Suggestions or feedback?

MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Machine learning

- Social justice

- Black holes

- Classes and programs

Departments

- Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Brain and Cognitive Sciences

- Architecture

- Political Science

- Mechanical Engineering

Centers, Labs, & Programs

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL)

- Picower Institute for Learning and Memory

- Lincoln Laboratory

- School of Architecture + Planning

- School of Engineering

- School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

- Sloan School of Management

- School of Science

- MIT Schwarzman College of Computing

The power of economics to explain and shape the world

Press contact :.

Previous image Next image

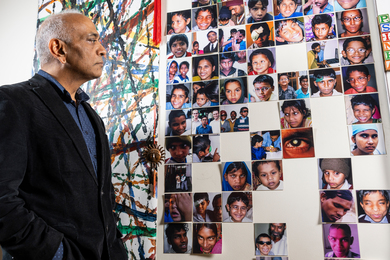

Nobel Prize-winning economist Esther Duflo sympathizes with students who have no interest in her field. She was such a student herself — until an undergraduate research post gave her the chance to learn first-hand that economists address many of the major issues facing human and planetary well-being. “Most people have a wrong view of what economics is. They just see economists on television discussing what’s going to happen to the stock market,” says Duflo, the Abdul Latif Jameel Professor of Poverty Alleviation and Development Economics. “But what people do in the field is very broad. Economists grapple with the real world and with the complexity that goes with it.”

That’s why this year Duflo has teamed up with Professor Abhijit Banerjee to offer 14.009 (Economics and Society’s Greatest Problems), a first-year discovery subject — a class type designed to give undergraduates a low-pressure, high-impact way to explore a field. In this case, they are exploring the range of issues that economists engage with every day: the economic dimensions of climate change, international trade, racism, justice, education, poverty, health care, social preferences, and economic growth are just a few of the topics the class covers. “We think it’s pretty important that the first exposure to economics is via issues,” Duflo says. “If you first get exposed to economics via models, these models necessarily have to be very simplified, and then students get the idea that economics is a simplistic view of the world that can’t explain much.” Arguably, Duflo and Banerjee have been disproving that view throughout their careers. In 2003, the pair founded MIT’s Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab, a leading antipoverty research network that provides scientific evidence on what methods actually work to alleviate poverty — which enables governments and nongovernmental organizations to implement truly effective programs and social policies. And, in 2019 they won the Nobel Prize in economics (together with Michael Kremer of the University of Chicago) for their innovative work applying laboratory-style randomized, controlled trials to research a wide range of topics implicated in global poverty. “Super cool”

First-year Jean Billa, one of the students in 14.009, says, “Economics isn’t just about how money flows, but about how people react to certain events. That was an interesting discovery for me.”

It’s also precisely the lesson Banerjee and Duflo hoped students would take away from 14.009, a class that centers on weekly in-person discussions of the professors’ recorded lectures — many of which align with chapters in Banerjee and Duflo’s book “Good Economics for Hard Times” (Public Affairs, 2019). Classes typically start with a poll in which the roughly 100 enrolled students can register their views on that week’s topic. Then, students get to discuss the issue, says senior Dina Atia, teaching assistant for the class. Noting that she finds it “super cool” that Nobelists are teaching MIT’s first-year students, Atia points out that both Duflo and Banerjee have also made themselves available to chat with students after class. “They’re definitely extending themselves,” she says. “We want the students to get excited about economics so they want to know more,” says Banerjee, the Ford Foundation International Professor of Economics, “because this is a field that can help us address some of the biggest problems society faces.” Using natural experiments to test theories

Early in the term, for example, the topic was migration. In the lecture, Duflo points out that migration policies are often impacted by the fear that unskilled migrants will overwhelm a region, taking jobs from residents and demanding social services. Yet, migrant flows in normal years represent just 3 percent of the world population. “There is no flood. There is no vast movement of migrants,” she says. Duflo then explains that economists were able to learn a lot about migration thanks to a “natural experiment,” the Mariel boat lift. This 1980 event brought roughly 125,000 unskilled Cubans to Florida over a matter a months, enabling economists to study the impacts of a sudden wave of migration. Duflo says a look at real wages before and after the migration showed no significant impacts. “It was interesting to see that most theories about immigrants were not justified,” Billa says. “That was a real-life situation, and the results showed that even a massive wave of immigration didn’t change work in the city [Miami].”

Question assumptions, find the facts in data Since this is a broad survey course, there is always more to unpack. The goal, faculty say, is simply to help students understand the power of economics to explain and shape the world. “We are going so fast from topic to topic, I don’t expect them to retain all the information,” Duflo says. Instead, students are expected to gain an appreciation for a way of thinking. “Economics is about questioning everything — questioning assumptions you don’t even know are assumptions and being sophisticated about looking at data to uncover the facts.” To add impact, Duflo says she and Banerjee tie lessons to current events and dive more deeply into a few economic studies. One class, for example, focused on the unequal burden the Covid-19 pandemic has placed on different demographic groups and referenced research by Harvard University professor Marcella Alsan, who won a MacArthur Fellowship this fall for her work studying the impact of racism on health disparities.

Duflo also revealed that at the beginning of the pandemic, she suspected that mistrust of the health-care system could prevent Black Americans from taking certain measures to protect themselves from the virus. What she discovered when she researched the topic, however, was that political considerations outweighed racial influences as a predictor of behavior. “The lesson for you is, it’s good to question your assumptions,” she told the class. “Students should ideally understand, by the end of class, why it’s important to ask questions and what they can teach us about the effectiveness of policy and economic theory,” Banerjee says. “We want people to discover the range of economics and to understand how economists look at problems.”

Story by MIT SHASS Communications Editorial and design director: Emily Hiestand Senior writer: Kathryn O'Neill

Share this news article on:

Press mentions.

Prof. Esther Duflo will present her research on poverty reduction and her “proposal for a global minimum tax on billionaires and increased corporate levies to G-20 finance chiefs,” reports Andrew Rosati for Bloomberg. “The plan calls for redistributing the revenues to low- and middle-income nations to compensate for lives lost due to a warming planet,” writes Rosati. “It also adds to growing calls to raise taxes on the world’s wealthiest to help its most needy.”

Previous item Next item

Related Links

- Class 14.009 (Economics and Society’s Greatest Problems)

- Esther Duflo

- Abhijit Banerjee

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab

- Department of Economics

- Video: "Lighting the Path"

Related Topics

- Education, teaching, academics

- Climate change

- Immigration

- Health care

- School of Humanities Arts and Social Sciences

Related Articles

Popular new major blends technical skills and human-centered applications

Report: Economics drives migration from Central America to the U.S.

MIT economists Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee win Nobel Prize

More mit news.

Understanding why autism symptoms sometimes improve amid fever

Read full story →

School of Engineering welcomes new faculty

Study explains why the brain can robustly recognize images, even without color

Turning up the heat on next-generation semiconductors

Sarah Millholland receives 2024 Vera Rubin Early Career Award

A community collaboration for progress

- More news on MIT News homepage →

Massachusetts Institute of Technology 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA, USA

- Map (opens in new window)

- Events (opens in new window)

- People (opens in new window)

- Careers (opens in new window)

- Accessibility

- Social Media Hub

- MIT on Facebook

- MIT on YouTube

- MIT on Instagram

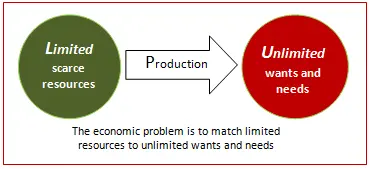

The Economic Problem

All societies face the economic problem , which is the problem of how to make the best use of limited, or scarce, resources. The economic problem exists because, although the needs and wants of people are endless, the resources available to satisfy needs and wants are limited.

