An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Case control studies.

Steven Tenny ; Connor C. Kerndt ; Mary R. Hoffman .

Affiliations

Last Update: March 27, 2023 .

- Introduction

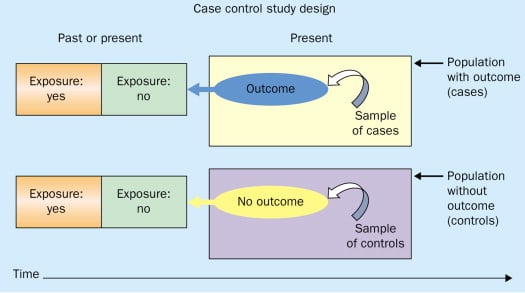

A case-control study is a type of observational study commonly used to look at factors associated with diseases or outcomes. [1] The case-control study starts with a group of cases, which are the individuals who have the outcome of interest. The researcher then tries to construct a second group of individuals called the controls, who are similar to the case individuals but do not have the outcome of interest. The researcher then looks at historical factors to identify if some exposure(s) is/are found more commonly in the cases than the controls. If the exposure is found more commonly in the cases than in the controls, the researcher can hypothesize that the exposure may be linked to the outcome of interest.

For example, a researcher may want to look at the rare cancer Kaposi's sarcoma. The researcher would find a group of individuals with Kaposi's sarcoma (the cases) and compare them to a group of patients who are similar to the cases in most ways but do not have Kaposi's sarcoma (controls). The researcher could then ask about various exposures to see if any exposure is more common in those with Kaposi's sarcoma (the cases) than those without Kaposi's sarcoma (the controls). The researcher might find that those with Kaposi's sarcoma are more likely to have HIV, and thus conclude that HIV may be a risk factor for the development of Kaposi's sarcoma.

There are many advantages to case-control studies. First, the case-control approach allows for the study of rare diseases. If a disease occurs very infrequently, one would have to follow a large group of people for a long period of time to accrue enough incident cases to study. Such use of resources may be impractical, so a case-control study can be useful for identifying current cases and evaluating historical associated factors. For example, if a disease developed in 1 in 1000 people per year (0.001/year) then in ten years one would expect about 10 cases of a disease to exist in a group of 1000 people. If the disease is much rarer, say 1 in 1,000,0000 per year (0.0000001/year) this would require either having to follow 1,000,0000 people for ten years or 1000 people for 1000 years to accrue ten total cases. As it may be impractical to follow 1,000,000 for ten years or to wait 1000 years for recruitment, a case-control study allows for a more feasible approach.

Second, the case-control study design makes it possible to look at multiple risk factors at once. In the example above about Kaposi's sarcoma, the researcher could ask both the cases and controls about exposures to HIV, asbestos, smoking, lead, sunburns, aniline dye, alcohol, herpes, human papillomavirus, or any number of possible exposures to identify those most likely associated with Kaposi's sarcoma.

Case-control studies can also be very helpful when disease outbreaks occur, and potential links and exposures need to be identified. This study mechanism can be commonly seen in food-related disease outbreaks associated with contaminated products, or when rare diseases start to increase in frequency, as has been seen with measles in recent years.

Because of these advantages, case-control studies are commonly used as one of the first studies to build evidence of an association between exposure and an event or disease.

In a case-control study, the investigator can include unequal numbers of cases with controls such as 2:1 or 4:1 to increase the power of the study.

Disadvantages and Limitations

The most commonly cited disadvantage in case-control studies is the potential for recall bias. [2] Recall bias in a case-control study is the increased likelihood that those with the outcome will recall and report exposures compared to those without the outcome. In other words, even if both groups had exactly the same exposures, the participants in the cases group may report the exposure more often than the controls do. Recall bias may lead to concluding that there are associations between exposure and disease that do not, in fact, exist. It is due to subjects' imperfect memories of past exposures. If people with Kaposi's sarcoma are asked about exposure and history (e.g., HIV, asbestos, smoking, lead, sunburn, aniline dye, alcohol, herpes, human papillomavirus), the individuals with the disease are more likely to think harder about these exposures and recall having some of the exposures that the healthy controls.

Case-control studies, due to their typically retrospective nature, can be used to establish a correlation between exposures and outcomes, but cannot establish causation . These studies simply attempt to find correlations between past events and the current state.

When designing a case-control study, the researcher must find an appropriate control group. Ideally, the case group (those with the outcome) and the control group (those without the outcome) will have almost the same characteristics, such as age, gender, overall health status, and other factors. The two groups should have similar histories and live in similar environments. If, for example, our cases of Kaposi's sarcoma came from across the country but our controls were only chosen from a small community in northern latitudes where people rarely go outside or get sunburns, asking about sunburn may not be a valid exposure to investigate. Similarly, if all of the cases of Kaposi's sarcoma were found to come from a small community outside a battery factory with high levels of lead in the environment, then controls from across the country with minimal lead exposure would not provide an appropriate control group. The investigator must put a great deal of effort into creating a proper control group to bolster the strength of the case-control study as well as enhance their ability to find true and valid potential correlations between exposures and disease states.

Similarly, the researcher must recognize the potential for failing to identify confounding variables or exposures, introducing the possibility of confounding bias, which occurs when a variable that is not being accounted for that has a relationship with both the exposure and outcome. This can cause us to accidentally be studying something we are not accounting for but that may be systematically different between the groups.

The major method for analyzing results in case-control studies is the odds ratio (OR). The odds ratio is the odds of having a disease (or outcome) with the exposure versus the odds of having the disease without the exposure. The most straightforward way to calculate the odds ratio is with a 2 by 2 table divided by exposure and disease status (see below). Mathematically we can write the odds ratio as follows.

Odds ratio = [(Number exposed with disease)/(Number exposed without disease) ]/[(Number not exposed to disease)/(Number not exposed without disease) ]

This can be rewritten as:

Odds ratio = [ (Number exposed with disease) x (Number not exposed without disease) ] / [ (Number exposed without disease ) x (Number not exposed with disease) ]

The odds ratio tells us how strongly the exposure is related to the disease state. An odds ratio of greater than one implies the disease is more likely with exposure. An odds ratio of less than one implies the disease is less likely with exposure and thus the exposure may be protective. For example, a patient with a prior heart attack taking a daily aspirin has a decreased odds of having another heart attack (odds ratio less than one). An odds ratio of one implies there is no relation between the exposure and the disease process.

Odds ratios are often confused with Relative Risk (RR), which is a measure of the probability of the disease or outcome in the exposed vs unexposed groups. For very rare conditions, the OR and RR may be very similar, but they are measuring different aspects of the association between outcome and exposure. The OR is used in case-control studies because RR cannot be estimated; whereas in randomized clinical trials, a direct measurement of the development of events in the exposed and unexposed groups can be seen. RR is also used to compare risk in other prospective study designs.

- Issues of Concern

The main issues of concern with a case-control study are recall bias, its retrospective nature, the need for a careful collection of measured variables, and the selection of an appropriate control group. [3] These are discussed above in the disadvantages section.

- Clinical Significance

A case-control study is a good tool for exploring risk factors for rare diseases or when other study types are not feasible. Many times an investigator will hypothesize a list of possible risk factors for a disease process and will then use a case-control study to see if there are any possible associations between the risk factors and the disease process. The investigator can then use the data from the case-control study to focus on a few of the most likely causative factors and develop additional hypotheses or questions. Then through further exploration, often using other study types (such as cohort studies or randomized clinical studies) the researcher may be able to develop further support for the evidence of the possible association between the exposure and the outcome.

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Case-control studies are prevalent in all fields of medicine from nursing and pharmacy to use in public health and surgical patients. Case-control studies are important for each member of the health care team to not only understand their common occurrence in research but because each part of the health care team has parts to contribute to such studies. One of the most important things each party provides is helping identify correct controls for the cases. Matching the controls across a spectrum of factors outside of the elements of interest take input from nurses, pharmacists, social workers, physicians, demographers, and more. Failure for adequate selection of controls can lead to invalid study conclusions and invalidate the entire study.

- Review Questions

- Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

- Comment on this article.

2x2 table with calculations for the odds ratio and 95% confidence interval for the odds ratio Contributed by Steven Tenny MD, MPH, MBA

Disclosure: Steven Tenny declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Connor Kerndt declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Mary Hoffman declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

- Cite this Page Tenny S, Kerndt CC, Hoffman MR. Case Control Studies. [Updated 2023 Mar 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

In this Page

Bulk download.

