Appraising systematic reviews

Systematic reviews may or may not include a meta-analysis of the primary RCTs identified. Although systematic reviews of RCTs with meta-analysis are often said to provide the most compelling evidence of effectiveness and causality, not all systematic reviews are of the highest methodological quality.

There are numerous checklists available. The SR toolbox is an online catalogue providing summaries and links to the available guidance and software for each stage of the systematic review process including critical appraisal. Examples for systematic reviews include:

- AMSTAR 2 (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews)

- CASP systematic review checklist.

The following framework forms an initial memory aid for assessing the quality of a systematic review.

- Framework for assessing systematic reviews

Content created by BMJ Knowledge Centre

- What is EBM?

- How to clarify a clinical question

- Searching for evidence

- Search strategies

- Case study of a search

- Appraise the evidence

- Evidence synthesis

- What is GRADE?

- Understanding statistics: BMJ Learning modules

- Understanding statistics: risk

EBM Toolkit home

Learn, Practise, Discuss, Tools

- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Specialty Certificate Examination Cases

- Cover Archive

- Virtual Issues

- Trending Articles

- Author Guidelines

- Reviewer Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Reasons to Publish

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About Clinical and Experimental Dermatology

- About British Association of Dermatologists

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Discussion and conclusions, learning points, funding sources, data availability, ethics statement, cpd questions, instructions for answering questions.

- < Previous

How to critically appraise a systematic review: an aide for the reader and reviewer

Conflicts of interest H.W. founded the Cochrane Skin Group in 1987 and was coordinator editor until 2018. The other authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

John Frewen, Marianne de Brito, Anjali Pathak, Richard Barlow, Hywel C Williams, How to critically appraise a systematic review: an aide for the reader and reviewer, Clinical and Experimental Dermatology , Volume 48, Issue 8, August 2023, Pages 854–859, https://doi.org/10.1093/ced/llad141

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The number of published systematic reviews has soared rapidly in recent years. Sadly, the quality of most systematic reviews in dermatology is substandard. With the continued increase in exposure to systematic reviews, and their potential to influence clinical practice, we sought to describe a sequence of useful tips for the busy clinician reader to determine study quality and clinical utility. Important factors to consider when assessing systematic reviews include: determining the motivation to performing the study, establishing if the study protocol was prepublished, assessing quality of reporting using the PRISMA checklist, assessing study quality using the AMSTAR 2 critical appraisal checklist, assessing for evidence of spin, and summarizing the main strengths and limitations of the study to determine if it could change clinical practice. Having a set of heuristics to consider when reading systematic reviews serves to save time, enabling assessment of quality in a structured way, and come to a prompt conclusion of the merits of a review article in order to inform the care of dermatology patients.

A systematic review aims to systematically and transparently summarize the available data on a defined clinical question, via a rigorous search for studies, a critique of the quality of included studies and a qualitative and/or quantitative synthesis. 1 Systematic reviews are at the top of the pyramid in most evidence hierarchies for informing evidence-based healthcare as they are considered of greater validity and clinical applicability than those study types lower down, such as case series or individual trials. 2

A good systematic review should provide an unbiased overview of studies to inform clinical practice. Systematic reviews can reconcile apparently conflicting results, add precision to estimating smaller treatment effects, highlight the evidence’s limitations and biases and identify research gaps. Guidelines are available to assist systematic reviewers to transparently report why the review was done, the authors’ methods and findings via the PRISMA checklist. 3

The sharp rise in systematic review publications over time raises concern that the majority are unnecessary, misleading and/or conflicted. 4 A review of dermatology systematic reviews noted that 93% failed to report at least one PRISMA checklist item. 5 Another review of a random sample of 140/732 dermatology systematic reviews in 2017 found 90% were low quality. 6 Some improvements have occurred: reporting standards compliance has improved slightly (between 2013 and 2017), 5 and several leading dermatology journals including the British Journal of Dermatology have changed editorial policies, mandating authors to preregister review protocols.

Given the surge in poor-quality systematic review publications, we sought to describe a checklist of seven practical tips from the authors’ collective experience of writing and critically appraising systematic reviews, hoping that they will assist busy clinicians to critically appraise systematic reviews both as manuscript reviewers and as readers and research users.

Read the abstract to develop a sense of the subject.

What was the motivation for completing the review?

Has the review protocol been published and have changes been made to it.

Review the reporting quality .

Review the quality of the article and the depth of the review question.

Consider the authors’ interpretation and assess for spin .

Summarize and come to a position .

Read the abstract to develop a sense of the subject

From the abstract, use the PICO (population, intervention, comparator and outcome) framework to establish if the subject, intervention and outcomes are relevant to clinical practice. Is the review question clear and appropriate?

Inspect the authors’ conflicts of interest and funding sources. Self-disclosed financial conflicts are often insufficiently described or not declared at all. 7 If you suspect conflicts for authors with no stated conflicts, briefly searching the senior authors’ names on PubMed, or the Open Payments website (for US authors) may reveal hidden conflicts. 8 Is the motivation for the systematic review justified in the introduction? Can new insights be formed by combining studies? If the systematic review is an update, what new available data justifies this? Search for similar recent systematic reviews (which may have been omitted intentionally). Is it a redundant duplicate review that adds little new useful information? 9 Has the author recently published reviews on similar subjects? Salami publications refer to authors chopping up a topic into smaller pieces to obtain maximum publications. 10

Search PROSPERO for publication of the review protocol. 11 A prepublished review protocol in a publicly accessible site offers reassurance that the systematic review followed a clear plan with prespecified PICO elements. Put bluntly, it reduces authors’ opportunity for deception by selective analysis and highlighting of results that are more likely to get published. If a protocol is found, assess deviation from this protocol and justification, if present. Protocol registration allows improved PRISMA reporting. 12 A registered protocol with reporting of deviations allows the reader to judge whether any modifications are justified, for example adjusting for unexpected challenges during analysis. 10

Review the reporting quality

Look for supplementary material detailing the PRISMA checklist. Commonly under-reported PRISMA items include protocol and registration, risk of bias across studies, risk of bias in individual studies, the data collection process and review objectives. 5 Adequate reporting quality using PRISMA does not necessarily indicate the review is clinically useful; however, it allows the reader to assess the study’s utility (see Table 1 ). Additional assessments of review quality are described below.

The relationship between systematic review reporting quality and study quality a

Adapted with permission from Williams. 21

Review the quality of the article and the depth of the review question

Distinct from quality of reporting completeness, assessing the review's quality allows for assessment of the overall clinical meaningfulness of the results. Does the PICO make sense in respect to this? The AMSTAR 2 critical appraisal instrument is useful in determining quantitative systematic review quality. 13 This checklist marks the key aspects of a systematic review and computes an outcome of the review quality. 14 If meta-analysis was performed, did the authors justify and use appropriate methods for statistical combination of results? Were weighted techniques used to combine results and adjusted for heterogeneity, if present? If heterogeneity was present, were sources of this investigated? Did authors assess the potential impact of the individual study’s risk of bias (RoB) and perform analysis to investigate the impact of RoB on the summary estimates of affect? See Table 2 for an example of a completed AMSTAR 2 checklist on a recently published poor-quality systematic review. 15

An example of assessment of the quality of a systematic review (Drake et al. ) 15 using the AMSTAR 2 checklist an explanation of which can be found at https://amstar.ca/Amstar-2.php

N/A, not applicable; PICO, population, intervention, comparator and outcome. a Denotes AMSTAR 2 critical domain. The overall confidence in the results of the review is dependent on such critical domains. When one critical domain is not satisfied, the confidence is rated as ‘low’ and the review may not provide an accurate and comprehensive summary of the available studies that address the question of interest. When more than one critical domain are not satisfied, the confidence in the results of the review is rated as ‘critically low’ and the review should not be relied on to provide an accurate and comprehensive summary of the available studies.