Limited resources

Resources are limited in two essential ways:

- Limited in physical quantity , as in the case of land, which has a finite quantity.

- Limited in use , as in the case of labour and machinery, which can only be used for one purpose at any one time.

Choice and opportunity cost

Choice and opportunity cost are two fundamental concepts in economics. Given that resources are limited, producers and consumers have to make choices between competing alternatives. Individuals must choose how best to use their skill and effort, firms must choose how best to use their workers and machinery, and governments must choose how best to use taxpayer’s money.

Making an economic choice creates a sacrifice because alternatives must be given up. Making a choice results in the loss of benefit that an alternative would have provided. For example, if an individual has £10 to spend, and if books are £10 each and downloaded music tracks are £1 each, buying a book means the loss of the benefit that would have been gained from the 10 downloaded tracks. Similarly, land and other resources, which have been used to build a school could have been used to build a factory. The loss of the next best option represents the real sacrifice and is referred to as opportunity cost . The opportunity cost of choosing the school is the loss of the factory, and what could have been produced.

It is necessary to appreciate that opportunity cost relates to the loss of the next best alternative, and not just any alternative. The true cost of any decision is always the closest option not chosen.

Samuelson’s three questions

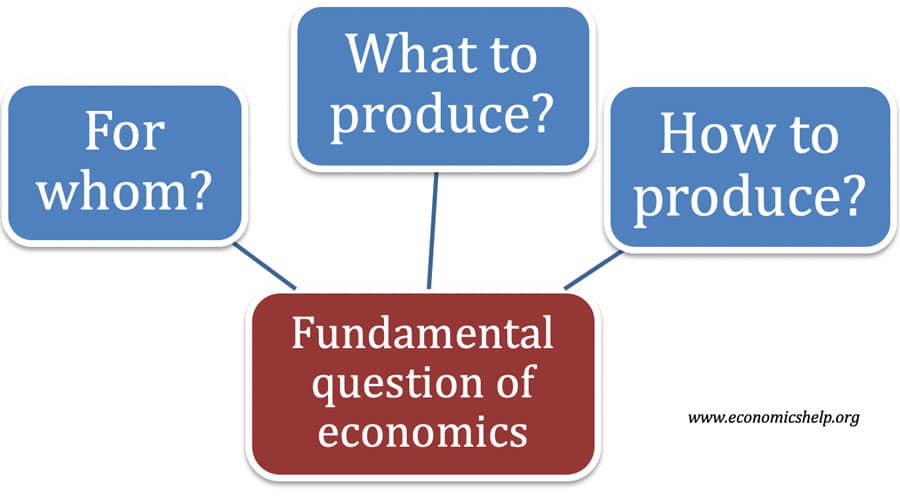

America’s first Nobel Prize winner for economics, the late Paul Samuelson , is often credited with providing the first clear and simple explanation of the economic problem – namely, that in order to solve the economic problem societies must endeavour to answer three basic questions – What to produce? How to produce? And, For whom to produce?

What to produce?

Societies have to decide the best combination of goods and services to meet their varied wants and needs. Societies must decide what quantities of different resources should be allocated to these goods and services.

How to produce?

Societies also have to decide the best combination of factors to create the desired output of goods and services. For example, precisely how much land, labour, and capital should be used to produce consumer goods such as computers and motor cars?

For whom to produce?

Finally, all societies need to decide who will benefit from the output from its economic activity, and how much they will get. This is often called the problem of distribution. Different societies may develop different ways to answer these questions.

A free good is one that is so abundant that its consumption does not deny anyone else the benefit of consuming the good. In this case, there is no opportunity cost associated with consumption or production, and the good does not command a price. Air is often cited as a free good, as breathing it does not reduce the amount available to someone else.

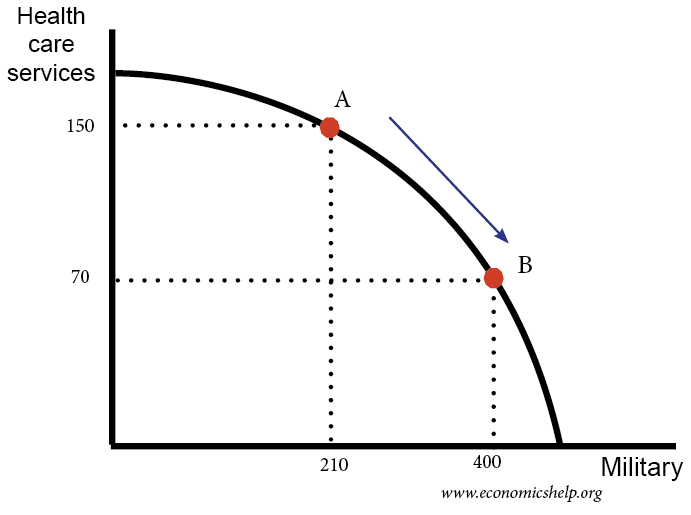

Production Possibility Frontiers

1.3 How Economists Use Theories and Models to Understand Economic Issues

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Interpret a circular flow diagram

- Explain the importance of economic theories and models

- Describe goods and services markets and labor markets

John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946), one of the greatest economists of the twentieth century, pointed out that economics is not just a subject area but also a way of thinking. Keynes ( Figure 1.6 ) famously wrote in the introduction to a fellow economist’s book: “[Economics] is a method rather than a doctrine, an apparatus of the mind, a technique of thinking, which helps its possessor to draw correct conclusions.” In other words, economics teaches you how to think, not what to think.

Watch this video about John Maynard Keynes and his influence on economics.

Economists see the world through a different lens than anthropologists, biologists, classicists, or practitioners of any other discipline. They analyze issues and problems using economic theories that are based on particular assumptions about human behavior. These assumptions tend to be different than the assumptions an anthropologist or psychologist might use. A theory is a simplified representation of how two or more variables interact with each other. The purpose of a theory is to take a complex, real-world issue and simplify it down to its essentials. If done well, this enables the analyst to understand the issue and any problems around it. A good theory is simple enough to understand, while complex enough to capture the key features of the object or situation you are studying.

Sometimes economists use the term model instead of theory. Strictly speaking, a theory is a more abstract representation, while a model is a more applied or empirical representation. We use models to test theories, but for this course we will use the terms interchangeably.

For example, an architect who is planning a major office building will often build a physical model that sits on a tabletop to show how the entire city block will look after the new building is constructed. Companies often build models of their new products, which are more rough and unfinished than the final product, but can still demonstrate how the new product will work.

A good model to start with in economics is the circular flow diagram ( Figure 1.7 ). It pictures the economy as consisting of two groups—households and firms—that interact in two markets: the goods and services market in which firms sell and households buy and the labor market in which households sell labor to business firms or other employees.

