- Board of Directors

What is CPS?

Cps = c reative p roblem s olving, cps is a proven method for approaching a problem or a challenge in an imaginative and innovative way. it helps you redefine the problems and opportunities you face, come up with new, innovative responses and solutions, and then take action..

Why does CPS work?

CPS begins with two assumptions:

- Everyone is creative in some way.

- Creative skills can be learned and enhanced.

Osborn noted there are two distinct kinds of thinking that are essential to being creative:

Divergent thinking.

Brainstorming is often misunderstood as the entire Creative Problem Solving process. Brainstorming is the divergent thinking phase of the CPS process. It is not simply a group of people in a meeting coming up with ideas in a disorganized fashion. Brainstorming at its core is generating lots of ideas. Divergence allows us to state and move beyond obvious ideas to breakthrough ideas. (Fun Fact: Alex Osborn, founder of CEF, coined the term “brainstorm.” Osborn was the “O” from the ad agency BBDO.)

Convergent Thinking

Convergent thinking applies criteria to brainstormed ideas so that those ideas can become actionable innovations. Divergence provides the raw material that pushes beyond every day thinking, and convergence tools help us screen, select, evaluate, and refine ideas, while retaining novelty and newness.

To drive a car, you need both the gas and the brake.

But you cannot use the gas and brake pedals at the same time — you use them alternately to make the car go. Think of the gas pedal as Divergence , and the brake pedal as Convergence . Used together you move forward to a new destination.

Each of us use divergent and convergent thinking daily, intuitively. CPS is a deliberate process that allows you to harness your natural creative ability and apply it purposefully to problems, challenges, and opportunities.

The CPS Process

Based on the osborn-parnes process, the cps model uses plain language and recent research., the basic structure is comprised of four stages with a total of six explicit process steps. , each step uses divergent and convergent thinking..

Learner’s Model based on work of G.J. Puccio, M. Mance, M.C. Murdock, B. Miller, J. Vehar, R. Firestien, S. Thurber, & D. Nielsen (2011)

Explore the Vision. Identify the goal, wish, or challenge.

Gather Data. Describe and generate data to enable a clear understanding of the challenge.

Formulate Challenges. Sharpen awareness of the challenge and create challenge questions that invite solutions.

Explore Ideas. Generate ideas that answer the challenge questions.

Formulate Solutions. To move from ideas to solutions. Evaluate, strengthen, and select solutions for best “fit.”

Formulate a Plan. Explore acceptance and identify resources and actions that will support implementation of the selected solution(s).

Explore Ideas. Generate ideas that answer the challenge question

Core Principles of Creative Problem Solving

- Everyone is creative.

- Divergent and Convergent Thinking Must be Balanced. Keys to creativity are learning ways to identify and balance expanding and contracting thinking (done separately), and knowing when to practice them.

- Ask Problems as Questions. Solutions are more readily invited and developed when challenges and problems are restated as open-ended questions with multiple possibilities. Such questions generate lots of rich information, while closed-ended questions tend to elicit confirmation or denial. Statements tend to generate limited or no response at all.

- Defer or Suspend Judgment. As Osborn learned in his early work on brainstorming, the instantaneous judgment in response to an idea shuts down idea generation . There is an appropriate and necessary time to apply judgement when converging.

- Focus on “Yes, and” rather than “No, but.” When generating information and ideas, language matters. “Yes, and…” allows continuation and expansion , which is necessary in certain stages of CPS. The use of the word “but” – preceded by “yes” or “no” – closes down conversation, negating everything that has come before it.

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- AI Essentials for Business

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading Change and Organizational Renewal

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

What Is Creative Problem-Solving & Why Is It Important?

- 01 Feb 2022

One of the biggest hindrances to innovation is complacency—it can be more comfortable to do what you know than venture into the unknown. Business leaders can overcome this barrier by mobilizing creative team members and providing space to innovate.

There are several tools you can use to encourage creativity in the workplace. Creative problem-solving is one of them, which facilitates the development of innovative solutions to difficult problems.

Here’s an overview of creative problem-solving and why it’s important in business.

Access your free e-book today.

What Is Creative Problem-Solving?

Research is necessary when solving a problem. But there are situations where a problem’s specific cause is difficult to pinpoint. This can occur when there’s not enough time to narrow down the problem’s source or there are differing opinions about its root cause.

In such cases, you can use creative problem-solving , which allows you to explore potential solutions regardless of whether a problem has been defined.

Creative problem-solving is less structured than other innovation processes and encourages exploring open-ended solutions. It also focuses on developing new perspectives and fostering creativity in the workplace . Its benefits include:

- Finding creative solutions to complex problems : User research can insufficiently illustrate a situation’s complexity. While other innovation processes rely on this information, creative problem-solving can yield solutions without it.

- Adapting to change : Business is constantly changing, and business leaders need to adapt. Creative problem-solving helps overcome unforeseen challenges and find solutions to unconventional problems.

- Fueling innovation and growth : In addition to solutions, creative problem-solving can spark innovative ideas that drive company growth. These ideas can lead to new product lines, services, or a modified operations structure that improves efficiency.

Creative problem-solving is traditionally based on the following key principles :

1. Balance Divergent and Convergent Thinking

Creative problem-solving uses two primary tools to find solutions: divergence and convergence. Divergence generates ideas in response to a problem, while convergence narrows them down to a shortlist. It balances these two practices and turns ideas into concrete solutions.

2. Reframe Problems as Questions

By framing problems as questions, you shift from focusing on obstacles to solutions. This provides the freedom to brainstorm potential ideas.

3. Defer Judgment of Ideas

When brainstorming, it can be natural to reject or accept ideas right away. Yet, immediate judgments interfere with the idea generation process. Even ideas that seem implausible can turn into outstanding innovations upon further exploration and development.

4. Focus on "Yes, And" Instead of "No, But"

Using negative words like "no" discourages creative thinking. Instead, use positive language to build and maintain an environment that fosters the development of creative and innovative ideas.

Creative Problem-Solving and Design Thinking

Whereas creative problem-solving facilitates developing innovative ideas through a less structured workflow, design thinking takes a far more organized approach.

Design thinking is a human-centered, solutions-based process that fosters the ideation and development of solutions. In the online course Design Thinking and Innovation , Harvard Business School Dean Srikant Datar leverages a four-phase framework to explain design thinking.

The four stages are:

- Clarify: The clarification stage allows you to empathize with the user and identify problems. Observations and insights are informed by thorough research. Findings are then reframed as problem statements or questions.

- Ideate: Ideation is the process of coming up with innovative ideas. The divergence of ideas involved with creative problem-solving is a major focus.

- Develop: In the development stage, ideas evolve into experiments and tests. Ideas converge and are explored through prototyping and open critique.

- Implement: Implementation involves continuing to test and experiment to refine the solution and encourage its adoption.

Creative problem-solving primarily operates in the ideate phase of design thinking but can be applied to others. This is because design thinking is an iterative process that moves between the stages as ideas are generated and pursued. This is normal and encouraged, as innovation requires exploring multiple ideas.

Creative Problem-Solving Tools

While there are many useful tools in the creative problem-solving process, here are three you should know:

Creating a Problem Story

One way to innovate is by creating a story about a problem to understand how it affects users and what solutions best fit their needs. Here are the steps you need to take to use this tool properly.

1. Identify a UDP

Create a problem story to identify the undesired phenomena (UDP). For example, consider a company that produces printers that overheat. In this case, the UDP is "our printers overheat."

2. Move Forward in Time

To move forward in time, ask: “Why is this a problem?” For example, minor damage could be one result of the machines overheating. In more extreme cases, printers may catch fire. Don't be afraid to create multiple problem stories if you think of more than one UDP.

3. Move Backward in Time

To move backward in time, ask: “What caused this UDP?” If you can't identify the root problem, think about what typically causes the UDP to occur. For the overheating printers, overuse could be a cause.

Following the three-step framework above helps illustrate a clear problem story:

- The printer is overused.

- The printer overheats.

- The printer breaks down.

You can extend the problem story in either direction if you think of additional cause-and-effect relationships.

4. Break the Chains

By this point, you’ll have multiple UDP storylines. Take two that are similar and focus on breaking the chains connecting them. This can be accomplished through inversion or neutralization.

- Inversion: Inversion changes the relationship between two UDPs so the cause is the same but the effect is the opposite. For example, if the UDP is "the more X happens, the more likely Y is to happen," inversion changes the equation to "the more X happens, the less likely Y is to happen." Using the printer example, inversion would consider: "What if the more a printer is used, the less likely it’s going to overheat?" Innovation requires an open mind. Just because a solution initially seems unlikely doesn't mean it can't be pursued further or spark additional ideas.