Quality checklists for assessment of qualitative research include Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative research (COREQ), Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) and Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). 16 Such checklists aim to improve identification of high-quality qualitative research in journal articles, as well as acting as a guide for conducting research. 16

Consider the authors’ interpretation and assess for spin

Spin is a distorted interpretation of results. This manifests itself in studies as (i) misleading reporting, (ii) misleading interpretation, and (iii) inappropriate extrapolation. 14 Are the conclusion’s clinical practice recommendations not supported by the studies’ findings? Is the title misleading? Is there selective reporting? These are the three most severe forms of spin occurring in systematic reviews. 17

Summarize and come to a position

Summarize the reviews main positives and negatives and establish if there is sufficient quality to merit changing clinical practice, or are fatal flaws present that nullify the review’s clinical utility? Consider internal validity (are the results true?) and external validity (are the results applicable to my patient group?). When applying the systematic review results to a particular patient, it may help to consider these points: (i) how similar are the study participants to my patient?; (ii) do the outcomes make sense to me?; (iii) what was the magnitude of treatment benefit? – work out the number needed to treat; 18 (iv) what are the adverse events?; and (v) what are my patient's values and preferences? 19

Although systematic reviews have potential for summarizing evidence for dermatological interventions in a systematic and unbiased way, the rapid expansion of poorly reported and poor-quality reviews (Table 3 ) is regrettable. We do not claim our checklist items (Table 4 ) are superior to other checklists such as those suggested by CASP, 20 but they are based on the practical experience of critical appraisal of dermatology systematic reviews conducted by the authors.

The top seven ‘sins’ of dermatology systematic reviews a

Adapted with permission from Williams. 10

Checklist of questions, considerations and tips for critical appraisal of systematic reviews

NNT, number needed to treat.

Considering each question suggested in our checklist when faced with yet another systematic review draws a timely conclusion on its quality and application to clinical practice, when acting as a reviewer or reader. Although the checklist may sound exhaustive and time-consuming, we recommend cutting it short if there are major red flags early on, such as absence of a protocol or assessment of RoB. Given the growing number of systematic reviews, having an efficient and succinct aide for appraising articles saves the reader time and energy, while simplifying the decision regarding what merits a change in clinical practice. Our intention is not to criticize others’ well-intentioned efforts, but to improve standards of reliable evidence to inform patient care.

Systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials offer one of the best methods to summarize the evidence surrounding therapeutic interventions for skin conditions.

The number of systematic reviews in the dermatology literature is increasing rapidly.

The quality of dermatology systematic reviews is generally poor.

We describe a checklist for the busy clinician or reviewer to consider when faced with a systematic review.

Key factors to consider include: determining the review motivation, establishing if the study protocol was prepublished, assessing quality of reporting and study quality using PRISMA, and AMSTAR 2 critical appraisal checklists, and assessing for evidence of spin.

Summarizing the main qualities and limitations of a systematic review will help to determine if the review is robust enough to potentially change clinical practice for patient benefit.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

No new data generated.

Ethical approval: not applicable. Informed consent: not applicable.

Moher D , Liberati A , Tetzlaff J et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement . Ann Intern Med 2009 ; 151 : 264 – 9 .

Google Scholar

Murad MH , Asi N , Alsawas M , Alahdab F . New evidence pyramid . Evid Based Med 2016 ; 21 : 125 – 7 .

Page MJ , McKenzie JE , Bossuyt PM et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews . BMJ 2021 ; 372 : n71 .

Ioannidis JP . The mass production of redundant, misleading, and conflicted systematic reviews and meta-analyses . Milbank Q 2016 ; 94 : 485 – 514 .

Croitoru DO , Huang Y , Kurdina A et al. Quality of reporting in systematic reviews published in dermatology journals . Br J Dermatol 2020 ; 182 : 1469 – 76 .

Smires S , Afach S , Mazaud C et al. Quality and reporting completeness of systematic reviews and meta-analyses in dermatology . J Invest Dermatol 2021 ; 141 : 64 – 71 .

Baraldi JH , Picozzo SA , Arnold JC et al. A cross-sectional examination of conflict-of-interest disclosures of physician-authors publishing in high-impact US medical journals . BMJ Open 2022 ; 12 : e057598 .

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Open Payments Search Tool. About. Available at : https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/about (last accessed 22 April 2023).

Guelimi R , Afach S , Régnaux JP et al. Overlapping network meta-analyses on psoriasis systemic treatments, an overview: quantity does not make quality . Br J Dermatol 2022 ; 187 : 29 – 41 .

Williams HC . Are dermatology systematic reviews spinning out of control? Dermatology 2021 ; 237 : 493 – 5 .

National Institute for Health and Care Research . About Prospero. Available at : https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/#aboutpage (last accessed 22 April 2023).

Barbieri JS , Wehner MR . Systematic reviews in dermatology: opportunities for improvement . Br J Dermatol 2020 ; 182 : 1329 – 30 .

Shea BJ , Reeves BC , Wells G et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both . BMJ 2017 ; 358 : j4008 .

AMSTAR . AMSTAR checklist. Available at : https://amstar.ca/Amstar_Checklist.php (last accessed 22 April 2023).

Drake L , Reyes-Hadsall S , Martinez J et al. Evaluation of the safety and effectiveness of nutritional supplements for treating hair loss: a systematic review . JAMA Dermatol 2023 ; 159 : 79 – 86 .

Stenfors T , Kajamaa A , Bennett D . How to … assess the quality of qualitative research . Clin Teach 2020 ; 17 : 596 – 9 .

Yavchitz A , Ravaud P , Altman DG et al. A new classification of spin in systematic reviews and meta-analyses was developed and ranked according to the severity . J Clin Epidemiol 2016 ; 75 : 56 – 65 .

Manriquez JJ , Villouta MF , Williams HC . Evidence-based dermatology: number needed to treat and its relation to other risk measures . J Am Acad Dermatol 2007 ; 56 : 664 – 71 .

Williams HC . Applying trial evidence back to the patient . Arch Dermatol 2003 ; 139 : 1195 – 200 .

CASP . CASP checklists. Available at : https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (last accessed 22 April 2023).

Williams HC . Cars, CONSORT 2010, and clinical practice . Trials 2010 ; 11 : 33 .

Learning objective

To demonstrate up-to-date knowledge on assessing systematic reviews.

Which of the following critical appraisal checklists is useful for assessment of items that should be reported in a systematic review?

Which one of the following statements is correct?

The number of published systematic reviews in the dermatology literature is falling.

The quality of published dermatology systematic reviews is generally very good.

Publishing details of the PRISMA checklist in a systematic review indicates that the study quality is high.

External validity refers to the applicability of results to your patient group.

Internal validity refers to the applicability of results to your patient group.

Spin in systematic reviews can be described by which one of the following measures?

Authors declaring all conflicts of interest.

Title suggesting beneficial effect not supported by findings.

Adequate reporting of study limitations.

Conclusion formulating recommendations for clinical practice supported by findings.

Reporting a departure from study protocol that may modify interpretation of results.

PICO stands for which of the following.

PubMed, inclusion, comparator, outcome.

Population, items, comparator, outcome.

Population, intervention, context, observations.

Protocol, intervention, certainty, outcome.

Population, intervention, comparator, outcome.

Publication of a systematic review study protocol can be found at which source?

