ChatGPT for Teachers

Trauma-informed practices in schools, teacher well-being, cultivating diversity, equity, & inclusion, integrating technology in the classroom, social-emotional development, covid-19 resources, invest in resilience: summer toolkit, civics & resilience, all toolkits, degree programs, trauma-informed professional development, teacher licensure & certification, how to become - career information, classroom management, instructional design, lifestyle & self-care, online higher ed teaching, current events, inclusive education: what it means, proven strategies, and a case study.

Considering the potential of inclusive education at your school? Perhaps you are currently working in an inclusive classroom and looking for effective strategies. Lean into this deep-dive article on inclusive education to gather a solid understanding of what it means, what the research shows, and proven strategies that bring out the benefits for everyone.

What is inclusive education? What does it mean?

Inclusive education is when all students, regardless of any challenges they may have, are placed in age-appropriate general education classes that are in their own neighborhood schools to receive high-quality instruction, interventions, and supports that enable them to meet success in the core curriculum (Bui, Quirk, Almazan, & Valenti, 2010; Alquraini & Gut, 2012).

The school and classroom operate on the premise that students with disabilities are as fundamentally competent as students without disabilities. Therefore, all students can be full participants in their classrooms and in the local school community. Much of the movement is related to legislation that students receive their education in the least restrictive environment (LRE). This means they are with their peers without disabilities to the maximum degree possible, with general education the placement of first choice for all students (Alquraini & Gut, 2012).

Successful inclusive education happens primarily through accepting, understanding, and attending to student differences and diversity, which can include physical, cognitive, academic, social, and emotional. This is not to say that students never need to spend time out of regular education classes, because sometimes they do for a very particular purpose — for instance, for speech or occupational therapy. But the goal is this should be the exception.

The driving principle is to make all students feel welcomed, appropriately challenged, and supported in their efforts. It’s also critically important that the adults are supported, too. This includes the regular education teacher and the special education teacher , as well as all other staff and faculty who are key stakeholders — and that also includes parents.

The research basis for inclusive education

Inclusive education and inclusive classrooms are gaining steam because there is so much research-based evidence around the benefits. Take a look.

Benefits for students

Simply put, both students with and without disabilities learn more . Many studies over the past three decades have found that students with disabilities have higher achievement and improved skills through inclusive education, and their peers without challenges benefit, too (Bui, et al., 2010; Dupuis, Barclay, Holms, Platt, Shaha, & Lewis, 2006; Newman, 2006; Alquraini & Gut, 2012).

For students with disabilities ( SWD ), this includes academic gains in literacy (reading and writing), math, and social studies — both in grades and on standardized tests — better communication skills, and improved social skills and more friendships. More time in the general classroom for SWD is also associated with fewer absences and referrals for disruptive behavior. This could be related to findings about attitude — they have a higher self-concept, they like school and their teachers more, and are more motivated around working and learning.

Their peers without disabilities also show more positive attitudes in these same areas when in inclusive classrooms. They make greater academic gains in reading and math. Research shows the presence of SWD gives non-SWD new kinds of learning opportunities. One of these is when they serve as peer-coaches. By learning how to help another student, their own performance improves. Another is that as teachers take into greater consideration their diverse SWD learners, they provide instruction in a wider range of learning modalities (visual, auditory, and kinesthetic), which benefits their regular ed students as well.

Researchers often explore concerns and potential pitfalls that might make instruction less effective in inclusion classrooms (Bui et al., 2010; Dupois et al., 2006). But findings show this is not the case. Neither instructional time nor how much time students are engaged differs between inclusive and non-inclusive classrooms. In fact, in many instances, regular ed students report little to no awareness that there even are students with disabilities in their classes. When they are aware, they demonstrate more acceptance and tolerance for SWD when they all experience an inclusive education together.

Parent’s feelings and attitudes

Parents, of course, have a big part to play. A comprehensive review of the literature (de Boer, Pijl, & Minnaert, 2010) found that on average, parents are somewhat uncertain if inclusion is a good option for their SWD . On the upside, the more experience with inclusive education they had, the more positive parents of SWD were about it. Additionally, parents of regular ed students held a decidedly positive attitude toward inclusive education.

Now that we’ve seen the research highlights on outcomes, let’s take a look at strategies to put inclusive education in practice.

Inclusive classroom strategies

There is a definite need for teachers to be supported in implementing an inclusive classroom. A rigorous literature review of studies found most teachers had either neutral or negative attitudes about inclusive education (de Boer, Pijl, & Minnaert, 2011). It turns out that much of this is because they do not feel they are very knowledgeable, competent, or confident about how to educate SWD .

However, similar to parents, teachers with more experience — and, in the case of teachers, more training with inclusive education — were significantly more positive about it. Evidence supports that to be effective, teachers need an understanding of best practices in teaching and of adapted instruction for SWD ; but positive attitudes toward inclusion are also among the most important for creating an inclusive classroom that works (Savage & Erten, 2015).

Of course, a modest blog article like this is only going to give the highlights of what have been found to be effective inclusive strategies. For there to be true long-term success necessitates formal training. To give you an idea though, here are strategies recommended by several research studies and applied experience (Morningstar, Shogren, Lee, & Born, 2015; Alquraini, & Gut, 2012).

Use a variety of instructional formats

Start with whole-group instruction and transition to flexible groupings which could be small groups, stations/centers, and paired learning. With regard to the whole group, using technology such as interactive whiteboards is related to high student engagement. Regarding flexible groupings: for younger students, these are often teacher-led but for older students, they can be student-led with teacher monitoring. Peer-supported learning can be very effective and engaging and take the form of pair-work, cooperative grouping, peer tutoring, and student-led demonstrations.

Ensure access to academic curricular content

All students need the opportunity to have learning experiences in line with the same learning goals. This will necessitate thinking about what supports individual SWDs need, but overall strategies are making sure all students hear instructions, that they do indeed start activities, that all students participate in large group instruction, and that students transition in and out of the classroom at the same time. For this latter point, not only will it keep students on track with the lessons, their non-SWD peers do not see them leaving or entering in the middle of lessons, which can really highlight their differences.

Apply universal design for learning

These are methods that are varied and that support many learners’ needs. They include multiple ways of representing content to students and for students to represent learning back, such as modeling, images, objectives and manipulatives, graphic organizers, oral and written responses, and technology. These can also be adapted as modifications for SWDs where they have large print, use headphones, are allowed to have a peer write their dictated response, draw a picture instead, use calculators, or just have extra time. Think too about the power of project-based and inquiry learning where students individually or collectively investigate an experience.

Now let’s put it all together by looking at how a regular education teacher addresses the challenge and succeeds in using inclusive education in her classroom.

A case study of inclusive practices in schools and classes

Mrs. Brown has been teaching for several years now and is both excited and a little nervous about her school’s decision to implement inclusive education. Over the years she has had several special education students in her class but they either got pulled out for time with specialists or just joined for activities like art, music, P.E., lunch, and sometimes for selected academics.

