- WRITING SKILLS

Journalistic Writing

Search SkillsYouNeed:

Writing Skills:

- A - Z List of Writing Skills

The Essentials of Writing

- Common Mistakes in Writing

- Introduction to Grammar

- Improving Your Grammar

- Active and Passive Voice

- Punctuation

- Clarity in Writing

- Writing Concisely

- Coherence in Writing

- Gender Neutral Language

- Figurative Language

- When to Use Capital Letters

- Using Plain English

- Writing in UK and US English

- Understanding (and Avoiding) Clichés

- The Importance of Structure

- Know Your Audience

- Know Your Medium

- Formal and Informal Writing Styles

- Note-Taking from Reading

- Note-Taking for Verbal Exchanges

- Creative Writing

- Top Tips for Writing Fiction

- Writer's Voice

- Writing for Children

- Writing for Pleasure

- Writing for the Internet

- Technical Writing

- Academic Writing

- Editing and Proofreading

Writing Specific Documents

- Writing a CV or Résumé

- Writing a Covering Letter

- Writing a Personal Statement

- Writing Reviews

- Using LinkedIn Effectively

- Business Writing

- Study Skills

- Writing Your Dissertation or Thesis

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter and start improving your life in just 5 minutes a day.

You'll get our 5 free 'One Minute Life Skills' and our weekly newsletter.

We'll never share your email address and you can unsubscribe at any time.

Journalistic writing is, as you might expect, the style of writing used by journalists. It is therefore a term for the broad style of writing used by news media outlets to put together stories.

Every news media outlet has its own ‘house’ style, which is usually set out in guidelines. This describes grammar and style points to be used in that publication or website. However, there are some common factors and characteristics to all journalistic writing.

This page describes the five different types of journalistic writing. It also provides some tips for writing in journalistic style to help you develop your skills in this area.

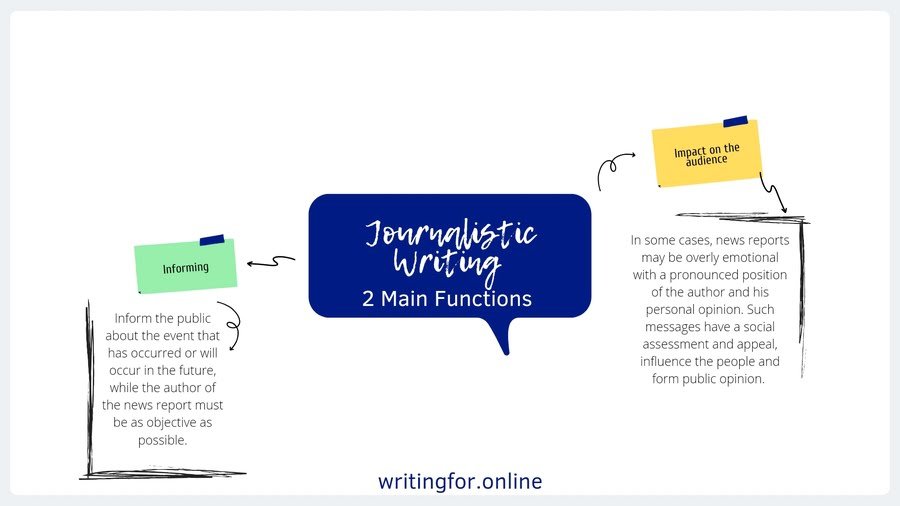

The Purpose of Journalistic Writing

Journalistic writing has a very clear purpose: to attract readers to a website, broadcaster or print media. This allows the owners to make money, usually by selling advertising space.

Newspapers traditionally did not make most of their money by selling newspapers. Instead, their main income was actually from advertising. If you look back at an early copy of the London Times , for example (from the early 1900s), the whole front page was actually advertisements, not news.

The news and stories are only a ‘hook’ to bring in readers and keep advertisers happy.

Journalists therefore want to attract readers to their stories—and then keep them.

They are therefore very good at identifying good stories, but also telling the story in a way that hooks and keeps readers interested.

Types of Journalistic Writing

There are five main types of journalistic writing:

Investigative journalism aims to discover the truth about a topic, person, group or event . It may require detailed and in-depth exploration through interviews, research and analysis. The purpose of investigative journalism is to answer questions.

News journalism reports facts, as they emerge . It aims to provide people with objective information about current events, in straightforward terms.

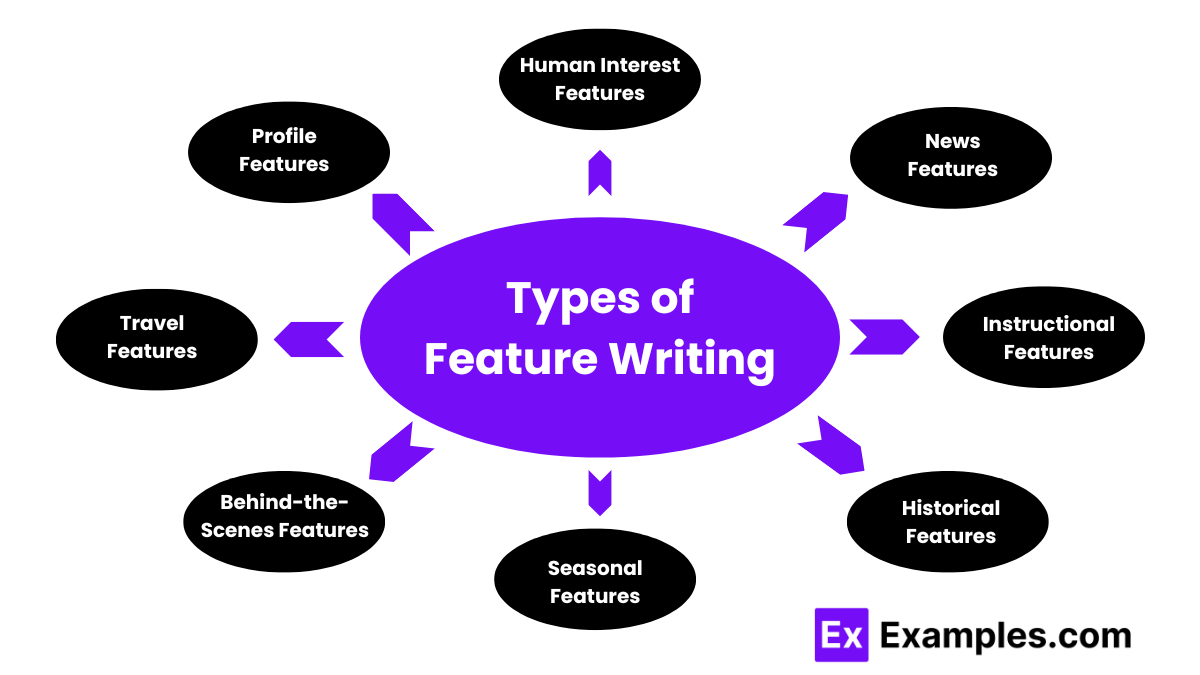

Feature writing provides a deeper look at events, people or topics , and offer a new perspective. Like investigative journalism, it may seek to uncover new information, but is less about answering questions, and more about simply providing more information.

Columns are the personal opinions of the writer . They are designed to entertain and persuade readers, and sometimes to be controversial and generate discussion.

Reviews describe a subject in a factual way, and then provide a personal opinion on it . They are often about books or television programmes when published in news media.

The importance of objectivity

It should be clear from the list of types of journalistic writing that journalists are not forbidden from expressing their opinions.

However, it is important that any journalist is absolutely clear when they are expressing their opinion, and when they are reporting on facts.

Readers are generally seeking objective writing and reporting when they are reading news or investigative journalism, or features. The place for opinions is columns or reviews.

The Journalistic Writing Process

Journalists tend to follow a clear process in writing any article. This allows them to put together a compelling story, with all the necessary elements.

This process is:

1. Gather all necessary information

The first step is to gather all the information that you need to write the story.

You want to know all the facts, from as many angles as possible. Journalists often spend time ‘on site’ as part of this process, interviewing people to find out what has happened, and how events have affected them.

Ideally, you want to use primary sources: people who were actually there, and witnessed the events. Secondary sources (those who were told by others what happened) are very much second-best in journalism.

2. Verify all your sources

It is crucial to establish the value of your information—that is, whether it is true or not.

A question of individual ‘truth’

It has become common in internet writing to talk about ‘your truth’, or ‘his truth’.

There is a place for this in journalism. It recognises that the same events may be experienced and interpreted in different ways by different people.

However, journalists also need to recognise that there are always some objective facts associated with any story. They must take time to separate these objective facts from opinions or perceptions and interpretations of events.

3. Establish your angle

You then need to establish your story ‘angle’ or focus: the aspect that makes it newsworthy.

This will vary with different types of journalism, and for different news outlets. It may also need some thought to establish why people should care about your story.