Cochrane Library.

ClinicalTrials.gov.

This learning activity is freely available online at https://oupce.rievent.com/a/TWWDCK

Users are encouraged to

Read the article in print or online, paying particular attention to the learning points and any author conflict of interest disclosures.

Reflect on the article.

Register or login online at https://oupce.rievent.com/a/TWWDCK and answer the CPD questions.

Complete the required evaluation component of the activity.

Once the test is passed, you will receive a certificate and the learning activity can be added to your RCP CPD diary as a self-certified entry.

This activity will be available for CPD credit for 5 years following its publication date. At that time, it will be reviewed and potentially updated and extended for an additional period.

Author notes

Email alerts, citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1365-2230

- Copyright © 2024 British Association of Dermatologists

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Asking a clear question

- Sources of evidence within a systematic review

- The hazards of "quick" searches

- Publication bias

- Data abstraction

- Pooling results

- Article Information

See More About

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Others Also Liked

- Download PDF

- X Facebook More LinkedIn

Bigby M , Williams H. Appraising Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139(6):795–798. doi:10.1001/archderm.139.6.795

Manage citations:

© 2024

- Permissions

Appraising Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses

A systematic review is an overview that answers a specific clinical question and contains a thorough, unbiased search of the relevant literature, explicit criteria for assessing studies, and a structured presentation of the results. Many systematic reviews incorporate a meta-analysis, ie, a quantitative pooling of several similar studies to produce an overall summary of treatment effect. 1 , 2 Meta-analysis provides an objective and quantitative summary of evidence that is amenable to statistical analysis, 1 and it allows recognition of important treatment effects by combining the results of small trials that individually might have lacked the power to consistently demonstrate differences among treatments. Meta-analysis has been criticized for the discrepancies between its findings and those of large clinical trials. 3 - 6 The frequency of discrepancies ranges from 10% to 23% 3 and can often be explained by differences in treatment protocols or study populations or changes that occur over time. 3

In conducting a meta-analysis, the authors should recognize the importance of having clear objectives, explicit criteria for study selection, an assessment of the quality of included studies, and prior consideration of which studies to combine. These items are the esssential features of a systematic review. Meta-analyses that are not conducted within the context of a systematic review should be viewed with great caution. 7

A systematic review can be viewed as a scientific and systematic examination of the available evidence. A good systematic review will have explicitly stated objectives (the focused clinical question), materials (the relevant medical literature), and methods (the way studies are assessed and summarized). The steps taken during a systematic review are detailed in Table 1 .

Not all systematic reviews and meta-analyses are equal. A systematic review should be conducted in a manner that will include all of the relevant trials, minimize the introduction of bias, and synthesize the results to be as truthful and useful to clinicians as possible. A systematic review can only be as good as the clinical trials that it contains. The criteria used to critically appraise systematic reviews and meta-analyses 8 are listed in Table 2 . In general, these criteria are similar to the criteria used to appraise the individual studies that make up the systematic review. Detailed explanations of each criterion are available. 1

The validity criteria are designed to ensure that the systematic review is conducted in a manner that minimizes the introduction of bias. Like the "well-built clinical question" 9 for an individual study, a focused clinical question for a systematic review should clearly articulate the following 4 elements of the material under review: (1) the patient, group of patients, or problem being evaluated; (2) the intervention; (3) comparison interventions; and (4) specific outcomes. The patient populations in the reviewed studies should be similar to the actual population most likely to benefit from the review results. The interventions studied should be those commonly available in practice. Outcomes reported should be those that are most relevant to physicians and patients.

The overwhelming majority of systematic reviews involve therapy. Therefore, randomized, controlled, clinical trials should be used when available for systematic reviews of therapy because they are generally less susceptible to selection and information bias than other study designs. The quality of included trials is assessed using the criteria that are used to evaluate individual, randomized, controlled clinical trials. The quality criteria commonly used include concealed, random allocation; groups with similar known prognostic factors; equal treatment of groups; and inclusion of all trial patients in the results analysis (intent-to-treat design).

Randomized controlled trials are rarely a reliable source of identification of adverse reactions, unless those reactions are very common. Other evidence sources such as case-control studies, case reports, and postmarketing surveillance studies should therefore be examined. Systematic reviews of treatment efficacy should always include an assessment of common and serious adverse events to reach an informed and balanced decision about the utility of a treatment.

A sound systematic review can be performed only if most or all of the available data are examined. Simply performing a quick MEDLINE search using "clinical trial" as publication type is rarely adequate because complex and sensitive search strategies are needed to identify all potential trials and because some clinical trials will be missed if they are published in a journal not listed by MEDLINE. Potential sources for finding studies about treatment include the Cochrane Controlled Trials Registry, which is part of the Cochrane Library; MEDLINE; EMBASE; bibliographies of studies; review articles and textbooks; symposia proceedings; pharmaceutical companies; and direct communication with experts in the field.

The Cochrane Controlled Trials Registry, the largest and most complete database of clinical trials in the world, includes more than 300 000 controlled clinical trials. It is compiled through several complex searches of the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases and by hand searching many journals, a process that is quality controlled and monitored by the Cochrane Collaboration in Oxford, England. Hand searching journals to identify controlled clinical trials and randomized, controlled clinical trials was undertaken because members of the Cochrane Collaboration noticed that many trials were incorrectly classified in the MEDLINE database. As an example, Adetugbo and Williams 10 hand searched the Archives of Dermatology from 1990 through 1998 and identified 99 controlled clinical trials. Nineteen of these trials were not classified as controlled clinical trials in MEDLINE, and 11 trials that were not controlled clinical trials were misclassified as controlled clinical trials in MEDLINE. 10

MEDLINE is the National Library of Medicine's bibliographic database covering medicine, nursing, dentistry, veterinary medicine, the health care system, and the preclinical sciences. The MEDLINE file contains bibliographic citations and author abstracts from approximately 3900 current biomedical journals published in the United States and 70 foreign countries. The file contains approximately 9 million records dating back to 1966. 11

MEDLINE searches have inherent limitations that make their reliability less than ideal. 12 For example, Spuls et al 13 conducted a systematic review of systemic treatments of psoriasis. Treatments analyzed included UV-B, psoralen plus UV-A, methotrexate, cyclosporin A, and retinoids. To find relevant references, the authors used an exhaustive strategy that included searching MEDLINE, contacting pharmaceutical companies, polling leading authorities, reviewing abstract books of symposia and congresses, and reviewing textbooks, reviews, editorials, guideline articles, and the reference lists of all articles identified. Of 665 studies found, 356 (54%) were identified by MEDLINE search (30%-70% for different treatment modalities). 13

EMBASE is Excerpta Medica's database covering drugs, pharmacology, and biomedical specialties. 1 EMBASE has better coverage of European and non-English language sources than MEDLINE and may be more up to date. 1 The overlap in journals covered by MEDLINE and EMBASE is about 34% (10%-75%, depending on the subject). 14 , 15

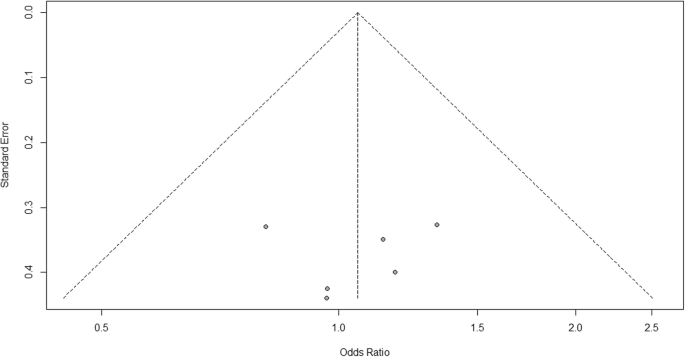

Publication bias (ie, the tendency of easy-to-locate studies to show more "positive" effects) is an important concern for systematic reviews, and a useful analysis of this issue can be found elsewhere. 16 Publication bias results when issues other than the quality of the study are allowed to influence the decision to publish. Several studies have shown that factors such as sample size, direction and statistical significance of findings, and investigators' perceptions of whether the findings are "interesting" are related to the likelihood of publication. 17 , 18

Language bias may also be a problem: studies with positive findings are more likely to be published in an English-language journal and also more quickly than those with inconclusive or negative findings. 19 A thorough systematic review should therefore include a search for high-quality unpublished trials and not restrict itself to journals written in English.

