A business journal from the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania

The Impact of Social Media: Is it Irreplaceable?

July 26, 2019 • 15 min read.

Social media as we know it has barely reached its 20th birthday, but it’s changed the fabric of everyday life. What does the future hold for the sector and the players currently at the top?

- Public Policy

In little more than a decade, the impact of social media has gone from being an entertaining extra to a fully integrated part of nearly every aspect of daily life for many.

Recently in the realm of commerce, Facebook faced skepticism in its testimony to the Senate Banking Committee on Libra, its proposed cryptocurrency and alternative financial system . In politics, heartthrob Justin Bieber tweeted the President of the United States, imploring him to “let those kids out of cages.” In law enforcement, the Philadelphia police department moved to terminate more than a dozen police officers after their racist comments on social media were revealed.

And in the ultimate meshing of the digital and physical worlds, Elon Musk raised the specter of essentially removing the space between social and media through the invention — at some future time — of a brain implant that connects human tissue to computer chips.

All this, in the span of about a week.

As quickly as social media has insinuated itself into politics, the workplace, home life, and elsewhere, it continues to evolve at lightning speed, making it tricky to predict which way it will morph next. It’s hard to recall now, but SixDegrees.com, Friendster, and Makeoutclub.com were each once the next big thing, while one survivor has continued to grow in astonishing ways. In 2006, Facebook had 7.3 million registered users and reportedly turned down a $750 million buyout offer. In the first quarter of 2019, the company could claim 2.38 billion active users, with a market capitalization hovering around half a trillion dollars.

“In 2007 I argued that Facebook might not be around in 15 years. I’m clearly wrong, but it is interesting to see how things have changed,” says Jonah Berger, Wharton marketing professor and author of Contagious: Why Things Catch On . The challenge going forward is not just having the best features, but staying relevant, he says. “Social media isn’t a utility. It’s not like power or water where all people care about is whether it works. Young people care about what using one platform or another says about them. It’s not cool to use the same site as your parents and grandparents, so they’re always looking for the hot new thing.”

Just a dozen years ago, everyone was talking about a different set of social networking services, “and I don’t think anyone quite expected Facebook to become so huge and so dominant,” says Kevin Werbach, Wharton professor of legal studies and business ethics. “At that point, this was an interesting discussion about tech start-ups.

“Today, Facebook is one of the most valuable companies on earth and front and center in a whole range of public policy debates, so the scope of issues we’re thinking about with social media are broader than then,” Werbach adds.

Cambridge Analytica , the impact of social media on the last presidential election and other issues may have eroded public trust, Werbach said, but “social media has become really fundamental to the way that billions of people get information about the world and connect with each other, which raises the stakes enormously.”

Just Say No

“Facebook is dangerous,” said Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) at July’s hearing of the Senate Banking Committee. “Facebook has said, ‘just trust us.’ And every time Americans trust you, they seem to get burned.”

Social media has plenty of detractors, but by and large, do Americans agree with Brown’s sentiment? In 2018, 42% of those surveyed in a Pew Research Center survey said they had taken a break from checking the platform for a period of several weeks or more, while 26% said they had deleted the Facebook app from their cellphone.

A year later, though, despite the reputational beating social media had taken, the 2019 iteration of the same Pew survey found social media use unchanged from 2018.

Facebook has its critics, says Wharton marketing professor Pinar Yildirim, and they are mainly concerned about two things: mishandling consumer data and poorly managing access to it by third-party providers; and the level of disinformation spreading on Facebook.

“Social media isn’t a utility. It’s not like power or water where all people care about is whether it works. Young people care about what using one platform or another says about them.” –Jonah Berger

“The question is, are we at a point where the social media organizations and their activities should be regulated for the benefit of the consumer? I do not think more regulation will necessarily help, but certainly this is what is on the table,” says Yildirim. “In the period leading to the [2020 U.S. presidential] elections, we will hear a range of discussions about regulation on the tech industry.”

Some proposals relate to stricter regulation on collection and use of consumer data, Yildirim adds, noting that the European Union already moved to stricter regulations last year by adopting the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) . “A number of companies in the U.S. and around the world adopted the GDPR protocol for all of their customers, not just for the residents of EU,” she says. “We will likely hear more discussions on regulation of such data, and we will likely see stricter regulation of this data.”

The other discussion bound to intensify is around the separation of Big Tech into smaller, easier to regulate units. “Most of us academics do not think that dividing organizations into smaller units is sufficient to improve their compliance with regulation. It also does not necessarily mean they will be less competitive,” says Yildirim. “For instance, in the discussion of Facebook, it is not even clear yet how breaking up the company would work, given that it does not have very clear boundaries between different business units.”

Even if such regulations never come to pass, the discussions “may nevertheless hurt Big Tech financially, given that most companies are publicly traded and it adds to the uncertainty,” Yildirim notes.

One prominent commentator about the negative impact of social media is Jaron Lanier, whose fervent opposition makes itself apparent in the plainspoken title of his 2018 book Ten Arguments for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now . He cites loss of free will, social media’s erosion of the truth and destruction of empathy, its tendency to make people unhappy, and the way in which it is “making politics impossible.” The title of the last chapter: “Social Media Hates Your Soul.”

Lanier is no tech troglodyte. A polymath who bridges the digital and analog realms, he is a musician and writer, has worked as a scientist for Microsoft, and was co-founder of pioneering virtual reality company VPL Research. The nastiness that online existence brings out in users “turned out to be like crude oil for the social media companies and other behavior manipulation empires that quickly came to dominate the internet, because it fuelled negative behavioral feedback,” he writes.

“Social media has become really fundamental to the way that billions of people get information about the world and connect with each other, which raises the stakes enormously.” –Kevin Werbach

Worse, there is an addictive quality to social media, and that is a big issue, says Berger. “Social media is like a drug, but what makes it particularly addictive is that it is adaptive. It adjusts based on your preferences and behaviors,” he says, “which makes it both more useful and engaging and interesting, and more addictive.”

The effect of that drug on mental health is only beginning to be examined, but a recent University of Pennsylvania study makes the case that limiting use of social media can be a good thing. Researchers looked at a group of 143 Penn undergraduates, using baseline monitoring and randomly assigning each to either a group limiting Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat use to 10 minutes per platform per day, or to one told to use social media as usual for three weeks. The results, published in the Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology , showed significant reductions in loneliness and depression over three weeks in the group limiting use compared to the control group.

However, “both groups showed significant decreases in anxiety and fear of missing out over baseline, suggesting a benefit of increased self-monitoring,” wrote the authors of “ No More FOMO: Limiting Social Media Decreases Loneliness and Depression .”

Monetizing a League (and a Reality) All Their Own

No one, though, is predicting that social media is a fad that will pass like its analog antecedent of the 1970s, citizens band radio. It will, however, evolve. The idea of social media as just a way to reconnect with high school friends seems quaint now. The impact of social media today is a big tent, including not only networks like Facebook, but also forums like Reddit and video-sharing platforms.

“The question is, are we at a point where the social media organizations and their activities should be regulated for the benefit of the consumer?” –Pinar Yildirim

Virtual worlds and gaming have become a major part of the sector, too. Wharton marketing professor Peter Fader says gamers are creating their own user-generated content through virtual worlds — and the revenue to go with it. He points to one group of gamers that use Grand Theft Auto as a kind of stage or departure point “to have their own virtual show.” In NoPixel, the Grand Theft Auto roleplaying server, “not much really happens and millions are tuning in to watch them. Just watching, not even participating, and it’s either live-streamed or recorded. And people are making donations to support this thing. The gamers are making hundreds of thousands of dollars.