She has always found this method a bit disjointed and has wanted to be much more involved in educating these students and finding ways they can take part more fully in her classroom. She knows she needs guidance in designing and implementing her inclusive classroom, but she’s ready for the challenge and looking forward to seeing the many benefits she’s been reading and hearing about for the children, their families, their peers, herself, and the school as a whole.

During the month before school starts, Mrs. Brown meets with the special education teacher, Mr. Lopez — and other teachers and staff who work with her students — to coordinate the instructional plan that is based on the IEPs (Individual Educational Plan) of the three students with disabilities who will be in her class the upcoming year.

About two weeks before school starts, she invites each of the three children and their families to come into the classroom for individual tours and get-to-know-you sessions with both herself and the special education teacher. She makes sure to provide information about back-to-school night and extends a personal invitation to them to attend so they can meet the other families and children. She feels very good about how this is coming together and how excited and happy the children and their families are feeling. One student really summed it up when he told her, “You and I are going to have a great year!”

The school district and the principal have sent out communications to all the parents about the move to inclusion education at Mrs. Brown’s school. Now she wants to make sure she really communicates effectively with the parents, especially as some of the parents of both SWD and regular ed students have expressed hesitation that having their child in an inclusive classroom would work.

She talks to the administration and other teachers and, with their okay, sends out a joint communication after about two months into the school year with some questions provided by the book Creating Inclusive Classrooms (Salend, 2001 referenced in Salend & Garrick-Duhaney, 2001) such as, “How has being in an inclusion classroom affected your child academically, socially, and behaviorally? Please describe any benefits or negative consequences you have observed in your child. What factors led to these changes?” and “How has your child’s placement in an inclusion classroom affected you? Please describe any benefits or any negative consequences for you.” and “What additional information would you like to have about inclusion and your child’s class?” She plans to look for trends and prepare a communication that she will share with parents. She also plans to send out a questionnaire with different questions every couple of months throughout the school year.

Since she found out about the move to an inclusive education approach at her school, Mrs. Brown has been working closely with the special education teacher, Mr. Lopez, and reading a great deal about the benefits and the challenges. Determined to be successful, she is especially focused on effective inclusive classroom strategies.

Her hard work is paying off. Her mid-year and end-of-year results are very positive. The SWDs are meeting their IEP goals. Her regular ed students are excelling. A spirit of collaboration and positive energy pervades her classroom and she feels this in the whole school as they practice inclusive education. The children are happy and proud of their accomplishments. The principal regularly compliments her. The parents are positive, relaxed, and supportive.

Mrs. Brown knows she has more to learn and do, but her confidence and satisfaction are high. She is especially delighted that she has been selected to be a part of her district’s team to train other regular education teachers about inclusive education and classrooms.

The future is very bright indeed for this approach. The evidence is mounting that inclusive education and classrooms are able to not only meet the requirements of LRE for students with disabilities, but to benefit regular education students as well. We see that with exposure both parents and teachers become more positive. Training and support allow regular education teachers to implement inclusive education with ease and success. All around it’s a win-win!

Lilla Dale McManis, MEd, PhD has a BS in child development, an MEd in special education, and a PhD in educational psychology. She was a K-12 public school special education teacher for many years and has worked at universities, state agencies, and in industry teaching prospective teachers, conducting research and evaluation with at-risk populations, and designing educational technology. Currently, she is President of Parent in the Know where she works with families in need and also does business consulting.

You may also like to read

- Inclusive Education for Special Needs Students

- Teaching Strategies in Early Childhood Education and Pre-K

- Mainstreaming Special Education in the Classroom

- Five Reasons to Study Early Childhood Education

- Effective Teaching Strategies for Special Education

- 6 Strategies for Teaching Special Education Classes

Categorized as: Tips for Teachers and Classroom Resources

Tagged as: Curriculum and Instruction , High School (Grades: 9-12) , Middle School (Grades: 6-8) , Pros and Cons , Teacher-Parent Relationships , The Inclusive Classroom

- Online Education Specialist Degree for Teache...

- Online Associate's Degree Programs in Educati...

- Master's in Math and Science Education

- Skip to content

- Skip to search

- Staff portal (Inside the department)

- Student portal

- Key links for students

Other users

- Forgot password

Notifications

{{item.title}}, my essentials, ask for help, contact edconnect, directory a to z, how to guides.

- Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation

Inclusive education case studies discussion guide

This resource was originally published 26 August 2020.

- Inclusive education case studies discussion guide (PDF 234 KB)

This discussion guide has been created to support principals, executive and teachers to unpack and reflect on CESE’s case studies on inclusive education in NSW schools and to consider how the content is relevant to their own school contexts.

This discussion guide is designed to be used in a group setting with colleagues from your school or network. If working with colleagues from other schools, consider sharing differences and similarities in inclusive education at your schools during the discussion.

- Working in pairs or a small group, allocate 1-2 case studies to each person.

- What are the main themes covered in this case study?

- What examples are provided for each theme?

- What else stood out to you?

- Explain the context of the school you read about and share the main themes covered in the case study.

- Identify which of the themes can be seen at your school. Discuss similarities or differences in what this looks like in your school compared to the case study school.

- Identify themes or examples from the case study that could be put in place in your school or classroom. Discuss what action is needed to do this.

- Consider who should be involved in the actions you’ve identified in point.

- What can you do to get started on implementing some of these actions?

Related resources

- Case studies on inclusive education

- Practical guides for educators

Business Unit:

- PRO-ED Order Form

- Research & Testing

- Publish with ProEd

- Reprint Permission

Case Studies for Inclusive Schools-Third Edition-E-Book

Peggy l. anderson.

- Product Number: 14349

- ISBN 978-1-416-40654-9

- Format: EBOOK

- Weight 0 lbs.0 oz.

This product is delivered by one of our digital delivery partners. Use this link to purchase now.

Description

Case Studies for Inclusive Schools, Third Edition is a major revision that provides a stimulating format for understanding a variety of inclusion issues in the schools. The content focuses on problem solving from a collaborative perspective. Teacher education students and teaching professionals can use this excellent text to explore the different attitudes, problems, and situations that arise in the schools.

Typical problems associated with integrating disabled students into general education classrooms are highlighted in the 57 case studies. The content of the case study questions in the book reflects current instructional concerns including:

- assistive technology

- curriculum accessibility

- response to intervention

E-Book Features and Benefits

- Accessible from any device with Internet access

- Search and find using keywords

- Add notes and bookmarks as you read

203 pages •E-Book • ©2013

To see more of this product's contents:

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- About the Author

Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning for Student Success

- Case Studies for Inclusion

- Teaching & Learning

- Teaching Resources

- Inclusive Teaching

The Power of Case Studies In Inclusive Teaching

When designing your courses, develop learning goals that include preparing students to apply the knowledge developed in your course to solving societal problems in an increasingly diverse and changing world. Even if your course content does not easily allow for discussions about social issues, case studies that connect your course content to issues impacting underrepresented individuals and communities create meaningful learning opportunities.

