Pros and Cons of Case Studies Psychology

In the world of psychology, case studies have long been a go-to method for understanding human behavior. These in-depth examinations offer a glimpse into the complexities of individuals' lives, shedding light on the unique circumstances that shape their thoughts and actions.

However, like any research approach, case studies come with their own set of pros and cons. From providing rich qualitative data to potential limitations in generalizability, this article explores the various aspects of case studies in psychology.

Key Takeaways

- Case studies provide in-depth and detailed information.

- Case studies capture the richness and complexity of individual experiences.

- Case studies have limitations such as small sample sizes and lack of control over variables.

- Case studies require ethical considerations such as informed consent and confidentiality of participants' information.

Strengths of Case Studies in Psychology

In the field of psychology, researchers have found numerous strengths associated with case studies. Case studies provide a unique opportunity to deeply explore and understand individual experiences and behaviors. By focusing on a single case or a small number of cases, researchers are able to gather detailed information and gain a comprehensive understanding of complex phenomena.

One of the main strengths of case studies is their ability to provide in-depth and detailed information. Unlike other research methods that rely on statistical analysis and generalizations, case studies allow researchers to capture the richness and complexity of individual experiences. This level of detail can provide valuable insights into the intricacies of human behavior and the factors that influence it.

Another strength of case studies is their flexibility. Researchers have the freedom to tailor the study design to the specific research question and explore multiple variables simultaneously. This flexibility allows for a more holistic understanding of the phenomenon under investigation.

Additionally, case studies can be particularly useful when studying rare or unusual conditions. Since these conditions are often difficult to replicate or observe in a laboratory setting, case studies offer a valuable opportunity to gain insights that may otherwise be inaccessible.

Limitations of Case Studies in Psychology

One of the main limitations of case studies in psychology is that they're based on a small sample size, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Since case studies typically involve in-depth analysis of a single individual or a small group, the results may not be applicable to a larger population. This can limit the external validity of the findings and make it difficult to draw broader conclusions about human behavior.

In addition to the limited generalizability, case studies also have other limitations that should be considered:

- Lack of control: Case studies rely on observational data, which means that researchers have little control over the variables being studied. This lack of control makes it difficult to establish cause-and-effect relationships or determine the exact factors that may be influencing the outcomes.

- Subjectivity: Case studies often rely on subjective interpretations of data, which can introduce bias into the findings. Researchers may have preconceived notions or personal beliefs that can influence their analysis and interpretation of the data.

- Time-consuming and costly: Conducting a case study requires a significant investment of time and resources. Researchers must spend considerable time collecting and analyzing data, which can be both time-consuming and costly.

Despite these limitations, case studies can still provide valuable insights into specific phenomena and offer a rich and detailed understanding of individual experiences. However, it's important to interpret the findings with caution and consider the limitations inherent in this research method.

Validity Issues in Case Studies

Despite their limitations, case studies can provide valuable insights into specific phenomena, as well as offer a rich and detailed understanding of individual experiences. However, it is important to consider the validity issues that may arise when using case studies in psychological research. Validity refers to the degree to which a study measures what it claims to measure and the extent to which the results can be generalized to the larger population.

One validity issue in case studies is external validity, which refers to the generalizability of the findings to other individuals or situations. Due to the small sample size and unique characteristics of the individuals studied, it can be challenging to generalize the findings to a larger population. Another validity concern is internal validity, which refers to the accuracy of the conclusions drawn from the study. Potential confounding variables, researcher bias, and lack of control can all impact the internal validity of a case study.

Lastly, construct validity is another important consideration. This refers to the degree to which the study accurately measures the intended constructs or variables. In case studies, there may be challenges in accurately measuring and operationalizing the variables of interest, leading to potential issues with construct validity.

Ethical Considerations in Case Studies

Researchers must carefully consider ethical considerations when conducting case studies in psychology to ensure the well-being and rights of the participants are protected. Case studies involve in-depth examination of individuals or small groups, often over a long period of time. This level of involvement can raise ethical concerns, and researchers must take steps to mitigate any potential harm to participants.

Ethical considerations in case studies include:

- Informed consent: Researchers must obtain informed consent from participants, ensuring they understand the purpose of the study, potential risks, and their right to withdraw at any time.

- Confidentiality: Participants' identities and personal information should be kept confidential unless they provide explicit consent for disclosure.

- Debriefing: Researchers must provide a debriefing session after the study, explaining any deception used and addressing any concerns or emotional distress experienced by participants.

Sample Size and Generalizability in Case Studies

A researcher must take into consideration the sample size and generalizability in case studies to ensure the findings can be applied to a larger population.

Sample size refers to the number of cases or participants included in a study. In case studies, the sample size is often small, consisting of a single case or a small group of cases. This limited sample size can be a disadvantage as it may not accurately represent the diversity and variability of the larger population.

For example, if a case study examines the effects of a therapeutic intervention on a single individual, the findings may not be applicable to the general population as the sample size is too small to draw broad conclusions.

Generalizability refers to the extent to which the findings of a study can be applied to other populations or situations. In case studies, generalizability is often limited due to the unique characteristics of the cases being studied. Each case is highly individualized and specific, which makes it difficult to generalize the findings to a larger population.

For example, if a case study examines the experiences of a child with autism in a specific educational setting, the findings may not be applicable to all children with autism in different educational settings.

Despite these limitations, case studies can still provide valuable insights and generate hypotheses for further research. They often serve as a starting point for more extensive studies with larger sample sizes, allowing for more generalizable conclusions to be drawn.

Researchers must carefully consider the sample size and generalizability in case studies to ensure the findings are valid and applicable to a larger population.

Time and Resource Constraints in Case Studies

Time and resource constraints in case studies present several challenges.

Firstly, the limitations of data collection may arise due to the limited time available for gathering information from participants.

This can potentially affect the depth and breadth of data obtained, impacting the overall validity of the research.

Therefore, researchers must carefully balance efficiency and accuracy when conducting case studies to ensure that valuable insights are gained within the given constraints.

Limitations of Data Collection

Unfortunately, collecting data for case studies can be challenging due to limited resources and time constraints. This can significantly impact the quality and depth of information that can be gathered.

Here are some limitations of data collection in case studies:

- Limited sample size: Case studies often involve a small number of participants, making it difficult to generalize the findings to a larger population.

- Biased data: The data collected in case studies may be influenced by the researcher's subjective interpretation or preconceived notions, leading to potential bias.

- Lack of control: Unlike experimental studies, case studies lack control over variables, which can make it challenging to establish cause-and-effect relationships.

These limitations highlight the importance of considering the constraints of time and resources when conducting case studies and interpreting their findings. Researchers must carefully balance the need for in-depth analysis with the practical limitations of data collection.

Impact on Research Validity

Due to time and resource constraints, researchers often face challenges in maintaining the validity of their case study research. Conducting a case study requires a significant investment of time and resources, as it involves collecting detailed data from a limited number of participants or cases.

This can be a time-consuming process, especially when researchers need to establish rapport with participants, conduct interviews, observe behaviors, and analyze data. Additionally, case studies often require researchers to have specialized knowledge and skills in order to accurately interpret the data collected.

However, due to limited resources and time constraints, researchers may not be able to gather as much data as they'd like or thoroughly analyze the data they've collected. This can lead to potential biases or limitations in the findings, which can impact the overall validity of the research.

Therefore, researchers must carefully consider the trade-offs between time, resources, and the desired level of research validity when conducting case studies.

Balancing Efficiency and Accuracy

Researchers often face the challenge of balancing efficiency and accuracy in case studies, as they navigate time and resource constraints. Conducting a thorough case study requires ample time and resources to collect and analyze data effectively. However, researchers often encounter limitations that make it difficult to achieve both efficiency and accuracy.