4. Write a strong opening paragraph

Your opening paragraph tells readers why they should bother to read on.

It needs to summarise the five Ws of the story: who, what, why, when, and where.

5. Consider the headline

Journalists are not necessarily expected to come up with their own headlines. However, it helps to consider how a piece might be headlined.

Being able to summarise the piece in a few words is a very good way to ensure that you are clear about your story and angle.

6. Use the ‘inverted pyramid’ structure

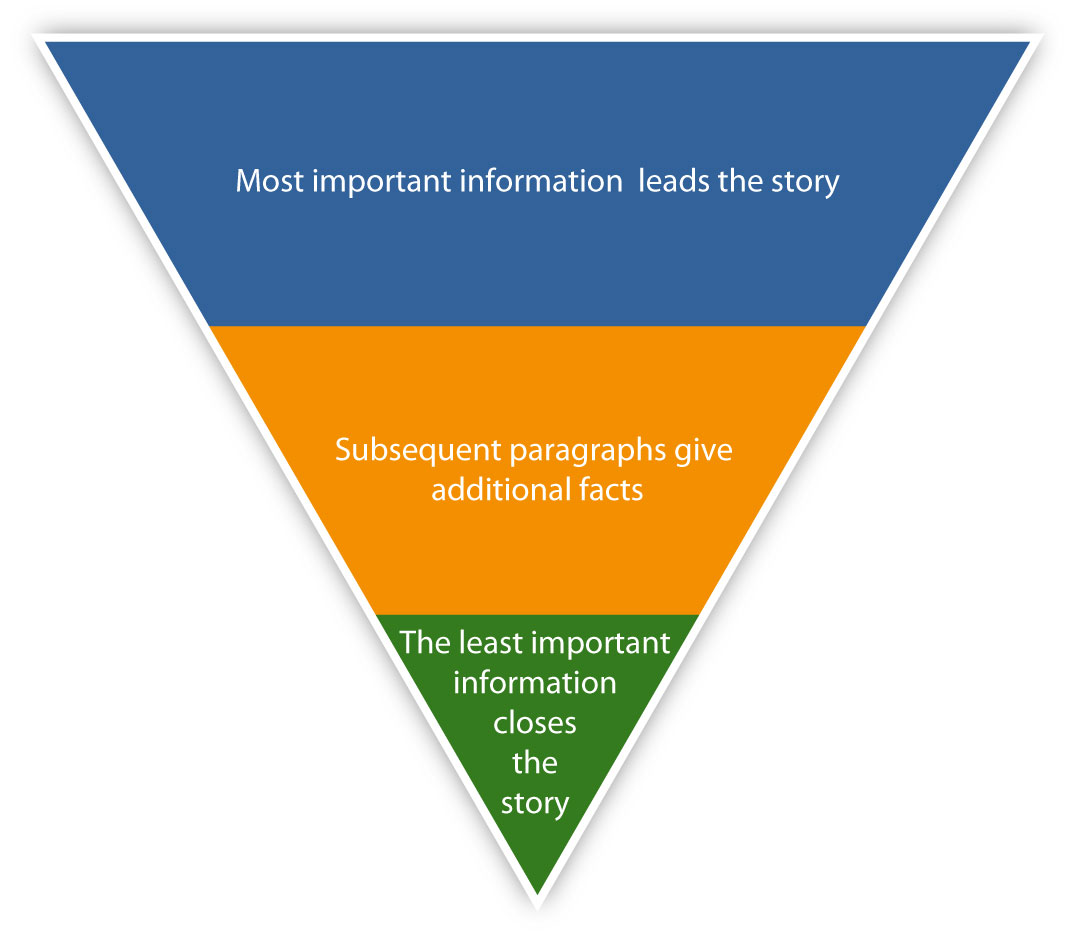

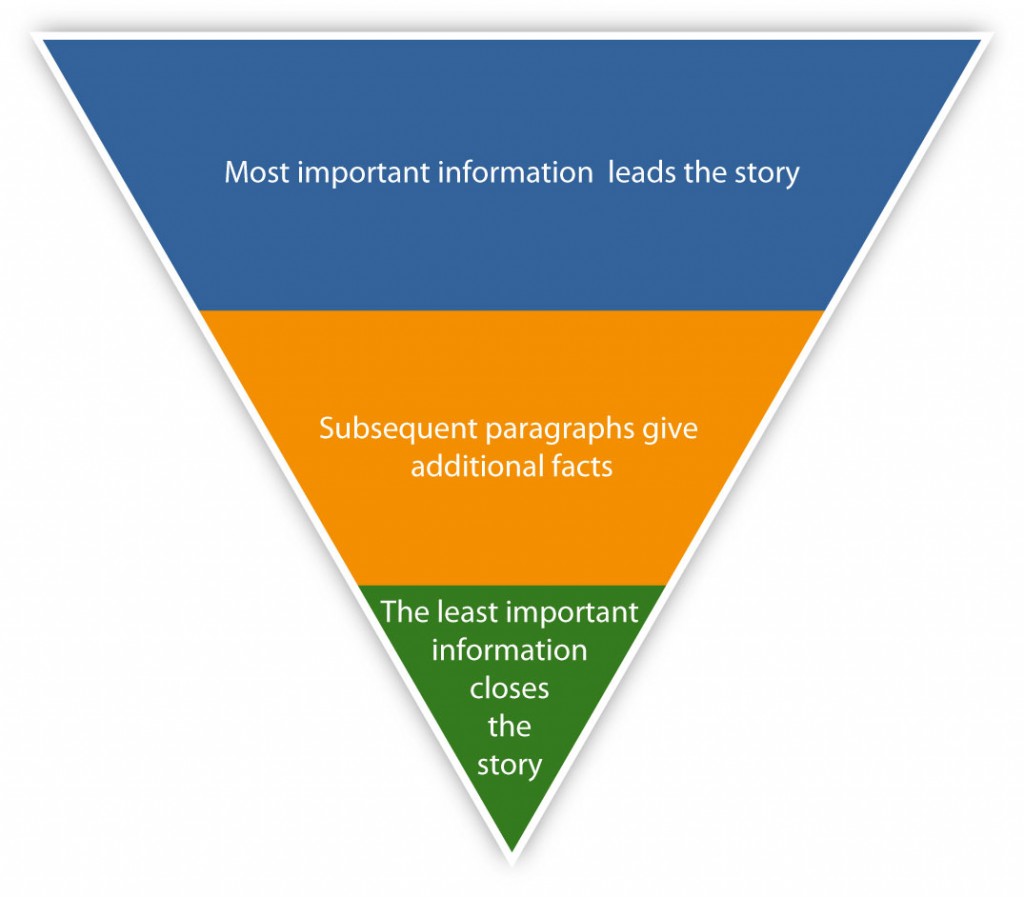

Journalists use a very clear structure for their stories. They start with the most important information (the opening paragraph, above), then expand on that with more detail. Finally, the last section of the article provides more information for anyone who is interested.

This means that you can therefore glean the main elements of any news story from the first paragraph—and decide if you want to read on.

Why the Inverted Pyramid?

The inverted pyramid structure actually stems from print journalism.

If typesetters could not fit the whole story into the space available, they would simply cut off the last few sentences until the article fitted.

Journalists therefore started to write in a way that ensured that the important information would not be removed during this process!

7. Edit your work carefully

The final step in the journalistic writing process is to edit your work yourself before submitting it.

Newsrooms and media outlets generally employ professional editors to check all copy before submitting it. However, journalists also have a responsibility to check their work over before submission to make sure it makes sense.

Read your work over to check that you have written in plain English , and that your meaning is as clear as possible. This will save the sub-editors and editors from having to waste time contacting you for clarifications.

Journalistic Writing Style

As well as a very clear process, journalists also share a common style.

This is NOT the same as the style guidelines used for certain publications (see box), but describes common features of all journalistic writing.

The features of journalistic writing include:

Short sentences . Short sentences are much easier to read and understand than longer ones. Journalists therefore tend to keep their sentences to a line of print or less.

Active voice . The active voice (‘he did x’, rather than ‘x was done by him’) is action-focused, and shorter. It therefore keeps readers’ interest, and makes stories more direct and personal.

Quotes. Most news stories and journalistic writing will include quotes from individuals. This makes the story much more people-focused—which is more likely to keep readers interested. This is why many press releases try to provide quotes (and there is more about this in our page How to Write a Press Release ).

Style guidelines

Most news media have style guidelines. They may share these with other outlets (for example, by using the Associated Press guidelines), or they may have their own (such as the London Times style guide).

These guidelines explain the ‘house style’. This may include, for example, whether the outlet commonly uses an ‘Oxford comma’ or comma placed after the penultimate item in a list, and describe the use of capitals or italics for certain words or phrases.

It is important to be aware of these style guidelines if you are writing for a particular publication.