Video by Dr. Carol Babyak: Case Studies for Inclusive Teaching in STEM

Sample Case Study Resources:

National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science

http://sciencecases.lib.buffalo.edu/collection/

Case Studies in Business

https://www.prismdiversity.com/news/diversity_articles.html

Case Studies for Diversity & Social Justice Education

https://www.tolerance.org/magazine/fall-2014/excerpt-case-studies-on-diversity-social-justice-education

About Case Studies in Business: The Exclusivity Problem in Case Study Use

https://haas.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/EGAL-_Case-Compendium_-Analysis_Final.pdf

Case Studies in a Variety of Fields

https://www.fordfoundation.org/media/4871/ff_dei_casestudies_final.pdf

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Case studies for inclusive schools

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

91 Previews

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

EPUB and PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by [email protected] on February 22, 2010

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

Search with any image

Unsupported image file format.

Image file size is too large..

Drag an image here

- Health, Fitness & Dieting

- Psychology & Counseling

Sorry, there was a problem.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

Case Studies for Inclusive Schools 3rd Edition

- ISBN-10 1416405445

- ISBN-13 978-1416405443

- Edition 3rd

- Publisher Pro Ed

- Publication date September 15, 2012

- Language English

- Dimensions 8.5 x 0.5 x 10.9 inches

- Print length 190 pages

- See all details

Products related to this item

Product details

- Publisher : Pro Ed; 3rd edition (September 15, 2012)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 190 pages

- ISBN-10 : 1416405445

- ISBN-13 : 978-1416405443

- Item Weight : 1.29 pounds

- Dimensions : 8.5 x 0.5 x 10.9 inches

- #511 in Medical Forensic Psychology

- #600 in Popular Forensic Psychology

- #5,332 in Psychology (Books)

About the author

Peggy l. anderson.

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

- About Amazon

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell products on Amazon

- Sell on Amazon Business

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Become an Affiliate

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Make Money with Us

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Amazon and COVID-19

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Amazon Assistant

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

- Open access

- Published: 18 December 2023

Challenges and opportunities of AI in inclusive education: a case study of data-enhanced active reading in Japan

- Yuko Toyokawa ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2386-3303 1 ,

- Izumi Horikoshi 2 ,

- Rwitajit Majumdar 2 , 3 &

- Hiroaki Ogata 2

Smart Learning Environments volume 10 , Article number: 67 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

5371 Accesses

4 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

In inclusive education, students with different needs learn in the same context. With the advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, it is expected that they will contribute further to an inclusive learning environment that meets the individual needs of diverse learners. However, in Japan, we did not find any studies exploring current needs in an actual special needs context. In this study, we used the learning and evidence analysis framework (LEAF) as a learning analytics-enhanced learning environment and employed Active Reading as an example learning task to investigate the challenges and possibilities of applying AI to inclusive education in the future. Two students who attended a resource room formed the context. We investigated learning logs in the LEAF system while each student executed a given learning task. We detected specific learning behaviors from the logs and explored the challenges and future potential of learning with AI technology, considering human involvement in orchestrating inclusive educational practices.

Introduction

Efforts are underway to promote the realization of inclusive education and the widespread development of inclusive environments in which all children can learn together irrespective of their disabilities, cultural backgrounds, or socioeconomic status (UNESCO, 2009 ). Inclusive education in Japan primarily focuses on learners with disabilities and aims to enable them to actively participate in and contribute to society independently in an inclusive manner (MEXT, 2012 ). In general, not only in Japan, but also in many other countries, students with mild disabilities, such as those with developmental disorders or disabilities (DD), study alongside non-disabled learners in the same learning environment in regular classes in inclusive education. In diverse but constrained learning contexts with different types of learners, teachers have difficulty orchestrating multiple flows of information and tasks (Dillenbourg, 2013 ). Although there are many different types of educational practices within inclusive education, special education (SE) approaches can be used to meet and support the unique learning needs of learners with special needs in a learning environment (Bryant et al., 2019 ).

In regular classes, all learners engage in learning at the same pace, but students with learning difficulties (LD), who are said to be less efficient at processing information, tend to have trouble catching up in class compared with other students (Gersten et al., 2001 ). This may cause depression, poor academic performance, and low self-esteem (Peterson et al., 2001 ; Rose, 2019 ). For such learners, resource rooms or pullout programs can provide extra support outside regular classes (Bryant et al., 2019 ). A resource room under inclusive education in Japan is an independent remedial class in which learners with a relatively mild disability, or those who tend to demonstrate some difficulties, leave their regular classes and receive support according to their needs (MEXT, 2020 ). In the learning context, Toyokawa and her colleagues observed that students in a resource room in Japan implemented daily learning activities with a digital e-book reader called BookRoll in the learning and evidence analysis framework (LEAF) with learning analytics (LA) technology and found the possibility of detecting their stumbling points and strengths in their learning logs (Toyokawa et al., 2022 ). A large amount of data can be accumulated from daily learning using LEAF. However, the utilization of LA technology such as LEAF for learners with special needs has not been researched extensively in an inclusive Japanese learning environment. More than 30 years ago, Yin argued about the future-oriented investigation of new technology, including using artificial intelligence (AI) in SE (Yin & Moore, 1987 ). Research on inclusive education using AI has been rapidly gaining attention worldwide (Kazimzade et al., 2019 ; Salas-Pilco et al., 2022 ). However, just as Kazimzade and her colleagues mentioned the lack of exchange between AI and disability research in their book chapter (Kazimzade et al., 2019 ), the lack of progress in the context of special needs is also the case in Japan. Therefore, we propose integrating LA and AI technology to effectively orchestrate learning for learners with special needs in inclusive education. Focusing on literacy skills that underlie all aspects of learning and daily life and bearing in mind the importance of reading, we selected active reading (AR) in an LA-enhanced learning environment as one task and investigated the challenges and possibilities of AI integration.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In the second section, an overview of inclusive education in Japan, LA-enhanced learning environments, and AI in inclusive education is presented. In the third section, the research objectives and a question are stated, and then the LEAF components are introduced as a learning environment for this study, followed by participants and learning tasks. Data collection and interpretation are then described. The following section presents the findings of the case study to answer the research question. In the Discussion section, possible solutions for learning with AI are discussed along with limitations for future research. Finally, the implications and contributions of the study are highlighted.

Literature review

Special education in inclusive education in japan.

In inclusive educational environments, students study together in the same class, regardless of their difficulties. Inclusive education is defined as education in which students with disabilities have access to the standard curriculum in a general education classroom (Bryant et al., 2019 ). In the Japanese inclusive context, students with relatively mild DD [e.g., autism, low vision, speech impairment, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and LD] attend the same classes as students without DD. In Japan, the number of students with DD is increasing. According to a report from the Ministry of Education in Japan (MEXT), the number was approximately 600,000 in 2012 and 800,000 in 2022, or approximately two to three students with DD out of every thirty students in one class (MEXT, 2022a ). For such learners, a resource room or pullout program is available, and which provides extra support outside of regular classes upon request (Bryant et al., 2019 ). The support system differs depending on needs, but attending a resource room is the primary form of receiving additional support at school for learners with DD in the current inclusive education system in Japan. The Japanese resource room is an independent supplementary class in which learners with relatively mild disabilities or those who tend to show some difficulty leaving regular classes receive special support equivalent to self-reliance activities according to their needs (MEXT, 2020 ). Learners with various difficulties can receive support tailored to their individual needs, such as social or communication skills training and academic support, such as reading, writing, and math. In this respect, resource rooms can be said to be a part of SE, in which learners with difficulties can receive support based on their needs. SE is an approach designed to meet the unique learning needs of individuals with disabilities, such as students with different learning, behavioral, social communication, and basic functional needs (Bryant et al., 2019 ). Currently, the resource room service is provided at elementary schools, junior high schools, and high schools in Japan, but the situation is that there are students who need support but are left unattended for reasons such as a lack of instructors (MEXT, 2022b ).