Here are three sub-lists that highlight the key considerations in balancing efficiency and accuracy in case studies:

- Time Constraints:

- Limited time for data collection and analysis

- Pressure to meet deadlines and produce results quickly

- Potential compromise on the depth of analysis due to time limitations

- Resource Constraints:

- Limited funding for research projects

- Lack of access to necessary tools and equipment

- Insufficient personnel to gather and analyze data comprehensively

- Trade-offs:

- Prioritizing certain aspects of the study over others

- Making compromises between the level of detail and overall breadth of the study

- Striking a balance between efficiency and accuracy based on the available resources and time constraints

Finding the right balance between efficiency and accuracy is crucial in case studies, as it influences the quality and reliability of the research findings. Researchers must carefully consider these constraints and make informed decisions to maintain the integrity of their studies while working within limitations.

Alternative Research Methods in Psychology

One alternative research method in psychology that researchers often employ is called experimental design. This method involves manipulating one or more variables to observe their effect on another variable, while controlling for extraneous variables. Experimental design allows researchers to establish cause-and-effect relationships and test hypotheses in a controlled setting.

Experimental design offers several advantages in psychological research. It allows researchers to have control over variables, which helps establish cause-and-effect relationships. Furthermore, it provides quantitative data, allowing for statistical analysis and replication. This method also has the potential to lead to the development of effective interventions for psychological issues. However, there are some limitations to experimental design. The results may not generalize to real-world settings due to the controlled nature of the study. Ethical concerns may also arise when manipulating variables. Additionally, experimental design can be time-consuming and resource-intensive, and it may be challenging to control all extraneous variables. Consequently, the ecological validity of the findings may be limited.

Frequently Asked Questions

How are case studies in psychology different from other research methods.

Case studies in psychology differ from other research methods in their focus on in-depth analysis of a single individual or small group. This allows for a detailed understanding of complex phenomena, but limits generalizability to larger populations.

What Are Some Examples of Famous Case Studies in Psychology?

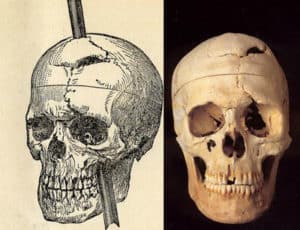

Famous case studies in psychology have provided valuable insights. For example, the case of Phineas Gage helped understand brain function. The Little Albert experiment shed light on classical conditioning. These studies continue to shape our understanding of human behavior.

How Do Researchers Ensure the Confidentiality of Participants in Case Studies?

Researchers ensure participant confidentiality in case studies by obtaining informed consent, anonymizing data, and storing it securely. They follow ethical guidelines and ensure that participants' identities are protected, maintaining the trust and privacy of those involved.

Are There Any Legal Requirements or Guidelines That Researchers Must Follow When Conducting Case Studies?

Researchers must follow legal requirements and guidelines when conducting case studies. These ensure ethical treatment of participants, such as obtaining informed consent, maintaining confidentiality, and protecting privacy. Failure to comply can result in legal consequences.

How Do Researchers Determine the Appropriate Sample Size for a Case Study in Psychology?

Researchers determine the appropriate sample size for a case study in psychology by considering factors such as the research question, available resources, and the desired level of statistical power.

Related posts:

- Pros and Cons of Positive Psychology

- Pros and Cons of Psychology

- Pros and Cons of Evolutionary Psychology

- 10 Pros and Cons of Evidence Based Practice in Psychology

- Pros and Cons of Descriptive Research

- Pros and Cons of Meta Analysis

- Pros and Cons of Primary Research

- Pros and Cons of Being a Case Manager

- Pros and Cons of Scientific Method

- Pros and Cons of Surveys for Research

- Pros and Cons of Being a RN Case Manager

- 20 Intense Pros and Cons of Quantitative Research

- Pros and Cons of Sports Psychology >

- 20 Pros and Cons of Ethnic Studies

- 20 Pros and Cons of Punishment Psychology

- Pros and Cons of Paying Research Participants

- Statistics About Quantitative Research

- Pros and Cons of Statistical Analysis

- 20 Pros and Cons of Hypothesis Testing

- 20 Pros and Cons of Mixed Methods Research

Jordon Layne

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is a Case Study?

Weighing the pros and cons of this method of research

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Cara Lustik is a fact-checker and copywriter.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Cara-Lustik-1000-77abe13cf6c14a34a58c2a0ffb7297da.jpg)

Verywell / Colleen Tighe

- Pros and Cons

What Types of Case Studies Are Out There?

Where do you find data for a case study, how do i write a psychology case study.

A case study is an in-depth study of one person, group, or event. In a case study, nearly every aspect of the subject's life and history is analyzed to seek patterns and causes of behavior. Case studies can be used in many different fields, including psychology, medicine, education, anthropology, political science, and social work.

The point of a case study is to learn as much as possible about an individual or group so that the information can be generalized to many others. Unfortunately, case studies tend to be highly subjective, and it is sometimes difficult to generalize results to a larger population.

While case studies focus on a single individual or group, they follow a format similar to other types of psychology writing. If you are writing a case study, we got you—here are some rules of APA format to reference.

At a Glance

A case study, or an in-depth study of a person, group, or event, can be a useful research tool when used wisely. In many cases, case studies are best used in situations where it would be difficult or impossible for you to conduct an experiment. They are helpful for looking at unique situations and allow researchers to gather a lot of˜ information about a specific individual or group of people. However, it's important to be cautious of any bias we draw from them as they are highly subjective.

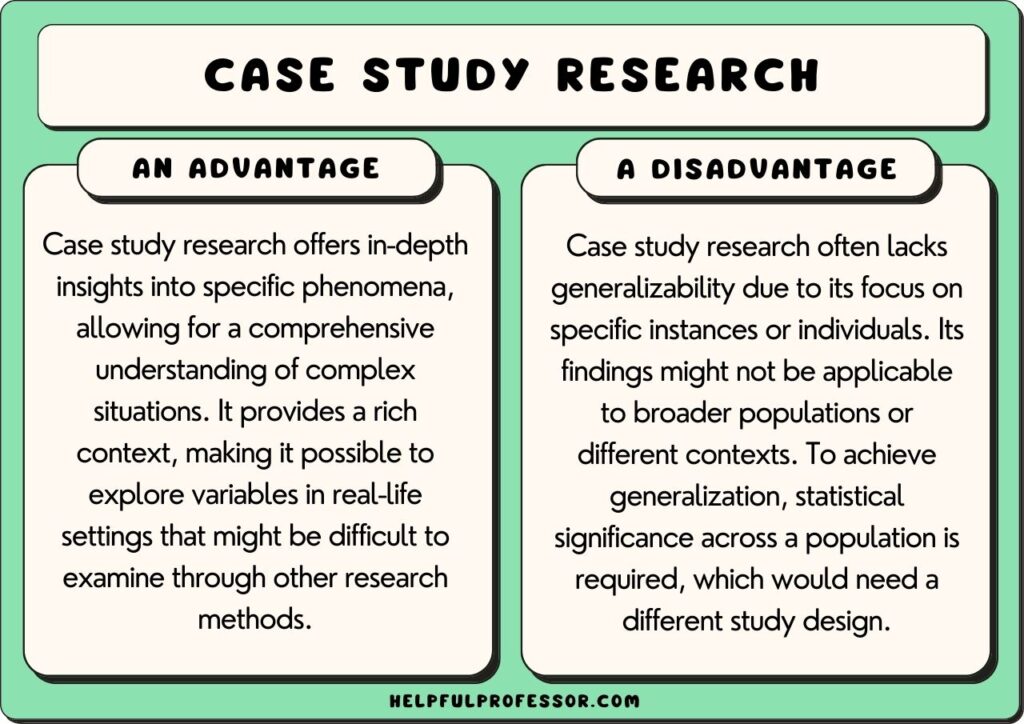

What Are the Benefits and Limitations of Case Studies?

A case study can have its strengths and weaknesses. Researchers must consider these pros and cons before deciding if this type of study is appropriate for their needs.

One of the greatest advantages of a case study is that it allows researchers to investigate things that are often difficult or impossible to replicate in a lab. Some other benefits of a case study:

- Allows researchers to capture information on the 'how,' 'what,' and 'why,' of something that's implemented

- Gives researchers the chance to collect information on why one strategy might be chosen over another

- Permits researchers to develop hypotheses that can be explored in experimental research

On the other hand, a case study can have some drawbacks:

- It cannot necessarily be generalized to the larger population

- Cannot demonstrate cause and effect

- It may not be scientifically rigorous

- It can lead to bias

Researchers may choose to perform a case study if they want to explore a unique or recently discovered phenomenon. Through their insights, researchers develop additional ideas and study questions that might be explored in future studies.

