- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

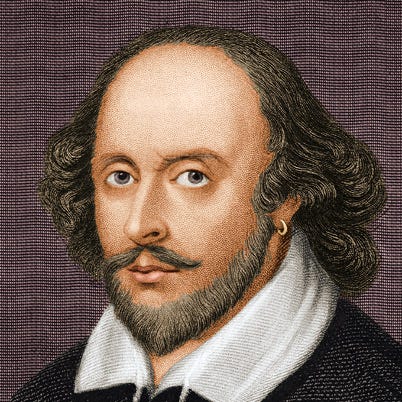

William Shakespeare

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 7, 2019 | Original: October 3, 2011

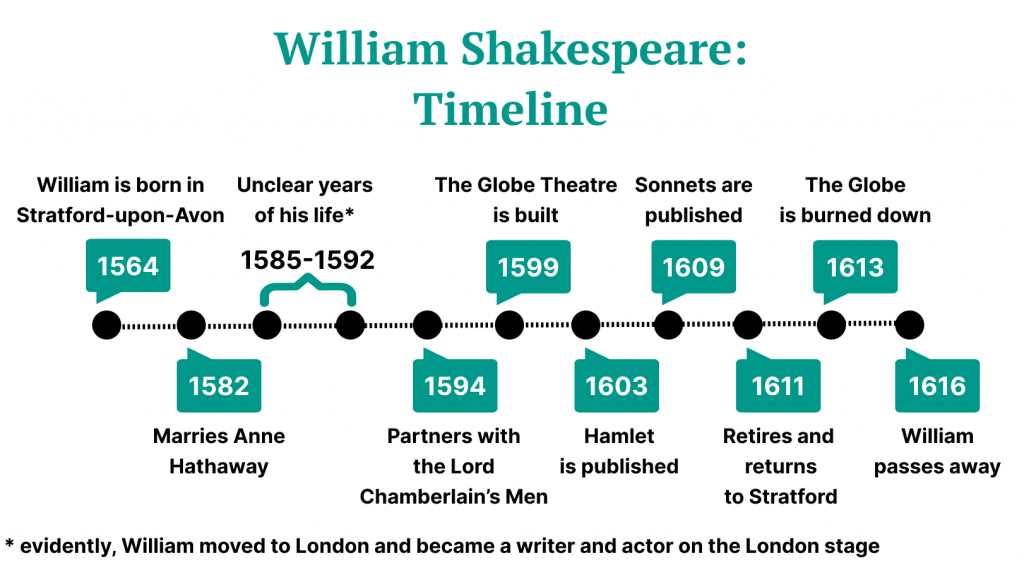

Considered the greatest English-speaking writer in history and known as England’s national poet, William Shakespeare (1564-1616) has had more theatrical works performed than any other playwright. To this day, countless theater festivals around the world honor his work, students memorize his eloquent poems and scholars reinterpret the million words of text he composed. They also hunt for clues about the life of the man who inspires such “bardolatry” (as George Bernard Shaw derisively called it), much of which remains shrouded in mystery. Born into a family of modest means in Elizabethan England, the “Bard of Avon” wrote at least 37 plays and a collection of sonnets, established the legendary Globe theater and helped transform the English language.

Shakespeare’s Childhood and Family Life

William Shakespeare was born in Stratford-upon-Avon, a bustling market town 100 miles northwest of London, and baptized there on April 26, 1564. His birthday is traditionally celebrated on April 23, which was the date of his death in 1616 and is the feast day of St. George, the patron saint of England. Shakespeare’s father, John, dabbled in farming, wood trading, tanning, leatherwork, money lending and other occupations; he also held a series of municipal positions before falling into debt in the late 1580s. The ambitious son of a tenant farmer, John boosted his social status by marrying Mary Arden, the daughter of an aristocratic landowner. Like John, she may have been a practicing Catholic at a time when those who rejected the newly established Church of England faced persecution.

Did you know? Sources from William Shakespeare's lifetime spell his last name in more than 80 different ways, ranging from “Shappere” to “Shaxberd.” In the handful of signatures that have survived, he himself never spelled his name “William Shakespeare,” using variations such as “Willm Shakspere” and “William Shakspeare” instead.

William was the third of eight Shakespeare children, of whom three died in childhood. Though no records of his education survive, it is likely that he attended the well-regarded local grammar school, where he would have studied Latin grammar and classics. It is unknown whether he completed his studies or abandoned them as an adolescent to apprentice with his father.

At 18 Shakespeare married Anne Hathaway (1556-1616), a woman eight years his senior, in a ceremony thought to have been hastily arranged due to her pregnancy. A daughter, Susanna, was born less than seven months later in May 1583. Twins Hamnet and Judith followed in February 1585. Susanna and Judith would live to old age, while Hamnet, Shakespeare’s only son, died at 11. As for William and Anne, it is believed that the couple lived apart for most of the year while the bard pursued his writing and theater career in London. It was not until the end of his life that Shakespeare moved back in with Anne in their Stratford home.

Shakespeare’s Lost Years and Early Career

To the dismay of his biographers, Shakespeare disappears from the historical record between 1585, when his twins’ baptism was recorded, and 1592, when the playwright Robert Greene denounced him in a pamphlet as an “upstart crow” (evidence that he had already made a name for himself on the London stage). What did the newly married father and future literary icon do during those seven “lost” years? Historians have speculated that he worked as a schoolteacher, studied law, traveled across continental Europe or joined an acting troupe that was passing through Stratford. According to one 17th-century account, he fled his hometown after poaching deer from a local politician’s estate.

Whatever the answer, by 1592 Shakespeare had begun working as an actor, penned several plays and spent enough time in London to write about its geography, culture and diverse personalities with great authority. Even his earliest works evince knowledge of European affairs and foreign countries, familiarity with the royal court and general erudition that might seem unattainable to a young man raised in the provinces by parents who were probably illiterate. For this reason, some theorists have suggested that one or several authors wishing to conceal their true identity used the person of William Shakespeare as a front. (Most scholars and literary historians dismiss this hypothesis, although many suspect Shakespeare sometimes collaborated with other playwrights.)

Shakespeare’s Plays and Poems

Shakespeare’s first plays, believed to have been written before or around 1592, encompass all three of the main dramatic genres in the bard’s oeuvre: tragedy (“Titus Andronicus”); comedy (“The Two Gentlemen of Verona,” “The Comedy of Errors” and “The Taming of the Shrew”); and history (the “Henry VI” trilogy and “Richard III”). Shakespeare was likely affiliated with several different theater companies when these early works debuted on the London stage. In 1594 he began writing and acting for a troupe known as the Lord Chamberlain’s Men (renamed the King’s Men when James I appointed himself its patron), ultimately becoming its house playwright and partnering with other members to establish the legendary Globe theater in 1599.

Between the mid-1590s and his retirement around 1612, Shakespeare penned the most famous of his 37-plus plays, including “Romeo and Juliet,” “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” “Hamlet,” “King Lear,” “Macbeth” and “The Tempest.” As a dramatist, he is known for his frequent use of iambic pentameter, meditative soliloquies (such as Hamlet’s ubiquitous “To be, or not to be” speech) and ingenious wordplay. His works weave together and reinvent theatrical conventions dating back to ancient Greece, featuring assorted casts of characters with complex psyches and profoundly human interpersonal conflicts. Some of his plays—notably “All’s Well That Ends Well,” “Measure for Measure” and “Troilus and Cressida”—are characterized by moral ambiguity and jarring shifts in tone, defying, much like life itself, classification as purely tragic or comic.

Also remembered for his non-dramatic contributions, Shakespeare published his first narrative poem—the erotic “Venus and Adonis,” intriguingly dedicated to his close friend Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton—while London theaters were closed due to a plague outbreak in 1593. The many reprints of this piece and a second poem, “The Rape of Lucrece,” hint that during his lifetime the bard was chiefly renowned for his poetry. Shakespeare’s famed collection of sonnets, which address themes ranging from love and sensuality to truth and beauty, was printed in 1609, possibly without its writer’s consent. (It has been suggested that he intended them for his intimate circle only, not the general public.) Perhaps because of their explicit sexual references or dark emotional character, the sonnets did not enjoy the same success as Shakespeare’s earlier lyrical works.