Studies with small samples are less likely to be published than those with larger samples, especially if they have negative results. 17 , 18 This type of publication bias jeopardizes one of the main goals of meta-analysis: to increase power by pooling the results of numerous small studies. Creation of study registers and advance publication of research designs have been proposed as ways to prevent publication bias. 20 , 21

Publication bias can be detected by using a simple graphic test (funnel plot) or by calculating the "fail-safe N." 22 , 23 These techniques are of limited value when fewer than 10 randomized controlled trials are included.

For many diseases, the studies published are dominated by drug company–sponsored trials of new expensive treatments. This bias in publication can result in data-driven systematic reviews that draw more attention to those medicines. In contrast, question-driven systematic reviews answer the sorts of clinical questions of most concern to practitioners. In many cases, studies that are of most relevance to doctors and patients have not been done in the field of dermatology owing to inadequate sources of independent funding.

Systematic reviews that have been sponsored directly or indirectly by industry are also prone to bias by overinclusion of unpublished studies with positive findings that are kept "on file" by that industry. Until it becomes mandatory to register all clinical trials conducted on human beings in a central registry and to make all of the results available in the public domain, all sorts of distortions due to selective withholding or release of data may occur.

Generally, reviews that have been conducted by volunteers in the Cochrane Collaboration are of better quality than non-Cochrane reviews. 24 However, potentially serious errors have been noted in up to a third of Cochrane reviews. 25

In general, the studies included in systematic reviews are reviewed by at least 2 reviewers. Data such as numbers of people entered into studies, numbers lost to follow-up, effects sizes, and quality criteria are recorded on predesigned data abstraction forms by at least 2 reviewers. Differences among reviewers are usually settled by consensus or by a third-person arbitrator. A systematic review in which there are large areas of disagreement among reviewers should lead the reader to question the validity of the review.

Results in the individual clinical trials that make up a systematic review may be similar in magnitude and direction (eg, they may all indicate that treatment A is superior to treatment B by a similar magnitude). Assuming that publication bias can be excluded, systematic reviews of studies with findings that are similar in magnitude and direction provide results that are most likely to be true and useful. It may be impossible to draw firm conclusions from systematic reviews of studies that have results of widely different magnitude and direction.

The magnitude of the difference between the treatment groups in achieving meaningful outcomes is the most useful summary result of a systematic review. The most easily understood measures of the magnitude of the treatment effect are the difference in response rate and its reciprocal, the number needed to treat (NNT). 1 , 8 , 12 The NNT represents the number of patients one would need to treat to achieve 1 additional cure. Whereas the interpretation of NNT might be straightforward within a single trial, interpretation of NNT requires some caution within a systematic review because this statistic is highly sensitive to baseline event rates. For example, if treatment A is 30% more effective than treatment B for clearing psoriasis, and 50% of people who undergo treatment B are cleared with therapy, then 65% will clear with treatment A. These results correspond to a rate difference of 15% (65 − 50) and an NNT of 7 (1.00/0.15). This difference sounds quite worthwhile clinically. But if the baseline clearance rate for treatment B in another trial or setting is only 30%, the rate difference will be only 9%, and the NNT now becomes 11, and if the baseline clearance rate is 10%, then the NNT for treatment A will be 33, which is perhaps less worthwhile. In other words, it rarely makes sense to provide 1 NNT summary measure within a systematic review because "control" or baseline events rates usually differ considerably between studies owing to differences in study populations, interventions, and trial conditions. 26 Instead, a range of NNTs for a range of plausible control event rates that occur in different clinical settings should be given, along with their 95% confidence intervals.

The precision of the estimate of the differences among treatments should be estimated. The confidence interval provides a useful measure of the precision of the treatment effect. 1 , 8 , 12 , 27 , 28 The calculation and interpretation of confidence intervals has been extensively described. 29 In simple terms, the reported result (known as the point estimate ) provides the best estimate of the treatment effect. The population or "true" response to treatment will most likely lie near the middle of the confidence interval and will rarely be found at or near the ends of the interval. The population or true response to treatment has only a 1 in 20 chance of being outside the 95% confidence interval.

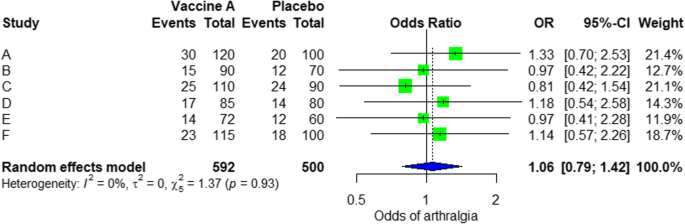

Certain conditions must be met when meta-analysis is performed to synthesize results from different trials. The trials should have conceptual homogeneity. They must involve similar patient populations, have used similar treatments, and have measured results in a similar fashion at a similar point in time. There are 2 main statistical models used to combine results: random effects models and fixed effects models. Random effects models assume that the different studies' results may come from different populations with varying responses to treatment. Fixed effects models assume that each trial represents a random sample of a single population with a single response to treatment. In general, random effects models are more conservative (ie, less likely to show statistically significant results) than fixed effects models. When the combined studies have statistical homogeneity (ie, when the studies are reasonably similar), random effects and fixed effects models give similar results.

The key principle to keep in mind when considering combining results from several studies is that conceptual homogeneity precedes statistical homogeneity. In other words, results of several different studies should not be combined if it does not make sense to combine them (eg, if the patient groups or interventions studied are not sufficiently similar to each other). Although what constitutes "sufficiently similar" is a matter of judgment, the important thing is to explicitly articulate the decision to combine or not combine different studies. Tests for statistical heterogeneity are typically of very low power, so that statistical homogeneity does not mean clinical homogeneity. When there is evidence of heterogeneity, reasons for heterogeneity between studies such as different disease subgroups, intervention dosage, or study quality should be sought.

Sometimes, the robustness of an overall meta-analysis is tested further by means of a sensitivity analysis. In a sensitivity analysis the data are reanalyzed excluding those studies that are suspect because of quality or patient factors, to see whether their exclusion makes a substantial difference in the direction or magnitude of the main original results. In some systematic reviews in which a large number of trials have been performed, it is possible to evaluate whether certain subgroups (eg, children vs adults) are more likely to benefit than others. Subgroup analysis is rarely possible in dermatology because few trials are available.

The conclusions in the discussion section of a systematic review should closely reflect the data that have been presented within that review. The authors should make it clear which of the treatment recommendations are based on the review data and which reflect their own judgments. In addition to making clinical recommendations of therapies when evidence exists, many reviews in dermatology find little evidence to address the questions posed. This lack of conclusive evidence does not mean that the review is a waste of time, especially if the question addressed appears to be an important one. For example, the systematic review of antistreptococcal therapy for guttate psoriasis by Owen et al 30 provided the authors with an opportunity to call for primary research in this area and to make recommendations on study design and outcomes that might help future researchers.