It's important to remember that the insights from case studies cannot be used to determine cause-and-effect relationships between variables. However, case studies may be used to develop hypotheses that can then be addressed in experimental research.

Case Study Examples

There have been a number of notable case studies in the history of psychology. Much of Freud's work and theories were developed through individual case studies. Some great examples of case studies in psychology include:

- Anna O : Anna O. was a pseudonym of a woman named Bertha Pappenheim, a patient of a physician named Josef Breuer. While she was never a patient of Freud's, Freud and Breuer discussed her case extensively. The woman was experiencing symptoms of a condition that was then known as hysteria and found that talking about her problems helped relieve her symptoms. Her case played an important part in the development of talk therapy as an approach to mental health treatment.

- Phineas Gage : Phineas Gage was a railroad employee who experienced a terrible accident in which an explosion sent a metal rod through his skull, damaging important portions of his brain. Gage recovered from his accident but was left with serious changes in both personality and behavior.

- Genie : Genie was a young girl subjected to horrific abuse and isolation. The case study of Genie allowed researchers to study whether language learning was possible, even after missing critical periods for language development. Her case also served as an example of how scientific research may interfere with treatment and lead to further abuse of vulnerable individuals.

Such cases demonstrate how case research can be used to study things that researchers could not replicate in experimental settings. In Genie's case, her horrific abuse denied her the opportunity to learn a language at critical points in her development.

This is clearly not something researchers could ethically replicate, but conducting a case study on Genie allowed researchers to study phenomena that are otherwise impossible to reproduce.

There are a few different types of case studies that psychologists and other researchers might use:

- Collective case studies : These involve studying a group of individuals. Researchers might study a group of people in a certain setting or look at an entire community. For example, psychologists might explore how access to resources in a community has affected the collective mental well-being of those who live there.

- Descriptive case studies : These involve starting with a descriptive theory. The subjects are then observed, and the information gathered is compared to the pre-existing theory.

- Explanatory case studies : These are often used to do causal investigations. In other words, researchers are interested in looking at factors that may have caused certain things to occur.

- Exploratory case studies : These are sometimes used as a prelude to further, more in-depth research. This allows researchers to gather more information before developing their research questions and hypotheses .

- Instrumental case studies : These occur when the individual or group allows researchers to understand more than what is initially obvious to observers.

- Intrinsic case studies : This type of case study is when the researcher has a personal interest in the case. Jean Piaget's observations of his own children are good examples of how an intrinsic case study can contribute to the development of a psychological theory.

The three main case study types often used are intrinsic, instrumental, and collective. Intrinsic case studies are useful for learning about unique cases. Instrumental case studies help look at an individual to learn more about a broader issue. A collective case study can be useful for looking at several cases simultaneously.

The type of case study that psychology researchers use depends on the unique characteristics of the situation and the case itself.

There are a number of different sources and methods that researchers can use to gather information about an individual or group. Six major sources that have been identified by researchers are:

- Archival records : Census records, survey records, and name lists are examples of archival records.

- Direct observation : This strategy involves observing the subject, often in a natural setting . While an individual observer is sometimes used, it is more common to utilize a group of observers.

- Documents : Letters, newspaper articles, administrative records, etc., are the types of documents often used as sources.

- Interviews : Interviews are one of the most important methods for gathering information in case studies. An interview can involve structured survey questions or more open-ended questions.

- Participant observation : When the researcher serves as a participant in events and observes the actions and outcomes, it is called participant observation.

- Physical artifacts : Tools, objects, instruments, and other artifacts are often observed during a direct observation of the subject.

If you have been directed to write a case study for a psychology course, be sure to check with your instructor for any specific guidelines you need to follow. If you are writing your case study for a professional publication, check with the publisher for their specific guidelines for submitting a case study.

Here is a general outline of what should be included in a case study.

Section 1: A Case History

This section will have the following structure and content:

Background information : The first section of your paper will present your client's background. Include factors such as age, gender, work, health status, family mental health history, family and social relationships, drug and alcohol history, life difficulties, goals, and coping skills and weaknesses.

Description of the presenting problem : In the next section of your case study, you will describe the problem or symptoms that the client presented with.

Describe any physical, emotional, or sensory symptoms reported by the client. Thoughts, feelings, and perceptions related to the symptoms should also be noted. Any screening or diagnostic assessments that are used should also be described in detail and all scores reported.

Your diagnosis : Provide your diagnosis and give the appropriate Diagnostic and Statistical Manual code. Explain how you reached your diagnosis, how the client's symptoms fit the diagnostic criteria for the disorder(s), or any possible difficulties in reaching a diagnosis.

Section 2: Treatment Plan

This portion of the paper will address the chosen treatment for the condition. This might also include the theoretical basis for the chosen treatment or any other evidence that might exist to support why this approach was chosen.

- Cognitive behavioral approach : Explain how a cognitive behavioral therapist would approach treatment. Offer background information on cognitive behavioral therapy and describe the treatment sessions, client response, and outcome of this type of treatment. Make note of any difficulties or successes encountered by your client during treatment.

- Humanistic approach : Describe a humanistic approach that could be used to treat your client, such as client-centered therapy . Provide information on the type of treatment you chose, the client's reaction to the treatment, and the end result of this approach. Explain why the treatment was successful or unsuccessful.

- Psychoanalytic approach : Describe how a psychoanalytic therapist would view the client's problem. Provide some background on the psychoanalytic approach and cite relevant references. Explain how psychoanalytic therapy would be used to treat the client, how the client would respond to therapy, and the effectiveness of this treatment approach.

- Pharmacological approach : If treatment primarily involves the use of medications, explain which medications were used and why. Provide background on the effectiveness of these medications and how monotherapy may compare with an approach that combines medications with therapy or other treatments.

This section of a case study should also include information about the treatment goals, process, and outcomes.

When you are writing a case study, you should also include a section where you discuss the case study itself, including the strengths and limitiations of the study. You should note how the findings of your case study might support previous research.

In your discussion section, you should also describe some of the implications of your case study. What ideas or findings might require further exploration? How might researchers go about exploring some of these questions in additional studies?

Need More Tips?

Here are a few additional pointers to keep in mind when formatting your case study:

- Never refer to the subject of your case study as "the client." Instead, use their name or a pseudonym.

- Read examples of case studies to gain an idea about the style and format.

- Remember to use APA format when citing references .

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011;11:100.

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011 Jun 27;11:100. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

Gagnon, Yves-Chantal. The Case Study as Research Method: A Practical Handbook . Canada, Chicago Review Press Incorporated DBA Independent Pub Group, 2010.

Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods . United States, SAGE Publications, 2017.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Understanding Case Study Method in Research: A Comprehensive Guide

Table of Contents

Have you ever wondered how researchers uncover the nuanced layers of individual experiences or the intricate workings of a particular event? One of the keys to unlocking these mysteries lies in the qualitative research focusing on a single subject in its real-life context.">case study method , a research strategy that might seem straightforward at first glance but is rich with complexity and insightful potential. Let’s dive into the world of case studies and discover why they are such a valuable tool in the arsenal of research methods.

What is a Case Study Method?

At its core, the case study method is a form of qualitative research that involves an in-depth, detailed examination of a single subject, such as an individual, group, organization, event, or phenomenon. It’s a method favored when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident, and where multiple sources of data are used to illuminate the case from various perspectives. This method’s strength lies in its ability to provide a comprehensive understanding of the case in its real-life context.

Historical Context and Evolution of Case Studies

Case studies have been around for centuries, with their roots in medical and psychological research. Over time, their application has spread to disciplines like sociology, anthropology, business, and education. The evolution of this method has been marked by a growing appreciation for qualitative data and the rich, contextual insights it can provide, which quantitative methods may overlook.