- Neutralization: Neutralization completely eliminates the cause-and-effect relationship between X and Y. This changes the above equation to "the more or less X happens has no effect on Y." In the case of the printers, neutralization would rephrase the relationship to "the more or less a printer is used has no effect on whether it overheats."

Even if creating a problem story doesn't provide a solution, it can offer useful context to users’ problems and additional ideas to be explored. Given that divergence is one of the fundamental practices of creative problem-solving, it’s a good idea to incorporate it into each tool you use.

Brainstorming

Brainstorming is a tool that can be highly effective when guided by the iterative qualities of the design thinking process. It involves openly discussing and debating ideas and topics in a group setting. This facilitates idea generation and exploration as different team members consider the same concept from multiple perspectives.

Hosting brainstorming sessions can result in problems, such as groupthink or social loafing. To combat this, leverage a three-step brainstorming method involving divergence and convergence :

- Have each group member come up with as many ideas as possible and write them down to ensure the brainstorming session is productive.

- Continue the divergence of ideas by collectively sharing and exploring each idea as a group. The goal is to create a setting where new ideas are inspired by open discussion.

- Begin the convergence of ideas by narrowing them down to a few explorable options. There’s no "right number of ideas." Don't be afraid to consider exploring all of them, as long as you have the resources to do so.

Alternate Worlds

The alternate worlds tool is an empathetic approach to creative problem-solving. It encourages you to consider how someone in another world would approach your situation.

For example, if you’re concerned that the printers you produce overheat and catch fire, consider how a different industry would approach the problem. How would an automotive expert solve it? How would a firefighter?

Be creative as you consider and research alternate worlds. The purpose is not to nail down a solution right away but to continue the ideation process through diverging and exploring ideas.

Continue Developing Your Skills

Whether you’re an entrepreneur, marketer, or business leader, learning the ropes of design thinking can be an effective way to build your skills and foster creativity and innovation in any setting.

If you're ready to develop your design thinking and creative problem-solving skills, explore Design Thinking and Innovation , one of our online entrepreneurship and innovation courses. If you aren't sure which course is the right fit, download our free course flowchart to determine which best aligns with your goals.

About the Author

How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 10 min read

Creative Problem Solving

Finding innovative solutions to challenges.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

Imagine that you're vacuuming your house in a hurry because you've got friends coming over. Frustratingly, you're working hard but you're not getting very far. You kneel down, open up the vacuum cleaner, and pull out the bag. In a cloud of dust, you realize that it's full... again. Coughing, you empty it and wonder why vacuum cleaners with bags still exist!

James Dyson, inventor and founder of Dyson® vacuum cleaners, had exactly the same problem, and he used creative problem solving to find the answer. While many companies focused on developing a better vacuum cleaner filter, he realized that he had to think differently and find a more creative solution. So, he devised a revolutionary way to separate the dirt from the air, and invented the world's first bagless vacuum cleaner. [1]

Creative problem solving (CPS) is a way of solving problems or identifying opportunities when conventional thinking has failed. It encourages you to find fresh perspectives and come up with innovative solutions, so that you can formulate a plan to overcome obstacles and reach your goals.

In this article, we'll explore what CPS is, and we'll look at its key principles. We'll also provide a model that you can use to generate creative solutions.

About Creative Problem Solving

Alex Osborn, founder of the Creative Education Foundation, first developed creative problem solving in the 1940s, along with the term "brainstorming." And, together with Sid Parnes, he developed the Osborn-Parnes Creative Problem Solving Process. Despite its age, this model remains a valuable approach to problem solving. [2]

The early Osborn-Parnes model inspired a number of other tools. One of these is the 2011 CPS Learner's Model, also from the Creative Education Foundation, developed by Dr Gerard J. Puccio, Marie Mance, and co-workers. In this article, we'll use this modern four-step model to explore how you can use CPS to generate innovative, effective solutions.

Why Use Creative Problem Solving?

Dealing with obstacles and challenges is a regular part of working life, and overcoming them isn't always easy. To improve your products, services, communications, and interpersonal skills, and for you and your organization to excel, you need to encourage creative thinking and find innovative solutions that work.

CPS asks you to separate your "divergent" and "convergent" thinking as a way to do this. Divergent thinking is the process of generating lots of potential solutions and possibilities, otherwise known as brainstorming. And convergent thinking involves evaluating those options and choosing the most promising one. Often, we use a combination of the two to develop new ideas or solutions. However, using them simultaneously can result in unbalanced or biased decisions, and can stifle idea generation.

For more on divergent and convergent thinking, and for a useful diagram, see the book "Facilitator's Guide to Participatory Decision-Making." [3]

Core Principles of Creative Problem Solving

CPS has four core principles. Let's explore each one in more detail:

- Divergent and convergent thinking must be balanced. The key to creativity is learning how to identify and balance divergent and convergent thinking (done separately), and knowing when to practice each one.

- Ask problems as questions. When you rephrase problems and challenges as open-ended questions with multiple possibilities, it's easier to come up with solutions. Asking these types of questions generates lots of rich information, while asking closed questions tends to elicit short answers, such as confirmations or disagreements. Problem statements tend to generate limited responses, or none at all.

- Defer or suspend judgment. As Alex Osborn learned from his work on brainstorming, judging solutions early on tends to shut down idea generation. Instead, there's an appropriate and necessary time to judge ideas during the convergence stage.

- Focus on "Yes, and," rather than "No, but." Language matters when you're generating information and ideas. "Yes, and" encourages people to expand their thoughts, which is necessary during certain stages of CPS. Using the word "but" – preceded by "yes" or "no" – ends conversation, and often negates what's come before it.

How to Use the Tool

Let's explore how you can use each of the four steps of the CPS Learner's Model (shown in figure 1, below) to generate innovative ideas and solutions.

Figure 1 – CPS Learner's Model

Explore the Vision

Identify your goal, desire or challenge. This is a crucial first step because it's easy to assume, incorrectly, that you know what the problem is. However, you may have missed something or have failed to understand the issue fully, and defining your objective can provide clarity. Read our article, 5 Whys , for more on getting to the root of a problem quickly.

Gather Data

Once you've identified and understood the problem, you can collect information about it and develop a clear understanding of it. Make a note of details such as who and what is involved, all the relevant facts, and everyone's feelings and opinions.

Formulate Questions

When you've increased your awareness of the challenge or problem you've identified, ask questions that will generate solutions. Think about the obstacles you might face and the opportunities they could present.

Explore Ideas

Generate ideas that answer the challenge questions you identified in step 1. It can be tempting to consider solutions that you've tried before, as our minds tend to return to habitual thinking patterns that stop us from producing new ideas. However, this is a chance to use your creativity .

Brainstorming and Mind Maps are great ways to explore ideas during this divergent stage of CPS. And our articles, Encouraging Team Creativity , Problem Solving , Rolestorming , Hurson's Productive Thinking Model , and The Four-Step Innovation Process , can also help boost your creativity.

See our Brainstorming resources within our Creativity section for more on this.

Formulate Solutions

This is the convergent stage of CPS, where you begin to focus on evaluating all of your possible options and come up with solutions. Analyze whether potential solutions meet your needs and criteria, and decide whether you can implement them successfully. Next, consider how you can strengthen them and determine which ones are the best "fit." Our articles, Critical Thinking and ORAPAPA , are useful here.

4. Implement

Formulate a plan.

Once you've chosen the best solution, it's time to develop a plan of action. Start by identifying resources and actions that will allow you to implement your chosen solution. Next, communicate your plan and make sure that everyone involved understands and accepts it.

There have been many adaptations of CPS since its inception, because nobody owns the idea.

For example, Scott Isaksen and Donald Treffinger formed The Creative Problem Solving Group Inc . and the Center for Creative Learning , and their model has evolved over many versions. Blair Miller, Jonathan Vehar and Roger L. Firestien also created their own version, and Dr Gerard J. Puccio, Mary C. Murdock, and Marie Mance developed CPS: The Thinking Skills Model. [4] Tim Hurson created The Productive Thinking Model , and Paul Reali developed CPS: Competencies Model. [5]

Sid Parnes continued to adapt the CPS model by adding concepts such as imagery and visualization , and he founded the Creative Studies Project to teach CPS. For more information on the evolution and development of the CPS process, see Creative Problem Solving Version 6.1 by Donald J. Treffinger, Scott G. Isaksen, and K. Brian Dorval. [6]

Creative Problem Solving (CPS) Infographic

See our infographic on Creative Problem Solving .

