Become a Bestseller

Follow our 5-step publishing path.

Fundamentals of Fiction & Story

Bring your story to life with a proven plan.

Market Your Book

Learn how to sell more copies.

Edit Your Book

Get professional editing support.

Author Advantage Accelerator Nonfiction

Grow your business, authority, and income.

Author Advantage Accelerator Fiction

Become a full-time fiction author.

Author Accelerator Elite

Take the fast-track to publishing success.

Take the Quiz

Let us pair you with the right fit.

Free Copy of Published.

Book title generator, nonfiction outline template, writing software quiz, book royalties calculator.

Learn how to write your book

Learn how to edit your book

Learn how to self-publish your book

Learn how to sell more books

Learn how to grow your business

Learn about self-help books

Learn about nonfiction writing

Learn about fiction writing

How to Get An ISBN Number

A Beginner’s Guide to Self-Publishing

How Much Do Self-Published Authors Make on Amazon?

Book Template: 9 Free Layouts

How to Write a Book in 12 Steps

The 15 Best Book Writing Software Tools

How To Write A Nonfiction Book: 21 Steps for Beginners

POSTED ON Oct 14, 2020

Written by Scott Allan

The steps on how to write a nonfiction book are easy to follow, but can be difficult to execute if you don't have a clear plan.

Many first time authors experience information overload when it comes to writing a nonfiction book. Where do I start? How do I build authority? What chapters do I need to include? Do I know enough about this topic?

If you're mind is racing with questions about how to get started with your book, then you’ve landed in the right place!

Writing a book can be a grueling, lengthy process. But with a strategic system in place, you could become a nonfiction book author within three to four months.

However, you need an extremely high level of motivation and dedication, as well as a clear, proven system to follow.

In this article, we’ll cover all there is to know about the nonfiction book writing process.

Need A Nonfiction Book Outline?

How to write a nonfiction book

Writing a nonfiction book is one of the most challenging paths you will ever take. But it can also be one of the most rewarding accomplishments of your life.

Before we get started with the steps to write a nonfiction book, let's review some foundational questions that many aspiring authors have.

What is a nonfiction book?

A nonfiction book is based on facts, such as real events, people, and places. It is a broad category, and includes topics such as biography, memoir, business, health, religion, self-help, science, cooking, and more.

A nonfiction book differs from a fiction book in the sense that it is real, not imaginary.

The purpose of nonfiction books is commonly to educate or inform the reader, whereas the purpose of fiction books is typically to entertain.

Perennial nonfiction books are titles such as How to Win Friends and Influence People from Dale Carnegie, A Brief History of Time by Stephen Hawking, and Anne Frank's The Diary of a Young Girl .

What is the author’s purpose in a work of nonfiction?

In a nonfiction book, the author’s main purpose or reason for writing on the topic is to inform or educate readers about a certain topic.

While there are some nonfiction books that also entertain readers, the most common author's purpose in a work of nonfiction is to raise awareness about a certain topic, event, or concept.

How many words are in a nonfiction book?

Because nonfiction is such a broad category, it really depends on the type of nonfiction you are writing, but generally a nonfiction book should be about 40,000 words.

To determine how many words in a novel , narrow down your topic and do some research to see what the average word count is.

Use this Word & Page Count Calculator to calculate how many words you should aim for, based on your genre and audience.

How long does it take to write a nonfiction book?

It can take anywhere from three months to several years to write a nonfiction book, depending on the author's speed, research process, book length, and other variables.

On average, it can take a self-published author typically six months to one year to write their nonfiction book. However, that means the author is setting time aside daily to work on their book, staying focused, and motivated.

Other nonfiction authors, especially those with heavy research an in–depth analysis can take much longer. How long it takes to write a nonfiction book really just depends on several factors.

Benefits of writing a nonfiction book

Making a decision to write a book could change your life. Just think about all the ways you could leverage your expertise!

If you’re interested in how to write a book , it’s important to understand all the things writing the book can do for you, so that you can stay motivated throughout the process.

Some rewarding results that can come after you write a nonfiction book are:

- Exponentially accelerate the growth of your business

- Generate a stream of passive income for years to come

- Build authority in your field of expertise

- Increase exposure in the media

- Become a motivational speaker

- …and so much more (this is just the beginning)!

Imagine for a moment …walking into your local bookstore and seeing your book placed at the front of the store in the new releases section. Or browsing on Amazon KDP , the world’s largest online bookstore, and seeing your nonfiction book listed as a bestseller alongside well-known authors.

It can happen in as little as three months if you are fully committed and ready to start today.

How to Write a Nonfiction Book in 21 Steps

You're clear on the type of nonfiction book you want to write, and you're ready to get started.

Before you start writing, it's time to lay the groundwork and get clear on the entire process. This will help you manage your book writing expectations, and prepare for the nonfiction book writing journey that lies ahead.

With those foundational questions out of the way, let’s move on to 21-step checklist so you can start learning exactly how to write a nonfiction book.

#1— Develop the mindset to learn how to write a nonfiction book

The first step in how to become an author is to develop a rock solid author mindset. Without a writer’s mindset, you are going to struggle to get anywhere with your book. Writing has more to do with your attitude towards the craft than the skill required to get you there.

If writing words down and tying sentences together to craft a story is the skill, your mindset is the foundation that keeps this motivation moving forward.

Identifying yourself as a writer from the start (even if you haven't published yet) will form the mindset needed to continue working on your book .

To succeed, you must toughen up so that nothing gets in your way of writing.

This is also known as imposter syndrome : A psychological pattern where a person doubts their accomplishments and has an ongoing internalized fear of being exposed as a fraud.

Here’s how to prevent imposter syndrome as an aspiring author:

- Define what it means to be an author or writer. Is this someone who wakes up at 5am and writes 1000 words a day?

- Tell yourself you’re a writer. Just do it. It feels strange at first but you will begin to believe your own self-talk.

- Talk about your book idea . That’s right – start telling people you are writing a book. Many writers working on a book will keep it a secret until published. Even then, they might not about it.

- Take action to build author confidence. Imposter syndrome paralyzes you. Focus on increasing your author confidence and getting rid of doubt. This can be done by committing to writing every day. Just 500 words is enough. Build that writing habits early and you’ll be walking and talking like a true author.

#2 – Create a Book Writing Plan

Excuses will kill your chances of becoming a published author. There are no good reasons for not writing a book, only good excuses you convince yourself are real.

You are trying to protect yourself from embarrassment, only to create a new kind of shame: the shame of not finishing the book you have been talking about for years.

Some of the most common excuses that hold writers back are: There is no time to write in my life right now. I can't get past my distractions. I can never be as good as my favorite famous author. My book has to perfect.

Excuses are easy to dish out. But identifying them for what they are (excuses), is the first step towards taking action and changing your limiting mindset.

Excuses, while they may seem valid, are walls of fear. Banish your excuses right now and commit to writing your book.

Here's how to overcome the excuses that prevent you from writing:

- Make the time to write. Set up a thirty-minute time block every day. Commit to writing during this time.

- Turn off your distractions. Get rid of the WiFi for an hour. Close the door. It is just you and the story.

- Be aware of comparisons to other writers. They worked hard to get where they are, and you will get there, too.

- Give yourself permission to write badly. It won’t be perfect, but a book that is half-finished can’t be published.

#3 – Identify your WHY

Start with this question: “Why am I doing this?”

Know your why . This is critical to moving ahead with your book idea. We usually have an intrinsic and extrinsic reason for wanting to learn how to write a nonfiction book.

Intrinsic Why: What is your #1 reason for wanting to write this book? Is it a bucket list goal you must achieve? Is it to help people overcome a root issue in their lives? Do you want to create a movement and generate social impact?

