythe 2010, Grant et al 2010). Complex transitions required smooth transfers, adequate support and dedicated professionals (Petch 2010). Understanding transition theory remains essential in social work practice (Crawford and Walker 2010). Partnership building expertise used by practitioners was seen as particular pertinent to transition for a young carer (Heyman 2013).

- TLAP (2013) Making it real for young carers

- Learning and Work Institute (2018) Barriers to employment for young adult carers

- Carers Trust (2014) Young Adult Carers at College and University

- Carers Trust (2013) Young Adult Carers at School: Experiences and Perceptions of Caring and Education

- Carers Trust (2014) Young Adult Carers and Employment

- Family Action (2012) BE BOTHERED! Making Education Count for Young Carers

Download The Triangle of Care as a PDF file

The Triangle of Care Carers Included: A Guide to Best Practice in Mental Health Care in England

The Triangle of Care is a therapeutic alliance between service user, staff member and carer that promotes safety, supports recovery and sustains wellbeing…

Download the Capacity Tool as a PDF file

Capacity Tool Good decision-making Practitioners’ Handbook

The Capacity tool on page 71 has been developed to take into account the lessons from research and the case CC v KK. In particular:

- that capacity assessors often do not clearly present the available options (especially those they find undesirable) to the person being assessed

- that capacity assessors often do not explore and enable a person’s own understanding and perception of the risks and advantages of different options

- that capacity assessors often do not reflect upon the extent to which their ‘protection imperative’ has influenced an assessment, which may lead them to conclude that a person’s tolerance of risks is evidence of incapacity.

The tool allows you to follow steps to ensure you support people as far as possible to make their own decisions and that you record what you have done.

Download Know your rights as a PDF file

Tool 3: Know Your Rights Young Carers in Focus

This pack aims to make you aware of your rights – your human rights, your legal rights, and your rights to access things like benefits, support and advice.

Need to know where to find things out in a hurry? Our pack has lots of links to useful and interesting resources that can help you – and help raise awareness about young carers’ issues!

Know Your Rights has been produced by Young Carers in Focus (YCiF), and funded by the Big Lottery Fund.

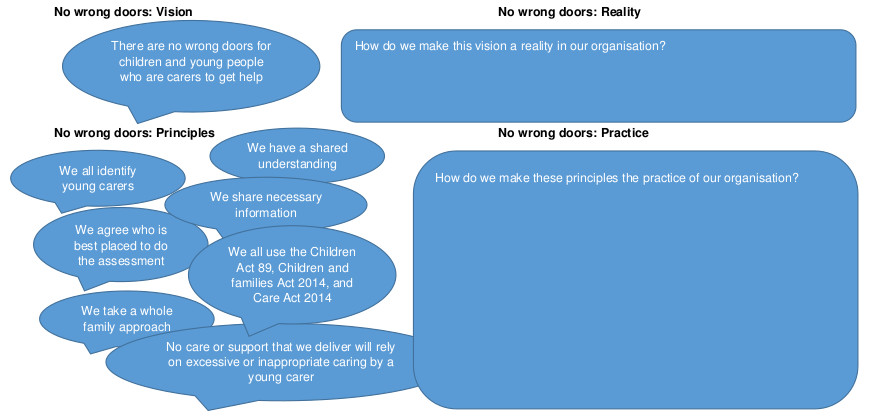

Tool 4: Vision and principles for adults’ and children’s services to work together to support young carers

Download the tool as a PDF file

You can use this tool to consider how well adults’ and children’s services work together, and how to improve this.

Click on the diagram to open full size in a new window

This is based on ADASS and ADCS (2015) No wrong doors : working together to support young carers and their families

Download the tool as a PDF file

You can use this tool to help you consider the whole family in an assessment or review.

What are the risk, stressors and vulnerability factors?

How is the child/ young person’s wellbeing affected?

How is the adult’s wellbeing affected?

What are the protective factors and available resources?