“Now imagine having a 30-person reality show all filmed live and you can take the perspective of one person and then watch it again from another person’s perspective,” he continues. “Along the way, they can have a tip jar or talk about things they endorse. That kind of immersive media starts to build the bridge to what we like to get out of TV, but even better. Those things are on the periphery right now, but I think they are going to take over.”

Big players have noticed the potential of virtual sports and are getting into the act. In a striking example of the physical world imitating the digital one, media companies are putting up real-life stadiums where teams compete in video games. Comcast Spectator in March announced that it is building a new $50 million stadium in South Philadelphia that will be the home of the Philadelphia Fusion, the city’s e-sports team in the Overwatch League.

E-sports is serious business, with revenues globally — including advertising, sponsorships, and media rights — expected to reach $1.1 billion in 2019, according to gaming industry analytics company Newzoo.

“E-sports is absolutely here to stay,” says Fader, “and I think it’s a safe bet to say that e-sports will dominate most traditional sports, managing far more revenue and having more impact on our consciousness than baseball.”

It’s no surprise, then, that Facebook has begun making deals to carry e-sports content. In fact, it is diversification like this that may keep Facebook from ending up like its failed upstart peers. One thing that Facebook has managed to do that MySpace, Friendster, and others didn’t, is “a very good job of creating functional integration with the value they are delivering, as opposed to being a place to just share photos or send messages, it serves a lot of diversified functions,” says Keith E. Niedermeier, director of Wharton’s undergraduate marketing program and an adjunct professor of marketing. “They are creating groups and group connections, but you see them moving into lots of other services like streaming entertainment, mobile payments, and customer-to-customer buying and selling.”

“[WeChat] has really instantiated itself as a day-to-day tool in China, and it’s clear to me that Facebook would like to emulate that sort of thing.” –Keith Niedermeier

In China, WeChat has become the biggest mobile payment platform in the world and it is the platform for many third-party apps for things like bike sharing and ordering airplane tickets. “It has really instantiated itself as a day-to-day tool in China, and it’s clear to me that Facebook would like to emulate that sort of thing,” says Niedermeier.

Among nascent social media platforms that are particularly promising right now, Yildirim says that “social media platforms which are directed at achieving some objectives with smaller scale and more homogenous people stand a higher chance of entering the market and being able to compete with large, general-purpose platforms such as Facebook and Twitter.”

Irreplaceable – and Damaging?

Of course, many have begun to believe that the biggest challenge around the impact of social media may be the way it is changing society. The “attention-grabbing algorithms underlying social media … propel authoritarian practices that aim to sow confusion, ignorance, prejudice, and chaos, thereby facilitating manipulation and undermining accountability,” writes University of Toronto political science professor Ronald Deibert in a January essay in the Journal of Democracy .

Berger notes that any piece of information can now get attention, whether it is true or false. This means more potential for movements both welcome as well as malevolent. “Before, only media companies had reach, so it was harder for false information to spread. It could happen, but it was slow. Now anyone can share anything, and because people tend to believe what they see, false information can spread just as, if not more easily, than the truth.

“It’s certainly allowed more things to bubble up rather than flow from the top down,” says Berger. Absent gatekeepers, “everyone is their own media company, broadcasting to the particular set of people that follow them. It used to be that a major label signing you was the path to stardom. Now artists can build their own following online and break through that way. Social media has certainly made fame and attention more democratic, though not always in a good way.”

Deibert writes that “in a short period of time, digital technologies have become pervasive and deeply embedded in all that we do. Unwinding them completely is neither possible nor desirable.”

His cri de coeur argues: that citizens have the right to know what companies and governments are doing with their personal data, and that this right be extended internationally to hold autocratic regimes to account; that companies be barred from selling products and services that enable infringements on human rights and harms to civil society; for the creation of independent agencies with real power to hold social-media platforms to account; and the creation and enforcement of strong antitrust laws to end dominance of a very few social-media companies.

“Social media has certainly made fame and attention more democratic, though not always in a good way.” –Jonah Berger

The rising tide of concern is now extending across sectors. The U.S. Justice Department has recently begun an anti-trust investigation into how tech companies operate in social media, search, and retail services. In July, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation announced the award of nearly $50 million in new funding to 11 U.S. universities to research how technology is transforming democracy. The foundation is also soliciting additional grant proposals to fund policy and legal research into the “rules, norms, and governance” that should be applied to social media and technology companies.

Given all of the reasons not to engage with social media — the privacy issues, the slippery-slope addiction aspect of it, its role in spreading incivility — do we want to try to put the genie back in the bottle? Can we? Does social media definitely have a future?

“Yes, surely it does,” says Yildirim. “Social connections are fabrics of society. Just as the telegraph or telephone as an innovation of communication did not reduce social connectivity, online social networks did not either. If anything, it likely increased connectivity, or reduced the cost of communicating with others.”

It is thanks to online social networks that individuals likely have larger social networks, she says, and while many criticize the fact that we are in touch with large numbers of individuals in a superficial way, these light connections may nevertheless be contributing to our lives when it comes to economic and social outcomes — ranging from finding jobs to meeting new people.

“We are used to being in contact with more individuals, and it is easier to remain in contact with people we only met once. Giving up on this does not seem likely for humans,” she says. “The technology with which we keep in touch may change, may evolve, but we will have social connections and platforms which enable them. Facebook may be gone in 10 years, but there will be something else.”

More From Knowledge at Wharton

How High-skilled Immigration Creates Jobs and Drives Innovation

Why Do So Many EV Startups Fail?

The U.S. Housing Market Has Homeowners Stuck | Lu Liu

Looking for more insights.

Sign up to stay informed about our latest article releases.

Social Media's Impact on Society

This article was updated on: 11/19/2021

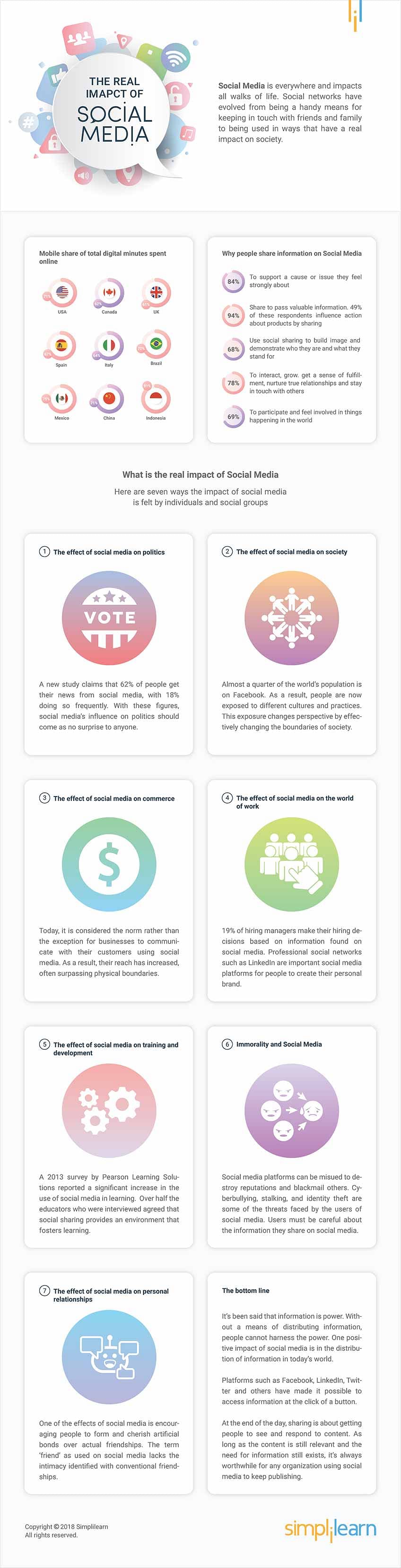

Social media is an undeniable force in modern society. With over half the global population using social platforms, and the average person spending at least two hours scrolling through them every day , it can’t be overstated that our digital spaces have altered our lives as we knew them. From giving us new ways to come together and stay connected with the world around us, to providing outlets for self-expression, social media has fundamentally changed the way we initiate, build and maintain our relationships.

