Lego’s ESG dilemma: Why an abandoned plan to use recycled plastic bottles is a wake-up call for supply chain sustainability

Professor of Operations Management & Business Analytics, Carey Business School, Johns Hopkins University

Professor of Supply Chain Management, University of California, Los Angeles

Professor of Operations, Information & Technology, Stanford University

Disclosure statement

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of California, Los Angeles provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

View all partners

Lego, the world’s largest toy manufacturer , has built a reputation not only for the durability of its bricks , designed to last for decades , but also for its substantial investment in sustainability. The company has pledged US$1.4 billion to reduce carbon emissions by 2025, despite netting annual profits of just over $2 billion in 2022.

This commitment isn’t just for show. Lego sees its core customers as children and their parents, and sustainability is fundamentally about ensuring that future generations inherit a planet as hospitable as the one we enjoy today.

So it was surprising when the Financial Times reported on Sept. 25, 2023 , that Lego had pulled out of its widely publicized “ Bottles to Bricks ” initiative.

This ambitious project aimed to replace traditional Lego plastic with a new material made from recycled plastic bottles. However, when Lego assessed the project’s environmental impact throughout its supply chain, it found that producing bricks with the recycled plastic would require extra materials and energy to make them durable enough. Because this conversion process would result in higher carbon emissions, the company decided to stick with its current fossil fuel-based materials while continuing to search for more sustainable alternatives.

As experts in global supply chains and sustainability , we believe Lego’s pivot is the beginning of a larger trend toward developing sustainable solutions for entire supply chains in a circular economy. New regulations in the European Union – and expected in California – are about to speed things up.

Examining all the emissions, cradle to grave

Business leaders are increasingly integrating environmental, social and governance factors , commonly known as ESG, into their operational and strategic frameworks. But the pursuit of sustainability requires attention to the entire life cycle of a product, from its materials and manufacturing processes to its use and ultimate disposal.

The results can lead to counterintuitive outcomes, as Lego discovered.

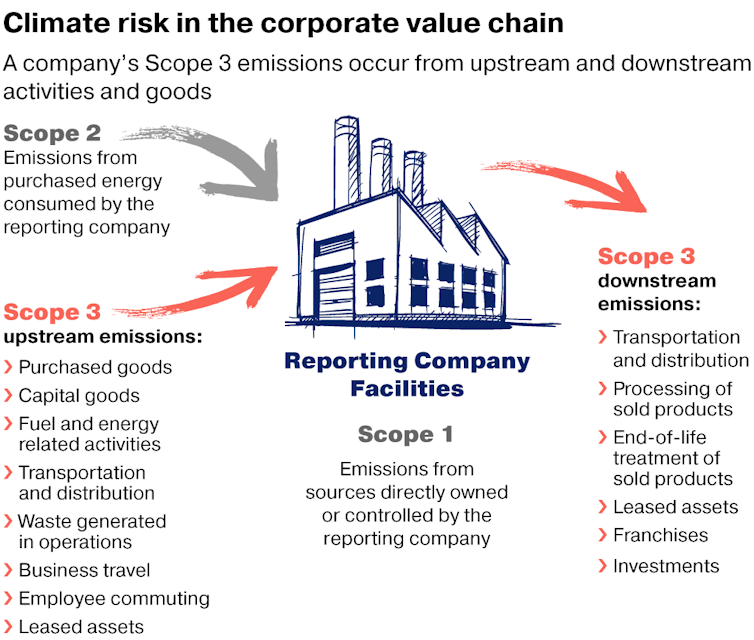

Understanding a company’s entire carbon footprint requires looking at three types of emissions : Scope 1 emissions are generated directly by a company’s internal operations. Scope 2 emissions are caused by generating the electricity, steam, heat or cooling a company consumes. And scope 3 emissions are generated by a company’s supply chain, from upstream suppliers to downstream distributors and end customers.

Currently, fewer than 30% of companies report meaningful scope 3 emissions, in part because these emissions are difficult to track. Yet, companies’ scope 3 emissions are on average 11.4 times greater than their scope 1 emissions, data from corporate disclosures reported to the nonprofit CDP show.

Lego is a case study of this lopsided distribution and the importance of tracking scope 3 emissions. A staggering 98% of Lego’s carbon emissions are categorized as scope 3.

From 2020 to 2021, the company’s total emissions increased by 30%, amid surging demand for Lego sets during the COVID-19 lockdowns – even though the company’s scope 2 emissions related to purchased energy such as electricity decreased by 40%. The increase was almost entirely in its scope 3 emissions.

As more companies follow in Lego’s footsteps and begin reporting scope 3 emissions, they will likely find themselves in the same position, realizing that efforts to reduce carbon emissions often boil down to supply chain and consumer-use emissions. And the results may force them to make some tough choices.

Policy and disclosure: The next frontier

New regulations in the European Union and pending in California are designed to increase corporate emissions transparency by including supply chain emissions.

The EU in June 2023 adopted the first set of European Sustainability Reporting Standards, which will require publicly traded companies in the EU to disclose their scope 3 emissions , starting in their reports for fiscal year 2024.

California’s legislature passed similar legislation requiring companies with revenues of more than $1 billion to disclose their scope 3 emissions. California’s governor has until Oct. 14, 2023, to consider the bill and is expected to sign it .

At the federal level, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission released a proposal in March 2022 that, if finalized, would require all public companies to report climate-related risk and emissions data, including scope 3 emissions. After receiving significant pushback , the SEC began reconsidering the scope 3 reporting rule. But SEC Chairman Gary Gensler suggested during a congressional hearing in late September 2023 that California’s move could influence federal regulators’ decision .

This increased focus on disclosure of scope 3 emissions will undoubtedly increase pressure on companies.

Because scope 3 emissions are significant, yet often not measured or reported, consumers are rightly concerned that companies that claim to have low emissions may be greenwashing without taking action to reduce emissions in their supply chains to combat climate change.

At the same time, we suspect that as more investors support sustainable investing, they may prefer to invest in companies that are transparent in disclosing all areas of emissions. Ultimately, we believe consumers, investors and governments will demand more than lip service from companies. Instead, they’ll expect companies to take actionable steps to reduce the most significant part of a company’s carbon footprint – scope 3 emissions.

A journey, not a destination

The Lego example serves as a cautionary tale in the complex ESG landscape for which most companies are not well prepared . As more companies come under scrutiny for their entire carbon footprint, we may see more instances where well-intentioned sustainability efforts run into uncomfortable truths.

This calls for a nuanced understanding of sustainability, not as a checklist of good deeds, but as a complex, ongoing process that requires vigilance, transparency and, above all, a commitment to the benefit of future generations.

- Climate change

- Sustainability

- Environmental impact

- Greenhouse gas emissions (GHG)

Data Manager

Director, Social Policy

Coordinator, Academic Advising

Head, School of Psychology

Senior Research Fellow - Women's Health Services

SustainCase – Sustainability Magazine

- trending News

- Climate News

- Collections

- case studies

Case study: How the LEGO Group promotes integrity in its operations

As a family-owned, values-based company, with products sold in more than 140 countries around the globe and over 19,000 employees, the LEGO Group aims to have a positive impact on children, society and the planet, not least by operating according to the highest ethical standards.

This case study is based on the 2016 Responsibility Report b y the LEGO Group published on the Global Reporting Initiative Sustainability Disclosure Database that can be found at this link . Through all case studies we aim to demonstrate what CSR/ sustainability reporting done responsibly means. Essentially, it means: a) identifying a company’s most important impacts on the environment, economy and society, and b) measuring, managing and changing.