This tool is based on SCIE (2009) Think child, think parent, think family: a guide to parental mental health and child welfare

Tool 6: Engaging young carers

Young carers have told us these ten things are important. So we will do them.

- Introduce yourself. Tell us who you are and what your job is.

- Give us as much information as you can.

- Tell us what is wrong with our parents.

- Tell us what is going to happen next.

- Talk to us and listen to us. Remember it is not hard to speak to us we are not aliens.

- Ask us what we know and what we think. We live with our parents; we know how they have been behaving.

- Tell us it is not our fault. We can feel guilty if our mum or dad is ill. We need to know we are not to blame.

- Please don’t ignore us. Remember we are part of the family and we live there too.

- Keep on talking to us and keeping us informed. We need to know what is happening.

- Tell us if there is anyone we can talk to. Maybe it could be you.

- Equal opportunities

- Complaints procedure

- Terms and conditions

- Privacy policy

- Cookie policy

- Accessibility

A two-way street: Mental health can’t be ignored during work injury recovery

Assistant Professor, John Molson School of Business, Concordia University

Professor of Organizational Behaviour and Future Fund Chair in Leadership, Haskayne School of Business, University of Calgary

Disclosure statement

Steve Granger receives research funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Nick Turner currently receives research funding from Cenovus Energy Inc., Mitacs, and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Concordia University and University of Calgary provide funding as founding partners of The Conversation CA.

Universitié Concordia provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation CA-FR.

University of Calgary provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA-FR.

View all partners

Discussions about mental health in the workplace have surged lately, driven by growing awareness of its impact on employee and organizational success . As occupational health researchers, these discussions have helped us shed light on the precursors and consequences of mental health challenges.

One such critical but often overlooked aspect is the relationship between mental health challenges and work injuries — a relationship that goes in both directions : struggling with mental health can increase the risk of work injuries, and work injuries can give rise to, or worsen, mental health challenges.

We aimed to shed light on this crucial bidirectional relationship because it undermines the sustainability of an organization’s most crucial asset: its people.

Mental health and work injuries

Mental health challenges and work injuries result in significant costs for organizations and society, and tremendous suffering among individuals and their families, workplaces and wider support systems.

While the costs for work injuries and mental health challenges vary widely, evidence indicates that experiencing both together can multiply medical expenses and time loss from two to 10 times.

Despite their impact, the critical relationship between work injuries and mental health challenges has only been examined sporadically across diverse disciplines, which rarely communicate with each other — until now.

Our comprehensive meta-analysis , involving a worldwide sample of more than 1.4 million participants across 147 studies conducted since 1988, highlights the need for integrated approaches to address physical and psychological well-being in the workplace.

Meta-analytical studies like ours are valuable because they involve systematically gathering and summarizing all existing quantitative research. This approach helps us consolidate and distil the findings from multiple studies, providing a clearer picture of what we currently understand.

Our findings reveal that the relationship between work injuries and mental health depends on whether someone expriences mental health challenges or workplace injuries first. A stronger, more robust relationship emerges when work injuries precede mental health challenges, while a smaller, but still significant, association exists when mental health challenges precede work injuries.

The hidden toll of work injuries

When a work injury occurs, the immediate focus is on physical recovery. However, the psychological impact of injuries shouldn’t be neglected.

The sudden disruption caused by a work injury can lead to increased stress, anxiety and depression. This psychological distress can stem from various factors, including pain, stigma and uncertainty about one’s ability to continue earning a living.

Our analysis indicates that negative thoughts, such as rumination, commonly arise after work injuries. They play a significant role in the development of mental health challenges. These negative thoughts can lead to a downward spiral, mentally trapping an injured individual in their situation and further hindering their recovery process.

Interestingly, the relationship is not one-way. Our research also shows that mental health challenges are associated with an increased likelihood of sustaining a work injury.

Individuals struggling with mental health often experience reduced cognitive functioning, increased distractibility and impaired decision-making abilities, making regular job duties increasingly overwhelming and difficult to manage. These factors can lead to a higher risk of injuries at work.