Creative problem solving (CPS) is a way of using your creativity to develop new ideas and solutions to problems. The process is based on separating divergent and convergent thinking styles, so that you can focus your mind on creating at the first stage, and then evaluating at the second stage.

There have been many adaptations of the original Osborn-Parnes model, but they all involve a clear structure of identifying the problem, generating new ideas, evaluating the options, and then formulating a plan for successful implementation.

[1] Entrepreneur (2012). James Dyson on Using Failure to Drive Success [online]. Available here . [Accessed May 27, 2022.]

[2] Creative Education Foundation (2015). The CPS Process [online]. Available here . [Accessed May 26, 2022.]

[3] Kaner, S. et al. (2014). 'Facilitator′s Guide to Participatory Decision–Making,' San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

[4] Puccio, G., Mance, M., and Murdock, M. (2011). 'Creative Leadership: Skils That Drive Change' (2nd Ed.), Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

[5] OmniSkills (2013). Creative Problem Solving [online]. Available here . [Accessed May 26, 2022].

[6] Treffinger, G., Isaksen, S., and Dorval, B. (2010). Creative Problem Solving (CPS Version 6.1). Center for Creative Learning, Inc. & Creative Problem Solving Group, Inc. Available here .

You've accessed 1 of your 2 free resources.

Get unlimited access

Discover more content

4 logical fallacies.

Avoid Common Types of Faulty Reasoning

Everyday Cybersecurity

Keep Your Data Safe

Add comment

Comments (0)

Be the first to comment!

Gain essential management and leadership skills

Busy schedule? No problem. Learn anytime, anywhere.

Subscribe to unlimited access to meticulously researched, evidence-based resources.

Join today and save on an annual membership!

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Most Popular

Latest Updates

Better Public Speaking

How to Build Confidence in Others

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

How to create psychological safety at work.

Speaking up without fear

How to Guides

Pain Points Podcast - Presentations Pt 1

How do you get better at presenting?

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

7 ways to combat anxiety.

Using simple techniques to de-stress

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Team Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

- About us

Creative problem solving: basics, techniques, activities

Why is creative problem solving so important.

Problem-solving is a part of almost every person's daily life at home and in the workplace. Creative problem solving helps us understand our environment, identify the things we want or need to change, and find a solution to improve the environment's performance.

Creative problem solving is essential for individuals and organizations because it helps us control what's happening in our environment.

Humans have learned to observe the environment and identify risks that may lead to specific outcomes in the future. Anticipating is helpful not only for fixing broken things but also for influencing the performance of items.

Creative problem solving is not just about fixing broken things; it's about innovating and creating something new. Observing and analyzing the environment, we identify opportunities for new ideas that will improve our environment in the future.

The 7-step creative problem-solving process

The creative problem-solving process usually consists of seven steps.

1. Define the problem.

The very first step in the CPS process is understanding the problem itself. You may think that it's the most natural step, but sometimes what we consider a problem is not a problem. We are very often mistaken about the real issue and misunderstood them. You need to analyze the situation. Otherwise, the wrong question will bring your CPS process in the wrong direction. Take the time to understand the problem and clear up any doubts or confusion.

2. Research the problem.

Once you identify the problem, you need to gather all possible data to find the best workable solution. Use various data sources for research. Start with collecting data from search engines, but don't forget about traditional sources like libraries. You can also ask your friends or colleagues who can share additional thoughts on your issue. Asking questions on forums is a good option, too.

3. Make challenge questions.

After you've researched the problem and collected all the necessary details about it, formulate challenge questions. They should encourage you to generate ideas and be short and focused only on one issue. You may start your challenge questions with "How might I…?" or "In what way could I…?" Then try to answer them.

4. Generate ideas.

Now you are ready to brainstorm ideas. Here it is the stage where the creativity starts. You must note each idea you brainstorm, even if it seems crazy, not inefficient from your first point of view. You can fix your thoughts on a sheet of paper or use any up-to-date tools developed for these needs.

5. Test and review the ideas.

Then you need to evaluate your ideas and choose the one you believe is the perfect solution. Think whether the possible solutions are workable and implementing them will solve the problem. If the result doesn't fix the issue, test the next idea. Repeat your tests until the best solution is found.

6. Create an action plan.

Once you've found the perfect solution, you need to work out the implementation steps. Think about what you need to implement the solution and how it will take.

7. Implement the plan.

Now it's time to implement your solution and resolve the issue.

Top 5 Easy creative thinking techniques to use at work

1. brainstorming.

Brainstorming is one of the most glaring CPS techniques, and it's beneficial. You can practice it in a group or individually.

Define the problem you need to resolve and take notes of every idea you generate. Don't judge your thoughts, even if you think they are strange. After you create a list of ideas, let your colleagues vote for the best idea.

2. Drawing techniques

It's very convenient to visualize concepts and ideas by drawing techniques such as mind mapping or creating concept maps. They are used for organizing thoughts and building connections between ideas. These techniques have a lot in common, but still, they have some differences.

When starting a mind map, you need to put the key concept in the center and add new connections. You can discover as many joints as you can.

Concept maps represent the structure of knowledge stored in our minds about a particular topic. One of the key characteristics of a concept map is its hierarchical structure, which means placing specific concepts under more general ones.

3. SWOT Analysis

The SWOT technique is used during the strategic planning stage before the actual brainstorming of ideas. It helps you identify strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of your project, idea, or business. Once you analyze these characteristics, you are ready to generate possible solutions to your problem.

4. Random words

This technique is one of the simplest to use for generating ideas. It's often applied by people who need to create a new product, for example. You need to prepare a list of random words, expressions, or stories and put them on the desk or board or write them down on a large sheet of paper.

Once you have a list of random words, you should think of associations with them and analyze how they work with the problem. Since our brain is good at making connections, the associations will stimulate brainstorming of new ideas.

5. Storyboarding

This CPS method is popular because it tells a story visually. This technique is based on a step-creation process. Follow this instruction to see the storyboarding process in progress:

- Set a problem and write down the steps you need to reach your goal.

- Put the actions in the right order.

- Make sub-steps for some steps if necessary. This will help you see the process in detail.

- Evaluate your moves and try to identify problems in it. It's necessary for predicting possible negative scenarios.

7 Ways to improve your creative problem-solving skills

1. play brain games.

It's considered that brain games are an excellent way to stimulate human brain function. They develop a lot of thinking skills that are crucial for creative problem-solving.

You can solve puzzles or play math games, for example. These activities will bring you many benefits, including strong logical, critical, and analytical thinking skills.

If you are keen on playing fun math games and solving complicated logic tasks, try LogicLike online.

We created 3500+ puzzles, mathematical games, and brain exercises. Our website and mobile app, developed for adults and kids, help to make pastime more productive just in one place.

2. Practice asking questions

Reasoning stimulates you to generate new ideas and solutions. To make the CPS process more accessible, ask questions about different things. By developing curiosity, you get more information that broadens your background. The more you know about a specific topic, the more solutions you will be able to generate. Make it your useful habit to ask questions. You can research on your own. Alternatively, you can ask someone who is an expert in the field. Anyway, this will help you improve your CPS skills.

3. Challenge yourself with new opportunities

After you've gained a certain level of creativity, you shouldn't stop developing your skills. Try something new, and don't be afraid of challenging yourself with more complicated methods and techniques. Don't use the same tools and solutions for similar problems. Learn from your experience and make another step to move to the next level.

4. Master your expertise

If you want to keep on generating creative ideas, you need to master your skills in the industry you are working in. The better you understand your industry vertical, the more comfortable you identify problems, find connections between them, and create actionable solutions.

Once you are satisfied with your professional life, you shouldn't stop learning new things and get additional knowledge in your field. It's vital if you want to be creative both in professional and daily life. Broaden your background to brainstorm more innovative solutions.

5. Develop persistence

If you understand why you go through this CPS challenge and why you need to come up with a resolution to your problem, you are more motivated to go through the obstacles you face. By doing this, you develop persistence that enables you to move forward toward a goal.

Practice persistence in daily routine or at work. For example, you can minimize the time you need to implement your action plan. Alternatively, some problems require a long-term period to accomplish a goal. That's why you need to follow the steps or try different solutions until you find what works for solving your problem. Don't forget about the reason why you need to find a solution to motivate yourself to be persistent.

