Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7 Strategy: Reading Actively by Annotating

Strategy: Reading Actively by Annotating

- Read to find the main ideas and support. Use your purpose to read actively.

- Find the answers to your questions.

- Find definitions for vocabulary.

- Make connections between the text and your experience, between parts of the text, and between the text and other lectures or text by annotating.

- Use headings and transition words to identify relationships in the text

An active reading strategy for articles or textbooks is annotation . Think for a moment about what that word means. It means to add notes (an-NOTE-tate) to text that you are reading, to offer explanation, comments or opinions to the author’s words. Annotation takes practice, and the better you are at it, the better you will be at reading complicated articles.

Where to Make Notes

First, determine how you will annotate the text you are about to read.

–If it is a printed article, you may be able to just write in the margins. A colored pen might make it easier to see than black or even blue.

–If it is an article posted on the web, you could also use Hypothesis, which is a highlighting and annotating tool that you can use on the website and even share your notes with your instructor. Other note-taking plug-ins for web browsers might serve a similar function. Hypothesis is enabled on this book in digital form.

–If it is a textbook that you do not own (or wish to sell back), use Post-it notes to annotate in the margins.

–You can also use a notebook to keep written commentary as you read in any platform, digital or print. If you do this, be sure to leave enough information about the specific text you’re responding to that you can find it later if you need to. (Make notes about page number, which paragraph it is, or even short quotes to help you locate the passage again.)

What Notes to Make

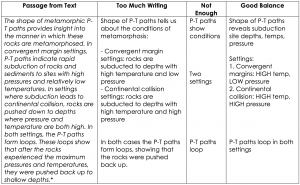

Scan the document you are annotating. Some obvious clues will be apparent before you read it, such as titles or headers for sections. Read the first paragraph. Somewhere in the first (or possibly the second) paragraph should be a BIG IDEA about what the article is going to be about. In the margins, near the top, write down the big idea of the article in your own words. This shouldn’t be more than a phrase or a sentence. This big idea is likely the article’s thesis.

Underline or highlight topic sentences or phrases that express the main idea for that paragraph or section. Write in the margin next to what you’ve underlined a summary of the paragraph or the idea being expressed.

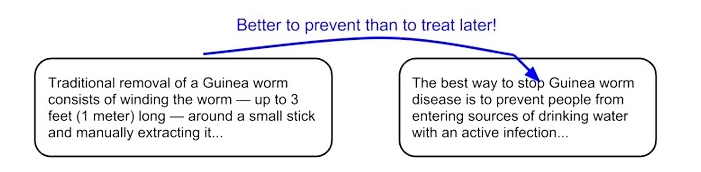

Connect related ideas by drawing arrows from one idea to another. Annotate those arrows with a phrase about how they are connected.

If you encounter an idea, word, or phrase you don’t understand, circle it and put a question mark in the margin that indicates an area of confusion . Write your question in the margin.

“Depending on the outcome of the assessment, the commission recommends to WHO which formerly endemic countries should be declared free of transmission, i.e., certified as free of the disease.” –> ?? What does this mean? Who is WHO?

Anytime the author makes a statement that you can connect with on a personal level, annotate in the margins a summary of how this connects to you. Write any comments or observations you feel appropriate to the text. You can also add your personal opinion.

“Guinea worm disease incapacitates victims for extended periods of time making them unable to work or grow enough food to feed their families or attend school.” –> My dad was sick for a while and couldn’t work. This was hard on our family.

Place a box around any term or phrase that emphasizes scientific language. These could be words you are not familiar with or will need to review later. Define those words in the margins.

“Guinea worm disease is set to become the second human disease in history, after smallpox, to be eradicated.” –> Eradicated = to put an end to, destroy

Like many skills, annotating takes practice! In the next chapter, you’ll be able to practice reading actively using the Aladdin article.

CC LICENSED CONTENT, ORIGINAL Revision and Adaptation. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SHARED PREVIOUSLY How to Annotate Text. Provided by : Biology Corner. Located at : https://biologycorner.com/worksheets/annotate.html . License : CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

Critical Literacy III Copyright © 2021 by Lori-Beth Larsen is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Writers' Center

Eastern Washington University

Reading and Study Strategies

What is annotating and why do it, annotation explained, steps to annotating a source, annotating strategies.

- Using a Dictionary

- Study Skills

[ Back to resource home ]

[email protected] 509.359.2779

Cheney Campus JFK Library Learning Commons

Stay Connected!

inside.ewu.edu/writerscenter Instagram Facebook

Helpful Links

Software for Annotating

ProQuest Flow (sign up with your EWU email)

FoxIt PDF Reader

Adobe Reader Pro - available on all campus computers

Track Changes in Microsoft Word

What is Annotating?

Annotating is any action that deliberately interacts with a text to enhance the reader's understanding of, recall of, and reaction to the text. Sometimes called "close reading," annotating usually involves highlighting or underlining key pieces of text and making notes in the margins of the text. This page will introduce you to several effective strategies for annotating a text that will help you get the most out of your reading.

Why Annotate?

By annotating a text, you will ensure that you understand what is happening in a text after you've read it. As you annotate, you should note the author's main points, shifts in the message or perspective of the text, key areas of focus, and your own thoughts as you read. However, annotating isn't just for people who feel challenged when reading academic texts. Even if you regularly understand and remember what you read, annotating will help you summarize a text, highlight important pieces of information, and ultimately prepare yourself for discussion and writing prompts that your instructor may give you. Annotating means you are doing the hard work while you read, allowing you to reference your previous work and have a clear jumping-off point for future work.

1. Survey : This is your first time through the reading

You can annotate by hand or by using document software. You can also annotate on post-its if you have a text you do not want to mark up. As you annotate, use these strategies to make the most of your efforts:

- Include a key or legend on your paper that indicates what each marking is for, and use a different marking for each type of information. Example: Underline for key points, highlight for vocabulary, and circle for transition points.

- If you use highlighters, consider using different colors for different types of reactions to the text. Example: Yellow for definitions, orange for questions, and blue for disagreement/confusion.

- Dedicate different tasks to each margin: Use one margin to make an outline of the text (thesis statement, description, definition #1, counter argument, etc.) and summarize main ideas, and use the other margin to note your thoughts, questions, and reactions to the text.

Lastly, as you annotate, make sure you are including descriptions of the text as well as your own reactions to the text. This will allow you to skim your notations at a later date to locate key information and quotations, and to recall your thought processes more easily and quickly.

- Next: Using a Dictionary >>

- Last Updated: Apr 25, 2024 2:50 PM

- URL: https://research.ewu.edu/writers_c_read_study_strategies

Reading Critically and Actively

Critical reading is a vital part of the writing process. In fact, reading and writing processes are alike. In both, you make meaning by actively engaging a text. As a reader, you are not a passive participant, but an active constructor of meaning. Exhibiting an inquisitive, "critical" attitude towards what you read will make anything you read richer and more useful to you in your classes and your life. This guide is designed to help you to understand and engage this active reading process more effectively so that you can become a better critical reader.

Reading a Text--Some Definitions

You might think that reading a text means curling up with a good book, or forcing yourself to study a textbook. Actually, reading a text can mean much more. First of all, let's define the two terms of interest here--"reading" and "text."

What Counts as Reading?

Reading is something we do with books and other print materials, certainly, but we also read things like the sky when we want to know what the weather is doing, someone's expression or body language when we want to know what someone is thinking or feeling, or an unpredictable situation so we'll know what the best course of action is. As well as reading to gather information, "reading" can mean such diverse things as interpreting, analyzing, or attempting to make predictions.

What Counts as a Text?

When we think of a text, we may think of words in print, but a text can be anything from a road map to a movie. Some have expanded the meaning of "text" to include anything that can be read, interpreted or analyzed. So a painting can be a text to interpret for some meaning it holds, and a mall can be a text to be analyzed to find out how modern Americans behave in their free time.

How Do Readers Read?

Those who study the way readers read have come up with some different theories about how readers make meaning from the texts they read.

Being aware of how readers read is important so that you can become a more critical reader. In fact, you may discover that you are already a critical reader.

The Reading Equation

Prior Knowledge + Predictions = Comprehension

When we read, we don't decipher every word on the page for its individual meaning. We process text in chunks, and we also employ other "tricks" to help us make meaning out of so many individual words in a text we are reading. First, we bring prior knowledge to everything we read, whether we are aware of it or not. Titles of texts, authors' names, and the topic of the piece all trigger prior knowledge in us. The more prior knowledge we have, the better prepared we are to make meaning of the text. With prior knowledge we make predictions, or guesses about how what we are reading relates to our prior experience. We also make predictions about what meaning the text will convey.

Related Information: How can Reaching Comprehension Make Us Better Writers?

When you have successfully comprehended the text you are reading, you should take this comprehension one step further and try to apply it to your writing process. Good writers know that readers have to work to make meaning of texts, so they will try to make the reader's journey through the text as effortless as possible. As a writer you can help readers tap into prior knowledge by clearly outlining your intent in the introduction of your paper and making use of your own personal experience. You can help readers make accurate guesses by employing clear organization and using clear transitions in your paper.

Related Information: Making Predictions

Whether you realize it or not, you are always making guesses about what you will encounter next in a text. Making predictions about where a text is headed is an important part of the comprehension equation. It's alright to make wrong guesses about what a text will do--wrong guesses are just as much a part of the meaning-making process of reading as right guesses are.

Related Information: Tapping into Prior Knowledge

It's important to tap into your prior knowledge of subject before you read about it. Writing an entry in your writer's notebook may be a good way to access this prior knowledge. Discussing the subject with classmates before you read is also a good idea. Tapping into prior knowledge will allow you to approach a piece of writing with more ways to create comprehension than if you start reading "cold."

Cognitive Reading Theory

When you read, you may think you are decoding a message that a writer has encoded into a text. Error in reading comprehension, in this model, would occur if you as a reader were not decoding the message correctly, or if the writer was not encoding the message accurately or clearly. The writer, however, would have the responsibility of getting the message into the text, and the reader would assume a passive role.

Related Information: Reading has a Model

Let's look at a more recent and widely accepted model of reading that is based on cognitive psychology and schema theory. In this model, the reader is an active participant who has an important interpretive function in the reading process. In other words, in the cognitive model you as a reader are more than a passive participant who receives information while an active text makes itself and its meanings known to you. Actually, the act of reading is a push and pull between reader and text. As a reader, you actively make, or construct, meaning; what you bring to the text is at least as important as the text itself.

Related Information: Reading is an active, constuctive, meaning-making process

Readers construct a meaning they can create from a text, so that "what a text means" can differ from reader to reader. Readers construct meaning based not only on the visual cues in the text (the words and format of the page itself) but also based on non-visual information such as all the knowledge readers already have in their heads about the world, their experience with reading as an activity, and, especially, what they know about reading different kinds of writing. This kind of non-visual information that readers bring with them before they even encounter the text is far more potent than the actual words on the page.

Related Information: Reading is hypothesis based

In yet another layer of complexity, readers also create for themselves an idea of what the text is about before they read it. In reading, prediction is much more important than decoding. In fact, if we had to read each letter and word, we couldn't possibly remember the letters and words long enough to put them all together to make sense of a sentence. And reading larger chunks than sentences would be absolutely impossible with our limited short-term memories.

So, instead of looking at each word and figuring out what it "means," readers rely on all their language and discourse knowledge to predict what a text is about. Then we sample the text to confirm, revise, or discard that hypothesis. More highly structured texts with topic sentences and lots of forecasting features are easier to hypothesize about; they're also easier to learn information from. Less structured texts that allow lots of room for predictions (and revised and discarded hypotheses) give more room for creative meanings constructed by readers. Thus we get office memos or textbooks or entertaining novels.

Related Information: Reading is multi-level

When we read a text, we pick up visual cues based on font size and clarity, the presence or absence of "pictures," spelling, syntax, discourse cues, and topic. In other words, we integrate data from a text including its smallest and most discrete features as well as its largest, most abstract features. Usually, we don't even know we're integrating data from all these levels. In addition, data from the text is being integrated with what we already know from our experience in the world about all fonts, pictures, spelling, syntax, discourse, and the topic more generally. No wonder reading is so complex!

Related Information: Reading is Strategic

We change our reading strategies (processes) depending on why we're reading. If we are reading an instruction manual, we usually read one step at a time and then try to do whatever the instructions tell us. If we are reading a novel, we don't tend to read for informative details. If we a reading a biology textbook, we read for understanding both of concepts and details (particularly if we expected to be tested over our comprehension of the material.)

Our goals for reading will affect the way we read a text. Not only do we read for the intended message, but we also construct a meaning that is valuable in terms of our purpose for reading the text.

Strategic reading also allows us to speed up or slow down, depending on our goals for reading (e.g. scanning newspaper headlines v. Carefully perusing a feature story).

Strategies for Reading More Critically

Although you probably already read critically in some respects, here are some things you can do when you read a text to improve your critical reading skills.

Most successful critical readers do some combination of the following strategies:

Summarizing

Previewing a text means gathering as much information about the text as you can before you actually read it. You can ask yourself the following questions:

What is my Purpose for Reading?

If you are being asked to summarize a particular piece of writing, you will want to look for the thesis and main points. Are you being asked to respond to a piece? If so, you may want to be conscious of what you already know about the topic and how you arrived at that opinion.

What can the Title Tell Me About the Text?

Before you read, look at the title of the text. What clues does it give you about the piece of writing? It may reveal the author's stance, or make a claim the piece will try to support. Good writers usually try to make their titles do work to help readers make meaning of the text from the reader's first glance at it.

Who is the Author?

If you have heard the author's name before, what comes to your mind in terms of their reputation and/or stance on the issue you are reading about? Has the author written other things of which you are aware? How does the piece in front of you fit into to the author's body of work? What is the author's political position on the issue they are writing about? Are they liberal, conservative, or do you know anything about what prompted them to write in the first place?

How is the Text Structured?

Sometimes the structure of a piece can give you important clues to its meaning. Be sure to read all section headings carefully. Also, reading the opening sentences of paragraphs should give you a good idea of the main ideas contained in the piece.

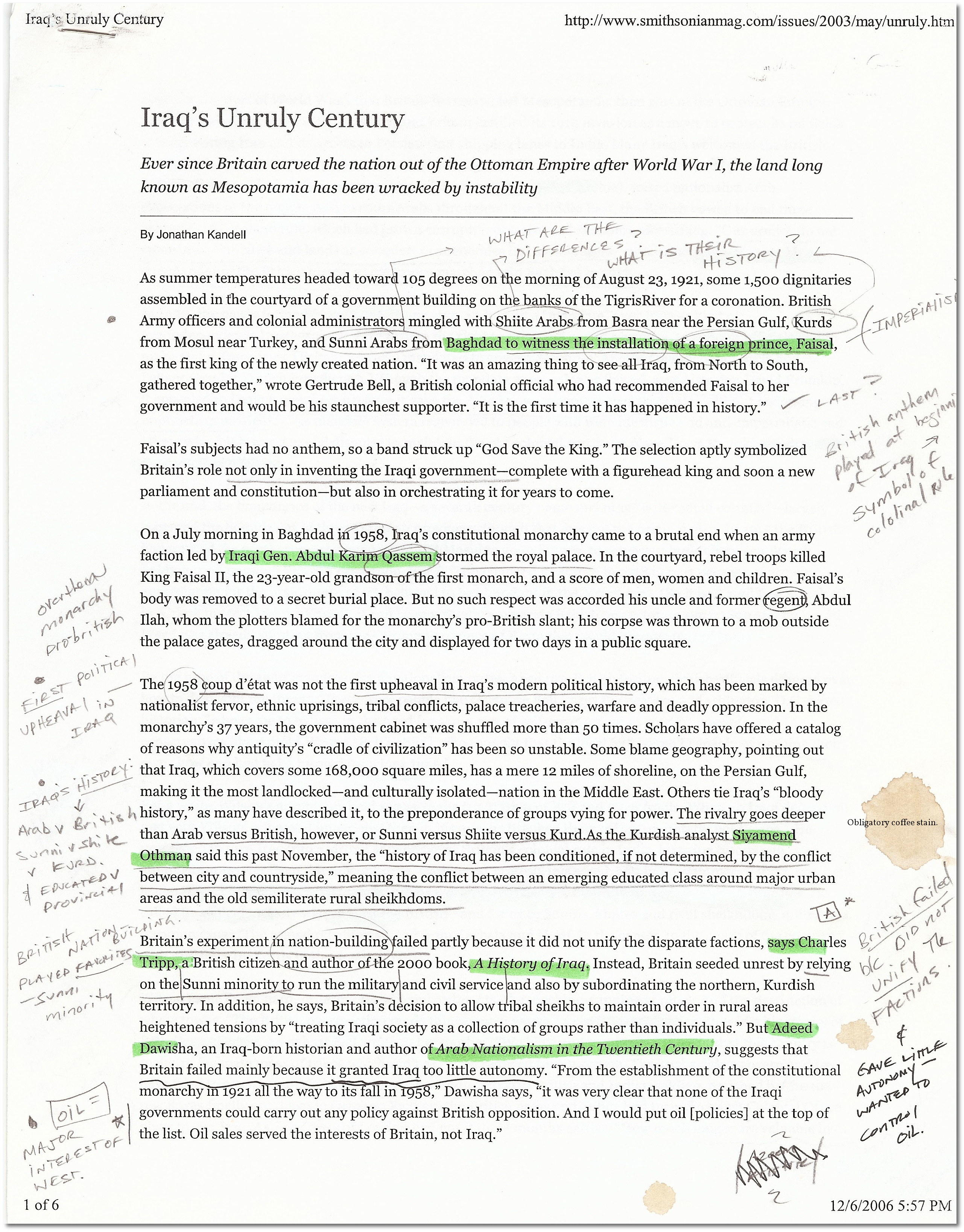

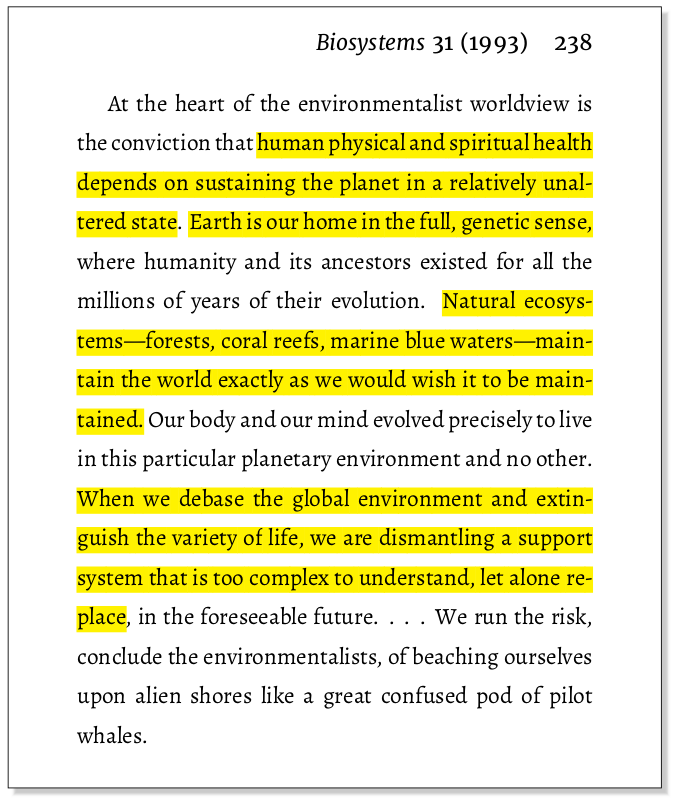

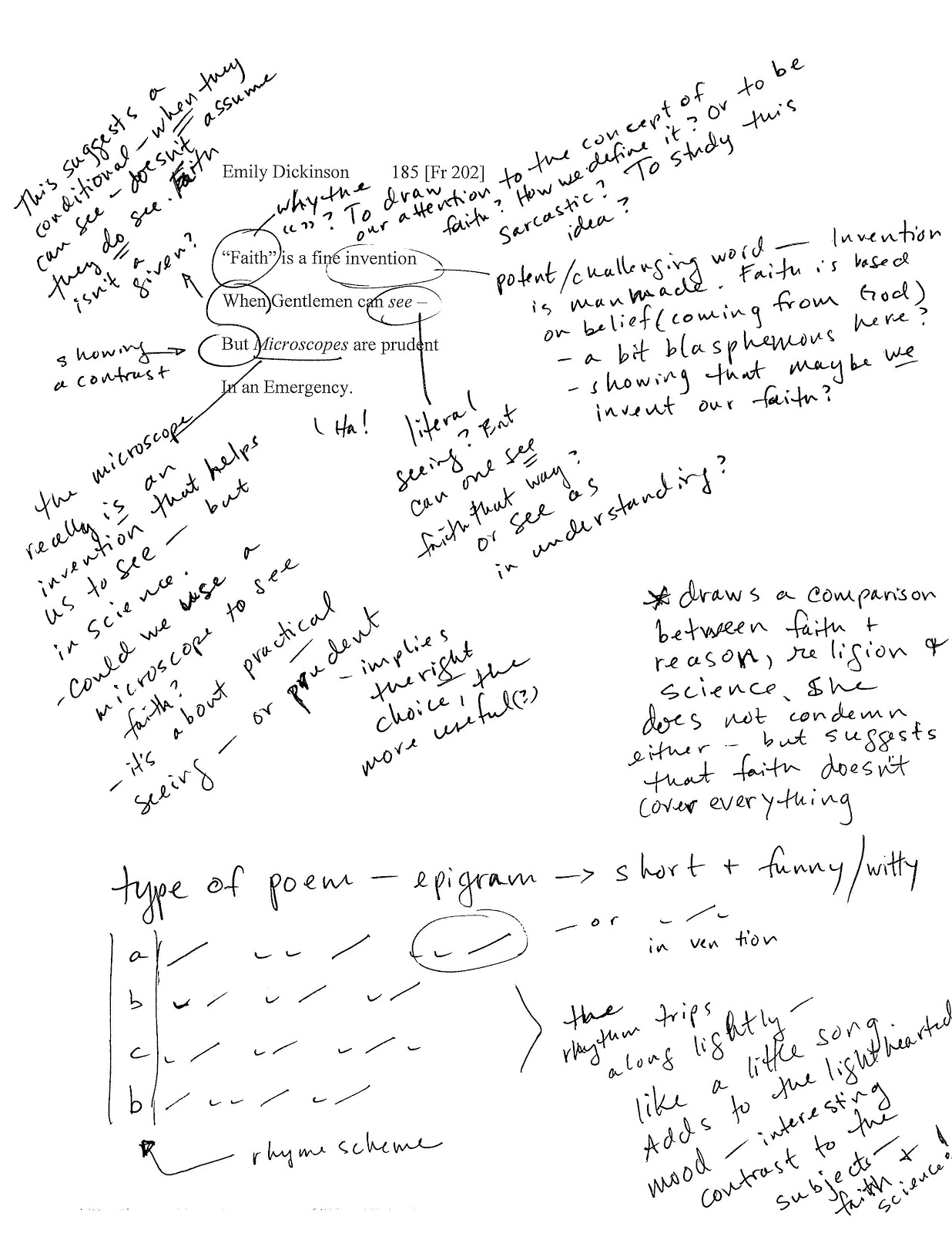

Annotating is an important skill to employ if you want to read critically. Successful critical readers read with a pencil in their hand, making notes in the text as they read. Instead of reading passively, they create an active relationship with what they are reading by "talking back" to the text in its margins. You may want to make the following annotations as you read:

Mark the Thesis and Main Points of the Piece

Mark key terms and unfamiliar words, underline important ideas and memorable images, write your questions and/or comments in the margins of the piece, write any personal experience related to the piece, mark confusing parts of the piece, or sections that warrant a reread, underline the sources, if any, the author has used.

Mark the thesis and main points of the piece. The thesis is the main idea or claim of the text, and relates to the author's purpose for writing. Sometimes the thesis is not explicitly stated, but is implied in the text, but you should still be able to paraphrase an overall idea the author is interested in exploring in the text. The thesis can be thought of as a promise the writer makes to the reader that the rest of the essay attempts to fulfill.

The main points are the major subtopics, or sub-ideas the author wants to explore. Main points make up the body of the text, and are often signaled by major divisions in the structure of the text.

Marking the thesis and main points will help you understand the overall idea of the text, and the way the author has chosen to develop her or his thesis through the main points s/he has chosen.

While you are annotating the text you are reading, be sure to circle unfamiliar words and take the time to look them up in the dictionary. Making meaning of some discussions in texts depends on your understanding of pivotal words. You should also annotate key terms that keep popping up in your reading. The fact that the author uses key terms to signal important and/or recurring ideas means that you should have a firm grasp of what they mean.

You will want to underline important ideas and memorable images so that you can go back to the piece and find them easily. Marking these things will also help you relate to the author's position in the piece more readily. Writers may try to signal important ideas with the use of descriptive language or images, and where you find these stylistic devices, there may be a key concept the writer is trying to convey.

Writing your own questions and responses to the text in its margins may be the most important aspect of annotating. "Talking back" to the text is an important meaning-making activity for critical readers. Think about what thoughts and feelings the text arouses in you. Do you agree or disagree with what the author is saying? Are you confused by a certain section of the text? Write your reactions to the reading in the margins of the text itself so you can refer to it again easily. This will not only make your reading more active and memorable, but it may be material you can use in your own writing later on.

One way to make a meaningful connection to a text is to connect the ideas in the text to your own personal experience. Where can you identify with what the author is saying? Where do you differ in terms of personal experience? Identifying personally with the piece will enable you to get more out of your reading because it will become more relevant to your life, and you will be able to remember what you read more easily.

Be sure to mark confusing parts of the piece you are reading, or sections that warrant a reread. It is tempting to glide over confusing parts of a text, probably because they cause frustration in us as readers. But it is important to go back to confusing sections to try to understand as much as you can about them. Annotating these sections may also remind you to bring up the confusing section in class or to your instructor.

Good critical readers are always aware of the sources an author uses in her or his text. You should mark sources in the text and ask yourself the following questions:

- Is the source relevant? In other words, does the source work to support what the author is trying to say?

- Is the source credible? What is his or her reputation? Is the source authoritative? What is the source's bias on the issue? What is the source's political and/or personal stance on the issue?

- Is the source current? Is there new information that refutes what the source is asserting? Is the writer of the text using source material that is outdated?

Summarizing the text you've read is an valuable way to check your understanding of the text. When you summarize, you should be able to find and write down the thesis and main points of the text.

Annotating the thesis and main points

Analyzing a text means breaking it down into its parts to find out how these parts relate to one another. Being aware of the functions of various parts of a piece of writing and their relationship to one another and the overall piece can help you better understand a text's meaning. To analyze a text, you can look at the following things:

- Assumptions

- Author Bias

Analyzing Evidence

Consider the evidence the author presents. Is there enough evidence to support the point the author is trying to make? Does the evidence relate to the main point in a logical way? In other words, does the evidence work to prove the point, or does is contradict the point, or show itself to be irrelevant to the point the author is trying to make?

Related Information: Source Evaluation

Analyzing Assumptions

Consider any assumptions the author is making. Assumptions may be unstated in the piece of writing you are assessing, but the writer may be basing her or his thesis on them. What does the author have to believe is true before the rest of her or his essay makes sense?

Example: "[I]f a college recruiter argues that the school is superior to most others because its ratio of students to teachers is low, the unstated assumptions are (1) that students there will get more attention, and (2) that more attention results in a better education" (Crusius and Channell, The Aims of Argument , Mayfield Publishing Co., 1995).

Analyzing Sources

If an author uses outside sources to back up what s/he is saying, analyzing those sources is an important critical reading activity. Not all sources are created equal. There are at least three criteria to keep in mind when you are evaluating a source:

- Is the Source Relevant?

- Is the Source Credible?

- Is the Source Current?

Analyzing Author Bias

Taking a close look at the author's bias can tell you a lot about a text. Ask yourself what experiences in the author's background may have led him or her to hold the position s/he does. What does s/he hope to gain from taking this position? How does the author's position stand up in comparison to other positions on the issue? Knowing where the author is "coming from" can help you to more easily make meaning from a text.

Re-reading is a crucial part of the critical reading process. Good readers will reread a piece several times, until they are satisfied they know it inside and out. It is recommended that you read a text three times to make as much meaning as you can.

The First Reading

The first time you read a text, skim it quickly for its main ideas. Pay attention to the introduction, the opening sentences of paragraphs, and section headings, if there are any. Previewing the text in this way gets you off to a good start when you have to read critically.

The Second Reading

The second reading should be a slow, meditative read, and you should have your pencil in your hand so you can annotate the text. Taking time to annotate your text during the second reading may be the most important strategy to master if you want to become a critical reader.

The Third Reading

The third reading should take into account any questions you asked yourself by annotating the margins. You should use this reading to look up any unfamiliar words, and to make sure you have understood any confusing or complicated sections of the text.

Responding to what you read is an important step in understanding what you read. You can respond in writing, or by talking about what you've read to others. Here are several ways you can respond critically to a piece of writing:

- Writing a Response in Your Writer's Notebook

- Discussing the Text with Others

Writing a response in your writer's notebook

One way to make sure you have understood a piece of writing is to write a response to it. It may be beneficial to first write a summary of the text, covering the thesis and main points in an unbiased way. Pretend you are reporting on the "facts" of the piece to a friend who has not read it, the point being to keep your own opinion out of the summary. Once you have summarized the author's ideas objectively, you can respond to them in your writer's notebook. You can agree or disagree with the text, interpret it, or analyze it. Working with your reading of the text by responding in writing is a good way to read critically.

Keeping a writer's notebook

A writer's notebook, or journal, is a place in which you can respond to your reading. You should feel free to say what you really think about the piece you are reading, to ask questions, and to express frustration or confusion about the piece. The writer's notebook is a place you can come back to when it is time to write an assignment, to look for your initial reactions to your readings, or to pull support for an essay from personal experience you may have recorded. Writing about what you are reading is a way to become actively engaged in the critical reading process.

Discussing the text with others

Cooperative activities are important to critical reading just as they are to the writing process. Sharing your knowledge of a text with others reading the same text is a good way to check your understanding and open up new avenues of comprehension. You can annotate a text on your own first, and then confer with a group of classmates about how they annotated their texts. Or, you can be sure to participate in class discussion of a shared text--verbalizing your ideas about a text will reinforce your reading process.

Critically Reading Assignment Sheets

It is important to have read your assignment sheet critically before you begin to write. Consider the following things:

Analyze your Assignment Sheet Carefully

Pay attention to the length of the essay, and other requirements, plan your time well.

You may want to annotate your assignment sheet like you would any other piece of writing. Look for key terms like analyze, interpret, argue, summarize, compare, contrast, explain, etc. These terms will tell you your purpose for writing. Be sure to know how your instructor is using key words on the assignment sheet. If you don't understand something about the assignment, be sure to ask your instructor. It's vital to understand the assignment completely before you begin writing.

Be sure to have a firm grasp on what you must do to meet the requirements of the assignment. Know how long the essay must be, because this will affect the thesis and focus of the paper. Short papers dictate a narrow focus, whereas longer paper allow for a larger focus.

Know also what formatting requirements are in place, such as font size, margins and other constraints.

Know when the assignment due date is and be sure to allow enough time for all thinking, reading, researching , drafting and revising. Be aware of your instructor's policy on due dates. Most instructors do not accept late papers.

Reading for Meaning

After you've read an essay once, use the following set of questions to guide your re-readings of the text. The question on the left-hand side will help you describe and analyze the text; the question on the right hand side will help focus your response(s).

Remember that not all these questions will be relevant to any given essay or text, but one or two of them may suggest a direction or give a focus to your overall response.

When one of these questions suggests a focus for your response to the essay, go back to the text to gather evidence to support your response.

Walker, Debra, Kate Kiefer, & Stephen Reid. (1995). Critical Reading. Writing@CSU . Colorado State University. https://writing.colostate.edu/guides/guide,cfm?guideid=31

How to Annotate Texts

Use the links below to jump directly to any section of this guide:

Annotation Fundamentals

How to start annotating , how to annotate digital texts, how to annotate a textbook, how to annotate a scholarly article or book, how to annotate literature, how to annotate images, videos, and performances, additional resources for teachers.

Writing in your books can make you smarter. Or, at least (according to education experts), annotation–an umbrella term for underlining, highlighting, circling, and, most importantly, leaving comments in the margins–helps students to remember and comprehend what they read. Annotation is like a conversation between reader and text. Proper annotation allows students to record their own opinions and reactions, which can serve as the inspiration for research questions and theses. So, whether you're reading a novel, poem, news article, or science textbook, taking notes along the way can give you an advantage in preparing for tests or writing essays. This guide contains resources that explain the benefits of annotating texts, provide annotation tools, and suggest approaches for diverse kinds of texts; the last section includes lesson plans and exercises for teachers.

Why annotate? As the resources below explain, annotation allows students to emphasize connections to material covered elsewhere in the text (or in other texts), material covered previously in the course, or material covered in lectures and discussion. In other words, proper annotation is an organizing tool and a time saver. The links in this section will introduce you to the theory, practice, and purpose of annotation.

How to Mark a Book, by Mortimer Adler

This famous, charming essay lays out the case for marking up books, and provides practical suggestions at the end including underlining, highlighting, circling key words, using vertical lines to mark shifts in tone/subject, numbering points in an argument, and keeping track of questions that occur to you as you read.

How Annotation Reshapes Student Thinking (TeacherHUB)

In this article, a high school teacher discusses the importance of annotation and how annotation encourages more effective critical thinking.

The Future of Annotation (Journal of Business and Technical Communication)

This scholarly article summarizes research on the benefits of annotation in the classroom and in business. It also discusses how technology and digital texts might affect the future of annotation.

Annotating to Deepen Understanding (Texas Education Agency)

This website provides another introduction to annotation (designed for 11th graders). It includes a helpful section that teaches students how to annotate reading comprehension passages on tests.

Once you understand what annotation is, you're ready to begin. But what tools do you need? How do you prepare? The resources linked in this section list strategies and techniques you can use to start annotating.

What is Annotating? (Charleston County School District)

This resource gives an overview of annotation styles, including useful shorthands and symbols. This is a good place for a student who has never annotated before to begin.

How to Annotate Text While Reading (YouTube)

This video tutorial (appropriate for grades 6–10) explains the basic ins and outs of annotation and gives examples of the type of information students should be looking for.

Annotation Practices: Reading a Play-text vs. Watching Film (U Calgary)

This blog post, written by a student, talks about how the goals and approaches of annotation might change depending on the type of text or performance being observed.

Annotating Texts with Sticky Notes (Lyndhurst Schools)

Sometimes students are asked to annotate books they don't own or can't write in for other reasons. This resource provides some strategies for using sticky notes instead.

Teaching Students to Close Read...When You Can't Mark the Text (Performing in Education)

Here, a sixth grade teacher demonstrates the strategies she uses for getting her students to annotate with sticky notes. This resource includes a link to the teacher's free Annotation Bookmark (via Teachers Pay Teachers).

Digital texts can present a special challenge when it comes to annotation; emerging research suggests that many students struggle to critically read and retain information from digital texts. However, proper annotation can solve the problem. This section contains links to the most highly-utilized platforms for electronic annotation.

Evernote is one of the two big players in the "digital annotation apps" game. In addition to allowing users to annotate digital documents, the service (for a fee) allows users to group multiple formats (PDF, webpages, scanned hand-written notes) into separate notebooks, create voice recordings, and sync across all sorts of devices.

OneNote is Evernote's main competitor. Reviews suggest that OneNote allows for more freedom for digital note-taking than Evernote, but that it is slightly more awkward to import and annotate a PDF, especially on certain platforms. However, OneNote's free version is slightly more feature-filled, and OneNote allows you to link your notes to time stamps on an audio recording.

Diigo is a basic browser extension that allows a user to annotate webpages. Diigo also offers a Screenshot app that allows for direct saving to Google Drive.

While the creators of Hypothesis like to focus on their app's social dimension, students are more likely to be interested in the private highlighting and annotating functions of this program.

Foxit PDF Reader

Foxit is one of the leading PDF readers. Though the full suite must be purchased, Foxit offers a number of annotation and highlighting tools for free.

Nitro PDF Reader

This is another well-reviewed, free PDF reader that includes annotation and highlighting. Annotation, text editing, and other tools are included in the free version.

Goodreader is a very popular Mac-only app that includes annotation and editing tools for PDFs, Word documents, Powerpoint, and other formats.

Although textbooks have vocabulary lists, summaries, and other features to emphasize important material, annotation can allow students to process information and discover their own connections. This section links to guides and video tutorials that introduce you to textbook annotation.

Annotating Textbooks (Niagara University)

This PDF provides a basic introduction as well as strategies including focusing on main ideas, working by section or chapter, annotating in your own words, and turning section headings into questions.

A Simple Guide to Text Annotation (Catawba College)

The simple, practical strategies laid out in this step-by-step guide will help students learn how to break down chapters in their textbooks using main ideas, definitions, lists, summaries, and potential test questions.

Annotating (Mercer Community College)

This packet, an excerpt from a literature textbook, provides a short exercise and some examples of how to do textbook annotation, including using shorthand and symbols.

Reading Your Healthcare Textbook: Annotation (Saddleback College)

This powerpoint contains a number of helpful suggestions, especially for students who are new to annotation. It emphasizes limited highlighting, lots of student writing, and using key words to find the most important information in a textbook. Despite the title, it is useful to a student in any discipline.

Annotating a Textbook (Excelsior College OWL)

This video (with included transcript) discusses how to use textbook features like boxes and sidebars to help guide annotation. It's an extremely helpful, detailed discussion of how textbooks are organized.

Because scholarly articles and books have complex arguments and often depend on technical vocabulary, they present particular challenges for an annotating student. The resources in this section help students get to the heart of scholarly texts in order to annotate and, by extension, understand the reading.

Annotating a Text (Hunter College)

This resource is designed for college students and shows how to annotate a scholarly article using highlighting, paraphrase, a descriptive outline, and a two-margin approach. It ends with a sample passage marked up using the strategies provided.

Guide to Annotating the Scholarly Article (ReadWriteThink.org)

This is an effective introduction to annotating scholarly articles across all disciplines. This resource encourages students to break down how the article uses primary and secondary sources and to annotate the types of arguments and persuasive strategies (synthesis, analysis, compare/contrast).

How to Highlight and Annotate Your Research Articles (CHHS Media Center)

This video, developed by a high school media specialist, provides an effective beginner-level introduction to annotating research articles.

How to Read a Scholarly Book (AndrewJacobs.org)

In this essay, a college professor lets readers in on the secrets of scholarly monographs. Though he does not discuss annotation, he explains how to find a scholarly book's thesis, methodology, and often even a brief literature review in the introduction. This is a key place for students to focus when creating annotations.

A 5-step Approach to Reading Scholarly Literature and Taking Notes (Heather Young Leslie)

This resource, written by a professor of anthropology, is an even more comprehensive and detailed guide to reading scholarly literature. Combining the annotation techniques above with the reading strategy here allows students to process scholarly book efficiently.

Annotation is also an important part of close reading works of literature. Annotating helps students recognize symbolism, double meanings, and other literary devices. These resources provide additional guidelines on annotating literature.

AP English Language Annotation Guide (YouTube)

In this ~10 minute video, an AP Language teacher provides tips and suggestions for using annotations to point out rhetorical strategies and other important information.

Annotating Text Lesson (YouTube)

In this video tutorial, an English teacher shows how she uses the white board to guide students through annotation and close reading. This resource uses an in-depth example to model annotation step-by-step.

Close Reading a Text and Avoiding Pitfalls (Purdue OWL)

This resources demonstrates how annotation is a central part of a solid close reading strategy; it also lists common mistakes to avoid in the annotation process.

AP Literature Assignment: Annotating Literature (Mount Notre Dame H.S.)

This brief assignment sheet contains suggestions for what to annotate in a novel, including building connections between parts of the book, among multiple books you are reading/have read, and between the book and your own experience. It also includes samples of quality annotations.

AP Handout: Annotation Guide (Covington Catholic H.S.)

This annotation guide shows how to keep track of symbolism, figurative language, and other devices in a novel using a highlighter, a pencil, and every part of a book (including the front and back covers).

In addition to written resources, it's possible to annotate visual "texts" like theatrical performances, movies, sculptures, and paintings. Taking notes on visual texts allows students to recall details after viewing a resource which, unlike a book, can't be re-read or re-visited ( for example, a play that has finished its run, or an art exhibition that is far away). These resources draw attention to the special questions and techniques that students should use when dealing with visual texts.

How to Take Notes on Videos (U of Southern California)

This resource is a good place to start for a student who has never had to take notes on film before. It briefly outlines three general approaches to note-taking on a film.

How to Analyze a Movie, Step-by-Step (San Diego Film Festival)

This detailed guide provides lots of tips for film criticism and analysis. It contains a list of specific questions to ask with respect to plot, character development, direction, musical score, cinematography, special effects, and more.

How to "Read" a Film (UPenn)

This resource provides an academic perspective on the art of annotating and analyzing a film. Like other resources, it provides students a checklist of things to watch out for as they watch the film.

Art Annotation Guide (Gosford Hill School)

This resource focuses on how to annotate a piece of art with respect to its formal elements like line, tone, mood, and composition. It contains a number of helpful questions and relevant examples.

Photography Annotation (Arts at Trinity)

This resource is designed specifically for photography students. Like some of the other resources on this list, it primarily focuses on formal elements, but also shows students how to integrate the specific technical vocabulary of modern photography. This resource also contains a number of helpful sample annotations.

How to Review a Play (U of Wisconsin)

This resource from the University of Wisconsin Writing Center is designed to help students write a review of a play. It contains suggested questions for students to keep in mind as they watch a given production. This resource helps students think about staging, props, script alterations, and many other key elements of a performance.

This section contains links to lessons plans and exercises suitable for high school and college instructors.

Beyond the Yellow Highlighter: Teaching Annotation Skills to Improve Reading Comprehension (English Journal)

In this journal article, a high school teacher talks about her approach to teaching annotation. This article makes a clear distinction between annotation and mere highlighting.

Lesson Plan for Teaching Annotation, Grades 9–12 (readwritethink.org)

This lesson plan, published by the National Council of Teachers of English, contains four complete lessons that help introduce high school students to annotation.

Teaching Theme Using Close Reading (Performing in Education)

This lesson plan was developed by a middle school teacher, and is aligned to Common Core. The teacher presents her strategies and resources in comprehensive fashion.

Analyzing a Speech Using Annotation (UNC-TV/PBS Learning Media)

This complete lesson plan, which includes a guide for the teacher and relevant handouts for students, will prepare students to analyze both the written and presentation components of a speech. This lesson plan is best for students in 6th–10th grade.

Writing to Learn History: Annotation and Mini-Writes (teachinghistory.org)

This teaching guide, developed for high school History classes, provides handouts and suggested exercises that can help students become more comfortable with annotating historical sources.

Writing About Art (The College Board)

This Prezi presentation is useful to any teacher introducing students to the basics of annotating art. The presentation covers annotating for both formal elements and historical/cultural significance.

Film Study Worksheets (TeachWithMovies.org)

This resource contains links to a general film study worksheet, as well as specific worksheets for novel adaptations, historical films, documentaries, and more. These resources are appropriate for advanced middle school students and some high school students.

Annotation Practice Worksheet (La Guardia Community College)

This worksheet has a sample text and instructions for students to annotate it. It is a useful resource for teachers who want to give their students a chance to practice, but don't have the time to select an appropriate piece of text.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1941 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 40,925 quotes across 1941 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

Need something? Request a new guide .

How can we improve? Share feedback .

LitCharts is hiring!

The REAP Method of Note-Taking: Improving Critical Reading

In this article, we'll explore how to apply the REAP (Read, Encode, Annotate, Ponder) method of reading to engage with texts in order to strengthen your comprehension and critical reflection.

- By Markus Forsberg

- Jan 25, 2023

E-student.org is supported by our community of learners. When you visit links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission.

- The REAP method encourages active reading and critical thinking by breaking the process of reading a text into four distinct stages.

- The four stages (Read, Encode, Annotate, and Ponder) can be applied to any type of reading material to ensure you are engaging with the material in a meaningful way

- The method has been well studied, with strong scientific results supporting its efficacy.

Do you often feel that you study texts just to forget what they said almost as soon as you finished reading them? The REAP (Read, Encode, Annotate, Ponder) method is a powerful technique for taking effective and organized notes while reading. By encouraging active reading and breaking down the reading and reflection process into four distinct stages, it provides you with a straightforward way to ensure you are engaging with the material in a meaningful way.

In this article, we’ll be looking at what the REAP method is and how we can apply it in our studies, as well as what the scientific literature has to say about its effectiveness.

Table of Contents

What is the reap method.

The REAP method was developed by Marilyn Eanet and Anthony Manzo at the University of Missouri at Kansas City in 1976 as a response to what they saw as inadequate teaching methods for developing active reading. The method is designed to help students be able to understand the meaning of texts through reflecting and communicating on their content.

REAP consists of four stages:

- Reading: Reading the text provided to identify the ideas expressed by the author.

- Encoding: “Encoding” the main ideas identified in the text in your own words.

- Annotating: Writing “annotations” of the ideas, quotes, etc., in the text.

- Pondering: Reflecting on the content and writing comments or criticisms of the text, and discussing with others.

This will make you return to a text multiple times, each time from a different vantage point, and let you gradually analyze the text at a higher and higher level.

Note that there is some confusion about what the acronym REAP signifies. This is largely due to a competing approach for note-taking, also called REAP , which instead stands for Relating, Extending, Actualizing, and Profiting. Introduced by Thomas Devine in 1987 , this variant is a method targeting grade and high school students with a focus on making reading notes easier to memorize by relating concepts to personalized triggers that will jog the student’s memory. This is a less common variant, but good to be aware of.

What is the REAP method suitable for?

The REAP method is primarily meant for reading texts, both fiction and non-fiction, to help you better understand texts. In this way, it is useful for most subjects that deal with texts, whether literature, social studies, or others.

While as a teaching method, it is primarily applied in grade and high school, you will often find variants of the REAP being used under different names in college-level classes. It is also a very useful method to have worked with as a student for your university studies, even when the method is not explicitly applied, as it gives you a way to approach a deeper understanding of texts that is often needed in the humanities, as well as social sciences.

However, it is possible to also apply the method to lectures and presentations. This is particularly useful for argumentative or opinion presentations or ones that are more of a story-telling character. In this case, treat listening to the presentation as the reading stage.

Is the REAP method effective?

The effective REAP method has been well-studied, with several studies showing its effectiveness. This has included showing effects on students’ ability to interact with the text , answer questions on a text , recall and summarize information , and ability to work in groups .

In recent years, there has been a surprisingly large number of studies in Indonesia on the effectiveness of REAP for a variety of student groups. These have shown clear positive results, for example, for learning English as a second language in university , as well as for fifth-grade and eighth-grade, and 11 th -grade students .

A recent study also compared the impact on critical reading skills of REAP alongside Cornell Notes and found a dramatic improvement from using either of the methods – but not any major difference between the REAP and Cornell Notes . This is a reminder that the most important thing to better understand texts is to engage with them critically – the exact method is less important, so focus on finding a method that works for you.

Advantages and disadvantages of the REAP method

While the REAP method clearly is a useful method, and share the overall benefits of taking notes , it comes with both particular advantages and disadvantages.

These are the primary advantages of the REAP method:

- A scientifically proven effective method for improving reading comprehension and recall

- Helps build capacity to engage critically with texts

- Provides a framework for re-engaging with a text from multiple vantage points

On the other hand, these are the main disadvantages of the REAP method:

- Method that takes a lot of time, focus, and mental energy

- Not suitable for note-taking during lectures

- Less suitable for all texts (such as some college textbooks) or learning purposes (such as more detailed memorization)

How to use the REAP method

So with that, let’s have a look at how to apply the REAP method in practice.

Preparations

- Step 1: Read

- Step 2: Encode

- Step 3: Annotate

- Step 4: Ponder

A common way to use the REAP method is to prepare a four-fielder on a page, using each quadrant for a stage of the REAP method. However, if you are planning to write more extensive notes, you may want to use a separate sheet for each stage.

Start with reading the text. At this stage, you only need to write down the overall topic of the text.

In our example, we’re reading an article called “The American Revolution: An Analysis.” In the Read stage, we’ll add the title of the article and the topic.

Once you have read the text, you’ll want to write down the main ideas in the text. Don’t worry if you don’t remember from your first reading – just return to the text as needed.

Returning to our example, let’s add the encoding stage and write down the main ideas from the text.

The annotation stage is critical for approaching the text from various different angles, and if possible, try to write several annotations. Below you will find a list of different types of annotations (adapted from a book by Anthony Manzo , the original author of the REAP method) – try to pick at least three of these.

- Summary Annotation: simple statement of the main ideas

- Telegram Annotation: telegram-like message of the author’s basic theme

- Poking Annotation: restatement of a lively part of the text that makes the reader want to respond

- Question Annotation: turning the main idea into a question

- Personal View Annotation: comparing the views and feelings of the reader to what the author said

- Critical Annotation: supporting, rejecting, or questioning the main idea

- Contrary Annotation: stating a contrary position

- Intention Annotation: explaining the author’s intention and purpose

- Motivation Annotation: speculation on what may have caused the author to write the text

- Discovery Annotation: questioning practical issues in the text that require further explanation

- Creative Annotation: writing better views, solutions or endings

Having worked through the text a few times, you are now ready to discuss and form arguments around the text. In the ponder stage, we’ll think about different questions that arise from our reading of the text to engage with the underlying ideas critically.

For the final step in our example, let’s consider some discussion questions. When using the method yourself, you should also write a paragraph about the question or discuss the questions in a small group – or ideally both!

Following this process should give you a solid understanding of almost any kind of text you may be faced with. As a bonus, you also have a nicely structured set of notes that can come in handy if you need to revise ahead of an exam or a presentation.

Markus Forsberg

SpanishPod101: An honest review from a native Spanish speaker

SpanishPod101 features an impressive range of material and lessons in podcast style that might not fulfill everyone’s expectations.

Kevin Hart MasterClass Review: Using Humor to Make Your Mark

If you’re interested in comedy, Kevin Hart’s MasterClass might be exactly what you need to get things started. Check out our honest review to discover more about the course.

The 7 Best Meditation Courses that Actually Help

We rounded up the top-rated meditation online courses that teach spirituality, mindfulness, and of course – meditation.

Critical Reading

Introduction to critical reading.

Critical Appraisal and Analysis (Cornell University Library) This page includes questions for your initial appraisal and content analysis of a text. Initial appraisal questions relate to the text’s author, date of publication, edition, publisher and journal title. Content analysis questions address the intended audience, objectivity, evidence, style and critical reviews.

Critical Reading (Writing@CSU) “Exhibiting an inquisitive, “critical” attitude towards what you read will make anything you read richer and more useful to you in your classes and your life. This guide is designed to help you to understand and engage this active reading process more effectively so that you can become a better critical reader.”

What is Critical Reading? (Daniel J. Kurland) This page covers facts vs. interpretation and the reasons it is important to read critically.

READING AND UNDERSTANDING ASSIGNMENT GUIDELINES

So You’ve Got a Writing Assignment. Now What? (Corrine E. Hinton, WAC Clearinghouse) (PDF) In this chapter from Writing Spaces: Readings on Writings, Volume 1 , you will find “guidelines for interpreting writing assignments” including specific questions to ask yourself as you work through understanding an assignment.

Understanding Assignments (UNC Chapel Hill, The Writing Center) “The first step in any successful college writing venture is reading the assignment. While this sounds like a simple task, it can be a tough one. This handout will help you unravel your assignment and begin to craft an effective response. Much of the following advice will involve translating typical assignment terms and practices into meaningful clues to the type of writing your instructor expects. See our online demonstration for more tips.”

Understanding Your Assignment (Vanderbilt University, Writing Studio) (PDF) On this handout, you’ll find questions to help you better understand your assignment. Questions relate to the purpose of the assignment and the audience, evidence, formatting and style for your paper.

STRATEGIES FOR CRITICALLY READING TEXTS

Annotating Texts (UNC Chapel Hill, The Writing Center) Tips for effective annotating .

Critical Reading Strategies (University of Minnesota, Center for Writing) Reading effectively requires approaching texts with a critical eye: evaluating what you read for not just what it says, but how and why it says it. Effective reading is central to both effective research (when you evaluate sources) and effective writing (when you understand how what you read is written, you can work to incorporate those techniques into your own writing). Being an effective reader also means being able to evaluate your own practices, working to develop your critical reading skills.

Critical Reading and Writing (SUNY Empire State College, Online Writing Center) “The handouts and worksheets listed and linked to here are intended to help students learn to read critically and thoughtfully.” They can help you take better notes, interpret texts based on the author’s rhetorical choices, evaluate texts, and write critical responses.

Guide to Reading Primary Sources (Univ. of Pennsylvania, Office of Learning Resources)(PDF) This guide defines a primary source, explains how reading primary and secondary sources is different and offers strategies for reading primary sources.

Playing the Believing and Doubting Games (Seton Hall University) Peter Elbow’s believing and doubting games can allow you to better read and interpret arguments by siding with and siding against different points of view. This chart shows you what to look for when approaching the text from the believing and doubting angles.

Poetry: Close Reading (Purdue OWL) “Once somewhat ignored in scholarly circles, close reading of poetry is making something of a comeback. By learning how to close read a poem you can significantly increase both your understanding and enjoyment of the poem. You may also increase your ability to write convincingly about the poem. The following exercise uses one of William Shakespeare’s sonnets (#116) as an example. This close read process can also be used on many different verse forms. This resource first presents the entire sonnet and then presents a close reading of the poem below. Read the sonnet a few times to get a feel for it and then move down to the close reading.”

Reading Critically (Harvard University, Harvard Library) Harvard University suggests six reading strategies: previewing, annotating, outlining, finding patterns, contextualizing and comparing/contrasting.

The Writing Process: Annotating a Text (Hunter College, Rockowitz Writing Center) This handout discusses the goals of annotating and explains what types of notes you should be making on the page. A sample annotated text is also included with its own system of annotations: plain, bold, and italicized font to indicate descriptions, main ideas, and commentary.

- Productivity

- Thoughtful learning

Annotating text: The complete guide to close reading

As students, researchers, and self-learners, we understand the power of reading and taking smart notes . But what happens when we combine those together? This is where annotating text comes in.

Annotated text is a written piece that includes additional notes and commentary from the reader. These notes can be about anything from the author's style and tone to the main themes of the work. By providing context and personal reactions, annotations can turn a dry text into a lively conversation.

Creating text annotations during close readings can help you follow the author's argument or thesis and make it easier to find critical points and supporting evidence. Plus, annotating your own texts in your own words helps you to better understand and remember what you read.

This guide will take a closer look at annotating text, discuss why it's useful, and how you can apply a few helpful strategies to develop your annotating system.

What does annotating text mean?

Text annotation refers to adding notes, highlights, or comments to a text. This can be done using a physical copy in textbooks or printable texts. Or you can annotate digitally through an online document or e-reader.

Generally speaking, annotating text allows readers to interact with the content on a deeper level, engaging with the material in a way that goes beyond simply reading it. There are different levels of annotation, but all annotations should aim to do one or more of the following:

- Summarize the key points of the text

- Identify evidence or important examples

- Make connections to other texts or ideas

- Think critically about the author's argument

- Make predictions about what might happen next

When done effectively, annotation can significantly improve your understanding of a text and your ability to remember what you have read.

What are the benefits of annotation?

There are many reasons why someone might wish to annotate a document. It's commonly used as a study strategy and is often taught in English Language Arts (ELA) classes. Students are taught how to annotate texts during close readings to identify key points, evidence, and main ideas.

In addition, this reading strategy is also used by those who are researching for self-learning or professional growth. Annotating texts can help you keep track of what you’ve read and identify the parts most relevant to your needs. Even reading for pleasure can benefit from annotation, as it allows you to keep track of things you might want to remember or add to your personal knowledge management system .

Annotating has many benefits, regardless of your level of expertise. When you annotate, you're actively engaging with the text, which can help you better understand and learn new things . Additionally, annotating can save you time by allowing you to identify the most essential points of a text before starting a close reading or in-depth analysis.

There are few studies directly on annotation, but the body of research is growing. In one 2022 study, specific annotation strategies increased student comprehension , engagement, and academic achievement. Students who annotated read slower, which helped them break down texts and visualize key points. This helped students focus, think critically , and discuss complex content.

Annotation can also be helpful because it:

- Allows you to quickly refer back to important points in the text without rereading the entire thing

- Helps you to make connections between different texts and ideas

- Serves as a study aid when preparing for exams or writing essays

- Identifies gaps in your understanding so that you can go back and fill them in

The process of annotating text can make your reading experience more fruitful. Adding comments, questions, and associations directly to the text makes the reading process more active and enjoyable.

Be the first to try it out!

We're developing ABLE, a powerful tool for building your personal knowledge, capturing information from the web, conducting research, taking notes, and writing content.

How do you annotate text?

There are many different ways to annotate while reading. The traditional method of annotating uses highlighters, markers, and pens to underline, highlight, and write notes in paper books. Modern methods have now gone digital with apps and software. You can annotate on many note-taking apps, as well as online documents like Google Docs.

While there are documented benefits of handwritten notes, recent research shows that digital methods are effective as well. Among college students in an introductory college writing course, those with more highlighting on digital texts correlated with better reading comprehension than those with more highlighted sections on paper.

No matter what method you choose, the goal is always to make your reading experience more active, engaging, and productive. To do so, the process can be broken down into three simple steps:

- Do the first read-through without annotating to get a general understanding of the material.

- Reread the text and annotate key points, evidence, and main ideas.

- Review your annotations to deepen your understanding of the text.

Of course, there are different levels of annotation, and you may only need to do some of the three steps. For example, if you're reading for pleasure, you might only annotate key points and passages that strike you as interesting or important. Alternatively, if you're trying to simplify complex information in a detailed text, you might annotate more extensively.

The type of annotation you choose depends on your goals and preferences. The key is to create a plan that works for you and stick with it.

Annotation strategies to try

When annotating text, you can use a variety of strategies. The best method for you will depend on the text itself, your reason for reading, and your personal preferences. Start with one of these common strategies if you don't know where to begin.

- Questioning: As you read, note any questions that come to mind as you engage in critical thinking . These could be questions about the author's argument, the evidence they use, or the implications of their ideas.

- Summarizing: Write a brief summary of the main points after each section or chapter. This is a great way to check your understanding, help you process information , and identify essential information to reference later.

- Paraphrasing: In addition to (or instead of) summaries, try paraphrasing key points in your own words. This will help you better understand the material and make it easier to reference later.

- Connecting: Look for connections between different parts of the text or other ideas as you read. These could be things like similarities, contrasts, or implications. Make a note of these connections so that you can easily reference them later.

- Visualizing: Sometimes, it can be helpful to annotate text visually by drawing pictures or taking visual notes . This can be especially helpful when trying to make connections between different ideas.

- Responding: Another way to annotate is to jot down your thoughts and reactions as you read. This can be a great way to personally engage with the material and identify any areas you need clarification on.

Combining the three-step annotation process with one or more strategies can create a customized, powerful reading experience tailored to your specific needs.

ABLE: Zero clutter, pure flow

Carry out your entire learning, reflecting and writing process from one single, minimal interface. Focus modes for reading and writing make concentrating on what matters at any point easy.

7 tips for effective annotations

Once you've gotten the hang of the annotating process and know which strategies you'd like to use, there are a few general tips you can follow to make the annotation process even more effective.

1. Read with a purpose. Before you start annotating, take a moment to consider what you're hoping to get out of the text. Do you want to gain a general overview? Are you looking for specific information? Once you know what you're looking for, you can tailor your annotations accordingly.

2. Be concise. When annotating text, keep it brief and focus on the most important points. Otherwise, you risk annotating too much, which can feel a bit overwhelming, like having too many tabs open . Limit yourself to just a few annotations per page until you get a feel for what works for you.

3. Use abbreviations and symbols. You can use abbreviations and symbols to save time and space when annotating digitally. If annotating on paper, you can use similar abbreviations or symbols or write in the margins. For example, you might use ampersands, plus signs, or question marks.

4. Highlight or underline key points. Use highlighting or underlining to draw attention to significant passages in the text. This can be especially helpful when reviewing a text for an exam or essay. Try using different colors for each read-through or to signify different meanings.

5. Be specific. Vague annotations aren't very helpful. Make sure your note-taking is clear and straightforward so you can easily refer to them later. This may mean including specific inferences, key points, or questions in your annotations.

6. Connect ideas. When reading, you'll likely encounter ideas that connect to things you already know. When these connections occur, make a note of them. Use symbols or even sticky notes to connect ideas across pages. Annotating this way can help you see the text in a new light and make connections that you might not have otherwise considered.

7. Write in your own words. When annotating, copying what the author says verbatim can be tempting. However, it's more helpful to write, summarize or paraphrase in your own words. This will force you to engage your information processing system and gain a deeper understanding.

These tips can help you annotate more effectively and get the most out of your reading. However, it’s important to remember that, just like self-learning , there is no one "right" way to annotate. The process is meant to enrich your reading comprehension and deepen your understanding, which is highly individual. Most importantly, your annotating system should be helpful and meaningful for you.

Engage your learning like never before by learning how to annotate text

Learning to effectively annotate text is a powerful tool that can improve your reading, self-learning , and study strategies. Using an annotating system that includes text annotations and note-taking during close reading helps you actively engage with the text, leading to a deeper understanding of the material.

Try out different annotation strategies and find what works best for you. With practice, annotating will become second nature and you'll reap all the benefits this powerful tool offers.

I hope you have enjoyed reading this article. Feel free to share, recommend and connect 🙏

Connect with me on Twitter 👉 https://twitter.com/iamborisv

And follow Able's journey on Twitter: https://twitter.com/meet_able

And subscribe to our newsletter to read more valuable articles before it gets published on our blog.

Now we're building a Discord community of like-minded people, and we would be honoured and delighted to see you there.

Straight from the ABLE team: how we work and what we build. Thoughts, learnings, notes, experiences and what really matters.

Read more posts by this author

follow me :

Learning with a cognitive approach: 5 proven strategies to try

What is knowledge management the answer, plus 9 tips to get started.

Managing multiple tabs: how ABLE helps you tackle tab clutter

What is abstract thinking? 10 activities to improve your abstract thinking skills

0 results found.

- Aegis Alpha SA

- We build in public

Building with passion in

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

3 – Notes and Annotation

Engaging actively with a text.

Note-taking is perhaps one of the most under-valued steps in the writing process. You may, as many writers before you, be tempted to skip note-taking entirely! In our world today, speed and convenience are prioritized more often than not. However, quality writing assignments typically start with a humble beginning. Taking high-quality notes based on your reading material will save time later on in the writing process.

Activity 1: The Benefit of Notes

Read the following paragraph, which is an excerpt from The Fallacy of Success by British writer, philosopher, and literary/art critic, G.K. Chesterton, who is often considered one of the greatest minds of the 20th century.

When finished, see how many ideas you can remember without looking at the text after one minute.

From The Fallacy of Success by G.K. Chesterton

“There has appeared in our time a particular class of books and articles which I sincerely and solemnly think may be called the silliest ever known among men. They are much more wild than the wildest romances of chivalry and much more dull than the dullest religious tract. Moreover, the romances of chivalry were at least about chivalry; the religious tracts are about religion. But these things are about nothing; they are about what is called Success.

On every bookstall, in every magazine, you may find works telling people how to succeed. They are books showing men how to succeed in everything; they are written by men who cannot even succeed in writing books. To begin with, of course, there is no such thing as Success. Or, if you like to put it so, there is nothing that is not successful. That a thing is successful merely means that it is; a millionaire is successful in being a millionaire and a donkey in being a donkey. Any live man has succeeded in living; any dead man may have succeeded in committing suicide.

But, passing over the bad logic and bad philosophy in the phrase, we may take it, as these writers do, in the ordinary sense of success in obtaining money or worldly position. These writers profess to tell the ordinary man how he may succeed in his trade or speculation – how, if he is a builder, he may succeed as a builder; how, if he is a stockbroker, he may succeed as a stockbroker. They profess to show him how, if he is a grocer, he may become a sporting yachtsman; how, if he is a tenth-rate journalist, he may become a peer; and how, if he is a German Jew, he may become an Anglo-Saxon.

This is a definite and business-like proposal, and I really think that the people who buy these books (if any people do buy them) have a moral, if not a legal, right to ask for their money back. Nobody would dare to publish a book about electricity which literally told one nothing about electricity; no one would dare publish an article on botany which showed that the writer did not know which end of a plant grew in the earth. Yet our modern world is full of books about Success and successful people which literally contain no kind of idea, and scarcely any kind of verbal sense.”

Ideas you remember from the text (without taking notes):

Now, read the paragraph again. This time take a few notes as you read on a separate sheet of paper about the main ideas. Then, after one minute, write down what you remember.

Ideas you remember from the text (after taking notes):

How did you do? Were you able to remember more after taking some notes? Chances are that you did!

This quote from How to Read a Book might give you a better understanding of why note-taking is a crucial part of the writing process:

“Why is marking a book indispensable to reading it? First, it keeps you awake—not merely conscious, but wide awake. Second, reading, if active, is thinking, and thinking tends to express itself in words, spoken or written. The person who says he knows what he thinks but cannot express it usually does not know what he thinks. Third, writing your reactions down helps you r emember the thoughts of the author” (Adler and Van Doren, p. 49).