For example, an employee dealing with severe depression might have difficulty concentrating on tasks, increasing the risk of overlooking emerging hazards or misjudging dangerous situations.

The stigma associated with their mental health condition might also prevent the employee from seeking the help or accommodations they need, further increasing their vulnerability to work injuries.

Breaking the vicious cycle

The interconnected nature of work injuries and mental health challenges highlights the need for comprehensive rehabilitation approaches. Integrating psychological care into the rehabilitation process is crucial for promoting overall well-being and preventing the recurrence of injuries.

Employers and policymakers should consider implementing programs that address both the physical and mental health needs of employees. This includes providing access to and awareness of mental health services , promoting a safe and supportive work environment and implementing strategies to reduce workplace stress.

By taking a human sustainability approach that emphasizes physical, psychological and social health through prevention rather than reaction, it’s possible to break the cycle of work injuries and mental health challenges. This could ultimately lead to healthier and more productive workplaces.

Improving human sustainability

Our study paves the way for future research and interventions aimed at mitigating the impact of work injuries on mental health and vice versa. Recognizing this bidirectional relationship is the first step towards creating more effective interventions and support systems.

Understanding the underlying mechanisms, such as negative thoughts and perceived job demands, can help when designing targeted interventions that address the root causes of these issues.

Additionally, understanding factors that influence the connection between work injuries and mental health — like how severe or often injuries occur, the types of mental health challenges that may arise and specific vulnerable groups — can provide valuable insights for developing tailored strategies.

By integrating physical and psychological care, we can ensure both aspects receive the attention they rightfully deserve in promoting human sustainability and enhancing the quality of life for workers across all industries.

- Mental health

- Employee health

- workplace injuries

- Health and well-being

Educational Designer

Lecturer, Small Animal Clinical Studies (Primary Care)

Organizational Behaviour – Assistant / Associate Professor (Tenure-Track)

Apply for State Library of Queensland's next round of research opportunities

Associate Professor, Psychology

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Burnout in Mental Health Services: A Review of the Problem and Its Remediation

Places for People: Community Alternatives for Hope, Health and Recovery

Michelle P. Salyers

Center of Excellence on Implementing Evidence-Based Practice, Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development Service (VA HSR&D); Associate Professor, Department of Psychology, IUPUI; Co-Director, ACT Center of Indiana

Angela L. Rollins

Center of Excellence on Implementing Evidence-Based Practice, VA HSR&D; Assistant Research Professor, Department of Psychology, IUPUI; Research Director, ACT Center of Indiana

Maria Monroe-DeVita

Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Washington

Corey Pfahler

Social Work, IUPUI

Staff burnout is increasingly viewed as a concern in the mental health field. In this article we first examine the extent to which burnout is a problem for mental health services in terms of two critical issues: its prevalence and its association with a range of undesirable outcomes for staff, organizations, and consumers. We subsequently provide a comprehensive review of the limited research attempting to remediate burnout among mental health staff. We conclude with recommendations for the development and rigorous testing of intervention approaches to address this critical area. Keywords: burnout, burnout prevention, mental health staff

Introduction

Burnout has been defined a number of ways ( Burke & Richardsen, 1993 ; Chemiss, 1980 ; Pines & Aronson, 1988 ; Stalker & Harvey, 2002 ), but most researchers favor a multifaceted definition developed by Maslach and colleagues (1993 ; 1996) that encompasses three dimensions: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment. The dimension of emotional exhaustion refers to feelings of being depleted, overextended, and fatigued. Depersonalization (also called cynicism) refers to negative and cynical attitudes toward one’s consumers or work in general. A reduced sense of personal accomplishment (or efficacy) involves negative self-evaluation of one’s work with consumers or overall job effectiveness ( Stalker & Harvey, 2002 ). Many researchers consider burnout to be a job-related stress condition or even a “work-related mental health impairment” (( Awa, Plaumann, & Walter, 2010 ), p. 184); in fact, burnout closely resembles the ICD-10 diagnosis of job-related neurasthenia ( Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter, 2001 ; Organization, 1992 ). Although burnout is correlated with other mental health conditions, such as anxiety and depression, research also supports that burnout is a construct distinct from these other mental health disorders, from a general stress reaction, and from other work phenomena such as job dissatisfaction ( Awa, et al., 2010 ; Maslach, et al., 2001 ). Burnout is also distinct from secondary traumatization, vicarious traumatization, and compassion fatigue ( Canfield, 2005 ; Dunkley & Whelan, 2006 ; Figley, 1995 ).