- Bulk download StatPearls data from FTP

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Similar articles in PubMed

- Suicidal Ideation. [StatPearls. 2024] Suicidal Ideation. Harmer B, Lee S, Rizvi A, Saadabadi A. StatPearls. 2024 Jan

- Qualitative Study. [StatPearls. 2024] Qualitative Study. Tenny S, Brannan JM, Brannan GD. StatPearls. 2024 Jan

- Folic acid supplementation and malaria susceptibility and severity among people taking antifolate antimalarial drugs in endemic areas. [Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022] Folic acid supplementation and malaria susceptibility and severity among people taking antifolate antimalarial drugs in endemic areas. Crider K, Williams J, Qi YP, Gutman J, Yeung L, Mai C, Finkelstain J, Mehta S, Pons-Duran C, Menéndez C, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022 Feb 1; 2(2022). Epub 2022 Feb 1.

- Review The epidemiology of classic, African, and immunosuppressed Kaposi's sarcoma. [Epidemiol Rev. 1991] Review The epidemiology of classic, African, and immunosuppressed Kaposi's sarcoma. Wahman A, Melnick SL, Rhame FS, Potter JD. Epidemiol Rev. 1991; 13:178-99.

- Review Epidemiology of Kaposi's sarcoma. [Cancer Surv. 1991] Review Epidemiology of Kaposi's sarcoma. Beral V. Cancer Surv. 1991; 10:5-22.

Recent Activity

- Case Control Studies - StatPearls Case Control Studies - StatPearls

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

Study Design 101: Case Control Study

- Case Report

- Case Control Study

- Cohort Study

- Randomized Controlled Trial

- Practice Guideline

- Systematic Review

- Meta-Analysis

- Helpful Formulas

- Finding Specific Study Types

A study that compares patients who have a disease or outcome of interest (cases) with patients who do not have the disease or outcome (controls), and looks back retrospectively to compare how frequently the exposure to a risk factor is present in each group to determine the relationship between the risk factor and the disease.

Case control studies are observational because no intervention is attempted and no attempt is made to alter the course of the disease. The goal is to retrospectively determine the exposure to the risk factor of interest from each of the two groups of individuals: cases and controls. These studies are designed to estimate odds.

Case control studies are also known as "retrospective studies" and "case-referent studies."

- Good for studying rare conditions or diseases

- Less time needed to conduct the study because the condition or disease has already occurred

- Lets you simultaneously look at multiple risk factors

- Useful as initial studies to establish an association

- Can answer questions that could not be answered through other study designs

Disadvantages

- Retrospective studies have more problems with data quality because they rely on memory and people with a condition will be more motivated to recall risk factors (also called recall bias).

- Not good for evaluating diagnostic tests because it's already clear that the cases have the condition and the controls do not

- It can be difficult to find a suitable control group

Design pitfalls to look out for

Care should be taken to avoid confounding, which arises when an exposure and an outcome are both strongly associated with a third variable. Controls should be subjects who might have been cases in the study but are selected independent of the exposure. Cases and controls should also not be "over-matched."

Is the control group appropriate for the population? Does the study use matching or pairing appropriately to avoid the effects of a confounding variable? Does it use appropriate inclusion and exclusion criteria?

Fictitious Example

There is a suspicion that zinc oxide, the white non-absorbent sunscreen traditionally worn by lifeguards is more effective at preventing sunburns that lead to skin cancer than absorbent sunscreen lotions. A case-control study was conducted to investigate if exposure to zinc oxide is a more effective skin cancer prevention measure. The study involved comparing a group of former lifeguards that had developed cancer on their cheeks and noses (cases) to a group of lifeguards without this type of cancer (controls) and assess their prior exposure to zinc oxide or absorbent sunscreen lotions.

This study would be retrospective in that the former lifeguards would be asked to recall which type of sunscreen they used on their face and approximately how often. This could be either a matched or unmatched study, but efforts would need to be made to ensure that the former lifeguards are of the same average age, and lifeguarded for a similar number of seasons and amount of time per season.

Real-life Examples

Boubekri, M., Cheung, I., Reid, K., Wang, C., & Zee, P. (2014). Impact of windows and daylight exposure on overall health and sleep quality of office workers: a case-control pilot study. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine : JCSM : Official Publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 10 (6), 603-611. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.3780

This pilot study explored the impact of exposure to daylight on the health of office workers (measuring well-being and sleep quality subjectively, and light exposure, activity level and sleep-wake patterns via actigraphy). Individuals with windows in their workplaces had more light exposure, longer sleep duration, and more physical activity. They also reported a better scores in the areas of vitality and role limitations due to physical problems, better sleep quality and less sleep disturbances.

Togha, M., Razeghi Jahromi, S., Ghorbani, Z., Martami, F., & Seifishahpar, M. (2018). Serum Vitamin D Status in a Group of Migraine Patients Compared With Healthy Controls: A Case-Control Study. Headache, 58 (10), 1530-1540. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13423

This case-control study compared serum vitamin D levels in individuals who experience migraine headaches with their matched controls. Studied over a period of thirty days, individuals with higher levels of serum Vitamin D was associated with lower odds of migraine headache.

Related Formulas

- Odds ratio in an unmatched study

- Odds ratio in a matched study

Related Terms

A patient with the disease or outcome of interest.

Confounding

When an exposure and an outcome are both strongly associated with a third variable.

A patient who does not have the disease or outcome.

Matched Design

Each case is matched individually with a control according to certain characteristics such as age and gender. It is important to remember that the concordant pairs (pairs in which the case and control are either both exposed or both not exposed) tell us nothing about the risk of exposure separately for cases or controls.

Observed Assignment

The method of assignment of individuals to study and control groups in observational studies when the investigator does not intervene to perform the assignment.

Unmatched Design

The controls are a sample from a suitable non-affected population.

Now test yourself!

1. Case Control Studies are prospective in that they follow the cases and controls over time and observe what occurs.

a) True b) False

2. Which of the following is an advantage of Case Control Studies?

a) They can simultaneously look at multiple risk factors. b) They are useful to initially establish an association between a risk factor and a disease or outcome. c) They take less time to complete because the condition or disease has already occurred. d) b and c only e) a, b, and c

Evidence Pyramid - Navigation

- Meta- Analysis

- Case Reports

- << Previous: Case Report

- Next: Cohort Study >>

- Last Updated: Sep 25, 2023 10:59 AM

- URL: https://guides.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/studydesign101

- Himmelfarb Intranet

- Privacy Notice

- Terms of Use

- GW is committed to digital accessibility. If you experience a barrier that affects your ability to access content on this page, let us know via the Accessibility Feedback Form .

- Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library

- 2300 Eye St., NW, Washington, DC 20037

- Phone: (202) 994-2850

- [email protected]

- https://himmelfarb.gwu.edu

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Nested case-control...

Nested case-control studies: advantages and disadvantages

- Related content

- Peer review

- Philip Sedgwick , reader in medical statistics and medical education 1

- 1 Centre for Medical and Healthcare Education, St George’s, University of London, London, UK

- p.sedgwick{at}sgul.ac.uk

Researchers investigated whether antipsychotic drugs were associated with venous thromboembolism. A population based nested case-control study design was used. Data were taken from the UK QResearch primary care database consisting of 7 267 673 patients. Cases were adult patients with a first ever record of venous thromboembolism between 1 January 1996 and 1 July 2007. For each case, up to four controls were identified, matched by age, calendar time, sex, and practice. Exposure to antipsychotic drugs was assessed on the basis of prescriptions on, or during the 24 months before, the index date. 1

There were 25 532 eligible cases (15 975 with deep vein thrombosis and 9557 with pulmonary embolism) and 89 491 matched controls. The primary outcome was the odds ratios for venous thromboembolism associated with antipsychotic drugs adjusted for comorbidity and concomitant drug exposure. When adjusted using logistic regression to control for potential confounding, prescription of antipsychotic drugs in the previous 24 months was significantly associated with an increased occurrence of venous thromboembolism compared with non-use (odds ratio 1.32, 95% confidence interval 1.23 to 1.42). The researchers concluded that prescription of antipsychotic drugs was associated with venous thromboembolism in a large primary care population.

Which of the following statements, if any, are true?

a) The nested case-control study is a retrospective design

b) The study design minimised selection bias compared with a case-control study

c) Recall bias was minimised compared with a case-control study

d) Causality could be inferred from the association between prescription of antipsychotic drugs and venous thromboembolism

Statements a , b , and c are true, whereas d is false.