Applying evidence summarized in a systematic review to specific patients requires the same processes used to apply the results of individual controlled clinical trials to patients.

Section Editors

Michael E. Bigby, MD, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Mass Rosamaria Corona, DSc, MD, Istituto Dermopatico dell'Immacolata, Rome, Italy Damiano Abeni, MD, MPH, Paolo Pasquini, MD, MPH, Istituto Dermopatico dell'Immacolata Moyses Szklo, MD, MPH, DrPH, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Md Hywel Williams, MSc, PhD, FRCP, Queen's Medical Centre, Nottingham, England

Corresponding author and reprints: Michael Bigby, MD, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, 330 Brookline Ave, Boston, MA 02215 (e-mail: [email protected] ).

Accepted for publication February 6, 2003.

This article is being published in Williams H. Evidence-Based Dermatology . London, England: BMJ Books; 2003. Further details on this book can be found at http://www.evidbasedderm.com .

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

- Mayo Clinic Libraries

- Systematic Reviews

- Critical Appraisal by Study Design

Systematic Reviews: Critical Appraisal by Study Design

- Knowledge Synthesis Comparison

- Knowledge Synthesis Decision Tree

- Standards & Reporting Results

- Materials in the Mayo Clinic Libraries

- Training Resources

- Review Teams

- Develop & Refine Your Research Question

- Develop a Timeline

- Project Management

- Communication

- PRISMA-P Checklist

- Eligibility Criteria

- Register your Protocol

- Other Resources

- Other Screening Tools

- Grey Literature Searching

- Citation Searching

- Data Extraction Tools

- Minimize Bias

- Synthesis & Meta-Analysis

- Publishing your Systematic Review

Tools for Critical Appraisal of Studies

“The purpose of critical appraisal is to determine the scientific merit of a research report and its applicability to clinical decision making.” 1 Conducting a critical appraisal of a study is imperative to any well executed evidence review, but the process can be time consuming and difficult. 2 The critical appraisal process requires “a methodological approach coupled with the right tools and skills to match these methods is essential for finding meaningful results.” 3 In short, it is a method of differentiating good research from bad research.

Critical Appraisal by Study Design (featured tools)

- Non-RCTs or Observational Studies

- Diagnostic Accuracy

- Animal Studies

- Qualitative Research

- Tool Repository

- AMSTAR 2 The original AMSTAR was developed to assess the risk of bias in systematic reviews that included only randomized controlled trials. AMSTAR 2 was published in 2017 and allows researchers to “identify high quality systematic reviews, including those based on non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions.” 4 more... less... AMSTAR 2 (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews)

- ROBIS ROBIS is a tool designed specifically to assess the risk of bias in systematic reviews. “The tool is completed in three phases: (1) assess relevance(optional), (2) identify concerns with the review process, and (3) judge risk of bias in the review. Signaling questions are included to help assess specific concerns about potential biases with the review.” 5 more... less... ROBIS (Risk of Bias in Systematic Reviews)

- BMJ Framework for Assessing Systematic Reviews This framework provides a checklist that is used to evaluate the quality of a systematic review.

- CASP Checklist for Systematic Reviews This CASP checklist is not a scoring system, but rather a method of appraising systematic reviews by considering: 1. Are the results of the study valid? 2. What are the results? 3. Will the results help locally? more... less... CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme)

- CEBM Systematic Reviews Critical Appraisal Sheet The CEBM’s critical appraisal sheets are designed to help you appraise the reliability, importance, and applicability of clinical evidence. more... less... CEBM (Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine)

- JBI Critical Appraisal Tools, Checklist for Systematic Reviews JBI Critical Appraisal Tools help you assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the extent to which study has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis.

- NHLBI Study Quality Assessment of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses The NHLBI’s quality assessment tools were designed to assist reviewers in focusing on concepts that are key for critical appraisal of the internal validity of a study. more... less... NHLBI (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute)

- RoB 2 RoB 2 “provides a framework for assessing the risk of bias in a single estimate of an intervention effect reported from a randomized trial,” rather than the entire trial. 6 more... less... RoB 2 (revised tool to assess Risk of Bias in randomized trials)

- CASP Randomised Controlled Trials Checklist This CASP checklist considers various aspects of an RCT that require critical appraisal: 1. Is the basic study design valid for a randomized controlled trial? 2. Was the study methodologically sound? 3. What are the results? 4. Will the results help locally? more... less... CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme)

- CONSORT Statement The CONSORT checklist includes 25 items to determine the quality of randomized controlled trials. “Critical appraisal of the quality of clinical trials is possible only if the design, conduct, and analysis of RCTs are thoroughly and accurately described in the report.” 7 more... less... CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials)

- NHLBI Study Quality Assessment of Controlled Intervention Studies The NHLBI’s quality assessment tools were designed to assist reviewers in focusing on concepts that are key for critical appraisal of the internal validity of a study. more... less... NHLBI (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute)

- JBI Critical Appraisal Tools Checklist for Randomized Controlled Trials JBI Critical Appraisal Tools help you assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the extent to which study has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis.

- ROBINS-I ROBINS-I is a “tool for evaluating risk of bias in estimates of the comparative effectiveness… of interventions from studies that did not use randomization to allocate units… to comparison groups.” 8 more... less... ROBINS-I (Risk Of Bias in Non-randomized Studies – of Interventions)

- NOS This tool is used primarily to evaluate and appraise case-control or cohort studies. more... less... NOS (Newcastle-Ottawa Scale)

- AXIS Cross-sectional studies are frequently used as an evidence base for diagnostic testing, risk factors for disease, and prevalence studies. “The AXIS tool focuses mainly on the presented [study] methods and results.” 9 more... less... AXIS (Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies)

- NHLBI Study Quality Assessment Tools for Non-Randomized Studies The NHLBI’s quality assessment tools were designed to assist reviewers in focusing on concepts that are key for critical appraisal of the internal validity of a study. • Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies • Quality Assessment of Case-Control Studies • Quality Assessment Tool for Before-After (Pre-Post) Studies With No Control Group • Quality Assessment Tool for Case Series Studies more... less... NHLBI (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute)

- Case Series Studies Quality Appraisal Checklist Developed by the Institute of Health Economics (Canada), the checklist is comprised of 20 questions to assess “the robustness of the evidence of uncontrolled, [case series] studies.” 10

- Methodological Quality and Synthesis of Case Series and Case Reports In this paper, Dr. Murad and colleagues “present a framework for appraisal, synthesis and application of evidence derived from case reports and case series.” 11

- MINORS The MINORS instrument contains 12 items and was developed for evaluating the quality of observational or non-randomized studies. 12 This tool may be of particular interest to researchers who would like to critically appraise surgical studies. more... less... MINORS (Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies)

- JBI Critical Appraisal Tools for Non-Randomized Trials JBI Critical Appraisal Tools help you assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the extent to which study has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis. • Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies • Checklist for Case Control Studies • Checklist for Case Reports • Checklist for Case Series • Checklist for Cohort Studies

- QUADAS-2 The QUADAS-2 tool “is designed to assess the quality of primary diagnostic accuracy studies… [it] consists of 4 key domains that discuss patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow of patients through the study and timing of the index tests and reference standard.” 13 more... less... QUADAS-2 (a revised tool for the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies)

- JBI Critical Appraisal Tools Checklist for Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies JBI Critical Appraisal Tools help you assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the extent to which study has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis.