Shakespeare’s Death and Legacy

Shakespeare died at age 52 of unknown causes on April 23, 1616, leaving the bulk of his estate to his daughter Susanna. (Anne Hathaway, who outlived her husband by seven years, famously received his “second-best bed.”) The slabstone over Shakespeare’s tomb, located inside a Stratford church, bears an epitaph—written, some say, by the bard himself—warding off grave robbers with a curse: “Blessed be the man that spares these stones, / And cursed be he that moves my bones.” His remains have yet to be disturbed, despite requests by archaeologists keen to reveal what killed him.

In 1623, two of Shakespeare’s former colleagues published a collection of his plays, commonly known as the First Folio. In its preface, the dramatist Ben Jonson wrote of his late contemporary, “He was not of an age, but for all time.” Indeed, Shakespeare’s plays continue to grace stages and resonate with audiences around the world, and have yielded a vast array of film, television and theatrical adaptations. Furthermore, Shakespeare is believed to have influenced the English language more than any other writer in history, coining—or, at the very least, popularizing—terms and phrases that still regularly crop up in everyday conversation. Examples include the words “fashionable” (“Troilus and Cressida”), “sanctimonious” (“Measure for Measure”), “eyeball” (“A Midsummer Night’s Dream”) and “lackluster” (“As You Like It”); and the expressions “foregone conclusion” (“Othello”), “in a pickle” (“The Tempest”), “wild goose chase” (“Romeo and Juliet”) and “one fell swoop” (“Macbeth”).

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

William Shakespeare

Playwright and poet William Shakespeare is considered the greatest dramatist of all time. His works are loved throughout the world, but Shakespeare’s personal life is shrouded in mystery.

Quick Facts

Wife and children, shakespeare’s lost years, poems and sonnets, the king’s men: life as an actor and playwright, globe theater, william shakespeare’s plays, later years and death, legacy and controversies, who was william shakespeare.

William Shakespeare was an English poet , playwright , and actor of the Renaissance era. He was an important member of the King’s Men theatrical company from roughly 1594 onward. Known throughout the world, Shakespeare’s works—at least 37 plays, 154 sonnets, and 2 narrative poems—capture the range of human emotion and conflict and have been celebrated for more than 400 years. Details about his personal life are limited, though some believe he was born and died on the same day, April 23, 52 years apart.

FULL NAME: William Shakespeare BORN: c. April 23, 1564 DIED: c. April 23, 1616 BIRTHPLACE: Stratford-upon-Avon, England, United Kingdom SPOUSE: Anne Hathaway (1582-1616) CHILDREN: Susanna, Judith, and Hamnet ASTROLOGICAL SIGN: Taurus

The personal life of William Shakespeare is somewhat of a mystery . There are two primary sources that provide historians with an outline of his life. One is his work, and the other is official documentation such as church and court records. However, these provide only brief sketches of specific events in his life and yield little insight into the man himself.

When Was Shakespeare Born?

No birth records exist, but an old church record indicates that William Shakespeare was baptized at Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-upon-Avon on April 26, 1564. From this, it is believed he was born on or near April 23, 1564, and this is the date scholars acknowledge as Shakespeare’s birthday. Located about 100 miles northwest of London, Stratford-upon-Avon was a bustling market town along the River Avon and bisected by a country road during Shakespeare’s time.

Parents and Siblings

Shakespeare was the third child of John Shakespeare, a glove-maker and leather merchant, and Mary Arden, a local heiress to land. John held official positions as alderman and bailiff, an office resembling a mayor. However, records indicate John’s fortunes declined sometime in the late 1570s. Eventually, he recovered somewhat and was granted a coat of arms in 1596, which made him and his sons official gentleman.

John and Mary had eight children together, though three of them did not live past childhood. Their first two children—daughters Joan and Margaret—died in infancy, so William was the oldest surviving offspring. He had three younger brothers and two younger sisters: Gilbert, Joan, Anne, Richard, and Edmund. Anne died at age 7, and Joan was the only sibling to outlive William.

Childhood and Education

Scant records exist of Shakespeare’s childhood and virtually none regarding his education. Scholars have surmised that he most likely attended the King’s New School, in Stratford, which taught reading, writing, and the classics, including Latin. He attended until he was 14 or 15 and did not continue to university. The uncertainty regarding his education has led some people question the authorship of his work.

Shakespeare married Anne Hathaway on November 28, 1582, in Worcester, in Canterbury Province. Hathaway was from Shottery, a small village a mile west of Stratford. Shakespeare was 18, and Anne was 26 and, as it turns out, pregnant.

Their first child, a daughter they named Susanna, was born on May 26, 1583. Two years later, on February 2, 1585, twins Hamnet and Judith were born. Hamnet died of unknown causes at age 11.

There are seven years of Shakespeare’s life where no records exist: after the birth of his twins in 1585 until 1592. Scholars call this period Shakespeare’s lost years, and there is wide speculation about what he was doing during this period.

One theory is that he might have gone into hiding for poaching game from local landlord Sir Thomas Lucy. Another possibility is that he might have been working as an assistant schoolmaster in Lancashire. Some scholars believe he was in London, working as a horse attendant at some of London’s finer theaters before breaking on the scene.

By 1592, there is evidence Shakespeare earned a living as an actor and a playwright in London and possibly had several plays produced. The September 20, 1592, edition of the Stationers’ Register , a guild publication, includes an article by London playwright Robert Greene that takes a few jabs at Shakespeare:

“...There is an upstart Crow, beautified with our feathers, that with his Tiger’s heart wrapped in a Player’s hide, supposes he is as well able to bombast out a blank verse as the best of you: and being an absolute Johannes factotum, is in his own conceit the only Shake-scene in a country.”

Scholars differ on the interpretation of this criticism, but most agree that it was Greene’s way of saying Shakespeare was reaching above his rank, trying to match better known and educated playwrights like Christopher Marlowe , Thomas Nashe, or Greene himself.

Early in his career, Shakespeare was able to attract the attention and patronage of Henry Wriothesley, the Earl of Southampton, to whom he dedicated his first and second published poems: Venus and Adonis (1593) and The Rape of Lucrece (1594). In fact, these long narrative poems—1,194 and 1,855 lines, respectively—were Shakespeare’s first published works. Wriothesley’s financial support was a helpful source of income at a time when the theaters were shuttered due to a plague outbreak.

Shakespeare’s most well-known poetry are his 154 sonnets, which were first published as a collection in 1609 and likely written as early as the 1590s. Scholars broadly categorize the sonnets in groups based on two unknown subjects that Shakespeare addresses: the Fair Youth sonnets (the first 126) and the Dark Lady sonnets (the last 28). The identities of the aristocratic young man and vexing woman continue to be a source of speculation.

In 1594, Shakespeare joined Lord Chamberlain’s Men, the London acting company that he worked with for the duration of his career. Later called the King’s Men, it was considered the most important troupe of its time and was very popular by all accounts. Some sources describe Shakespeare as a founding member of the company, but whatever the case, he became central to its success. Initially, he was an actor and eventually devoted more and more time to writing.

Records show that Shakespeare, who was also a company shareholder, had works published and sold as popular literature. Although The Taming of the Shrew is believed to be the first play that Shakespeare wrote, his first published plays were Titus Andronicus and Henry VI Part 2 . They were printed in 1594 in quarto, an eight-page pamphlet-like book. By the end of 1597, Shakespeare had likely written 16 of his 37 plays and amassed some wealth.

At this time, civil records show Shakespeare purchased one of the largest houses in Stratford, called New Place, for his family. It was a four-day ride by horse from Stratford to London, so it’s believed that Shakespeare spent most of his time in the city writing and acting and came home once a year during the 40-day Lenten period, when the theaters were closed. However, Shakespeare expert and professor Sir Stanley Wells posits that the playwright might have spent more time at home in Stratford than previously believed, only commuting to London when he needed to for work.

Although the theater culture in 16 th century England was not greatly admired by people of high rank, some of the nobility were good patrons of the performing arts and friends of the actors. Two notable exceptions were Queen Elizabeth I , who was a fan of Lord Chamberlain’s Men by the late 1590s after first watching a performance in 1594, and her successor King James I. Following his crowning in 1603, the company changed its name to the King’s Men.

By 1599, Shakespeare and several fellow actors built their own theater on the south bank of the Thames River, which they called the Globe Theater. Julius Caesar is thought to be the first production at the new open-air theater. Owning the playhouse proved to be a financial boon for Shakespeare and the other investors.

In 1613, the Globe caught fire during a performance of Henry VII I and burned to the ground. The company quickly rebuilt it, and it reopened the next year. In 1642, Puritans outlawed all theaters, including the Globe, which was demolished two years later. Centuries passed until American actor Sam Wanamaker began working to resurrect the theater once more. The third Globe Theater opened in 1997, and today, more than 1.25 million people visit it every year.