Extrinsic Why: Do you want to create a business from your book? Have passive income coming in for many years later? Become a full-time author and work from home? Grow your network? Build an online presence?

Getting super clear on why you want to write a bestselling book is the momentum to propel you forward and deliver your story. Enlisting the help of a book writing coach (like we offer here at SelfPublishing!) can also help you stay close to your why. This person will be your sounding board, motivation, and voice of reason during the writing process – providing much-needed support from someone who's published multiple books before.

#4 – Research nonfiction book topics

Whether you have a clear idea of what you want to write about or if you are still exploring possible topic ideas, it's important to do a bit of market research.

Researching the current news and case studies related to your potential topic are powerful ways to add credibility to your nonfiction book, and will help you develop your own ideas.

This adds greater depth to your nonfiction book, builds better trust with readers, and delivers content that exceeds customer expectations.

If you need help narrowing down your book idea, try experimenting with some writing prompts based on the genre you're interested in!

Here's how to write a nonfiction book that's well-researched:

- Use case studies. Pull case studies and make reference to the research. If there are not any case studies related to your topic, explore the idea of creating your own case study.

- Read books related to your topic. Mention good books or articles to support your material.

- Research facts from reliable sources. Post proven facts and figures from reliable sources such as scholarly journals, academic papers, white papers, newspapers, and more.

#5 – Select a nonfiction book topic

What are you writing about? It starts with having a deep interest and passion for the area you are focused on.

Common topics to write a nonfiction book on are:

- Business and Money

- Health, dieting and exercise

- Religion and Spirituality

- Home repair

- Innovation and entrepreneurship

You probably already know this so it should be easy. Make a note of the area you are writing your book on. And then…

#6 — Drill down into your book idea

Everyone starts at the same place. It begins with an idea for the book.

What is the core idea for your book? If your nonfiction book topic is on health and dieting, your idea might be a book on “How to lose 7 pounds in your first month.”

Your book is going to be centered around this core idea.

You could have several ideas for the overall book but, to avoid writing a large, general book that nobody will read, make it more specific.

#7 — Schedule writing time

What gets scheduled, gets done. That’s right, you should schedule in your writing time just like any other appointment on your calendar.

Your writing routine will have a large role to play when it comes to writing and finishing your book.

Scheduling time for writing, and sticking to it, will help you knock out your writing goals with ease.

Stephen King sits down to write every morning from eight-thirty. It was his way of programming his brain to get ready for the day’s work. He writes an average of ten pages a day.

W.H. Auden would rise at six a.m. and would work hard from seven to eleven-thirty, when his mind was sharpest.

When do you feel the most productive? If you can, make time for writing at the same time every day to set the tone for your writing productivity.

Commit to a time of day and a length of time during which to write. Set a goal for yourself and try to hit the target every day by sticking with your routine.

#8 — Establish a writing space

You need a place to write, and you must establish that space where you can write everyday, distraction-free for several hours a day.

Your writing environment plays a critical role in your life as an author. If you write in a place that’s full of noise, uncomfortable to be in, or affects your emotional state to the point you don’t want to do anything, you might consider your environment needs some work.

Here is how to create a writing space that inspires you to write:

Display your favorite author photos

Find at least twenty photos of authors you want to emulate. Print these out if you can and place them around your room. An alternative idea is to use the photos as screensavers or a desktop screen. You can change the photo every day if you like. There is nothing like writing and having your favorite author looking back at you as if to say, “Come on, you’ve got this!”

Hang up a yearly calendar

Your nonfiction book will get written faster if you have goals for each day and week. The best way to manage this is by scheduling your time on a calendar. Schedule every hour that you commit to your author business.

As Bob Goff said, “The battle for happiness begins on the pages of our calendars.”

Buy a big wall calendar. Have enough space on each day that you can write down your goals for that day. When you have a goal for that day or week, write it down or use a sticky note.

Create a clutter-free environment

If there is any one factor that will slow you down or kill your motivation, it is a room full of clutter.

If your room looks like a tornado swept through, it can have a serious impact on your emotional state. What you see around you also occupies space in your mind. Unfinished business is unconsciously recorded in your mind and this leads to clutter (both physical and mental).

Although you can’t always be in complete control of your physical space, you can get rid of any clutter you have control over. Go for a simple workplace that makes you feel relaxed.

Choose a writing surface and chair

Consider a standing desk, which is becoming popular for many reasons. Sitting down for long periods of time becomes uncomfortable and unhealthy. You can balance your online time between sitting and standing.

For sitting, you want a chair that is comfortable, but not too comfortable. Invest in a chair that requires you to sit up straight. If there is a comfortable back attached, as with most chairs, you have a tendency to get sleepy. This can trigger other habits as well, such as craving television.

Seek out the place where you can be at your most productive and feel confident and comfortable.

#9 — Choose a nonfiction book writing software

This is one of the most important writing tools you will choose. Your writing software needs to be efficient, easy to use and stress-free. Anything that requires a lot of formatting or a steep learning curve could end up costing you time and patience.

There are literally dozens of choices for book writing software , so it's really just a matter of finding what works best for you.

Here are 3 writing software for new authors to consider:

- Microsoft Word. Before any other writing tools came along, Microsoft Word was the only option available. Today, even though there are many other word processors out there, millions of people continue to use it for their writing needs. And it’s easy to see why. It’s trusted, reliable, and gets the job done well .

- Google Docs . It's a stripped-down version of Word that you can only use online. Some perks are that it comes with the built-in ability to share content, files, and documents with your team. You can easily communicate via comments for collaboration. If you write your book in Google Docs, you can share the link with anyone and they can edit , or make any changes right in the document itself. And all changes are trackable!

- Scrivener . A lot of writers absolutely love this program, with its advanced features and distraction-free writing experience. Scrivener was designed for writers; it’s super easy to lay out scenes, move content around, and outline your story, article, or manuscript. If you’re serious about learning how to write a nonfiction book, then putting in the time to learn this writing tool will definitely be worth it.

There are many forms of writing software that all have advantages to using them, but once you find what works for you, stick with it.

#10 — Create your mind map

A mind map is a brain dump of all your ideas. Using your theme and core idea as a basic starting point, your mind map will help you to visually organize everything into a structure for the book.

I highly recommend using pen and paper for this. You will enjoy the creative flow of this process with a physical version of the map rather than mind mapping software. But, if you prefer using an app to create your mindmap , you can try MindMeister .

Here is how to create your mind map:

- Start with your central idea. Write this idea in the center of the map.

- Add branches connecting key ideas that flow out from the core idea.

- Add keywords that tie these key ideas together.

- Using color coded markers or sticky notes, and identify the chapters within your mindmap.

- Take your chapter headings and…

#11 — How to write a nonfiction book outline

Now that your book topic is decided on, and you have mind mapped your ideas, it’s time to start determining how to outline a nonfiction book.

There are several ways to create a book outline , and it really boils down to author preference and style.

Here's how to write a nonfiction book outline:

- Use this Book Outline Generator for a helpful template to follow for your own outline.

- Map out your book's topics with a mindmap or bubble map, then organize similar concepts together into chapters.

- Answer the 5 Ws: Who, What, When, Where, Why.

- Use book writing software outline tools, like Scrivener's corkboard method.

What is a nonfiction book outline?

A book outline is a roadmap or blueprint for your story. It tells you where you need to go and when in chronological order.

Take the common themes of your chapters and, if applicable, divide your chapters into sections. This is your smooth transition from tangled mind map to organized outline.

Note that not every book needs sections; you might have chapters only. But if your chapters can be grouped into 3-6 different themes within the book, create a section for those common-themed chapters and group them together into a section.

