Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Specific Learning Disability

Our nation’s special education law, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) defines specific learning disability as…

(10) Specific learning disability —(i) General . Specific learning disability means a disorder in one or more of the basic psychological processes involved in understanding or in using language, spoken or written, that may manifest itself in the imperfect ability to listen, think, speak, read, write, spell, or to do mathematical calculations, including conditions such as perceptual disabilities, brain injury, minimal brain dysfunction, dyslexia, and developmental aphasia.

(ii) Disorders not included. Specific learning disability does not include learning problems that are primarily the result of visual, hearing, or motor disabilities, of intellectual disability, of emotional disturbance, or of environmental, cultural, or economic disadvantage. [34 CFR §300.8(c)(10)]

From: Center for Parent Information and Resources, (2017), Categories of Disability Under IDEA. Newark, NJ, Author. Retrieved 3.28.19 from https://www.parentcenterhub.org/categories/ (public domain)

Table of Contents

- Go to Chapter on Dyslexia

- Go to Chapter on Dyscalculia

- Go to Chapter on Dysgraphia

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria

- General Overview of Specific Learning Disability/Case Study

- Evaluation Procedures for LD

Tips for Teachers

- Technology for Students with Learning Disabilities- Video

Dyslexia, sometimes called reading disorder , is the most common learning disability; of all students with specific learning disabilities, 70%–80% have deficits in reading. The term “developmental dyslexia” is often used as a catch-all term, but researchers assert that dyslexia is just one of several types of reading disabilities. A reading disability can affect any part of the reading process, including word recognition, word decoding, reading speed, prosody (oral reading with expression), and reading comprehension.

Dyscalculia

Dyscalculia is a form of math-related disability that involves difficulties with learning math-related concepts (such as quantity, place value, and time), memorizing math-related facts, organizing numbers, and understanding how problems are organized on the page. People with dyscalculia are often referred to as having poor “number sense.”

The term “dysgraphia” is often used as an overarching term for all disorders of written expression. Individuals with dysgraphia typically show multiple writing-related deficiencies, such as grammatical and punctuation errors within sentences, poor paragraph organization, multiple spelling errors, and excessively poor penmanship.

The following text is an adapted from: Boundless.com (n.d.) Textbooks/ Boundless Psychology/Neurodevelopmental Disorders/Specific Learning Disorder. CC-BY-SA 4.0

Specific learning disorder includes difficulties in general academic skills, specifically in the areas of reading, mathematics, or written expression.

Specific learning disorder is a classification of disorders in which a person has difficulty learning in a typical manner within one of several domains. Often referred to as learning disabilities, learning disorders are characterized by inadequate development of specific academic, language, and speech skills. Types of learning disorders include difficulties in reading (dyslexia), mathematics (dyscalculia), and writing (dysgraphia)

The diagnosis of specific learning disorder was added to the DSM-5 in 2013. The DSM does not require that a single domain of difficulty (such as reading, mathematics, or written expression) be identified—instead, it is a single diagnosis that describes a collection of potential difficulties with general academic skills, simply including detailed specifiers for the areas of reading, mathematics, and writing. Academic performance must be below average in at least one of these fields, and the symptoms may also interfere with daily life or work. In addition, the learning difficulties cannot be attributed to other sensory, motor, developmental, or neurological disorders.

The causes of learning disabilities are not well understood. However, some potential causes or contributing factors are:

- Heredity. Learning disabilities often run in the family—children with learning disabilities are likely to have parents or other relatives with similar difficulties.

- Problems during pregnancy and birth. Learning disabilities can result from anomalies in the developing brain, illness or injury, fetal exposure to alcohol or drugs, low birth weight, oxygen deprivation, or premature or prolonged labor.

- Accidents after birth. Learning disabilities can also be caused by head injuries, malnutrition, or toxic exposure (such as to heavy metals or pesticides).

(Boundless,n.d)

General Overview of SLD/ Case Study

The following text is an excerpt from: Educational Psychology. Chapter 5 Authored by : Kelvin Seifert and Rosemary Sutton. . License : CC BY: Attribution From https://open.umn.edu/opentextbooks/textbooks/153

LDs are by far the most common form of special educational need, accounting for half of all students with special needs in the United States and anywhere from 5 to 20 per cent of all students, depending on how the numbers are estimated (United States Department of Education, 2005; Ysseldyke & Bielinski, 2002). Students with LDs are so common, in fact, that most teachers regularly encounter at least one per class in any given school year, regardless of the grade level they teach.

Defining learning disabilities clearly

With so many students defined as having learning disabilities, it is not surprising that the term itself becomes ambiguous in the truest sense of “having many meanings”. Specific features of LDs vary considerably. Any of the following students, for example, qualify as having a learning disability, assuming that they have no other disease, condition, or circumstance to account for their behavior:

- Albert, an eighth-grader, has trouble solving word problems that he reads, but can solve them easily if he hears them orally.

- Bill, also in eighth grade, has the reverse problem: he can solve word problems only when he can read them, not when he hears them.

- Carole, a fifth-grader, constantly makes errors when she reads textual material aloud, either leaving out words, adding words, or substituting her own words for the printed text.

- Emily, in seventh grade, has terrible handwriting; her letters vary in size and wobble all over the page, much like a first- or second-grader.

- Denny reads very slowly, even though he is in fourth grade. His comprehension suffers as a result, because he sometimes forgets what he read at the beginning of a sentence by the time he reaches the end.

- Garnet’s spelling would have to be called “inventive”, even though he has practiced conventionally correct spelling more than other students. Garnet is in sixth grade.

- Harmin, a ninth-grader has particular trouble decoding individual words and letters if they are unfamiliar; he reads conceal as “concol” and alternate as “alfoonite”.

- Irma, a tenth-grader, adds multiple-digit numbers as if they were single-digit numbers stuck together: 42 + 59 equals 911 rather than 101, though 23 + 54 correctly equals 77.

With so many expressions of LDs, it is not surprising that educators sometimes disagree about their nature and about the kind of help students need as a consequence. Such controversy may be inevitable because LDs by definition are learning problems with no obvious origin. There is good news, however, from this state of affairs, in that it opens the way to try a variety of solutions for helping students with learning disabilities.

Assisting students with learning disabilities

There are various ways to assist students with learning disabilities, depending not only on the nature of the disability, of course, but also on the concepts or theory of learning guiding you. Take Irma, the girl mentioned above who adds two-digit numbers as if they were one digit numbers. Stated more formally, Irma adds two-digit numbers without carrying digits forward from the ones column to the tens column, or from the tens to the hundreds column. Exhibit 4 shows the effect that her strategy has on one of her homework papers. What is going on here and how could a teacher help Irma?

Directions: Add the following numbers.

Three out of the six problems are done correctly, even though Irma seems to use an incorrect strategy systematically on all six problems.

Exhibit 4: Irma’s math homework about two-digit addition

Behaviorism: reinforcement for wrong strategies

One possible approach comes from the behaviorist theory. Irma may persist with the single-digit strategy because it has been reinforced a lot in the past. Maybe she was rewarded so much for adding single-digit numbers ( 3+5, 7+8 etc.) correctly that she generalized this skill to two-digit problems—in fact over generalized it. This explanation is plausible because she would still get many two-digit problems right, as you can confirm by looking at it. In behaviorist terms, her incorrect strategy would still be reinforced, but now only on a “partial schedule of reinforcement”. Partial reinforcement schedules are especially slow to extinguish, so Irma persists seemingly indefinitely with treating two-digit problems as if they were single-digit problems.

