Find Study Materials for

- Explanations

- Business Studies

- Combined Science

- Computer Science

- Engineering

- English literature

- Environmental Science

- Human Geography

- Macroeconomics

- Microeconomics

- Social Studies

- Browse all subjects

- Textbook Solutions

- Read our Magazine

Create Study Materials

- Flashcards Create and find the best flashcards.

- Notes Create notes faster than ever before.

- Study Sets Everything you need for your studies in one place.

- Study Plans Stop procrastinating with our smart planner features.

Chapter 9: Problem 22

World Population Growth. The world population is projected to be 9.4 billion in \(2050 .\) At that time, there is expected to be approximately 3.5 billion more people in Asia than in Africa. The population for the rest of the world will be approximately 0.3 billion less than two-fifths the population of Asia. Find the projected populations of Asia, Africa, and the rest of the world in \(2050 .\)

Short answer, step by step solution, title - define variables, title - set up equations, title - substitute and simplify equations, title - solve for africa's population (b), title - solve for asia's population (a), title - solve for rest of the world population (c), key concepts.

These are the key concepts you need to understand to accurately answer the question.

algebraic equations

Variable substitution, population projections, problem-solving steps, one app. one place for learning..

All the tools & learning materials you need for study success - in one app.

Most popular questions from this chapter

A collection of 43 coins consists of dimes and quarters. The total value is \(\$ 7.60 .\) How many dimes and how many quarters are there?

Find the domain of \(f\) $$ f(x)=\frac{3 x}{x^{2}+1} $$

For Exercises 52 and \(53,\) let u represent \(1 / x,\) v represent \(1 / y,\) and \(w\) represent \(1 / z .\) Solve for \(u, v,\) and \(w,\) and then solve for \(x, y,\) and \(z\). $$\begin{aligned} &\frac{2}{x}+\frac{2}{y}-\frac{3}{z}=3,\\\ &\frac{1}{x}-\frac{2}{y}-\frac{3}{z}=9,\\\ &\frac{7}{x}-\frac{2}{y}+\frac{9}{z}=-39 \end{aligned}$$

Solve each system. If a system’s equations are dependent or if there is no solution, state this. $$\begin{aligned} x \quad \quad+z &=0 ,\\\ x+y+2 z &=3 ,\\\ y+ \quad z &=2 \end{aligned}$$

To prepare for Section \(9.5,\) review functions (Sections 3.8 and \(5.9)\) Find each of the following, given \(f(x)=80 x+2500\) and \(g(x)=150 x\) $$ (g-f)(10)[5.9] $$

Recommended explanations on Math Textbooks

Theoretical and mathematical physics, decision maths, logic and functions, applied mathematics, mechanics maths.

What do you think about this solution?

We value your feedback to improve our textbook solutions.

Study anywhere. Anytime. Across all devices.

Privacy overview.

Practice Problem: What Goes Up…Must Come Down?

Here’s a recording of the January 2024 webinar where the problem author and former M3 Challenge participant discussed strategies for answer addressing this question and tips for success in competing in M3 Challenge.

The world population has quadrupled in just the past 100 years, from under 2 billion people in 1923 to nearly 8 billion today [1]. This same period saw vast economic growth and scientific advances—including improved healthcare—which increased life expectancy and decreased infant mortality rates across the world [2]. These positive outcomes, however, have contributed to a growing human population that has strained the earth’s natural resources, contributed to conflict in some parts of the world, and led to increased pollution and habitat destruction [3,4].

More recently the rate of the world’s population growth has slowed, partially due to economic factors like the cost of childcare, and social factors like women choosing to start having children later [5]. In fact, several countries across Europe and Asia are beginning to see population decline . Recently, the world’s second most populous country, China, reported its first year of population decline since the Great Chinese Famine in the 1960s [6]. Many experts predict that other countries will soon follow a similar trend and that the global population could begin to decline within the next one hundred years.

Just as population growth led to both positive and negative impacts, so could a decline in population. For example, the possibility of reduced stress on the earth’s environment would be a welcomed outcome, while the potential economic challenges of supporting an aging population without a young workforce is a concern [5]. Your task is to use mathematical modeling to better understand the potential issues surrounding a possible decline in the global population.

Q1. Boom…or bust? Create a model that predicts the global population as far as you can into the future. Quantify your level of confidence in your predictions. You may wish to incorporate into your model data on historical changes in the world population, as well as trends in global fertility and mortality rates. Such data is widely available online.

Q2. Change is good…or bad? Create a model that quantifies potential impacts of global population change. Include at least one positive impact and one negative impact. You may consider some of the impacts discussed above, or other possible impacts.

Q3. Act fast…or not at all? Countries regularly enact policies that have the potential to impact population growth and/or decline. For example, politicians in both the U.K. and U.S. are considering measures to reduce the cost of raising children [7,8], which could increase population growth rates. Develop a model or models to make informed recommendations about how, when, and if leaders should respond to the possible onset of human population decline.

[1] US Census International Database. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/international-programs/about/idb.html

[2] Population Growth, Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Population_growth

[3] Population and environment: a global challenge. https://www.science.org.au/curious/earth-environment/population-environment

[4] A Climate Warning from the Cradle of Civilization https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/29/world/middleeast/iraq-water-crisis-desertification.html

[5] Long Slide Looms for World Population, With Sweeping Ramifications, New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/22/world/global-population-shrinking.html

[6] China’s first population drop in six decades sounds alarm on demographic crisis. https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-population-shrinks-first-time-since-1961-2023-01-17

[7] Children’s Defense Fund’s Statement on the American Family Act of 2023. https://www.childrensdefense.org/blog/childrens-defense-funds-statement-on-the-american-family-act-of-2023/

[8] Britain sets out plans to bring down cost of childcare. https://www.reuters.com/world/uk/britain-extends-free-childcare-get-parents-working-more-2023-03-15/

Problem Author: former M3 Challenge participant Dr. Christopher Musco , Assistant Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, New York University

Reference and other links included on this page were current and valid at time of original posting; if they are no longer valid or live please look for similar or updated links in context with the referenced topic.

Recent Practice Problems

Practice problem: subscribe today, practice problem: seas the day order the lobster, practice problem: something smells…spongy, practice problem: modeling disease spread, containment, and prevention.

See All Practice Problems

Connect With Us

Recent news.

Andover Students Land Top Spot in Prestigious International Math Competition

Nearly Half High School Students Say Generative AI will Significantly Change the Future Workforce, Global Survey Reveals

The Answer to the Housing and Homeless Crises? Teens Offer Creative Ideas

MathWorks Math Modeling Challenge Registration is Open

- Why Overpopulation Is a Serious Concern All over…

Why Overpopulation Is a Serious Concern All over the World

The Earth’s population is set to hit the 8 billion mark in late 2022 . The rate of population growth reached new heights in the 20th century, and the world population doubled faster than ever before. It is estimated that the world population reached one billion in 1804. It was another 123 years before it reached two billion in 1927, but took only 33 years to reach three billion in 1960. Thereafter, the global population reached four billion in 1974 (14 years), five billion in 1987 (13 years), six billion in 1999 (12 years) and seven billion in 2011 (12 years).The consequences are currently being felt and, if the population growth is not checked, will continue to be felt for decades to come.

Every human deserves clean water, clear air, and space to live—a fair amount of Earth’s resources. These are basic human rights. There are no “right” or “wrong” people to inhabit our planet, but we must all work together to change our current population trajectory, which has us on track to hit nearly 11 billion people by 2100, a capacity our world simply cannot handle while providing adequately for all inhabitants.

