Toyota Information System & Toyota ERP Case Study

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Toyota ERP Case Study: Introduction

Research objectives, company overview and background, role of toyota information systems in business model & strategy, toyota information system, toyota erp system case study: conclusion.

The Company chosen for analysis is a manufacturing plant located in Kentucky, Georgetown known as Toyota Motor Manufacturing Kentucky. The organization is appropriate for analysis owing to its use of Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) as a mechanism for continuous improvement.

Prior to the use of this information System (IS), the organization struggled with disjointed information flow, slow decision making, inventory wastage and low productivity. It was imperative to employ an information system that would allow the plant to meet its underlying strategies as well as enhance the value in production.

The key research objective is to determine how an organization can use Enterprise Resource Planning, as an information system in order to enhance productivity. The report will realize this key objective through the analysis of a car manufacturer.

Other minor objectives include: determining the necessary factors needed to make ERP work, to identify problems that can be solved using the ERP system, and how businesses tie their strategies with the adoption of technology.

The Toyota, Kentucky manufacturing plant, is a subsidiary of the parent firm based in Tokyo. For purposes of this analysis, focus will go to the processes and operations in this plant. The production section has three key divisions, which include body assembly, paint and final assembly. Each of the divisions is further split into the smaller units, usually identified as shops.

The first is the press shop, which presses inner, and outer parts of the body together. The second is the body shop where the panels from the press shop are pieced together to create body shells. The later two shops belong to the body assembly divisions. Thereafter, the commodity enters a paint shop where it goes through a series of booths or dips designed to protect it from corrosion and abrasion. It also painted to make it strong.

This section also entails installation of sound pads that reduce noise as the car travels. The final assembly area consists of a series of trim and chassis equipments. In the trim section, machines or people fit interior parts of the body into the incomplete vehicle.

Thereafter, the car enters into the chassis section where machines fit it with external components. The completed body then enters the quality control section. Members of each of these shops think of each other as teams, so they do their best in their sections in order to prevent problems in other parts.

Other than manufacturing, the company also has a procurement and supply chain function that handles all the logistical issues in the organization. Since the firm implemented a flat structure, the assembly group is responsible for this aspect. It has a quality control department that inspects vehicles when completed.

The plant has an accounting function which top management handles. Plant managers also handle human resource issues such as hiring, promotion and training of employees. The plant outsources the marketing and distribution of its products to another subsidiary of Toyota so as to ensure efficiency in the production of cars.

The IT department is rather amorphous because it is responsible for numerous activities in the plant. First, it ensures that the robots carrying out a lot of work in the plant are in order. It also handles all the data that relate to the company; this may range from financial to material-based information. Additionally, the firm empowers members of the IT team to make crucial decisions at work.

They may halt an assembly line if they identify a flaw. The department manages Toyota’s information through information systems, data infrastructure and computer hardware. They handle almost all types of information. Employees in the group are answerable to a departmental manager.

Toyota Kentucky has a high degree of automation, and this necessitates information networking and flow. For instance, the company needs to plan how it can acquire material for production through order processing. Information Systems facilitate performance of this function seamlessly and accurately.

During the production process, the organization needs to carry out planning, automation, quality management, operation monitoring, and many others. Information Systems assist the organization to facilitate the interaction of all these components before car production. Seamless interlinking of all these production processes necessitates the existence of a data record.

For instance, a new car has a unique number that its components have. This will serve as the identifier during the registration process. All the stages involved, such as painting and trimming, will work towards development of a car. Additionally, some parts of the automobile need to be scanned in order to ascertain that they are in working order. Aspects such as torque, density weight must all be assessed and recorded.

Information Systems facilitate this fast transition in production processes by coordinating information sources at all stages. They also assist individuals in identifying where current and future bottlenecks will arise, thus facilitating their resolution. Data analysis through the information system can enhance production processes significantly.

The company has a range of information systems that it uses to manage its operations. It has a customer relationship management IS supplied by Oracle, and clients use it to enhance customer interactions. Furthermore, the firm has several systems for the management of the production process, such as the plant scheduling system as well as the plant monitoring system (assembly line control system).

The latter aspects are crucial for the implementation of the just – in –time model that people associate with Toyota. Additionally, the company utilizes information systems to correct waste and ascertain that customers do not have to wait long for the completion of their car. Lean production is yet another principle that made Toyota famous and ERPs are effective in achieving this objective.

The IS system is an Enterprise Resource Planning system. It facilitates information flow between the various functions in a firm. Some of the functions can include manufacturing, finance and inventory management (Vilpola, 2008). Usually any ERP system needs to have four key traits.

It should operate on real time in order to eliminate the need for frequent updates. It should also have a database that can support all the applications within an organization. One should get a consistent look of the ERP regardless of the nature of model used. Additionally, the IT team within a certain organization should not have to do data integration in order to install the system.

Systems integrators normally configure ERP systems within an organization. They have adequate knowledge about the necessary vendor solutions needed by the implementing firm and the equipments they require in order to do so. When an organization possesses an Enterprise Resource Planning IS, then it can connect real time data and transactions through various channels.

Sometimes the latter functions can be done through direct integration of plant floor equipments. Alternatively, it may occur through database integration or enterprise transaction modules. Sometimes a company may choose to use custom integrated solutions where it alters the server or workstations when necessary.

ERP systems have the potential to alter how a company does business only if the processes covered in the system match those in an organization. Each process should also be highly effective, and ERP users should understand the automated systems.

The ERP system at Toyota consisted of a financial management component. This financial module is responsible for the management of fixed assets. It also handles the billing and accounts paid or received within the plant. Additionally, general ledger requirements and budgetary functions are also in the package. Tax reporting, budgeting and management of cash flow are part of this system, as well (Abilla, 2006).

Business intelligence is a critical part of Toyota’s operations in the Kentucky plant. This is part of the ERP package in the organization, and it allows users to analyze or share data across the enterprise in a centralized manner. The firm achieves this function through the use of automated analytical and reporting tools. It also has dashboards or control panels, in which top management monitors business performance.

Supply chain management is also a vital part of the system and involves procurement of materials for the vehicle, fulfillment of orders, planning and scheduling of the materials. This module possesses some sub modules that include procurement management, inventory management and product scheduling.

Human resource management is a vital component of the ERP system in the Kentucky Toyota Plant. The plant ensures that all employee-related issues run smoothly through the management of all human resource issues in hiring and retaining workers. The ERP solution handles payroll; it does time tracking, benefits, and even performance management.

Manufacturing operations are also part of the organization’s ERP system. This is the heart of the firm’s endeavor. It does product configuration through the ERP component. Additionally, it carries out material requirements planning, production scheduling as well as forecasting.

Perhaps one of the key components of the ERP system that makes the package work successfully for the organization is the fact that it is ingrates easily. Integration allows information flow in the entire plant, and this facilitates business intelligence.

Technologies used: hardware and software

No ERP system can be successful without investment in hardware technologies; therefore, the organization needed to invest in two types of computers: servers and workstations. Currently, the company uses high throughput disk drives in its servers. The network card used in the servers has gigabit speed, and the ram is twice as much as the recommended amount by the ERP vendor.

This ensures that performance is satisfactory on all levels. Additionally, the company invested in reasonable workstations. Many organizations that have failed in ERP implementation have ignored this aspect. Toyota Kentucky chose to invest in its workstations through the use of a high-memory RAM. It also has video controllers on its computers and uses the latest version of Microsoft.

Aside from workstations and servers, the company also has a power backup system for the ERP system. Power failures have been occurring in the USA, of late. In order to protect the integrity of the material in the ERP system, the organization often ensures that it connects the workstations, switches, servers, external drives and the laptops used in the ERP to strong UPS systems.