The aim of the study was to investigate whether prescription of antipsychotic drugs was associated with venous thromboembolism. A nested case-control study design was used. The study design was an observational one that incorporated the concept of the traditional case-control study within an established cohort. This design overcomes some of the disadvantages associated with case-control studies, 2 while incorporating some of the advantages of cohort studies. 3 4

Data for the study above were extracted from the UK QResearch primary care database, a computerised register of anonymised longitudinal medical records for patients registered at more than 500 UK general practices. Patient data were recorded prospectively, the database having been updated regularly as patients visited their GP. Cases were all adult patients in the register with a first ever record of venous thromboembolism between 1 January 1996 and 1 July 2007. There were 25 532 cases in total. For each case, up to four controls were identified from the register, matched by age, calendar time, sex, and practice. In total, 89 491 matched controls were obtained. Data relating to prescriptions for antipsychotic drugs on, or during the 24 months before, the index date were extracted for the cases and controls. The index date was the date in the register when venous thromboembolism was recorded for the case. The cases and controls were compared to ascertain whether exposure to prescription of antipsychotic drugs was more common in one group than in the other. Despite the data for the cases and controls being collected prospectively, the nested case-control study is described as retrospective ( a is true) because it involved looking back at events that had already taken place and been recorded in the register.

Selection bias is of particular concern in the traditional case-control study. Described in a previous question, 5 selection bias is the systematic difference between the study participants and the population they are meant to represent with respect to their characteristics, including demographics and morbidity. Cases and controls are often selected through convenience sampling. Cases are typically recruited from hospitals or general practices because they are convenient and easily accessible to researchers. Controls are often recruited from the same hospital clinics or general practices as the cases. Therefore, the selected cases may not be representative of the population of all cases. Equally, the controls might not be representative of otherwise healthy members of the population. The above nested case-control study was population based, with the QResearch primary care database incorporating a large proportion of the UK population. The cases and controls were selected from the database and therefore should be more representative of the population than those in a traditional case-control study. Hence, selection bias was minimised by using the nested case-control study design ( b is true).

The traditional case-control study involves participants recalling information about past exposure to risk factors after identification as a case or control. The study design is prone to recall bias, as described in a previous question. 6 Recall bias is the systematic difference between cases and controls in the accuracy of information recalled. Recall bias will exist if participants have selective preconceptions about the association between the disease and past exposure to the risk factor(s). Cases may, for example, recall information more accurately than controls, possibly because of an association with the disease or outcome. Although in the study above the cases and controls were identified retrospectively, the data for the QResearch primary care database were collected prospectively. Therefore, there was no reason for any systematic differences between groups of study participants in the accuracy of the information collected. Therefore, recall bias was minimised compared with a traditional case-control study ( c is true).

Not all of the patient records in the UK QResearch primary care database were used to explore the association between prescription of antipsychotic drugs and development of venous thromboembolism. A nested case-control study was used instead, with cases and controls matched on age, calendar time, sex, and practice. This was because it was statistically more efficient to control for the effects of age, calendar time, sex, and practice by matching cases and controls on these variables at the design stage, rather than controlling for their potential confounding effects when the data were analysed. The matching variables were considered to be important factors that could potentially confound the association between prescription of antipsychotic drugs and venous thromboembolism, but they were not of interest as potential risk factors in themselves. Matching in case-control studies has been described in a previous question. 7

Unlike a traditional case-control study, the data in the example above were recorded prospectively. Therefore, it was possible to determine whether prescription of antipsychotic drugs preceded the occurrence of venous thromboembolism. Nonetheless, only association, and not causation, can be inferred from the results of the above nested case-control study ( d is false)—that is, those people who were exposed to prescribed antipsychotic drugs were more likely to have developed venous thromboembolism. This is because the observed association between prescribed antipsychotic drugs and occurrence of venous thromboembolism may have been due to confounding. In particular, it was not possible to measure and then control for, through statistical analysis, all factors that may have affected the occurrence of venous thromboembolism.

The example above is typical of a nested case-control study; the health records for a group of patients that have already been collected and stored in an electronic database are used to explore the association between one or more risk factors and a disease or condition. The management of such databases means it is possible for a variety of studies to be undertaken, each investigating the risk factors associated with different diseases or outcomes. Nested case-control studies are therefore relatively inexpensive to perform. However, the major disadvantage of nested case-control studies is that not all pertinent risk factors are likely to have been recorded. Furthermore, because many different healthcare professionals will be involved in patient care, risk factors and outcome(s) will probably not have been measured with the same accuracy and consistency throughout. It may also be problematic if the diagnosis of the disease or outcome changes with time.

Cite this as: BMJ 2014;348:g1532

Competing interests: None declared.

- ↵ Parker C, Coupland C, Hippisley-Cox J. Antipsychotic drugs and risk of venous thromboembolism: nested case-control study. BMJ 2010 ; 341 : c4245 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Sedgwick P. Case-control studies: advantages and disadvantages. BMJ 2014 ; 348 : f7707 . OpenUrl CrossRef

- ↵ Sedgwick P. Prospective cohort studies: advantages and disadvantages. BMJ 2013 ; 347 : f6726 . OpenUrl FREE Full Text

- ↵ Sedgwick P. Retrospective cohort studies: advantages and disadvantages. BMJ 2014 ; 348 : g1072 . OpenUrl FREE Full Text

- ↵ Sedgwick P. Selection bias versus allocation bias. BMJ 2013 ; 346 : f3345 . OpenUrl FREE Full Text

- ↵ Sedgwick P. What is recall bias? BMJ 2012 ; 344 : e3519 . OpenUrl FREE Full Text

- ↵ Sedgwick P. Why match in case-control studies? BMJ 2012 ; 344 : e691 . OpenUrl FREE Full Text

What Is A Case Control Study?

Julia Simkus

Editor at Simply Psychology

BA (Hons) Psychology, Princeton University

Julia Simkus is a graduate of Princeton University with a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology. She is currently studying for a Master's Degree in Counseling for Mental Health and Wellness in September 2023. Julia's research has been published in peer reviewed journals.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

A case-control study is a research method where two groups of people are compared – those with the condition (cases) and those without (controls). By looking at their past, researchers try to identify what factors might have contributed to the condition in the ‘case’ group.

Explanation

A case-control study looks at people who already have a certain condition (cases) and people who don’t (controls). By comparing these two groups, researchers try to figure out what might have caused the condition. They look into the past to find clues, like habits or experiences, that are different between the two groups.

The “cases” are the individuals with the disease or condition under study, and the “controls” are similar individuals without the disease or condition of interest.

The controls should have similar characteristics (i.e., age, sex, demographic, health status) to the cases to mitigate the effects of confounding variables .

Case-control studies identify any associations between an exposure and an outcome and help researchers form hypotheses about a particular population.

Researchers will first identify the two groups, and then look back in time to investigate which subjects in each group were exposed to the condition.

If the exposure is found more commonly in the cases than the controls, the researcher can hypothesize that the exposure may be linked to the outcome of interest.

Figure: Schematic diagram of case-control study design. Kenneth F. Schulz and David A. Grimes (2002) Case-control studies: research in reverse . The Lancet Volume 359, Issue 9304, 431 – 434

Quick, inexpensive, and simple

Because these studies use already existing data and do not require any follow-up with subjects, they tend to be quicker and cheaper than other types of research. Case-control studies also do not require large sample sizes.

Beneficial for studying rare diseases

Researchers in case-control studies start with a population of people known to have the target disease instead of following a population and waiting to see who develops it. This enables researchers to identify current cases and enroll a sufficient number of patients with a particular rare disease.

Useful for preliminary research

Case-control studies are beneficial for an initial investigation of a suspected risk factor for a condition. The information obtained from cross-sectional studies then enables researchers to conduct further data analyses to explore any relationships in more depth.

Limitations

Subject to recall bias.

Participants might be unable to remember when they were exposed or omit other details that are important for the study. In addition, those with the outcome are more likely to recall and report exposures more clearly than those without the outcome.

Difficulty finding a suitable control group

It is important that the case group and the control group have almost the same characteristics, such as age, gender, demographics, and health status.

Forming an accurate control group can be challenging, so sometimes researchers enroll multiple control groups to bolster the strength of the case-control study.

Do not demonstrate causation

Case-control studies may prove an association between exposures and outcomes, but they can not demonstrate causation.

A case-control study is an observational study where researchers analyzed two groups of people (cases and controls) to look at factors associated with particular diseases or outcomes.

Below are some examples of case-control studies:

- Investigating the impact of exposure to daylight on the health of office workers (Boubekri et al., 2014).