Download Our Overpopulation White Paper

Each day, there are approximately 382,000 births, compared to 168,000 deaths. This accounts for a global net growth of over 200,000 people per day.

There is good news. According to the World Population Prospect the global population is growing at its slowest rate since 1950. The global growth has fallen by 50% — a good thing, to be sure. But, this lower growth rate of 1.1% is acting on an enormous total population of nearly 8 billion. Counter intuitively, this is resulting in even larger annual population growth than in 1967 — over 80 million additional people per year. This enormous total growth works out to eye-popping numbers: 1.5 million more people added to the planet every week. Over 220,00 people per day. That is 9,000 more people every hour, or 150 more people per minute. Almost 3 more people every second.

“Fertility, the report declares, has fallen markedly in recent decades for many countries: today, two-thirds of the global population lives in a country or area where lifetime fertility is below 2.1 births per woman, roughly the level required for zero growth in the long run, for a population with low mortality.”

The rights of women and girls are always front and center at Population Media Center . When women and girls are empowered, our earth is empowered. When women and girls have access to education, we all make more educated choices. When women and girls are given the rights they so adamantly deserve, we can correct some of the wrongs we have inflicted on this earth. See why the education and empowerment of women and girls is so important in this video.

Two Crises, One Solution

At PMC, we know that if human rights for women and girls could be fully realized, we would not only solve humanitarian crises related to the lives and opportunities of women and girls, we would also take huge steps toward solving our environmental challenges. We must realize that empowering women and girls is imperative if we are to achieve sustainability.

Why Overpopulation Is Damaging the Planet

A major impact of overpopulation is ecological damage . As the world’s population has grown exponentially, the Earth has suffered. The expanded population has adversely affected numerous ecosystems around the globe. Urban and suburban sprawl has encroached more and more on natural habitats, leading to the endangering and even extinction of numerous animal species.

What’s more, rainforests have decreased in size . Where they once covered 14 percent of the Earth’s surface, they now only cover 6 percent. Projections indicate that the remaining rainforests may cease to exist in less than half a century. The increase in agriculture has been a prime culprit in habitat destruction. More people require more food, and the expansion of farming has come at the cost of major deforestation.

Water supplies are depleting faster than they can be regenerated. While the vast majority of the Earth’s surface is covered by water, most of that is saltwater. Freshwater from lakes and streams makes up only about 2.5 percent of the world’s water. In some areas, such as the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), these water reserves are drying up. Desertification, the turning of arable land into barren desert, threatens the water supply throughout the word. This scarcity of water affects not only humans but also many animal species that are losing access to life-giving freshwater.

According to UNICEF “Even in countries with adequate water resources, water scarcity is not uncommon. Although this may be due to a number of factors — collapsed infrastructure and distribution systems, contamination, conflict, or poor management of water resources — it is clear that climate change, as well as human factors, are increasingly denying children their right to safe water and sanitation.”

Because of the relative wealth of many nations, especially those in the West and South East Asia, demand has steadily grown for leisure items. Vital natural resources are being used up to meet the need for non-essential goods. In turn, many of these products produce damaging emissions that affect the atmosphere or do not biodegrade and cause dangerous waste that destroys the environment.

Social Implications of Overpopulation

The scarcity caused by overpopulation has the potential to cause serious problems that may lead to violence. Already, protests have erupted in the Middle East over the lack of water available. Just this week, protestors in Iran showed up to show they need access to clean drinking water, now. Protests like these have the potential to turn violent and have serious consequences for governments struggling to deal with overwhelming poverty and depleted natural resources. Scarce resources cause prices to rise, which disproportionally affects less-developed nations.

Food is another resource that is affected by an overpopulated world. Due to increasing demands brought on by population growth, any serious disruption in the global food chain can have catastrophic repercussions. The war in Ukraine caused severe hardship for many nations, especially those in the Middle East, when food exports were halted. Some nations are almost wholly dependent upon other nations for their food needs; any major domestic issue, like conflict or famine, can put millions of people in danger of starvation.

The rising young population in many nations leads to massive youth unemployment, as there simply aren’t enough jobs to go around. Widespread youth unemployment leads to desperation, a driver of crime and violence, which leads to government crackdowns and loss of basic freedoms. Social unrest is a serious problem that is exacerbated by overpopulation.

When vital resources become scarce, people must compete for life’s necessities. Too often, this has led to stereotyping and blaming certain groups of people and widespread prejudice. The social fabric of societies fray when there are too many people fighting for fewer and fewer resources. Then, it becomes easier for beleaguered governments to pit citizen against citizen to keep them from uniting.

We must empower people, and ensure human rights, around the world or the entire world will suffer. As we approach 8 billion people, we must view this as an opportunity to work together to create the world we want. The world we need.

Later this year, we will have 8 billion opportunities to work together. 8 billion opportunities to empower people. 8 billion opportunities to change behavior toward togetherness, to improve communities, and change the way we have been interacting with our planet.

At Population Media Center, we have been talking about sustainable populations since our beginning.

More News About Overpopulation

Who will pay the price for baby bonuses.

Overpopulation Solutions That Put Women and Girls First

Overpopulation: cause and effect, how do overpopulation and overconsumption damage the environment what you need to know.

Although population growth in the 20th and 21st centuries has skyrocketed , it can be slowed, stopped and reversed through actions which enhance global justice and improve people’s lives. Under the United Nations’ most optimistic scenario, a sustainable reduction in global population could happen within decades.

We need to take many actions to reduce the impact of those of us already here – especially the richest of us who have the largest environmental impact – including through reducing consumption to sustainable levels, and systemic economic changes .

One of the most effective steps we can take to reduce our collective environmental impact is to choose smaller family size , and empower those who can’t make that choice freely to do so.

A little less makes a lot of difference

The United Nations makes a range of projections for future population growth, based on assumptions about how long people will live, what the fertility rate will be in different countries and how many people of childbearing age there will be. Its main population prediction is in the middle of that range – 9.7bn in 2050 and 10.4bn in 2100.

It also calculates that if, on average, every other family had one fewer child than it has assumed (i.e. ‘half a child less’ per family), there will be one billion fewer of us than it expects by 2050 – and about 3.5 billion fewer by the end of the century (within the lifetimes of many children born now). If that happens, our population will be smaller than it is today.