- STARD 2015 The authors of the standards note that “[e]ssential elements of [diagnostic accuracy] study methods are often poorly described and sometimes completely omitted, making both critical appraisal and replication difficult, if not impossible.”10 The Standards for the Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies was developed “to help… improve completeness and transparency in reporting of diagnostic accuracy studies.” 14 more... less... STARD 2015 (Standards for the Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies)

- CASP Diagnostic Study Checklist This CASP checklist considers various aspects of diagnostic test studies including: 1. Are the results of the study valid? 2. What were the results? 3. Will the results help locally? more... less... CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme)

- CEBM Diagnostic Critical Appraisal Sheet The CEBM’s critical appraisal sheets are designed to help you appraise the reliability, importance, and applicability of clinical evidence. more... less... CEBM (Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine)

- SYRCLE’s RoB “[I]mplementation of [SYRCLE’s RoB tool] will facilitate and improve critical appraisal of evidence from animal studies. This may… enhance the efficiency of translating animal research into clinical practice and increase awareness of the necessity of improving the methodological quality of animal studies.” 15 more... less... SYRCLE’s RoB (SYstematic Review Center for Laboratory animal Experimentation’s Risk of Bias)

- ARRIVE 2.0 “The [ARRIVE 2.0] guidelines are a checklist of information to include in a manuscript to ensure that publications [on in vivo animal studies] contain enough information to add to the knowledge base.” 16 more... less... ARRIVE 2.0 (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments)

- Critical Appraisal of Studies Using Laboratory Animal Models This article provides “an approach to critically appraising papers based on the results of laboratory animal experiments,” and discusses various “bias domains” in the literature that critical appraisal can identify. 17

- CEBM Critical Appraisal of Qualitative Studies Sheet The CEBM’s critical appraisal sheets are designed to help you appraise the reliability, importance and applicability of clinical evidence. more... less... CEBM (Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine)

- CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist This CASP checklist considers various aspects of qualitative research studies including: 1. Are the results of the study valid? 2. What were the results? 3. Will the results help locally? more... less... CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme)

- Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias Tool Repository Created by librarians at Duke University, this extensive listing contains over 100 commonly used risk of bias tools that may be sorted by study type.

- Latitudes Network A library of risk of bias tools for use in evidence syntheses that provides selection help and training videos.

References & Recommended Reading

1. Kolaski, K., Logan, L. R., & Ioannidis, J. P. (2024). Guidance to best tools and practices for systematic reviews . British Journal of Pharmacology , 181 (1), 180-210

2. Portney LG. Foundations of clinical research : applications to evidence-based practice. Fourth edition. ed. Philadelphia: F A Davis; 2020.

3. Fowkes FG, Fulton PM. Critical appraisal of published research: introductory guidelines. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 1991;302(6785):1136-1140.

4. Singh S. Critical appraisal skills programme. Journal of Pharmacology and Pharmacotherapeutics. 2013;4(1):76-77.

5. Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2017;358:j4008.

6. Whiting P, Savovic J, Higgins JPT, et al. ROBIS: A new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2016;69:225-234.

7. Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2019;366:l4898.

8. Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. CONSORT 2010 Explanation and Elaboration: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2010;63(8):e1-37.

9. Sterne JA, Hernan MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2016;355:i4919.

10. Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, Dean RS. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ open. 2016;6(12):e011458.

11. Guo B, Moga C, Harstall C, Schopflocher D. A principal component analysis is conducted for a case series quality appraisal checklist. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2016;69:199-207.e192.

12. Murad MH, Sultan S, Haffar S, Bazerbachi F. Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ evidence-based medicine. 2018;23(2):60-63.

13. Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ journal of surgery. 2003;73(9):712-716.

14. Whiting PF, Rutjes AWS, Westwood ME, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Annals of internal medicine. 2011;155(8):529-536.

15. Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, et al. STARD 2015: an updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2015;351:h5527.

16. Hooijmans CR, Rovers MM, de Vries RBM, Leenaars M, Ritskes-Hoitinga M, Langendam MW. SYRCLE's risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC medical research methodology. 2014;14:43.

17. Percie du Sert N, Ahluwalia A, Alam S, et al. Reporting animal research: Explanation and elaboration for the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0. PLoS biology. 2020;18(7):e3000411.

18. O'Connor AM, Sargeant JM. Critical appraisal of studies using laboratory animal models. ILAR journal. 2014;55(3):405-417.

- << Previous: Minimize Bias

- Next: GRADE >>

- Last Updated: May 10, 2024 7:59 AM

- URL: https://libraryguides.mayo.edu/systematicreviewprocess

- Open access

- Published: 01 August 2019

A step by step guide for conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis with simulation data

- Gehad Mohamed Tawfik 1 , 2 ,

- Kadek Agus Surya Dila 2 , 3 ,

- Muawia Yousif Fadlelmola Mohamed 2 , 4 ,

- Dao Ngoc Hien Tam 2 , 5 ,

- Nguyen Dang Kien 2 , 6 ,

- Ali Mahmoud Ahmed 2 , 7 &

- Nguyen Tien Huy 8 , 9 , 10

Tropical Medicine and Health volume 47 , Article number: 46 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

801k Accesses

295 Citations

93 Altmetric

Metrics details

The massive abundance of studies relating to tropical medicine and health has increased strikingly over the last few decades. In the field of tropical medicine and health, a well-conducted systematic review and meta-analysis (SR/MA) is considered a feasible solution for keeping clinicians abreast of current evidence-based medicine. Understanding of SR/MA steps is of paramount importance for its conduction. It is not easy to be done as there are obstacles that could face the researcher. To solve those hindrances, this methodology study aimed to provide a step-by-step approach mainly for beginners and junior researchers, in the field of tropical medicine and other health care fields, on how to properly conduct a SR/MA, in which all the steps here depicts our experience and expertise combined with the already well-known and accepted international guidance.

We suggest that all steps of SR/MA should be done independently by 2–3 reviewers’ discussion, to ensure data quality and accuracy.

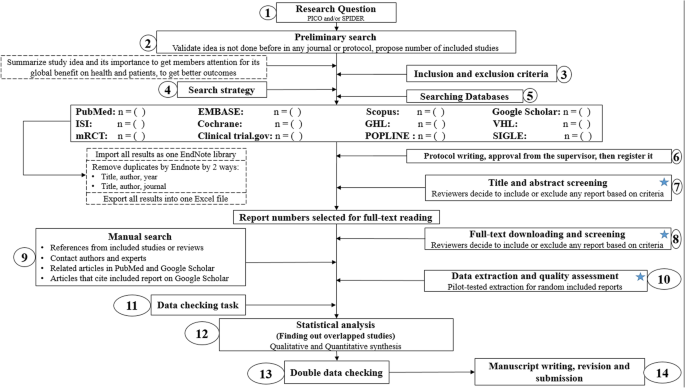

SR/MA steps include the development of research question, forming criteria, search strategy, searching databases, protocol registration, title, abstract, full-text screening, manual searching, extracting data, quality assessment, data checking, statistical analysis, double data checking, and manuscript writing.

Introduction

The amount of studies published in the biomedical literature, especially tropical medicine and health, has increased strikingly over the last few decades. This massive abundance of literature makes clinical medicine increasingly complex, and knowledge from various researches is often needed to inform a particular clinical decision. However, available studies are often heterogeneous with regard to their design, operational quality, and subjects under study and may handle the research question in a different way, which adds to the complexity of evidence and conclusion synthesis [ 1 ].

Systematic review and meta-analyses (SR/MAs) have a high level of evidence as represented by the evidence-based pyramid. Therefore, a well-conducted SR/MA is considered a feasible solution in keeping health clinicians ahead regarding contemporary evidence-based medicine.