The outline needs to be easy to follow and generally no more than a couple pages long.

The goal here is to take your mind map and consolidate your ideas into a structure that makes logical sense . This will be an incredible roadmap to follow when you are writing the book.

No outline = writing chaos.

There are two types of book outlines I will introduce here:

Option 1: Simple Nonfiction Book Outline

A simple book outline is just like it sounds; keep it basic and brief. Start with the title, then add in your major sections in the order that makes sense for your topic.

Don’t get too hung up on the perfect title at this stage of the process ; you just want to come up with a good-for-now placeholder.

Use our Nonfiction Book Title Generator for ideas.

Option 2: Chapter-by-Chapter Nonfiction Book Outline

Your chapter-by-chapter book outline is a pumped-up version of the simple book outline.

To get started, first create a complete chapter list. With each chapter listed as a heading, you’ll later add material or move chapters around as the draft takes shape.

Create a working title for each chapter. List them in a logical order. After that, you’ll fill in the key points of each chapter.

Create a mind map for each chapter to outline a nonfiction book

Now that you have a list of your chapters, take each one and, similar to what you did with your main mind map for the book, apply this same technique to each chapter.

You want to mind map 3-7 ideas to cover in each chapter. These points will become the subtopics of each chapter that functions to make up chapter structure in your nonfiction book.

It is important to not get hung up on the small details of the chapter content at this stage. Simply make a list of your potential chapters. The outline will most likely change as you write the book. You can tweak the details as you go.

#12 — Determine your point of view

The language can be less formal if you are learning how to write a self-help book or another similar nonfiction book. This is because you are teaching a topic based on your own perspective and not necessarily on something based in scientific research.

Discovering your voice and writing style is as easy as being yourself, but it’s also a tough challenge.

Books that have a more conversational tone to them are just as credible as books with more profound language. You just have to keep your intended audience in mind when deciding what kind of tone you want to have in your book.

The easiest way to do this is to simply write as you would talk, as if you were explaining your topic to someone in front of you – maybe a friend.

Your reader will love this because it will feel like you are sitting with them, having a cup of coffee, hanging out and chatting about your favorite topic.

#13 — Write your first chapter

As soon as you have your nonfiction book outline ready, you want to build momentum right away. The best way to start this is to dive right into your first chapter.

You can start anywhere you like. You don’t have to start writing your nonfiction book in chronological order.

Take a chapter and, if you haven’t yet done so, spend a few minutes to brainstorm the main speaking points. These points are to be your chapter subheadings.

You already have the best software for writing, you’re all set in your writing environment, now you can start writing.

But wait…feeling stuck already?

That’s okay. You might want to start off with some free flow writing. Take a blank page and just start writing down your thoughts. Don’t think about what you are writing or if it makes any sense. This technique is designed to open up your mind to the flow of writing, or stream of consciousness

Write for 10-15 minutes until you are warmed up.

Next, dive into your chapter content.

#14 — Write a nonfiction book first draft

The major step in how to write a nonfiction book is – well, to actually write the first draft!

In this step, you are going to write the first draft of your book. All of it. Notice we did not say you were going to write and edit . No, you are only writing.

Do not edit while you write, and if you can fight temptation, do not read what you’ve written until the first draft is complete.

This seems like a long stretch, to write a 30-40,000-word book without reading it over, but…it’s important to tap into your creative mind and stay there during the writing phase.

It is difficult to access both your writing brain and editing brain at the same time. By sticking with the process of “write first, edit later,” you will finish your first draft faster and feel confident moving into the self-editing phase.

To learn how to write a nonfiction book, use this format:

- Mind map your chapter —10 minutes

- Outline/chapter subheadings—10 minutes

- Research [keep it light]—20 Minutes

- Write content—90 minutes

After you're done with your rough draft (first draft) you'll move on to the second draft/rewrite of your book when you will improve the organization, add more details, and create a polished draft before sending the manuscript to the editor.

#15 — Destroy writer’s block

At some point along the writer’s journey, you are going to get stuck. It is inevitable.

It is what we call the “messy middle” and, regardless you are writing fiction or nonfiction, it happens to everyone. You were feeling super-pumped to get this book written but halfway through, it begins to feel like an insurmountable mountain that you’ll never conquer.

Writer’s block is what happens when you hit a wall and struggle to move forward.

Here is what you can do when you find yourself being pulled down that dark hole.

Talk back to the voices trying to overpower your mind. Your internal critic is empowered when you believe what you are listening to is true.

Bring in the writer who has brought you this far – the one who took the initiative to learn how to write a nonfiction book. Be the writer that embraces fear and laughs at perfectionistic tendencies. Be that person that writes something even if it doesn’t sound good. Let yourself make mistakes and give yourself permission to fail.

Use positive affirmations are therapy for removing internal criticism.

Defeat the self-doubt by not owning it. Your fears exist in your mind. The book you are writing is great, and it will be finished.

Now, go finish it…

#16 — Reach out to nonfiction book editors

Before you start your second rewrite, consider reaching out to an editor and lining someone up to professionally edit your book. Then, when you have completed your self-editing process, you can send your book to the editor as quickly as possible.

Just as producing a manuscript involves a varied skill set—writing, formatting, cover design, etc.— so does editing it.

Do not skimp on quality when it come to editing – set aside money in your budget when determining the costs to publish your book .

Getting a quality edit should be the #1 expenditure for your book. It doesn’t matter if you think you’re a fantastic writer—we all make small mistakes that are difficult to catch, even after reading through the book several times.

You can find good editors on sites such as Upwork or through recommendations from other authors.

#17— Self-edit your first draft

You completed the major step in how to write a nonfiction book: Your rough draft is finished . Now it is time to go through your content page per page, line per line, and clean it up.

This is where is gets messy. This is the self-editing stage and is the most critical part of the book writing process.

You can print out the entire manuscript and read through it in a weekend. Arm yourself with a red pen and several highlighters. You’ll be marking up sentences and writing on the page.

Start with a verbal read through.

Yes, actually read your draft out loud to yourself; you'll be surprised how reading it verbally allows you to spot certain mistakes or areas for improvement.

A verbal read through will show you:

- Any awkward phrasing you’ve used

- What doesn’t make sense

- Typos (the more mistakes you find, the less an editor will accidentally overlook)

Questions to ask as you self-edit your nonfiction book:

- What part of the book is unclear or vague?

- Can the “outsider” understand the point to this section without being told?

- Is my language clear and concrete?

- Can I add more detail or take detail out?

- Can the reader feel my passion for writing and for the topic I am exploring?

- What is the best part of this section and how can I make the other parts as good as the best section?

- Do I have good transitions between chapters?

For printed out material take lots of notes and correct each page as you go. Or break it down by paragraphs and make sure the content flows and transitions well.

Take 2-3 weeks for the self editing stage. The goal isn’t to make it perfect, but to have a presentable manuscript for the editor.

If you let perfection slip in, you could be self-editing and rewriting six months from now. You want to get your best book published, but not have it take three years to get there.

And, when the self edit is finished…

#18 — Create a nonfiction title

The title and subtitle is critical to getting noticed in any physical or online bookstore, such as Amazon.

Related: Nonfiction Book Title Generator

Set aside a few hours to work on crafting your perfect title and subtitle. Keep in mind that needs to engage your potential readers to buy the book.

The title is by far one of the critical elements of the books’ success .

Here are the main points to consider when creating a nonfiction book title:

- Habit Stacking

- Example#1: Break the Cycle of Self-Defeat, Destroy Negative Emotions and Reclaim Your Personal Power

- Example#2: How to Save More Money, Slash Your Spending, and Master Your Spending

Write down as many title ideas as you can. Then, mix and match, moving keywords around until you come up with a title that “sticks.”