We can bring birth rates down

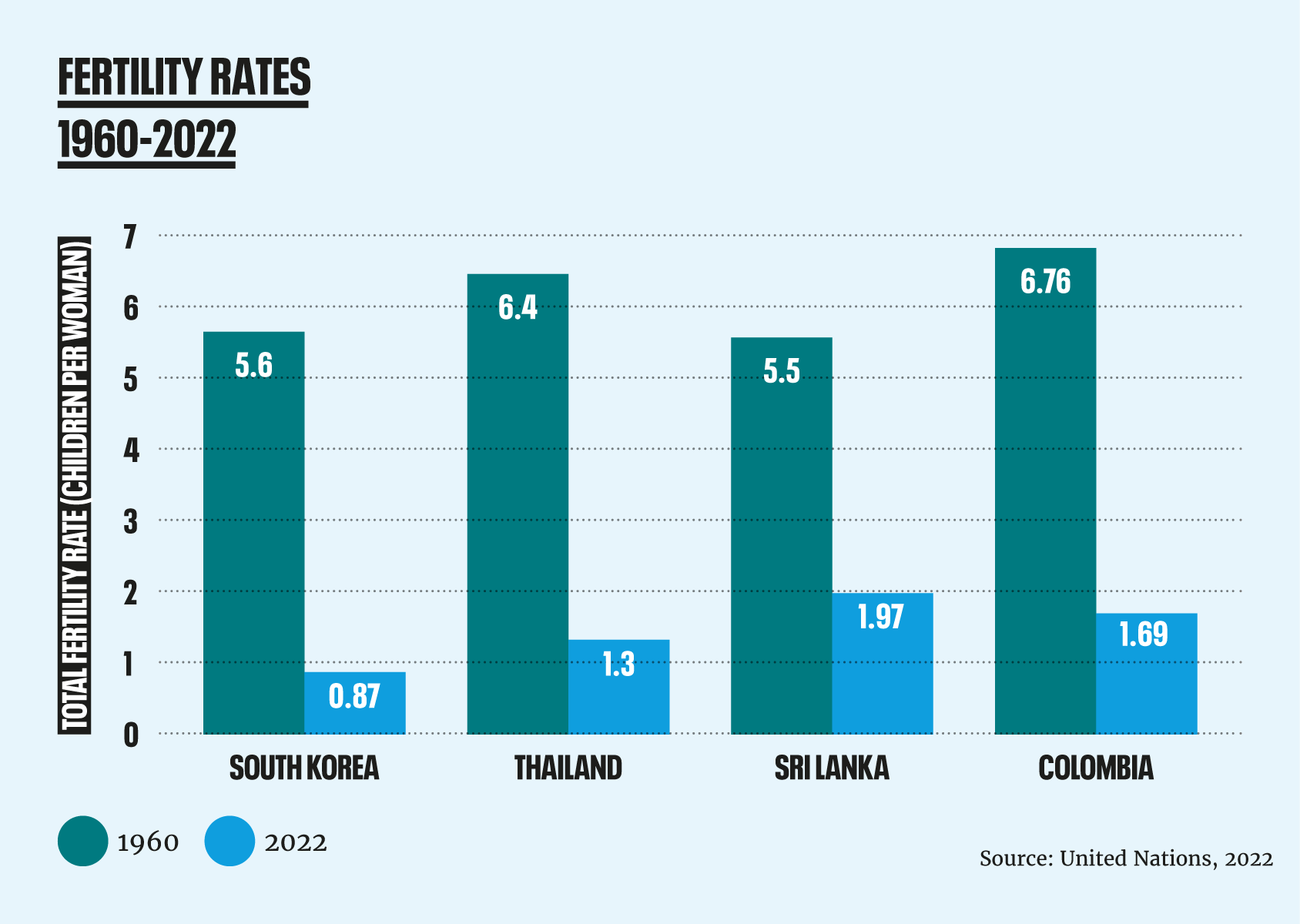

Many countries have had success in reducing their birth rates through policies which improved lives and empowered people. Our report Power to the People: how population policies work looks at some examples and the evidence that shows how different approaches work. Thailand, for instance, reduced its fertility rate (the average number of children per woman) by nearly 75% in just two generations with a targeted, creative and ethical population programme, which helped it to grow economically.

In the last ten years alone, fertility rates in Asia have dropped by nearly 10%.

1) Empowering women and girls

Where women and girls are empowered to choose what happens to their bodies and lives, fertility rates plummet. Empowerment means freedom to pursue education and a career, economic independence, easy access to sexual and reproductive healthcare, and ending horrific injustices like child marriage and gender-based violence. Overall, advancing the rights of women and girls is one of the most powerful solutions to our greatest environmental and social crises. Solutions 2 and 3 below are both tightly linked with female empowerment.

2) Removing barriers to contraception

Nearly half of all pregnancies are unintended. Currently, more than 200 million women who want to avoid pregnancy are not using modern contraception . There are a variety of reasons for this, including lack of access, concerns about side-effects and social pressure (often from male partners) not to use it.

These women mostly live in some of the world’s poorest countries, where population is set to rise by 3 billion by 2100. Overseas aid support for family planning is essential – both ensuring levels are high enough and that delivery of service is effective and goes hand-in-hand with advancing gender equality and engaging men.

Across the world, some people choose not to use contraception because they are influenced by assumptions, practices and pressures within their nations or communities. In some places, very large family sizes are considered desirable; in others, the use of contraception is discouraged or forbidden.

Work with women and men to change attitudes towards contraception and family size has formed a key part of successful family planning programmes. Religious barriers may also be overturned or sidelined. In Iran in the 1980s, a very successful family planning campaign was initiated when the country’s religious leader declared the use of contraception was consistent with Islamic belief. In Europe, some predominantly Catholic countries such as Portugal and Italy have some of the lowest fertility rates.

3) Quality education for all

Ensuring every child receives a quality education is one of the most effective levers for sustainable development. Many kids in developing countries are out of school, with girls affected more than boys due to gender inequality. Education opens doors and provides disadvantaged kids and young people with a “way out”. There is a direct correlation between the number of years a woman spends in education and how many children she ends up having. According to one study , African women with no education have, on average, 5.4 children; women who have completed secondary school have 2.7 and those who have a college education have 2.2. When family sizes are smaller, that also empowers women to gain education, take work and improve their economic opportunities.

A UN survey showed that the more educated respondents were, the more likely they were to believe that there is a climate emergency. This means that higher levels of education lead to the election of politicians with stronger environmental policy agendas.

4) Global justice and sustainable economies

The UN projects that population growth over the next century will be driven by the world’s very poorest countries. Escaping poverty is not just a fundamental human right but a vital way to bring birth rates down. The solutions above all help to decrease poverty. International aid, fair trade and global justice are all tools to help bring global population back to sustainable levels. A more equal distribution of resources and transitioning away from our damaging growth-dependent economic systems are key to a better future for people and planet.

5) improving child and maternal health

Where children do not survive into adulthood, people tend to have larger families. Reducing infant and child mortality has been key to bringing birth rates down across the world. Family planning and gender equality helps to achive that, through allowing women to start having children when they are older and increase spacing between children. As family size goes down, that also allows greater investment in health services, especially in low income countries.

6) Exercising the choice

In high income countries, most of us have the power to choose the size of our families – although we may also face pressures of all kinds over the size of the families we choose to have. When making choices about that, it’s important to remember that people in the rich parts of the world have a disproportionate impact on the global environment through our high level of consumption and greenhouse gas emissions – in the UK, for instance, each individual produces 70 times more carbon dioxide emissions than someone from Niger. When we understand the implications for our environment and our children’s futures of a growing population, we can recognise that choosing smaller families is one positive choice we can make.

Want to support our work towards a healthier, happier planet with a sustainable human population size that respects Earth’s limits?

Join us today!

People power not state power – population policies that work

We take a look at some of the population policies around the world which gave people choices and improved their lives.

Women’s Rights

The UN has projected that gender equality won’t be achieved until the next century. We must do more, faster.

Choosing a Small Family

Having a smaller family helps to take pressure off the planet, ensuring a better life for everyone’s children. Hear from people who have made that choice.

Do you want to find out more about our important work? Sign up to our newsletter to keep up to date with all things population and consumption.

- Chronicle Conversations

- Article archives

- Issue archives

- Join our mailing list

As the World's Population Surpasses 8 Billion, What Are the Implications for Planetary Health and Sustainability?

About the author, john wilmoth, clare menozzi, lina bassarsky and danan gu.

John Wilmoth is Director, Population Division of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA). Clare Menozzi, Lina Bassarsky and Danan Gu are Population Officers, UN DESA.