6. Improve emotional intelligence

Empathy is a critical element of emotional intelligence. It means that you can view the issues from the perspective of other people. By practicing compassion, you can understand your colleagues that work on the project together with you. Understanding will help you implement the solutions that are beneficial for you and others.

7. Use a thinking strategy

You are mistaken if you think that creative thinking is an unstructured process. Any thinking process is a multi-step procedure, and creative thinking isn't an exclusion. Always follow a particular strategy framework while finding a solution. It will make your thinking activity more efficient and result-oriented.

Develop your logic and mathematical skills. 3500+ fun math problems and brain games with answers and explanations.

Home | Services | Articles | Report 103 eJournal | Books | Videos | ACT Questions | About | Contact

Creative Problem Solving (CPS) Basics

By jeffrey baumgartner.

I wrote this article on creative problem solving (CPS) in 2010. However, not long after writing it, a growing unhappiness with the method as a creativity technique caused me to analyse the CPS methodology in detail, identify its flaws and devise a better approach. In 2011, I did that with anticonventional thinking (ACT) . I believe that ACT is a far better method for generating highly creative ideas than is CPS. To learn more about the flaws of CPS (and it's simpler variation of brainstorming), read this .

Nevertheless, a large number of creativity consultants and others swear by CPS. So, I leave the original text of the article below.

Creative ideas do not suddenly appear in people's minds for no apparent reason. Rather, they are the result of trying to solve a specific problem or to achieve a particular goal. Albert Einstein's theories of relativity were not sudden inspirations. Rather they were the result of a huge amount of mental problem solving trying to close a discrepancy between the laws of physics and the laws of electromagnetism as they were understood at the time.

Albert Einstein, Leonardo da Vinci, Thomas Edison and other creative geniuses have always worked in the same way. They do not wait for creative ideas to strike them. Rather they focus on trying to solve a clearly stated, at least in their minds, problem.

This approach has been formalised as Creative Problem Solving (CPS). CPS is a simple process that involves breaking down a problem to understand it, generating ideas to solve the problem and evaluating those ideas to find the most effective solutions. Highly creative people tend to follow this process in their heads, without thinking about it. Less naturally creative people simply have to learn to use this very simple process.

Although creative problem solving has been around as long as humans have been thinking creatively and solving problems, it was first formalised as a process by Alex Osborn, who invented traditional brainstorming, and Sidney Parnes. Their Creative Problem Solving Process (CPSP) has been taught at the International Center for Studies in Creativity at Buffalo College in Buffalo, New York since the 1950s.

However, there are numerous different approaches to CPS. Mine is more focused on innovation (that is the implementation of the most promising ideas). It involves seven straightforward steps.

- Clarify and identify the problem

- Research the problem

- Formulate creative challenges

- Identify insights

- Generate ideas

- Combine and evaluate the ideas

- Draw up an action plan

- Do it! (ie. implement the ideas)

Let us look at each step more carefully.

1. Clarify and identify the problem

Arguably the single most important step of CPS is identifying your real problem or goal. This may seem easy, but very often, what we believe to be the problem is not the real problem or goal. For instance, you may feel you need a new job. However, if you break down your problem and analyse what you are really looking for, it may transpire that the actual issue is that your income does not cover your costs of living. In this case, the solution may be a new job, but it might also be to re-arrange your expenses or to seek a pay rise from your existing employer.

The best way to clarify the problem and understand the underlying issues is to ask yourself -- or better still, ask a friend or family member to ask you -- a series of questions about your problem in order to clarify the true issues behind the problem. The first question to ask is simply: "why is this a problem?" or "why do I wish to achieve this goal?". Once you have answered that, ask yourself "why else?" four more times.

For instance, you might feel you want to overcome your shyness. So, you ask yourself why and you answer: "because I am lonely". Then ask yourself "why else?" four times. You answer: "because I do not know many people in this new city where I live", "because I find it hard to meet people", "because I am doing many activities alone" and "because I would like to do activities with other people who share my interests". This last "why else" is clearly more of the issue than reducing shyness. Indeed, if you had focused your creative energy on solving your shyness issue, you would not have actually solved the real problem. On the other hand, if you focused your creative energy on finding people with whom to share activities, you would be happier without ever having to address the shyness issue.

And More Questions

In addition, you can further clarify your problem by asking questions like: "what do I really wish to accomplish?", "what is preventing me from solving this problem/achieving the goal?", "how do I envision myself in six months/one year/five years [choose most relevant time span] as a result of solving this problem?" and "are my friends dealing with similar problems? If so, how are they coping?"

By the time you have answered all these questions, you should have a very clear idea of what your problem or real goal is.

The final step is to decide what criteria you will eventually use to evaluate or judge the ideas. Are there budget limitations, timeframe or other restrictions that will affect whether or not you can go ahead with an idea? What will you want to have accomplished with the ideas? What do you wish to avoid when you implement these ideas? Think about it and make a list of three to five evaluation criteria. Then put the list aside. You will not need it for a while.

2. Research the Problem

The next step in CPS is to research the problem in order to get a better understanding of it. Depending on the nature of the problem, you may need to do a great deal of research or very little. The best place to start these days is with your favourite search engine. But do not neglect good old fashioned sources of information and opinion. Libraries are fantastic for in-depth information that is easier to read than computer screens. Friends, colleagues and family can also provide thoughts on many issues. Fora on sites like LinkedIn and elsewhere are ideal for asking questions. There's nothing an expert enjoys more than imparting her knowledge. Take advantage of that. But always try to get feedback from several people to ensure you get rounded information.

3. Formulate Creative Challenges

By now, you should be clear on the real issues behind your problems or goals. The next step is to turn these issues into creative challenges. A creative challenge is basically a simple question framed to encourage suggestions or ideas. In English, a challenge typically starts with "In what ways might I [or we]...?" or "How might I...?" or "How could I...?"

Creative challenges should be simple, concise and focus on a single issue. For example: "How might I improve my Chinese language skills and find a job in Shanghai?" is two completely separate challenges. Trying to generate ideas that solve both challenges will be difficult and, as a result, will stifle idea generation. So separate these into two challenges: "How might I improve my Chinese language skills" and "How might I find a job in Shanghai". Then attack each challenge individually. Once you have ideas for both, you may find a logical approach to solving both problems in a coordinated way. Or you might find that there is not co-ordinate way and each problem must be tackled separately.

Creative challenges should not include evaluation criteria. For example: "How might I find a more challenging job that is better paying and situated close to my home?" If you put criteria in the challenge, you will limit your creative thinking. So simply ask: "How might a I find a more challenging job?" and after generating ideas, you can use the criteria to identify the ideas with the greatest potential. ( Here's a more detailed article on formulating creative challenges )

4. Identify Insights and Inspiration

You are almost ready to start generating ideas, but before you work on ideas in response to your challenge, think about what might provide insight and inspiration that will help you generate ideas. Some forms of inspiration are unrelated to the challenge. For instance, I like to go for long walks for inspiration. I also find the music of Bach provides me with deeper vision into problems. Other people like to lay down or take a bath. Whatever works for you is great.

You may seek inspiration before you generate ideas, for instance by reading up on research related to the problem. Or you might seek inspiration during the idea generation session by brainstorming in a beautiful location. If the challenge is a B2B (business to business) issue, why not brainstorm in one of your customers' premises?

5. Generate Ideas

Finally, we come to the part most people associate with brainstorming and creative problem solving: idea generation. And you probably know how this works. Take only one creative challenge. Give yourself some quiet time and try to generate at least 50 ideas that may or may not solve the challenge. You can do this alone or you can invite some friends or family members to help you.

Irrespective of your idea generation approach, write your ideas on a document. You can simply write them down in linear fashion, write them down on a mind-map, enter them onto a computer document (such as MS Word or OpenOffice) or use a specialised software for idea generation. The method you use is not so important. What is important is that you follow these rules:

Write down every idea that comes to mind. Even if the idea is ludicrous, stupid or fails to solve the challenge, write it down. Most people are their own worst critics and by squelching their own ideas, make themselves less creative. So write everything down. NO EXCEPTIONS!

If other people are also involved, insure that no one criticises anyone else's ideas in any way. This is called squelching, because even the tiniest amount of criticism can discourage everyone in the group for sharing their more creative ideas. Even a sigh or the rolling of eyes can be critical. Squelching must be avoided!

If you are working alone, don't stop until you've reached your target of 50 (or more) ideas. If you are working with other people, set a time limit like 15 or 20 minutes. Once you have reached this time limit, compare ideas and make a grand list that includes them all. Then ask everyone if the have some new ideas. Most likely people will be inspired by others' ideas and add more to the list.

