Systematic Reviews

- Introduction

- Guidelines and procedures

- Management tools

- Define the question

- Check the topic

- Determine inclusion/exclusion criteria

- Develop a protocol

- Identify keywords

- Databases and search strategies

- Grey literature

- Manage and organise

- Screen & Select

- Locate full text

- Extract data

Example reviews

- Examples of systematic reviews

- Accessing help This link opens in a new window

- Systematic Style Reviews Guide This link opens in a new window

Please choose the tab below for your discipline to see relevant examples.

For more information about how to conduct and write reviews, please see the Guidelines section of this guide.

- Health & Medicine

- Social sciences

- Vibration and bubbles: a systematic review of the effects of helicopter retrieval on injured divers. (2018).

- Nicotine effects on exercise performance and physiological responses in nicotine‐naïve individuals: a systematic review. (2018).

- Association of total white cell count with mortality and major adverse events in patients with peripheral arterial disease: A systematic review. (2014).

- Do MOOCs contribute to student equity and social inclusion? A systematic review 2014–18. (2020).

- Interventions in Foster Family Care: A Systematic Review. (2020).

- Determinants of happiness among healthcare professionals between 2009 and 2019: a systematic review. (2020).

- Systematic review of the outcomes and trade-offs of ten types of decarbonization policy instruments. (2021).

- A systematic review on Asian's farmers' adaptation practices towards climate change. (2018).

- Are concentrations of pollutants in sharks, rays and skates (Elasmobranchii) a cause for concern? A systematic review. (2020).

- << Previous: Write

- Next: Publish >>

- Last Updated: May 13, 2024 5:20 PM

- URL: https://libguides.jcu.edu.au/systematic-review

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Systematic Review | Definition, Examples & Guide

Systematic Review | Definition, Examples & Guide

Published on 15 June 2022 by Shaun Turney . Revised on 17 October 2022.

A systematic review is a type of review that uses repeatable methods to find, select, and synthesise all available evidence. It answers a clearly formulated research question and explicitly states the methods used to arrive at the answer.

They answered the question ‘What is the effectiveness of probiotics in reducing eczema symptoms and improving quality of life in patients with eczema?’

In this context, a probiotic is a health product that contains live microorganisms and is taken by mouth. Eczema is a common skin condition that causes red, itchy skin.

Table of contents

What is a systematic review, systematic review vs meta-analysis, systematic review vs literature review, systematic review vs scoping review, when to conduct a systematic review, pros and cons of systematic reviews, step-by-step example of a systematic review, frequently asked questions about systematic reviews.

A review is an overview of the research that’s already been completed on a topic.

What makes a systematic review different from other types of reviews is that the research methods are designed to reduce research bias . The methods are repeatable , and the approach is formal and systematic:

- Formulate a research question

- Develop a protocol

- Search for all relevant studies

- Apply the selection criteria

- Extract the data

- Synthesise the data

- Write and publish a report

Although multiple sets of guidelines exist, the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews is among the most widely used. It provides detailed guidelines on how to complete each step of the systematic review process.

Systematic reviews are most commonly used in medical and public health research, but they can also be found in other disciplines.

Systematic reviews typically answer their research question by synthesising all available evidence and evaluating the quality of the evidence. Synthesising means bringing together different information to tell a single, cohesive story. The synthesis can be narrative ( qualitative ), quantitative , or both.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Systematic reviews often quantitatively synthesise the evidence using a meta-analysis . A meta-analysis is a statistical analysis, not a type of review.

A meta-analysis is a technique to synthesise results from multiple studies. It’s a statistical analysis that combines the results of two or more studies, usually to estimate an effect size .

A literature review is a type of review that uses a less systematic and formal approach than a systematic review. Typically, an expert in a topic will qualitatively summarise and evaluate previous work, without using a formal, explicit method.

Although literature reviews are often less time-consuming and can be insightful or helpful, they have a higher risk of bias and are less transparent than systematic reviews.

Similar to a systematic review, a scoping review is a type of review that tries to minimise bias by using transparent and repeatable methods.

However, a scoping review isn’t a type of systematic review. The most important difference is the goal: rather than answering a specific question, a scoping review explores a topic. The researcher tries to identify the main concepts, theories, and evidence, as well as gaps in the current research.

Sometimes scoping reviews are an exploratory preparation step for a systematic review, and sometimes they are a standalone project.