10 July 2023 I n November 2022, the world’s population surpassed 8 billion people , having grown by 1 billion since 2010. Reaching this milestone raises important questions concerning the impact of human activities on the planet and its ability to sustain life for humans and other species.

Environmental impacts depend on both human numbers and human activities

Humanity’s impact on the Earth’s environment is a product of the number of inhabitants, how much each person consumes and the technology used to meet that level of consumption. Reducing our total environmental impact can be achieved only by modifying one or more of these components.

The level of development and well-being that many high-income countries enjoy today has been achieved largely through highly resource-intensive patterns of consumption and production , which are not sustainable or replicable on a global scale. With today’s technologies, our planet could not sustainably support even its current population if average global consumption were on par with the levels of today’s high-income countries.

Environmental damage often arises from economic processes that lead to higher standards of living. This is true especially when the full social and environmental costs, such as damage from pollution, are not factored into economic decisions about production and consumption. Population growth amplifies such pressures by adding to total economic demand.

The rising demand for food illustrates the complex relationship between population growth and the environment. Population size has always been a major driver of total food demand. Fortunately, for several decades, global food production has grown more rapidly than population. Currently, enough food is being produced worldwide to feed everyone, yet hunger, malnutrition and food insecurity remain major concerns due primarily to failures of distribution and unequal access.

While population growth is a major driver of the increasing demand for food, changes in the amount and types of food consumed have also had a significant impact. As average incomes have increased, diets have shifted to include both more calories and more varied and resource-intensive foods. These changes have had negative environmental impacts in terms of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, loss of biodiversity, and water and soil pollution.

Ending hunger and addressing food insecurity will require a holistic approach that focuses on sustainably increasing agricultural productivity, reducing food loss and waste, and strengthening food system supply chains and infrastructure. Shifting towards healthier, more sustainable, plant-based diets can make an important contribution to reducing the environmental damage caused by the current global food system, which accounts for between one quarter and one third of total GHG emissions.

Consumption growth in richer countries versus population growth in the poorest countries

It has become increasingly clear that human activities are causing climate change. The burning of fossil fuels, which have provided most of the energy needed for economic development, releases GHGs, mainly in the form of carbon dioxide (CO₂). Indeed, there is a near-linear relationship between cumulative anthropogenic CO₂ emissions and the observed increase in average temperatures.

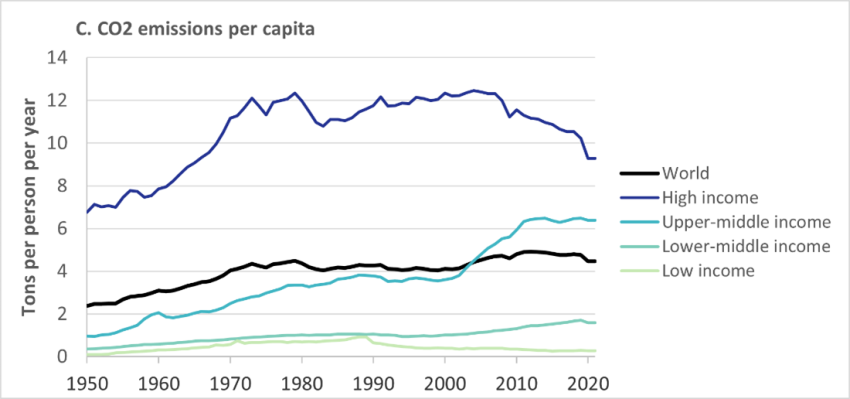

Population growth is one of the main drivers of increasing emissions. It is worth noting, however, that the countries emitting the largest per capita quantities of GHGs have been, to date, those where the average income is high and where the population is now growing slowly if at all, not those where the average income is low and the population is still growing rapidly.

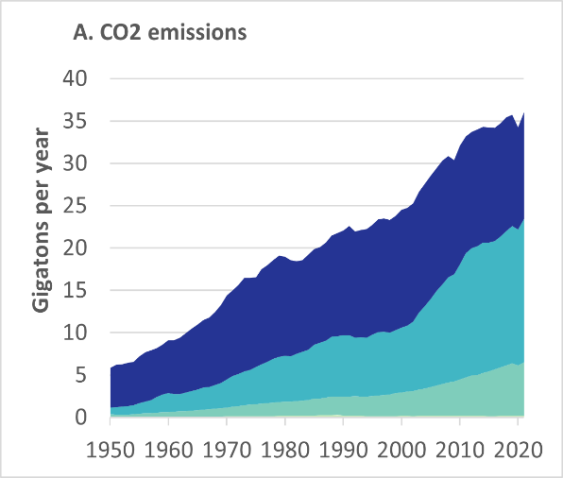

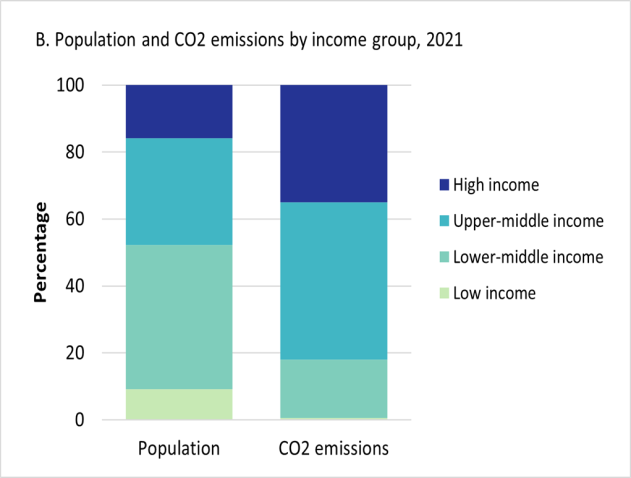

As of 2021, high-income and upper-middle-income countries, which together comprise 48 per cent of the world’s population, were responsible for about 82 per cent of the CO₂ added to the atmosphere each year (figure B, below). Low-income and lower-middle-income countries, where most future population growth is projected to take place, have so far contributed significantly less to these emissions, both in total (figure A, above) and per person (figure C, below).

In the coming decades, as the rate of global population growth continues to decline, population change is expected to become less and less important as a driver of rising GHG emissions. Meanwhile, trends in GDP per capita, energy efficiency and carbon intensity will become increasingly important.

Sustainability requires mitigating the environmental damage caused by human activities

One of the biggest challenges for the future is that the energy consumption of low-income and lower-middle-income countries will need to increase substantially if they are to develop economically and to achieve the Goals and targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. To end poverty and hunger, and to ensure that all people enjoy long and healthy lives and have access to a quality education and decent work, the economies of low-income and lower-middle-income countries will need to grow much more rapidly than their populations, requiring greatly expanded investments in infrastructure as well as increased access to affordable energy and modern technology in all sectors.

To achieve this accelerated growth, it will be essential for these countries to receive the necessary financial and technical assistance to ensure that their economies can grow while increasing their resilience and building their capacity to mitigate the causes, and adapt to the effects, of climate change. It is critical to ensure that their future economic growth is powered by clean sources of energy and does not replicate the over-reliance on fossil-fuel energy, which is the principal cause of the current climate crisis.

In the 2030 Agenda, Governments agreed on the importance of moving towards sustainable patterns of consumption and production, with the developed countries taking the lead and with all countries benefiting from the process. More affluent countries bear the greatest responsibility for moving rapidly to achieve net-zero emissions and for implementing strategies to decouple human economic activity from environmental degradation. Population trends are relatively predictable and difficult to change

In the coming decades, it is expected that the world’s population will continue to grow, albeit at a progressively slower pace. Projections by the United Nations suggest that the global population could rise to around 10.4 billion in the 2080s , after which it may stabilize or begin a gradual decline.