It’s difficult to determine the exact chronology of Shakespeare’s plays, but over the course of two decades, from about 1590 to 1613, he wrote 37 plays revolving around three main themes: history, tragedy, and comedy. Some plays blur these lines, and over time, our interpretation of them has changed, too.

Shakespeare’s early plays were written in the conventional style of the day, with elaborate metaphors and rhetorical phrases that didn’t always align naturally with the story’s plot or characters. However, Shakespeare was very innovative, adapting the traditional style to his own purposes and creating a freer flow of words.

With only small degrees of variation, Shakespeare primarily used a metrical pattern consisting of lines of unrhymed iambic pentameter, or blank verse, to compose his plays. At the same time, there are passages in all the plays that deviate from this and use forms of poetry or simple prose.

Many of Shakespeare’s first plays were histories. All three Henry VI plays, Richard II , and Henry V dramatize the destructive results of weak or corrupt rulers and have been interpreted by drama historians as Shakespeare’s way of justifying the origins of the Tudor Dynasty. Other histories include Richard III , King John , the two Henry IV plays, and Henry VIII . With exception of Henry VIII , which was Shakespeare’s last play, these works were likely written by 1599.

Although Shakespeare wrote three tragedies, including Romeo and Juliet , before 1600, it wasn’t until after the turn of the century that he truly explored the genre. Character in Othello , King Lear , and Macbeth present vivid impressions of human temperament that are timeless and universal.

Possibly the best known of these plays is Hamlet , which explores betrayal, retribution, incest, and moral failure. These moral failures often drive the twists and turns of Shakespeare’s plots, destroying the hero and those he loves.

Julius Caesar , written in circa 1599, portrays upheaval in Roman politics that might have resonated with viewers at a time when England’s aging monarch, Queen Elizabeth I, had no legitimate heir, thus creating the potential for future power struggles.

Titus Andronicus , Anthony and Cleopatra , Timon of Athens , and Coriolanus are Shakespeare’s other tragic plays.

Shakespeare wrote comedies throughout his career, including his first play The Taming of the Shrew . Some of his other early comedies, written before 1600 or so, are: the whimsical A Midsummer Night’s Dream , the romantic Merchant of Venice , the wit and wordplay of Much Ado About Nothing , and the charming As You Like It .

Some of his comedies might be better described as tragicomedies. Among these are Pericles , Cymbeline , The Winter’s Tale, and The Tempest . Although graver in tone than the comedies, they are not the dark tragedies of King Lear or Macbeth because they end with reconciliation and forgiveness.

Additional Shakespeare comedies include:

- The Two Gentlemen of Verona ,

- The Comedy of Errors ,

- Love’s Labour’s Lost ,

- The Merry Wives of Windsor ,

- Twelfth Night ,

- Measure for Measure , and

- All’s Well That Ends Well

Troilus and Cressida is emblematic of the Shakespearean “problem play,” which defies genres. Some of Shakespeare’s contemporaries classified it as a history or a comedy, though the original name of the play was The Tragedie of Troylus and Cressida .

Collaborations and Lost Play

Shakespeare is known to have created plays with other writers, such as John Fletcher. They co-wrote The Two Noble Kinsmen around 1613–14, making it Shakespeare’s last known dramatic work. They also collaborated on Cardenio , a play which was not preserved. Shakespeare’s other jointly written plays are Sir Thomas More and The Raigne of King Edward the Third . When including these works, Shakespeare has 41 plays to his name.

Around the turn of the 17 th century, Shakespeare became a more extensive property owner in Stratford. When his father, John, died in 1601, he inherited the family home. Then, in 1602, he purchased about 107 acres for 320 pounds.

In 1605, Shakespeare purchased leases of real estate near Stratford for 440 pounds, which doubled in value and earned him 60 pounds a year. This made him an entrepreneur as well as an artist, and scholars believe these investments gave him uninterrupted time to write his plays.

A couple years prior, around 1603, Shakespeare is believed to have stopped acting in the King’s Men productions, instead focusing on his playwriting work. He likely spent the last three years of his life in Stratford.

When Did Shakespeare Die?

Tradition holds that Shakespeare died on his 52 nd birthday, April 23, 1616, but some scholars believe this is a myth. Church records show he was interred at Holy Trinity Church on April 25, 1616. The exact cause of Shakespeare’s death is unknown , though many people believe he died following a brief illness.

In his will, he left the bulk of his possessions to his eldest daughter, Susanna, who by then was married. Although entitled to a third of his estate, little seems to have gone to his wife, Anne, whom he bequeathed his “second-best bed.” This has drawn speculation that she had fallen out of favor or that the couple was not close.

However, there is very little evidence the two had a difficult marriage. Other scholars note that the term “second-best bed” often refers to the bed belonging to the household’s master and mistress, the marital bed, and the “first-best bed” was reserved for guests.

The Bard of Avon has gone down in history as the greatest dramatist of all time and is sometimes called England’s national poet. He is credited with inventing or introducing more than 1,700 words to the English language, often as a result of combining words, changing usages, or blending in foreign root words. If you’ve used the words “downstairs,” “egregious,” “kissing,” “zany,” or “skim milk,” you can thank Shakespeare. He is also responsible for many common phrases, such as “love is blind” and “wild goose chase.”

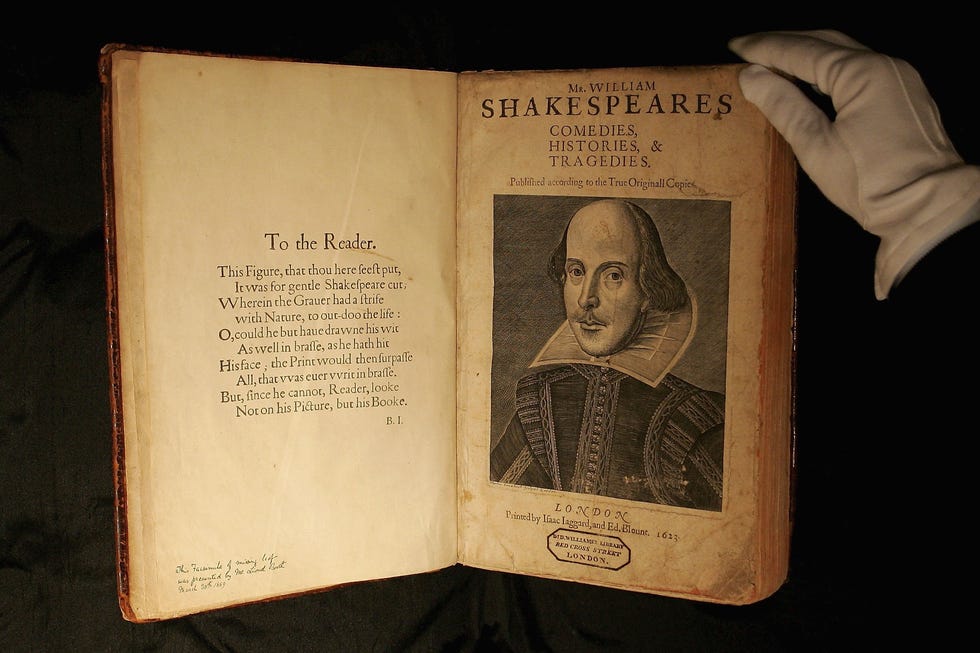

First Folio

Although some of Shakespeare’s works were printed in his lifetime, not all were. It is because of the First Folio that we know about 18 of Shakespeare’s plays, including Macbeth , Twelfth Night , and Julius Caesar . John Heminge and Henry Condell, two of Shakespeare’s friends and fellow actors in the King’s Men, created the 36-play collection, which celebrates its 400 th anniversary this year. It was published with the title Mr. William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories and Tragedies in 1623, seven years after Shakespeare died.

In addition to its literary importance, the First Folio contains an original portrait of Shakespeare on the title page. Engraved by Martin Droeshout, it’s considered one of the two authentic portraits of the writer. The other is a memorial bust at Holy Trinity Church in Stratford.

Today, there are 235 surviving copies of the First Folio that date back to 1623, but experts estimate roughly 750 First Folios were printed. Three subsequent editions of Shakespeare’s Folio, with text updates and additional plays, were published between 1632 and 1685.

Did Shakespeare Write His Own Plays?

