Journaling for Problem Solving: Effective Techniques and Prompts

A problem is often followed by a lot of emotions, thoughts, or information. We need to navigate through this to find the best solution. This can be overwhelming. To work through the problem, you might need to get the problem out of your head and into the open. One way to do this is with a journal for problem-solving.

Table of Contents

Your problems might come in many different shapes. You might be in emotional turmoil or have to make a difficult decision. With an issue as broad as this, there isn’t one kind of journaling effective for all kinds of problems.

Let’s have a look at 4 journaling techniques and 12 prompts for problem-solving.

Types of journals for problem solving

There are several types of journals you can use for solving problems. Let’s have a look at 4 of those.

1. Thought journal

A thought journal is a type of journaling where you let your thoughts flow uninterrupted onto the paper. There is no predefined structure, no prompts, or anything else for you to think about. Your thoughts need to run freely.

You’ll often get new insights and ideas when you let your thoughts run freely. This is great for finding alternative solutions to a problem. Sometimes you won’t get any useful insights with you journal. That’s okay. You gave your brain a chance to vent and calm down, which is just as valuable.

How to use a thought journal

Thought journaling is a simple yet effective type of journaling for problem-solving. Here’s how you can do it in 3 steps:

- Take a moment to reflect on your problem. What is it? How does it make you feel? What are you thinking right now? Take a moment to be present with whatever is going on.

- Start writing using your short reflection as a starting point. Let your thoughts flow uninterrupted onto the paper.

- Continue writing until your head feels clear, you have found a solution, or you don’t want to write anymore.

You might want to go through your journal once you’ve finished to see if there are any insights you’ve missed in the middle of writing.

When to use a thought journal for problem solving

You can use a thought journal as a tool to solve any kind of problem. But it’s most effective when it’s related to high stress or anxiety.

2. Pros and cons

You probably already know the pros and cons list. It’s a classic tool to help you make a decision when you have to choose between a limited number of options.

How to use pros and cons

The pros and cons list is probably the simplest tool on this list. Here’s how you can do it yourself.

- Have a piece of paper and divide it into two columns. Name one column pros and the other cons.

- Fill the pros column with all the good things about this option

- Fill the cons column with all the negatives about this option

Once you’ve filled the columns, it’s time to reflect. How does your situation look now that you’ve weighed your options side by side?

If you have to choose between more than one option, such as which school to pick, you can go through the process with each option.

When to use a pros and cons for problem solving

The pros and cons list works best when you have to make a decision between a limited number of options. This might be choosing a school or a job. The more options you have, the less effective this method is.

3. Fake letter for problem solving

Fake letters are a popular journaling technique where you’ll write a letter to either yourself or someone else. The reason why it’s fake is that it’ll never be sent. Nobody but you will ever see it.

There are several types of fake letters. Here we’ll look into two of them. One for problems and another for difficult emotions

How to use a fake letter for problem solving

Most people find it easier to find a solution to a friend’s problem than to find one on their own. A fake letter for problem-solving takes advantage of this.

With this technique, you’ll pretend that a friend is in the exact same situation as you. They have asked for your advice on how to solve a problem they’re facing (your problem). Write a letter to your friend and give them advice on how to solve it.

Your advice might not be perfect every time, but it’ll help you think no matter what. It’ll help you move closer to a solution.

How to use a fake letter to vent

A fake letter to vent is similar to the one for problem-solving. The main difference is that you’re looking for tension relief instead of a solution here.

With this technique, you’ll write a fake letter to someone else. Someone who has frustrated you lately but that you aren’t able to tell how you feel. Pretend to write a letter to that person. In the letter, you tell them whatever it is you need to do.

Remember, you don’t have to sugarcoat anything. Let all your anger, sadness, fear, or frustration out. Write whatever it is you need to, how you need to.

When to use a fake letter for problem solving

A fake letter for problem solving is effective for any kind problem.

When to use a fake letter to vent

A fake letter to vent should be used when a person, thing, or situation provokes a lot of strong feelings in you.

Related: Find peace with a gratitude journal

4. Prioritization journal

When we have to make a difficult decision, we often have to prioritize between several things. When you know what you want, that’ll be easy.

Most people have an idea about what they want, but once they dig a little deeper, they have no idea.

A prioritization journal can help you dig past the surface and discover what you truly want. And the more you practice this, the better you’ll know yourself. The easier it’ll be to make decisions and prioritize.

Related: Learn how to increase productivity with a journal

How to use a prioritization journal

Before you can use your prioritization journal to solve problems, you have to know what your priorities are.

- Spend some time on self-discovery. Make a list of your values, dreams, and life necessities.

- Give each item on your list a number. Give the most important thing 1, the second 2, and so on. Be sure that you rank them based on how you really feel.

- Update the list frequently to ensure that it’s still relevant.

Once you have a list of priorities, you can use it as a tool every time you face a new decision. Weight how the different decisions affect the long-term effect of your goals and values. The option which benefits your top priorities is usually the best decision.

This method is similar to a goal journal. You can read more about goal journaling here .

Related: How to beat procrastination

When to use a prioritization journal for problem solving

This type of journaling can be used for any kind of problem but are most effective when you have to make a difficult decision. This might be when choosing a school, a job, or something as simple as whether you should go to the gym today.

Journaling prompts for problem solving

Prompts are short statements or questions that can help you get started with a journal and can work on numerous things. One of them is problem-solving. Here are 12 prompts you can use for your problem-solving journal.

- Describe a recent challenge that you’ve overcome. How did you do it?

- Identity a recurring issue in your life. What is it and how can you overcome it?

- Take a complex issue you’re facing and break it into as many smaller parts as possible. Which part of the problem can you solve right now?

- Think back to a situation where you had to make a tough decision. What did you chose and how did it play out?

- Think back to a time where you faced failure or setback. How did you bounce back?

- Think back to a moment where things didn’t go as planned. How did turn out?

- What is the worst thing that can happen? How likely is it that this will happen?

- Think back to a time where you successfully collaborated with someone else. How did it turn out?

- Right now, what feels best to me?

- If I make this choice, how do I think it’ll affect my future?

- Have a faced a similar problem in the past. Did I learn anything from it?

- What would I do in this situation if I didn’t care about what other people think?

Finishing thoughts

Journaling is a great tool for problem-solving. It can give you an overview of the situation, calm your thoughts and emotions, and help you make a decision that aligns best with your values.

Hopefully, you’ll find that journaling can make dealing with your problems a bit easier.

What to read about next:

The Power of Small Wins: Achieving Success One Step at a Time

Thought journal: Journaling for stress and anxiety

Productivity Journaling: Unlocking Efficiency and Success

Gratitude Journal: A Beginner’s Guide to Cultivate Gratitude

Reach Your Goals with a Goal Journal: Turn Dreams into Reality

- Recent Posts

- Personal Productivity: What It Is and How to Improve It - March 7, 2024

- Multitasking: Breaking Free from the Counterproductive Habit - January 21, 2024

- The 20-Second rule: A simple Technique for Better Habits - August 30, 2023

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, creative problem solving as overcoming a misunderstanding.

- Department of Psychology, University of Milano-Bicocca, Milan, Italy

Solving or attempting to solve problems is the typical and, hence, general function of thought. A theory of problem solving must first explain how the problem is constituted, and then how the solution happens, but also how it happens that it is not solved; it must explain the correct answer and with the same means the failure. The identification of the way in which the problem is formatted should help to understand how the solution of the problems happens, but even before that, the source of the difficulty. Sometimes the difficulty lies in the calculation, the number of operations to be performed, and the quantity of data to be processed and remembered. There are, however, other problems – the insight problems – in which the difficulty does not lie so much in the complexity of the calculations, but in one or more critical points that are susceptible to misinterpretation , incompatible with the solution. In our view, the way of thinking involved in insight problem solving is very close to the process involved in the understanding of an utterance, when a misunderstanding occurs. In this case, a more appropriate meaning has to be selected to resolve the misunderstanding (the “impasse”), the default interpretation (the “fixation”) has to be dropped in order to “restructure.” to grasp another meaning which appears more relevant to the context and the speaker’s intention (the “aim of the task”). In this article we support our view with experimental evidence, focusing on how a misunderstanding is formed. We have studied a paradigmatic insight problem, an apparent trivial arithmetical task, the Ties problem. We also reviewed other classical insight problems, reconsidering in particular one of the most intriguing one, which at first sight appears impossible to solve, the Study Window problem. By identifying the problem knots that alter the aim of the task, the reformulation technique has made it possible to eliminate misunderstanding, without changing the mathematical nature of the problem. With the experimental versions of the problems exposed we have obtained a significant increase in correct answers. Studying how an insight problem is formed, and not just how it is solved, may well become an important topic in education. We focus on undergraduate students’ strategies and their errors while solving problems, and the specific cognitive processes involved in misunderstanding, which are crucial to better exploit what could be beneficial to reach the solution and to teach how to improve the ability to solve problems.

Introduction

“A problem arises when a living creature has a goal but does not know how this goal is to be reached. Whenever one cannot go from the given situation to the desired situation simply by action, then there has to be recourse to thinking. (…) Such thinking has the task of devising some action which may mediate between the existing and the desired situations.” ( Duncker, 1945 , p. 1). We agree with Duncker’s general description of every situation we call a problem: the problem solving activity takes a central role in the general function of thought, if not even identifies with it.

So far, psychologists have been mainly interested in the solution and the solvers. But the formation of the problem remained in the shadows.

Let’s consider for example the two fundamental theoretical approaches to the study of problem solving. “What questions should a theory of problem solving answer? First, it should predict the performance of a problem solver handling specified tasks. It should explain how human problem solving takes place: what processes are used, and what mechanisms perform these processes.” ( Newell et al., 1958 , p. 151). In turn, authors of different orientations indicate as central in their research “How does the solution arise from the problem situation? In what ways is the solution of a problem attained?” ( Duncker, 1945 , p. 1) or that of what happens when you solve a problem, when you suddenly see the point ( Wertheimer, 1959 ). It is obvious, and it was inevitable, that the formation of the problem would remain in the shadows.