Over the next 30 years, trends in world population can be projected with confidence, since most people who will be alive have already been born. On a global scale, population growth in this period will be driven mostly by the momentum of past growth. Beyond three decades, however, the trend in global population size will depend increasingly on the future course of mortality and fertility. Therefore, although reductions in fertility over the next few years can have only a limited effect on global trends between now and 2050, such changes could have important consequences for the size of the global population in the second half of the century, since the impact of fertility cumulates from one generation to the next.

Even though changes in fertility are unlikely to have a major effect on population trends at the global scale over the next 30 years, the near-term impact of a fertility reduction can be more substantial for countries with relatively high levels of fertility today. For these countries, there is both greater uncertainty regarding future population trends and a greater potential for slowing growth through a reduction in fertility. In such cases, a sustained drop in the fertility level would not only slow the growth of the total population in the near term; it would also have important short-term impacts on the population age distribution, lowering the share of children in the population and allowing greater investments per child in health care, education and other critical services.

Demographic transition is an integral part of sustainable development

Achieving the Goals and targets of the 2030 Agenda, especially those related to reproductive health, education and gender equality, can help to accelerate the demographic transition towards longer lives and smaller families, in part by empowering people to make critical choices about family formation and childbearing. Today, however, millions around the globe, mostly in low-income and lower-middle-income countries, lack access to the information and services needed to determine whether and when to have children.

Ensuring that individuals, in particular women, are able to decide the number of children that they will have and the timing of their births can markedly improve well-being and help to disrupt intergenerational cycles of poverty. Beyond facilitating a fertility decline, better access to reproductive health care, including safe and effective methods of family planning, can accelerate countries’ economic and social development.

Greater efforts are needed to reduce the unmet need for family planning, to raise the minimum legal age at marriage, to integrate family planning and safe motherhood programmes into primary health care, and to improve female education and employment opportunities. Progress in these areas will facilitate a more rapid fertility decline in low-income countries. Given appropriate policies, a lower fertility level will enable these countries to reap a demographic dividend—in the form of faster per-capita economic growth—thanks to an increasing concentration of population in the working ages.

Ultimately, planetary health and the sustainability of our economic system will depend on the social, demographic, economic and environmental choices that we make. Each of these dimensions is important and can aggravate or mitigate the impact of the others. However, it is not necessary to choose between them. We can improve our prospects for achieving a sustainable future by reducing our reliance on fossil fuels; moving away from unsustainable patterns of consumption and production; ensuring access to quality education, health care and decent work; promoting gender equality; and ensuring that those who wish to have smaller families or to postpone childbearing are able to do so.

The UN Chronicle is not an official record. It is privileged to host senior United Nations officials as well as distinguished contributors from outside the United Nations system whose views are not necessarily those of the United Nations. Similarly, the boundaries and names shown, and the designations used, in maps or articles do not necessarily imply endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.

What if We Could Put an End to Loss of Precious Lives on the Roads?

Road safety is neither confined to public health nor is it restricted to urban planning. It is a core 2030 Agenda matter. Reaching the objective of preventing at least 50 per cent of road traffic deaths and injuries by 2030 would be a significant contribution to every SDG and SDG transition.

Promoting Evidence-Based Prevention Strategies to Mitigate the Harms of Drug Use: The Role of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

The engagement of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime with Member States is particularly focused on interventions addressing early adolescence through schools and families by piloting evidence-based, manualized programmes worldwide.

A Chronicle Conversation with Pradeep Kurukulasuriya (Part 2)

In April 2024, Pradeep Kurukulasuriya was appointed Executive Secretary of the United Nations Capital Development Fund (UNCDF). The UN Chronicle took the opportunity to ask Mr. Kurukulasuriya about the Fund and its unique role in implementing the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. This is Part 2 of our two-part interview.

Documents and publications

- Yearbook of the United Nations

- Basic Facts About the United Nations

- Journal of the United Nations

- Meetings Coverage and Press Releases

- United Nations Official Document System (ODS)

- Africa Renewal

Libraries and Archives

- Dag Hammarskjöld Library

- UN Audiovisual Library

- UN Archives and Records Management

- Audiovisual Library of International Law

- UN iLibrary

News and media

- UN News Centre

- UN Chronicle on Twitter

- UN Chronicle on Facebook

The UN at Work

- 17 Goals to Transform Our World

- Official observances

- United Nations Academic Impact (UNAI)

- Protecting Human Rights

- Maintaining International Peace and Security

- The Office of the Secretary-General’s Envoy on Youth

- United Nations Careers

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

How 21st century population issues and policies differ from those of the 20th century.

1. Introduction

2. population issues in the 20th and the 21st centuries, 3. discussions about whether to intervene on population trends, 4. discussions about how to intervene on population trends, 5. toward a new policy agenda, 6. conclusions, author contributions, institutional review board statement, informed consent statement, data availability statement, acknowledgments, conflicts of interest.

- United Nations. World Population Prospects: The 2022 Revision ; United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division: New York, NY, USA, 2022.

- O’Sullivan, J.N. World Population Is Growing Faster than We Thought. The Overpopulation Project. 2022. Available online: https://overpopulation-project.com/world-population-is-growing-faster-than-we-thought/ (accessed on 9 May 2023).

- Goldstone, J.A.; May, J.F. Contemporary Populations Issues—Chapter 1. In International Handbook of Population Policies ; May, J.F., Goldstone, J.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 3–19. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bernstein, S.; Hardee, K.; May, J.F.; Haslegrave, M. Population Institutions and International Population Conferences, Chapter 15. In International Handbook of Population Policies ; May, J.F., Goldstone, J.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 337–364. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ehrlich, P.R. The Population Bomb ; Ballantine Books: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [ Google Scholar ]

- Meadows, D.H.; Meadows, D.L.; Randers, J.; Behrens, W.W., III. The Limits to Growth ; Universe Books: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [ Google Scholar ]

- May, J.F. World Population Policies: Their Origin, Evolution, and Impact ; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012. [ Google Scholar ]

- May, J.F.; Guengant, J.P. Demography and Economic Emergence of Sub-Saharan Africa ; coll. Pocket Book Academy, No. 134-EN; Académie Royale de Belgique: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [ Google Scholar ]

- May, J.F.; Groth, H.; Turbat, V. Policies Needed to Capture a Demographic Dividend in Sub-Saharan Africa. Can. Stud. Popul. 2019 , 46 , 61–72. [ Google Scholar ]

- Vučković, M.; Adams, A.M. Population and Health Policies in Urban Areas, Chapter 18. In International Handbook of Population Policies ; May, J.F., Goldstone, J.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 397–429. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brown, S.K. International Migration Policies, Chapter 29. In International Handbook of Population Policies ; May, J.F., Goldstone, J.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 639–663. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pugliese, A.; Ray, J. Nearly 900 Million Worldwide Wanted to Migrate in 2021. Gallup, 24 January 2023. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/poll/468218/nearly-900-million-worldwide-wanted-migrate-2021.aspx (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- May, J.F.; Goldstone, J.A. Prospects for Population Policies and Interventions, Chapter 36. In International Handbook of Population Policies ; May, J.F., Goldstone, J.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 781–802. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sinding, S. Whatever Happened to the Population Explosion and Where Are We Today? Presentation at the Washington Institute of Foreign Affairs (WIFA), 25 April 2023 ; Washington Institute of Foreign Affairs: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [ Google Scholar ]