In addition to hardware systems, the company has a software solution known as SAP. The latter is an acronym for Systems, Applications and Products. Toyota selected this software vendor because it has plenty of experience in the field. Additionally, high integration exists in the software thus allowing the manufacturing plant to incorporate as many of its business functions as it wants (O’Brien, 2011).

The company also selected SAP because it would save on costs that emanate from integrating different modules into the ERP. Choosing SAP enabled the firm to take advantage of business support services offered by the vendor.

Targeted end users

The end users of the ERP systems in Toyota range from ordinary workers, mid level and top level management. Top level managers carry out the business intelligent aspect as well as the analytics process of the manufacturing plant. They use information from the ERP system to forecast as well as determine other strategic components that must be endorsed to make the firm successful.

For instance, they will carry out production planning through the use of business analytics inherent in the ERP system. They are also responsible for the creation of new processes when the firm implements the Information System. Mid level managers, on the other hand, are responsible for the implementation of these new processes (Yusuf et. al., 2004).

This ERP system also targets line employees and other ordinary staff who have no senior title. They are the ones who use their work stations to input data. They also rely on the ERP system for feedback concerning certain aspects of work. These individuals make the ERP a success by incorporating it into their daily activities. In the event of an ERP upgrade, all line workers will need to participate in their configuration of the system.

How the Information System relates to the company strategy

Toyota is famous for its emphasis on lean production. Enterprise Resource Planning has been at the heart of meeting this company’s strategy. Currently, the organization has firm control over its processes and practices. This enables the firm to add value to customers as well as to eliminate waste continually.

Toyota often examined the activities that add value to the company and reduces the non value adding activities through its ERP system. The firm realizes that lean production is not a one-day event; it is a continual process that the organization must work on throughout production.

Lean production centers on five key principles: pursuit of perfection, customer pull, value steam mapping, uninterrupted flow and value definition. Toyota has been able to achieve all these principles thanks to the ERP system. It has reduced down time as well as delays, scrap, reworking and inefficient inventory handling through business intelligence.

What would happen if the technologies were not available

If the technologies were not available, it is likely that the business would have disjointed information systems that are not just inconsistent and inaccurate, but are also difficult to access. This implies that the organization would be making decisions lengthily and would not analyze performance effectively.

For instance, the company would need to determine the nature of a car component delivery as well as the quality metrics that apply to the car using an incredibly complicated process. Additionally, the technologies are modern, so they are compatible with most modern technologies in production and computing. Without them, the organization would have to encounter numerous hurdles in data recording.

Additionally, the ERP Information System has ensured that various sections in the Toyota plant work together. If the company had not implemented the system, then chances are that the organization would still have isolated functions.

The absence of these technologies would have left Toyota susceptibility to manual manipulation as the older systems were susceptible to this. Furthermore, manufacturing systems between different plants would not be able to communicate. Prior to ERP, it was hard for the company to determine whether its seat manufacturers or equipment manufactures had adequate stock for a certain make of product.

Consequently, ERP allowed communication between different manufacturing systems thus enhancing productivity in the plant. Monitoring the company’s finances would have been extremely hard without the ERP technologies. In the past, the organization controlled its financial transactions using an old accounting legacy system.

However, this created difficulties in interfacing with other databases thus preventing the company from controlling its financial transactions adequately. It was difficult to predict and thus minimize how much money the company spent on certain partners or suppliers.

How the IS benefited the business

Toyota Kentucky has benefitted enormously from the use of ERP. The most outstanding benefit is the company has gained real time capabilities ( Itech, 2012). It has enabled workers to see what is taking place inside their organization in real time. The automaker often deals with large and high volume processes. Consequently, it is invaluable to have a system that allows them to assess situations easily.

Because of this advantage, now Toyota does not suffer from time wastage that stems from file transfers. Workflow has improved and so has efficiency within the firm. It also does not face difficulties in inventory shortages since all the company requires is to use its ERP system. This benefit comes from the tracking, planning and forecasting capabilities.

The seamlessness that emanates from the use of this IS system has enabled the manufacturing plant to increase the volume of cars coming from the company. It has also assisted the company in fulfillment of orders as mandated by its partners. Furthermore, the facility reduced production costs and thus passed on the savings to car consumers. The organization hardly faces challenges in billing because of better visibility.

People, organization and technology factors involved

In order to achieve maximum benefit from the ERP system, the company ensured that the ERP software configuration matched the business processes. It also trained all the line, mid and senior level managers to accept change and alter the way they do business. Employees were also taught how to use the ERP equipment.

For the ERP system to work, Toyota needed to commit to timely equipment deliveries, as well as data clean up. The company also needed to manage its relationships effectively especially with regard to computer – based environments.

Training is an imperative part of ERP success in the company. Workers attended workshops and other classes in order to acquire the skills needed to operate the IS effectively. With the right commitment from top level management, the organization is well on its way to achieving its objectives.

Extent to which the IS helped the company to compete in the industry

Successful automakers in the industry always endeavor to produce quality products at a consistent level. Toyota’s internal processes have improved tremendously through the use of ERP. Now the company’s internal processes have led to increased output. The firm competes with other players who may not effectively deliver quality at a level that is as consistent as theirs.

The long term prospects for business success have increased owing to the use of ERP. Top level management can make critical decisions concerning various aspects of business. The ERP system has allowed the company to adopt a long term, strategic approach, and this gives it an edge over its competitors.

In addition to the above, ERP has helped Toyota to become more alert. It has become immensely responsive to its external and internal factors. As a result, the firm can deal with changes more effectively than its competitors.

The key research objective was to determine how an organization can use Enterprise Resource Planning, as an information system, in order to enhance productivity. Through the Toyota case study, it was evident that information synchronization, business intelligence and elimination of redundancy enable companies to achieve high productivity.

Other minor objectives included determining the necessary factors needed to make ERP work; Toyota illustrated that one needs investment in a dependable software program like SAP, servers, as well as workstation hardware.

Problems that can be solved with ERP include inventory challenges, procurement glitches, forecasting as well as assembly line issues. Toyota realized its strategy of lean production through ERP, as well. This made the plant competitive and immensely successful.

Abilla, P. (2006). Information Technology at Toyota . Web.

Itech (2012). Toyota decides to replace business-critical systems with open source business applications . Web.

O’Brien, J. (2011). Management Information Systems (MIS) . New York: McGraw-Hill, Irwin.

Vilpola, H. (2008). A method for improving ERP implementation success by the principles and process of user-centered design. Enterprise Information Systems, 2 (1), 47–76.

Yusuf, Y., Gunasekaran, A. and Abthorpe, M. (2004). Enterprise Information Systems Project Implementation: A Case Study of ERP in Rolls-Royce. International Journal of Production Economics , 87(3), 250-290.

- Change Management, BPR and successful ERP implementation

- Levi Strauss & Co. and the ERP Failure

- Enterprise Resource Planning Benefits and Risks

- Organisational Behaviour Tools

- Organizational Behavior - HR Practices

- The Influence of Emotions on Organizational Change

- Baldrige Performance Excellence Award

- Product Manager in Mexico and the U.S.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2019, June 18). Toyota Information System & Toyota ERP Case Study. https://ivypanda.com/essays/information-system-in-toyota-motor-manufacturing/

"Toyota Information System & Toyota ERP Case Study." IvyPanda , 18 June 2019, ivypanda.com/essays/information-system-in-toyota-motor-manufacturing/.

IvyPanda . (2019) 'Toyota Information System & Toyota ERP Case Study'. 18 June.

IvyPanda . 2019. "Toyota Information System & Toyota ERP Case Study." June 18, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/information-system-in-toyota-motor-manufacturing/.