With 131 LEGO Brand Retail Stores and sales offices in 37 countries, the LEGO Group is the world’s largest toy company. Operating ethically is, thus, a top priority. In order to promote integrity in its operations the LEGO Group took action to:

- promote compliance through the Corporate Compliance Board

- provide ethics training

- enhance third party due diligence

Subscribe for free and read the rest of this case study

Please subscribe to the SustainCase Newsletter to keep up to date with the latest sustainability news and gain access to over 100 case studies. These case studies demonstrate how companies are dealing responsibly with their most important impacts, building trust with their stakeholders (Identify > Measure > Manage > Change).

With this case study you will see:

- Which are the most important impacts (material issues) the LEGO Group has identified;

- How the LEGO Group proceeded with stakeholder engagement , and

- What actions were taken by the LEGO Group to promote integrity in its operations

Already Subscribed? Type your email below and click submit

What are the material issues the company has identified?

In its 2016 Responsibility Report the LEGO Group identified a range of material issues, such as product safety, climate change, waste, employee safety, the play and learning experience children get from products. Among these, promoting integrity in its operations stands out as a key material issue for the LEGO Group.

Stakeholder engagement in accordance with the GRI Standards

The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) defines the Principle of Stakeholder Inclusiveness when identifying material issues (or a company’s most important impacts) as follows:

“The organization should identify its stakeholders, and explain how it has responded to their reasonable expectations.”

Stakeholders must be consulted in the process s of identifying a company’s most important impacts and their reasonable expectations and interests must be taken into account. This is an important cornerstone for CSR / sustainability reporting done responsibly.

Key stakeholder groups the LEGO Group engages with:

How stakeholder engagement was made to identify material issues

To identify and prioritize material issues, the LEGO Group engaged with a wide range of stakeholders. They included consumers, customers, employees, NGOs, interest groups and industry associations. To achieve engagement, the LEGO Group conducted an online survey among over 1,500 respondents. Moreover, it carried out interviews with 1,500 additional participants, to identify stakeholders’ top priorities.

What actions were taken by the LEGO Group to promote integrity in its operations?

In its 2016 Responsibility Report the LEGO Group reports that it took the following actions to promote integrity in its operations:

- Promoting compliance through the Corporate Compliance Board

- The Corporate Compliance Board (CCB) is the highest decision authority regarding non-compliance issues in the LEGO Group. The CCB promotes the proper handling of ethical issues and compliance with external regulations. The CCB is also responsible for providing relevant operational guidance and reviewing policies. In 2016, the CCB reviewed the updated Responsible Marketing to Children Policy and the Digital Child Safety Policy.

- Providing ethics training

- [tweetthis] All LEGO employees participate in mandatory training on the importance of operating ethically. [/tweetthis] More specifically, the LEGO Group offers training on the LEGO Code of Ethical Business Conduct and Corruption Awareness and Competition Law e-learning programmes. Moreover, the LEGO Group reached the target of training 100% of senior business leaders bi-annually on the LEGO Code of Ethical Business Conduct. Additionally, more than 98% of salaried employees have received bi-annual training on ethical business conduct and anti-corruption principles.

- Enhancing third party due diligence

- The LEGO Group carries out integrity due diligence screenings of third parties and continually improves its third party due diligence process. The LEGO Group addresses risks holistically, including issues concerning anti-bribery and corruption, social responsibility, human rights and environmental sustainability.

Which GRI indicators/Standards have been addressed?

The GRI indicator addressed in this case is: G4-SO4: Communication and training on anti-corruption policies and procedures and the updated GRI Standard is: Disclosure 205-2 Communication and training about anti-corruption policies and procedures

78% of the world’s 250 largest companies report in accordance with the GRI Standards

SustainCase was primarily created to demonstrate, through case studies, the importance of dealing with a company’s most important impacts in a structured way, with use of the GRI Standards. To show how today’s best-run companies are achieving economic, social and environmental success – and how you can too.

Research by well-recognised institutions is clearly proving that responsible companies can look to the future with optimism .

7 GRI sustainability disclosures get you started

Any size business can start taking sustainability action

GRI, IEMA, CPD Certified Sustainability courses (2-5 days): Live Online or Classroom (venue: London School of Economics)

- Exclusive FBRH template to begin reporting from day one

- Identify your most important impacts on the Environment, Economy and People

- Formulate in group exercises your plan for action. Begin taking solid, focused, all-round sustainability action ASAP.

- Benchmarking methodology to set you on a path of continuous improvement

See upcoming training dates.

References:

1) This case study is based on published information by the LEGO Group, located at the link below. For the sake of readability, we did not use brackets or ellipses. However, we made sure that the extra or missing words did not change the report’s meaning. If you would like to quote these written sources from the original, please revert to the original on the Global Reporting Initiative’s Sustainability Disclosure Database at the link:

http://database.globalreporting.org/

2) http://www.fbrh.co.uk/en/global-reporting-initiative-gri-g4-guidelines-download-page

3) https://g4.globalreporting.org/Pages/default.aspx

4) https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/gri-standards-download-center/

Note to the LEGO Group: With each case study we send out an email requesting a comment on this case study. If you have not received such an email please contact us .

Lego’s sustainability setback highlights the complexity of cutting scope-three emissions

Lego has scrapped plans to make bricks from recycled PET bottles after discovering that the move would increase its total carbon footprint. Its experience offers useful lessons for any business

Lego recently revealed that it had abandoned a scheme to make its bricks out of recycled plastic bottles. The Danish toy maker had hoped to start using the supposedly more sustainable raw material this year, but it found from its experiments that the modified production process would have emitted more carbon dioxide than it would have saved.

Speaking to the FT , Lego’s head of sustainability, Tim Brooks, explained that “the level of disruption to the manufacturing environment was such that we needed to change everything in our factories. After all that, the carbon footprint would have been higher. It was disappointing.”

Some of the firm’s other attempts to adopt greener materials in recent years have proved successful. It has begun replacing plastic packaging with paper, for instance, and it’s been using a bioplastic sourced from sugar cane in certain bricks since 2018 . Yet its “bottles to bricks” initiative may well live longer in the memory for being abortive.

“This is the nature of innovation, especially when it comes to something as complex and ambitious as our sustainable materials programme,” Lego said in a statement. “Some things will work, others won’t.”

What can businesses learn from Lego’s experience?

Other companies would do well to view the failed scheme as a case study. Lego’s experience shows that, although certain changes might seem more sustainable at first sight, the complex nature of supply chains can obscure their true impact.

Mauro Cozzi is the co-founder and CEO of carbon footprinting platform Emitwise. He points out that “what sometimes sounds like the more sustainable option is not always one that reduces emissions. That’s because carbon footprints are inherently convoluted, with several factors at play. The tiniest changes in one of these factors can tip the entire outcome in a different direction.”

It’s important to conduct a full impact assessment of any planned sustainability initiative to assess its potential negative effects. While many companies have a good grasp of their direct impact on the environment, their scope-three greenhouse gas emissions , which include those generated by suppliers and consumers, are harder to measure.

What sometimes sounds like the more sustainable option is not always one that reduces emissions

This is problematic, because the lion’s share of most firms’ emissions falls under scope three. Take Lego, for instance: 98% of its total attributable emissions are generated in the supply chain .

Jose Arturo Garza-Reyes is professor of operations management and head of the University of Derby’s Centre for Supply Chain Improvement. He believes “it’s important that businesses take a holistic view of sustainability, just as Lego is doing. Sustainability and the reduction of carbon emissions don‘t always have a direct and positive correlation.”