From the point of view of behaviorism, changing Irma’s behavior is tricky since the desired behavior (borrowing correctly) rarely happens and therefore cannot be reinforced very often. It might therefore help for the teacher to reward behaviors that compete directly with Irma’s inappropriate strategy. The teacher might reduce credit for simply finding the correct answer, for example, and increase credit for a student showing her work—including the work of carrying digits forward correctly. Or the teacher might make a point of discussing Irma’s math work with Irma frequently, so as to create more occasions when she can praise Irma for working problems correctly.

Metacognition and responding reflectively

Part of Irma’s problem may be that she is thoughtless about doing her math: the minute she sees numbers on a worksheet, she stuffs them into the first arithmetic procedure that comes to mind. Her learning style, that is, seems too impulsive and not reflective enough. Her style also suggests a failure of metacognition , which is her self-monitoring of her own thinking and its effectiveness. As a solution, the teacher could encourage Irma to think out loud when she completes two-digit problems—literally get her to “talk her way through” each problem. If participating in these conversations was sometimes impractical, the teacher might also arrange for a skilled classmate to take her place some of the time. Cooperation between Irma and the classmate might help the classmate as well, or even improve overall social relationships in the classroom.

Constructivism, mentoring, and the zone of proximal development

Perhaps Irma has in fact learned how to carry digits forward, but not learned the procedure well enough to use it reliably on her own; so she constantly falls back on the earlier, better-learned strategy of single-digit addition. In that case her problem can be seen in the constructivist terms. In essence, Irma has lacked appropriate mentoring from someone more expert than herself, someone who can create a “ zone of proximal development” in which she can display and consolidate her skills more successfully. She still needs mentoring or “assisted coaching” more than independent practice. The teacher can arrange some of this in much the way she encourages to be more reflective, either by working with Irma herself or by arranging for a classmate or even a parent volunteer to do so. In this case, however, whoever serves as mentor should not only listen, but also actively offer Irma help. The help has to be just enough to insure that Irma completes two-digit problems correctly —neither more nor less. Too much help may prevent Irma from taking responsibility for learning the new strategy, but too little may cause her to take the responsibility prematurely.

(Seifert & Sutton, 2009)

The following section is an excerpt from: Center for Parent Information and Resources, (2015), Learning Disabilities (LD). Newark, NJ, Author. Retrieved 3.28.19 from https://www.parentcenterhub.org/ld/ (public domain)

Evaluation Procedures for LD

Now for the confusing part! The ways in which children are identified as having a learning disability have changed over the years. Until recently, the most common approach was to use a “severe discrepancy” formula. This referred to the gap, or discrepancy, between the child’s intelligence or aptitude and his or her actual performance. However, in the 2004 reauthorization of IDEA, how LD is determined has been expanded. IDEA now requires that states adopt criteria that:

- must not require the use of a severe discrepancy between intellectual ability and achievement in determining whether a child has a specific learning disability;

- must permit local educational agencies (LEAs) to use a process based on the child’s response to scientific, research-based intervention; and

- may permit the use of other alternative research-based procedures for determining whether a child has a specific learning disability.

Basically, what this means is that, instead of using a severe discrepancy approach to determining LD, school systems may provide the student with a research-based intervention and keep close track of the student’s performance. Analyzing the student’s response to that intervention (RTI) may then be considered by school districts in the process of identifying that a child has a learning disability.

There are also other aspects required when evaluating children for LD. These include observing the student in his or her learning environment (including the regular education setting) to document academic performance and behavior in the areas of difficulty.

This entire fact sheet could be devoted to what IDEA requires when children are evaluated for a learning disability. Instead, let us refer you to a training module on the subject. It’s quite detailed, but if you would like to know those details, read through Module 11 of the Building the Legacy curriculum on IDEA 2004. Identification of Specific Learning Disabilities is available online at the CPIR,

Learning disabilities (LD) vary from person to person. One person with LD may not have the same kind of learning problems as another person with LD. Sara, in our example above, has trouble with reading and writing. Another person with LD may have problems with understanding math. Still another person may have trouble in both of these areas, as well as with understanding what people are saying.

Researchers think that learning disabilities are caused by differences in how a person’s brain works and how it processes information. Children with learning disabilities are not “dumb” or “lazy.” In fact, they usually have average or above average intelligence. Their brains just process information differently.

There is no “cure” for learning disabilities. They are lifelong. However, children with LD can be high achievers and can be taught ways to get around the learning disability. With the right help, children with LD can and do learn successfully.

Learn as much as you can about the different types of LD. The resources and organizations listed below can help you identify specific techniques and strategies to support the student educationally.

Seize the opportunity to make an enormous difference in this student’s life! Find out and emphasize what the student’s strengths and interests are. Give the student positive feedback and lots of opportunities for practice.

Provide instruction and accommodations to address the student’s special needs. Examples:

- breaking tasks into smaller steps, and giving directions verbally and in writing;

- giving the student more time to finish schoolwork or take tests;

- letting the student with reading problems use instructional materials that are accessible to those with print disabilities;

- letting the student with listening difficulties borrow notes from a classmate or use a tape recorder; and

- letting the student with writing difficulties use a computer with specialized software that spell checks, grammar checks, or recognizes speech.

Learn about the different testing modifications that can really help a student with LD show what he or she has learned.

Teach organizational skills, study skills, and learning strategies. These help all students but are particularly helpful to those with LD.

Work with the student’s parents to create an IEP tailored to meet the student’s needs.

Establish a positive working relationship with the student’s parents. Through regular communication, exchange information about the student’s progress at school.

(CPIR, 2015, LD)

Technology for Students with Learning Disabilities

[TheDOITCenter], (2015, Aug. 20). Working Together: Computers and People with Learning Disabilities. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/-uaEdaD5wJE Creative Commons Attribution license (reuse allowed) (11:24 minutes)

Photo Reference

Boy with notebook- Image by paperelements from Pixabay

Center for Parent Information and Resources, (2015), Learning Disabilities (LD). Newark, NJ, Author. Retrieved 3.28.19 from https://www.parentcenterhub.org/ld/ (public domain)

Educational Psychology. Chapter 5 Authored by : Kelvin Seifert and Rosemary Sutton. . License : CC BY: Attribution From https://open.umn.edu/opentextbooks/textbooks/153

[TheDOITCenter], (2015, Aug. 20). Working Together: Computers and People with Learning Disabilities. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/-uaEdaD5wJE Creative Commons Attribution license (reuse allowed)

Wikipedia, (n.d.) Dyscalculia, From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dyscalculia#:~:text=on%20the%20topic.-,Etymology,calculation%22%20and%20%22calculus%22.

updated 5.26.22

Understanding and Supporting Learners with Disabilities Copyright © 2019 by Paula Lombardi is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

LEARNING DISABILITY : A CASE STUDY

The present investigation was carried out on a girl name Harshita who has been identified with learning disability. She is presently studying at ‘Udaan’ a school for the special children in Shimla. The girl was brought to this special school from the normal school where she was studying earlier when the teachers and parents found it difficult to teach the child with other normal children. The learning disability the child faces is in executive functioning i.e. she forgets what she has memorized. When I met her I was taken away by her sweet and innocent ways. She is attentive and responsible but the only problem is that she forgets within minutes of having learnt something. Key words : learning disability, executive functioning, remedial teaching

Related Papers

The Indian Journal of Pediatrics

Sunil Karande , Madhuri Kulkarni

International Journal of Scientific Research in Computer Science Applications and Management Studies

Monika Thapliyal

This paper reviews the research work on 'learning disability' in India. It studies the social and educational challenges for learning disabled, and details research in India, concerning the aspects of diagnosis, assessment, and measures for improvement. The paper critically examines the development in their teaching-learning process, over the years. It highlights the role of special educator in their education and explores the impact of technology and specific teaching-aids in the education of learners with learning disability. The later part of the paper, throws light on the government policies for learning disabled and attempts to interpolate their proposed effect in their learning. It concludes with possible solutions, learner progress, based on the recommendations from detailed analysis of the available literature.