Information and communication technology (ICT) in education is said to be progressing in Japan, but the penetration rate lags far behind that of other countries when looking at the average Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (National Institute for Educational Policy Research, 2022 ). Research on the use of ICT in SE in Japan has primarily focused on alternative and assistive technologies and teaching materials (Kinoshita et al., 2023 ; Kumagai & Nagai, 2022 ). While research on technical assistance has garnered considerable attention in the literature, there is a notable gap in research pertaining to special needs in inclusive education from the lens of LA. This gap is especially pronounced in the context of Japan, where the utilization of learning log data and AI technology for this purpose remains unexplored.

Learning analytics and support for learners with special needs

Using e-learning tools such as ICT, it is possible to collect and accumulate learning log data that record the learning process. LA, which is research on the contribution of learning logs to learning and educational activities, has attracted attention. LA is research aimed at improving and enhancing teaching and learning by analyzing and visualizing accumulated log data and providing feedback based on the visualization through daily learning activities (Bodily & Verbert, 2017 ; Siemens & Baker, 2012 ). Using the LA learning system LEAF, Toyokawa and her colleagues traced students' handwriting from their interaction performance in the daily learning of students attending a resource room in an elementary school in Japan to investigate their learning performance and difficulties (Toyokawa et al., 2022 ). In this study, they successfully visualized and observed learning behaviors such as students’ learning difficulties using penstroke analysis. This study demonstrated the possibility of using log data to assist learners with special needs and support teachers. To cite two overseas examples, first, a pilot study was conducted in which a learning game for cognitively impaired people was developed and learning behavior was observed from interaction and performance data using LA (Buzzi et al., 2016 ). The learning game allows for assigning and monitoring tasks remotely, encouraging learning according to individual needs, and analyzing the results obtained from learning. The second example is an attempt to provide support by opening a learner model using LA and detecting reading difficulties, such as learning style and cognitive traits, from the demographic submodel and reading profile (Mejia et al., 2016 ). This study underscores the importance that learners are aware of their own learning styles and cognitive limitations. All three cases sought to support learners with special needs and teachers using LA. It is expected that the LA-enhanced learning environment will further improve learning and education with AI technology in the future; however, in Japan, LA research to support learning has not yet become popular in SE. Furthermore, limited research has provided AI-based support for the unique requirements of inclusive education.

AI in inclusive education

AI has the capacity to harness learners' behavioral data, ultimately delivering personalized and tailored educational services to cater to individual needs, as suggested by Margetts and Dorobantu ( 2019 ). AI also aids in making more accurate predictions and planning learning. According to the same study, some local governments in the UK are already using predictive analytics to anticipate future needs in areas such as SE and children’s social services. This prediction can also be applied to identify students who are considered to be “at risk” (Cano & Leonard, 2019 ; Slowík et al., 2021 ). Such warning systems are already in use in the United States, New Zealand, and Canada.

AI has also had a significant impact on Japanese society. Although educational big data have been accumulated through the use of ICT and machine learning, compared to other countries, it is obvious that in Japan, AI technology in the educational field lags behind the national level. Kazimzade and her colleagues argue that most of today's adaptive education systems rarely consider diversity and that it is necessary to create heterogeneous data sets to train AI in inclusive learning environments to replicate our diverse societies (Kazimzade et al., 2019 ). This lack of heterogeneous datasets is particularly evident in the context of SE in inclusive education in Japan. In this respect, this research is one of the few to focus on learning support using AI for minority learners who need special support in Japan. In this study, we investigated how to support learners with special needs in inclusive education using AI technology. The research methods and experimental procedures are described in the next section.

Research objective

Given the need to understand how AI-driven approaches can realize future SE in inclusive education in the Japanese context, we conducted a case study to explore the current needs, challenges, and opportunities of implementing AI.

What are the challenges and opportunities of AI-driven services for active reading of learners with special needs in inclusive education?

Case studies have gained considerable acceptance as valid research methods in a wide range of fields. In particular, Yin’s case study is said to be reliable for connecting the underlying theory and practice (Zainal, 2007 ). A case study enables us to understand behavioral states from the perspective of learners and subjects, which is said to be useful in explaining the complexity of real learning situations in detail (Zainal, 2007 ). Research on learning in SE is a large field; however, only a limited number of individuals can be selected as research subjects. It is valuable to accumulate data obtained from daily learning in a natural way, and we consider this experiment “a unique way of observing natural phenomena present in a series of data,” as defined by Yin’s case study (Zainal, 2007 ). Next, we present the LEAF system as a reading learning environment and workflow that were utilized to investigate the challenges and opportunities of AI applications.

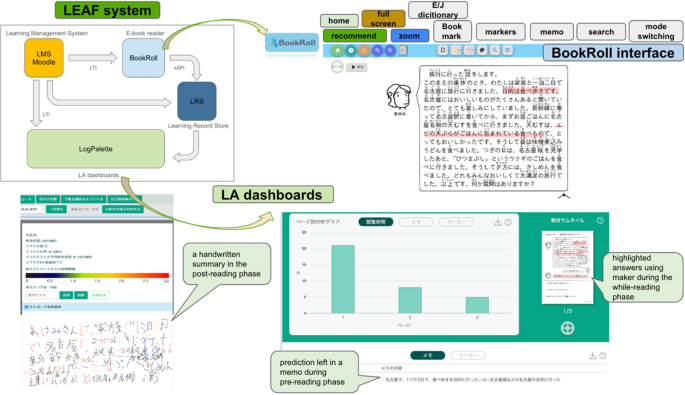

LEAF system and its components used in a case study

We propose the use of the LEAF as an LA-enhanced AR learning environment for inclusive education. LEAF is a learning environment framework that includes BookRoll, an e-learning material browsing system that allows learners to view digital learning materials anytime and anywhere, and a group of LA dashboard modules (LogPalette) that analyze and visualize the logs learned using BookRoll (Ogata et al., 2018 ). BookRoll includes reading-facilitating functions such as markers that can be used for highlighting and memos that can be added as annotations. Learners can choose input methods such as keyboards, direct handwriting using a stylus pen, and text conversion from voice input. Learning logs, such as the contents of memos, portions highlighted with markers and their content, number of operations, and viewing time, are accumulated in the Learning Record Store and analyzed and visualized in LogPalette. Figure 1 illustrates the LEAF framework with BookRoll and LogPalette interfaces.