- Finkle, J.L.; Crane, B.B. Ideology and politics at Mexico City: The United States at the 1984 international conference on population. Popul. Dev. Rev. 1985 , 11 , 1–28. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- U.S. National Academy of Sciences. Population Growth and Economic Development: Policy Questions ; Report of the Working Group on Population Growth and Economic Development, National Research Council; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1986. [ Google Scholar ]

- Simon, J. The Ultimate Resource 2 ; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1996. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wattenberg, B.J. Fewer: How the New Demography of Depopulation Will Shape Our Future ; Ivan R. Dee: Chicago, IL, USA, 2004. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bongaarts, J.; O’Neill, B.C. Global warming policy: Is population left out in the cold? Science 2018 , 361 , 650–652. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Spoorenberg, T. Data Collection for Population Policies, Chapter 16. In International Handbook of Population Policies ; May, J.F., Goldstone, J.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 367–382. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cleland, J. The Contraceptive Revolution, Chapter 27. In International Handbook of Population Policies ; May, J.F., Goldstone, J.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 595–615. [ Google Scholar ]

- May, J.F. The Politics of Family Planning Policies and Programs in sub-Saharan Africa. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2017 , 43 , 308–329. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Gest, J.; Goldstone, J.A.; Hines, A.; Hoffman, E.; Ma, G. Choice and Consequence: Downstream Effects of US Immigration Admission Policies, 2020–2060 ; Fwd.us: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [ Google Scholar ]

- Turbat, V. Policies Needed to Capture Demographic Dividends, Chapter 19. In International Handbook of Population Policies ; May, J.F., Goldstone, J.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 431–447. [ Google Scholar ]

- May, J.F.; Rotenberg, S. A Call for Better Integrated Polices to Accelerate the Fertility Decline in Sub-Saharan Africa, Commentary. Stud. Fam. Plan. 2020 , 51 , 193–204. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

| Total Population | Annual Population | Total Fertility Rate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Mid-Year, Million) | Growth (%) | (Children Per Woman) | ||||

| 1950 | 2020 | 1950 | 2020 | 1950 | 2020 | |

| Africa | 228 | 1361 | 2.14 | 2.44 | 6.59 | 4.36 |

| North America | 162 | 374 | 1.65 | 0.37 | 2.97 | 1.63 |

| Latin America | ||||||

| and the Caribbean | 168 | 652 | 2.61 | 0.71 | 5.8 | 1.9 |

| Asia | 1379 | 4664 | 1.9 | 0.71 | 5.71 | 1.98 |

| Europe | 550 | 746 | 0.88 | −0.1 | 2.7 | 1.47 |

| Oceania | 13 | 44 | 2.73 | 1.28 | 3.67 | 2.16 |

| World | 2499 | 7841 | 1.73 | 0.92 | 4.86 | 2.35 |

| The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

Share and Cite

Goldstone, J.A.; May, J.F. How 21st Century Population Issues and Policies Differ from Those of the 20th Century. World 2023 , 4 , 467-476. https://doi.org/10.3390/world4030029

Goldstone JA, May JF. How 21st Century Population Issues and Policies Differ from Those of the 20th Century. World . 2023; 4(3):467-476. https://doi.org/10.3390/world4030029

Goldstone, Jack A., and John F. May. 2023. "How 21st Century Population Issues and Policies Differ from Those of the 20th Century" World 4, no. 3: 467-476. https://doi.org/10.3390/world4030029

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

The Growth of World Population: Analysis of the Problems and Recommendations for Research and Training (1963)

Chapter: world population problems, world population problems, the growth of world population.

The population of the world, now somewhat in excess of three billion persons, is growing at about two per cent a year, or faster than at any other period in man’s history. While there has been a steady increase of population growth during the past two or three centuries, it has been especially rapid during the past 20 years. To appreciate the pace of population growth we should recall that world population doubled in about 1,700 years from the time of Christ until the middle of the 17th century; it doubled again in about 200 years, doubled again in less than 100, and, if the current rate of population increase were to remain constant, would double every 35 years. Moreover, this rate is still increasing.

To be sure, the rate of increase cannot continue to grow much further. Even if the death rate were to fall to zero, at the present level of human reproduction the growth rate would not be much in excess of three and one-half per cent per year, and the time required for world population to double would not fall much below 20 years.

Although the current two per cent a year does not sound like an extraordinary rate of increase, a few simple calculations demonstrate that such a rate of increase in human population could not possibly continue for more than a few hundred years. Had this rate existed from the time of Christ to now, the world population would have increased in this period by a factor of about 7×10 16 ; in other words, there would be about 20 million individuals in place of each

person now alive, or 100 people to each square foot. If the present world population should continue to increase at its present rate of two per cent per year, then, within two centuries, there will be more than 150 billion people. Calculations of this sort demonstrate without question not only that the current continued increase in the rate of population growth must cease but also that this rate must decline again. There can be no doubt concerning this long-term prognosis: Either the birth rate of the world must come down or the death rate must go back up.

POPULATION GROWTH IN DIFFERENT PARTS OF THE WORLD

The rates of population growth are not the same, of course, in all parts of the world. Among the industrialized countries, Japan and most of the countries of Europe are now growing relatively slowly—doubling their populations in 50 to 100 years. Another group of industrialized countries—the United States, the Soviet Union, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and Argentina—are doubling their populations in 30 to 40 years, approximately the world average. The pre-industrial, low-income, and less-developed areas of the world, with two thirds of the world’s population—including Asia (except Japan and the Asiatic part of the Soviet Union), the southwestern Pacific islands (principally the Philippines and Indonesia), Africa (with the exception of European minorities), the Caribbean Islands, and Latin America (with the exception of Argentina and Uruguay)—are growing at rates ranging from moderate to very fast. Annual growth rates in all these areas range from one and one-half to three and one-half per cent, doubling in 20 to 40 years.

The rates of population growth of the various countries of the world are, with few exceptions, simply the differences between their birth rates and death rates. International migration is a negligible factor in rates of growth today. Thus, one can understand the varying rates of population growth of different parts of the world by understanding what underlies their respective birth and death rates.

THE REDUCTION OF FERTILITY AND MORTALITY IN WESTERN EUROPE SINCE 1800

A brief, over-simplified history of the course of birth and death rates in western Europe since about 1800 not only provides a frame of reference for understanding the current birth and death rates in Europe, but also casts some light on the present situation and prospects in other parts of the world. A simplified picture of the population history of a typical western European country is shown in

Figure 1 . Schematic presentation of birth and death rates in western Europe after 1800. (The time span varies roughly from 75 to 150 years.)

Figure 1 . The jagged interval in the early death rate and the recent birth rate is intended to indicate that all the rates are subject to substantial annual variation. The birth rate in 1800 was about 35 per 1,000 population and the average number of children ever born to women reaching age 45 was about five. The death rate in 1800 averaged 25 to 30 per 1,000 population although, as indicated, it was subject to variation because of episodic plagues, epidemics, and crop failures. The average expectation of life at birth was 35 years or less. The current birth rate in western European countries is 14 to 20 per 1,000 population with an average of two to three children born to a woman by the end of childbearing. The death rate is 7 to 11 per 1,000 population per year, and the expectation of life at birth is about 70 years. The death rate declined, starting in the late 18th or early 19th century, partly because of better transport and communication, wider markets, and greater productivity, but more directly because of the development of sanitation and, later, modern medicine. These developments, part of the changes in the whole complex of modern civilization, involved scientific and technological advances in many areas, specifically in public health, medicine, agriculture, and industry. The immediate cause of the decline in the birth rate was the increased deliberate control of fertility within marriage. The only important exception to this statement relates to Ireland, where the decline in the birth rate was brought about by an increase of several years in the age at marriage combined with an increase of 10 to 15 per cent in the proportion of people remaining single. The average age at marriage rose to 28 and more than a fourth of Irish women remained unmarried at age 45. In other countries, however, such social changes have had either insignificant or favorable effects on the birth rate. In these countries—England, Wales, Scotland, Scandinavia, the Low Countries, Germany, Switzerland, Austria, and France—the birth rate went down because of the practice of contraception among married couples. It is certain that there was no decline in the reproductive capacity; in fact, with improved health, the contrary is likely.