Characteristics of Case Study Research

What sets the case study method apart are its distinct characteristics:

- Intensive Examination: It provides a deep understanding of the case in question, considering the complexity and uniqueness of each case.

- Contextual Analysis: The researcher studies the case within its real-life context, recognizing that the context can significantly influence the phenomenon.

- Multiple Data Sources: Case studies often utilize various data sources like interviews, observations, documents, and reports, which provide multiple perspectives on the subject.

- Participant’s Perspective: This method often focuses on the perspectives of the participants within the case, giving voice to those directly involved.

Types of Case Studies

There are different types of case studies, each suited for specific research objectives:

- Exploratory: These are conducted before large-scale research projects to help identify questions, select measurement constructs, and develop hypotheses.

- Descriptive: These involve a detailed, in-depth description of the case, without attempting to determine cause and effect.

- Explanatory: These are used to investigate cause-and-effect relationships and understand underlying principles of certain phenomena.

- Intrinsic: This type is focused on the case itself because the case presents an unusual or unique issue.

- Instrumental: Here, the case is secondary to understanding a broader issue or phenomenon.

- Collective: These involve studying a group of cases collectively or comparably to understand a phenomenon, population, or general condition.

The Process of Conducting a Case Study

Conducting a case study involves several well-defined steps:

- Defining Your Case: What or who will you study? Define the case and ensure it aligns with your research objectives.

- Selecting Participants: If studying people, careful selection is crucial to ensure they fit the case criteria and can provide the necessary insights.

- Data Collection: Gather information through various methods like interviews, observations, and reviewing documents.

- Data Analysis: Analyze the collected data to identify patterns, themes, and insights related to your research question.

- Reporting Findings: Present your findings in a way that communicates the complexity and richness of the case study, often through narrative.

Case Studies in Practice: Real-world Examples

Case studies are not just academic exercises; they have practical applications in every field. For instance, in business, they can explore consumer behavior or organizational strategies. In psychology, they can provide detailed insight into individual behaviors or conditions. Education often uses case studies to explore teaching methods or learning difficulties.

Advantages of Case Study Research

While the case study method has its critics, it offers several undeniable advantages:

- Rich, Detailed Data: It captures data too complex for quantitative methods.

- Contextual Insights: It provides a better understanding of the phenomena in its natural setting.

- Contribution to Theory: It can generate and refine theory, offering a foundation for further research.

Limitations and Criticism

However, it’s important to acknowledge the limitations and criticisms:

- Generalizability : Findings from case studies may not be widely generalizable due to the focus on a single case.

- Subjectivity: The researcher’s perspective may influence the study, which requires careful reflection and transparency.

- Time-Consuming: They require a significant amount of time to conduct and analyze properly.

Concluding Thoughts on the Case Study Method

The case study method is a powerful tool that allows researchers to delve into the intricacies of a subject in its real-world environment. While not without its challenges, when executed correctly, the insights garnered can be incredibly valuable, offering depth and context that other methods may miss. Robert K\. Yin ’s advocacy for this method underscores its potential to illuminate and explain contemporary phenomena, making it an indispensable part of the researcher’s toolkit.

Reflecting on the case study method, how do you think its application could change with the advancements in technology and data analytics? Could such a traditional method be enhanced or even replaced in the future?

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating 0 / 5. Vote count: 0

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Submit Comment

Research Methods in Psychology

1 Introduction to Psychological Research – Objectives and Goals, Problems, Hypothesis and Variables

- Nature of Psychological Research

- The Context of Discovery

- Context of Justification

- Characteristics of Psychological Research

- Goals and Objectives of Psychological Research

2 Introduction to Psychological Experiments and Tests

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Extraneous Variables

- Experimental and Control Groups

- Introduction of Test

- Types of Psychological Test

- Uses of Psychological Tests

3 Steps in Research

- Research Process

- Identification of the Problem

- Review of Literature

- Formulating a Hypothesis

- Identifying Manipulating and Controlling Variables

- Formulating a Research Design

- Constructing Devices for Observation and Measurement

- Sample Selection and Data Collection

- Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Hypothesis Testing

- Drawing Conclusion

4 Types of Research and Methods of Research

- Historical Research

- Descriptive Research

- Correlational Research

- Qualitative Research

- Ex-Post Facto Research

- True Experimental Research

- Quasi-Experimental Research

5 Definition and Description Research Design, Quality of Research Design

- Research Design

- Purpose of Research Design

- Design Selection

- Criteria of Research Design

- Qualities of Research Design

6 Experimental Design (Control Group Design and Two Factor Design)

- Experimental Design

- Control Group Design

- Two Factor Design

7 Survey Design

- Survey Research Designs

- Steps in Survey Design

- Structuring and Designing the Questionnaire

- Interviewing Methodology

- Data Analysis

- Final Report

8 Single Subject Design

- Single Subject Design: Definition and Meaning

- Phases Within Single Subject Design

- Requirements of Single Subject Design

- Characteristics of Single Subject Design

- Types of Single Subject Design

- Advantages of Single Subject Design

- Disadvantages of Single Subject Design

9 Observation Method

- Definition and Meaning of Observation

- Characteristics of Observation

- Types of Observation

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Observation

- Guides for Observation Method

10 Interview and Interviewing

- Definition of Interview

- Types of Interview

- Aspects of Qualitative Research Interviews

- Interview Questions

- Convergent Interviewing as Action Research

- Research Team

11 Questionnaire Method

- Definition and Description of Questionnaires

- Types of Questionnaires

- Purpose of Questionnaire Studies

- Designing Research Questionnaires

- The Methods to Make a Questionnaire Efficient

- The Types of Questionnaire to be Included in the Questionnaire

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Questionnaire

- When to Use a Questionnaire?

12 Case Study

- Definition and Description of Case Study Method

- Historical Account of Case Study Method

- Designing Case Study

- Requirements for Case Studies

- Guideline to Follow in Case Study Method

- Other Important Measures in Case Study Method

- Case Reports

13 Report Writing

- Purpose of a Report

- Writing Style of the Report

- Report Writing – the Do’s and the Don’ts

- Format for Report in Psychology Area

- Major Sections in a Report

14 Review of Literature

- Purposes of Review of Literature

- Sources of Review of Literature

- Types of Literature

- Writing Process of the Review of Literature

- Preparation of Index Card for Reviewing and Abstracting

15 Methodology

- Definition and Purpose of Methodology

- Participants (Sample)

- Apparatus and Materials

16 Result, Analysis and Discussion of the Data

- Definition and Description of Results

- Statistical Presentation

- Tables and Figures

17 Summary and Conclusion

- Summary Definition and Description

- Guidelines for Writing a Summary

- Writing the Summary and Choosing Words

- A Process for Paraphrasing and Summarising

- Summary of a Report

- Writing Conclusions

18 References in Research Report

- Reference List (the Format)

- References (Process of Writing)

- Reference List and Print Sources

- Electronic Sources

- Book on CD Tape and Movie

- Reference Specifications

- General Guidelines to Write References

Share on Mastodon

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Perspective

- Published: 22 November 2022

Single case studies are a powerful tool for developing, testing and extending theories

- Lyndsey Nickels ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0311-3524 1 , 2 ,

- Simon Fischer-Baum ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6067-0538 3 &

- Wendy Best ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8375-5916 4

Nature Reviews Psychology volume 1 , pages 733–747 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

666 Accesses

5 Citations

26 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Neurological disorders

Psychology embraces a diverse range of methodologies. However, most rely on averaging group data to draw conclusions. In this Perspective, we argue that single case methodology is a valuable tool for developing and extending psychological theories. We stress the importance of single case and case series research, drawing on classic and contemporary cases in which cognitive and perceptual deficits provide insights into typical cognitive processes in domains such as memory, delusions, reading and face perception. We unpack the key features of single case methodology, describe its strengths, its value in adjudicating between theories, and outline its benefits for a better understanding of deficits and hence more appropriate interventions. The unique insights that single case studies have provided illustrate the value of in-depth investigation within an individual. Single case methodology has an important place in the psychologist’s toolkit and it should be valued as a primary research tool.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$59.00 per year

only $4.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Comparing meta-analyses and preregistered multiple-laboratory replication projects

The fundamental importance of method to theory

A critical evaluation of the p-factor literature

Corkin, S. Permanent Present Tense: The Unforgettable Life Of The Amnesic Patient, H. M . Vol. XIX, 364 (Basic Books, 2013).