A systematic review is a good choice of review if you want to answer a question about the effectiveness of an intervention , such as a medical treatment.

To conduct a systematic review, you’ll need the following:

- A precise question , usually about the effectiveness of an intervention. The question needs to be about a topic that’s previously been studied by multiple researchers. If there’s no previous research, there’s nothing to review.

- If you’re doing a systematic review on your own (e.g., for a research paper or thesis), you should take appropriate measures to ensure the validity and reliability of your research.

- Access to databases and journal archives. Often, your educational institution provides you with access.

- Time. A professional systematic review is a time-consuming process: it will take the lead author about six months of full-time work. If you’re a student, you should narrow the scope of your systematic review and stick to a tight schedule.

- Bibliographic, word-processing, spreadsheet, and statistical software . For example, you could use EndNote, Microsoft Word, Excel, and SPSS.

A systematic review has many pros .

- They minimise research b ias by considering all available evidence and evaluating each study for bias.

- Their methods are transparent , so they can be scrutinised by others.

- They’re thorough : they summarise all available evidence.

- They can be replicated and updated by others.

Systematic reviews also have a few cons .

- They’re time-consuming .

- They’re narrow in scope : they only answer the precise research question.

The 7 steps for conducting a systematic review are explained with an example.

Step 1: Formulate a research question

Formulating the research question is probably the most important step of a systematic review. A clear research question will:

- Allow you to more effectively communicate your research to other researchers and practitioners

- Guide your decisions as you plan and conduct your systematic review

A good research question for a systematic review has four components, which you can remember with the acronym PICO :

- Population(s) or problem(s)

- Intervention(s)

- Comparison(s)

You can rearrange these four components to write your research question:

- What is the effectiveness of I versus C for O in P ?

Sometimes, you may want to include a fourth component, the type of study design . In this case, the acronym is PICOT .

- Type of study design(s)

- The population of patients with eczema

- The intervention of probiotics

- In comparison to no treatment, placebo , or non-probiotic treatment

- The outcome of changes in participant-, parent-, and doctor-rated symptoms of eczema and quality of life

- Randomised control trials, a type of study design

Their research question was:

- What is the effectiveness of probiotics versus no treatment, a placebo, or a non-probiotic treatment for reducing eczema symptoms and improving quality of life in patients with eczema?

Step 2: Develop a protocol

A protocol is a document that contains your research plan for the systematic review. This is an important step because having a plan allows you to work more efficiently and reduces bias.

Your protocol should include the following components:

- Background information : Provide the context of the research question, including why it’s important.

- Research objective(s) : Rephrase your research question as an objective.

- Selection criteria: State how you’ll decide which studies to include or exclude from your review.

- Search strategy: Discuss your plan for finding studies.

- Analysis: Explain what information you’ll collect from the studies and how you’ll synthesise the data.

If you’re a professional seeking to publish your review, it’s a good idea to bring together an advisory committee . This is a group of about six people who have experience in the topic you’re researching. They can help you make decisions about your protocol.

It’s highly recommended to register your protocol. Registering your protocol means submitting it to a database such as PROSPERO or ClinicalTrials.gov .

Step 3: Search for all relevant studies

Searching for relevant studies is the most time-consuming step of a systematic review.

To reduce bias, it’s important to search for relevant studies very thoroughly. Your strategy will depend on your field and your research question, but sources generally fall into these four categories:

- Databases: Search multiple databases of peer-reviewed literature, such as PubMed or Scopus . Think carefully about how to phrase your search terms and include multiple synonyms of each word. Use Boolean operators if relevant.

- Handsearching: In addition to searching the primary sources using databases, you’ll also need to search manually. One strategy is to scan relevant journals or conference proceedings. Another strategy is to scan the reference lists of relevant studies.

- Grey literature: Grey literature includes documents produced by governments, universities, and other institutions that aren’t published by traditional publishers. Graduate student theses are an important type of grey literature, which you can search using the Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (NDLTD) . In medicine, clinical trial registries are another important type of grey literature.

- Experts: Contact experts in the field to ask if they have unpublished studies that should be included in your review.

At this stage of your review, you won’t read the articles yet. Simply save any potentially relevant citations using bibliographic software, such as Scribbr’s APA or MLA Generator .