Only a minor fraction of the decline in western European fertility can be ascribed to the invention of modern techniques of contraception. In the first place, very substantial declines in some European countries antedated the invention and mass manufacture of contraceptive devices. Second, we know from surveys that as recently as just

before World War II more than half of the couples in Great Britain practicing birth control were practicing withdrawal, or coitus interruptus. There is similar direct evidence for other European countries.

In this instance, the decline in fertility was not the result of technical innovations in contraception, but of the decision of married couples to resort to folk methods known for centuries. Thus we must explain the decline in the western European birth rates in terms of why people were willing to modify their sexual behavior in order to have fewer children. Such changes in attitude were doubtless a part of a whole set of profound social and economic changes that accompanied the industrialization and modernization of western Europe. Among the factors underlying this particular change in attitude was a change in the economic consequences of childbearing. In a pre-industrial, agrarian society children start helping with chores at an early age; they do not remain in a dependent status during a long period of education. They provide the principal form of support for the parents in their old age, and, with high mortality, many children must be born to ensure that some will survive to take care of their parents. On the other hand, in an urban, industrialized society, children are less of an economic asset and more of an economic burden.

Among the social factors that might account for the change in attitude is the decline in the importance of the family as an economic unit that has accompanied the industrialization and modernization of Europe. In an industrialized economy, the family is no longer the unit of production and individuals come to be judged by what they do rather than who they are. Children leave home to seek jobs and parents no longer count on support by their children in their old age. As this kind of modernization continues, public education, which is essential to the production of a literate labor force, is extended to women, and thus the traditional subordinate role of women is modified. Since the burden of child care falls primarily on women, their rise in status is probably an important element in the development of an attitude favoring the deliberate limitation of family size. Finally, the social and economic changes characteristic of industrialization and modernization of a country are accompanied by and reinforce a rise of secularism, pragmatism, and rationalism in place of custom and tradition. Since modernization of a nation involves extension of deliberate human control over an increasing range of the environment,

it is not surprising that people living in an economy undergoing industrialization should extend the notion of deliberate and rational control to the question of whether or not birth should result from their sexual activities.

As the simplified representation in Figure 1 indicates, the birth rate in western Europe usually began its descent after the death rate had already fallen substantially. (France is a partial exception. The decline in French births began late in the 18th century and the downward courses of the birth and death rates during the 19th century were more or less parallel.) In general, the death rate appears to be affected more immediately and automatically by industrialization. One may surmise that the birth rate responds more slowly because its reduction requires changes in more deeply seated customs. There is in most societies a consensus in favor of improving health and reducing the incidence of premature death. There is no such consensus for changes in attitudes and behavior needed to reduce the birth rate.

DECLINING FERTILITY AND MORTALITY IN OTHER INDUSTRIALIZED AREAS

The pattern of declining mortality and fertility that we have described for western Europe fits not only the western European countries upon which it is based but also, with suitable adjustment in the initial birth and death rates and in the time scale, eastern and southern Europe (with the exception of Albania), the Soviet Union, Japan, the United States, Australia, Canada, Argentina, and New Zealand. In short, every country that has changed from a predominantly rural agrarian society to a predominantly industrial urban society and has extended public education to near-universality, at least at the primary school level, has had a major reduction in birth and death rates of the sort depicted in Figure 1 .

The jagged line describing the variable current birth rate represents in some instances—notably the United States—a major recovery in the birth rate from its low point. It must be remembered, however, that this recovery has not been caused by a reversion to uncontrolled family size. In the United States, for example, one can scarcely imagine that married couples have forgotten how to employ the contraceptive

techniques that reduced the birth rates to a level of mere replacement just before World War II. We know, in fact, that more couples are skilled in the use of contraception today than ever before. (Nevertheless, effective methods of controlling family size are still unknown and unused by many couples even in the United States.) The recent increase in the birth rate has been the result largely of earlier and more nearly universal marriage, the virtual disappearance of childless and one-child families, and a voluntary choice of two, three, or four children by a vast majority of American couples. There has been no general return to the very large family of pre-industrial times, although some segments of our society still produce many unwanted children.

POPULATION TRENDS IN LESS-DEVELOPED COUNTRIES

We turn now to a comparison of the present situation in the less-developed areas with the demographic circumstances in western Europe prior to the industrial revolution. Figure 2 presents the trends of birth and death rates in the less-developed areas in a rough schematic way similar to that employed in Figure 1 . There are several important differences between the circumstances in today’s less-developed areas and those in pre-industrial Europe. Note first that the birth rate in the less-developed areas is higher than it was in pre-industrial western Europe. This difference results from the fact that in many less-developed countries almost all women at age 35 have married, and at an average age substantially less than in 18th-century Europe. Second, many of the less-developed areas of the world today are much more densely populated than was western Europe at the beginning of the industrial revolution. Moreover, there are few remaining areas comparable to North and South America into which a growing population could move and which could provide rapidly expanding markets. Finally, and most significantly, the death rate in the less-developed areas is dropping very rapidly—a decline that looks almost vertical compared to the gradual decline in western Europe—and without regard to economic change.

The precipitous decline in the death rate that is occurring in the low-income countries of the world is a consequence of the development and application of low-cost public health techniques. Unlike

Figure 2 . Schematic presentation of birth and death rates in less-developed countries, mid-20th century. (The steep drop in the death rate from approximately 35 per thousand began at times varying roughly between 1940 and 1960 from country to country.)

the countries of western Europe, the less-developed areas have not had to wait for the slow gradual development of medical science, nor have they had to await the possibly more rapid but still difficult process of constructing major sanitary engineering works and the build-up of a large inventory of expensive hospitals, public health

services, and highly trained doctors. Instead, the less-developed areas have been able to import low-cost measures of controlling disease, measures developed for the most part in the highly industrialized countries. The use of residual insecticides to provide effective protection against malaria at a cost of no more than 25 cents per capita per annum is an outstanding example. Other innovations include antibiotics and chemotherapy, and low-cost ways of providing safe water supplies and adequate environmental sanitation in villages that in most other ways remain relatively untouched by modernization. The death rate in Ceylon was cut in half in less than a decade, and declines approaching this in rapidity are almost commonplace.

The result of a precipitous decline in mortality while the birth rate remains essentially unchanged is, of course, a very rapid acceleration in population growth, reaching rates of three to three and one-half per cent. Mexico’s population, for example, has grown in recent years at a rate of approximately three and one-half per cent a year. This extreme rate is undoubtedly due to temporary factors and would stabilize at not more than three per cent. But even at three per cent per year, two centuries would see the population of Mexico grow to about 13.5 billion people. Two centuries is a long time, however. Might we not expect that long before 200 years had passed the population of Mexico would have responded to modernization, as did the populations of western Europe, by reducing the birth rate? A positive answer might suggest that organized educational efforts to reduce the birth rate are not necessary. But there is a more immediate problem demanding solution in much less than two centuries: Is the current demographic situation in the less-developed countries impeding the process of modernization itself? If so, a course of action that would directly accelerate the decline in fertility becomes an important part of the whole development effort which is directed toward improving the quality of each individual’s life.

