- A-Z Publications

- Annual Review of Clinical Psychology

Annual Review of Clinical Psychology - Current Issue

- Navigate this Journal

- Early Publication

Previous Volumes

- Editorial Committee

Volume 19, 2023

A clinical psychologist who studies alcohol.

In this article, I describe why I believe the study of alcohol use and its consequences is a rich and rewarding area of scholarly activity that touches on multiple disciplines in the life sciences, the behavioral sciences, and the humanities. I then detail the circuitous path I took to become an alcohol researcher and the various challenges I encountered when starting up my research program at the University of Missouri. A major theme of my journey has been my good fortune encountering generous, brilliant scholars who took an interest in me and my career and who helped guide and assist me over the course of my career. I also highlight selected, other professional activities I've been involved in, focusing on editorial work, quality assurance, and governance of professional societies. While the focus is on my training and work as a psychologist, the overarching theme is the interpersonal context that nurtures careers.

- Add to my favorites Favourites

Community Mental Health Services for American Indians and Alaska Natives: Reconciling Evidence-Based Practice and Alter-Native Psy-ence

This review updates and extends Gone & Trimble's (2012) prior review of American Indian (AI) and Alaska Native (AN) mental health. First, it defines AI/AN populations in the USA, with an explanation of the importance of political citizenship in semisovereign Tribal Nations as primary for categorizing this population. Second, it presents an updated summary of what is known about AI/AN mental health, with careful notation of recurrent findings concerning community inequities in addiction, trauma, and suicide. Third, this article reviews key literature about AI/AN community mental health services appearing since 2010, including six randomized controlled trials of recognizable mental health treatments. Finally, it reimagines the AI/AN mental health enterprise in response to an “alter-Native psy-ence,” which recasts prevalent mental health conditions as postcolonial pathologies and harnesses postcolonial meaning-making through Indigenized therapeutic interventions. Ultimately, AI/AN Tribal Nations must determine for themselves how to adopt, adapt, integrate, or refuse specific mental health treatments and services for wider community benefit.

Culturally Responsive Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Ethnically Diverse Populations

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is often referred to as the “gold standard” treatment for mental health problems, given the large body of evidence supporting its efficacy. However, there are persistent questions about the generalizability of CBTs to culturally diverse populations and whether culturally sensitive approaches are warranted. In this review, we synthesize the literature on CBT for ethnic minorities, with an emphasis on randomized trials that address cultural sensitivity within the context of CBT. In general, we find that CBT is effective for ethnic minorities with diverse mental health problems, although nonsignificant trends suggest that CBT effects may be somewhat weaker for ethnic minorities compared to Whites. We find mixed support for the cultural adaptation of CBTs, but evidence for cultural sensitivity training of CBT clinicians is lacking, given a dearth of relevant trials. Based on the limited evidence thus far, we summarize three broad models for addressing cultural issues when providing CBT to diverse populations.

What Four Decades of Meta-Analysis Have Taught Us About Youth Psychotherapy and the Science of Research Synthesis

Intervention scientists have published more than 600 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of youth psychotherapies. Four decades of meta-analyses have been used to synthesize the RCT findings and identify scientifically and clinically significant patterns. These meta-analyses have limitations, noted herein, but they have advanced our understanding of youth psychotherapy, revealing ( a ) mental health problems for which our interventions are more and less successful (e.g., anxiety and depression, respectively); ( b ) the beneficial effects of single-session interventions, interventions delivered remotely, and interventions tested in low- and middle-income countries; ( c ) the association of societal sexism and racism with reduced treatment benefit in majority-girl and majority-Black groups; and, importantly, ( d ) the finding that average youth treatment benefit has not increased across five decades of research, suggesting that new strategies may be needed. Opportunities for the future include boosting relevance to policy and practice and using meta-analysis to identify mechanisms of change and guide personalizing of treatment.

Evaluation of Pressing Issues in Ecological Momentary Assessment

The use of repeated, momentary, real-world assessment methods known as the Experience Sampling Method and Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) has been broadly embraced over the last few decades. These methods have extended our assessment reach beyond lengthy retrospective self-reports as they can capture everyday experiences in their immediate context, including affect, behavior, symptoms, and cognitions. In this review we evaluate nine conceptual, methodological, and psychometric issues about EMA with the goal of stimulating conversation and guiding future research on these matters: the extent to which participants are actually reporting momentary experiences, respondents’ interpretation of momentary questions, the use of comparison standards in responding, efforts to increase the EMA reporting period beyond the moment to longer periods within a day, training of EMA study participants, concerns about selection bias of respondents, the impact of missing EMA assessments, the reliability of momentary data, and for which purposes EMA might be considered a gold standard for assessment. Resolution of these issues should have far-reaching implications for advancing the field.

Machine Learning and the Digital Measurement of Psychological Health

Since its inception, the discipline of psychology has utilized empirical epistemology and mathematical methodologies to infer psychological functioning from direct observation. As new challenges and technological opportunities emerge, scientists are once again challenged to define measurement paradigms for psychological health and illness that solve novel problems and capitalize on new technological opportunities. In this review, we discuss the theoretical foundations of and scientific advances in remote sensor technology and machine learning models as they are applied to quantify psychological functioning, draw clinical inferences, and chart new directions in treatment.

The Questionable Practice of Partialing to Refine Scores on and Inferences About Measures of Psychological Constructs

Partialing is a statistical approach researchers use with the goal of removing extraneous variance from a variable before examining its association with other variables. Controlling for confounds through analysis of covariance or multiple regression analysis and residualizing variables for use in subsequent analyses are common approaches to partialing in clinical research. Despite its intuitive appeal, partialing is fraught with undesirable consequences when predictors are correlated. After describing effects of partialing on variables, we review analytic approaches commonly used in clinical research to make inferences about the nature and effects of partialed variables. We then use two simulations to show how partialing can distort variables and their relations with other variables. Having concluded that, with rare exception, partialing is ill-advised, we offer recommendations for reducing or eliminating problematic uses of partialing. We conclude that the best alternative to partialing is to define and measure constructs so that it is not needed.

Eating Disorders in Boys and Men

While boys and men have historically been underrepresented in eating disorder research, increasing interest and research during the twenty-first century have contributed important knowledge to the field. In this article, we review the epidemiology of eating disorders and muscle dysmorphia (the pathological pursuit of muscularity) in boys and men; specific groups of men at increased risk for eating disorders; sociocultural, psychological, and biological vulnerability factors; and male-specific assessment measures. We also provide an overview of current research on eating disorder and muscle dysmorphia prevention efforts, treatment outcomes, and mortality risk in samples of boys and men. Priorities for future research are including boys and men in epidemiological studies to track changes in incidence, identifying (neuro)biological factors contributing to risk, eliminating barriers to treatment access and utilization, and refining male-specific prevention and treatment efforts.

Mental Health of Transgender and Gender Diverse Youth

Transgender and gender diverse (TGD) children and adolescents are an increasingly visible yet highly stigmatized group. These youth experience more psychological distress than not only their cisgender, heterosexual peers but also their cisgender, sexual minority peers. In this review, we document these mental health disparities and discuss potential explanations for them using a minority stress framework. We also discuss factors that may increase and decrease TGD youth's vulnerability to psychological distress. Further, we review interventions, including gender-affirming medical care, that may improve mental health in TGD youth. We conclude by discussing limitations of current research and suggestions for the future.

Behavioral Interventions for Children and Adults with Tic Disorder

Over the past decade, behavioral interventions have become increasingly recognized and recommended as effective first-line therapies for treating individuals with tic disorders. In this article, we describe a basic theoretical and conceptual framework through which the reader can understand the application of these interventions for treating tics. The three primary behavioral interventions for tics with the strongest empirical support (habit reversal, Comprehensive Behavioral Intervention for Tics, and exposure and response prevention) are described. Research on the efficacy and effectiveness of these treatments is summarized along with a discussion of the research evaluating the delivery of these treatments in different formats and modalities. The article closes with a review of the possible mechanisms of change underlying behavioral interventions for tics and areas for future research.