Since burnout was first described in the early 1970s, thousands of conceptual papers and empirical studies have focused on this complex phenomenon. As research has burgeoned over the past three decades, it has become clear that burnout, which occurs cross culturally, is prevalent across a variety of occupations, including teachers, managers and clerical workers, and in a variety of fields, including education, business, criminal justice, and computer technology ( Leiter & Schaufeli, 1996 ; Stalker & Harvey, 2002 ). Not surprisingly, burnout is also thought to be common among mental health service providers and administrators, and to be increasing for employees in public service systems ( Awa, et al., 2010 ). In public mental health, burnout is considered to be costly and “economically wasteful”, especially given the expense of recruiting and training staff (p. 7, ( Gilbody et al., 2006 ). Recently, the United States federal government also identified burnout as one key factor driving the “major problem” of retaining competent staff in “treatment organizations and state behavioral health systems” (p. 16, ( Hoge et al., 2007 )). Some studies have examined limited aspects of burnout among mental health providers, but there have been relatively few systematic attempts to better understand or ameliorate burnout in mental health; this is both surprising and ironic, given the goals of mental health organizations for improving the behavioral health of individuals and the fact that burnout is a stress-related psychological condition that arises within the workplace.

Given the complexity of the topic and the vast prior work on burnout, this review is not meant to be exhaustive; instead, we focus on two key questions: 1) To what extent is burnout a problem for mental health staff and the service delivery system? 2) What can — and should — be done to address burnout among mental health providers? We build upon a prior review of burnout and mental health ( Leiter & Harvie, 1996 ) while also incorporating key issues and findings from other reviews and empirical studies in the general field of burnout. Throughout the paper, we seek to identify areas important for further research and intervention, before making final conclusions and recommendations for research and practice. While another useful review of mental health and burnout was recently published ( Paris & Hoge, 2010 ), our review is different in that it emphasizes the full range of problems associated with burnout, a comprehensive review of the intervention literature, and new research and development strategies for remediating burnout.

Burnout: The Scope of the Problem for the Mental Health Field

We will examine the extent to which burnout is a problem in the mental health field in terms of two key areas: 1) the prevalence of burnout among mental health providers, and 2) the association of burnout with other problems for mental health staff and service delivery. Prevalence

Across several studies, it appears that 21-67% of mental health workers may be experiencing high levels of burnout. In a study of 151 community mental health workers in Northern California, Webster and Hackett (1999) found that 54% had high emotional exhaustion and 38% reported high depersonalization rates, but most reported high levels of personal accomplishment as well. In Rohland’s (2000) sample of 29 directors of community mental health centers in Iowa, over two-thirds reported high emotional exhaustion and low personal accomplishment. Further, almost half reported high levels of depersonalization. Siebert (2005) surveyed a state chapter of social workers, and of the 751 respondents, 36% scored in the high range of emotional exhaustion. The investigators also used a single item burnout measure and 18% of the sample endorsed the statement: “I currently have problems with burnout.” Oddie and colleagues (2007) examined 71 forensic mental health workers in the UK, and 54% reported high rates of emotional exhaustion. Prior United Kingdom studies reviewed by Oddie and colleagues (2007) also reported a range of 21% to 48% of general mental health workers as having high emotional exhaustion.