1. IvyPanda . "Toyota Information System & Toyota ERP Case Study." June 18, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/information-system-in-toyota-motor-manufacturing/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Toyota Information System & Toyota ERP Case Study." June 18, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/information-system-in-toyota-motor-manufacturing/.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

The Contradictions That Drive Toyota’s Success

- Hirotaka Takeuchi,

- Norihiko Shimizu

Stable and paranoid, systematic and experimental, formal and frank: The success of Toyota, a pathbreaking six-year study reveals, is due as much to its ability to embrace contradictions like these as to its manufacturing prowess.

Reprint: R0806F

Toyota has become one of the world’s greatest companies only because it developed the Toyota Production System, right? Wrong, say Takeuchi, Osono, and Shimizu of Hitotsubashi University in Tokyo. Another factor, overlooked until now, is just as important to the company’s success: Toyota’s culture of contradictions.

TPS is a “hard” innovation that allows the company to continuously improve the way it manufactures vehicles. Toyota has also mastered a “soft” innovation that relates to human resource practices and corporate culture. The company succeeds, say the authors, because it deliberately fosters contradictory viewpoints within the organization and challenges employees to find solutions by transcending differences rather than resorting to compromises. This culture generates innovative ideas that Toyota implements to pull ahead of competitors, both incrementally and radically.

The authors’ research reveals six forces that cause contradictions inside Toyota. Three forces of expansion lead the company to change and improve: impossible goals, local customization, and experimentation. Not surprisingly, these forces make the organization more diverse, complicate decision making, and threaten Toyota’s control systems. To prevent the winds of change from blowing down the organization, the company also harnesses three forces of integration: the founders’ values, “up-and-in” people management, and open communication. These forces stabilize the company, help employees make sense of the environment in which they operate, and perpetuate Toyota’s values and culture.

Emulating Toyota isn’t about copying any one practice; it’s about creating a culture. And because the company’s culture of contradictions is centered on humans, who are imperfect, there will always be room for improvement.

No executive needs convincing that Toyota Motor Corporation has become one of the world’s greatest companies because of the Toyota Production System (TPS). The unorthodox manufacturing system enables the Japanese giant to make the planet’s best automobiles at the lowest cost and to develop new products quickly. Not only have Toyota’s rivals such as Chrysler, Daimler, Ford, Honda, and General Motors developed TPS-like systems, organizations such as hospitals and postal services also have adopted its underlying rules, tools, and conventions to become more efficient. An industry of lean-manufacturing experts have extolled the virtues of TPS so often and with so much conviction that managers believe its role in Toyota’s success to be one of the few enduring truths in an otherwise murky world.

- Hirotaka Takeuchi is a professor in the strategy unit of Harvard Business School.

- EO Emi Osono ( [email protected] ) is an associate professor;

- NS and Norihiko Shimizu ( [email protected] ) is a visiting professor at Hitotsubashi University’s Graduate School of International Corporate Strategy in Tokyo. This article is adapted from their book Extreme Toyota: Radical Contradictions That Drive Success at the World’s Best Manufacturer , forthcoming from John Wiley & Sons.

Partner Center

Welcome to the MIT CISR website!

This site uses cookies. Review our Privacy Statement.

Digital in the Driver’s Seat: Accelerating Toyota’s Transformation to Mobility Services

An in-depth description of a firm’s approach to an IT management issue (intended for MBA and executive education)

In 2020 Toyota Motor Corporation (TMC) was the world’s top-selling car manufacturer. Despite this, the company was being driven to excel further in response to changing consumer expectations, technological developments, and new kinds of entrants into the automotive industry. Toyota’s leaders sought to accelerate the company’s culture of incremental innovation and realize a bold new future centered on mobility services. They pursued this by launching Toyota Connected, a new organization with its own decision rights and ways of working and a mandate to create new digital offerings for Toyota. In parallel, a new division within Toyota Motor North America called Connected Technologies facilitated the company-wide diffusion and commercialization of the offerings Toyota Connected created. This case describes what it took to empower the small, independent, agile Toyota Connected and how the entity collaborated with Connected Technologies to design and scale new digital offerings and new ways of working for TMC globally.

Access More Research!

Any registered, logged-in user of the website can read many MIT CISR Working Papers in the webpage from 90 days after publication, plus download a PDF of the publication. Employees of MIT CISR members organizations get access to additional content.

Related Publications

Research Briefing

Digital disruption without organizational upheaval.

Working Paper: Case Study

Digital innovation at toyota motor north america: revamping the role of it.

Designed for Digital: How to Architect Your Business for Sustained Success

About the Authors

Nick van der Meulen, Research Scientist, MIT Center for Information Systems Research (CISR)

John G. Mooney, Professor, Pepperdine Graziadio Business School

Cynthia M. Beath, Professor Emerita, University of Texas and Research Collaborator, MIT CISR

Mit center for information systems research (cisr).

Founded in 1974 and grounded in MIT's tradition of combining academic knowledge and practical purpose, MIT CISR helps executives meet the challenge of leading increasingly digital and data-driven organizations. We work directly with digital leaders, executives, and boards to develop our insights. Our consortium forms a global community that comprises more than seventy-five organizations.

MIT CISR Associate Members

MIT CISR wishes to thank all of our associate members for their support and contributions.

MIT CISR's Mission Expand

MIT CISR helps executives meet the challenge of leading increasingly digital and data-driven organizations. We provide insights on how organizations effectively realize value from approaches such as digital business transformation, data monetization, business ecosystems, and the digital workplace. Founded in 1974 and grounded in MIT’s tradition of combining academic knowledge and practical purpose, we work directly with digital leaders, executives, and boards to develop our insights. Our consortium forms a global community that comprises more than seventy-five organizations.

THE ESSENCE OF JUST-IN-TIME: PRACTICE-IN-USE AT TOYOTA PRODUCTION SYSTEM MANAGED ORGANIZATIONS - How Toyota Turns Workers Into Problem Solvers