Lilienfeld, S. O. Psychology: From Inquiry To Understanding (Pearson, 2019).

Schacter, D. L., Gilbert, D. T., Nock, M. K. & Wegner, D. M. Psychology (Worth Publishers, 2019).

Eysenck, M. W. & Brysbaert, M. Fundamentals Of Cognition (Routledge, 2018).

Squire, L. R. Memory and brain systems: 1969–2009. J. Neurosci. 29 , 12711–12716 (2009).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Corkin, S. What’s new with the amnesic patient H.M.? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3 , 153–160 (2002).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Schubert, T. M. et al. Lack of awareness despite complex visual processing: evidence from event-related potentials in a case of selective metamorphopsia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117 , 16055–16064 (2020).

Behrmann, M. & Plaut, D. C. Bilateral hemispheric processing of words and faces: evidence from word impairments in prosopagnosia and face impairments in pure alexia. Cereb. Cortex 24 , 1102–1118 (2014).

Plaut, D. C. & Behrmann, M. Complementary neural representations for faces and words: a computational exploration. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 28 , 251–275 (2011).

Haxby, J. V. et al. Distributed and overlapping representations of faces and objects in ventral temporal cortex. Science 293 , 2425–2430 (2001).

Hirshorn, E. A. et al. Decoding and disrupting left midfusiform gyrus activity during word reading. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113 , 8162–8167 (2016).

Kosakowski, H. L. et al. Selective responses to faces, scenes, and bodies in the ventral visual pathway of infants. Curr. Biol. 32 , 265–274.e5 (2022).

Harlow, J. Passage of an iron rod through the head. Boston Med. Surgical J . https://doi.org/10.1176/jnp.11.2.281 (1848).

Broca, P. Remarks on the seat of the faculty of articulated language, following an observation of aphemia (loss of speech). Bull. Soc. Anat. 6 , 330–357 (1861).

Google Scholar

Dejerine, J. Contribution A L’étude Anatomo-pathologique Et Clinique Des Différentes Variétés De Cécité Verbale: I. Cécité Verbale Avec Agraphie Ou Troubles Très Marqués De L’écriture; II. Cécité Verbale Pure Avec Intégrité De L’écriture Spontanée Et Sous Dictée (Société de Biologie, 1892).

Liepmann, H. Das Krankheitsbild der Apraxie (“motorischen Asymbolie”) auf Grund eines Falles von einseitiger Apraxie (Fortsetzung). Eur. Neurol. 8 , 102–116 (1900).

Article Google Scholar

Basso, A., Spinnler, H., Vallar, G. & Zanobio, M. E. Left hemisphere damage and selective impairment of auditory verbal short-term memory. A case study. Neuropsychologia 20 , 263–274 (1982).

Humphreys, G. W. & Riddoch, M. J. The fractionation of visual agnosia. In Visual Object Processing: A Cognitive Neuropsychological Approach 281–306 (Lawrence Erlbaum, 1987).

Whitworth, A., Webster, J. & Howard, D. A Cognitive Neuropsychological Approach To Assessment And Intervention In Aphasia (Psychology Press, 2014).

Caramazza, A. On drawing inferences about the structure of normal cognitive systems from the analysis of patterns of impaired performance: the case for single-patient studies. Brain Cogn. 5 , 41–66 (1986).

Caramazza, A. & McCloskey, M. The case for single-patient studies. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 5 , 517–527 (1988).

Shallice, T. Cognitive neuropsychology and its vicissitudes: the fate of Caramazza’s axioms. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 32 , 385–411 (2015).

Shallice, T. From Neuropsychology To Mental Structure (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1988).

Coltheart, M. Assumptions and methods in cognitive neuropscyhology. In The Handbook Of Cognitive Neuropsychology: What Deficits Reveal About The Human Mind (ed. Rapp, B.) 3–22 (Psychology Press, 2001).

McCloskey, M. & Chaisilprungraung, T. The value of cognitive neuropsychology: the case of vision research. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 34 , 412–419 (2017).

McCloskey, M. The future of cognitive neuropsychology. In The Handbook Of Cognitive Neuropsychology: What Deficits Reveal About The Human Mind (ed. Rapp, B.) 593–610 (Psychology Press, 2001).

Lashley, K. S. In search of the engram. In Physiological Mechanisms in Animal Behavior 454–482 (Academic Press, 1950).

Squire, L. R. & Wixted, J. T. The cognitive neuroscience of human memory since H.M. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 34 , 259–288 (2011).

Stone, G. O., Vanhoy, M. & Orden, G. C. V. Perception is a two-way street: feedforward and feedback phonology in visual word recognition. J. Mem. Lang. 36 , 337–359 (1997).

Perfetti, C. A. The psycholinguistics of spelling and reading. In Learning To Spell: Research, Theory, And Practice Across Languages 21–38 (Lawrence Erlbaum, 1997).

Nickels, L. The autocue? self-generated phonemic cues in the treatment of a disorder of reading and naming. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 9 , 155–182 (1992).

Rapp, B., Benzing, L. & Caramazza, A. The autonomy of lexical orthography. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 14 , 71–104 (1997).

Bonin, P., Roux, S. & Barry, C. Translating nonverbal pictures into verbal word names. Understanding lexical access and retrieval. In Past, Present, And Future Contributions Of Cognitive Writing Research To Cognitive Psychology 315–522 (Psychology Press, 2011).

Bonin, P., Fayol, M. & Gombert, J.-E. Role of phonological and orthographic codes in picture naming and writing: an interference paradigm study. Cah. Psychol. Cogn./Current Psychol. Cogn. 16 , 299–324 (1997).

Bonin, P., Fayol, M. & Peereman, R. Masked form priming in writing words from pictures: evidence for direct retrieval of orthographic codes. Acta Psychol. 99 , 311–328 (1998).

Bentin, S., Allison, T., Puce, A., Perez, E. & McCarthy, G. Electrophysiological studies of face perception in humans. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 8 , 551–565 (1996).

Jeffreys, D. A. Evoked potential studies of face and object processing. Vis. Cogn. 3 , 1–38 (1996).

Laganaro, M., Morand, S., Michel, C. M., Spinelli, L. & Schnider, A. ERP correlates of word production before and after stroke in an aphasic patient. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 23 , 374–381 (2011).

Indefrey, P. & Levelt, W. J. M. The spatial and temporal signatures of word production components. Cognition 92 , 101–144 (2004).

Valente, A., Burki, A. & Laganaro, M. ERP correlates of word production predictors in picture naming: a trial by trial multiple regression analysis from stimulus onset to response. Front. Neurosci. 8 , 390 (2014).

Kittredge, A. K., Dell, G. S., Verkuilen, J. & Schwartz, M. F. Where is the effect of frequency in word production? Insights from aphasic picture-naming errors. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 25 , 463–492 (2008).

Domdei, N. et al. Ultra-high contrast retinal display system for single photoreceptor psychophysics. Biomed. Opt. Express 9 , 157 (2018).

Poldrack, R. A. et al. Long-term neural and physiological phenotyping of a single human. Nat. Commun. 6 , 8885 (2015).

Coltheart, M. The assumptions of cognitive neuropsychology: reflections on Caramazza (1984, 1986). Cogn. Neuropsychol. 34 , 397–402 (2017).

Badecker, W. & Caramazza, A. A final brief in the case against agrammatism: the role of theory in the selection of data. Cognition 24 , 277–282 (1986).

Fischer-Baum, S. Making sense of deviance: Identifying dissociating cases within the case series approach. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 30 , 597–617 (2013).

Nickels, L., Howard, D. & Best, W. On the use of different methodologies in cognitive neuropsychology: drink deep and from several sources. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 28 , 475–485 (2011).

Dell, G. S. & Schwartz, M. F. Who’s in and who’s out? Inclusion criteria, model evaluation, and the treatment of exceptions in case series. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 28 , 515–520 (2011).