Firms produce and sell goods and services to households in the market for goods and services (or product market). Arrow “A” indicates this. Households pay for goods and services, which becomes the revenues to firms. Arrow “B” indicates this. Arrows A and B represent the two sides of the product market. Where do households obtain the income to buy goods and services? They provide the labor and other resources (e.g., land, capital, raw materials) firms need to produce goods and services in the market for inputs (or factors of production). Arrow “C” indicates this. In return, firms pay for the inputs (or resources) they use in the form of wages and other factor payments. Arrow “D” indicates this. Arrows “C” and “D” represent the two sides of the factor market.

Of course, in the real world, there are many different markets for goods and services and markets for many different types of labor. The circular flow diagram simplifies this to make the picture easier to grasp. In the diagram, firms produce goods and services, which they sell to households in return for revenues. The outer circle shows this, and represents the two sides of the product market (for example, the market for goods and services) in which households demand and firms supply. Households sell their labor as workers to firms in return for wages, salaries, and benefits. The inner circle shows this and represents the two sides of the labor market in which households supply and firms demand.

This version of the circular flow model is stripped down to the essentials, but it has enough features to explain how the product and labor markets work in the economy. We could easily add details to this basic model if we wanted to introduce more real-world elements, like financial markets, governments, and interactions with the rest of the globe (imports and exports).

Economists carry a set of theories in their heads like a carpenter carries around a toolkit. When they see an economic issue or problem, they go through the theories they know to see if they can find one that fits. Then they use the theory to derive insights about the issue or problem. Economists express theories as diagrams, graphs, or even as mathematical equations. (Do not worry. In this course, we will mostly use graphs.) Economists do not figure out the answer to the problem first and then draw the graph to illustrate. Rather, they use the graph of the theory to help them figure out the answer. Although at the introductory level, you can sometimes figure out the right answer without applying a model, if you keep studying economics, before too long you will run into issues and problems that you will need to graph to solve. We explain both micro and macroeconomics in terms of theories and models. The most well-known theories are probably those of supply and demand, but you will learn a number of others.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Steven A. Greenlaw, David Shapiro, Daniel MacDonald

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Principles of Economics 3e

- Publication date: Dec 14, 2022

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/1-3-how-economists-use-theories-and-models-to-understand-economic-issues

© Jan 23, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

A business journal from the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania

How to Manage the Top Five Global Economic Challenges

November 1, 2017 • 14 min read.

The world’s economic system faces five tough challenges. Multilateral institutions offer the best hope of managing them, notes this opinion piece by the secretary general of the European Stability Mechanism.

- Public Policy

The world’s economic system has been through a lot in recent years — from the challenge of the financial crisis to income inequality, the pressures of immigration, changing technologies and geographic shifts in production, to name a few. In this opinion piece, Kalin Anev Janse, secretary general and a member of the management board of the European Stability Mechanism (the eurozone’s lender of last resort), considers five major challenges and why international organizations offer the best hope for managing them.

A year ago, we were shaken by geopolitical shifts with unpredictable ripple effects. The situation looks no more stable today. The Brexit vote and the U.S. presidential election outcome signal dramatic changes in cooperation globally and a push for more protectionism. In practice, these votes called into question the multilateral institutions and international collaboration among countries that embody that cooperation. In autumn 2017, we gathered together a group of senior officials from the 13 largest international organizations to try to crack these problems.

What happened?

Exactly 10 years ago, in 2007, the first signs of the Great Recession emerged. By 2008, the U.S.-led subprime crisis evolved into a global financial crisis. By 2010, Europe had become engulfed in its own crisis, throwing financial markets into turmoil and several sovereigns into a downward spiral of debt and banking crises.

Despite the current ongoing recovery, and the successful economic rebound both in North America and Europe, worrying trends became apparent in 2016. Some major players demonstrated a reduced commitment to multilateral cooperation, criticism of open and free trade, and fading interest in climate change. This new landscape increased uncertainty and poses a threat to more buoyant macroeconomic and financial fundamentals. It also puts a strain on relations between major players internationally, as well as between citizens domestically. In countries like the U.S. and the UK, it abruptly split societies in half and threatened a reverse of seven decades of international cooperation.

All these elements are putting pressure on international organizations as well. International organizations are increasingly called upon to redefine their role to ensure that their programs and activities are still relevant in this evolving political and macroeconomic landscape. They are also pushed to show how they add value to citizens’ lives. At the same time, they need to maintain lean structures to minimize the burden on taxpayers, and enhance efficiency and effectiveness of their activities. So, what has changed?

Five Major Shifts that Rocked Our World

There are five trend shifts globally that by their nature call for international cooperation, but they have been underestimated, undervalued and under-addressed both nationally and internationally. The results shook our world with an unforeseeable force.

1. Growing Income Inequality

People have an age-old tendency to compare themselves to their neighbors, especially when it comes to wealth. We are less concerned about our absolute level of wealth, but look more at what we have and own in relative terms to the people around us. Global private wealth reached a record $166.5 trillion in 2016, an increase of 5.3% over the previous year, according to a report by the Boston Consulting Group (BCG). 1 In 2015, the increase was 4.4%. Faster economic growth and stock price performance mainly drove the rapid increase.

But this growth is not spread equally. Private wealth in Asia-Pacific is likely to surpass that of Western Europe by as early as the end of this year, BCG’s analysis shows. This could be an economic shock for many citizens of traditional western powerhouses. Such changes need to be watched and managed carefully as they tilt economic and political power. British geographer and politician Sir Halford Mackinder used to say: “Unequal growth among nations tends to produce a hegemonic world war about every 100 years.” We can only hope he is wrong.

“Just eight men now own the same wealth as 3.6 billion people globally, more than half of humanity….”

Inequality is getting ever worse. A tipping point was reached in 2015, when the richest 1% in the world owned as much as the rest of humanity. This trend has continued and further accelerated. Just eight men now own the same wealth as 3.6 billion people globally, more than half of humanity, according to a January 2017 Oxfam report. Income inequality is on the rise as the affluent continue to accumulate wealth, often at the expense of the poorer.

Richard Reeves points out in his book Dream Hoarders , that we shouldn’t only be worried about the top 1% or 0.01%. More importantly, in some countries, like the U.S., there is a widening gap in society between the upper middle class and everyone else. (Reeves defines the upper middle class as those whose incomes are in the top 20% of U.S. society.) These growing disparities are reflected in family structure, neighborhoods, attitudes and lifestyle. The top income earners are becoming more effective at passing on their status to their children, thus reducing overall social mobility and increasing social divisions, along class as well as income lines.

And all this has an interesting twist: the inequality paradox. Despite the progress in reducing global poverty and reduction of inequality among countries since 1980s, income inequality within countries has been rising. These days, almost one-third of global inequality is attributable to in-country inequality (figure 1), making clear why many voters across the western world feel as they do.

2. Technology Driving Change in Jobs

How disruptive will the effect of globalization and technological advances be on labor markets? That is a key question today. Over the last three decades, advanced economies have seen labor-intensive sector jobs move to emerging markets. In other cases, new technologies have made certain occupations obsolete. UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development) released a policy brief last year that said robots could take away two-thirds of jobs in developing countries.