by Sarah Jane Johnston, HBS Working Knowledge

| When HBS professor Steven Spear recently released an abstract on problem solving at Toyota, HBS Working Knowledge staffer Sarah Jane Johnston e-mailed off some questions. Spear not only answered the questions, but also asked some of his own—and answered those as well. Sarah Jane Johnston: Why study Toyota? With all the books and articles on Toyota, lean manufacturing, just-in-time, kanban systems, quality systems, etc. that came out in the 1980s and 90s, hasn't the topic been exhausted? Steven Spear: Well, this has been a much-researched area. When Kent Bowen and I first did a literature search, we found nearly 3,000 articles and books had been published on some of the topics you just mentioned. However, there was an apparent discrepancy. There had been this wide, long-standing recognition of Toyota as the premier automobile manufacturer in terms of the unmatched combination of high quality, low cost, short lead-time and flexible production. And Toyota's operating system—the Toyota Production System—had been widely credited for Toyota's sustained leadership in manufacturing performance. Furthermore, Toyota had been remarkably open in letting outsiders study its operations. The American Big Three and many other auto companies had done major benchmarking studies, and they and other companies had tried to implement their own forms of the Toyota Production System. There is the Ford Production System, the Chrysler Operating System, and General Motors went so far as to establish a joint venture with Toyota called NUMMI, approximately fifteen years ago. However, despite Toyota's openness and the genuinely honest efforts by other companies over many years to emulate Toyota, no one had yet matched Toyota in terms of having simultaneously high-quality, low-cost, short lead-time, flexible production over time and broadly based across the system. It was from observations such as these that Kent and I started to form the impression that despite all the attention that had already been paid to Toyota, something critical was being missed. Therefore, we approached people at Toyota to ask what they did that others might have missed. What did they say? To paraphrase one of our contacts, he said, "It's not that we don't want to tell you what TPS is, it's that we can't. We don't have adequate words for it. But, we can show you what TPS is." Over about a four-year period, they showed us how work was actually done in practice in dozens of plants. Kent and I went to Toyota plants and those of suppliers here in the U.S. and in Japan and directly watched literally hundreds of people in a wide variety of roles, functional specialties, and hierarchical levels. I personally was in the field for at least 180 working days during that time and even spent one week at a non-Toyota plant doing assembly work and spent another five months as part of a Toyota team that was trying to teach TPS at a first-tier supplier in Kentucky. What did you discover? We concluded that Toyota has come up with a powerful, broadly applicable answer to a fundamental managerial problem. The products we consume and the services we use are typically not the result of a single person's effort. Rather, they come to us through the collective effort of many people each doing a small part of the larger whole. To a certain extent, this is because of the advantages of specialization that Adam Smith identified in pin manufacturing as long ago as 1776 in The Wealth of Nations . However, it goes beyond the economies of scale that accrue to the specialist, such as skill and equipment focus, setup minimization, etc. The products and services characteristic of our modern economy are far too complex for any one person to understand how they work. It is cognitively overwhelming. Therefore, organizations must have some mechanism for decomposing the whole system into sub-system and component parts, each "cognitively" small or simple enough for individual people to do meaningful work. However, decomposing the complex whole into simpler parts is only part of the challenge. The decomposition must occur in concert with complimentary mechanisms that reintegrate the parts into a meaningful, harmonious whole. This common yet nevertheless challenging problem is obviously evident when we talk about the design of complex technical devices. Automobiles have tens of thousands of mechanical and electronic parts. Software has millions and millions of lines of code. Each system can require scores if not hundreds of person-work-years to be designed. No one person can be responsible for the design of a whole system. No one is either smart enough or long-lived enough to do the design work single handedly. Furthermore, we observe that technical systems are tested repeatedly in prototype forms before being released. Why? Because designers know that no matter how good their initial efforts, they will miss the mark on the first try. There will be something about the design of the overall system structure or architecture, the interfaces that connect components, or the individual components themselves that need redesign. In other words, to some extent the first try will be wrong, and the organization designing a complex system needs to design, test, and improve the system in a way that allows iterative congruence to an acceptable outcome. The same set of conditions that affect groups of people engaged in collaborative product design affect groups of people engaged in the collaborative production and delivery of goods and services. As with complex technical systems, there would be cognitive overload for one person to design, test-in-use, and improve the work systems of factories, hotels, hospitals, or agencies as reflected in (a) the structure of who gets what good, service, or information from whom, (b) the coordinative connections among people so that they can express reliably what they need to do their work and learn what others need from them, and (c) the individual work activities that create intermediate products, services, and information. In essence then, the people who work in an organization that produces something are simultaneously engaged in collaborative production and delivery and are also engaged in a collaborative process of self-reflective design, "prototype testing," and improvement of their own work systems amidst changes in market needs, products, technical processes, and so forth. It is our conclusion that Toyota has developed a set of principles, Rules-in-Use we've called them, that allow organizations to engage in this (self-reflective) design, testing, and improvement so that (nearly) everyone can contribute at or near his or her potential, and when the parts come together the whole is much, much greater than the sum of the parts. What are these rules? We've seen that consistently—across functional roles, products, processes (assembly, equipment maintenance and repair, materials logistics, training, system redesign, administration, etc.), and hierarchical levels (from shop floor to plant manager and above) that in TPS managed organizations the design of nearly all work activities, connections among people, and pathways of connected activities over which products, services, and information take form are specified-in-their-design, tested-with-their-every-use, and improved close in time, place, and person to the occurrence of every problem. That sounds pretty rigorous. It is, but consider what the Toyota people are attempting to accomplish. They are saying before you (or you all) do work, make clear what you expect to happen (by specifying the design), each time you do work, see that what you expected has actually occurred (by testing with each use), and when there is a difference between what had actually happened and what was predicted, solve problems while the information is still fresh. That reminds me of what my high school lab science teacher required. Exactly! This is a system designed for broad based, frequent, rapid, low-cost learning. The "Rules" imply a belief that we may not get the right solution (to work system design) on the first try, but that if we design everything we do as a bona fide experiment, we can more rapidly converge, iteratively, and at lower cost, on the right answer, and, in the process, learn a heck of lot more about the system we are operating. You say in your article that the Toyota system involves a rigorous and methodical problem-solving approach that is made part of everyone's work and is done under the guidance of a teacher. How difficult would it be for companies to develop their own program based on the Toyota model? Your question cuts right to a critical issue. We discussed earlier the basic problem that for complex systems, responsibility for design, testing, and improvement must be distributed broadly. We've observed that Toyota, its best suppliers, and other companies that have learned well from Toyota can confidently distribute a tremendous amount of responsibility to the people who actually do the work, from the most senior, expeirenced member of the organization to the most junior. This is accomplished because of the tremendous emphasis on teaching everyone how to be a skillful problem solver. How do they do this? They do this by teaching people to solve problems by solving problems. For instance, in our paper we describe a team at a Toyota supplier, Aisin. The team members, when they were first hired, were inexperienced with at best an average high school education. In the first phase of their employment, the hurdle was merely learning how to do the routine work for which they were responsible. Soon thereafter though, they learned how to immediately identify problems that occurred as they did their work. Then they learned how to do sophisticated root-cause analysis to find the underlying conditions that created the symptoms that they had experienced. Then they regularly practiced developing counter-measures—changes in work, tool, product, or process design—that would remove the underlying root causes. Sounds impressive. Yes, but frustrating. They complained that when they started, they were "blissful in their ignorance." But after this sustained development, they could now see problems, root down to their probable cause, design solutions, but the team members couldn't actually implement these solutions. Therefore, as a final round, the team members received training in various technical crafts—one became a licensed electrician, another a machinist, another learned some carpentry skills. Was this unique? Absolutely not. We saw the similar approach repeated elsewhere. At Taiheiyo, another supplier, team members made sophisticated improvements in robotic welding equipment that reduced cost, increased quality, and won recognition with an award from the Ministry of Environment. At NHK (Nippon Spring) another team conducted a series of experiments that increased quality, productivity, and efficiency in a seat production line. What is the role of the manager in this process? Your question about the role of the manager gets right to the heart of the difficulty of managing this way. For many people, it requires a profound shift in mind-set in terms of how the manager envisions his or her role. For the team at Aisin to become so skilled as problem solvers, they had to be led through their training by a capable team leader and group leader. The team leader and group leader were capable of teaching these skills in a directed, learn-by-doing fashion, because they too were consistently trained in a similar fashion by their immediate senior. We found that in the best TPS-managed plants, there was a pathway of learning and teaching that cascaded from the most senior levels to the most junior. In effect, the needs of people directly touching the work determined the assistance, problem solving, and training activities of those more senior. This is a sharp contrast, in fact a near inversion, in terms of who works for whom when compared with the more traditional, centralized command and control system characterized by a downward diffusion of work orders and an upward reporting of work status. And if you are hiring a manager to help run this system, what are the attributes of the ideal candidate? We observed that the best managers in these TPS managed organizations, and the managers in organizations that seem to adopt the Rules-in-Use approach most rapidly are humble but also self-confident enough to be great learners and terrific teachers. Furthermore, they are willing to subscribe to a consistent set of values. How do you mean? Again, it is what is implied in the guideline of specifying every design, testing with every use, and improving close in time, place, and person to the occurrence of every problem. If we do this consistently, we are saying through our action that when people come to work, they are entitled to expect that they will succeed in doing something of value for another person. If they don't succeed, they are entitled to know immediately that they have not. And when they have not succeeded, they have the right to expect that they will be involved in creating a solution that makes success more likely on the next try. People who cannot subscribe to these ideas—neither in their words nor in their actions—are not likely to manage effectively in this system. That sounds somewhat high-minded and esoteric. I agree with you that it strikes the ear as sounding high principled but perhaps not practical. However, I'm fundamentally an empiricist, so I have to go back to what we have observed. In organizations in which managers really live by these Rules, either in the Toyota system or at sites that have successfully transformed themselves, there is a palpable, positive difference in the attitude of people that is coupled with exceptional performance along critical business measures such as quality, cost, safety, and cycle time. Have any other research projects evolved from your findings? We titled the results of our initial research "Decoding the DNA of the Toyota Production System." Kent and I are reasonably confident that the Rules-in-Use about which we have written are a successful decoding. Now, we are trying to "replicate the DNA" at a variety of sites. We want to know where and when these Rules create great value, and where they do, how they can be implemented most effectively. Since we are empiricists, we are conducting experiments through our field research. We are part of a fairly ambitious effort at Alcoa to develop and deploy the Alcoa Business System, ABS. This is a fusion of Alcoa's long standing value system, which has helped make Alcoa the safest employer in the country, with the Rules in Use. That effort has been going on for a number of years, first with the enthusiastic support of Alcoa's former CEO, Paul O'Neill, now Secretary of the Treasury (not your typical retirement, eh?) and now with the backing of Alain Belda, the company's current head. There have been some really inspirational early results in places as disparate as Hernando, Mississippi and Poces de Caldas, Brazil and with processes as disparate as smelting, extrusion, die design, and finance. We also started creating pilot sites in the health care industry. We started our work with a "learning unit" at Deaconess-Glover Hospital in Needham, not far from campus. We've got a series of case studies that captures some of the learnings from that effort. More recently, we've established pilot sites at Presbyterian and South Side Hospitals, both part of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. This work is part of a larger, comprehensive effort being made under the auspices of the Pittsburgh Regional Healthcare Initiative, with broad community support, with cooperation from the Centers for Disease Control, and with backing from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Also, we've been testing these ideas with our students: Kent in the first year Technology and Operations Management class for which he is course head, me in a second year elective called Running and Growing the Small Company, and both of us in an Executive Education course in which we participate called Building Competitive Advantage Through Operations. · · · · Steven Spear is an Assistant Professor in the Technology and Operations Management Unit at the Harvard Business School. Other HBS Working Knowledge stories featuring Steven J. Spear: Decoding the DNA of the Toyota Production System Why Your Organization Isn't Learning All It Should Developing Skillful Problem Solvers: IntroductionWithin TPS-managed organizations, people are trained to improve the work that they perform, they learn to do this with the guidance of a capable supplier of assistance and training, and training occurs by solving production and delivery-related problems as bona fide, hypothesis-testing experiments. Examples of this approach follow.