Schwartz, M. F. & Dell, G. S. Case series investigations in cognitive neuropsychology. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 27 , 477–494 (2010).

Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 112 , 155–159 (1992).

Martin, R. C. & Allen, C. Case studies in neuropsychology. In APA Handbook Of Research Methods In Psychology Vol. 2 Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, And Biological (eds Cooper, H. et al.) 633–646 (American Psychological Association, 2012).

Leivada, E., Westergaard, M., Duñabeitia, J. A. & Rothman, J. On the phantom-like appearance of bilingualism effects on neurocognition: (how) should we proceed? Bilingualism 24 , 197–210 (2021).

Arnett, J. J. The neglected 95%: why American psychology needs to become less American. Am. Psychol. 63 , 602–614 (2008).

Stolz, J. A., Besner, D. & Carr, T. H. Implications of measures of reliability for theories of priming: activity in semantic memory is inherently noisy and uncoordinated. Vis. Cogn. 12 , 284–336 (2005).

Cipora, K. et al. A minority pulls the sample mean: on the individual prevalence of robust group-level cognitive phenomena — the instance of the SNARC effect. Preprint at psyArXiv https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/bwyr3 (2019).

Andrews, S., Lo, S. & Xia, V. Individual differences in automatic semantic priming. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 43 , 1025–1039 (2017).

Tan, L. C. & Yap, M. J. Are individual differences in masked repetition and semantic priming reliable? Vis. Cogn. 24 , 182–200 (2016).

Olsson-Collentine, A., Wicherts, J. M. & van Assen, M. A. L. M. Heterogeneity in direct replications in psychology and its association with effect size. Psychol. Bull. 146 , 922–940 (2020).

Gratton, C. & Braga, R. M. Editorial overview: deep imaging of the individual brain: past, practice, and promise. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 40 , iii–vi (2021).

Fedorenko, E. The early origins and the growing popularity of the individual-subject analytic approach in human neuroscience. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 40 , 105–112 (2021).

Xue, A. et al. The detailed organization of the human cerebellum estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity within the individual. J. Neurophysiol. 125 , 358–384 (2021).

Petit, S. et al. Toward an individualized neural assessment of receptive language in children. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 63 , 2361–2385 (2020).

Jung, K.-H. et al. Heterogeneity of cerebral white matter lesions and clinical correlates in older adults. Stroke 52 , 620–630 (2021).

Falcon, M. I., Jirsa, V. & Solodkin, A. A new neuroinformatics approach to personalized medicine in neurology: the virtual brain. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 29 , 429–436 (2016).

Duncan, G. J., Engel, M., Claessens, A. & Dowsett, C. J. Replication and robustness in developmental research. Dev. Psychol. 50 , 2417–2425 (2014).

Open Science Collaboration. Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science 349 , aac4716 (2015).

Tackett, J. L., Brandes, C. M., King, K. M. & Markon, K. E. Psychology’s replication crisis and clinical psychological science. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 15 , 579–604 (2019).

Munafò, M. R. et al. A manifesto for reproducible science. Nat. Hum. Behav. 1 , 0021 (2017).

Oldfield, R. C. & Wingfield, A. The time it takes to name an object. Nature 202 , 1031–1032 (1964).

Oldfield, R. C. & Wingfield, A. Response latencies in naming objects. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 17 , 273–281 (1965).

Brysbaert, M. How many participants do we have to include in properly powered experiments? A tutorial of power analysis with reference tables. J. Cogn. 2 , 16 (2019).

Brysbaert, M. Power considerations in bilingualism research: time to step up our game. Bilingualism https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728920000437 (2020).

Machery, E. What is a replication? Phil. Sci. 87 , 545–567 (2020).

Nosek, B. A. & Errington, T. M. What is replication? PLoS Biol. 18 , e3000691 (2020).

Li, X., Huang, L., Yao, P. & Hyönä, J. Universal and specific reading mechanisms across different writing systems. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 1 , 133–144 (2022).

Rapp, B. (Ed.) The Handbook Of Cognitive Neuropsychology: What Deficits Reveal About The Human Mind (Psychology Press, 2001).

Code, C. et al. Classic Cases In Neuropsychology (Psychology Press, 1996).

Patterson, K., Marshall, J. C. & Coltheart, M. Surface Dyslexia: Neuropsychological And Cognitive Studies Of Phonological Reading (Routledge, 2017).

Marshall, J. C. & Newcombe, F. Patterns of paralexia: a psycholinguistic approach. J. Psycholinguist. Res. 2 , 175–199 (1973).

Castles, A. & Coltheart, M. Varieties of developmental dyslexia. Cognition 47 , 149–180 (1993).

Khentov-Kraus, L. & Friedmann, N. Vowel letter dyslexia. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 35 , 223–270 (2018).

Winskel, H. Orthographic and phonological parafoveal processing of consonants, vowels, and tones when reading Thai. Appl. Psycholinguist. 32 , 739–759 (2011).

Hepner, C., McCloskey, M. & Rapp, B. Do reading and spelling share orthographic representations? Evidence from developmental dysgraphia. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 34 , 119–143 (2017).

Hanley, J. R. & Sotiropoulos, A. Developmental surface dysgraphia without surface dyslexia. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 35 , 333–341 (2018).

Zihl, J. & Heywood, C. A. The contribution of single case studies to the neuroscience of vision: single case studies in vision neuroscience. Psych. J. 5 , 5–17 (2016).

Bouvier, S. E. & Engel, S. A. Behavioral deficits and cortical damage loci in cerebral achromatopsia. Cereb. Cortex 16 , 183–191 (2006).

Zihl, J. & Heywood, C. A. The contribution of LM to the neuroscience of movement vision. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 9 , 6 (2015).

Dotan, D. & Friedmann, N. Separate mechanisms for number reading and word reading: evidence from selective impairments. Cortex 114 , 176–192 (2019).

McCloskey, M. & Schubert, T. Shared versus separate processes for letter and digit identification. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 31 , 437–460 (2014).

Fayol, M. & Seron, X. On numerical representations. Insights from experimental, neuropsychological, and developmental research. In Handbook of Mathematical Cognition (ed. Campbell, J.) 3–23 (Psychological Press, 2005).

Bornstein, B. & Kidron, D. P. Prosopagnosia. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiat. 22 , 124–131 (1959).

Kühn, C. D., Gerlach, C., Andersen, K. B., Poulsen, M. & Starrfelt, R. Face recognition in developmental dyslexia: evidence for dissociation between faces and words. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 38 , 107–115 (2021).

Barton, J. J. S., Albonico, A., Susilo, T., Duchaine, B. & Corrow, S. L. Object recognition in acquired and developmental prosopagnosia. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 36 , 54–84 (2019).

Renault, B., Signoret, J.-L., Debruille, B., Breton, F. & Bolgert, F. Brain potentials reveal covert facial recognition in prosopagnosia. Neuropsychologia 27 , 905–912 (1989).

Bauer, R. M. Autonomic recognition of names and faces in prosopagnosia: a neuropsychological application of the guilty knowledge test. Neuropsychologia 22 , 457–469 (1984).

Haan, E. H. F., de, Young, A. & Newcombe, F. Face recognition without awareness. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 4 , 385–415 (1987).

Ellis, H. D. & Lewis, M. B. Capgras delusion: a window on face recognition. Trends Cogn. Sci. 5 , 149–156 (2001).

Ellis, H. D., Young, A. W., Quayle, A. H. & De Pauw, K. W. Reduced autonomic responses to faces in Capgras delusion. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 264 , 1085–1092 (1997).

Collins, M. N., Hawthorne, M. E., Gribbin, N. & Jacobson, R. Capgras’ syndrome with organic disorders. Postgrad. Med. J. 66 , 1064–1067 (1990).

Enoch, D., Puri, B. K. & Ball, H. Uncommon Psychiatric Syndromes 5th edn (Routledge, 2020).

Tranel, D., Damasio, H. & Damasio, A. R. Double dissociation between overt and covert face recognition. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 7 , 425–432 (1995).