POPULATION TRENDS AND THE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OF PRE-INDUSTRIAL COUNTRIES

The combination of high birth rates and low or rapidly declining death rates now found in the less-developed countries implies two different characteristics of the population that have important impli-

cations for the pace of their economic development. One important characteristic is rapid growth, which is the immediate consequence of the large and often growing difference between birth and death rates; the other is the heavy burden of child dependency which results from a high birth rate whether death rates are high or low. A reduced death rate has only a slight effect on the proportion of children in the population, and this effect is in a rather surprising direction. The kinds of mortality reduction that have actually occurred in the world have the effect, if fertility remains unchanged, of reducing rather than increasing the average age of the population.

Mortality reduction produces this effect because the largest increases occur in the survival of infants, and, although the reduction in mortality increases the number of old persons, it increases the number of children even more. The result is that the high fertility found in low-income countries produces a proportion of children under fifteen of 40 to 45 per cent of the total population, compared to 25 per cent or less in most of the industrialized countries.

What do these characteristics of rapid growth and very large proportions of children imply about the capacity to achieve rapid industrialization? It must be noted that it is probably technically possible in every less-developed area to increase national output at rates even more rapid than the very rapid rates of population increase we have discussed, at least for a few years. The reason at least slight increases in per capita income appear feasible is that the low-income countries can import industrial and agricultural technology as well as medical technology. Briefly, the realistic question in the short run does not seem to be whether some increases in per capita income are possible while the population grows rapidly, but rather whether rapid population growth is a major deterrent to a rapid and continuing increase in per capita income.

A specific example will clarify this point. If the birth rate in India is not reduced, its population will probably double in the next 25 or 30 years, increasing from about 450 million to about 900 million. Agricultural experts consider it feasible within achievable limits of capital investment to accomplish a doubling of Indian agricultural output within the next 20 to 25 years. In the same period the output of the non-agricultural part of the Indian economy probably would be slightly more than doubled if the birth rate remained unchanged.

For a generation at least, then, India’s economic output probably can stay ahead of its maximum rate of population increase. This bare excess over the increase in population, however, is scarcely a satisfactory outcome of India’s struggle to achieve economic betterment. The real question is: Could India and the other less-developed areas of the world do substantially better if their birth rates and thus their population growth rates were reduced? Economic analysis clearly indicates that the answer is yes. Any growth of population adds to the rate of increase of national output that must be achieved in order to increase per capita output by any given amount.

To double per capita output in 30 years requires an annual increase in per capita output of 2.3 per cent; if population growth is three per cent a year, then the annual increase in national output must be raised to 5.3 per cent to achieve the desired level of economic growth. In either instance an economy, to grow, must divert effort and resources from producing for current consumption to the enhancement of future productivity. In other words, to grow faster an economy must raise its level of net investment. Net investment is investment in factories, roads, irrigation networks, and fertilizer plants, and also in education and training. The low-income countries find it difficult to mobilize resources for these purposes for three reasons: The pressure to use all available resources for current consumption is great; rapid population growth adds very substantially to the investment targets that must be met to achieve any given rate of increase in material well-being; and the very high proportions of children that result from high fertility demand that a larger portion of national output must be used to support a very large number of non-earning dependents. These dependents create pressure to produce for immediate consumption only. In individual terms, the family with a large number of children finds it more difficult to save, and a government that tries to finance development expenditures out of taxes can expect less support from a population with many children. Moreover, rapid population growth and a heavy burden of child dependency divert investment funds to less productive uses—that is, less productive in the long run. To achieve a given level of literacy in a population much more must be spent on schools. In an expanding population of large families, construction effort must go into housing rather than into factories or power plants.

Thus the combination of continued high fertility and greatly reduced mortality in the less-developed countries raises the levels of investment required while impairing the capacity of the economy to achieve high levels of investment. Economists have estimated that a gradual reduction in the rate of childbearing, totaling 50 per cent in 30 years, would add about 40 per cent to the income per consumer that could be achieved by the end of that time.

To recapitulate, a short-term increase in per capita income may be possible in most less-developed areas, even if the fertility rate is not reduced. Nevertheless, even in the short run, progress will be much faster and more certain if the birth rate falls. In the longer run, economic progress will eventually be stopped and reversed unless the birth rate declines or the death rate increases. Economic progress will be slower and more doubtful if less-developed areas wait for the supposedly inevitable impact of modernization on the birth rate. They run the risk that rapid population growth and adverse age distribution would themselves prevent the achievement of the very modernization they count on to bring the birth rate down.

READ FREE ONLINE

Welcome to OpenBook!

You're looking at OpenBook, NAP.edu's online reading room since 1999. Based on feedback from you, our users, we've made some improvements that make it easier than ever to read thousands of publications on our website.

Do you want to take a quick tour of the OpenBook's features?

Show this book's table of contents , where you can jump to any chapter by name.

...or use these buttons to go back to the previous chapter or skip to the next one.

Jump up to the previous page or down to the next one. Also, you can type in a page number and press Enter to go directly to that page in the book.

Switch between the Original Pages , where you can read the report as it appeared in print, and Text Pages for the web version, where you can highlight and search the text.

To search the entire text of this book, type in your search term here and press Enter .

Share a link to this book page on your preferred social network or via email.

View our suggested citation for this chapter.

Ready to take your reading offline? Click here to buy this book in print or download it as a free PDF, if available.

Get Email Updates

Do you enjoy reading reports from the Academies online for free ? Sign up for email notifications and we'll let you know about new publications in your areas of interest when they're released.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

World Population || Problem Solving || example || Che and Nel Camino. Follow along using the transcript. In this video im gonna show you how to solve basic Population Problem:)#...

Algebraic equations form the backbone of solving word problems in algebra. In this exercise, we translate the word problem about the world population into mathematical equations. This allows for a structured and methodical approach to finding the solution. The equations represent different relationships expressed in the problem. For example:

In other words, our model predicts the world’s population will eventually stabilize around 12.5 billion. A prediction for the long-term behavior of the population is a valuable conclusion to draw from our differential equation.

In fact, several countries across Europe and Asia are beginning to see population decline. Recently, the world’s second most populous country, China, reported its first year of population decline since the Great Chinese Famine in the 1960s [6].

A look at seven countries facing dramatic population changes - and how they are tackling the problem.

Overpopulation has a major negative impact on the world both ecologically and socially. Here is why everyone around the world should be concerned.

The UN projects that population growth over the next century will be driven by the world’s very poorest countries. Escaping poverty is not just a fundamental human right but a vital way to bring birth rates down. The solutions above all help to decrease poverty.

10 July 2023. I n November 2022, the world’s population surpassed 8 billion people, having grown by 1 billion since 2010. Reaching this milestone raises important questions concerning the...

Population Issues in the 20th and the 21st Centuries. After World War II, a round of population censuses carried out in the 1950s highlighted the extremely rapid population growth in several countries, particularly in Asia [ 3 ].

World Population Problems. THE GROWTH OF WORLD POPULATION. The population of the world, now somewhat in excess of three billion persons, is growing at about two per cent a year, or faster than at any other period in man’s history.