Defining conditions as problematic We concluded that within Toyota Production System-managed organizations three sets of conditions are considered problematic and prompt problem-solving efforts. These are summarized here and are discussed more fully in a separate paper titled "Pursuing the IDEAL: Conditions that Prompt Problem Solving in Toyota Production System-Managed Organizations." Failure to meet a customer need It was typically recognized as a problem if someone was unable to provide the good, service, or information needed by an immediate or external customer. Failure to do work as designed Even if someone was able to meet the need of his or her customers without fail (agreed upon mix, volume, and timing of goods and services), it was typically recognized as a problem if a person was unable to do his or her own individual work or convey requests (i.e., "Please send me this good or service that I need to do my work.") and responses (i.e., "Here is the good or service that you requested, in the quantity you requested."). Failure to do work in an IDEAL fashion Even if someone could meet customer needs and do his or her work as designed, it was typically recognized as a problem if that person's work was not IDEAL. IDEAL production and delivery is that which is defect-free, done on demand, in batches of one, immediate, without waste, and in an environment that is physically, emotionally, and professionally safe. The improvement activities detailed in the cases that follow, the reader will see, were motivated not so much by a failure to meet customer needs or do work as designed. Rather, they were motivated by costs that were too high (i.e., Taiheiyo robotic welding operation), batch sizes that were too great (i.e., the TSSC improvement activity evaluated by Mr. Ohba), lead-times that were too long, processes that were defect-causing (i.e., NHK cold-forming process), and by compromises to safety (i.e., Taiheiyo). Our field research suggests that Toyota and those of its suppliers that are especially adroit at the Toyota Production System make a deliberate effort to develop the problem-solving skills of workers—even those engaged in the most routine production and delivery. We saw evidence of this in the Taiheiyo, NHK, and Aisin quality circle examples. Forums are created in which problem solving can be learned in a learn-by-doing fashion. This point was evident in the quality circle examples. It was also evident to us in the role played by Aisin's Operations Management Consulting Division (OMCD), Toyota's OMCD unit in Japan, and Toyota's Toyota Supplier Support Center (TSSC) in North America. All of these organizations support the improvement efforts of the companies' factories and those of the companies' suppliers. In doing so, these organizations give operating managers opportunities to hone their problem-solving and teaching skills, relieved temporarily of day to day responsibility for managing, production and delivery of goods and services to external customers. Learning occurs with the guidance of a capable teacher. This was evident in that each of the quality circles had a specific group leader who acted as coach for the quality circle's team leader. We also saw how Mr. Seto at NHK defined his role as, in part, as developing the problem-solving and teaching skills of the team leader whom he supervised. Problem solving occurs as bona fide experiments. We saw this evident in the experience of the quality circles who learned to organize their efforts as bona fide experiments rather than as ad hoc attempts to find a feasible, sufficient solution. The documentation prepared by the senior team at Aisin is organized precisely to capture improvement ideas as refutable hypotheses. Broadly dispersed scientific problem solving as a dynamic capability Problem solving, as illustrated in this paper, is a classic example of a dynamic capability highlighted in the "resource-based" view of the firm literature. Scientific problem solving—as a broadly dispersed skill—is time consuming to develop and difficult to imitate. Emulation would require a similar investment in time, and, more importantly, in managerial resources available to teach, coach, assist, and direct. For organizations currently operating with a more traditional command and control approach, allocating such managerial resources would require more than a reallocation of time across a differing set of priorities. It would also require an adjustment of values and the processes through which those processes are expressed. Christensen would argue that existing organizations are particularly handicapped in making such adjustments. Excerpted with permission from "Developing Skillful Problem Solvers in Toyota Production System-Managed Organizations: Learning to Problem Solve by Solving Problems," HBS Working Paper , 2001.  Product details Time periodGeographical setting, featured company, featured protagonist.

Toyota has actively propelled growth and innovation in its information systems by incorporating new information processing technologies while responding to various changes in the external environment, including rapid globalization of development, manufacturing, and sales operations; advancements in car electronics technologies; compliance with global environmental standards; and changes in the Japanese and global economy. Growth and innovation of information systems at Toyota in the second half of the 1980s to first half of the 1990s saw advances in office automation and in the globalization of corporate systems in the commercial systems of business application systems. In the engineering systems of business application systems, Toyota applied in-house-developed CAD/CAM systems to broader areas of activity and also extended them to supplier operations. From the second half of the 1990s to the early 2000s, advancements in administrative systems made information systems more globally adaptable and also brought about reform of Toyota's overall management structure. Innovations in engineering system made engineering data more integrated and more useable on a global basis. From the early to late 2000s, Toyota sought to globally standardize all business application systems and make better use of information. Even such IT infrastructure as IC network systems were globally standardized and shifted to TCP/IP-based systems in Japan and overseas. The economic crisis that shook the world from 2008 to 2009 also had a major impact on Toyota's information divisions. Since then, Toyota has sought to improve the efficiency of system development and maintenance and has instituted structural reform of its system development and maintenance organization.

Developments in Business Data Processing Systems

Computer Systems Introduced Bill of Materials Order Systems

Reference guide

Capital MarketsConsumer goods, government and public services, life sciences, manufacturing, experiences.

Microsoft Technology Services

Integrated Solutions

Managed ServicesTechnology partnerships, client success stories, join avanade, life at avanade, internships, search jobs, responsible business.