Brighetti, G., Bonifacci, P., Borlimi, R. & Ottaviani, C. “Far from the heart far from the eye”: evidence from the Capgras delusion. Cogn. Neuropsychiat. 12 , 189–197 (2007).

Coltheart, M., Langdon, R. & McKay, R. Delusional belief. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 62 , 271–298 (2011).

Coltheart, M. Cognitive neuropsychiatry and delusional belief. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 60 , 1041–1062 (2007).

Coltheart, M. & Davies, M. How unexpected observations lead to new beliefs: a Peircean pathway. Conscious. Cogn. 87 , 103037 (2021).

Coltheart, M. & Davies, M. Failure of hypothesis evaluation as a factor in delusional belief. Cogn. Neuropsychiat. 26 , 213–230 (2021).

McCloskey, M. et al. A developmental deficit in localizing objects from vision. Psychol. Sci. 6 , 112–117 (1995).

McCloskey, M., Valtonen, J. & Cohen Sherman, J. Representing orientation: a coordinate-system hypothesis and evidence from developmental deficits. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 23 , 680–713 (2006).

McCloskey, M. Spatial representations and multiple-visual-systems hypotheses: evidence from a developmental deficit in visual location and orientation processing. Cortex 40 , 677–694 (2004).

Gregory, E. & McCloskey, M. Mirror-image confusions: implications for representation and processing of object orientation. Cognition 116 , 110–129 (2010).

Gregory, E., Landau, B. & McCloskey, M. Representation of object orientation in children: evidence from mirror-image confusions. Vis. Cogn. 19 , 1035–1062 (2011).

Laine, M. & Martin, N. Cognitive neuropsychology has been, is, and will be significant to aphasiology. Aphasiology 26 , 1362–1376 (2012).

Howard, D. & Patterson, K. The Pyramids And Palm Trees Test: A Test Of Semantic Access From Words And Pictures (Thames Valley Test Co., 1992).

Kay, J., Lesser, R. & Coltheart, M. PALPA: Psycholinguistic Assessments Of Language Processing In Aphasia. 2: Picture & Word Semantics, Sentence Comprehension (Erlbaum, 2001).

Franklin, S. Dissociations in auditory word comprehension; evidence from nine fluent aphasic patients. Aphasiology 3 , 189–207 (1989).

Howard, D., Swinburn, K. & Porter, G. Putting the CAT out: what the comprehensive aphasia test has to offer. Aphasiology 24 , 56–74 (2010).

Conti-Ramsden, G., Crutchley, A. & Botting, N. The extent to which psychometric tests differentiate subgroups of children with SLI. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 40 , 765–777 (1997).

Bishop, D. V. M. & McArthur, G. M. Individual differences in auditory processing in specific language impairment: a follow-up study using event-related potentials and behavioural thresholds. Cortex 41 , 327–341 (2005).

Bishop, D. V. M., Snowling, M. J., Thompson, P. A. & Greenhalgh, T., and the CATALISE-2 consortium. Phase 2 of CATALISE: a multinational and multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study of problems with language development: terminology. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiat. 58 , 1068–1080 (2017).

Wilson, A. J. et al. Principles underlying the design of ‘the number race’, an adaptive computer game for remediation of dyscalculia. Behav. Brain Funct. 2 , 19 (2006).

Basso, A. & Marangolo, P. Cognitive neuropsychological rehabilitation: the emperor’s new clothes? Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 10 , 219–229 (2000).

Murad, M. H., Asi, N., Alsawas, M. & Alahdab, F. New evidence pyramid. Evidence-based Med. 21 , 125–127 (2016).

Greenhalgh, T., Howick, J. & Maskrey, N., for the Evidence Based Medicine Renaissance Group. Evidence based medicine: a movement in crisis? Br. Med. J. 348 , g3725–g3725 (2014).

Best, W., Ping Sze, W., Edmundson, A. & Nickels, L. What counts as evidence? Swimming against the tide: valuing both clinically informed experimentally controlled case series and randomized controlled trials in intervention research. Evidence-based Commun. Assess. Interv. 13 , 107–135 (2019).

Best, W. et al. Understanding differing outcomes from semantic and phonological interventions with children with word-finding difficulties: a group and case series study. Cortex 134 , 145–161 (2021).

OCEBM Levels of Evidence Working Group. The Oxford Levels of Evidence 2. CEBM https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/ocebm-levels-of-evidence (2011).

Holler, D. E., Behrmann, M. & Snow, J. C. Real-world size coding of solid objects, but not 2-D or 3-D images, in visual agnosia patients with bilateral ventral lesions. Cortex 119 , 555–568 (2019).

Duchaine, B. C., Yovel, G., Butterworth, E. J. & Nakayama, K. Prosopagnosia as an impairment to face-specific mechanisms: elimination of the alternative hypotheses in a developmental case. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 23 , 714–747 (2006).

Hartley, T. et al. The hippocampus is required for short-term topographical memory in humans. Hippocampus 17 , 34–48 (2007).

Pishnamazi, M. et al. Attentional bias towards and away from fearful faces is modulated by developmental amygdala damage. Cortex 81 , 24–34 (2016).

Rapp, B., Fischer-Baum, S. & Miozzo, M. Modality and morphology: what we write may not be what we say. Psychol. Sci. 26 , 892–902 (2015).

Yong, K. X. X., Warren, J. D., Warrington, E. K. & Crutch, S. J. Intact reading in patients with profound early visual dysfunction. Cortex 49 , 2294–2306 (2013).

Rockland, K. S. & Van Hoesen, G. W. Direct temporal–occipital feedback connections to striate cortex (V1) in the macaque monkey. Cereb. Cortex 4 , 300–313 (1994).

Haynes, J.-D., Driver, J. & Rees, G. Visibility reflects dynamic changes of effective connectivity between V1 and fusiform cortex. Neuron 46 , 811–821 (2005).

Tanaka, K. Mechanisms of visual object recognition: monkey and human studies. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 7 , 523–529 (1997).

Fischer-Baum, S., McCloskey, M. & Rapp, B. Representation of letter position in spelling: evidence from acquired dysgraphia. Cognition 115 , 466–490 (2010).

Houghton, G. The problem of serial order: a neural network model of sequence learning and recall. In Current Research In Natural Language Generation (eds Dale, R., Mellish, C. & Zock, M.) 287–319 (Academic Press, 1990).

Fieder, N., Nickels, L., Biedermann, B. & Best, W. From “some butter” to “a butter”: an investigation of mass and count representation and processing. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 31 , 313–349 (2014).

Fieder, N., Nickels, L., Biedermann, B. & Best, W. How ‘some garlic’ becomes ‘a garlic’ or ‘some onion’: mass and count processing in aphasia. Neuropsychologia 75 , 626–645 (2015).

Schröder, A., Burchert, F. & Stadie, N. Training-induced improvement of noncanonical sentence production does not generalize to comprehension: evidence for modality-specific processes. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 32 , 195–220 (2015).

Stadie, N. et al. Unambiguous generalization effects after treatment of non-canonical sentence production in German agrammatism. Brain Lang. 104 , 211–229 (2008).

Schapiro, A. C., Gregory, E., Landau, B., McCloskey, M. & Turk-Browne, N. B. The necessity of the medial temporal lobe for statistical learning. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 26 , 1736–1747 (2014).

Schapiro, A. C., Kustner, L. V. & Turk-Browne, N. B. Shaping of object representations in the human medial temporal lobe based on temporal regularities. Curr. Biol. 22 , 1622–1627 (2012).

Baddeley, A., Vargha-Khadem, F. & Mishkin, M. Preserved recognition in a case of developmental amnesia: implications for the acaquisition of semantic memory? J. Cogn. Neurosci. 13 , 357–369 (2001).

Snyder, J. J. & Chatterjee, A. Spatial-temporal anisometries following right parietal damage. Neuropsychologia 42 , 1703–1708 (2004).

Ashkenazi, S., Henik, A., Ifergane, G. & Shelef, I. Basic numerical processing in left intraparietal sulcus (IPS) acalculia. Cortex 44 , 439–448 (2008).

Lebrun, M.-A., Moreau, P., McNally-Gagnon, A., Mignault Goulet, G. & Peretz, I. Congenital amusia in childhood: a case study. Cortex 48 , 683–688 (2012).

Vannuscorps, G., Andres, M. & Pillon, A. When does action comprehension need motor involvement? Evidence from upper limb aplasia. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 30 , 253–283 (2013).

Jeannerod, M. Neural simulation of action: a unifying mechanism for motor cognition. NeuroImage 14 , S103–S109 (2001).

Blakemore, S.-J. & Decety, J. From the perception of action to the understanding of intention. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2 , 561–567 (2001).

Rizzolatti, G. & Craighero, L. The mirror-neuron system. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 27 , 169–192 (2004).

Forde, E. M. E., Humphreys, G. W. & Remoundou, M. Disordered knowledge of action order in action disorganisation syndrome. Neurocase 10 , 19–28 (2004).

Mazzi, C. & Savazzi, S. The glamor of old-style single-case studies in the neuroimaging era: insights from a patient with hemianopia. Front. Psychol. 10 , 965 (2019).

Coltheart, M. What has functional neuroimaging told us about the mind (so far)? (Position Paper Presented to the European Cognitive Neuropsychology Workshop, Bressanone, 2005). Cortex 42 , 323–331 (2006).

Page, M. P. A. What can’t functional neuroimaging tell the cognitive psychologist? Cortex 42 , 428–443 (2006).

Blank, I. A., Kiran, S. & Fedorenko, E. Can neuroimaging help aphasia researchers? Addressing generalizability, variability, and interpretability. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 34 , 377–393 (2017).

Niv, Y. The primacy of behavioral research for understanding the brain. Behav. Neurosci. 135 , 601–609 (2021).

Crawford, J. R. & Howell, D. C. Comparing an individual’s test score against norms derived from small samples. Clin. Neuropsychol. 12 , 482–486 (1998).

Crawford, J. R., Garthwaite, P. H. & Ryan, K. Comparing a single case to a control sample: testing for neuropsychological deficits and dissociations in the presence of covariates. Cortex 47 , 1166–1178 (2011).

McIntosh, R. D. & Rittmo, J. Ö. Power calculations in single-case neuropsychology: a practical primer. Cortex 135 , 146–158 (2021).

Patterson, K. & Plaut, D. C. “Shallow draughts intoxicate the brain”: lessons from cognitive science for cognitive neuropsychology. Top. Cogn. Sci. 1 , 39–58 (2009).

Lambon Ralph, M. A., Patterson, K. & Plaut, D. C. Finite case series or infinite single-case studies? Comments on “Case series investigations in cognitive neuropsychology” by Schwartz and Dell (2010). Cogn. Neuropsychol. 28 , 466–474 (2011).

Horien, C., Shen, X., Scheinost, D. & Constable, R. T. The individual functional connectome is unique and stable over months to years. NeuroImage 189 , 676–687 (2019).

Epelbaum, S. et al. Pure alexia as a disconnection syndrome: new diffusion imaging evidence for an old concept. Cortex 44 , 962–974 (2008).

Fischer-Baum, S. & Campana, G. Neuroplasticity and the logic of cognitive neuropsychology. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 34 , 403–411 (2017).

Paul, S., Baca, E. & Fischer-Baum, S. Cerebellar contributions to orthographic working memory: a single case cognitive neuropsychological investigation. Neuropsychologia 171 , 108242 (2022).

Feinstein, J. S., Adolphs, R., Damasio, A. & Tranel, D. The human amygdala and the induction and experience of fear. Curr. Biol. 21 , 34–38 (2011).

Crawford, J., Garthwaite, P. & Gray, C. Wanted: fully operational definitions of dissociations in single-case studies. Cortex 39 , 357–370 (2003).

McIntosh, R. D. Simple dissociations for a higher-powered neuropsychology. Cortex 103 , 256–265 (2018).

McIntosh, R. D. & Brooks, J. L. Current tests and trends in single-case neuropsychology. Cortex 47 , 1151–1159 (2011).

Best, W., Schröder, A. & Herbert, R. An investigation of a relative impairment in naming non-living items: theoretical and methodological implications. J. Neurolinguistics 19 , 96–123 (2006).

Franklin, S., Howard, D. & Patterson, K. Abstract word anomia. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 12 , 549–566 (1995).

Coltheart, M., Patterson, K. E. & Marshall, J. C. Deep Dyslexia (Routledge, 1980).

Nickels, L., Kohnen, S. & Biedermann, B. An untapped resource: treatment as a tool for revealing the nature of cognitive processes. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 27 , 539–562 (2010).

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all of those pioneers of and advocates for single case study research who have mentored, inspired and encouraged us over the years, and the many other colleagues with whom we have discussed these issues.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Psychological Sciences & Macquarie University Centre for Reading, Macquarie University, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Lyndsey Nickels

NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence in Aphasia Recovery and Rehabilitation, Australia

Psychological Sciences, Rice University, Houston, TX, USA

Simon Fischer-Baum

Psychology and Language Sciences, University College London, London, UK

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

L.N. led and was primarily responsible for the structuring and writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed to all aspects of the article.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Lyndsey Nickels .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information.

Nature Reviews Psychology thanks Yanchao Bi, Rob McIntosh, and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Nickels, L., Fischer-Baum, S. & Best, W. Single case studies are a powerful tool for developing, testing and extending theories. Nat Rev Psychol 1 , 733–747 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-022-00127-y

Download citation

Accepted : 13 October 2022

Published : 22 November 2022

Issue Date : December 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-022-00127-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

2.2 Approaches to Research

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the different research methods used by psychologists

- Discuss the strengths and weaknesses of case studies, naturalistic observation, surveys, and archival research

- Compare longitudinal and cross-sectional approaches to research

- Compare and contrast correlation and causation

There are many research methods available to psychologists in their efforts to understand, describe, and explain behavior and the cognitive and biological processes that underlie it. Some methods rely on observational techniques. Other approaches involve interactions between the researcher and the individuals who are being studied—ranging from a series of simple questions to extensive, in-depth interviews—to well-controlled experiments.

Each of these research methods has unique strengths and weaknesses, and each method may only be appropriate for certain types of research questions. For example, studies that rely primarily on observation produce incredible amounts of information, but the ability to apply this information to the larger population is somewhat limited because of small sample sizes. Survey research, on the other hand, allows researchers to easily collect data from relatively large samples. While this allows for results to be generalized to the larger population more easily, the information that can be collected on any given survey is somewhat limited and subject to problems associated with any type of self-reported data. Some researchers conduct archival research by using existing records. While this can be a fairly inexpensive way to collect data that can provide insight into a number of research questions, researchers using this approach have no control on how or what kind of data was collected. All of the methods described thus far are correlational in nature. This means that researchers can speak to important relationships that might exist between two or more variables of interest. However, correlational data cannot be used to make claims about cause-and-effect relationships.

Correlational research can find a relationship between two variables, but the only way a researcher can claim that the relationship between the variables is cause and effect is to perform an experiment. In experimental research, which will be discussed later in this chapter, there is a tremendous amount of control over variables of interest. While this is a powerful approach, experiments are often conducted in artificial settings. This calls into question the validity of experimental findings with regard to how they would apply in real-world settings. In addition, many of the questions that psychologists would like to answer cannot be pursued through experimental research because of ethical concerns.

Clinical or Case Studies

In 2011, the New York Times published a feature story on Krista and Tatiana Hogan, Canadian twin girls. These particular twins are unique because Krista and Tatiana are conjoined twins, connected at the head. There is evidence that the two girls are connected in a part of the brain called the thalamus, which is a major sensory relay center. Most incoming sensory information is sent through the thalamus before reaching higher regions of the cerebral cortex for processing.

Link to Learning

Watch this CBC video about Krista's and Tatiana's lives to learn more.

The implications of this potential connection mean that it might be possible for one twin to experience the sensations of the other twin. For instance, if Krista is watching a particularly funny television program, Tatiana might smile or laugh even if she is not watching the program. This particular possibility has piqued the interest of many neuroscientists who seek to understand how the brain uses sensory information.