But while these digital communities have become commonplace in our daily lives, researchers are only beginning to understand the consequences of social media use on future generations. Social media models are changing every day, with major platforms like Meta and Instagram evolving into primary digital advertising spaces as much as social ones. A critical responsibility falls on marketers to spread messages that inform, rather than contribute to the sea of misinformation that thrives on social media.

Read on to see what’s on marketers’ minds when it comes to the impact of social media on society:

MENTAL HEALTH

You’ve likely heard about the negative impacts that social media can have on mental health. Experts are weighing in on the role that the algorithms and design of social platforms play in exasperating these concerns.

At SXSW 2019 , Aza Raskin, co-founder of the Center for Human Technology, talked about the “digital loneliness epidemic,” which focused on the rise of depression and loneliness as it relates to social media use. During the panel, Raskin spoke about the “infinite scroll,” the design principle that enables users to continuously scroll through their feeds, without ever having to decide whether to keep going—it’s hard to imagine what the bottom of a TikTok feed would look like, and that’s intentional. But with the knowledge that mental health concerns are undeniably linked to social media use, the dilemma we’re now facing is when does good design become inhumane design?

Arguably, Rankin’s term for social media use could now be renamed the “digital loneliness pandemic ” as the world faces unprecedented isolation during the COVID-19 outbreak. In 2020 the Ad Council released a study exploring factors that cause loneliness, and what can be done to alleviate it. Interestingly, our research found that while social isolation is one factor that can cause loneliness, 73% of respondents typically maintain interpersonal relationships via technology, including engaging with others on social media. Simply put, social media use can both contribute to and help mitigate feelings of isolation. So how do we address this Catch-22? We should ask ourselves how we can use social media as a platform to foster positive digital communities as young adults rely on it more and more to cope with isolation.

Findings like these have been useful as we reexamine the focuses of Ad Council campaigns. In May 2020, our iconic Seize the Awkward campaign launched new creative highlighting ways young people could use digital communications tools to stay connected and check in on one another’s mental health while practicing physical distancing. A year later, we launched another mental health initiative, Sound It Out , which harnesses the power of music to speak to 10-14-year-olds’ emotional wellbeing. Ad Council has seen the importance of spreading awareness around mental health concerns as they relate to social media consumption in young adults—who will become the next generation of marketers.

EXTREMISM & HATE

Another trend on experts’ minds is how the algorithms behind these massively influential social media platforms may contribute to the rise of extremism and online radicalization.

Major social networking sites have faced criticism over how their advanced algorithms can lead users to increasingly fringe content. These platforms are central to discussions around online extremism, as social forums have become spaces for extreme communities to form and build influence digitally. However, these platforms are responding to concerns and troubleshooting functionalities that have the potential to result in dangerous outcomes. Meta, for example, announced test prompts to provide anti-extremism resources and support for users it believes have been exposed to extremist content on their feeds.

But as extremist groups continue to turn to fringe chatrooms and the “dark web” that begin on social media, combing through the underbelly of the internet and stopping the spread of hateful narratives is a daunting task. Promoting public service messages around Racial Justice and Diversity & Inclusion are just some of the ways that Ad Council and other marketers are using these platforms to move the needle away from hateful messaging and use these platforms to change mindsets in a positive way.

PUBLIC HEALTH CRISES

Social media can be both a space to enlighten and spread messages of doubt. The information age we’re all living in has enabled marketers to intervene as educators and providers of informative messaging to all facets of the American public. And no time has this been more urgent than during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Public health efforts around mask mandates and vaccine rollouts have now become increasingly polarized issues. Social media platforms have turned into breeding grounds for spreading disinformation around vaccinations, and as a result, has contributed to vaccine hesitancy among the American public. Meta, Instagram, and other platforms have begun to flag certain messages as false, but the work of regulating misinformation, especially during a pandemic, will be an enduring problem. To combat this, Ad Council and the COVID Collaborative have put a particular emphasis on our historic COVID-19 Vaccine Education initiative, which has connected trusted messengers with the “uncommitted” American public who feel the most uncertainty around getting the vaccine.

Living during a global pandemic has only solidified a societal need for social media as a way to stay connected to the world at large. During the pandemic, these platforms have been used to promote hopeful and educational messages, like #AloneTogether , and ensures that social media marketing can act as a public service.

DIGITAL ACTIVISM

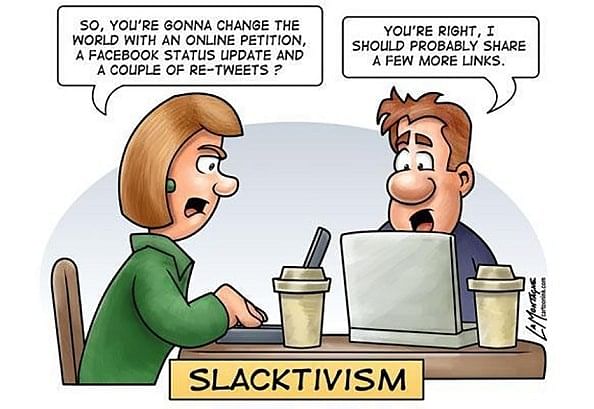

Beyond serving as an educational resource, social media has been the space for digital activism across a myriad of social justice issues. Movements like #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter have gone viral thanks to the power of social media. What starts as a simple hashtag has resulted in real change, from passing sexual harassment legislation in response to #MeToo, to pushing for criminal justice reform because of BLM activists. In these cases, social media empowered likeminded people to organize around a specific cause in a way not possible before.

It’s impossible to separate the role of social media from the scalable impact that these movements have had on society. #MeToo and BLM are just two examples of movements that have sparked national attention due in large part to conversations that began on social media.

SO, WHAT DOES THIS MEAN FOR MARKETERS?

Social media is a great equalizer that allows for large-scale discourse and an endless, unfiltered stream of content. Looking beyond the repercussions for a generation born on social media, these platforms remain an essential way for marketers to reach their audiences.

Whether you argue there are more benefits or disadvantages to a world run on social media, we can all agree that social media has fundamentally shifted how society communicates. With every scroll, view, like, comment and share, we’re taught something new about the impact of social media on the way we think and see the world.

But until we find a way to hold platforms more accountable for the global consequences of social media use, it’s up to marketers to use these digital resources as engines of progressive messaging. We can’t control the adverse effects of the Internet, but as marketers, we can do our part in ensuring that the right messages are being spread and that social media remains a force for social good.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTERS

Want to stay up to date on industry news, insights, and all our latest work? Subscribe to our email newsletters!

Suggestions or feedback?

MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Machine learning

- Social justice

- Black holes

- Classes and programs

Departments

- Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Brain and Cognitive Sciences

- Architecture

- Political Science

- Mechanical Engineering

Centers, Labs, & Programs

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL)

- Picower Institute for Learning and Memory

- Lincoln Laboratory

- School of Architecture + Planning

- School of Engineering

- School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

- Sloan School of Management

- School of Science

- MIT Schwarzman College of Computing

Why social media has changed the world — and how to fix it

Press contact :, media download.

*Terms of Use:

Images for download on the MIT News office website are made available to non-commercial entities, press and the general public under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives license . You may not alter the images provided, other than to crop them to size. A credit line must be used when reproducing images; if one is not provided below, credit the images to "MIT."

Previous image Next image

Are you on social media a lot? When is the last time you checked Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram? Last night? Before breakfast? Five minutes ago?

