How autism-friendly architecture can change autistic children’s lives

Senior Lecturer in Interior Architecture, Leeds Beckett University

Disclosure statement

Joan Scott Love does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Leeds Beckett University provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

Imagine wearing a hearing aid on its highest setting and being unable to make any adjustment. You can hear the speech of the person next to you – but, at the same volume, you hear birdsong through an open window, the air conditioning whirring above and the traffic droning outside. The difference in the layers of sound cannot be filtered and a cacophony results. Combine this with some of your senses being crossed or scrambled, rather like a poor telephone connection, and you start to appreciate how some people on the autistic spectrum encounter the world . It is small wonder that productive teaching of an autistic child presents a challenge.

Within our living spaces, all of us are bombarded with an array of stimulating sensory inputs – sound, smell, touch, taste, movement – and a never-ending deluge of visual information. Many people manage to filter and cope, but people with autism encounter the world differently. Sensory difficulties can cause hyper-sensitivity (sense too much) or hypo-sensitivity (sense too little), or combinations of both . The environment becomes a confusing place when attempting to process “ too much information ”. Unexpected changes cause anxieties, which are challenging to manage, and the level of stimuli can tip the balance, to cause sensory overload, sometimes misinterpreted as a tantrum.

An optimised learning environment is vital for every child. For autistic children, the importance of environment is magnified, as are the benefits that can be achieved through appropriate architecture and design.

Over the past five years, I’ve been conducting research into how to teach the design of autism environments to future designers, with eight case study schools and colleges. The research has identified a number of ways schools can adjust spaces to help children and young people with autism cope with their surroundings and, therefore, learn more effectively.

How schools can help

In particular, the recommendations take into account the value to autistic people of preparation before an activity as this allows information to be processed at an individual’s required rate. This gives children time to understand what is expected of them. It also reduces anxieties, provides reassurance and enhances learning receptivity.

1. Provide pause places

Make the most of any open alcoves or recesses. Clear any small spaces “under the stairs” or in an outside area, providing an opportunity to stand back, process information and recalibrate. It could mean removing a door from a shallow cupboard or locating a “pop up” tent. This is particularly important when moving from one building to another – when the difference between environments is significant.

2. Multiple entrances help

A main entrance may be too busy, so provide a quieter, alternative side entrance. Schools can also help by establishing a slow longer route from the playground to classrooms, as well as a quick short route – again giving both choice and time to process information.

Equally, softening the boundary from an internal to an external space can also help. An external canopy, for example, can create an ideal outdoor learning space to help with anxieties surrounding sudden sensory change.

3. Windows can offer reassurance

Some children have anxiety and ritualistic behaviours, and may want to spend time returning to a space they have just occupied, for reassurance. If strategically placed openings are provided, they do not need to go back physically to this space for reassurance, they can look back from a short distance. This allows more time for learning in the classroom.

4. Join the dots

Schools should also look at offering activities that emulate real life tasks, as this will help autistic children to see patterns and connections with things. A simple mock up shop, for example, both inside the classroom, and outside in the playground, could help children to learn how to generalise the skill of exchanging payment for goods, across differing environments.

A richer learning experience

What are known as “taster spaces” are also a great idea, as these can offer children an area to spent time participating in a pre-activity which helps them to explore part of a bigger activity in a smaller way.

This can help children to build up to the final activity – such as playing a percussion wall, before playing an instrument, or relating to a water channel before immersion in a pool.

As these ideas show, the need to encourage a richer learning experience, in a regulated responsive environment , is paramount for autistic children and young people. An essential consideration is that no two autistic people experience their environments in the same way, so there is no one approach or solution to sensory issues. But small, individually led adjustments (like those outlined above) can make a material difference, and really help to improve learning and quality of life of autistic children and their families.

- Architecture

- Autistic children

- Autism research

Events and Communications Coordinator

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

- Architecture

- Interior Design

- Master Planning + Urban Design

- Engineering

- Resiliency + Sustainable Design

- National Accounts

- Facility Information Solutions

- Workplace Strategy

- Baltimore, MD

- Bangalore, India

- Dallas / Ft. Worth, TX

- Minneapolis, MN

- Phoenix, AZ

- Rochester, MN

- Seattle, WA

Autism-aware design

By Thomas Denhardt, ArchitectureNow Jul 2017

Autism Spectrum Disorder (or ASD) is a misunderstood condition that affects an estimated 1 in 66 people, approximately 65,000 New Zealanders, yet it is absent in our accessibility codes. So how can architects and designers significantly improve the lives of those who are diagnosed with ASD? Thomas Denhardt talks with experts in the field.

In 1973, Louis Kahn was engaged to design Four Freedoms Park, a memorial that commemorates President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s life and his seminal Four Freedoms speech. Ironically, the sunken terrace incorporated into the design inhibited Roosevelt from the freedom to enjoy the memorial, since it is not wheelchair accessible. In Kahn’s defence, this was before the advent of the American Disabilities Act 1990. Some would say ignorance is bliss.

Since those times, accessibility has been amalgamated into new public proposals by architects, with the local Building Act stipulating NZS 4121 Access and Mobility – Buildings and Associated Facilities as a suitable standard. This egalitarian movement, driven by legislation, has given those with a disability an equal opportunity to participate and conduct their business independently within our built environment.

But what can architects do to contribute to the physical independence and inclusion of those who live with ASD? Ambiguous to many, misinterpreted by some and absent in accessibility codes, architects and designers can, through design, play a remarkably positive, influential hand in the lives of those who live with ASD. Exploring suitable design guidelines and examining a prime architectural case study that is considerate of ASD occupants will help to answer this question, with the potential of expanding further what is meant by architecture that is accessible for all. But firstly – what exactly is ASD?

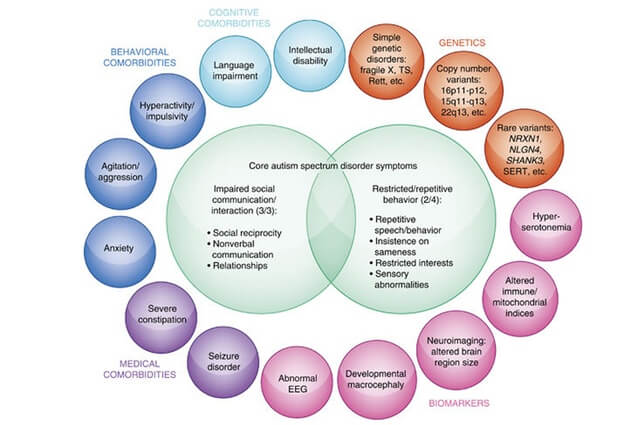

Dr Javier Virués-Ortega , a New Zealand-registered clinical psychologist and director of Applied Behavioural Therapy at the University of Auckland, defines ASD. He describes classic symptoms that differ from those of people who are neurotypical (without ASD), and suggests where architecture can make a considerable difference. In its purest form, ASD is “a collection of dimensions that are highly variable across individuals,” states Virués-Ortega. These dimensions can be characterised as excesses and deficits.

Using human behaviour as an example, “a behavioural excess is something that a person with ASD is doing more often than a person without the diagnosis,” he adds, such as having a close affinity to numbers or arranging items in a particular order. On the other hand, “a behavioural deficit is something that the person is doing less often than expected,” such as avoiding social interactions and physical contact with others.

Briefly, the classic symptoms of those with ASD can be clustered around three constituents: impaired social interaction, impaired communication and restricted behaviour. Impaired social interaction is “a lack of social referencing, where the ability to interpret gestural cues provided by a peer or caregiver is not fully developed,” explains Virués-Ortega. Impaired communication can be quite diverse, with individuals of low-functioning autism often failing to develop spoken language whereas others display a limited verbal repertoire comprised of non-functional repetitive words or phrases (echolalia).

Lastly, and most substantially to architects, is the classic symptom of restricted behaviour. This is where individuals exhibit repetitive, stereotypic or ritualistic patterns of behaviour, which can be very diverse and classified as highly idiosyncratic. For example, a middle-aged man may be a serial organiser and insist on having things in a certain way, including being highly susceptible to outside noises.

Sensory processing problems – such as auditory issues established in the example above (including tactile, olfactory and visual dysfunction), agoraphobia and difficulty transitioning through spaces or changing routines – are some of the key challenges faced by individuals with ASD who have restricted behaviour.

These challenges are the primary focus for architects and designers to consider when designing private and public environments, such as multi-storeyed city apartments and local shopping malls. “This is the space in which design and architecture can make a significant difference,” Virués-Ortega suggests, since the way we design our built environment can heighten or lessen these challenges for ASD individuals, thus heightening or lessening the likelihood of their challenging behaviours.

This ‘significant difference’ that architectural design can conduce for those with ASD can be perceived as a foreign concept to most practitioners – esoteric, even. Dr Magda Mostafa, a special needs design associate and architect at Progressive Architects, as well as the associate chair of the Department of Architecture at the American University in Cairo, explains her groundbreaking Autism ASPECTSS Design Index, which establishes how implementing autism-aware design can be beneficial to all.

Trademarked in 2013 and developed over a decade of research, the index is “a framework made up of seven criteria, which form the acronym ASPECTSS: acoustics, spatial sequencing, escape space, compartmentalisation, transition space, sensory zoning and safety,” Dr Mostafa states. This index is non-prescriptive, unlike other accessibility codes, providing a spectrum of solutions that are applicable and helpful to all users on the spectrum. Being aware of the sensory input you are creating through your design decisions is strongly advocated in the ASPECTSS index, thus making the designer or architect mindful of the impact that input will have on the end users with ASD.

When applying ASPECTSS, one of the core facilitative concepts must be allowing for flexibility, growth and response to the development of skill and adaptation of its users, since individuals can have a diversity of needs, profiles and challenges. With this in mind, Dr Mostafa explains in more detail two of the seven criteria – acoustics and escape space.

Acoustics or auditory sensitivities are an acute challenge for many autistic individuals. However, implementing complete sound-proofing and full acoustical control is considered “counter-productive for the school or at home,” Dr Mostafa explains. This is due to the risk of the individual’s behaviour becoming accustomed to the environment, “only to have the individual unable to generalise that skill outside of this perfect space”. It is called ‘the greenhouse effect’ and is not sustainable in achieving the long-term objective of inclusion and independence. What is more effective in this regard is the implementation of acoustical management, where different levels of control provide for different levels of sensitivities for the users on the spectrum.

For instance, when Dr Mostafa consults (for schools, in particular), she suggests the “use of graduated acoustical control, where more controlled acoustics are applied to ‘low stimulus’ zones – such as libraries, and speech and language therapy rooms – especially for more sensitive users such as minors, who have not yet developed sensory management and integration skills.” This methodology allows children to develop skill and then graduate towards less acoustical control, as acoustic sensitivities becomes less obtrusive, especially with age.

On the other hand, escape space, unlike acoustics, is a principle that is readily applicable universally and capable of being implemented to different degrees in its own spectrum of manifestations. “These can range from a visually, acoustically and spatially separate space, like a small quiet room or a quiet bench under a tree in the garden of a school, to a simple quiet chair in a nook of a break room at an office, or a reading carrel in a library at a school,” Dr Mostafa says.

These escape spaces have the ability in creating an opportunity to remove oneself from experiences that are distracting and over-stimulating, or whenever a need to ‘re-adjust’, decompress and regain self-control arises. Dr Mostafa applied this principle recently for a group in the United States, where “one of the first recommendations I shared with them – particularly for those with existing premises and limited means to retrofit – was to provide the means for an escape space,” since it does not encumber the design or complicate the process while achieving the aim of inclusivity for those with ASD.

Furthermore, employing autism-aware design in architecture goes beyond the call of duty for those with ASD by being beneficial to those who are neurotypicals also. This is supported through Dr Mostafa’s research, where, in one case study, teachers as well as students gained indirectly from an improved acoustical environment. This is because “students focused better in a less stimulating environment, thus performing better academically, so teachers performed their jobs better, and so on, in a cycle of improvement”.

The same result was found for escape spaces, where everyone occasionally needs a moment of escape or a ‘sensory break’ from clockwork, with the provision of space to do so allowing for this management. From this, Dr Mostafa believes autism-aware design is helpful to the entire spectrum of human perception “provided flexibility is taken into consideration”.

CASE STUDY 1: FIRST PLACE APARTMENTS

This concept of helpfulness that promotes physical independence is a ringing theme in the autism design world, since ASD individuals (specifically adults) transitioning from their secure family homes into greater society can be quite a challenging, even daunting, prospect.

Mike Duffy, associate and project design architect for RSP Architects in the US, discussed his benchmark proposal for clients, ‘First Place AZ’, which aids this transitioning process and the development of independence through architectural design, shedding light on lessons that were learnt in the process. First Place AZ is an independent not-for-profit organisation for individuals with autism and other neuro-diversities, which engaged RSP Architects to develop their exciting novel vision to fulfil the needs of those with ASD. Situated in Phoenix, the proposal comprises three major components:

- First Place Apartments – 56 studio, one, two and four-bedroomed units for lease, with independent living services and amenities;

- First Place Transition Academy operated by the Southwest Autism Research & Resource Center (SARRC), where 32 students, who are transitioning to more independent living, will experience paid internships and engage in volunteer activities each year, exposing them to different types of jobs while building their skills and resumés (with 16 residing in four four-bedroomed suites at First Place in year one of the two-year programme, and 16 living off-campus in year two);

- The First Place Leadership Institute is focused on continued education and training of support service providers, professionals and physicians, including a hub for research and public policy advancements.

The First Place Apartments are housed from the ground floor through to level four, while the First Place Leadership Institute and Transition Academy is organised around a central courtyard on the ground floor that provides security and facilitates various functions, including a community garden and pool amenities.

These components are the building blocks for the First Place mission, yet it is the intermittent spaces that are considered the glue that holds the bigger pieces together. Duffy explains this further, making reference to Kintsugi: “Kintsugi is the Japanese art of ‘golden repair’, where broken pieces of pottery are mended using resins made from precious metals, such as gold or silver. That which holds it together becomes more important, more special than the pieces it is holding together, with the circulation spaces at First Place Phoenix being treated as the golden resin.

This approach to design unifies the building programme, while creating a venue for social connections and networks that will form the support systems that make independence possible; this is considered vital to a successful transition to independent living. “Spontaneous conversations after classes, interaction with fellow neighbours, even individuals getting together to learn new culinary skills or enjoy a movie” are the types of unpredictable behaviour fostered in these circulation spaces, explains Duffy. Visible externally via yellow/gold metal panels, their symbolic importance is highlighted.

Internally, a plethora of measures are applied to achieve a hospitable environment that is considerate towards ASD individuals. “A refined and repeated material palette is strategically placed throughout to increase familiarity with spaces, with subtly coloured visual paths and signage employed to assist individuals in transitioning through spaces,” Duffy says. Designers in this regard are recommended to specify more muted colours like light blues, greens, tans, greys, even lavender, which promote calmness, rather than bright punchy colours that can overwhelm and exacerbate hypersensitivities.

Increased durability in materials is another measure applied throughout, including “acoustic baffles and inset entries for each apartment, which limits noise transfer”. Diffused LED lighting, which is less harsh, and ample natural lighting with strategically placed windows and doors provide comfort and illumination throughout the design, with operable windows providing the auxiliary benefit of controlled access to fresh air and passive ventilation.

In terms of safety and security, “a single point of entry with 24-hour ‘concierge’ services is provided,” Duffy says, with individuals having different locking options available to apartments to promote greater independence. Lastly, natural materials that are chemical free or have low toxicity levels (no VOCs) were also considered when specifying paints, sealants, plastics, adhesives and carpets.

Engaging with First Place AZ and their mission to support those with ASD has allowed RSP Architects to reach new meanings in the work they do, finding that “designing for those with ASD is not that different from designing for those without ASD”, but rather analogous. Every sensitivity on the autism spectrum has not been directly addressed Duffy confirmed, but through collective “discussions, dialogues and design charrettes, we’ve decided as a team what would be best to implement for First Place Phoenix given its mission”.

This process also influenced their response in implementing a more “neurotypical approach to design measures throughout”, knowing that someone’s next place may not have the same sensory sensitive design and approach. Individuals with ASD will “learn, grow, thrive and succeed” at First Place AZ, which has led to the autism community becoming beneficiaries of new knowledge, creativity and, most profoundly, as illustrated here, greater future independence.

It is commonly accepted today that, through architecture, architects and designers have a professional responsibility to envision and portray building design that is considerate of its users and inclusive of our diverse society. This responsibility includes ASD individuals. Characterised as excesses and deficits, ASD can be aggravated or lessened through our planning and design decisions, with numerous instruments available that work with the challenges of ASD individuals, not against them.

When researched and considered carefully, autism-aware design has the ability to transform architecture into a public message that redefines what accessible design means, which is demonstrated by Dr Magda Mostafa Autism ASPECTSS™ Design Index and First Place AZ’s audacious objective of physical independence.

We do not expect to live and work in leaky or unhealthy buildings, so we should not expect ASD individuals to live and work in buildings that hinder their independence or do not provide the capacity for them to fulfil their everyday needs. Architects and designers do not need to train nor recruit autism followers who paint the city in a coat of autism-alertness. Instead, they simply need to know what autism-aware design is and, in doing so, they will be consciously designing with everyone in mind.

So, rather than repeat history in the name of Louis Kahn, next time, when the project requires accessible means, ask yourself the question: where is the autism-aware design?

CASE STUDY 2: ‘THE MISSING LINK – DESIGNING FOR OPTIMAL HEALTH’; THESIS BY KAREN GOEDEKE

Last year, Karen Goedeke , a master’s student at the University of Auckland’s School of Architecture & Planning, completed her thesis research on the architecture of learning environments for children with ASD. Architecture New Zealand interviewed Goedeke about her investigations.

What made you interested in design for children with ASD? My interest in designing for ASD came from my passion for health and a growing awareness about environmental toxicity. With an undeniable relationship between the human body and its environment, society is getting sicker and our built environment is largely to blame. ASD gives clear symptoms that I could relay this knowledge back to, finding solutions to ease the overload of a surrounding building. My thesis presents a journey towards a symbiotic relationship between behaviour, environment and architecture, creating a school that stimulates those fleeting moments of calm where children can communicate, respond, learn and interact, and have them last a little bit longer.

Why is it important for architects to understand ASD? On the cusp of a demographic boom, it’s important for architects to truly understand the experience of those who are most sensitive to their surroundings. Rising levels of autism in children brings social anxiety, isolation and difficulty integrating into normal schooling situations. The built environment can be overwhelming, alienating and difficult to negotiate. The sooner architects understand and implement a change in the spaces around us, the best chance we have to protect developing and vulnerable immune systems, shaping future generations.

How did you conduct your research? I took a very hands-on approach in attending training that could further extend my own future practical application. Having spent time with staff and students at Wilson School in Auckland, I trained in geopathic stress testing (dowsing), assessment and shielding of electromagnetic radiation, and the fundamentals of building biology. The design has been developed by combining architectural application with involved research into the medical field, along with an understanding of ancient wisdom and applying this knowledge to a modern-day epidemic.

What are some of the observations you made? The most valuable observation I took away from this was not only how architecture can impact those with hypersensitivity but how basic understanding of natural radiation, man-made radiation and the impact of material specification can reduce the load on our already overloaded immune systems, drastically impacting the health of anyone.

What are some of the key outcomes? The most important thing we can do to design for autism and improve health is a combination of awareness, inclusion and exclusion. – Step one is to remove the cause. Electromagnetic radiation, geopathic stress and material toxicity make up an environmental load that impacts the body, behaviour and response to an environment. –

Step two is to provide an uplifting community to support and nurture spiritually, emotionally, physically and mentally. More than just providing sensory stimulation through sensory rooms and gardens, it’s about addressing the cellular level complications of autism to understand an environment and to reduce the symptoms.

Through sustainability and selective material choice, in line with building biology, implementing a ‘back-to-basics’ approach to reduce the chemical load emitted by materials. My project was broken into eight spaces that each worked to minimise or nurture one or more symptom of autism.

What’s the next step on your quest? I’ve only just begun! Since completing my thesis, I’ve continued to dowse houses of people with chronic illness in addition to those wanting to take preventative measures for the health of their families. Looking to the future, the principles that have been established are ones that will be carried through my architecture career, where the health of those occupying a space is my priority.

RELATED NEWS AND INSIGHTS

First Place

Minnesota Autism Center High School

Joe Tyndall

First high school for autistic students

Phoenix mayor honors first place phoenix..

Project Future: Unveiled

Inside the reimagining of project future, autism-friendly apartments open in phoenix.

Autism-friendly architecture from the outside in and the inside out: an explorative study based on autobiographies of autistic people

- Published: 10 May 2015

- Volume 31 , pages 179–195, ( 2016 )

Cite this article

- Marijke Kinnaer 1 ,

- Stijn Baumers 1 &

- Ann Heylighen 1

3292 Accesses

33 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Researchers and designers each developed a particular vision on autism-friendly architecture. Because the basis of this vision is not always clear, questions arise about its meaning and value and about how it can be put to use. People with a diagnosis on the autism spectrum are central to these questions, yet risk to disappear from the picture. Refocusing the discourse about autism-friendly architecture on them was the aim of the explorative study reported here. Six autobiographies written by autistic (young) adults were analysed from two different viewpoints. First, concepts from design guidelines concerning autism-friendly architecture were confronted with fragments from these autobiographies. The second part of the analysis started from the autobiographies themselves. This analysis shows that concepts can be interpreted in multiple ways. They can reinforce but also counteract each other, thus asking for critical judgment. An open space is preferred by some autistic people because it affords having an overview, which increases predictability, and distancing oneself from others without being isolated. Others might like this space to be subdivided into several separate spaces, which affords a sense of structure or reduces sensory inputs present in one room. The six autobiographies provide a glimpse of autistic people’s world of experience. Analysing these is a first step in revealing what architecture can actually mean from their point of view. For them, the material environment has a prominent meaning that is, however, not always reducible to design guidelines. It offers them something to hold on to, relate to or structure their reality.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Human/AI relationships: challenges, downsides, and impacts on human/human relationships

Artificial intelligence self-efficacy: Scale development and validation

AI Creativity and the Human-AI Co-creation Model

Differences exist between the notion of affordance as advanced by Gibson and that advanced by Norman ( 1999 ). However, a discussion of these differences transcends the scope of this article.

Ahrentzen, S. & Steele, K. (2009). Advancing full spectrum housing. Arizona Board of Regents . Phoenix. http://stardust.asu.edu/project-archive/advancing-full-spectrum-housing/

Albrecht, G. (2003). Disability values, representations and realities. In P. Devlieger, F. Rusch, & D. Pfeiffer (Eds.), Rethinking disability (pp. 27–44). Antwerp: Garant.

Google Scholar

APA. DSM-5. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders . Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Asperger, H. (1944). Autistic psychopathy in childhood (Autistischen Psychopathen im Kindesalter, U. Frith, Trans.). In U. Frith (Ed.) (1997). Autism and Asperger Syndrome (pp. 37–92). Cambridge: CUP.

Baumers, S., & Heylighen, A. (2010). Harnessing different dimensions of space. In: P. M. Langdon, P. J. Clarkson, & P. Robinson (Eds.), Designing inclusive interactions (pp. 13–23). London: Springer Verlag.

Beaver, C. (2011). Designing environments for children and adults on the autism spectrum. Good Autism Practice, 12 (1), 7–11.

Bettelheim, B. (1967). The empty fortress . New York: The Free Press.

Bogdashina, O. (2003). Sensory perceptual issues in Autism and Asperger Syndrome . London: Jessica Kingsley.

Braddock, D. L., Hemp, R. E., & Rizzolo, M. C. (2008). The state of the states in developmental disabilities (7th ed.). Washington, DC: American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities.

Brand, A. (2010). Living in the community . London: Helen Hamlyn Centre, Royal College of Art.

Coolen, H. (2006). The meaning of dwellings. Housing, Theory & Society, 23 (4), 185–201.

Article Google Scholar

Delacato, C. H. (1974). The ultimate stranger . Novato: Academic Therapy Publications.

Delfos, M. F. (2005). Een vreemde wereld [A strange world]. Amsterdam: uitgeverij SWP.

Dierckx de Casterle, B., Gastmans, C., Bryon, E., & Denier, Y. (2012). QUAGOL. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 49 , 360–371.

Dumortier, D. (2002). Van een andere planeet [From a different planet]. Antwerp: Houtekiet.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12 (2), 219–245.

Gerland, G. 1996. A real person . London: Souvenir Press (Trans. as: Een echt mens: Autobiografie van een autist . Antwerp: Houtekiet, 1998).

Gibson, J. J. (1979). The ecological approach to visual perception . Hopewell, NJ: Houghton Mifflin.

Grandin, T. (1995). Thinking in pictures and other reports from my life with autism . New York: Doubleday.

Kanner, L. (1943). Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child, 2 , 217–250.

Khare, R., & Mullick, A. (2009). Incorporating the behavioral dimension in designing inclusive learning environments for autism. Archnet-International Journal of Architectural Research, 3 (3), 45–64.

Kinnaer, M., Baumers, S., Heylighen, A. (2014). How do people with autism (like to) live?. In: P. Langdon, J. Lazar, A. Heylighen, & H. Dong (Eds.), Inclusive designing: Joining usability, accessibility, and inclusion (pp. 175–185). London: Springer Verlag.

Klonovsky, M. (1993). Vorwort. In B. Sellin (Ed.), Ich will kein Inmich mehr sein . Kiepenheuer & Witsch: Köln.

Landschip, & Modderman, L. (2004). Dubbelklik [Double click]. Berchem: EPO.

Lee O’Neill, J. (1999). Through the eyes of aliens . London: Jessica Kingsley.

Lynch, K. (1960). The image of the city . Cambridge: MIT Press.

Maier, J. R. A., & Fadel, G. M. (2009). An affordance-based approach to architectural theory, design, and practice. Design Studies, 30 (4), 393–414.

Mostafa, M. (2007). An architecture for Autism. Archnet-IJAR, 2 (1), 189–211.

Mostafa, M. (2010). Housing adaption for adults with autistic spectrum disorder. Open House International, 35 (1), 37–48.

Noens, I., & van Berckelaer-Onnes, I. (2004). Making sense in a fragmentary world. Autism, 8 (2), 197–218.

Norman, D. (1999). Affordance, conventions, and design. Interactions, 6 (3), 38–42.

Rajendran, G., & Mitchell, P. (2007). Cognitive theories of autism. Developmental Review, 27 (2), 224–260.

Sánchez, P. A., Vázquez, F. S., & Serrano, L. A. (2011). Autism and the built environment. In T. Willliams (Ed.), Autism spectrum disorders (pp. 363–380). Croatia: InTech.

Scott, I. (2009). Designing learning spaces for children on the autism spectrum. Good Autism Practice, 10 (1), 36–51.

Venderbosch, S. (2008). Een plek om te leven: een onderzoek naar de leefsituatie van mensen met autisme. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Autisme.

Vogel, C. (2008). Classroom design for living and learning with autism. Autism Asperger’s Digest, 3 , 30–40.

Whitehurst, T. (2006). The impact of building design on children with autistic spectrum disorders. Good Autism Practice, 7 (1), 31–38.

Willey, L. H. (1999). Pretending to be normal . London: Jessica Kingsley.

Williams, S., & Boult, M. (2009). Post action reviews: Property A, South Oxfordshire and Property B, West . Oxfordshire: Det Norske Veritas Ltd.

Wing, L. (1997). The history of ideas on autism. Autism, 1 , 13–23.

Wing, L., & Potter, D. (2002). The epidemiology of autistic spectrum disorders. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 8 (3), 151–161.

Wolfe, J. M., Kluender, K. R., & Levi, D. M. (2009). Sensation and Perception (2nd ed.). Sunderland: Sinauer Associates.

Download references

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their valuable comments on an earlier version of this article.

Conflict of interest

This research was supported by the Research Foundation—Flanders (FWO), the European Research Council under the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013)/ERC grant agreement no. 201673, and the Department of Architecture.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

KU Leuven, Department of Architecture, Research[x]Design, Kasteelpark Arenberg 1/2431, 3001, Heverlee, Leuven, Belgium

Marijke Kinnaer, Stijn Baumers & Ann Heylighen

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ann Heylighen .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Kinnaer, M., Baumers, S. & Heylighen, A. Autism-friendly architecture from the outside in and the inside out: an explorative study based on autobiographies of autistic people. J Hous and the Built Environ 31 , 179–195 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-015-9451-8

Download citation

Received : 14 April 2014

Accepted : 30 April 2015

Published : 10 May 2015

Issue Date : June 2016

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-015-9451-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Architecture

- Autobiographies

- Design guidance

- Lived experience

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Architecture for Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder and Their Therapists

Affiliation.

- 1 12346The University of Texas at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX, USA.

- PMID: 34006129

- DOI: 10.1177/19375867211012489

Objectives: The objective of this study is to identify an architectural design framework that can be applied to create adaptable, transformative therapy rooms that benefit children with autism and their therapists.

Background: Previous research suggests that environment shapes and influences human behavior. However, there remains a lack of evidence of effective design for pediatric rehabilitation therapy rooms. This study specifically focuses on how the design of the therapy room influences the patient's level of comfort and participation as well as the therapists' quality and efficiency of treatment to improve the overall therapeutic experience.

Method: Two different surveys were conducted to improve the design of a therapeutic room based on professional therapist experiences. A grounded theory approach was employed to identify specific codes and categories.

Results: The result of this study is an architectural framework based on specific design tenets and their properties that not only can be utilized by architects and interior designers for building a new therapy center but could also be used for remodeling existing therapy rooms.

Keywords: architectural framework; autism; cognitive disabilities; environment and behavior; evidence-based design; flexible design; healthcare architecture; inclusive learning environment; pediatric therapy; spatial layout; staff safety; treatment room.

- Autism Spectrum Disorder* / therapy

- Surveys and Questionnaires

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, prioritising public spaces architectural strategies for autistic users.

Archnet-IJAR

ISSN : 2631-6862

Article publication date: 24 June 2021

Issue publication date: 28 October 2021

According to architectural research, modifying environmental features has the potential to create an appropriate sensory environment for autistic children. Considering the design of public environments, it is difficult to accommodate the diverse requirements of each autistic child. The main objective of this paper is to find out the most prevalent architectural strategies and to prioritise them for the design of the public spaces addressing autistic children's needs.

Design/methodology/approach

This research is designed in two stages: (1) descriptive approach in which architectural strategies are extracted from theories on autism design to determine a theoretical test module; and (2) quantitative approach in which the frequency of gained strategies are studied in two groups of references: general references and key references (i.e. most cited and well-reputed researchers in autism architecture) while universal design strategies and the timeline of each strategy is considered for the conclusion.

The following strategies were highly significant: (1) acoustical control, (2) visual control, (3) legibility, (4) safety and security, (5) predictable spaces. Acoustic was frequently considered in both control and general groups while it was highlighted in timeline study and universal design strategies.

Research limitations/implications

The main limitation is that these strategies have been prioritised according to their frequency in some limited articles and a control group including the pioneer of autism design researchers while verifying these strategies may not be strong enough. Likewise, the conclusion related to these data cannot be accurate enough. Establishing a case study survey that provides an opportunity to test all these strategies directly on a majority of autistic children and measure their prevalence is advised. Finally, it should be considered that although the five mentioned strategies are all the most prevalent strategies among autistic children, as each autistic child differs from others, generalising the conclusion for all the public area would be impossible, as though we need to study it for each group of them.

Originality/value

Seeking to improve the strategies' prioritisation as determined by previous researchers, this article aims to define the most essential strategies categories in this field to eliminate the confusion of researchers and designers.

- Architecture

- Public spaces

- Environment design

- Sensory stimulation

Sheykhmaleki, P. , Yazdanfar, S.A.A. , Litkouhi, S. , Nazarian, M. and Price, A.D.F. (2021), "Prioritising public spaces architectural strategies for autistic users", Archnet-IJAR , Vol. 15 No. 3, pp. 555-570. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARCH-07-2020-0142

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2021, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Architecture for Autism: Overview and Analysis

Autism is a complicated spectrum disorder that involves consistent change of social interaction, verbal and nonverbal communication. Autistic children face difficulty in communication and working with the world outside. The effects of autism show severe signs and symptoms in children. The first symptoms are revealed in children around two to three years old. But apart from this, few children present symptoms until they are a toddler. If symptoms are noticed earlier the better as you can aide it as soon as possible. You can have digital therapy referrals that can assist you in your situation and help you out the best that they could. Give answers to your inquiries and right treatment for your child.

According to the CDC, one in 59 children is estimated to have autism. Therefore as a designer, we have a solid responsibility to design spaces for these specially-abled children.

The latest study revealed autism is more common in boys than in girls, and it is a lifelong condition connected to the child. Moreover, children diagnosed with autism syndrome can live life independently as every child deserves the best. Hence as a designer, it is our responsibility to make it possible.

Need of Autism and Architecture

According to the latest report by CDC estimates that 2-5 children out of 1000 have symptoms of autism disorder. In addition to this, the numbers are increasing rapidly. In India, 1 in 88 are suffering from autism syndrome. The government only recognized the disorder in 2001, till the 1990s, there were reports that autism didn’t exist in India (dry Vinod Kumar Goyal TOI). These alarming rates of increase call for attention by all the fields, and clear architecture has been ignoring the effect of the built environment in their development.

Such statistics are encouraging designers to look for specially-abled children. The increasing numbers tell us that as a designer we are responsible for designing the spaces for specially-abled users . It doesn’t matter if it is a mental or physical disability. Now the architecture industry has to come forward to design spaces for the specially-abled.

Classification of Autism Syndrome

Autism syndrome is common in children; when we are about to design spaces for them, it is important to know the types and classification of the condition. It helps in understanding the condition and encourages design for a user-end experience. The autism syndrome is classified as follows :

- Asperger Syndrome

Autism children who are diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome are very intelligent and can handle their daily activities. The autistic child might be very focused on topics of interest but will find it difficult to socialize with others.

- Pervasive developmental disorder

The pervasive developmental disorder is the next supreme level of Asperger’s syndrome. It might not appear like an autism disorder but has an extreme level of behavioral pattern.

- Autistic disorder

It has the same signs and symptoms as Asperger’s syndrome; the autistic child will find it difficult to interact with others and have slow learning skills.

- Childhood disintegrative disorder

Childhood disintegrative disorder is the rarest and severe part of the syndrome. It is a seizure disorder where an autistic child loses all social and mental skills during the first five years.

- Rett Syndrome

Rett Syndrome is associated with autism disorder, and experts group it under spectrum disorder. A genetic mutation causes it; therefore, it is not considered ASD.

Therapy spaces for Autistic children

When designing for autistic-oriented users, we must look into their behavior patterns as a designer. Autistic children have different ways of communication, and therefore we must design spaces that help in easier communication with its user. The designer must add a sense of connection, and an architect must add calmness for specially-abled users.

- Occupational therapy

Occupational therapy teaches a skill that helps the person live as independently as possible skills might include dressing, eating, bathing, and relating to people

- Sensory integration therapy

Sensory integration therapy helps the person deal with sensory information like sights, sounds, and smells. In addition to this, it helps autistic children who are not bothered by the sound.

- Speech therapy

Speech therapy has a vital role in improving the autistic child’s communication skills. In addition to this, it helps in the development of verbal communication skills. For others, using gestures or picture boards is more realistic

- The pictures exchange communication systems

Pecs uses picture symbols to teach communication skills. Autistic children communicate by using picture symbols for conversation.

Awareness for Autistic oriented design

The study has stressed the importance of including students on the Autism spectrum in general education environments. This inclusion, that is, their integration and participation to attend the same classes with non-disabled students, would not be achieved without providing the necessary support. This support includes a quiet, distraction-free learning environment with sufficient personal space that would allow them to recalibrate and readjust their senses.

That in addition to the high-interest areas that conform to these students’ statuses, and that would make their inclusion a The various strategies presented in this study reveal the importance of the role of architects in providing these inclusive environments that should guarantee equal opportunities for all society members and help mainstream students with autism into society social mainstream.

- Raising the awareness of professional architects and designers of the importance of providing inclusive autism-friendly environments, especially educational ones, to prepare the members of this group for better community integration and a higher quality of life.

- It is important to teach the next generation of designers through adjusted curriculum and courses for a specially-abled design perspective.

- Raising community awareness of the importance of autism and architecture.

Case Study: Advanced Autism Center, Egypt

There is no better way to study a typology of design than a case study. Advanced Autism Center Egypt is located in Cairo, Egypt. Ar Magda Mustafa designed it. Furthermore, Ar. Magda Mostafa designed the spaces for autistic children keeping their behavioral and design concepts in mind. Therefore the spaces are divided purposely into low, high, and transitional stimuli zones. The site is located in Cairo and is surrounded by township and katameta golf tennis.

The internal spaces are divided as per sensory potential into three groups. The groups of design stimuli are low, high, and transitional spaces. The criteria of stimuli are used in escape space, translational spaces, and sensory zones. The center is placed on the west side of Cairo in a residential area. Low-rise buildings define the character of the area.

Stimuli are defined as unusual reactions in the respective sensory organs.

High Stimuli: Sensory information coming from a built environment might be a simple bright color.

Low Stimuli: In the low stimulus environment project.

Transition space: The sensory garden is organized. Inspiring the different senses — sight, sound, taste, touch, smell. A garden with a play area for physical development. The two zones are connected by a long corridor that provides intimacy to the treatment. This area is the administration department and hydrotherapy. And these areas are under high stimuli.

Hydrotherapy: Inspiring the different senses, sight, sound, taste, touch, and smell. Hydrotherapy can improve social behaviors, and it can aid sensory processing disorders in the central transition nucleus, providing easy access to all the treatment rooms. The structure is divided into four volumes of spaces and has a five-floor height massing. In addition to this, it has a sports center, public relations area, and hostel units.

Design perspective

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a complex developmental condition involving persistent challenges in social interaction, speech, nonverbal communication, and restricted/repetitive behaviors. Studying the mindset of autistics in itself is a very vast subject; hence the topic limits itself to the study and research of their behavioral aspects in educational environments and environments which help them in rehabilitation. The main perspective of design should be defining quiet spaces, open circulations, and multi-sensory spaces.

The perspective of the design should be:

- To understand the environmental implication for teaching strategies used for children with autism in educational spaces.

- Address their needs and design accommodation based on their behavioral aspects, cultural and social aspects.

- Visual character, spatial sequencing, and it’s quality escape areas clutter-free space color texture materials acoustics.

https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/42147

https://www.aaed.org/uncategorized/autism-and-architecture/

https://www.archnet.org/publications/9101

https://my.archdaily.com/us/@mark-p/folders/autism

Ar. Ritu Gosavi is a published co-author of the two anthology " A poet's Pulse" and "Slice of life" , graduated from College of Architecture Nasik .A brilliant content writer since 2019 bringing light on social and patriarchal norms through her writing page called "Ruminant". An architect, author, and audacious , a classical and japanese literature lover.

Rethinking Architecture Beyond Buildings

The Evolution of Materials in Architecture

Related posts.

School for Blind and Visually Impaired Children by SEAlab

Chowmahalla Palace, Hyderabad

Sanskar Kendra, Ahmedabad

Project in-depth: The Channel Tunnel (Eurotunnel), UK-France

The Lingaraja Temple, Odisha

Evergreen Line Stations by Perkins and Will

- Architectural Community

- Architectural Facts

- RTF Architectural Reviews

- Architectural styles

- City and Architecture

- Fun & Architecture

- History of Architecture

- Design Studio Portfolios

- Designing for typologies

- RTF Design Inspiration

- Architecture News

- Career Advice

- Case Studies

- Construction & Materials

- Covid and Architecture

- Interior Design

- Know Your Architects

- Landscape Architecture

- Materials & Construction

- Product Design

- RTF Fresh Perspectives

- Sustainable Architecture

- Top Architects

- Travel and Architecture

- Rethinking The Future Awards 2022

- RTF Awards 2021 | Results

- GADA 2021 | Results

- RTF Awards 2020 | Results

- ACD Awards 2020 | Results

- GADA 2019 | Results

- ACD Awards 2018 | Results

- GADA 2018 | Results

- RTF Awards 2017 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2017 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2016 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2015 | Results

- RTF Awards 2014 | Results

- RTF Architectural Visualization Competition 2020 – Results

- Architectural Photography Competition 2020 – Results

- Designer’s Days of Quarantine Contest – Results

- Urban Sketching Competition May 2020 – Results

- RTF Essay Writing Competition April 2020 – Results

- Architectural Photography Competition 2019 – Finalists

- The Ultimate Thesis Guide

- Introduction to Landscape Architecture

- Perfect Guide to Architecting Your Career

- How to Design Architecture Portfolio

- How to Design Streets

- Introduction to Urban Design

- Introduction to Product Design

- Complete Guide to Dissertation Writing

- Introduction to Skyscraper Design

- Educational

- Hospitality

- Institutional

- Office Buildings

- Public Building

- Residential

- Sports & Recreation

- Temporary Structure

- Commercial Interior Design

- Corporate Interior Design

- Healthcare Interior Design

- Hospitality Interior Design

- Residential Interior Design

- Sustainability

- Transportation

- Urban Design

- Host your Course with RTF

- Architectural Writing Training Programme | WFH

- Editorial Internship | In-office

- Graphic Design Internship

- Research Internship | WFH

- Research Internship | New Delhi

- RTF | About RTF

- Submit Your Story

Looking for Job/ Internship?

Rtf will connect you with right design studios.

Autism Center

Project Description: The Center for Autism is an integrated and multidisciplinary clinical, training program dedicated to treating individuals with autism spectrum disorder. The main focus of the project is to help the autistic children between 5-10 ages achieve independence and facilitate their interactions with external environment. Concept: The Project concept relied on the main design principles for the Autism Spectrum. It depends on using looping programming scheme to connect project different zones (Blocks) with a main internal shared space, through a “one-way” circulation scheme that builds on the special needs user’s affinity to routine employed throughout this building.

Name: Autism Center Architect: Saja Abdulmohsen Bai Location: Jeddah, KSA Site Area: 10,200 m2 The Proposed Program: - Administration Building - Educational (Classes,Workshops, Library) - Living Center (Accommodation & Nursing Rooms) Total GFA: 5,296 m2

Student: Saja Abdulmohsen Bai Supervisor: Dr. Mohammed fekry, Capstone Project (Effat University)

- Hispanoamérica

- Work at ArchDaily

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Architecture Competitions

The Living Pavilion - Architecture for Community and Learning at India Autism Center

- Published on December 04, 2023

One-of-a-kind inclusive community grounded in neurodiversity, India Autism Center (IAC) is a multidisciplinary non-profit organization for individuals with autism spectrum disorder and other related conditions. The competition site of 3000 sq ft (built up of 4500 sq ft) is located within the campus, an integrated 39-acre community neighborhood, currently under construction at Sirakole, West Bengal.The project is envisioned to create an inclusive community - with the provision of residential, educational, vocational, clinical, and recreational services as well as employment avenues.

The Living Pavilion is envisioned to be a space anchoring four critical agendas in the Masterplan: a space for information, to enable refuge and retreat for the IAC Staff, as a small event space with a cafe and as a conscious development reflecting the ethos and inclusiveness of the campus.

Registration Deadline

Submission deadline.

This competition was submitted by an ArchDaily user. If you'd like to submit a competition, call for submissions or other architectural 'opportunity' please use our "Submit a Competition" form. The views expressed in announcements submitted by ArchDaily users do not necessarily reflect the views of ArchDaily.

- Sustainability

世界上最受欢迎的建筑网站现已推出你的母语版本!

想浏览archdaily中国吗, you've started following your first account, did you know.

You'll now receive updates based on what you follow! Personalize your stream and start following your favorite authors, offices and users.

Study links organization of neurotypical brains to genes involved in autism and schizophrenia

T he organization of the human brain develops over time, following the coordinated expression of thousands of genes. Linking the development of healthy brain organization to genes involved in mental health conditions such as autism and schizophrenia could help to reveal the biological causes of these disorders.

Researchers at University of Cambridge and other institutes worldwide recently carried out a study that linked gene expression in healthy brains to the imaging, transcriptomics and genetics of autism spectrum disorder and schizophrenia. Their paper, published in Nature Neuroscience , unveiled three distinct spatial patterns of cortical gene expression each with specific associations to autism and schizophrenia.

"Prior work had shown that all human brains have the same primary spatial pattern of gene expression (C1) reflecting the hierarchy of connections between neurons," Richard Dear, co-author of the paper, told Medical Xpress. "Our hypothesis was that there is probably more than one pattern organizing how the twenty-thousand human genes are expressed across our brains."

The primary objective of the recent study by Dear and his colleagues was to uncover new spatial patterns of gene expression. They hoped that these new patterns would shed light on so-called "transcriptional programs," the biological mechanisms through which the human brain develops both in health and disease.

"The key challenge for this study was the limited data available," Dear said. "The Allen Human Brain Atlas remains the only gene expression dataset with high spatial resolution across the brain, and it was collected from only six healthy donors. We therefore had to find a way to identify patterns in these limited data that we were confident represent general transcriptional programs shared across all human brains."

As part of their study, the researchers ran various computational analyses to validate their results, including a permutation test for robustness and validation in three distinct types of independent data. They also searched for associations between the new transcriptional programs and previously published data related to brain organization, development, gene expression, and genetic variation associated with brain function in both health and disease.

"What was most striking was how each new analysis that we performed converged on the same consistent story," Dear explained. "The second pattern of gene expression (C2) relates to cognitive metabolism and autism, while the third pattern (C3) relates to brain plasticity in adolescence and schizophrenia. Critically, both patterns were identified and validated entirely in brains from neurotypical donors."

Dear and his collaborators are the first to link neurotypical brain gene expression to autism and schizophrenia across three common types of prior results (i.e., case-control neuroimaging, differential gene expression, and genome-wide association studies). Their results suggest that data collected using these distinct techniques, which previously appeared to be unrelated, can in fact be traced back to the same transcriptional programs that guide the development of healthy human brains.

"The next step for us will be to dive deeper into the biology of the three patterns to understand them at a more mechanistic level, leveraging recently published single-nucleus RNA sequencing data," Dear added. "For example, we hope to discover the key genes or transcription factors guiding the expression of the C1–C3 patterns early in development across different cell types. We also hope that these three patterns and the optimized analysis code we developed will be a resource for other scientists seeking to understand the genetic underpinnings of the brain's spatial organization."

More information: Richard Dear et al, Cortical gene expression architecture links healthy neurodevelopment to the imaging, transcriptomics and genetics of autism and schizophrenia, Nature Neuroscience (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41593-024-01624-4

© 2024 Science X Network

COMMENTS

The papers are peer-reviewed studies, monographies, and grey literature (reports and guidelines of case studies and realized projects). Review articles, dissertations, conference proceedings, editorials, and comments. The studies outcomes are design criteria, guidelines, spatial requirements to promote and design autism-friendly environment.

Social Sensory Architecture for Children with Autism. August 20, 2019. U-M architect and an associate professor at the University of Michigan's Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning ...

This 4 storeyed center comprises of 8 classrooms for the secondary children, 5 Parent- child intervention rooms, 2 Sensory rooms, 2 Occupational therapy. rooms, a library and a Research unit. The ...

Lucy Healy is an Architect with several years experience working on community, education and special educational needs projects. Here, she gives her insight into designing 'sensory sensitive' educational spaces for children with autism. According to a 2018 survey by the American Centre for Disease Control, 1 in 59 children are diagnosed with autism compared to 1 in 150 in 2000.

architecture can change autistic children's lives. An existing alcove providing an opportunity to pause and control the amount of incoming information. Author provided. Introducing the touch of ...

Background study of ASD. ASD is a neurodevelopmental condition that affects children from a young age. It is marked by functional impairment in social communication, limited interests, selective attention, repetitive habits, as well as hypersensitivity to touch, vision, taste, or sound in certain people ( Remington et al., 2009).Autistic disorder, high-functioning autism (HFA), Asperger ...

Published on October 09, 2013. Share. In 2002, Magda Mostafa, a then-PhD student at Cairo University, was given an exciting project: to design Egypt's first educational centre for autism. The ...

Designing for Autism: A Case Study ... Autism and Developmental Disorders Jon Boyd, AIA E4H Environments for Health Architecture . Overview • Best Practices in Autism Design • Incorporating Biophilic Design • Sustainability • Creating the "Autism Classroom of the Future" Best Practices in Autism Design Key Considerations ...

Autism Design and Architecture For All: Architecture for a Differently Abled World. December 2021. Publisher: IQD. ISBN: 1970-9250. Authors: Magda Mostafa. Progressive Architects. References (8)

Taking the Sensory Design Theory to housing design, Mostafa presents a case study of the Charis Workhome in the Netherlands, describing the development of design criteria for a customized retrofit housing project for adults with autism spectrum disorder in Rotterdam (Mostafa, 2010). These criteria translated the sensory design principles under ...

Abstract. One in every 150 children is estimated to fall within. the autistic spectrum, regardless of socio-cultural. and economic aspects, with a 4:1 prevalence of. males over females (ADDM, 2007 ...

The objective of this study is to identify an architectural design framework that can be applied to create adaptable, transformative therapy rooms that benefit children with autism and their therapists.

Furthermore, employing autism-aware design in architecture goes beyond the call of duty for those with ASD by being beneficial to those who are neurotypicals also. This is supported through Dr Mostafa's research, where, in one case study, teachers as well as students gained indirectly from an improved acoustical environment.

Architecture Masters Dissertation using case study research to explore how informed design can help to improve the sensory experience of those on the autism spectrum in educational buildings in ...

Architecture for Autism: Exterior Views. Written by Christopher N. Henry. Published on April 04, 2012. In 2007 I visited one of the most talked about autism buildings at the time, the Netley ...

Refocusing the discourse about autism-friendly architecture on them was the aim of the explorative study reported here. Six autobiographies written by autistic (young) adults were analysed from two different viewpoints. ... Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2), 219-245. Article ...

Objectives: The objective of this study is to identify an architectural design framework that can be applied to create adaptable, transformative therapy rooms that benefit children with autism and their therapists. Background: Previous research suggests that environment shapes and influences human behavior. However, there remains a lack of evidence of effective design for pediatric ...

Design/methodology/approach. This research is designed in two stages: (1) descriptive approach in which architectural strategies are extracted from theories on autism design to determine a theoretical test module; and (2) quantitative approach in which the frequency of gained strategies are studied in two groups of references: general references and key references (i.e. most cited and well ...

Raising community awareness of the importance of autism and architecture. Case Study: Advanced Autism Center, Egypt There is no better way to study a typology of design than a case study. Advanced Autism Center Egypt is located in Cairo, Egypt. Ar Magda Mustafa designed it. Furthermore, Ar. Magda Mostafa designed the spaces for autistic ...

The Center for Autism is an integrated and multidisciplinary clinical, training program dedicated to treating individuals with autism spectrum disorder. The main focus of the project is to help the autistic children between 5-10 ages achieve independence and facilitate their interactions with external environment. The Project concept relied on ...

While preparing drawings for the Thomas Bewick School—Newcastle's local area autism center for children—Humphreys felt the initial proposal far underestimated the spatial requirements for ...

Roger Williams University

Background: Parents report associations between children's sleep disturbances and behaviors. Children with neurodevelopmental conditions (e.g., Williams Syndrome and autism) are consistently reported to experience increased sleeping problems. Sleep in children with vision impairment and children with a dual diagnosis of vision impairment and autism remains understudied. Methods: Our ...

The Living Pavilion - Architecture for Community and Learning at India Autism Center. One-of-a-kind inclusive community grounded in neurodiversity, India Autism Center (IAC) is a multidisciplinary ...

More information: Richard Dear et al, Cortical gene expression architecture links healthy neurodevelopment to the imaging, transcriptomics and genetics of autism and schizophrenia, Nature ...

Additionally, it advocates for the use of VR as a tool for the preservation and restoration of cultural heritage within the realm of film and architecture. The case study's significance lies in its contribution to the preservation of film culture and the architectural legacy of Expressionism.