Journalistic writing is the style used by news outlets to tell factual stories. It uses some established conventions, many of which are driven by the constraints of printing. However, these also work well in internet writing as they grab and hold readers’ attention very effectively.

Continue to: Writing for the Internet Cliches to Avoid

See also: Creative Writing Technical Writing Coherence in Writing

The Art of Journalistic Writing: A Comprehensive Guide ✍️

Journalistic writing aims to provide accurate and objective news coverage to the audience. Learn how to write like journalists in this comprehensive guide.

In the fast-paced realm of freelance writing, captivating and informative articles are the key to setting yourself apart from the competition. That's where the art of journalistic writing becomes your secret weapon.

Below, we'll delve into the significance of journalistic writing for Independents, demystify its definition and various types, explore its essential features, and provide you with invaluable tips to sharpen your skills. Get ready to unlock the power of journalistic writing and take your freelance career to new heights . Let's dive in and discover the magic behind compelling stories that captivate readers worldwide.

What is journalistic writing? 📝

Journalistic writing, as the name implies, is the style of writing used by journalists and news media organizations to share news and information about local, national, and global events, issues, and developments with the public.

The main goal of journalistic writing is to provide accurate and objective news coverage. Journalists gather facts, conduct research, and interview sources to present a fair and unbiased account of events. They strive to deliver information clearly, concisely, and interestingly that grabs readers’ attention and helps them understand the subject.

Journalistic writing also encourages public discussion, critical thinking, and informed decision-making. Since journalists present diverse perspectives, analyze complex issues, and investigate misconduct, they empower readers to form opinions and actively engage with the news. Journalistic writing acts as a watchdog, holding institutions and individuals accountable and promoting transparency in society.

Types of journalistic writing 🔥

Different types of journalism writing styles serve unique purposes, from exposing truths to keeping us informed, sparking conversations, and providing meaningful insights into the world around us.

Here are five types of journalistic writing you should know about:

Investigative journalism 🕵️

Investigative journalists are like detectives in the news world. They dive deep into topics, dedicating their time and resources to uncover hidden information, expose corruption, and bring wrongdoing to the surface.

News journalism 🗞️

News journalists are frontline reporters who inform people about the latest happenings. They cover a wide range of topics, from politics and the economy to science and entertainment. They gather facts, interview sources, and present unbiased information objectively and concisely.

Column journalism 📰

In column journalism, writers share their personal opinions and perspectives on various subjects. They offer analysis, commentary, and insights on social, cultural, or political issues. Whether they are experts in their fields or well-known figures with unique voices, their columns provide readers with different standpoints and spark thought-provoking discussions.

Feature writing 🙇

Feature writers take us beyond the basic facts and immerse us in storytelling. They explore human-interest stories, profiles, and in-depth features on specific topics. They also delve into the personal lives, experiences, or achievements of individuals or communities, providing a deeper understanding of the subject matter by using narrative techniques.

Reviews journalism 📖

Reviewers are the guides helping us make informed decisions about the arts. They evaluate and critique films, books, music, theater shows, and more. Through their opinions and assessments, they analyze the quality, impact, and significance of creative works. Review journalism not only helps us choose what to watch, read, or listen to, but it also contributes to cultural conversations and discussions.

Key features of journalistic writing 🔑

Journalistic writing distinguishes itself from other forms of writing through several essential characteristics. And here are a few:

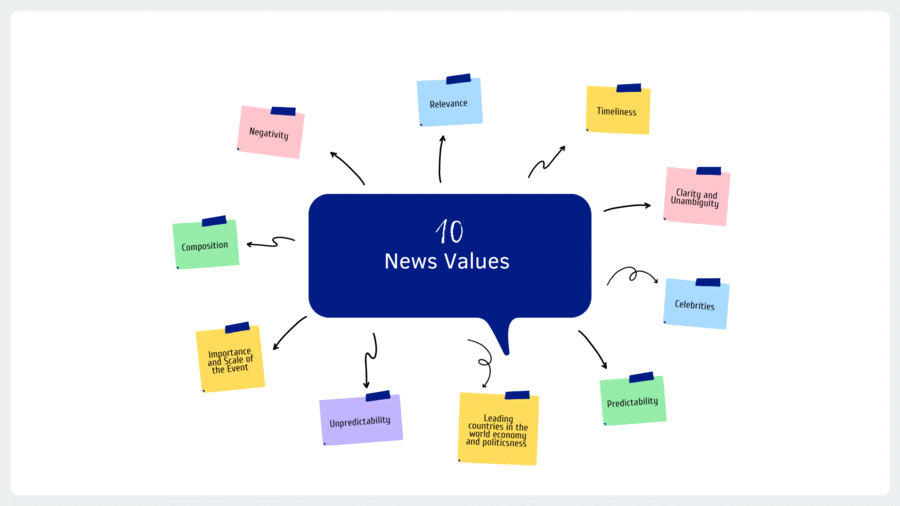

- Accuracy and objectivity: These are of utmost importance. Journalists go to great lengths to gather reliable information, verify sources, and present a balanced perspective. They strive to separate facts from opinions, ensuring readers receive an accurate account of events.

- Timeliness and relevance: Journalists focus on current events and issues that are of interest to the public. They aim to provide up-to-date information, sharing the latest developments and their implications.

- Clarity and conciseness: Journalists use clear and simple language, avoiding complex jargon that might confuse the audience. They use short sentences and paragraphs that enhance readability.

- Inverted pyramid structure: Commonly employed in journalistic writing, this structure places the most important information at the beginning of the article –– in the headline and the first paragraph. Subsequent paragraphs contain supporting details arranged in descending order of significance. By adopting this approach, journalists enable readers to grasp the main points quickly and decide whether to delve deeper into the topic.

- Engagement and impact: Journalists leverage various storytelling techniques, such as vivid descriptions and compelling narratives, to captivate their audience. They incorporate quotes, anecdotes, and human-interest elements to evoke emotions among readers and make the story relatable.

How to write like a journalist: 7 tips 💯

Now that you know the ins and outs of journalistic style and storytelling, let’s explore the best practices to follow during news writing:

1. Use the inverted pyramid structure 🔻

If you’re wondering how to structure and write a news story or article, the answer is simple: Go from the most important to the least important. Start your articles with vital facts, and arrange supporting details in descending order of significance. This structure ensures readers receive essential information even if they don’t read the entire piece.

2. Establish your angle 📐

Before you begin writing , determine the angle or perspective you want to take on the story. Although you should share a neutral opinion, choosing an angle helps you stay focused and deliver a clear message. Consider what makes your story unique or newsworthy, and shape your narrative accordingly.

3. Stick to the facts 🩹

Journalistic writing values accuracy and objectivity. Present information verifiable and supported by credible sources, and avoid personal opinions and biases –– allowing the facts to speak for themselves. Fact-checking is essential to maintain the integrity of your writing.

4. Use quotations to generate credibility 💭

Including quotes from reliable sources adds credibility and depth to your writing. Interview relevant individuals, experts, or eyewitnesses to gather their perspectives and insights. Incorporate their direct quotes to support your narrative and provide first-hand accounts.

5. Write clear and concise sentences 💎

Use straightforward language to effectively communicate your message. Journalism articles typically only include one-to-three sentences per paragraph and should not exceed 20 words per sentence.

6. Edit and revise 💻

Thorough editing is crucial to produce polished and professional journalistic pieces. So once you finish your first draft, invest time on editing and revising your work. Look for grammatical errors, clarity issues, and redundancies. And ensure your writing flows smoothly and maintains a consistent tone.

7. Maintain ethical standards 🏅

You want repeat readers who’ll come back for more from you. And for that, you must keep in mind journalistic principles and share fair, trusting, and accountable pieces. Attribute information to appropriate sources, respect privacy when necessary, and conduct thorough fact-checking.

Write like a pro with Contra 🌟

Mastering the art of journalistic writing is the key to becoming a skilled and impactful freelance writer . By understanding the criticality of thorough research, engaging storytelling, and holding the powerful accountable, you can create compelling news stories that resonate with readers.

And with Contra as your trusted companion, you'll have the tools and resources to refine your journalistic writing skills and take your freelance career to new heights. So don't miss out on the opportunity to write like a pro. Sign up with Contra today, promote your services commission-free, and connect with fellow writers.

Check out Contra for Independents , and join our Slack community to interact with a supportive network of writers, sharing knowledge and learning from each other.

How to Write an Op-Ed: A Guide to Effective Opinion Writing 🖋️

Related articles.

Crafting an Informative Essay: A Comprehensive Guide 📝

What Is Content Writing? Tips to Craft Engaging Content 👀

The 12 Rules Of Grammar Everyone Should Know ✍️

Mastering the White Paper Format: A Step-by-Step Guide 📝

What is a ghostwriter? Everything you need to know 👻

Start your independent journey.