- Comparing serum vitamin D levels in individuals who experience migraine headaches with their matched controls (Togha et al., 2018).

- Analyzing correlations between parental smoking and childhood asthma (Strachan and Cook, 1998).

- Studying the relationship between elevated concentrations of homocysteine and an increased risk of vascular diseases (Ford et al., 2002).

- Assessing the magnitude of the association between Helicobacter pylori and the incidence of gastric cancer (Helicobacter and Cancer Collaborative Group, 2001).

- Evaluating the association between breast cancer risk and saturated fat intake in postmenopausal women (Howe et al., 1990).

Frequently asked questions

1. what’s the difference between a case-control study and a cross-sectional study.

Case-control studies are different from cross-sectional studies in that case-control studies compare groups retrospectively while cross-sectional studies analyze information about a population at a specific point in time.

In cross-sectional studies , researchers are simply examining a group of participants and depicting what already exists in the population.

2. What’s the difference between a case-control study and a longitudinal study?

Case-control studies compare groups retrospectively, while longitudinal studies can compare groups either retrospectively or prospectively.

In a longitudinal study , researchers monitor a population over an extended period of time, and they can be used to study developmental shifts and understand how certain things change as we age.

In addition, case-control studies look at a single subject or a single case, whereas longitudinal studies can be conducted on a large group of subjects.

3. What’s the difference between a case-control study and a retrospective cohort study?

Case-control studies are retrospective as researchers begin with an outcome and trace backward to investigate exposure; however, they differ from retrospective cohort studies.

In a retrospective cohort study , researchers examine a group before any of the subjects have developed the disease, then examine any factors that differed between the individuals who developed the condition and those who did not.

Thus, the outcome is measured after exposure in retrospective cohort studies, whereas the outcome is measured before the exposure in case-control studies.

Boubekri, M., Cheung, I., Reid, K., Wang, C., & Zee, P. (2014). Impact of windows and daylight exposure on overall health and sleep quality of office workers: a case-control pilot study. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine: JCSM: Official Publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 10 (6), 603-611.

Ford, E. S., Smith, S. J., Stroup, D. F., Steinberg, K. K., Mueller, P. W., & Thacker, S. B. (2002). Homocyst (e) ine and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review of the evidence with special emphasis on case-control studies and nested case-control studies. International journal of epidemiology, 31 (1), 59-70.

Helicobacter and Cancer Collaborative Group. (2001). Gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori: a combined analysis of 12 case control studies nested within prospective cohorts. Gut, 49 (3), 347-353.

Howe, G. R., Hirohata, T., Hislop, T. G., Iscovich, J. M., Yuan, J. M., Katsouyanni, K., … & Shunzhang, Y. (1990). Dietary factors and risk of breast cancer: combined analysis of 12 case—control studies. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 82 (7), 561-569.

Lewallen, S., & Courtright, P. (1998). Epidemiology in practice: case-control studies. Community eye health, 11 (28), 57–58.

Strachan, D. P., & Cook, D. G. (1998). Parental smoking and childhood asthma: longitudinal and case-control studies. Thorax, 53 (3), 204-212.

Tenny, S., Kerndt, C. C., & Hoffman, M. R. (2021). Case Control Studies. In StatPearls . StatPearls Publishing.

Togha, M., Razeghi Jahromi, S., Ghorbani, Z., Martami, F., & Seifishahpar, M. (2018). Serum Vitamin D Status in a Group of Migraine Patients Compared With Healthy Controls: A Case-Control Study. Headache, 58 (10), 1530-1540.

Further Information

- Schulz, K. F., & Grimes, D. A. (2002). Case-control studies: research in reverse. The Lancet, 359(9304), 431-434.

- What is a case-control study?

Related Articles

Research Methodology

Qualitative Data Coding

What Is a Focus Group?

Cross-Cultural Research Methodology In Psychology

What Is Internal Validity In Research?

Research Methodology , Statistics

What Is Face Validity In Research? Importance & How To Measure

Criterion Validity: Definition & Examples

EP717 Module 5 - Epidemiologic Study Designs – Part 2:

Case-control studies.

- Page:

- 1

- | 2

- | 3

- | 4

- | 5

- | 6

- | 7

When is it Desirable to Conduct a Case-Control Study?

Advantages and disadvantages of case-control studies.

Case-control studies provide a method that avoids many of the limitations of cohort studies. Case-control studies are advantageous under the following circumstances:

- When exposure data are expensive or difficult to obtain, e.g., assessing pesticide levels in blood or other medical tests

- When the disease has a long induction and/or latent period, e.g., cancer, dementia. With a case-control study one does not have to wait for disease to occur,

- When the outcome (disease) is rare. (A cohort study would require too large a sample size, e.g., when studying rare parasitic diseases.)

- When the study population is dynamic and it is difficult to maintain follow up, e.g., a homeless population

- When little is known about a disease, case-control studie can evaluate multiple exposures, e.g., in the early studies of AIDS.

return to top | previous page | next page

Content ©2021. All Rights Reserved. Date last modified: April 21, 2021. Wayne W. LaMorte, MD, PhD, MPH

- Open access

- Published: 04 May 2024

Impacts of heat exposure in utero on long-term health and social outcomes: a systematic review

- Nicholas Brink 1 ,

- Darshnika P. Lakhoo 1 ,

- Ijeoma Solarin 1 ,

- Gloria Maimela 1 ,

- Peter von Dadelszen 2 ,

- Shane Norris 3 ,

- Matthew F. Chersich 1 &

Climate and Heat-Health Study Group

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth volume 24 , Article number: 344 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

512 Accesses

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

Climate change, particularly global warming, is amongst the greatest threats to human health. While short-term effects of heat exposure in pregnancy, such as preterm birth, are well documented, long-term effects have received less attention. This review aims to systematically assess evidence on the long-term impacts on the foetus of heat exposure in utero.

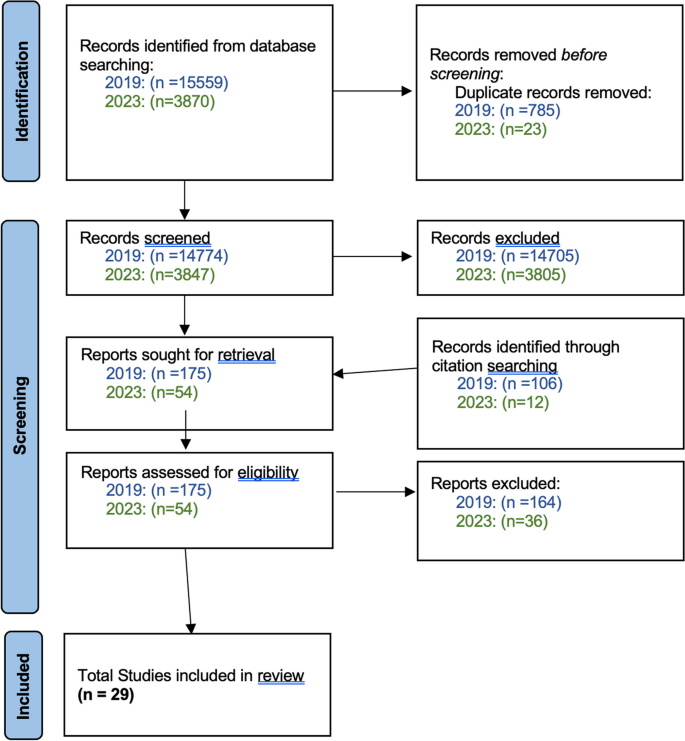

A search was conducted in August 2019 and updated in April 2023 in MEDLINE(PubMed). We included studies on the relationship of environmental heat exposure during pregnancy and any long-term outcomes. Risk of bias was assessed using tools developed by the Joanna-Briggs Institute, and the evidence was appraised using the GRADE approach. Synthesis without Meta-Analysis (SWiM) guidelines were used.

Eighteen thousand six hundred twenty one records were screened, with 29 studies included across six outcome groups. Studies were mostly conducted in high-income countries ( n = 16/25), in cooler climates. All studies were observational, with 17 cohort, 5 case-control and 8 cross-sectional studies. The timeline of the data is from 1913 to 2019, and individuals ranged in age from neonates to adults, and the elderly. Increasing heat exposure during pregnancy was associated with decreased earnings and lower educational attainment ( n = 4/6), as well as worsened cardiovascular ( n = 3/6), respiratory ( n = 3/3), psychiatric ( n = 7/12) and anthropometric ( n = 2/2) outcomes, possibly culminating in increased overall mortality ( n = 2/3). The effect on female infants was greater than on males in 8 of 9 studies differentiating by sex. The quality of evidence was low in respiratory and longevity outcome groups to very low in all others.