Next, test your title by reaching out for feedback – this can be from anyone in your author network. Don’t have an author community to reach out to?

Consider attending some of the best writers conferences to start networking with other writers and authors!

You can also test your title on sites like PickFu .

#19 — Send your nonfiction book to the editor

In a previous step, you hired your editor. Now you are going to send your book to the editor. This process should take about 2-3 weeks. Most editors will do two revisions.

When you receive your first revision, take a few days to go through the edits with track changes turned on. Carefully consider the suggestions your editor is making.

If you don’t agree with some of the suggested edits, delete them! Your editors don’t know your nonfiction book as well as you do.

So, while expert feedback is essential to creating a polished, professional-quality book, have some faith in yourself and your writing.

Now that the editing is done, you are preparing for the final stage…

#20 — Hire a proofreader

Even with the best of editors, there are often minor errors—typos, punctuation—that get missed. This is why you should consider hiring a proofreader—not your editor—to read through the book and catch any last errors.

You don’t want these mistakes to be picked up by readers and then posted as negative reviews.

You can find proofreaders to hire in your local area, or online, such as Scribendi Proofreaders or ProofreadingServices.com.

Some great proofreading apps to use are Grammarly and Hemingway Editor App .

When you are satisfied that the book is 100% error free and stands up to the best standard of quality, it is time to…

#21 — Hire a formatter

Congratulations…you’re almost there! Hiring your book formatter is one of the final stages before publishing.

Nothing can ruin a good book like bad formatting. A well-formatted book enhances your reader's experience and keeps those pages being turned.

Be sure that you have clear chapter headings and that, wherever possible, the chapter is broken up into subheadings.

You can hire good formatters at places like Archangelink , Ebook Launch , and Formatted Books .

Here are the key pages to include in your nonfiction book:

Front Matter Content

- Copyright page

- Free gift page with a link to the opt-in page (optional)

- Table of contents

- Foreword (optional)

Back Matter Content

- Lead magnet [reminder]

- Work with me (optional)

- Acknowledgements (optional)

- Upcoming books [optional]

Now, work together with your formatter and communicate clearly the vision for your book. Be certain your formatter has clear instructions and be closely involved in this process until it is finished.

You know how to write a nonfiction book!

Now that you know the entire process to write your book, it's time to move on to the next phase: publishing and launching your book!

For publishing, you have two options: traditional publishing and self publishing. If you’re completely new to the book writing scene, you may want to check out this article which goes over self publishing .

If you’re deciding between self publishing vs traditional publishing , do some research to choose the right option for you.

Once you get to the marketing phase, be sure to use the Book Profit Calculator to set realistic goals and get your book into the hands of as many readers as possible!

Take some time to celebrate your accomplishing of learning how to write a nonfiction book, then get to work on publishing and launching that book.

Related posts

Non-Fiction

Elite Author Lisa Bray Reawakens the American Dream in Her Debut Business Book

Elite author, david libby asks the hard questions in his new book, elite author, kyle collins shares principles to help you get unstuck in his first book.

What is creative nonfiction? Despite its slightly enigmatic name, no literary genre has grown quite as quickly as creative nonfiction in recent decades. Literary nonfiction is now well-established as a powerful means of storytelling, and bookstores now reserve large amounts of space for nonfiction, when it often used to occupy a single bookshelf.

Like any literary genre, creative nonfiction has a long history; also like other genres, defining contemporary CNF for the modern writer can be nuanced. If you’re interested in writing true-to-life stories but you’re not sure where to begin, let’s start by dissecting the creative nonfiction genre and what it means to write a modern literary essay.

What Creative Nonfiction Is

Creative nonfiction employs the creative writing techniques of literature, such as poetry and fiction, to retell a true story.

How do we define creative nonfiction? What makes it “creative,” as opposed to just “factual writing”? These are great questions to ask when entering the genre, and they require answers which could become literary essays themselves.

In short, creative nonfiction (CNF) is a form of storytelling that employs the creative writing techniques of literature, such as poetry and fiction, to retell a true story. Creative nonfiction writers don’t just share pithy anecdotes, they use craft and technique to situate the reader into their own personal lives. Fictional elements, such as character development and narrative arcs, are employed to create a cohesive story, but so are poetic elements like conceit and juxtaposition.

The CNF genre is wildly experimental, and contemporary nonfiction writers are pushing the bounds of literature by finding new ways to tell their stories. While a CNF writer might retell a personal narrative, they might also focus their gaze on history, politics, or they might use creative writing elements to write an expository essay. There are very few limits to what creative nonfiction can be, which is what makes defining the genre so difficult—but writing it so exciting.

Different Forms of Creative Nonfiction

From the autobiographies of Mark Twain and Benvenuto Cellini, to the more experimental styles of modern writers like Karl Ove Knausgård, creative nonfiction has a long history and takes a wide variety of forms. Common iterations of the creative nonfiction genre include the following:

Also known as biography or autobiography, the memoir form is probably the most recognizable form of creative nonfiction. Memoirs are collections of memories, either surrounding a single narrative thread or multiple interrelated ideas. The memoir is usually published as a book or extended piece of fiction, and many memoirs take years to write and perfect. Memoirs often take on a similar writing style as the personal essay does, though it must be personable and interesting enough to encourage the reader through the entire book.

Personal Essay

Personal essays are stories about personal experiences told using literary techniques.

When someone hears the word “essay,” they instinctively think about those five paragraph book essays everyone wrote in high school. In creative nonfiction, the personal essay is much more vibrant and dynamic. Personal essays are stories about personal experiences, and while some personal essays can be standalone stories about a single event, many essays braid true stories with extended metaphors and other narratives.

Personal essays are often intimate, emotionally charged spaces. Consider the opening two paragraphs from Beth Ann Fennelly’s personal essay “ I Survived the Blizzard of ’79. ”

We didn’t question. Or complain. It wouldn’t have occurred to us, and it wouldn’t have helped. I was eight. Julie was ten.

We didn’t know yet that this blizzard would earn itself a moniker that would be silk-screened on T-shirts. We would own such a shirt, which extended its tenure in our house as a rag for polishing silver.

The word “essay” comes from the French “essayer,” which means “to try” or “attempt.” The personal essay is more than just an autobiographical narrative—it’s an attempt to tell your own history with literary techniques.

Lyric Essay

The lyric essay contains similar subject matter as the personal essay, but is much more experimental in form.

The lyric essay contains similar subject matter as the personal essay, with one key distinction: lyric essays are much more experimental in form. Poetry and creative nonfiction merge in the lyric essay, challenging the conventional prose format of paragraphs and linear sentences.

The lyric essay stands out for its unique writing style and sentence structure. Consider these lines from “ Life Code ” by J. A. Knight:

The dream goes like this: blue room of water. God light from above. Child’s fist, foot, curve, face, the arc of an eye, the symmetry of circles… and then an opening of this body—which surprised her—a movement so clean and assured and then the push towards the light like a frog or a fish.

What we get is language driven by emotion, choosing an internal logic rather than a universally accepted one.

Lyric essays are amazing spaces to break barriers in language. For example, the lyricist might write a few paragraphs about their story, then examine a key emotion in the form of a villanelle or a ghazal . They might decide to write their entire essay in a string of couplets or a series of sonnets, then interrupt those stanzas with moments of insight or analysis. In the lyric essay, language dictates form. The successful lyricist lets the words arrange themselves in whatever format best tells the story, allowing for experimental new forms of storytelling.

Literary Journalism

Much more ambiguously defined is the idea of literary journalism. The idea is simple: report on real life events using literary conventions and styles. But how do you do this effectively, in a way that the audience pays attention and takes the story seriously?