Hire top independents

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

9.2: Different Styles and Models of Journalism

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 115899

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

- Explain how objective journalism differs from story-driven journalism.

- Describe the effect of objectivity on modern journalism.

- Describe the unique nature of literary journalism.

Location, readership, political climate, and competition all contribute to rapid transformations in journalistic models and writing styles. Over time, however, certain styles—such as sensationalism—have faded or become linked with less serious publications, like tabloids, while others have developed to become prevalent in modern-day reporting. This section explores the nuanced differences among the most commonly used models of journalism.

Objective versus Story-Driven Journalism

In the late 1800s, a majority of publishers believed that they would sell more papers by reaching out to specific groups. As such, most major newspapers employed a partisan approach to writing, churning out political stories and using news to sway popular opinion. This all changed in 1896 when a then-failing paper, The New York Times , took a radical new approach to reporting: employing objectivity, or impartiality, to satisfy a wide range of readers.

The Rise of Objective Journalism

At the end of the 19th century, The New York Times found itself competing with the papers of Pulitzer and Hearst. The paper’s publishers discovered that it was nearly impossible to stay afloat without using the sensationalist headlines popularized by its competitors. Although The New York Times publishers raised prices to pay the bills, the higher charge led to declining readership, and soon the paper went bankrupt. Adolph Ochs, owner of the once-failing Chattanooga Times , took a gamble and bought The New York Times in 1896. On August 18 of that year, Ochs made a bold move and announced that the paper would no longer follow the sensationalist style that made Pulitzer and Hearst famous, but instead would be “clean, dignified, trustworthy and impartial.”“Adolph S. Ochs Dead at 77; Publisher of Times Since 1896,” New York Times , April 9, 1935, http://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/bday/0312.html .

This drastic change proved to be a success. T he New York Times became the first of many papers to demonstrate that the press could be “economically as well as ethically successful.”“Adolph S. Ochs Dead at 77; Publisher of Times Since 1896,” New York Times , April 9, 1935, http://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/bday/0312.html . With the help of managing editor Carr Van Anda, the new motto “All the News That’s Fit to Print,” and lowered prices, The New York Times quickly turned into one of the most profitable impartial papers of all time. Since the newspaper’s successful turnaround, publications around the world have followed The New York Times ’ objective journalistic style, demanding that reporters maintain a neutral voice in their writing.

The Inverted Pyramid Style

One commonly employed technique in modern journalism is the inverted pyramid style. This style requires objectivity and involves structuring a story so that the most important details are listed first for ease of reading. In the inverted pyramid format, the most fundamental facts of a story—typically the who, what, when, where, and why—appear at the top in the lead paragraph, with nonessential information in subsequent paragraphs. The style arose as a product of the telegraph. The inverted pyramid proved useful when telegraph connections failed in the middle of transmission; the editor still had the most important information at the beginning. Similarly, editors could quickly delete content from the bottom up to meet time and space requirements.Chip Scanlan, “Writing from the Top Down: Pros and Cons of the Inverted Pyramid,” Poynter, June 20, 2003, www.poynter.org/how-tos/newsg...erted-pyramid/.

The reason for such writing is threefold. First, the style is helpful for writers, as this type of reporting is somewhat easier to complete in the short deadlines imposed on journalists, particularly in today’s fast-paced news business. Second, the style benefits editors who can, if necessary, quickly cut the story from the bottom without losing vital information. Finally, the style keeps in mind traditional readers, most of who skim articles or only read a few paragraphs, but they can still learn most of the important information from this quick read.

Interpretive Journalism

During the 1920s, objective journalism fell under critique as the world became more complex. Even though The New York Times continued to thrive, readers craved more than dry, objective stories. In 1923, Time magazine launched as the first major publication to step away from simple objectivity to try to provide readers with a more analytical interpretation of the news. As Time grew, people at some other publications took notice, and slowly editors began rethinking how they might reach out to readers in an increasingly interrelated world.

During the 1930s, two major events increased the desire for a new style of journalism: the Great Depression and the Nazi threat to global stability. Readers were no longer content with the who, what, where, when, and why of objective journalism. Instead, they craved analysis and a deeper explanation of the chaos surrounding them. Many papers responded with a new type of reporting that became known as interpretive journalism.

Interpretive journalism, following Time ’s example, has grown in popularity since its inception in the 1920s and 1930s, and journalists use it to explain issues and to provide readers with a broader context for the stories that they encounter. According to Brant Houston, the executive director of Investigative Reporters and Editors Inc., an interpretive journalist “goes beyond the basic facts of an event or topic to provide context, analysis, and possible consequences.”Brant Houston, “Interpretive Journalism,” The International Encyclopedia of Communication , 2008, www.blackwellreference.com/pu...3199514_ss82-1. When this new style was first used, readers responded with great interest to the new editorial perspectives that newspapers were offering on events. But interpretive journalism posed a new problem for editors: the need to separate straight objective news from opinions and analysis. In response, many papers in the 1930s and 1940s “introduced weekend interpretations of the past week’s events … and interpretive columnists with bylines.”Stephen J. A. Ward, “Journalism Ethics,” in The Handbook of Journalism Studies , ed. Karin Wahl-Jorgensen and Thomas Hanitzsch (New York: Routledge, 2008): 298. As explained by Stephen J. A. Ward in his article, “Journalism Ethics,” the goal of these weekend features was to “supplement objective reporting with an informed interpretation of world events.”Stephen J. A. Ward, “Journalism Ethics,” in The Handbook of Journalism Studies , ed. Karin Wahl-Jorgensen and Thomas Hanitzsch (New York: Routledge, 2008): 298.

Competition From Broadcasting

The 1930s also saw the rise of broadcasting as radios became common in most U.S. households and as sound–picture recordings for newsreels became increasingly common. This broadcasting revolution introduced new dimensions to journalism. Scholar Michael Schudson has noted that broadcast news “reflect[ed] … a new journalistic reality. The journalist, no longer merely the relayer of documents and messages, ha[d] become the interpreter of the news.”Michael Schudson, “The Politics of Narrative Form: The Emergence of News Conventions in Print and Television,” in “Print Culture and Video Culture,” Daedalus 111, no. 4 (1982): 104. However, just as radio furthered the interpretive journalistic style, it also created a new problem for print journalism, particularly newspapers.

Suddenly, free news from the radio offered competition to the pay news of newspapers. Scholar Robert W. McChesney has observed that, in the 1930s, “many elements of the newspaper industry opposed commercial broadcasting, often out of fear of losing ad revenues and circulation to the broadcasters.”Robert W. McChesney, “Media and Democracy: The Emergence of Commercial Broadcasting in the United States, 1927–1935,” in “Communication in History: The Key to Understanding” OAH Magazine of History 6, no. 4 (1992): 37. This fear led to a media war as papers claimed that radio was stealing their print stories. Radio outlets, however, believed they had equal right to news stories. According to Robert W. McChesney, “commercial broadcasters located their industry next to the newspaper industry as an icon of American freedom and culture.”Robert W. McChesney, “Media and Democracy: The Emergence of Commercial Broadcasting in the United States, 1927–1935,” in “Communication in History: The Key to Understanding” OAH Magazine of History 6, no. 4 (1992): 38. The debate had a major effect on interpretive journalism as radio and newspapers had to make decisions about whether to use an objective or interpretive format to remain competitive with each other.

The emergence of television during the 1950s created even more competition for newspapers. In response, paper publishers increased opinion-based articles, and many added what became known as op-ed pages. An op-ed page—short for opposite the editorial page —features opinion-based columns typically produced by a writer or writers unaffiliated with the paper’s editorial board. As op-ed pages grew, so did interpretive journalism. Distinct from news stories, editors and columnists presented opinions on a regularly basis. By the 1960s, the interpretive style of reporting had begun to replace the older descriptive style.Thomas Patterson, “Why Is News So Negative These Days?” History News Network , 2002, http://hnn.us/articles/1134.html .

Literary Journalism

Stemming from the development of interpretive journalism, literary journalism began to emerge during the 1960s. This style, made popular by journalists Tom Wolfe (formerly a strictly nonfiction writer) and Truman Capote, is often referred to as New Journalism and combines factual reporting with sometimes fictional narration. Literary journalism follows neither the formulaic style of reporting of objective journalism nor the opinion-based analytical style of interpretive journalism. Instead, this art form—as it is often termed—brings voice and character to historical events, focusing on the construction of the scene rather than on the retelling of the facts.

Important Literary Journalists

The works of Tom Wolfe are some of the best examples of literary journalism of the 1960s.