Differences in burnout between various mental health occupational types have yielded some evidence for higher burnout among community social workers compared to nurses and psychiatrists in one study in two European cities ( Priebe, Fakhoury, Hoffmann, & Powell, 2005 ), with an exception noted in an older study in Great Britain ( Onyett, Pillinger, & Muijen, 1997 ) where emotional exhaustion on the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI; Maslach, Jackson, & Leiter, 1996 ) —the most frequently used measure of burnout--was relatively high across the entire sample. Some research has noted lower job satisfaction for social workers compared to psychiatrists ( Prosser et al., 1997 ), but most mental health burnout studies have not compared rates of burnout across professions or disciplines. For instance, many studies either focus on burnout rates for single professional groups of interest (e.g., nurses, psychologists, social workers) or aggregate burnout findings across a wider swath of disciplines working within a single service type (e.g, psychosocial rehabilitation workers or staff of an intensive case management team; see studies in ( Leiter & Harvie, 1996 ; Taris, 2006 )). Prosser et al. (1997) found some differences in burnout and related factors between inpatient and community-based work settings, with inpatient staff experiencing lower levels of burnout and work stress compared to community-based staff. Rupert and Kent (2007) found higher levels of personal accomplishment for psychologists working independently or in group practices compared to psychologists working in “agency” settings, such as hospitals or community-based programs. Comparative rates of problematic burnout could give helpful clues on whether and/or how to target and package burnout interventions for various disciplines or program types.

Even though burnout is frequently mentioned as a problem in the mental health field (e.g., ( Edwards, Burnard, Coyle, Fothergill, & Hannigan, 2000 ), the construct is typically measured as a continuous variable so that the actual prevalence of “burnout” is difficult to quantify. In order to help address this issue, Maslach, Jackson, and Leiter (1996) presented score ranges on the MBI to conceptualize low, average, and high levels of burnout based on large normative samples for various occupations. For mental health workers, high levels of burnout included emotional exhaustion scores of at least 21, depersonalization scores of at least 8, and personal accomplishment scores of 28 or below; note, however, that these cut-off scores for “high” burnout in mental health workers are relatively low compared to other occupational groups. Research shows that continuous data scores on the MBI are predictive of other problems (see Maslach et al., 2001 ), but empirical validation of the cut-points for “high” burnout on the MBI is lacking. Therefore, literature using these cut-offs should be evaluated with some skepticism, namely that the low cut-off scores for “high” burnout in mental health may inflate the prevalence of burnout in some studies. On the other hand, one could argue that lower rates of burnout still deserve attention, since even “mild” burnout has been associated with increased risk for mental health problems ( Ahola et al., 2005 ). Either way, external validation studies with strong methodologies (e.g. representative sampling, higher response rates, longitudinal designs) are sorely needed for determining problematic levels of burnout. For instance, validation studies might determine what levels of burnout are associated with poor staff performance measures, staff intentions to leave the organization, staff health problems, or poor consumer outcomes.

Stability of the burnout construct is another area of need in future research. Burke and Richardsen (1993) reviewed several studies in the general literature which suggest that the level of burnout remains fairly stable across time if untreated. Of particular interest is Burke and Richardsen’s conclusion that burnout often becomes a chronic condition, and that after one year, about 40% of workers remain in the same stage of burnout, about 30% become more burned out, and about another 30% become less burned out. The lack of longitudinal research in the mental health field makes this topic another important area for further study.

Although methodological problems are common in many prevalence studies, the rates across studies indicate that burnout may indeed be widespread among mental health workers, and there is reason to believe that rates will continue to increase. As public sector funding for mental health is either constant or reduced (see California’s recent state budget cuts to social services, e.g., ( Goldmacher, 2009 ) and the costs for employee healthcare benefits and other expenses continue to rise, some mental health agencies are increasing staff “productivity” standards for billable services. In an already stressful work domain, the added pressures and responsibilities are likely to be triggers for greater levels of burnout.

Associated Problems for the Mental Health Field

Burnout has been associated with a large number of negative conditions affecting different types of employees, their organizations, and the consumers they serve. These undesirable situations are briefly highlighted below. We refer the reader to reviews in the general literature and larger population-based studies, and highlight studies specifically addressing mental health workers where data are available. One important caveat – we refer to consequences or outcomes of burnout, although many of these findings are derived from cross-sectional studies, making it difficult to firmly conclude whether the conditions are the outcomes of burnout rather than noncausal correlates or even antecedents.