We see some of these shifts already. Today’s five largest global companies are: Apple, Alphabet (Google), Microsoft, Amazon, and Facebook. They employ around 720,000 people. A decade ago, the big five were completely different: Petrochina, Exxon Mobile, General Electric, China Mobile, and Bank of China. They employed around 1.3 million people. What a decade can do! Today’s five biggest companies are all technology companies. Their market capitalization is 30% higher than that of the top five a decade ago; they achieve that with a whopping 44% less staff (figure 2). This has a large impact on labor markets and jobs.

Does this alter work preferences? Yes, and this is best assessed by looking at the two most dynamic groups of (future) job seekers: millennials and today’s teenagers. They feel that they are receiving conflicting messages from employers and career advisors: On the one hand, they are told that robots are bound to replace future jobs; on the other, they need technical skills to compete in the job market.

Caught in this conundrum, they are trying to create new types of jobs, rather than going for traditional ones such as banking, finance, or accounting. They dream of becoming YouTube stars, famous videogame vloggers, or Instagram travel bloggers who are paid by sponsors to visit hotels and restaurants around the world and generate sufficient number of likes. New creative companies pop up even in professions that well-educated young people ignored for many decades. Old merchants’ jobs have been revived, from organic bakers to cool rural wine-makers and hipster butchers.

“Forty-five percent of the global working age population is underutilized, either unemployed or underemployed.”

I am less concerned about the imaginative young generation; they will find their way. It is the group of middle-to-older, middle-to-lower-skilled workers where issues might arise. A recent McKinsey estimate shows that 45% of the global working age population is underutilized, either unemployed or underemployed. Unless there is a redirection of investment into labor-intensive productive sectors and retraining, the desired job creation may not happen, fueling unhappiness, unrest and populism.

3. Rising Protectionism

G20 countries have become more protectionist. The total number of discriminatory protectionist measures implemented by G20 countries has increased over the past five years (figure 3). The main driver has been the U.S. According to the Global Trade Alert report, had the United States been excluded, the total number of protectionist policy instruments imposed by the G20 would have been lower in 2017 than in 2016. The U.S. has implemented the most protectionist and trade restrictive measures of its peer group, the European Union the least (figure 4). This sounds counter-intuitive for the country that prides itself as an open economy, but it seems that it is Europe that is championing trade barrier reductions and the avoidance of protectionist measures.

“The recent refugee crisis in Syria and the resulting arrival of more than one million migrants in 2015-2016 in Germany presented a formidable challenge to political and social stability.”

4. Increasing Migration

The recent refugee crisis in Syria and the resulting arrival of more than one million migrants in 2015-2016 in Germany presented a formidable challenge to political and social stability. In addition to tougher checks on the EU’s external borders, and a controversial refugee pact with Turkey, the EU is investing more in the migrants’ countries of origin. The refugees from Syria have been fleeing a brutal civil war. They are escaping violence, as many also are from Iraq and Afghanistan, and, in such cases, humanitarian reasons should always prevail over other considerations. Wars, climate change, and broader economic and social inequalities are the root causes of migration flows. While these increases in migration are all easy to understand, they nonetheless cause issues in the countries of arrival: integration problems, absorption limits and skills-mismatches.

5. Growing Influence of Social Media and the Post-truth World

Social media pose the final major challenge to international organizations. According to a recent analysis by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 51% of people with online access use social media as a news source. Social media is the primary source for news for 44% of smartphone users in the U.S. and 38% in the U.K. (figure 7). Coupled with the proliferation of so-called fake news, which became so prominent in last year’s U.S. elections, as well as social media’s favoring of ever shorter and catchier messages, it is no wonder that many observers are saying we are living in a post-truth world.

“In the November 2016 U.S. elections … top fake election news stories generated more total engagement on Facebook than the top election stories from the 19 major news outlets combined.”

A recent BuzzFeed analysis of social media traffic in the run-up to the November 2016 U.S. elections found that top fake election news stories generated more total engagement on Facebook than the top election stories from the 19 major news outlets combined (figure 8). These trends represent serious tests on many fronts, including combating terrorism and securing the proper functioning of democratic institutions. Fear, anger and despair enlist recruits for terrorism. They also create a more polarized social climate and the rise of extremism, as we were recently reminded by the tragic events in Charlottesville in the U.S. or by some half a dozen car terror attacks in Europe this year.

Is Peaceful International Collaboration Ending?

Despite these daunting challenges, there are also reasons to be optimistic. At the European level, political leaders have regained faith in sticking together to address global and societal realities. At least two factors have been crucial to the recovery of confidence in the European project. First, the EU is delivering economically. The euro area and the broader EU recently recorded their highest ever employment levels. Investment is up, and growth is projected to be on a par with, if not higher than, growth in the U.S. this year.

Second, despite growing populism, Europe’s citizens have confidently stood for democracy, open borders, economic reforms, and more Europe. The results of the elections in the Netherlands and France bore witness to this positive trend among European societies. In spite of the recent electoral gains of an extreme right-wing party in Germany, the election outcome was again clearly pro-European. The continent appears in better shape today than it did after Brexit one year ago.

In my view, Europe can offer lessons in regional integration that are relevant for other parts of the world. Among others, my institution – the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) – is a product of European cooperation in response to the financial and economic crisis. As the largest and most active regional financing arrangement, the ESM works closely with its peers in other regions of the world.

Beyond Europe, the continued rise of Asian economies, as well as those in Latin America, present new opportunities for strengthening international cooperation in many of the areas I have mentioned, including finance, infrastructure, energy, education, climate change and others.

So what does this all mean for public international organizations? These organizations act as agents of their shareholders (i.e., member states) and are called upon to help address difficult challenges. Some international organizations that raise funds in the capital markets for their operations, like mine, also have to be attuned to the concerns of their investors. In general, international organizations also dispose of soft power, derived from funds and moral suasion based on extensive experience, as well as the values and norms that they adhere to and champion. Obviously, international organizations also need a broad-based buy-in from the public at large, in particular in times of change and uncertainty. All this needs to be done while maintaining lean organizational structures to keep the costs for taxpayers low.

In our autumn 2017 session of the group of senior officials from international organizations, we pushed ourselves to find modern ways to explain better what we do and what we can offer when it comes to tackling these challenges. Among other matters, we discussed using more social media and empowering our talented and hard-working staff to share their personal stories, because it can best demonstrate the tremendous impact of their work.

“Multilateral institutions and international organizations have proven to be the most effective way to solve complex global problems in a peaceful and constructive way.”

We also need to make our institutions less bureaucratic and truly “lean, clean and green,” not only because it is more efficient but also because it can help us attract more talent among the millennial generation. And finally, we need to work even harder to better cooperate with each other and to ensure the missions and activities of our institutions make a difference, because nothing can demonstrate the value of multilateralism better than international organizations delivering effective and sustainable solutions to the most pressing global challenges.

But at the end there is only one question that matters: Is there any alternative way to making our world with more than 7 billion people work? Not at this stage – multilateral institutions and international organizations have proven to be the most effective way to solve complex global problems in a peaceful and constructive way. All other alternatives involve far more violence, aggression and isolation. If we look through the eyes of our children, it is much wiser to collaborate and work together rather than fight (digitally) with our global neighbors, whether close by or far away.

(This article reflects the personal opinion of Kalin Anev Janse. It is adapted from a speech he gave to senior officials from the 13 largest international organizations, including the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.)