Tom Wolfe was the first reporter to write in the literary journalistic style. In 1963, while his newspaper, New York’s Herald Tribune , was on strike, Esquire magazine hired Wolfe to write an article on customized cars. Wolfe gathered the facts but struggled to turn his collected information into a written piece. His managing editor, Byron Dobell, suggested that he type up his notes so that Esquire could hire another writer to complete the article. Wolfe typed up a 49-page document that described his research and what he wanted to include in the story and sent it to Dobell. Dobell was so impressed by this piece that he simply deleted the “Dear Byron” at the top of the letter and published the rest of Wolfe’s letter in its entirety under the headline “There Goes (Varoom! Varoom!) That Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby.” The article was a great success, and Wolfe, in time, became known as the father of new journalism. When he later returned to work at the Herald Tribune , Wolfe brought with him this new style, “fusing the stylistic features of fiction and the reportorial obligations of journalism.”Richard A. Kallan, “Tom Wolfe,” in A Sourcebook of American Literary Journalism: Representative Writers in an Emerging Genre , ed. Thomas B. Connery (Santa Barbara: Greenwood Press, 1992).

Truman Capote responded to Wolfe’s new style by writing In Cold Blood , which Capote termed a “nonfiction novel,” in 1966.George Plimpton, “The Story Behind a Nonfiction Novel,” New York Times , January 16, 1966, http://www.nytimes.com/books/97/12/28/home/capote-interview.html . The tale of an actual murder that had taken place on a Kansas farm some years earlier, the novel was based on numerous interviews and painstaking research. Capote claimed that he wrote the book because he wanted to exchange his “self-creative world … for the everyday objective world we all inhabit.”George Plimpton, “The Story Behind a Nonfiction Novel,” New York Times , January 16, 1966, http://www.nytimes.com/books/97/12/28/home/capote-interview.html . The book was praised for its straightforward, journalistic style. New York Times writer George Plimpton claimed that the book “is remarkable for its objectivity—nowhere, despite his involvement, does the author intrude.”George Plimpton, “The Story Behind a Nonfiction Novel,” New York Times , January 16, 1966, http://www.nytimes.com/books/97/12/28/home/capote-interview.html . After In Cold Blood was finished, Capote criticized Wolfe’s style in an interview, commenting that Wolfe “[has] nothing to do with creative journalism,” by claiming that Wolfe did not have the appropriate fiction-writing expertise.George Plimpton, “The Story Behind a Nonfiction Novel,” New York Times , January 16, 1966, http://www.nytimes.com/books/97/12/28/home/capote-interview.html . Despite the tension between these two writers, today they are remembered for giving rise to a similar style in varying genres.

The Effects of Literary Journalism

Although literary journalism certainly affected newspaper reporting styles, it had a much greater impact on the magazine industry. Because they were bound by fewer restrictions on length and deadlines, magazines were more likely to publish this new writing style than were newspapers. Indeed, during the 1960s and 1970s, authors simulating the styles of both Wolfe and Capote flooded magazines such as Esquire and The New Yorker with articles.

Literary journalism also significantly influenced objective journalism. Many literary journalists believed that objectivity limited their ability to critique a story or a writer. Some claimed that objectivity in writing is impossible, as all journalists are somehow swayed by their own personal histories. Still others, including Wolfe, argued that objective journalism conveyed a “limited conception of the ‘facts,’” which “often effected an inaccurate, incomplete story that precluded readers from exercising informed judgment.”Richard A. Kallan, “Tom Wolfe,” in A Sourcebook of American Literary Journalism: Representative Writers in an Emerging Genre , ed. Thomas B. Connery (Santa Barbara: Greenwood Press, 1992).

Advocacy Journalism and Precision Journalism

The reactions of literary journalists to objective journalism encouraged the growth of two more types of journalism: advocacy journalism and precision journalism. Advocacy journalists promote a particular cause and intentionally adopt a biased, nonobjective viewpoint to do so effectively. However, serious advocate journalists adhere to strict guidelines, as “an advocate journalist is not the same as being an activist” according to journalist Sue Careless.Sue Careless, “Advocacy Journalism,” Interim , May 2000, www.theinterim.com/2000/may/10advocacy.html. In an article discussing advocacy journalism, Careless contrasted the role of an advocate journalist with the role of an activist. She encourages future advocate journalists by saying the following:

A journalist writing for the advocacy press should practice the same skills as any journalist. You don’t fabricate or falsify. If you do you will destroy the credibility of both yourself as a working journalist and the cause you care so much about. News should never be propaganda. You don’t fudge or suppress vital facts or present half-truths.Sue Careless, “Advocacy Journalism,” Interim , May 2000, www.theinterim.com/2000/may/10advocacy.html.

Despite the challenges and potential pitfalls inherent to advocacy journalism, this type of journalism has increased in popularity over the past several years. In 2007, USA Today reporter Peter Johnson stated, “[i]ncreasingly, journalists and talk-show hosts want to ‘own’ a niche issue or problem, find ways to solve it, and be associated with making this world a better place.”Peter Johnson, “More Reporters Embrace an Advocacy Role,” USA Today , March 5, 2007, http://www.usatoday.com/life/television/news/2007-03-05-social-journalism_N.htm . In this manner, journalists across the world are employing the advocacy style to highlight issues they care about.

Oprah Winfrey: Advocacy Journalist

Television talk-show host and owner of production company Harpo Inc., Oprah Winfrey is one of the most successful, recognizable entrepreneurs of the late-20th and early-21st centuries. Winfrey has long been a news reporter, beginning in the late 1970s as a coanchor of an evening television program. She began hosting her own show in 1984, and as of 2010, the Oprah Winfrey Show is one of the most popular television programs on the air. Winfrey has long used her show as a platform for issues and concerns, making her one of today’s most famous advocacy journalists. While many praise Winfrey for using her celebrity to draw attention to causes she cares about, others criticize her techniques, claiming that she uses the advocacy style for self-promotion. As one critic writes, “I’m not sure how Oprah’s endless self-promotion of how she spent millions on a school in South Africa suddenly makes her ‘own’ the ‘education niche.’ She does own the trumpet-my-own-horn niche. But that’s not ‘journalism.’”Debbie Schlussel, “USA Today Heralds ‘Oprah Journalism,’” Debbie Schlussel (blog), March 6, 2007, http://www.debbieschlussel.com/497/usa-today-heralds-oprah-journalism/ .

Yet despite this somewhat harsh critique, many view Winfrey as the leading example of positive advocacy journalism. Sara Grumbles claims in her blog “Breaking and Fitting the Mold”: “Oprah Winfrey obviously practices advocacy journalism…. Winfrey does not fit the mold of a ‘typical’ journalist by today’s standards. She has an agenda and she voices her opinions. She has her own op-ed page in the form of a million dollar television studio. Objectivity is not her strong point. Still, in my opinion she is a journalist.”Sara Grumbles, “Breaking and Fitting the Mold,” Media Chatter (blog), October 3, 2007, www.commajor.com/?p=1244.

Regardless of the arguments about the value and reasoning underlying her technique, Winfrey unquestionably practices a form of advocacy journalism. In fact, thanks to her vast popularity, she may be the most compelling example of an advocacy journalist working today.

Precision journalism emerged in the 1970s. In this form, journalists turn to polls and studies to strengthen the accuracy of their articles. Philip Meyer, commonly acknowledged as the father of precision journalism, says that his intent is to “encourage my colleagues in journalism to apply the principles of scientific method to their tasks of gathering and presenting the news.”Philip Meyer, Precision Journalism: A Reporter’s Introduction to Social Science Methods , 4th ed. (Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2002), vii. This type of journalism adds a new layer to objectivity in reporting, as articles no longer need to rely solely on anecdotal evidence; journalists can employ hard facts and figures to support their assertions. An example of precision journalism would be an article on voting patterns in a presidential election that cites data from exit polls. Precision journalism has become more popular as computers have become more prevalent. Many journalists currently use this type of writing.

Consensus versus Conflict Newspapers

Another important distinction within the field of journalism must be made between consensus journalism and conflict journalism. Consensus journalism typically takes place in smaller communities, where local newspapers generally serve as a forum for many different voices. Newspapers that use consensus-style journalism provide community calendars and meeting notices and run articles on local schools, events, government, property crimes, and zoning. These newspapers can help build civic awareness and a sense of shared experience and responsibility among readers in a community. Often, business or political leaders in the community own consensus papers.

Conversely, conflict journalism, like that which is presented in national and international news articles in The New York Times , typically occurs in national or metropolitan dailies. Conflict journalists define news in terms of societal discord, covering events and issues that contravene perceived social norms. In this style of journalism, reporters act as watchdogs who monitor the government and its activities. Conflict journalists often present both sides of a story and pit ideas against one another to generate conflict and, therefore, attract a larger readership. Both conflict and consensus papers are widespread. However, because they serve different purposes and reach out to differing audiences, they largely do not compete with each other.

