- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 28, 2023 | Original: October 29, 2009

The New Deal was a series of programs and projects instituted during the Great Depression by President Franklin D. Roosevelt that aimed to restore prosperity to Americans. When Roosevelt took office in 1933, he acted swiftly to stabilize the economy and provide jobs and relief to those who were suffering. Over the next eight years, the government instituted a series of experimental New Deal projects and programs, such as the CCC , the WPA , the TVA, the SEC and others. Roosevelt’s New Deal fundamentally and permanently changed the U.S. federal government by expanding its size and scope—especially its role in the economy.

New Deal for the American People

On March 4, 1933, during the bleakest days of the Great Depression , newly elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt delivered his first inaugural address before 100,000 people on Washington’s Capitol Plaza.

“First of all,” he said, “let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”

He promised that he would act swiftly to face the “dark realities of the moment” and assured Americans that he would “wage a war against the emergency” just as though “we were in fact invaded by a foreign foe.” His speech gave many people confidence that they’d elected a man who was not afraid to take bold steps to solve the nation’s problems.

Did you know? Unemployment levels in some cities reached staggering levels during the Great Depression: By 1933, Toledo, Ohio's had reached 80 percent, and nearly 90 percent of Lowell, Massachusetts, was unemployed.

The next day, Roosevelt declared a four-day bank holiday to stop people from withdrawing their money from shaky banks. On March 9, Congress passed Roosevelt’s Emergency Banking Act, which reorganized the banks and closed the ones that were insolvent.

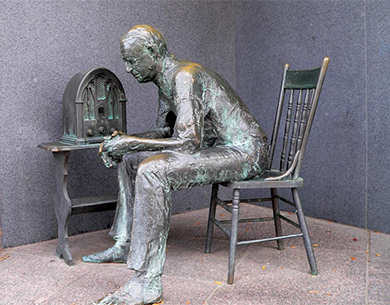

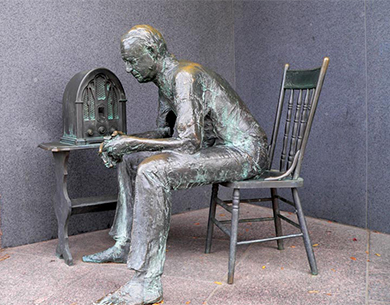

In his first “ fireside chat ” three days later, the president urged Americans to put their savings back in the banks, and by the end of the month almost three quarters of them had reopened.

The First Hundred Days

Roosevelt’s quest to end the Great Depression was just beginning, and would ramp up in what came to be known as “ The First 100 Days .” Roosevelt kicked things off by asking Congress to take the first step toward ending Prohibition —one of the more divisive issues of the 1920s—by making it legal once again for Americans to buy beer. (At the end of the year, Congress ratified the 21st Amendment and ended Prohibition for good.)

In May, he signed the Tennessee Valley Authority Act into law, creating the TVA and enabling the federal government to build dams along the Tennessee River that controlled flooding and generated inexpensive hydroelectric power for the people in the region.

That same month, Congress passed a bill that paid commodity farmers (farmers who produced things like wheat, dairy products, tobacco and corn) to leave their fields fallow in order to end agricultural surpluses and boost prices.

June’s National Industrial Recovery Act guaranteed that workers would have the right to unionize and bargain collectively for higher wages and better working conditions; it also suspended some antitrust laws and established a federally funded Public Works Administration.

In addition to the Agricultural Adjustment Act, the Tennessee Valley Authority Act and the National Industrial Recovery Act, Roosevelt had won passage of 12 other major laws, including the Glass-Steagall Act (an important banking bill) and the Home Owners’ Loan Act, in his first 100 days in office.

Almost every American found something to be pleased about and something to complain about in this motley collection of bills, but it was clear to all that FDR was taking the “direct, vigorous” action that he’d promised in his inaugural address.

Second New Deal

Despite the best efforts of President Roosevelt and his cabinet, however, the Great Depression continued. Unemployment persisted, the economy remained unstable, farmers continued to struggle in the Dust Bowl and people grew angrier and more desperate.

So, in the spring of 1935, Roosevelt launched a second, more aggressive series of federal programs, sometimes called the Second New Deal.

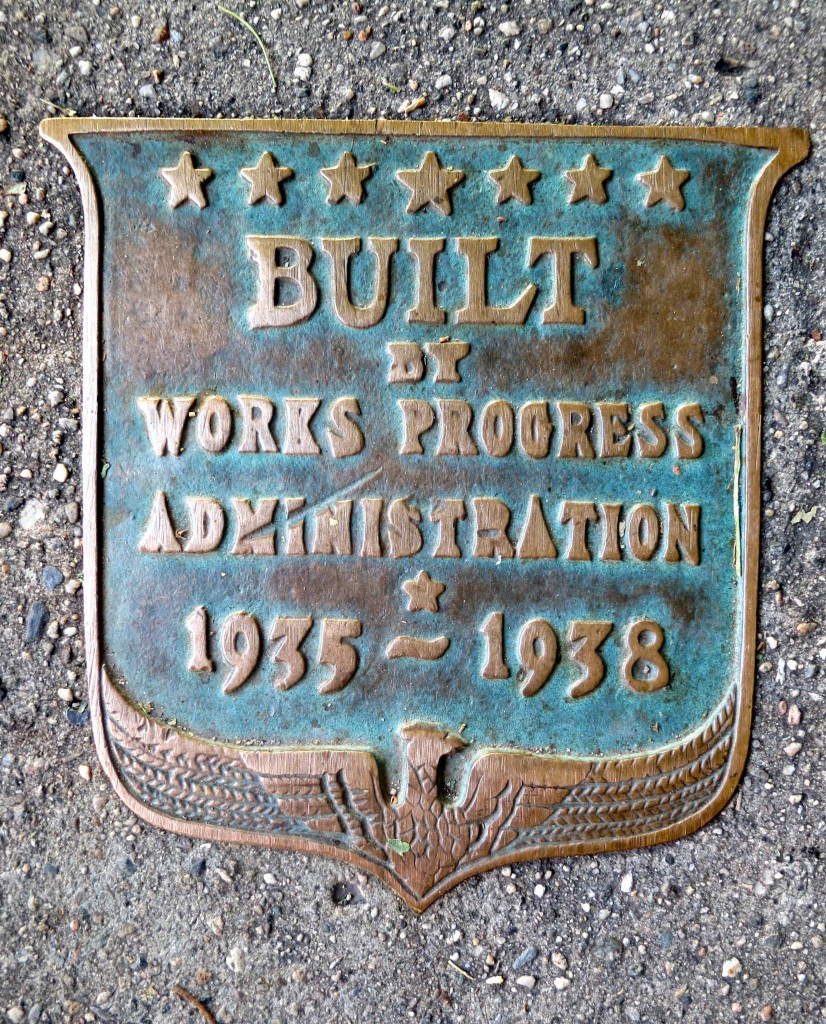

In April, he created the Works Progress Administration (WPA) to provide jobs for unemployed people. WPA projects weren’t allowed to compete with private industry, so they focused on building things like post offices, bridges, schools, highways and parks. The WPA also gave work to artists, writers, theater directors and musicians.

In July 1935, the National Labor Relations Act , also known as the Wagner Act, created the National Labor Relations Board to supervise union elections and prevent businesses from treating their workers unfairly. In August, FDR signed the Social Security Act of 1935, which guaranteed pensions to millions of Americans, set up a system of unemployment insurance and stipulated that the federal government would help care for dependent children and the disabled.

In 1936, while campaigning for a second term, FDR told a roaring crowd at Madison Square Garden that “The forces of ‘organized money’ are unanimous in their hate for me—and I welcome their hatred.”

He went on: “I should like to have it said of my first Administration that in it the forces of selfishness and of lust for power met their match, [and] I should like to have it said of my second Administration that in it these forces have met their master.”

This FDR had come a long way from his earlier repudiation of class-based politics and was promising a much more aggressive fight against the people who were profiting from the Depression-era troubles of ordinary Americans. He won the election by a landslide.

Still, the Great Depression dragged on. Workers grew more militant: In December 1936, for example, the United Auto Workers strike at a GM plant in Flint, Michigan lasted for 44 days and spread to some 150,000 autoworkers in 35 cities.

By 1937, to the dismay of most corporate leaders, some 8 million workers had joined unions and were loudly demanding their rights.

The End of the New Deal?

Meanwhile, the New Deal itself confronted one political setback after another. Arguing that they represented an unconstitutional extension of federal authority, the conservative majority on the Supreme Court had already invalidated reform initiatives like the National Recovery Administration and the Agricultural Adjustment Administration.

In order to protect his programs from further meddling, in 1937 President Roosevelt announced a plan to add enough liberal justices to the Court to neutralize the “obstructionist” conservatives.

This “ Court-packing ” turned out to be unnecessary—soon after they caught wind of the plan, the conservative justices started voting to uphold New Deal projects—but the episode did a good deal of public-relations damage to the administration and gave ammunition to many of the president’s Congressional opponents.

That same year, the economy slipped back into a recession when the government reduced its stimulus spending. Despite this seeming vindication of New Deal policies, increasing anti-Roosevelt sentiment made it difficult for him to enact any new programs.

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor and the United States entered World War II . The war effort stimulated American industry and, as a result, effectively ended the Great Depression .

The New Deal and American Politics

From 1933 until 1941, President Roosevelt’s New Deal programs and policies did more than just adjust interest rates, tinker with farm subsidies and create short-term make-work programs.

They created a brand-new, if tenuous, political coalition that included white working people, African Americans and left-wing intellectuals. More women entered the workforce as Roosevelt expanded the number of secretarial roles in government. These groups rarely shared the same interests—at least, they rarely thought they did— but they did share a powerful belief that an interventionist government was good for their families, the economy and the nation.

Their coalition has splintered over time, but many of the New Deal programs that bound them together—Social Security, unemployment insurance and federal agricultural subsidies, for instance—are still with us today.

Photo Galleries

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

The New Deal — A Guide to FDR’s Plan for Relief, Recovery, and Reform

The New Deal was a series of programs and policies implemented in the 1930s by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in response to severe economic and social issues in the United States.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1944. Image Source: FDR Presidential Library & Museum on Flickr .

New Deal Summary

The New Deal was a series of programs and policies implemented in the 1930s by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt — commonly referred to as FDR — in response to severe economic and social issues in the United States. Each New Deal program and policy fell into one or more of three areas, known as the “Three Rs” — Relief, Recovery, and Reform.

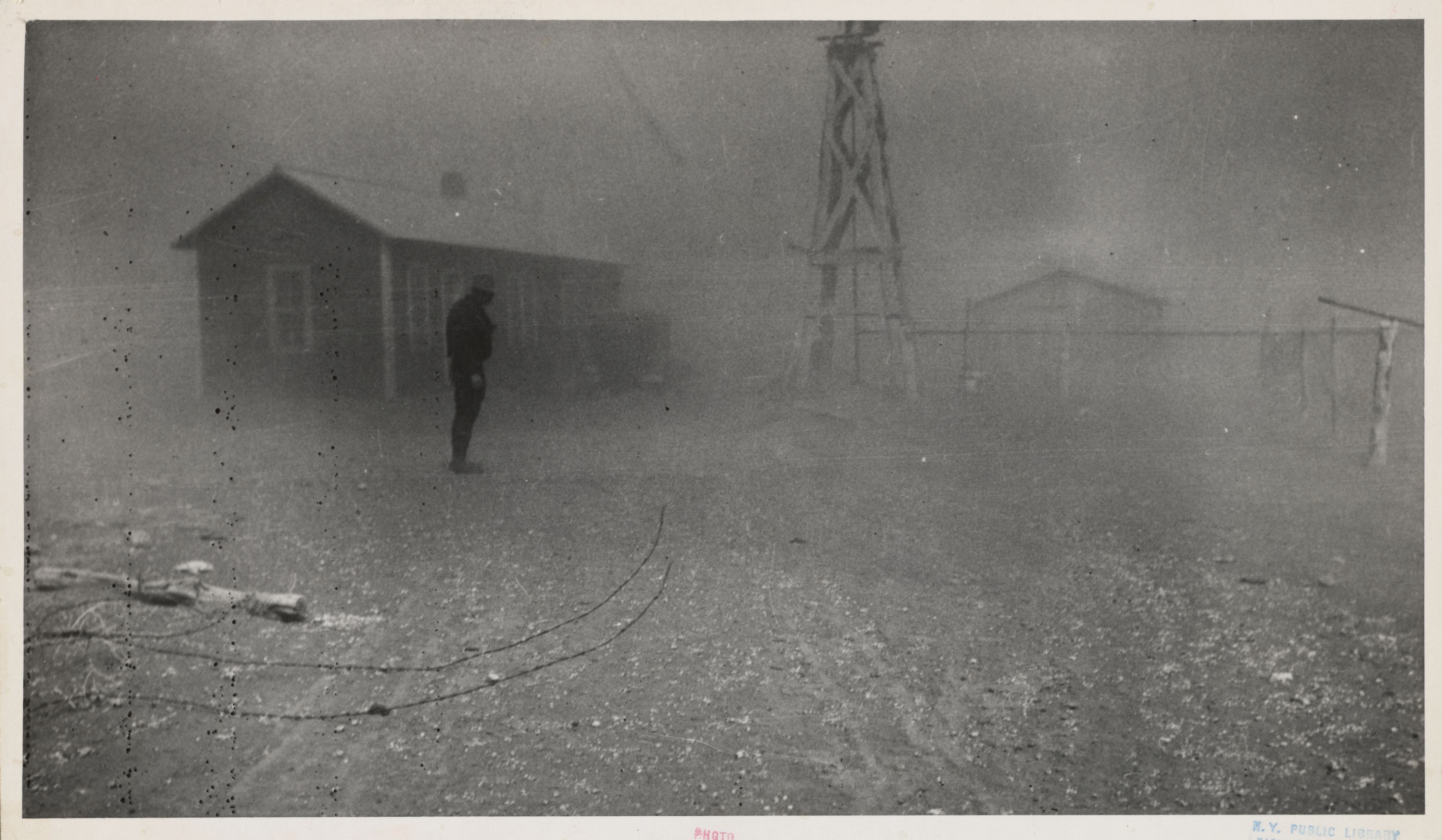

At the end of the Roaring Twenties, the 1929 Stock Market Crash triggered the Great Depression started when the stock market crashed in 1929. Starting in 1931, the southwestern Great Plains suffered from a severe drought, which led to massive dust storms. The area was called “The Dust Bowl” and thousands of people were forced to abandon their homes and move west. In the wake of these events, Roosevelt ran for President in 1932, promising a “New Deal” for Americans, and defeated incumbent Herbert Hoover.

Roosevelt was inaugurated on March 4, 1933. In his First Inaugural Address, he delivered the famous line, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” FDR moved quickly to ease the effects of the Depression on Americans by passing New Deal legislation during “The First Hundred Days” of his Presidency.

FDR started by restoring faith in banks, which had suffered due to the stock market crash of 1929. A Bank Holiday was declared and Congress followed by passing the Emergency Banking Relief Act, which allowed the government to inspect the financial health of banks before allowing them to reopen.

The New Deal aimed to tackle unemployment by creating programs that provided job opportunities. The Civil Works Administration (CWA) and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) employed millions of Americans to work on infrastructure projects, such as building roads, bridges, and schools. Other programs, like the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), developed hydroelectric power plants to bring electricity to communities where none existed.

The New Deal also addressed labor relations by passing the National Labor Relations Act — also known as the (Wagner Act). It protected the rights of workers, allowing them to join unions and engage in collective bargaining. The act also established the Fair Labor Standards Act, which set a minimum wage for workers.

The New Deal programs and policies created a significant expansion of the Federal government. They also redefined the government’s role in dealing with economic and social issues. The New Deal was controversial when it was implemented, and its legacy continues to be debated by historians, economists, and others. However, the significance of the New Deal and its impact on the United States during the era leading up to World War II cannot be denied.

What did the New Deal do?

This video from the Daily Bellringer provides an overview of the New Deal and its programs. It also touches on the controversy caused by the New Deal which was caused by the expansion of the Federal Government.

New Deal Facts

- The name “New Deal” came from Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1932 acceptance speech for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination. In the speech, he said, “I pledge you, I pledge myself, to a new deal for the American people.”

- The New Deal was designed to deal with the economic and social issues created by the 1929 Stock Market Crash, the Great Depression, and the Dust Bow.

- On March 4, 1933, Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected President. He gave a speech on Capitol Plaza in Washington DC to 100,000 people. He said the “only thing we should be afraid of is fear itself.”

- He took action right away by calling Congress into a special session known as “The Hundred Days,” during which legislation was passed to deal with the Depression and provide economic aid to struggling Americans.

- In an effort to restore the public’s confidence in banks, FDR declared a Bank Holiday and Congress passed the Emergency Banking Relief Act.

- The New Deal dealt with unemployment by creating programs like the Civil Works Administration (CWA) and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), providing jobs for millions of Americans and improving the nation’s infrastructure.

- The New Deal was followed by the Second New Deal, which included the National Labor Relations Act, the Works Progress Administration, and the Social Security Act.

- The New Deal also included labor-related legislation, such as the National Labor Relations Act (Wagner Act) and the Fair Labor Standards Act, which gave workers the right to join unions, negotiate collectively, and established a minimum wage.

- The New Deal paved the way for the repeal of the 18th Amendment, which established Prohibition. The Beer-Wine Revenue Act of 1933 amended the Volstead Act by raising the amount of alcohol allowed to 3.2 percent and also levied a tax.

- Social programs established by the New Deal are still in effect today, including Social Security and the “Food Stamp Plan.”

New Deal AP US History (APUSH) Terms, Definitions, and FAQs

This section provides terms, definitions, and Frequently Asked Questions about the New Deal and the Second New Deal, including people, events, and programs. Also, be sure to look at our Guide to the AP US History Exam .

The New Deal was a series of policies and programs implemented by President Franklin D. Roosevelt during the 1930s in response to the Great Depression. The New Deal aimed to provide relief to the unemployed and poor, promote economic recovery, and reform the financial system. The New Deal included programs such as the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), and the National Recovery Administration (NRA). It also created numerous agencies and programs such as the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), and the Social Security Administration.

The second phase of the New Deal, which was enacted in 1935. The Second New Deal focused on providing economic security to Americans through the creation of Social Security and other welfare programs. It also included measures to stimulate the economy, such as the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA). The Second New Deal was instrumental in helping to alleviate poverty and providing employment opportunities during the Great Depression.

FDR’s Alphabet Soup refers to the numerous programs and agencies created during Franklin D. Roosevelt’s presidency as part of the New Deal. These initiatives, often known by their acronyms, aimed to provide relief, recovery, and reform during the Great Depression. Examples include the CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps), the TVA (Tennessee Valley Authority), and the WPA (Works Progress Administration).

The New Deal was a series of economic programs and reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt during the Great Depression. The New Deal sought to provide relief, recovery, and reform to the American economy. It included programs such as Social Security, the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), and the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). These programs were instrumental in helping to protect workers’ rights and providing employment opportunities during the Great Depression. However, the New Deal was controversial, with some arguing it was a “raw deal” for workers and others arguing that it helped to alleviate the suffering of millions of Americans.

The three Rs of the New Deal were 1) Relief for the needy, 2) Recovery of the economy, and 3) Reform of the financial system. Each of the New Deal Programs generally fell into one of these areas. The goal of the three Rs was to keep the United States from falling into another Economic Depression.

New Deal People and Groups

Herbert Hoover — Herbert Hoover served as the 31st President of the United States from 1929 to 1933. He faced the immense challenges of the Great Depression and was criticized for his belief in limited government intervention. Despite his efforts to address the crisis, Hoover’s presidency is often associated with economic hardships and the initial response to the Depression.

John L. Lewis — An American labor leader who was instrumental in the formation of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) in 1935. He was a key figure in the Second New Deal and helped to pass the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA). He was also responsible for leading several major strikes during the Great Depression, including the United Mine Workers strike of 1934. Lewis worked to protect workers’ rights and provide employment opportunities during the Great Depression.

Franklin D. Roosevelt — Franklin D. Roosevelt was the 32nd President of the United States, serving from 1933 to 1945. He was elected to the presidency during the Great Depression, and his presidency is closely associated with the New Deal, a series of policies and programs aimed at addressing the economic crisis and promoting economic recovery. He was re-elected for an unprecedented four terms and his leadership during the Great Depression and World War II solidified the role of the Federal government in the American economy and society.

Eleanor Roosevelt — The wife of Franklin D. Roosevelt and one of the most influential First Ladies in American history. She was an advocate for civil rights and women’s rights, and she used her position to promote social reform.

FDR’s Brain Trust — A group of advisors to President Franklin D. Roosevelt who helped him develop the New Deal. They included prominent academics and intellectuals such as Raymond Moley, Rexford Tugwell, and Adolf Berle.

New Deal Democrats — New Deal Democrats were a faction within the Democratic Party during the 1930s and 1940s that supported Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal policies. These Democrats supported increasing government intervention in the economy and expanding social welfare programs.

United Mine Workers — A labor union that was formed in 1890. The union was instrumental in the formation of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) in 1935 and led several major strikes during the Great Depression, including the United Mine Workers strike of 1934.

Hundred Days Congress — The Hundred Days Congress was a special session of the United States Congress that ran from March 9 to June 16, 1933. It was called in response to the economic crisis of the Great Depression and was used to pass a number of laws known as the New Deal. During this period, President Franklin D. Roosevelt proposed a series of sweeping reforms designed to provide relief for those affected by the depression, as well as to stimulate the economy. The Hundred Days Congress passed a number of laws, including the Emergency Banking Relief Act, the Glass-Steagall Act, and the National Industrial Recovery Act.

New Deal Events

1932 Presidential Election — The 1932 Presidential Election marked a pivotal moment in American history as the nation grappled with the Great Depression. It was primarily a contest between Republican incumbent Herbert Hoover and Democratic candidate Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR). FDR emerged victorious, promising a “New Deal” to combat the Depression and implementing a series of reforms that fundamentally reshaped the role of the federal government.

Bank Holiday — A bank holiday is a period of time during which banks are closed, usually by government order. In 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared a national bank holiday in order to address the banking crisis caused by the Great Depression. During the holiday, which lasted four days, the government examined the books of all banks and only those that were found to be sound were allowed to reopen. This action helped stabilize the banking system and restore public confidence in banks.

Fireside Chats — The Fireside Chats were a series of radio addresses given by President Franklin D. Roosevelt during his presidency. The chats were designed to provide the American people with information about the government’s policies and actions and to explain the reasoning behind them in plain language. The chats were informal and conversational in tone, and they were delivered from the White House, often in the evening, giving the impression that Roosevelt was speaking directly to the American people from the warmth and comfort of their own homes. The Fireside Chats were a powerful tool for Roosevelt to communicate with the American people, build public support for his policies and maintain public confidence during a time of economic crisis.

Great Depression — The Great Depression refers to the severe economic downturn that occurred in the United States and other countries during the 1930s. It was characterized by widespread unemployment, poverty, and a sharp decline in industrial production and trade—ultimately leading to a fundamental restructuring of the American economy and significant social and political changes.

Roosevelt Recession — A period of economic contraction that occurred during the Great Depression, starting in 1937 and lasting until 1938. It was caused by a combination of factors, including President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s decision to reduce government spending, an increase in taxes, and the Federal Reserve’s decision to raise interest rates. This resulted in a decrease in consumer spending and investment, leading to a decrease in economic activity. The Roosevelt Recession was a major setback for the New Deal and led to increased unemployment and poverty.

United Mine Workers Strike of 1934 — A major strike led by the United Mine Workers Union during the Great Depression. The strike was in response to wage cuts and other grievances. It lasted for several months and resulted in a victory for the miners, who were able to secure higher wages and better working conditions.

New Deal Programs

Agricultural Adjustment Act (1933) — A law passed by Congress in 1933 as part of the New Deal. The AAA was designed to help farmers by providing subsidies for reducing crop production and encouraging soil conservation. It also established the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA), which was responsible for implementing the provisions of the act. The AAA was instrumental in helping to stabilize agricultural prices and providing economic relief to farmers during the Great Depression.

Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) — The CCC provided employment for young men between the ages of 18 and 25, who were paid to work on conservation projects such as planting trees, building roads, and constructing dams. The CCC also provided educational opportunities for its workers, including classes in literacy, math, and vocational skills. The CCC was instrumental in helping to restore the environment and providing employment opportunities during the Great Depression.

Civil Works Administration (CWA) — An agency created by the Federal Emergency Relief Act of 1933 as part of the New Deal. The CWA was responsible for providing jobs to millions of Americans during the Great Depression. It provided employment in construction, repair, and maintenance projects such as building roads, bridges, and public buildings. The CWA was instrumental in helping to alleviate poverty and providing employment opportunities during the Great Depression.

Emergency Banking Relief Act (1933) — A law passed by Congress in 1933 which allowed the federal government to provide emergency loans to banks in order to stabilize the banking system. The act was part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal and was designed to restore public confidence in the banking system. It provided for the reopening of solvent banks, the reorganization of insolvent banks, and the establishment of a Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) to insure deposits up to $2,500. The act was instrumental in helping to stabilize the banking system during the Great Depression and restoring public confidence in banks.

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) — An independent agency of the United States government created in 1933 as part of the New Deal. The FDIC provides insurance for deposits up to a certain amount in member banks, protecting depositors from losses due to bank failures. The FDIC also regulates and supervises financial institutions to ensure that they are operating safely and soundly. It is one of the most important financial regulatory agencies in the United States and has helped to restore public confidence in the banking system.

Federal Emergency Relief Act (1933) — A law passed by Congress in 1933 as part of the New Deal. The FERA provided federal funds to states and local governments to create relief programs for the unemployed. It also established the Civil Works Administration (CWA), which was responsible for providing jobs to millions of Americans during the Great Depression. The FERA was instrumental in helping to alleviate poverty and providing employment opportunities during the Great Depression.

Federal Housing Administration (FHA) — An agency created by the National Housing Act of 1934 as part of the New Deal. The FHA was responsible for providing mortgage insurance to lenders, which allowed them to make home loans with lower down payments and easier credit requirements. This helped to increase homeownership and provided jobs to thousands of Americans during the Great Depression. The FHA helped stabilize the housing market and provide employment opportunities during the Great Depression.

Glass-Steagall Act (1933) — The Glass-Steagall Act was a law passed by Congress in 1933 as part of the New Deal. It was designed to separate commercial and investment banking, and it prohibited banks from engaging in certain types of speculative investments. The act also established the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), which provided insurance for bank deposits up to a certain amount. The Glass-Steagall Act helped restore public confidence in the banking system and prevent another financial crisis.

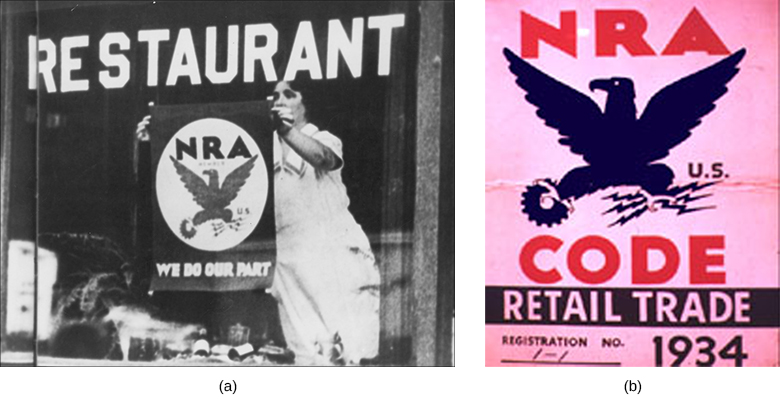

National Industrial Recovery Act (1933) — The National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) was a law passed by Congress in 1933 as part of the New Deal. It was designed to stimulate economic growth by providing government assistance to businesses, setting minimum wages and maximum hours for workers, and establishing codes of fair competition. The NIRA also established the National Recovery Administration (NRA), which was responsible for enforcing the provisions of the act. The NIRA was eventually declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1935.

The Public Works Administration (PWA) — An agency created by the National Recovery Administration of 1933 as part of the New Deal. The PWA was responsible for providing jobs to millions of Americans during the Great Depression. It provided employment in construction, repair, and maintenance projects such as building roads, bridges, and public buildings. The PWA played an important role in helping to alleviate poverty and providing employment opportunities during the Great Depression.

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) — An agency created by the Tennessee Valley Authority Act of 1933 as part of the New Deal. The TVA was responsible for developing the infrastructure and resources of the Tennessee Valley region, including hydroelectric power, flood control, navigation, reforestation, and soil conservation. It also provided jobs to thousands of Americans during the Great Depression. The TVA played an important role in helping modernize the region and providing employment opportunities during the Great Depression.

Second New Deal Programs

Committee for Industrial Organizations (CIO) — An organization formed in 1935 as part of the Second New Deal. The CIO was responsible for organizing workers into unions and bargaining collectively with employers.

Fair Labor Standards Act (1938) — An act passed in 1938 as part of the Second New Deal. The Fair Labor Standards Act was responsible for establishing a minimum wage, overtime pay, and other labor standards.

National Labor Relations Act (1935) — An act passed in 1935 as part of the Second New Deal. The NLRA was responsible for protecting the rights of workers to organize and bargain collectively with their employers. It also established the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), which was responsible for enforcing the provisions of the act.

Social Security Act (1935) — An act passed as part of the Second New Deal. The Social Security Act was responsible for providing economic security to Americans through the establishment of a federal retirement program and other welfare programs. It also provided unemployment insurance and disability benefits.

Wagner Act — Also known as the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), it was passed in 1935 as part of the Second New Deal. The Wagner Act was responsible for protecting the rights of workers to organize and bargain collectively with their employers. It also established the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), which was responsible for enforcing the provisions of the act.

Works Progress Administration (WPA) — An agency created by the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act of 1935 as part of the Second New Deal. The WPA was responsible for providing jobs to millions of Americans during the Great Depression. It funded a variety of projects, including construction, infrastructure development, and arts and culture programs. The WPA was instrumental in helping to stimulate the economy and providing employment opportunities during the Great Depression.

More New Deal Terms and Definitions

21st Amendment — The amendment to the U.S. Constitution that repealed the 18th Amendment and ended Prohibition. The 21st Amendment was ratified in 1933 as part of the New Deal and allowed states to regulate the sale and consumption of alcohol within their borders. It also gave states the power to collect taxes on alcohol sales, which provided a much-needed source of revenue during the Great Depression.

Boondoggling — A term coined by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to describe wasteful government spending on public works projects. The term was used to criticize the New Deal programs, which were seen as a form of government waste and corruption. Boondoggling became a popular term during the Great Depression and is still used today to refer to any wasteful or unnecessary government spending.

Tennessee River Valley — The Tennessee River Valley refers to the region in the southeastern United States encompassing parts of Tennessee, Alabama, and Kentucky. It gained prominence during the New Deal era due to the establishment of the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), a federal agency tasked with developing the area’s water resources, controlling flooding, and promoting economic development through hydroelectric power generation and irrigation projects.

National Parks — National Parks are protected areas designated by the federal government to preserve and showcase the country’s natural, historical, and cultural heritage. These areas, managed by the National Park Service, offer opportunities for recreation, conservation, and education. Notable examples include Yellowstone, Yosemite, and the Grand Canyon. National Parks serve as significant landmarks and contribute to the nation’s tourism industry and environmental conservation efforts.

Why is the New Deal important?

The New Deal is important to United States history for several reasons:

1. Response to the Great Depression: The New Deal was a direct response to the economic crisis of the Great Depression, which was one of the most challenging periods in American history. It represented a major shift in the role of the federal government in addressing economic issues and providing relief to citizens.

2. Economic Recovery and Relief: The New Deal implemented a range of programs and policies aimed at stabilizing the economy, creating jobs, and providing relief to those affected by the Great Depression. It helped alleviate immediate suffering and provided assistance to millions of Americans through employment, financial aid, and social welfare programs.

3. Expansion of Federal Government Power: The New Deal marked a significant expansion of the federal government’s role in regulating the economy and addressing social issues. It introduced new agencies and programs, such as the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and Social Security, that had long-lasting impacts on American society and established a precedent for increased government intervention in the economy.

4. Transformation of American Society: The New Deal’s programs had a transformative effect on American society. It brought about improvements in infrastructure, public works, and conservation projects, enhancing the nation’s physical landscape. It also introduced labor reforms, such as the right to unionize and the establishment of minimum wage standards, which aimed to improve working conditions and workers’ rights.

5. Legacy and Long-Term Impacts: Many of the programs and policies initiated during the New Deal era had lasting impacts on American society. Social Security, for example, continues to provide financial security to elderly and disabled Americans. The New Deal also shaped the political landscape, as the Democratic Party under FDR gained support from various social groups and established a coalition that would dominate American politics for decades.

- Written by Randal Rust

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- 20th Century: Post-1945

- 20th Century: Pre-1945

- African American History

- Antebellum History

- Asian American History

- Civil War and Reconstruction

- Colonial History

- Cultural History

- Early National History

- Economic History

- Environmental History

- Foreign Relations and Foreign Policy

- History of Science and Technology

- Labor and Working Class History

- Late 19th-Century History

- Latino History

- Legal History

- Native American History

- Political History

- Pre-Contact History

- Religious History

- Revolutionary History

- Slavery and Abolition

- Southern History

- Urban History

- Western History

- Women's History

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

The new deal.

- Wendy L. Wall Wendy L. Wall Department of History, SUNY Binghamton

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.87

- Published online: 22 December 2016

The New Deal generally refers to a set of domestic policies implemented by the administration of Franklin Delano Roosevelt in response to the crisis of the Great Depression. Propelled by that economic cataclysm, Roosevelt and his New Dealers pushed through legislation that regulated the banking and securities industries, provided relief for the unemployed, aided farmers, electrified rural areas, promoted conservation, built national infrastructure, regulated wages and hours, and bolstered the power of unions. The Tennessee Valley Authority prevented floods and brought electricity and economic progress to seven states in one of the most impoverished parts of the nation. The Works Progress Administration offered jobs to millions of unemployed Americans and launched an unprecedented federal venture into the arena of culture. By providing social insurance to the elderly and unemployed, the Social Security Act laid the foundation for the U.S. welfare state.

The benefits of the New Deal were not equitably distributed. Many New Deal programs—farm subsidies, work relief projects, social insurance, and labor protection programs—discriminated against racial minorities and women, while profiting white men disproportionately. Nevertheless, women achieved symbolic breakthroughs, and African Americans benefited more from Roosevelt’s policies than they had from any past administration since Abraham Lincoln’s. The New Deal did not end the Depression—only World War II did that—but it did spur economic recovery. It also helped to make American capitalism less volatile by extending federal regulation into new areas of the economy.

Although the New Deal most often refers to policies and programs put in place between 1933 and 1938, some scholars have used the term more expansively to encompass later domestic legislation or U.S. actions abroad that seemed animated by the same values and impulses—above all, a desire to make individuals more secure and a belief in institutional solutions to long-standing problems. In order to pass his legislative agenda, Roosevelt drew many Catholic and Jewish immigrants, industrial workers, and African Americans into the Democratic Party. Together with white Southerners, these groups formed what became known as the “New Deal coalition.” This unlikely political alliance endured long after Roosevelt’s death, supporting the Democratic Party and a “liberal” agenda for nearly half a century. When the coalition finally cracked in 1980, historians looked back on this extended epoch as reflecting a “New Deal order.”

- Franklin Delano Roosevelt

- Great Depression

- Hundred Days

- work relief

- industrial unionism

- Tennessee Valley Authority

- Works Progress Administration

- Social Security

Defining the “New Deal”

On July 2, 1932 , Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) accepted the Democratic Party’s nomination for president and pledged himself to a “new deal for the American people.” 1 In so doing, he gave a name not only to a set of domestic policies implemented by his administration in response to the crisis of the Great Depression but also to an era, a political coalition, and a vision of government’s role in society. The New Deal has been described as a “potpourri” of sometimes-conflicting policy initiatives, and scholars and popular commentators have long debated its ideological sources, beneficiaries, and legacy. 2 Nevertheless, most agree that it marked “a pivotal moment in the making of modern American liberalism.” 3 As this suggests, the New Deal cast a long shadow over the remainder of the 20th century, and it remains a touchstone for contemporary political debate.

When Roosevelt took office in March 1933 , the nation was more than three years into the greatest economic cataclysm that either the United States or global capitalism had ever experienced. The stock market crash in October 1929 had led to a financial meltdown, prompting a collapse in industrial production that began in the United States but soon spread to other countries. A rise in prices for raw materials—commodities ranging from cotton and wheat to tea, silk, lumber, and steel—soon followed. This prostrated farmers, miners, and loggers, not only in the United States but also around the globe. By the spring of 1933 , the U.S. gross national product had fallen to just half of its 1929 level. More than five thousand U.S. banks had failed, and thousands of families across the country had already lost farms and homes to foreclosure. On the day Roosevelt was inaugurated, roughly one-quarter of the American workforce was unemployed. In cities like Chicago and Detroit, home to hard-hit industries like automobiles and steel, the unemployment rate approached 50 percent. 4

On the campaign trail, Roosevelt had been vague about precisely how he planned to grapple with the economic crisis: He famously recommended “bold, persistent experimentation.” 5 Once in office, the president turned his abundant energy to implementing this pragmatic philosophy. He surrounded himself with advisors who had strikingly different viewpoints and agendas, and set them to work tackling a troika of problems: relief, recovery, and reform. 6 The result was one of the greatest outpourings of legislation ever seen in American history. Between 1933 and 1938 , Roosevelt and his New Dealers pushed through legislation that, among other things, regulated the banking and securities industries, shored up agricultural prices, established vast public works projects, repealed Prohibition, created new mortgage markets, managed watersheds, reversed a half century of American Indian policy, bolstered the power of unions, and provided social insurance to millions of elderly, unemployed, and disabled Americans. As historian David M. Kennedy has written, “Into the five years of the New Deal was crowded more social and institutional change than into virtually any comparable compass of time in the nation’s past.” 7

As Kennedy suggests, the term New Deal is most often used to refer to the set of domestic policies implemented by the Roosevelt administration in the 1930s in response to the Great Depression. In this narrow sense, the “New Deal” might be seen as paralleling Teddy Roosevelt’s “Square Deal,” Harry Truman’s “Fair Deal,” or Lyndon B. Johnson’s “Great Society.” Scholars have also used the term more expansively to encompass later domestic legislation that seemed to be animated by the same values and impulses. Glenn Altschuler and Stuart Blumin, for instance, argue that the 1944 GI Bill built on specific New Deal policies, while reflecting FDR’s broader desire to use the power of the federal government to extend a safety net to American citizens. For this reason, they dub the GI bill “a New Deal for veterans.” 8 Ira Katznelson goes even further, redefining the New Deal as “the full period of Democratic rule” that stretched from Roosevelt’s election in 1932 to the election of Dwight Eisenhower two decades later. Only by looking at this longer time span, he suggests, can historians understand how the New Deal “reconsidered and rebuilt the country’s long-established political order.” 9

If some historians have extended the chronology of the New Deal, others have expanded its geographic scope. Scholars have most often applied the term to FDR’s domestic agenda, but Elizabeth Borgwardt argues that there was also a “New Deal for the world.” As World War II drew to a close, she suggests, Roosevelt administration planners translated “the New Deal’s sweeping institutional approaches to intractable problems” to the international arena, establishing a framework of multilateral institutions designed to stabilize the global system and advance human rights. The International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the United Nations, and the charter that set the parameters for the Nuremberg Trials were designed to extend economic and political security to people around the globe, she writes, “much as New Deal programs had redefined security domestically for individual American citizens.” 10 In a similar vein, Kiran Klaus Patel argues that the United States “played a major role in redefining the international order by trying to project the principles of the New Deal regulatory state onto the world.” 11 Sarah Phillips suggests that the success of New Deal programs like the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) convinced many liberals that they had “found the tools for conquering the problem of rural poverty.” The postwar Point Four program of foreign assistance, she argues, drew on these lessons and attempted to “export the New Deal.” 12

Neither the domestic nor the global New Deal would have been possible had FDR not mobilized a new political coalition. From 1896 until 1932 , the Republican Party dominated national politics; only in the “Solid South,” which had opposed Republicans since the Civil War, did the Democratic Party consistently win elections. In 1932 , Roosevelt swept into office largely because of widespread animosity toward President Herbert Hoover, who had failed to end the Depression or significantly ameliorate suffering. Over the next four years, however, Roosevelt won over Catholic and Jewish immigrants and their voting-age children, industrial workers, African Americans, and large segments of the so-called chattering classes. Together with white Southerners, these groups formed what became known as the “New Deal coalition.”

The New Deal coalition brought together unlikely bedfellows—for instance, African Americans and union members with conservative white Southerners who opposed racial equality and organized labor. Nevertheless, this unwieldy political alliance endured long after Roosevelt’s death, supporting the Democratic Party and a “liberal” agenda for nearly half a century. Every president elected between 1932 and 1980 was a Democrat, with the exceptions of Dwight Eisenhower and Richard Nixon. The Democratic Party also controlled both houses of Congress for all but four of those 48 years. When the coalition finally cracked in 1980 , historians looked back on this extended epoch as reflecting a “New Deal order” with “an ideological character, a moral perspective, and a set of political relationships among policy elites, interest groups, and electoral constituencies.” 13

Battling the Great Depression

Before scholars could reflect on a New Deal “order,” there was what FDR and his contemporaries called simply the New Deal: the set of policies put in place during Roosevelt’s first two presidential terms in direct response to the ravages of the Great Depression. Most of that legislation came in one of two great bursts. The first followed Roosevelt’s inauguration on March 4, 1933 . 14 Within days of taking office, the new president called Congress into special session. By the time Congress adjourned precisely one hundred days later, Roosevelt had signed fifteen bills into law. Taken together, they restructured vast swaths of the American economy and authorized billions of dollars in federal spending for everything from dam construction and crop subsidies to unemployment relief. Roosevelt proposed—and Congress passed—so much legislation during this first “Hundred Days” that the time frame became a benchmark for all subsequent U.S. political leaders.

The second burst of legislation came in the first nine months of 1935 . The previous November, the president’s party had bucked historical trends by winning, rather than losing, seats in the midterm election. The victory was a landslide: When the new Congress convened in January 1935 , Democrats held two-thirds of the seats in both the House and the Senate. The election signaled the political realignment that created the New Deal coalition, and it gave Roosevelt a mandate. This second legislative burst enabled some of the best-remembered policies of the New Deal, including the Works Progress Administration, federal support for organized labor, and the Social Security program.

Contemporary journalists called these two torrents of legislation the First and Second New Deal, and historians have generally followed their lead. For decades, both scholars and popular writers argued that the two phases of the New Deal were ideologically distinct, although they often disagreed on the precise nature of that difference. 15 In recent years, historians have suggested that any ideological shift between 1933 and 1935 was exaggerated. Many have embraced the argument made by David Kennedy that New Deal policies were designed, above all, to provide security—security not only for “vulnerable individuals” but also for capitalists, consumers, workers, farmers, homeowners, bankers, and builders. “Job security, life-cycle security, financial security, market security—however it might be defined, achieving security was the leitmotif of virtually everything the New Deal attempted,” Kennedy writes. 16

Stabilizing the Financial System

The most urgent matter that Roosevelt confronted when he took office in March 1933 was the banking crisis. The nation’s banking system had been teetering on the edge of collapse since the end of 1930 as fearful domestic and foreign investors scrambled to pull their gold and currency deposits out of U.S. institutions. A new round of panic the month before the inauguration prompted governors in state after state to close their banks to prevent runs. On the morning FDR became president, such “bank holidays” had closed all banks in 32 states. In six more, the vast majority of banks were closed. In the remainder, depositors could withdraw only 5 percent of their funds. 17

Some politicians and political observers urged Roosevelt to nationalize the banking system. 18 Instead, the new president declared a national bank holiday, called Congress into emergency session, and persuaded them to pass the Emergency Banking Act. That act affirmed the temporary bank closure, authorized the Federal Reserve to issue more currency, and took other steps designed to restore the system’s liquidity. With banks set to reopen on March 13, Roosevelt took to the airwaves, delivering the first of the radio addresses that would become known as “fireside chats.” Using simple language and speaking in an authoritative yet avuncular voice, Roosevelt explained both the workings of the banking system and the steps that the federal government had just taken to preserve it. “I can assure you,” the president told his 60 million listeners, “that it is safer to keep your money in a reopened bank than under the mattress.” 19 Roosevelt’s combination of quick action and calming explanation worked. As his advisor Raymond Moley later wrote, “Capitalism was saved in eight days.” 20

New Deal efforts to shore up the banking system did not end with these emergency measures. A few months later, Congress passed the Glass-Steagall Act, which separated investment from commercial banking in an effort to insure that banks did not speculate with depositors’ savings. The act also established the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, which guaranteed bank deposits up to an initial level of $2,500. (That figure has been raised many times since.) Although FDR initially opposed deposit insurance, it almost immediately halted bank runs. These two moves dramatically stabilized the banking system. Even during the prosperous 1920s, more than six hundred U.S. banks had failed each year. In the early 1930s, that number climbed into the thousands. Beginning in 1934 , fewer than a hundred U.S. banks failed annually; by 1943 , the number had dropped to under ten. 21

Other New Deal financial measures were aimed at steadying the securities markets or strengthening the economy more generally. In the spring of 1933 , FDR followed Britain’s lead and took the United States off the gold standard, allowing the exchange value of the dollar to fall. One of the president’s advisors warned that the move would spell “the end of Western civilization,” but it gave New Dealers more flexibility to combat low prices by trying to stimulate inflation. Coupled with political instability in Europe, the end of the gold standard also prompted overseas investors to begin exchanging gold for dollars, further increasing the U.S. money supply and bolstering the banks. 22 The Securities Act of 1933 sought to end insider trading in the stock market by requiring publically traded companies to disclose financial information. The following year, Congress created the Securities and Exchange Commission to guard against market manipulation. Finally, the Banking Act of 1935 put the Federal Reserve’s Open Market Committee—the body that influenced the nation’s money supply and thus the availability of credit—under the direct control of a Board of Governors appointed by the president. This move helped centralize the nation’s banking system, and improved the Federal Reserve’s ability to shape the business cycle.

Relief for the Unemployed

Having stabilized the banking system, FDR turned quickly to the problem of unemployment relief. In the spring of 1933 , some 12.4 million men and 400,000 women—roughly one-quarter of the national workforce—were unemployed. Most were their families’ principal breadwinners. 23 The collective need of these American families had already overwhelmed the resources of local governments and private charities, as well as family and community support networks. With millions unable to pay rent or buy food, men, women, and children lined up at soup kitchens, grubbed for scraps in garbage cans, hopped freight trains, or moved into makeshift shantytowns that sprang up in parks and open spaces on the edges of American cities.

FDR first focused on the problem posed by young men—a problem captured in a 1933 film entitled The Wild Boys of the Road . Teenagers and men in their twenties had fewer skills and less experience than their older counterparts; thus, they were more likely to be unemployed, to leave home, and to become hobos and vagrants. Events in Europe suggested the threat that such footloose young men might pose to the social order. Roosevelt believed that sending them to work in the countryside would not only improve the nation’s rural infrastructure but also transform the young men into upstanding future citizens. He proposed a Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) to employ those between the ages of 18 and 35 on a variety of forestry, flood control, and beautification projects. To be selected for the program, men had to be single, healthy, and U.S. citizens and to come from families on relief. Living in military-style camps operated by the War Department, they built roads, firebreaks, trails, and campgrounds. They also planted trees, fought fires, and drained swamps. CCC workers served stints of less than two years and were required to send home $25 of the $30 they earned each month to their families. Between the program’s establishment in 1933 and its expiration nine years later, the CCC put three million young men to work. It quickly became one of the New Deal’s most popular initiatives, and remained popular even in conservative areas. 24

Although the CCC kept many young men from taking to the road, it was hardly enough to relieve the distress of American families. Thus, Roosevelt urged establishment of a new agency, the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA). He persuaded Congress to appropriate $500 million to FERA, and used it to provide direct relief to needy Americans who were able to pass a means test. Some FERA funds were funneled through the states. Others were passed out by Harry Hopkins, the former social worker whom FDR tapped to run the agency. Hopkins had held a similar position in New York State when Roosevelt was governor there. Both men felt great sympathy for the poor, and both also knew how to use FERA to political advantage. By enlarging the federal role in awarding relief, they helped to transfer the political allegiance of America’s unemployed from local officials and political machines to Washington, D.C.

FERA made life marginally easier for many, but it never had sufficient funds. As the United States headed into the fifth winter of the Depression, unemployment remained high. In November 1933 , Hopkins persuaded Roosevelt to establish yet another agency to employ people directly. Drawing tools and materials from army warehouses, the Civil Works Administration (CWA) put Americans to work fixing roads, docks, and schools; laying sewer pipe; and installing outhouses for farm families. The CWA paid far more than FERA and did not subject all workers to a means test; it was soon employing more than 4 million men and women. By February 1934 , the CCC, FERA, and CWA together were reaching 22 percent of the U.S. population, an all-time high for public welfare in the United States. The president, however, worried both about the escalating costs of such programs and about relief becoming “a habit with the country.” He ordered the CWA to close down at the end of March, noting that nobody would starve when the weather was warm. 25

Americans made it through the rest of 1934 , but as the new Congress convened in early 1935 , the unemployment rate still hovered near 20 percent. Moreover, some 5 million Americans remained on relief. FDR and many of his advisors continued to worry about deficit spending, but they also believed that something had to be done and that only the federal government had “sufficient power and credit” to do it. Work relief cost more than direct payments, but the latter, as FDR declared in his annual message to Congress, was “a narcotic.” “The lessons of history, confirmed by the evidence immediately before me,” he added, “show conclusively that continued dependence upon relief induces a spiritual and moral disintegration fundamentally destructive to the national fibre.” FDR proposed a massive public employment program to get 3.5 million abled-bodied but jobless Americans off the relief rolls. 26

The result was the Works Progress Administration (WPA), one of the most ambitious and best-remembered New Deal programs. Headed by Hopkins, the WPA put more than 3 million people to work in its first year. Roosevelt wanted all projects to be labor intensive and useful, and when possible to come to a natural end. He also wanted WPA to pay more than relief but less than market rates so as not to compete with private enterprise. WPA workers built highways, schools, airports, parks, and bridges. They bound books, supervised recreation areas, ran school lunch programs, and sewed garments for the needy. WPA workers even entered the arena of public health, building hospitals and clinics, conducting mass immunization campaigns, and churning out posters that promoted nutrition and warned against the dangers of tuberculosis and syphilis.

Many of those posters were produced by employees of the Federal Arts Project, part of a massive and unprecedented federal venture into the arena of culture. Both Hopkins and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt believed that the New Deal should provide work for unemployed artists, musicians, actors, and writers, and so the WPA set up a series of cultural programs known collectively as “Federal One.” The Federal Writers’ Project produced dozens of state and city guidebooks, and conducted thousands of oral histories with former slaves, immigrants, stonecutters, packinghouse workers, Oklahoma pioneers, and others. It also sent folklorists to record the music and stories of Appalachian banjo pickers, southern bluesmen, Mexican American balladeers, and Okies in resettlement camps in the West. The Federal Music Project sponsored symphony orchestras and jazz groups, while the Federal Arts Project commissioned muralists and graphic artists. Both hired individuals to teach music, painting, and sculpture to schoolchildren.

If New Dealers wanted to aid unemployed artists, they also hoped to democratize culture and to generate support for New Deal programs and political values. No New Deal initiative better illustrates this goal—or the controversy it generated—than the Federal Theatre Project, which brought plays, vaudeville acts, and puppet shows to small towns across the country. It also staged controversial shows like Orson Welles’s production of Macbeth , which featured an all-black cast. Finally, the Federal Theatre Project developed a new theatrical genre, the Living Newspaper, to dramatize current events and expose social issues. One Living Newspaper, Power , traced the development of the electrical power industry and urged greater support for public ownership of utilities. Other Living Newspapers dealt with agricultural policy, the shortage of affordable housing, the labor movement, and syphilis.

Not surprisingly, Federal One drew intense criticism from critics on the right: In June 1939 , a more conservative Congress dissolved the Federal Theatre Project, charging that it spread New Deal propaganda and encouraged racial mixing in stage productions. Budget cuts to the other cultural programs soon followed. Conservatives warned that all WPA programs were endangering the American way of life by providing jobs for the undeserving. They also complained that the WPA was simply a Democratic Party patronage machine. (FDR did use the program to reward local power brokers who supported the New Deal, although these included progressive Republicans like New York City’s Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, as well as Democratic political bosses in cities like Chicago and Memphis.) 27

Not all criticism of the WPA came from the right. Leftist critics noted that the WPA was chronically underfunded; despite its size, it could provide jobs for only a third of those who needed them in the United States. 28 To avoid competing with the private sector, WPA jobs always paid less than the “prevailing wage” in a given community. Since that standard differed by region, gender, and race, it reinforced existing patterns of discrimination. The editors of The Nation complained that the program required workers to toil “at depressed wages in a federal work gang” and was “a morbid substitute for relief.” 29 Nevertheless, between 1935 and its dismantling in 1943 , the WPA employed some 8.5 million Americans, roughly one-fifth of the nation’s workforce, at a total cost of roughly $11 billion. Many were grateful to have a job rather than a handout. “We aren’t on relief anymore,” the wife of one WPA worker reportedly said. “My husband is working for the Government.” 30

Aiding Farmers

Both the crisis in the banking system and the spike in unemployment were problems brought on by the Great Depression. The plight of America’s farmers had deeper roots, however. Rural America had been mired in depression since shortly after the end of World War I, a situation that farmers found particularly vexing given the general economic prosperity of the 1920s. 31 The deflationary spiral of the early 1930s pushed farm income down an additional 60 percent. 32 Across the country, crops rotted in the field because prices were so low that farmers could not justify harvesting them. Western ranchers slit the throats of livestock they could afford neither to feed nor to market. Dairymen in upstate New York dumped milk into ditches, while growers in California lit mountains of oranges on fire. 33 Since taxes and mortgage payments did not fall, farmers across the country lost homes, land, and equipment to foreclosure. Many rebelled, joining “farm strikes,” disrupting auctions, and nearly lynching an Iowa judge who refused to suspend foreclosure proceedings.

New Dealers believed that boosting farm incomes would help not only rural Americans but also the entire U.S. economy. In 1933 , farmers still made up roughly one-third of the nation’s workforce, and their purchasing power dramatically lagged that of residents in urban areas. By restoring prosperity to the farm economy, New Dealers argued, they would increase farmers’ ability to buy nonfarm goods, in turn contributing to a more general economic recovery. Such reasoning reflected not only the thought of many in the Roosevelt administration regarding the economy, but also their tendency to romanticize the nation’s pastoral past and their awareness of the continuing political power of rural America. 34

The centerpiece of the New Deal’s efforts to raise farm incomes was the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA), passed in May 1933 . The act charged the federal government with raising the price for key farm commodities in order to bring the prices that farmers received for their products into balance or “parity” with their production and living costs. It pointed to the years just before World War I as the ideal of parity. While the act was vague about the exact mechanism the government should use to achieve this end, it established a new agency and sanctioned a variety of remedies that farm advocates had been battling over for years. To prevent farmers from planting surplus crops, the AAA levied a tax on flour millers and other crop processors and used the proceeds to pay farmers for taking land out of production. At the same time, the agency tried to maintain a floor under prices by keeping harvested crops off the market when prices were low. It did this by offering farmers loans secured by their crops at above-market rates, then storing the surplus. If crop prices rose, farmers could repay the loans, redeem their crops, and sell at the higher prices. Finally, the act established a Farm Credit Administration (FCA) to provide mortgage relief to farmers.

From the beginning, the New Deal’s farm policy proved controversial. Cotton and wheat farmers had already planted their crops by the time the farm bill passed. A severe drought on the plains constrained the wheat supply naturally, but AAA officials paid farmers to plow up 10 million acres of cotton. The agency also bought and slaughtered some 6 million piglets and 200,000 sows to prevent a future glut of hogs. 35 While much of this pork eventually fed hungry people, the destruction of crops and livestock angered many Americans. When journalist Lorena Hickok went on a fact-finding tour for the administration in the fall of 1933 , people in Minnesota and Nebraska complained to her about the New Dealers’ methods. 36 “As long as there are 25 million hungry people in this country, there’s no overproduction,” one Iowa farm leader declared. “For the government to destroy food and reduce crops at such a time is wicked.” 37

Considered in the aggregate, rural America benefited from New Deal farm policies. Within 18 months of its establishment, the FCA had refinanced one-fifth of all farm mortgages. 38 Prices for crops like corn, wheat, and cotton surged, and net farm income rose by 50 percent between 1932 and 1936 . 39 Yet these benefits were not evenly distributed, and AAA policies often exacerbated the plight of tenant farmers and sharecroppers. New Deal officials relied heavily on county-level committees to set production quotas, monitor acreage-reduction contracts, and dispense federal payments. Agricultural Secretary Henry Wallace considered this decentralized approach to be “economic democracy in action,” but local committees were often dominated by the largest growers. 40 Large planters and landowners frequently pocketed checks for keeping acreage fallow, then pushed out the tenants and sharecroppers who were actually farming the land. In the South, many of these sharecroppers were African Americans, and so they bore the brunt of such policies. In California, where “factory farms” used migratory laborers, growers rarely restored wages to pre-Depression levels, even after prosperity returned. Tenants, sharecroppers, and farmworkers sometimes fought back—joining groups like the Southern Tenant Farmers Union and the Cannery and Agricultural Workers Industrial Union—but such efforts often provoked violent reprisals. Liberals within the Department of Agriculture who pleaded the case of the disempowered were purged. 41

Although the Roosevelt administration did little to keep tenants and sharecroppers on their land, it did establish two agencies ostensibly designed to give impoverished farmers a fresh start. The Resettlement Administration (RA), set up in 1935 , built three “greenbelt” towns, which were close to big cities and surrounded by countryside. In 1937 , it was absorbed into a new agency, the Farm Security Administration (FSA), which established a chain of migrant labor camps and granted low-interest loans to enable some tenants to buy farms. Both agencies, however, faced opposition from farm corporations and southern landlords who wanted to keep their cheap labor. The RA had hoped to move half a million farm families, but ultimately resettled fewer than 5,000. 42 Photographers hired by the FSA to document America and build support for New Deal programs provided many of the most iconic pictures of the Great Depression, and the agency’s migrant camps came to public attention when John Steinbeck depicted one in his epic novel The Grapes of Wrath in 1939 . Nevertheless, the FSA’s congressional opponents kept its appropriations low, limiting its ability to make a real dent in rural poverty.

Conservation and Regional Change

As FSA photographs and books like The Grapes of Wrath attested, the problems plaguing rural America were not limited to low commodity prices. Across the nation, uncontrolled lumbering had scarred and depleted forests, while intensive farming had ravaged the land. Meanwhile, droughts, wind, and floods depleted the soil. A massive flood on the Mississippi River in 1927 inundated thousands of square miles and displaced some 700,000 people. 43 A single dust storm on the Great Plains in May 1934 sucked 350 million tons of topsoil into the air and deposited it as fair east as New York City and Boston. 44 New Dealers believed that only by developing more sustainable agriculture—and by distributing natural resources more equitably—could the living standards of Americans in rural areas be brought up to the same level as those of their urban counterparts.

To achieve this, New Dealers undertook a variety of initiatives. They retired land, sought to restore forests and soil, engaged in flood control and irrigation projects, and produced cheap hydropower to fuel farms and new industries. Historian Sarah Phillips has suggested that these projects reflected a “New Conservation,” focused less on the preservation of wild areas or the efficient use of natural resources than on the welfare of rural residents. 45 Since the South and West were the most rural parts of the nation, those regions benefited disproportionately. In fact, New Deal land use and energy policies contributed to the emergence of what would eventually become known as the “Sunbelt.” 46

The first, most ambitious, and ultimately most successful of these New Deal projects was the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), established by Roosevelt during his first Hundred Days. Cutting across seven states in one of the most impoverished parts of the nation, the TVA brought economic progress and hope to a region that had seen little of either since the end of the Civil War. In addition to most of Tennessee, the TVA covered swaths of Kentucky, Mississippi, Alabama, Virginia, North Carolina, and Georgia. TVA dams prevented spring floods from displacing residents and washing away topsoil. They also provided ample cheap electricity, which the agency sold to rural co-ops and municipal power systems. TVA experts developed fertilizer, built model towns, upgraded schools and health facilities, planted trees, and restored fish and wildlife habitats. In 1933 , 2 percent of farms in this region had electricity; by 1945 , 75 percent were electrified. Cheap electricity also attracted new industries to the region, including such corporate behemoths as Monsanto and the Aluminum Company of America (ALCOA). 47 Through its generation of power, not only did the TVA help to modernize the upper South, but it also inserted the federal government more fully and permanently into the private economy than did any other New Deal agency.

The success of the TVA prompted New Dealers to dive more fully into rural electrification. Private power companies had long argued that they could not afford to provide electricity to isolated farms and small, rural communities. As a result, many Americans were still living without the benefits of running water, indoor toilets, lights, refrigeration, or labor-saving devices. In 1935 , over the protests of private utilities, New Dealers convinced Congress to establish the Rural Electrification Administration (REA), a move that profoundly changed rural lives. The REA sponsored the creation of hundreds of nonprofit electric cooperatives and offered them low-cost loans for generating plants and power lines. In the early 1930s, fewer than one in ten American farms had electricity. By 1941 , the number had risen to four in ten. By 1950 , 90 percent of U.S. farms were electrified. 48

Industrial Policy

If rural electrification was one of the New Deal’s greatest successes, industrial policy was one of its biggest failures. When FDR took office, both he and his advisors were convinced that the economy needed a major stimulus, but few agreed on what form that should take. Some businessmen and New Dealers considered the Depression the result of destructive competition. They argued for suspending antitrust laws and forging industry-wide agreements that would allow businesses to stabilize prices, end overproduction, and ultimately raise wages. Others, more distrustful of the business community, argued either for stimulating competition or for engaging in national economic planning. Many advocated federal spending on public-works projects to “prime” the economic pump; yet the president and most around him still hoped to avoid running federal deficits. This policy discord prevented FDR from taking any action until near the end of his first Hundred Days. When the Senate passed a work-sharing bill that the president opposed, he ordered staffers who favored differing plans to shut themselves in a room and develop a compromise. 49

The resulting bill, which Roosevelt proposed in May 1933 , contained what one of his advisors later called “a thorough hodge-podge of provisions.” 50 Declaring a state of industrial emergency, it largely suspended antitrust laws and created the National Recovery Administration (NRA) to oversee the development of codes to regulate prices, wages, hours, and working conditions for hundreds of industries. Section 7a of the bill gave industrial workers the right “to organize and bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing,” marking a historic reversal of the federal government’s traditional refusal to back unionization. Finally, the bill appropriated $3.3 billion to be spent by a new Public Works Administration (PWA). New Dealers hoped that the public works spending would jump-start the economy, buying time for the industrial codes to take effect.

This unwieldy industrial policy foundered from the start. Interior Secretary Harold Ickes, who had been charged with overseeing the PWA, moved with great caution in order to avoid accusations of misusing funds. In the agency’s first six months, he spent only $110 million of the billions allocated. 51 As a result, the PWA failed to provide any short-term economic stimulus. The cotton textile millers quickly drafted an industrial code, but other industries were slow to follow. Hugh Johnson, the colorful former general appointed to head the NRA, tried to compensate for this sluggish pace by resorting to the tactics of propaganda and community pressure that had been used successfully by the United States during World War I. Employers who agreed to sign a blanket wage-and-hour code were allowed to display NRA signs picturing a stylized Blue Eagle and the slogan “We Do Our Part.” The NRA’s Blue Eagle soon landed in store windows and on delivery trucks, and cities across the nation held “Blue Eagle” rallies and parades. This campaign made the NRA one of the most recognized aspects of the New Deal, but it did little to boost employment or improve incomes.

The code-writing process slowly moved forward. Although Johnson and the NRA had been given formal authority over the enterprise, they had no means to enforce compliance. Thus, the largest producers in each industry tended to dominate the proceedings. Mechanisms to fix prices and control production often hurt smaller operators. Code-making panels were supposed to include labor and consumer representatives, but they rarely did. As a result, price rises tended to outpace wage increases. The law eventually produced so many overlapping industrial codes—more than five hundred—that even businessmen complained about NRA bureaucracy. 52 In October 1934 , FDR finally secured Johnson’s resignation. The following May a unanimous Supreme Court declared the NRA unconstitutional.

Although slow to get started, the PWA ultimately proved more successful. In contrast to other jobs programs launched by the New Deal, the PWA embodied a “trickle-down” approach. The agency paid higher wages than did other work-relief projects, hired more skilled workers, and drew fewer employees from relief rolls. By focusing on large-scale construction projects, Ickes hoped to stimulate industries that provided materials and components, thus creating jobs indirectly. Between 1933 and 1939 , PWA workers built schools, courthouses, city halls, hospitals, and sewage plants. They built the port of Brownsville, Texas; the LaGuardia and Los Angeles Airports; two aircraft carriers; and numerous cruisers, destroyers, gunboats, and planes. The PWA constructed New York City’s Lincoln Tunnel, Virginia’s Skyline Drive, the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge, the Bonneville and Grand Coulee dams in the Pacific Northwest, and the highway that links Key West to the Florida mainland. Surveying this legacy, one scholar compared Ickes to the Egyptian pharaoh who oversaw construction of the Great Pyramid of Giza. 53

Crafting Social Security

The PWA and the WPA both provided jobs for able-bodied Americans. They did little, however, for the sick, the disabled, or the elderly—those whom one sympathetic House member called “America’s untouchables.” 54 Few workers had pensions, and so most worked as long as they were able. Those considered unemployable because of age or health were forced to rely on their families or on local welfare agencies. To help these citizens, to ensure that the elderly did not take jobs away from younger compatriots, and to give all Americans the promise of future “security,” the president proposed a sweeping program of unemployment and old-age insurance. The Social Security Act, which FDR signed into law in August 1935 , laid the foundation for the U.S. welfare state, reshaping the lives and futures of Americans for generations to come. One Roosevelt biographer called it “the most important single piece of social legislation in all American history, if importance be measured in terms of … direct influence upon the lives of individual Americans.” 55