If so, you are not alone — which is the point, of course. Humans are highly social creatures. Our brains have become wired to process social information, and we usually feel better when we are connected. Social media taps into this tendency.

“Human brains have essentially evolved because of sociality more than any other thing,” says Sinan Aral, an MIT professor and expert in information technology and marketing. “When you develop a population-scale technology that delivers social signals to the tune of trillions per day in real-time, the rise of social media isn’t unexpected. It’s like tossing a lit match into a pool of gasoline.”

The numbers make this clear. In 2005, about 7 percent of American adults used social media. But by 2017, 80 percent of American adults used Facebook alone. About 3.5 billion people on the planet, out of 7.7 billion, are active social media participants. Globally, during a typical day, people post 500 million tweets, share over 10 billion pieces of Facebook content, and watch over a billion hours of YouTube video.

As social media platforms have grown, though, the once-prevalent, gauzy utopian vision of online community has disappeared. Along with the benefits of easy connectivity and increased information, social media has also become a vehicle for disinformation and political attacks from beyond sovereign borders.

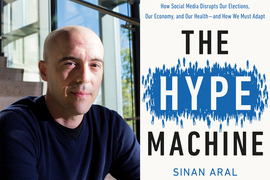

“Social media disrupts our elections, our economy, and our health,” says Aral, who is the David Austin Professor of Management at the MIT Sloan School of Management.

Now Aral has written a book about it. In “The Hype Machine,” published this month by Currency, a Random House imprint, Aral details why social media platforms have become so successful yet so problematic, and suggests ways to improve them.

As Aral notes, the book covers some of the same territory as “The Social Dilemma,” a documentary that is one of the most popular films on Netflix at the moment. But Aral’s book, as he puts it, "starts where ‘The Social Dilemma’ leaves off and goes one step further to ask: What can we do about it?”

“This machine exists in every facet of our lives,” Aral says. “And the question in the book is, what do we do? How do we achieve the promise of this machine and avoid the peril? We’re at a crossroads. What we do next is essential, so I want to equip people, policymakers, and platforms to help us achieve the good outcomes and avoid the bad outcomes.”

When “engagement” equals anger

“The Hype Machine” draws on Aral’s own research about social networks, as well as other findings, from the cognitive sciences, computer science, business, politics, and more. Researchers at the University of California at Los Angeles, for instance, have found that people obtain bigger hits of dopamine — the chemical in our brains highly bound up with motivation and reward — when their social media posts receive more likes.

At the same time, consider a 2018 MIT study by Soroush Vosoughi, an MIT PhD student and now an assistant professor of computer science at Dartmouth College; Deb Roy, MIT professor of media arts and sciences and executive director of the MIT Media Lab; and Aral, who has been studying social networking for 20 years. The three researchers found that on Twitter, from 2006 to 2017, false news stories were 70 percent more likely to be retweeted than true ones. Why? Most likely because false news has greater novelty value compared to the truth, and provokes stronger reactions — especially disgust and surprise.

In this light, the essential tension surrounding social media companies is that their platforms gain audiences and revenue when posts provoke strong emotional responses, often based on dubious content.

“This is a well-designed, well-thought-out machine that has objectives it maximizes,” Aral says. “The business models that run the social-media industrial complex have a lot to do with the outcomes we’re seeing — it’s an attention economy, and businesses want you engaged. How do they get engagement? Well, they give you little dopamine hits, and … get you riled up. That’s why I call it the hype machine. We know strong emotions get us engaged, so [that favors] anger and salacious content.”

From Russia to marketing

“The Hype Machine” explores both the political implications and business dimensions of social media in depth. Certainly social media is fertile terrain for misinformation campaigns. During the 2016 U.S. presidential election, Russia spread false information to at least 126 million people on Facebook and another 20 million people on Instagram (which Facebook owns), and was responsible for 10 million tweets. About 44 percent of adult Americans visited a false news source in the final weeks of the campaign.

“I think we need to be a lot more vigilant than we are,” says Aral.

We do not know if Russia’s efforts altered the outcome of the 2016 election, Aral says, though they may have been fairly effective. Curiously, it is not clear if the same is true of most U.S. corporate engagement efforts.

As Aral examines, digital advertising on most big U.S. online platforms is often wildly ineffective, with academic studies showing that the “lift” generated by ad campaigns — the extent to which they affect consumer action — has been overstated by a factor of hundreds, in some cases. Simply counting clicks on ads is not enough. Instead, online engagement tends to be more effective among new consumers, and when it is targeted well; in that sense, there is a parallel between good marketing and guerilla social media campaigns.

“The two questions I get asked the most these days,” Aral says, “are, one, did Russia succeed in intervening in our democracy? And two, how do I measure the ROI [return on investment] from marketing investments? As I was writing this book, I realized the answer to those two questions is the same.”

Ideas for improvement

“The Hype Machine” has received praise from many commentators. Foster Provost, a professor at New York University’s Stern School of Business, says it is a “masterful integration of science, business, law, and policy.” Duncan Watts, a university professor at the University of Pennsylvania, says the book is “essential reading for anyone who wants to understand how we got here and how we can get somewhere better.”

In that vein, “The Hype Machine” has several detailed suggestions for improving social media. Aral favors automated and user-generated labeling of false news, and limiting revenue-collection that is based on false content. He also calls for firms to help scholars better research the issue of election interference.

Aral believes federal privacy measures could be useful, if we learn from the benefits and missteps of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in Europe and a new California law that lets consumers stop some data-sharing and allows people to find out what information companies have stored about them. He does not endorse breaking up Facebook, and suggests instead that the social media economy needs structural reform. He calls for data portability and interoperability, so “consumers would own their identities and could freely switch from one network to another.” Aral believes that without such fundamental changes, new platforms will simply replace the old ones, propelled by the network effects that drive the social-media economy.

“I do not advocate any one silver bullet,” says Aral, who emphasizes that changes in four areas together — money, code, norms, and laws — can alter the trajectory of the social media industry.

But if things continue without change, Aral adds, Facebook and the other social media giants risk substantial civic backlash and user burnout.

“If you get me angry and riled up, I might click more in the short term, but I might also grow really tired and annoyed by how this is making my life miserable, and I might turn you off entirely,” Aral observes. “I mean, that’s why we have a Delete Facebook movement, that’s why we have a Stop Hate for Profit movement. People are pushing back against the short-term vision, and I think we need to embrace this longer-term vision of a healthier communications ecosystem.”

Changing the social media giants can seem like a tall order. Still, Aral says, these firms are not necessarily destined for domination.

“I don’t think this technology or any other technology has some deterministic endpoint,” Aral says. “I want to bring us back to a more practical reality, which is that technology is what we make it, and we are abdicating our responsibility to steer technology toward good and away from bad. That is the path I try to illuminate in this book.”

Share this news article on:

Press mentions.

Prof. Sinan Aral’s new book, “The Hype Machine,” has been selected as one of the best books of the year about AI by Wired . Gilad Edelman notes that Aral’s book is “an engagingly written shortcut to expertise on what the likes of Facebook and Twitter are doing to our brains and our society.”

Prof. Sinan Aral speaks with Danny Crichton of TechCrunch about his new book, “The Hype Machine,” which explores the future of social media. Aral notes that he believes a starting point “for solving the social media crisis is creating competition in the social media economy.”

New York Times

Prof. Sinan Aral speaks with New York Times editorial board member Greg Bensinger about how social media platforms can reduce the spread of misinformation. “Human-in-the-loop moderation is the right solution,” says Aral. “It’s not a simple silver bullet, but it would give accountability where these companies have in the past blamed software.”