[1] “Global Wealth 2017: Transforming the Client Experience,” published in June 2017.

More From Knowledge at Wharton

How High-skilled Immigration Creates Jobs and Drives Innovation

The U.S. Housing Market Has Homeowners Stuck | Lu Liu

What Will Happen to the Fed’s Independence if Trump Is Reelected?

Looking for more insights.

Sign up to stay informed about our latest article releases.

- Work & Careers

- Life & Arts

Become an FT subscriber

Try unlimited access Only $1 for 4 weeks

Then $75 per month. Complete digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Cancel anytime during your trial.

- Global news & analysis

- Expert opinion

- Special features

- FirstFT newsletter

- Videos & Podcasts

- Android & iOS app

- FT Edit app

- 10 gift articles per month

Explore more offers.

Standard digital.

- FT Digital Edition

Premium Digital

Print + premium digital, ft professional, weekend print + standard digital, weekend print + premium digital.

Essential digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

- Global news & analysis

- Exclusive FT analysis

- FT App on Android & iOS

- FirstFT: the day's biggest stories

- 20+ curated newsletters

- Follow topics & set alerts with myFT

- FT Videos & Podcasts

- 20 monthly gift articles to share

- Lex: FT's flagship investment column

- 15+ Premium newsletters by leading experts

- FT Digital Edition: our digitised print edition

- Weekday Print Edition

- Videos & Podcasts

- Premium newsletters

- 10 additional gift articles per month

- FT Weekend Print delivery

- Everything in Standard Digital

- Everything in Premium Digital

Complete digital access to quality FT journalism with expert analysis from industry leaders. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

- 10 monthly gift articles to share

- Everything in Print

- Make and share highlights

- FT Workspace

- Markets data widget

- Subscription Manager

- Workflow integrations

- Occasional readers go free

- Volume discount

Terms & Conditions apply

Explore our full range of subscriptions.

Why the ft.

See why over a million readers pay to read the Financial Times.

International Edition

- Marketplace

- Marketplace Morning Report

- Marketplace Tech

- Make Me Smart

- This is Uncomfortable

- The Uncertain Hour

- How We Survive

- Financially Inclined

- Million Bazillion

- Marketplace Minute®

- Corner Office from Marketplace

- Latest Stories

- Collections

- Smart Speaker Skills

- Corrections

- Ethics Policy

- Submissions

- Individuals

- Corporate Sponsorship

- Foundations

How to problem-solve through economic issues

Share Now on:

- https://www.marketplace.org/2021/01/01/how-to-problem-solve-through-economic-issues/ COPY THE LINK

HTML EMBED:

Identifying problems, especially economic issues, can seem obvious. What’s harder is figuring out the constraints that prevent them from being solved. But there are ways to arrive at solutions.

It’s the subject of a new book, “The Economic Superorganism” by Carey King, a research scientist and assistant director of the Energy Institute at the University of Texas at Austin. He recently spoke with Marketplace’s Andy Uhler.

The following is an edited transcript of Uhler and King’s conversation.

Andy Uhler: So when we think of the traditional economic model of the energy industry, what does that model or what do those models get wrong?

Carey King: Well, my narratives in my book are a little bit more about macroeconomic narratives, or how do people approach what the economy is and how does it grow in general? And so I simplify into the techno optimistic narrative of infinite growth and substitutability of technologies. On the opposite end of that spectrum is technorealism. Which is to say, well, there are constraints in the world, there are things like physical laws that we understand. And there are constraints of time. And we need to take these into account to actually understand what’s possible and how the economy evolves. So those are really the two narratives and they get applied to the energy industry. And by applying them, I would say, less accurate narratives to how the energy system interacts with the broader economy. I think we get answers from reports and analyses that are less accurate than we can do.

Uhler: Because you’re talking about using the data to then ask different questions and also sort of come up with different narratives and ultimately, different answers. Right?

King: Right. So everybody’s kind of coming up with their own narratives. In my book, the narratives are in some sense, strawmen, but they’re set up so that I can then go into detail about well, here’s a coherent way to think about what the economy is. And one of those ways is to say that the economy is an organism, like living organisms that need energy and resources to grow. It needs energy and resource consumption to maintain itself. And it has to distribute these resources internally. So by taking these kinds of physical aspects into account, we have a better interpretation for the economic patterns that we see.

Andy Uhler: I’m curious sort of how your model fits with this new shift in renewable energy. And in sort of the way that we think about zero carbon as well, how does it fit?

King: So a lot of the shift of the energy system and other industries in general is to lower marginal cost in general. So you might have higher capital costs, which we take into account or when we think about things like solar and photovoltaic systems and batteries, they have a high upfront capital cost, lower marginal cost. And this is essentially the same kind of growth pattern we see in biology and ecosystems in the sense that the last bits of growth of an animal consume less energy than the previous set. So it’s a similar pattern that we might see in ecosystems.

Stories You Might Like

OPEC has to decide whether it will continue to curb oil output

How will the world respond to the European Union’s proposed carbon border tax?

David Brooks on what’s responsible for America’s class divisions

Warren Buffett’s Berkshire acquires natural gas assets from Dominion Energy

What we get wrong about the energy grid

There’s a new website publishing news stories in Texas. It’s run by Chevron.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on . For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.

Latest Episodes From Our Shows

High interest rates have frozen the real estate market. When will it thaw?

First GE, now DuPont. Corporate deconglomeration is having a moment.

Now that pandemic SNAP benefits have ended, many scramble for food

Is the passive investing boom bad news?

Solution to the Basic Economic Problems: Capitalistic, Socialistic and Mixed Economy

Solution to the Basic Economic Problems: Capitalistic, Socialistic and Mixed Economy!

Uneven distribution of natural resources, lack of human specialization and technological advancement etc., hinders the production of goods and services in an economy. Every economy has to face the problems of what to produce, how to produce and for whom to produce. More or less, all the economies use two important methods to solve these basic problems.

These methods are:

(a) Free price mechanism and

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(b) Controlled price system or State intervention.

Price mechanism is defined as a system of guiding and coordinating the decisions of every individual unit within an economy through the price determined with the help of the free play of market forces of demand and supply. Such system is free from state intervention.

Price of goods and services are determined when quantity demanded becomes equal to the quantity supplied. Price mechanism facilitates determination of resource allocation, determination of factor incomes, level of savings, consumption and production. Price mechanism basically takes place in a capitalistic economy.

On the other hand, Controlled price mechanism is defined as a system of state interventio n of administering or fixing the prices of the goods and services. In a socialist economy, the government plays a vital role in determining the price of the goods and services. The government may introduce ‘ceiling price’ or ‘floor price’ policy to regulate prices.

However, how a capitalist, a socialist and a mixed economic system solve their basic problems is given below:

1. Solution to Basic Problems in a Capitalistic Economy:

Under capitalistic economy, allocation of various resources takes place with the help of market mechanism. Price of various goods and services including the price of factors of production are determined with help of the forces of demand and supply. Free price mechanism helps producers to decide what to produce.

The goods which are more in demand and on which consumers can afford to spend more, are produced in larger quantity than those goods or services which have lower demand. The price of various factors of production including technology helps to decide production techniques or methods of production. Rational producer intends to use those factors or techniques which has relatively lower price in the market.