Niche Newspapers

Niche newspapers represent one more model of newspapers. These publications, which reach out to a specific target group, are rising in popularity in the era of Internet. As Robert Courtemanche, a certified journalism educator, writes, “[i]n the past, newspapers tried to be everything to every reader to gain circulation. That outdated concept does not work on the Internet where readers expect expert, niche content.”Robert Courtemanche, “Newspapers Must Find Their Niche to Survive,” Suite101.com, December 20, 2008, http://newspaperindustry.suite101.co...che_to_survive . Ethnic and minority papers are some of the most common forms of niche newspapers. In the United States—particularly in large cities such as New York—niche papers for numerous ethnic communities flourish. Some common types of U.S. niche papers are papers that cater to a specific ethnic or cultural group or to a group that speaks a particular language. Papers that cover issues affecting lesbians, gay men, and bisexual individuals—like the Advocate —and religion-oriented publications—like The Christian Science Monitor —are also niche papers.

The Underground Press

Some niche papers are part of the underground press. Popularized in the 1960s and 1970s as individuals sought to publish articles documenting their perception of social tensions and inequalities, the underground press typically caters to alternative and countercultural groups. Most of these papers are published on small budgets. Perhaps the most famous underground paper is New York’s Pulitzer Prize–winning Village Voice . This newspaper was founded in 1955 and declares its role in the publishing industry by saying:

The Village Voice introduced free-form, high-spirited and passionate journalism into the public discourse. As the nation’s first and largest alternative newsweekly, the Voice maintains the same tradition of no-holds-barred reporting and criticism it first embraced when it began publishing fifty years ago. Village Voice , “About Us,” www.villagevoice.com/about/index.

Despite their at-times shoestring budgets, underground papers serve an important role in the media. By offering an alternative perspective to stories and by reaching out to niche groups through their writing, underground-press newspapers fill a unique need within the larger media marketplace. As journalism has evolved over the years, newspapers have adapted to serve the changing demands of readers.

Key Takeaways

- Objective journalism began as a response to sensationalism and has continued in some form to this day. However, some media observers have argued that it is nearly impossible to remain entirely objective while reporting a story. One argument against objectivity is that journalists are human and are, therefore, biased to some degree. Many newspapers that promote objectivity put in place systems to help their journalists remain as objective as possible.

- Literary journalism combines the research and reporting of typical newspaper journalism with the writing style of fiction. While most newspaper journalists focus on facts, literary journalists tend to focus on the scene by evoking voices and characters inhabiting historical events. Famous early literary journalists include Tom Wolfe and Truman Capote.

- Other journalistic styles allow reporters and publications to narrow their editorial voice. Advocacy journalists encourage readers to support a particular cause. Consensus journalism encourages social and economic harmony, while conflict journalists present information in a way that focuses on views outside of the social norm.

- Niche newspapers—such as members of the underground press and those serving specific ethnic groups, racial groups, or speakers of a specific language—serve as important media outlets for distinct voices. The rise of the Internet and online journalism has brought niche newspapers more into the mainstream.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Please respond to the following writing prompts. Each response should be a minimum of one paragraph.

- Find an objective newspaper article that includes several factual details. Rewrite the story in a literary journalistic style. How does the story differ from one genre to the other?

- Was it difficult to transform an objective story into a piece of literary journalism? Explain.

- Do you prefer reading an objective journalism piece or a literary journalism piece? Explain.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

TIMES INSIDER

A Reporter Explains His Approach to Writing News and Features

Brooks Barnes, a correspondent who covers Hollywood for The Times, explains how his writing process changes depending on the type of article he is working on.

By Sarah Bahr

Times Insider explains who we are and what we do, and delivers behind-the-scenes insights into how our journalism comes together.

Brooks Barnes’s head is constantly on a swivel.

As a domestic correspondent covering Hollywood’s leading celebrities, companies and executives for The New York Times, he writes both daily news articles about media companies and long-lead features about subjects such as Walt Disney World’s animatronic robot crew and the Polo Lounge , a Hollywood hot spot that attracts the who’s who of the film industry.

Those two types of articles — news and features — are the yin and yang of journalism. As the name suggests, news articles provide readers with new information about important events, often as they unfold. They can cover nearly any topic, are generally 500 to 1,000 words long and are packed with the need-to-know facts of a given situation. Features, which need not be tied to a specific event, dive deep into a particular topic or person, are usually longer than news articles and often offer more comprehensive context about their subjects.

Every day, The Times publishes both. While many journalists specialize in writing news or feature articles, Mr. Barnes flips between the two.

“I have eight to 10 features on the assembly line at any given time,” Mr. Barnes said, adding that he often has to drop what he’s working on to chase the news and that he focuses on writing features when the news is slow. Generally, he can finish a news article in a couple of hours or less; a major feature can take upward of six months.

For Mr. Barnes, the main difference between a news article and a feature isn’t the word count, the number of interviews involved or how long he spends drafting it: “The writing process changes,” he says.

Interviewing Sources

A news article is all about gathering the essential information and publishing quickly.

He begins working on a news article by making calls to sources, often contacts he has built up over more than 20 years of reporting. He says he jots down his most important questions before he calls a source, even if he’s on a deadline and knows the conversation will only last a few minutes.

For a feature, Mr. Barnes said he will do around 10 interviews, not all of which may appear in the final article. If he’s writing a profile, he aims to spend a few hours with his subject on a Friday or Saturday, when the person is more relaxed and available.

As with news articles, he writes out his interview questions in advance, though he tries not to do too much research before meeting a profile subject for the first time so that he won’t come into the interview with a preconceived idea of what the subject might say.

“You want to report, not interview your thumb,” he said.

Getting Down to Writing

Mr. Barnes never outlines his news or feature articles, but instead works off his notes, which he’ll consult as he’s writing.

He gathers all of his notes from his interviews and research, both typed and handwritten, and inputs the best quotes, facts and figures into a Microsoft Word document. Unlike a news article, a feature may involve several attempts at a compelling first few sentences — known as the lede — and lots of rewriting. “I’ve been known to fixate on a lede for much longer than I should,” he said.

Structurally, a news article is much more straightforward than a feature: In a news article, the most important and timely information appears in the first few sentences, with the remaining facts generally provided in descending order of importance. In a feature, by contrast, the writer often delays the revelation of certain details in order to build suspense.

Landing on the Voice

Another difference, Mr. Barnes said, is the voice that he interjects — or doesn’t — into an article. A news article is usually devoid of personal flavor, while a feature can be saturated with it. He says he sometimes tries to “self-censor” his voice in a news article. In a feature, there is room for more lyrical description; Mr. Barnes is able to dwell on how a subject dresses, talks and reacts to his questions.

Working on Edits

The editing process also differs. With features, it can involve lots of fine-tuning: Ledes may be thrown out and paragraphs rewritten. With a news article, an editor acts more like a safety net than a pruner or a polisher, ensuring that reporters on deadline aren’t overlooking important information or relevant questions, and that they aren’t committing any obvious factual errors.

Enjoying Both Forms

The greatest challenge in writing a news article, in Mr. Barnes’s opinion, is achieving both speed and accuracy on deadline. Features present a different conundrum: A writer must carefully condense hours of interviews and research into a gripping-yet-accurate narrative that doesn’t get bogged down with superfluous information.

Though Mr. Barnes says he enjoys both forms, he’s always had a clear preference.

“I’m a feature writer who’s somehow managed not to get fired as a business reporter for 20 years,” he said.

He added: “I like luxuriating over words and trying different stuff. I could tinker with a story forever.”

Writers' Center

Eastern Washington University

Journalistic Writing

The inverted pyramid.

- Common AP Style Tips

[ Back to resource home ]

[email protected] 509.359.2779

Cheney Campus JFK Library Learning Commons

Stay Connected!

inside.ewu.edu/writerscenter Instagram Facebook

Helpful Links

Associated Press Stylebook Online (needs a subscription): apstylebook.com

Associated Press Style Resources (free): AP Style - Purdue OWL® - Purdue University

Example Articles: http://www.nytimes.com/

Common AP Style Tips: http://research.ewu.edu/c.php?g=403887&p=2749023

Many organizations use the Associated Press Style (AP Style) in their communication within their company and to the public. AP Style is important to know and understand for work in many different sectors, not just in newspaper and media organizations.

Journalism writing is simply writing well and adhering to AP Style. The real trick is to learn how to write concisely. Most readers don’t finish reading an entire article from beginning to end, so journalists must adjust to quickly conveying important information. There are two ways journalists combat this: concise sentences and the inverted pyramid.

The inverted pyramid is a traditional and often the most-used organizing structure for journalistic writing. The inverted pyramid places the more newsworthy information — the information people really need to know — at the very beginning of the article. The middle of the pyramid, and the middle of the article, is filled with other important information necessary to telling the story. The very bottom of the story is the least important information of the story.

When journalism content was strictly print based, journalists used the inverted pyramid for writing. Page designers would hand place the layout of each newspaper page. If the story was too long to fit in the allotted space of the page design, they would simply cut off the bottom of the article. By placing the least important information at the bottom of the story, journalists ensured the least important information was the part that was cut while the more important remained.

The beginning one to two sentences are referred to as the “lead” of the article. In the lead, most of the 5 W’s are answered: who, what, when, where and why. Because the lead needs to be kept short (one to two short sentences), some of that information may be forced to be included further down in the article.

The middle of the article, and the middle piece of the inverted pyramid, is referred to as the body. The body of the article is the bulk of information that tells the rest of the story that wouldn’t fit in the lead. It contains information pertinent to the story.

The very end of an article is referred to as the tail, which is the bottom segment of the inverted pyramid. The tail is the least important information that pertains to the article. For example, the tail may contain information for an upcoming event related to the article or contact information for the reader to ask more questions.

By Inverted_pyramid.jpg: The Air Force Departmental Publishing Office ( AFDPO )derivative work: Makeemlighter (Inverted_pyramid.jpg) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

- Next: Common AP Style Tips >>

- Last Updated: Apr 25, 2024 2:50 PM

- URL: https://research.ewu.edu/writers_c_journalistic_writing

How to Write a Journalism Article: A Step-by-Step Guide

Feeling behind on ai.

You're not alone. The Neuron is a daily AI newsletter that tracks the latest AI trends and tools you need to know. Join 400,000+ professionals from top companies like Microsoft, Apple, Salesforce and more. 100% FREE.

If you're looking to write a journalism article but aren't sure where to start, this guide has got you covered. In this step-by-step guide, we'll take you through the essentials of journalism, from identifying a newsworthy topic to crafting a strong headline and structuring your article. By the end, you'll have the tools you need to write a compelling journalism piece.

Understanding the Basics of Journalism

Journalism is a crucial part of our society, providing us with the information we need to make informed decisions and stay up-to-date on current events. Whether you're a seasoned journalist or just starting out, it's important to have a solid understanding of the basics of journalism.

The Role of a Journalist

As a journalist, your primary responsibility is to gather and report news. This can involve conducting interviews, researching information, and writing articles that inform the public about important issues. Journalists are often called the "watchdogs of society," as they play a crucial role in holding those in power accountable and shining a light on injustices.

However, with great power comes great responsibility. It's essential that journalists approach their work with a sense of fairness, accuracy, and impartiality. This means avoiding biases and reporting the facts as objectively as possible.

Types of Journalism Articles

There are many different types of journalism articles, each with its own unique structure and purpose. Some common types include:

- News articles: These articles are typically short and to the point, reporting on breaking news or current events.

- Feature stories: Feature stories are longer, more in-depth articles that explore a particular topic or issue in detail.

- Opinion pieces: Opinion pieces are articles that express the author's personal views on a particular topic.

- Investigative reports: Investigative reports are in-depth pieces of journalism that require extensive research and often involve uncovering hidden or sensitive information.

When deciding what type of article to write, it's important to consider the topic and your own writing style. Some topics may lend themselves better to a news article, while others may require a more in-depth feature story or investigative report.

Ethical Considerations in Journalism

Journalists must adhere to a strict code of ethics to ensure their work is fair, accurate, and unbiased. Some key ethical considerations include:

- Avoiding conflicts of interest: Journalists should avoid situations where their personal interests may conflict with their reporting.

- Protecting sources: It's important for journalists to protect their sources, as this allows them to gather information that may otherwise remain hidden.

- Fact-checking: Before publishing any information, journalists should always fact-check to ensure its accuracy.

As a journalist, it's your responsibility to maintain the integrity of your work. By following these ethical considerations, you can ensure that your reporting is fair, accurate, and trustworthy.

Choosing a Compelling Story Idea

Journalism is an art that requires skill, creativity, and a nose for newsworthy topics. As a journalist, the first step in writing a great article is identifying a topic that will capture your readers' attention and keep them engaged. Here are some tips to help you choose a compelling story idea:

Identifying Newsworthy Topics

The world is constantly changing, and there is always something happening that could be of interest to your readers. When choosing a topic, consider what is happening in your community, your country, and the world. Look for current events, human interest stories, and issues that are important to your readers. Ask yourself, "What will interest my readers?" and "What is important to them?"

For example, if you are writing for a local newspaper, you might focus on issues that affect your community, such as local politics, crime, or events. If you are writing for a national or international audience, you might focus on broader topics, such as world events, social issues, or scientific breakthroughs.

Finding Unique Angles

Once you have identified a topic, it's important to find a unique angle that will make your article stand out. This could be an innovative perspective, a human interest angle, or an in-depth analysis of a complex issue. The key is to find an angle that is both interesting and relevant to your readers.

For example, if you are writing about a political issue, you might focus on the impact of the issue on a particular demographic, such as young people or seniors. If you are writing about a scientific breakthrough, you might focus on the implications of the breakthrough for society as a whole.

Conducting Preliminary Research

Before you start writing, it's important to conduct some preliminary research on your topic. This could involve reading news articles, consulting experts, or conducting interviews with sources. The more you know about your topic, the more informed and compelling your writing will be.

For example, if you are writing about a local crime, you might consult with law enforcement officials, witnesses, and victims to get a better understanding of the situation. If you are writing about a scientific breakthrough, you might consult with researchers and experts in the field to get a better understanding of the implications of the breakthrough.

Remember, the key to writing a great journalism article is to choose a compelling story idea, find a unique angle, and conduct thorough research. By following these steps, you can create articles that inform, engage, and inspire your readers.

Conducting Thorough Research

Interviewing sources.

One of the most important aspects of journalism is interviewing sources. When conducting interviews, it's important to ask open-ended questions and to listen actively to the responses. Don't be afraid to follow up with additional questions if you need clarification.

Fact-Checking and Verification

Once you've conducted your research, it's important to fact-check all information before publishing. This involves verifying the accuracy of your sources and conducting additional research if necessary. Always double-check quotes, statistics, and other important information.

Organizing Your Research

Once you've completed your research, it's important to organize your notes and sources into a logical structure. This could involve creating an outline, a mind map, or a series of notes. The key is to have a clear and organized structure that will guide your writing process.

Writing the Journalism Article

Crafting a strong headline.

Your headline is one of the most important parts of your article, as it is what will draw readers in. A strong headline should be clear, concise, and attention-grabbing. Consider using action verbs, numbers, and intriguing adjectives to make your headline stand out.

Structuring Your Article

Once you've crafted a strong headline, it's important to structure your article in a clear and logical way. This could involve starting with a strong lead, breaking your article down into subheadings, and using quotes and statistics to support your claims.

Writing an Engaging Lead

Your lead is what will hook your readers and encourage them to continue reading. A strong lead should be concise, interesting, and informative. Consider using a startling statistic, a provocative quote, or a compelling anecdote to grab your readers' attention.

Developing the Body of the Article

The body of your article should provide detailed information on your topic, supported by sources and statistics. It's important to use clear and concise language, avoiding jargon or overly complex wording. Break your article down into several subheadings to make it easier to follow.

Concluding Your Article

Finally, it's important to wrap up your article with a strong conclusion that ties everything together. Your conclusion should summarize your main points and offer some final thoughts or recommendations. Avoid introducing new information in your conclusion and aim to leave your readers with something to think about.

By following these steps, you can write a compelling journalism article that informs and engages your readers. Remember to stick to ethical guidelines, conduct thorough research, and write in a clear and engaging style. With practice, you'll be on your way to becoming a skilled and respected journalist.

ChatGPT Prompt for Writing a Journalism Article

Use the following prompt in an AI chatbot . Below each prompt, be sure to provide additional details about your situation. These could be scratch notes, what you'd like to say or anything else that guides the AI model to write a certain way.

Produce a comprehensive and high-quality piece of writing that follows the conventions of journalism, with the aim of informing and engaging readers on a particular topic or issue. Your article should be well-researched, balanced, and objective, and should adhere to the principles of accuracy, fairness, and impartiality. Consider the target audience and the publication or platform for which you are writing, and ensure that your article is structured, compelling, and thought-provoking.

[ADD ADDITIONAL CONTEXT. CAN USE BULLET POINTS.]

You Might Also Like...

How to write a knowledge base article: a step-by-step guide, how to write a law review article: a step-by-step guide.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

4.3 Different Styles and Models of Journalism

Learning objectives.

- Explain how objective journalism differs from story-driven journalism.

- Describe the effect of objectivity on modern journalism.

- Describe the unique nature of literary journalism.

Location, readership, political climate, and competition all contribute to rapid transformations in journalistic models and writing styles. Over time, however, certain styles—such as sensationalism—have faded or become linked with less serious publications, like tabloids, while others have developed to become prevalent in modern-day reporting. This section explores the nuanced differences among the most commonly used models of journalism.

Objective versus Story-Driven Journalism

In the late 1800s, a majority of publishers believed that they would sell more papers by reaching out to specific groups. As such, most major newspapers employed a partisan approach to writing, churning out political stories and using news to sway popular opinion. This all changed in 1896 when a then-failing paper, The New York Times , took a radical new approach to reporting: employing objectivity , or impartiality, to satisfy a wide range of readers.