The empirical and theoretical literature suggests that the consequences of burnout can be severe and far-reaching. Employees who experience burnout often experience impaired emotional and physical health and a diminished sense of well-being ( Stalker & Harvey, 2002 ). Some population-based studies, not specifically focused on mental health workers, have shown correlations between burnout and aspects of physical and mental health. For example, Peterson and colleagues (2008) studied a sample of service workers in a Swedish city (N = 1252) including nurses, physicians, social workers, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, dentists, dental hygienists, administrators, teachers, and technicians. Burnout was associated with increased depression, anxiety, sleep problems, impaired memory, neck and back pain, and alcohol consumption. Ahola and colleagues (2005) investigated the relationship between job-related burnout and depressive disorders in 3,276 workers in Finland. Based on a standardized clinical interview, individuals with mild burnout were at 3.3 times more risk of having major depressive disorder, and those with severe burnout were 15 times more likely to have major depressive disorder. The risk of having a major depressive disorder with severe burnout was greater for men than for women, with the risk of a major depressive disorder 10.2 fold for women and 29.5 fold for men.

Health issues have also been linked to mental health provider burnout. In a study of 591 social workers in NY, Acker (2010) found that high levels of burnout, particularly emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, were related to greater reports of flu-like symptoms and symptoms of gastroenteritis. Notably, social workers with greater levels of involvement with consumers with severe mental illness reported higher levels of burnout. Burnout has also been correlated with increased substance use in directors of mental health agencies ( Rohland, 2000 ).

Employee burnout has been correlated with a number of negative organizational measures, including reduced commitment to the organization ( Burke & Richardsen, 1993 ), negative attitudes ( Chemiss, 1980 ), and often absenteeism and turnover ( Schwab, Jackson, & Schuler, 1986 ; Smoot & Gonzolas, 1995 ; Stalker & Harvey, 2002 ). Not surprising, burnout is related to job dissatisfaction ( Maslach, et al., 2001 ; Prosser, et al., 1997 ; Schulz, Greenley, & Brown, 1995 ) and burnout may also damage the morale of other employees and lead to staff turnover ( Stalker & Harvey, 2002 ). In a longitudinal study of 3,895 employees (non mental health workers) who worked in a large industry corporation, Toppinen-Tanner and colleagues (2005) found that burnout predicted future sick leave, even after controlling for the effects of age, gender, occupation, and previous absence. High levels of burnout increased the risk of absence related to mental and behavioral disorders, as well as diseases of the circulatory, respiratory, and musculoskeletal systems. In mental health, staff absences and turnover are correlated with reduced fidelity to evidence-based practices ( Mancini et al., 2009 ; Rollins, Salyers, Tsai, & Lydick, 2010 ) and increase the costs of recruiting and training new staff.

Over time, the cumulative effects of managing a consumer caseload can lead to fatigue, exhaustion and burnout ( Ducharme, Knudsen, & Roman, 2008 ). In turn, burnout may also impact care provided to mental health service consumers. Although few studies have actually examined the relationship of burnout to quality of care, burnout and staff turnover are believed to disrupt the continuity of mental health care ( Boyer & Bond, 1999 ) and to undermine the quality of services provided ( Carney, Donovan, Yurdin, & Starr, 1993 ; Hoge, et al., 2007 ; Maslach & Pines, 1979 ). High levels of burnout signify that workers possess insufficient resources to deal with the demands of their jobs, leading to impaired job performance. Employees with high levels of burnout may not be willing to expend effort, leading to suboptimal functioning at work ( Taris, 2006 ). In addition, burned out workers may be less able to be empathic, collaborative, and attentive -- characteristics that have been associated with higher consumer satisfaction ( Corrigan, 1990 ). In the general burnout literature, Taris (2006) performed a systematic literature review on burnout and objective performance, subsequently reviewing 16 articles. In 5 articles, high levels of exhaustion were associated with low levels of role performance, and in three articles examining consumer satisfaction, higher levels of exhaustion resulted in lower customer service ratings. Indeed, burnout among nurses and general medicine physicians has been found to be related to decreased patient satisfaction ( Halbesleben & Rathert, 2008 ; Leiter, Harvie, & Frizzell, 1998 ).