Factor earnings received by the employers of factors of production decides spending capacity of the people. This helps producers to identify the consumers for whom goods could be produced in larger or smaller quantities. Price mechanism works well only if competition exists and natural flow of demand and supply of goods is not disturbed artificially.

2. Solution to Basic Problems in a Socialistic Economy:

Under socialistic economy, the government plays an important role in decision making. The government undertakes to plan, control and regulate all the major economic activities to solve the basic economic problems. All the major economic policies are formulated and implemented by the Central Planning Authority.

In India, Planning Commission was entrusted with this task of planning. The Planning Commission of India has now been replaced by another central authority NITI Ayog (National Institution for Transforming India). Therefore, the central planning authority takes the decisions to overcome the economic problems of what to produce, how to produce and for whom to produce.

The central planning authority decides the nature of goods and services to be produced as per available resources and the priority of the country. The allocation of resources is made in greater volume for those goods which are essential for the nation. The state’s main objectives are growth, equality and price stability. The government implements fiscal policies such as taxation policy, expenditure policy, public debt policy or policy on deficit financing in order to achieve the above objectives.

The methods of production or production techniques are also determined or selected by the central planning authority. The central planning authority decides whether labor intensive technique or capital intensive technique is to be used for the production. While deciding the appropriate method, social and economic conditions of the economy are taken into consideration.

Under socialistic economy, every government aims to achieve social justice through its actions. All economic resources are owned by the government. People can work for wages which are regulated by the government as per work efficiency. The income earned determines the aggregate demand in an economy. This helps the government in assessing the demand of goods and services by different income groups.

3. Solution to Basic Problems in a Mixed Economy:

Practically, neither capitalistic economy nor socialistic economy exists in totality. Both the economic systems have limitations. Consequently, a new system of economy has emerged as a blend of the above two systems called mixed economy. Therefore, mixed economy is defined as a system of economy where private sectors and public sectors co-exist and work side by side for the welfare of the country.

Under such economies, all economic problems are solved with the help of free price mechanism and controlled price mechanism (economic planning).

Free price mechanism operates within the private sector; hence, prices are allowed to change as per demand and supply of goods. Therefore, private sector can produce goods as per their demand and their price in the market. The government may control and regulate production of the private sector through its monetary policy or fiscal policy.

On the other hand, controlled price mechanism (economic planning) is used for the public sector by the planning authority. The goods and services to be produced in the public sector, hence, are determined by the central planning authority.

Private sector determines the production technique or production method on the basis of factor prices, availability of technology etc. On the other hand, production technique or production method for the public sector is determined by the central planning authority. While determining the production technique for the public sector, national priority, national employment policy and social objectives are major considerations.

Private sector allocates its resources to produce those goods which are demanded by people who command high purchasing power. Although, production by the private sector is sometimes controlled and regulated by the government through various policies such as licensing policy, taxation policy, subsidy etc., the price determined by free price mechanism may go beyond the purchasing power of low or marginal income group.

Therefore, the government may undertake production of certain goods in its hands. The rationing policy is also introduced to provide essential goods at reasonable price to the poor people. The government, thus, ensures social justice by its actions in the mixed economy.

Related Articles:

- Basic Problems of an Economy and Price Mechanism (FAQs)

- Mixed Economy: Meaning, Features and Types of Mixed Economy

- Price Mechanism: in Free, Socialistic and Mixed Economy

- 5 Basic Problems of an Economy (With Diagram)

Live revision! Join us for our free exam revision livestreams Watch now →

Reference Library

Collections

- See what's new

- All Resources

- Student Resources

- Assessment Resources

- Teaching Resources

- CPD Courses

- Livestreams

Study notes, videos, interactive activities and more!

Economics news, insights and enrichment

Currated collections of free resources

Browse resources by topic

- All Economics Resources

Resource Selections

Currated lists of resources

- Study Notes

1.1.3 The Economic Problem (Edexcel)

Last updated 19 Sept 2023

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share by Email

This study note for Edexcel covers the economic problem.

A) The Problem of Scarcity - Unlimited Wants and Finite Resources

1. Introduction to Scarcity

- Scarcity is a fundamental concept in economics.

- It arises from the fact that human wants and needs are virtually limitless, while resources to satisfy them are limited.

2. Key Characteristics of Scarcity

- Limited Resources: Resources like land, labor, capital, and time are limited in supply.

- Unlimited Wants: People desire more goods and services than can be produced with available resources.

3. Implications of Scarcity

- Choices and Trade-offs: Scarcity necessitates making choices and trade-offs due to limited resources.

- Opportunity Cost: Every choice involves an opportunity cost, the value of the next best alternative forgone.

4. Real-World Example

- Example: A government's decision to allocate funds to healthcare may mean fewer resources available for education. The opportunity cost is the educational quality and access that could have been improved with those funds.

B) Distinction Between Renewable and Non-Renewable Resources

1. Renewable Resources

- Renewable resources can be replenished naturally over time.

- They include resources like solar energy, wind energy, forests, and fish stocks.

2. Non-Renewable Resources

- Non-renewable resources cannot be replaced naturally within a human timescale.

- Examples include fossil fuels (coal, oil, natural gas), minerals (e.g., iron, copper), and nuclear fuel.

3. Importance of the Distinction

- Sustainability: Understanding the difference is vital for sustainable resource management.

- Economic Implications: Depletion of non-renewable resources can lead to rising prices and economic challenges.

- Example: Fossil fuels (non-renewable) are finite resources. As they are depleted, the world is increasingly focusing on renewable energy sources like solar and wind power to combat climate change and ensure long-term energy security.

C) The Importance of Opportunity Costs to Economic Agents

1. Opportunity Cost Defined

- Opportunity cost is the value of the next best alternative foregone when a choice is made.

- It represents the true cost of a decision in terms of forgone opportunities.

2. Importance for Consumers

- Consumers make choices about spending money and time.

- Opportunity cost helps them make informed decisions, such as choosing between buying a new phone or saving for a vacation.

3. Importance for Producers

- Producers allocate resources to maximize profits.

- Opportunity cost influences production decisions, like choosing which products to manufacture.

4. Importance for Government

- Governments allocate budgets to various programmes and policies.

- Opportunity cost informs decisions on allocating resources between healthcare, education, defense, and more.

5. Real-World Example

- Example: If a consumer spends $500 on a new smartphone, the opportunity cost might be the vacation they could have taken with that money. For governments, investing in infrastructure instead of defense might mean an opportunity cost in terms of national security.

Understanding scarcity, the distinction between resource types, and the concept of opportunity cost is essential for making informed economic decisions and addressing resource allocation challenges in the real world.

- Economic Problem

- Water Scarcity

- Scarcity bias

- Resource Scarcity

You might also like

Venezuela – fingerprinting as a rationing device..

26th August 2014

The Opportunity Cost of a pair of Apple AirPods

12th September 2016

Behavioural Economics (Quizlet Revision Activity)

Quizzes & Activities

Basic Economic Problem - Revision Video Playlist

Topic Videos

Opportunity Cost - Two Applied Examples

Water nationalisation - should england's water monopolies be nationalised.

16th July 2021

1.1.4 Production Possibility Frontiers (Edexcel A-Level Economics Teaching PowerPoint)

Teaching PowerPoints

Tutor2u Year 12 student competition winner!

29th February 2024

Our subjects

- › Criminology

- › Economics

- › Geography

- › Health & Social Care

- › Psychology

- › Sociology

- › Teaching & learning resources

- › Student revision workshops

- › Online student courses

- › CPD for teachers

- › Livestreams

- › Teaching jobs

Boston House, 214 High Street, Boston Spa, West Yorkshire, LS23 6AD Tel: 01937 848885

- › Contact us

- › Terms of use

- › Privacy & cookies

© 2002-2024 Tutor2u Limited. Company Reg no: 04489574. VAT reg no 816865400.

9 ways to strengthen the global economic response to COVID-19

Governments in developing economies lack the resources to do fiscal stimulus. Image: REUTERS/Thomas Mukoya

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Khalid Abdulla-Janahi

Erik berglof.

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} COVID-19 is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, long-term investing, infrastructure and development.

- We need to find new ways of funding the IMF and World Bank.

- The G20 could make a “whatever-it-takes” statement, promising additional capital if the situation further deteriorates.

- We need to bring together the global financial safety net, the development finance architecture and the private sector to tackle the crisis.

The IMF and the World Bank – the two organizations at the centre of development finance – are organizing their (virtual) Spring Meetings this week. They are doing so at a time when the COVID-19 pandemic is exposing the global financial safety net and the development finance architecture to the most serious shock since both organizations emerged out of the ruins of two world wars and the Great Depression.

Have you read?

This is the effect coronavirus has had on air pollution all across the world, coronavirus has exposed the digital divide like never before.

We urgently need to find new ways of securing funding for these multilateral institutions, including from the private sector, and, in the process, bring them closer together. This will require the same kind of leadership and innovative thinking and institution-building that marked their founding.

The two sides of the COVID-19 crisis – the medical emergency and economic impact – are closely intertwined. Many emerging and developing economies are actually hit first by the economic impact. Falling commodity prices, drops in tourism revenues, reduced remittances from citizens abroad and the rapid outflows of capital are ravaging their economies, even before the virus has taken hold. The economic devastation, in turn, will undermine their capacity to respond to the virus and threatens social and political stability in the medium term

The first responses from the IMF and the World Bank, and the regional development banks, have been powerful and welcome, but the demands on them will only increase as the crisis accelerates in the emerging and developing world. To effectively fight the virus and mitigate its broader impact, these institutions must be allowed to use their existing resources more effectively and ultimately they will need additional resources.

We suggest three reforms each to the global financial safety net, the development architecture and the capacity of the core institutions to crowd in the private and institutional capital.

The global financial safety net, with the IMF at the core, but complemented by a patchy and incomplete system of regional arrangements, mainly in Europe and Asia, is critical in providing liquidity and maintaining financial stability. Yet the current firepower of the IMF is insufficient to deal with the magnitude of this crisis. The IMF is already processing more than 90 requests from countries for emergency financing, and another 50 or so are in the wings. Countries need liquidity to address the medical emergency, but most of all to deal with the economic impact. There have been many ideas proposed for how to strengthen the global financial safety net, several of them discussed in the final report from the G20 Eminent Persons Group on Global Financial Governance (EPG) presented a couple of years ago.

1. Establish liquidity support lines

One such proposal was to establish a liquidity facility to which prequalified countries in need could turn. Prequalification could avoid the stigma associated with applying for support.

2. Give the IMF a role in a network of central bank swap lines

Such liquidity lines could be supplemented by the IMF intermediating support lines from systemic central banks to central banks in well-run emerging economies with liquidity problems.

3. Issue Special Drawing Rights

Proposals 1 and 2 would rely on the IMF’s existing resources and would still not meet the enormous liquidity requirements that will eventually lead to solvency threats in many countries. The most direct way to provide additional capital to the IMF would be to issue additional Special Drawing Rights (SDR), the special currency through which the member states support the IMF. The EPG carefully avoided this proposal, due to the limitations to its mandate, but an SDR issue would both increase firepower and offer a valuable stimulus to the global economy.

The World Bank has responded with a massive effort to help address both the medical and economic emergencies. It has strong expertise in the health and well-functioning cash transfer programmes and local community schemes in a very large number of countries that can be used to reach the most vulnerable, but its resources are also insufficient. As the economic impact from lockdowns and supply disruptions starts to bite, the World Bank’s financing needs will increase dramatically. Most governments in emerging and developing economies lack the resources to do meaningful monetary and fiscal stimulus.

Fortunately, many of the multilateral development banks (MDBs) were recently recapitalized or have free capacity, and can respond in the short term. But on the current trajectory, they will run out of “headroom”, impeding their ability to respond. Added to this, the quality of their portfolios will deteriorate as the economic impact from the pandemic works its way through the system. There are already signs that the costs of borrowing are going up for some of the weaker institutions. At some point, the rating agencies will look at their portfolios and the creditworthiness of their shareholders.

4. Establish liquidity backstop for MDBs

One innovation that could help the MDBs increase their lending capacity would be to provide them with a so-called liquidity backstop. Unlike commercial banks most multilateral development banks lack automatic access to support from governments in the case of a liquidity shortfall. Rating agencies would upgrade them if a group of central banks came together, possibly intermediated through the IMF, and provided a liquidity facility. The European Investment Bank has access to such support from the ECB.

5. Introduce new form of equity capital

A related proposal would be to provide the development banks with a new form of capital. Today they have two types of capital – paid-in capital which counts as equity on the banks’ balance sheets; and callable capital which can only be used when a development bank is closed down to pay off bondholders. It would be useful to have an intermediate form of capital that could be called in when banks are exposed to a shock like the current one. Again rating agencies would recognise such support in their ratings. The European Stability Mechanism has this type of contingent capital.

6. Make a G20 “whatever-it-takes” statement

Even if these two ideas could not be realized at the moment, the G20 could, with support from other key shareholders, make a “whatever-it-takes” statement, promising that additional capital would be forthcoming if the situation further deteriorated. While such a statement might not immediately impress rating agencies, it could inspire innovation and big ideas inside and outside the MDBs. It would also reassure governments in the worst-hit emerging and developing economies that resources will be forthcoming.

Responding to the COVID-19 pandemic requires global cooperation among governments, international organizations and the business community , which is at the centre of the World Economic Forum’s mission as the International Organization for Public-Private Cooperation.

Since its launch on 11 March, the Forum’s COVID Action Platform has brought together 1,667 stakeholders from 1,106 businesses and organizations to mitigate the risk and impact of the unprecedented global health emergency that is COVID-19.

The platform is created with the support of the World Health Organization and is open to all businesses and industry groups, as well as other stakeholders, aiming to integrate and inform joint action.

As an organization, the Forum has a track record of supporting efforts to contain epidemics. In 2017, at our Annual Meeting, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) was launched – bringing together experts from government, business, health, academia and civil society to accelerate the development of vaccines. CEPI is currently supporting the race to develop a vaccine against this strand of the coronavirus.

Yet, the governments behind both the IMF and the development banks are also weakened by the crisis and domestic needs will be gigantic. New ways must be found to crowd in private and institutional capital. The EPG Report pointed to a number of steps which could be taken, all on a much greater scale than today.

7. Allow the IMF to borrow from markets

The IMF could be allowed to borrow in the capital markets, potentially using currently unused SDRs as collateral. Such lending would have to be associated with important safeguards to prevent private sector bias in lending, but it could significantly increase IMF firepower.

8. Pool balance sheets to increase MDB borrowing capacity

On the side of the development finance institutions, there should be scope for more pooling of balance sheets, after all they have more or less the same shareholders, if in somewhat different constellations. There are limits to what can be achieved through such efforts, but particularly for the smaller institutions with concentrated portfolios this could prove very important. As a by-product, the participating institutions would be encouraged to standardize loan agreements and generally become more coherent as a system.

9. Crowd in private and institutional capital on country platforms

A core EPG proposal is the establishment of country platforms where governments can coordinate their collaboration with international financial institutions, including bilateral donors and the entire UN system. These platforms, now being piloted in a large number of countries, should be opened up to the private sector and be used to crowd in private and institutional capital by mitigating risk for investors, but also to ensure that agreed governance standards are enforced and debt sustainability requirements respected.

When the EPG was first set up there were questions as to why the group should deal with both the development finance architecture and the global financial safety net in the same report. The COVID-19 crisis has proven how intimately linked these are. The nine ideas we have put forward here would bring together the global financial safety net, the development finance architecture and the private sector to enable the powerful global response that the current crisis requires.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Health and Healthcare Systems .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Half the world is affected by oral disease – here’s how we can tackle this unmet healthcare need

Charlotte Edmond

May 23, 2024

This is how stress affects every organ in our bodies

Michelle Meineke and Kateryna Gordichuk

May 22, 2024

The care economy is one of humanity's most valuable assets. Here's how we secure its future

May 21, 2024

Antimicrobial resistance is a leading cause of global deaths. Now is the time to act

Dame Sally Davies, Hemant Ahlawat and Shyam Bishen

May 16, 2024

Inequality is driving antimicrobial resistance. Here's how to curb it

Michael Anderson, Gunnar Ljungqvist and Victoria Saint

May 15, 2024

From our brains to our bowels – 5 ways the climate crisis is affecting our health

May 14, 2024

header.search.error

Search Title

Can economics solve climate change.

Global leaders and a myriad of economic policies are working on tackling climate change, but is it enough? Nobel Laureates discuss the role economics can play, the impact of globalization, and the structures that are helping, and hurting, our ability to achieve real progress.

In 2018, the winners of the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences were awarded for papers and models integrating technological innovations into long-run macroeconomic analysis. It was seen by many as a significant choice made by the Nobel Committee to blend nature and knowledge, to highlight work that examines not just climate change but how it is affecting the economy and the importance of this knowledge. Economist and Nobel Laureate Paul Romer represents one half of the winning prize, but many of his fellow economists agree: economics may just be one of the most important tools when it comes to solving climate change.

Clever Solutions Without the Harm

“I don't think solving global warming is going to be that hard of a problem to solve,” says Romer. “The reason that the problem keeps getting worse is that we're not trying to solve it. All we have to do is create some incentives to solve the problem. And everybody's going to be astonished at all the clever, clever ways that the market comes up with to produce and distribute energy that doesn't rely on the side effect of emitting carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases.”

He points to a time in recent history, the 1970s, when the United States started producing and emitting a particular chemical, chlorofluorocarbon, that was damaging the ozone layer. A big, global approach was needed to address the damage being done and to protect the ozone layer. In the 1980s, the Reagan administration encouraged a ban on the production of chlorofluorocarbons and then negotiated treaties with countries around the world to join the ban.

Once you stop the harm, people are going to find incredibly clever ways to make money without doing the harm.

What does the future of humans look like?

Learn more from CIO’s report on the Future of Humans

“Before the ban went into effect, the leaders in the industry who were producing all these chemicals were saying, ‘The economy won’t survive. Our way of life will be threatened.’ It was just all nonsense,” says Romer. “Nobody even noticed the small changes we had to make to find something else other than chlorofluorocarbons to use. I think that a lot of this ‘Oh it’s going to be so hard [to address climate change]’ is from people who are making money harming everybody else. Once you stop the harm, people are going to find incredibly clever ways to make money without doing the harm.”

Environmental Models

There are many different perspectives and tools that economists have at their disposal that could be used to fight climate change, according to fellow Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz. Further integration of environmental models into the overall economic framework is a powerful start, but certainly not where it ends.

“For a long time, people have been working on integrating economic models with environmental models,” says Stiglitz. “One of the things that economists forgot for a long time is that we have to live within our planetary boundaries. That's a constraint. We talk about budget constraints, various other kinds of constraints. But the constraint to living within our planetary boundaries, of getting the energy balances right, is a constraint to which we didn't pay enough attention. Economists have also played an important role in trying to highlight how we think about the issue of how much risk we're willing to take.”

Economists have also played an important role in trying to highlight how we think about the issue of how much risk we're willing to take.

Stiglitz points out that while we don’t know what the full effects of the concentration of greenhouse gases will ultimately be, we do have enough knowledge to know that it could be catastrophic. The awareness of the magnitude of this risk is part of the argument for urgency. Economics can help provide a framework when trying to answer questions like what is the best way of accomplishing our goals, or do we use regulation, a price or public investment?

“One needs to have a rich panoply of instruments,” says Stiglitz. “One cannot simply rely on a price intervention or regulatory interventions on their own. Public investments are going to be absolutely crucial.”

Economics’ Crucial Role

For Esther Duflo, the second woman ever to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 2019, it is not a matter of if economics can help address the issue, it’s simply a matter of how. Duflo and her co-laureates were awarded the prize for their experimental approach to alleviating global poverty, fueled largely by randomized controlled trials. A willingness to experiment, and iterate, has been the key to success for Duflo, and may be crucial in this case as well.

“I think economics has to help fight climate change. We can't do it without economics,” says Duflo. “There will be no progress unless we find ways that people change their behavior and economics in a way is about how human behavior responds to the set of incentives and the social environment that is around us.”

Duflo says that it isn’t as simple as economists previously thought, that putting a price a carbon means that the price of carbon goes up and people consume less. She says that energy consumption, like many things in our lives, is a matter of habit.

“There’s the industrial organization of it, there’s the behavioral economics of it, there’s a political economy of it, and all of these really need to focus on how we get people to change their behavior,” says Duflo. “We understand that something needs to be done. Carbon emissions have to go down.”

I think economics has to help fight climate change. We can't do it without economics.

Global Accountability

Nobel Laureate Michael Spence, an expert on economic growth and sustainable growth, says there is still work to do on how we assess and measure environmental activity and changes. Spence also sees technology playing a crucial role to help minimize any negative side effects that could arise during transitions. It’s also a matter of global leadership and accountability.

“People ask the question, ‘Well, in tackling climate change, are we going to reduce economic performance?’,” says Spence. “Well, there's disagreement about this. Maybe yes, maybe no. But the whole point of the exercise is not the short run. The whole point of the exercise is not to have a catastrophic collapse somewhere down the road. And so, I think the way in which we assess economic performance today makes it more difficult to address these long-term challenges.”

The shift to greener energy sources is not something that will happen overnight. According to Spence, we are looking at a multi-decade transition in which the energy efficiency increases, and the fossil fuel component of the energy mix declines, particularly in electricity generation, but not exclusively. For this, we need a plan and technology.