Conclusions

Increasing heat exposure was associated with a multitude of detrimental outcomes across diverse body systems. The biological pathways involved are yet to be elucidated, but could include epigenetic and developmental perturbations, through interactions with the placenta and inflammation. This highlights the need for further research into the long-term effects of heat exposure, biological pathways, and possible adaptation strategies in studies, particularly in neglected regions. Heat exposure in-utero has the potential to compound existing health and social inequalities. Poor study design of the included studies constrains the conclusions of this review, with heterogenous exposure measures and outcomes rendering comparisons across contexts/studies difficult.

Trial Registration

PROSPERO CRD 42019140136.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Climate change is one of the most significant threats to human health [ 1 ], characterized by an increase in global temperatures amongst other environmental changes. Global temperatures have increased by approximately 1·2 °C, and are projected to increase beyond a critical threshold of 1·5 °C in the next 5–10 years [ 2 ]. Increasingly, heat exposure is being linked with a multitude of short- and long-term health effects in vulnerable populations, including children [ 3 ], the elderly, and pregnant women [ 4 ]. The effect on pregnant women extends to the health of the foetus, with significant detrimental effects associated with heat exposure including preterm birth, stillbirth, and decreased birth weight [ 5 ]. Impacts of heat exposure are increasingly important in populations in resource-constrained settings, where heat adaptation measures such as active (air-conditioning) and passive cooling (water, green and blue spaces) are limited, and often inaccessible [ 6 ]. These populations are often found in some of the hottest climates and in areas whose contribution to global warming is negligible, thus compounding inequities [ 7 ]. In addition, research in this field is biased towards Europe, North America and Asia and is profoundly underrepresented in Africa and South America [ 8 ]. Understanding the scope and distribution of research conducted is key to guiding future research, including biological studies to explore possible mechanisms, and interventional studies to alleviate any observed negative effects. Multiple previous systematic reviews have explored the short-term impacts of heat on the foetus [ 3 , 5 , 9 ] but only one has explored the long-term impacts of heat exposure on mental health [ 10 ]. The in-utero environment has long been considered important in the long-term health and wellbeing of individuals [ 11 , 12 ], although it has been challenging to delineate specific causal pathways. This study aims to systematically review the literature on the long-term effects of heat exposure in-utero on the foetus, and explore possible casual pathways.

Materials and methods

This review forms part of a larger systematic mapping survey of the effect of heat exposure, and adaptation interventions on health (PROSPERO CRD 42019140136) [ 13 ]. The initial literature search was conducted in September 2018, where the authors searched MEDLINE (PubMed), Science Citation Index Expanded, Social Sciences Citation Index, and Arts and Humanities Citation Index using a validated search strategy (Supplementary Text 1 ). This search was updated in April 2023 through a MEDLINE search, as all previous articles were located in this database. Screening of titles and abstracts was done independently in duplicate, with any differences reconciled by MFC, with subsequent updates conducted by NB and DL. The authors only included studies on humans, published in Chinese, English, German, or Italian. Studies on heat exposure from artificial and endogenous sources were excluded, and only exogenous, weather-related heat exposure during pregnancy was included. All study designs were eligible except modelling studies and systematic reviews. No date restrictions were applied. EPPI-Reviewer software [ 14 ] provided a platform for screening, reviewing of full text articles, and for data extraction. No additional information was requested or provided by the authors. Long-term effects were defined as any outcomes that were not apparent at birth.

Articles meeting the eligibility criteria were extracted in duplicate after the initial search and then by a single reviewer in the subsequent update (NB/DL). Data were extracted to include characteristics outlined in Supplementary file 1 .

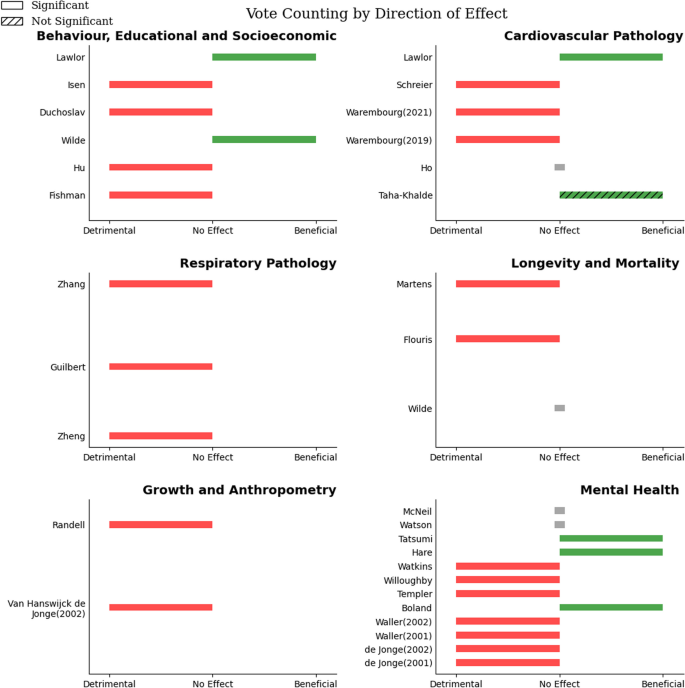

This systematic review was conducted according to the Systematic Review without Meta-Analysis (SWiM) guidelines, broadly based on PRISMA [ 15 ], as the outcomes, statistical techniques, and heat exposure measurements were heterogenous, rendering a meta-analysis untenable. Outcomes were grouped clinically, reviewed for the magnitude and direction of effect, and their statistical significance, and included negative or null findings when reported on. A text-based summary of these findings was made. ‘Vote-counting’ was utilized to summarise direction of effect findings. Analysis was conducted on the geographical areas, climate zones [ 16 ], mean annual temperature and socioeconomic classification of the country where the studies were conducted. Furthermore, an attempt was made to identify at-risk population sub-groups.

The principal investigator assessed each study for a risk of bias using the tools developed by the Joanna-Briggs Institute (JBI) [ 17 ] (Supplementary file 1 ). Each study was classified as high or low risk of bias. Studies that did not score ‘yes’ on two or more applicable parameters were classified as high risk of bias [ 5 ]. Due to the limited research in this field, no studies were excluded based on risk of bias. The certainty of the evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach, with the body of evidence assessed on a scale of certainty: very low, low, moderate and high [ 18 ]. Due to the heterogeneity of outcomes, and the reporting thereof, assessment of publication bias was not possible.

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or writing of the report.

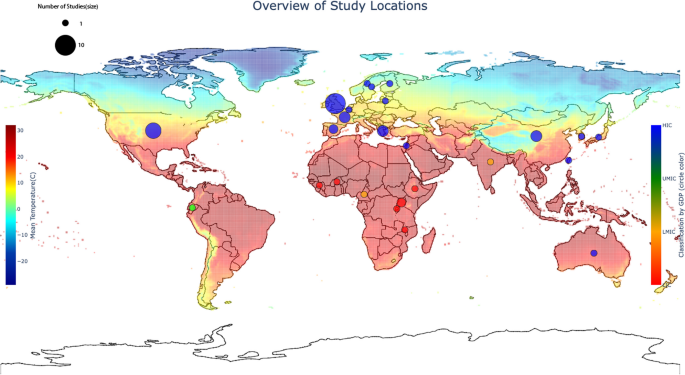

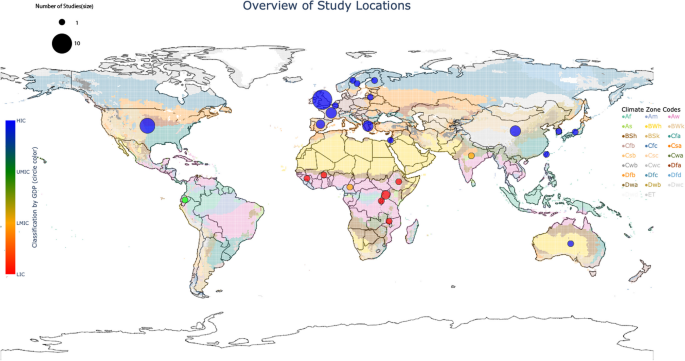

The updated search identified 18 621 non-duplicate records, and after screening 229 full-text articles were reviewed for inclusion, with a total of 29 studies included in the final analysis (Fig. 1 : flow chart). The included studies were conducted in 25 countries across six continents, including six Low-Income Countries (LIC), two Lower-Middle Income Countries (LMIC), one Upper-Middle Income Country (UMIC) and 16 High Income Countries (HIC) [ 19 ]. They included 25 Köppen-Geiger climate zones [ 16 ], and mean annual temperatures ranging from 2.1 °C in Norway to 30.0 °C in Burkina Faso [ 20 ] (Figs. 2 and 3 ). All studies were observational, with 17 cohort, five case-control and eight cross-sectional studies. The timeline of the data is from 1913 to 2019, and individuals included ranged in age from neonates to adults, and the elderly. The studies were grouped by outcomes as follows: behavioural, educational and socioeconomic ( n = 6), cardiovascular disease ( n = 6), respiratory disease ( n = 3), growth and anthropometry ( n = 2), mental health ( n = 12) and longevity and mortality ( n = 3). The measures of heat exposure were variable, with minimum, mean, maximum, and apparent temperature being utilized, as well as temperature variability, heat wave days and discreet shocks (number of times exposure exceeded a specific threshold). The majority of studies measured heat using mean temperature ( n = 27/29). In addition, the statistical comparison was diverse, with some studies making a continuous linear comparison by degree Celsius, while others compared heat exposure by quartiles, amongst other categorical comparisons. Furthermore, heat exposure by any definition was not reported over the same timeframes, with some studies including variable periods before birth, during pregnancy and at birth in their analysis. Levels of temporal resolution of heat exposure were also diverse, ranging from monthly effects to effects observed over the entire gestational period, or year of birth. In addition, differing use of heat adaptation mechanisms was not uniformly described and adjusted for. Various confounders were adjusted for, and although not uniform, these were generally inadequate. The effect on female infants was greater than on male infants in eight of nine studies differentiating by sex, with increased effects on marginalised groups (African-Americans) in one further study. Overall, the quality of the evidence, as assessed by the GRADE approach, was low in respiratory and longevity outcome groups to very low in all other groups, primarily as a result of their observational nature and high risk of bias, due to insufficient consideration of confounders, and inadequate measures of heat exposure.

PRISMA flow diagram

Map showing countries where studies were conducted relative to mean annual temperature [ 21 ]

Map showing countries where studies were conducted relative to climate zones [ 16 ]

A total of six studies reported on behaviour, educational and socioeconomic outcomes, which were detrimentally affected by increases in heat exposure (Fig. 4 ; Table 1 ), although the quality of the evidence was very low . End-points were not uniform, but included earnings, completion of secondary school or higher education, number of years of schooling, and gamified cooperation-rates in a public-goods game (where test scores represent achieving maximal public benefit in hypothetical situations).

Two large studies reported a detrimental effect of heat exposure on adult income, with the greatest effect noted in first trimester exposure. These studies noted a reduction in earnings of up to 1·2% per 1 °C increase in temperature, with greater effects in females [ 22 ], and a decrease of $55.735 (standard error(SE): 15·425, P < 0·01) annual earnings at 29–31 years old, per day exposure > 32 °C [ 26 ]. Two studies reported worse educational outcomes, with the greatest effect noted in the second trimester [ 23 ]. Rates of completing secondary education were found to be reduced by 0·2% per 1 °C increase in temperature ( P = 0·05) [ 22 ], illiteracy was increased by 0·18% (SE=(0·0009); P < 0·05) and mean years of schooling was lowered by 0.02 (SE=(0·009) P = 0·07) [ 23 ]. Two studies reported a beneficial effect of heat exposure on educational outcomes, although both studies suffered from significant methodological flaws, and effects were < 0·01% when effect estimates were noted [ 24 , 27 ]. One small study reported lower cooperation rates by 20% ( P < 0·01) in a public-goods game, with lower predicted public wellbeing [ 25 ].

The studies generally exhibited a dose-response effect with evidence for a critical threshold of effect of 28 °C in one study [ 22 ]. All studies were at a high risk of bias.

Figure showing vote counting across all outcome groups. No Effect = No direction of effect noted in study

Six studies reported on cardiovascular pathology and risk factors thereof, which were detrimentally affected by increased exposure to heat (Fig. 4 ; Table 2 ), although measures and surrogates of this outcome were heterogenous. The quality of the evidence was very low, and the sample sizes were small. Outcomes included blood pressure, a composite cardiovascular disease indicator, and specific cardiovascular disease risk factors such as diabetes mellitus (type I), insulin resistance, waste circumference, and triglyceride levels.

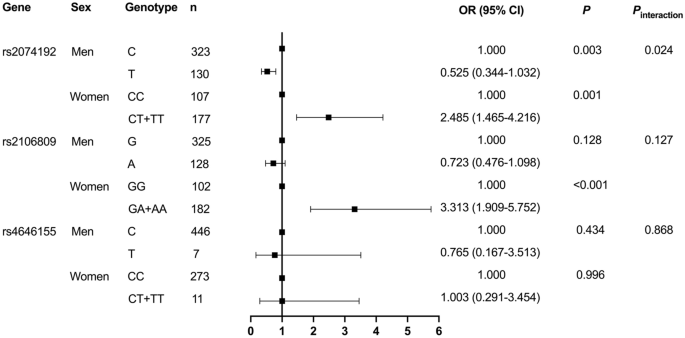

Three studies found a detrimental effect of heat exposure on hypertension rates, and increased blood pressure [ 31 ], with a maximum of 1·6 mm Hg increase noted per interquartile range (IQR) increase (95% Confidence interval (CI) = 0·2, 2·9, P = 0·024) in children [ 30 ], with increased effects on women in the largest study ( N = 11,237) [ 32 ]. Another study found increasing heat exposure at conception was detrimentally associated with an increase in coronary heart disease ( P = 0·08) [ 32 ], although one of the smaller studies ( N = 4286) found a beneficial effect of heat exposure at birth on diverse cardiovascular outcomes, including coronary heart disease ( P = 0·03 for trend), triglyceride levels ( P = 0·06 for trend) and insulin resistance ( P = 0·04 for trend) [ 27 ]. One study found lower odds of type I diabetes mellitus with increasing heat exposure, with odds ratio (OR) = 0·73 (95%CI = 0·48, 1·09, P -value not stated) [ 28 ]. Another study did not detect statistically significant relationships between heat exposure and hypertension or a composite cardiovascular disease indicator, but did not provide effect estimates [ 29 ]. Five studies were at a high risk of bias [ 27 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 ], with only one case-control study at a low risk of bias [ 28 ].

Respiratory pathology was reported by three studies, assessing different outcomes. Outcomes were detrimentally associated with increasing heat (Fig. 4 ; Table 3 ), however the quality of the evidence was low . The outcomes were primarily measured in infants and children, with no studies on adult outcomes. The largest study ( N = 1681) found that increasing heat exposure increased the odds of having childhood asthma [ 33 ], and another small study ( N = 343) noted worsened lung function with increasing heat exposure [ 34 ].

An additional study noted increased odds of childhood pneumonia with increasing diurnal temperature variation (DTV) in pregnancy, with a maximum OR = 1·85 (95%CI = 1·24, 2·76) in the third trimester [ 35 ].

Exposure in the third trimester had the greatest effect across all three studies [ 33 , 34 , 35 ]. Females showed an increased susceptibility to heat exposure’s effects on lung function, but males were more susceptible to heat’s effect on childhood pneumonia. There was a critical threshold noted in the asthma study of 24·6 °C, with a dose-response effect. The asthma study was assessed as low risk of bias, however the other studies were at high risk.

Growth and anthropometry was reported on by two studies, with differing outcomes, although in both, heat exposure was associated with detrimental, although heterogenous, outcomes (Fig. 4 ; Table 4 ). The overall quality of the evidence was very low . One study found a positive association with heat exposure and increased body mass index (BMI), r = 0·22 ( P < 0·05) in the third trimester with greater effects noted in females and in African-Americans [ 36 ]. Another large study ( N = 23 026) found increased odds of stunting (OR = 1·28, 95%CI = not stated, p < 0·001) with a negative correlation with height noted ( r =-0·083 P < 0·01) [ 37 ]. Effects were greatest in the first and third trimester. Both studies were at a high risk of bias.