Examples of the BookRoll interface, the LA dashboard, and the pen stroke analysis interface in the LEAF framework

Participants and study context

The participants were two twelve-year-old boys (boys 1 and 2). Boy 1 attended a resource room for six years to receive social communication training and had received special support before entering elementary school. Boy 2 was diagnosed with autism and attended a resource room for six years. He received special support before entering elementary school. Resource rooms are for students with relatively mild difficulties, and many who attend these rooms have not been diagnosed with disabilities. The decision on whether one is to receive special support in a resource room is made by the school principal, following an appropriate understanding of the actual situation and a discussion with the school committee (MEXT, 2020 ). Therefore, in this study, no details on the difficulty level were available for each child. The participants were asked to perform AR at home with their mothers. Written informed consent was obtained from the guardians of the students. First, the flow of learning activities was explained to the students and their mothers. Then, all four AR activities for Boy 1 which lasted about for one hour, and three AR activities for Boy 2, which lasted approximately one and a half hours were observed by a researcher. They chose a device to use, either a PC or an iPad, and chose an input method, such as using a keyboard for typing or a stylus pen for handwriting. In Japan, under the Global and Innovation Gateway for All (GIGA) school initiatives, each student is provided with one device. Both students had no problems operating PCs and/or tablets and typing on keyboards at home by themselves. We asked them to work on their reading on their favorite device with the intention of doing it in a stress-free environment as much as possible. A case study was conducted on two students using BookRoll. We explain the reading-learning activities and AR procedure in the next section.

AR learning task

The two boys read the same four reading materials. They read individual stories using BookRoll. The reading process followed the AR process, which was performed using BookRoll in a past study (Toyokawa et al., 2023 ). First, in the pre-reading phase, participants were asked to have an image of the story they were going to read by looking at the page (title, pictures, etc.) and write their predictions in a memo. They were then asked to formulate questions based on their thoughts. Questions were also asked to be recorded in a memo. Each story contained questions on comprehension. While they read the text, they read the story as they looked for answers while marking the answers to the question with a marker directly on BookRoll. In the post-reading phase, participants reflected on their reading and wrote the content of the story in their own words. One week later, they were asked to recall the story and write about what they had remembered. We additionally communicated the AR learning process to both the resource room teacher of Boy 1 and the mother of Boy 2 with the dashboard, engaging in a reflective discussion and receiving their valuable feedback. The objectives and activities for each phase of the AR activities are explained in Table 1 .

Data collection and analysis

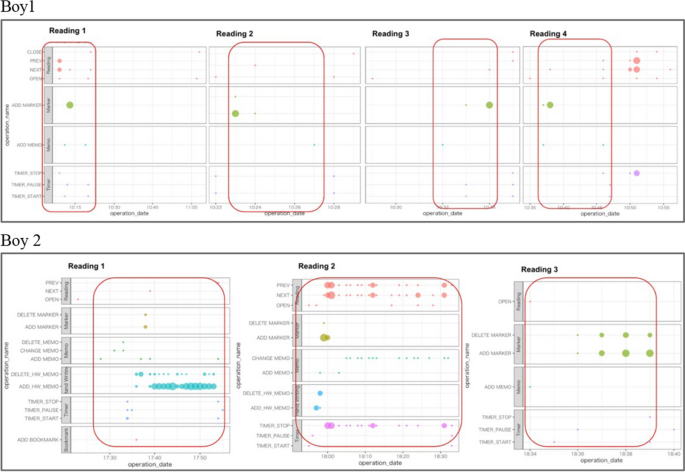

The time spent reading and operation logs were investigated to understand each participant's AR process. First, the time taken for each reading task was extracted from the time logs, including the time taken to complete one AR session, the time taken to make a prediction and questions in the pre-reading phase, the time taken to answer questions while reading and marking the answers with a marker, and the time taken to write down what was understood in the post-reading phase (Table 2 ). The objective was to check whether there were any characteristics of reading difficulty, such as taking too long to read, input, and output. Then, behaviors such as frequent page flipping, noticeable writing, erasing, and highlighting actions were visualized as a plot (Fig. 2 ) to understand if we could detect any reading difficulties in the logs and at what stage of AR intervention was required. In order to investigate the reading behaviors, logged actions such as OPEN, MEMO, HANDWRITING MEMO, MARKER, NAVIGATION, TIMER, BOOKMARK, and CLOSE were extracted and analyzed, whose descriptions and interpretations of action logs are listed in Table 3 . After the AR learning, as part of the experiment, we asked the resource room teacher of Boy 1 and the mother of Boy 2 to see each student's AR process and the visualized logs, and received their impressions and comments.

Log visualization of the AR behavior among the three students

Analysis of the participants’ time logs

First, we investigated the learning behavioral patterns found in the learning logs regarding the time spent on each AR task. What the two of them have in common is that it took a considerably long time to write a summary (paraphrasing in their own words) after reading. Boy 2 took three times as long as Boy 1 to do the same. The average time spent on summaries for Boy 1 was (m = 6.28 for 3 summaries), which is approximately 76% of the total average AR activity for Boy 1. The average time spent on summaries for Boy 2 was (m = 22.37 for 2 summaries), which is approximately 96% of total AR activity. A summary of the time spent on the AR tasks is presented in Table 2 .

Analysis of the participants’ operation logs

We then attempted to visualize the AR performance of the two participants from the operation log, which is depicted in the plots in Fig. 2 . Overall, we confirmed that the participants progressed to AR according to the following AR procedure: pre-, while-, and post-reading phases. What we could clearly observe from the plots was that during the first AR activity, Boy 2 with LD noticeably wrote and erased his handwriting, and during the second AR activity, he frequently flipped pages, touched the timer, and wrote and erased his memos. The third AR seemed to proceed smoothly without any extra action; however, the fourth AR was not conducted.

Analysis of the stakeholders’ interviews

In general, learners check and reflect on their own learning processes, but this time, we asked the resource room teacher and the mother of Boy 2 to observe the data, reflect on the learning, and give us their comments. Their comments were as follows:

The teacher told us that all learning with paper is stored in a file and shared with the parents during the interviews, which are conducted twice a year. Students' data are always collected and reported to schools. She said that it would be nice if they could accumulate and share what they had learned using (electronic) tools. She also mentioned that parents need to (and want to) know what their children are doing in school. Boy 2’s mother said that her son cannot get rid of his obsession with things he cannot do. Due to this, he cannot move on to the next task, and as a result, he cannot complete the task. She told us that she made posters so that her son could visually check the tasks, but he now makes his own to-do list daily and keeps it in his school bag. She said that being able to see what he is doing through his learning logs helps her understand and accept how he is doing in school.

In this section, we discuss the findings from the case study, which can serve as evidence for identifying future challenges and possibilities related to the application of AI technology to SE in inclusive education.

Erratic learning engagement of students with LD in different phases of the learning activities and during technology usage

Learners have different time engagements and approaches to the same learning task. In this study on AR activities, Boy 2 required more time than Boy 1 (Table 2 ). The observations demonstrated that Boy 2 approached each activity carefully. He paid particular attention to the order in which things appeared in the story and the flow of AR itself. He was initially overly focused then lost concentration, gave up on the way, and could not complete the tasks. It was also found from the observations that it took time for him to write his summary with a stylus pen on an iPad for the first AR activity. He appeared unfamiliar with the act of writing directly on the iPad screen with a pen, but enjoyed using a new tool. He did not use handwriting during the second AR session but used the keyboard with which he was already familiar. From the logs and observations, we understood that it might be time consuming for some learners to perform knowledge output activities, such as writing what they have understood.