What matters to Toyota is realizing digitalization that drives the future Share this pageBusiness situation. As a world leader in innovative automotive products, Toyota Motor Corporation (Toyota) is fully committed to advancing digitalization throughout the company. To promote this digitalization, company leadership understands that all employees need to become agents of change. As such, Toyota is using “citizen development” as an effective means of solving onsite problems. This involves allowing employees with knowledge about their specific workplace needs to use no-code/low-code development tools to independently transform their business operations. Having seen the short lead times that were possible for development using Microsoft Power Platform , management wanted to maximize the benefits of no-code/low-code development and increase the number of citizen developers in the company. Subsequently, Microsoft Teams was introduced within Toyota and a technical community was launched on the platform. "I think that what is essential for digital transformation is not to arrive at the top of the mountain and achieve a goal, but to create a state that is flexible enough to be able to respond to this wave of ever-changing conditions." Mr. Kenji Nagata Digital Transformation Promotion Department, Toyota Motor Corporation The main activities of the citizen developer community include knowledge, expertise sharing and QA support. Within six months, more than 3,000 employees were part of the community. Since they volunteer outside of their main duties, the influx of novice users and their needs for support created a challenge for some of the more experienced community participants. To support the growing interest in citizen development being embraced across the company, Toyota’s Information Systems Division partnered with Avanade to create a centre of excellence (CoE) to strengthen skills acquisition, self-help and support options for community members. The CoE supports the promotion of internal digital transformation, focusing on four priorities: 1. Education that supports employee development 2. Support for the promotion and popularization of employee development activities 3. Governance support 4. Service expansion to optimize smaller projects company-wide Eight months after Avanade began providing support, employees are embracing digitalization. More than 1,200 technical counselling sessions were held, with more than 60% of participants improving their skills to intermediate levels. The number of active developers also grew to 2,845. Extending employees’ technical capabilities is a benefit of working with Avanade, especially for those who have never developed software before. This support also allows some employees to focus on user interface and user experience development. In the future, Toyota leadership would like to expand the focus on digitalization through citizen development to other Toyota Group companies. Related Client StoriesSee the services we offer and the vision that informs them. Insights to help you do what you do better, faster and more profitably. About AvanadeAvanade is the leading provider of innovative digital, cloud and advisory services, industry solutions and design-led experiences across the Microsoft ecosystem. Explore careers at Avanade, the leading provider of innovative IT consulting services focused on the Microsoft platform. Media CenterKeep tabs on how and why we’re leading the marketplace. Register to download the full Point of View.

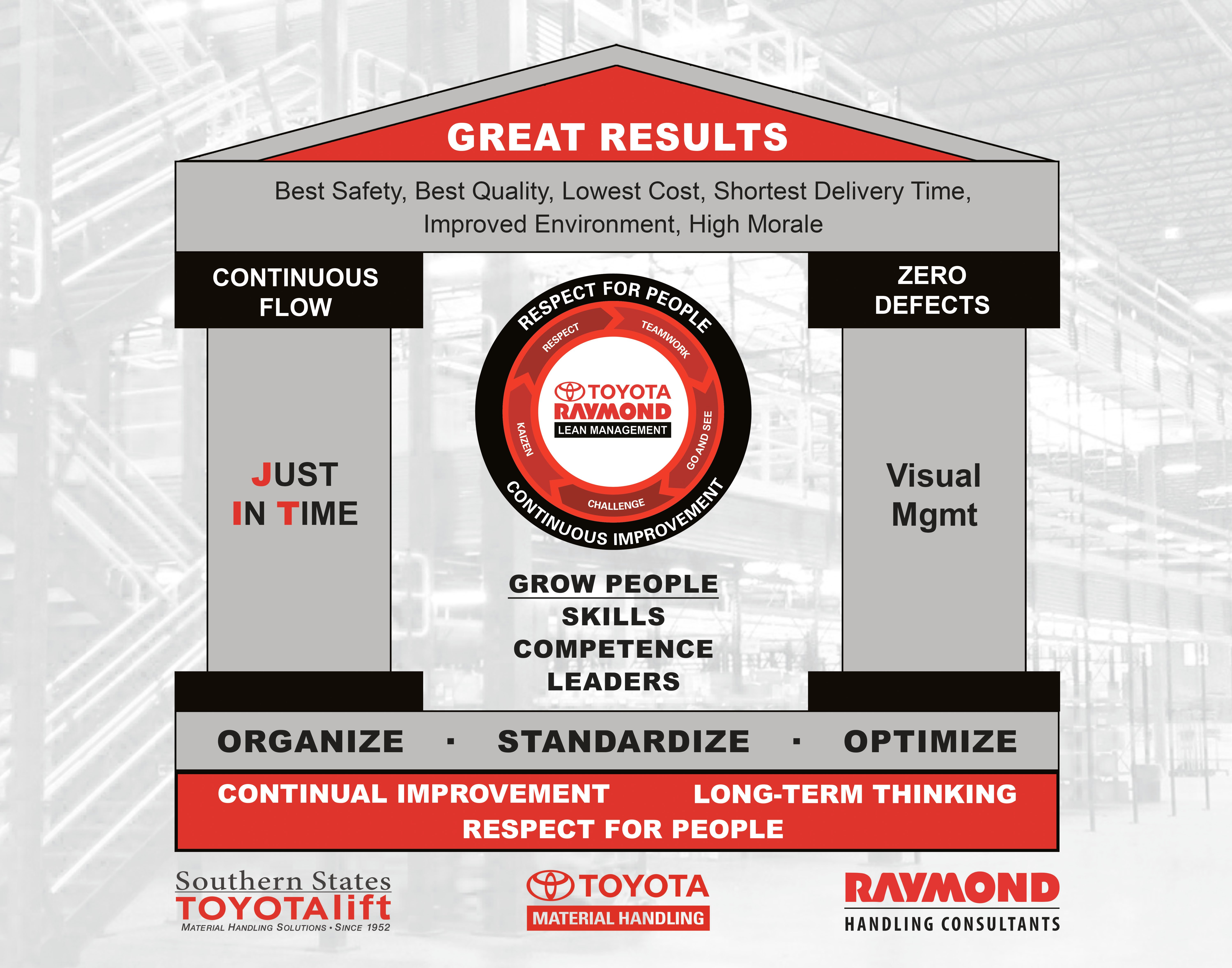

Toyota’s Lean Management Program Explained (with Real Life Examples)by Frank Stuart , on Nov 1, 2023 3:45:00 AM  If you’ve ever searched for information online about the Toyota Production System, you've probably seen a variety of house-shaped graphics. But even though we all know what a house is, understanding what the TPS house graphic means can be a challenge — especially when some of the words are Japanese. In this article, I’ll explain the house graphic and Toyota’s lean management principles. Because I worked for Toyota and have spent many years as a Toyota lean practitioner, I’ll share insights you won’t find anywhere else including:

The Toyota Production System is What Makes Toyota #1Toyota has made the best-selling forklift in North America since 2002. That’s a long time to be number one. How do they do it? By following the Toyota Production System (TPS). What is Toyota Lean Management vs. The Toyota Production System? Toyota Lean Management (TLM) is a system that takes the principles of the Toyota Production System and applies them to other industries such as construction, supply chain, healthcare and of course manufacturing. I’ve yet to find a business that doesn’t benefit from the Toyota production management system. Toyota Principles Improve Retention and Your Bottom LineImproving efficiency and customer satisfaction are the best-known reasons for following Toyota’s lean management practices. Most people don't know it can also improve employee retention. Hiring and retaining qualified workers was the number one challenge reported in MHI’s 2024 Top Supply Chain Challenges survey . The responses come from more than 2000 manufacturing and supply chain industry leaders from a wide range of industries. This isn’t the first year hiring and retention created major heartburn for supply chain operations, and it likely won’t be the last. If finding and keeping good people is something your organization struggles with, TLM can help with that too .  Here’s my version of the TPS house. Why is it a House?Most people use a house-shaped graphic to explain TPS because the function of a house is to preserve what’s inside . All the parts of the house interact with each other to protect what’s the business and its people — from the groundwork to the pillars to the roof. The GroundworkRespect for People, Long-Term Thinking and Continually Improve Respect for People, Long-Term Thinking and Continually Improve are fundamental management philosophies that drive all policy and decision-making under the Toyota way. Respect for People is not about being nice (although that is important). This principle is about creating a home-like atmosphere where everyone is encouraged and supported to reach their full potential. EXAMPLE: A supervisor has monthly one-on-one meetings with each associate to:

This mentor-mentee program develops people from within. Associates move into higher and higher positions so eventually, the people leading the company not only know the product but understand the work. Respect for people also includes being mindful of how decisions in one department affect another. Uncoordinated decisions can negatively impact the customer. EXAMPLE: If sales and marketing decide to have a big sale the weekend before Thanksgiving, the extra orders could overwhelm an already understaffed shipping department — creating delays for the customer and/or increased overtime expenses. Last but not least, respect for people means providing stable employment. This leads us to the next fundamental principle… Long-Term Thinking — During COVID and the supply chain challenges that followed, many companies made the hard decision to lay off workers. I was in the training department at Raymond during this time. Instead of letting workers go, we chose to strengthen the company by training associates and improving processes. We developed online training programs on various topics for hundreds of associates in various roles. These actions and this type of thinking goes back to the 1950s when Toyota decided to focus on building a strong, stable company for the long term. The economy will cycle up and down, but because our people are our most important asset, we must take care of them and protect them, even during economic downturns. Short-term decisions, like letting experienced and tenured employees go, can improve the bottom line in the short term, but long term it hurts the business. All too often, corporate culture lives and dies on a quarterly report. This is short-sighted. When times are good, you have to squirrel money away in your war chest to protect the company and its people when times are bad . Continually Improve – It is said in business, as in life, we are either growing or dying. A structured focus on continual improvement ( kaizen ) and challenging the status quo ensures a company stays competitive and growing. EXAMPLE: We challenged the team who reconditioned our forklifts this year. At the beginning of the year, our lead time was 12 weeks. By mapping the process, improving flow and using a kaizen philosophy, we are now at 6 weeks. We are not satisfied with this improvement and have further challenged the team to cut the lead time in half again by the end of this year.  The FoundationOrganize, Standardize, Optimize The next level of the TPS house is all about creating an efficient work environment. It starts with a clean, orderly workspace where the next tool (or whatever the worker needs) is right there and not hidden in a pile of clutter. If we don’t give people an organized workspace and standards to follow, we’re not helping them be successful. Even worse, we’re wasting their time. It goes back to respect for people. EXAMPLE: The litmus test I used in the factory was to have a workstation set up with all the necessary tools. If I could take a tool away from the workstation and the operator couldn’t tell me within five seconds what was missing, that meant we had more work to do to. To be clear, it isn’t about telling people: you must do it this way or to make changes for the sake of making changes. The goal is to:

That last bullet point is the principle of kaizen showing up again. Toyota Lean Management is an ongoing process where small, incremental changes result in measurable improvements to quality or reduced cost, cycle or delivery times. FYI, we haven’t gotten to the actual Toyota Production System yet. The groundwork and the foundation are the basis for TPS. The system doesn’t work without establishing the groundwork and creating a solid foundation. Creating optimized workspaces and processes are deceptively simple assignments. It’s really easy to make work hard and it’s hard to make work easy. When you’re stuck in chaos it can be hard to see the way out. The foundation of TPS helps make work easy. Once an orderly, efficient system has been established, we work on the two pillars. TPS Pillars: The Toyota Production SystemJust in Time & Continuous Flow The first pillar is all about having what you need, when you need it. Waste, in the form of wasted time or excess inventory, should be avoided. Back in 2021, Bloomberg and other news organizations excitedly reported how Toyota had abandoned its “just in time” philosophy because it started stockpiling computer chips. This is just one example of how Toyota principles are misunderstood by the Western world. Misunderstanding #1 Here’s what most news outlets got wrong: After the earthquake and tsunami in 2011, Toyota reevaluated the lead time required for semiconductors and other parts. Their assessment revealed they were unprepared for a major shock to the supply chain, such a natural disaster. To ensure a continuous flow of chips to their factories, Toyota required suppliers to carry a 2-6 month supply of semiconductors. When COVID hit, the news reported Toyota was “stockpiling” chips when, in fact, the company was simply following a plan it had created ten years earlier.  Our business training in the Western world is all about the balance sheet. Reducing inventory becomes a goal unto itself and that’s when things start to go badly. “Just in time” doesn’t mean “last minute.” It means keeping enough supply to ensure a continuous flow. For Toyota, "just in time" meant a supply that could weather supply chain ups and downs. In 2021, when the chip shortage forced other automakers to stop their production lines, Toyota kept churning out vehicles and raised its earnings forecast by 54% . Visual Management & Zero Defects EXAMPLE: Zero defects is pretty self-explanatory, but here’s an example of zero defects through visual management. The first thing Mr. Toyoda built was an automated loom for the textile industry. Occasionally, a thread would break and the operator wouldn’t see it. When this happened, the final product had to be thrown away. To fix the problem, Mr. Toyoda put a washer in the thread. If the thread broke, the washer fell off into the machine and it stopped. The operator could fix the problem without any waste (defective product). This also allowed one operator to oversee multiple machines. Misunderstanding #2 Some people say Toyota Lean Management is basically the same as Six Sigma. I disagree. There are major differences between the two systems , but here’s a big one related to TPS Pillar Two: Six Sigma says you can have 3.4 defects per million operations. An “operation” is defined as a single action, such as attaching a wire or screwing a bolt. Building a jumbo jet requires millions of operations. Knowing 3.4 defects are permitted per million operations, would you rather fly on an airplane built by a company that follows Six Sigma principles or Toyota? Another comparison you may have heard is one about a GM versus a Toyota factory. At GM, workers can get in trouble for stopping the line. At Toyota, it’s the opposite. If workers aren’t periodically stopping the line, managers get concerned. It goes back to the fundamental principles we talked about in the very beginning: respect for people and a culture of continuous improvement. Toyota Lean Management Case StudyI worked with a hard cider manufacturer in upstate NY. The company was approaching its busy season and trying to build up its inventory to supply its distributor. Their “we gotta get this done” mentality caused them to overrun their facility. A Foundational Problem The company thought they were following the “just in time” lean methodology. What they had was a mess.

A bottleneck in their system meant a new batch would get stuck behind the previous batch and unfinished inventory would pile up. Disorganization and stress led to unnecessary handling, damage and waste (wasted time and wasted product). After speaking to everyone who helped produce the cider, we created a list of best practices. Next, we helped the company organize, standardize and optimize the workspaces and procedures throughout their facility. With groundwork laid and a firm foundation in place, we were ready to move on to Pillars One and Two.  Guess what? The company had more than enough capacity. They didn’t need to build up inventory for their distributor. All they had to do was tame their operational chaos.