Differing from a systematic review, unsystematic narrative review tends to be descriptive, in which the authors select frequently articles based on their point of view which leads to its poor quality. A systematic review, on the other hand, is defined as a review using a systematic method to summarize evidence on questions with a detailed and comprehensive plan of study. Furthermore, despite the increasing guidelines for effectively conducting a systematic review, we found that basic steps often start from framing question, then identifying relevant work which consists of criteria development and search for articles, appraise the quality of included studies, summarize the evidence, and interpret the results [ 2 , 3 ]. However, those simple steps are not easy to be reached in reality. There are many troubles that a researcher could be struggled with which has no detailed indication.

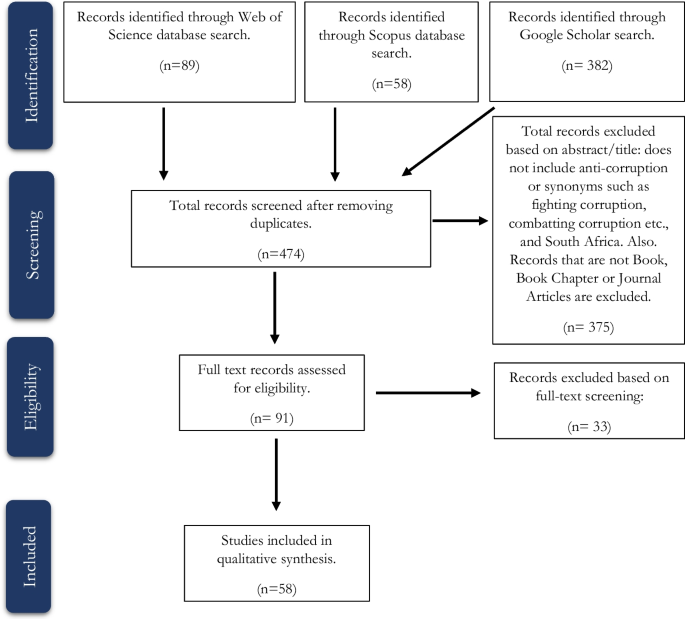

Conducting a SR/MA in tropical medicine and health may be difficult especially for young researchers; therefore, understanding of its essential steps is crucial. It is not easy to be done as there are obstacles that could face the researcher. To solve those hindrances, we recommend a flow diagram (Fig. 1 ) which illustrates a detailed and step-by-step the stages for SR/MA studies. This methodology study aimed to provide a step-by-step approach mainly for beginners and junior researchers, in the field of tropical medicine and other health care fields, on how to properly and succinctly conduct a SR/MA; all the steps here depicts our experience and expertise combined with the already well known and accepted international guidance.

Detailed flow diagram guideline for systematic review and meta-analysis steps. Note : Star icon refers to “2–3 reviewers screen independently”

Methods and results

Detailed steps for conducting any systematic review and meta-analysis.

We searched the methods reported in published SR/MA in tropical medicine and other healthcare fields besides the published guidelines like Cochrane guidelines {Higgins, 2011 #7} [ 4 ] to collect the best low-bias method for each step of SR/MA conduction steps. Furthermore, we used guidelines that we apply in studies for all SR/MA steps. We combined these methods in order to conclude and conduct a detailed flow diagram that shows the SR/MA steps how being conducted.

Any SR/MA must follow the widely accepted Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis statement (PRISMA checklist 2009) (Additional file 5 : Table S1) [ 5 ].

We proposed our methods according to a valid explanatory simulation example choosing the topic of “evaluating safety of Ebola vaccine,” as it is known that Ebola is a very rare tropical disease but fatal. All the explained methods feature the standards followed internationally, with our compiled experience in the conduct of SR beside it, which we think proved some validity. This is a SR under conduct by a couple of researchers teaming in a research group, moreover, as the outbreak of Ebola which took place (2013–2016) in Africa resulted in a significant mortality and morbidity. Furthermore, since there are many published and ongoing trials assessing the safety of Ebola vaccines, we thought this would provide a great opportunity to tackle this hotly debated issue. Moreover, Ebola started to fire again and new fatal outbreak appeared in the Democratic Republic of Congo since August 2018, which caused infection to more than 1000 people according to the World Health Organization, and 629 people have been killed till now. Hence, it is considered the second worst Ebola outbreak, after the first one in West Africa in 2014 , which infected more than 26,000 and killed about 11,300 people along outbreak course.

Research question and objectives

Like other study designs, the research question of SR/MA should be feasible, interesting, novel, ethical, and relevant. Therefore, a clear, logical, and well-defined research question should be formulated. Usually, two common tools are used: PICO or SPIDER. PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) is used mostly in quantitative evidence synthesis. Authors demonstrated that PICO holds more sensitivity than the more specific SPIDER approach [ 6 ]. SPIDER (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type) was proposed as a method for qualitative and mixed methods search.

We here recommend a combined approach of using either one or both the SPIDER and PICO tools to retrieve a comprehensive search depending on time and resources limitations. When we apply this to our assumed research topic, being of qualitative nature, the use of SPIDER approach is more valid.

PICO is usually used for systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trial study. For the observational study (without intervention or comparator), in many tropical and epidemiological questions, it is usually enough to use P (Patient) and O (outcome) only to formulate a research question. We must indicate clearly the population (P), then intervention (I) or exposure. Next, it is necessary to compare (C) the indicated intervention with other interventions, i.e., placebo. Finally, we need to clarify which are our relevant outcomes.

To facilitate comprehension, we choose the Ebola virus disease (EVD) as an example. Currently, the vaccine for EVD is being developed and under phase I, II, and III clinical trials; we want to know whether this vaccine is safe and can induce sufficient immunogenicity to the subjects.

An example of a research question for SR/MA based on PICO for this issue is as follows: How is the safety and immunogenicity of Ebola vaccine in human? (P: healthy subjects (human), I: vaccination, C: placebo, O: safety or adverse effects)

Preliminary research and idea validation

We recommend a preliminary search to identify relevant articles, ensure the validity of the proposed idea, avoid duplication of previously addressed questions, and assure that we have enough articles for conducting its analysis. Moreover, themes should focus on relevant and important health-care issues, consider global needs and values, reflect the current science, and be consistent with the adopted review methods. Gaining familiarity with a deep understanding of the study field through relevant videos and discussions is of paramount importance for better retrieval of results. If we ignore this step, our study could be canceled whenever we find out a similar study published before. This means we are wasting our time to deal with a problem that has been tackled for a long time.

To do this, we can start by doing a simple search in PubMed or Google Scholar with search terms Ebola AND vaccine. While doing this step, we identify a systematic review and meta-analysis of determinant factors influencing antibody response from vaccination of Ebola vaccine in non-human primate and human [ 7 ], which is a relevant paper to read to get a deeper insight and identify gaps for better formulation of our research question or purpose. We can still conduct systematic review and meta-analysis of Ebola vaccine because we evaluate safety as a different outcome and different population (only human).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligibility criteria are based on the PICO approach, study design, and date. Exclusion criteria mostly are unrelated, duplicated, unavailable full texts, or abstract-only papers. These exclusions should be stated in advance to refrain the researcher from bias. The inclusion criteria would be articles with the target patients, investigated interventions, or the comparison between two studied interventions. Briefly, it would be articles which contain information answering our research question. But the most important is that it should be clear and sufficient information, including positive or negative, to answer the question.

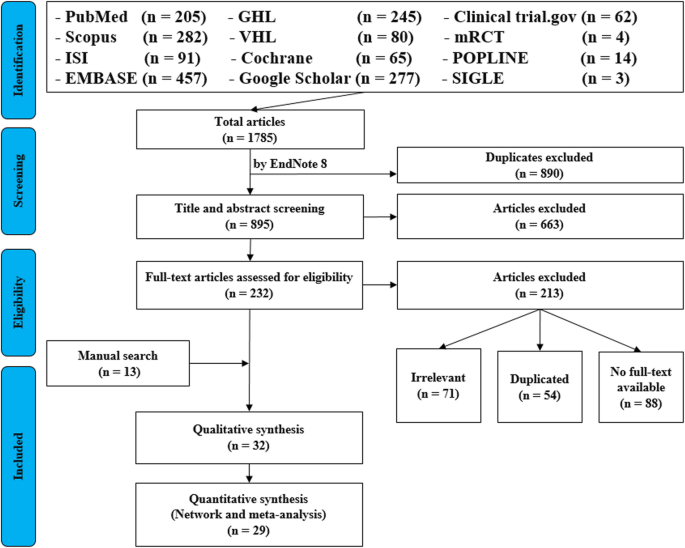

For the topic we have chosen, we can make inclusion criteria: (1) any clinical trial evaluating the safety of Ebola vaccine and (2) no restriction regarding country, patient age, race, gender, publication language, and date. Exclusion criteria are as follows: (1) study of Ebola vaccine in non-human subjects or in vitro studies; (2) study with data not reliably extracted, duplicate, or overlapping data; (3) abstract-only papers as preceding papers, conference, editorial, and author response theses and books; (4) articles without available full text available; and (5) case reports, case series, and systematic review studies. The PRISMA flow diagram template that is used in SR/MA studies can be found in Fig. 2 .

PRISMA flow diagram of studies’ screening and selection

Search strategy

A standard search strategy is used in PubMed, then later it is modified according to each specific database to get the best relevant results. The basic search strategy is built based on the research question formulation (i.e., PICO or PICOS). Search strategies are constructed to include free-text terms (e.g., in the title and abstract) and any appropriate subject indexing (e.g., MeSH) expected to retrieve eligible studies, with the help of an expert in the review topic field or an information specialist. Additionally, we advise not to use terms for the Outcomes as their inclusion might hinder the database being searched to retrieve eligible studies because the used outcome is not mentioned obviously in the articles.

The improvement of the search term is made while doing a trial search and looking for another relevant term within each concept from retrieved papers. To search for a clinical trial, we can use these descriptors in PubMed: “clinical trial”[Publication Type] OR “clinical trials as topic”[MeSH terms] OR “clinical trial”[All Fields]. After some rounds of trial and refinement of search term, we formulate the final search term for PubMed as follows: (ebola OR ebola virus OR ebola virus disease OR EVD) AND (vaccine OR vaccination OR vaccinated OR immunization) AND (“clinical trial”[Publication Type] OR “clinical trials as topic”[MeSH Terms] OR “clinical trial”[All Fields]). Because the study for this topic is limited, we do not include outcome term (safety and immunogenicity) in the search term to capture more studies.

Search databases, import all results to a library, and exporting to an excel sheet

According to the AMSTAR guidelines, at least two databases have to be searched in the SR/MA [ 8 ], but as you increase the number of searched databases, you get much yield and more accurate and comprehensive results. The ordering of the databases depends mostly on the review questions; being in a study of clinical trials, you will rely mostly on Cochrane, mRCTs, or International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP). Here, we propose 12 databases (PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, EMBASE, GHL, VHL, Cochrane, Google Scholar, Clinical trials.gov , mRCTs, POPLINE, and SIGLE), which help to cover almost all published articles in tropical medicine and other health-related fields. Among those databases, POPLINE focuses on reproductive health. Researchers should consider to choose relevant database according to the research topic. Some databases do not support the use of Boolean or quotation; otherwise, there are some databases that have special searching way. Therefore, we need to modify the initial search terms for each database to get appreciated results; therefore, manipulation guides for each online database searches are presented in Additional file 5 : Table S2. The detailed search strategy for each database is found in Additional file 5 : Table S3. The search term that we created in PubMed needs customization based on a specific characteristic of the database. An example for Google Scholar advanced search for our topic is as follows:

With all of the words: ebola virus

With at least one of the words: vaccine vaccination vaccinated immunization

Where my words occur: in the title of the article

With all of the words: EVD

Finally, all records are collected into one Endnote library in order to delete duplicates and then to it export into an excel sheet. Using remove duplicating function with two options is mandatory. All references which have (1) the same title and author, and published in the same year, and (2) the same title and author, and published in the same journal, would be deleted. References remaining after this step should be exported to an excel file with essential information for screening. These could be the authors’ names, publication year, journal, DOI, URL link, and abstract.

Protocol writing and registration

Protocol registration at an early stage guarantees transparency in the research process and protects from duplication problems. Besides, it is considered a documented proof of team plan of action, research question, eligibility criteria, intervention/exposure, quality assessment, and pre-analysis plan. It is recommended that researchers send it to the principal investigator (PI) to revise it, then upload it to registry sites. There are many registry sites available for SR/MA like those proposed by Cochrane and Campbell collaborations; however, we recommend registering the protocol into PROSPERO as it is easier. The layout of a protocol template, according to PROSPERO, can be found in Additional file 5 : File S1.

Title and abstract screening

Decisions to select retrieved articles for further assessment are based on eligibility criteria, to minimize the chance of including non-relevant articles. According to the Cochrane guidance, two reviewers are a must to do this step, but as for beginners and junior researchers, this might be tiresome; thus, we propose based on our experience that at least three reviewers should work independently to reduce the chance of error, particularly in teams with a large number of authors to add more scrutiny and ensure proper conduct. Mostly, the quality with three reviewers would be better than two, as two only would have different opinions from each other, so they cannot decide, while the third opinion is crucial. And here are some examples of systematic reviews which we conducted following the same strategy (by a different group of researchers in our research group) and published successfully, and they feature relevant ideas to tropical medicine and disease [ 9 , 10 , 11 ].

In this step, duplications will be removed manually whenever the reviewers find them out. When there is a doubt about an article decision, the team should be inclusive rather than exclusive, until the main leader or PI makes a decision after discussion and consensus. All excluded records should be given exclusion reasons.

Full text downloading and screening

Many search engines provide links for free to access full-text articles. In case not found, we can search in some research websites as ResearchGate, which offer an option of direct full-text request from authors. Additionally, exploring archives of wanted journals, or contacting PI to purchase it if available. Similarly, 2–3 reviewers work independently to decide about included full texts according to eligibility criteria, with reporting exclusion reasons of articles. In case any disagreement has occurred, the final decision has to be made by discussion.

Manual search

One has to exhaust all possibilities to reduce bias by performing an explicit hand-searching for retrieval of reports that may have been dropped from first search [ 12 ]. We apply five methods to make manual searching: searching references from included studies/reviews, contacting authors and experts, and looking at related articles/cited articles in PubMed and Google Scholar.

We describe here three consecutive methods to increase and refine the yield of manual searching: firstly, searching reference lists of included articles; secondly, performing what is known as citation tracking in which the reviewers track all the articles that cite each one of the included articles, and this might involve electronic searching of databases; and thirdly, similar to the citation tracking, we follow all “related to” or “similar” articles. Each of the abovementioned methods can be performed by 2–3 independent reviewers, and all the possible relevant article must undergo further scrutiny against the inclusion criteria, after following the same records yielded from electronic databases, i.e., title/abstract and full-text screening.