Mental health was reported on by 12 studies. Increasing heat exposure generally had a detrimental association with mental health outcomes (Fig. 4 ; Table 5 ), although these were heterogenous. The overall quality of the evidence was very low . Five studies reported on schizophrenia rates, with only one study showing a strongly positive association of heat exposure at conception with schizophrenia rates ( r = 0·50, p < 0·025) [ 38 ]. Another study noted the same effect with increasing heat in the summer before birth, however this was not statistically significant [ 39 ]. The third study reported no association of this outcome [ 40 ], with another small study ( N = 2985) showing a negative correlation with temperatures at birth, without reporting on heat exposure during other periods of gestation [ 41 ]. The fifth study failed to report direction of effect, but noted non-significant findings [ 42 ]. Six studies reported on eating disorders, with all six showing a detrimental effect with increasing heat exposure. Of the three studies on clinical anorexia nervosa, one reported increasing rates of anorexia nervosa compared to other eating disorders (χ²= 4·48, P = 0·017) [ 43 ], another reported increasing rates of a restrictive-subtype (χ²= 3·18, P = 0·04) as well as reporting worse assessments of restrictive behaviours [ 44 ], which was supported by a third study in a different setting [ 45 ]. Three studies examined non-clinical settings, with some inconsistent effects. The first study showed a weak positive association with heat exposure, and drive for thinness (Spearman’s ⍴ = 0·46, P < 0·05) and bulimia scores (Spearman’s ⍴ = 0·25, P < 0·05) [ 46 ], which was supported by a replication study [ 47 ], and one other study [ 48 ]. The most significant and consistent effects noted in the third trimester, at birth, and in females [ 47 , 48 ]. One study reported a beneficial effect of increased temperatures in the first trimester on rates of depression, however no other directions of effect were noted for other periods of exposure [ 49 ]. These studies were at a high risk of bias.

Increasing heat exposure had a detrimental effect on longevity and mortality across various outcomes (Fig. 4 ; Table 6 ), although despite large sample sizes, the quality of the evidence was low . One study found a negative correlation of heat exposure with longevity ( r =-0·667, P < 0·001), with a greater effect on females [ 50 ]. A second study showed a detrimental effect on telomere length, as a predicter of longevity, with the greatest effect towards the end of gestation (3·29% shorter TL, 95%CI = − 4·67, − 1·88, per 1 C increase above 95th centile) [ 51 ]. Conversely, a third study noted no correlation with mortality [ 24 ]. All but the study on telomere length [ 51 ] were at a high risk of bias.

This study establishes significant patterns of effects amongst the outcomes reviewed, with increasing heat exposure being associated with an overall detrimental effect on multiple, diverse, long-term outcomes. These effects are likely to increase with rising temperatures, however modelling this is beyond the scope of this review.

The most notable detrimental outcomes are related to neurodevelopmental pathways, with behavioural, educational, socioeconomic and mental health outcomes consistently associated with increasing heat exposure, in addition to having the greatest body of literature to support this. Importantly, other systems such as the respiratory and cardiovascular systems also suggest harmful effects of heat exposure, culminating in detrimental associations with longevity and mortality. Some studies illustrated a possible beneficial effect in some disease-processes, such as coronary heart disease and depression showing the potential for shifting disease profiles with rising temperatures.

The detrimental effects of heat exposure became more significant with increasing temperatures, with many studies describing increasing effects beyond critical thresholds which, although varied across studies, suggest that there is a limit of heat adaption strategies, both biological and behavioural [ 52 , 53 ].

In addition, the effect of increasing heat exposure was associated with worse outcomes in already marginalised communities, such as women [ 22 , 32 , 34 , 36 , 44 , 47 , 48 , 50 ] and certain ethnic groups (African-Americans) [ 46 ]. The reasons for sub-population vulnerabilities are unclear and likely complex. In the case of female foetuses being more susceptible to changes in the in-utero environment, it is possible that there is a ‘survivorship bias’. This would occur if women with harmful exposure lose male infants during pregnancy at a higher rate, and thus the surviving female infants appear more at risk. However, despite an increased risk of early pregnancy loss, there are no studies that have assessed this differential vulnerability. This still has the effect of potentially increasing the burden of disease on an already marginalised group.

In the case of certain population groups being more at risk, it is likely that both physiological differences in vulnerability as well as socio-economic effect-modifiers exist to explain these differences, however, the included literature lacks sufficient evidence to assess this. The vulnerabilities of different populations to the long-term effects of heat exposure in-utero likely contributes to the unequal impacts of climate change that have already been established [ 54 ], and will be an important contributor to inequality with future increases in temperature. Further research in this area is critical to inform targeted redistributive interventions.

Although the associations may be clear, establishing causality is fraught with difficulty, with no consensus on an infallible approach [ 55 , 56 , 57 ]. However, it is prudent to highlight supporting evidence in this review.

The hypothesis that the in-utero environment had significant long-term impacts on the foetus was first suggested by Barker, in the context of maternal nutrition and cardiovascular disease [ 11 ]. Further studies supported this hypothesis, and expanded on the effects the in-utero environment has on the foetus and its long-term wellbeing [ 58 ]. Long-term heat exposure may also be associated with changes in nutritional availability [ 11 ], and is likely one of many complex but important environmental exposures in-utero.

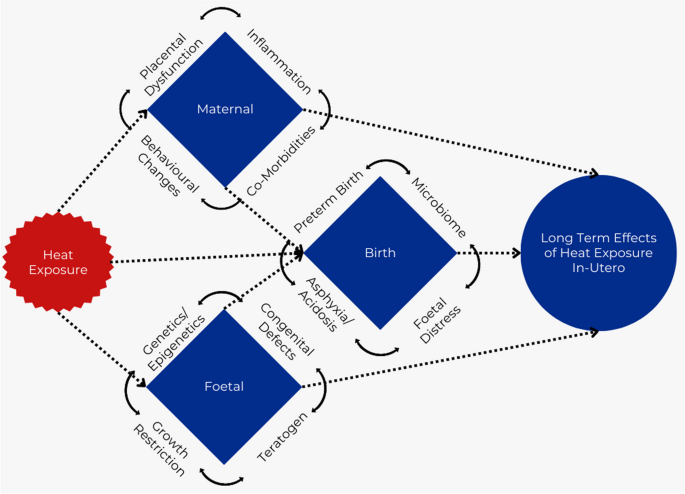

Maternal comorbidities, associated with increasing heat exposure such as hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and gestational diabetes mellitus, are known to negatively affect the foetus in the long-term [ 59 , 60 ]. These comorbidities may be part of the long-term pathogenicity of heat exposure, through short-term exposure-outcome pathways. Placental dysfunction is central to the pathology of pre-eclampsia, and is a significant cause for foetal pathology [ 61 , 62 ]. The placenta is not auto-regulated and is therefore acutely affected by changes to blood volume, heart rate and blood pressure, culminating in cardiac output as it is delivered to the placenta as an end-organ with resultant negative effects on the foetus [ 63 ]. Heat-acclimatisation mechanisms are hypothesized to affect this delicate balance [ 52 , 64 ], with observational studies supporting this [ 64 ]. It has been suggested that heat exposure’s increase in inflammation is a possible causative mechanism for pre-term birth [ 5 , 52 ], but inflammation has numerous additional effects on the immune system and could prove an insult to the mother and developing foetus [ 62 , 65 ]. These effects may only manifest in the long-term.

Heat was one of the earliest described teratogens [ 66 ], with significant effects on neurodevelopment noted in animal models in keeping with the observed associations of this review [ 67 ]. Biological organisms are extremely dependent on heat as a trigger for various processes. Plants and animals undergo significant change in response to the seasons, which are often guided by fluctuations in temperature. These changes are often mediated by epigenetic mechanisms, allowing the modification and modulation of gene expression [ 68 , 69 ].

Thus, from an evolutionary perspective, DNA, is sensitive to changes in temperature. The mechanism of this sensitivity has been shown to be primarily epigenetic in nature [ 69 ]. Increasing heat results in modifications to histone deacetylation and DNA methylation [ 69 ]. This is required to provide fast-acting adaptions to acute stressors, but can have long-term effects too [ 70 ]. Thus, it is likely that humans are sensitive to changes in temperature, which can alter epigenetic modifications, and thus our exposome. This sensitivity, may have provided a survival benefit in times of increasing heat, or it may simply be a vestigial function which provides no survival benefit, and may in fact have detrimental effects [ 71 ]. Epigenetic changes have been shown to have significant effects on metabolic diseases and risk profiles, and an in-depth review is provided by Wu et al. [ 72 ]. The exact processes and genes involved would be an area requiring further research, where similar research exists on the effects of nutrition on exact epigenetic pathways [ 73 ]. An important pattern requiring further research involves the effect heat may have on neurodevelopment [ 67 , 74 ]. The above pathways provide additional mechanisms for the long-term lag between exposure-outcome pathways. In addition, acute heat exposure at the time of birth has been associated with various possibly pathogenic mechanisms such as preterm birth [ 5 ], low APGAR scores [ 75 ] and foetal distress [ 76 ], as well as a possible effect on the maternal microbiome and the seeding thereof to the neonate [ 10 , 64 , 77 , 78 ]. These effects, can all provide plausible causes for the long-term outcomes observed through short-term insults. The interplay of these, and additional factors is highlighted in Fig. 5 [ 79 ]. Importantly, the periods of vulnerability are likely different for these various pathways, but specific outcomes may have multiple periods of vulnerability through different pathways.