The Rise of Objective Journalism

At the end of the 19th century, The New York Times found itself competing with the papers of Pulitzer and Hearst. The paper’s publishers discovered that it was nearly impossible to stay afloat without using the sensationalist headlines popularized by its competitors. Although The New York Times publishers raised prices to pay the bills, the higher charge led to declining readership, and soon the paper went bankrupt. Adolph Ochs, owner of the once-failing Chattanooga Times , took a gamble and bought The New York Times in 1896. On August 18 of that year, Ochs made a bold move and announced that the paper would no longer follow the sensationalist style that made Pulitzer and Hearst famous, but instead would be “clean, dignified, trustworthy and impartial (New York Times, 1935).”

This drastic change proved to be a success. The New York Times became the first of many papers to demonstrate that the press could be “economically as well as ethically successful (New York Times, 1935).” With the help of managing editor Carr Van Anda, the new motto “All the News That’s Fit to Print,” and lowered prices, The New York Times quickly turned into one of the most profitable impartial papers of all time. Since the newspaper’s successful turnaround, publications around the world have followed The New York Times ’ objective journalistic style, demanding that reporters maintain a neutral voice in their writing.

The Inverted Pyramid Style

One commonly employed technique in modern journalism is the inverted pyramid style . This style requires objectivity and involves structuring a story so that the most important details are listed first for ease of reading. In the inverted pyramid format, the most fundamental facts of a story—typically the who, what, when, where, and why—appear at the top in the lead paragraph, with nonessential information in subsequent paragraphs. The style arose as a product of the telegraph. The inverted pyramid proved useful when telegraph connections failed in the middle of transmission; the editor still had the most important information at the beginning. Similarly, editors could quickly delete content from the bottom up to meet time and space requirements (Scanlan, 2003).

The reason for such writing is threefold. First, the style is helpful for writers, as this type of reporting is somewhat easier to complete in the short deadlines imposed on journalists, particularly in today’s fast-paced news business. Second, the style benefits editors who can, if necessary, quickly cut the story from the bottom without losing vital information. Finally, the style keeps in mind traditional readers, most of who skim articles or only read a few paragraphs, but they can still learn most of the important information from this quick read.

Interpretive Journalism

During the 1920s, objective journalism fell under critique as the world became more complex. Even though The New York Times continued to thrive, readers craved more than dry, objective stories. In 1923, Time magazine launched as the first major publication to step away from simple objectivity to try to provide readers with a more analytical interpretation of the news. As Time grew, people at some other publications took notice, and slowly editors began rethinking how they might reach out to readers in an increasingly interrelated world.

During the 1930s, two major events increased the desire for a new style of journalism: the Great Depression and the Nazi threat to global stability. Readers were no longer content with the who, what, where, when, and why of objective journalism. Instead, they craved analysis and a deeper explanation of the chaos surrounding them. Many papers responded with a new type of reporting that became known as interpretive journalism .

Interpretive journalism, following Time ’s example, has grown in popularity since its inception in the 1920s and 1930s, and journalists use it to explain issues and to provide readers with a broader context for the stories that they encounter. According to Brant Houston, the executive director of Investigative Reporters and Editors Inc., an interpretive journalist “goes beyond the basic facts of an event or topic to provide context, analysis, and possible consequences (Houston, 2008).” When this new style was first used, readers responded with great interest to the new editorial perspectives that newspapers were offering on events. But interpretive journalism posed a new problem for editors: the need to separate straight objective news from opinions and analysis. In response, many papers in the 1930s and 1940s “introduced weekend interpretations of the past week’s events…and interpretive columnists with bylines (Ward, 2008).” As explained by Stephen J. A. Ward in his article, “Journalism Ethics,” the goal of these weekend features was to “supplement objective reporting with an informed interpretation of world events (Ward, 2008).”

Competition From Broadcasting

The 1930s also saw the rise of broadcasting as radios became common in most U.S. households and as sound–picture recordings for newsreels became increasingly common. This broadcasting revolution introduced new dimensions to journalism. Scholar Michael Schudson has noted that broadcast news “reflect[ed]…a new journalistic reality. The journalist, no longer merely the relayer of documents and messages, ha[d] become the interpreter of the news (Schudson, 1982).” However, just as radio furthered the interpretive journalistic style, it also created a new problem for print journalism, particularly newspapers.

Suddenly, free news from the radio offered competition to the pay news of newspapers. Scholar Robert W. McChesney has observed that, in the 1930s, “many elements of the newspaper industry opposed commercial broadcasting, often out of fear of losing ad revenues and circulation to the broadcasters (McChesney, 1992).” This fear led to a media war as papers claimed that radio was stealing their print stories. Radio outlets, however, believed they had equal right to news stories. According to Robert W. McChesney, “commercial broadcasters located their industry next to the newspaper industry as an icon of American freedom and culture (McChesney, 1992).” The debate had a major effect on interpretive journalism as radio and newspapers had to make decisions about whether to use an objective or interpretive format to remain competitive with each other.

The emergence of television during the 1950s created even more competition for newspapers. In response, paper publishers increased opinion-based articles, and many added what became known as op-ed pages. An op-ed page—short for opposite the editorial page —features opinion-based columns typically produced by a writer or writers unaffiliated with the paper’s editorial board. As op-ed pages grew, so did interpretive journalism. Distinct from news stories, editors and columnists presented opinions on a regular basis. By the 1960s, the interpretive style of reporting had begun to replace the older descriptive style (Patterson, 2002).

Literary Journalism

Stemming from the development of interpretive journalism, literary journalism began to emerge during the 1960s. This style, made popular by journalists Tom Wolfe (formerly a strictly nonfiction writer) and Truman Capote, is often referred to as new journalism and combines factual reporting with sometimes fictional narration. Literary journalism follows neither the formulaic style of reporting of objective journalism nor the opinion-based analytical style of interpretive journalism. Instead, this art form—as it is often termed—brings voice and character to historical events, focusing on the construction of the scene rather than on the retelling of the facts.

Important Literary Journalists

The works of Tom Wolfe are some of the best examples of literary journalism of the 1960s.

erin williamson – tom wolfe – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Tom Wolfe was the first reporter to write in the literary journalistic style. In 1963, while his newspaper, New York’s Herald Tribune , was on strike, Esquire magazine hired Wolfe to write an article on customized cars. Wolfe gathered the facts but struggled to turn his collected information into a written piece. His managing editor, Byron Dobell, suggested that he type up his notes so that Esquire could hire another writer to complete the article. Wolfe typed up a 49-page document that described his research and what he wanted to include in the story and sent it to Dobell. Dobell was so impressed by this piece that he simply deleted the “Dear Byron” at the top of the letter and published the rest of Wolfe’s letter in its entirety under the headline “There Goes (Varoom! Varoom!) That Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby.” The article was a great success, and Wolfe, in time, became known as the father of new journalism. When he later returned to work at the Herald Tribune , Wolfe brought with him this new style, “fusing the stylistic features of fiction and the reportorial obligations of journalism (Kallan, 1992).”

Truman Capote responded to Wolfe’s new style by writing In Cold Blood , which Capote termed a “nonfiction novel,” in 1966 (Plimpton, 1966). The tale of an actual murder that had taken place on a Kansas farm some years earlier, the novel was based on numerous interviews and painstaking research. Capote claimed that he wrote the book because he wanted to exchange his “self-creative world…for the everyday objective world we all inhabit (Plimpton, 1966).” The book was praised for its straightforward, journalistic style. New York Times writer George Plimpton claimed that the book “is remarkable for its objectivity—nowhere, despite his involvement, does the author intrude (Plimpton, 1966).” After In Cold Blood was finished, Capote criticized Wolfe’s style in an interview, commenting that Wolfe “[has] nothing to do with creative journalism,” by claiming that Wolfe did not have the appropriate fiction-writing expertise (Plimpton, 1966). Despite the tension between these two writers, today they are remembered for giving rise to a similar style in varying genres.

The Effects of Literary Journalism

Although literary journalism certainly affected newspaper reporting styles, it had a much greater impact on the magazine industry. Because they were bound by fewer restrictions on length and deadlines, magazines were more likely to publish this new writing style than were newspapers. Indeed, during the 1960s and 1970s, authors simulating the styles of both Wolfe and Capote flooded magazines such as Esquire and The New Yorker with articles.

Literary journalism also significantly influenced objective journalism. Many literary journalists believed that objectivity limited their ability to critique a story or a writer. Some claimed that objectivity in writing is impossible, as all journalists are somehow swayed by their own personal histories. Still others, including Wolfe, argued that objective journalism conveyed a “limited conception of the ‘facts,’” which “often effected an inaccurate, incomplete story that precluded readers from exercising informed judgment (Kallan).”

Advocacy Journalism and Precision Journalism