If you find you are not generating sufficient ideas, give yourself some inspiration. A classic trick is to open a book or dictionary and pick out a random word. Then generate ideas that somehow incorporate this word. You might also ask yourself what other people whom you know; such as your grandmother, your partner, a friend or a character on you favourite TV show, might suggest.

Brainstorming does not need to occur at your desk. Take a trip somewhere for new inspiration. Find a nice place in a beautiful park. Sit down in a coffee shop on a crowded street corner. You can even walk and generate ideas.

In addition, if you browse the web for brainstorming and idea generation, you will find lots of creative ideas on how to generate creative ideas!

One last note. If you are not in a hurry, wait until the next day and then try to generate another 25 ideas, ideally do this in the morning. Research has shown that our minds work on creative challenges while we sleep. Your initial idea generation session has been good exercise and has certainly generated some great ideas. But it will probably also inspire your unconscious mind to generate some ideas while you sleep. Don't lose them!

6. Combine and Evaluate Ideas

After you have written down all of your ideas, take a break. It might just be an hour. It might be a day or more. Then go through the ideas. Related ideas can be combined together to form big ideas (or idea clusters).

Then, using the criteria you devised earlier, choose all of the ideas that broadly meet those criteria. This is important. If you focus only on the "best" ideas or your favourite ideas, the chances are you will choose the less creative ones! Nevertheless, feel free to include your favourite ideas in the initial list of ideas.

Now get out that list of criteria you mad earlier and go through each idea more carefully. Consider how well it meets each criterion and give it a rating of 0-5 points with five indicating a perfect match. If an idea falls short of a criterion, think about why this is so. Is there a way that it can be improved in order to increase its score? If so, make a note. Once you are finished, all of the ideas will have an evaluation score. Those ideas with the highest score best meet your criteria. They may not be your best ideas or your favourite ideas, but they are most likely to best solve your problem or enable you t achieve your goal.

Depending on the nature of the challenge and the winning ideas, you may be ready to jump right in and implement your ideas. In other cases, ideas may need to be developed further. With complex ideas, a simple evaluation may not be enough. You may need to do a SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats) or discuss the idea with others who will be affected by it. If the idea is business related, you may need to do a business case, market research, build a prototype or a combination of all of these.

Also, bear in mind that you do not need to limit yourself to one winning idea. Often you can implement several ideas in order to solve your challenge.

* There are a number of variations on the approach to CPS. All follow roughly the same steps. This is the approach I used to use.

© 2010, 2014 creativejeffrey.com

Recent Articles

Leading Diverse Teams Filed under: Business Innovation Diverse teams are more innovative and smarter than homogeneous ones. But, they are also harder to manager. Here are some tips. By Jeffrey Baumgartner -- Read the article...

Questions you should ask when an innovative project fails Filed under: Business Innovation You can learn a lot from the failure of an innovative project, but you need to ask the right questions. Here are those questions. By Jeffrey Baumgartner -- Read the article...

Unmarketing the Competition Filed under: Business Innovation A look at creative, but unethical dirty trick marketing campaigns designed to damage the competition By Jeffrey Baumgartner -- Read the article...

Imaginativefulness and the Fisherman Filed under: Creativity What does a fisherman wearing a cycling helmet have to do with imaginativefulness? Quite a lot, it seems. By Jeffrey Baumgartner -- Read the article...

Actually, Criticising Ideas Is Good for Creativity Filed under: Creativity People have long assumed criticising ideas in a brainstorm inhibits creativity. Research and experience shows that is wrong By Jeffrey Baumgartner -- Read the article...

Imaginativefulness Filed under: Creativity Imaginativefulness is a state of heightened imagination in which your mind allows thoughts, memories and ideas to play with each other freely. By Jeffrey Baumgartner -- Read the article...

Why and How to Exploit Alternative Uses for Your Products Filed under: Business Innovation Discovering new ways customers use, misuse and could use your products can inspire innovation. Jeffrey Baumgartner explains. By Jeffrey Baumgartner -- Read the article...

The Cost of Not Innovating Filed under: Business Innovation If your company fails to innovate, you pay a steep price in terms of loss of leadershop, tight margins, missed opportunities and more. By Jeffrey Baumgartner -- Read the article...

Don't Trust the Status Quo Filed under: Creativity Jeffrey Baumgartner has never trusted the status quo. He explains why this is so and why you should also not trust the status quo By Jeffrey Baumgartner -- Read the article...

Index of all creative articles...

Return to top of page

Jeffrey Baumgartner Bwiti bvba

Erps-Kwerps (near Leuven & Brussels) Belgium

My other web projects

Creativity - An Overview/Creative Problem Solving Process (CPS)

The Creative Problem Solving Process (CPS), also known as the Osborn-Parnes CPS process, was developed by Alex Osborn and Dr. Sidney J. Parnes in the 1950s. [1] CPS is a structured method for generating novel and useful solutions to problems. CPS follows three process stages, which match a person's natural creative process, and six explicit steps: [2]

CPS is flexible, and its use depends on the situation. The steps can be (and often are) used in a linear fashion, from start to finish, but it is not necessary to use all the steps. For example, if one already has a clearly-defined problem, the process would begin at Idea Finding.

What distinguishes the Osborn-Parnes CPS process from other "creative problem solving" methods is the use of both divergent and convergent thinking during each process step, and not just when generating ideas to solve the problem. Each step begins with divergent thinking, a broad search for many alternatives. This is followed by convergent thinking, the process of evaluating and selecting.

This method is taught at the International Center for Studies in Creativity, [3] the Creative Problem Solving Institute, [4] and CREA Conference. [5] It is specifically acknowledged as a key influence for the Productive Thinking Model. [6]

References [ edit | edit source ]

- ↑ What is CPS? . Creative Education Foundation, 2010. Retrieved on 2010-06-13.

- ↑ "ICSC Course Descriptions" . International Center for Studies in Creativity . Retrieved 2007-12-22 .

- ↑ "Creative Problem Solving Institute" . Creative Education Foundation . Retrieved 2007-12-22 .

- ↑ "Programs" . CREA Conference . Creativity European Association . Retrieved 2008-01-07 .

- ↑ Hurson, Tim (2007). Think Better: An Innovator's Guide to Productive Thinking . New York, New York: McGraw Hill. pp. xii. ISBN 978-0071494939 . {{ cite book }} : Cite has empty unknown parameter: |coauthors= ( help )

- Book:Creativity - An Overview

- CS1 errors: empty unknown parameters

Navigation menu

The Basics of Creative Problem Solving – CPS

By: Jeffrey Baumgartner

Creative problem solving isn’t just brainstorming, although that’s what many people may associate it with. It’s actually a well-defined process that can help you from problem definition to implementing solutions, according to Jeffrey Baumgartner.

Creative ideas do not suddenly appear in people’s minds for no apparent reason. Rather, they are the result of trying to solve a specific problem or to achieve a particular goal. Albert Einstein’s theories of relativity were not sudden inspirations. Rather they were the result of a huge amount of mental problem solving trying to close a discrepancy between the laws of physics and the laws of electromagnetism as they were understood at the time.

Albert Einstein, Leonardo da Vinci, Thomas Edison and other creative geniuses have always worked in the same way. They do not wait for creative ideas to strike them. Rather they focus on trying to solve a clearly stated, at least in their minds, problem. This is just like important TED talks to ideate for business innovation specifically discussed to get a better solution for existing problems.

This approach has been formalized as Creative Problem Solving (CPS). CPS is a simple process that involves breaking down a problem to understand it, generating ideas to solve the problem and evaluating those ideas to find the most effective solutions. Highly creative people tend to follow this process in their heads, without thinking about it. Less naturally creative people simply have to learn to use this very simple process.

A 7-step CPS framework

Although creative problem solving has been around as long as humans have been thinking creatively and solving problems, it was first formalised as a process by Alex Osborn, who invented traditional brainstorming, and Sidney Parnes. Their Creative Problem Solving Process (CPSP) has been taught at the International Center for Studies in Creativity at Buffalo College in Buffalo, New York since the 1950s.

However, there are numerous different approaches to CPS. Mine is more focused on innovation (that is the implementation of the most promising ideas). It involves seven straightforward steps.

How to Turn Crowdsourced Ideas Into Business Proposals

In October 2020, Pact launched AfrIdea, a regional innovation program supported by the U.S. Department of State. This was geared towards unlocking the potential of West African entrepreneurs, social activists, and developers in uncovering solutions to post-COVID challenges. Through a contest, training, idea-a-thon and follow-on funding, they sought to activate a network of young entrepreneurs and innovators from Guinea, Mali, Senegal, and Togo to source and grow innovative solutions. Learn their seven-stage process in the AfrIdea case study.