Burnout has also been empirically associated with negative feelings about mental health consumers. A study of 510 psychiatric workers in 28 different units ( Holmqvist & Jeanneau, 2006 ) found that high levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization were correlated with negative attitudes (e.g., distant, rejecting) toward consumers on their ward. Negative staff attitudes, in turn, have been linked with poorer outcomes among consumers with severe mental illness ( Gowdy, Carlson, & Rapp, 2003 ). In a study empirically linking burnout to poor consumer satisfaction, Garman and colleagues (2002) surveyed 333 mental health staff on 31 different teams serving people with severe mental illness. Team level emotional exhaustion, but not depersonalization, was significantly related to average consumer satisfaction scores for those teams.

Overall, burnout has been associated with a variety of other negative conditions at the level of the individual, organization, and to some extent, quality of services provided. The vast majority of these studies, however, have been cross-sectional and correlational. So, the idea of “burnout consequences” may not accurately capture the direction of relationships. For example, staff who are already experiencing high levels of physical health problems may feel added work pressure and report high levels of emotional exhaustion as a result of their pre-existing health problem. Conversely, a third variable, for example, underlying depression or anxiety, could manifest in both high levels of burnout and greater preoccupation with physical health concerns. As well, associated problems may moderate burnout through complex, multivariate pathways. For example, in research on 43 mental health organizations in Wisconsin, Schulz, Greenley, and Brown (1995) found that a number of organizational, management, and job variables predicted job satisfaction, not burnout directly, but job satisfaction moderated employees’ levels of burnout. In addition to the lack of clear directionality, we found only a handful of studies specifically assessing potential consequences of burnout in mental health workers. However, there is little reason to believe that burnout would affect mental health workers differently than nurses, teachers, or other professional groups where additional research describes strong relationships between burnout and a range of associated problems. Nonetheless, future research should include mental health workers and use larger samples, longitudinal designs, and multivariate models to better examine the relationship between burnout and associated problems.

Reducing Burnout

Mental health staff.

Despite its prevalence and association with a number of negative outcomes, little attention has been directed toward reducing or preventing burnout among mental health professionals. The need for burnout prevention and interventions for mental health providers has been highlighted by researchers for decades ( Pines & Maslach, 1978 ), but few such programs have actually been implemented and evaluated. At the time of their review, Leiter and Harvie (1996) reported only one intervention study specific to mental health workers. We conducted an updated review of this literature for this paper. Specifically, we ran computerized literature searches using the terms burnout, mental health professionals and personnel using the PsychInfo database from 1987 through 2010. In addition, we manually examined citations and reference lists in original articles on burnout and in reviews in overlapping areas (e.g., ( Awa, et al., 2010 ; Gilbody, et al., 2006 ; Paris & Hoge, 2010 )) to identify other studies of burnout interventions for mental health staff. To be included in the present paper, the intervention study must have included (a) a planned method or strategy designed to reduce or prevent burnout, (b) sample participants who met the inclusion criteria as mental health staff (related disciplines, such as substance abuse counselors, were excluded) and who served persons with mental health disorders (one study with staff serving primary dementia, was excluded); (c) an outcome variable specifically measuring burnout; and (d) a quasi-experimental or experimental research design. Prior to summarizing these approaches, it is important to note that most studies in any occupational field have not differentiated between programs designed to prevent burnout from those developed to help employees recover from burnout. To some extent, this tendency may arise from theorists conceptualizing burnout along a continuum. It remains to be seen, however, whether the same strategies are effective for both reducing as well as preventing burnout. Regardless, intervention programming and research could benefit from further specification and clarity on this issue.

