Filter by Keywords

People Management

How to create high-performing self-managed teams.

Senior Content Marketing Manager

February 5, 2024

While management styles may vary greatly, most successful business leaders agree that an organization’s greatest assets are its people. 🧑🏼🤝🧑🏽

But if you hire the best, empowering them to bring their best selves to work makes sense. Increasingly, management gurus have turned to self-management to build independent, self-motivated, productive, and highly creative teams.

As the name suggests, unlike traditional teams, self-managed teams work autonomously without direct supervision, though they may still report to a supervisor or team leader when needed. Organizations rely on self-managed individuals to do their jobs well without micromanagement.

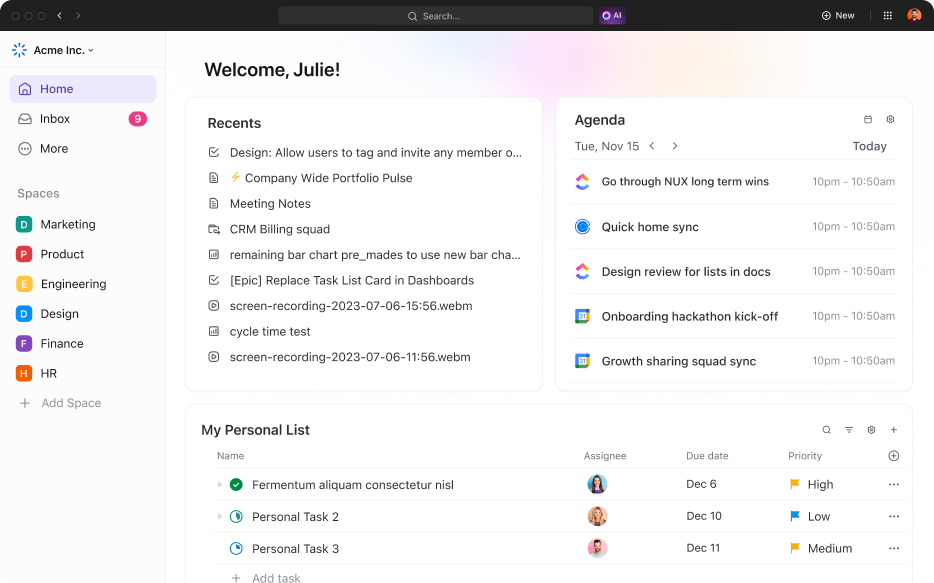

And with the help of tools like ClickUp for Teams , self-managed work teams can flourish as they drive organizational growth.

In this blog post, we’ll take a deep dive into this management style to see how you can build self-managed teams in your organization.

Understanding Self-Managed Teams

1. autonomy, 2. collaboration, 3. ownership, 4. accountability, 5. continuous improvement, pros of self-managed teams, cons of self-managed teams, define self-managed teams, look out for signs, identify interested team members, set clear goals and objectives, develop team roles and responsibilities, allocate and track tasks , open channels for communication , establish decision-making mechanisms, provide resources, set result-based timelines, assess the effectiveness of your self-managed team, help your self-managed teams thrive.

Unlike a traditional project or agile team headed by a more conventional manager or supervisor, a self-managed team is typically a small, self-directed unit without a traditional hierarchical or top-down organizational structure.

All team members own their goals, tasks, and responsibilities to drive outcomes.

There’s no hierarchy within a self-managed team. Instead, team members discuss the scope and limits of each others’ responsibilities and are empowered to make decisions within those areas. As a result, each person can manage their workload how they see fit.

Since every process and output is discussed within the team before they reach a final consensus, self-managed teams are ‘semi-autonomous.’ Power is decentralized, and overall accountability is shared.

Self-governance is a key concept at play here. Every self-managed individual is responsible for both their individual performance and the overall business goal. And though they must operate within the guidelines for a specific project, they are free to work in the way that best suits them.

This also means that some self-managed teams enjoy unlimited time off. They can take vacation days or abbreviated workdays as long as the project progresses as planned. Expectedly, successful self-managed teams are built on a strong foundation of trust and ownership.

Key Characteristics of Self-Managed Teams

Self-managed teams have emerged as a powerful force, driving innovation, fostering creativity, and enhancing organizational culture through greater employee engagement. To fully understand the essence of self-managed teams, let’s look at the defining characteristics distinguishing them from more traditional management teams.

In a self-managed team, autonomy takes center stage. Team members of these fully autonomous teams can make decisions about their work, prioritize tasks, and solve problems without constant supervision.

This delegation of power enables a sense of ownership, balancing autonomy and responsibility among the entire team, driving them to take initiative and find creative solutions.

Autonomy is also characterized by:

- Informed decision-making power: Equip your team with knowledge and expertise to make informed decisions aligned with team goals

- Effective time management: Give your team autonomy over their schedules, allowing them to optimize productivity and minimize distractions

- Creative problem-solving: Empower team members to brainstorm solutions independently and enable a culture of innovation and effective problem-solving

Self-managed teams excel at collaboration. The team has self-motivation and works together to share ideas, solve problems, and achieve common goals. This collaborative approach of a self-managing team can lead to more creative solutions, strong communication, improved efficiency, and a stronger sense of team spirit.

Effective collaboration results in

- Mutual respect: Encourage the team to value and respect each other’s contributions for better outcomes

- Active listening: Ensure everyone’s ideas are heard and considered through active listening

- Shared decision-making: Collaborate as a team to make decisions using collective expertise and insights

Self-managed teams are driven by a strong sense of ownership, where team members take pride in their work and feel a personal stake in the project’s or team’s success or failure. This ownership increases motivation, better decision-making, and a heightened commitment to delivering high-quality results.

Benefits of ownership include:

- Increased productivity and performance: When team members have full ownership of their work, they are intrinsically motivated to perform well and increase productivity

- Reduced reliance on managers: Such teams don’t need managers for day-to-day tasks, as they manage themselves.

- Improved decision-making: Teams that take responsibility for their outcomes actively collect information to make better decisions, and have a problem-solving approach to work

Accountability is a cornerstone of self-managed teams. Team members are collectively responsible for their contributions and the team’s overall project success. This shared accountability drives individuals to perform their best and ensures the entire team stays focused on achieving its goals.

Accountability results in:

- Individual responsibility: Team members hold themselves accountable for their individual performance as well as team outcomes

- Improved team performance: Team members also hold each other accountable to achieve better results

- Reduced conflict: Shared responsibilities prevent tension from escalating and enable effective conflict resolution

Successful self-managed teams thrive on continuous improvement. Team members are encouraged to learn, grow, and adapt to challenges. This commitment to improvement drives the self-directed team to seek new working methods, refine processes, and deliver exceptional results.

Continuous improvement leads to:

- Increased efficiency: Consistently identifying and eliminating processes, workflows, and products that create inefficiency improves productivity

- Improved customer satisfaction: Continuous improvement of processes and practices helps the organization provide better products and services to customers

Pros and Cons of Self-Managed Teams

Just as every management model has its flipside, self-managed teams have pros and cons too.

Building self-managed teams has several advantages, such as high productivity and motivation, quick decision-making, and cost savings. Let’s break this down.

Improved productivity and skills

Self-managed teams are typically far more productive than traditional ones. Because ownership and accountability factor so heavily in self-managed units, they usually work harder than traditionally structured teams. They may even acquire new skills to ensure they remain worthy of the ‘self-managed’ tag.

Thus, self-managed individuals tend to develop stronger discipline in their jobs.

Enhanced motivation and engagement

The team’s performance reflects its efforts, so employees feel more motivated to put their best foot forward. Working toward a shared goal while owning specific tasks also improves morale and motivation. Being in a successful self-managed team makes employees feel more empowered and pushes them to give their best to the project.

Improved decision-making

Self-managed teams are self-reliant. Their laser focus on the outcome of a project means they tend to make well-informed, collaborative decisions, even on complex matters.

Increased efficiency

Self-managed teams operate in a lean hierarchy, with no middle management layer between them and leadership. This reduces the possibility of miscommunication, increases autonomous decision-making, and allows for fast and collaborative action.

Higher cost-effectiveness

With self-managed teams, organizations save the cost of hiring, training, and retaining managers and supervisors. In addition, as such teams tend to be more efficient and productive, they save time and money and help the entire organization generate higher profits.

It’s not always sunny in the world of self-management. Here are some disadvantages to self-managed teams.

Conflicts and differences of opinion

Diversity is a boon for organizations. But when people come from different backgrounds and areas of expertise, they are bound to have different perspectives. In the decentralized world of self-managed teams, differences in opinion can slow down decision-making and potentially create conflicts.

Employees need to be trained to handle these differences tactfully and productively.

Accountability versus autonomy

Complete autonomy, in the wrong hands, can incur a steep cost. So, self-managed teams (and individual members) must be fully accountable for their performance and outcomes.

In such small and focused teams, if even a single team member abuses their autonomy, it impacts the whole team. Projects don’t go as planned, and organizations incur losses. This is a significant risk when it comes to self-managed teams.

Potential for loss of direction

Building self-managed teams requires time and careful thought. Selected employees might not be the right fit for self-management, which could hinder team performance. Also, if the right guidance and proper training are not provided to the self-directed team initially, it could quickly lose direction.

Building a Successful Self-Managed Team: A Step-by-Step Guide

Self-managed teams can unlock the floodgates of productivity and innovation for your company. But it has to be done right.

Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to build high-performing, resilient, self-managed teams.

First, define what a ‘self-managed team’ means to you. Are you looking for a semi or fully autonomous team? Does it include people with specific skill sets, for instance, problem-solving skills? Do you want to develop autonomous teams for products or services or another specific task?

Determine what definition of self-directed teams works best for your organization, both functionally and culturally. Then, follow the next steps to create a high-performing, self-managed work team.

The next logical step in implementing self-managed teams is to gauge if your employees show any of the above mentioned characteristics or traits. Recall that an ideal self-managed team consists of people who are self-driven, trustworthy, confident in decision-making, great at time management, and strong communicators.

Once you’ve evaluated candidates who’d be perfect in self-managed roles, ask them if they’re interested. Not everyone may be. Irrespective of ability, many employees might rather have a manager to guide and direct them.

It’s important to seek out individuals who are keen to upskill and improve constantly and are confident enough to handle problems independently. The possible team members must also possess the interpersonal skills to work well in a team of similarly independent-minded individuals.

You can use various team-building techniques to ensure your self-managed team members gel well.

Next, define the goals and objectives you want your self-managed team to achieve. Lay out the expected output and outcomes clearly so the team knows what they’re working toward. Also, explain how you’ll be measuring these outcomes.

The best practice is to create achievable goals by using ClickUp Goals and assigning them to the relevant people. You can also set up channels to measure productivity .

Now that you’ve laid a clear roadmap of your expectations and mission strategy, plan to evaluate your team’s performance too. ClickUp’s Performance Reviews template will help you do that.

Conduct self-appraisals and give feedback with the help of this template.

Assign clear roles and responsibilities to the self-managing teams. Make it clear that each member is on a lateral hierarchy scale rather than top-down on a traditional team structure. As a backup, create a mechanism allowing an external leader or others to chip in when an employee fails to complete their work.

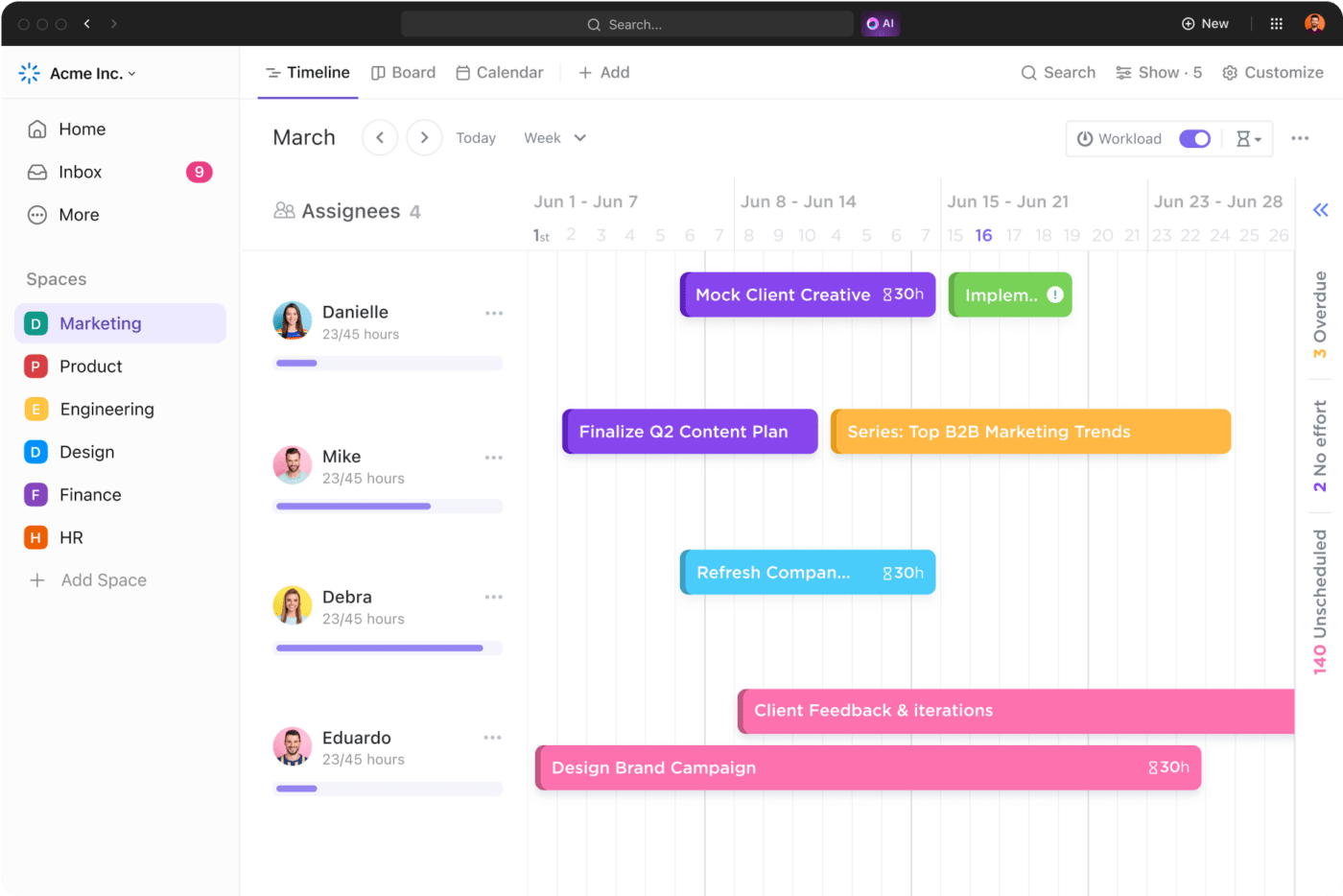

Now that the groundwork is done, it’s time to allocate tasks to individual team members and the team as a whole. Efficient task management using tools like ClickUp Tasks can significantly improve team productivity.

Again, though the project team will work independently once they begin, you can still track their progress using ClickUp’s project management tool . This tool provides an overview of priorities, cross-team work, and project progress.

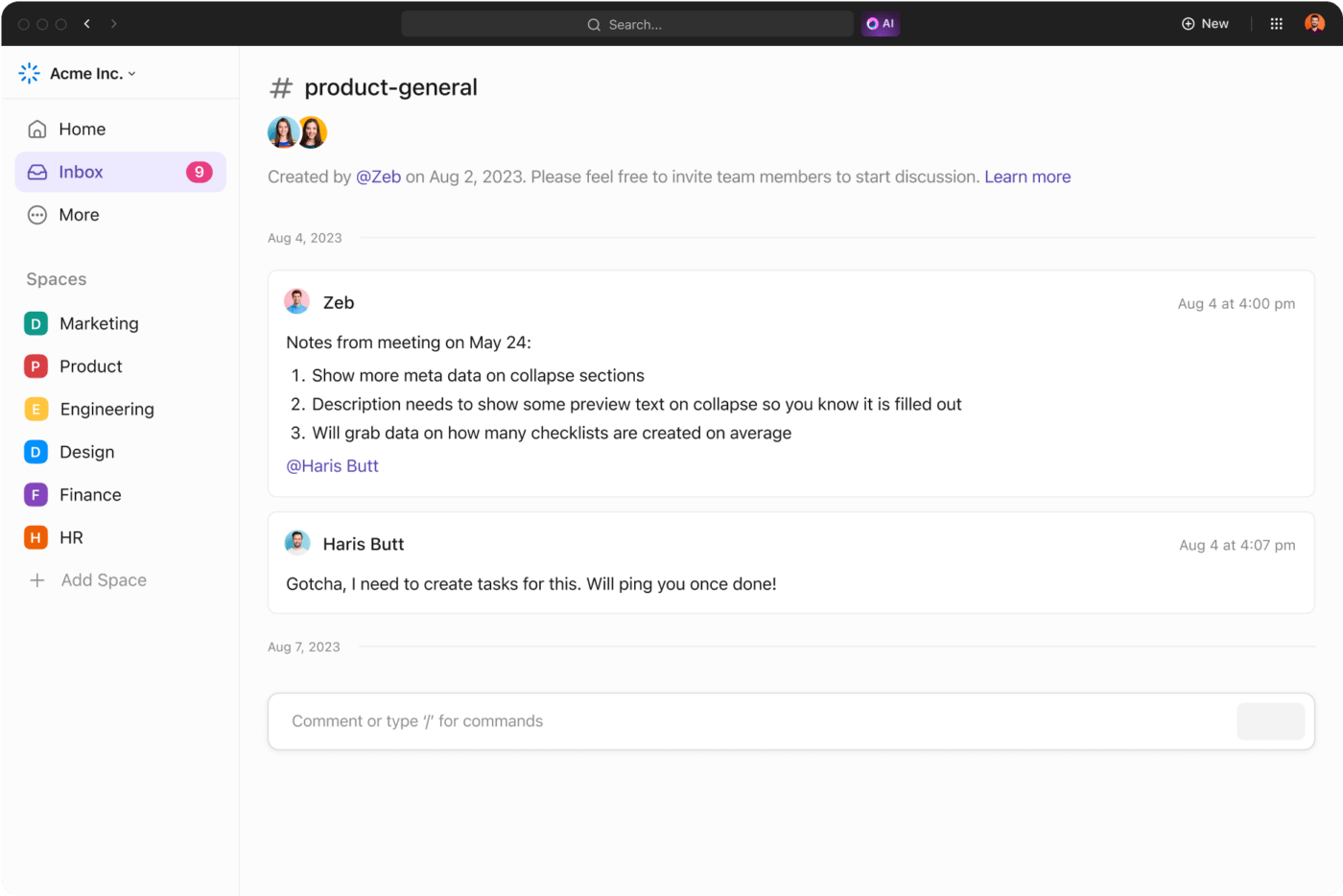

Create fixed channels for communication, such as stand-up meetings, discussion forums, weekly or monthly video calls, or whatever else works best.

ClickUp Chat offers a breakthrough in reliable and real-time team communication. You can integrate 1,000+ tools and apps on ClickUp to ensure seamless and precise communication.

In a disciplined, self-directed team , no employee is vested with more authority than the other. This departure from a traditional management hierarchy can sometimes hinder the decision-making process.

To overcome this, you can appoint someone as a ‘facilitator,’ or the team can elect a facilitator. A facilitator serves as a mediator who runs meetings, manages conflict, and ensures overall consensus.

Provide training and empower your team with the tools they need to succeed. This could be a monetary amount disbursed during the initial setup, software for managing and tracking work , or full access to a repository of tools they can use as required.

ClickUp Templates are great for self-driven teams to pick and choose what they need to function. You can find templates for project management from SWOT analysis and SIPOC (suppliers, inputs, process, outputs, customers) frameworks. Teams can use these templates to plan, strategize, execute, allocate, and measure their work.

As modern businesses, we’re all working against the clock. Set clear, realistic deadlines that allow for contingencies while keeping team members on their toes and accomplishing goals. Since you’ve already clearly defined what constitutes success, ensure your self-driven team achieves what they set out to within the required time frame.

Finally, take a long, hard look at the data once your project ends. Closely analyzing the metrics of a project executed by a self-managed team will help you make the required changes, whether those have to do with the team itself, the nature of the tasks, the resources provided, etc.

Keep improving with every iteration.

Setting up a self-managed team can be tricky. It needs careful planning, a strong understanding of the risks and advantages, and, most importantly, selecting the right people.

ClickUp’s convenient integration with 1,000+ tools, easy-to-use templates, automated workflows, and intuitive dashboards simplify planning, strategy, and execution for your self-managed teams.

Get closer to your productivity and efficiency goals with detailed analytics, privacy controls, and the freedom to link your favorite project tools.

Sign up with ClickUp today !

Questions? Comments? Visit our Help Center for support.

Receive the latest WriteClick Newsletter updates.

Thanks for subscribing to our blog!

Please enter a valid email

- Free training & 24-hour support

- Serious about security & privacy

- 99.99% uptime the last 12 months

How it works

Transform your enterprise with the scalable mindsets, skills, & behavior change that drive performance.

Explore how BetterUp connects to your core business systems.

We pair AI with the latest in human-centered coaching to drive powerful, lasting learning and behavior change.

Build leaders that accelerate team performance and engagement.

Unlock performance potential at scale with AI-powered curated growth journeys.

Build resilience, well-being and agility to drive performance across your entire enterprise.

Transform your business, starting with your sales leaders.

Unlock business impact from the top with executive coaching.

Foster a culture of inclusion and belonging.

Accelerate the performance and potential of your agencies and employees.

See how innovative organizations use BetterUp to build a thriving workforce.

Discover how BetterUp measurably impacts key business outcomes for organizations like yours.

A demo is the first step to transforming your business. Meet with us to develop a plan for attaining your goals.

- What is coaching?

Learn how 1:1 coaching works, who its for, and if it's right for you.

Accelerate your personal and professional growth with the expert guidance of a BetterUp Coach.

Types of Coaching

Navigate career transitions, accelerate your professional growth, and achieve your career goals with expert coaching.

Enhance your communication skills for better personal and professional relationships, with tailored coaching that focuses on your needs.

Find balance, resilience, and well-being in all areas of your life with holistic coaching designed to empower you.

Discover your perfect match : Take our 5-minute assessment and let us pair you with one of our top Coaches tailored just for you.

Research, expert insights, and resources to develop courageous leaders within your organization.

Best practices, research, and tools to fuel individual and business growth.

View on-demand BetterUp events and learn about upcoming live discussions.

The latest insights and ideas for building a high-performing workplace.

- BetterUp Briefing

The online magazine that helps you understand tomorrow's workforce trends, today.

Innovative research featured in peer-reviewed journals, press, and more.

Founded in 2022 to deepen the understanding of the intersection of well-being, purpose, and performance

We're on a mission to help everyone live with clarity, purpose, and passion.

Join us and create impactful change.

Read the buzz about BetterUp.

Meet the leadership that's passionate about empowering your workforce.

For Business

For Individuals

What are self-managed teams (and how can you create them)?

Jump to section

What are the four types of teams?

What are self-managed teams, what are the benefits of self-managed teams, what are the cons of self-managed teams, what are the characteristics of self-managed teams, are you ready to build a self-managed team, how to move toward self-managed teams, help your teams thrive.

We all know teamwork makes the dream work. But does every team need a manager at the helm?

Even though hierarchies and defined leaders have reigned for most of the industrial age, some companies are reconsidering whether that structure still works for their business.

Self-managed teams are becoming more popular at companies of all sizes. But how do they work, and how do you know if they’ll work for your business?

In this article, we’ll explore what self-managed teams are, the characteristics of self-managed teams, and how to start developing them.

Many companies stick to the traditional team management hierarchy because that’s what they know.

The traditional manager role may be quickly disappearing in response to calls for new ways to look at team management. In fact, 37% of managers think their position will disappear in the next five years.

Here are four alternatives to the traditional management style.

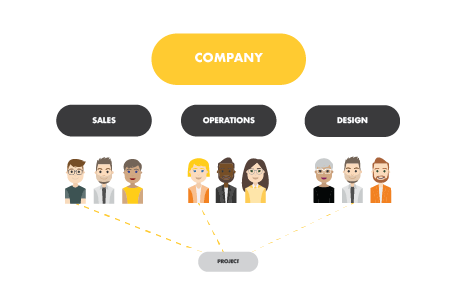

Project teams

Project teams are cross-functional groups with specialists from different departments who work together on specific projects. A project manager often leads these teams.

A project team usually works together for a fixed length of time and disbands once the project is complete. These teams may be measured on outcome but are often measured on execution to a plan (e.g., completing tasks with a defined time and budget).

Self-managed teams

A self-managed work team is a small group of employees who take full responsibility for delivering a service or product through peer collaboration without a manager’s guidance.

This team often works together long-term to make decisions about a particular process. These teams may be measured either by output or outcome, with outcome being the better choice.

Virtual teams

A virtual team consists of employees from different regions working remotely or in different offices. They primarily communicate through video conferencing, phone calls, messaging, and email. Any of the other team types may also be a virtual team.

Operational teams

Operational, or functional, teams are groups of employees dedicated to a specific ongoing role, like customer support or sales. All the members of an operational team support one overarching goal and process. They tend to measure themselves on output rather than outcome.

Sign up to receive the latest insights, resources, and tools from BetterUp

Thank you for your interest in BetterUp.

While self-managed teams aren’t new, they are seeing a surge in popularity as remote work becomes the new normal. Plus, with managers feeling less supported by the organization and less able to effectively navigate rapid change, more teams may experiment with self-management by choice or necessity.

Self-directed teams take full ownership and responsibility to drive business results for a particular process. Unlike an operational team, most self-managed teams don’t have a hierarchy. Instead, self-designing teams have more autonomy over their processes and roles within the bounds of what team members agree is needed to achieve agreed upon team outcomes.

A self-managed team also has more discretion over decision-making within their process and how the entire team is managed. While this can pose some unique leadership challenges , it also offers leadership opportunities and skill development that may not be accessible for a traditional team.

Younger generations entering the workforce are more interested in developing expertise than in rising through the ranks, which 51% of managers see as an opportunity. Even among other generations, workers are becoming more aware of the need to stay relevant and gain new skills and experiences. Self-managed teams are a great way to expand employees’ experience and allow them to try out and master new capabilities through rotating roles and learning from other teammates.

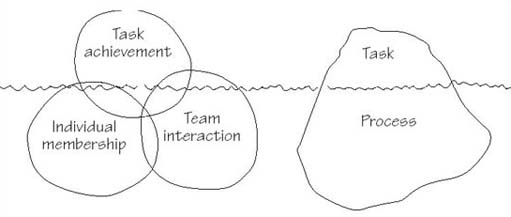

Good self-managed teams demonstrate many of the benefits of having a great manager. These teams often develop more effective decision-making practices that combine considering more viewpoints, more natural collaboration and give-and-take, and moving toward action to remove obstacles and stay focused on the shared outcomes.

( Image source )

The close-knit, communal feel of autonomous teams can drive innovation and motivation, too. Each team member feels personally responsible for team performance, inspiring employees to do excellent work and share ideas for improvement more readily.

Fewer barriers in their work can lead to increased productivity, too. Since as far back as 2001, companies like RCAR Electronics have reported saving $10 million annually after implementing self-managed teams, showcasing the benefits that self-management can offer.

Despite the benefits, self-managed teams are hardly a silver bullet to productivity. Implementing and adapting to any new structure can be difficult, and self-managed teams are no exception.

Self-managed teams often take a long time to set up and execute effectively. Certain employees may not be the right fit for self-management, and camaraderie, commitment, and competence are needed before seeing the benefits of a successful self-managed team.

Plus, without the proper training, self-managed teams can flounder and lose motivation.

One major concern around self-managed teams is inequality. Compared to traditional teams, some self-managed teams have seen a 24% estimated pay gap for women. This inequality can lead to stifled innovation when members fear sharing ideas and a team succumbs to groupthink.

Excessive meetings and a disconnect from overall business goals can also set a self-governing team off on the wrong track. Before developing autonomous teams, it’s crucial to give members the right training and guidance on their role in an organization.

When self-managed teams are implemented right, they’re known for being highly effective, innovative, and driven.

Here are a few key characteristics that distinctly set great self-managed teams apart from other team structures.

They’re self-driven

These teams collaborate on one central, common goal every day. They know the target, and they’re driven to support their team and do their part. No one waits for a manager or another team member to tell them what to do.

They trust each other

Self-managed teams are all-for-one and one-for-all. These teams innovate well because they are comfortable with each other and share their ideas freely. They know their team is dedicated to doing the best work possible together.

67% of employees say they would go above and beyond if they felt valued and engaged. These team members embody employee engagement and often excel for the benefit of the team.

Employee-driven decisions are the norm

Leadership is a must for self-managed teams, but no one person takes on the leader role. Instead, everyone contributes to decisions. These teams know their process best, and the organization trusts them to make informed decisions within reason.

They have high self-awareness

Self-managed team members are always looking for ways to improve their performance and the overall process. These teams know that without their effort, a service or product doesn’t get completed.

They have strong communication

63% of employees have wanted to quit because poor communication got in the way of their jobs.

Being on a team that values and prioritizes open communication helps self-organizing teams thrive. These teams readily contribute their opinions and unique experiences to drive the team forward.

Not every team is ready to be self-managed. But, if you already have team members going above and beyond their specialties, a self-managed team may be a good option.

Jumping into self-managed teams can be challenging, and you risk losing your team’s best people if the experiment falls flat. Without the proper training and structure, adapting to a self-managed team is often a more significant undertaking than many organizations realize.

Here are some innovative steps that you can take to ease into self-managed teams.

Gauge interest from possible team members

Identify employees that could be a good fit for a self-managed team and see if they are interested in participating.

Provide guidance and guardrails

Self-management should mean rudderless. These teams do best when they understand the organization’s larger goals and values and cann check-in to stay aligned to them. Leadership can be clear about the boundaries for teams and help them define what outcomes will matter most.

Define team objectives and goals

Clarify why a self-managed team is best for a service or process, then define your new team’s guiding principles and goals.

Develop team roles and decision-making standards

A self-managed team needs base guidelines to thrive. Defining who does what and how decisions are made can set your team on the path to success.

Offer training for employees

Provide training on how self-managed teams work and how the process will adapt to the new team style.

Practice on a project with a volunteer team

Before diving in, set up your employees to walk through a particular process together for practice, slowly adding self-management features. Then, get ongoing feedback on how the team can run more smoothly.

BE THE FIRST TO KNOW

Stay up to date with new resources and insights.

Shifting to self-managed teams isn’t easy. But, with time and commitment, you can create a strong, productive team that offers unique benefits for your company.

If you’re ready to adopt self-managing teams, we have you covered. At BetterUp, we offer the coaching your employees need to thrive in any type of team. Sign up today to help your employees meet their full potential.

Lead with confidence and authenticity

Develop your leadership and strategic management skills with the help of an expert Coach.

Elizabeth Perry, ACC

Elizabeth Perry is a Coach Community Manager at BetterUp. She uses strategic engagement strategies to cultivate a learning community across a global network of Coaches through in-person and virtual experiences, technology-enabled platforms, and strategic coaching industry partnerships. With over 3 years of coaching experience and a certification in transformative leadership and life coaching from Sofia University, Elizabeth leverages transpersonal psychology expertise to help coaches and clients gain awareness of their behavioral and thought patterns, discover their purpose and passions, and elevate their potential. She is a lifelong student of psychology, personal growth, and human potential as well as an ICF-certified ACC transpersonal life and leadership Coach.

Agile performance management: How to improve an agile team

Leading from a distance: ideas for supporting your remote workforce in times of change, managers have a strong effect on team performance, for better or worse, 5 ways managers can lead through crises, why every successful manager needs leadership coaching, 7 management skills to guide teams through turbulent times, from self-awareness to self-control: a powerful leadership technique, how to develop emotional regulation skills to become a better manager, how managers get upward feedback from their team, similar articles, what is strategic plan management and how does it benefit teams, what does the future of management look like, the success behind virtual teams: the ultimate guide, what is productivity definition and ways to improve, autonomy at work is important: here are 9 ways to encourage it, what are decentralized organizations, roles and responsibilities: why defining them is important, accountability vs. responsibility for leaders: back to the basics, build an agile organization with these 5 tactics, stay connected with betterup, get our newsletter, event invites, plus product insights and research..

3100 E 5th Street, Suite 350 Austin, TX 78702

- Platform Overview

- Integrations

- Powered by AI

- BetterUp Lead™

- BetterUp Manage™

- BetterUp Care®

- Sales Performance

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Case Studies

- Why BetterUp?

- About Coaching

- Find your Coach

- Career Coaching

- Communication Coaching

- Life Coaching

- News and Press

- Leadership Team

- Become a BetterUp Coach

- BetterUp Labs

- Center for Purpose & Performance

- Leadership Training

- Business Coaching

- Contact Support

- Contact Sales

- Privacy Policy

- Acceptable Use Policy

- Trust & Security

- Cookie Preferences

Self-managed teams: what they are and how to implement them

Getting maximum productivity and engagement from teams is at the top of the priority list for most companies. One management technique that has long been a staple in the manufacturing industry - and which has gained popularity elsewhere in recent years - is the concept of self-managed teams .

This article will act as a primer on the idea of self-managed teams, and offer you insights into what actions you should take to maximize employee output using this management style.

What does it mean to have a self-managed team?

Self-managed teams have been around since the 1960s, but have seen a significant increase in popularity over the past decade or so. They are now present in a sizable portion of the Fortune 1000, and are used to drive stronger innovation, productivity, and overall employee satisfaction .

It’s a management technique where a group of employees is brought together and given responsibility and accountability over all or most aspects of producing a product or delivering a service.

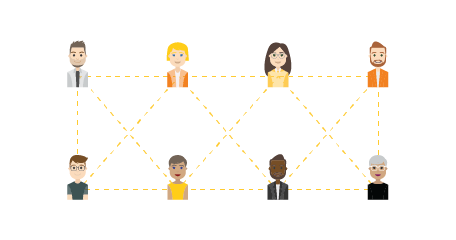

The key difference between a typical project team and self-managed teams is that they are self-organized and semi-autonomous . That means that there is no defined hierarchy on the team. Instead, management and technical responsibility are rotated amongst the team members under pre-defined guidelines for collaboration.

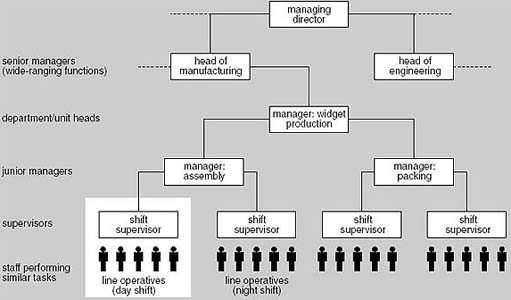

In a traditional org structure , a team leader or department manager would assign tasks and deadlines to employees depending on their skills, function and role. This is a top-down management approach.

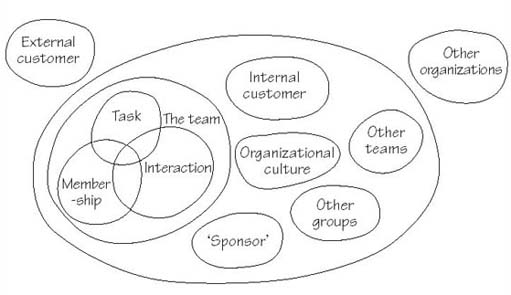

In self-managed teams, a group of people work together toward a common goal, which is defined by stakeholders outside of the team. A manager or department head will define the overall direction and desired outcome, and will provide the required tools, resources, and training if required.

Once the project or program has been kicked off, group members are collectively responsible for self-organizing, assigning tasks, and solving problems. The team, as a whole, decides on the project plan, manages daily activities, and shares management responsibilities.

Self-managed teams are given full ownership and responsibility to drive business results for their specific project. The focus is solely on responsibility and outcome, rather than who is in charge and who gets credit.

Instead of being top-down, self-managed teams operate on a flat or lateral playing field where everyone is given an opportunity to take on leadership over tasks that are relevant to their expertise.

Benefits of self-managed teams

Self-managed teams offer a variety of benefits, depending on your industry, project, and team make up.

Some of these benefits include:

- Increased productivity. Employees are given full ownership over their respective areas of expertise and project outcomes. This helps to boost overall commitment and staff engagement , in turn ramping up productivity for both individual employees and the team as a whole.

- Enhanced innovation. When employees are given complete leeway to solve their own problems and manage their own tasks, innovation and creativity quickly follow. That’s because employees are given direction, and then empowered to find their own way to the desired outcome.

- Reduced pressure on managers. Middle and senior level managers handle most of the burden when it comes to organizing teams, managing projects, and completing administrative and organization tasks. This takes away from their ability to think strategically and make “big picture” decisions. By removing these burdens, and empowering their teams, managers are freed to do more impactful work.

- Creating highly motivated teams. By definition, self-directed teams are highly motivated, engaged , and committed to achieving their target outcome. If they weren’t, then it’s unlikely that team would last very long, or be created in the first place. Highly motivated teams fire on all cylinders, offering maximum impact for key projects.

- Greater ability to respond to complexity. Because self-managed teams engage in collective decision-making, and are laser focussed on a specific project or desired outcome, they have a much stronger ability to process and respond to complex problems.

- Lower overhead and maintenance costs. Cost-savings is a major benefit of self-managed teams, as is realized through the centralizing of all technical and management tasks. Rather than applying expensive management resources to a project team, alongside technical resources, these teams are able to complete all tasks using a self-contained capacity.

- Reduced barriers to work. In a hierarchical team structure, there are often politics, red tape, and time consuming processes that need to be considered by each member of your team. This can productivity and stifle innovation. Self-managed teams are able to be much more agile in how they work, and much quicker to adapt to new problems or opportunities.

Of course, decentralizing management and creating fully autonomous teams does come without its challenges and disadvantages. Let’s look at some of those now.

Disadvantages of self-managed teams

As you can probably guess, the primary challenges associated with self-managed teams related to organization, communication, and focus.

In particular, these can include:

- Short term loss of productivity. Implementing and adapting to a completely new team structure can be difficult, disruptive, and potentially costly in the short term. Time to productivity is likely to be hindered while you work out all of the kinks.

- Differences in work styles. Not all employees are the right fit for self-managed teams. Despite possessing the skills to achieve the desired results, some people just don’t have the personality or desire to operate under these parameters. It can be a challenge to find both highly competent and suitable team members to fill out self-managed teams.

- Lag time in achieving results. Employees on a self-managed team need to develop a strong sense of comradery, commitment to the mission, and self-motivation to achieve the best results. This can take time, meaning there will likely be a lag time between team formation and peak performance.

- Toxic group dynamics. Despite the goal of self-managed teams being to decentralize leadership, there’s always the risk that individuals or cliques within the group end up taking on de facto leadership roles, This, combined with clashing personalities, bullying behavior, idea blocking, and groupthink can all contribute to a toxic group dynamic that stifles productivity and engagement.

- Losing focus. Giving teams complete autonomy always runs the risk of them going too far off the rails, and losing sight of the initial goal. This is especially true if management fails to provide proper guidance and training before the team is formed.

- Training requirements. Because task management is decentralized, you will need to provide training for common manager skills like communication, conflict resolution, time management, and administration. This can be resource intensive at the start, but is imperative to creating and sustaining successful self-managed teams.

Now that we’ve talked about the advantages and disadvantages of self-managed teams, let’s dig deeper into what they look like in practice, and how to create them.

Examples of self-managed teams

As mentioned, self-managed teams have been around since the 1960s. But, they’ve seen a rise in popularity in recent years, and are now actively used in companies like Google, Facebook, Spotify, Zappos, GitHub, Electronic Arts, Valve, and Gore-Tex.

Self-managed teams come in a variety of forms, depending on the nature of your company and project.

Three common examples of self-managed team structures include:

- Fully-autonomous self-managed teams. These teams complete ongoing work, with no top-down supervision, on an indefinite basis. The team is full of cross-trained workers who have a variety of technical and management skills related to the project goals. Fully-autonomous teams take full responsibility over their success and outcomes, and must have a strong commitment to and alignment with company goals.

- Limited supervision teams. These teams work under supervision of a floating manager who will occasionally be called upon to make decisions, offer guidance, and break stalemates. Team members handle the bulk of day-to-day decisions related to the project, but have the added safety net of a supervisor to act as a final decision maker if needed.

- Problem-solving or temporary teams. These teams are formed on a temporary basis to tackle specific problems or to complete special projects. They are time-limited with very tightly defined objectives and outcomes. Unlike ongoing self-managed teams, temporary teams have the added pressure of tight deadlines and a more exact description of what success looks like.

It’s entirely possible that your own self-managed teams will fall into one of these three categories, or be a hybrid. That’s perfectly fine. The key is to find what level of involvement you need from management, and how self-sufficient you can get your teams while still hitting your goals. This will take experimentation and refinement over time.

Related reading: learn how to recruit with no managers and a flat hierarchy

How to create self-managed teams

Self-managed teams are best suited to companies where the organizational culture actively supports autonomy, employee empowerment , and collective decision-making .

If this sounds like your organization, then follow these steps to start creating and experimenting with self-managed teams.

- Define what self-managed teams are before you begin. Do you want to create fully-autonomous teams, limited supervision teams, or problem-solving teams? Or, do you want to create some combination of the three? Before you begin, create a clear mandate and structure of your future self-managed teams to ensure you, and the team, know what is required.

- Determine if your employees are ready to self-manage. Some signs to look for include: being self-driven, trusting each other, confident decision-making, strong communication and time management, ownership over results, and independent learning. Look for individuals who actively display these traits - those are the best candidates for self-managed teams.

- Gauge interest from possible team members. Approach your high-performing employees and present the idea of a self-managed team to them. Take their feedback, and note whether or not this is something they want to participate in. If you have enough interest, then you can move on to forming and enabling your first self-managed team.

- Communicate goals and benefits. Before you form your team, leadership and employees must have a clear understanding of why you are going in this direction, what the expectations will be, and how it will benefit the company. Explain reasoning, benefits, and potential impact of switching to self-managed teams. This should include what it means for individual workers, teams, and departments.

- Provide clear direction. Now that you’ve assembled your self-managed team, you need to make sure that everyone is clear on the desired outcomes from the project, and how they tie into larger organizational goals. Present the expected outcomes and desired impact. Set boundaries and guardrails on the project to keep the team on track. Work with the team to help them create guiding principles for task management and communication.

- Establish decision-making processes. If the self-managed team is brand new, then you’ll want to hold a kick off session that outlines each team member's strengths and their expected contributions to the team. You should also, as a group, determine how decisions will be made, and how conflict or stalemates will be overcome. This shouldn’t be about designating leadership, but rather establishing processes and frameworks that can be used when required.

- Allocate resources. Once you’ve assembled your team, given them direction, and established ground rules, the last step is to provide them with a budget and resources to complete their mandate. Because this is a self-managed team, we recommend that you allocate a lump sum budget for the year or quarter (depending on the duration of the project) and let them determine how best to spend their resources. This gives the team leeway and ownership over their own budget, and will allow them to find innovative and efficient ways to use their resources as needed.

Like with any major shift in management, self-managed teams are an iterative process. It’s unlikely that you will nail this process on the first try, so it will be necessary to keep open lines of communication with your employees to determine opportunities for improvement and refinement.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are self managed teams?

A group of employees that is responsible and accountable for all or most aspects of producing a product, delivering a service, completing a project, or solving a problem. They are self-organized, semi-autonomous, and share a combination of technical and managerial tasks.

What are the advantages of self-managed teams?

Advantages of self-managed teams include: increased productivity, enhanced innovation, reduced pressure on managers, highly motivated employees, greater ability to respond to complexity, lower overhead costs, and reduced barriers to work.

What are the disadvantages of self-managed teams?

Disadvantages of self-managed teams include the potential for: short-term loss of productivity, difference in work styles, lag time in achieving results, toxic group dynamics, losing focus, and significant training requirements.

Brendan is an established writer, content marketer and SEO manager with extensive experience writing about HR tech, information visualization, mind mapping, and all things B2B and SaaS. As a former journalist, he's always looking for new topics and industries to write about and explore.

Get the MidWeekRead

Get the exclusive tips, resources and updates to help you hire better!

Hire better, faster, together!

Bring your hiring teams together, boost your sourcing, automate your hiring, and evaluate candidates effectively.

What Is Self-Management?

- Contact Ciprian Banica

- LinkedIn for Ciprian Banica

This article was first published in the AskScrum.com newsletter. Subscribe to AskScrum.com to be the first to receive articles like this.

Self-management is characterised by autonomy and accountability. It effectively empowers teams to navigate complex challenges by cultivating proactive problem-solving and collaborative decision-making.

Self-managed teams take ownership of their work, collectively driving towards shared goals and business objectives. This behaviour fosters a culture of trust, where the team feels valued and is more engaged, leading to better outcomes where value is delivered to the customer.

1. Autonomy and Accountability:

The team assume shared accountability for their work, with each member contributing to the overall success. Autonomy fosters a sense of ownership, while accountability ensures the team remains aligned with the overall business objectives and the product’s vision and goals.

2. Collaborative Decision Making:

Decisions are made collectively, leveraging the diverse perspectives within the team. This approach ensures that decisions consider various viewpoints, leading to more effective solutions. It acknowledges that not all variables can be controlled or predicted. Flexibility and resilience become critical components in dealing with uncertainties and ambiguities.

3. Adaptive Problem Solving:

Teams adaptively tackle challenges, experimenting and learning from failures. This iterative approach ensures continuous improvement and innovation by exercising flexibility and responsiveness. It involves continuously assessing situations, experimenting with solutions, and learning from outcomes, whether successful or not.

4. Empowerment and Trust:

The team is empowered to take the initiative and make decisions relevant to their work. Trust is central to this culture, enabling team members to work independently while ensuring alignment with the team’s goals and product direction. Effective communication is vital in self-managed teams. Regular interactions and transparent information sharing ensure everyone is on the same page.

Self-management represents a significant shift from traditional management styles. It fosters a proactive, collaborative, and adaptive work environment. This approach enhances efficiency and innovation and contributes to a more fulfilling work experience for everyone in the team.

By embracing self-management, teams are better equipped to navigate the complexities of today's dynamic world. This ultimately drives sustainable success by delivering value to customers and organisations.

© 2024 wowefy.com

What did you think about this post?

Share with your network.

- Share this page via email

- Share this page on Facebook

- Share this page on Twitter

- Share this page on LinkedIn

View the discussion thread.

7.3 Using Teams to Enhance Motivation and Performance

- Why are companies using team-based organizational structures?

One of the most apparent trends in business today is the use of teams to accomplish organizational goals. Using a team-based structure can increase individual and group motivation and performance. This section gives a brief overview of group behavior, defines work teams as specific types of groups, and provides suggestions for creating high-performing teams.

Understanding Group Behavior

Teams are a specific type of organizational group. Every organization contains groups, social units of two or more people who share the same goals and cooperate to achieve those goals. Understanding some fundamental concepts related to group behavior and group processes provides a good foundation for understanding concepts about work teams. Groups can be formal or informal in nature. Formal groups are designated and sanctioned by the organization; their behavior is directed toward accomplishing organizational goals. Informal groups are based on social relationships and are not determined or sanctioned by the organization.

Formal organizational groups, like the sales department at Apple , must operate within the larger Apple organizational system. To some degree, elements of the larger Apple system, such as organizational strategy, company policies and procedures, available resources, and the highly motivated employee corporate culture, determine the behavior of smaller groups, such as the sales department, within the company. Other factors that affect the behavior of organizational groups are individual member characteristics (e.g., ability, training, personality), the roles and norms of group members, and the size and cohesiveness of the group. Norms are the implicit behavioral guidelines of the group, or the standards for acceptable and unacceptable behavior. For example, an Apple sales manager may be expected to work at least two Saturdays per month without extra pay. Although this isn’t written anywhere, it is the expected norm.

Group cohesiveness refers to the degree to which group members want to stay in the group and tend to resist outside influences (such as a change in company policies). When group performance norms are high, group cohesiveness will have a positive impact on productivity. Cohesiveness tends to increase when the size of the group is small, individual and group goals are similar, the group has high status in the organization, rewards are group-based rather than individual-based, and the group competes with other groups within the organization. Work group cohesiveness can benefit the organization in several ways, including increased productivity, enhanced worker self-image because of group success, increased company loyalty, reduced employee turnover, and reduced absenteeism. Southwest Airlines is known for its work group cohesiveness. On the other hand, cohesiveness can also lead to restricted output, resistance to change, and conflict with other work groups in the organization.

The opportunity to turn the decision-making process over to a group with diverse skills and abilities is one of the arguments for using work groups (and teams) in organizational settings. For group decision-making to be most effective, however, both managers and group members must understand its strengths and weaknesses (see Table 7.1 ).

Work Groups versus Work Teams

We have already noted that teams are a special type of organizational group, but we also need to differentiate between work groups and work teams. Work groups share resources and coordinate efforts to help members better perform their individual duties and responsibilities. The performance of the group can be evaluated by adding up the contributions of the individual group members. Work teams require not only coordination but also collaboration, the pooling of knowledge, skills, abilities, and resources in a collective effort to attain a common goal. A work team creates synergy, causing the performance of the team as a whole to be greater than the sum of team members’ individual contributions. Simply assigning employees to groups and labeling them a team does not guarantee a positive outcome. Managers and team members must be committed to creating, developing, and maintaining high-performance work teams. Factors that contribute to their success are discussed later in this section.

Types of Teams

The evolution of the team concept in organizations can be seen in three basic types of work teams: problem-solving, self-managed, and cross-functional. Problem-solving teams are typically made up of employees from the same department or area of expertise and from the same level of the organizational hierarchy. They meet on a regular basis to share information and discuss ways to improve processes and procedures in specific functional areas. Problem-solving teams generate ideas and alternatives and may recommend a specific course of action, but they typically do not make final decisions, allocate resources, or implement change.

Many organizations that experienced success using problem-solving teams were willing to expand the team concept to allow team members greater responsibility in making decisions, implementing solutions, and monitoring outcomes. These highly autonomous groups are called self-managed work teams . They manage themselves without any formal supervision, taking responsibility for setting goals, planning and scheduling work activities, selecting team members, and evaluating team performance.

Today, approximately 80 percent of Fortune 1000 companies use some sort of self-managed teams. 9 One example is Zappos ’s shift to self-managed work teams in 2013, where the traditional organizational structure and bosses were eliminated, according to a system called holacracy. 10 Another version of self-managing teams can be found at W. L. Gore , the company that invented Gore-Tex fabric and Glide dental floss. The three employees who invented Elixir guitar strings contributed their spare time to the effort and persuaded a handful of colleagues to help them improve the design. After working three years entirely on their own—without asking for any supervisory or top management permission or being subjected to any kind of oversight—the team finally sought the support of the larger company, which they needed to take the strings to market. Today, W. L. Gore ’s Elixir is the number one selling string brand for acoustic guitar players. 11

An adaptation of the team concept is called a cross-functional team . These teams are made up of employees from about the same hierarchical level but different functional areas of the organization. Many task forces, organizational committees, and project teams are cross-functional. Often the team members work together only until they solve a given problem or complete a specific project. Cross-functional teams allow people with various levels and areas of expertise to pool their resources, develop new ideas, solve problems, and coordinate complex projects. Both problem-solving teams and self-managed teams may also be cross-functional teams.

Customer Satisfaction and Quality

Team approach flies high at ge aviation.

“Teaming” is the term used at GE Aviation manufacturing plants to describe how self-managed groups of employees are working together to make decisions to help them do their work efficiently, maintain quality, and meet critical deadlines in the global aviation supply chain.

This management concept is not new to GE Aviation; its manufacturing plants in Durham, North Carolina, and Bromont, Quebec, Canada, have been using self-managed teams for more than 30 years. This approach to business operations continues to be successful and is now used at most of its 77 manufacturing facilities worldwide.

The goal of teaming is to move decision-making and authority as close to the end-product as possible, which means front-line employees are accountable for meeting performance goals on a daily basis. For example, if there is some sort of delay in the manufacturing process, it is up to the team to figure out how to keep things moving—even if that means skipping breaks or changing their work schedules to overcome obstacles.

At the Bromont plant, workers do not have supervisors who give them direction. Rather, they have coaches who give them specific goals. The typical functions performed by supervisors, such as planning, developing manufacturing processes, and monitoring vacation and overtime, are managed by the teams themselves. In addition, members from each team sit on a joint council with management and HR representatives to make decisions that will affect overall plant operations, such as when to eliminate overtime and who gets promoted or fired.

This hands-on approach helps workers gain confidence and motivation to fix problems directly rather than sending a question up the chain of command and waiting for a directive. In addition, teaming allows the people who do the work on a daily basis to come up with the best ideas to resolve issues and perform various jobs tasks in the most efficient way possible.

For GE Aviation, implementing the teaming approach has been a successful venture, and the company finds the strategy easiest to implement when starting up a new manufacturing facility. The company recently opened several new plants, and the teaming concept has had an interesting effect on the hiring process. A new plant in Welland, Ontario, Canada, opens soon, and the hiring process, which may seem more rigorous than most job hiring experiences, is well under way. With the team concept in mind, job candidates need to demonstrate not only required technical skills but also soft skills—for example, the ability to communicate clearly, accept feedback, and participate in discussions in a respectful manner.

- What challenges do you think HR recruiters face when hiring job candidates who need to have both technical and soft skills?

- How can experienced team members help new employees be successful in the teaming structure? Provide some examples.

Sources: GE Reports Canada, “The Meaning of Teaming: Empowering New Hires at GE’s Welland Brilliant Factory,” https://gereports.ca, July 17, 2017; Sarah Kessler, “GE Has a Version of Self-Management That Is Much Like Zappos’ Holacracy—and It Works,” Quartz, https://qz.com, June 6, 2017; Gareth Phillips, “Look No Managers! Self-Managed Teams,” LinkedIn, https://www.linkedin.com, June 9, 2016; Amy Alexander, “Step by Step: Train Employees to Take Charge,” Investor’s Business Daily, http://www.investors.com, June 18, 2014; Rasheedah Jones, “Teaming at GE Aviation,” Management Innovation eXchange, http://www.managementexchange.com, July 14, 2013.

Building High-Performance Teams

A great team must possess certain characteristics, so selecting the appropriate employees for the team is vital. Employees who are more willing to work together to accomplish a common goal should be selected, rather than employees who are more interested in their own personal achievement. Team members should also possess a variety of skills. Diverse skills strengthen the overall effectiveness of the team, so teams should consciously recruit members to fill gaps in the collective skill set. To be effective, teams must also have clearly defined goals. Vague or unclear goals will not provide the necessary direction or allow employees to measure their performance against expectations.

Next, high-performing teams need to practice good communication. Team members need to communicate messages and give appropriate feedback that seeks to correct any misunderstandings. Feedback should also be detached; that is, team members should be careful to critique ideas rather than criticize the person who suggests them. Nothing can degrade the effectiveness of a team like personal attacks. Lastly, great teams have great leaders. Skilled team leaders divide work so that tasks are not repeated, help members set and track goals, monitor their team’s performance, communicate openly, and remain flexible to adapt to changing goals or management demands.

Concept Check

- What is the difference between a work team and a work group?

- Identify and describe three types of work teams.

- What are some ways to build a high-performance team?

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-business/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Lawrence J. Gitman, Carl McDaniel, Amit Shah, Monique Reece, Linda Koffel, Bethann Talsma, James C. Hyatt

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Introduction to Business

- Publication date: Sep 19, 2018

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-business/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-business/pages/7-3-using-teams-to-enhance-motivation-and-performance

© Apr 5, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Find Study Materials for

- Explanations

- Business Studies

- Combined Science

- Computer Science

- Engineering

- English literature

- Environmental Science

- Human Geography

- Macroeconomics

- Microeconomics

- Social Studies

- Browse all subjects

- Textbook Solutions

- Read our Magazine

Create Study Materials

- Flashcards Create and find the best flashcards.

- Notes Create notes faster than ever before.

- Study Sets Everything you need for your studies in one place.

- Study Plans Stop procrastinating with our smart planner features.

- Types of Teams

When was the last time you worked as part of a team? Do you think every team you have been a part of follows a similar form? Indeed, there are various types of teams in today's modern business world. And a proper understanding of how different teams operate can benefit companies and organizations worldwide. Keep reading to learn more about the most common types of teams in an organization with examples and explanation of different types of team culture!

Create learning materials about Types of Teams with our free learning app!

- Instand access to millions of learning materials

- Flashcards, notes, mock-exams and more

- Everything you need to ace your exams

- Business Case Studies

- Business Development

- Business Operations

- Change Management

- Corporate Finance

- Financial Performance

- Human Resources

- Influences On Business

- Intermediate Accounting

- Introduction to Business

- Managerial Economics

- Nature of Business

- Operational Management

- Organizational Behavior

- Affective Events Theory

- Attitude in the Workplace

- Behavioral Science

- Big Five Personality Traits

- Biographical Characteristics

- Bureaucratic Structure

- Causes of Stress at Work

- Challenges and Opportunities for OB

- Challenges of Management

- Choosing the Right Communication Channel

- Classification of Groups

- Conflict Results

- Contingent Selection

- Creative Behavior

- Cultural Values

- Decision Making Biases

- Direction of Communication

- Discrimination in the Workplace

- Diversity Management

- Diversity in the Workplace

- Effective Management

- Effective Negotiation

- Effective Teamwork

- Effects of Work Stress

- Emotional Intelligence

- Emotional Labor

- Emotional Regulation

- Employee Involvement

- Employee Selection Methods

- Evidence Based Management

- Factors Influencing Perception

- Functions of Emotions

- Functions of Organizational Culture

- GLOBE Framework

- Group Cohesiveness

- Group Decision Making

- Group Development Stages

- Group Norms

- Group Roles

- Group Status

- Group vs Team

- History of Motivation Theory

- Hofstede's Cultural Dimensions

- How to Measure Job Satisfaction

- Impact of Power

- Importance of Leadership in Human Resource Management

- Influences on Organizational Culture

- Initial Selection Process

- Innovative Organizational Culture

- Integrating Theories of Motivation

- Interpersonal Skills

- Job Attitude

- Job Dissatisfaction

- Job Satisfaction Causes

- Job Satisfaction Outcomes

- Leadership Trust

- Maintaining Organizational Culture

- Mechanistic vs Organic Structure

- Models of Organizational Behavior

- Modern Motivational Theory

- Myers-Briggs

- Negotiation Process

- Organizational Behavior Management

- Organizational Constraints

- Organizational Culture Problems

- Organizational Decision Making

- Organizational Structure Management

- Organizational Values

- Paradox Theory

- Perception in Decision Making

- Personal Stress Management

- Personality Models

- Personality and Values

- Personality at Work

- Planned Change in an Organization

- Positive Company Culture

- Power Tactics

- Power in Work

- Responsible Leaders

- Self-Evaluation

- Simple Structure

- Situation Strength Theory

- Social Loafing

- Stereotype Threat

- Stress Management in Organization

- Stress in the Workplace

- Substantive Selection

- Team Challenge

- Team Composition

- Team Player

- Team Process

- The Study of Organizational Behavior

- Third Party Negotiation

- Training Effectiveness

- Trait Activation Theory

- Types of Diversity

- Types of Emotions

- Types of Moods

- Types of Power in the Workplace

- Understanding and Developing Organizational Culture

- Unequal Power

- Virtual Organizational Structure

- Work Emotions

- Working as a Team

- Workplace Behavior

- Workplace Spirituality

- Organizational Communication

- Strategic Analysis

- Strategic Direction

Great things in business are never done by one person. They're done by a team of people.

- Steve Jobs 1

Types of Teams in Management

Perhaps you are currently a part of a team. Whether it is a team at your university, a sports team in your local town, or a team working on your company's latest project, exploring different types of teams can help better understand your team's current type and characteristics. First, perhaps let's walk through a brief definition of a team.

- A team consists of individuals collaborating on specific tasks to achieve common goals and objectives.

Everyone knows about the great importance and tremendous benefits of teamwork towards the success of any business, which ranges from better communication and united vision and mission to better cohesion and enhanced trust.

Each individual has unique gifts, and talents and skills. When we bring them to the table and share them for a common purpose, it can give companies a real competitive advantage.

- John J. Murphy 3

Accordingly, not everyone knows how to work as a team. Thus, studying different types of teams, together with their unique characteristics and advantages and disadvantages, can assist individuals in improving their teamwork skills and understanding. So, how many types of teams are there nowadays?

Types of Teams in an Organization

There are various types of teams in an organization.

Yet, the five most popular types of teams in an organization include: problem-solving teams, self-managed teams, cross-functional teams, virtual teams, and the multiteam system (team of teams). 2

Problem-Solving Team

Often, problem-solving teams are assembled temporarily. Usually, team members in problem-solving teams are gathered in case of a crisis or an unplanned matter at work. Thus, such teams try to address the issue and drive the organizations out of the ongoing crisis.

A problem-solving team consists of 5-10 members from the same department. The team will have a number of weekly meetings to resolve specific business problems.

In fact, this type of team can alleviate possible risks associated with certain crises while developing thorough solutions that address multiple business segments.

What are possible crises that concern problem-solving teams?

Problem-solving teams can work to alleviate possible risks in crises such as the global financial crisis in 2008-2009, the ongoing impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic, the currently increasing inflation rates across countries, and so on.

Self-Managed Work Team

Unlike problem-solving teams, of which desirable outcomes focus on recommendations, self-managed work teams are more concerned about implementing and revising solutions.

A self-managed work team consists of a small group of members who are fully responsible for delivering a product or a service through peer collaboration. In this type of team, a manager's guidance is often absent.

Normally, around ten employees will take on supervisory responsibilities while performing interdependent tasks. Together, this type of team unites for long-term purposes.

What are the responsibilities of a self-managed work team?

In this team, members often perform tasks ranging from work scheduling and operational planning to working with customers and assisting operational decision-making processes.

Cross-Functional Team

Nowadays, more and more organizations have embraced the use of cross-functional teams in their operations.

A cross-functional team consists of members on the same hierarchical level but from various departments within an organization.

Despite its growing importance, about 75 percent of global cross-functional teams face dysfunctional challenges. 4 To illustrate, while cross-functional teams gather people from different areas of expertise to coordinate complex projects, such teams are tough to manage due to leadership ambiguity. Further, such diversity in team members also entails a high risk of workplace conflicts.

What are the advantages of cross-functional teams?

Cross-functional teams entail various benefits for companies, among which the following three advantages are most prominent:

- Cross-functional teams accelerate task completion.

- With their skillful and diverse members, cross-functional teams can tackle various projects at hand.

- Cross-functional teams are dynamic and creative in producing innovative ideas.

Virtual Team

Virtual teams have recently arisen as new global group dynamic trends. Also known as geographically dispersed or remote teams, virtual teams imply people working together without being physically present.

A virtual team relies on digital technology to unite virtual members to work towards common goals.

Accordingly, virtual teams' most significant advantage is that they can stay connected and informed anywhere and at any time, regardless of their physical locations.

70 percent of professionals work remotely in some capacity at least once a week, with 53% doing so for half the week.

- Ariel Lopez 5

More interestingly, virtual teams are often more engaged than physical ones. 5 The reason is that working in the same office can decrease team satisfaction when individuals fear or worry about their leaders. Thus, the physical absence of leaders in virtual teams encourages members to connect more.

Multiteam System

If you are wondering about a team that can unite different departments within your organization, not just the individuals, perhaps a multiteam system is ideal for you.

A multiteam system is a team that consists of different teams working together to realize overarching goals.

The multiteam system is quite a new concept for organizations worldwide. While a multiteam system is larger than a team, it is still smaller than an organization. Organizations often need to form multiteam systems to resolve highly complex tasks requiring higher coordination and expertise.

The role of leadership in a multiteam system

When it comes to a multiteam system, leadership is extremely challenging. Researchers have highlighted the importance of functional leadership theory in conceptualizing an appropriate role for team leaders in a multiteam system. Accordingly, this theory centers on the ability of leaders to build and maintain relationships on a broad level. Thus, leaders under this theory take the core responsibility "to do, or get done, whatever is not being adequately handled for group needs." 8

Examples of Teams Types

What do different types of teams look like in real-life contexts? Let's then go through some real-life examples of the different types of teams.

Table 1 - Types of Teams and Examples

Common Types of Formal Teams

Besides common types of teams divided based on their functions and scale, teams in organizations can also be classified into two types of teams: formal and informal. However, within professional business contexts, formal types of teams are of greater importance within professional business contexts.

A formal team is a group of individuals formed by the management team in an organizational structure to accomplish specific tasks and goals. 6

In this explanation, we will introduce to you some popular types of formal teams at work:

Table 2 - Common Types of Formal Teams

Types of Team Culture

When it comes to group dynamics, there are also various types of team cultures that shape the unique characteristics and spirits of teams. Within business contexts, types of team culture are mainly defined by the extent to which leaders and team members value productivity, people, and relationships at work.

In general, there are six different types of team culture, which are most popular in workplaces.

Table 3 - Types of Team Culture

Indeed, people make regular use of team concepts and group dynamics in their daily life. Thus, a proper understanding of different types of teams can make the procedure of team development more approachable and comfortable.

If everyone is moving forward together, then success takes care of itself.

- Henry Ford 7

Types of Teams - Key takeaways

- The five most popular types of teams in an organization include problem-solving teams, self-managed work teams, cross-functional teams, virtual teams, and multiteam systems.

- A formal team is a group of individuals formed by the management team in an organizational structure to accomplish specific tasks and goals.

- There are six popular types of team culture at work: corrosive culture, country club culture, comfortable culture, competitive culture, cut-throat culture, and championship culture.

- Sean Peek. Steve Jobs Biography. 2022. https://www.businessnewsdaily.com/4195-business-profile-steve-jobs.html

- Robbins Stephen and Timothy Judge. Organizational Behaviors. Pearson. 2014.

- Luna Mampaey. 10 benefits of great teamwork. 2022. https://herculeanalliance.com/2022/03/01/10-benefits-of-great-teamwork/.

- Tracy Middleton. The importance of teamwork (as proven by science). 2022. https://www.atlassian.com/blog/teamwork/the-importance-of-teamwork.

- Ariel Lopez. What Is a Virtual Team? Definition & Examples. 2020. https://www.projectmanager.com/blog/what-is-a-virtual-team

- Hitesh Bhasin. What Is A Formal Team And Types Of Formal Teams?. 2019. https://www.marketing91.com/formal-team-types-formal-teams/.

- Fred Wilson.The 113 Best Teamwork Quotes to Inspire Collaboration & Motivation. 2020. https://www.ntaskmanager.com/blog/best-teamwork-quotes/.

- Stephen J. Zaccaroa, Andrea L. Rittmana & Michelle A. Marksb. Team leadership. 2001. https://www.qub.ac.uk/elearning/media/Media,264498,en.pdf

Flashcards in Types of Teams 15

Great things in business are never done by ____ person.

A team consists of a group of individuals collaborating on specific tasks to achieve ____ goals and objectives.

Fill in the Blank:

Each individual has unique gifts, and talents and skills. When we bring them to the table and share them for a common purpose, it can give companies a real ____ advantage.

Competitive.

How many popular types of teams in an organization are there?

Often, problem-solving teams are assembled _________.

Temporarily.

Self-managed work teams are more concerned about:

The implementation of solutions.