You can best find examples of literary journalism in more “prestigious” news journals, such as The New Yorker , The Atlantic , Salon , and occasionally The New York Times . Think pieces about real world events, as well as expository journalism, might use braiding and extended metaphors to make readers feel more connected to the story. Other forms of nonfiction, such as the academic essay or more technical writing, might also fall under literary journalism, provided those pieces still use the elements of creative nonfiction.

Consider this recently published article from The Atlantic : The Uncanny Tale of Shimmel Zohar by Lawrence Weschler. It employs a style that’s breezy yet personable—including its opening line.

So I first heard about Shimmel Zohar from Gravity Goldberg—yeah, I know, but she insists it’s her real name (explaining that her father was a physicist)—who is the director of public programs and visitor experience at the Contemporary Jewish Museum, in San Francisco.

How to Write Creative Nonfiction: Common Elements and Techniques

What separates a general news update from a well-written piece of literary journalism? What’s the difference between essay writing in high school and the personal essay? When nonfiction writers put out creative work, they are most successful when they utilize the following elements.

Just like fiction, nonfiction relies on effective narration. Telling the story with an effective plot, writing from a certain point of view, and using the narrative to flesh out the story’s big idea are all key craft elements. How you structure your story can have a huge impact on how the reader perceives the work, as well as the insights you draw from the story itself.

Consider the first lines of the story “ To the Miami University Payroll Lady ” by Frenci Nguyen:

You might not remember me, but I’m the dark-haired, Texas-born, Asian-American graduate student who visited the Payroll Office the other day to complete direct deposit and tax forms.

Because the story is written in second person, with the reader experiencing the story as the payroll lady, the story’s narration feels much more personal and important, forcing the reader to evaluate their own personal biases and beliefs.

Observation

Telling the story involves more than just simple plot elements, it also involves situating the reader in the key details. Setting the scene requires attention to all five senses, and interpersonal dialogue is much more effective when the narrator observes changes in vocal pitch, certain facial expressions, and movements in body language. Essentially, let the reader experience the tiny details – we access each other best through minutiae.

The story “ In Transit ” by Erica Plouffe Lazure is a perfect example of storytelling through observation. Every detail of this flash piece is carefully noted to tell a story without direct action, using observations about group behavior to find hope in a crisis. We get observation when the narrator notes the following:

Here at the St. Thomas airport in mid-March, we feel the urgency of the transition, the awareness of how we position our bodies, where we place our luggage, how we consider for the first time the numbers of people whose belongings are placed on the same steel table, the same conveyor belt, the same glowing radioactive scan, whose IDs are touched by the same gloved hand[.]

What’s especially powerful about this story is that it is written in a single sentence, allowing the reader to be just as overwhelmed by observation and context as the narrator is.

We’ve used this word a lot, but what is braiding? Braiding is a technique most often used in creative nonfiction where the writer intertwines multiple narratives, or “threads.” Not all essays use braiding, but the longer a story is, the more it benefits the writer to intertwine their story with an extended metaphor or another idea to draw insight from.

“ The Crush ” by Zsofia McMullin demonstrates braiding wonderfully. Some paragraphs are written in first person, while others are written in second person.

The following example from “The Crush” demonstrates braiding:

Your hair is still wet when you slip into the booth across from me and throw your wallet and glasses and phone on the table, and I marvel at how everything about you is streamlined, compact, organized. I am always overflowing — flesh and wants and a purse stuffed with snacks and toy soldiers and tissues.

The author threads these narratives together by having both people interact in a diner, yet the reader still perceives a distance between the two threads because of the separation of “I” and “you” pronouns. When these threads meet, briefly, we know they will never meet again.

Speaking of insight, creative nonfiction writers must draw novel conclusions from the stories they write. When the narrator pauses in the story to delve into their emotions, explain complex ideas, or draw strength and meaning from tough situations, they’re finding insight in the essay.

Often, creative writers experience insight as they write it, drawing conclusions they hadn’t yet considered as they tell their story, which makes creative nonfiction much more genuine and raw.

The story “ Me Llamo Theresa ” by Theresa Okokun does a fantastic job of finding insight. The story is about the history of our own names and the generations that stand before them, and as the writer explores her disconnect with her own name, she recognizes a similar disconnect in her mother, as well as the need to connect with her name because of her father.

The narrator offers insight when she remarks:

I began to experience a particular type of identity crisis that so many immigrants and children of immigrants go through — where we are called one name at school or at work, but another name at home, and in our hearts.

How to Write Creative Nonfiction: the 5 R’s

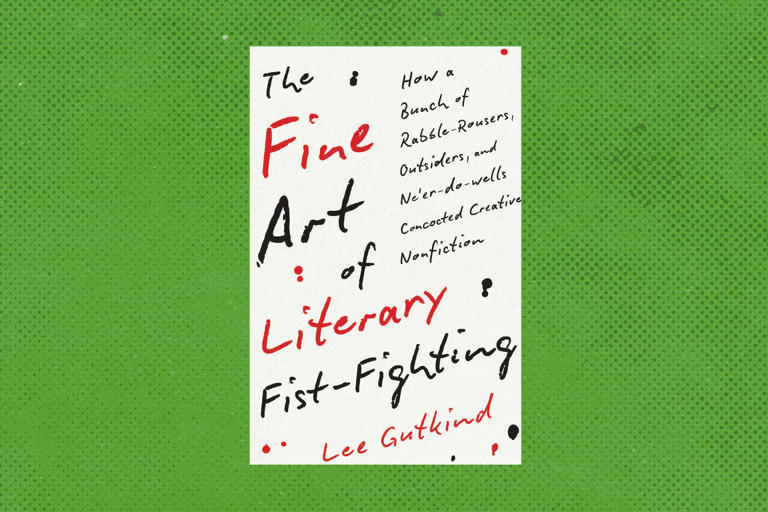

CNF pioneer Lee Gutkind developed a very system called the “5 R’s” of creative nonfiction writing. Together, the 5 R’s form a general framework for any creative writing project. They are:

- Write about r eal life: Creative nonfiction tackles real people, events, and places—things that actually happened or are happening.

- Conduct extensive r esearch: Learn as much as you can about your subject matter, to deepen and enrich your ability to relay the subject matter. (Are you writing about your tenth birthday? What were the newspaper headlines that day?)

- (W) r ite a narrative: Use storytelling elements originally from fiction, such as Freytag’s Pyramid , to structure your CNF piece’s narrative as a story with literary impact rather than just a recounting.

- Include personal r eflection: Share your unique voice and perspective on the narrative you are retelling.

- Learn by r eading: The best way to learn to write creative nonfiction well is to read it being written well. Read as much CNF as you can, and observe closely how the author’s choices impact you as a reader.

You can read more about the 5 R’s in this helpful summary article .

How to Write Creative Nonfiction: Give it a Try!

Whatever form you choose, whatever story you tell, and whatever techniques you write with, the more important aspect of creative nonfiction is this: be honest. That may seem redundant, but often, writers mistakenly create narratives that aren’t true, or they use details and symbols that didn’t exist in the story. Trust us – real life is best read when it’s honest, and readers can tell when details in the story feel fabricated or inflated. Write with honesty, and the right words will follow!

Ready to start writing your creative nonfiction piece? If you need extra guidance or want to write alongside our community, take a look at the upcoming nonfiction classes at Writers.com. Now, go and write the next bestselling memoir!