A theory of problem solving must first explain how the problem is constituted, and then how the solution happens, but also how it happens that it is not solved; it must explain the correct answer and with the same means the failure. The identification of the way in which the problem is constituted – the formation of the problem – and the awareness that this moment is decisive for everything that follows imply that failures are considered in a new way, the study of which should help to understand how the solution of the problems happens, but even before that, the source of the difficulty.

Sometimes the difficulty lies in the calculation, the number of operations to be performed, and the quantity of data to be processed and remembered. Take the well-known problems studied by Simon, Crypto-arithmetic task, for example, or the Cannibals and Missionaries problem ( Simon, 1979 ). The difficulty in these problems lies in the complexity of the calculation which characterizes them. But, the text and the request of the problem is univocally understood by the experimenter and by the participant in both the explicit ( said )and implicit ( implied ) parts. 1 As Simon says, “Subjects do not initially choose deliberately among problem representations, but almost always adopt the representation suggested by the verbal problem statement” ( Kaplan and Simon, 1990 , p. 376). The verbal problem statement determines a problem representation, implicit presuppositions of which are shared by both.

There are, however, other problems where the usual (generalized) interpretation of the text of the problem (and/or the associated figure) prevents and does not allow a solution to be found, so that we are soon faced with an impasse. We’ll call this kind of problems insight problems . “In these cases, where the complexity of the calculations does not play a relevant part in the difficulty of the problem, a misunderstanding would appear to be a more appropriate abstract model than the labyrinth” ( Mosconi, 2016 , p. 356). Insight problems do not arise from a fortuitous misunderstanding, but from a deliberate violation of Gricean conversational rules, since the implicit layer of the discourse (the implied ) is not shared both by experimenter and participant. Take for example the problem of how to remove a one-hundred dollar bill without causing a pyramid balanced atop the bill to topple: “A giant inverted steel pyramid is perfectly balanced on its point. Any movement of the pyramid will cause it to topple over. Underneath the pyramid is a $100 bill. How would you remove the bill without disturbing the pyramid?” ( Schooler et al., 1993 , p. 183). The solution is burn or tear the dollar bill but people assume that the 100 dollar bill must not be damaged, but contrary to his assumption, this is in fact the solution. Obviously this is not a trivial error of understanding between the two parties, but rather a misunderstanding due to social conventions, and dictated by conversational rules. It is the essential condition for the forming of the problem and the experimenter has played on the very fact that the condition was not explicitly stated (see also Bulbrook, 1932 ).

When insight problems are used in research, it could be said that the researcher sets a trap, more or less intentionally, inducing an interpretation that appears to be pertinent to the data and to the text; this interpretation is adopted more or less automatically because it has been validated by use but the default interpretation does not support understanding, and misunderstanding is inevitable; as a result, sooner or later we come up against an impasse. The theory of misunderstanding is supported by experimental evidence obtained by Mosconi in his research on insight problem solving ( Mosconi, 1990 ), and by Bagassi and Macchi on problem solving, decision making and probabilistic reasoning ( Bagassi and Macchi, 2006 , 2016 ; Macchi and Bagassi, 2012 , 2014 , 2015 , 2020 ; Macchi, 1995 , 2000 ; Mosconi and Macchi, 2001 ; Politzer and Macchi, 2000 ).

The implication of the focus on problem forming for education is remarkable: everything we say generates a communicative and therefore interpretative context, which is given by cultural and social assumptions, default interpretations, and attribution of intention to the speaker. Since the text of the problem is expressed in natural language, it is affected, it shares the characteristics of the language itself. Natural language is ambiguous in itself, differently from specialized languages (i.e., logical and statistical ones), which presuppose a univocal, unambiguous interpretation. The understanding of what a speaker means requires a disambiguation process centered on the intention attribution.

Restructuring as Reinterpreting

Traditionally, according to the Gestaltists, finding the solution to an insight problem is an example of “productive thought.” In addition to the reproductive activities of thought, there are processes which create, “produce” that which does not yet exist. It is characterized by a switch in direction which occurs together with the transformation of the problem or a change in our understanding of an essential relationship. The famous “aha!” experience of genuine insight accompanies this change in representation, or restructuring. As Wertheimer says: “… Solution becomes possible only when the central features of the problem are clearly recognized, and paths to a possible approach emerge. Irrelevant features must be stripped away, core features must become salient, and some representation must be developed that accurately reflects how various parts of the problem fit together; relevant relations among parts, and between parts and whole, must be understood, must make sense” ( Wertheimer, 1985 , p. 23).

The restructuring process circumscribed by the Gestaltists to the representation of the perceptual stimulus is actually a general feature of every human cognitive activity and, in particular, of communicative interaction, which allows the understanding, the attribution of meaning, thus extending to the solution of verbal insight problems. In this sense, restructuring becomes a process of reinterpretation.

We are able to get out of the impasse by neglecting the default interpretation and looking for another one that is more pertinent to the situation and which helps us grasp the meaning that matches both the context and the speaker’s intention; this requires continuous adjustments until all makes sense.

In our perspective, this interpretative function is a characteristic inherent to all reasoning processes and is an adaptive characteristic of the human cognitive system in general ( Levinson, 1995 , 2013 ; Macchi and Bagassi, 2019 ; Mercier and Sperber, 2011 ; Sperber and Wilson, 1986/1995 ; Tomasello, 2009 ). It guarantees cognitive economy when meanings and relations are familiar, permitting recognition in a “blink of an eye.” This same process becomes much more arduous when meanings and relations are unfamiliar, obliging us to face the novel. When this happens, we have to come to terms with the fact that the usual, default interpretation will not work, and this is a necessary condition for exploring other ways of interpreting the situation. A restless, conscious and unconscious search for other possible relations between the parts and the whole ensues until everything falls into place and nothing is left unexplained, with an interpretative heuristic-type process. Indeed, the solution restructuring – is a re -interpretation of the relationship between the data and the aim of the task, a search for the appropriate meaning carried out at a deeper level, not by automaticity. If this is true, then a disambiguant reformulation of the problem that eliminates the trap into which the subject has fallen, should produce restructuring and the way to the solution.

Insight Problem Solving as the Overcoming of a Misunderstanding: The Effect of Reformulation

In this article we support our view with experimental evidence, focusing on how a misunderstanding is formed, and how a pragmatic reformulation of the problem, more relevant to the aim of the task, allows the text of the problem to be interpreted in accordance with the solution.

We consider two paradigmatic insight problems, the intriguing Study Window problem, which at first sight appears impossible to solve, and an apparent trivial arithmetical task, the Ties problem ( Mosconi and D’Urso, 1974 ).

The Study Window problem

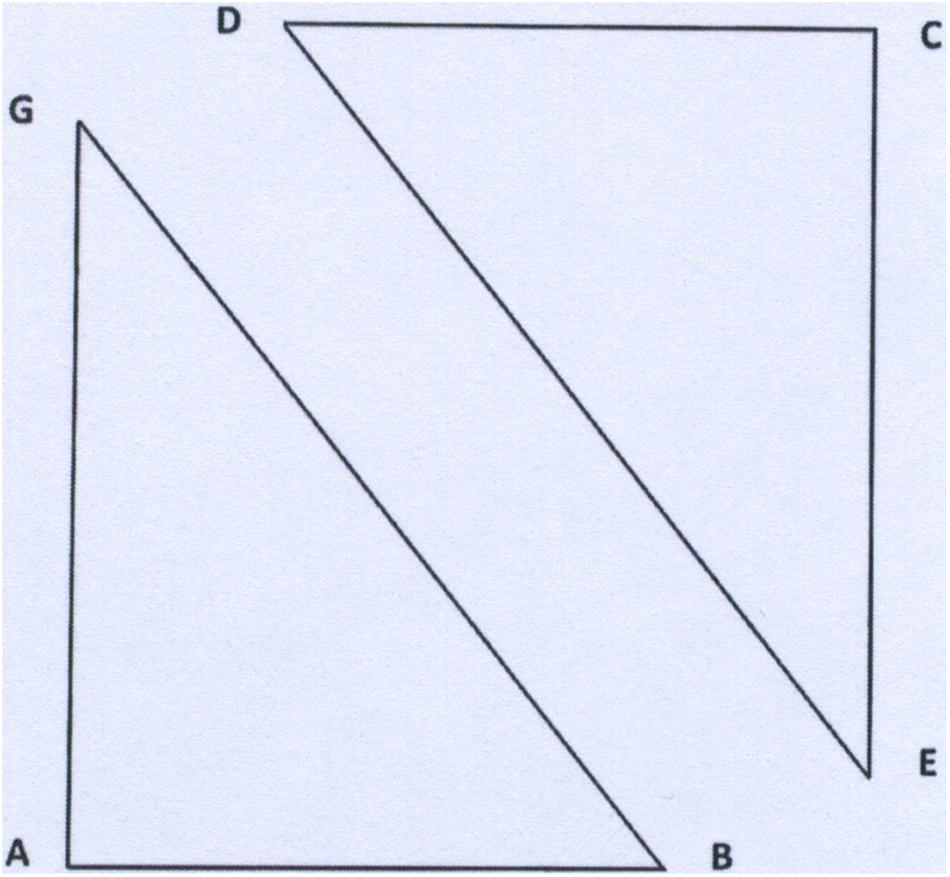

The study window measures 1 m in height and 1 m wide. The owner decides to enlarge it and calls in a workman. He instructs the man to double the area of the window without changing its shape and so that it still measures 1 m by 1 m. The workman carried out the commission. How did he do it?

This problem was investigated in a previous study ( Macchi and Bagassi, 2015 ). For all the participants the problem appeared impossible to solve, and nobody actually solved it. The explanation we gave for the difficulty was the following: “The information provided regarding the dimensions brings a square form to mind. The problem solver interprets the window to be a square 1 m high by 1 m wide, resting on one side. Furthermore, the problem states “without changing its shape,” intending geometric shape of the two windows (square, independently of the orientation of the window), while the problem solver interprets this as meaning the phenomenic shape of the two windows (two squares with the same orthogonal orientation)” ( Macchi and Bagassi, 2015 , p. 156). And this is where the difficulty of the problem lies, in the mental representation of the window and the concurrent interpretation of the text of the problem. Actually, spatial orientation is a decisive factor in the perception of forms. “Two identical shapes seen from different orientations take on a different phenomenic identity” ( Mach, 1914 ).

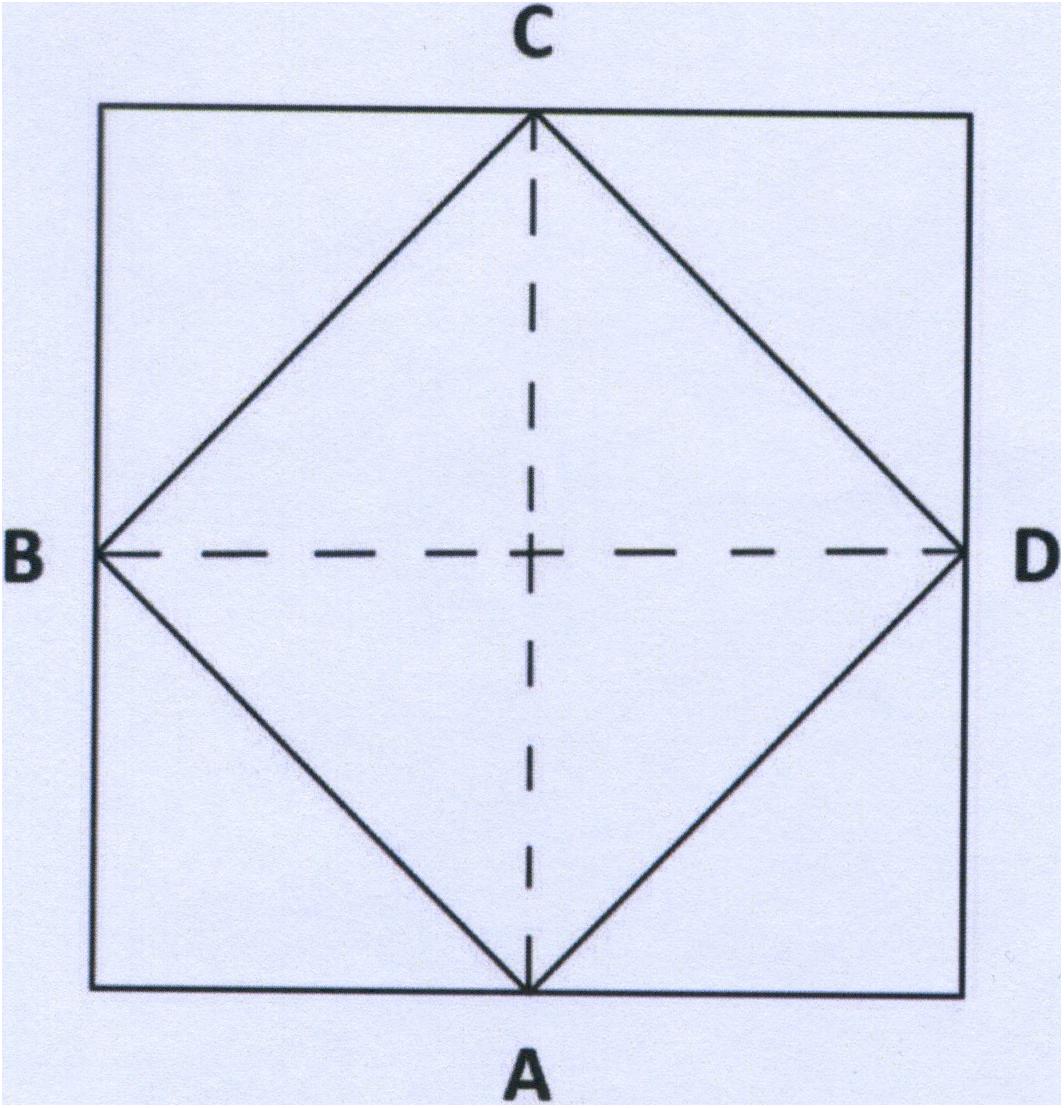

The solution is to be found in a square (geometric form) that “rests” on one of its angles, thus becoming a rhombus (phenomenic form). Now the dimensions given are those of the two diagonals of the represented rhombus (ABCD).

Figure 1. The study window problem solution.

The “inverted” version of the problem gave less trouble:

[…] The owner decides to make it smaller and calls in a workman. He instructs the man to halve the area of the window […].

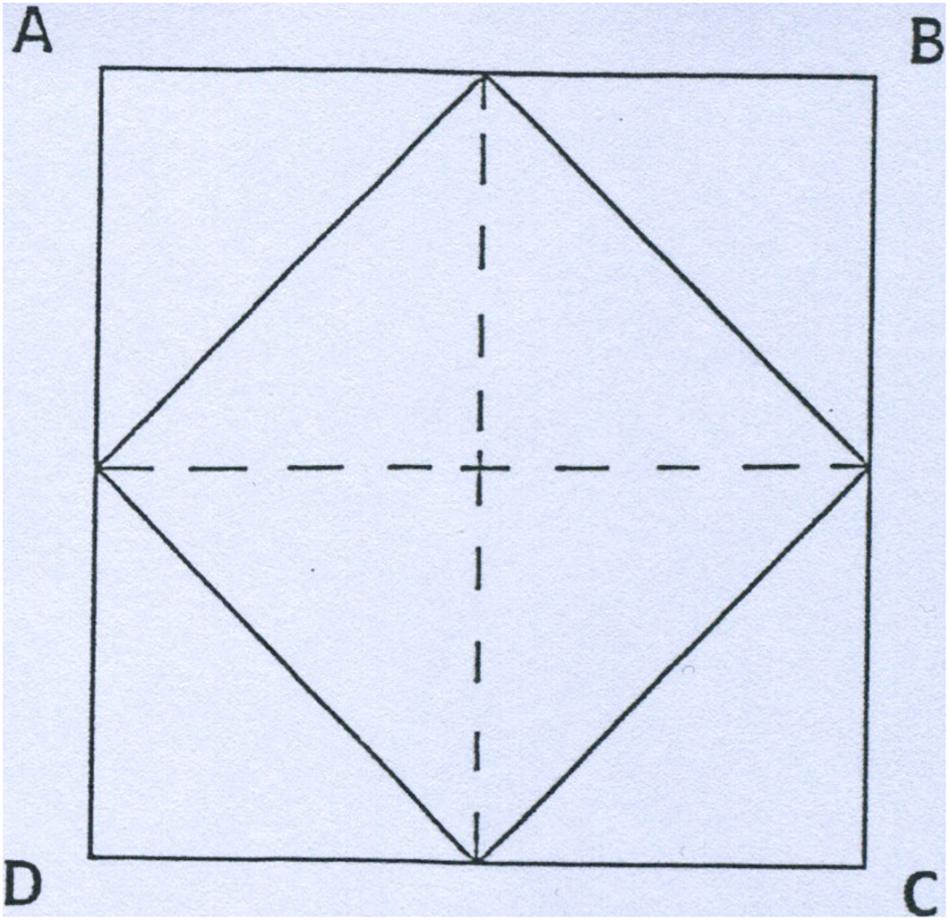

Figure 2. The inverted version.

With this version, 30% of the participants solved the problem ( n = 30). They started from the representation of the orthogonal square (ABCD) and looked for the solution within the square, trying to respect the required height and width of the window, and inevitably changing the orientation of the internal square. This time the height and width are the diagonals, rather than the side (base and height) of the square.

Eventually, in another version (the “orientation” version) it was explicit that orientation was not a mandatory attribute of the shape, and this time 66% of the participants found the solution immediately ( n = 30). This confirms the hypothesis that an inappropriate representation of the relation between the orthogonal orientation of the square and its geometric shape is the origin of the misunderstanding .

The “orientation” version:

A study window measures 1 m in height and 1 m wide. The owner decides to make it smaller and calls in a workman. He instructs the man to halve the area of the window: the workman can change the orientation of the window, but not its shape and in such a way that it still measures one meter by one meter. The workman carries out the commission. How did he do it?

While with the Study window problem the subjects who do not arrive at the solution, and who are the totality, know they are wrong, with the problem we are now going to examine, the Ties problem, those who are wrong do not realize it at all and the solution they propose is experienced as the correct solution.

The Ties Problem ( Mosconi and D’Urso, 1974 )

Peter and John have the same number of ties.

Peter gives John five of his ties.

How many ties does John have now more than Peter?

We believe that the seemingly trivial problem is actually the result of the simultaneous activation and mutual interference of complex cognitive processes that prevent its solution.

The problem has been submitted to 50 undergraduate students of the Humanities Faculty of the University of Milano-Bicocca. The participants were tested individually and were randomly assigned to three groups: control version ( n = 50), experimental version 2 ( n = 20), and experimental version 3 ( n = 23). All groups were tested in Italian. Each participant was randomly assigned to one of the conditions and received a form containing only one version of the two assigned problems. There was no time limit. They were invited to think aloud and their spontaneous justifications were recorded and then transcribed.

The correct answer is obviously “ten,” but it must not be so obvious if it is given by only one third of the subjects (32%), while the remaining two thirds give the wrong answer “five,” which is so dominant.

If we consider the text of the problem from the point of view of the information explicitly transmitted ( said ), we have that it only theoretically provides the necessary information to reach the solution and precisely that: (a) the number of ties initially owned by P. and J. is equal, (b) P. gives J. five of his ties. However, the subjects are wrong. What emerges, however, from the spontaneous justifications given by the subjects who give the wrong answer is that they see only the increase of J. and not the consequent loss of P. by five ties. We report two typical justifications: “P. gives five of his to J., J. has five more ties than P., the five P. gave him” and also “They started from the same number of ties, so if P. gives J. five ties, J. should have five more than P.”

Slightly different from the previous ones is the following recurrent answer, in which the participants also consider the decrease of P. as well as the increase of J.: “I see five ties at stake, which are the ones that move,” or also “There are these five ties that go from one to the other, so one has five ties less and the other has five more,” reaching however the conclusion similar to the previous one that “J. has five ties more, because the other gave them to him.” 2

Almost always the participants who answer “five” use a numerical example to justify the answer given or to find a solution to the problem, after some unsuccessful attempts. It is paradoxical how many of these participants accept that the problem has two solutions, one “five ties” obtained by reasoning without considering a concrete number of initial ties, owned by P. and J., the other “ten ties” obtained by using a numerical example. So, for example, we read in the protocol of a participant who, after having answered “five more ties,” using a numerical example, finds “ten” of difference between the ties of P. and those of J.: “Well! I think the “five” is still more and more exact; for me this one has five more, period and that’s it.” “Making the concrete example: “ten” – he chases another subject on an abstract level. I would be more inclined to another formula, to five.”

About half of the subjects who give the answer “five,” in fact, at first refuse to answer because “we don’t know the initial number and therefore we can’t know how many ties J. has more than P.,” or at the most they answer: “J. has five ties more, P. five less, more we can’t know, because a data is missing.”

Even before this difficulty, so to speak, operational, the text of the problem is difficult because in it the quantity relative to the decrease of P. remains implicit (−5). The resulting misunderstanding is that if the quantity transferred is five ties, the resulting difference is only five ties: if the ties that P. gives to J. are five, how can J. have 10 ties more than P.?

So the difficulty of the problem lies in the discrepancy between the quantity transferred and the bidirectional effect that this quantity determines with its displacement. Resolving implies a restructuring of the sentence: “Peter gives John five of his ties (and therefore he loses five).” And this is precisely the reasoning carried out by those subjects who give the right answer “ten.”

We have therefore formulated a new version in which a pair of verbs should make explicit the loss of P.:

Peter loses five of his ties and John takes them.

However, the results obtained with this version, submitted to 20 other subjects, substantially confirm the results obtained with the original version: the correct answers are 17% (3/20) and the wrong ones 75% (15/20). From a Chi-square test (χ 2 = 2,088 p = 0.148) it results no significant difference between the two versions.

If we go to read the spontaneous justifications, we find that the subjects who give the answer “five” motivate it in a similar way to the subjects of the original version. So, for example: “P. loses five, J. gets them, so J. has five ties more than P.”

The decrease of P. is still not perceived, and the discrepancy between the lost amount of ties and the double effect that this quantity determines with its displacement persists.

Therefore, a new version has been realized in which the amount of ties lost by P. has nothing to do with J’s acquisition of five ties, the two amounts of ties are different and then they are perceived as decoupled, so as to neutralize the perceptual-conceptual factor underlying it.

Peter loses five of his ties and John buys five new ones.

It was submitted to 23 participants. Of them, 17 (74%) gave the answer “ten” and only 3 (13%) the answer “five.” There was a significant difference (χ 2 = 16,104 p = 0.000) between the results obtained using the present experimental version and the results from the control version. The participants who give the correct solution “ten” mostly motivate their answer as follows: “P. loses five and therefore J. has also those five that P. lost; he buys another five, there are ten,” declaring that he “added to the five that P. had lost the five that J. had bought.” The effectiveness of the experimental manipulation adopted is confirmed. 3

The satisfactory results obtained with this version cannot be attributed to the use of two different verbs, which proved to be ineffective (see version 2), but to the splitting, and consequent differentiation (J. has in addition five new ties), of the two quantities.

This time, the increase of J. and the decrease of P. are grasped as simultaneous and distinct and their combined effect is not identified with one or the other, but is equal to the sum of +5 and −5 in absolute terms.

The hypothesis regarding the effect of reformulation has also been confirmed in classical insight problems such as the Square and the Parallelogram ( Wertheimer, 1925 ), the Pigs in a Pen ( Schooler et al., 1993 ), the Bat & Ball ( Frederick, 2005 ) in recent studies ( Macchi and Bagassi, 2012 , 2015 ) which showed a dramatic increase in the number of solutions.

In their original version these problems are true brain teasers, and the majority of participants in these studies needed them to be reformulated in order to reach the solution. In Appendix B we present in detail the results obtained (see Table 1 ). Below we report, for each problem, the text of the original version in comparison with the reformulated experimental version.

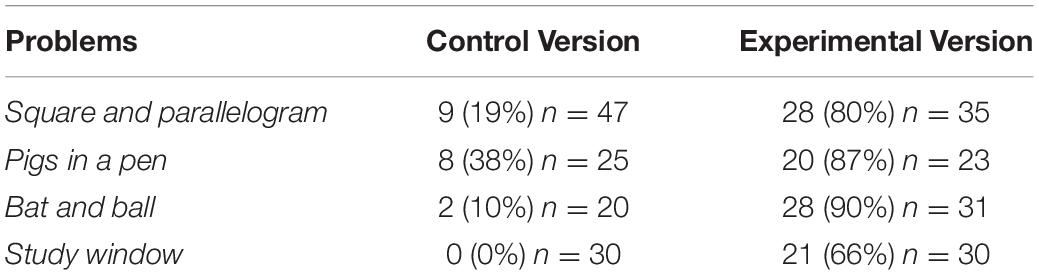

Table 1. Percentages of correct solutions with reformulated experimental versions.

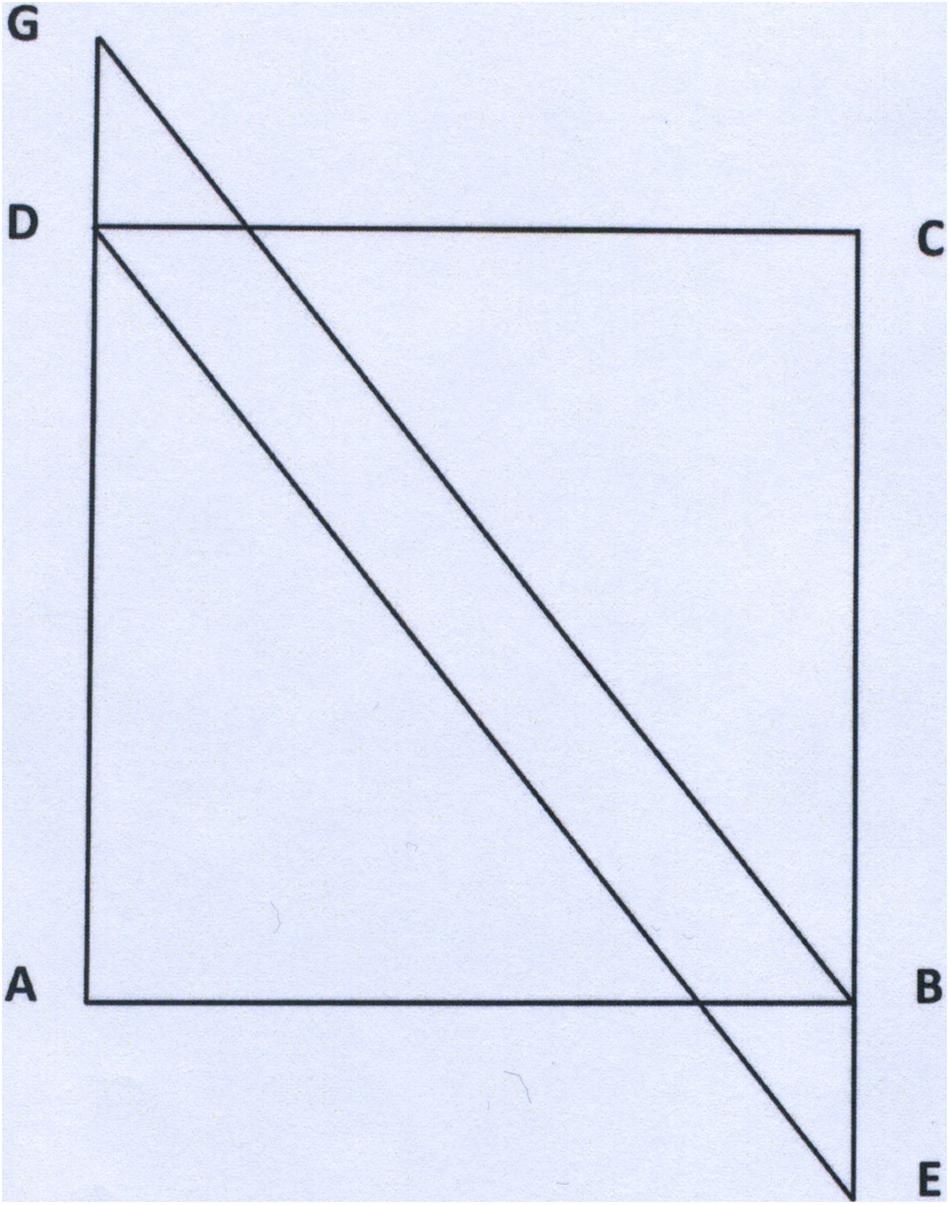

Square and Parallelogram Problem ( Wertheimer, 1925 )

Given that AB = a and AG = b, find the sum of the areas of square ABCD and parallelogram EBGD ( Figures 3 , 4 ).

Figure 3. The square and parallelogram problem.

Figure 4. Solution.

Experimental Version

Given that AB = a and AG = b , find the sum of the areas of the two partially overlapping figures .

Pigs in a Pen Problem ( Schooler et al., 1993 )

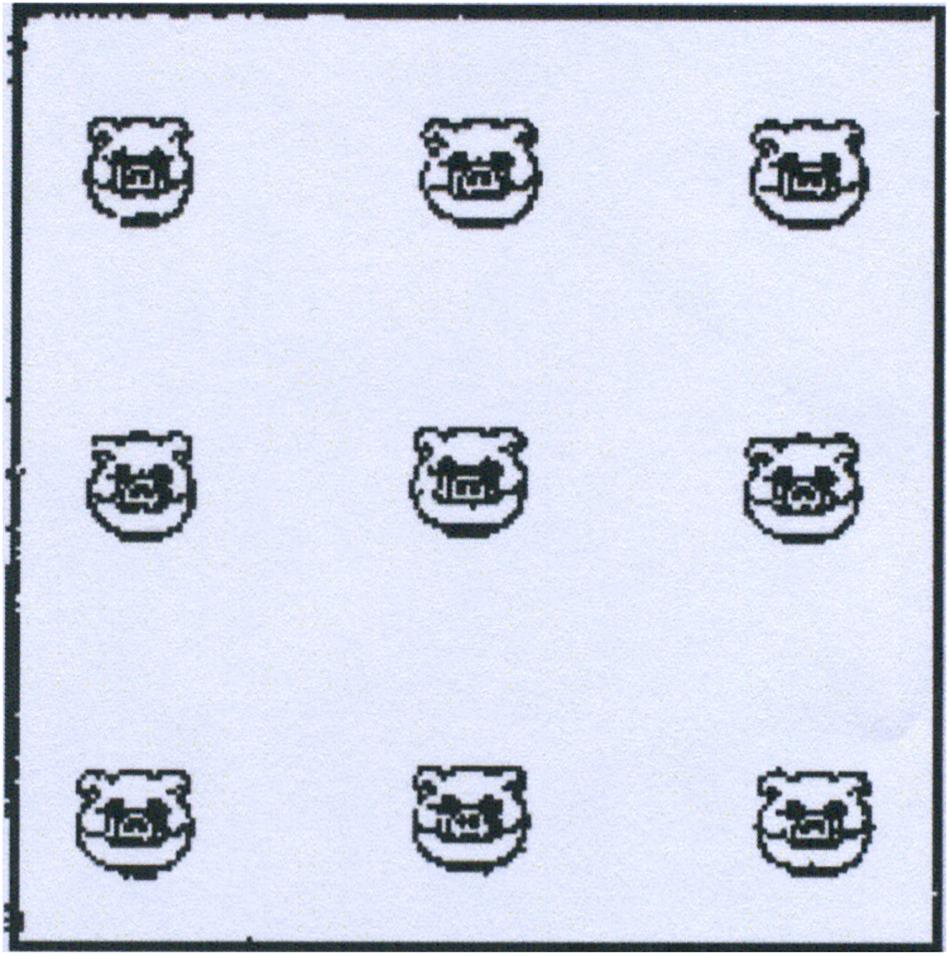

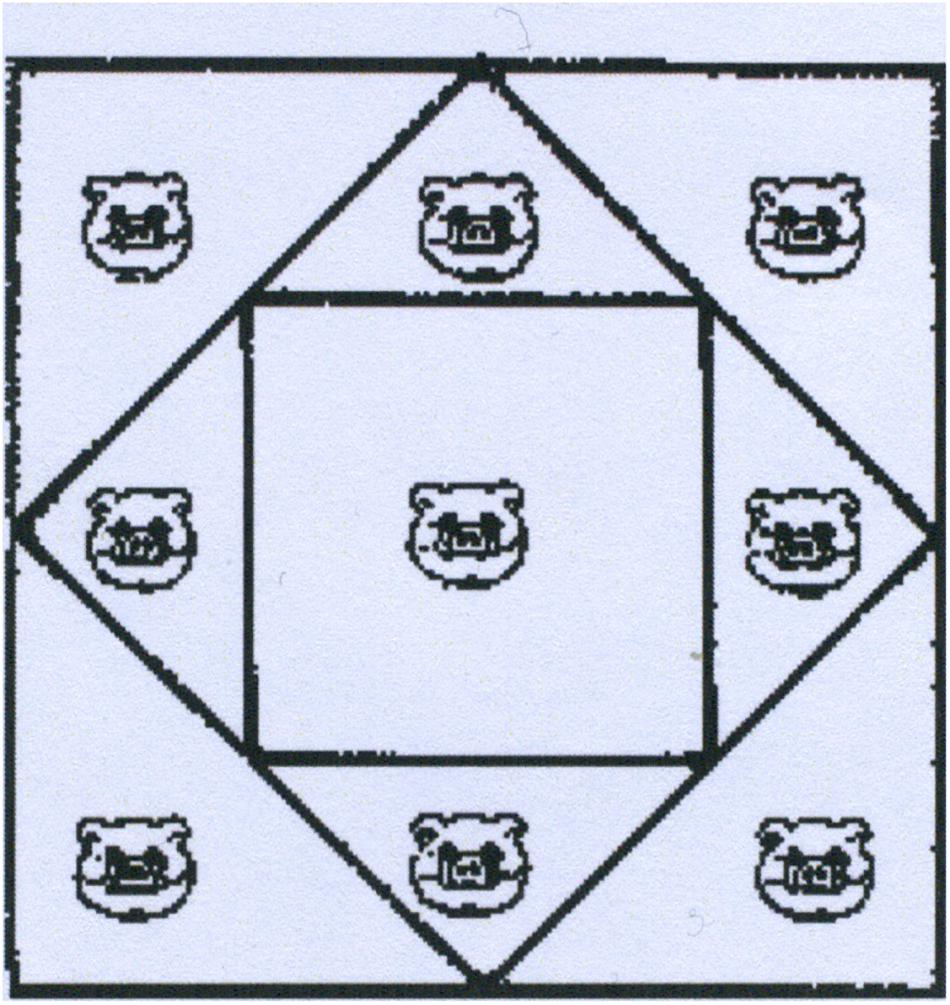

Nine pigs are kept in a square pen . Build two more square enclosures that would put each pig in a pen by itself ( Figures 5 , 6 ).

Figure 5. The pigs in a pen problem.

Figure 6. Solution.

Nine pigs are kept in a square pen. Build two more squares that would put each pig in a by itself .

Bat and Ball Problem ( Frederick, 2005 )

A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $ 1.00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost? ___cents.

A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $ 1.00 more than the ball. Find the cost of the bat and of the ball .

Once the problem knots that alter the aim of the task have been identified, the reformulation technique can be a valid didactic tool, as it allows to reveal the misunderstanding and to eliminate it without changing the mathematical nature of the problem. The training to creativity would consist in this sense in training to have interpretative keys different from the usual, when the difficulty cannot be addressed through computational techniques.

Closing Thoughts

By identifying the misunderstanding in problem solving, the reformulation technique has made it possible to eliminate the problem knots, without changing the mathematical nature of the problem. With the experimental reformulated versions of paradigmatic problems, both apparent trivial tasks or brain teasers have obtained a significant increase in correct answers.

Studying how an insight problem is formed, and not just how it is solved, may well become an important topic in education. We focus on undergraduate students’ strategies and their errors while solving problems, and the specific cognitive processes involved in misunderstanding, which are crucial to better exploit what could be beneficial to reach the solution and to teach how to improve the ability to solve problems.

Without violating the need for the necessary rigor of a demonstration, for example, it is possible to organize the problem-demonstration discourse according to a different criterion, precisely by favoring the psychological needs of the subject to whom the explanation discourse is addressed, taking care to organize the explanation with regard to the way his mind works, to what can favor its comprehension and facilitate its memory.

On the other hand, one of the criteria traditionally followed by mathematicians in constructing, for example, demonstrations, or at least in explaining them, is to never make any statement that is not supported by the elements provided above. In essence, in the course of the demonstration nothing is anticipated, and indeed it happens frequently that the propositions directly relevant and relevant to the development of the reasoning (for example, the steps of a geometric demonstration) are preceded by digressions intended to introduce and deal with the elements that legitimize them. As a consequence of such an expositive formalism, the recipient of the speech (the student) often finds himself in the situation of being led to the final conclusion a bit like a blind man who, even though he knows the goal, does not see the way, but can only control step by step the road he is walking along and with difficulty becomes aware of the itinerary.

The text of every problem, if formulated in natural language, has a psychorhetoric dimension, in the sense that in every speech, that is in the production and reception of every speech, there are aspects related to the way the mind works – and therefore psychological and rhetorical – that are decisive for comprehensibility, expressive adequacy and communicative effectiveness. It is precisely to these aspects that we refer to when we talk about the psychorhetoric dimension. Rhetoric, from the point of view of the broadcaster, has studied discourse in relation to the recipient, and therefore to its acceptability, comprehensibility and effectiveness, so that we can say that rhetoric has studied discourse “psychologically.”

Adopting this perspective, the commonplace that the rhetorical dimension only concerns the common discourse, i.e., the discourse that concerns debatable issues, and not the scientific discourse (logical-mathematical-demonstrative), which would be exempt from it, is falling away. The matter dealt with, the truth of what is actually said, is not sufficient to guarantee comprehension.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

LM and MB devised the project, developed the theory, carried out the experiment and wrote the manuscript. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

- ^ The theoretical framework assumed here is Paul Grice’s theory of communication (1975) based on the existence in communication of the explicit layer ( said ) and of the implicit ( implied ), so that the recognition of the communicative intention of the speaker by the interlocutor is crucial for comprehension.

- ^ A participant who after having given the solution “five” corrects himself in “ten” explains the first answer as follows: “it is more immediate, in my opinion, to see the real five ties that are moved, because they are five things that are moved; then as a more immediate answer is ‘five,’ because it is something more real, less mathematical.”

- ^ The factor indicated is certainly the main responsible for the answer “five,” but not the only one (see the Appendix for a pragmatic analysis of the text).

- ^ Versions and results of the problems exposed are already published in Macchi e Bagassi 2012, 2014, 2015.

Bagassi, M., and Macchi, L. (2006). Pragmatic approach to decision making under uncertainty: the case of the disjunction effect. Think. Reason. 12, 329–350. doi: 10.1080/13546780500375663

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bagassi, M., and Macchi, L. (2016). “The interpretative function and the emergence of unconscious analytic thought,” in Cognitive Unconscious and Human Rationality , eds L. Macchi, M. Bagassi, and R. Viale (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 43–76.

Google Scholar

Bulbrook, M. E. (1932). An experimental inquiry into the existence and nature of “insight”. Am. J. Psycho. 44, 409–453. doi: 10.2307/1415348

Duncker, K. (1945). “On problem solving,” in Psychological Monographs , Vol. 58, (Berlin: Springer), I–IX;1–113. Original in German, Psychologie des produktiven Denkens. doi: 10.1037/h0093599

Frederick, S. (2005). Cognitive reflection and decision making. J. Econ. Perspect. 19, 25–42. doi: 10.1257/089533005775196732

Kahneman, D. (2003). A perspective on judgment and choice: mapping bounded rationality. Am. Psychol. 58, 697–720. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.9.697

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kaplan, C. A., and Simon, H. A. (1990). In search of insight. Cogn. Psychol. 22, 374–419. doi: 10.1016/0010-0285(90)90008-R

Levinson, S. C. (1995). “Interactional biases in human thinking,” in Social Intelligence and Interaction , ed. E. N. Goody (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 221–261. doi: 10.1017/cbo9780511621710.014

Levinson, S. C. (2013). “Cross-cultural universals and communication structures,” in Language, Music, and the Brain: A Mysterious Relationship , ed. M. A. Arbib (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 67–80. doi: 10.7551/mitpress/9780262018104.003.0003

Macchi, L. (1995). Pragmatic aspects of the base-rate fallacy. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 4, 188–207. doi: 10.1080/14640749508401384

Macchi, L. (2000). Partitive formulation of information in probabilistic reasoning: beyond heuristics and frequency format explanations. Organ. Behav. Hum. 82, 217–236. doi: 10.1006/obhd.2000.2895

Macchi, L., and Bagassi, M. (2012). Intuitive and analytical processes in insight problem solving: a psycho-rhetorical approach to the study of reasoning. Mind Soc. 11, 53–67. doi: 10.1007/s11299-012-0103-3

Macchi, L., and Bagassi, M. (2014). The interpretative heuristic in insight problem solving. Mind Soc. 13, 97–108. doi: 10.1007/s11299-014-0139-7

Macchi, L., and Bagassi, M. (2015). When analytic thought is challenged by a misunderstanding. Think. Reas. 21, 147–164. doi: 10.4324/9781315144061-9

Macchi, L., and Bagassi, M. (2019). The argumentative and the interpretative functions of thought: two adaptive characteristics of the human cognitive system. Teorema 38, 87–96.

Macchi, L., and Bagassi, M. (2020). “Bounded rationality and problem solving: the interpretative function of thought,” in Handbook of Bounded Rationality , ed. Riccardo Viale (London: Routledge).

Mach, E. (1914). The Analysis of Sensations. Chicago IL: Open Court.

Mercier, H., and Sperber, D. (2011). Why do human reason? Arguments for an argumentative theory. Behav. Brain Sci. 34, 57–74. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x10000968

Mosconi, G. (1990). Discorso e Pensiero. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Mosconi, G. (2016). “Closing thoughts,” in Cognive Unconscious and Human rationality , eds L. Macchi, M. Bagassi, and R. Viale (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 355–363. Original in Italian Discorso e pensiero.

Mosconi, G., and D’Urso, V. (1974). Il Farsi e il Disfarsi del Problema. Firenze: Giunti-Barbera.

Mosconi, G., and Macchi, L. (2001). The role of pragmatic rules in the conjunction fallacy. Mind Soc. 3, 31–57. doi: 10.1007/bf02512074

Newell, A., Shaw, J. C., and Simon, H. A. (1958). Elements of a theory of human problem solving. Psychol. Rev. 65, 151–166. doi: 10.1037/h0048495

Politzer, G., and Macchi, L. (2000). Reasoning and pragmatics. Mind Soc. 1, 73–93. doi: 10.1007/BF02512230

Schooler, J. W., Ohlsson, S., and Brooks, K. (1993). Thoughts beyond words: when language overshadows insight. J. Exp. Psychol. 122, 166–183. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.122.2.166

Simon, H. A. (1979). Information processing models of cognition. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 30, 363–396. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.30.020179.002051

Sperber, D., and Wilson, D. (1986/1995). Relevance: Communication and cognition. Oxford: Blackwell.

Tomasello, M. (2009). Why We Cooperate. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. doi: 10.7551/mitpress/8470.001.0001

Wertheimer, M. (1925). Drei Abhandlungen zur Gestalttheorie. Erlangen: Verlag der Philosophischen Akademie.

Wertheimer, M. (1959). Productive Thinking. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Wertheimer, M. (1985). A gestalt perspective on computer simulations of cognitive processes. Comput. Hum. Behav. 1, 19–33. doi: 10.1016/0747-5632(85)90004-4

Pragmatic analysis of the problematic loci of the Ties problem, which emerged from the spontaneous verbalizations of the participants:

- “the same number of ties”

This expression is understood as a neutral information, a kind of base or sliding plane on which the transfer of the five ties takes place and, in fact, these subjects motivate their answer “five” with: “there is this transfer of five ties from P. to J. ….”

- “5 more, 5 less”

We frequently resort to similar expressions in situations where, if I have five units more than another, the other has five less than me and the difference between us is five.

Consider, for example, the case of the years: say that J. is five years older than P. means to say that P. is five years younger than J. and that the difference in years between the two is five, not ten.

In comparisons, we evaluate the difference with something used as a term of reference, for example the age of P., which serves as a basis, the benchmark, precisely.

- “he gives”

The verb “to give” conveys the concept of the growth of the recipient, not the decrease of the giver, therefore, contributes to the crystallization of the “same number,” preventing to grasp the decrease of P.

Appendix B 4

Given that AB = a and AG = b, find the sum of the areas of square ABCD and parallelogram EBGD .

Typically, problem solvers find the problem difficult and fail to see that a is also the altitude of parallelogram EBGD. They tend to calculate its area with onerous and futile methods, while the solution can be reached with a smart method, consisting of restructuring the entire given shape into two partially overlapping triangles ABG and ECD. The sum of their areas is 2 x a b /2 = a b . Moreover, by shifting one of the triangles so that DE coincides with GB, the answer is “ a b ,” which is the area of the resultant rectangle. Referring to a square and a parallelogram fixes a favored interpretation of the perceptive stimuli, according to those principles of perceptive organization thoroughly studied by the Gestalt Theory. It firmly sets the calculation of the area on the sum of the two specific shapes dealt with in the text, while, the problem actually requires calculation of the area of the shape, however organized, as the sum of two triangles rectangles, or the area of only one rectangle, as well as the sum of square and parallelogram. Hence, the process of restructuring is quite difficult.

To test our hypotheses we formulated an experimental version:

In this formulation of the problem, the text does not impose constraints on the interpretation/organization of the figure, and the spontaneous, default interpretation is no longer fixed. Instead of asking for “the areas of square and parallelogram,” the problem asks for the areas of “the two partially overlapping figures.” We predicted that the experimental version would allow the subjects to see and consider the two triangles also.

Actually, we found that 80% of the participants (28 out of 35) gave a correct answer, and most of them (21 out of 28) gave the smart “two triangles” solution. In the control version, on the other hand, only 19% (9 out of 47) gave the correct response, and of these only two gave the “two triangles” solution.

The findings were replicated in the “Pigs in a pen” problem:

Nine pigs are kept in a square pen . Build two more square enclosures that would put each pig in a pen by itself.

The difficulty of this problem lies in the interpretation of the request, nine pigs each individually enclosed in a square pen, having only two more square enclosures. This interpretation is supported by the favored, orthogonal reference scheme, with which we represent the square. This privileged organization, according to our hypothesis, is fixed by the text which transmits the implicature that the pens in which the piglets are individually isolated must be square in shape too. The function of enclosure wrongfully implies the concept of a square. The task, on the contrary, only requires to pen each pig.

Once again, we created an experimental version by reformulating the problem, eliminating the word “enclosure” and the phrase “in a pen.” The implicit inference that the pen is necessarily square is not drawn.

The experimental version yielded 87% correct answers (20 out of 23), while the control version yielded only 38% correct answers (8 out of 25).

The formulation of the experimental versions was more relevant to the aim of the task, and allowed the perceptual stimuli to be interpreted in accordance with the solution.

The relevance of text and the re-interpretation of perceptual stimuli, goal oriented to the aim of the task, were worked out in unison in an interrelated interpretative “game.”

We further investigated the interpretative activity of thinking, by studying the “Bat and ball” problem, which is part of the CRT. Correct performance is usually considered to be evidence of reflective cognitive ability (correlated with high IQ scores), versus intuitive, erroneous answers to the problem ( Frederick, 2005 ).

Bat and Ball problem

A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $ 1.00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?___cents

Of course the answer which immediately comes to mind is 10 cents, which is incorrect as, in this case, the difference between $ 1.00 and 10 cents is only 90 cents, not $1.00 as the problem stipulates. The correct response is 5 cents.

Number physiognomics and the plausibility of the cost are traditionally considered responsible for this kind of error ( Frederick, 2005 ; Kahneman, 2003 ).

These factors aside, we argue that if the rhetoric structure of the text is analyzed, the question as formulated concerns only the ball, implying that the cost of the bat is already known. The question gives the key to the interpretation of what has been said in each problem and, generally speaking, in every discourse. Given data, therefore, is interpreted in the light of the question. Hence, “The bat costs $ 1.00 more than” becomes “The bat costs $ 1.00,” by leaving out “more than.”

According to our hypothesis, independently of the different cognitive styles, erroneous responses could be the effect of the rhetorical structure of the text, where the question is not adequate to the aim of the task. Consequently, we predicted that if the question were to be reformulated to become more relevant, the subjects would find it easier to grasp the correct response. In the light of our perspective, the cognitive abilities involved in the correct response were also reinterpreted. Consequently, we reformulated the text as follows in order to eliminate this misleading inference:

This time we predicted an increase in the number of correct answers. The difference in the percentages of correct solutions was significant: in the experimental version 90% of the participants gave a correct answer (28 out of 31), and only 10% (2 out of 20) answered correctly in the control condition.

The simple reformulation of the question, which expresses the real aim of the task (to find the cost of both items), does not favor the “short circuit” of considering the cost of the bat as already known (“$1,” by leaving out part of the phrase “more than”).

It still remains to be verified if those subjects who gave the correct response in the control version have a higher level of cognitive reflexive ability compared to the “intuitive” respondents. This has been the general interpretation given in the literature to the difference in performance.

We think it is a matter of a particular kind of reflexive ability, due to which the task is interpreted in the light of the context and not abstracting from it. The difficulty which the problem implicates does not so much involve a high level of abstract reasoning ability as high levels of pragmatic competence, which disambiguates the text. So much so that, intervening only on the pragmatic level, keeping numbers physiognomics and maintaining the plausible costs identical, the problem becomes a trivial arithmetical task.

Keywords : creative problem solving, insight, misunderstanding, pragmatics, language and thought

Citation: Bagassi M and Macchi L (2020) Creative Problem Solving as Overcoming a Misunderstanding. Front. Educ. 5:538202. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.538202

Received: 26 February 2020; Accepted: 29 October 2020; Published: 03 December 2020.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2020 Bagassi and Macchi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Laura Macchi, [email protected]

This article is part of the Research Topic

Psychology and Mathematics Education

Journal Prompts for Problem Solving

by Tess Brigham

Mental Health

When you’re facing a problem, the first solution that comes to your mind might not involve journal prompts, but hear me out…

You’ve heard the phrase, “Life’s a journey, not a destination.” Or maybe you heard this version, “Life’s a journey, not a race.” And even better, “Life’s a journey, there is no one ahead of you or behind you. You are exactly where you need to be.”

These are the phrases we’ll say to our friends when they’re struggling but when it comes to our problems we don’t want to hear about life’s journey – we want to know exactly how to get there, and once we’re there, exactly what’s going to happen.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t work that way.

Journeys are not well-thought-out plans; they don’t go in straight lines and they certainly don’t have an itinerary. A journey is a process with the knowledge that your experiences will mostly dictate which direction you go in.

And in many ways, journeys and journaling go hand in hand (they even start with the same 5 letters…).

What is journaling?

Journaling is writing down your thoughts and feelings in order to understand yourself better. Journaling also allows you to process certain situations and experiences. When you journal you’re taking all those thoughts and feelings circling in your brain, making you feel anxious and overwhelmed, and you’re putting them on paper.

Once we put something down on paper it feels less scary and more manageable which allows you to tackle it not from a place of fear but from a place of awareness. The more you “expose” your thoughts and feelings, the less power they hold over you.

One of the more difficult aspects of being at a crossroads in your life is facing the unknown. You’re at a point in your life where your current life doesn’t fit but you have no idea what kind of life is the right fit for you. Journaling will help you get clear on what you want and don’t want, what thoughts you need to let go of, and clarify where you need to put your attention.

Why is journaling important

There have been a lot of studies about the benefits of journaling. A 2018 study found journaling for 12 weeks reduced the mental distress of people who struggle with anxiety. In another study, conducted in 2003 , 100 young adults were asked to journal for 15 minutes about a distressing event or simply about their day twice a week. The participants who journaled saw the biggest results, which included: a reduction of depression and anxiety symptoms as well as anger and frustration, especially if they were journaling about a specific event.

Journaling helps you better understand your thoughts and feelings. It expands your insights and allows you to take all of those thoughts and put them onto paper so you know why you’re thinking and feeling the way you do. It helps you improve your emotional intelligence, inspires creativity, boosts memory, enhances critical thinking and the list goes on.

For more information on How to Journal, check out my TikTok video .

Overcoming Writer’s Block While Journaling

In order to navigate through life, you have to start to see yourself as an explorer. You’re on your journey, seeking knowledge and new experiences. You have some idea of what’s out there but you know you want to see it for yourself.

By seeing yourself as an explorer, you can let go of the fear of failure because, when you explore, you allow yourself to be curious. When you’re curious, you don’t care if you’re “right” or “wrong,” you only care about what you learned from the experience.

As much as you may wish someone would come along and tell you exactly what’s going to happen if you travel down this road vs. that road, you know deep down inside that’ll never make you happy. If we all wanted to be told what to do, we’d still be living at home with our parents.

This is where journaling can really help you. Journaling allows you to explore the inside of your mind. Journaling allows you to go wherever you want to go, there are no limits. It pushes you to dig deep and write down the things that maybe you would never say to another person, but you need to admit to yourself.

Leveraging Journaling to Help You Problem Solve

If you want to learn how to coach yourself and solve your problems, be an explorer. Grab your “map” ( i.e. your journal) and start working on your path forward. Writing out your feelings might make you feel like you’re dragging your feet on this task, but remember research has shown journaling has helped people reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety, so by taking this step you’ll start to feel better.

Journaling allows you to organize your thoughts and feelings and it also allows you to get all of your unhelpful thoughts out of your head and onto paper. Our irrational thoughts are so scary in our minds but once you see them written on the page, those same thoughts lose power. The best part of journaling is that it forces you to put down your phone, get away from screens, and stop scrolling social media for the answers. Plus, once you turn down all of that unhelpful noise, you’ll be able to think more clearly about solutions.

Looking for a step-by step guide where I take your hand and walk you through how to make those big, scary decisions? Get started today with my online course – True You: Decision Designer. For more information on How to Better Trust Yourself once you’ve made a decision, check out my YouTube Video .

Ready to get started? Grab your pen and notebook and explore these two journal prompts:

Journal prompt no. 1: look to the past to help you navigate difficult situations.

When a situation like this has come up in the past, what’s worked for me and what hasn’t worked for me? Do I think those things will work for me now? Just like you learned in school, you have to understand your history or you may be doomed to repeat it. While past experiences don’t define you as a person, they are clues as to how previous life experiences affect how you see yourself and the world around you.

By asking yourself what’s worked and hasn’t worked in the past, you’re parsing out which thoughts, feelings, behaviors, and mindsets helped you move forward and which kept you stuck. You want to spot negative patterns of behavior because awareness is the first step towards change.

Now that you have a better sense of what’s worked as well as what hasn’t worked in the past, ask yourself if you think it’ll work for you today. You’re looking into the past to better understand the choices you once made, but you also have to take into account how you’ve changed since that time.

Don’t get into the habit of assuming you will always feel the same way about certain people, events, and situations. By looking into the past and then drawing your attention to today, you’re able to see how you’ve changed and evolved and that’s a good thing.

Journal Prompt No. 2: Look At The Present (And A Little Bit Into The Future)

Right now, what feels like the best choice for me at this moment? If I make this choice, then what do I think will happen in the future? Is that the future I want?

You’ve looked into the past and now have more awareness of your patterns of thinking and behavior, which means it’s time to look at the present day. There is so much pressure to make the “right” decisions all the time when in fact, we have no idea if a decision is “right” or “wrong” for us until after we’ve made the decision.

This is why it’s so important to ask yourself, based on how you feel today, what you want to do. You know what’s worked and hasn’t worked in the past. Now that you’re in the present, what do you think will work moving forward?

The hardest part of decision-making is sitting with the decision once we’ve made it. While you may feel tortured trying to make a decision, you still have all your options available to you which means there is no chance you can fail. The fear of failure is the biggest reason why so many people don’t make certain decisions, they fear they’ll make the “wrong” choice.

Remember you’re an explorer; there is no “right” or “wrong” direction. Allow yourself to think about what will happen if you travel east and if that’s what you’re looking for right now. Then think about what happens when you travel west and if that’s the future you’re seeking.

Writing your thoughts down allows you to experiment so you can sit with various visions to help you determine which way to go. It also allows you to examine your fears. Fears are, well, fears, they are always most powerful in the dark. Coaching yourself through journaling gives you the opportunity to bring those fears to light on the page.

Looking for more great journal prompts to help you navigate your life? Check out my TikTok video .

Ways to integrate journaling into your life

How to make it a habit:.

Your goal throughout your life is to better understand yourself and what you want for yourself. When you know yourself you’re able to make choices that align with your values. When you make choices that align with your values your life feels like your own and one you want to live.

All of this may feel daunting which is why it’s important to start small. For 10 minutes a day, preferably in the morning, you’re going to meditate for five (5) minutes and then journal for five (5) minutes. The best part: you don’t have to leave the house, it will cost you nothing and you’ll start to see the benefits pretty quickly.

I’ve already told you the benefits of journaling. Here’s why meditation is so powerful:

Meditation is the practice of focusing your mind either on your breath or a mantra while you notice, but not engage, with your thoughts. Research has shown meditation is incredibly powerful because it’s one of the best ways to manage depression and anxiety while also improving your mood and your emotional reactions.

What makes meditation so vital is you’re actively retraining your brain. While your brain is a static physical structure, it changes based on what you’re thinking and feeling. Our brains have the ability to improve and grow but it requires regular practice.

Most people believe in order to “meditate correctly” you must completely clear all of your thoughts. They give up when they find they can’t stop their thoughts during meditation and just assume meditation isn’t for them. Anyone can meditate and the goal isn’t to completely stop your thoughts, that’s impossible, but to simply notice your thoughts and then let them go.

For example, If you start thinking about what you’re going to have for dinner, instead of beating yourself up for having the thought, simply notice, “I’m thinking about dinner and I’m going to let that go and refocus on my breath or this mantra or the meditation I’m listening to.” You’re not stopping the thoughts, you’re noticing them without judgment and bringing your attention back to the present moment.

Doing this over and over again will help you be more present in the moment. This will help you stop ruminating about the past and stop worrying about the future. It will also help you become more aware of what you’re thinking and feeling which will inevitably help you learn more about yourself, and what you want and don’t want so you can start making decisions that feel right to you and only you.

Why meditation and journaling together?

While both meditation and journaling will help you better understand your thoughts and feelings, they work really well together. Meditation helps raise your awareness and teaches you that just because you have a thought it doesn’t make it true and it doesn’t mean you need to do something about it. Journaling can expand your insight and allow you to take all of those thoughts and put them onto paper so you can understand why you’re thinking and feeling the way you do.

How to do the 10-minute exercise:

Pick a time of day when you know you can accomplish this exercise without interruptions or distractions. This is why morning is always best. Block off this time in your calendar. The day before you start, pick a meditation you can do. You can find great meditations on Youtube or you can download an app like Headspace or Calm. Before you start, know what you’re going to use and have it ready. Also, make sure you put aside a notebook and a pen.

When it’s time to practice the exercise, set a timer for five (5) minutes (or pick a five (5) minute meditation). Immediately after your meditation take a breath and set your timer for another five (5) minutes and open up your notebook and start journaling. Don’t censor yourself, just write what comes into your mind. This simple act will start to awaken thoughts and feelings you didn’t know existed.

Once you start getting comfortable with this you can increase the meditation time to six (6) minutes and then seven (7) minutes. Meditation is a practice you can build up over time but you probably don’t want to keep journaling after five (5) minutes because your hand will start to hurt. Also once you get everything out of your head it may start to feel like a chore to keep writing.

How to use journaling to help you deal with family (especially during the holidays)

Whether you love your family, hate your family, or feel somewhere in between, spending time with your family will always bring up a lot of feelings.

While it’s easy to think, “I’ve been working on myself for this entire year. I’m building my confidence and creating a life I love. Nothing can get in my way.” Having a sense of how you want to show up, what your plan is if things go sideways and your personal boundaries is critical before family gatherings.

Whether you are best friends with your parents or you barely speak with your family, the holidays and other family gatherings force us to think about our relationships with our loved ones.

Each of us has a different set of wants and needs from our families. Some of you are recent college graduates who need your parents to treat you like an adult. Some of you have a parent you love very much but drinks waaaaaay too much. Some of you have a parent or sibling or another family member that has hurt you over and over again and the idea of “playing nice” for one more year makes your blood boil.

The biggest mistake I see my clients make is going into family gatherings with the mindset that they have no control over their family interactions. You can’t control what your parents do or say or how much your uncle may drink or how selfish your sister can be…but you can control how you respond and how you choose to react.

None of us had any say over the family we were born into and as children, we need to do what we need to do in order to survive. The best part of being an adult is you get to make choices on how you live your life. More importantly, you get to decide what you will or will not tolerate.

This means you can’t just show up and expect people to know how to treat you and then get upset when they can’t read your mind. You have to first figure out what you need and want from your family and from yourself.

How do you figure out what you’re going to do if your selfish sister gets under your skin again? Stop fuming and getting angry and start figuring out what you’re going to do differently. The best way to know how you feel about it and what you want to do about it is…you guessed it: journaling!

Journaling gets your internal thoughts – the ones spinning around in your head all day long making you feel confused and anxious – external. Once the internal becomes external, thoughts, feelings, and beliefs start to take shape, make more sense, and lose their power – in a good way.

Here are some of the questions to get you started:

Knowing that I can’t change my family, how do I want to feel at the end of each day I’m with them?

What’s one thing I can do differently when I’m around my family that will make this visit better than the last?

How will I take care of myself throughout my time with my family?

If someone triggers me and my anxiety or anger or resentment or ________ starts to come to the surface, what will I do?

What mindset do I need to walk in the door with in order to make sure this is a pleasant experience for everyone?

What expectations do I have already? Knowing I can only control myself and my actions, are these realistic?

Feel free to create your own questions. The primary goal is for you to identify what mindset you need to adopt in order to be with your family and remain the fantastic, wonderful, confident, and powerful person you are today.

How to use journaling to address your core beliefs

“Our beliefs are like unquestioned commands, telling us how things are, what’s possible and what’s impossible, what we can and can not do.” – Tony Robbins

Most of your core beliefs were formed when you were a child. This is because you were unable to understand and reason and didn’t have the life experience and perspective you have today. When you’re young you’re vulnerable and your parents have a tremendous amount of influence on how you perceive yourself and the people around you.

Now that you’re an adult you have the opportunity to look at those core beliefs and start to determine what YOU want to believe about yourself and the world around you.

Who you believe you are, is who you are.

We all struggle with a number of irrational beliefs about ourselves and the world. The most common ones are:

- If I don’t please people they may choose to reject me.

- I must always be completely competent and perfect in everything I do.

- I am not pretty enough, smart enough, rich enough…essentially I am not enough.

Here are some questions that I ask clients to help them begin to think about their own irrational beliefs.

- Take an inventory of all of your beliefs about yourself

- Which ones are left over from your childhood?

- What is the basis of your current beliefs about yourself? Why are you maintaining these beliefs?

- How does maintaining these beliefs serve you now?

How to use journaling as a part of your nighttime routine

It can be a vicious cycle. Work makes you anxious, and all day long, all you do is dream of getting home and getting into bed and relaxing. The workday is finally done, you log off, but you can’t relax. You crawl into bed, but you still can’t relax. You want to pull your hair out! “This is what I’ve been dreaming about all day; why can’t I sleep,” you scream to yourself.

It has been a stressful three years between the pandemic, shutdown, political climate, economy, and now mass lay-offs. It can feel overwhelming just getting up in the morning to go to work. If you’re having a hard time at work, you may feel like you don’t have a lot of control right now, but the one thing you have complete control over is your nighttime routine, and your nighttime routine can really affect the quality of your sleep. The better sleep you get, the better you’ll feel at work and the less anxiety you’ll feel.

One of the key symptoms of anxiety is having trouble sleeping. When we feel anxious, our body releases hormones that are very helpful in a dangerous situation, like adrenaline. But when you have chronic anxiety, and you’re on edge all the time about a toxic boss or looming deadlines, that same hormone isn’t so helpful. Those same hormones are making it hard for you to relax.

If you’re having trouble falling asleep or staying asleep, try this:

Five-Step Nighttime Routine

Step 1: Get the Junk Out

About 10-15 minutes before you’re ready to fall asleep, it’s time to let go of the junk from today and create something better for yourself tomorrow. Grab a notebook and a pen, set a timer for three minutes, and journal. Journaling is one of the easiest ways to get all of the negative thoughts and feelings out of your head.

It’s incredibly helpful to simply write out everything you’ve been thinking because it releases its power over you. Oftentimes, you’re able to see what’s bothering you isn’t as worrisome as it felt inside your head. You want to think about each night’s sleep, like cleaning up the kitchen. Each time you clean up, you’re throwing out things you no longer want or need because if you don’t, they will rot and start to smell. You want to do the same for your thoughts.

Step 2: Plan Your Day

Now that you’ve gotten rid of any thoughts and/or feelings that you need to let go of, it’s time to plan your day. You may be someone who does this as soon as they log off at work, and if you are, that’s great. If you’re not, this is a really helpful tool for anyone who struggles with organization because you want to have a game plan when you get to work in the morning.

This doesn’t mean that things aren’t going to come up that are going to throw you off, but what you want to do is think about what you need to do, what meetings you have, and make sure you schedule when you’re going to work on that proposal, when you’re going to respond to emails, and when you’re going to prepare for that presentation, so when you open your laptop, you know what you’re doing.

Anxiety is about control or the lack of control. The more you can focus on the things you can control at work, the less anxious you will feel, and when things do come up that you didn’t expect, it won’t impact you the same way.

Step 3: Wind it Down

Do you remember when you were a kid, and your parents put you to bed? They might have you take a bath, put you in pajamas, get you some warm milk, dim the lights, and read you a bedtime story. They were soothing you to sleep. When the story was over and if your eyes were still open, they might read another one, or they would sing you a song and rub your back until you fell into dreamland. Why do we think, now that we’re adults, we don’t still need that?

Here we are 30 years later with smartphones in our faces and laptops on our beds, listening to gruesome true crime stories, juggling five different group texts, and scrolling through Instagram and TikTok at 1 a.m. And we’re mad at ourselves because we’re struggling to fall asleep at night.

The key is to start creating your own wind-down time, not wine-down, wind-down time. Pick a time that you know you should be going to sleep to get enough rest and give yourself at least an hour, and that’s the time when you need to close the laptop, make a cup of decaf tea, or something else if you hate tea, dim the lights and put on what you’re going to wear to bed. Definitely no more work for the day, but if you have a favorite show, this would be the time to watch it. Put your phone down. No more social media or text threads; just focus on one thing at a time.

Step 4: Visualize Calm

After you’ve planned your day, take a few minutes, close your eyes, and visualize yourself waking up in the morning. See yourself waking up well-rested. You feel great, and you’re happy to start the day. See yourself get out of bed with energy and happiness. Whatever you planned for yourself the next day, visualize yourself going through that routine with grace, calm, and happiness – you at your best.

If you wake up in the morning and think, “Ugh, this day is going to suck!” Your day will suck. It will suck because you decided, before anything happened, it was going to suck. You determine your reality, so start visualizing yourself waking up and feeling amazing, in control, and calm; with no anxiety in sight.

Step 5: Let Go

Finally! It’s time to go to sleep. Turn off the lights and go to sleep. Or put on a podcast – no true crime, please. Or read a book until you’re sleepy. Even better, maybe listen to a relaxing meditation.

Sleep is critical not only to your success at work but to your mental health. Right now, it may feel like the world is out of control, so the best thing you can do for yourself is focus on what’s within your control: get a good night’s sleep.

Do you have anxiety? Here’s a night time routine you can adopt to help you wake up feeling calm and refreshed.

Having a crystal ball that predicts the future may seem like the solution to all of your problems but it isn’t. Yes, you’ll never fail in any way and you’ll have all the winning lottery numbers, but you need to travel down the wrong roads and make decisions that don’t work out as planned in order to learn and grow and discover what you do want for yourself. If life’s a journey, you’re an explorer and you have to do what great explorers do: seek and experience. The answers lie inside of you.

Happy writing!

Journal Prompt Worksheets

Books & Courses Available Now

Popular Posts

About tess brigham.