The Garrett Lee Smith Memorial Act: A Description and Review of the Suicide Prevention Initiative

The Garrett Lee Smith (GLS) Memorial Act, continuously funded since 2004, has supported comprehensive, community-based youth suicide prevention efforts throughout the United States. Compared to matched communities, communities implementing GLS suicide prevention activities have lower population rates of suicide attempts and lower mortality among young people. Positive outcomes have been more pronounced with continuous years of implementation and in less densely populated communities. Cost analyses indicate that implementation of GLS suicide prevention activities more than pays for itself in reduced health care costs associated with fewer emergency department visits and hospitalizations. Although findings are encouraging, the heterogeneity of community suicide prevention programs and the lack of randomized trials preclude definitive determination of causal effects associated with GLS. The GLS initiative has never been brought fully to scale (e.g., simultaneously impacting all communities in the United States), so beneficial effects on nationwide suicide rates have not been realized.

Racism and Social Determinants of Psychosis

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has identified racism as a serious threat to public health. Structural racism is a fundamental cause of inequity within interconnected institutions and the social environments in which we live and develop. This review illustrates how these ethnoracial inequities impact risk for the extended psychosis phenotype. Black and Latinx populations are more likely than White populations to report psychotic experiences in the United States due to social determining factors such as racial discrimination, food insecurity, and police violence. Unless we dismantle these discriminatory structures, the chronic stress and biological consequences of this race-based stress and trauma will impact the next generation's risk for psychosis directly, and indirectly through Black and Latina pregnant mothers. Multidisciplinary early psychosis interventions show promise in improving prognosis, but coordinated care and other treatments still need to be more accessible and address the racism-specific adversities many Black and Latinx people face in their neighborhoods and social environments.

Developmental Consequences of Intimate Partner Violence on Children

Numerous studies associate childhood exposure to intimate partner violence (IPV) with adverse adjustment in the domains of mental health, social, and academic functioning. This review synthesizes this literature and highlights the critical role of child self-regulation in mediating children's adjustment outcomes. We discuss major methodological problems of the field, including failure to consider the effects of prenatal IPV exposure and the limitations of variable-oriented and cross-sectional approaches. Finally, we present a comprehensive theoretical model of the effects of IPV on children's development. This model includes three mechanistic pathways—one that is unique to IPV (maternal representations) and two that are consistent with the effects of other stressors (maternal mental health and physiological functioning). In our model, the effects of these three pathways on child adjustment outcomes are mediated through parenting and child self-regulation. Future research directions and clinical implications are discussed in the context of the model.

Psychoneuroimmunology: An Introduction to Immune-to-Brain Communication and Its Implications for Clinical Psychology

Research conducted over the past several decades has revolutionized our understanding of the role of the immune system in neural and psychological development and function across the life span. Our goal in this review is to introduce this dynamic area of research to a psychological audience and highlight its relevance for clinical psychology. We begin by introducing the basic physiology of immune-to-brain signaling and the neuroimmune network, focusing on inflammation. Drawing from preclinical and clinical research, we then examine effects of immune activation on key psychological domains, including positive and negative valence systems, social processes, cognition, and arousal (fatigue, sleep), as well as links with psychological disorders (depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, schizophrenia). We also consider psychosocial stress as a critical modulator of neuroimmune activity and focus on early life adversity. Finally, we highlight psychosocial and mind–body interventions that influence the immune system and may promote neuroimmune resilience.

Racial, Ethnic, and Cultural Resilience Factors in African American Youth Mental Health

Racism constitutes a significant risk to the mental health of African American children, adolescents, and emerging adults. This review evaluates recent literature examining ethnic and racial identity, ethnic-racial socialization, religiosity and spirituality, and family and parenting as racial, ethnic, and cultural resilience factors that shape the impact of racism on youth mental health. Representative studies, purported mechanisms, and critiques of prior research are presented for each factor. Recent studies of racism and resilience revisit foundational resilience factors from prior research while reflecting new and important advances (e.g., consideration of gender, cultural context, structural racism), providing important insights for the development of prevention and intervention efforts and policy that can alleviate mental health suffering and promote health and mental health equity for African American youth.

Acculturation and Psychopathology

Acculturation and psychopathology are linked in integrated, interactional, intersectional, and dynamic ways that span different types of intercultural contact, levels of analysis, timescales, and contexts. A developmental psychopathology approach can be useful to explain why, how, and what about psychological acculturation results in later adaptation or maladaptation for acculturating youth and adults. This review applies a conceptual model of acculturation and developmental psychopathology to a widely used framework of acculturation variables producing an Integrated Process Framework of Acculturation Variables (IP-FAV). This new comprehensive framework depicts major predisposing acculturation conditions (why) as well as acculturation orientations and processes (how) that result in adaptation and maladaptation across the life span (what). The IP-FAV is unique in that it integrates both proximal and remote acculturation variables and explicates key acculturation processes to inform research, practice, and policy.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Refugees

The number of refugees and internally displaced people in 2022 is the largest since World War II, and meta-analyses demonstrate that these people experience elevated rates of mental health problems. This review focuses on the role of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in refugee mental health and includes current knowledge of the prevalence of PTSD, risk factors, and apparent differences that exist between PTSD in refugee populations and PTSD in other populations. An emerging literature on understanding mechanisms of PTSD encompasses neural, cognitive, and social processes, which indicate that these factors may not function exactly as they have functioned previously in other PTSD populations. This review recognizes the numerous debates in the literature on PTSD in refugees, including those on such issues as the conceptualization of mental health and the applicability of the PTSD diagnosis across cultures, as well as the challenge of treating PTSD in low- and middle-income countries that lack mental health resources to offer standard PTSD treatments.

Risk and Resilience Among Children with Incarcerated Parents: A Review and Critical Reframing

Parental incarceration is a significant, inequitably distributed form of adversity that affects millions of US children and increases their risk for emotional and behavioral problems. An emerging body of research also indicates, however, that children exhibit resilience in the context of parental incarceration. In this article, we review evidence regarding the adverse implications of parental incarceration for children's adjustment and consider factors that account for these consequences with special attention to naturally occurring processes and interventions that may mitigate risk and contribute to positive youth development. We also offer a critical reframing of resilience research and argue that ( a ) scholars should adopt more contextualized approaches to the study of resilience that are sensitive to intersecting inequalities and ( b ) resilience research and practice should be conceptualized as important complements to, rather than substitutes for, social and institutional change. We conclude by offering social justice–informed recommendations for future research and practice.

Supernatural Attributions: Seeing God, the Devil, Demons, Spirits, Fate, and Karma as Causes of Events

For many people worldwide, supernatural beliefs and attributions—those focused on God, the devil, demons, spirits, an afterlife, karma, or fate—are part of everyday life. Although not widely studied in clinical psychology, these beliefs and attributions are a key part of human diversity. This article provides a broad overview of research on supernatural beliefs and attributions with special attention to their psychological relevance: They can serve as coping resources, sources of distress, psychopathology signals, moral guides, and decision-making tools. Although supernatural attributions sometimes involve dramatic experiences seen to violate natural laws, people more commonly think of supernatural entities working indirectly through natural events. A whole host of factors can lead people to make supernatural attributions, including contextual factors, specific beliefs, psychopathology, cognitive styles and personality, and social and cultural influences. Our aim is to provide clinical psychologists with an entry point into this rich, fascinating, and often overlooked literature.

Volume 19 (2023)

Volume 18 (2022), volume 17 (2021), volume 16 (2020), volume 15 (2019), volume 14 (2018), volume 13 (2017), volume 12 (2016), volume 11 (2015), volume 10 (2014), volume 9 (2013), volume 8 (2012), volume 7 (2011), volume 6 (2010), volume 5 (2009), volume 4 (2008), volume 3 (2007), volume 2 (2006), volume 1 (2005), volume 0 (1932).

Online ordering is currently unavailable due to technical issues. We apologise for any delays responding to customers while we resolve this. For further updates please visit our website: https://www.cambridge.org/news-and-insights/technical-incident Due to planned maintenance there will be periods of time where the website may be unavailable. We apologise for any inconvenience.

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > The Psychologist's Companion

- > Writing a Literature Review

Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I Macro-Challenges in Writing Papers: Planning and Formulating Papers

- 1 Eight Common Misconceptions about Psychology Papers

- 2 How to Generate, Evaluate, and Sell Your Ideas for Research and Papers

- 3 Literature Research

- 4 Writing a Literature Review

- 5 Planning and Writing the Experimental Research Paper

- 6 Ethics in Research and Writing

- Part II Micro-Challenges in Writing Papers: Presenting Your Ideas in Writing

- Part III Writing and Preparing Articles for Journal Submission

- Part IV Presenting Yourself to Others

4 - Writing a Literature Review

from Part I - Macro-Challenges in Writing Papers: Planning and Formulating Papers

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 November 2016

Most undergraduate research papers, and many graduate and professional research papers as well, are based on literature reviews. The aims of a literature review are different from those of an empirical research paper, and hence the skills required differ somewhat as well. The goals of literature reviews are the following (American Psychological Association, 2009):

1. To define and clarify problems

2. To inform the reader about a subject by summarizing and evaluating studies

3. To identify inconsistencies, gaps, contradictions, and relationships in the literature

4. To suggest future steps and approaches to solve the issues identified

There are five kinds of literature reviews that can be distinguished on the basis of the aim of the review. Reviews can strive to (a) generate new knowledge, (b) test theories, (c) integrate theories, (d) develop a new theory, or (e) integrate existing knowledge.

If you plan to submit your literature review to a journal and have to decide where to submit it, you may want to read some literature reviews that have been published in the journals you are considering to find out whether your paper is a good fit to the journal. Generally, the probability of an article being accepted is highest when you develop new knowledge, a new theory, or integrate several theories (instead of just reviewing and summarizing the literature on a particular topic) (Eisenberg, 2000). In general, the best literature reviews do not merely summarize literature; they also create new knowledge by placing the literature into a new framework or at least seeing the literature in a new way.

The literature review can proceed smoothly if you follow a sequence of simple steps:

1. Decide on a topic for a paper.

2. Organize and search the literature.

3. Prepare an outline.

4. Write the paper.

5. Evaluate the paper yourself and seek others’ feedback on it.

DECIDING ON A TOPIC FOR A PAPER

Your first task is to decide on a topic for a paper. This is, in a sense, the most important task because the paper can be no better than the topic. We have found five mistakes that repeatedly turn up in writers’ choices of topics:

1. The topic doesn't interest the writer.

2. The topic is too easy or too safe for the writer.

3. The topic is too difficult for the writer.

4. There is inadequate literature on the topic.

5. The topic is too broad.

Access options

Save book to kindle.

To save this book to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service .

- Writing a Literature Review

- Robert J. Sternberg , Cornell University, New York , Karin Sternberg , Cornell University, New York

- Book: The Psychologist's Companion

- Online publication: 24 November 2016

- Chapter DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316488935.006

Save book to Dropbox

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save book to Google Drive

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 24 February 2022

Systematic literature review of schizophrenia clinical practice guidelines on acute and maintenance management with antipsychotics

- Christoph U. Correll ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7254-5646 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Amber Martin 4 ,

- Charmi Patel 5 ,

- Carmela Benson 5 ,

- Rebecca Goulding 6 ,

- Jennifer Kern-Sliwa 5 ,

- Kruti Joshi 5 ,

- Emma Schiller 4 &

- Edward Kim ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8247-6675 7

Schizophrenia volume 8 , Article number: 5 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

15k Accesses

53 Citations

14 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Schizophrenia

Clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) translate evidence into recommendations to improve patient care and outcomes. To provide an overview of schizophrenia CPGs, we conducted a systematic literature review of English-language CPGs and synthesized current recommendations for the acute and maintenance management with antipsychotics. Searches for schizophrenia CPGs were conducted in MEDLINE/Embase from 1/1/2004–12/19/2019 and in guideline websites until 06/01/2020. Of 19 CPGs, 17 (89.5%) commented on first-episode schizophrenia (FES), with all recommending antipsychotic monotherapy, but without agreement on preferred antipsychotic. Of 18 CPGs commenting on maintenance therapy, 10 (55.6%) made no recommendations on the appropriate maximum duration of maintenance therapy, noting instead individualization of care. Eighteen (94.7%) CPGs commented on long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs), mainly in cases of nonadherence (77.8%), maintenance care (72.2%), or patient preference (66.7%), with 5 (27.8%) CPGs recommending LAIs for FES. For treatment-resistant schizophrenia, 15/15 CPGs recommended clozapine. Only 7/19 (38.8%) CPGs included a treatment algorithm.

Similar content being viewed by others

Adults who microdose psychedelics report health related motivations and lower levels of anxiety and depression compared to non-microdosers

The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence

Psilocybin microdosers demonstrate greater observed improvements in mood and mental health at one month relative to non-microdosing controls

Introduction.

Schizophrenia is an often debilitating, chronic, and relapsing mental disorder with complex symptomology that manifests as a combination of positive, negative, and/or cognitive features 1 , 2 , 3 . Standard management of schizophrenia includes the use of antipsychotic medications to help control acute psychotic episodes 4 and prevent relapses 5 , 6 , whereas maintenance therapy is used in the long term after patients have been stabilized 7 , 8 , 9 . Two main classes of drugs—first- and second-generation antipsychotics (FGA and SGA)—are used to treat schizophrenia 10 . SGAs are favored due to the lower rates of adverse effects, such as extrapyramidal effects, tardive dyskinesia, and relapse 11 . However, pharmacologic treatment for schizophrenia is complicated because nonadherence is prevalent, and is a major risk factor for relapse 9 and poor overall outcomes 12 . The use of long-acting injectable (LAI) versions of antipsychotics aims to limit nonadherence-related relapses and poor outcomes 13 .

Patient treatment pathways and treatment choices are determined based on illness acuity/severity, past treatment response and tolerability, as well as balancing medication efficacy and adverse effect profiles in the context of patient preferences and adherence patterns 14 , 15 . Clinical practice guidelines (CPG) serve to inform clinicians with recommendations that reflect current evidence from meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), individual RCTs and, less so, epidemiologic studies, as well as clinical experience, with the goal of providing a framework and road-map for treatment decisions that will improve quality of care and achieve better patients outcomes. The use of clinical algorithms or other decision trees in CPGs may improve the ease of implementation of the evidence in clinical practice 16 . While CPGs are an important tool for mental health professionals, they have not been updated on a regular basis like they have been in other areas of medicine, such as in oncology. In the absence of current information, other governing bodies, healthcare systems, and hospitals have developed their own CPGs regarding the treatment of schizophrenia, and many of these have been recently updated 17 , 18 , 19 . As such, it is important to assess the latest guidelines to be aware of the changes resulting from consideration of updated evidence that informed the treatment recommendations. Since CPGs are comprehensive and include the diagnosis as well as the pharmacological and non-pharmacological management of individuals with schizophrenia, a detailed comparative review of all aspects of CPGs for schizophrenia would have been too broad a review topic. Further, despite ongoing efforts to broaden the pharmacologic tools for the treatment of schizophrenia 20 , antipsychotics remain the cornerstone of schizophrenia management 8 , 21 . Therefore, a focused review of guideline recommendations for the management of schizophrenia with antipsychotics would serve to provide clinicians with relevant information for treatment decisions.

To provide an updated overview of United States (US) national and English language international guidelines for the management of schizophrenia, we conducted a systematic literature review (SLR) to identify CPGs and synthesize current recommendations for pharmacological management with antipsychotics in the acute and maintenance phases of schizophrenia.

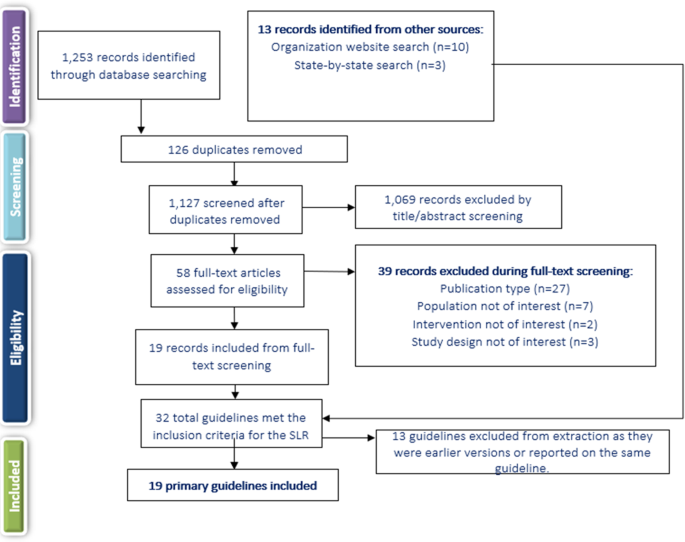

Systematic searches for the SLR yielded 1253 hits from the electronic literature databases. After removal of duplicate references, 1127 individual articles were screened at the title and abstract level. Of these, 58 publications were deemed eligible for screening at the full-text level, from which 19 were ultimately included in the SLR. Website searches of relevant organizations yielded 10 additional records, and an additional three records were identified by the state-by-state searches. Altogether, this process resulted in 32 records identified for inclusion in the SLR. Of the 32 sources, 19 primary CPGs, published/issued between 2004 and 2020, were selected for extraction, as illustrated in the PRISMA diagram (Fig. 1 ). While the most recent APA guideline was identified and available for download in 2020, the reference to cite in the document indicates a publication date of 2021.

SLR systematic literature review.

Of the 19 included CPGs (Table 1 ), three had an international focus (from the following organizations: International College of Neuropsychopharmacology [CINP] 22 , United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees [UNHCR] 23 , and World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry [WFSBP] 24 , 25 , 26 ); seven originated from the US; 17 , 18 , 19 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 three were from the United Kingdom (British Association for Psychopharmacology [BAP] 33 , the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE] 34 , and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network [SIGN] 35 ); and one guideline each was from Singapore 36 , the Polish Psychiatric Association (PPA) 37 , 38 , the Canadian Psychiatric Association (CPA) 14 , the Royal Australia/New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) 39 , the Association Française de Psychiatrie Biologique et de Neuropsychopharmacologie (AFPBN) from France 40 , and Italy 41 . Fourteen CPGs (74%) recommended treatment with specific antipsychotics and 18 (95%) included recommendations for the use of LAIs, while just seven included a treatment algorithm Table 2 ). The AGREE II assessment resulted in the highest score across the CPGs domains for NICE 34 followed by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) guidelines 17 . The CPA 14 , BAP 33 , and SIGN 35 CPGs also scored well across domains.

Acute therapy

Seventeen CPGs (89.5%) provided treatment recommendations for patients experiencing a first schizophrenia episode 14 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 28 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 39 , 40 , 41 , but the depth and focus of the information varied greatly (Supplementary Table 1 ). In some CPGs, information on treatment of a first schizophrenia episode was limited or grouped with information on treating any acute episode, such as in the CPGs from CINP 22 , AFPBN 40 , New Jersey Division of Mental Health Services (NJDMHS) 32 , the APA 17 , and the PPA 37 , 38 , while the others provided more detailed information specific to patients experiencing a first schizophrenia episode 14 , 18 , 19 , 23 , 24 , 28 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 39 , 41 . The American Association of Community Psychiatrists (AACP) Clinical Tips did not provide any information on the treatment of schizophrenia patients with a first episode 29 .

There was little agreement among CPGs regarding the preferred antipsychotic for a first schizophrenia episode. However, there was strong consensus on antipsychotic monotherapy and that lower doses are generally recommended due to better treatment response and greater adverse effect sensitivity. Some guidelines recommended SGAs over FGAs when treating a first-episode schizophrenia patient (RANZCP 39 , Texas Medication Algorithm Project [TMAP] 28 , Oregon Health Authority 19 ), one recommended starting patients on an FGA (UNHCR 23 ), and others stated specifically that there was no evidence of any difference in efficacy between FGAs and SGAs (WFSBP 24 , CPA 14 , SIGN 35 , APA 17 , Singapore guidelines 36 ), or did not make any recommendation (CINP 22 , Italian guidelines 41 , NICE 34 , NJDMHS 32 , Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team [PORT] 30 , 31 ). The BAP 33 and WFBSP 24 noted that while there was probably no difference between FGAs and SGAs in efficacy, some SGAs (olanzapine, amisulpride, and risperidone) may perform better than some FGAs. The Schizophrenia PORT recommendations noted that while there seemed to be no differences between SGAs and FGAs in short-term studies (≤12 weeks), longer studies (one to two years) suggested that SGAs may provide benefits in terms of longer times to relapse and discontinuation rates 30 , 31 . The AFPBN guidelines 40 and Florida Medicaid Program guidelines 18 , which both focus on use of LAI antipsychotics, both recommended an SGA-LAI for patients experiencing a first schizophrenia episode. A caveat in most CPGs was that physicians and their patients should discuss decisions about the choice of antipsychotic and that the choice should consider individual patient factors/preferences, risk of adverse and metabolic effects, and symptom patterns 17 , 18 , 19 , 22 , 24 , 28 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 39 , 41 .

Most CPGs recommended switching to a different monotherapy if the initial antipsychotic was not effective or not well tolerated after an adequate antipsychotic trial at an appropriate dose 14 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 28 , 32 , 33 , 35 , 36 , 39 . For patients initially treated with an FGA, the UNHCR recommended switching to an SGA (olanzapine or risperidone) 23 . Guidance on response to treatment varied in the measures used but typically required at least a 20% improvement in symptoms (i.e. reduction in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale or Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale scores) from pre-treatment levels.

Several CPGs contained recommendations on the duration of antipsychotic therapy after a first schizophrenia episode. The NJDMHS guidelines 32 recommended nine to 12 months; CINP 22 recommended at least one year; CPA 14 recommended at least 18 months; WFSBP 25 , the Italian guidelines 41 , and NICE 34 recommended 1 to 2 years; and the RANZCP 39 , BAP 33 , and SIGN 35 recommended at least 2 years. The APA 17 and TMAP 28 recommended continuing antipsychotic treatment after resolution of first-episode symptoms but did not recommend a specific length of therapy.

Twelve guidelines 14 , 18 , 22 , 24 , 28 , 30 , 31 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 39 , 40 (63.2%) discussed the treatment of subsequent/multiple episodes of schizophrenia (i.e., following relapse). These CPGs noted that the considerations guiding the choice of antipsychotic for subsequent/multiple episodes were similar to those for a first episode, factoring in prior patient treatment response, adverse effect patterns and adherence. The CPGs also noted that response to treatment may be lower and require higher doses to achieve a response than for first-episode schizophrenia, that a different antipsychotic than used to treat the first episode may be needed, and that a switch to an LAI is an option.

Several CPGs provided recommendations for patients with specific clinical features (Supplementary Table 1 ). The most frequently discussed group of clinical features was negative symptoms, with recommendations provided in the CINP 22 , UNHCR 23 , WFSBP 24 , AFPBN 40 , SIGN 35 , BAP 33 , APA 17 , and NJDMHS guidelines; 32 negative symptoms were the sole focus of the guidelines from the PPA 37 , 38 . The guidelines noted that due to limited evidence in patients with predominantly negative symptoms, there was no clear benefit for any strategy, but that options included SGAs (especially amisulpride) rather than FGAs (WFSBP 24 , CINP 22 , AFPBN 40 , SIGN 35 , NJDMHS 32 , PPA 37 , 38 ), and addition of an antidepressant (WFSBP 24 , UNHCR 23 , SIGN 35 , NJDMHS 32 ) or lamotrigine (SIGN 35 ), or switching to another SGA (NJDMHS 32 ) or clozapine (NJDMHS 32 ). The PPA guidelines 37 , 38 stated that the use of clozapine or adding an antidepressant or other medication class was not supported by evidence, but recommended the SGA cariprazine for patients with predominant and persistent negative symptoms, and other SGAs for those with full-spectrum negative symptoms. However, the BAP 33 stated that no recommendations can be made for any of these strategies because of the quality and paucity of the available evidence.

Some of the CPGs also discussed treatment of other clinical features to a limited degree, including depressive symptoms (CINP 22 , UNHCR 23 , CPA 14 , APA 17 , and NJDMHS 32 ), cognitive dysfunction (CINP 22 , UNHCR 23 , WFSBP 24 , AFPBN 40 , SIGN 35 , BAP 33 , and NJDMHS 32 ), persistent aggression (CINP 22 , WFSBP 24 , CPA 14 , AFPBN 40 , NICE 34 , SIGN 35 , BAP 33 , and NJDMHS 32 ), and comorbid psychiatric diagnoses (CINP 22 , RANZCP 39 , BAP 33 , APA 17 , and NJDMHS 32 ).

Fifteen CPGs (78.9%) discussed treatment-resistant schizophrenia (TRS); all defined it as persistent, predominantly positive symptoms after two adequate antipsychotic trials; clozapine was the unanimous first choice 14 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 28 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 39 . However, the UNHCR guidelines 23 , which included recommendations for treatment of refugees, noted that clozapine is only a reasonable choice in regions where white blood cell monitoring and specialist supervision are available, otherwise, risperidone or olanzapine are alternatives if they had not been used in the previous treatment regimen.

There were few options for patients who are resistant to clozapine therapy, and evidence supporting these options was limited. The CPA guidelines 14 therefore stated that no recommendation can be given due to inadequate evidence. Other CPGs discussed options (but noted there was limited supporting evidence), such as switching to olanzapine or risperidone (WFSBP 24 , TMAP 28 ), adding a second antipsychotic to clozapine (CINP 22 , NICE 34 , TMAP 28 , BAP 33 , Florida Medicaid Program 18 , Oregon Health Authority 19 , RANZCP 39 ), adding lamotrigine or topiramate to clozapine (CINP 22 , Florida Medicaid Program 18 ), combination therapy with two non-clozapine antipsychotics (Florida Medicaid Program 18 , NJDMHS 32 ), and high-dose non-clozapine antipsychotic therapy (BAP 33 , SIGN 35 ). Electroconvulsive therapy was noted as a last resort for patients who did not respond to any pharmacologic therapy, including clozapine, by 10 CPGs 17 , 18 , 19 , 22 , 24 , 28 , 32 , 35 , 36 , 39 .

Maintenance therapy

Fifteen CPGs (78.9%) discussed maintenance therapy to various degrees via dedicated sections or statements, while three others referred only to maintenance doses by antipsychotic agent 18 , 23 , 29 without accompanying recommendations (Supplementary Table 2 ). Only the Italian guideline provided no reference or comments on maintenance treatment. The CINP 22 , WFSBP 25 , RANZCP 39 , and Schizophrenia PORT 30 , 31 recommended keeping patients on the same antipsychotic and at the same dose on which they had achieved remission. Several CPGs recommended maintenance therapy at the lowest effective dose (NJDMHS 32 , APA 17 , Singapore guidelines 36 , and TMAP 28 ). The CPA 14 and SIGN 35 defined the lower dose as 300–400 mg chlorpromazine equivalents or 4–6 mg risperidone equivalents, and the Singapore guidelines 36 stated that the lower dose should not be less than half the original dose. TMAP 28 stated that given the relapsing nature of schizophrenia, the maintenance dose should often be close to the original dose. While SIGN 35 recommended that patients remain on the same antipsychotic that provided remission, these guidelines also stated that maintenance with amisulpride, olanzapine, or risperidone was preferred, and that chlorpromazine and other low-potency FGAs were also suitable. The BAP 33 recommended that the current regimen be optimized before any dose reduction or switch to another antipsychotic occurs. Several CPGs recommended LAIs as an option for maintenance therapy (see next section).

Altogether, 10/18 (55.5%) CPGs made no recommendations on the appropriate duration of maintenance therapy, noting instead that each patient should be considered individually. Other CPGs made specific recommendations: Both the Both BAP 33 and SIGN 35 guidelines suggested a minimum of 2 years, the NJDMHS guidelines 32 recommended 2–3 years; the WFSBP 25 recommended 2–5 years for patients who have had one relapse and more than 5 years for those who have had multiple relapses; the RANZCP 39 and the CPA 14 recommended 2–5 years; and the CINP 22 recommended that maintenance therapy last at least 6 years for patients who have had multiple episodes. The TMAP was the only CPG to recommend that maintenance therapy be continued indefinitely 28 .

Recommendations on the use of LAIs

All CPGs except the one from Italy (94.7%) discussed the use of LAIs for patients with schizophrenia to some extent. As shown in Table 3 , among the 18 CPGs, LAIs were primarily recommended in 14 CPGs (77.8%) for patients who are non-adherent to other antipsychotic administration routes (CINP 22 , UNHCR 23 , RANZCP 39 , PPA 37 , 38 , Singapore guidelines 36 , NICE 34 , SIGN 35 , BAP 33 , APA 17 , TMAP 28 , NJDMHS 32 , AACP 29 , Oregon Health Authority 19 , Florida Medicaid Program 18 ). Twelve CPGs (66.7%) also noted that LAIs should be prescribed based on patient preference (RANZCP 39 , CPA 14 , AFPBN 40 , Singapore guidelines 36 , NICE 34 , SIGN 35 , BAP 33 , APA 17 , Schizophrenia PORT 30 , 31 , AACP 29 , Oregon Health Authority 19 , Florida Medicaid Program 18 ).

Thirteen CPGs (72.2%) recommended LAIs as maintenance therapy 18 , 19 , 24 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 39 , 40 . While five CPGs (27.8%), i.e., AFPBN 40 , RANZCP 39 , TMAP 28 , NJDMHS 32 , and the Florida Medicaid Program 18 recommended LAIs specifically for patients experiencing a first episode. While the CPA 14 did not make any recommendations regarding when LAIs should be used, they discussed recent evidence supporting their use earlier in treatment. Five guidelines (27.8%, i.e., Singapore 36 , NICE 34 , SIGN 35 , BAP 33 , and Schizophrenia PORT 30 , 31 ) noted that evidence around LAIs was not sufficient to support recommending their use for first-episode patients. The AFPBN guidelines 40 also stated that LAIs (SGAs as first-line and FGAs as second-line treatment) should be more frequently considered for maintenance treatment of schizophrenia. Four CPGs (22.2%, i.e., CINP 22 , UNHCR 23 , Italian guidelines 41 , PPA guidelines 37 , 38 ) did not specify when LAIs should be used. The AACP guidelines 29 , which evaluated only LAIs, recommended expanding their use beyond treatment for nonadherence, suggesting that LAIs may offer a more convenient mode of administration or potentially address other clinical and social challenges, as well as provide more consistent plasma levels.

Treatment algorithms

Only Seven CPGs (36.8%) included an algorithm as part of the treatment recommendations. These included decision trees or flow diagrams that map out initial therapy, durations for assessing response, and treatment options in cases of non-response. However, none of these guidelines defined how to measure response, a theme that also extended to guidelines that did not include treatment algorithms. Four of the seven guidelines with algorithms recommended specific antipsychotic agents, while the remaining three referred only to the antipsychotic class.

LAIs were not consistently incorporated in treatment algorithms and in six CPGs were treated as a separate category of medicine reserved for patients with adherence issues or a preference for the route of administration. The only exception was the Florida Medicaid Program 18 , which recommended offering LAIs after oral antipsychotic stabilization even to patients who are at that point adherent to oral antipsychotics.

Benefits and harms

The need to balance the efficacy and safety of antipsychotics was mentioned by all CPGs as a basic treatment paradigm.

Ten CPGs provided conclusions on benefits of antipsychotic therapy. The APA 17 and the BAP 33 guidelines stated that antipsychotic treatment can improve the positive and negative symptoms of psychosis and leads to remission of symptoms. These CPGs 17 , 33 as well as those from NICE 34 and CPA 14 stated that these treatment effects can also lead to improvements in quality of life (including quality-adjusted life years), improved functioning, and reduction in disability. The CPA 14 and APA 17 guidelines noted decreases in hospitalizations with antipsychotic therapy, and the APA guidelines 17 stated that long-term antipsychotic treatment can also reduce mortality. The UNHCR 23 and the Italian 41 guidelines noted that early intervention increased positive outcomes. The WFSBP 24 , AFPBN 40 , CPA 14 , BAP 33 , APA 17 , and NJDMHS 32 affirmed that relapse prevention is a benefit of continued/maintenance treatment.

Some CPGs (WFSBP 24 , Italian 41 , CPA 14 , and SIGN 35 ) noted that reduced risk for extrapyramidal adverse effects and treatment discontinuation were potential benefits of SGAs vs. FGAs.

The risk of adverse effects (e.g., extrapyramidal, metabolic, cardiovascular, and hormonal adverse effects, sedation, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome) was noted by all CPGs as the major potential harm of antipsychotic therapy 14 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 . These adverse effects are known to limit long-term treatment and adherence 24 .

This SLR of CPGs for the treatment of schizophrenia yielded 19 most updated versions of individual CPGs, published/issued between 2004 and 2020. Structuring our comparative review according to illness phase, antipsychotic type and formulation, response to antipsychotic treatment as well as benefits and harms, several areas of consistent recommendations emerged from this review (e.g., balancing risk and benefits of antipsychotics, preferring antipsychotic monotherapy; using clozapine for treatment-resistant schizophrenia). On the other hand, other recommendations regarding other areas of antipsychotic treatment were mostly consistent (e.g., maintenance antipsychotic treatment for some time), somewhat inconsistent (e.g., differences in the management of first- vs multi-episode patients, type of antipsychotic, dose of antipsychotic maintenance treatment), or even contradictory (e.g., role of LAIs in first-episode schizophrenia patients).

Consistent with RCT evidence 43 , 44 , antipsychotic monotherapy was the treatment of choice for patients with first-episode schizophrenia in all CPGs, and all guidelines stated that a different single antipsychotic should be tried if the first is ineffective or intolerable. Recommendations were similar for multi-episode patients, but factored in prior patient treatment response, adverse effect patterns, and adherence. There was also broad consensus that the side-effect profile of antipsychotics is the most important consideration when making a decision on pharmacologic treatment, also reflecting meta-analytic evidence 4 , 5 , 10 . The risk of extrapyramidal symptoms (especially with FGAs) and metabolic effects (especially with SGAs) were noted as key considerations, which are also reflected in the literature as relevant concerns 4 , 45 , 46 , including for quality of life and treatment nonadherence 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 .

Largely consistent with the comparative meta-analytic evidence regarding the acute 4 , 51 , 52 and maintenance antipsychotic treatment 5 effects of schizophrenia, the majority of CPGs stated there was no difference in efficacy between SGAs and FGAs (WFSBP 24 , CPA 14 , SIGN 35 , APA 17 , and Singapore guidelines 36 ), or did not make any recommendations (CINP 22 , Italian guidelines 41 , NICE 34 , NJDMHS 32 , and Schizophrenia PORT 30 , 31 ); three CPGs (BAP 33 , WFBSP 24 , and Schizophrenia PORT 30 , 31 ) noted that SGAs may perform better than FGAs over the long term, consistent with a meta-analysis on this topic 53 .

The 12 CPGs that discussed treatment of subsequent/multiple episodes generally agreed on the factors guiding the choices of an antipsychotic, including that the decision may be more complicated and response may be lower than with a first episode, as described before 7 , 54 , 55 , 56 .

There was little consensus regarding maintenance therapy. Some CPGs recommended the same antipsychotic and dose that achieved remission (CINP 22 , WFSBP 25 , RANZCP 39 , and Schizophrenia PORT 30 , 31 ) and others recommended the lowest effective dose (NJDMHS 32 , APA 17 , Singapore guidelines 36 , TMAP 28 , CPA 14 , and SIGN 35 ). This inconsistency is likely based on insufficient data as well as conflicting results in existing meta-analyses on this topic 57 , 58 , 59 .

The 15 CPGs that discussed TRS all used the same definition for this condition, consistent with recent commendations 60 , and agreed that clozapine is the primary evidence-based treatment choice 14 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 28 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 39 , reflecting the evidence base 61 , 62 , 63 . These CPGs also agreed that there are few options well supported by evidence for patients who do not respond to clozapine, with a recent meta-analysis of RCTs showing that electroconvulsive therapy augmentation may be the most evidence-based treatment option 64 .

One key gap in the treatment recommendations was how long patients should remain on antipsychotic therapy after a first episode or during maintenance therapy. While nine of the 17 CPGs discussing treatment of a first episode provided a recommended timeframe (varying from 1 to 2 years) 14 , 22 , 24 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 39 , 41 , the APA 17 and TMAP 28 recommended continuing antipsychotic treatment after resolution of first-episode symptoms but did not recommend a specific length of therapy. Similarly, six of the 18 CPGs discussing maintenance treatment recommended a specific duration of therapy (ranging from two to six years) 14 , 22 , 25 , 32 , 39 , while as many as 10 CPGs did not point to a firm end of the maintenance treatment, instead recommending individualized decisions. The CPGs not stating a definite endpoint or period of maintenance treatment after repeated schizophrenia episodes or even after a first episode of schizophrenia, reflects the different evidence types on which the recommendation is based. The RCT evidence ends after several years of maintenance treatment vs. discontinuation supporting ongoing antipsychotic treatment; however, naturalistic database studies do not indicate any time period after which one can safely discontinue maintenance antipsychotic care, even after a first schizophrenia episode 8 , 65 . In fact, stopping antipsychotics is associated not only with a substantially increased risk of hospitalization but also mortality 65 , 66 , 67 . In this sense, not stating an endpoint for antipsychotic maintenance therapy should not be taken as an implicit statement that antipsychotics should be discontinued at any time; data suggest the contrary.

A further gap exists regarding the most appropriate treatment of negative symptoms, such as anhedonia, amotivation, asociality, affective flattening, and alogia 1 , a long-standing challenge in the management of patients with schizophrenia. Negative symptoms often persist in patients after positive symptoms have resolved, or are the presenting feature in a substantial minority of patients 22 , 35 . Negative symptoms can also be secondary to pharmacotherapy 22 , 68 . Antipsychotics have been most successful in treating positive symptoms, and while eight of the CPGs provided some information on treatment of negative symptoms, the recommendations were generally limited 17 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 32 , 33 , 35 , 40 . Negative symptom management was a focus of the PPA guidelines, but the guidelines acknowledged that supporting evidence was limited, often due to the low number of patients with predominantly negative symptoms in clinical trials 37 , 38 . The Polish guidelines are also one of the more recently developed and included the newer antipsychotic cariprazine as a first-line option, which although being a point of differentiation from the other guidelines, this recommendation was based on RCT data 69 .

Another area in which more direction is needed is on the use of LAIs. While all but one of the 19 CPGs discussed this topic, the extent of information and recommendations for LAI use varied considerably. All CPGs categorized LAIs as an option to improve adherence to therapy or based on patient preference. However, 5/18 CPGs (27.8%) recommended the use of LAI early in treatment (at first episode: AFPBN 40 , RANZCP 39 , TMAP 28 , NJDMHS 32 , and Florida Medicaid Program 18 ) or across the entire illness course, while five others stated there was not sufficient evidence to recommend LAIs for these patients (Singapore 36 , NICE 34 , SIGN 35 , BAP 33 , and Schizophrenia PORT 30 , 31 ). The role of LAIs in first-episode schizophrenia was the only point where opposing recommendations were found across CPGs. This contradictory stance was not due to the incorporation of newer data suggesting benefits of LAIs in first episode and early-phase patients with schizophrenia 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 in the CPGs recommending LAI use in first-episode patients, as CPGs recommending LAI use were published between 2005 and 2020, while those opposing LAI use were published between 2011 and 2020. Only the Florida Medicaid CPG recommended LAIs as a first step equivalent to oral antipsychotics (OAP) after initial OAP response and tolerability, independent of nonadherence or other clinical variables. This guideline was also the only CPG to fully integrate LAI use in their clinical algorithm. The remaining six CPGs that included decision tress or treatment algorithms regarded LAIs as a separate paradigm of treatment reserved for nonadherence or patients preference rather than a routine treatment option to consider. While some CPGs provided fairly detailed information on the use of LAIs (AFPBN 40 , AACP 29 , Oregon Health Authority 19 , and Florida Medicaid Program 18 ), others mentioned them only in the context of adherence issues or patient preference. Notably, definitions of and means to determine nonadherence were not reported. One reason for this wide range of recommendations regarding the placement of LAIs in the treatment algorithm and clinical situations that prompt LAI use might be due to the fact that CPGs generally favor RCT evidence over evidence from other study designs. In the case of LAIs, there was a notable dissociation between consistent meta-analytic evidence of statistically significant superiority of LAIs vs OAPs in mirror-image 75 and cohort study designs 76 and non-significant advantages in RCTs 77 . Although patients in RCTs comparing LAIs vs OAPs were less severely ill and more adherent to OAPs 77 than in clinical care and although mirror-image and cohort studies arguably have greater external validity than RCTs 78 , CPGs generally disregard evidence from other study designs when RCT evidence exits. This narrow focus can lead to disregarding important additional data. Nevertheless, a most updated meta-analysis of all 3 study designs comparing LAIs with OAPs demonstrated consistent superiority of LAIs vs OAPs for hospitalization or relapse across all 3 designs 79 , which should lead to more uniform recommendations across CPGs in the future.

Only seven CPGs included treatment algorithms or flow charts to guide LAI treatment selection for patients with schizophrenia 17 , 18 , 19 , 24 , 29 , 35 , 40 . However, there was little commonality across algorithms beyond the guidance on LAIs mentioned above, as some listed specific treatments and conditions for antipsychotic switches, while others indicated that medication choice should be based on a patient’s preferences and responses, side effects, and in some cases, cost effectiveness. Since algorithms and flow charts facilitate the reception, adoption and implementation of guidelines, future CPGs should include them as dissemination tools, but they need to reflect the data and detailed text and be sufficiently specific to be actionable.

The systematic nature in the identification, summarization, and assessment of the CPGs is a strength of this review. This process removed any potential bias associated with subjective selection of evidence, which is not reproducible. However, only CPGs published in English were included and regardless of their quality and differing timeframes of development and publication, complicating a direct comparison of consensus and disagreement. Finally, based on the focus of this SLR, we only reviewed pharmacologic management with antipsychotics. Clearly, the assessment, other pharmacologic and, especially, psychosocial interventions are important in the management of individuals with schizophrenia, but these topics that were covered to varying degrees by the evaluated CPGs were outside of the scope of this review.

Numerous guidelines have recently updated their recommendations on the pharmacological treatment of patients with schizophrenia, which we have summarized in this review. Consistent recommendations were observed across CPGs in the areas of balancing risk and benefits of antipsychotics when selecting treatment, a preference for antipsychotic monotherapy, especially for patients with a first episode of schizophrenia, and the use of clozapine for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. By contrast, there were inconsistencies with regards to recommendations on maintenance antipsychotic treatment, with differences existing on type and dose of antipsychotic, as well as the duration of therapy. However, LAIs were consistently recommended, but mainly suggested in cases of nonadherence or patient preference, despite their established efficacy in broader patient populations and clinical scenarios in clinical trials. Guidelines were sometimes contradictory, with some recommending LAI use earlier in the disease course (e.g., first episode) and others suggesting they only be reserved for later in the disease. This inconsistency was not due to lack of evidence on the efficacy of LAIs in first-episode schizophrenia or the timing of the CPG, so that other reasons might be responsible, including possibly bias and stigma associated with this route of treatment administration. Lastly, gaps existed in the guidelines for recommendations on the duration of maintenance treatment, treatment of negative symptoms, and the development/use of treatment algorithms whenever evidence is sufficient to provide a simplified summary of the data and indicate their relevance for clinical decision making, all of which should be considered in future guideline development/revisions.

The SLR followed established best methods used in systematic review research to identify and assess the available CPGs for pharmacologic treatment of schizophrenia with antipsychotics in the acute and maintenance phases 80 , 81 . The SLR was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, including use of a prespecified protocol to outline methods for conducting the review. The protocol for this review was approved by all authors prior to implementation but was not submitted to an external registry.

Data sources and search algorithms

Searches were conducted by two independent investigators in the MEDLINE and Embase databases via OvidSP to identify CPGs published in English. Articles were identified using search algorithms that paired terms for schizophrenia with keywords for CPGs. Articles indexed as case reports, reviews, letters, or news were excluded from the searches. The database search was limited to CPGs published from January 1, 2004, through December 19, 2019, without limit to geographic location. In addition to the database sources, guideline body websites and state-level health departments from the US were also searched for relevant CPGs published through June 2020. A manual check of the references of recent (i.e., published in the past three years), relevant SLRs and relevant practice CPGs was conducted to supplement the above searches and ensure and the most complete CPG retrieval.

This study did not involve human subjects as only published evidence was included in the review; ethical approval from an institution was therefore not required.

Selection of CPGs for inclusion

Each title and abstract identified from the database searches was screened and selected for inclusion or exclusion in the SLR by two independent investigators based on the populations, interventions/comparators, outcomes, study design, time period, language, and geographic criteria shown in Table 4 . During both rounds of the screening process, discrepancies between the two independent reviewers were resolved through discussion, and a third investigator resolved any disagreement. Articles/documents identified by the manual search of organizational websites were screened using the same criteria. All accepted studies were required to meet all inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria. Only the most recent version of organizational CPGs was included for data extraction.

Data extraction and synthesis

Information on the recommendations regarding the antipsychotic management in the acute and maintenance phases of schizophrenia and related benefits and harms was captured from the included CPGs. Each guideline was reviewed and extracted by a single researcher and the data were validated by a senior team member to ensure accuracy and completeness. Additionally, each included CPG was assessed using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II) tool. Following extraction and validation, results were qualitatively summarized across CPGs.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of the SLR are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Correll, C. U. & Schooler, N. R. Negative symptoms in schizophrenia: a review and clinical guide for recognition, assessment, and treatment. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 16 , 519–534 (2020).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kahn, R. S. et al. Schizophrenia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 1 , 15067 (2015).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Millan, M. J. et al. Altering the course of schizophrenia: progress and perspectives. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 15 , 485–515 (2016).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Huhn, M. et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 32 oral antipsychotics for the acute treatment of adults with multi-episode schizophrenia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet 394 , 939–951 (2019).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kishimoto, T., Hagi, K., Nitta, M., Kane, J. M. & Correll, C. U. Long-term effectiveness of oral second-generation antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia and related disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of direct head-to-head comparisons. World Psychiatry 18 , 208–224 (2019).

Leucht, S. et al. Antipsychotic drugs versus placebo for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 379 , 2063–2071 (2012).

Carbon, M. & Correll, C. U. Clinical predictors of therapeutic response to antipsychotics in schizophrenia. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 16 , 505–524 (2014).

Correll, C. U., Rubio, J. M. & Kane, J. M. What is the risk-benefit ratio of long-term antipsychotic treatment in people with schizophrenia? World Psychiatry 17 , 149–160 (2018).

Emsley, R., Chiliza, B., Asmal, L. & Harvey, B. H. The nature of relapse in schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 13 , 50 (2013).

Correll, C. U. & Kane, J. M. Ranking antipsychotics for efficacy and safety in schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry 77 , 225–226 (2020).

Kane, J. M. & Correll, C. U. Pharmacologic treatment of schizophrenia. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 12 , 345–357 (2010).

Kane, J. M., Kishimoto, T. & Correll, C. U. Non-adherence to medication in patients with psychotic disorders: epidemiology, contributing factors and management strategies. World Psychiatry 12 , 216–226 (2013).

Correll, C. U. et al. The use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in schizophrenia: evaluating the evidence. J. Clin. Psychiatry 77 , 1–24 (2016).

Remington, G. et al. Guidelines for the pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia in adults. Can. J. Psychiatry 62 , 604–616 (2017).

American Psychiatric Association. Treatment recommendations for patients with schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 161 , 1–56 (2004).

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Advise the Public Health Service on Clinical Practice Guidelines, Field, M. J., & Lohr, K. N. (Eds.). Clinical Practice Guidelines: Directions for a New Program. (National Academies Press (US), 1990).

American Psychiatric Association. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia , 3rd edn. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890424841 .

Florida Medicaid Drug Therapy Management Program. 2019–2020 Florida Best Practice Psychotherapeutic Medication Guidelines for Adults . (2020). Available at: https://floridabhcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/2019-Psychotherapeutic-Medication-Guidelines-for-Adults-with-References_06-04-20.pdf .

Mental Health Clinical Advisory Group, Oregon Health Authority. Mental Health Care Guide for Licensed Practitioners and Mental Health Professionals. (2019). Available at: https://sharedsystems.dhsoha.state.or.us/DHSForms/Served/le7548.pdf .

Krogmann, A. et al. Keeping up with the therapeutic advances in schizophrenia: a review of novel and emerging pharmacological entities. CNS Spectr. 24 , 38–69 (2019).

Fountoulakis, K. N. et al. The report of the joint WPA/CINP workgroup on the use and usefulness of antipsychotic medication in the treatment of schizophrenia. CNS Spectr . https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852920001546 (2020).

Leucht, S. et al. CINP Schizophrenia Guidelines . (CINP, 2013). Available at: https://www.cinp.org/resources/Documents/CINP-schizophrenia-guideline-24.5.2013-A-C-method.pdf .

Ostuzzi, G. et al. Mapping the evidence on pharmacological interventions for non-affective psychosis in humanitarian non-specialised settings: A UNHCR clinical guidance. BMC Med. 15 , 197 (2017).

Hasan, A. et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for Biological Treatment of Schizophrenia, Part 1: Update 2012 on the acute treatment of schizophrenia and the management of treatment resistance. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 13 , 318–378 (2012).

Hasan, A. et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for Biological Treatment of Schizophrenia, Part 2: Update 2012 on the long-term treatment of schizophrenia and management of antipsychotic-induced side effects. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 14 , 2–44 (2013).

Hasan, A. et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia - a short version for primary care. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 21 , 82–90 (2017).

Moore, T. A. et al. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project antipsychotic algorithm for schizophrenia: 2006 update. J. Clin. Psychiatry 68 , 1751–1762 (2007).

Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP). Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP) Procedural Manual . (2008). Available at: https://jpshealthnet.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/tmapalgorithmforschizophrenia.pdf .

American Association of Community Psychiatrists (AACP). Clinical Tips Series, Long Acting Antipsychotic Medications. (2017). Accessed at: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1unigjmjFJkqZMbaZ_ftdj8oqog49awZs/view .

Buchanan, R. W. et al. The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychopharmacological treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr. Bull. 36 , 71–93 (2010).

Kreyenbuhl, J. et al. The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): updated treatment recommendations 2009. Schizophr. Bull. 36 , 94–103 (2010).

New Jersey Division of Mental Health Services. Pharmacological Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Schizophrenia . (2005). Available at: https://www.state.nj.us/humanservices/dmhs_delete/consumer/NJDMHS_Pharmacological_Practice_Guidelines762005.pdf .

Barnes, T. R. et al. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: updated recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J. Psychopharmacol. 34 , 3–78 (2020).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management. (2014). Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178 .

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). Management of Schizophrenia: A National Clinical Guideline . (2013). Available at: https://www.sign.ac.uk/assets/sign131.pdf .

Verma, S. et al. Ministry of Health Clinical Practice Guidelines: Schizophrenia. Singap. Med. J. 52 , 521–526 (2011).

CAS Google Scholar

Szulc, A. et al. Recommendations for the treatment of schizophrenia with negative symptoms. Standards of pharmacotherapy by the Polish Psychiatric Association (Polskie Towarzystwo Psychiatryczne), part 1. Rekomendacje dotyczace leczenia schizofrenii z. objawami negatywnymi. Stand. farmakoterapii Polskiego Tow. Psychiatrycznego, czesc 1. 53 , 497–524 (2019).

Google Scholar

Szulc, A. et al. Recommendations for the treatment of schizophrenia with negative symptoms. Standards of pharmacotherapy by the Polish Psychiatric Association (Polskie Towarzystwo Psychiatryczne), part 2. Rekomendacje dotyczace leczenia schizofrenii z. objawami negatywnymi. Stand. farmakoterapii Polskiego Tow. Psychiatrycznego, czesc 2. 53 , 525–540 (2019).

Galletly, C. et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the management of schizophrenia and related disorders. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 50 , 410–472 (2016).

Llorca, P. M. et al. Guidelines for the use and management of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in serious mental illness. BMC Psychiatry 13 , 340 (2013).

De Masi, S. et al. The Italian guidelines for early intervention in schizophrenia: development and conclusions. Early Intervention Psychiatry 2 , 291–302 (2008).

Article Google Scholar

Barnes, T. R. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J. Psychopharmacol. 25 , 567–620 (2011).

Correll, C. U. et al. Efficacy of 42 pharmacologic cotreatment strategies added to antipsychotic monotherapy in schizophrenia: systematic overview and quality appraisal of the meta-analytic evidence. JAMA Psychiatry 74 , 675–684 (2017).

Galling, B. et al. Antipsychotic augmentation vs. monotherapy in schizophrenia: systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis. World Psychiatry 16 , 77–89 (2017).

Pillinger, T. et al. Comparative effects of 18 antipsychotics on metabolic function in patients with schizophrenia, predictors of metabolic dysregulation, and association with psychopathology: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 7 , 64–77 (2020).

Rummel-Kluge, C. et al. Second-generation antipsychotic drugs and extrapyramidal side effects: a systematic review and meta-analysis of head-to-head comparisons. Schizophr. Bull. 38 , 167–177 (2012).

Angermeyer, M. C. & Matschinger, H. Attitude of family to neuroleptics. Psychiatr. Prax. 26 , 171–174 (1999).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Dibonaventura, M., Gabriel, S., Dupclay, L., Gupta, S. & Kim, E. A patient perspective of the impact of medication side effects on adherence: results of a cross-sectional nationwide survey of patients with schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 12 , 20 (2012).

McIntyre, R. S. Understanding needs, interactions, treatment, and expectations among individuals affected by bipolar disorder or schizophrenia: the UNITE global survey. J. Clin. Psychiatry 70 (Suppl 3), 5–11 (2009).

Tandon, R. et al. The impact on functioning of second-generation antipsychotic medication side effects for patients with schizophrenia: a worldwide, cross-sectional, web-based survey. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 19 , 42 (2020).

Zhang, J. P. et al. Efficacy and safety of individual second-generation vs. first-generation antipsychotics in first-episode psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 16 , 1205–1218 (2013).

Zhu, Y. et al. Antipsychotic drugs for the acute treatment of patients with a first episode of schizophrenia: a systematic review with pairwise and network meta-analyses. Lancet Psychiatry 4 , 694–705 (2017).

Kishimoto, T. et al. Relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of second-generation antipsychotics versus first-generation antipsychotics. Mol. Psychiatry 18 , 53–66 (2013).

Leucht, S. et al. Sixty years of placebo-controlled antipsychotic drug trials in acute schizophrenia: systematic review, Bayesian meta-analysis, and meta-regression of efficacy predictors. Am. J. Psychiatry 174 , 927–942 (2017).

Samara, M. T., Nikolakopoulou, A., Salanti, G. & Leucht, S. How many patients with schizophrenia do not respond to antipsychotic drugs in the short term? An analysis based on individual patient data from randomized controlled trials. Schizophr. Bull. 45 , 639–646 (2019).

Zhu, Y. et al. How well do patients with a first episode of schizophrenia respond to antipsychotics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 27 , 835–844 (2017).