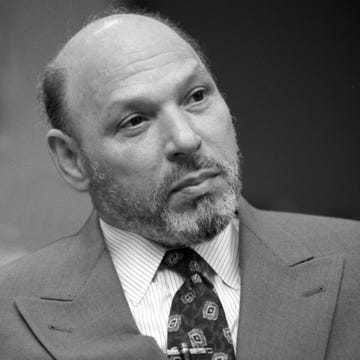

About 150 years after his death, questions arose about the authorship of Shakespeare’s plays. Scholars and literary critics began to float names like Christopher Marlowe, Edward de Vere, and Francis Bacon —men of more known backgrounds, literary accreditation, or inspiration—as the true authors of the plays.

Much of this stemmed from the sketchy details of Shakespeare’s life and the dearth of contemporary primary sources. Official records from the Holy Trinity Church and the Stratford government record the existence of Shakespeare, but none of these attest to him being an actor or playwright.

Skeptics also questioned how anyone of such modest education could write with the intellectual perceptiveness and poetic power that is displayed in Shakespeare’s works. Over the centuries, several groups have emerged that question the authorship of Shakespeare’s plays.

The most serious and intense skepticism began in the 19 th century when adoration for Shakespeare was at its highest. The detractors believed that the only hard evidence surrounding Shakespeare from Stratford-upon-Avon described a man from modest beginnings who married young and became successful in real estate.

Members of the Shakespeare Oxford Society, founded in 1957, put forth arguments that English aristocrat and poet Edward de Vere, the 17 th Earl of Oxford, was the true author of the poems and plays of “William Shakespeare.” The Oxfordians cite de Vere’s extensive knowledge of aristocratic society, his education, and the structural similarities between his poetry and that found in the works attributed to Shakespeare. They contend that Shakespeare had neither the education nor the literary training to write such eloquent prose and create such rich characters.

However, the vast majority of Shakespearean scholars contend that Shakespeare wrote all his own plays. They point out that other playwrights of the time also had sketchy histories and came from modest backgrounds.

They contend that King’s New School in Stratford had a curriculum of Latin and the classics could have provided a good foundation for literary writers. Supporters of Shakespeare’s authorship argue that the lack of evidence about Shakespeare’s life doesn’t mean his life didn’t exist. They point to evidence that displays his name on the title pages of published poems and plays.

Examples exist of authors and critics of the time acknowledging Shakespeare as the author of plays such as The Two Gentlemen of Verona , The Comedy of Errors , and King John .

Royal records from 1601 show that Shakespeare was recognized as a member of the King’s Men theater company and a Groom of the Chamber by the court of King James I, where the company performed seven of Shakespeare’s plays.

There is also strong circumstantial evidence of personal relationships by contemporaries who interacted with Shakespeare as an actor and a playwright.

Literary Legacy

What seems to be true is that Shakespeare was a respected man of the dramatic arts who wrote plays and acted in the late 16 th and early 17 th centuries. But his reputation as a dramatic genius wasn’t recognized until the 19 th century.

Beginning with the Romantic period of the early 1800s and continuing through the Victorian period, acclaim and reverence for Shakespeare and his work reached its height. In the 20 th century, new movements in scholarship and performance rediscovered and adopted his works.

Today, his plays remain highly popular and are constantly studied and reinterpreted in performances with diverse cultural and political contexts. The genius of Shakespeare’s characters and plots are that they present real human beings in a wide range of emotions and conflicts that transcend their origins in Elizabethan England.

- The fool doth think he is wise, but the wise man knows himself to be a fool.

- This above all: to thine own self be true, and it must follow, as the night the day, thou canst not then be false to any man.

- There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.

- Cowards die many times before their deaths; the valiant never taste of death but once.

- Lord, what fools these mortals be!

- To weep is to make less the depth of grief.

- In time we hate that which we often fear.

- Men at some time are masters of their fates: the fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves, that we are underlings.

- What’s done cannot be undone.

- We are such stuff as dreams are made on, and our little life is rounded with a sleep.

- Madness in great ones must not unwatched go.

- The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers.

- All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players.

- Give every man thy ear, but few thy voice.

- I say there is no darkness but ignorance.

- I wasted time, and now doth time waste me.

- Some are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon them.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us !

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Adrienne directs the daily news operation and content production for Biography.com. She joined the staff in October 2022 and most recently worked as an editor for Popular Mechanics , Runner’s World , and Bicycling . Adrienne has served as editor-in-chief of two regional print magazines, and her work has won several awards, including the Best Explanatory Journalism award from the Alliance of Area Business Publishers. Her current working theory is that people are the point of life, and she’s fascinated by everyone who (and every system that) creates our societal norms. When she’s not behind the news desk, find her hiking, working on her latest cocktail project, or eating mint chocolate chip ice cream.

Playwrights

A Huge Shakespeare Mystery, Solved

How Did Shakespeare Die?

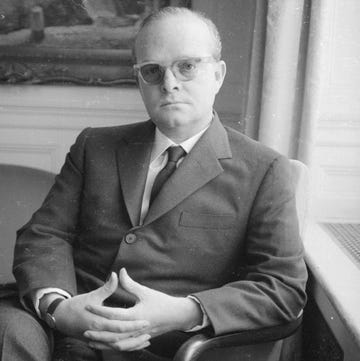

Truman Capote

August Wilson

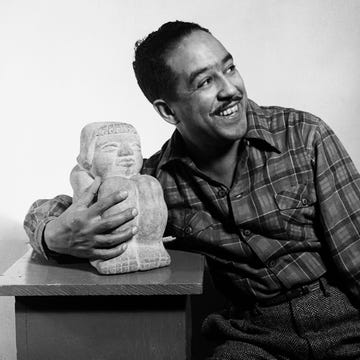

Langston Hughes

7 Facts About Literary Icon Langston Hughes

11 Notable Artists from the Harlem Renaissance

Robert Browning

Christopher Marlowe

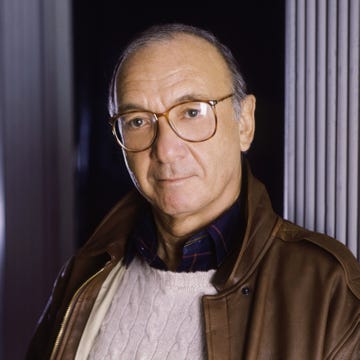

Eugene O'Neill

Share this page

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share on LinkedIn

William Shakespeare Biography

Who was william shakespeare.

- In this section

An Introduction

William Shakespeare was a renowned English poet, playwright, and actor born in 1564 in Stratford-upon-Avon . His birthday is most commonly celebrated on 23 April (see When was Shakespeare born ), which is also believed to be the date he died in 1616.

Shakespeare was a prolific writer during the Elizabethan and Jacobean ages of British theatre (sometimes called the English Renaissance or the Early Modern Period). Shakespeare’s plays are perhaps his most enduring legacy, but they are not all he wrote. Shakespeare’s poems also remain popular to this day.

Shakespeare's Family Life

Records survive relating to William Shakespeare’s family that offer an understanding of the context of Shakespeare's early life and the lives of his family members. John Shakespeare married Mary Arden , and together they had eight children. John and Mary lost two daughters as infants, so William became their eldest child. John Shakespeare worked as a glove-maker, but he also became an important figure in the town of Stratford by fulfilling civic positions. His elevated status meant that he was even more likely to have sent his children, including William, to the local grammar school .

William Shakespeare would have lived with his family in their house on Henley Street until he turned eighteen. When he was eighteen, Shakespeare married Anne Hathaway , who was twenty-six. It was a rushed marriage because Anne was already pregnant at the time of the ceremony. Together they had three children. Their first daughter, Susanna , was born six months after the wedding and was later followed by twins Hamnet and Judith . Hamnet died when he was just 11 years old.

- For an overview of William Shakespeare's life, see Shakespeare's Life: A Timeline

Shakespeare in London

Shakespeare's career jump-started in London, but when did he go there? We know Shakespeare's twins were baptised in 1585, and that by 1592 his reputation was established in London, but the intervening years are considered a mystery. Scholars generally refer to these years as ‘ The Lost Years ’.

During his time in London, Shakespeare’s first printed works were published. They were two long poems, 'Venus and Adonis' (1593) and 'The Rape of Lucrece' (1594). He also became a founding member of The Lord Chamberlain’s Men, a company of actors. Shakespeare was the company's regular dramatist, producing on average two plays a year, for almost twenty years.

He remained with the company for the rest of his career, during which time it evolved into The King’s Men under the patronage of King James I (from 1603). During his time in the company Shakespeare wrote many of his most famous tragedies, such as King Lear and Macbeth , as well as great romances, like The Winter’s Tale and The Tempest .