Regarding technology use (Fig. 2 ), Boy 1 had relatively fewer extra actions in the logs besides AR activities, whereas Boy 2 had a greater number of extra actions that demonstrated fixation behavior on ICT features. For example, several operation logs were detected in terms of handwritten memos, such as ADD and DELETE, during the first task. In the second reading task, several additional page movements and timer operations were observed (Fig. 2 ). In the third task, it was observed that AR was completed without additional operations on the logs. However, it was observed that he lost concentration and motivation. Consequently, he was unable to start or complete the fourth task. We also found that learners may end up concentrating on things other than learning, such as using e-learning features, such as timers. These pedagogical challenges must be addressed when creating learning designs for students with special needs.

Varied understanding of stakeholders about data-driven learning

In this study, we faced difficulty obtaining the consent of the guardians for the experiments because AR was not the type of learning support that they had originally requested. Some parents did not consent to the collection of their children’s learning data. During the interviews, we found that there was still a lack of awareness about data-driven learning, such as how BookRoll is actually used for learning and how logs are used to support learning. However, it was also clear that the teacher and the mother were looking forward to the possibility of employing data-driven learning and sharing learning processes effectively using technology.

In this section, we first discuss the limitations of the current study and then address the possibilities and challenges of AI-driven special needs learning in inclusive education.

Limitations and solutions for the sample size

One of the limitations of the current study is its sample size, as there were only two subjects. In resource rooms in Japan, class activities are usually offered by one teacher to either individual students or small groups for a limited time. Therefore, only a limited number of students can receive support each day. In addition, not all schools in Japan have resource rooms. Hence, it was difficult to recruit a large number of participants for this study, even if subjects were collected from multiple schools. Additionally, some parents were not willing to participate in the research and did not consent, making recruiting subjects a major challenge. Thus, it may be difficult to apply and generalize the results of the current study to a broader context. In addition, the small sample size may suggest the possibility of bias in the data analysis. To minimize this possibility, we used log data from the participants' learning process and attempted to visualize the data in plots instead of collecting data from conventional sources such as surveys, tests, and observations. Two researchers performed the confirmation and interpretation of the logs. The results confirmed that differences in the reading process between the two participants, such as differences in how they approached AR and how they used the tools, were interpreted in the same way. Learning evaluations and decision-making regarding whether to provide students with support have often been made based on the evaluation of learners' artifacts, observations, survey results, communication among stakeholders, and subjective measures such as teachers' perceptions or parents' intentions, which may lead to biased judgments or unnecessary support. Although these assessment methods remain essential, by being able to clearly show artifacts and the learning process through log visualization, not only researchers, but also school administrators, teachers, and parents can objectively judge a child's learning progress and make decisions about support provision.

Improving learning design for continuous learning

As mentioned in the existing literature, the majority of research and experiments on reading-based learning typically conclude at the end of the study period, often failing to foster lasting reading habits among learners (Gersten et al., 2001 ). We must acknowledge that there was a need to repeatedly conduct AR activities over time in this study as well. Additionally, it is difficult for learners who have difficulty concentrating to continue learning if they are not satisfied with their learning activities. Designing learning activities to suit learners’ needs and preferences is necessary for learning satisfaction and continuation (Salas-Pilco et al., 2022 ). The AR procedure employed in this study was segmented into three phases. However, taking learners’ attention spans into account, it is imperative to focus on AI applications that offer precise, individualized guidance and feedback for more effective interventions. AI assists learners in learning at their own pace outside the classroom and school. Learners can then use the dashboard to monitor the learning process and learn to reflect and understand so that they can develop and improve their cognitive and metacognitive skills. Learning activities and pedagogical approaches should be improved so that learners with special needs can continue learning independently even after the experimental period ends.

Implications for usability enhancement of the LEAF platform for SE

Existing dashboards in LEAF have an environment in which general students can reflect. However, current AR-D in LEAF may or may not be suitable for learners with special needs. Therefore, we consider updating and improving the performance and content of the functions and systems regarding the concept of the Universal Design of Learning (UDL) (Rose & Meyer, 2002 ). This is because system affordances and dashboard designs can significantly impact perception, behavior, and acquisition. Improvements in the usability, accessibility, and reliability of the system are often indicated in past studies (Buzzi et al., 2016 ; Mejia et al., 2016 ). Improving the system and developing an AI-driven LA dashboard based on real data should be considered so that all learners, including students with special needs and their stakeholders, can easily manage their learning and reflect on it, which will help mitigate learners’ difficulties.

Log data-driven solutions and potentials of AI for AR

In this study, we observed variations in the time needed for AR and the approach adopted for the same learning task among different learners. Students with LD have been found to process information inefficiently and not to understand appropriate reading strategies, which can lead to unexpected learning failures in comprehension and decoding (Gersten et al., 2001 ). For such learners, it is essential to present the steps of “what has been achieved” and “what needs to be done” explicitly and offer cues to help them complete the task and progress to the next step (Gersten et al., 2001 ). In today's data-driven learning environments, such as LEAF, it is possible to notify learners of task completion and reward them to boost their self-esteem and motivation to read and learn. The utilization of log data may lead to more efficient learning. Further, AI complements learners' previous knowledge and skills. For example, it would be possible to use natural language generation to support reading-learning by navigating the contents and the flow of reading activities in an easy-to-understand manner using both text and audio. First, we demonstrate each phase of a potential AI-driven AR approach in the future based on the results of a case study.

[Pre-reading phase]

Although learners with LD are good at many things, they are said to fall behind other students in reading comprehension because of difficulties like making predictions and having limited imagination and cognitive biases (Randi et al., 2010 ). However, such students can be instructed to improve their reading comprehension by using pre-reading strategies that activate their attention and prior knowledge (Gersten et al., 2001 ). AR uses information such as visual and auditory aids to help learners create an image of what they are about to read before (or even while) reading. However, for students who are struggling with reading, AI automatically measures the time required, the length, and the difficulty of a text, integrates it with information from the accumulated learner's data such as their reading speed, weakness, and preferences, and assists them in the reading process. For example, for students who have difficulty imagining textual information, AI generates and provides visual information to make visualization easier. For learners who have difficulty following the order of learning activities, AI can aide learners with audio or textual guides or ask them what they want next to guide their learning. It may also display filters to help students choose what to do next or use past data to calculate the time required for each learner to learn and intervene to complete a task at the appropriate time. In addition, it may activate the learners' existing knowledge by guiding them to vocabulary quizzes and chapters related to the reading content, and provide information relevant to the content they are about to read. In this way, when learners become stuck and cannot predict or create an image of the story during the pre-reading phase, AI may intervene to stimulate their previous knowledge and offer assistance, such as by providing an advanced organizer framework (Idol-Maestas, 1985 ) to guide them on what to do next.