Get the Case Study

- Clarify and identify the problem

- Research the problem

- Formulate creative challenges

- Generate ideas

- Combine and evaluate the ideas

- Draw up an action plan

- Do it! (implement the ideas)

Let us look at each step more closely:

1. Clarify and identify the problem

Arguably the single most important step of CPS is identifying your real problem or goal. This may seem easy, but very often, what we believe to be the problem is not the real problem or goal. For instance, you may feel you need a new job. However, if you break down your problem and analyse what you are really looking for, it may transpire that the actual issue is that your income does not cover your costs of living. In this case, the solution may be a new job, but it might also be to re-arrange your expenses or to seek a pay rise from your existing employer.

Five whys: A powerful problem-definition technique

The best way to clarify the problem and understand the underlying issues is to ask yourself – or better still, ask a friend or family member to ask you – a series of questions about your problem in order to clarify the true issues behind the problem. The first question to ask is simply: “why is this a problem?” or “why do I wish to achieve this goal?” Once you have answered that, ask yourself “why else?” four more times.

For instance, you might feel you want to overcome your shyness. So, you ask yourself why and you answer: “because I am lonely”. Then ask yourself “Why else?” four times. You answer: “Because I do not know many people in this new city where I live”, “Because I find it hard to meet people”, “Because I am doing many activities alone” and “Because I would like to do activities with other people who share my interests”. This last “why else” is clearly more of the issue than reducing shyness. Indeed, if you had focused your creative energy on solving your shyness issue, you would not have actually solved the real problem. On the other hand, if you focused your creative energy on finding people with whom to share activities, you would be happier without ever having to address the shyness issue.

More questions you can ask to help clearly define the problem

In addition, you can further clarify your problem by asking questions like: “What do I really wish to accomplish?”, “What is preventing me from solving this problem/achieving the goal?”, “How do I envision myself in six months/one year/five years [choose most relevant time span] as a result of solving this problem?” and “Are my friends dealing with similar problems? If so, how are they coping?”

By the time you have answered all these questions, you should have a very clear idea of what your problem or real goal is.

Set criteria for judging potential solutions

The final step is to decide what criteria you will eventually use to evaluate or judge the ideas. Are there budget limitations, timeframe or other restrictions that will affect whether or not you can go ahead with an idea? What will you want to have accomplished with the ideas? What do you wish to avoid when you implement these ideas? Think about it and make a list of three to five evaluation criteria. Then put the list aside. You will not need it for a while.

2. Research the problem

The next step in CPS is to research the problem in order to get a better understanding of it. Depending on the nature of the problem, you may need to do a great deal of research or very little. The best place to start these days is with your favourite search engine. But do not neglect good old fashioned sources of information and opinion. Libraries are fantastic for in-depth information that is easier to read than computer screens. Friends, colleagues and family can also provide thoughts on many issues. Fora on sites like LinkedIn and elsewhere are ideal for asking questions. There’s nothing an expert enjoys more than imparting her knowledge. Take advantage of that. But always try to get feedback from several people to ensure you get well-rounded information.

3. Formulate one or more creative challenges

By now, you should be clear on the real issues behind your problems or goals. The next step is to turn these issues into creative challenges. A creative challenge is basically a simple question framed to encourage suggestions or ideas. In English, a challenge typically starts with “In what ways might I [or we]…?” or “How might I…?” or “How could I…?”

Creative challenges should be simple, concise and focus on a single issue. For example: “How might I improve my Chinese language skills and find a job in Shanghai?” is two completely separate challenges. Trying to generate ideas that solve both challenges will be difficult and, as a result, will stifle idea generation. So separate these into two challenges: “How might I improve my Chinese language skills?” and “How might I find a job in Shanghai?” Then attack each challenge individually. Once you have ideas for both, you may find a logical approach to solving both problems in a coordinated way. Or you might find that there is not a coordinated way and each problem must be tackled separately.

Creative challenges should not include evaluation criteria. For example: “How might I find a more challenging job that is better paying and situated close to my home?” If you put criteria in the challenge, you will limit your creative thinking. So simply ask: “How might a I find a more challenging job?” and after generating ideas, you can use the criteria to identify the ideas with the greatest potential.

4. Generate ideas

Finally, we come to the part most people associate with brainstorming and creative problem solving: idea generation. And you probably know how this works. Take only one creative challenge. Give yourself some quiet time and try to generate at least 50 ideas that may or may not solve the challenge. You can do this alone or you can invite some friends or family members to help you.

Irrespective of your idea generation approach, write your ideas on a document. You can simply write them down in linear fashion, write them down on a mind map, enter them onto a computer document (such as Microsoft Word or OpenOffice) or use a specialized software for idea generation. The method you use is not so important. What is important is that you follow these rules:

Write down every idea that comes to mind. Even if the idea is ludicrous, stupid or fails to solve the challenge, write it down. Most people are their own worst critics and by squelching their own ideas, make themselves less creative. So write everything down. NO EXCEPTIONS!

If other people are also involved, insure that no one criticizes anyone else’s ideas in any way. This is called squelching, because even the tiniest amount of criticism can discourage everyone in the group for sharing their more creative ideas. Even a sigh or the rolling of eyes can be critical. Squelching must be avoided!

If you are working alone, don’t stop until you’ve reached your target of 50 (or more) ideas. If you are working with other people, set a time limit like 15 or 20 minutes. Once you have reached this time limit, compare ideas and make a grand list that includes them all. Then ask everyone if the have some new ideas. Most likely people will be inspired by others’ ideas and add more to the list.

If you find you are not generating sufficient ideas, give yourself some inspiration. A classic trick is to open a book or dictionary and pick out a random word. Then generate ideas that somehow incorporate this word. You might also ask yourself what other people whom you know; such as your grandmother, your partner, a friend or a character on you favourite TV show, might suggest.

Brainstorming does not need to occur at your desk. Take a trip somewhere for new inspiration. Find a nice place in a beautiful park. Sit down in a coffee shop on a crowded street corner. You can even walk and generate ideas.

In addition, if you browse the web for brainstorming and idea generation, you will find lots of creative ideas on how to generate creative ideas!

One last note: If you are not in a hurry, wait until the next day and then try to generate another 25 ideas; ideally do this in the morning. Research has shown that our minds work on creative challenges while we sleep. Your initial idea generation session has been good exercise and has certainly generated some great ideas. But it will probably also inspire your unconscious mind to generate some ideas while you sleep. Don’t lose them!

5. Combine and evaluate ideas

After you have written down all of your ideas, take a break. It might just be an hour. It might be a day or more. Then go through the ideas. Related ideas can be combined together to form big ideas (or idea clusters).

Then, using the criteria you devised earlier, choose all of the ideas that broadly meet those criteria. This is important. If you focus only on the “best” ideas or your favorite ideas, the chances are you will choose the less creative ones! Nevertheless, feel free to include your favorite ideas in the initial list of ideas.

Now get out that list of criteria you made earlier and go through each idea more carefully. Consider how well it meets each criterion and give it a rating of 0 to 5 points, with five indicating a perfect match. If an idea falls short of a criterion, think about why this is so. Is there a way that it can be improved in order to increase its score? If so, make a note. Once you are finished, all of the ideas will have an evaluation score. Those ideas with the highest score best meet your criteria. They may not be your best ideas or your favorite ideas, but they are most likely to best solve your problem or enable you to achieve your goal.

Depending on the nature of the challenge and the winning ideas, you may be ready to jump right in and implement your ideas. In other cases, ideas may need to be developed further. With complex ideas, a simple evaluation may not be enough. You may need to do a SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats) analysis or discuss the idea with others who will be affected by it. If the idea is business related, you may need to do a business case, market research, build a prototype or a combination of all of these.

Also, keep in mind that you do not need to limit yourself to one winning idea. Often you can implement several ideas in order to solve your challenge.

6. Draw up an action plan

At this point, you have some great ideas. However, a lot of people have trouble motivating themselves to take the next step. Creative ideas may mean big changes or taking risks. Some of us love change and risk. Others are scared by it. Draw up an action plan with the simple steps you need to take in order to implement your ideas. Ideas that involve a lot work to implement can be particularly intimidating. Breaking their implementation down into a series of readily accomplished tasks makes these ideas easier to cope with and implement.

This is the simplest step of all. Take your action plan and implement your idea. And if the situation veers away from your action plan steps, don’t worry. Rewrite your action plan!

CPS and innovation

Any effective innovation initiative or process will use CPS at the front end. Our innovation process does so. TRIZ also uses elements of CPS. Any effective and sustainable idea management system or ideation activity will be based on CPS.

Systems and methods that do not use CPS or use it badly, on the other hand, tend not to be sustainable and fail early on. Suggestion schemes in which employees or the public are invited to submit any idea whatsoever are effectively asking users of the system to determine a problem and then offer a solution. This will result not only in many ideas, but many different problems, most of which will not be relevant to your strategic needs. Worse, having to evaluate every idea in the context of its implied problem – which may not be clear – is a nightmare from a resource point of view.

Systems and methods which are based on CPS, but in which creative challenges are poorly defined, also deliver poor results either because users do not understand the challenge or the problem is poorly understood and the resulting challenge stimulates ideas which in themselves are good, but which are not actually solutions to the true problem.

That said, CPS is a conceptually simple process – but critical to any innovation process. If you do not use it already, familiarize yourself with the process and start using it. You will find it does wonders for your innovativeness.

By Jeffrey Baumgartner

About the author

Main image: young person thinking with glowing puzzle mind from Shutterstock.com

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Privacy overview.

Using the Creative Problem Solving Profile (CPSP) for Diagnosing and Solving Real-World Problems

Min Basadur Basadur Applied Creativity Center for Research, CAN

Garry Gelade Basadur Applied Creativity Center for Research, CAN

Introduction

Organizations around the world face a common challenge: the need to improve their performance in order to capitalize on rapid change. In North America, restructuring and downsizing have become a way of life as organizations struggle to regain market share from global companies producing higher-quality products. In eastern Europe, managers and employees strive to establish new behaviors and procedures that will allow their companies to compete in the free market. In the developing world, countries hungry for economic development look for growth markets abroad. In Japan, organizations that once had a clear target—to overtake their western competitors—now lack a blueprint for further progress.

A SIMPLE BLUEPRINT

Mott (1972) presented evidence that effective organizations display three characteristics: efficiency, adaptability, and flexibility. The efficient organization follows well-structured, stable routines for delivering its product or service in high quantities, with high quality, and at low cost. In a stable world, efficient organizations may be successful. But in a changing world, organizations also need adaptability. While efficiency implies mastering a routine, adaptability means mastering the process of changing a routine. Adaptable organizations monitor the environment for new technologies, ideas, and methods, anticipate threats and opportunities, and implement changes accordingly. They deliberately and continually change their routines to improve quality, raise quantities, reduce costs, and stay ahead of their competitors. The most effective organizations are both efficient and highly adaptable. While adaptability is a proactive process of looking for ways to change, flexibility is reactive. Flexibility allows the organization to react quickly to unexpected disruptions without getting mired in organizational bureaucracy. It allows the efficient organization to deal with disruptions while maintaining its routines. In today's rapidly changing world, leaders of effective organizations aiming to achieve sustained competitive edge induce not merely efficiency and flexibility but adaptability.

THE PROCESS APPROACH TO APPLIED CREATIVITY

Basadur (1992, 1995) provided evidence that organizations can attain sustainable competitive edge by institutionalizing creativity as an organization-wide process. In this article, we suggest a multi-stage process model for understanding and implementing organizational creativity. We outline this multi-stage process in terms of different ways of gaining and using knowledge. Recognizing that individual preferences vary for different stages of the process, the article describes the Creative Problem Solving Profile (CPSP) inventory, a practical tool that helps in understanding organizational creativity as a process and serves as a method of diagnosing and solving real-world problems. We outline several real-world applications of the CPSP and suggest avenues for future research.

A NEW THEORY OF CREATIVITY AS A CIRCULAR, MULTI-STAGE PROCESS

Adaptability is driven by organizational creativity, which can be defined as a continuous process of thinking innovatively, or of finding and solving problems and implementing new solutions. Various researchers have focused on the circular nature of adaptability, or the creative process. Gordon (1956, 1971) recognized that knowledge acquisition (learning) and knowledge application (for inventing) flow continuously and sequentially into one another. Field research by Carlsson et al. (1976) supported Gordon's approach by showing that the organizational research and development (R&D) process follows a continuous, circular flow of creating new knowledge to replace old knowledge. Consistent with these findings, Basadur's field work (1974, 1983) on organization-wide deliberate change depicted the creative process as a circle, recognizing that new problems and solutions lead continuously to further problems and opportunities. Each quadrant in the circle corresponds to a specific stage of a four-stage creative process. The first two quadrants represent the components of problem finding: generation and conceptualization. The third and fourth quadrants represent problem solving (optimization) and solution implementation as the final two stages of the creative process. In each stage, people gain and use knowledge and understanding in various ways.

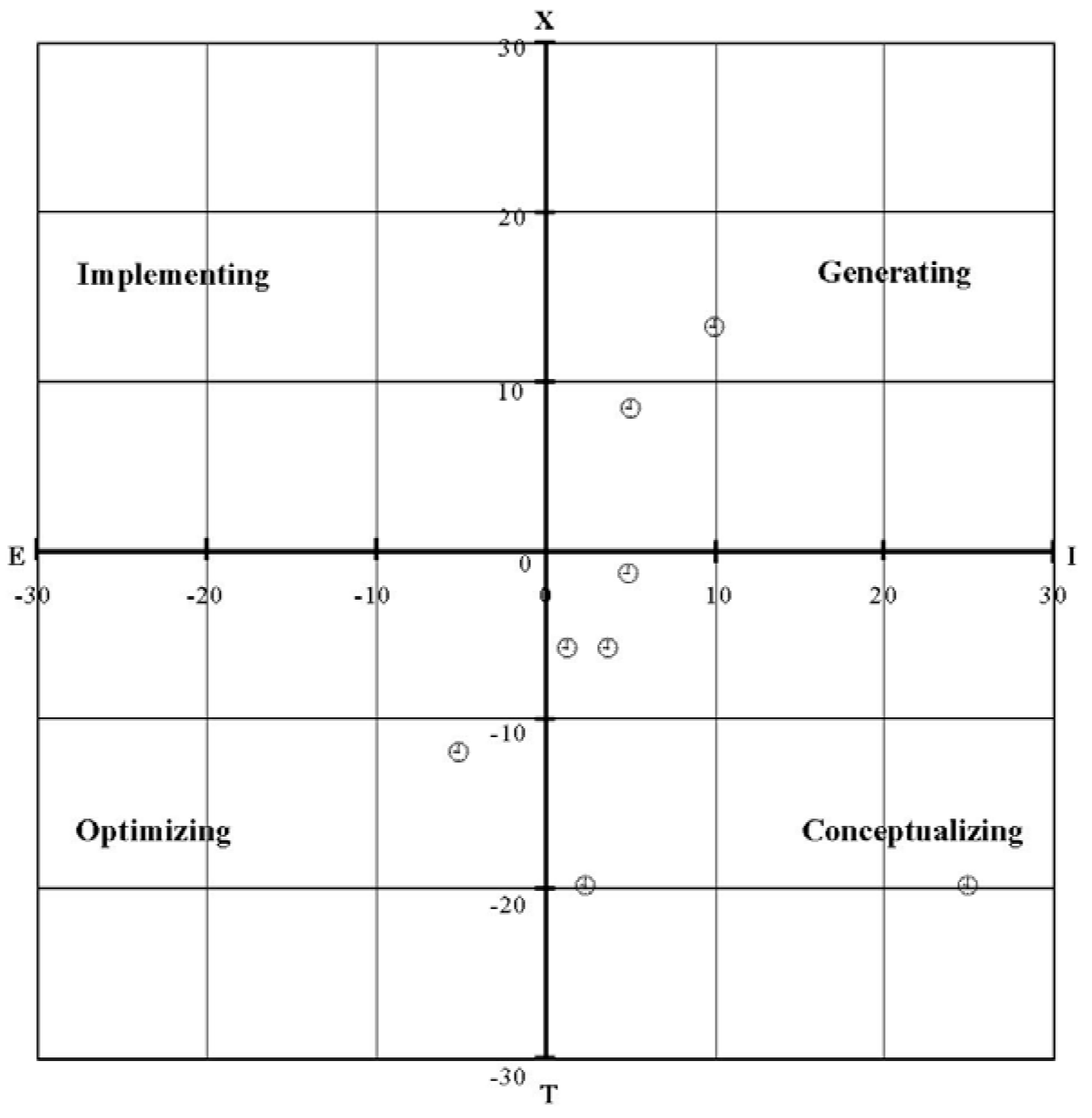

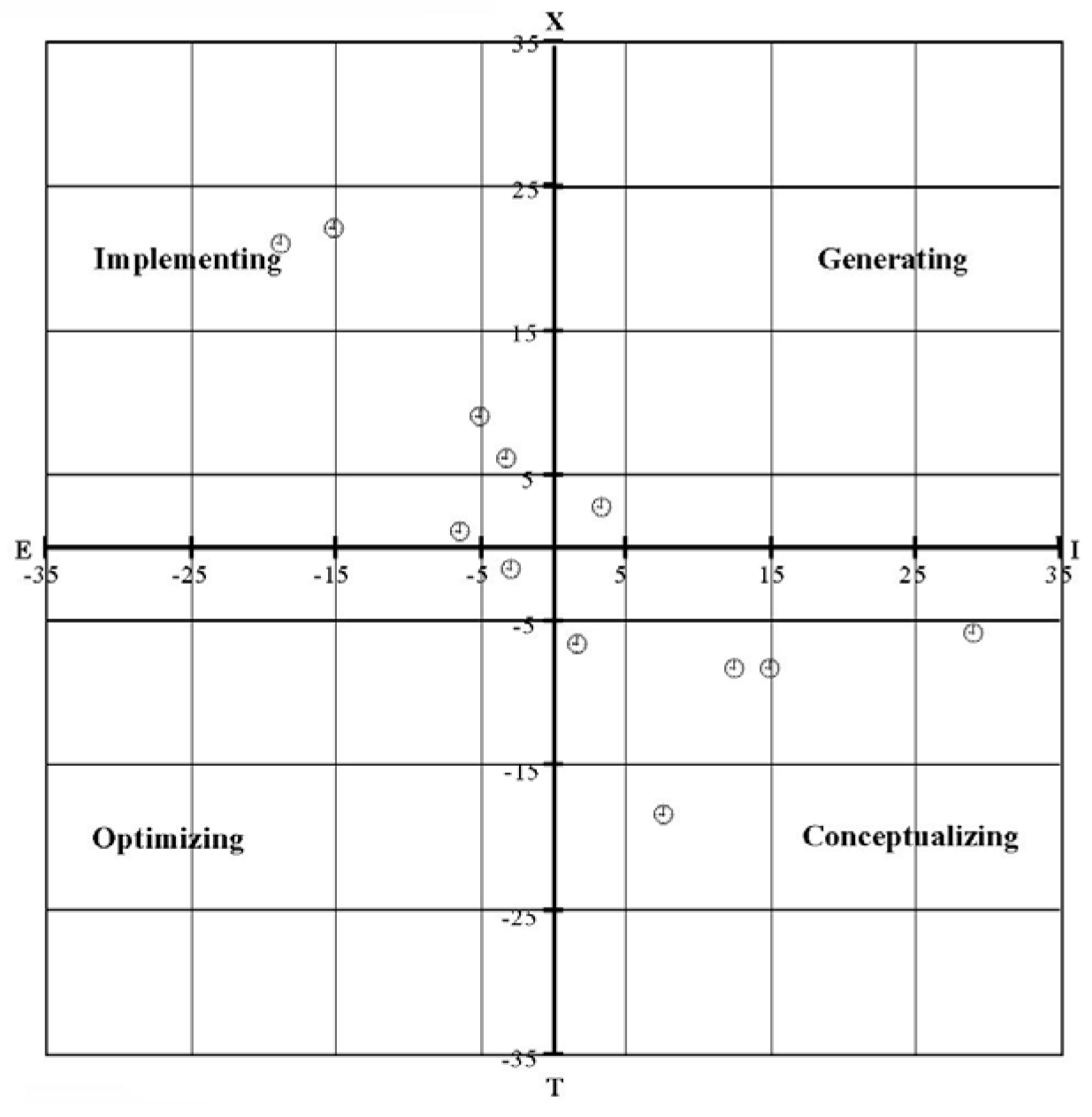

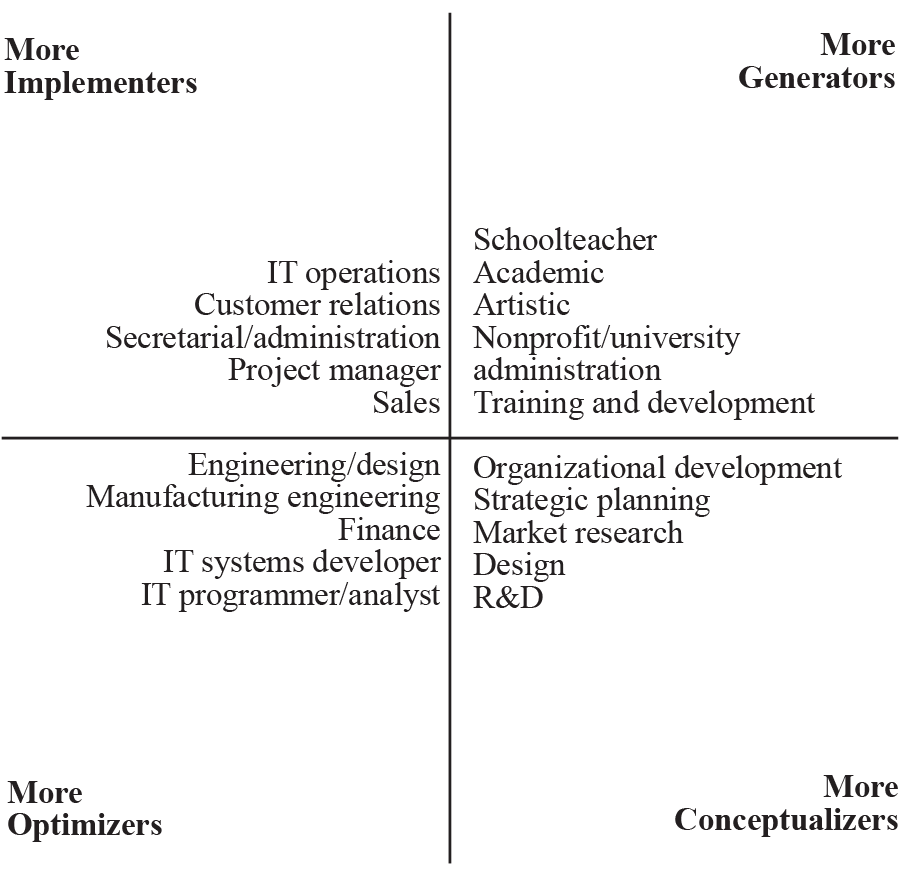

Figure 1 The four stages of the creative process

The complete process is called the Simplex Creative Problem Solving process (Figure 1). Basadur et al. (1982) demonstrated that individuals and organizations could deliberately develop skills in executing each stage of this process, and in executing the complete process. Additional field research supporting the practicality of applying this process in organizations is summarized in Basadur (1994, 2000).

THE FOUR STAGES OF CREATIVITY

Following is a brief description of the four quadrants integrating the concepts of the various researchers above.

Quadrant 1: Generating

The first quadrant gets the creative process rolling. Creative activity in this quadrant involves gaining knowledge and understanding by physical contact and involvement in real-world activities, and utilizing this knowledge to create new problems, challenges, opportunities, and projects that are potentially worth defining and undertaking through subsequent solving and implementing. Understanding is derived from what is experienced, including emotions and feelings of self and others through empathy. New possibilities are imagined from what is concretely experienced. Quadrant 1 activity thus consists of sensing, seeking, or anticipating problems and opportunities, and is called generation . An outcome of this stage is a problem worthy of investigation but not yet clearly defined or understood.

Edwin Land, in a Life magazine cover story (Callahan, 1972), told the tale of his invention of the Polaroid camera. Having snapped the last exposure on his film, he suggested to his young daughter that they take the film for processing so that they could see the pictures in about a week's time. Her frustrated response was, “Why do I have to wait a week to see my picture?” Like a flash bulb going off in his mind, her simple question sparked a challenge that had never occurred to him: “How can we make a device that yields instantaneous pictures?” Within about an hour, he had formulated several directions toward a solution. And within about four years, he had commercialized a product that has changed our lives. Looking back, the then-chairman of Polaroid said that the most important part of the process was not finding the solution itself—the camera—but finding the problem—how to get instantaneous pictures. If Land had not experienced the chance encounter, he might never have created the problem to be solved. He thus demonstrated the generation stage of the creative process: initiating problems to solve instead of waiting for problems to be provided.