Garza-Reyes continues: “Various factors – including rebound effects (increased consumption resulting from actions that increase efficiency and reduce consumer costs), technological limitations, supply chain complexities, indirect emissions and regional differences – may mean that ‘sustainable alternatives’ don’t have the desired impact.”

Given that a company tends to have little direct control over its scope-three emissions, it can find them difficult to reduce. This factor can also make it harder for a firm to gauge which operational changes would have the most beneficial effect overall.

“To build more environmentally friendly products, companies should factor in supply chain and consumer use emissions,” Garza-Reyes says. “These span the entire product lifecycle, including processes such as the extraction of raw material, customer use and disposal.”

Changes to sustainability legislation

From next year, amendments to the EU’s corporate sustainability reporting directive (CSRD) will start requiring certain businesses to disclose their scope-three emissions. The new obligation is set to apply to more than 50,000 companies, including some British firms operating in the single market.

“Adding supply chain and consumer use emissions helps businesses to recognise their true carbon impact, which allows them to make more accurate representations of their progress in carbon reduction,” Cozzi says. “This is exactly why regulations such as the CSRD require businesses like Lego to disclose these emissions.”

Updates to the UK Competition and Markets Authority’s rules concerning greenwashing add to the complexity that businesses must handle as they strive to become more sustainable.

“Having the right data to make informed, practical decisions is crucial,” Cozzi notes. “Such data has enabled Lego to avoid becoming a victim of greenhushing .”

As Lego’s experience shows, businesses must understand their products‘ lifetime impact on the environment if they‘re to achieve meaningful progress towards sustainability.

Read this next

Want to read on, subscribe to our daily newsletter.

The LEGO Group

- First Online: 30 April 2023

Cite this chapter

- Paolo Taticchi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5884-2062 9 ,

- Melissa Demartini ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3181-953X 10 &

- Melina Corvaglia-Charrey 9

Part of the book series: Springer Business Cases ((SPBC))

804 Accesses

Tim Brooks, Vice President Sustainability at The LEGO Group

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

UCL School of Management, University College London, London, UK

Paolo Taticchi & Melina Corvaglia-Charrey

Department of Technology and Innovation, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark

Melissa Demartini

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Taticchi, P., Demartini, M., Corvaglia-Charrey, M. (2023). The LEGO Group. In: Sustainable Transformation Strategy. Springer Business Cases. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-26696-6_8

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-26696-6_8

Published : 30 April 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-26695-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-26696-6

eBook Packages : Business and Management Business and Management (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Bahasa Malaysia

Show all news, opinion, videos and press releases matching →

About Eco-Business

Sustainable development goals.

- Press Releases

Lego and the toy makers: How sustainability comes to play land

In this report, we aim to research LEGO’s ESG performance when compared with other toy makers in the industry by examining their environmental (including carbon emissions), social and governance initiatives.

We evaluated LEGO’s ESG performance by referring to our ESG framework, which covers 18 initiatives of ESG reporting.

Overall, we found LEGO takes the lead in ESG reporting. In particular, LEGO has voluntarily published its sustainability since 2007 and started following GRI (Global Reporting Initiative) and assured its reports by a third party since 2009. We also found LEGO has an ambitious goal of reducing GHG emissions and controlling landfills. However, we do find that its disclosure on pollutants and risk management is missing, and overall disclosures on corporate governance are weaker than other sections.

On balance, we think LEGO’s ESG performance has the room of improvement in three areas: Consistency and comparability of disclosures, Comprehensiveness of disclosures, and Balancing attention.

Publish your content with EB Publishing

It's about who you reach. Get your news, events, jobs and thought leadership seen by those who matter to you.

Most popular

News / Energy

Wind and solar are ‘fastest-growing electricity sources in history’.

News / Transport & Logistics

Climate change is fuelling turbulence and posing threats to south asian aviation.

News / Carbon & Climate

Over 3 million hectares of malaysian forests at risk of deforestation, national forest cover commitment at risk.

Relax regional coal phase-out ambitions, Asean energy report urges

Feeling the heat: Who are the most vulnerable workers impacted by the Philippines’ record-breaking heatwaves?

News / Policy & Finance

Diversity, equity and inclusion: asia urged to look beyond gender.

Transforming Innovation for Sustainability Join the Ecosystem →

Receive the latest news in sustainability, daily or weekly.

Strategic organisations, support our independent journalism. #newsthatimpacts.

Product details

Companies / Environment

LEGO Group Ties Bonuses for All Employees to Emissions Reduction Goals

The LEGO Group announced that it will begin tying a portion of bonuses for all salaried employees to emissions reduction goals starting this year, as part of the company’s strategy to meet its climate targets.

The announcement follows the launch by the LEGO Group last year of a series of climate-related commitments , including a pledge to achieve net zero emissions by 2050, to work with the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) to develop emissions reduction targets covering Scope 1 and 2 emissions, as well as Scope 3 supply chain emissions, and to invest over $1.4 billion in environmental sustainability initiatives over the next three years. The company also pledged at the time to add a carbon KPI to executive remuneration in 2024, as well as to pursue responsible travel policies to reduce employee travel, with a particular focus on international air travel.

Under the company’s updated performance management programme, LEGO Group introduced a new KPI measuring carbon from its factories, stores and offices, as well as its Scope 3 business travel emissions. The emissions are measured against the number of bricks manufactured, to provide an intensity metric.

The company said that it aims to expand the KPI to cover Scope 3 emissions. Scope 3 emissions, or those originating in the value chain outside of the company’s direct control, account for approximately 98% of the LEGO Group’s carbon footprint.

In a social media post announcing the new KPI, LEGO Group said:

“We have an ambitious target to reduce our emissions by 37% by 2032 and achieve net zero by 2050. “To help keep us on track, from 2024, a percentage of our performance management programme for colleague bonuses will be tied to annual emissions as we take steps to reduce environmental impact across all areas of our business.”

Related Posts

Companies /

Pernod Ricard Signs Global Sustainable Packaging Agreement with Circular Economy Startup ecoSPIRITS

Environment /

Guest Post: Giving Africa a Leading Voice in the Biodiversity Battle

Google Signs its First Renewable Energy Purchase Deals in Japan

Don't miss the top ESG stories!

Join the ESG Today daily newsletter and get all the top ESG stories, like this one.

Subscribe now below!

Level C-Level SVP / EVP Director / VP Manager / Supervisor Mid or Entry Level Freelance / Contract Student / Intern Retired Other

Function Accounting & Finance Business Development & Sales Customer Support Facilities HR & Talent Investing Legal Marketing & Communications Operations Procurement & Contracting R & D Strategy Supply Chain & Distribution Sustainability Technology Other

You have Successfully Subscribed!

- Never miss the latest breaking ESG investment news. Get ESG Today’s newsletter today! Subscribe Now

Aligning Values to CSR: A LEGO Case Study

- July 17, 2020

The role of business in society is evolving – and was evolving even before COVID-19 forced companies to pivot how they engage with customers, employees and other stakeholders. How people view their relationships with work and the brands they support is changing. Sustainable Brands’ recent report, Enabling the Good Life , found that across generations people are looking for simple, more balanced lives with meaningful connections to people, communities and the environment.

Having a business model that prioritizes social responsibility, equity and inclusion, and sustainability will win favor with prospective customers and employees alike. So how should a company start to implement these programs and policies when there are so many worthwhile causes? By starting with their core values. ✨

Let’s look at LEGO as an example. LEGO’s mission is to “inspire and develop the builders of tomorrow,” which is guided by values like imagination, creativity, fun, learning, caring, and quality.

Having a well-articulated mission and set of values gives LEGO the ability to assess what sort of commitments it can and should make as a brand. In this case, LEGO has made four key promises:

People Promise 🧑🏽🤝🧑🏽 LEGO cares deeply about the people who are part of making LEGO possible, and is committed to upholding human rights and ensuring safe, healthy and respectful workplaces for our employees. This is huge – people who view their employers as good corporate citizens feel a higher sense of engagement and are more committed to their employer .

Play Promise 🧰 The company recognizes the vital role of play in a child’s development. LEGO has a unique opportunity to help children problem solve, be creative and develop resilience.

Planet Promise 🌎 LEGO is designed for children – children who will one day inherit the planet. LEGO’s promise to minimize the environmental impact of its operations not only demonstrates caring for children who love LEGO, but also the core values of creativity and quality by implementing more sustainable practices.

Partner Promise 🤝🏼 A critical component of any corporate social responsibility strategy is thinking about stakeholders beyond shareholders or investors. LEGO understands the importance of building partnerships with stakeholders like customers and suppliers in being a better corporate citizen.

These promises are embodiments of LEGO’s core values and offer a framework for how LEGO engages with stakeholders from employees and customers to the environment. This is also reflected in the three pillars of LEGO’s corporate social responsibility: children , environment and people . It’s easy to see the connection between these pillars and the brand promises LEGO has made.

Focusing on core values also gives companies the ability to evolve what CSR looks like over time. As employee and customer needs and expectations change, taking a values-based leadership approach offers greater ability to respond. LEGO’s core products are the classic bricks many of us know and love, but LEGO has more recently ventured into digital play offerings. While digital play offers children new ways to engage with the LEGO brand, there are also risks with giving children access to mobile devices. LEGO responded to this risk by taking a values-led approach – the brand’s digital experience prioritizes child safety . Beyond that, LEGO joined forces with UNICEF to develop an industry-first Digital Child Safety Policy. LEGO even helped create a tool called the ‘Child Safety Online Assessment’ to help other companies understand and address children’s rights online.

For any corporate social responsibility program to be successful, it has to be authentic to the business’ culture and principles. LEGO is just one example of walking the talk of values-aligned corporate social responsibility. We’re excited to see how even more businesses implement these types of initiatives!

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Innovating a Turnaround at LEGO

- David Robertson and Per Hjuler

Five years ago, the LEGO Group was near bankruptcy. Many of its innovation efforts—theme parks, Clikits craft sets (marketed to girls), an action figure called Galidor supported by a television show—were unprofitable or had failed outright. Today, as the overall toy market declines, LEGO’s revenues and profits are climbing, up 19% and 30% respectively in […]

Reprint: F0909B

Though the overall toy market is declining, LEGO’s revenues and profits are climbing—largely because the company revamped its innovation efforts to align with strategy.

Five years ago, the LEGO Group was near bankruptcy. Many of its innovation efforts—theme parks, Clikits craft sets (marketed to girls), an action figure called Galidor supported by a television show—were unprofitable or had failed outright. Today, as the overall toy market declines, LEGO’s revenues and profits are climbing, up 19% and 30% respectively in 2008.

- DR David Robertson ( [email protected] ) is a professor of innovation and technology management at IMD. Per Hjuler ( [email protected] ) is the LEGO Group vice president of product and marketing development. For more, visit www.innovationgovernance.net.

Partner Center

Quality, resilience, sustainability and excellence: understanding LEGO’s journey towards organisational excellence

International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences

ISSN : 1756-669X

Article publication date: 12 April 2022

Issue publication date: 10 August 2022

This study aims to reflect on quality, sustainability and resilience as emerging organisational priorities within total quality management (TQM) and organisational excellence.

Design/methodology/approach

The paper uses a conceptual approach based on reflection and theoretical studies on the philosophical foundations of quality, excellence, resilience and sustainability as cornerstones for organisational excellence. Bearing in mind that sustainable excellence rests upon a combination of systemic and soft issues that define organisational ability for resilience and sustainability, there is a need to analyse and reflect on short business cases from world-leading companies and further reflect on the fundamental principles, which have helped such companies to survive, grow and sustain. This study includes such a business case – the LEGO case. In addition, a Japanese case has been included. Japanese training material on human motivation developed in the 1980s exemplifies how company managers were trained, at that time, to understand and practice human motivation, excellence principles and tools.

Organisational excellence constitutes an evolving concept as the world becomes more chaotic and interconnected with multiple disruptive shocks. Organisational excellence challenges the inflexibilities of Newtonian mindsets, recognising the paramount importance of interactions and further underlining the significance of invisible elements such as human potentiality, motivation and values that formulate the principles of organisational excellence.

Originality/value

The paper investigates the notions of quality, resilience and sustainability and their relation to motivation and organisational excellence within the framework of business management and TQM. A world-leading company – LEGO – will be used to exemplify the theoretical findings together with the Japanese Motivation Training Programme case.

- Sustainability

Dahlgaard, J.J. and Anninos, L.N. (2022), "Quality, resilience, sustainability and excellence: understanding LEGO’s journey towards organisational excellence", International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences , Vol. 14 No. 3, pp. 465-485. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQSS-12-2021-0183

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2022, Jens Jörn Dahlgaard and Loukas N. Anninos.

Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

1. Introduction

Since the 1980s and the rebirth of management through the prism of quality, total quality and total quality management (TQM) ( Dahlgaard et al. , 1998 ), excellence has been recognised as a primary challenge for organisations following an increasing adoption of quality management systems and approaches at a global scale ( Oakland, 1999 ; Dahlgaard-Park and Dahlgaard, 2007 ; Kanji, 2008 ; Dahlgaard et al. , 2013 ).

Nowadays, in the dawn of the fourth industrial revolution, the quest for excellence continues through inspiring novel approaches that unveil new performance pillars ( Dahlgaard-Park and Dahlgaard, 2021 ) but, at the same time, it is also reminiscent of ideals or higher purposes often found in philosophical reflections of the past (coexistence, resilience and constant reconfiguration, sustainability). The so-called Quality 4.0 (aligning quality management and Industry 4.0 requirements) is about strengthening organisational capabilities with the use of technology to produce high performing products and service experiences, something that calls for new ways of managing organisations. Thriving in this brave new world demands not only the adoption of alluring technological innovations but also integration with quality teachings/theories combined with creative leadership to support innovation and agility.

More specifically, apart from focusing on a broader organisational perspective and recognising the importance of interactions (both internally and externally), the pursuit of superior performance manifests organisational resilience (the ability to recover from unexpected events and reconfigure the organisation’s business model) and orientation to sustainability (often presented as a higher purpose), as neuralgic for sustainable organisational excellence. Hence, sustainable organisational excellence refers to the capacity of organisations to maintain their outstanding performance (resulting from people doing their best and realising their full potential) and attain long-term success by taking into consideration a balanced approach on the interests of all stakeholders – customers, suppliers, employees, shareholders, the society and the environment.

In the path of its evolution, the quality philosophy has given birth to the development of several conceptual, measurement and assessment models for excellence ( Molina-Azorin et al. , 2009 ) (called Business Excellence Models ) with critical parameters and criteria for achieving and maintaining superior performance (both financial and non-financial benefits) ( Boulter et al. , 2013 ). Among the essential observations reported in some review studies on excellence models is the need to incorporate criteria for agility ( Metaxas and Koulouriotis, 2019 ), resilience and sustainability ( Asif et al. , 2011 ).

Hence, excellence models should guide organisations towards improving the performance of a current way of doing things in a given context and document, measure and evaluate organisational dynamism and resilience potential for surviving in changing circumstances and allowing the continuation of their operation in a dynamic context. Characterisations of resilient organisations include a relevant ethos, good situational awareness, commitment to identifying vulnerability sources and a culture that promotes flexibility, continuous improvements and steady innovations. In addition, sustainability concerns call for expanding the traditional notion of business excellence and a reorientation towards its philosophical essence.

This study aims to reflect on quality and excellence and investigate sustainability and resilience as emerging organisational priorities highlighted in recent Business Excellence Models (for example, the new EFQM Excellence Model) for achieving sustainable organisational excellence. A world-leading toy company – LEGO – will be used to exemplify some of our theoretical findings together with a Japanese Motivation Training Programme case.

2. The meaning of excellence and quality

The meaning of excellence has been at the cornerstone of philosophical ventures by Eastern and Western minds of the ancient world. As a word, it stems from the Latin “ Excellentia ”, a word also found in the poem Troilus and Criseyde by G. Chaucer (late 14th century) as a synonym for superiority, merit and worth .

Long time before, in the first book of the Christian Bible’s Old Testament ( Genesis 1 ), we can read how God, in six days, created our planet with all its invaluable attractive characteristics, such as light, sky, water, sea, dry ground, plants, day, night, fish, birds, animals and man . We can also read that God, after each “daily creation”, looked at it and saw that it was good (meaning that God was satisfied with all the creations). We call God’s creations excellent , namely, outstanding or extremely good , because we cannot find any better example where the word excellence can be used.

It is well known that the concept of “satisfaction” is closely related to the concept of “quality”, but how is the concept “excellence” related to “quality”? The answer to that question is, in principle, straightforward, and most people will come up with the same response as found in the Oxford Dictionary, which considers excellence synonymous with being outstanding, extremely good.

A more precise or more down to earth description/definition of excellence is not an easy task; nevertheless, it is desirable for knowing the degree of its attainment ( Dahlgaard-Park, 2009 ). However, there can only be a general description of the term as an attempt for a thorough definition would be unwise due to the nature of the human mind. The challenge is the perception of “Good”, which is the core of excellence, the spirit of quality and the evolution of life ( Anninos, 2019 ). Hence, a comprehensive general understanding of the meaning of excellence is neither a simple nor a straightforward task. It presupposes intellectual whereabouts, namely, contemplating and reflecting on the meaning of quality, which refers to attractive characteristics that define value.

A draft definition of quality (most probably the first time that quality as a term appears in ancient Greek literature) is present in Plato’s dialogue “Theaetetus”, in which Socrates (470–399 BC) discusses with Theodore (a mathematician) and his student (Theaetetus) the nature of knowledge (see Plato: Theaetetus 182a,b; Hamilton and Cairns, 1961 ). Socrates describes quality as an extraordinary word that someone cannot understand when it is used generally . He makes a distinction between the active and the passive elements of things, the union of which gives birth to perceptions and the perceived things; thus, the one acquires some quality (a property) while the other element becomes percipient.

Regarding the meaning and definition of quality in the context of quality management, we can now look back on almost 100 years of evolution, starting in 1924 were the father of modern quality control , Walther A. Shewhart (1891–1967), had developed the so-called Statistical Control Charts , the theory of which became the main contribution for understanding, measuring and controlling product quality .

Walther A. Shewhart discussed and defined quality in his doctoral thesis from 1931 as follows ( Shewhart, 1931 , chapter 6, pp. 37–54) and at the beginning (p. 37), we can read about a Popular Conception of Quality :

Dating at least from the time of Aristotle (384-323 BC), there has been a tendency to conceive of quality as indicating the goodness of an object. The majority of advertisers appeal to the public on the basis of the quality of product. In so doing, they implicitly assume that there is a measure of goodness which can be applied to all kinds of products whether it be vacuum tubes, sewing machines, automobiles, grape nuts, books, cypress flooring, Indiana limestone, or correspondence school courses. Such a concept, is, however, too indefinite for practical purposes.

After this warning to use popular conceptions of quality for all practical purposes Shewhart comes up with his definition of quality comprising its two dimensions – objective quality (properties or attributes of the product, independent of what the consumer wants) and subjective (customers` requirements, expectations, experiences, etc.) quality .

Because a product, according to Shewhart, has an infinite number of attributes, then it is impossible to have expectations and experiences with all product attributes. In practice, the customer will only look at the most important ones or they will only look at the whole product without specifying too much in advance what kind of expectations they have when buying the product.

So, quality may have different expressions, meanings and importance for different people/customers depending on which product’s attributes are most important for each specific customer, and also because, even if two customers may declare that the same attributes are essential for both of them, it is unlikely that different customers will rate the same attributes in the same way.

Shewhart`s pioneering work laid the foundation for the new science about quality, Quality Sciences , and during the following 90 years, many researchers and consultants came up with new definitions of quality based more or less on Shewhart’s pioneering work.

W. Edwards Deming (1900–1993) discussed the definition of quality as follows ( Dahlgaard and Dahlgaard-Park, 2015 ):

The difficulty in defining quality is to translate future needs of the user into measurable characteristics, so that a product can be designed and turned out to give satisfaction at a price that the user will pay. This is not easy, and as soon as one feels successful in the endeavour, he finds that the needs of the consumer have changed, competitors have moved in, there are new materials to work with, some better than the old ones, some worse; some cheaper than the old ones, some dearer […].

Deming did not come up with a clear quality definition, but instead, he focused on the dynamics of quality, meaning that what is good quality today will, in most cases, not be good quality tomorrow. With that background, it is easy to understand that the first of Deming’s 14 Points ( Deming, 1986 ; Dahlgaard and Kristensen, 1992 ; Dahlgaard et al. ,1994 ) is about the continuous product and service improvements ensuring quality and minimising loss of business to competitors. Deming always said that: “the consumer is the most important part of the production line” ( Deming, 1986 ), meaning that without understanding customers` and/or consumers’ needs, expectations, requirements and experiences, then it is impossible to understand what is quality for a specific consumer, and hence it is difficult to produce and deliver high-quality products and services. By saying that “quality can be defined only in terms of the agent”, Deming also stressed that quality has many definitions and expressions depending on the context.

the product features that meet customer needs; and

freedom from deficiencies ( Dahlgaard and Dahlgaard-Park, 2015 ).

According to Juran, this dual meaning of quality helps us to explain why so many meetings to discuss managing for quality have ended in confusion.

Kaoru Ishikawa (1915–1989), a Japanese Professor and quality expert, discussed the definitions of quality in a way that is related to everything (e.g. quality of work, quality of the process and quality of people) in a company setting ( Dahlgaard and Dahlgaard-Park, 2015 ). Company-Wide Quality Control (CWQC), which was developed and became successful in Japan during the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, illuminates Ishikawa’s thoughts on the Japanese way of quality management.

So, as said above, quality has many expressions, meanings and definitions depending on the context or reference level, and the above quality pioneers’ definitions vary because their reference levels were not the same.

Hence, excellence also has multiple expressions and meanings according to different reference levels (e.g. science, philosophy) and specialization levels (e.g. individual, organisational), while it mainly emphasizes perfection and human enlightenment ( Anninos, 2007 ).

Approaching the term or concept of excellence from a teleological perspective, it refers to an intended situation achieved by the degree of a subject’s or an object’s quality that determines its capacity to fulfil its role. The core of quality is “Good”, while quality itself is the heart of excellence (left part of Figure 1 ). Thus, the more a subject’s quality improves, the closer excellence approaches, which then again leads to higher quality ( Anninos, 2007 ). Hence, we have chosen to portray the interrelationship of these two concepts with two circles side by side, forming the symbol of infinity (right part of Figure 1 ), indicating that The Quality Journey is a Journey without an End ( Dahlgaard et al. , 1994 ).

Thus, according to Figure 1 , excellence presupposes quality and quality presupposes excellence in a dynamic interrelationship. People cannot realise their full potential (excellence) without doing their best (quality), and for this to happen (quality), they need a particular state of mind (excellence) ( Dahlgaard-Park et al. , 2013 ).

To complement Figure 1 , we have taken as an example the old Chinese/Japanese written expression of Kaizen , which means a change for the good (Kai = change, Zen = Good). The left kanji symbol of Kaizen symbolises the struggle for changing oneself, and the right Kanji symbol represents the necessary sacrifices that are needed for improvement ( Figure 2 ).

The concept of Kaizen became well known worldwide because the Japanese companies used that concept, especially from the beginning of the 1960s, to conquer the world markets by using the concept of CWQC . The best Japanese companies showed, especially during the 1980s, the importance of using the strategy of continuous quality improvements literally company-wide. This strategy became synonymous with the Japanese Way to Excellence . However, before the success of Kaizen in Japanese companies, there were also some examples in the West, companies that experienced steady progress when building up a culture based on continuous improvements (Kaizen). Such a company is the Danish toy company LEGO.

3. LEGO case: Part 1

3.1 methodology.

All references/quotations to LEGO in this article can be found on LEGO’s website, where key milestones of LEGO History have been told. We will not in this article evaluate the LEGO History seen with the traditional scientific glasses, which we normally do when writing research articles with one or more case studies included. We will only focus on what the founder and his successors have agreed on that has worked very well during LEGO’s History and which they implicitly agreed on as so important principles that they can be regarded as key building blocks to explain and hence understand the LEGO History from LEGO’s foundation until today. What we found on the LEGO website was then analysed carefully to identify an unknown number of excellence principles, which we regard as important to understand the history and also for running the company today. However, we could not find anything on the LEGO website to understand why LEGO had a severe economic crisis from about 1997 to 2005. When we digged deeper into the literature and the yearly financial reports, we could identify an 11th excellence principle important to understand the economic crisis and also important for preventing or reducing the risks that unexpected events may happen in the future – clearly a resilience principle.

We have, as an important check, shared our evaluations and findings with the owner and previous CEO of LEGO, Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen, who is the top leader and stakeholder who directly and indirectly has experienced most of the analysed LEGO’s History. We are happy that the feedback through his secretary was positive, as there were no objections to go further with publishing our article in a research journal. With this explanation on how we worked with the LEGO History, we will now go through the parts of the LEGO History which we found important for identifying 10 + 1 excellence principles.

3.2 LEGO’s first excellence principles

The LEGO Group was founded in 1932 by Ole Kirk Christiansen, whose personality, character and decisions have considerably impacted LEGO History. The name “LEGO” is an abbreviation of the two Danish words LEG GODT, which mean play well , and LEGO employees are proud to say, “It is our name, and it’s our ideal”.

LEGO decided, in 1935, on the company name without knowing that in Latin, the word LEGO means “I put together”. Therefore, LEGO’s success rests on two simple, ingenious product development principles or aims signalling to all concerned that the development of the toy should allow children to play well by putting bricks together . The LEGO plastic brick is by LEGO regarded as the company’s most important product.

The company has passed from father to son and is now (2022) owned by Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen, a grandchild of the founder. Today the company has become the world’s biggest toy producer, so it is easy for us to conclude that LEGO is an example of an excellent company .

How can a small company established in 1932 in a very small town (Billund) in a very small country (Denmark) develop into the world’s biggest toy producer?

What are the secrets behind this success?

To answer this question simply is not easy because the answer will require a book or several books, which have already been written and published. However, in this article, we only have the space to come up with simple answers. Hence, we tried to find some of the basic principles, which were important for the founder and his few employees from the very start in 1932 and which are still excellence principles or core values or commands in the LEGO Company.

So far, we have identified the first two excellent product development principles ( play well by putting bricks together ), which since the 1930s have laid the foundation for what LEGO should develop and produce.

The third excellence principle we found when we studied the LEGO History website was

“DET BEDSTE ER IKKE FOR GODT”

“Only the Best is Good Enough”.

This essential and also simple principle was carved in wood back in the 1930s (see Figure 3 ) and put on a central place in the very small company so that everybody did not forget it and maybe reflected on it day by day during their operational tasks. Perhaps some of the employees discussed the deep meaning with their colleagues and, of course, also with the founder Ole Kirk Christiansen.

The meaning of LEGO’s third excellence principle was and still is that you should always strive to produce and deliver “the best”, even if some people may say that the best is too good for the specific market/customer.

Another and complementary meaning is that when you have found “a best solution” to a design problem, a process problem, a marketing problem, etc., then people should understand that what is the best today will not be the best tomorrow or the best for new markets. So, employees should always try to look for better solutions relative to the expected future challenges related to competition, cost-effectiveness, new products, etc. This second meaning was revolutionary at that time at the end of the big world economic crisis in 1932. It was, in fact, an argument to immediately start and continue with improvements in the quality of products and the related production processes.

About this third excellence principle, we found the following details behind on the LEGO history website:

Ole Kirk Christiansen has always guaranteed the quality of his work, something he continues to do in his work with wooden toys. He is convinced that children deserve toys of high quality, made of the finest materials, so that they will last for many years of play. He uses beech wood, which is first air-dried for two years, then kiln-dried for three weeks. It is then cut, sanded, polished and given three coats of varnish or paint. Just like real furniture. Ole Kirk Christiansen demands quality at every stage of the process, especially from his own children.

Son Godtfred Kirk Christiansen once took a consignment of painted wooden ducks to the railway station. Back at the factory, he proudly tells his father he's done something really clever and saved the company money. “How did you manage that?” asks Ole Kirk Christiansen. “I gave the ducks just two coats of varnish, not three as we usually do!” Back comes his father’s prompt response: “You’ll immediately fetch those ducks back, give them the last coat of varnish, pack them and return them to the station! AND you’ll do it on your own - even if it takes you all night!”. “That taught me a lesson about quality,” says Godtfred Kirk Christiansen on a later occasion.

After the lesson, Godtfred carves out wooden signs of the company motto “Only the best is good enough” and hangs them on the wall of the factory to remind employees of the company's attitude to quality.

In the preface of his book from 1996 about Godtfred Kirk Christiansen, Jan Cortzen calls him one of the greatest entrepreneurs in Denmark during the 20th century.

From the start in 1932 until today, 90 years after the company’s foundation, we can understand that quality became one of the LEGO Group’s principles/values, as we can read on the LEGO History website:

Quality in every detail:

Quality is and has always been one of LEGO Group’s values. It permeates everything we do and shines through in the company motto: Only the best is good enough.

Hence, we have identified the fourth excellence principle:

Quality should be part of every detail.

Consequently, we can say that the founder of LEGO, Ole Kirk Christiansen, showed in the early years of LEGO strong leadership capabilities related to all forms of improvements, and he also expected “his” employees to participate in Continuous Improvement Processes maybe 30 years before the Japanese companies, such as TOYOTA, decided to invite employees company-wide to participate with Kaizen ideas and improvements.

LEGO gradually set up the continuous improvement processes in the LEGO way based on the humble, respectful and also open culture which characterised people in and around the small town of Billund. Ole Kirk Christiansen and his employees had never heard about Kaizen, but they did use the Kaizen principles in the LEGO Way.

4. Excellence as “quality ad infinitum” and managerial pursuit

The concept of Kaizen became well known in the West during the 1980s when western companies tried to find the secret(s) of the leading Japanese companies such as Toyota, Sony, Matsushita and Sumitomo Electric Industries, and where Toyota especially was studied heavily. Initially, the studies focused on understanding the concept of Kaizen, and gradually, the studies extended into much broader frameworks such as CWQC, TQM and Business Excellence principles and models ( Deming, 1986 ; Imai , 1986, 1997 ; Ishikawa, 1989 ; Kondo , 1989, 1993 ; Womack et al. , 1990 ; Liker, 2004 ; Liker and Hoseus, 2008 ; Dahlgaard et al. , 1998 ). The broadening of the Business Excellence Models/Frameworks had an indirect assumption and a shared principle/criteria built-in, that continuous quality improvements everywhere inside the company as well as outside in all stakeholder relations was the gate and road to excellence ; or said in another way, “Quality ad Infinitum” leads to excellence .

The concept of excellence in management has been introduced (in an indirect way) by Peters and Waterman (1982) , with the publication of their book “In search of excellence – lessons from America’s best-run companies”. They offered evidence of the best results achieved based on the specific “7S managerial parameters” grouped into hardware parameters: structure; strategy; and software parameters: systems; shared values; skills; staff; style . During their study, Peters and Waterman observed that ( Dahlgaard-Park and Dahlgaard, 2007 , pp. 371–372):

Managers are getting more done if they pay attention with seven S's instead of just two (the hardware criteria), and real change in large institutions is a function of how management understand and handle the complexities of the 7- S model. Peters and Waterman also reminded the world of professional managers that soft is hard meaning that it is the software criteria of the model which often are overlooked and which should have the highest focus when embarking on the journey to excellence.

The excellent companies were, above all, brilliant on the basics. Tools didn’t substitute for thinking […].

Rather, these companies worked hard to keep things simple in a complex world.

They persisted. They insisted on top quality. They fawned their customers. They listened to their employees and treated them like adults.

Dahlgaard-Park and Dahlgaard commented on the above observations (op cit. p. 372):

We know today that many of the excellent companies (US Best-Run Companies) identified in the studies by Peters and Waterman later on became un-successful. This observation tells us what should be obvious that any model and/or lists of attributes have limitations, because they are always simplifications of reality (the context) in which the companies are operating. Hence, the observation also tells us that there is a need to analyze Peters and Waterman's findings and to compare with later excellence models which may have been designed in response to the problems and new knowledge acquired when companies have struggled to adopt or adapt early versions of excellence models and/or lists of excellence attributes.

Peters and Waterman were accused by many that their findings and recommendations in their 1982 book were oversimplified, but the answer to those accusations came in their 1985 book ( Peters and Austin, 1985 ):

“Many accused ‘In Search of Excellence’ of oversimplifying. After hundreds of post-In Search of Excellence seminars, we have reached the opposite conclusion: ‘In Search of Excellence’ didn’t simplify enough!”

PEOPLE who practice;

Care of CUSTOMERS;

Constant INNOVATION; and

LEADERSHIP, which binds together the first three factors by using MBWA (Management by Wandering Around) at all levels of organisations.

Based on the four critical success factors of excellence, the authors simplified further with the following model of excellence ( Figure 4 ).

We accept that this model is a simplification, but we have also to admit that we like it because the model signals in a powerful way that excellence is impossible to attain without committed leadership with a high focus on the critical factors of motivation, training, educating and involving employees in continuous improvements related to care of customers and constant innovation.

The idea that quality forms the foundation for excellence in management can be ascribed to Deming (1986 ), and this presupposes a systemic view of the organisation, a set of values that develops and supports highly engaged people and a constant orientation to continuous improvement and learning. Based on that, we may theorise excellence , as quality (as a dominating value), in a present quality level , for (better) quality (higher level of quality) ( Anninos, 2007 ), while viewed through twin lenses, namely, activity and results ( Hermel and Ramis-Pujol, 2003 ). In other words, excellence is a corporate value, a purpose, a mindset of doing business aiming at the highest performance in predefined dimensions.

As it has been suggested by Dahlgaard and Dahlgaard-Park, organisational excellence comes as a logical consequence of people’s (individual and collective) attempts for excellence ( Dahlgaard-Park, 2009 ; Dahlgaard-Park and Dahlgaard, 2007 ), which has its mental (e.g. core values), managerial (e.g. practices) and technical (e.g. process, systemic) prerequisites ( Dahlgaard-Park and Dahlgaard, 2010 ).

5. Excellence, sustainability and resilience

The achievement of excellence relies on crafting a suitable organisational reality through the combination and interactions of certain constituents in a given context. Structures (dynamic interrelationships among processes and factors) are flexible and constantly evolving, serving the achievement of specific goals and outcomes. After achieving these goals and results, structures may transform. Within these structures, organisational interactions facilitate the enrichment and pursuit of excellence even when unexpected events appear. Based on the description of excellence, one understands that excellence can only be sustainable because excellence will, per definition, maintain a balance among its various constituents in time while evolving; otherwise, the state of excellence cannot be attained.

Managers have the know-how, quality tools and resources for crafting and fine-tuning efficient and waste-free systems, developing and implementing an agile strategy for directing the operation of organic structures based on a purpose encompassing vision. It is also important to suggest that it is impossible to solve sustainability problems or resilience issues through a monocular/unilateral organisational approach that places the economic/business interests above all.

The ability of organisations to continuously search and exploit business opportunities and translate them into sustainable competitive advantages for long-term value is consistent with the excellence idea and is corroborated by evidence that proves that strategic orientation has a positive impact on performance ( Rauch et al. , 2009 ).

According to Lengnick-Hall et al. (2011) , a resilient organisation is recognised by its capacity to rebound from disruptive and unprecedented events and develop new capabilities (e.g. situational awareness, low vulnerability to systematic risks ( Burnard and Bhamra, 2011 ) to keep pace with changes and create new opportunities ( Hamel and Valikangas, 2003 ; Jamrog et al. , 2006 ). Otherwise stated, it is an organisation that can productively respond to the changes that disrupt the expected pattern of events without engaging in harmful behaviours ( Horne and Orr, 1998 ).

Expectations on resilient organisations include adequate and timely resources to support new strategic directions . These resources often presuppose alliances or other types of strategic partnerships. Still, irrespectively of their source, they allow some kind of safety against disruptive events and possible formation of alternative responses. By systemic thinking, an organisation may predict its likely future, transforming its people into learners who continuously scan the environment to track signs for change.

the cognitive challenge (awareness and understanding of change and the need for transformation);

the strategic challenge (formulating alternatives);

the political challenge (focusing on future needs for products/services and using resources); and

the ideological challenge (thinking beyond the current state/model of operational excellence).

Such a fluid or agile strategy complements flexibility in systemic operation, thus creating stronger foundations for resilience and sustainability. At the same time, it requires disentanglement from past solutions, best practices and deliverance from the disorders of complacency often combined with a delusion of invincibility and perpetual excellence.

Moreover, strategic human resource management should build trust, empowerment, a climate of positive psychology and support for personal growth, which will serve as an alignment mechanism of people to organisational resilience ( Mitsakis, 2019 ). A people-centred culture should unite everyone under the shared vision for excellence.

Andersson et al. (2019) , in their Handelsbanken case study, concluded that among preparations for disruptive events, the issues of power distribution and collective leadership have been highly significant. The diffusion of power, the replacement of traditional hierarchical control from self-organisation combined with individual accountability, is associated with the creation of resilience ( Lengnick-Hall et al. , 2011 ), but at the same time, constitute core elements of quality management. Leaders are expected to be adaptive, design organisational mechanisms for assuring adaptation of people and, of course, undertake the task of cultivating the appropriate culture (collaboration built around trust and sharing, partnerships, flexibility and strategic intelligence) ( Grote, 2019 ). Hence, the importance of leaders, their behavioural patterns for influencing followers, their understanding of each person’s uniqueness, learning abilities and motivation are of utmost importance for creating working environments that will allow people to optimise their contributions for excellence.

Management is generally not regulated by foreordained laws, but it is precisely its relationship with philosophical thinking that emphatically underlines that there is no excellence without resilience and sustainability orientation , simply because excellence entails balance, harmony and long-term survival. It is not possible for an organization to be excellent and neglect corporate responsibility issues and/or business ethics or even be unable to discern the factors that will grant it resilience.

The most crucial requirement for business in a globalised volatile context is sustainable excellence . Excellence cannot be restrained strictly into the frontiers of an organisation. Still, it relates largely with the organisational impact on society, as it is impossible to be excellent and at the same time disregard possible externalities and ethical misconduct in business practice. In that sense, we can say that “we have a DREAM ”, which accentuate Daring, Responsible, Ethical, Agile and Mindful academics and practitioners to reinvigorate excellence, bearing in mind the Aristotelian eudaimonia (the highest and noblest human purpose that presupposes virtuous living) and the Japanese kyosei philosophy (a spirit of cooperation among people in organisations working towards the common good).

Regarding the importance of dreaming, caring, risking, dreaming and expecting , we also refer to the following perspective on the meaning of excellence ( Dahlgaard-Park, 2009 ):

Excellence may be attained if one: Cares more than others think is wise; Risks more than others think is safe; Dreams more than others think is practical; and Expects more than others think is possible.

The author concludes that attaining and sustaining excellence is a never-ending journey, a way of doing, a form of living, a process of becoming that has meaning in personal, organisational as well as in global settings.

6. Human motivation training, excellence and resilience

Regarding the handling of unexpected problems that companies often encounter, we will primarily refer to Kondo (1989 , p. 177) and Dahlgaard-Park (2002) , where the authors present and discuss a human motivation study course developed in Japan in the 1980s by the Japanese Standards Association’s Motivation Research Group which was led by the late Professor Yoshio Kondo. The research group studied motivation both theoretically and in several practical cases, for instance , the case of the Wright brothers’ experiences with inventing the airplane, and the explorer Roald Amundsen and his team’s experiences during the competition to become the first man to conquer the Antarctic and to reach the South Pole. By studying such cases and by comparing them with the new challenges of business corporations, they could conclude that:

In times of great change, the people who matter will not be those who search for stability, but those who can accept instability and are flexible enough to find their balance (Kondo, op cit. p. 171).

By comparing their findings with Japanese companies’ new challenges and motivation needs, the motivation study group developed the human motivation study course as an intensive training programme for top and middle managers. The training course material was later translated into Danish and tested in a number of Danish companies as well as tested by TQM master students at the Aarhus School of Business from 1992 to 2000 ( Dahlgaard-Park, 2002 ) where Professor Yoshio Kondo supervised the course to ensure consistent methodology with Japanese classes.

The overall aim of this course was to prepare managers and their employees to be able to respond to change . The more detailed aims were (Kondo, op cit. p. 175) “to help people study motivation through on-the-job training and find out what they must do in order to practice it more effectively”.

Figure 5 below describes The Human Motivation Training course structure.

Motivation rests on three pillars mounted on a solid base, which represents self-development. Self-motivation should always come first before motivating subordinates, team members, superiors and senior colleagues.

The first pillar is “getting the job done” (thinking about completing a large/difficult task).

The second pillar is “building teamwork” (team working is vital), and the third pillar is “rousing the will to work” (making people desire to do something). The pillars support the roof representing motivation.

Decide to do the project.

Create a sense of urgency – the project must be accomplished.

Think positively – be convinced of success.

Investigate and prepare thoroughly.

Draw on people’s inner resources and give freedom in methods.

Be prepared for the unexpected to happen.

Reflect on progress and turn disasters into successes.

In this article, we will only show and discuss the first pillar shortly because the seven tools of this pillar were most challenging for the Danish managers as well as the master students, and also because some tools in the first pillar were highly relevant to discuss, understand, and hence practice (meaning for building resilient, sustainable and excellent organisations). Primarily tool number six (“be prepared for the unexpected to happen”) opened the eyes for managers as well as for the master’s students that building resilient and sustainable organisations is not a problematic theoretical issue but a rather practical down-to-earth challenge which all participants actively could discuss after the course instructor had presented the tool.

In the next section, we will discuss tool six further concerning LEGO’s economic crisis at the beginning of the 2000s.

7. LEGO case: Part 2

7.1 lego’s excellence principles for achieving and sustaining excellence.

The previous section A above about LEGO’s foundation and the excellence principles identified from LEGO history (1932 to 1957) identified four excellence principles. The first two ( play well, put bricks together ) refer to the product; hence we call them LEGO’s two excellent product development principles. The third and fourth principles (only the best is good enough, quality is in all details) are related to product development, design and production. They have close relations to the KAIZEN philosophy, meaning that everything can and should change for the better .

When employees gradually internalise the third and the fourth excellence principles concerning product and product development, after a while, people realise the broader value of these principles in other processes. The result is that employees begin to practice those principles wider in the company and ultimately in external processes.

Create a creative organisation; and

Everybody’s creative ideas are necessary for continuous improvement processes.

After a “crucial decision” only to develop, produce and sell products based on the LEGO Brick, the company began to grow. This decision emphasised the company rules and values. Following the crucial decision to concentrate all efforts on the LEGO System in Play in 1960, Godtfred Kirk Christiansen laid down a company rule that:

No one must be able to do this better than us.

In addition, he outlines developments so far:

We know our idea is a good one. We want only the best, and we must make better bricks from even better material on even better machinery. We must get the best people that money can buy for our company.

We aspire to become the best in all we do; and

We must hire, develop and keep the best people that money can buy.

From the early 2000, the LEGO Group moved closer to its customers by developing new ways of communicating and engaging with them. It moreover used the value of crowdsourcing when the company partnered with the Japanese platform CUUSOO, and in 2008, developed the LEGO CUUSOO initiative and invited its fan designers to submit their ideas for new products. The LEGO CUUSOO platform has been successful and expanded globally. It resulted in the birth of LEGO Ideas in 2014 (a community-based innovation initiative). However, both of them were not the first examples used by LEGO to engage customers in product development. Tormod Askildsen (Head of AFOL Engagement) said that “The LEGO brick is a language to express ideas and tell stories, and there are billions of ideas to be shared and stories to be told” and recognised the importance of crowdsourcing.

Invite consumers through crowdsourcing to come up with ideas for new products.

In the mid-2000, however, LEGO was also in a deep economic crisis, searching for ways to face its difficulties. This financial crisis led the company to outsource a substantial part of LEGO’s production to Flextronics, but problems soon arose concerning meeting the increasing customer demand. Hence, after a while, the company decided to terminate the partnership. Bali Padda, LEGO’s Group Chief Operating Officer, said in 2012 that:

The all-important thing we learned is that one should know what is the core competence of a company. The molding of bricks is a core competence, and that we should not hand over.

It seems that outsourcing was not the solution to the serious economic difficulties and outsourcing had to be followed by insourcing.

Don’t outsource a core competence; it is the company’s most valuable asset!