Causal pathways

The outcomes associated with increasing heat exposure highlight the health, social, and economic cost of global warming, establishing current estimates and future predictions for this are beyond the scope of this research but would provide a valuable area for future research. This would entail estimating disease-burden due to climate change through attribution studies. Traditional health impact studies conflate adverse outcomes from natural variations in climate (‘noise’) with adverse outcomes from anthropogenic climate change. However, not every climate-related adverse outcome is the result of anthropogenic climate change, and these effects are likely different in vulnerable populations. This highlights the benefit of studying and implementing effective heat adaptation strategies in areas where the greatest effect is likely to be observed, and where the greatest impacts in lessening the economic and human impact of global warming are possible [ 80 , 81 ].

Limitations

The difficulty in assessing the data is compounded by the heterogenous measures of heat exposure. No studies used widely accepted heat exposure indices that consider important environmental modifying factors like humidity and windspeed [ 82 , 83 ]. In addition, effect modifiers, heat acclimatisation and adaptation strategies were seldom considered [ 84 , 85 , 86 ]. It may be prudent for future studies to consider the measure of ionizing radiation exposure as an analogous environmental exposure, where different measures exist for the intensity, total quantity (a function of duration of exposure) and biologically-adjusted quantity absorbed [ 87 ]. Differing time-periods of exposure made it difficult to evaluate specific periods of sensitivity, which are likely different for various outcomes, depending on critical periods of development.

Despite consistency across different contexts in this review, the analysis of the distribution of the included studies highlights the unequal weight of studies towards relatively cooler climates, in regions with higher socioeconomic levels and likely greater heat adaptation uptake, and must therefore be interpreted in this context. It is possible that myriad factors that differ geographically, including physiological and socio-economic differences, will influence the effects of heat, and thus there is likely no underlying universal truth to associations and effect estimates.

Quantifying, describing and comparing the effect size across studies was rendered more difficult due to heterogenous statistical analyses.

Although some studies adjusted for possible confounding variables, not all reported on this, with the effects of seasonal, foetal, and maternal biological factors that may not lie on the causal pathway seldom considered [ 3 , 5 , 9 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 ].

Data extraction and assessment of risk of bias was not uniformly undertaken in duplicate due to resource constraints, which may predispose to extraction errors or bias. The high risk of bias of included studies, limits the utility of the overall assessment of effects and suggestions for further action. In addition, publication bias is likely skewing the results towards statistically significant detrimental results, with studies with smaller sample sizes not necessarily showing wider distribution of findings as would be expected.

Climate change, and in particular, global warming, is a significant emerging global public health threat, with far reaching, and disproportionate effects on the most vulnerable populations. The effects of increasing heat exposure in utero are associated with, and possibly causal in, wide-ranging long-term impacts on socioeconomic and health outcomes with a significant cost associated with increasing global temperatures. This association is as a result of a complex interplay of factors, including through direct and indirect effects on the mother and foetus. Further research is urgently required to elicit biological pathways, and targets for intervention as well as predicting future disease-burden and economic impacts through attribution studies.

Availability of data and materials

This study was a review of publicly available information data, with references to data sources made in the reference list.

Abbreviations

Apparent Temperature

Body Mass Index

Blood Pressure

Coronary Heart Disease

Confidence Interval

Diastolic Blood Pressure

Eating Disorder Inventory

Functional Residual Capacity

Interquartile Range

Non-Significant

Respiratory Rate

Systolic Blood Pressure

Standard Error

Telomere Length

World Health Organisation

Atwoli L, A HB, Benfield T, et al. Call for emergency action to limit global temperature increases, restore biodiversity and protect health. BMJ Lead. 2022;6(1):1–3.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Organization WM, World Meteorological O. WMO global annual to decadal climate update (Target years: 2023–2027). Geneva: WMO; 2023. p. 24.

Book Google Scholar

Lakhoo DP, Blake HA, Chersich MF, Nakstad B, Kovats S. The effect of high and low ambient temperature on infant health: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(15):9109.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Cissé G, McLeman R, Adams H, et al. Health, wellbeing and the changing structure of communities. In: Pörtner HO, Roberts DC, Tignor MMB, Poloczanska ES, Mintenbeck K, Alegría A, et al. editors. Climate change 2022: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability contribution of working group II to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2022.

Chersich MF, Pham MD, Areal A, et al. Associations between high temperatures in pregnancy and risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and stillbirths: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;371:m3811.

Birkmann J, Liwenga E, Pandey R, et al. Poverty, livelihoods and sustainable development. In: Pörtner HO, Roberts DC, Tignor MMB, Poloczanska ES, Mintenbeck K, Alegría A, et al. editors. Climate change 2022: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability contribution of working group II to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2022.

Watts N, Amann M, Ayeb-Karlsson S, et al. The Lancet countdown on health and climate change: from 25 years of inaction to a global transformation for public health. Lancet. 2018;391(10120):581–630.

Campbell-Lendrum D, Manga L, Bagayoko M, Sommerfeld J. Climate change and vector-borne diseases: what are the implications for public health research and policy? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2015;370(1665):20130552.

Haghighi MM, Wright CY, Ayer J, et al. Impacts of high environmental temperatures on congenital anomalies: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(9):4910.

Puthota J, Alatorre A, Walsh S, Clemente JC, Malaspina D, Spicer J. Prenatal ambient temperature and risk for schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2022;247:67–83.

Barker DJ. Intrauterine programming of coronary heart disease and stroke. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 1997;423:178–82; discussion 83.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Hales CN, Barker DJ. The thrifty phenotype hypothesis. Br Med Bull. 2001;60:5–20.

Manyuchi A, Dhana A, Areal A, et al. Title: systematic review to quantify the impacts of heat on health, and to assess the effectiveness of interventions to reduce these impacts. PROSPERO: International prospective register of systematic reviews. 2019, 42019140136. Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPEROFILES/118113_PROTOCOL_20181129.pdf .

Thomas J, Brunton J, Graziosi S. EPPI-Reviewer 4.0: software for research synthesis. EPPI Centre Software. London: Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London; 2010.

Campbell M, McKenzie JE, Sowden A, et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. BMJ. 2020;368:l6890.

Beck HE, Zimmermann NE, McVicar TR, Vergopolan N, Berg A, Wood EF. Present and future Köppen-Geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution. Sci Data. 2018;5(1):180214.

Barker TH, Stone JC, Sears K, et al. Revising the JBI quantitative critical appraisal tools to improve their applicability: an overview of methods and the development process. JBI Evid Synth. 2023;21(3):478.

Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.4 (updated August 2023). Cochrane, 2023. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook .

World Bank Country and Lending Groups – World Bank Data Help Desk. Retrieved: June 01 2023. Available from: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups-files/112/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups.html .

Home | Climate change knowledge portal. Retrieved: June 01 2023. Available from: https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/files/26/climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org.html .

Harris I, Osborn TJ, Jones P, Lister D. Version 4 of the CRU TS monthly high-resolution gridded multivariate climate dataset. Sci Data. 2020;7(1):109.

Fishman R, Carrillo P, Russ J. Long-term impacts of exposure to high temperatures on human capital and economic productivity. J Environ Econ Manag. 2019;93:221–38.

Article Google Scholar

Hu Z, Li T. Too hot to handle: the effects of high temperatures during pregnancy on adult welfare outcomes. J Environ Econ Manag. 2019;94:236–53.

Wilde J, Apouey BH, Jung T. The effect of ambient temperature shocks during conception and early pregnancy on later life outcomes. Eur Econ Rev. 2017;97:87–107.

Duchoslav J. Prenatal temperature shocks reduce cooperation: evidence from public goods games in Uganda. Front Behav Neurosci. 2017;11: 249.

Isen A, Rossin-Slater M, Walker R. Relationship between season of birth, temperature exposure, and later life wellbeing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(51):13447–52.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar