- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Qin Dynasty

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 16, 2023 | Original: December 21, 2017

The Qin Dynasty established the first empire in China, starting with efforts in 230 B.C., during which the Qin leaders engulfed six Zhou Dynasty states. Their reign over Imperial China existed only briefly—from 221 to 206 B.C.—but the Qin Dynasty had a lasting cultural impact on the dynasties that followed.

Capital of Qin Dynasty

The Qin (pronounced “chin”) region was located in modern-day Shaanxi province, north of the Zhou Dynasty territory—Qin served as a barrier between it and the less civilized states north of it. The capital of the Qin Dynasty was Xianyang, which was extensively enlarged after Qin dominance was established.

Qin itself had been considered a backwards, barbarian state by the ruling Zhou Dynasty. This distinction had to do with its slow pace in embracing Chinese culture, for instance, lagging behind the Zhou in doing away with human sacrifice.

The ruling class of Qin nonetheless believed themselves to be legitimate heirs to the Zhou states, and through the centuries they strengthened their diplomatic and political standing through a variety of means, including strategic marriages.

It was during the rule of Duke Xiao from 361 to 338 B.C. that the groundwork was laid for conquest, primarily through the work of Shang Yang, an administrator from the state of Wey who was appointed Chancellor.

Shang Yang was a vigorous reformer, systematically reworking the social order of Qin society, eventually creating a massive, complex bureaucratic state and advocating for the unification of Chinese states.

Among Shang Yang’s innovations was a successful system to expand the army beyond the nobility, giving land as a reward to peasants who enlisted. This helped create a massive infantry that was less expensive to maintain than the traditional chariot forces.

Following Duke Xiao’s death, Shang Yang was charged with treason by the old aristocrats in the state. He attempted to fight and create his own territory but was defeated and executed in 338 B.C. with five chariots pulling him apart for spectators in a market. But Shang Yang’s ideas had already laid the foundation for the Qin Empire.

The state of Qin began to expand into the regions surrounding it. When the states of Shu and Ba went to war in 316 B.C., both begged for Qin’s help.

Qin responded by conquering each of them and, over the next 40 years, relocating thousands of families there, and continuing their expansionist efforts into other regions.

Ying Zheng is considered the first emperor of China. The son of King Zhuangxiang of Qin and a concubine, Ying Zheng took the throne at the age of 13, following his father’s death in 247 B.C. after three years on the throne.

Qin Shi Huang

As the ruler of Qin, Ying Zheng took the name Qin Shi Huang Di (“first emperor of Qin”), which brings together the words for “Mythical Ruler” and “God.”

Qin Shi Huang began a militarily-driven expansionist policy. In 229 B.C., the Qin seized Zhao territory and continued until they seized all five Zhou states to create a unified Chinese empire in 221 B.C.

Advised by the sorcerer Lu Sheng, Qin Shi Huang traveled in secrecy through a system of tunnels and lived in secret locations to facilitate communing with immortals. Citizens were discouraged from using the emperor’s personal name in documents, and anyone who revealed his location would face execution.

Qin Unification

Qin Shi Huang worked quickly to unify his conquered people across a vast territory that was home to several different cultures and languages.

One of the most important outcomes of the Qin conquest was the standardization of non-alphabetic written script across all of China, replacing the previous regional scripts. This script was simplified to allow faster writing, useful for record keeping.

The new script enabled parts of the empire that did not speak the same language to communicate together, and led to the founding of an imperial academy to oversee all texts. As part of the academic effort, older philosophical texts were confiscated and restricted (though not destroyed, as accounts during the Han Dynasty would later claim).

The Qin also standardized weights and measures, casting bronze models for measurements and sending them to local governments, who would then impose them on merchants to simplify trade and commerce across the empire. In conjunction with this, bronze coins were created to standardize money across the regions.

With these Qin advances, for the first time in their history, the various warring states in China were unified. The name China, in fact, is derived from the word Qin (which was written as Ch'in in earlier Western texts).

Great Wall of China

The Qin empire is known for its engineering marvels, including a complex system of over 4,000 miles of road and one superhighway, the Qinzhidao or “Straight Road ,” which ran for about 500 miles along the Ziwu Mountain range and is the pathway on which materials for the Great Wall of China were transported.

The empire’s borders were marked on the north by border walls that were connected, and these were expanded into the beginnings of the Great Wall.

Overseen by the Qin road builder Meng Tian, 300,000 workers were brought to work on the construction of the Great Wall, and on the service roads required to transport supplies.

Qin Shi Huang's Monuments

Qin Shi Huang was noted for audacious marvels of art and architecture meant to celebrate the glory of his new dynasty.

Each time Qin made a new conquest, a replica of that state’s ruling palace was constructed across from Qin Shi Huang’s Palace along the Wei River, then linked by covered walkways and populated by singing girls brought in from the conquered states.

Weapons from Qin conquests were collected and melted down, to be used for the casting of giant statues in the capital city Xianyang.

Qin Shi Huang Tomb

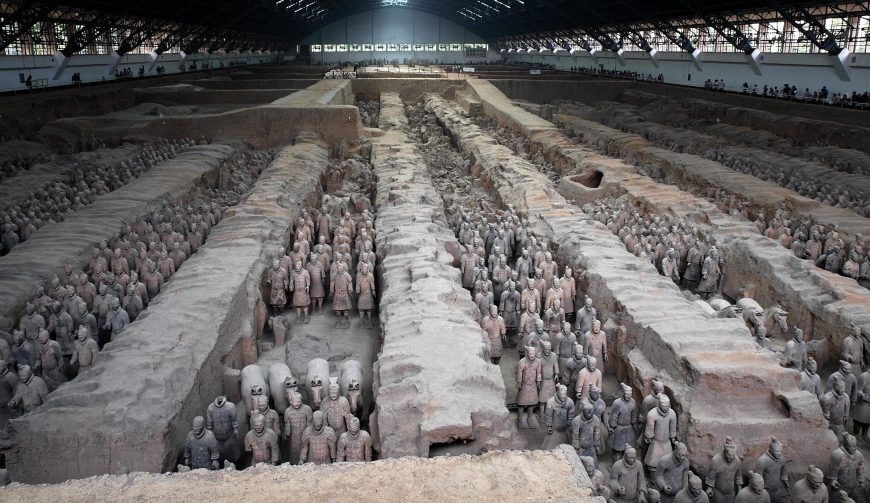

For his most brash creation, Qin Shi Huang sent 700,000 workers to create an underground complex at the foot of the Lishan Mountains to serve as his tomb. It now stands as one of the seven wonders of the world.

Designed as an underground city from which Qin Shi Huang would rule in the afterlife, the complex includes temples, huge chambers and halls, administrative buildings, bronze sculptures, animal burial grounds, a replica of the imperial armory, terracotta statues of acrobats and government officials, a fish pond and a river.

Terracotta Army

Less than a mile away, outside the eastern gate of the underground city, Qin Shi Huang developed an army of life-size statues—almost 8,000 terracotta warriors and 600 terracotta horses, plus chariots, stables and other artifacts.

This vast complex of terracotta statuary, weapons and other treasures—including the tomb of Qin Shi Huang himself—is now famous as the Terracotta Army .

Excavation of the tomb of Qin Shi Huang has been delayed due to high levels of toxic mercury at the site—it’s believed that the emperor had the liquid mercury installed in the tomb to mimic rivers and lakes.

Death of Qin Shi Huang

Qin Shi Huang died in 210 B.C. while touring eastern China. Officials traveling with him wanted to keep it secret, so to disguise the stench of his corpse, filled up 10 carts with fish to travel with his body.

They also forged a letter from Qin Shi Huang, sent to crown prince Fu Su, ordering him to commit suicide, which he did, allowing the officials to establish Qin Shi Huang’s younger son as the new emperor.

End of the Qin Dynasty

In two years time, most of the empire had revolted against the new emperor, creating a constant atmosphere of rebellion and retaliation. Warlord Xiang Yu in quick succession defeated the Qin army in battle, executed the emperor, destroyed the capital and split up the empire into 18 states.

Liu Bang, who was given the Han River Valley to rule, quickly rose up against other local kings and then waged a three-year revolt against Xiang Yu. In 202 B.C., Xiang Yu committed suicide, and Liu Bang assumed the title of emperor of the Han Dynasty, adopting many of the Qin dynasty institutions and traditions.

HISTORY Vault: Ancient Top 10

From Stonehenge and the Colossus of Rhodes to the Colosseum and the Temple of Karnak. The greatest monuments of the ancient world show more than wealth, they show power.

The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han. Mark Edward Lewis . Early China: A Social and Cultural History. Li Feng . Emperor Qin’s Tomb. National Geographic . Qin Dynasty. World History Encyclopedia .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

23.4: The Qin Dynasty

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 53025

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

The Qin Dynasty

The Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE), though short-lived, is remembered for its military strength and its unification of China.

Learning Objectives

Describe the establishment of the first imperial dynasty of China and the architecture, literature, weaponry, and sculpture it produced

Key Takeaways

- In the mid and late 3rd century BCE, the Qin accomplished a series of swift conquests, eventually gaining control over the whole of China and creating a unified nation.

- During its reign , the Qin Dynasty achieved increased trade, improved agriculture, and revolutionary developments in military tactics, transportation, and weaponry, such as the sword and crossbow.

- The Dynasty is known for several impressive feats in architecture, sculpture, and other art, such as the beginnings of the Great Wall of China, the construction of the Terracotta Army, and the standardization of the writing system.

- Qin Shihuang : The self-proclaimed first Emperor of the Qin Dynasty.

- Warring States Period : A period in ancient China following the Spring and Autumn period and concluding with the victory of the state of Qin in 221 BCE, creating a unified China under the Qin Dynasty.

- legalism : A philosophy of focusing on the text of written law to the exclusion of the intent of law, elevating strict adherence to law over justice, mercy, grace and common sense.

History: The Qin Dynasty

The Qin Dynasty was the first imperial dynasty of China, lasting only 15 years from 221 to 206 BCE. The strength of the Qin state was greatly increased by the legalist reforms of Shang Yang in the 4 th century BCE, during the Warring States Period . Legalism is a philosophy of focusing on the text of written law to the exclusion of the intent of law, elevating strict adherence to law over justice, mercy, grace, and common sense. In the mid and late 3rd century BCE, the Qin accomplished a series of swift conquests, first ending the powerless Zhou Dynasty and eventually destroying the remaining six of the major states, thus gaining control over the whole of China. This resulted in the first-ever unified China.

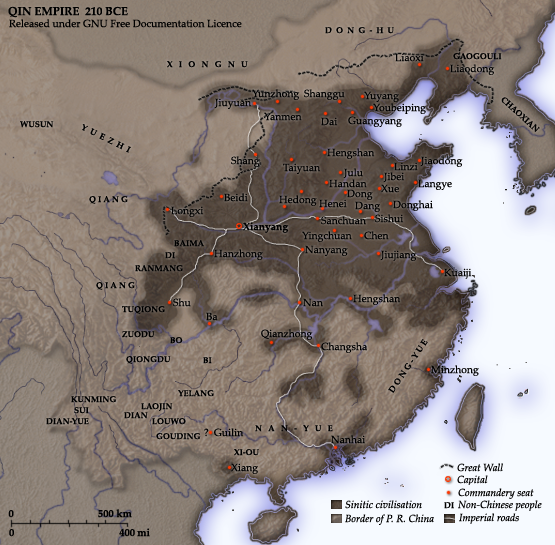

Map of the Qin Empire, 210 BCE : The territories marked with red dots show the approximate extent of Qin political control at the death of Qin Shi Huang in 210 BCE.

Accomplishments of the Qin Dynasty

During its reign over China, the Qin Dynasty achieved increased trade, improved agriculture, and revolutionary developments in military tactics, transportation, and weaponry. Qin Shihuang , the self-proclaimed first Emperor of the Qin Dynasty, made vast improvements to the military, which used the most advanced weaponry of its time. The sword was invented during the previous Warring States Period, first made of bronze and later of iron. The crossbow had been introduced in the 5th century BCE and was more powerful and accurate than the composite bows used earlier; it could also be rendered ineffective by removing two pins, which prevented enemies from capturing a working crossbow.

Picture of Qin Dynasty Arcuballista Bolts shown with Regular Handheld Crossbow Bolts, 5th-3rd century B.C. : The crossbow was introduced in the 5th century BC and was more powerful and accurate than the composite bows used earlier.

The Dynasty is also known for many impressive feats in architecture, sculpture, and other art, such as the beginnings of the Great Wall of China, the construction of the Terracotta Army, and the standardization of the writing system.

Decline of the Dynasty

Despite its military strength, however, the Dynasty did not last long. When Qin Shihuang died in 210 BCE, his son was placed on the throne by two of the previous emperor’s advisers, who attempted to influence and control the administration of the entire dynasty through him. The advisers fought among themselves, however, which resulted in both their deaths and that of the second Qin emperor. Popular revolt broke out a few years later, and the weakened empire soon fell to a Chu lieutenant, who went on to found the Han Dynasty. Despite its rapid end, the Qin Dynasty influenced future Chinese empires, particularly the Han, and the European name for China is thought to be derived from it.

Architecture of the Qin Dynasty

Qin architecture is characterized by defensive structures and elements that conveyed authority and power, as exemplified by the early beginnings of the Great Wall.

Examine the characteristics of architecture created under the Qin Dynasty

- Architecture from the previous Warring States Period had several definitive aspects which carried into the Qin Dynasty .

- City walls used for defense were made longer, and secondary walls were often built to separate the different districts.

- Versatility in federal structures was emphasized to create a sense of authority and absolute power, conveyed by architectural elements such as high towers, pillar gates, terraces, and high buildings.

- Qin Shihuang , the self-proclaimed first Emperor, is responsible for the initial construction of what later became the Great Wall of China, which he built along the northern border to protect his empire against the Mongols .

- Great Wall of China : A series of fortifications made of stone, brick, tamped earth, wood, and other materials, generally built along an east-to-west line across the historical northern borders of China to protect the Chinese states and empires against the raids and invasions of the nomadic groups of the Eurasian Steppe.

The Qin Dynasty was the first imperial dynasty of China, lasting from 221 to 206 BCE. The Dynasty followed the Warring States Period and resulted in the unification of China, ending 15 years later with the introduction of the Han Dynasty.

Architecture from the Warring States Period had several definitive aspects which carried into the Qin Dynasty. City walls used for defense were made longer, and secondary walls were often built to separate the different districts. Versatility in federal structures was emphasized to create a sense of authority and absolute power, conveyed by architectural elements such as high towers, pillar gates, terraces, and high buildings.

The Beginnings of the Great Wall

During its reign over China, the Qin sought to create an imperial state unified by highly structured political power and a stable economy able to support a large military. The Qin central government minimized the role of aristocrats and landowners to have direct administrative control over the peasantry, who comprised the overwhelming majority of the population and thus made up a large labor force. This allowed for the construction of ambitious projects such as the wall on the northern border now known as the Great Wall of China.

Qin Shihuang, the first self-proclaimed emperor of the Qin Dynasty, developed plans to fortify the northern border against the nomadic Mongols. The result was the initial construction of what later became the Great Wall of China, built by joining and strengthening the walls made by the feudal lords. These were expanded and rebuilt multiple times by later dynasties, also in response to threats from the north.

The Great Wall of China at Jinshanling : The initial construction of what would become the Great Wall of China began under Qin Shihuang during the Qin Dynasty.

Literature of the Qin Dynasty

Under the Qin Dynasty, a standardized system of Chinese writing was created. This unified Chinese culture for thousands of years.

Discuss the goals of literature produced during the Qin Dynasty

- Prime Minister Li Si standardized the writing system across the whole country. This unified Chinese culture for thousands of years.

- Li Si is credited with creating the “lesser-seal” style of calligraphy , also known as small seal script. This served as a basis for the modern Chinese writing system and is still used in cards, posters, and advertising today.

- In 221 BC, Qin Shihuang , the first Qin emperor, conquered all of the Chinese states and governed with a single philosophy known as legalism . This encouraged severe punishments, particularly when the emperor was disobeyed.

- An attempt to purge all traces of the old dynasties and their philosophies led to the infamous burning of books and burying of scholars incident in 213 BCE.

- In an attempt to consolidate power, Qin Shihuang ordered the burning of all books on non-legalist philosophical viewpoints and intellectual subjects; scholars who refused to submit their books were executed.

- logographic : A writing system based on characters that represent a word or phrase, such as Chinese characters, Japanese kanji, and some Egyptian hieroglyphs.

- legalism : A philosophy focusing on the text of written law to the exclusion of the intent of law, elevating strict adherence to law over justice, mercy, grace, and common sense.

Li Si and the Standardization of Writing

The written language of the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE) was logographic like that of the Zhu; each written character represented a word or phrase, as opposed to letters as in the English alphabet. As one of his most influential achievements, prime minister Li Si of the Qin Dynasty standardized the writing system to be of uniform size and shape across the whole country. This had a unifying effect on Chinese culture that lasted thousands of years. Li Si is also credited with creating the “lesser-seal” style of calligraphy, also known as small seal script. This served as a basis for the modern Chinese writing system and is still used in cards, posters, and advertising today.

Before the Qin conquest of the last six of the Warring States of Zhou China, local styles of characters evolved independently for centuries, producing what are called the “Scripts of the Six States” or “Great Seal Script”. Under one unified government however, the diversity was deemed undesirable as it hindered timely communication, trade, taxation, and transportation. In addition, independent scripts could express dissenting political ideas.

As a result, coaches, roads, currency, laws, weights, measures, and writing were systematically unified under the Qin. Characters different than those found in Qin were discarded, and Li Si’s small seal characters became the standard for all regions within the empire. This policy came into effect around 220 BCE, the year after Qin’s unification of the Chinese states, and was introduced by Li Si and two ministers.

Small Seal Script : Small seal script is an archaic form of Chinese calligraphy standardized and promulgated as a national standard by Li Si, prime minister under the Qin Dynasty.

The Burning of Books

One of the more drastic measures to eradicate the old schools of thought during the Qin Dynasty was the infamous burning of books and burying of scholars incident. This decree, passed in 213 BCE, almost single-handedly gave the Qin Dynasty a bad reputation in history. In an attempt to consolidate power, Qin Shihuang ordered the burning of all books on non-legalist philosophical viewpoints and intellectual subjects. All scholars who refused to submit their books were executed. As a result, only texts considered productive by the legalists (largely discussing pragmatic subjects such as agriculture, divination, and medicine) were preserved.

A Consolidation of Power

During the previous Warring States period, the Hundred Schools of Thought comprised many philosophies proposed by Chinese scholars, including Confucianism . In 221 BC, Qin Shihuang, the first Qin emperor, conquered all of the Chinese states and governed with a single philosophy known as legalism. This encouraged severe punishments, particularly when the emperor was disobeyed. Individuals’ rights were devalued when they conflicted with the government’s or the ruler’s wishes, and merchants and scholars were considered unproductive and fit for elimination. During the dynasty, Confucianism—along with all other non-legalist philosophies—was suppressed by the First Emperor.

Killing the Scholars and Burning the Books (18th century Chinese painting) : In 213 BCE, Qin Shihuang ordered the burning of all books on non-legalist philosophical viewpoints and intellectual subjects. All scholars who refused to submit their books were executed.

Sculpture of the Qin Dynasty

The Qin Dynasty is perhaps best known for the impressive Terracotta Army, built to protect Qin Shihuang in the afterlife.

Evaluate the sculpture of the Qin Dynasty

- The Qin, under the leadership of emperor Qin Shihuang , accomplished a series of swift conquests and gained control over all of China, unifying it as a country for the first time.

- The Qin made many advancements in sculpture during their short reign, building on techniques practiced by the previous Zhou Dynasty .

- The most famous example of sculpture under the Qin Dynasty was a project commissioned during Qin Shihuang’s rule known as the Terracotta Army, intended to protect the emperor after his death.

- The Terracotta Army consists of more than 7,000 life-size terracotta figures of warriors and horses, buried with Qin Shihuang after his death in 210–209 BCE.

- Originally, the figures were painted with bright pigments of pink, red, green, blue, black, brown, white, and lilac; however, much of the color coating flaked off or faded.

- The figures were constructed in several poses, including standing infantry, kneeling archers, and charioteers with horses.

- terracotta : A type of earthenware, clay-based unglazed or glazed ceramic, in which the fired body is porous.

The Qin Dynasty was the first imperial dynasty of China, lasting from 221 to 206 BCE. The Dynasty followed the Warring States Period and ended after only 15 years with the Han Dynasty. The Qin, under the leadership of its first self-proclaimed emperor Qin Shihuang, accomplished a series of swift conquests, first ending the powerless Zhou Dynasty and eventually destroying the remaining six of the major states and gaining control of all of China. Under the Qin, it was unified as a country for the first time. The Qin made many advancements in sculpture during their short reign, building on techniques practiced by the previous Zhou Dynasty.

The Terracotta Army

The most famous example of sculpture under the Qin Dynasty was a project commissioned during Qin Shihuang’s rule known as the Terracotta Army, intended to protect the emperor after his death. The Terracotta Army was inconspicuous due to its underground location and thus not discovered until 1974. The “army” of sculptures consists of more than 7,000 life-size terracotta figures of warriors and horses that were buried with Qin Shihuang after his death in 210–209 BCE. The three pits containing the Terracotta Army were estimated in 2007 to hold more than 8,000 soldiers, 130 chariots with 520 horses, and 150 cavalry horses, the majority of which remained buried in the pits nearby Qin Shi Huang’s mausoleum . Non-military terracotta figures were found in other pits, including officials, acrobats, strongmen, and musicians.

Style of the Figures

The figures were painted in bright pigments before they were placed in the vault , and the original colors of pink, red, green, blue, black, brown, white, and lilac were visible when the pieces were first unearthed. However, exposure to air has caused the pigments to fade and flake off, revealing their natural terracotta color. The figures were constructed in several poses, including standing infantry, kneeling archers, and charioteers with horses. They vary in height according to their roles, with the generals tallest, and each figure’s head appears to be unique, with a variety of facial features, expressions, and hair styles. Along with the colored lacquer finish, the individual facial features would have given the figures a realistic feel.

The Terracotta Army : The Terracotta Army consists of more than 7,000 life-size terracotta figures of warriors and horses, buried with the first Emperor of Qin in 210 BCE.

Construction

The terracotta army figures were manufactured in workshops by government laborers and local craftsmen using local materials. Heads, arms, legs, and torsos were created separately and then assembled. Eight face molds were most likely used, with clay added after assembly to provide individual facial features. It is believed that the legs were made using the same process used for terracotta drainage pipes. This would classify the process as assembly line production, with specific parts manufactured and assembled after being fired, as opposed to being crafted from one solid piece and subsequently fired. In those times of tight imperial control, each workshop was required to inscribe its name on items produced to ensure quality control.

- Curation and Revision. Provided by : Boundless.com. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Qin empire 210 BCE. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Qin_empire_210_BCE.png. License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Qinacruballistabolts. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Qinacruballistabolts.jpg. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Art of China. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_of_China. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Qin dynasty. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Qin_dynasty. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Warring States Period. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Warring%20States%20Period. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Legalism. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Legalism. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Qin Shihuang. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Qin%20Shihuang. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 360px-The_Great_Wall_of_China_at_Jinshanling-edit.jpg. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Wall_of_China#/media/File:The_Great_Wall_of_China_at_Jinshanling-edit.jpg. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Qin Dynasty. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Qin_dynasty. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Qin Dynasty. Provided by : Boundless. Located at : www.boundless.com/art-history/textbooks/boundless-art-history-textbook/chinese-and-korean-art-before-1279-ce-14/the-qin-dynasty-96/the-qin-dynasty-459-5603/issues/new/. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- XiaozhuanQinquan.jpg. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Small_Seal_Script#/media/File:XiaozhuanQinquan.jpg. License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Killing_the_Scholars%2C_Burning_the_Books.jpg. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Burning_of_books_and_burying_of_scholars#/media/File:Killing_the_Scholars,_Burning_the_Books.jpg. License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Small seal script. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Small_Seal_Script. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Burning of books and burying of scholars. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Burning_of_books_and_burying_of_scholars. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Logogram. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Logogram. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Li Si . Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Li_Si. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- [email protected] . Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Terracotta_Army-China2.jpg. License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- The Qin Dynasty. Provided by : Boundless. Located at : www.boundless.com/art-history/textbooks/boundless-art-history-textbook/chinese-and-korean-art-before-1279-ce-14/the-qin-dynasty-96/the-qin-dynasty-459-5603/issues/new/. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Terracotta Army. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Terracotta_Army. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Art of Asia

Course: art of asia > unit 2, qin dynasty (c. 221–206 b.c.e.), an introduction.

- The Tomb of the First Emperor

- The Terracotta Warriors

- Terracotta Warriors from the mausoleum of the first Qin emperor of China

Additional resources:

Want to join the conversation.

Qin dynasty (c. 221–206 B.C.E.), an introduction

Jar (hu), Qin dynasty, 221 B.C.-206, ceramic, China, 34.3 high x 25.6 x 22.6 cm (Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.: Long-term loan from the Smithsonian American Art Museum ; gift of John Gellatly, 1929.8.328, LTS1985.1.328.1)

Map of the Qin Empire (underlying map © Google)

At the end of the Warring States period (475–221 B.C.E.), the state of Qin conquered all other states and established the Qin dynasty (221–206 B.C.E.). It was China’s first unified state whose power was centralized instead of spread among different kingdoms in the north and south. Although it lasted only about fifteen years, the Qin dynasty greatly influenced the next two thousand years of Chinese history.

The first emperor of Qin, known as Qin Shihuangdi (literally “First Emperor,” 259–210 B.C.E.), instituted a central and systematic bureaucracy. He divided the state into provinces and prefectures governed by appointed officials. This administrative structure has served as a model for government in China to the present day. Shihuangdi sought to standardize numerous aspects of Chinese life, including weights and measures, coinage, and the writing system. These standards would last for centuries after the fall of his short-lived dynasty. He also ordered many construction projects. He expanded the network of roads and canals throughout the country. The first Great Wall (not the one that exists today) was built during his reign.

Mausoleum of Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi, Overview Image of Pit 1 (photo: mararie, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Despite the many accomplishments of the Qin dynasty, Shihuangdi was considered a severe ruler. He was intolerant of any threats to his rule and established harsh laws to maintain his control. He had his chief advisor burn all books that were not written on subjects he considered useful (useful subjects included agriculture and medicine) and reportedly buried hundreds of scholars alive.

Mausoleum of Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi, Warriors (photo: scottgunn, CC BY-NC 2.0)

The Qin dynasty is one of the best-known periods in Chinese history in the West because of the 1974 discovery of thousands of life-size terracotta warriors. They were part of the vast army guarding the tomb of Qin Shihuangdi. These figures were modeled after general categories of soldiers, such as archers and infantrymen, but possessed some individual characteristics as well. The warriors reflect Shihuangdi’s reliance on the military to create and maintain a unified China and indicate his desire to retain a protective army in the afterlife.

Following the death of Qin Shihuangdi, the Qin dynasty collapsed into chaos. In 206 B.C.E., China was reunited under the rule of the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 C.E.).

This resource was developed for Teaching China with the Smithsonian, made possible by the generous support of the Freeman Foundation

Additional resources:

See this essay on Teaching China from the Smithsonian

Cite this page

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Historical Archaeology (Qin and Han)

Introduction, archaeological overviews.

- Anthologies of Essays by Experts in Qin and Han Archaeology

- Early Historiographic and Antiquarian Research

- History of Archaeology of the Qin and Han

- Bibliographies and Databases

- Xianyang, Qin Capital City

- Chang’an, Western Han Capital City

- Luoyang, Eastern Han Capital City

- Tomb of the Western Han Emperor Jing at Yangling, Shaanxi Province

- Tomb of Prince Liu at Mancheng, Hebei Province

- Tomb of Liu He at Nanchang, Jiangxi Province

- Han Tombs at Mawangdui, Changsha, Hunan Province

- The Wu Family Shrines, Shandong Province

- Pictorial Tomb Reliefs

- Silk and Other Textiles

- Bronze Metallurgy

- Iron Metallurgy

- Classical World-Han China Connections

- Interactions with the Steppe: Han and the Xiongnu

- Interactions with the Korean Peninsula

- South China

- The Nanyue Kingdom

- The Southwestern Periphery: Dian and Its Neighbors

- Yunnan Bronzes

- Politics and Nationalism in Qin-Han Archaeology

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Early Imperial China

- Heritage Management

- The Terracotta Warriors

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Taiwan’s Miracle Development: Its Economy over a Century

- The Jesuit Missions in China, from Matteo Ricci to the Restoration (Sixteenth-Nineteenth Centuries)

- The One-Child Policy

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Historical Archaeology (Qin and Han) by Robert E. Murowchick LAST REVIEWED: 28 August 2018 LAST MODIFIED: 28 August 2018 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199920082-0158

The Qin and Han empires (221 BCE to 220 CE ) represent one of the most momentous periods of early China as it moved from an evolving mosaic of contending states and cultures to a relatively unified imperial state. Political, ritual, social, and economic changes put in place during these four centuries would greatly influence the dynasties that followed. During the Warring States period ( c . 475–221 BCE ), the major states of the North China Plain and central China vied for supremacy. The northwestern state of Qin eventually dominated the region and succeeded in bringing the first unification of China in 221 BCE under the First Emperor, Qin Shihuangdi. With the Han conquest of Qin only a decade later, a four century long period of imperial unity was brought to much of China that extended Han control into neighboring tributary states in the northeast, south, and southwest, and established rich and complex military and economic interactions with much of Asia. This early imperial period is well known through abundant traditional literary and historical sources, the details of which can be found in the comprehensive Historical Overviews . However, these texts record only a small part of life and society during the Qin and Han periods. Archaeology, first introduced in China in the 1910s and 1920s, and dramatically expanded since the 1970s, has yielded an increasingly rich array of material evidence of exceptional diversity and quantity—it is estimated that more than ten thousand Han dynasty tombs have been excavated, not to mention residential, production, and other sites. These new finds have dramatically improved our understanding of the Qin and Han periods, including its urban centers, ritual and mortuary practices, military prowess, details of workshop organization and labor, interactions with neighboring cultures, and the exquisite refinements in a range of arts, crafts, industries, and scientific/technological endeavors that took shape during this pivotal period. Finally, note that the terms “Qin” and “Han” have both cultural and chronological meaning, and archaeological materials from “non-Chinese” cultures with which the Qin and Han empires came into contact represent some of the most exciting aspects of recent archaeological scholarship.

Field archaeology in China has expanded dramatically since the 1970s, including much new fieldwork on the Qin and Han periods. There are many excellent overviews of the key archaeological discoveries, published both in English and in Chinese, that have added greatly to our understanding of early imperial China. Two authoritative volumes ( Li 1985 and Wang 1982 ) were written by eminent Chinese scholars and translated by K. C. Chang for Yale’s Early Chinese Civilization Series . Their titles are a bit misleading in that both works really focus on the archaeological remains of these cultures and do not provide detailed cultural or historical discussions of Qin or Han (which can be found instead in some of the Historical Overviews ). The archaeological data they do present is comprehensive as befits the expertise of their authors: Li Xueqin 李学勤, director of the Department of Pre-Qin History in the Institute of History, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and of the Institute of Sinology at Tsinghua University, is renowned for his wide-ranging research on China’s ancient history, archaeology, epigraphy and paleography, and Wang Zhongshu 王仲殊 (b. 1925–d. 2015) was one of China’s most senior archaeologists of the Han period and former director of the Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. A more readable overview of Han art, archaeology, and society is Pirazzoli-t’Serstevens 1982 . Readers will need to supplement all three of these volumes, however, with more recent publications that reflect key discoveries since the early 1980s. Liu 2013 and Liu 2015 fill this need perfectly, with excellent contributed essays and an abundance of recent color photographs of the most important work at the First Emperor of Qin’s mausoleum complex and other sites. Yang 2004 is also a terrific place to start, with excellent photos and clear and concise presentations of the most important Qin and Han sites. For those who can read Chinese, there are more than a dozen excellent volumes on Qin and Han archaeology, among them Wang and Liang 2001 and Zhao and Gao 2002 . Pines, et al. 2013 reflects the vibrant scholarly debate about how interpretations of new archaeological data contradict or support traditional historical understandings of Qin and Han history and society, and whether Qin unification represents a rupture from or a continuation of many aspects of eastern Zhou society that preceded it.

Li, Xueqin. Eastern Zhou and Qin Civilizations . Translated by K. C. Chang. New Haven, CT, and London: Yale University Press, 1985.

Comprehensive survey of archaeological discoveries from the 8th to 3rd centuries BCE . Especially useful are chapter 14 to understand Qin’s predynastic foundations, and chapter 15 for its archaeological details both fabulous and mundane, rather than just selected “treasures” (see Oxford Bibliographies article in Chinese Studies “ The Terracotta Warriors ”). Li’s inclusion of divergent opinions reflects the dynamism of modern Chinese archaeology. Black-and-white illustrations have captions that are both too brief and unsourced.

Liu, Yang, ed. China’s Terracotta Warriors: The First Emperor’s Legacy . Minneapolis: Minneapolis Institute of Art, 2013.

Superb catalogue for the Qin exhibition at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts (2012–2013) and the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco (2013), with up-to-date discussion and photos of recent finds. Includes key recent archaeological work at the First Emperor’s vast mausoleum complex beyond the well-known terracotta army formations.

Liu, Yang, ed. Beyond the First Emperor’s Mausoleum: New Perspectives on Qin Art . Minneapolis: Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 2015.

Selection of scholarly papers presented in October 2012 at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts for its symposium, “China’s Terracotta Warriors: The First Emperor’s Legacy.” Focuses on recent archaeological discoveries and our changing understanding of Qin culture and Qin empire. An excellent complement to Pines, et al. 2013 .

Pines, Yuri, Gideon Shelach, Lothar von Falkenhausen, and Robin D. S. Yates, eds. Birth of an Empire: The State of Qin, Revisited . New Perspectives on Chinese Culture and Society. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013.

Stimulating presentation of papers presented at a 2008 conference at the Institute for Advanced Study, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, reflects the varying interpretations of recent archeological finds and how those are generating interesting and sometimes controversial reassessments of the history and impact of the pre-Qin and Qin periods. The many authors included here often differ considerably in their interpretations of the data, while the editors’ essays provide structure with useful essays on the larger thematic issues.

Pirazzoli-t’Serstevens, Michèle. The Han Dynasty . Translated from the French by Janet Seligman. New York: Rizzoli International, 1982.

Also published as The Han Civilisation of China (Oxford: Phaidon, 1982). A narrative of the Han empire, from the Qin legacy to diverse topics including state resources, taxation, and the military; the distribution of wealth, and the role of different social classes. In-depth coverage includes the tombs at Mawangdui and Han religious beliefs, technological achievements, Han interaction with the Xiongnu to its north and with the tribes of southwest China. Also covered are aspects of urban and court life, as are Han legacies in science, technology, and art.

Wang Xueli 王学理 and Liang Yun 梁云. Qin wenhua (秦文化). Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe, 2001.

A readable, popular presentation of Qin history and archaeology. Key discoveries organized by decade help the reader to understand the evolving interests and priorities in historical and archaeological research against the changing political and social background of modern China. No English abstract.

Wang, Zhongshu. Han Civilization . Translated by K. C. Chang and collaborators. New Haven, CT, and London: Yale University Press, 1982.

Presents a wealth of detailed information about Han history and archaeology, from the spectacular to the mundane, based on lectures Wang presented in the United States in 1979 (originally published as Wang Zhongshu 王仲殊, Han dai kaoguxue gaishuo 汉代考古学概说 [Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, 1984]). Ample black-and-white illustrations, although much better images of many objects are available elsewhere. Photo captions are unfortunately brief and unsourced.

Yang, Xiaoneng, ed. New Perspectives on China’s Past: Chinese Archaeology in the Twentieth Century . 2 vols. New Haven, CT, and Kansas City: Yale University Press in association with Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2004.

A sweeping and visually stunning presentation of archaeological discoveries in China. Richard Barnhart’s essay exploring possible cultural and artistic connections between the Qin empire and the classical world is fascinating. Particularly useful are entries on the predynastic Qin capital site of Yongcheng 雍城 (677–383 BCE ) and the tombs of the Dukes of Qin at Fengxiang 鳳翔, as well as concise coverage of the most important sites from the Qin and Han periods.

Zhao Huacheng 赵化成 and Gao Chongwen 高崇文. Qin Han kaogu 秦汉考古. Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe, 2002.

Readable volume presents all the major archaeological discoveries of the Qin and Han capital cities, imperial and elite tombs (and, usefully, a discussion of medium and small Han tombs from various parts of China), specific artifact categories (Han sculpture and decorated tomb bricks, wall paintings, silk paintings, bronzes, lacquer, and textiles), and newly discovered Qin and Han texts on cloth, wood, and bamboo from the border regions.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Chinese Studies »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- 1989 People's Movement

- Agricultural Technologies and Soil Sciences

- Agriculture, Origins of

- Ancestor Worship

- Anti-Japanese War

- Architecture, Chinese

- Assertive Nationalism and China's Core Interests

- Astronomy under Mongol Rule

- Book Publishing and Printing Technologies in Premodern Chi...

- Buddhist Monasticism

- Buddhist Poetry of China

- Budgets and Government Revenues

- Calligraphy

- Central-Local Relations

- Chiang Kai-shek

- Children’s Culture and Social Studies

- China and Africa

- China and Peacekeeping

- China and the World, 1900-1949

- China's Agricultural Regions

- China’s Soft Power

- China’s West

- Chinese Alchemy

- Chinese Communist Party Since 1949, The

- Chinese Communist Party to 1949, The

- Chinese Diaspora, The

- Chinese Nationalism

- Chinese Script, The

- Christianity in China

- Classical Confucianism

- Collective Agriculture

- Concepts of Authentication in Premodern China

- Confucius Institutes

- Consumer Society

- Contemporary Chinese Art Since 1976

- Criticism, Traditional

- Cross-Strait Relations

- Cultural Revolution

- Daoist Canon

- Deng Xiaoping

- Dialect Groups of the Chinese Language

- Disability Studies

- Drama (Xiqu 戏曲) Performance Arts, Traditional Chinese

- Dream of the Red Chamber

- Economic Reforms, 1978-Present

- Economy, 1895-1949

- Emergence of Modern Banks

- Energy Economics and Climate Change

- Environmental Issues in Contemporary China

- Environmental Issues in Pre-Modern China

- Establishment Intellectuals

- Ethnicity and Minority Nationalities Since 1949

- Ethnicity and the Han

- Examination System, The

- Fall of the Qing, 1840-1912, The

- Falun Gong, The

- Family Relations in Contemporary China

- Fiction and Prose, Modern Chinese

- Film, Chinese Language

- Film in Taiwan

- Financial Sector, The

- Five Classics

- Folk Religion in Contemporary China

- Folklore and Popular Culture

- Foreign Direct Investment in China

- Gender and Work in Contemporary China

- Gender Issues in Traditional China

- Great Leap Forward and the Famine, The

- Guomindang (1912–1949)

- Han Expansion to the South

- Health Care System, The

- Heterodox Sects in Premodern China

- Historical Archaeology (Qin and Han)

- Hukou (Household Registration) System, The

- Human Origins in China

- Human Resource Management in China

- Human Rights in China

- Imperialism and China, c. 1800-1949

- Industrialism and Innovation in Republican China

- Innovation Policy in China

- Intellectual Trends in Late Imperial China

- Islam in China

- Journalism and the Press

- Judaism in China

- Labor and Labor Relations

- Landscape Painting

- Language, The Ancient Chinese

- Language Variation in China

- Late Imperial Economy, 960–1895

- Late Maoist Economic Policies

- Law in Late Imperial China

- Law, Traditional Chinese

- Li Bai and Du Fu

- Liang Qichao

- Literati Culture

- Literature Post-Mao, Chinese

- Literature, Pre-Ming Narrative

- Liu, Zongzhou

- Local Elites in Ming-Qing China

- Local Elites in Song-Yuan China

- Macroregions

- Management Style in "Chinese Capitalism"

- Marketing System in Pre-Modern China, The

- Marxist Thought in China

- Material Culture

- May Fourth Movement

- Media Representation of Contemporary China, International

- Medicine, Traditional Chinese

- Medieval Economic Revolution

- Middle-Period China

- Migration Under Economic Reform

- Ming and Qing Drama

- Ming Dynasty

- Ming Poetry 1368–1521: Era of Archaism

- Ming Poetry 1522–1644: New Literary Traditions

- Ming-Qing Fiction

- Modern Chinese Drama

- Modern Chinese Poetry

- Modernism and Postmodernism in Chinese Literature

- Music in China

- Needham Question, The

- Neo-Confucianism

- Neolithic Cultures in China

- New Social Classes, 1895–1949

- One Country, Two Systems

- Opium Trade

- Orientalism, China and

- Palace Architecture in Premodern China (Ming-Qing)

- Paleography

- People’s Liberation Army (PLA), The

- Philology and Science in Imperial China

- Poetics, Chinese-Western Comparative

- Poetry, Early Medieval

- Poetry, Traditional Chinese

- Political Art and Posters

- Political Dissent

- Political Thought, Modern Chinese

- Polo, Marco

- Popular Music in the Sinophone World

- Population Dynamics in Pre-Modern China

- Population Structure and Dynamics since 1949

- Porcelain Production

- Post-Collective Agriculture

- Poverty and Living Standards since 1949

- Printing and Book Culture

- Prose, Traditional

- Qing Dynasty up to 1840

- Regional and Global Security, China and

- Religion, Ancient Chinese

- Renminbi, The

- Republican China, 1911-1949

- Revolutionary Literature under Mao

- Rural Society in Contemporary China

- School of Names

- Silk Roads, The

- Sino-Hellenic Studies, Comparative Studies of Early China ...

- Sino-Japanese Relations Since 1945

- Social Welfare in China

- Sociolinguistic Aspects of the Chinese Language

- Su Shi (Su Dongpo)

- Sun Yat-sen and the 1911 Revolution

- Taiping Civil War

- Taiwanese Democracy

- Technology Transfer in China

- Television, Chinese

- Terracotta Warriors, The

- Tertiary Education in Contemporary China

- Texts in Pre-Modern East and South-East Asia, Chinese

- The Economy, 1949–1978

- The Shijing詩經 (Classic of Poetry; Book of Odes)

- Township and Village Enterprises

- Traditional Historiography

- Transnational Chinese Cinemas

- Tribute System, The

- Unequal Treaties and the Treaty Ports, The

- United States-China Relations, 1949-present

- Urban Change and Modernity

- Vernacular Language Movement

- Village Society in the Early Twentieth Century

- Warlords, The

- Water Management

- Women Poets and Authors in Late Imperial China

- Xi, Jinping

- Yan'an and the Revolutionary Base Areas

- Yuan Dynasty

- Yuan Dynasty Poetry

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.80.151.9]

- 185.80.151.9

Visiting Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion?

You must join the virtual exhibition queue when you arrive. We may not admit visitors near the end of the day.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

Qin dynasty (221–206 b.c.).

Department of Asian Art , The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 2000

Previously a minor state in the northwest, Qin had seized the territories of small states on its south and west borders by the mid-third century B.C., pursuing a harsh policy aimed at the consolidation and maintenance of power. Soon thereafter, Ying Zheng (259–210 B.C.), who would reunite China , came to the Qin throne as a boy of nine. He captured the remaining six of the “warring states,” expanding his rule eastward and as far south as the Yangzi River, and proclaimed himself First Emperor of the Qin, or Qin Shihuangdi. Qin, pronounced chin , is the source of the Western name China.

Throughout his rule, Qin Shihuang continued to extend the empire, eventually reaching as far south as Vietnam. His vast empire was divided into commanderies and prefectures administered jointly by civil and military officials under the direction of a huge central bureaucracy. This administrative structure served as a model for government in China until the collapse of the Qing dynasty in 1911. Qin Shihuang also standardized the Chinese script, currency, and system of measurements, and expanded the network of roads and canals. He is credited with building the Great Wall of China by uniting several preexisting defensive walls on the northern frontier; and reviled for a state-sponsored burning of Confucian works and other classics in 213 B.C.

Excavations begun in 1974 brought to light over 7,000 lifesize terracotta figures from the vast army guarding the tomb of Qin Shihuang, one of the most spectacular archaeological discoveries in Mainland China. Although his tomb chamber has not yet been unearthed, historical records describe it as a microcosm of his realm, with constellations painted on the ceiling and running rivers made of mercury.

Department of Asian Art. “Qin Dynasty (221–206 B.C.).” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/qind/hd_qind.htm (October 2000)

Additional Essays by Department of Asian Art

- Department of Asian Art. “ Mauryan Empire (ca. 323–185 B.C.) .” (October 2000)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Zen Buddhism .” (October 2002)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Chinese Cloisonné .” (October 2004)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Chinese Gardens and Collectors’ Rocks .” (October 2004)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Landscape Painting in Chinese Art .” (October 2004)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Nature in Chinese Culture .” (October 2004)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Han Dynasty (206 B.C.–220 A.D.) .” (October 2000)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Kushan Empire (ca. Second Century B.C.–Third Century A.D.) .” (October 2000)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Rinpa Painting Style .” (October 2003)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Jōmon Culture (ca. 10,500–ca. 300 B.C.) .” (October 2002)

- Department of Asian Art. “ The Kano School of Painting .” (October 2003)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Woodblock Prints in the Ukiyo-e Style .” (October 2003)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Traditional Chinese Painting in the Twentieth Century .” (October 2004)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) .” (October 2002)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127) .” (October 2001)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Period of the Northern and Southern Dynasties (386–581) .” (October 2002)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279) .” (October 2001)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Tang Dynasty (618–907) .” (October 2001)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Yayoi Culture (ca. 300 B.C.–300 A.D.) .” (October 2002)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368) .” (October 2001)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Art of the Pleasure Quarters and the Ukiyo-e Style .” (October 2004)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Scholar-Officials of China .” (October 2004)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Kofun Period (ca. 300–710) .” (October 2002)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Shunga Dynasty (ca. Second–First Century B.C.) .” (October 2000)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Lacquerware of East Asia .” (October 2004)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Painting Formats in East Asian Art .” (October 2004)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Asuka and Nara Periods (538–794) .” (October 2002)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Heian Period (794–1185) .” (October 2002)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Kamakura and Nanbokucho Periods (1185–1392) .” (October 2002)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Momoyama Period (1573–1615) .” (October 2002)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Neolithic Period in China .” (October 2004)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Muromachi Period (1392–1573) .” (October 2002)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Samurai .” (October 2002)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Shinto .” (October 2002)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Seasonal Imagery in Japanese Art .” (October 2004)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Shang and Zhou Dynasties: The Bronze Age of China .” (October 2004)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Shōguns and Art .” (October 2004)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Art of the Edo Period (1615–1868) .” (October 2003)

Related Essays

- Han Dynasty (206 B.C.–220 A.D.)

- Shang and Zhou Dynasties: The Bronze Age of China

- Ming Dynasty (1368–1644)

- Music and Art of China

- Neolithic Period in China

- Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127)

- Period of the Northern and Southern Dynasties (386–581)

- The Qing Dynasty (1644–1911): Painting

- Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279)

- Tang Dynasty (618–907)

- Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368)

- China, 1000 B.C.–1 A.D.

- Qin Dynasty (ca. 206 B.C.)

- Archaeology

- Chinese Literature / Poetry

- Funerary Art

- Literature / Poetry

- Painted Object

- Qing Dynasty

- Sculpture in the Round

- Warring States Period

- Weights and Measures

The History of Chinese Literature

Writing in China dates back to the hieroglyphs that were used in the Shang Dynasty of 1700 – 1050 BC. Chinese literature is a vast subject that spans thousands of years. One of the interesting things about Chinese literature is that much of the serious literature was composed using a formal written language that is called Classical Chinese .

The best literature of the Yuan Dynasty era and the four novels that are considered the greatest classics are important exceptions.

However, even during the Qing Dynasty of two hundred years ago, most writers composed in a literary stream that extended back about 2,400 years. They studied very ancient writings in more or less the original written language. This large breadth of time with so many writers living in the various eras and countries makes Chinese literature complex.

Chinese literary works include fiction , philosophical and religious works, poetry, and scientific writings . The dynastic eras frame the history of Chinese literature and are examined one by one.

The grammar of the written Classical Language is different than the spoken languages of the past two thousand years.

This written language was used by people of many different ethnic groups and countries during the Zhou, Qin and Han eras spanning 1050 BC to 220 AD. After the Han Dynasty, the written language evolved as the spoken languages changed, but most writers still based their compositions on Classical Chinese.

However, this written language wasn't the vernacular language even two thousand years ago. The empires and groups of kingdoms of all these eras were composed of people speaking many different native languages . If Europe had a literary history like China's, it would be as if most European writers until the 20th century always tried to write in ancient Classical Greek that became a dead language more than two millennia ago.

Shang Dynasty (about 1700-1050 BC) — Development of Chinese Writing

The first dynasty for which there is historical record and archaeological evidence is the Shang Dynasty. It was a small empire in northern central China. No documents from that country survive, but there are archaeological finds of hieroglyphic writing on bronze wares and oracle bones. The hieroglyphic writing system later evolved into ideographic and partly-phonetic Chinese characters.

Zhou Dynasty (1045-255 BC) — Basic Philosophical and Religious Literature

The Zhou Dynasty was contemporaneous with the Shang Dynasty, and then they conquered the Shang Dynasty. Their dynasty lasted for about 800 years, but for most of the time, their original territory was broken up into dozens of competing kingdoms, and these finally coalesced into several big and warring kingdoms by the end of the Zhou era.

The great literary works of philosophy and religion that became the basis for Chinese religious and social belief stem from what is called the Spring and Autumn Period (770-476) and the Warring States Period (475-221). Taoism, Confucian literature , and other prominent religious and philosophical schools all emerged during these two periods.

The Chinese call this simultaneous emergence of religions and philosophies the "One Hundred Schools of Thought." Perhaps so many philosophers could write simultaneously because they lived in small kingdoms that supported them.

In Chinese history, the dominant rulers generally squelch or discourage philosophical expression that contradict their own, so when there were several small powers, different schools of thought could survive in the land at the same time.

The major literary achievements of the Confucian Classics, early Taoist writings, and other important prose works originated in the late Spring and Autumn Period and the Warring States Period of the Zhou Dynasty era. These literary works deeply shaped Chinese philosophy and religion .

Confucius is said to have edited a history of the Spring and Autumn Period called the Spring and Autumn Annals (春秋) that shapes Chinese thinking about its history.

There were hundreds of philosophers and writers who wrote conflicting documents, and there was discussion and communication. What we know of the literature of this period was mainly preserved after the Qin Dynasty's book burning and from a few recent archeological finds of records.

Probably most of the philosophical and religious works of that time were destroyed. If there were great fictional books created, they have been lost. So the main contributions of this period to Chinese literature were the prose works of the Confucian Classics and the Taoist writings, and preserved poems and songs.

Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC) — Literary Disaster and Legalism

At the end of the Zhou Dynasty era that is called the Warring States Period, of the surviving few big states in the land, the Qin Dynasty became the most powerful.

The Qin Dynasty had big armies and conquered the others. Once the Qin emperor had control, he wanted to keep it, and they squelched any opposition to his authority. In the conquered territories, there were teachers of many different doctrines and religions . A big philosophical and religious school then was called Mohism. They were particularly attacked by the Qin Dynasty, and little is known about it.

An early form of Buddhism was also established in China at that time, but their temples and literature were destroyed and even less is known about them. The emperor wanted to reduce the One Hundred Schools of Thought to one that he approved. He ordered the destruction of most books all over the empire . He even killed many Confucian philosophers and teachers . He allowed books on scientific subjects like medicine or agriculture to survive. So the "Book Burning and Burial of Scholars" was a literary disaster.

On the other hand, the Qin Dynasty standardized the written Classical Language . It is said that a minister of the Qin emperor named Li Si introduced a writing system that later developed into modern Chinese writing. Standardization was meant to help control the society. The standardized writing system also helped people all over the country to communicate more clearly.

The Qin Emperor favored a philosophical school that was called Legalism (法家). This philosophy of course justified the strong control of the emperor and maintained that everyone should obey him. It is thought that Li Si taught that human nature was naturally selfish and that a strong emperor government with strict laws was needed for social order .

Li Si's writings on politics and law and his propagation of this school much influenced the political thinking in the Han Dynasty and later eras. Legalism texts and the standardization of writing were the Qin Dynasty era's literary contributions.

Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD) — Scientific and Historical Texts

A former peasant leader overthrew the Qin Empire. The Han Dynasty era lasted for 400 years. At the beginning of the era, Confucianism was revived . Confucian texts were rewritten and republished. Confucianism was mixed with the Legalism philosophy of Li Si. The resulting ideology was the official ideology of the Han Dynasty and influenced political thinking afterwards. The era's major contributions were historical texts and scientific works.

Sima Qian wrote Historical Records that is a major history concerning the overall history of China from before the Shang Dynasty until the Han Dynasty. The book's prose was considered a model for writers in succeeding dynastic eras. Another important historical text concerned the Han Dynasty itself.

Some scientific texts were also thought to be important for their times, thought it doesn't seem that the information was widely known or well known afterwards.

The Han Dynasty era was one of the two main hotspot eras for scientific and technical advance. But printing wasn't available for wide publication of the information . During the Eastern Han Dynasty towards the end of the Han era, the influence of the philosophy of the Confucian Classics that hindered scientific progress was waning. So people were more free to pursue invention.

Cai Lun (50–121) of the imperial court is said to be the first person in the world to create writing paper , and this was important for written communication at the end of the empire. Finery forges were used in steel making. Two or three mathematical texts showing advanced mathematics for the times were written.

The Han Empire disintegrated into warring kingdoms similar to what happened during the Warring States Period before the Qin Dynasty. For several hundred years, dynasties and kingdoms rose and fell in various places, and the next big and long-lasting dynastic empire is called the Tang Dynasty.

Tang Dynasty (618-907) — Early Woodblock Printing and Poetry

The Tang Dynasty had a big empire that benefited from trade with the west along the Silk Road , battled with the Tibetan Empire, and experienced the growing influence of organized Buddhist religions. This era's main contribution to Chinese literature was in the poetry of Dufu, Li Bai and many other poets. Dufu and Li Bai are often thought of as China's greatest poets.

Li Bai (701–762) was one of the greatest romantic poets of ancient China. He wrote at least a thousand poems on a variety of subjects from political matters to natural scenery.

Du Fu (712-770 AD) also wrote more than a thousand poems. He is thought of as one of the greatest realist poets of China. His poems reflect the hard realities of war, dying people living next to rich rulers, and primitive rural life. He was an official in the Tang capital of Chang An, and he was captured when the capital was attacked. He took refuge in Chengdu that is a city in Sichuan Province. It is thought that he lived in a simple hut where he wrote many of his best realist poems. Perhaps more than 1,400 of his poems survive, and his poetry is still read and appreciated by modern Chinese people.

Song Dynasty (960-1279) — Early Woodblock Printing, Travel Literature, Poetry, Scientific Texts and the Neo-Confucian Classics

The next dynasty is called the Song Dynasty. It was weaker than the Tang Dynasty, but the imperial government officials made remarkable scientific and technical advances .

Military technology greatly advanced. They traded little with the west due to the presence of warring Muslim states on the old trade routes. There wasn't territorial expansion, but the empire was continuously attacked by nomadic tribes and countries around them. Their northern territory was invaded, and they were forced to move their capital to southern China.

So the era is divided into two eras called the Northern Song (960-1127) and Southern Song (1127-1279) eras.

One of the era's technological accomplishments was the invention of movable type about the turn of 2nd millennia during the Northern Song period. This helped to spread knowledge since printed material could be published more quickly and cheaply .

Travel literature in which authors wrote about their trips and about various destinations became popular perhaps because the texts could be cheaply bought. The Confucian Classics were codified and used as test material for the entrance examination into the elite bureaucracy, advanced scientific texts and atlases were published, and important poems were written.

The Confucian Classics were important in China's history because from the Song Dynasty onwards, they were the texts people needed to know in order to pass an examination for the bureaucracy of China.

These Confucian Classics were the Five Classics that were thought to have been penned by Confucius and the Four Books that were thought to contain Confucius-related material but were compiled during the Southern Song era. The Four Books and Five Classics (四書五經) were basically memorized by those who did the best on the exams.

In this way, Confucianism, as codified during the Song era, became the dominant political philosophy of the several empires until modern times .

Since the bureaucrats all studied the same works on social behavior and philosophy, this promoted unity and the normalization of behavior throughout each empire and during dynastic changes. The scholar-bureaucrats had a common base of understanding, and they passed on these ideas to the people under them. Those who passed the difficult exams were highly respected even if they didn't receive a ruling post. High education in this system was thought to produce nobility .

The Five Classics and Four Books were written in the written Classical Language.

The Five Classics include : The Book of Changes , The Classic of Poetry , The Record of Rites that was a recreation of the original Classic of Rites of Confucius that was lost in the Qin book purge, The Classic of History , and The Spring and Autumn Annals that was mainly a historical record of Confucius' native state of Lu.

The Four Books include : The Analects of Confucius that is a book of pithy sayings attributed to Confucius and recorded by his disciples; Mencius that is a collection of political dialogues attributed to Mencius; The Doctrine of the Mean ; and The Great Learning that is a book about education, self-cultivation and the Dao. For foreigners who want a taste of this Confucian philosophy, reading the Analects of Confucius is a good introduction since the statements are usually simple and like common sense.

Another period of scientific progress and technical invention was the Song era . Song technicians seemed to have made a lot of advancements in mechanical engineering. They made advanced contraptions out of gears, pulleys and wheels. These were used to make big clocks, a mechanical odometer on animal drawn carts that marked land distance by making noise after traveling a certain distance, and other advanced instruments. The Song technicians also invented many uses gunpowder including rockets, explosives and big guns.

The imperial court officials did remarkable scientific research in many areas of mechanics and science. Shen Kuo (1031–1095) and Su Song (1020–1101) both wrote scientific treatises about their research and about different fields.

Shen is said to have discovered the concepts of true north and magnetic declination towards the North Pole. He also described the magnetic needle compass . If Chinese sailors knew about this work, they could have sailed long distances more accurately. This knowledge would predate European discovery. He did advanced astronomical research for his time.

Su Song wrote a treatise called the Bencao Tujing with information on medicine, botany and zoology. He also was the author of a large celestial atlas of five different star maps, and he also made land atlases. Su Song was famous for his hydraulic-powered astronomical clock tower. Su's clock tower is said to have had an endless power-transmitting chain drive that he described in a text on clock design and astronomy that was published in 1092. If this is so, it may be the first time such a device was used in the world. When the Southern Song Empire was conquered by the Mongols, these inventions and the astronomical knowledge may have been forgotten.

Another contribution to the literature of China was the poetry of the Song era. A Southern Song poet named Lu is thought to have written almost 10,000 poems. Su Tungpo is regarded as a great poet of the Northern Song era. Here is a stanza he wrote:

The moon rounds the red mansion Stoops to silk-pad doors Shines upon the sleepless Bearing no grudge Why does the moon tend to be full when people are apart?

Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368) — Drama and Great Fictional Novels

The Mongols were nomadic people who herded cattle north of the Tang Empire and wandered over a large area fighting on horseback. They believed that they might be able to conquer the world. They easily conquered Persia far to the west.

It was a big empire with high technology , a big population and a big army . Then they decided to try to conquer all the countries around them.

They attacked the Tang Dynasty, the Dali Kingdom in Yunnan, and much of Asia, and they formed the biggest empire in the history of the earth until then. They conquered Russia, a part of eastern Europe and a part of the Middle East.

In China, the Mongols established the very rich Yuan Dynasty. In their camps, the Mongols were entertained by shadow puppet plays in which a lamp cast the shadows of little figurines and puppets on a screen or sheet. In the Yuan Dynasty, puppet drama continued to entertain the rich dynastic courts in vernacular language.