- For more about Shakespeare's patrons and his work in London see; Shakespeare's Career

Shakespeare's Works

Altogether Shakespeare's works include 38 plays, 2 narrative poems, 154 sonnets, and a variety of other poems. No original manuscripts of Shakespeare's plays are known to exist today. It is actually thanks to a group of actors from Shakespeare's company that we have about half of the plays at all. They collected them for publication after Shakespeare died, preserving the plays. These writings were brought together in what is known as the First Folio ('Folio' refers to the size of the paper used). It contained 36 of his plays, but none of his poetry.

Shakespeare’s legacy is as rich and diverse as his work; his plays have spawned countless adaptations across multiple genres and cultures. His plays have had an enduring presence on stage and film. His writings have been compiled in various iterations of The Complete Works of William Shakespeare, which include all of his plays, sonnets, and other poems. William Shakespeare continues to be one of the most important literary figures of the English language.

New Place; a home in Stratford-upon-Avon

Shakespeare’s success in the London theatres made him considerably wealthy, and by 1597 he was able to purchase New Place , the largest house in the borough of Stratford-upon-Avon . Although his professional career was spent in London, he maintained close links with his native town.

Recent archaeological evidence discovered on the site of Shakespeare’s New Place shows that Shakespeare was only ever an intermittent lodger in London. This suggests he divided his time between Stratford and London (a two or three-day commute). In his later years, he may have spent more time in Stratford-upon-Avon than scholars previously thought.

- Watch our video for more about Shakespeare as a literary commuter:

On his father's death in 1601, William Shakespeare inherited the old family home in Henley Street part of which was then leased to tenants. Further property investments in Stratford followed, including the purchase of 107 acres of land in 1602.

Shakespeare died in Stratford-upon-Avon on 23 April 1616 at the age of 52. He is buried in the sanctuary of the parish church, Holy Trinity.

All the world's a stage /And all the men and women merely players. / They have their exits and their entrances, / And one man in his time plays many parts. — As You Like It, Act 2 Scene 7

Help keep Shakespeare's story alive

More like this, go behind the scenes, shakespeare's birthplace, anne hathaway's cottage, shakespeare's new place.

We use essential and non-essential cookies that improve the functionality and experience of the website. For more information, see our Cookies Policy.

Necessary cookies

Necessary cookies ensure the smooth running of the website, including core functionality and security. The website cannot function properly without these cookies.

Analytics cookies

Analytical cookies are used to determine how visitors are using a website, enabling us to enhance performance and functionality of the website. These are non-essential cookies but are not used for advertising purposes.

Advertising cookies

Advertising cookies help us monitor the effectiveness of our recruitment campaigns as well as enabling advertising to be tailored to you through retargeting advertising services. This means there is the possibility of you seeing more adverts from the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust on other websites that you visit.

- Save settings Minimise

Website navigation

Welcome to the folger.

Enjoy great stories | Explore what makes you curious | Share the best in art, history, and literature with friends and family at the world’s largest Shakespeare collection.

The Folger is open! New exhibition galleries, gardens, and shop

Things to do and see this summer

Explore our exhibitions

See what’s on view in our galleries.

Plan your visit

Get details and reserve timed-entry passes.

Check out our shop

Gifts, games, merch, and more!

What’s on

Join us for in-person and virtual events: theater, poetry, music, and more.

Neurodivergent/All Abilities Dance Class

Hip-hop and spoken word, folger pop-up book fair 2024, cultural literacy through puppets, cuban salsa night, folger book club: birnam wood by eleanor catton, youth poetry workshop, queer culture night, dance theatre workshop, news and announcements, folger shakespeare library names dr. farah karim-cooper as director.

Press release: May 20, 2024

How did the world’s largest Shakespeare collection end up one block from the US Capitol? Explore the Folger’s origin story.

The latest from our blogs and podcast

Michael witmore on serving as director and the renovation.

Michael Witmore talks about his experiences as Folger director and the recent Folger grand reopening.

Ovid, Shakespeare, and 'The Latinist' (Part Two)

The second part of the opening conversation between emma poltrack and Dr. Will Tosh as part of the June 2024 discussion of Mark Prins’s The Latinist.

“Speak what terrible language you will”: Shakespeare and TikTok

Austin Tichenor on whether TikTok, like Shakespeare, is adding new words and phrases.

Order It: "Sermons in stones" from As You Like It

Shakespeare’s phrase “sermons in stones” is from a speech in As You Like It. Take this quiz to see if you can correctly order the lines.

14 Shakespeare Quotes About New Beginnings

As the Folger prepares to reopen, we turn to Shakespeare’s plays for quotations about new beginnings and fresh starts.

A Tour of the Newly-Reopened Folger | Part 1

Join Shakespeare Unlimited host Barbara Bogaev on a personal tour of the Folger’s newly-renovated public spaces, opening June 21.

Our collection

The first folio.

The Folger has the world’s largest collection of First Folios. Learn more about the book that gave us Shakespeare.

A majestic portrait

The Folger collection includes about 200 paintings. This portrait of Queen Elizabeth I by George Gower is dated 1579, making it the oldest painting in our collection. Two years after he completed this portrait, Gower became Serjeant Painter to the Queen, making him the most important artist in England.

Our other Elizabeth I holdings include hand-signed letters, books, and even New Year’s gift rolls detailing her holiday gifts. It is the largest collection of Elizabeth I materials in North America.

View more collection highlights

Shakespeare’s works

View the full list of plays and poems to read, search, and download our bestselling editions of Shakespeare’s works.

See all the plays and poems

Shakespeare’s most popular plays

Romeo and juliet, a midsummer night's dream, julius caesar, what was shakespeare's theater like.

Learn about the Globe and other London playhouses where Shakespeare’s company performed. What was it like to be an actor there, or an audience member?

How can Shakespeare help 21st-century students be stronger readers?

Our Folger Method is revolutionizing how not just Shakespeare but all literature is taught using strategies that allow all students to own – and enjoy – complex texts.

If we are what we eat, what can recipes from the past tell us?

Projects like Before ‘Farm to Table’ unite scholars and practitioners in investigations into the past to shed light on what matters to us today.

Support the things you love

Your gifts make access to our collection, learning opportunities, and exciting experiences happen.

Become a member

Stay connected

Find out what’s on, read our latest stories, and learn how you can get involved.

- Poem Guides

- Poem of the Day

- Collections

- Harriet Books

- Featured Blogger

- Articles Home

- All Articles

- Podcasts Home

- All Podcasts

- Glossary of Poetic Terms

- Poetry Out Loud

- Upcoming Events

- All Past Events

- Exhibitions

- Poetry Magazine Home

- Current Issue

- Poetry Magazine Archive

- Subscriptions

- About the Magazine

- How to Submit

- Advertise with Us

- About Us Home

- Foundation News

- Awards & Grants

- Media Partnerships

- Press Releases

- Newsletters

William Shakespeare

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Print this page

- Email this page

While William Shakespeare’s reputation is based primarily on his plays, he became famous first as a poet. With the partial exception of the Sonnets (1609), quarried since the early 19th century for autobiographical secrets allegedly encoded in them, the nondramatic writings have traditionally been pushed to the margins of the Shakespeare industry. Yet the study of his nondramatic poetry can illuminate Shakespeare’s activities as a poet emphatically of his own age, especially in the period of extraordinary literary ferment in the last ten or twelve years of the reign of Queen Elizabeth.

Shakespeare’s exact birth date remains unknown. He was baptized in Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-upon-Avon on April 26, 1564, his mother’s third child, but the first to survive infancy. This has led scholars to conjecture that he was born on April 23rd, given the era’s convention of baptizing newborns on their third day. Shakespeare’s father, John Shakespeare, moved to Stratford in about 1552 and rapidly became a prominent figure in the town’s business and politics. He rose to be bailiff, the highest official in the town, but then in about 1575-1576 his prosperity declined markedly and he withdrew from public life. In 1596, thanks to his son’s success and persistence, he was granted a coat of arms by the College of Arms, and the family moved into New Place, the grandest house in Stratford.

Speculation that William Shakespeare traveled, worked as a schoolmaster in the country, was a soldier and a law clerk, or embraced or left the Roman Catholic Church continues to fill the gaps left in the sparse records of the so-called lost years. It is conventionally assumed (though attendance registers do not survive) that Shakespeare attended the King’s New School in Stratford, along with others of his social class. At the age of 18, in November 1582, he married Anne Hathaway, daughter of a local farmer. She was pregnant with Susanna Shakespeare, who was baptized on May 26, 1583. The twins, Hamnet and Judith Shakespeare, were baptized on February 2, 1585. There were no further children from the union.