International Journal of Contemporary Pediatrics

Shipra Singh

Background: Specific learning disability (SLD) is an important cause of academic underachievement among children, which often goes unrecognized, due to lack of awareness and resources in the community. Not much identifiable data is available such children, more so in Indian context. The objectives of the study were to study the demographic profile, risk factors, co-morbidities and referral patterns in children with specific learning disability.Methods: The study has a descriptive design. Children diagnosed with SLD over a 5 years’ period were included, total being 2015. The data was collected using a semi-structured proforma, (based on the aspects covered during child’s comprehensive assessment at the time of visit), which included socio-demographic aspects, perinatal and childhood details, scholastic and referral details, and comorbid psychiatric disorders.Results: Majority of the children were from English medium schools, in 8-12 years’ age group, with a considerable delay in seek...

Journal of Postgraduate Medicine

Sunil Karande

Fernando Raimundo Macamo

IJIP Journal

The cardinal object of the present study was to investigate the learning disability among 10 th students. The present study consisted sample of 60 students subjects (30 male students and 30 female students studying in 10th class), selected through random sampling technique from Balasore District (Odisha). Data was collected with the help of learning disability scale developed by Farzan, Asharaf and Najma Najma (university of Panjab) in 2014. For data analysis and hypothesis testing Mean, SD, and t test was applied. Results revealed that there is significant difference between learning disability of Boys and Girls students. That means boys showing more learning disability than girls. And there is no significant difference between learning disability of rural and urban students. A learning disability is a neurological disorder. In simple terms, a learning disability results from a difference in the way a person's brain is "wired." Children with learning disabilities are smarter than their peers. But they may have difficulty in reading, writing, spelling, and reasoning, recalling and/or organizing information if left to figure things out by them or if taught in conventional ways. A learning disability can't be cured or fixed; it is a lifelong issue. With the right support and intervention, children with learning disabilities can succeed in school and go on to successful, often distinguished careers later in life. Parents can help children with learning disabilities achieve such success by encouraging their strengths, knowing their weaknesses, understanding the educational system, working with professionals and learning about strategies for dealing with specific difficulties. Facts about learning disabilities Fifteen percent of the U.S. population, or one in seven Americans, has some type of learning disability, according to the National Institutes of Health.

Indian Pediatrics

Rukhshana Sholapurwala

samriti sharma

Baig M U N T A J E E B Ali

The present article deals with the important factors related to learning disability such as the academic characteristics of learning disability, how learning disability can be identified in an early stage and remedial measures for learning disability. It tries to give an insight into various aspects of learning disability in children that will be of help in designing the tools and administering them properly.

Iconic Research and Engineering Journals

IRE Journals

This article explains how learning disability affect on one's ability to know or use spoken affects on one's ability to know or use spoken or communication, do mathematical calculations, coordinate movements or direct attention learning disabilities are ignored, unnoticed and unanswered such children's needs are not met in regular classes. They needed special attention in classrooms. Learning disability is a big challenge for student in learning environment. The teacher's role is very important for identifying the learning disability. Some common causes and symptoms are there for children with learning disability. The classroom and teacher leads to main important role in identification and to overcome their disabilities.

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

We Need to Keep (but Revise) the Specific Learning Disability Construct in IDEA

Nancy Mather, Ph.D.

Monica McHale-Small, Ph.D.

David H. Allsopp, Ph.D.

Sarah VanIngen Lauer, Ph.D.

We have all been in this field for a very long time. Rumor has it (from attending the LDA 2024 Conference) that some professionals are once again suggesting that specific learning disabilities (SLD) is no longer a useful construct and perhaps should be replaced in the re-authorization of IDEA 2004 with classification based solely on low achievement (at or below the 5 th percentile on standardized achievement measures) or even eliminated altogether. This recommendation for using low achievement as the criterion for special education is not new, but it is inconsistent with the concept of SLD (See Mather & Gregg, 2006), The purpose of this commentary is to examine why we still need to identify students with SLD, explain the main characteristics of SLD, and make a few suggestions for the revision of the SLD categories in the re-authorization of IDEA 2004.

The Concept of Unexpectedness

SLD was first categorized as a disability in the United States in 1975 with the passage of PL 94-142, but the existence of this disability was not created by this law. We have known about the existence of SLD for over a century. Case studies of these individuals can be found in the late 1800s. For example, Pringle Morgan (1896) discussed Percy, a bright 14-year-old boy, who: “… seems to have no power of preserving and storing up the visual impression produced by words – hence the words, though seen, have no significance for him. His visual memory for words is defective or absent which is equivalent to saying that he is what Kussmaul has termed ‘word blind.’ I may add that the boy is bright and of average intelligence in conversation…The schoolmaster who has taught him for some years says that he would be the smartest lad in the school if the instruction were entirely oral” (p. 1378).

Similarly, Hinshelwood (1902, 1917), a Scottish ophthalmic surgeon, described children with congenital word blindness as having average or above-average intelligence in other respects. He noted that many parents reported that their children apart from their reading difficulties were the most intelligent members of their families. Monroe (1932) also described numerous cases of children with reading disorders, some who were highly intelligent. She observed that “The children of superior mental capacity who fail to learn to read are, of course, spectacular examples of specific reading difficulty since they have such obvious abilities in other fields” (p. 23).

These early examples illustrate the concept of unexpectedness. Today, this concept is still explained in reference to the person’s intelligence or oral language, that is, the person has the intelligence or verbal abilities to be a much better reader. For example, in discussing the specific learning disability of dyslexia, Shaywitz and Shaywitz (2020) describe it as an unexpected difficulty in reading in an individual who has the intelligence to be a much better reader.

The Concept of Specificity

This unevenness among abilities illustrates the concept of specificity, another central theme of SLD. The word “specific” conveys the idea that not all abilities are low or impaired. Specificity indicates that the weaknesses in reading, writing, or math, do not affect other domains. Kavale and Forness (2000) explained that the addition of the adjective specific indicates that the poor academic performance experienced by students with SLD can be attributed to a limited number of underlying deficits (p. 245), which we might also understand as neurocognitive differences.

Travis (1935) described children who fail to learn to read or spell despite having adequate intelligence, as well as those who have a striking disparity between their ability in one subject and that in another. He explained that some children cannot read although they can comprehend the material when it is read to them, whereas other children present the opposite condition. He proposed that children who do not achieve as well as would be expected in a certain direction may be regarded as having a “special” disability. He explained that the clearest expression of this disability is consistently low scores in a given subject with average or superior scores on tests in other subjects.

For example, in the case of evidence for a reading disability, a student may have scores at the ninth-grade level in arithmetic, but at the third-grade level in reading. This unevenness in abilities would provide evidence of a striking reading disability; another child might indicate just as striking a disability in mathematics. Several decades later, Gallagher (1966) described these intraindividual differences as “developmental imbalances” meaning significant differences between the individual’s strengths and weaknesses. Since the last revision of IDEA, research uncovering some of the “underlying deficits” commonly seen in children struggling with reading, writing, or math has continued to amass.

Thoughts for the Revision of IDEA 2004

Given more recent advances in the neurocognitive underpinnings of learning, it merits discussing how this knowledge as well as other advances in evaluation and assessment can help us to revisit how to conceptualize the construct of SLD in the IDEA. Under the current IDEA, SLD includes the following eight categories: oral expression, listening comprehension, basic reading skills, reading fluency skills, reading comprehension, written expression, mathematics calculation, and mathematics problem solving. We would like to suggest some revisions to these eight categories.

Inclusion of oral language. More recent research related to oral language has led to an increased understanding of disorders specifically related to language (i.e., Developmental Language Disorders). Developmental Language Disorders (DLD) affect both oral expression and listening comprehension, two areas included in the IDEA definition of SLD. By continuing to include oral language (oral expression and listening comprehension) in the SLD definition, it creates confusion due to the overlap between the diagnostic categories of SLD and developmental language disorders (DLD).

Clearly weaknesses in oral language affect academic learning but these difficulties may often be better categorized as DLD, rather than SLD. High comorbidity exists between DLD and SLD but they are distinct disorders that require different interventions. In many cases, students who have SLD, but no other disorders, have a discrepancy between their average or above average oral language and one or more areas of academic performance.

Therefore, SLD seems to be best reserved for specific problems in the academic domains of reading (dyslexia), writing (dysgraphia), and mathematics (dyscalculia). When a student is struggling with reading comprehension, math applications and problem solving, or written expression, it can be difficult to determine when such difficulties are the result of a more global language disorder or rooted in weakness in cognitive processes such as working memory. Furthermore, SLD in these academic domains can also impact other areas, such as poor reading contributing to math problem solving, as well as the impact that SLD can have on a student’s social and emotional learning.

The category of written expression. As with categories of reading and mathematics, the area of written expression needs to include both written expression and basic writing skills. Students who have dysgraphia who struggle with handwriting and spelling often do not qualify for SLD as their ability to express their ideas in writing is not impaired. Also, a student with dyslexia, who has had systematic reading intervention, may have average scores in reading, but still demonstrate a significant weakness in spelling and require intervention.

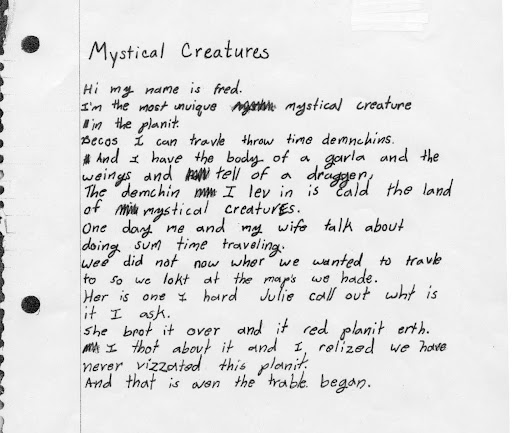

As an example, consider the following writing sample from Aaron in Figure 1, a bright sixth-grade student, who has average reading scores. Aaron did not qualify for special education services, as the multidisciplinary committee concluded his difficulties were with basic writing skills, not with written expression. This writing sample demonstrates Aaron’s SLD in written expression (dysgraphia) and his need for systematic instruction in basic writing skills.

The category of mathematics. Additionally, we need to reconsider what is emphasized with respect to mathematics and the construct and evaluation of SLD. Currently, mathematics calculation (fact retrieval and computation) and mathematics problem solving (operationalized as word problems) are included in the definition. Although important, these areas are an incomplete representation of the mathematics curriculum and what is understood about the learning of mathematics and students with SLD in mathematics.

For a broader perspective, these two areas in the definition could be replaced with four categories: Number Sense, Mathematics Processes/Practices (used for problem solving), Mathematical Fluency (accuracy, efficiency, and strategy), and Mathematical Visual-Spatial Abilities. These four areas represent a more comprehensive treatment of mathematics that includes not only “calculation” and “problem-solving” but also the additional areas that get at the “what” of math (content), the “how” of math (doing math), and the “why” of math (conceptual understanding). Students who struggle in these areas can illustrate “symptoms” of a SLD in mathematics that can then be verified by an evaluation of relevant cognitive processing areas such as verbal working memory and visual-spatial processing that relate to math disabilities (Soares. et al., 2017), setting the stage for a robust way to determine patterns of strengths and weaknesses that can inform intervention.

Alternatively, the definitions and explanations of mathematics calculation and mathematics problem solving could be revised to better capture the breadth of mathematical deficits that are characteristic of SLD.

Three Procedures for Identifying SLD

The final concern about IDEA 2004 requirements are the three procedures that may be used to diagnose SLD: (1) the identification of a significant discrepancy between intellectual ability and achievement; (2) the use of other alternative research-based procedures, most often operationalized as a pattern of strengths and weaknesses (PSW) approach; and (3) a student’s response to evidence-based intervention, often referred to as response to intervention (RTI).

While an important process in determining which students are in need of a comprehensive evaluation, RTI should not be included as a way to diagnose SLD. There are many reasons why a student would not respond to a specific intervention and only one of the reasons is they have SLD. Whereas the first two procedures include the evaluation of targeted assessment data, both quantitative and qualitative, the RTI process often does not. RTI’s definition of SLD is not in alignment with the definitions of SLD outlined in major diagnostic manuals and seems best described as a school-wide framework for identifying and providing support to all struggling learners, regardless of the existence of a disability (Mather & Schneider, 2023).

Although problems exist with both, the other two criteria make sense. The ability-achievement discrepancy is an attempt to capture the unexpectedness of the adequate intelligence compared to the low achievement and may have utility in the evaluation of twice-exceptional students (Pennington et al., 2019). The PSW approach is an attempt to operationalize the concept of specificity and demonstrates that not all of the individual’s abilities are low, only the ones that are related to the disorder. While there are critics for all of these approaches with credible concerns, a PSW approach is most consistent with our past and current understanding of SLD.

Conclusions

Two basic concepts that are common among most definitions and have endured over time regarding SLD are: a specific pattern of strengths and weaknesses and unexpected learning failure (Kavale & Spaulding, 2008). Although formal assessment can provide useful quantitative and qualitative information, clearly the diagnosis of SLD involves more than just interpreting a student’s performance on standardized tests. For an accurate diagnosis, the evaluation team must also consider any previous diagnoses or comorbid disorders, such as DLD or ADHD; family history (e.g., any close relatives with SLD); school history and prior interventions; teacher, parent, and self-reports; social and emotional concerns; and current classroom performance. Because of the overlap among reading, writing, and mathematics disabilities, evaluators will want to consider comorbidity when one or the other is determined to exist.

Students with SLD exist and the category needs to be maintained as it is different than other types of disabilities. In discussing the dedication of their book, Stanger and Donahue (1937) said: “There are many poor readers among very bright children, who, because they are poor readers, are considered less keen than their classmates. This book should really be dedicated to the thousands of bright children thus misjudged” (p. 43). We cannot overlook the educational needs of these children.

Carpenter, T. P., Fennema, E., Peterson, P. L., Chiang, C. P., & Loef, M. (1989). Using knowledge of children’s mathematics thinking in classroom teaching: An experimental study. American Educational Research Journal , 26 (4), 499-531.

Dennis, M. S., Calhoon, M. B., Olson, C. L., & Williams, C. (2014). Using computation curriculum-based measurement probes for error pattern analysis. Intervention in School and Clinic , 49 (5), 281-289.

Gallagher, J. J. (1966). Children with developmental imbalances: A psychoeducational definition. In W. M. Cruickshank (Ed.), The teacher of brain-injured children (pp. 23-43). Syracuse University Press.

Hinshelwood, J. (1902b). Four cases of word-blindness. The Lancet , 159 (4093), 358–363.

Hinshelwood, J. (1917). Congenital word-blindness . Lewis.

Hwang, J., & Riccomini, P. J. (2021). A descriptive analysis of the error patterns observed in the fraction-computation solution pathways of students with and without learning disabilities. Assessment for Effective Intervention , 46 (2), 132-142.

Kavale, K. A., & Forness, S. R. (2000). What definitions of learning disability say and don’t say. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 33 , 239-256.

Kavale, K. A., & Spaulding, L. S. (2008). Is response to intervention good policy for specific learning disability? Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 23, 169-179.

Mather, N., & Gregg, N. (2006). Specific learning disabilities: Clarifying, not eliminating, a construct. Professional Psychology, 37 , 99-106.

Mather, N., & Schneider, D. (2023). The use of cognitive tests in the assessment of dyslexia. Journal of Intelligence, 11 , 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence11050079

Moyer, P. S., & Milewicz, E. (2002). Learning to question: Categories of questioning used by preservice teachers during diagnostic mathematics interviews. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education , 5 , 293-315.

Monroe, M. (1932). Children who cannot read. University of Chicago Press.

Morgan, W. Pringle. (1896). Word blindness. British Medical Journal, 2 , 1378. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.2.1871.1378

Pennington, B. F., McGrath, L. M., & Peterson, R. L. (2019). Diagnosing learning disorders: From science to practice (3rd ed.). Guilford.

Shaywitz, S., & Shaywitz, J. (2020). Overcoming dyslexia (2nd ed.). Alfred A. Knopf.

Soares, N., Evans, T., & Patel, D. R. (2018). Specific learning disability in mathematics: a comprehensive review. Translational Pediatrics , 7 (1), 48.

Stanger, M. A., & Donohue, E. K. (1937). Prediction and prevention of reading difficulties. Oxford University Press.Travis, L. E. (1935). Intellectual factors. In G. M. Whipple (Ed.), The thirty-fourth yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education: Educational diagnosis (pp. 37-47). Public School Publishing Company.

Travis, L. E. (1935). Intellectual factors. In G. M. Whipple (Ed.), The thirty-fourth yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education: Educational diagnosis (pp. 37-47). Public School Publishing Company.

Nancy Mather is a Professor Emerita at the University of Arizona. She studied with the late Dr. Samuel Kirk, who is often referred to as the father of the field of learning disabilities. She is a co-author of two recent publications, Essentials of Dyslexia: Assessment and Intervention , 2 nd ed.(Mather & Wendling, 2024) and the Tests of Dyslexia (Mather, McCallum, Bell, & Wendling, 2024).

Monica McHale-Small , Ph.D. is Director of Education for the Learning Disabilities Association of America. She retired after twenty-seven years of service in public education in Pennsylvania having served as a school psychologist and in various administrative roles including district superintendent. Monica has been an Adjunct Associate Professor of School Psychology at Temple University.

David Allsopp is a professor in the Department of Curriculum, Instruction, and Learning’s Exceptional Student Education program. David engages in Teacher Education research related to how teacher educators can most effectively prepare teachers to address the needs of students with learning disabilities and other struggling students especially in the area of mathematics.

Sarah van Ingen-Lauer is an Assistant Professor of Mathematics Education at the University of South Florida where she co-directs the innovative and nationally recognized Urban Teacher Residency Partnership Program. Dr. van Ingen Lauer collaborates with Dr. Allsopp to enhance teacher effectiveness with students with learning disabilities in mathematics.

OPINION article

This article is part of the research topic.

Smart Sustainable Development: Exploring Innovative Solutions and Sustainable Practices for a Resilient Future

Quality education for all: a case study of success for a neurodivergent learner Provisionally Accepted

- 1 Otago Polytechnic, New Zealand

The final, formatted version of the article will be published soon.

This article showcases an innovative approach to the acquisition of undergraduate degrees known as the Independent Learning Pathway (ILP) at Capable NZ, a School of the Otago Polytechnic. The ILP offers a unique and learner-centric alternative to traditional degree programmes, particularly beneficial for mature learners whose prior learning experiences and diverse skill sets may not be fully recognised by conventional models. Through a personalised learning journey, the ILP empowers participants to demonstrate their competencies and obtain qualifications. The ILP is a unique educational approach which aligns with the broader global initiative encapsulated in Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Goal 4: "Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all." Traditional education models often struggle to cater to the diverse needs and learning styles of adult learners. The ILP addresses this gap by offering a flexible and personalised learning experience, fostering inclusivity, and ensuring that valuable prior knowledge and skills are recognised through a deeply reflective learning process. This, in turn, empowers individuals to pursue further education and contribute more effectively to the workforce and to their communities.A significant portion of the global population exhibits neurodiverse traits, encompassing conditions like dyslexia, ADHD, and autism. These individuals may face challenges in traditional learning environments due to their unique cognitive strengths and weaknesses. The ILP, with its emphasis on personalised learning strategies and a supportive learning environment, creates a space where neurodiverse learners can thrive.This article presents a case study exploring the collaborative journey of Rachel, a neurodivergent learner, through the ILP programme, alongside her facilitator Glenys, who is a highly experienced facilitator of the ILP approach. By showcasing Rachel's successful experience, this study aims to demonstrate the effectiveness of both the ILP as an innovative and inclusive approach to degree acquisition, and the nature and scope of effective facilitation of learning, in supporting neurodiverse learners and achieving the goals of inclusive education outlined in SDG 4. The 17 Sustainable Development Goals, adopted by all United Nations member states in 2015, collectively seek to address pressing social, economic, and environmental challenges to create a more sustainable and equitable world by 2030.SDG 4, which focuses on Quality Education, includes targets relating to equitable access to vocational and higher education. This goal recognises the transformative power of education in promoting sustainable development, fostering inclusive and resilient societies, and empowering individuals.The various targets under SDG 4 include eliminating gender disparities in education and ensuring equal access to all levels of education and vocational training for vulnerable populations. Meeting these targets involves addressing various barriers that hinder individuals from pursuing further education, such as traditional delivery models, time constraints, financial barriers, lack of learner confidence, and the challenges related to recognising and validating learning from experience.If the SDG 4 goal and targets are to be met, vocational education delivery will need to adopt innovative and more inclusive approaches, including diversifying learning modalities, greater learner-centricity, redefining qualifications based on outcomes, and recognising and valuing all forms of valid learning.The Independent Learning Pathway is one of these innovative and more inclusive approaches. In New Zealand, the ILP is a groundbreaking initiative introduced by Capable NZ, a school within Otago Polytechnic. The ILP is an alternative approach to degree acquisition, enabling the highly experienced, mature learner to obtain mainstream qualifications through a unique and highly learner-centric learning journey that affirms and values learning from their diverse experiences, as well as their cultural knowledge.The ILP is made possible because the NZ Qualifications Authority (NZQA) defines qualifications through graduate profiles, which emphasise graduate outcomes, thereby allowing for a wide range of approaches to the acquisition of the knowledge and skills that enable the graduate outcomes to be met. NZQA also mandates the recognition of relevant prior learning, thereby freeing learners from unnecessary learning activities if graduate outcomes have already been met. The ILP approach is for highly experienced learners, generally in work, who are often poorly served by traditional taught delivery models. These learners already have considerable degree-relevant knowledge and skills, often enriched with cultural knowledge and understanding, which usually does not count as part of a taught degree. These learners typically do not enrol in traditional degree programmes because they may not have the time or resources to study within a typical delivery framework. Also, they have often experienced a lack of success in prior formal education contexts, thereby lacking confidence and being unable to see themselves as legitimate participants in a tertiary credentialled world.The ILP approach provides equity of access for this group, offering a process that validates work based, cultural and community experiential learning. The approach guides the learner through a range of tasks to make explicit the learning from their experience and to acquire new learning as necessary to enhance it. As they reflect on their experience, learners analyse and articulate their graduate level competencies and are supported to present these by using degree level academic skills.As a strategy for equitable access, the ILP:• Is a structured yet personalised learning journey, managed by the learner with facilitator support.• Recognises and credits all relevant prior learning.• Facilitates the acquisition of new skills and knowledge, with the learner at the forefront, determining when and where learning takes place.• Focuses on workplace-based learning, embracing learning at, though, from, and for work.• Equips learners for lifelong learning through critical reflection, a powerful tool for continuous education. In the dynamic landscape of contemporary teaching and learning, facilitators often encounter learners with neurodiverse traits or unidentified learning challenges. Understanding the importance of inclusivity, facilitators must embrace neurodiversity to create supportive learning environments. This article outlines strategies for serving neurodiverse learners to foster their academic and personal growth. Furthermore, the strategies for ensuring the success of neurodiverse learners are also applicable to adult learners at large.Case Study: A Neurodiverse Learner's Journey through the ILP This case study draws on the joint experiences of the authors and aims to provide guidance for both learners and facilitators on effective facilitation strategies tailored to the success of neurodiverse individuals. Rachel, a neurodivergent learner with ADHD, Irlen Syndrome, and dyslexia, works as a facilitator at Otago Polytechnic's School of Business. Alongside Glenys, a highly experienced facilitator and assessor in Capable NZ, Rachel navigated her transformative learning journey through the Independent Learning Pathway for a management degree, followed by a Master of Professional Practice. Her journey attests to the power of Ako -a teaching and learning relationship that empowers both the learner and the facilitator, exemplifying the potential for neurodiverse individuals to thrive through an innovative educational framework. Rachel, as co-author of this article, has provided her full approval and consent for the disclosure of her identity and the publication of this case study.Rachel's transformative journey through the Independent Learning Pathway (ILP) underscores the profound impact of personalised learning and supportive facilitation. Throughout her educational pursuits, Rachel experienced a significant personal and professional progression, centred on the cultivation of her own professional identity. This journey was characterised by the development of a strong sense of self and unwavering self-confidence, facilitated by an environment that celebrated her unique strengths and perspectives, empowering her to embrace her neurodiversity as an asset rather than a limitation.A pivotal aspect of Rachel's growth was her engagement in rigorous research and continuous learning.This commitment not only enhanced her academic performance but also equipped her with the skills necessary for success in her role as an educator. Rachel's journey also saw her confidently stepping into new roles and opportunities, from organising symposia to presenting at conferences and writing articles, establishing herself as a respected voice in the field of neurodiversity. Crucial to Rachel's success was the personalised approach provided by the ILP, fostering a strong relationship with Glenys built on trust and open communication. This environment enabled Rachel to comfortably share her thoughts and ideas, supported by Glenys' expertise in identifying and addressing areas of struggle, ultimately demonstrating the potential for neurodiverse individuals to thrive within educational frameworks which prioritise individualised support and empowerment.By sharing their experiences, Glenys and Rachel hope to inspire other educators and facilitate a collective effort towards creating inclusive and supportive learning environments that enable not just neurodiverse learners, but all learners, to flourish academically and personally.Neurodiversity encompasses various learning disabilities (e.g., dyspraxia, dyslexia, ADHD, dyscalculia, autism spectrum disorder, Tourette Syndrome) (Clouder et al., 2020;van Gorp, 2022). It asserts that neurological differences are inherent in human diversity, akin to race or gender, emphasising the unique cognitive strengths of neurodivergent individuals (van Gorp, 2022).van Gorp (2022) stresses the importance of tailored support in tertiary institutions for neurodiverse learners to succeed, thereby contributing diverse perspectives and strengths to society. Some neurodiverse learners may not disclose their condition(s) for various reasons, such as unawareness, past negative experiences, or discomfort. Scholars argue against pressuring non-voluntary class participation despite potential advantages (Kirby, 2021;Hayes, 2021;Jansen et al., 2017).Rachel, who successfully completed her studies by way of the ILP programme, attests to the tangible growth in her knowledge, skills, and career confidence. Beyond establishing a professional identity, the ILP cultivates essential 21st-century competencies vital for adaptability and lifelong learning. Its transformative impact is particularly significant for neurodiverse learners, often marginalised in traditional educational settings. Unlike conventional methods, the ILP prioritises a personalised, oneon-one approach, focusing on understanding each learner's individual needs and preferences. The facilitator's expertise is paramount, as they adeptly observe and inquire to tailor the learning experience accordingly. By enhancing the agency of neurodiverse learners and acknowledging their unique learning styles, the ILP empowers them to excel in their educational journey.Central to supporting neurodiverse learners is amplifying their voices and experiences, exploring effective workarounds, and breaking negative habits to develop sustainable learning strategies.Effective self-advocacy becomes crucial, and the ILP process equips learners with the tools to assertively communicate their needs. Through seeking support and accessing resources, neurodivergent learners enhance their self-advocacy skills, establishing a supportive network that accommodates their cognitive strengths and challenges effectively. In the context of Sustainable Development Goal 4, the ILP journey becomes a catalyst for the development or enhancement of professional identity and 21st-century competencies. These include heightened identity awareness, values exploration, and self-awareness of competencies and transferable skills. These attributes not only fortify a robust sense of self but also instil career confidence and resilience in the face of uncertainty. As learners reflect on their educational journey, it becomes evident that they have honed the ability to adapt to diverse circumstances, recognising the tangible benefits of conscious adaptability. This holistic approach to education not only fulfils an individual's aspirations but also aligns with the broader objective of fostering inclusivity and sustainable personal and professional development.Rachel and Glenys discovered valuable strategies for fostering the success of neurodiverse learners. Supportive Environment -establish inclusivity by setting clear expectations, providing structure, and fostering individualised learning opportunities. Create a safe space for learners to share their thoughts, concerns, and challenges without judgment. Rather than rushing to make a judgment on whether someone is neurodiverse, it is more effective to observe and ask questions with the belief that understanding will lead to determining how best to support the learner. At the appropriate time, the facilitator and learner may engage in a conversation about the potential benefits of obtaining a diagnosis to further support the learner's journey.Additionally, positive relationships and a sense of relatedness are vital in the learning context. When learners feel connected to facilitators and peers, they experience a sense of belonging, positively impacting motivation, well-being, and persistence in academic pursuits. Facilitators must take responsibility for their professional development to effectively support a neurodivergent learner to be successful.Multi-Modal Strategies -cater to diverse learning styles with a range of strategies engaging different senses, such as visuals, hands-on activities, and technology tools, promoting effective communication, for example, a facilitator might use videos (visual), experiments (hands-on activities), and interactive apps (technology tools) to explain a concept.Clear Instructions -ensure clarity in instructions by identifying potential challenges in processing complex information. Utilise clear, concise, and multi-format instructions, incorporating visual aids, written guidelines, and verbal explanations.Learner Agency -empower neurodiverse learners by fostering agency through goal setting, decisionmaking, and self-assessment. This approach promotes autonomy, resilience, and aligns seamlessly with the ethos of lifelong learning. For instance, a learner with ADHD can be encouraged to set personalised goals for task focus, make decisions regarding break times, and evaluate their own progress. The ILP's flexible online format facilitates this autonomy, allowing learners to take ownership of their learning journey. However, this autonomy is always in collaboration with their facilitator, ensuring that timelines are adhered to for successful completion of learning tasks and assessments. This personalised approach caters to the diverse needs of neurodiverse learners, providing a supportive environment for their academic and personal growth.Feedback and Reinforcement -provide tailored feedback and reinforcement to support learning, ensuring it is specific, constructive, and timely. This approach aids neurodiverse learners in tracking their progress, pinpointing areas for growth, and fostering confidence. While applicable across educational contexts, the importance of tailored feedback and reinforcement is particularly pronounced within the ILP pathway. For example, a facilitator might provide immediate and precise feedback to a learner with autism, ensuring personalised attention that aids in their comprehension and skill development. This individualised support exemplifies the benefits of the ILP for neurodiverse individuals, enhancing their learning experience and facilitating their academic and personal growth.Flexibility and Adaptability -flexibility and adaptability are crucial within the ILP, allowing for the recognition of individual strengths, challenges, and learning paces. Facilitators adeptly modify strategies and offer additional support or accommodations as necessary. For example, in the case of a learner with dyslexia facing difficulties with traditional reading, a facilitator might provide audiobooks, utilize visuals, and extend time, showcasing the ILP's ability to tailor teaching methods to meet unique needs effectively. Glenys and Rachel discuss the importance of effective facilitation through personalised adaptation of teaching methods within the ILP. For instance, when Rachel encountered difficulties with text-based learning materials, Glenys seamlessly incorporated visual aids alongside text, enhancing comprehension and empowerment. This personalised approach, established in trust and rapport, allowed Rachel to openly address her learning challenges. The transformative impact of tailored learning approaches was evident as Rachel discovered her preferred visual and auditory learning styles, benefiting not only her own journey but also her son's. As an emerging educator, Rachel utilised visual aids to introduce learning styles to her students, promoting self-awareness and autonomy. In Ker's Effective Facilitation Model (2017), emphasis is placed on building relationships, fostering trust, and promoting effective communication. Facilitators, equipped with diverse skills in the teaching and learning environment, play a pivotal role in adopting a learner-first approach. This involves empowering learners to take responsibility for their learning and cultivating a sense of agency. Ker stresses intrinsic motivation, emphasising the importance of genuine interest in the subject matter for increased engagement, deeper learning, and improved academic outcomes.However, Ker acknowledges that intrinsic motivation alone is insufficient. Support and encouragement are crucial to sustain learners' efforts. Autonomy-supportive environments, offering choices and self-direction, play a pivotal role in maintaining motivation. Providing feedback that recognises progress and accomplishments contributes to a sense of competence, encouraging learners to strive for higher performance.van Gorp (2022) adds valuable insights into the importance of effective facilitation, emphasising the dynamic nature of learning. Facilitators, according to van Gorp (2022), demonstrate adaptability to evolving learner needs, creating a flexible and responsive environment. This approach involves recognising and appreciating the diverse backgrounds and experiences learners bring, fostering inclusivity, and promoting a supportive learning community.Additionally, van Gorp (2022) delves into the long-term benefits of learner success, underscoring the enduring impact of effective facilitation. She believes that sustained facilitator support contributes to ongoing learner achievement and development. This perspective aligns with the overarching goal of facilitating quality education, underscoring the importance of facilitators continuously refining their approaches to meet the diverse needs of learners, including neurodivergent individuals. This article underscores the importance of addressing the unique needs of neurodiverse learners in higher education, as van Gorp (2022) and Ker (2017) have emphasised. It highlights that facilitators need to possess adept skills in tailoring approaches to the individual's needs, establishing robust relationships, and recognising the distinctive challenges and strengths of neurodiverse learners. By acknowledging the diverse nature of neurodiversity, facilitators can create an empowering and supportive environment, enabling neurodiverse learners to excel academically. Sustainable education for neurodiverse individuals involves embracing their unique strategies, prioritising resilience, and promoting self-advocacy.Overall, this article demonstrates how the ILP aligns with the vision of "inclusive and equitable quality education and lifelong learning opportunities for all" outlined in SDG 4. It discusses how the ILP approach in New Zealand allows experienced mature learners to obtain qualifications through a learner-centric and flexible process, recognising and valuing all relevant prior learning. The article delves into how the ILP aligns with specific SDG 4 targets, including eliminating gender disparities, ensuring equal access for vulnerable populations, and fostering sustainable development through education. Including a case study featuring a neurodivergent learner and facilitator who successfully completed the ILP journey adds a practical dimension to the discussion.In essence, this article provides valuable insights for those interested in innovative and inclusive vocational education models, offering a holistic perspective on supporting neurodiverse learners and contributing to the broader goals of SDG 4. Bio: Dr Glenys Ker, Associate Professor, Facilitator, Academic Mentor, Assessor WBL Programmes Glenys is a highly experienced work-based learning and professional practice facilitator and assessor, drawing on an extensive and highly successful background as a teacher and career practitioner in both university and polytechnic settings, at undergraduate and postgraduate levels. She is also an active researcher in the field of work-based learning, integrating her research into the development of facilitators of independent learning. Glenys is the primary architect of the independent learning pathway (ILP) approach to qualifications offered through Capable NZ, Otago Polytechnic's work-based and practice-based learning school. Glenys is an experienced leadership and management practitioner, again in multiple educational contexts, including academic and service departments and leadership of independent learning programmes. In her 18 years' experience in this field, she has worked with and supported many neurodiverse learners -something she is hugely grateful for and has learned so much from.Glenys has co-authored with her colleague Dr Heather Carpenter a book on her work: Facilitating Independent Learning in Tertiary Education -new pathways to achievement. Bio: Rachel van Gorp, Senior Lecturer, School of Business Rachel is an accomplished Senior Lecturer with a wide-ranging background, including experience in banking, personal training, massage therapy, business ownership, mentorship, and volunteering. As a member of the Otago Polytechnic School of Business, Rachel brings a wealth of knowledge and expertise to her undergraduate teaching programmes.Rachel is a dedicated advocate for neurodiverse individuals in vocational education and serves as the chair of the Neurodiversity Community of Practice. She is committed to promoting inclusion and equal opportunities for individuals with diverse learning abilities. Her recent completion of her Master of Professional Practice reflects her focus on the essential topic of Neurodiversity in Vocational Education: facilitating success.With her unique combination of experience, Rachel is able to bring a practical perspective to her teaching, engaging learners in real-world scenarios and helping them to develop the skills they need to succeed in their future careers. Her dedication to the field of vocational education has made her a highly respected member of the academic community, and her commitment to promoting neurodiversity is making a significant impact on the lives of her learners and the wider community.

Keywords: ILP, Neurodiverse Learners, SDG Goal 4, facilitator, Vocational Education, Ako, neurodiversity, ILP Strategies

Received: 11 Mar 2024; Accepted: 03 May 2024.

Copyright: © 2024 van Gorp and Ker. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Mrs. Rachel van Gorp, Otago Polytechnic, Dunedin, New Zealand

People also looked at

- Open access

- Published: 10 May 2024

Community-based participatory-research through co-design: supporting collaboration from all sides of disability

- Cloe Benz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6950-8855 1 ,

- Will Scott-Jeffs 2 ,

- K. A. McKercher ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4417-585X 3 ,

- Mai Welsh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7818-0115 2 , 4 ,

- Richard Norman ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3112-3893 1 ,

- Delia Hendrie ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5022-5281 1 ,

- Matthew Locantro 2 &

- Suzanne Robinson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5703-6475 1 , 5

Research Involvement and Engagement volume 10 , Article number: 47 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

27 Accesses

Metrics details

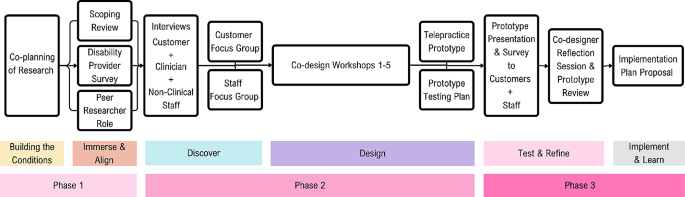

As co-design and community-based participatory research gain traction in health and disability, the challenges and benefits of collaboratively conducting research need to be considered. Current literature supports using co-design to improve service quality and create more satisfactory services. However, while the ‘why’ of using co-design is well understood, there is limited literature on ‘ how ’ to co-design. We aimed to describe the application of co-design from start to finish within a specific case study and to reflect on the challenges and benefits created by specific process design choices.

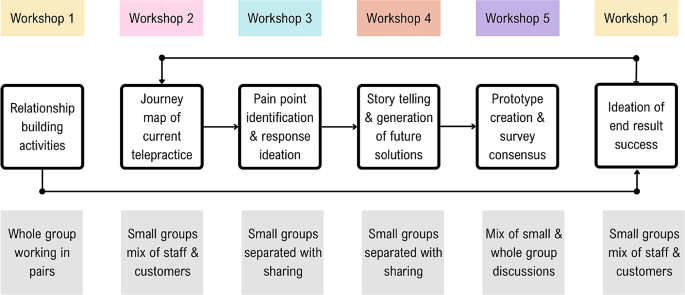

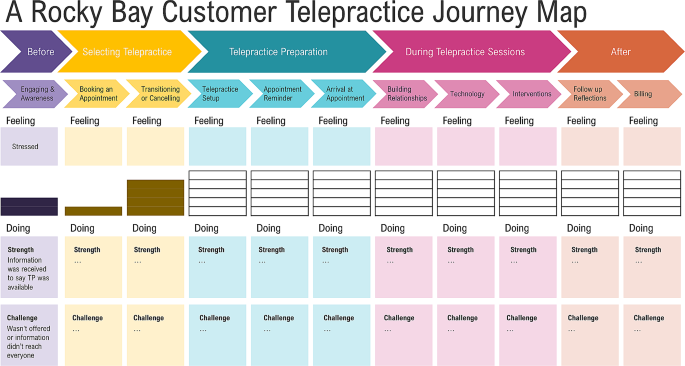

A telepractice re-design project has been a case study example of co-design. The co-design was co-facilitated by an embedded researcher and a peer researcher with lived experience of disability. Embedded in a Western Australian disability organisation, the co-design process included five workshops and a reflection session with a team of 10 lived experience and staff participants (referred to as co-designers) to produce a prototype telepractice model for testing.

The findings are divided into two components. The first describes the process design choices made throughout the co-design implementation case study. This is followed by a reflection on the benefits and challenges resulting from specific process design choices. The reflective process describes the co-designers’ perspective and the researcher’s and organisational experiences. Reflections of the co-designers include balancing idealism and realism, the value of small groups, ensuring accessibility and choice, and learning new skills and gaining new insights. The organisational and research-focused reflections included challenges between time for building relationships and the schedules of academic and organisational decision-making, the messiness of co-design juxtaposed with the processes of ethics applications, and the need for inclusive dissemination of findings.

Conclusions

The authors advocate that co-design is a useful and outcome-generating methodology that proactively enables the inclusion of people with disability and service providers through community-based participatory research and action. Through our experiences, we recommend community-based participatory research, specifically co-design, to generate creative thinking and service design.

Plain language summary

Making better services with communities (called co-design) and doing research with communities (e.g. community-based participatory research) are ways to include people with lived experience in developing and improving the services they use. Academic evidence shows why co-design is valuable, and co-design is increasing in popularity. However, there needs to be more information on how to do co-design. This article describes the process of doing co-design to make telepractice better with a group of lived experience experts and staff at a disability organisation. The co-design process was co-facilitated by two researchers – one with a health background and one with lived experience of disability. Telepractice provides clinical services (such as physiotherapy or nursing) using video calls and other digital technology. The co-design team did five workshops and then reflected on the success of those workshops. Based on the groups’ feedback, the article describes what worked and what was hard according to the co-designers and from the perspective of the researchers and the disability organisation. Topics discussed include the challenge of balancing ideas with realistic expectations, the value of small groups, accessibility and choice opportunities and learning new skills and insights. The research and organisational topics include the need to take time and how that doesn’t fit neatly with academic and business schedules, how the messiness of co-design can clash with approval processes, and different ways of telling people about the project that are more inclusive than traditional research. The authors conclude that co-design and community-based participatory research go well together in including people with lived experience in re-designing services they use.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Co-design has the potential to positively impact co-designers and their community, researchers, and organisations. Co-design is defined as designing with, not for, people [ 1 ] and can reinvigorate business-as-usual processes, leading to new ideas in industry, community and academia. As co-design and community-based participatory research gain traction, the challenges and benefits of collaborative research between people with lived experience and organisations must be considered [ 2 ].

Disability and healthcare providers previously made decisions for individuals as passive targets of an intervention [ 3 ]. By contrast, the involvement of consumers in their care [ 4 ] has been included as part of accreditation processes [ 4 ] and shown to improve outcomes and satisfaction. For research to sufficiently translate into practice, consumers and providers should be involved actively, not passively [ 4 , 5 ].

Approaches such as community-based participatory research promote “a collaborative approach that equitably involves community members, organisational representatives and researchers in all aspects of the research process” [ 6 ] (page 1). This approach originated in public health research and claims to empower all participants to have a stake in project success, facilitating a more active integration of research into practice and decreasing the knowledge to practice gap 6 . Patient and public involvement (PPI) increases the probability that research focus, community priorities and clinical problems align, which is increasingly demanded by research funders and health systems [ 7 ].

As community-based participatory research is an overarching approach to conducting research, it requires a complementary method, such as co-production, to achieve its aims. Co-production has been attributed to the work of Ostrom et al. [ 8 ], with the term co-design falling under the co-production umbrella. However, co-design can be traced back to the participatory design movement [ 9 ]. The term co-production in the context of this article includes co-planning, co-discovery, co-design, co-delivery, and co-evaluation [ 10 ]. Within this framework, the concept of co-design delineates the collaborative process of discovery, creating, ideating and prototyping to design or redesign an output [ 11 ]. The four principles of co-design, as per McKercher [ 1 ], are sharing power, prioritising relationships, using participatory means and building capacity [ 1 ]. This specific method of co-design [ 1 ] has been used across multiple social and healthcare publications [ 10 , 12 , 13 , 14 ].

A systematic review by Ramos et al. [ 15 ] describes the benefits of co-design in a community-based participatory-research approach, including improved quality and more satisfactory services. However, as identified by Rahman et al. [ 16 ], the ‘ why ’ is well known, but there is limited knowledge of ‘ how ’ to co-design. Multiple articles provide high-level descriptions of workshops or briefly mention the co-design process [ 13 , 17 , 18 , 19 ]. Pearce et al. [ 5 ] include an in-depth table of activities across an entire co-creation process, however within each part i.e., co-design, limited descriptions were included. A recent publication by Marwaa et al. [ 20 ] provides an in-depth description of two workshops focused on product development, and Tariq et al. [ 21 ] provides details of the process of co-designing a research agenda. Davis et al. [ 11 ] discuss co-design workshop delivery strategies summarised across multiple studies without articulating the process from start to finish. Finally, Abimbola et al. [ 22 ] provided the most comprehensive description of a co-design process, including a timeline of events and activities; however, this project only involved clinical staff and did not include community-based participation.

As “We know the why, but we need to know the how-to” [ 16 ] (page 2), of co-design, our primary aim was to describe the application of co-design from start to finish within a specific case study. Our secondary aim was to reflect on the challenges and benefits created by specific process design choices and to provide recommendations for future applications of co-design.

Overview of telepractice project

The case study, a telepractice redesign project, was based at Rocky Bay, a disability support service provider in Perth, Australia [ 23 ]. The project aimed to understand the strengths and pain points of telepractice within Rocky Bay. We expanded this to include telepractice in the wider Australian disability sector. The project also aimed to establish potential improvements to increase the uptake and sustainability of Rocky Bay’s telepractice service into the future. Rocky Bay predominantly serves people under the Australian National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) [ 24 ] by providing a variety of services, including allied health (e.g. physiotherapy, dietetics, speech pathology, etc.), nursing care (including continence and wound care), behaviour support and support coordination [ 23 ]—Rocky Bay services metropolitan Perth and regional Western Australia [ 23 ].