Sean Glatch

Thank you so much for including these samples from Hippocampus Magazine essays/contributors; it was so wonderful to see these pieces reflected on from the craft perspective! – Donna from Hippocampus

Absolutely, Donna! I’m a longtime fan of Hippocampus and am always astounded by the writing you publish. We’re always happy to showcase stunning work 🙂

[…] Source: https://www.masterclass.com/articles/a-complete-guide-to-writing-creative-nonfiction#5-creative-nonfiction-writing-promptshttps://writers.com/what-is-creative-nonfiction […]

So impressive

Thank you. I’ve been researching a number of figures from the 1800’s and have come across a large number of ‘biographies’ of figures. These include quoted conversations which I knew to be figments of the author and yet some works are lauded as ‘histories’.

excellent guidelines inspiring me to write CNF thank you

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

21 Creative Nonfiction Writing Prompts to Inspire True Stories

by Sue Weems | 0 comments

If you've ever wanted to tell a true story using more literary techniques, then the genre you're exploring is creative nonfiction. Let's define creative nonfiction and then try some creative nonfiction writing prompts today.

What is creative nonfiction?

Creative nonfiction is a literary genre of writing that uses fiction techniques and stylistic choices to express real-life experiences. It depends on story elements especially, so everything you've learned about structure will serve you well in creative nonfiction.

It often includes personal essays, memoirs, biographies, and other related genres such as travel writing or food writing. Creative nonfiction writers strive to make their pieces engaging to readers with narrative techniques typically found in fiction, such as vivid descriptions and dialogue, but in addition to that, they approach their subject matter with a thoughtfulness about the larger meaning of experiences.

It's an extremely flexible form. You can begin by writing out a personal experience and then layering it with narrative or thematic elements. You can infuse your writing with poetic elements to make the writing more lyrical. The possibilities for your writing practice are endless.

Because of that, it's the perfect form for practicing new techniques and experimenting with your storytelling. You could use any nonfiction prompt, but let me give you a few to try today. Remember the one thing you want to do is tell a true story (or as true as you can tell it!).

And if you've always dreamed of writing a memoir, check out our full guide to writing a memoir here .

21 Creative Nonfiction Writing Prompts

1. Tell a personal story about a time you lost something that changed your life.

2. Relate a childhood experience where you felt locked out literally or figuratively.

3. Think about a road trip—maybe not the epic, once-in-a-lifetime trip, but a smaller one that surprised you with something on the way. Write about the vivid details and what defied your expectations.

4. Write about finding unexpected love or friendship.

5. Tell a story about the last time you felt at home.

6. Relate a time when you had to leave something important or precious behind.

7. Tell about a time you had to dig.

8. Write about the first time of drove or traveled alone and it changed you.

9. Tell about a painful or poignant goodbye.

10. Relate a favorite memory about a significant figure in your life.

11. Write the story of the most difficult decision you made in each decade of your life.

12. Tell the story of a birth: of a person, an idea, a business, a relationship.

13. Relate the most life-changing conversation you've had using only dialogue. (or stream-of-consciousness or alternating point of view)

14. Recreate the earliest significant experience you had with school or learning.

15. Write about a tiny object that changed your life.

16. Tell the story of an argument that ended in a surprising or unexpected way.

17. Recreate a scene where you had to defend yourself or someone else.

18. Share a story about trying something new (whether you failed or met success).

19. Write about the moment you knew you had to keep a secret.

20. Tell about a time you interacted, viewed, or read a piece of art and it changed you.

21. Share about a letter, email, or text that disrupted your life and caused you to change course.

Put your writing skills to the test

Now it's your turn. Dig into those childhood memories or visceral experiences that have made you who you are. Tell the story and then look for ways to explore literary technique as you revise.

Choose one of the prompts above and set your timer for fifteen minutes . Write the experience as vividly and direct as you can. Often, the magic of creative nonfiction comes in revision, so don't worry about focusing on too many stylistic choices at first.

When finished, share your creative nonfiction piece in the Pro Practice Workshop here , and encourage a few other writers while you're there.

Sue Weems is a writer, teacher, and traveler with an advanced degree in (mostly fictional) revenge. When she’s not rationalizing her love for parentheses (and dramatic asides), she follows a sailor around the globe with their four children, two dogs, and an impossibly tall stack of books to read. You can read more of her writing tips on her website .

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Submit Comment

Join over 450,000 readers who are saying YES to practice. You’ll also get a free copy of our eBook 14 Prompts :

Popular Resources

Book Writing Tips & Guides Creativity & Inspiration Tips Writing Prompts Grammar & Vocab Resources Best Book Writing Software ProWritingAid Review Writing Teacher Resources Publisher Rocket Review Scrivener Review Gifts for Writers

Books By Our Writers

You've got it! Just us where to send your guide.

Enter your email to get our free 10-step guide to becoming a writer.

You've got it! Just us where to send your book.

Enter your first name and email to get our free book, 14 Prompts.

Want to Get Published?

Enter your email to get our free interactive checklist to writing and publishing a book.

Related Topics

- How to Write a Book

- Writing a Book for the First Time

- How to Write an Autobiography

- How Long Does it Take to Write a Book?

- Do You Underline Book Titles?

- Snowflake Method

- Book Title Generator

- How to Write Nonfiction Book

- How to Write a Children's Book

- How to Write a Memoir

- Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Book

- How to Write a Book Title

- How to Write a Book Introduction

- How to Write a Dedication in a Book

- How to Write a Book Synopsis

- Types of Writers

- How to Become a Writer

- Author Overview

- Document Manager Overview

- Screenplay Writer Overview

- Technical Writer Career Path

- Technical Writer Interview Questions

- Technical Writer Salary

- Google Technical Writer Interview Questions

- How to Become a Technical Writer

- UX Writer Career Path

- Google UX Writer

- UX Writer vs Copywriter

- UX Writer Resume Examples

- UX Writer Interview Questions

- UX Writer Skills

- How to Become a UX Writer

- UX Writer Salary

- Google UX Writer Overview

- Google UX Writer Interview Questions

- Technical Writing Certifications

- Grant Writing Certifications

- UX Writing Certifications

- Proposal Writing Certifications

- Content Design Certifications

- Knowledge Management Certifications

- Medical Writing Certifications

- Grant Writing Classes

- Business Writing Courses

- Technical Writing Courses

- Content Design Overview

- Documentation Overview

- User Documentation

- Process Documentation

- Technical Documentation

- Software Documentation

- Knowledge Base Documentation

- Product Documentation

- Process Documentation Overview

- Process Documentation Templates

- Product Documentation Overview

- Software Documentation Overview

- Technical Documentation Overview

- User Documentation Overview

- Knowledge Management Overview

- Knowledge Base Overview

- Publishing on Amazon

- Amazon Authoring Page

- Self-Publishing on Amazon

- How to Publish

- How to Publish Your Own Book

- Document Management Software Overview

- Engineering Document Management Software

- Healthcare Document Management Software

- Financial Services Document Management Software

- Technical Documentation Software

- Knowledge Management Tools

- Knowledge Management Software

- HR Document Management Software

- Enterprise Document Management Software

- Knowledge Base Software

- Process Documentation Software

- Documentation Software

- Internal Knowledge Base Software

- Grammarly Premium Free Trial

- Grammarly for Word

- Scrivener Templates

- Scrivener Review

- How to Use Scrivener

- Ulysses vs Scrivener

- Character Development Templates

- Screenplay Format Templates

- Book Writing Templates

- API Writing Overview

- Business Writing Examples

- Business Writing Skills

- Types of Business Writing

- Dialogue Writing Overview

- Grant Writing Overview

- Medical Writing Overview

- How to Write a Novel

- How to Write a Thriller Novel

- How to Write a Fantasy Novel

- How to Start a Novel

- How Many Chapters in a Novel?

- Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Novel

- Novel Ideas

- How to Plan a Novel

- How to Outline a Novel

- How to Write a Romance Novel

- Novel Structure

- How to Write a Mystery Novel

- Novel vs Book

- Round Character

- Flat Character

- How to Create a Character Profile

- Nanowrimo Overview

- How to Write 50,000 Words for Nanowrimo

- Camp Nanowrimo

- Nanowrimo YWP

- Nanowrimo Mistakes to Avoid

- Proposal Writing Overview

- Screenplay Overview

- How to Write a Screenplay

- Screenplay vs Script

- How to Structure a Screenplay

- How to Write a Screenplay Outline

- How to Format a Screenplay

- How to Write a Fight Scene

- How to Write Action Scenes

- How to Write a Monologue

- Short Story Writing Overview

- Technical Writing Overview

- UX Writing Overview

- Reddit Writing Prompts

- Romance Writing Prompts

- Flash Fiction Story Prompts

- Dialogue and Screenplay Writing Prompts

- Poetry Writing Prompts

- Tumblr Writing Prompts

- Creative Writing Prompts for Kids

- Creative Writing Prompts for Adults

- Fantasy Writing Prompts

- Horror Writing Prompts

- Book Writing Software

- Novel Writing Software

- Screenwriting Software

- ProWriting Aid

- Writing Tools

- Literature and Latte

- Hemingway App

- Final Draft

- Writing Apps

- Grammarly Premium

- Wattpad Inbox

- Microsoft OneNote

- Google Keep App

- Technical Writing Services

- Business Writing Services

- Content Writing Services

- Grant Writing Services

- SOP Writing Services

- Script Writing Services

- Proposal Writing Services

- Hire a Blog Writer

- Hire a Freelance Writer

- Hire a Proposal Writer

- Hire a Memoir Writer

- Hire a Speech Writer

- Hire a Business Plan Writer

- Hire a Script Writer

- Hire a Legal Writer

- Hire a Grant Writer

- Hire a Technical Writer

- Hire a Book Writer

- Hire a Ghost Writer

Home » Blog » How to Write a Nonfiction Book (8 Key Stages)

How to Write a Nonfiction Book (8 Key Stages)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

This article explores how to write a nonfiction book, a genre encompassing various subjects from history and biography to self-help and science.

Nonfiction writing, distinct from its fictional counterpart, demands a rigorous approach to factual accuracy, comprehensive research, and clarity in presentation. We aim to provide a pragmatic guide for aspiring authors, delineating the steps involved in a nonfiction work’s conceptualization, research, writing, editing, and publishing.

This guide serves both novice and experienced writers, offering insights into each phase of the book-writing process. By adhering to a methodical approach, writers can transform their knowledge and ideas into compelling, well-structured nonfiction books.

How to Write a Nonfiction Book

Here are the main 8 stages of writing a nonfiction book. Let’s start.

Choosing a Topic

Selecting the right topic is the cornerstone of writing a successful nonfiction book. This step is crucial because it influences your writing journey and impacts the appeal to your target audience.

Whether you are writing a nonfiction book for the first time or the tenth time, it never hurts to use a good template. Squibler provides writing-ready templates, including for nonfiction topics.

Identifying Your Passion

Begin by introspecting about subjects you are interested in or even a personal story that you have. The ideal topic should intrigue you and sustain your interest over the long process of writing a book. It could be a field you have expertise in, a hobby you are passionate about, or a subject you have always wanted to explore in depth.

Use Portent’s Content Idea Generator to generate ideas based on any subject you have in mind.

Assessing Market Demand

Once you have a list of potential topics, the next step is to analyze the market demand. This involves researching current trends, finding a popular nonfiction book title in your chosen genre, and identifying gaps in the available literature. Tools like Google Trends and Amazon’s Best Sellers lists can provide insights into what readers are currently interested in.

Conducting Initial Research

Before finalizing your topic, conduct preliminary research to ensure there’s enough information available to cover your subject comprehensively. This research will also help you understand the different perspectives and debates surrounding your topic. It’s important to ensure that the topic is not too broad, making it difficult to cover thoroughly or too narrow, limiting the book’s appeal to a wider audience.

Finalizing Your Topic

After considering your passion, market demand, and the availability of research material, narrow down your choices to one topic. This topic should be interesting and marketable and offer a unique angle or perspective that distinguishes your book from existing works in the field.

Use the Hedgehog Concept to find a great topic for your nonfiction book. Read all about this concept here .

In summary, choosing a topic for your nonfiction book requires balancing personal interest, market viability, and availability of sufficient content. This careful consideration will set the foundation for a compelling and successful nonfiction book.

Research and Gathering Information

Conducting research is a fundamental aspect of writing nonfiction. It involves gathering, organizing, and verifying information to ensure reliability.

Detailed Methods for Conducting Effective Research

Here are helpful methods for conducting research:

- Identify Reliable Sources: Identify authoritative sources such as academic journals, books by respected authors, government publications, and reputable news organizations. Online databases and libraries can be invaluable for this.

- Diverse Research Techniques: Use primary sources (like interviews, surveys, and firsthand observations) and secondary sources (such as books, articles, and documentaries). This mix provides depth and perspective to your research.

- Note-Taking and Documentation: As you gather information, take detailed notes. Record bibliographic information (author, title, publication date, etc.) for each source to make referencing easier later. Tools like Zotero or EndNote can help manage citations.

Tips for Organizing and Compiling Research Materials

Here are some further tips for organizing your nonfiction book writing process.

- Categorize Information: Organize your research into categories related to different aspects of your topic. This will make it easier to find information when you start writing.

- Use Digital Tools: Utilize digital tools such as spreadsheets, document folders, or specialized research software to keep your information organized.

- Maintain a Research Log: Keep a log of your research activities, including where you found information and keywords or topics searched. This log will be invaluable if you need to revisit a source.

By using Squibler for your writing, you can use many tools to organize your writing to stick to a steady schedule.

Ethical Considerations and Fact-Checking in Nonfiction Writing

Here are ethical considerations to be aware of when learning how to write a nonfiction book:

- Fact-Checking: Rigorously check the facts you plan to include in your book. Verify dates, names, quotes, and statistics from multiple sources.

- Avoid Plagiarism: Always give proper credit to the sources of your information. Paraphrase where necessary and use quotations for direct citations.

- Ethical Reporting: Be aware of the ethical implications of your writing, especially when dealing with sensitive topics. Strive for fairness and accuracy in your representation of different viewpoints.

Effective research for a nonfiction book requires a systematic and ethical approach to gathering, organizing, and verifying information. You can ensure that your nonfiction work is credible and compelling by using various research methods, maintaining organized notes, and adhering to ethical standards.

Planning and Outlining the Book

Planning and outlining are critical steps in writing a nonfiction book. This phase involves structuring your ideas and research findings into a coherent and logical framework to guide your writing process.

Importance of Creating a Detailed Outline

Read about the importance of having a detailed outline.

- Blueprint for Your Book: An outline serves as a roadmap for your book, helping you organize your thoughts and research systematically. It ensures that your narrative flows and that you cover all key points.

- Efficiency and Focus: A well-structured outline helps you write. It keeps you focused on your main points and prevents you from veering off-topic.

- Identifying Gaps: During the outlining process, you may identify areas where further research or elaboration is needed, allowing you to address these gaps before you begin writing.

Here is an example of how to outline your book based on the structure:

Methods for Outlining Nonfiction Books

Here, you’ll learn about key methods for creating an outline:

- Chronological Structure: A chronological approach might be most effective for topics that unfold over time, such as historical events or biographies.

- Thematic Structure: If your book covers different aspects of a topic, organizing your outline by themes or subjects can help present information in a more integrated way.

- Problem-Solution Framework: For topics like business or self-help, structuring your outline to present problems and their solutions can engage readers.