[While-reading phase]

There are various types of reading difficulties given as examples, such as difficulty with concentrating on one thing, following procedures, completing task thing through to the end, reading information from a text alone, and inability to empathize with the emotions and viewpoints of the characters, or just simply taking too long to read (Randi et al., 2010 ; Ryan, 2007 ). AI can offer cues to help learners maintain focus on their reading objectives and assist them in identifying corrective actions when necessary steps are not completed. When unnecessary actions are detected, AI can redirect learners' attention towards the task at hand. AI may thus enable learners with special needs to work on AR learning alone, which was said to be difficult for them (Gersten et al., 2001 ). At the current stage, we developed and tested a text recommender in the LEAF system that automatically recommends reading materials based on the logs from markers used for vocabulary during AR. In the future, AI will recommend reading materials that match learners' levels and preferences based on the outcomes from the AR activities, such as different stroke orders, selecting wrong characters, spelling errors, and frequently used words and content stored in memos. AI will assist in making connections with previously read materials and helping students consolidate and develop what they have read by recommending chapters to review and reading materials to work on next. Moreover, AI may act as a reading agent or invite peers and teachers as intermediaries for reciprocal teaching interventions and mutual guidance that improves reading comprehension through communication with others. In this way, AI may provide opportunities for learners to receive feedback and encouragement from others and cultivate independent abilities in connection with others.

[Post-reading phase]

In this case study, students wrote their understanding of the stories in memos using the keyboard and their handwriting. Currently, the iPad's Speech Recognition function is available for learners who are not good at writing. It is possible for learners to use the voice-to-text function to input what they imagined, understood, and thought about a story into BookRoll memos. This allows for the collection and analysis of data in the LEAF system.

Current reading learning does not end with understanding what was read but requires the ability to develop beyond that and apply information that can be used in real life. These application and practical skills may be enforced through interaction with others. In an inclusive learning environment, learners with and without learning difficulties co-exist. In particular, encouragement from peers may develop learners’ perseverance in the face of challenges and improve their comprehension and learning performance (Gersten et al., 2001 ). For class activities, data-based group formation can be applied in which groups are created to work together to deepen and develop an understanding of what they read. This is possible with the current LEAF, and group formation parameters such as homogeneous, heterogeneous, random, and jigsaw can be adjusted depending on the learning purpose, learner characteristics, and other considerable factors (Liang et al., 2023 ). Further, AI will be able to pair learners who need help with learners who have already completed a task, or create peer help groups based on log data. For example, AI would recommend a human learning companion and/or an AI agent, or called pedagogical agents (Savin-Baden et al., 2019 ), to read together. Peers can be selected from humans or AI in the future, creating an environment that promotes learning and reading together. This may reduce the burden on the teacher in a busy classroom, provide feedback suitable for the individual with the help of AI and the people around it, and manage and orchestrate the class activity efficiently. Depending on the learner’s progress, AI can facilitate a unique inclusive learning experience by potentially involving human intervention and reflection.

AI for facilitating learning reflection and decision-making

Using the LEAF system for AR activities allowed us to capture and visualize participants’ reading processes and detect salient behaviors and insights in learners with special needs. Furthermore, the visualized learning process and artifacts were shared between the resource room teacher and the mother. In the LEAF learning environment, learners can use the dashboard to reflect not only on the results but also on the learning process. Reflection encourages learners’ metacognition by allowing them to reflect on their own thinking, and self-reflection provides an opportunity to evaluate their own cognitive processes (Gersten et al., 2001 ; Silver et al., 2023 ). Generally, learners reflect on their own learning and deepen their understanding, and teachers review their learning and decide what to do next. However, some learners find it difficult to reflect on their own learning. In the AI-driven inclusive education expected in the future, AI may be used to support reflection on reading learning using both text and audio. Using log data from learners’ own learning activities enables more personalized feedback by highlighting interesting and hidden patterns. An AI agent will also play an active role. It will sense “done” or “not done” and provide options for what steps to take while emphasizing what learners can do to increase their self-affirmations. For learners who have difficulty understanding information from graphs and tables, or from texts, audio, and visual images will be automatically selected and added to make it easier for them to understand the information presented on the dashboard to assist in learning comprehension. AI will also automatically explain the data displayed on the dashboard, making it easier to understand not only for learners and teachers but also for parents and other educational supporters. This can improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the decision-making process. For example, learners can decide what to learn next, teachers can choose and plan the next activity, and teachers, school administrators, and parents can decide what kind of support learners will need. AI will further encourage human intervention, making it possible to judge their learning more objectively with the help of stakeholders such as teachers and parents, thus facilitating a unique and comprehensive learning experience.

Data sharing and portability

Data on each student in the SE are necessary to determine the support that should be provided according to the student’s developmental stage. Resource room (and homeroom) teachers are obligated to keep records of students’ learning and progress and to report to the school and parents in accordance with them. Support and data sharing are currently primarily conducted using printouts, which are stored, filed, and shared with parents and schools, along with notes on the teacher’s observations during class. In a data-driven learning environment like LEAF, parents can also use the dashboard to check their child’s growth and objectively consider future support based on logs. One of the potential expectations of a data-driven learning environment is the sharing of learning data widely and throughout life with other stakeholders such as other educational institutions and local governments.

The personal data of learners with special needs are shared and transferred across institutions to ensure that they are adequately supported. Even in the event of a change in the learning environment, such as transferring to a different school, graduating from one institution, or progressing to the next educational stage, past learning and support data can be preserved and transferred upon request. The insights we gained from the teacher interview underscored the significance of the secure and seamless sharing and portability of data. The LEAF system is used by students from elementary schools to universities. It will be possible to safely transfer learning data across multiple learning contexts with the integration of blockchain, such as BOLL (Ocheja et al., 2019 ), and students’ learning logs in BookRoll can be transferred to the next learning context. Further, AI will recommend the relevant schools and/or assist learners in making evaluations and decisions when moving up to higher education or finding employment. However, to enhance safe data sharing and portability, it is necessary to obtain the stakeholders’ understanding of learning using AI technology and enhance the data literacy of teachers and learners as well as that of other stakeholders.

Dissemination and awareness of AI-driven learning

AI has the potential to impact not only students in inclusive education but also teachers and other stakeholders like parents. In today’s learning environment in which education and technology are integrated, teachers are required to possess a wide range of diverse competencies such as technical, pedagogical, and content knowledge (TPACK) to deal with complex learning situations (Mishra & Koehler, 2006 ). According to MEXT ( 2021a ), in order to obtain a teaching license for elementary and junior high school in Japan, all teachers will be required to have practical training regarding special education including nursing care experience, as well as developing data literacy and ICT skills. Past literature has indicated the need for specialized pre-training for learners and teachers (Leshchenko et al., 2020 ; Starks & Reich, 2023 ) and digital literacy and technology (Starks & Reich, 2023 ). The current study further highlighted these needs for teachers and parents. Our findings also implied that learners’ and teachers’ understanding of the potential of new technologies still remains low in Japan, as noted in other countries (DeCoito & Richardson, 2018 ; Hirsto et al., 2022 ; Salas-Pilco et al., 2022 ). We found that not all parents welcome or approve of data-driven learning.