William Shakespeare had probably been working as an actor and writer on the professional stage in London for four or five years when the London theaters were closed by order of the Privy Council on June 23, 1592. The authorities were concerned about a severe outbreak of the plague and alarmed at the possibility of civil unrest (Privy Council minutes refer to “a great disorder and tumult” in Southwark). The initial order suspended playing until Michaelmas and was renewed several times. When the theaters reopened in June 1594, the theatrical companies had been reorganized, and Shakespeare’s career was wholly committed to the troupe known as the Lord Chamberlain’s Men until 1603, when they were reconstituted as the King’s Men.

By 1592 Shakespeare already enjoyed sufficient prominence as an author of dramatic scripts to have been the subject of Robert Greene’s attack on the “upstart crow” in Greene’s Groatsworth of Wit . Such renown as he enjoyed, however, was as transitory as the dramatic form. Play scripts, and their authors, were accorded a lowly status in the literary system, and when scripts were published, their link to the theatrical company (rather than to the scriptwriter) was publicized. It was only in 1597 that Shakespeare’s name first appeared on the title page of his plays— Richard II and a revised edition of Romeo and Juliet .

While the London theaters were closed, some actors tried to make a living by touring outside the capital. Shakespeare turned from the business of scriptwriting to the pursuit of art and patronage; unable to pursue his career in the theatrical marketplace, he adopted a more conventional course. Shakespeare’s first publication, Venus and Adonis (1593), was dedicated to the 18-year-old Henry Wriothesley, third Earl of Southampton. The dedication reveals a frank appeal for patronage, couched in the normal terms of such requests. Shakespeare received the Earl’s patronage and went on to dedicate his next dramatic poem, Lucrece, to the young lord as well. Venus and Adonis was printed by Richard Field, a professionally accomplished printer who lived in Stratford. Shakespeare’s choice of printer indicates an ambition to associate himself with unambiguously high-art productions, as does the quotation from Ovid’s Amores on the title page: “Vilia miretur vulgus: mihi flavus Apollo / Pocula Castalia plena ministret acqua” (Let worthless stuff excite the admiration of the crowd: as for me, let golden Apollo ply me with full cups from the Castalian spring, that is, the spring of the Muses). Such lofty repudiation of the vulgar was calculated to appeal to the teenage Southampton. It also appealed to a sizable slice of the reading public. In the midst of horror, disease, and death, Shakespeare was offering access to a golden world, showing the delights of applying learning for pleasure rather than pointing out the obvious morals to be drawn from classical authors when faced with awful catastrophe.

With Venus and Adonis Shakespeare sought direct aristocratic patronage, but he also entered the marketplace as a professional author. He seems to have enjoyed a degree of success in the first of these objectives, given the more intimate tone of the dedication of Lucrece to Southampton in the following year. In the second objective, his triumph must have outstripped all expectation. Venus and Adonis went though 15 editions before 1640; if was first entered in the Stationers’ Register on April 18, 1593. It is a fine and elegantly printed book, consisting of 1,194 lines in 199 six-line stanzas rhymed ababcc . The verse form was a token of social and literary ambition on Shakespeare’s part. Its aristocratic cachet derived from its popularity at court, being favored by several courtier poets, such as Sir Walter Ralegh , Sir Arthur Gorges , and Sir Edward Dyer . Venus and Adonis is unquestionably a work of its age. In it a young writer courts respectability and patronage. At one level, of course, the poem is a traditional Ovidian fable, locating the origin of the inseparability of love and sorrow in Venus’s reaction to the death of Adonis: “lo here I prophesy, / Sorrow on love hereafter shall attend /... all love’s pleasure shall not match his woe.” It invokes a mythic past that explains a painful present. Like so many texts of the 1590s, it features an innocent hero, Adonis, who encounters a world in which the precepts he has acquired from his education are tested in the surprising school of experience. His knowledge of love, inevitably, is not firsthand (“I have heard it is a life in death, / That laughs and weeps, and all but with a breath”). There is a staidly academic quality to his repudiation of Venus’s “treatise,” her “idle over-handled theme.

Shakespeare’s literary and social aspirations are revealed at every turn. In his Petrarchism, for example, he adopts a mode that had become a staple of courtly discourse. Elizabethan politicians figured themselves and their personal and political conditions in Petrarchan terms. The inescapable and enduring frustrations of the courtier’s life were habitually figured via the analogy of the frustrated, confused, but devoted Petrarchan lover. Yet Shakespeare’s approach to this convention typifies the 1590s younger generation’s sense of its incongruity. Lines such as “the love-sick queen began to sweat” are understandably rare in Elizabethan courtly discourse. Power relations expressed through the gendered language of Elizabeth’s eroticized politics are reversed: “Her eyes petitioners to his eyes suing / ... Her eyes wooed still, his eyes disdain’d the wooing.” It is Venus who deploys the conventional carpe diem arguments: “Make use of time / ... Fair flowers that are not gath’red in their prime, / Rot, and consume themselves in little time”; she even provides a blason of her own charms: “Thou canst not see one wrinkle in my brow, / Mine eyes are grey, and bright, and quick in turning.”

Like most Elizabethan treatments of love, Shakespeare’s work is characterized by paradox (“She’s love, she loves, and yet she is not lov’d”), by narrative and thematic diversity, and by attempts to render the inner workings of the mind, exploring the psychology of perception (“Oft the eye mistakes, the brain being troubled”). The poem addresses such artistic preoccupations of the 1590s as the relation of poetry to painting and the possibility of literary immortality, as well as social concerns such as the phenomenon of “masterless women,” and the (to men) alarming and unknowable forces unleashed by female desire, an issue that for a host of reasons fascinated Elizabeth’s subjects. Indeed, Venus and Adonis flirts with taboos, as do other successful works of the 1590s, offering readers living in a paranoid, plague-ridden city a fantasy of passionate and fatal physical desire, with Venus leading Adonis “prisoner in a red-rose chain.” In its day it was appreciated as an erotic fantasy glorying in the inversion of established categories and values, with a veneer of learning and the snob appeal of association with a celebrated aristocrat.

Since the Romantic period the frank sexuality of Shakespeare’s Venus has held less appeal for literary critics and scholars than it had to Elizabethan and Jacobean readers. C.S. Lewis concludes in English Literature in the Sixteenth Century, Excluding Drama (1954) that “if the poem is not meant to arouse disgust it was very foolishly written.” In more recent years a combination of feminism, cultural studies, renewed interest in rhetoric, and a return to traditional archival research has begun to reclaim Venus and Adonis from such prejudice.

The elevated subject of Shakespeare’s next publication, Lucrece , suggests that Venus and Adonis had been well received, Lucrece comprises 1,855 lines, in 265 stanzas. The stanza (as in Complaint of Rosamund ) is the seven-line rhyme royal ( ababbcc ) immortalized in Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde (circa 1385) and thereafter considered especially appropriate for tragedy, complaint, and philosophical reflection. In places the narrator explicitly highlights the various rhetorical set pieces (“Here she exclaims against repose and rest”). Lucrece herself comments on her performance after the apostrophes to “comfort-killing Night, image of Hell,” Opportunity, and Time. Elizabethan readers would have appreciated much about the poem, from its plentiful wordplay (“to shun the blot, she would not blot the letter”; “Ere she with blood had stain’d her stain’d excuse”) and verbal dexterity, to the inner debate raging inside Tarquin. Though an exemplary tyrant from ancient history, he also exemplifies the conventional 1590s conflict between willful youthful prodigality and sententious experience (“My part is youth, and beats these from the stage”). The arguments in his “disputation / ‘Tween frozen conscience and hot burning will” are those of the Petrarchan lover: “nothing can affection’s course control,” and “Yet strive I to embrace mine infamy.” But the context of this rhetorical performance is crucial throughout. Unlike Venus and Adonis , Lucrece is not set in a mythical golden age, but in a fallen, violent world. This is particularly apparent in the rhetorical and ultimately physical competition of their debate--contrasting Tarquin’s speeches with Lucrece’s eloquent appeals to his better nature.