Cider Batches Now Flow Continuously Once the bottleneck was subdued and equipment was kept in good working order, the cider company could run continuously with minimal downtime between batches. By staggering five batches to start over six weeks the company could meet customer demands. The Core of the House: Its PeopleGrow People: Skills, Competence, Leaders I added this circle in the center of the house (you won’t find it in other TPS house graphics) because I was fortunate to learn about Toyota’s lean management system directly from Toyota executives. The addition was inspired by a story I heard that really stuck in my mind. Mr. Onishi, Toyota’s president, visited a plant in Canada. He asked one of the plant managers to explain TPS. The manager described the house and the elements of zero defects, continuous improvement, etc. Mr. Onishi politely said, “It’s actually a people development process. We want to improve people’s skills and competence and grow them into leaders. Our goal is to promote people from within because they know the products, the customers and understand the work.” The TPS CircleEverything starts and ends with respect. Teamwork is about supporting the person who does the thing the customer is paying for. EXAMPLE: At SST, that means the technician working on a customer’s forklift. Go and See — when a problem arises, the best way to find a solution is to observe the problem. EXAMPLE #1: At the forklift factory, units occasionally came off the line with the wrong counterweight. We observed the employee do everything right until one time he read the build sheet but chose the wrong counterweight. He was always on the go which created an opportunity for this mistake. By adding a simple step, stopping to highlight the weight info, the problem disappeared.  EXAMPLE #2: A warehouse thought they needed to buy more pallet rack and even had a rack consultant on-site while I was there. Turns out the company had plenty of rack space. They just needed to throw out three years of inventory they couldn't sell. The executive team almost wasted thousands of dollars on rack they didn’t need rather than take a hit on their balance sheet. Challenge does not mean I had a challenging day because two associates didn’t show up for work. It means aiming for the stars and making it to the moon. To generate significant improvements, you need an aggressive challenge and a team that’s committed to reaching a common goal. It changes your approach. To keep the space analogy going, consider all the technological innovations we enjoy that came from putting a man on the moon . Misunderstanding #3 Toyota’s Production System strives for 100% customer satisfaction by eliminating wasteful activities. Many business leaders incorrectly believe running lean means using cheaper materials or reducing staff. By now you know this isn't the Toyota way. Building a strong house requires leaders who respect their people and think long-term. Companies that refuse to think beyond the bottom line will always struggle to stay competitive. Their short-term savings on cheap materials create long-term losses as customers become dissatisfied. They will also waste money hiring and training people who leave when they aren’t treated with respect. Sometimes I have to have a conversation with new clients about helping team members overcome challenges. When something goes wrong, some companies look for someone to blame (reprimand or fire) but that’s not the Toyota way. Toyota’s approach focuses on fixing broken systems, not pointing fingers. We encourage leaders to challenge their team members to improve processes, but if the team member fails and gets fired after one try, how is that person’s replacement going to feel about taking on the same challenge? The Roof of the TPS HouseThe roof protects the house and the people inside. A safe workplace that produces quality products at the lowest cost with the shortest delivery time in a good environment generates high morale and protects the business. By protecting the business, you protect the people inside and help them to grow into successful leaders. Request a Free Toyota Lean Management ConsultationIf you’d like to reduce costs and turnover while increasing customer satisfaction, why not schedule a free consultation ? Toyota Lean Management has a low cost of implementation and is designed to help you get more out of your existing resources. During the initial consultation, we’ll talk about where your company is now versus where you’d like to be. The next steps depend on the individual client, but typically we’ll Go and See your space and look for:

To learn more, contact us online or by phone (800) 226-2345. FLORIDA : Jacksonville South, Jacksonville North, Ocala, Orlando, Lakeland, Tampa, Winter Haven GEORGIA : Albany, Macon, Midland, Valdosta  The SST BlogWant to increase your productivity, increase your safety, and increase your profits? Our blog can help. Fill out our form below to subscribe. Subscribe to Updates

Southern States ToyotaliftCorporate office 115 s. 78th st, tampa, fl 33619 call: 800.226.2345 • 813.734.7940 accounts receivable: (813) 549-3545 / [email protected], florida locations. Winter Haven, FL 863.967.8551 Orlando, FL 407.859.3000 Ocala, FL 352.840.0030 Jacksonville, FL 904.764.7662 Lakeland, FL 863.577.5438 Georgia LocationsValdosta, GA 229.247.8377 Macon, GA 478.788.0520 Midland, GA 706.660.0067 Albany, GA 229.338.7277

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Toyota ERP System Case Study: Conclusion. The key research objective was to determine how an organization can use Enterprise Resource Planning, as an information system, in order to enhance productivity. Through the Toyota case study, it was evident that information synchronization, business intelligence and elimination of redundancy enable ...

Save. Summary. Toyota has fared better than many of its competitors in riding out the supply chain disruptions of recent years. But focusing on how Toyota had stockpiled semiconductors and the ...

3.7 Case Study: Toyota's Successful Strategy in Indonesia 3.8 Strategic M&A, Partnerships, Joint Ventures, and Alliances ... Toyota's distinctive competence is its production system known as the "Toyota Production System" or TPS. TPS is based on the Lean Manufacturing concept. This concept also includes innovative practices like Just in ...

Stable and paranoid, systematic and experimental, formal and frank: The success of Toyota, a pathbreaking six-year study reveals, is due as much to its ability to embrace contradictions like these ...

This case study was prepared by Paul Betancourt and John Mooney of Pepperdine University Graziadio School of Business ... and Jeanne W. Ross of the MIT Sloan Center for Information Systems Research. This case was written for the purposes of class discussion, rather than to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of a managerial ...

In 2020 Toyota Motor Corporation (TMC) was the world's top-selling car manufacturer. Despite this, the company was being driven to excel further in response to changing consumer expectations, technological developments, and new kinds of entrants into the automotive industry. Toyota's leaders sought to accelerate the company's culture of incremental innovation and realize a bold new ...

Abstract. This paper focuses on the effectiveness of corporate strategy in making engineering organizations successful with a specific case study of Toyota Motors Corporation. The Study uses two ...

The American Big Three and many other auto companies had done major benchmarking studies, and they and other companies had tried to implement their own forms of the Toyota Production System. There is the Ford Production System, the Chrysler Operating System, and General Motors went so far as to establish a joint venture with Toyota called NUMMI ...

Product details. The Changing Face of the Information Systems at Toyota. Case. -. Reference no. 920-0031-1. Subject category: Knowledge, Information and Communication Systems Management. Authors: Vinod Babu Koti (IBS Center for Management Research); V Namratha Prasad (IBS Center for Management Research) Published by: IBS Center for Management ...

Toyota has actively propelled growth and innovation in its information systems by incorporating new information processing technologies while responding to various changes in the external environment, including rapid globalization of development, manufacturing, and sales operations; advancements in car electronics technologies; compliance with global environmental standards; and changes in the ...

Abstract. This case discusses the changes in the Information Systems (IS) at Japanese multinational automotive manufacturer Toyota Motor Corporation (TMC) in its key operations, through the years. Based on the changes sweeping through the industry, TMC integrated new information processing technologies in processes such as new product ...

Eight months after Avanade began providing support, employees are embracing digitalization. More than 1,200 technical counselling sessions were held, with more than 60% of participants improving their skills to intermediate levels. The number of active developers also grew to 2,845. Extending employees' technical capabilities is a benefit of ...

Toyota digital transformation case study What matters to Toyota is realizing digitalization that drives the future ... Toyota's Information Systems Division partnered with Avanade to create a centre of excellence (CoE) to strengthen skills acquisition, self-help and support options for community members. The CoE supports the promotion of ...

Toyota had long been managing its freight carriers using a "balanced scorecard" approach, but little input from its freight payment process factored into this assessment. For example, without the data from the Cass system, Toyota couldn't easily measure suppliers on invoice

This case discusses the changes in the Information Systems (IS) at Japanese multinational automotive manufacturer Toyota Motor Corporation (TMC) in its key operations, through the years. LEGO blocks - reusable interlocking plastic blocks that could be assembled to construct different objects - were equally popular among children and adults

Toyota's IT Transformation. The information systems group at Toyota Motor Sales USA Inc. has moved from an "order-taker" role to "next-generation demand management" in an effort to meet overall corporate needs. This article was written with Karen Nocket. The information technology organizations in many companies are trying to evolve from an ...

The Toyota Way Model was introduced). 12. Implementation of TQM in Automotive Industry: o Internally, there are four fields of quality management in the Automotive industry: • Sales - directly ...