Our search identified eight studies, which are described in detail in Table 1 . Perhaps the most striking observations concerned the settings of the studies. As shown, six (75%) of the eight studies were conducted in European countries, while only two were conducted in the United States. Further, at least five (62.5%) of the eight studies involved staff working in psychiatric inpatient settings, and only one study clearly evaluated burnout prevention in a community mental health setting. Four (50%) of the studies were conducted with psychiatric nurses exclusively.

Controlled Intervention Studies to Improve Burnout Among Mental Health Staff

| Study | Participants | Setting | Design | Intervention | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Halberg 1994 | 11 nurses (Sweden) | Psychiatric inpatient (child/adol escent) | Quasi-exp Pre-Post: Baseline, 6 and 12 month | Group psycho-dynamic clinical supervision for emotional reactions (14 2-hour sessions over 1 year) | NS changes for burnout; Significant decrease for tedium |

| 326 nurses (Netherlands) | Psychiatric inpatient | Quasi-exp 2 Pretest, 1 Post, nonequivalent groups | Primary nursing model plus special supervisor feedback vs usual treatment | NS changes for burnout; Trend toward less turnover; However, attrition >50%, problems with treatment diffusion. | |

| 35 direct care and clinical staff | Psychiatric residential program | Pre-Post | Staff training needs assessment, planning and training on psychiatric rehabilitation. 90 minute trainings for 8 months | Significant reduction on EE for direct care but not clinical staff; NS on DP and PA; Significant improved attitudes about behavioral interventions, satisfaction with staff support | |

| 352 “direct care professionals” (Netherlands) | Not specified | Quasi exp Pre-Post for Exp and 2 nonequivalent comparisons | Cognitive behavioral training (1/2 day per week for 5 weeks to improve equity; 3 sessions for supervisors, to improve communication & social skills | EE reduced at 6 months, but NS at 12 months; NS change in DP; PA significant at 6 mos vs. external comparison group but NS at 12 mos, and NS vs. internal comparison group; Absences | |

| Carson et al., 1999 | 53 nurses (UK) | Psychiatric inpatient | RCT | Social support group vs feedback-only on stress level plus stress management handout; 2 hours × 5 weeks | NS change for EE and DP PA, Control improved at post-test, NS at 6 months; 36% attrition at 6 months |

| 20 forensic nurses (UK) | Psychiatric inpatient | RCT | Psychosocial intervention training (6 weeks) vs waiting list control | Significant decrease in EE and DP, and increased PA; significantly improved knowledge, attitudes re: SMI | |

| 25 mental health staff (14 direct care, 11 managers) | Psychiatric inpatient, residential, day programs, (Italy) | Quasi-exp (pretest, post-test, follow-up) | Assertiveness training (3 hr workshops monthly for 5 mos) plus one additional workshop: CBT for handling emotions while serving consumers (direct care) or task planning, leadership style, supporting staff (managers) | NS change in EE; DP decreased at post-test and 18 mos; PA worse at post-test; NS at 18 mos | |

| 84 mental health staff | Communit y mental health | Quasi-exp 2 pre-test, post test (6 weeks) | Day workshop to improve awareness and skills (contemplative, cognitive, social, etc.) | EE reduced; DP reduced; NS change in PA Improved optimism re: consumers |

NS = Not significant; EE= Emotional Exhaustion; DP = Depersonalization; PA=Personal Accomplishment

In terms of research design, two studies conducted randomized controlled trials (RCTs) while the remainder employed quasi-experimental designs, such as nonequivalent control groups or simple pre-post designs (sometimes using multiple pretests or multiple posttests). Follow-up periods ranged from a simple post-test at the completion of the intervention to one-year follow-ups. Three of the studies experienced high rates of research attrition and four studies used small samples. The types of interventions also ranged widely. Most of the intervention programs involved multiple training and/or supervision sessions spread over a period of weeks or months, although one program involved a single day workshop.