The combination of ancient and contemporary strengthens the political elements in the poem. It demonstrates tyranny in its most intimate form, committing a private outrage that is inescapably public; hence the rape is figured in terms both domestic (as a burglary) and public (as a hunt, a war, a siege). It also reveals the essential violence of many conventional erotic metaphors. Shakespeare draws on the powerful Elizabethan myth of the island nation as a woman: although Tarquin is a Roman, an insider, his journey from the siege of Ardea to Lucrece’s chamber connects the two assaults. His attack figures a society at war with itself, and he himself is shown to be self-divided.” Tyranny, lust, and greed translate the metaphors of Petrarchism into the actuality of rape, which is figured by gradatio , or climax: “What could he see but mightily he noted? / What did he note but strongly he desired?”

The historically validated interpretation—for Shakespeare’s readers, descendants of Brutus in New Troy—is figured by Brutus, who “pluck’d the knife from Lucrece’s side.” He steps forward, casting off his reputation for folly and improvising a ritual (involving kissing the knife) that transforms grief and outrage at Lucrece’s death into a determination to “publish Tarquin’s foul offense” and change the political system. Brutus emerges from the shadows, reminding the reader that the poem, notwithstanding its powerful speeches and harrowing images, is also remarkable for what is unshown, untold, implicit. Until recently few commentators have taken up the interpretative challenge posed by Brutus. Traditionally Lucrece has been dismissed as a bookish, pedantic dry run for Shakespeare’s tragedies, in William Empson ‘s phrase, “the Bard doing five-finger exercises,” containing what F.T. Prince in his 1960 edition of the poems dismisses as defective rhetoric in the treatment of an uninteresting story. Many critics have sought to define the poem’s genre, which combines political fable, female complaint, and tragedy within a milieu of self-conscious antiquity. But perhaps the most significant recent developments have been the feminist treatments of the poem, the reawakening interest in rhetoric, and a dawning awareness of the work’s political engagement. Lucrece , like so many of Shakespeare’s historical tragedies, problematizes the categories of history and myth, of public and private, and exemplifies the bewildering nature of historical parallels. The self-conscious rhetorical display and the examination of representation is daringly politicized, explicitly, if inconclusively, connecting the aesthetic and the erotic with politics both sexual and state. At the time of its publication, Lucrece was Shakespeare’s most profound meditation on history, particularly on the relations between public role and private morality and on the conjunction of forces—personal, political, social—that creates turning points in human history. In it he indirectly articulates the concerns of his generation and also, perhaps, of his young patron, who was already closely associated with the doomed earl of Essex.

In 1598 or 1599 the printer William Jaggard brought out an anthology of 20 miscellaneous poems, which he eventually attributed to Shakespeare, though the authorship of all 20 is still disputed. At least five are demonstrably Shakespearean. Poem 1 is a version of Sonnet 138 (“When My Love Swears that She Is Made of Truth”), poem 2 of Sonnet 144 (“Two Loves I Have, of Comfort and Despair”), and the rest are sonnets that appear in act 4 of Love’s Labor’s Lost (1598). Investigation of Jaggard’s volume, called The Passionate Pilgrime, has yielded and will continue to yield insight into such matters as the relationship of manuscript to print culture in the 1590s, the changing nature of the literary profession, and the evolving status of the author. It may also, as with The Phoenix and Turtle (1601), lead to increased knowledge of the chronology and circumstances of Shakespeare’s literary career, as well as affording some glimpses of his revisions of his texts.

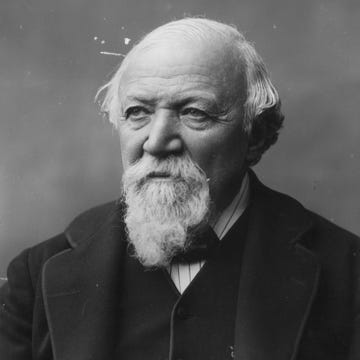

“With this key / Shakespeare unlocked his heart,” wrote William Wordsworth in “ Scorn not the Sonnet “ (1827) of the Sonnets . “If so,” replied Robert Browning in his poem “House” (1876), “the less Shakespeare he.” None of Shakespeare’s works has been so tirelessly ransacked for biographical clues as the 154 sonnets, published with A Lover’s Complaint by Thomas Thorpe in 1609. Unlike the narrative poems, they enjoyed only limited commercial success during Shakespeare’s lifetime, and no further edition appeared until Benson’s in 1640. The title page, like Jaggard’s of The Passionate Pilgrim , relies upon the drawing power of the author’s name and promises “SHAKE-SPEARES / SONNETS / Never before Imprinted.”

The 154 sonnets are conventionally divided between the “young man” sonnets (1-126) and the “dark lady” sonnets (127-152), with the final pair often seen as an envoy or coda to the collection. There is no evidence that such a division has chronological implications, though the volume is usually read in such a way. Shakespeare employs the conventional English sonnet form: three quatrains capped with a couplet. Drama is conjured within individual poems, as the speaker wrestles with some problem or situation; it is generated by the juxtaposition of poems, with instant switches of tone, mood, and style; it is implied by cross-references and interrelationships within the sequence as a whole.

There remains a question, however, of how closely Shakespeare was involved in preparing the text of the sonnets for publication. Some commentators have advocated skepticism about all attempts to recover Shakespeare’s intention. Others have looked more closely at Thorpe, at Benson, and at the circulation of Shakespeare’s verse in the manuscript culture: these investigations have led to a reexamination of the ideas of authorship and authority in the period. Although scholarly opinion is still divided, several influential studies and editions in recent years have argued, on a variety of grounds, for the authority, integrity, and coherence of Thorpe’s text, an integrity now regarded as including A Lover’s Complaint .

The subsequent history of the text of the sonnets is inseparable from the history of Shakespeare’s reputation. John Benson’s Poems: Written by Wil. Shake-speare. Gent (1640) was part of an attempt to “canonize” Shakespeare, collecting verses into a handsome quarto that could be sold as a companion to the dramatic folio texts (“to be serviceable for the continuance of glory to the deserved author in these his poems”). Benson dropped a few sonnets, added other poems, provided titles for individual pieces, changed Thorpe’s order, conflated sonnets, and modified some of the male pronouns, thereby making the sequence seem more unambiguously heterosexual in its orientation. In recent years there has been increasing study of Benson’s edition as a distinct literary production in its own right.

The Romantic compulsion to read the sonnets as autobiography inspired attempts to rearrange them to tell their story more clearly. It also led to attempts to relate them to what was known or could be surmised about Shakespeare’s life. Some commentators speculated that the publication of the sonnets was the result of a conspiracy by Shakespeare’s rivals or enemies, seeking to embarrass him by publishing love poems apparently addressed to a man rather than to the conventional sonnet-mistress. The five appendices to Hyder Edward Rollins’s Variorum edition document the first century of such endeavors. Attention was directed toward “problems” such as the identity of Master W. H., of the young man, of the rival poet, and of the dark lady (a phrase, incidentally, never used by Shakespeare in the sonnets). The disappearance of the sonnets from the canon coincided with the time when Shakespeare’s standing as the nation’s bard was being established. The critics’ current fascination is just as significant for what it reveals about contemporary culture, as the “Shakespeare myth” comes under attack from various directions.

The sonnets were apparently composed during a period of ten or a dozen years starting in about 1592-1593. In Palladis Tamia Meres refers to the existence of “sugared sonnets” circulating among Shakespeare’s “private friends,” some which were published in The Passionate Pilgrim. The fact of prior circulation has important implications for the sonnets. The particular poems that were in circulation suggest that the general shape and themes of the Sonnets were established from the earliest stages. Evidence suggesting a lengthy period of composition is inconvenient for commentators seeking to unlock the autobiographical secret of the sonnets. An early date (1592-1594) argues for Southampton as the boy and Christopher Marlowe as the rival poet; a date a decade later brings George Herbert and George Chapman into the frame. There are likewise early dark ladies (Lucy Negro, before she took charge of a brothel) and late (Emilia Lanier, Mary Fitton). There may, of course, have been more than one young man, rival, and dark lady, or in fact the sequence may not be autobiographical at all.

No Elizabethan sonnet sequence presents an unambiguous linear narrative, a novel in verse. Shakespeare’s is no exception. Yet neither are the Sonnets a random anthology, a loose gathering of scattered rhymes. While groups of sonnets are obviously linked thematically, such as the opening sequence urging the young man to marry (1-17), and the dark lady sequence (127-152), the ordering within those groups is not that of continuous narrative. There are many smaller units, with poems recording that the friend has become the lover of the poet’s mistress (40-42), or expressing jealousy of the young man’s friendship with a rival poet (78-86). Sonnet 44 ends with a reference to two of the four elements “so much of earth and water wrought,” and 45 starts with “The other two, slight air and purging fire.” Similarly indivisible are the two “horse” sonnets 50 and 51, the “Will” sonnets 135 and 136, and 67 and 68. Sonnets 20 and 87 are connected as much by their telling use of feminine rhyme as by shared themes. Dispersed among the poems are pairs and groups that amplify or comment on each other, such as those dealing with absence (43-45, 47-48, 50-52, and 97-98).