As cited by UNESCO, one of the challenges related to implementing AI in education is transparency and fairness considerations in the collection, use, and dissemination of personal data ( 2019 ). In order to dispel these concerns and gain understanding, it is necessary to disseminate information literacy and provide training not only to learners and teachers but also to other parties involved in supported learning. One of the solutions we suggest includes involving all stakeholders in the learning environment to objectively share a common understanding. This inclusion of stakeholders in the design, development, implementation, and evaluation of systems used for learning could help them understand data- and AI-driven learning, thereby increasing their understanding of its importance. This may also resolve issues such as misunderstandings between stakeholders. To this end, we maintain close contact with local schools, expanding technical and educational support, and continuing to implement supportive and interactive learning.

While some challenges remain, AI-driven learning offers positive impacts for learners, teachers, parents, and all other stakeholders. This pilot study implies that the duties of the resource room teacher were diverse, including, for example, continuously sharing students’ information with other stakeholders like homeroom teachers and parents and providing optimal individualized support to each student. Emerging technologies such as ICT and AI will lead to the efficient management and coordination of class activities, such as improving instruction and creating teaching materials, which will hopefully result in work style reformations. This could include reducing teachers’ workloads and shortening waiting lists of students who are unable to receive support in a resource room due to a lack of human resources and difficulty in coordinating time (MEXT, 2021b ). Furthermore, school administrative support related to special needs education, the creation and sharing of individual education, and various information will become easier, which will directly lead to the improvement of school operations and the enhancement of portability between schools and related organizations. This study highlighted these possibilities through learning with BookRoll and sharing the learning process with teachers and parents on the dashboard. Collaboration with stakeholders expands the learning opportunities for all students in inclusive education.

To date, no study in Japan has investigated the challenges and possibilities of using AI in the context of actual inclusive educational settings from the LA perspective. Therefore, we undertook a case study to explore how an AI-driven approach can materialize the vision of SE as a supportive framework for learners with diverse needs in the context of inclusive education in Japan. In today’s data-enhanced learning environment, it is possible to detect and visualize specific learning behaviors using learning logs obtained from daily learning. By integrating AI technology into the current learning context, we found that individual learners can be provided with more efficient and appropriate learning and reflections on learning. However, while some teachers and parents, such as our participants, look forward to opportunities to objectively reflect on learning and provide further support using AI technology assistance, we realized that obtaining assent and understanding from teachers and parents along with fostering data literacy remains a challenge for future inclusive education utilizing AI.

Our future work includes pursuing the possibilities of an AI-driven inclusive learning environment in which all learners are expected to receive equal learning opportunities and optimal support with the co-progress of stakeholders. This cannot be achieved without a considerable amount of data. In Japan, the GIGA initiative has created an environment for data utilization on a national level. Although it has been pointed out that data utilization has not fully penetrated Japan compared to other countries (MEXT, 2022c ), the country is working to build a large-scale data sphere that supports the use of AI, which has created an environment for the effective use of logs. As the use of educational informatization progresses on a larger scale, the data problems and generalizability concerns found in this study may be resolved. Based on the logs collected from the previous and upcoming implementations, we will derive an AI algorithm that will realize and aim to create an AI-driven inclusive learning environment that can provide individually optimal learning support to each learner in cooperation with stakeholders. From there, we will pursue evaluating the impact of AI and understanding the actual situations for inclusive education.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Artificial intelligence

- Active reading

Blockchain of learning logs

Developmental disorders (or disabilities)

Global and Innovation Gateway for ALL

Information and Communication Technology

- Learning analytics

Learning difficulties

Learning & Evidence Analytics Framework

Learning management system

Learning Record Store

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

Programme for International Student Assessment

- Special education

Special needs education

Survey, Question, Read, Recite, and Review

Survey, Question, Read, Record, Recite, and Review

Technological, Pedagogical, and Content Knowledge

Universal Design for Learning

Bodily, R., & Verbert, K. (2017). Trends and issues in student-facing learning analytics reporting systems research. In Proceedings of the seventh international learning analytics & knowledge conference (pp. 309–318).

Bryant, D. P., Bryant, B. R., & Smith, D. D. (2019). Teaching students with special needs in inclusive classrooms . Sage Publications.

Google Scholar

Buzzi, M. C., Buzzi, M., Perrone, E., Rapisarda, B., & Senette, C. (2016). Learning games for the cognitively impaired people. In Proceedings of the 13th international web for all conference (pp. 1–4).

Cano, A., & Leonard, J. D. (2019). Interpretable multiview early warning system adapted to underrepresented student populations. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 12 (2), 198–211.

Article Google Scholar

DeCoito, I., & Richardson, T. (2018). Teachers and technology: Present practice and future directions. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 18 (2), 362–378.

Dillenbourg, P. (2013). Design for classroom orchestration. Computers & Education, 69 , 485–492.

Gersten, R., Fuchs, L. S., Williams, J. P., & Baker, S. (2001). Teaching reading comprehension strategies to students with learning disabilities: A review of research. Review of Educational Research, 71 (2), 279–320.

Hirsto, L., Valtonen, T., Saqr, M., Hallberg, S., Sointu, E., Kankaanpää, J., & Väisänen, S. (2022). Pupils’ experiences of utilizing learning analytics to support self-regulated learning in two phenomenon-based study modules. In Society for information technology & teacher education international conference (pp. 1682–1688). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE).

Idol-Maestas, L. (1985). Getting ready to read: Guided probing for poor comprehenders. Learning Disability Quarterly, 8 (4), 243–254.

Kazimzade, G., Patzer, Y., & Pinkwart, N. (2019). Artificial intelligence in education meets inclusive educational technology—The technical state-of-the-art and possible directions. In Artificial intelligence and inclusive education: Speculative futures and emerging practices (pp. 61–73).

Kinoshita, T., Imu, Y., & Ishida, S. (2023). [A research trend on the use of ICT in special needs education: Focusing on intellectual and developmental disabilities] Tokubetsushienkyoiku niokeru ICT no rikatsuyo ni kansuru kenkyudoko (in Japanese). Bulletin of the Faculty of Education Chiba University, 71 , 107–115.

Kumagai, H., & Nagai, N. (2022). [Characteristics of information literacy of children attending resource room—Analysis through development and application of an information literacy checklist] Tsukyusidokyoshitu wo riyosuru jido niokeru jyohokatsuyonouryoku no tokucho: Jyohokatsuyonoryoku checklist no sakusei to chosa wo toshite (in Japanese). Bulletin of Miyagi University of Education Graduate School of Teacher Education, 3 , 147–156.

Leshchenko, M., Tymchuk, L., & Tokaruk, L. (2020). Digital narratives in training inclusive education professionals in Ukraine. In J. Głodkowska (Ed.), Inclusive education: Unity in diversity (pp. 254–270). Akademii Pedagogiki Specjalne.

Liang, C., Toyokawa, Y., Majumdar, R., Horikoshi, I., & Ogata, H. (2023). Group formation based on reading annotation data: system innovation and classroom practice . Journal of Computers in Education , 1–29.

Margetts, H., & Dorobantu, C. (2019). Rethink government with AI. Nature, 568 (7751), 163–165.