Prof. Sinan Aral speaks with Kara Miller of GBH’s Innovation Hub about his research examining the impact of social media on everything from business re-openings during the Covid-19 pandemic to politics.

Prof. Sinan Aral speaks with NPR’s Michael Martin about his new book, “The Hype Machine,” which explores the benefits and downfalls posed by social media. “I've been researching social media for 20 years. I've seen its evolution and also the techno utopianism and dystopianism,” says Aral. “I thought it was appropriate to have a book that asks, 'what can we do to really fix the social media morass we find ourselves in?'”

Previous item Next item

Related Links

- MIT Sloan School of Management

Related Topics

- Business and management

- Social media

- Books and authors

- Behavioral economics

Related Articles

The catch to putting warning labels on fake news

Our itch to share helps spread Covid-19 misinformation

Better fact-checking for fake news

Study: On Twitter, false news travels faster than true stories

Social networking

More mit news.

School of Engineering welcomes new faculty

Read full story →

Study explains why the brain can robustly recognize images, even without color

Turning up the heat on next-generation semiconductors

Sarah Millholland receives 2024 Vera Rubin Early Career Award

A community collaboration for progress

MIT scholars will take commercial break with entrepreneurial scholarship

- More news on MIT News homepage →

Massachusetts Institute of Technology 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA, USA

- Map (opens in new window)

- Events (opens in new window)

- People (opens in new window)

- Careers (opens in new window)

- Accessibility

- Social Media Hub

- MIT on Facebook

- MIT on YouTube

- MIT on Instagram

Skip to content

Feature Article — Dissecting Social Media: What You Should Know

Published on Aug 11, 2020

Parents PACK

Have you checked your Facebook News Feed recently? Watched a YouTube video? Posted on Instagram? Sent a Tweet? If so, you are among the 3.5 billion people worldwide who actively use social media.

Social media users generate a massive amount of information, from personal posts, photos and videos, to blogs, DIY articles and much more. While some content aims to entertain or inform, other information is intentionally meant to mislead or deceive. Those who intend to mislead rely on people sharing their messages to spread misinformation. As a result, it’s important to critically evaluate any information you see before sharing it further.

So, how can you tell which information is valid and which is not?

Read on to find some simple tips for checking posts. With a quick review, not only can you learn more about the reliability of what you are seeing, you can also help decrease the amount of bad information received by those in your network.

Looking at the parts of a post

1. headline.

- Does the headline sound true or was it designed to be sensational?

- Does the headline agree with the content of the story?

- Is the headline funny or satirical?

Example: “The CDC has adjusted their COVID19 deaths from 64,000 to 37,000. What do you think about that? Still scared? Angry yet?”

This headline appeared in a Facebook post to support a conspiracy theory that the pandemic is a hoax. FactCheck.org explained that the adjustments were the result of two lists maintained by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and why they were not in sync.

- Who wrote the post? If it is anonymous, this should raise a red flag.

- What do you know about the author? Is this an individual or someone representing an organization?

- Does the author claim to be an expert? Do the author’s credentials back up the claim?

- Does the author have an online profile? What kind of photo do they use on their profile? What is their screen name?

- Is the author selling something related to the topic?

Example: “OSHA 10&30 certified”

Several social media posts about the effectiveness of wearing face masks have misrepresented information provided by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). In one of them, shown on Snopes , the author claimed to be “OSHA 10&30 certified,” but OSHA confirmed that while they have training courses of 10 and 30 hours, the courses do not provide “certification,” nor do they cover COVID-19. In this case, the author was presenting misleading qualifications to sound like an expert.

In many cases, information will not come from the original source; it may have been forwarded by someone else in a person’s network. Often, people assume that because the person who sent it to them is reliable, they can trust the information. But, since not everyone checks the credibility of information before sharing it, users should be wary of any post. For these reasons, you will want to try to determine the original source:

- Who originally posted the information? Information shared on social media can be traced back to an original publication source by either clicking on the post or by searching for the original source online.

- How long has the source existed? New sources that have appeared to address a controversial issue might have a hidden agenda.

- Author’s name

- Publication date

- Organization’s mission and purpose

- Contact information

- Physical address

- Current copyright date

- Accurate reporting supported by evidence

- Links to other sources that back up the claim

If you can’t find the source or are not sure if the information is credible, it is best not to share it.

Example: “And the people stayed home” poem attributed to an author who lived through the 1918 influenza pandemic

A poem that went viral during the COVID-19 pandemic was misattributed to an author who lived through the “Spanish flu pandemic of 1919.” When Snopes traced back the original source of “And the people stayed home,” it found that the author wrote the poem in 2020 about the COVID-19 pandemic, not the 1918 Spanish flu.

- When was the post originally published? Is it recent? Old information often resurfaces on social media when it appears timely, so it is useful to check the date.

- Does the author seem biased?

- What evidence is offered to support the claims being made? If the author doesn’t offer evidence or if the “evidence” is only anecdotes or opinions, seek other sources for more information before believing what is being shared.

- Can the quotes be attributed to legitimate people? Are those people informed about the topic?

- What is the quality of the writing? Often, articles with noticeable typos or grammatical errors are a sign that the post is not legitimate.

- What do other sources say about this topic? The more outlandish something seems, the more important it is to see if other sources are reporting the same thing. Even when consuming legitimate news, it is important to check the story from a few different sources because they will have different viewpoints and may cover different details, which will allow you to piece together a more complete picture of the situation.

- Has the issue been addressed by fact checkers? Sites like FactCheck.org , PolitiFact.com and Snopes.com are just a few of the websites dedicated to fact-checking.

Example: Plandemic: The Hidden Agenda Behind COVID-19 documentary

When Plandemic: The Hidden Agenda Behind COVID-19 went viral with outlandish claims about SARS-CoV-2, fact-checkers got busy scrutinizing the content. Both PolitiFact and FactCheck.org highlighted a host of false and misleading claims related to the novel coronavirus pandemic, including its origins, vaccines, treatments and more. Plandemic had more than 8 million views in the first week of its release.

Visuals are increasingly becoming an issue as more people edit images to make them align with a particular viewpoint of the story being told. This is especially true of those who intend to misinform or deceive.

- Does the photo appear shocking, particularly engaging, or simply out of place? Try using Google Images or TinEye to find the original photo. In particular, look for any signs that the image has been altered, such as people or things that were not part of the original photo.

- When and where was the original photo taken? Often old images are used to represent current topics, particularly on social media.

- Is a video or audio soundbite being used? If so, try to find the original video or recording so you can evaluate the context for which it was meant.

Example: Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation building

A side-by-side comparison of an original photo of the exterior of a Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation building alongside a doctored photo clearly shows alterations. A quick Google Image search brings up many original, unaltered copies of the photo.

In conclusion, as you use these tips more often, you will get faster and better at recognizing misinformation and deception. By thinking critically, looking for the small details, listening to different perspectives, and fact-checking, the spread of misinformation can stop with you.

Download a PDF version of this article.

For more information

Fact-checking websites.

- FactCheck.org

- The Washington Post Fact Checker

Additional resources

- News Literacy Project (NLP) — Provides information for educators and the public to help them become active consumers of news and information.

- Informable mobile App — A free app by the News Literacy Project aims to help players practice differentiating between good and bad information they find online.

- AllSides — Provides media bias ratings for hundreds of media outlets and writers to help the public identify different perspectives.

Categories: Parents PACK August 2020 , Feature Article

Materials in this section are updated as new information and vaccines become available. The Vaccine Education Center staff regularly reviews materials for accuracy.

You should not consider the information in this site to be specific, professional medical advice for your personal health or for your family's personal health. You should not use it to replace any relationship with a physician or other qualified healthcare professional. For medical concerns, including decisions about vaccinations, medications and other treatments, you should always consult your physician or, in serious cases, seek immediate assistance from emergency personnel.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

student opinion

How Does Social Media Affect Your Mental Health?

Facebook has delayed the development of an Instagram app for children amid questions about its harmful effects on young people’s mental health. Does social media have an impact on your well-being?

By Nicole Daniels

What is your relationship with social media like? Which platforms do you spend the most time on? Which do you stay away from? How often do you log on?

What do you notice about your mental health and well-being when spending time on social networks?

In “ Facebook Delays Instagram App for Users 13 and Younger ,” Adam Satariano and Ryan Mac write about the findings of an internal study conducted by Facebook and what they mean for the Instagram Kids app that the company was developing:

Facebook said on Monday that it had paused development of an Instagram Kids service that would be tailored for children 13 years old or younger, as the social network increasingly faces questions about the app’s effect on young people’s mental health. The pullback preceded a congressional hearing this week about internal research conducted by Facebook , and reported in The Wall Street Journal , that showed the company knew of the harmful mental health effects that Instagram was having on teenage girls. The revelations have set off a public relations crisis for the Silicon Valley company and led to a fresh round of calls for new regulation. Facebook said it still wanted to build an Instagram product intended for children that would have a more “age appropriate experience,” but was postponing the plans in the face of criticism.

The article continues:

With Instagram Kids, Facebook had argued that young people were using the photo-sharing app anyway, despite age-requirement rules, so it would be better to develop a version more suitable for them. Facebook said the “kids” app was intended for ages 10 to 12 and would require parental permission to join, forgo ads and carry more age-appropriate content and features. Parents would be able to control what accounts their child followed. YouTube, which Google owns, has released a children’s version of its app. But since BuzzFeed broke the news this year that Facebook was working on the app, the company has faced scrutiny. Policymakers, regulators, child safety groups and consumer rights groups have argued that it hooks children on the app at a younger age rather than protecting them from problems with the service, including child predatory grooming, bullying and body shaming.

The article goes on to quote Adam Mosseri, the head of Instagram:

Mr. Mosseri said on Monday that the “the project leaked way before we knew what it would be” and that the company had “few answers” for the public at the time. Opposition to Facebook’s plans gained momentum this month when The Journal published articles based on leaked internal documents that showed Facebook knew about many of the harms it was causing. Facebook’s internal research showed that Instagram, in particular, had caused teen girls to feel worse about their bodies and led to increased rates of anxiety and depression, even while company executives publicly tried to minimize the app’s downsides.

But concerns about the effect of social media on young people go beyond Instagram Kids, the article notes:

A children’s version of Instagram would not fix more systemic problems, said Al Mik, a spokesman for 5Rights Foundation, a London group focused on digital rights issues for children. The group published a report in July showing that children as young as 13 were targeted within 24 hours of creating an account with harmful content, including material related to eating disorders, extreme diets, sexualized imagery, body shaming, self-harm and suicide. “Big Tobacco understood that the younger you got to someone, the easier you could get them addicted to become a lifelong user,” Doug Peterson, Nebraska’s attorney general, said in an interview. “I see some comparisons to social media platforms.” In May, attorneys general from 44 states and jurisdictions had signed a letter to Facebook’s chief executive, Mark Zuckerberg, asking him to end plans for building an Instagram app for children. American policymakers should pass tougher laws to restrict how tech platforms target children, said Josh Golin, executive director of Fairplay, a Boston-based group that was part of an international coalition of children’s and consumer groups opposed to the new app. Last year, Britain adopted an Age Appropriate Design Code , which requires added privacy protections for digital services used by people under the age of 18.

Students, read the entire article , then tell us:

Do you think Facebook made the right decision in halting the development of the Instagram Kids app? Do you think there should be social media apps for children 13 and younger? Why or why not?

What is your reaction to the research that found that Instagram can have harmful mental health effects on teenagers, particularly teenage girls? Have you experienced body image issues, anxiety or depression tied to your use of the app? How do you think social media affects your mental health?

What has your experience been on different social media apps? Are there apps that have a more positive or negative effect on your well-being? What do you think could explain these differences?

Have you ever been targeted with inappropriate or harmful content on Instagram or other social media apps? What responsibility do you think social media companies have to address these issues? Do you think there should be more protections in place for users under 18? Why or why not?

What does healthy social media engagement look like for you? What habits do you have around social media that you feel proud of? What behaviors would you like to change? How involved are your parents in your social media use? How involved do you think they should be?

If you were in charge of making Instagram, or another social media app, safer for teenagers, what changes would you make?

Want more writing prompts? You can find all of our questions in our Student Opinion column . Teachers, check out this guide to learn how you can incorporate them into your classroom.

Students 13 and older in the United States and Britain, and 16 and older elsewhere, are invited to comment. All comments are moderated by the Learning Network staff, but please keep in mind that once your comment is accepted, it will be made public.

Nicole Daniels joined The Learning Network as a staff editor in 2019 after working in museum education, curriculum writing and bilingual education. More about Nicole Daniels

Subscribe or renew today

Every print subscription comes with full digital access

Science News

Social media harms teens’ mental health, mounting evidence shows. what now.

Understanding what is going on in teens’ minds is necessary for targeted policy suggestions

Most teens use social media, often for hours on end. Some social scientists are confident that such use is harming their mental health. Now they want to pinpoint what explains the link.

Carol Yepes/Getty Images

Share this:

By Sujata Gupta

February 20, 2024 at 7:30 am

In January, Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Facebook’s parent company Meta, appeared at a congressional hearing to answer questions about how social media potentially harms children. Zuckerberg opened by saying: “The existing body of scientific work has not shown a causal link between using social media and young people having worse mental health.”

But many social scientists would disagree with that statement. In recent years, studies have started to show a causal link between teen social media use and reduced well-being or mood disorders, chiefly depression and anxiety.

Ironically, one of the most cited studies into this link focused on Facebook.

Researchers delved into whether the platform’s introduction across college campuses in the mid 2000s increased symptoms associated with depression and anxiety. The answer was a clear yes , says MIT economist Alexey Makarin, a coauthor of the study, which appeared in the November 2022 American Economic Review . “There is still a lot to be explored,” Makarin says, but “[to say] there is no causal evidence that social media causes mental health issues, to that I definitely object.”

The concern, and the studies, come from statistics showing that social media use in teens ages 13 to 17 is now almost ubiquitous. Two-thirds of teens report using TikTok, and some 60 percent of teens report using Instagram or Snapchat, a 2022 survey found. (Only 30 percent said they used Facebook.) Another survey showed that girls, on average, allot roughly 3.4 hours per day to TikTok, Instagram and Facebook, compared with roughly 2.1 hours among boys. At the same time, more teens are showing signs of depression than ever, especially girls ( SN: 6/30/23 ).

As more studies show a strong link between these phenomena, some researchers are starting to shift their attention to possible mechanisms. Why does social media use seem to trigger mental health problems? Why are those effects unevenly distributed among different groups, such as girls or young adults? And can the positives of social media be teased out from the negatives to provide more targeted guidance to teens, their caregivers and policymakers?

“You can’t design good public policy if you don’t know why things are happening,” says Scott Cunningham, an economist at Baylor University in Waco, Texas.

Increasing rigor

Concerns over the effects of social media use in children have been circulating for years, resulting in a massive body of scientific literature. But those mostly correlational studies could not show if teen social media use was harming mental health or if teens with mental health problems were using more social media.

Moreover, the findings from such studies were often inconclusive, or the effects on mental health so small as to be inconsequential. In one study that received considerable media attention, psychologists Amy Orben and Andrew Przybylski combined data from three surveys to see if they could find a link between technology use, including social media, and reduced well-being. The duo gauged the well-being of over 355,000 teenagers by focusing on questions around depression, suicidal thinking and self-esteem.