“My name is Will,” declares the speaker of 136. Sonnet 145 apparently puns on Anne Hathaway’s name (“I hate, from hate away she threw”). Elizabethan sonneteers, following Sir Philip Sidney , conventionally teased their readers with hints of an actuality behind the poems. Sidney had given Astrophil his own coat of arms, had quibbled with the married name of the supposed original for Stella (Penelope Rich) and with the Greek etymology of his own name (Philip, “lover of horses”) in Astrophil and Stella sonnets 41, 49, and 53. Shakespeare’s speaker descends as much from Astrophil as from Daniel’s more enigmatic persona, most obviously in the deployment of the multiple sense of will in 135 and 136. Yet Shakespeare’s sequence is unusual in including sexual consummation (Spenser’s Amoretti led to the celebration of marriage in Epithalamion , 1595) and unique in its persuasion to marry. There is evidence that some contemporary readers were disturbed by the transgressive and experimental features of 1590s erotic writing. Works by Marston and Marlowe were among those banned in 1599 along with satires and other more conventional kindling. Benson’s much-discussed modification of the text of the Sonnets indicates at least a certain level of anxiety about the gender of the characters in the poems. Benson retained Sonnet 20 but dropped 126 (“O Thou My Lovely Boy”) and changed the direct address of 108 (“Nothing, Sweet Boy”) to the neutral “Nothing, Sweet Love.”

The speaker sums up his predicament in 144, one of the Passionate Pilgrim poems:

Two loves I have of comfort and despair, Which like two spirits do suggest me still: The better angel is a man right fair, The worser spirit a woman color’d ill.

The speaker’s attraction to the “worser spirit” is figured in harsh language throughout the sequence: in fact, the brutal juxtaposition of lyricism and lust is characteristic of the collection as a whole. The consequent disjointedness expresses a form of psychological verisimilitude by the standards of Shakespeare’s day, where discontinuity and repetition were held to reveal the inner state of a speaker.

The anachronism of applying modern attitudes toward homosexuality to early modern culture is self-evident. Where Shakespeare and his contemporaries drew their boundaries cannot be fully determined, but they were fascinated by the Platonic concept of androgyny, a concept drawn on by the queen herself almost from the moment of her accession. Sonnet 53 is addressed to an inexpressible lover, who resembles both Adonis and Helen. Androgyny is only part of the exploration of sexuality in the sonnets, however. A humanist education could open windows onto a world very different from post-Reformation England. Plato’s praise of love between men was in marked contrast to the establishment of capital punishment as the prescribed penalty for sodomy in 1533.

In the Sonnets the relationship between the speaker and the young man both invites and resists definition, and it is clearly presented as a challenge to orthodoxy. If at times it seems to correspond to the many Elizabethan celebrations of male friendship, at others it has a raw physicality that resists such polite categorization. Even in sonnet 20, where sexual intimacy seems to be explicitly denied, the speaker’s mind runs to bawdy puns. The speaker refers to the friend as “rose,” “my love,” “lover,” and “sweet love,” and many commentators have demonstrated the repeated use of explicitly sexual language to the male friend (in 106, 109, and 110, for example). On the other hand, the acceptance of the traditional distinction between the young man and the dark lady sonnets obscures the fact that Shakespeare seems deliberately to render the gender of his subject uncertain in the vast majority of cases.

For some commentators the sequence also participates in the so-called birth of the author, a crucial feature of early modern writing: the liberation of the writer from the shackles of patronage. In Joel Fineman’s analysis, Shakespeare creates a radical internalization of Petrarchism, reordering its dynamic by directing his attention to the speaker’s subjectivity rather than to the ostensible object of the speaker’s devotion: the poetry of praise becomes poetry of self-discovery.

Sidney’s Astrophil had inhabited a world of court intrigue, chivalry, and international politics, exemplifying the overlap between political and erotic discourse in Elizabethan England. The circumstances of Shakespeare’s speaker, in contrast, are not those of a courtier but of a male of the upwardly mobile “middling sort.” Especially in the young man sonnets, there is a marked class anxiety, as the speaker seeks to define his role, whether as a friend, a tutor, a counselor, an employee, or a sexual rival. Not only are comparisons drawn from the world of the professional theater (“As an unperfect actor on the stage” in sonnet 23), but also from the world of business: compared to the prodigal “Unthrifty loveliness” of the youth (sonnet 4), “Making a famine where abundance lies” (1), the speaker inhabits a bourgeois world of debts, loans, repayment, and usury, speaking in similar language to the Dark Lady: “I myself am mortgaged to thy will” (134).

Yet Shakespeare’s linguistic performance extends beyond the “middling sort.” He was a great popularizer, translating court art and high art—John Lyly, Sidney, Edmund Spenser —into palatable and sentimental commercial forms. His sequence is remarkable for its thematic and verbal richness, for its extraordinary range of nuances and ambiguities. He often employs words in multiple senses (as in the seemingly willfully indecipherable resonance, punning, polysemy, implication, and nuance of sonnet 94). Shakespeare’s celebrated verbal playfulness, the polysemy of his language, is a function of publication, whether by circulation or printing. His words acquire currency beyond himself and become the subject of reading and interpretation.

This linguistic richness can also be seen as an act of social aspiration: as the appropriation of the ambiguity axiomatically inherent in courtly speech. The sequence continues the process of dismantling traditional distinctions among rhetoric, philosophy, and poetry begun in the poems of 1593-1594. The poems had dealt in reversal and inversion and had combined elements of narrative and drama. The Sonnets occupy a distinct, marginal space between social classes, between public and private, narrative and dramatic, and they proceed not through inverting categories but rather through interrogating them. Variations are played on Elizabethan conventions of erotic discourse: love without sex, sex without love, a “master-mistress” who is “prick’d ... out for women’s pleasure” as the ultimate in unattainable (“to my purpose nothing,” 20) adoration. Like Spenser’s Amoretti , Shakespeare’s collection meditates on the relationships among love, art, time, and immortality. It remains a meditation, however, even when it seems most decided.

The consequences of love, the pain of rejection, desertion, and loss of reputation are powerful elements in the poem that follows the sequence. Despite Thorpe’s unambiguous attribution of the piece to Shakespeare, A Lover’s Complaint was rejected from the canon, on distinctly flimsy grounds, until quite recently. It has been much investigated to establish its authenticity and its date. It is now generally accepted as Shakespearean and dated at some point between 1600 and 1609, possibly revised from a 1600 first version for publication in Thorpe’s volume. The poem comprises 329 lines, disposed into 47 seven-line rhyme-royal stanzas. It draws heavily on Spenser and Daniel and is the complaint of a wronged woman about the duplicity of a man. It is in some sense a companion to Lucrece and to All’s Well That Ends Well (circa 1602-1603) as much as to the sonnets. Its connections with the narrative poems, with the plays, and with the genre of female complaint have been thoroughly explored. The woman is a city besieged by an eloquent wooer (“how deceits were gilded in his smiling”), whose essence is dissimulation (“his passion, but an art of craft”). There has been a growing tendency to relate the poem to its immediate context in Thorpe’s Sonnets volume and to find it a reflection or gloss or critique of the preceding sequence.

Interest in Shakespeare’s nondramatic writings has increased markedly in recent years. They are no longer so easily marginalized or dismissed as conventional, and they contribute in powerful ways to a deeper understanding of Shakespeare’s oeuvre and the Elizabethan era in which he lived and wrote.

Shakespeare died on April 23, 1616, on what may have been his 52nd birthday.

The Phoenix and the Turtle

From the rape of lucrece, song: “ blow, blow, thou winter wind ”.

- See All Poems by William Shakespeare

Anti-Love Poems

Poems of anxiety and uncertainty, poems for retirement, common core state standards text exemplars, bottom's dream, esther belin in conversation with a. van jordan, evie shockley vs gathering, hang there, my verse, love looks not with the eyes.

- A Deeper Consideration

Dig It Up Again

From the archive: harriet monroe on shakespeare, "gabble like a thing most brutish".

- See All Related Content

- Renaissance

- Poems by This Poet

Bibliography