Tips for Structuring Your Book

Read some further tips for creating a book structure:

- Start with a Broad Overview: Begin your outline with a broad overview of your topic, then break it into more specific chapters or sections.

- Balance Your Chapters: Try to balance the length and depth of each chapter to keep readers engaged and ensure a smooth flow.

- Include Introduction and Conclusion: Plan for an introductory section to set the context of your book and a conclusion to wrap up and reinforce your key messages.

- Consider Readers’ Needs: Keep your intended audience in mind while outlining. Structure your content to address the readers’ interests, background knowledge, and expectations.

Writing the First Draft

Writing the first draft of a nonfiction book is where you transform your research and outline into a manuscript. This stage is about getting your ideas down on paper and shaping the raw material of your research into a readable and engaging narrative.

Starting the Writing Process

Here, you will read the main steps in writing nonfiction and healthy writing habits for creative nonfiction.

- Overcoming the Blank Page: The first step is to overcome the intimidation of the blank page. Begin by writing about the parts you are most comfortable with or most excited about. This builds momentum.

- Refer to Your Outline: Consult your outline to stay on track. However, be flexible enough to deviate if a section needs more elaboration or a different direction.

- Set Realistic Goals: Establish daily or weekly word count goals. Consistency is key to making steady progress.

- Write Consistent Conversations: A nonfiction writer creates a conversation with their readers. Create a consistent information flow by using one of the four types.

Here are four types of conversations that will give you an idea of what will work best for your audience.

Maintaining a Consistent Writing Routine

Learn how to maintain a writing routine in each writing phase:

- Create a Writing Schedule: Set aside dedicated time for writing each day or week. Consistency is crucial, whether an hour every morning or a full day over the weekend.

- Create a Writing Environment: Find or create a space where you can write without distractions. The right environment can significantly boost your productivity and focus.

Dealing with Writer’s Block

Read about the basics of overcoming writer’s block.

- Take Breaks: Step away from your work if you hit a block. Sometimes, taking a short walk or engaging in a different activity can refresh your mind.

- Write Freely: Don’t be too concerned with perfection in the first draft. Allow yourself to write freely without worrying too much about grammar or style at this stage.

- Talk It Out: Discussing your ideas with someone can provide new perspectives and help overcome blocks.

Staying Motivated

Learn how to stay motivated:

- Track Your Progress: Tracking your progress can be a great motivational tool. Seeing how far you’ve come can encourage you to keep going.

- Seek Feedback: Sharing sections of your draft with trusted friends or other nonfiction authors provides encouragement and constructive feedback.

- Remember Your Purpose: Remind yourself why you started this project. Revisiting your initial inspiration can reignite your enthusiasm.

Writing the first draft of your nonfiction book involves starting with confidence, maintaining a disciplined routine, tackling challenges like writer’s block, and staying motivated throughout the process. This stage is less about perfection and more about bringing your ideas to life in a coherent structure. Remember, the first draft is just the beginning, and refinement comes later in the editing stages.

Editing and Revising

Editing and revising are about refining your first draft and enhancing its clarity, coherence, and overall quality. It involves scrutinizing and improving your manuscript at different levels, from overall structure to individual sentences.

The Importance of a Self-Editing Process

Read about self-editing.

- First Layer of Refinement: Self-editing is your first opportunity to review and improve your work. This process includes reorganizing sections, ensuring each chapter flows logically into the next, and checking for consistency in tone and style.

- Focus on Clarity and Conciseness: Look for areas where arguments can be made clearer, descriptions more vivid, and redundancies eliminated. It’s crucial to be concise and to the point in nonfiction writing.

Seeking Feedback

Here, you will read about basic tips for seeking feedback.

- Beta Readers and Writing Groups: Share your manuscript with trusted individuals representing your target audience. Beta readers or members of writing groups can provide invaluable feedback from a reader’s perspective.

- Constructive Criticism: Be open to constructive criticism. It can provide insights into areas you might have overlooked or not considered fully.

Hiring a Professional Editor

Here’s what to consider if you think you need a professional editor.

- When and Why It’s Necessary: A professional editor can bring a level of polish and expertise that’s hard to achieve on your own. They can help with structural issues, language clarity, and fact-checking. Consider hiring an editor, especially if you plan to self-publish.

- Types of Editing Services: Understand the different editing services available, including developmental editing, copyediting, and proofreading. Each serves a different purpose and is relevant at different stages of the revision process.

Revising Your Manuscript

Here, you’ll read about revising the manuscript.

- Iterative Process: Revision is an iterative process. It may require several rounds to get your manuscript to the desired quality.

- Attention to Detail: Check grammar, punctuation, and factual accuracy. Nonfiction books, in particular, need to be factually correct and well-cited.

- Incorporating Feedback: Integrate the feedback from your beta readers and editor judiciously. Balance maintaining your voice and message with addressing valid concerns and suggestions.

Editing and revising are where your manuscript transforms into its final form. This stage requires patience, attention to detail, and, often, external input. By embracing the editing and revising process, you can significantly enhance the quality of your nonfiction book, making it more engaging, credible, and polished.

Publishing Options

After writing, editing, and revising your nonfiction book, the next critical step in the how-to-write-a-nonfiction-book process is to decide how to publish it. Today, a nonfiction author has various options, each with its own set of advantages and challenges. Understanding these can help you choose the best path for your nonfiction book.

Traditional Publishing

Here, you can read about traditional publishing routes.

- Working with Literary Agents: Traditional publishing typically involves securing a literary agent to represent your book to publishers. An agent’s knowledge of the market and industry contacts can be invaluable.

- The Submission Process: This involves preparing a proposal and sample chapters to send to publishers, often through your agent. The process can be lengthy and competitive.

- Advantages: Traditional publishers offer editorial, design, and marketing support. They can also provide broader distribution channels.

- Considerations: It can be challenging to get accepted by a traditional publisher. They usually control the final product and a significant share of the profits.

Self-Publishing

Here, you can read about the possibility of self-published books.

- Complete Creative Control: Self-publishing gives you total control over every aspect of your book, from the content to the cover design and pricing.

- The Self-Publishing Process: This includes tasks like formatting the book, obtaining an ISBN, and choosing distribution channels (e.g., Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing).

- Marketing and Promotion: Self-publishing means you are responsible for marketing and promoting your book. This can be a significant task but also offers the opportunity for higher royalties per book sold.

- Accessibility: Platforms like Amazon, Smashwords, and Draft2Digital have made self-publishing more accessible, offering tools and services to assist authors.

Hybrid Publishing

The third option is hybrid publishing. Read more about it:

- Combination of Traditional and Self-Publishing: Hybrid publishing models combine elements of both traditional and self-publishing, offering more support than self-publishing alone but with more flexibility and control for the author.

- Costs and Services: These publishers often charge for their services, but they also offer professional editing, design, and marketing services.

Choosing the Right Option

Finally, here are tips for deciding exactly what the route to take:

- Consider Your Goals: Consider what you want to achieve with your book. Are you looking to reach a wide audience, maintain creative control, or see your book in bookstores?

- Understand Your Audience: Knowing where your target audience buys books can guide your choice. Some genres do exceptionally well in self-publishing, while others fare better with traditional publishers.

- Assess Your Resources: Consider your budget, available time for marketing, and your comfort level with the various aspects of the publishing process.

The choice between traditional, self-publishing, and hybrid options depends on your goals, resources, and the level of control and support you desire. Each path has its unique set of benefits and challenges, and understanding these can help you make an informed decision about the best way to bring your nonfiction book to your readers.

Marketing and Promotion

The success of a nonfiction book depends on effective marketing and promotion strategies. Here are tactics that you can use: