- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- When and how to update...

When and how to update systematic reviews: consensus and checklist

- Related content

Peer review

This article has a correction. please see:.

- Errata - September 06, 2016

- Paul Garner , professor 1 ,

- Sally Hopewell , associate professor 2 ,

- Jackie Chandler , methods coordinator 3 ,

- Harriet MacLehose , senior editor 3 ,

- Elie A Akl , professor 5 6 ,

- Joseph Beyene , associate professor 7 ,

- Stephanie Chang , director 8 ,

- Rachel Churchill , professor 9 ,

- Karin Dearness , managing editor 10 ,

- Gordon Guyatt , professor 4 ,

- Carol Lefebvre , information consultant 11 ,

- Beth Liles , methodologist 12 ,

- Rachel Marshall , editor 3 ,

- Laura Martínez García , researcher 13 ,

- Chris Mavergames , head 14 ,

- Mona Nasser , clinical lecturer in evidence based dentistry 15 ,

- Amir Qaseem , vice president and chair 16 17 ,

- Margaret Sampson , librarian 18 ,

- Karla Soares-Weiser , deputy editor in chief 3 ,

- Yemisi Takwoingi , senior research fellow in medical statistics 19 ,

- Lehana Thabane , director and professor 4 20 ,

- Marialena Trivella , statistician 21 ,

- Peter Tugwell , professor of medicine, epidemiology, and community medicine 22 ,

- Emma Welsh , managing editor 23 ,

- Ed C Wilson , senior research associate in health economics 24 ,

- Holger J Schünemann , professor 4 5

- 1 Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group, Department of Clinical Sciences, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, Liverpool L3 5QA, UK

- 2 Oxford Clinical Trials Research Unit, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

- 3 Cochrane Editorial Unit, Cochrane Central Executive, London, UK

- 4 Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics and Department of Medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada

- 5 Cochrane GRADEing Methods Group, Ottawa, ON, Canada

- 6 Department of Internal Medicine, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon

- 7 Department of Mathematics and Statistics, McMaster University

- 8 Evidence-based Practice Center Program, Agency for Healthcare and Research Quality, Rockville, MD, USA

- 9 Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York, York, UK

- 10 Cochrane Upper Gastrointestinal and Pancreatic Diseases Group, Hamilton, ON, Canada

- 11 Lefebvre Associates, Oxford, UK

- 12 Kaiser Permanente National Guideline Program, Portland, OR, USA

- 13 Iberoamerican Cochrane Centre, Barcelona, Spain

- 14 Cochrane Informatics and Knowledge Management, Cochrane Central Executive, Freiburg, Germany

- 15 Plymouth University Peninsula School of Dentistry, Plymouth, UK

- 16 Department of Clinical Policy, American College of Physicians, Philadelphia, PA, USA

- 17 Guidelines International Network, Pitlochry, UK

- 18 Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa, ON, Canada

- 19 Institute of Applied Health Research, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK

- 20 Biostatistics Unit, Centre for Evaluation, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada

- 21 Centre for Statistics in Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

- 22 University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada

- 23 Cochrane Airways Group, Population Health Research Institute, St George’s, University of London, London, UK

- 24 Cambridge Centre for Health Services Research, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK

- Correspondence to: P Garner Paul.Garner{at}lstmed.ac.uk

- Accepted 26 May 2016

Updating of systematic reviews is generally more efficient than starting all over again when new evidence emerges, but to date there has been no clear guidance on how to do this. This guidance helps authors of systematic reviews, commissioners, and editors decide when to update a systematic review, and then how to go about updating the review.

Systematic reviews synthesise relevant research around a particular question. Preparing a systematic review is time and resource consuming, and provides a snapshot of knowledge at the time of incorporation of data from studies identified during the latest search. Newly identified studies can change the conclusion of a review. If they have not been included, this threatens the validity of the review, and, at worst, means the review could mislead. For patients and other healthcare consumers, this means that care and policy development might not be fully informed by the latest research; furthermore, researchers could be misled and carry out research in areas where no further research is actually needed. 1 Thus, there are clear benefits to updating reviews, rather than duplicating the entire process as new evidence emerges or new methods develop. Indeed, there is probably added value to updating a review, because this will include taking into account comments and criticisms, and adoption of new methods in an iterative process. 2 3 4 5 6

Cochrane has over 20 years of experience with preparing and updating systematic reviews, with the publication of over 6000 systematic reviews. However, Cochrane’s principle of keeping all reviews up to date has not been possible, and the organisation has had to adapt: from updating when new evidence becomes available, 7 to updating every two years, 8 to updating based on need and priority. 9 This experience has shown that it is not possible, sensible, or feasible to continually update all reviews all the time. Other groups, including guideline developers and journal editors, adopt updating principles (as applied, for example, by the Systematic Reviews journal; https://systematicreviewsjournal.biomedcentral.com/ ).

The panel for updating guidance for systematic reviews (PUGs) group met to draw together experiences and identify a common approach. The PUGs guidance can help individuals or academic teams working outside of a commissioning agency or Cochrane, who are considering writing a systematic review for a journal or to prepare for a research project. The guidance could also help these groups decide whether their effort is worthwhile.

Summary points

Updating systematic reviews is, in general, more efficient than starting afresh when new evidence emerges. The panel for updating guidance for systematic reviews (PUGs; comprising review authors, editors, statisticians, information specialists, related methodologists, and guideline developers) met to develop guidance for people considering updating systematic reviews. The panel proposed the following:

Decisions about whether and when to update a systematic review are judgments made for individual reviews at a particular time. These decisions can be made by agencies responsible for systematic review portfolios, journal editors with systematic review update services, or author teams considering embarking on an update of a review.

The decision needs to take into account whether the review addresses a current question, uses valid methods, and is well conducted; and whether there are new relevant methods, new studies, or new information on existing included studies. Given this information, the agency, editors, or authors need to judge whether the update will influence the review findings or credibility sufficiently to justify the effort in updating it.

Review authors and commissioners can use a decision framework and checklist to navigate and report these decisions with “update status” and rationale for this status. The panel noted that the incorporation of new synthesis methods (such as Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE)) is also often likely to improve the quality of the analysis and the clarity of the findings.

Given a decision to update, the process needs to start with an appraisal and revision of the background, question, inclusion criteria, and methods of the existing review.

Search strategies should be refined, taking into account changes in the question or inclusion criteria. An analysis of yield from the previous edition, in relation to databases searched, terms, and languages can make searches more specific and efficient.

In many instances, an update represents a new edition of the review, and authorship of the new version needs to follow criteria of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE). New approaches to publishing licences could help new authors build on and re-use the previous edition while giving appropriate credit to the previous authors.

The panel also reflected on this guidance in the context of emerging technological advances in software, information retrieval, and electronic linkage and mining. With good synthesis and technology partnerships, these advances could revolutionise the efficiency of updating in the coming years.

Panel selection and procedures

An international panel of authors, editors, clinicians, statisticians, information specialists, other methodologists, and guideline developers was invited to a two day workshop at McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada, on 26-27 June 2014, organised by Cochrane. The organising committee selected the panel (web appendix 1). The organising committee invited participants, put forward the agenda, collected background materials and literature, and drafted the structure of the report.

The purpose of the workshop was to develop a common approach to updating systematic reviews, drawing on existing strategies, research, and experience of people working in this area. The selection of participants aimed on broad representation of different groups involved in producing systematic reviews (including authors, editors, statisticians, information specialists, and other methodologists), and those using the reviews (guideline developers and clinicians). Participants within these groups were selected on their expertise and experience in updating, in previous work developing methods to assess reviews, and because some were recognised for developing approaches within organisations to manage updating strategically. We sought to identify general approaches in this area, and not be specific to Cochrane; although inevitably most of the panel were somehow engaged in Cochrane.

The workshop structure followed a series of short presentations addressing key questions on whether, when, and how to update systematic reviews. The proceedings included the management of authorship and editorial decisions, and innovative and technological approaches. A series of small group discussions followed each question, deliberating content, and forming recommendations, as well as recognising uncertainties. Large group, round table discussions deliberated further these small group developments. Recommendations were presented to an invited forum of individuals with varying levels of expertise in systematic reviews from McMaster University (of over 40 people), widely known for its contributions to the field of research evidence synthesis. Their comments helped inform the emerging guidance.

The organising committee became the writing committee after the meeting. They developed the guidance arising from the meeting, developed the checklist and diagrams, added examples, and finalised the manuscript. The guidance was circulated to the larger group three times, with the PUGs panel providing extensive feedback. This feedback was all considered and carefully addressed by the writing committee. The writing committee provided the panel with the option of expressing any additional comments from the general or specific guidance in the report, and the option for registering their own view that might differ to the guidance formed and their view would be recorded in an annex. In the event, consensus was reached, and the annex was not required.

Definition of update

The PUGs panel defined an update of a systematic review as a new edition of a published systematic review with changes that can include new data, new methods, or new analyses to the previous edition. This expands on a previous definition of a systematic review update. 10 An update asks a similar question with regard to the participants, intervention, comparisons, and outcomes (PICO) and has similar objectives; thus it has similar inclusion criteria. These inclusion criteria can be modified in the light of developments within the topic area with new interventions, new standards, and new approaches. Updates will include a new search for potentially relevant studies and incorporate any eligible studies or data; and adjust the findings and conclusions as appropriate. Box 1 provides some examples.

Box 1: Examples of what factors might change in an updated systematic review

A systematic review of steroid treatment in tuberculosis meningitis used GRADE methods and split the composite outcome in the original review of death plus disability into its two components. This improved the clarity of the reviews findings in relation to the effects and the importance of the effects of steroids on death and on disability. 11

A systematic review of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine (DHAP) for treating malaria was updated with much more detailed analysis of the adverse effect data from the existing trials as a result of questions raised by the European Medicines Agency. Because the original review included other comparisons, the update required extracting only the DHAP comparisons from the original review, and a modification of the title and the PICO. 12

A systematic review of atorvastatin was updated with simple uncontrolled studies. 13 This update allowed comparisons with trials and strengthened the review findings. 14

Which systematic reviews should be updated and when?

Any group maintaining a portfolio of systematic reviews as part of their normative work, such as guidelines panels or Cochrane review groups, will need to prioritise which reviews to update. Box 2 presents the approaches used by the Agency for HealthCare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and Cochrane to prioritise which systematic reviews to update and when. Clearly, the responsibility for deciding which systematic reviews should be updated and when they will be updated will vary: it may be centrally organised and resourced, as with the AHRQ scientific resource centre (box 2). In Cochrane, the decision making process is decentralised to the Cochrane Review Group editorial team, with different approaches applied, often informally.

Box 2: Examples of how different organisations decide on updating systematic reviews

Agency for healthcare research and quality (us).

The AHRQ uses a needs based approach; updating systematic reviews depends on an assessment of several criteria:

Stakeholder impact

Interest from stakeholder partners (such as consumers, funders, guideline developers, clinical societies, James Lind Alliance)

Use and uptake (for example, frequency of citations and downloads)

Citation in scientific literature including clinical practice guidelines

Currency and need for update

New research is available

Review conclusions are probably dated

Update decision

Based on the above criteria, the decision is made to either update, archive, or continue surveillance.

Of over 50 Cochrane editorial teams, most but not all have some systems for updating, although this process can be informal and loosely applied. Most editorial teams draw on some or all of the following criteria:

Strategic importance

Is the topic a priority area (for example, in current debates or considered by guidelines groups)?

Is there important new information available?

Practicalities in organising the update that many groups take into account

Size of the task (size and quality of the review, and how many new studies or analyses are needed)

Availability and willingness of the author team

Impact of update

New research impact on findings and credibility

Consider whether new methods will improve review quality

Priority to update, postpone update, class review as no longer requiring an update

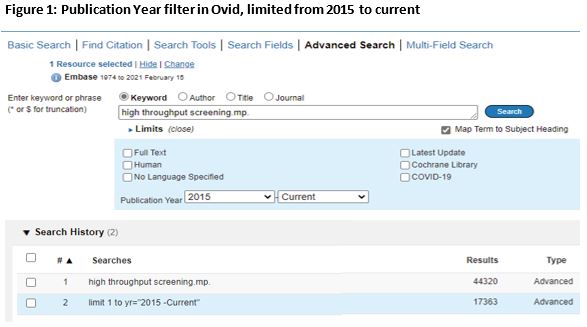

The PUGs panel recommended an individualised approach to updating, which used the procedures summarised in figure 1 ⇓ . The figure provides a status category, and some options for classifying reviews into each of these categories, and builds on a previous decision tool and earlier work developing an updating classification system. 15 16 We provide a narrative for each step.

Fig 1 Decision framework to assess systematic reviews for updating, with standard terms to report such decisions

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Step 1: assess currency

Does the published review still address a current question.

An update is only worthwhile if the question is topical for decision making for practice, policy, or research priorities (fig 1 ⇑ ). For agencies, people responsible for managing a portfolio of systematic reviews, there is a need to use both formal and informal horizon scanning. This type of scanning helps identify questions with currency, and can help identify those reviews that should be updated. The process could include monitoring policy debates around the review, media outlets, scientific (and professional) publications, and linking with guideline developers.

Has the review had good access or use?

Metrics for citations, article access and downloads, and sharing via social or traditional media can be used as proxy or indicators for currency and relevance of the review. Reviews that are widely cited and used could be important to update should the need arise. Comparable reviews that are never cited or rarely downloaded, for example, could indicate that they are not addressing a question that is valued, and might not be worth updating.

In most cases, updated reviews are most useful to stakeholders when there is new information or methods that result in a change in findings. However, there are some circumstances in which an up to date search for information is important for retaining the credibility of the review, regardless of whether the main findings would change or not. For example, key stakeholders would dismiss a review if a study is carried out in a relevant geographical setting but is not included; if a large, high profile study that might not change the findings is not included; or if an up to date search is required for a guideline to achieve credibility. Box 3 provides such examples. If the review does not answer a current question, the intervention has been superseded, then a decision can be made not to update and no further intelligence gathering is required (fig 1 ⇑ ).

Box 3: Examples of a systematic review’s currency

The public is interested in vitamin C for preventing the common cold: the Cochrane review includes over 29 trials with either no or small effects, concluding good evidence of no important effects. 17 Assessment: still a current question for the public.

Low osmolarity oral rehydration salt (ORS) solution versus standard solution for acute diarrhoea in children: the 2001 Cochrane review 18 led the World Health Organization to recommend ORS solution formula worldwide to follow the new ORS solution formula 19 and this has now been accepted globally. Assessment: no longer a current question.

Routine prophylactic antibiotics with caesarean section: the Cochrane review reports clear evidence of maternal benefit from placebo controlled trials but no information on the effects on the baby. 20 Assessment: this is a current question.

A systematic review published in the Lancet examined the effects of artemisinin based combination treatments compared with monotherapy for treating malaria and showed clear benefit. 21 Assessment: this established the treatment globally and is no longer a current question and no update is required.

A Cochrane review of amalgam restorations for dental caries 22 is unlikely to be updated because the use of dental amalgam is declining, and the question is not seen as being important by many dental specialists. Assessment: no longer a current question.

Did the review use valid methods and was it well conducted?

If the question is current and clearly defined, the systematic review needs to have used valid methods and be well conducted. If the review has vague inclusion criteria, poorly articulated outcomes, or inappropriate methods, then updating should not proceed. If the question is current, and the review has been cited or used, then it might be appropriate to simply start with a new protocol. The appraisal should take into account the methods in use when the review was done.

Step 2: identify relevant new methods, studies, and other information

Are there any new relevant methods.

If the question is current, but the review was done some years ago, the quality of the review might not meet current day standards. Methods have advanced quickly, and data extraction and understanding of the review process have become more sophisticated. For example:

Methods for assessing risk of bias of randomised trials, 23 diagnostic test accuracy (QUADAS-2), 24 and observational studies (ROBINS-1). 25

Application of summary of findings, evidence profiles, and related GRADE methods has meant the characteristics of the intervention, characteristics of the participants, and risk of bias are more thoroughly and systematically documented. 26 27

Integration of other study designs containing evidence, such economic evaluation and qualitative research. 28

There are other incremental improvements in a wide range of statistical and methodological areas, for example, in describing and taking into account cluster randomised trials. 29 AMSTAR can assess the overall quality of a systematic review, 30 and the ROBIS tool can provide a more detailed assessment of the potential for bias. 31

Are there any new studies or other information?

If an authoring or commissioning team wants to ensure that a particular review is up to date, there is a need for routine surveillance for new studies that are potentially relevant to the review, by searching and trial register inspection at regular intervals. This process has several approaches, including:

Formal surveillance searching 32

Updating the full search strategies in the original review and running the searches

Tracking studies in clinical trial and other registers

Using literature appraisal services 33

Using a defined abbreviated search strategy for the update 34

Checking studies included in related systematic reviews. 35

How often this surveillance is done, and which approaches to use, depend on the circumstances and the topic. Some topics move quickly, and the definition of “regular intervals” will vary according to the field and according to the state of evidence in the field. For example, early in the life of a new intervention, there might be a plethora of studies, and surveillance would be needed more frequently.

Step 3: assess the effect of updating the review

Will the adoption of new methods change the findings or credibility.

Editors, referees, or experts in the topic area or methodologists can provide an informed view of whether a review can be substantially improved by application of current methodological expectations and new methods (fig 1 ⇑ ). For example, a Cochrane review of iron supplementation in malaria concluded that there was “no significant difference between iron and placebo detected.” 36 An update of the review included a GRADE assessment of the certainty of the evidence, and was able to conclude with a high degree of certainty that iron does not cause an excess of clinical malaria because the upper relative risk confidence intervals of harm was 1.0 with high certainty of evidence. 37

Will the new studies, information, or data change the findings or credibility?

The assessment of new data contained in new studies and how these data might change the review is often used to determine whether an update should go ahead, and the speed with which the update should be conducted. The appraisal of these new data can be carried out in different ways. Initially, methods focused on statistical approaches to predict an overturning of the current review findings in terms of the primary or desired outcome (table 1 ⇓ ). Although this aspect is important, additional studies can add important information to a review, which is more than just changing the primary outcome to a more accurate and reliable estimate. Box 4 gives examples.

Formal prediction tools: how potentially relevant new studies can affect review conclusions

- View inline

Box 4: Examples of new information other than new trials being important

The iconic Cochrane review of steroids in preterm labour was thought to provide evidence of benefit in infants, and this question no longer required new trials. However, a new large trial published in the Lancet in 2015 showed that in low and middle income countries, strategies to promote the uptake of neonatal steroids increased neonatal mortality and suspected maternal infection. 49 This information needs to somehow be incorporated into the review to maintain its credibility.

A Cochrane review of community deworming in developing countries indicates that in recent studies, there is little or no effect. 50 The inclusion of a large trial of two million children confirmed that there was no effect on mortality. Although the incorporation of the trial in the review did not change the review’s conclusions, the trial’s absence would have affected the credibility of the review, so it was therefore updated.

A new paper reporting long term follow-up data on anthracycline chemotherapy as part of cancer treatment was published. Although the effects from the outcomes remained essentially unchanged, apart from this longer follow-up, the paper also included information about the performance bias in the original trial, shifting the risk of bias for several outcomes from “unknown” to “high” in the Cochrane review. 51

Reviews with a high level of certainty in the results (that is, when the GRADE assessment for the body of evidence is high) are less likely to change even with the addition of new studies, information, or data, by definition. GRADE can help guide priorities in whether to update, but it is still important to assess new studies that might meet the inclusion criteria. New studies can show unexpected effects (eg, attenuation of efficacy) or provide new information about the effects seen in different circumstances (eg, groups of patients or locations).

Other tools are specifically designed to help decision making in updating. For example, the Ottawa 39 and RAND 45 methods focus on identification of new evidence, the statistical predication tool 15 calculates the probability of new evidence changing the review conclusion, and the value of information analysis approach 52 calculates the expected health gain (table 1 ⇑ ). As yet, there has been limited external validation of these tools to determine which approach would be most effective and when.

If potentially relevant studies are identified that have not previously been assessed for inclusion, authors or those managing the updating process need to assess whether including them might affect the conclusions of the review. They need to examine the weight and certainty of the new evidence to help determine whether an update is needed and how urgent that update is. The updating team can assess this informally by judging whether new studies or data are likely to substantively affect the review, for example, by altering the certainty in an existing comparison, or by generating new comparisons and analyses in the existing review.

New information can also include fresh follow-up data on existing included studies, or information on how the studies were carried out. These should be assessed in terms of whether they might change the review findings or improve its credibility (fig 1 ⇑ ). Indeed, if any study has been retracted, it is important the authors assess the reasons for its retraction. In the case of data fabrication, the study needs to be removed from the analysis and this recorded. A decision needs to be made as to whether other studies by the same author should be removed from the review and other related reviews. An investigation should also be initiated following guidelines from the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE). Additional published and unpublished data can become available from a wide range of sources—including study investigators, regulatory agencies and industry—and are important to consider.

Preparing for an update

Refresh background, objectives, inclusion criteria, and methods

Before including new studies in the review, authors need to revisit the background, objectives, inclusion criteria, and methods of the current review. In Cochrane, this is referred to as the protocol, and editors are part of this process. The update could range from simply endorsing the current question and inclusion criteria, through to full rewriting of the question, inclusion criteria and methods, and republishing the protocol. As a field progresses with larger and better quality trials rigorously testing the questions posed, it may be appropriate to exclude weaker study designs (such as quasi-randomised comparisons or very small trials) from the update (table 2 ⇓ ). The PUGs panel recommended that a protocol refresh will require the authors to use the latest accepted methods of synthesis, even if this means repeating data extraction for all studies.

New authors and authorship

Updated systematic reviews are new publications with new citations. An authorship team publishing an update in a scientific or medical journal is likely to manage the new edition of a review in the same way as with any other publication, and follow the ICMJE authorship criteria. 56 If the previous author or author team steps down, then they should be acknowledged in the new version. However, some might perceive that their efforts in the first version warrant continued authorship, which may be valid. The management of authorship between versions can sometimes be complicated. At worst, it delays new authors completing an update and leads to long authorship lists of people from previous versions who probably do not meet ICMJE authorship criteria. One approach with updates including new authors is to have an opt-in policy for the existing authors: they can opt in to the new edition, provided that they make clear their contribution, and this is then agreed with the entire author team.

Although they are new publications, updates will generally include content from the published version. Changing licensing rights around systematic reviews to allow new authors of future updates to remix, tweak, or build on the contributions of the original authors of the published version (similar to the rights available via a Creative Commons licence; https://creativecommons.org ) could be a more sustainable and simpler approach. This approach would allow systematic reviews to continue to evolve and build on the work of a range of authors over time, and for contributors to be given credit for contributions to this previous work.

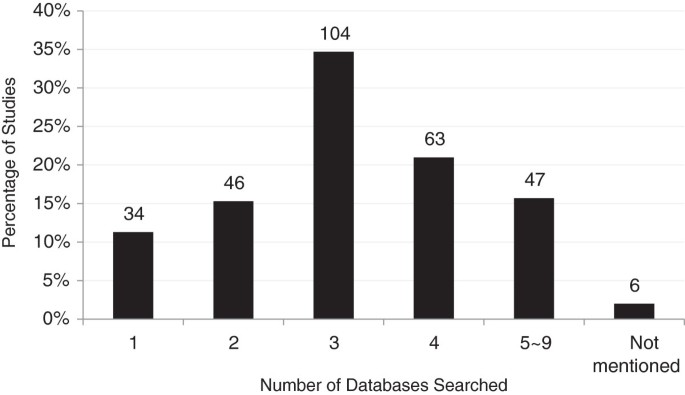

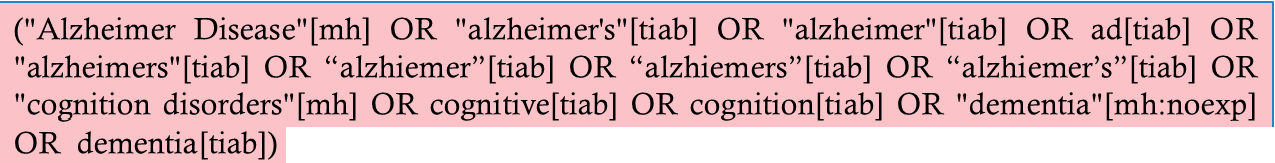

Efficient searching

In performing an update, a search based on the search conducted for the original review is required. The updated search strategy will need to take into account changes in the review question or inclusion criteria, for example, and might be further adjusted based on knowledge of running the original search strategy. The search strategy for an update need not replicate the original search strategy, but could be refined, for example, based on an analysis of the yield of the original search. These new search approaches are currently undergoing formal empirical evaluation, but they may well provide much more efficient search strategies in the future. Some examples of these possible new methods for review updates are described in web appendix 2.

In reporting the search process for the update, investigators must ensure transparency for any previous versions and the current update, and use an adapted flow diagram based on PRISMA reporting (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses). 57 The search processes and strategies for the update must be adequately reported such that they could be replicated.

Systematic reviews published for the first time in peer reviewed journals are by definition peer reviewed, but practice for updates remains variable, because an update might have few changes (such as an updated search but no new studies found and therefore included) or many changes (such as revise methods and inclusion of several new studies leading to revised conclusions). Therefore, and to use peer reviewers’ time most effectively, editors need to consider when to peer review an update and the type of peer reviewer most useful for a particular update (for example, topic specialist, methodologist). The decision to use peer review, and the number and expertise of the peer reviewers could depend on the nature of the update and the extent of any changes to the systematic review as part of an editor assessment. A change in the date of the search only (where no new studies were identified) would not require peer review (except, arguably, peer review of the search), but the addition of studies that lead to a change in conclusions or significant changes to the methods would require peer review. The nature of the peer review could be described within the published article.

Reporting changes

Authors should provide a clear description of the changes in approach or methods between different editions of a review. Also, authors need to report the differences in findings between the original and updated edition to help users decide how to use the new edition. The approach or format used to present the differences in findings might vary with the target user group. 58 Publishers need to ensure that all previous versions of the review remain publically accessible.

Updates can range from small adjustments to reviews being completely rewritten, and the PUGs panel spent some time debating whether the term “new edition” would be a better description than “update.” However, the word “update” is now in common parlance and changing the term, the panel judged, could cause confusion. However, the debate does illustrate that an update could represent a review that asks a similar question but has been completely revised.

Technology and innovation

The updating of systematic review is generally done manually and is time consuming. There are opportunities to make better use of technology to streamline the updating process and improve efficiency (table 3 ⇓ ). Some of these tools already exist and are in development or in early use, and some are commercially available or freely available. The AHRQ’s evidence based practice centre team has recently published tools for searching and screening, and will provide an assessment of the use, reliability, and availability of these tools. 63

Technological innovations to improve the efficiency of updating systematic reviews

Other developments, such as targeted updates that are performed rapidly and focus on updating only key components of a review, could provide different approaches to updating in the future and are being piloted and evaluated. 64 With implementation of these various innovations, the longer term goal is for “living” systematic reviews, which identify and incorporate information rapidly as it evolves over time. 60

Concluding remarks

Updating systematic reviews, rather than addressing the same question with a fresh protocol, is generally more efficient and allows incremental improvement over time. Mechanical rules appear unworkable, but there is no clear unified approach on when to update, and how implement this. This PUGs panel of authors, editors, statisticians, information specialists, other methodologists, and guideline developers brought together current thinking and experience in this area to provide guidance.

Decisions about whether and when to update a systematic review are judgments made at a point in time. They depend on the currency of the question asked, the need for updating to maintain credibility, the availability of new evidence, and whether new research or new methods will affect the findings.

Whether the review uses current methodological standards is important in deciding if the update will influence the review findings, quality, reliability, or credibility sufficiently to justify the effort in updating it. Those updating systematic reviews to author clinical practice guidelines might consider the influence of new study results in potentially overturning the conclusions of an existing review. Yet, even in cases where new study findings do not change the primary outcome measure, new studies can carry important information about subgroup effects, duration of treatment effects, and other relevant clinical information, enhancing the currency and breadth of review results.

An update requires appraisal and revision of the background, question, inclusion criteria, and methods of the existing review and the existing certainty in the evidence. In particular, methods might need to be updated, and search strategies reconsidered. Authors of updates need to consider inputs to the current edition, and follow ICMJE criteria regarding authorship. 56

The PUGs panel proposed a decision framework (fig 1 ⇑ ), with terms and categories for reporting the decisions made for updating procedures for adoption by Cochrane and other stakeholders. This framework includes journals publishing systematic review updates and independent authors considering updates of existing published reviews. The panel developed a checklist to help judgements about when and how to update.

The current emphasis of authors, guideline developers, Cochrane, and consequently this guidance has been on effects reviews. The checklists and guidance here still applies to other types of systematic reviews, such as those on diagnostic test accuracy, and this guidance will need adapting. Accumulative experience and methods development in reviews other than those of effects are likely to help refine guidance in the future.

This guidance could help groups identify and prioritise reviews for updating and hence use their finite resources to greatest effect. Software innovation and new management systems are being developed and in early use to help streamline review updates in the coming years.

Contributors: HJS initiated the workshop. JC, SH, PG, HM, and HJS organised the materials and the agenda. SH wrote up the proceedings. PG wrote the paper from the proceedings and coordinated the development of the final guidance; JC, SH, HM, and HJS were active in the finalising of the guidance. All PUGs authors contributed to three rounds of manuscript revision.

Funding: Attendance at this meeting, for those attendees not directly employed by Cochrane, was not funded by Cochrane beyond the reimbursement of out of pocket expenses for those attendees for whom this was appropriate. Expenses were not reimbursed for US federal government attendees, in line with US government policy. Statements in the manuscript should not be construed as endorsement by the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Competing interests: All participants have a direct or indirect interest in systematic reviews and updating as part of their job or academic career. Most participants contribute to Cochrane, whose mission includes a commitment to the updating of its systematic review portfolio. JC, HM, RM, CM, KS-W, and MT are, or were at that time, employed by the Cochrane Central Executive.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 3.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ .

- ↵ Shekelle PG, Ortiz E, Rhodes S, et al. Validity of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality clinical practice guidelines: how quickly do guidelines become outdated? JAMA 2001 ; 286 : 1461 - 7 . doi:10.1001/jama.286.12.1461 pmid:11572738 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Claxton K, Cohen JT, Neumann PJ. When is evidence sufficient? Health Aff (Millwood) 2005 ; 24 : 93 - 101 . doi:10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.93 pmid:15647219 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Fenwick E, Claxton K, Sculpher M, et al. Improving the efficiency and relevance of health technology assessment: the role of decision analytic modelling. Paper 179. Centre for Health Economics, University of York, 2000 .

- ↵ Sculpher M, Claxton K. Establishing the cost-effectiveness of new pharmaceuticals under conditions of uncertainty—when is there sufficient evidence? Value Health 2005 ; 8 : 433 - 46 . doi:10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.00033.x pmid:16091019 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Sculpher M, Drummond M, Buxton M. The iterative use of economic evaluation as part of the process of health technology assessment. J Health Serv Res Policy 1997 ; 2 : 26 - 30 . pmid:10180650 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Wilson E, Abrams K. From evidence based economics to economics based evidence: using systematic review to inform the design of future research. In: Shemilt I, Mugford M, Vale L, et al, eds. Evidence based economics. Blackwell Publishing, 2010 doi:10.1002/9781444320398.ch12 .

- ↵ Chalmers I, Enkin M, Keirse MJ. Preparing and updating systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials of health care. Milbank Q 1993 ; 71 : 411 - 37 . doi:10.2307/3350409 pmid:8413069 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Higgins J, Green S, Scholten R. Chapter 3. Maintaining reviews: updates, amendments and feedback: Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). Cochrane Collaboration, 2011 .

- ↵ Cochrane. Editorial and publishing policy resource. http://community.cochrane.org/editorial-and-publishing-policy-resource . 2016.

- ↵ Moher D, Tsertsvadze A. Systematic reviews: when is an update an update? Lancet 2006 ; 367 : 881 - 3 . doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68358-X pmid:16546523 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Prasad K, Singh MB, Ryan H. Corticosteroids for managing tuberculous meningitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016 ; 4 : CD002244 . pmid:27121755 . OpenUrl PubMed

- ↵ Zani B, Gathu M, Donegan S, Olliaro PL, Sinclair D. Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine for treating uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014 ; 1 : CD010927 . pmid:24443033 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Adams SP, Tsang M, Wright JM. Lipid lowering efficacy of atorvastatin. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012 ; 12 : CD008226 . pmid:23235655 . OpenUrl PubMed

- ↵ Higgins J. Convincing evidence from controlled and uncontrolled studies on the lipid-lowering effect of a statin. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012 ; 12 : ED000049 . pmid:23361645 . OpenUrl PubMed

- ↵ Takwoingi Y, Hopewell S, Tovey D, Sutton AJ. A multicomponent decision tool for prioritising the updating of systematic reviews. BMJ 2013 ; 347 : f7191 . doi:10.1136/bmj.f7191 pmid:24336453 . OpenUrl FREE Full Text

- ↵ MacLehose H, Hilton J, Tovey D, et al. The Cochrane Library: revolution or evolution? Shaping the future of Cochrane content. Background paper for The Cochrane Collaboration’s Strategic Session Paris, France, 18 April 2012. http://editorial-unit.cochrane.org/sites/editorial-unit.cochrane.org/files/uploads/2012-CC-strategic-session_full-report.pdf .

- ↵ Hemilä H, Chalker E. Vitamin C for preventing and treating the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013 ;( 1 ): CD000980 . pmid:23440782 .

- ↵ Hahn S, Kim S, Garner P. Reduced osmolarity oral rehydration solution for treating dehydration caused by acute diarrhoea in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002 ;( 1 ): CD002847 . pmid:11869639 .

- ↵ World Health Organization (WHO). Reduced osmolarity oral rehydration salts (ORS) formulation. A report from a meeting of Experts jointly organized by UNICEF and WHO. New York: Child and Adolescent Health and Development, 18 July 2001 http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/67322/1/WHO_FCH_CAH_01.22.pdf .

- ↵ Smaill FM, Grivell RM. Antibiotic prophylaxis versus no prophylaxis for preventing infection after cesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014 ;( 10 ): CD007482 . pmid:25350672 .

- ↵ Adjuik M, Babiker A, Garner P, Olliaro P, Taylor W, White N. International Artemisinin Study Group. Artesunate combinations for treatment of malaria: meta-analysis. Lancet 2004 ; 363 : 9 - 17 . doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15162-8 pmid:14723987 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Agnihotry A, Fedorowicz Z, Nasser M. Adhesively bonded versus non-bonded amalgam restorations for dental caries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016 ; 3 : CD007517 . pmid:26954446 . OpenUrl PubMed

- ↵ Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. Cochrane Bias Methods Group Cochrane Statistical Methods Group. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011 ; 343 : d5928 . doi:10.1136/bmj.d5928 pmid:22008217 . OpenUrl FREE Full Text

- ↵ Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, et al. QUADAS-2 Group. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med 2011 ; 155 : 529 - 36 . doi:10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009 pmid:22007046 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Sterne JAC, Higgins JPT, Reeves BC; on behalf of the development group for ROBINS-I. A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomized studies of interventions, version 7. March 2016. www.riskofbias.info .

- ↵ Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE Working Group. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008 ; 336 : 924 - 6 . doi:10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD pmid:18436948 . OpenUrl FREE Full Text

- ↵ Schünemann HJ. Interpreting GRADE’s levels of certainty or quality of the evidence: GRADE for statisticians, considering review information size or less emphasis on imprecision? J Clin Epidemiol 2016 ; 75 : 6 - 15 . doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.03.018 pmid:27063205 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Gough D. Qualitative and mixed methods in systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2015 ; 4 : 181 . doi:10.1186/s13643-015-0151-y pmid:26670769 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Richardson M, Garner P, Donegan S. Cluster randomised trials in Cochrane reviews: evaluation of methodological and reporting practice. PLoS One 2016 ; 11 : e0151818 . doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0151818 pmid:26982697 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2007 ; 7 : 10 . doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10 pmid:17302989 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Whiting P, Savović J, Higgins JP, et al. ROBIS group. ROBIS: A new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. J Clin Epidemiol 2016 ; 69 : 225 - 34 . doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.06.005 pmid:26092286 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Sampson M, Shojania KG, McGowan J, et al. Surveillance search techniques identified the need to update systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 2008 ; 61 : 755 - 62 . doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.10.003 pmid:18586179 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Hemens BJ, Haynes RB. McMaster Premium LiteratUre Service (PLUS) performed well for identifying new studies for updated Cochrane reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 2012 ; 65 : 62 - 72.e1 . doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.02.010 pmid:21856121 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Sagliocca L, De Masi S, Ferrigno L, Mele A, Traversa G. A pragmatic strategy for the review of clinical evidence. J Eval Clin Pract 2013 ; 19 : 689 - 96 . doi:10.1111/jep.12020 pmid:23317014 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Rada G, Peña J, Capurro D, et al. How to create a matrix of evidence in Epistemonikos. Abstracts of the 22nd Cochrane Colloquium; Evidence-informed public health: opportunities and challenges; Hyderabad, India. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014 ; suppl 1 : 132 .

- ↵ Okebe JU, Yahav D, Shbita R, Paul M. Oral iron supplements for children in malaria-endemic areas. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011 ;( 10 ): CD006589 . pmid:21975754 .

- ↵ Neuberger A, Okebe J, Yahav D, Paul M. Oral iron supplements for children in malaria-endemic areas. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016 ; 2 : CD006589 . pmid:26921618 . OpenUrl PubMed

- Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 2011 ; 64 : 401 - 6 . doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.015 pmid:21208779 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Chung M, Newberry SJ, Ansari MT, et al. Two methods provide similar signals for the need to update systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 2012 ; 65 : 660 - 8 . doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.12.004 pmid:22464414 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- Shojania KG, Sampson M, Ansari MT, Ji J, Doucette S, Moher D. How quickly do systematic reviews go out of date? A survival analysis. Ann Intern Med 2007 ; 147 : 224 - 33 . doi:10.7326/0003-4819-147-4-200708210-00179 pmid:17638714 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- Shojania K, Sampson M, Ansari M, et al. Updating systematic reviews; AHRQ technical reviews; report no 07-0087. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2007 .

- Pattanittum P, Laopaiboon M, Moher D, Lumbiganon P, Ngamjarus C. A comparison of statistical methods for identifying out-of-date systematic reviews. PLoS One 2012 ; 7 : e48894 . doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0048894 pmid:23185281 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- Shekelle PG, Motala A, Johnsen B, Newberry SJ. Assessment of a method to detect signals for updating systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2014 ; 3 : 13 . doi:10.1186/2046-4053-3-13 pmid:24529068 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- Shekelle PG, Newberry SJ, Wu H, et al. Identifying signals for updating systematic reviews: a comparison of two methods; report no 11-EHC042-EF. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2011 .

- ↵ Shekelle P, Newberry S, Maglione M, et al. Assessment of the need to update comparative effectiveness reviews: report of an initial rapid program assessment (2005-2009). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2009 .

- Tovey D, Marshall R, Bazian, Hopewell S, Rader T. Fit for purpose: centralised updating support for high-priority Cochrane Reviews; National Institute for Health Research Cochrane-National Health Service Engagement Award Scheme, July 2011. https://editorial-unit.cochrane.org/sites/editorial-unit.cochrane.org/files/uploads/10_4000_01%20Fit%20for%20purpose%20-%20centralised%20updating%20support%20for%20high%20priority%20Cochrane%20Reviews%20FINAL%20REPORT.pdf .

- Claxton K. The irrelevance of inference: a decision-making approach to the stochastic evaluation of health care technologies. J Health Econ 1999 ; 18 : 341 - 64 . doi:10.1016/S0167-6296(98)00039-3 pmid:10537899 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- Wilson EC. A practical guide to value of information analysis. Pharmacoeconomics 2015 ; 33 : 105 - 21 . doi:10.1007/s40273-014-0219-x pmid:25336432 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Althabe F, Belizán JM, McClure EM, et al. A population-based, multifaceted strategy to implement antenatal corticosteroid treatment versus standard care for the reduction of neonatal mortality due to preterm birth in low-income and middle-income countries: the ACT cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2015 ; 385 : 629 - 39 . doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61651-2 pmid:25458726 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Taylor-Robinson D, Maayan N, Soares-Weiser K, et al. Deworming drugs for soil-transmitted intestinal worms in children: effects on nutritional indicators, haemoglobin and school performance. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012 ;( 11 ): CD000371 .

- ↵ van Dalen EC, van der Pal HJ, Kremer LC. Different dosage schedules for reducing cardiotoxicity in people with cancer receiving anthracycline chemotherapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016 ; 3 : CD005008 . pmid:26938118 . OpenUrl PubMed

- ↵ Wilson E. on behalf of the Cochrane Priority Setting and Campbell & Cochrane Economics Methods Groups. Which study when? Proof of concept of a proposed automated tool to help decision which reviews to update first. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014 ; suppl 2 : 29 - 31 .

- Rosenbaum SE, Glenton C, Nylund HK, Oxman AD. User testing and stakeholder feedback contributed to the development of understandable and useful Summary of Findings tables for Cochrane reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 2010 ; 63 : 607 - 19 . doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.12.013 pmid:20434023 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- Rosenbaum SE, Glenton C, Oxman AD. Summary-of-findings tables in Cochrane reviews improved understanding and rapid retrieval of key information. J Clin Epidemiol 2010 ; 63 : 620 - 6 . doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.12.014 pmid:20434024 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- Vandvik PO, Santesso N, Akl EA, et al. Formatting modifications in GRADE evidence profiles improved guideline panelists comprehension and accessibility to information. A randomized trial. J Clin Epidemiol 2012 ; 65 : 748 - 55 . doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.013 pmid:22564503 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE). Defining the role of authors and contributors. 2016. www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/roles-and-responsibilities/defining-the-role-of-authors-and-contributors.html .

- ↵ Stovold E, Beecher D, Foxlee R, Noel-Storr A. Study flow diagrams in Cochrane systematic review updates: an adapted PRISMA flow diagram. Syst Rev 2014 ; 3 : 54 . doi:10.1186/2046-4053-3-54 pmid:24886533 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Newberry SJ, Shekelle PG, Vaiana M, et al. Reporting the findings of updated systematic reviews of comparative effectiveness: how do users want to view new information? report no 13-EHC093-EF. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2013 .

- Marshall IJ, Kuiper J, Wallace BC. Automating risk of bias assessment for clinical trials BCB’14. Proceedings of the 5th ACM conference on Bioinformatics, computational biology, and health informatics. 2014:88-95. http://thirdworld.nl/automating-risk-of-bias-assessment-for-clinical-trials .

- ↵ Elliott JH, Turner T, Clavisi O, et al. Living systematic reviews: an emerging opportunity to narrow the evidence-practice gap. PLoS Med 2014 ; 11 : e1001603 . doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001603 pmid:24558353 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- Elliott J, Sim I, Thomas J, et al. #CochraneTech: technology and the future of systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014 ;( 9 ): ED000091 . pmid:25288182 .

- Cochrane. Project transform: the Cochrane Collaboration. 2016. http://community.cochrane.org/tools/project-coordination-and-support/transform .

- ↵ Paynter R, Bañez L, Berlinerm E, et al. EPC methods: an exploration of the use of text-mining software in systematic reviews. Research white paper. AHRQ publication 16-EHC023-EF. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, April 2016. https://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/search-for-guides-reviews-and-reports/?pageaction=displayproduct&productID=2214 .

- ↵ Soares-Weiser K, Marshall R, Bergman H, et al. Updating Cochrane Reviews: results of the first pilot of a focused update. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014 ; suppl 1 : 31 - 3 .

- A t tachments (0)

- Page History

- Page Information

- Resolved comments

- View in Hierarchy

- View Source

- Export to PDF

- Export to Word

Reporting search dates in Cochrane Reviews

- Created by Harriet MacLehose , last modified on Jul 15, 2019

Version history

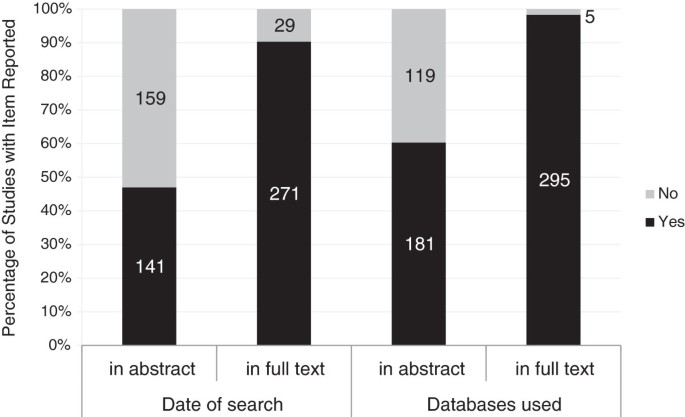

This policy covers the reporting of search dates in Cochrane Reviews. It is informed by guidance on re-running searches covered i n MECIR conduct standard C37 . This standard requires that searches for all relevant databases be run (or re-run) within 12 months before publication of the review or review update, and that the results are screened for potentially eligible studies.

For definitions of search types (full, top-up, scoping) see Table below.

- Updates vs. amendments: a review is considered updated and receives a new citation in Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews ( CDSR ) when a new search is conducted and the results of the search are fully incorporated. If a scoping search is conducted to determine if an update is required, then the date of this search will not change the 'Date of search' in the review or lead to a new citation version being created. This should be published as an amendment if necessary; see Assigning ‘What’s New’ events to Cochrane Reviews .

- If top-up searches are performed and the results incorporated then that top-up search date becomes the date of the full search (i.e. the date that appears in the ‘Date of Search’ field).

- The ‘Date of search’ remains the date of the search for which results were fully incorporated.

- Studies not yet fully incorporated into the review are added to ‘Studies awaiting classification’.

- The ' Search methods' in the abstract should focus on reporting the search dates related to the last fully incorporated studies. Brief mention of a top-up search may be made only if it was conducted for a completed update or new review. Do not refer to scoping searches for updating in the abstract.

- The 'Search methods for identification of studies' in the main text of the review should be used primarily to describe the details of the search for which the results have been fully incorporated, i.e. the dates of individual database searching and the hits retrieved should be based on the search date where results are fully incorporated. If a top-up search has been performed, but the results not yet fully incorporated, the search section may briefly describe this (see example below) and state how many studies have been placed in 'Studies awaiting classification'.

- In the 'Results of the search' section the authors should specify the number of studies yet to be fully incorporated into the review. This should also be reflected in the conclusions (both of the main review and the abstract).

- The PRISMA flow of studies diagram should also reflect the number of studies in the 'Studies awaiting classification' section.

- The 'What’s New' events must describe the number of studies that have been put into 'Studies awaiting classification' if the top-up search is mentioned in the search methods section.

- The search appendix should present only database strategies for searches conducted for which results were fully incorporated.

- If different databases were searched on different dates , the most recent date of the search for each database should be given within the text of the review and the earliest of these dates should be entered as the ‘Date of Search’. In the case of review updates or 'top-up' searches, if there is clear rationale for not searching one or more of the previously searched databases (e.g. because no unique relevant records were identified in the original/previous search, or the database is no longer being updated), the rationale should be stated within the text of the review. In this case, the 'Date of search' should be the earliest date of the searches performed for this smaller set of databases.

Definitions of search types (full, top-up, scoping)

|

|

|---|---|

Full search – results fully incorporated | Electronic search strategies run in full in all relevant databases AND all search results are assessed for eligibility as included, excluded, or ongoing studies. Only if all reasonable efforts to classify search results have failed should they be placed in ‘Studies awaiting classification.’* |

Top-up search – results not fully incorporated | Electronic search strategies run in full in all relevant databases BUT search results are not all assessed for eligibility, instead they are placed in 'Studies awaiting classification'. |

Scoping search for updating | Electronic search strategies run in selected databases to determine if an update is required. |

| *See R6 and R34 in ; and . | |

Examples of reporting top-up searches

The number of instances where a top-up search is performed and potential new studies are identified but not fully incorporated before publication should remain low. The following examples show how such searches should be described in various sections of a systematic review:

Do not change the 'Date of search' or th e 'Assessed as up-to-date' (see Note for editorial base staff ) in the Cochrane Review 'Information’ section. Also, if less than 10 trial reports then list here in parentheses and link. For example:

"The search was updated in month/year and n trial reports added to ‘Studies awaiting classification’ (e.g. Bertini 2005; Crowther 2005; Gillen 2004)."

Search methods

The focus should remain on the text about previous searches (fully incorporated) but the top-up search may be mentioned. For example:

"We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, Embase, and CINAHL (June 2013). We updated this search in September 2014, but these results have not yet been incorporated."

Search methods for identification of studies

The search should be reported as per MECIR reporting standards R34 to 39, including the dates for each source. At the end of the search methods section, it is appropriate to add the following text:

"We performed a further search in [month/year]. Those results have been added to 'Studies awaiting classification' and will be incorporated into the review at the next update."

Do not list all databases and the dates. If a top-up search in reported in this section, only a single month (or range of months) and year should be shown.

Results: Description of studies

This section will differ depending on the review, so add text where it is most appropriate); for example:

"[insert number] study reports from an updated search in [month/year] have been added to 'Studies awaiting classification'."

Discussion: Potential biases in the review process

Acknowledge the potential impact of un-incorporated studies as a source of potential bias, especially if studies concerned are potentially important in terms of sample size or direction of effect; for example:

"We attempted to conduct a comprehensive search for studies, but the fact that [insert number] studies have not yet been incorporated may be a source of potential bias."

Authors’ conclusions (Implications for practice)

This is not an implication for practice as such, but users should be alerted to the issue of un-incorporated studies, particularly if the studies concerned are potentially important in terms of sample size or direction of effect; for example:

"The [insert number] studies in 'Studies awaiting classification' may alter the conclusions of the review once assessed."

Note for editorial base staff

One date should be used to reflect the search and full incorporation of all search results into the review; this date is the ‘Date of search’. Standard practice has been to publish the 'Assessed as up-to-date' field and not the 'Date of search'. Until the 'Assessed as up-to-date' field is removed from RevMan these two dates must be the same. If these fields have been completed by a member of the author team, editorial base staff must check that there is agreement between dates.

Powered by a free Atlassian Confluence Community License granted to Cochrane. Evaluate Confluence today .

- Powered by Atlassian Confluence 8.5.4

- Printed by Atlassian Confluence 8.5.4

- Report a bug

- Atlassian News

Our site uses cookies to improve your experience. You can find out more about our use of cookies in About Cookies, including instructions on how to turn off cookies if you wish to do so. By continuing to browse this site you agree to us using cookies as described in About Cookies .

The Cochrane Library

Trusted evidence. Informed decisions. Better health.

Scolaris Search Portlet Scolaris Search Portlet

Scolaris language selector scolaris language selector.

| Select your preferred language for Cochrane Reviews and other content. Sections without translation will be in English. | ||

| Select your preferred language for the Cochrane Library website. | ||

Scolaris Content Language Banner Portlet Scolaris Content Language Banner Portlet

Web content display web content display.

Undernutrition as a risk factor for TB

Anti-VEGF biosimilars for nAMD

Magnesium for preterm babies

- Highlighted Reviews

- Special Collections

Scolaris Content List Scolaris Content List

Peritoneal dialysis versus haemodialysis for people commencing dialysis

Isabelle Ethier, Ashik Hayat, Juan Pei, Carmel M Hawley, David W Johnson, Ross S Francis, Germaine Wong, Jonathan C Craig, Andrea K Viecelli, Yeoungjee Cho, Htay Htay, Samantha Ng, Saskia Leibowitz

Treatments for intractable constipation in childhood

Morris Gordon, Ciaran Grafton-Clarke, Shaman Rajindrajith, MA Benninga, Vassiliki Sinopoulou, Anthony K Akobeng

Factors that influence participation in physical activity for people with bipolar disorder: a synthesis of qualitative evidence

Claire J McCartan, Jade Yap, Paul Best, Josefien Breedvelt, Gavin Breslin, Joseph Firth, Mark A Tully, Paul Webb, Chris White, Simon Gilbody, Rachel Churchill, Gavin Davidson

Metformin for preventing the progression of chronic kidney disease

Ragada El-Damanawi a , Isabelle Kitty Stanley a , Christine Staatz, Elaine M Pascoe, Jonathan C Craig, David W Johnson, Andrew J Mallett, Carmel M Hawley, Elasma Milanzi, Thomas F Hiemstra, Andrea K Viecelli

External electrical and pharmacological cardioversion for atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter or atrial tachycardias: a network meta‐analysis

Kishore Kukendrarajah, Mahmood Ahmad, Mafalda Carrington, Adam Ioannou, Julie Taylor, Yousuf Razvi, Nikolaos Papageorgiou, Gillian E Mead, Immaculate F Nevis, Fabrizio D'Ascenzo, Stephen B Wilton, Pier D Lambiase, Carlos A Morillo, Joey SW Kwong, Rui Providencia

View Current Issue

Editorial List Editorial List

Zoe Jordan, Vivian Welch, Karla Soares-Weiser

Yi Feng Lai, Stephanie Q Ko

Rebecca E Ryan, Sophie Hill

Patrick M Bossuyt, Jonathan J Deeks, Mariska M Leeflang, Yemisi Takwoingi, Ella Flemyng

Sharon R Lewis, Xavier L Griffin

Scolaris Special Collection Scolaris Special Collection

- Browse by PICOs

Browse by Topic

Browse by picos .

The PICO model is widely used and taught in evidence-based health care as a strategy for formulating questions and search strategies and for characterizing clinical studies or meta-analyses . PICO stands for four different potential components of a clinical question: Patient, Population or Problem; Intervention; Comparison; Outcome.

See more on using PICO in the Cochrane Handbook .

| Population | Intervention & Comparison | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

Browse Cochrane Reviews, Protocols and Clinical Answers.

- Allergy & intolerance

- Blood disorders

- Child health

- Complementary & alternative medicine

- Consumer & communication strategies

- Dentistry & oral health

- Developmental, psychosocial & learning problems

- Ear, nose & throat

- Effective practice & health systems

- Endocrine & metabolic

- Eyes & vision

- Gastroenterology & hepatology

- Genetic disorders

- Gynaecology

- Health & safety at work

- Health professional education

- Heart & circulation

- Infectious disease

- Insurance medicine

- Kidney disease

- Lungs & airways

- Mental health

- Methodology

- Neonatal care

- Orthopaedics & trauma

- Pain & anaesthesia

- Pregnancy & childbirth

- Public health

- Reproductive & sexual health

- Rheumatology

- Skin disorders

- Tobacco, drugs & alcohol

Scolaris Language Sponsor Footer Scolaris Language Sponsor Footer

Sign in sign in, scolaris content display scolaris content display.

Search for your institution's name below to login via Shibboleth

Previously accessed institutions

If you have a Wiley Online Library institutional username and password, enter them here.

Institutional users

Other access options.

- Individual access - via Wiley Online Library

- McGill Library

Systematic Reviews, Scoping Reviews, and other Knowledge Syntheses

- Updating the database searches

- Types of knowledge syntheses

- Identifying the research question

- Developing the protocol

- Database-specific operators and fields

- Search filters and tools

- Exporting and documenting search results

- Deduplicating

- Grey literature and other supplementary search methods

- Documenting the search methods

Updating the database searches using Covidence

Alternative: updating the database searches using indexing dates, bibliography.

- Resources for screening, appraisal, and synthesis

- Writing the review

- Additional training resources

To update your searches, we recommend rerunning your saved searches, exporting all the records to RIS files, and then importing those RIS files into Covidence for deduplication. This is our recommended approach to updating searches to retrieve new records only, as well as for removing duplicate records.

If you do this, be sure to follow the instructions provided by Covidence (e.g., download your PRISMA flow diagram before adding the new RIS files to a previous review).

How to update a review with new studies

There are different methods that you can use to update your searches, and they are usually database-specific. What you are trying to do is avoid screening the same records all over again.

In Covidence, you can simply import all the records generated by the new/updated searches, and Covidence will remove records that have already been uploaded . If you do this, be sure to follow the instructions provided by Covidence (e.g., download your PRISMA flow diagram before adding the new RIS files to a previous review).

Another method is to restrict records to those entered into the database on or after the date you last ran the search (note: this is NOT the publication date, this is the date the record was added to the database, and this date field is not available in all databases).

This can be done in PubMed, MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), Scopus, CINAHL (EBSCOhost), APA PsycInfo (Ovid), CENTRAL (Cochrane Library/Wiley), and Web of Science Core Collection (as well as others), but the entry date is not available as a search field in all databases and it may miss records .

Please note: The field codes are subject to change and we strongly suggest checking the database information, particularly at the beginning of a new year, when indexing changes are more likely to occur. Please also let us know if you identify issues with these codes. This table was last updated April 2, 2024 (Correction: da refers to MeSH Date in Ovid MEDLINE).

Many thanks to those who reach out to let us know when there are issues or corrections needed!

| Database | Platform | Suggested Search Field(s) | Example of a search last run on July 1, 2019 and updated on May 1, 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|

| CENTRAL/Trials | Cochrane Library/Wiley | Use "Date" filter | View search results / Select Trials tab > Under "Filter your results" (left column), enter date range ("Date added to CENTRAL trials database") as custom range 01/07/2019 to 01/05/2023

|

| PubMed ( ) | - | CRDT OR EDAT OR MHDA | #x AND ("2019/07/01"[CRDT] : "3000"[CRDT] OR "2019/07/01"[EDAT] : "3000"[EDAT] OR "2019/07/01"[MHDA] : "3000"[MHDA]) (MHDA refers to the date that MeSH are added and may increase duplicates but can identify indexed records previously missed by textword searching) |

| MEDLINE ( ) | OvidSP | .dt,ez,da. (Create Date, Entrez date; MeSH date) | (201907* OR 201908* OR 201909* OR 20191* OR 202*).dt,ez,da. (da refers to the date that MeSH are added and may increase duplicates but can identify indexed records previously missed by textword searching) |

| Embase ( ) | OvidSP | .dc. | limit x to dc=20190701-20230501 |

| PsycInfo ( ) | OvidSP | .up. | limit x to up=20190701-20230501 |

| CINAHL ( ) | EBSCOhost | (EM yyyymmdd- OR (ZD "in process" AND RD yyyymmdd-)) | (EM 20190701- OR (ZD "in process" AND RD 20190701-)) |

| Scopus | ORIG-LOAD-DATE AFT | ORIG-LOAD-DATE AFT 20190630 | |

| Web of Science Core Collection (new Web of Science platform) | Web of Science | LD | Select Index Date: 2019-07-01 to 2023-05-01 OR From Advanced Search Query Builder > Query Preview: LD=(2019-07-01/2023-05-01)

|

See also: Garner P, Hopewell S, Chandler J, MacLehose H, Akl EA, Beyene J, Chang S, Churchill R, Dearness K, Guyatt G, Lefebvre C, Liles B, Marshall R, Martínez García L, Mavergames C, Nasser M, Qaseem A, Sampson M, Soares-Weiser K, Takwoingi Y, Thabane L, Trivella M, Tugwell P, Welsh E, Wilson EC, Schünemann HJ. When and How to Update Systematic Reviews: Consensus and Checklist . BMJ. 2016;354. 10.1136/bmj.i3507

Due to a large influx of requests, there may be an extended wait time for librarian support on knowledge syntheses.

Find a librarian in your subject area to help you with your knowledge synthesis project.

Or contact the librarians at the Schulich Library of Physical Sciences, Life Sciences, and Engineering s [email protected]

Need help? Ask us!

- << Previous: Documenting the search methods

- Next: Resources for screening, appraisal, and synthesis >>

- Last Updated: Jun 27, 2024 12:05 PM

- URL: https://libraryguides.mcgill.ca/knowledge-syntheses

McGill Library • Questions? Ask us! Privacy notice

- Interlibrary Loan

Ask an Expert

Ask an expert about access to resources, publishing, grants, and more.

MD Anderson faculty and staff can also request a one-on-one consultation with a librarian or scientific editor.

- Library Calendar

Log in to the Library's remote access system using your MyID account.

- Library Home

- Research Guides

- Systematic Reviews

Updating a Systematic Review

Systematic reviews: updating a systematic review.

- Introduction

- Step-by-Step

- Standards and Guidelines

- Designing the Protocol

- Selecting Studies

- Appraising Studies

- Data Extraction

- Writing a Systematic Review

- Meta-analyses

- Evaluating a Systematic Review

- Cochrane Systematic Reviews

- Get more help

- Related Review Types

Systematic reviews need to be evaluated on a periodic basis to determine if they need to be updated. If it's likely that new studies have come out and the topic is still of interest to clinicians and decision makers then it should be updated.

Cochrane Handbook Ch IV: Updating a Review

Cochrane MECIR Manual: Reporting Standards Specific to Updates

Cochrane Handbook Ch 22.2 Maintaining the currency of systematic reviews

PRISMA Flow Diagrams for SR Updates

Living Systematic Reviews

"Living" systematic reviews are updated on a periodic basis, often monthly. Any new evidence is immediately incorporated into the published review. Needless to say, this is very time-consuming so this type of updating is usually only used for topics that are of high importance to decision makers, on which new evidence is frequently published. More information and examples are at Cochrane's LSRs and LSR Protocols .

Searching for New Studies

It can be challenging to search the databases and retrieve only the new studies that have been added since the last time you searched. Each database uses different date fields and some databases are not able to restrict a search to a specific month and year. Another challenge is that sometimes older articles are added to the databases so if you only search the new time period you might miss articles that were retrospectively added.

There are two solutions.

1. Run new searches on the entire time period, even the years you've already looked at. De-duplicate your new search results against the previous search results which you have hopefully saved. This is relatively easy to do in EndNote but can be cumbersome and slow if you have thousands of results.

2 Run new searches not by publication date but by the date they were entered into the databases. This will retrieve articles that weren't in the databases the last time you searched no matter what their publication date is. Unfortunately, this isn't possible in all databases but it is in most. Here are the methods to do it:

- PubMed: XYZSearchString AND ("2018/12/25"[EDAT] : "3000"[EDAT])

- Ovid Medline: limit LastLineOfSearch to dt="20181225-20201225"

- Ovid Embase: limit LastLineOfSearch to dc=20181225-20201225

- Cochrane Library: use the Custom Date Range box [publication date, not entry date]

- Ovid PsychINFO: limit LastLineOfSearch to up=20181225-20201225

- Scopus: Search Within Results: ORIG-LOAD-DATE AFT 20181225

- CINAHL (Ebsco): AND new line: EM 20181225-20201225

- Web of Science : AND PY=(2018-2020) [can only search by publication date and year]

- ClinicalTrials.gov : Use the "First Posted" date field

- << Previous: Evaluating a Systematic Review

- Next: Cochrane Systematic Reviews >>

- Last Updated: May 2, 2024 2:38 PM

- URL: https://mdanderson.libguides.com/systematicreviews

Improving your search strategy: date limit filters (2/2)

May 6, 2021

This blog post follows on from ‘ Improving your search strategy: Randomised controlled trial filters ’.

Electronic database searches can be run on multiple platforms. This article focusses primarily on applying date limits in Ovid.

When to use date limit filters