Digital technology use was associated with a slight decrease in adolescent well-being , Orben, now of the University of Cambridge, and Przybylski, of the University of Oxford, reported in 2019 in Nature Human Behaviour . But the duo downplayed that finding, noting that researchers have observed similar drops in adolescent well-being associated with drinking milk, going to the movies or eating potatoes.

Holes have begun to appear in that narrative thanks to newer, more rigorous studies.

In one longitudinal study, researchers — including Orben and Przybylski — used survey data on social media use and well-being from over 17,400 teens and young adults to look at how individuals’ responses to a question gauging life satisfaction changed between 2011 and 2018. And they dug into how the responses varied by gender, age and time spent on social media.

Social media use was associated with a drop in well-being among teens during certain developmental periods, chiefly puberty and young adulthood, the team reported in 2022 in Nature Communications . That translated to lower well-being scores around ages 11 to 13 for girls and ages 14 to 15 for boys. Both groups also reported a drop in well-being around age 19. Moreover, among the older teens, the team found evidence for the Goldilocks Hypothesis: the idea that both too much and too little time spent on social media can harm mental health.

“There’s hardly any effect if you look over everybody. But if you look at specific age groups, at particularly what [Orben] calls ‘windows of sensitivity’ … you see these clear effects,” says L.J. Shrum, a consumer psychologist at HEC Paris who was not involved with this research. His review of studies related to teen social media use and mental health is forthcoming in the Journal of the Association for Consumer Research.

Cause and effect

That longitudinal study hints at causation, researchers say. But one of the clearest ways to pin down cause and effect is through natural or quasi-experiments. For these in-the-wild experiments, researchers must identify situations where the rollout of a societal “treatment” is staggered across space and time. They can then compare outcomes among members of the group who received the treatment to those still in the queue — the control group.

That was the approach Makarin and his team used in their study of Facebook. The researchers homed in on the staggered rollout of Facebook across 775 college campuses from 2004 to 2006. They combined that rollout data with student responses to the National College Health Assessment, a widely used survey of college students’ mental and physical health.

The team then sought to understand if those survey questions captured diagnosable mental health problems. Specifically, they had roughly 500 undergraduate students respond to questions both in the National College Health Assessment and in validated screening tools for depression and anxiety. They found that mental health scores on the assessment predicted scores on the screenings. That suggested that a drop in well-being on the college survey was a good proxy for a corresponding increase in diagnosable mental health disorders.

Compared with campuses that had not yet gained access to Facebook, college campuses with Facebook experienced a 2 percentage point increase in the number of students who met the diagnostic criteria for anxiety or depression, the team found.

When it comes to showing a causal link between social media use in teens and worse mental health, “that study really is the crown jewel right now,” says Cunningham, who was not involved in that research.

A need for nuance

The social media landscape today is vastly different than the landscape of 20 years ago. Facebook is now optimized for maximum addiction, Shrum says, and other newer platforms, such as Snapchat, Instagram and TikTok, have since copied and built on those features. Paired with the ubiquity of social media in general, the negative effects on mental health may well be larger now.

Moreover, social media research tends to focus on young adults — an easier cohort to study than minors. That needs to change, Cunningham says. “Most of us are worried about our high school kids and younger.”

And so, researchers must pivot accordingly. Crucially, simple comparisons of social media users and nonusers no longer make sense. As Orben and Przybylski’s 2022 work suggested, a teen not on social media might well feel worse than one who briefly logs on.

Researchers must also dig into why, and under what circumstances, social media use can harm mental health, Cunningham says. Explanations for this link abound. For instance, social media is thought to crowd out other activities or increase people’s likelihood of comparing themselves unfavorably with others. But big data studies, with their reliance on existing surveys and statistical analyses, cannot address those deeper questions. “These kinds of papers, there’s nothing you can really ask … to find these plausible mechanisms,” Cunningham says.

One ongoing effort to understand social media use from this more nuanced vantage point is the SMART Schools project out of the University of Birmingham in England. Pedagogical expert Victoria Goodyear and her team are comparing mental and physical health outcomes among children who attend schools that have restricted cell phone use to those attending schools without such a policy. The researchers described the protocol of that study of 30 schools and over 1,000 students in the July BMJ Open.

Goodyear and colleagues are also combining that natural experiment with qualitative research. They met with 36 five-person focus groups each consisting of all students, all parents or all educators at six of those schools. The team hopes to learn how students use their phones during the day, how usage practices make students feel, and what the various parties think of restrictions on cell phone use during the school day.

Talking to teens and those in their orbit is the best way to get at the mechanisms by which social media influences well-being — for better or worse, Goodyear says. Moving beyond big data to this more personal approach, however, takes considerable time and effort. “Social media has increased in pace and momentum very, very quickly,” she says. “And research takes a long time to catch up with that process.”

Until that catch-up occurs, though, researchers cannot dole out much advice. “What guidance could we provide to young people, parents and schools to help maintain the positives of social media use?” Goodyear asks. “There’s not concrete evidence yet.”

More Stories from Science News on Science & Society

Should we use AI to resurrect digital ‘ghosts’ of the dead?

A hidden danger lurks beneath Yellowstone

Online spaces may intensify teens’ uncertainty in social interactions

Want to see butterflies in your backyard? Try doing less yardwork

Ximena Velez-Liendo is saving Andean bears with honey

‘Flavorama’ guides readers through the complex landscape of flavor

Rain Bosworth studies how deaf children experience the world

Separating science fact from fiction in Netflix’s ‘3 Body Problem’

Subscribers, enter your e-mail address for full access to the Science News archives and digital editions.

Not a subscriber? Become one now .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Effects of Social Media Use on Psychological Well-Being: A Mediated Model

Dragana ostic.

1 School of Finance and Economics, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, China

Sikandar Ali Qalati

Belem barbosa.

2 Research Unit of Governance, Competitiveness, and Public Policies (GOVCOPP), Center for Economics and Finance (cef.up), School of Economics and Management, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal

Syed Mir Muhammad Shah

3 Department of Business Administration, Sukkur Institute of Business Administration (IBA) University, Sukkur, Pakistan

Esthela Galvan Vela

4 CETYS Universidad, Tijuana, Mexico

Ahmed Muhammad Herzallah

5 Department of Business Administration, Al-Quds University, Jerusalem, Israel

6 Business School, Shandong University, Weihai, China

Associated Data

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The growth in social media use has given rise to concerns about the impacts it may have on users' psychological well-being. This paper's main objective is to shed light on the effect of social media use on psychological well-being. Building on contributions from various fields in the literature, it provides a more comprehensive study of the phenomenon by considering a set of mediators, including social capital types (i.e., bonding social capital and bridging social capital), social isolation, and smartphone addiction. The paper includes a quantitative study of 940 social media users from Mexico, using structural equation modeling (SEM) to test the proposed hypotheses. The findings point to an overall positive indirect impact of social media usage on psychological well-being, mainly due to the positive effect of bonding and bridging social capital. The empirical model's explanatory power is 45.1%. This paper provides empirical evidence and robust statistical analysis that demonstrates both positive and negative effects coexist, helping to reconcile the inconsistencies found so far in the literature.

Introduction

The use of social media has grown substantially in recent years (Leong et al., 2019 ; Kemp, 2020 ). Social media refers to “the websites and online tools that facilitate interactions between users by providing them opportunities to share information, opinions, and interest” (Swar and Hameed, 2017 , p. 141). Individuals use social media for many reasons, including entertainment, communication, and searching for information. Notably, adolescents and young adults are spending an increasing amount of time on online networking sites, e-games, texting, and other social media (Twenge and Campbell, 2019 ). In fact, some authors (e.g., Dhir et al., 2018 ; Tateno et al., 2019 ) have suggested that social media has altered the forms of group interaction and its users' individual and collective behavior around the world.

Consequently, there are increased concerns regarding the possible negative impacts associated with social media usage addiction (Swar and Hameed, 2017 ; Kircaburun et al., 2020 ), particularly on psychological well-being (Chotpitayasunondh and Douglas, 2016 ; Jiao et al., 2017 ; Choi and Noh, 2019 ; Chatterjee, 2020 ). Smartphones sometimes distract their users from relationships and social interaction (Chotpitayasunondh and Douglas, 2016 ; Li et al., 2020a ), and several authors have stressed that the excessive use of social media may lead to smartphone addiction (Swar and Hameed, 2017 ; Leong et al., 2019 ), primarily because of the fear of missing out (Reer et al., 2019 ; Roberts and David, 2020 ). Social media usage has been associated with anxiety, loneliness, and depression (Dhir et al., 2018 ; Reer et al., 2019 ), social isolation (Van Den Eijnden et al., 2016 ; Whaite et al., 2018 ), and “phubbing,” which refers to the extent to which an individual uses, or is distracted by, their smartphone during face-to-face communication with others (Chotpitayasunondh and Douglas, 2016 ; Jiao et al., 2017 ; Choi and Noh, 2019 ; Chatterjee, 2020 ).

However, social media use also contributes to building a sense of connectedness with relevant others (Twenge and Campbell, 2019 ), which may reduce social isolation. Indeed, social media provides several ways to interact both with close ties, such as family, friends, and relatives, and weak ties, including coworkers, acquaintances, and strangers (Chen and Li, 2017 ), and plays a key role among people of all ages as they exploit their sense of belonging in different communities (Roberts and David, 2020 ). Consequently, despite the fears regarding the possible negative impacts of social media usage on well-being, there is also an increasing number of studies highlighting social media as a new communication channel (Twenge and Campbell, 2019 ; Barbosa et al., 2020 ), stressing that it can play a crucial role in developing one's presence, identity, and reputation, thus facilitating social interaction, forming and maintaining relationships, and sharing ideas (Carlson et al., 2016 ), which consequently may be significantly correlated to social support (Chen and Li, 2017 ; Holliman et al., 2021 ). Interestingly, recent studies (e.g., David et al., 2018 ; Bano et al., 2019 ; Barbosa et al., 2020 ) have suggested that the impact of smartphone usage on psychological well-being depends on the time spent on each type of application and the activities that users engage in.

Hence, the literature provides contradictory cues regarding the impacts of social media on users' well-being, highlighting both the possible negative impacts and the social enhancement it can potentially provide. In line with views on the need to further investigate social media usage (Karikari et al., 2017 ), particularly regarding its societal implications (Jiao et al., 2017 ), this paper argues that there is an urgent need to further understand the impact of the time spent on social media on users' psychological well-being, namely by considering other variables that mediate and further explain this effect.

One of the relevant perspectives worth considering is that provided by social capital theory, which is adopted in this paper. Social capital theory has previously been used to study how social media usage affects psychological well-being (e.g., Bano et al., 2019 ). However, extant literature has so far presented only partial models of associations that, although statistically acceptable and contributing to the understanding of the scope of social networks, do not provide as comprehensive a vision of the phenomenon as that proposed within this paper. Furthermore, the contradictory views, suggesting both negative (e.g., Chotpitayasunondh and Douglas, 2016 ; Van Den Eijnden et al., 2016 ; Jiao et al., 2017 ; Whaite et al., 2018 ; Choi and Noh, 2019 ; Chatterjee, 2020 ) and positive impacts (Carlson et al., 2016 ; Chen and Li, 2017 ; Twenge and Campbell, 2019 ) of social media on psychological well-being, have not been adequately explored.

Given this research gap, this paper's main objective is to shed light on the effect of social media use on psychological well-being. As explained in detail in the next section, this paper explores the mediating effect of bonding and bridging social capital. To provide a broad view of the phenomenon, it also considers several variables highlighted in the literature as affecting the relationship between social media usage and psychological well-being, namely smartphone addiction, social isolation, and phubbing. The paper utilizes a quantitative study conducted in Mexico, comprising 940 social media users, and uses structural equation modeling (SEM) to test a set of research hypotheses.

This article provides several contributions. First, it adds to existing literature regarding the effect of social media use on psychological well-being and explores the contradictory indications provided by different approaches. Second, it proposes a conceptual model that integrates complementary perspectives on the direct and indirect effects of social media use. Third, it offers empirical evidence and robust statistical analysis that demonstrates that both positive and negative effects coexist, helping resolve the inconsistencies found so far in the literature. Finally, this paper provides insights on how to help reduce the potential negative effects of social media use, as it demonstrates that, through bridging and bonding social capital, social media usage positively impacts psychological well-being. Overall, the article offers valuable insights for academics, practitioners, and society in general.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section Literature Review presents a literature review focusing on the factors that explain the impact of social media usage on psychological well-being. Based on the literature review, a set of hypotheses are defined, resulting in the proposed conceptual model, which includes both the direct and indirect effects of social media usage on psychological well-being. Section Research Methodology explains the methodological procedures of the research, followed by the presentation and discussion of the study's results in section Results. Section Discussion is dedicated to the conclusions and includes implications, limitations, and suggestions for future research.

Literature Review

Putnam ( 1995 , p. 664–665) defined social capital as “features of social life – networks, norms, and trust – that enable participants to act together more effectively to pursue shared objectives.” Li and Chen ( 2014 , p. 117) further explained that social capital encompasses “resources embedded in one's social network, which can be assessed and used for instrumental or expressive returns such as mutual support, reciprocity, and cooperation.”

Putnam ( 1995 , 2000 ) conceptualized social capital as comprising two dimensions, bridging and bonding, considering the different norms and networks in which they occur. Bridging social capital refers to the inclusive nature of social interaction and occurs when individuals from different origins establish connections through social networks. Hence, bridging social capital is typically provided by heterogeneous weak ties (Li and Chen, 2014 ). This dimension widens individual social horizons and perspectives and provides extended access to resources and information. Bonding social capital refers to the social and emotional support each individual receives from his or her social networks, particularly from close ties (e.g., family and friends).

Overall, social capital is expected to be positively associated with psychological well-being (Bano et al., 2019 ). Indeed, Williams ( 2006 ) stressed that interaction generates affective connections, resulting in positive impacts, such as emotional support. The following sub-sections use the lens of social capital theory to explore further the relationship between the use of social media and psychological well-being.

Social Media Use, Social Capital, and Psychological Well-Being

The effects of social media usage on social capital have gained increasing scholarly attention, and recent studies have highlighted a positive relationship between social media use and social capital (Brown and Michinov, 2019 ; Tefertiller et al., 2020 ). Li and Chen ( 2014 ) hypothesized that the intensity of Facebook use by Chinese international students in the United States was positively related to social capital forms. A longitudinal survey based on the quota sampling approach illustrated the positive effects of social media use on the two social capital dimensions (Chen and Li, 2017 ). Abbas and Mesch ( 2018 ) argued that, as Facebook usage increases, it will also increase users' social capital. Karikari et al. ( 2017 ) also found positive effects of social media use on social capital. Similarly, Pang ( 2018 ) studied Chinese students residing in Germany and found positive effects of social networking sites' use on social capital, which, in turn, was positively associated with psychological well-being. Bano et al. ( 2019 ) analyzed the 266 students' data and found positive effects of WhatsApp use on social capital forms and the positive effect of social capital on psychological well-being, emphasizing the role of social integration in mediating this positive effect.