- Databases: EMBASE, PsycINFO, AMED, LILACS, and ISI Web of Science

- Handsearch: Conference proceedings and reference lists of articles

- Grey literature: The Cochrane Library, the metaRegister of Controlled Trials, and the Ongoing Skin Trials Register

- Experts: Authors of unpublished registered trials, pharmaceutical companies, and manufacturers of probiotics

Step 4: Apply the selection criteria

Applying the selection criteria is a three-person job. Two of you will independently read the studies and decide which to include in your review based on the selection criteria you established in your protocol . The third person’s job is to break any ties.

To increase inter-rater reliability , ensure that everyone thoroughly understands the selection criteria before you begin.

If you’re writing a systematic review as a student for an assignment, you might not have a team. In this case, you’ll have to apply the selection criteria on your own; you can mention this as a limitation in your paper’s discussion.

You should apply the selection criteria in two phases:

- Based on the titles and abstracts : Decide whether each article potentially meets the selection criteria based on the information provided in the abstracts.

- Based on the full texts: Download the articles that weren’t excluded during the first phase. If an article isn’t available online or through your library, you may need to contact the authors to ask for a copy. Read the articles and decide which articles meet the selection criteria.

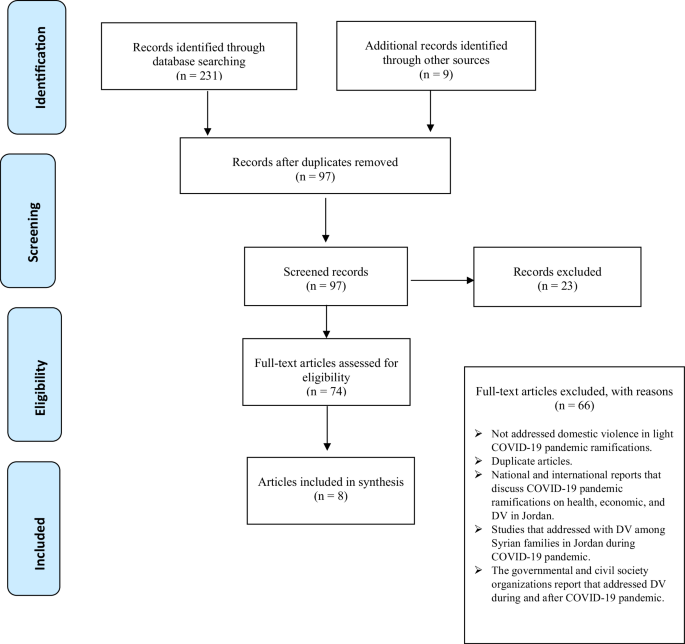

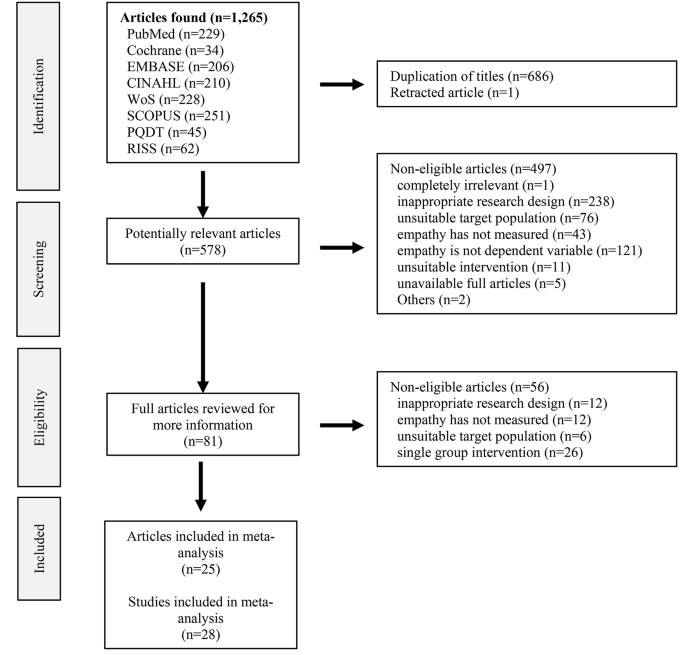

It’s very important to keep a meticulous record of why you included or excluded each article. When the selection process is complete, you can summarise what you did using a PRISMA flow diagram .

Next, Boyle and colleagues found the full texts for each of the remaining studies. Boyle and Tang read through the articles to decide if any more studies needed to be excluded based on the selection criteria.

When Boyle and Tang disagreed about whether a study should be excluded, they discussed it with Varigos until the three researchers came to an agreement.

Step 5: Extract the data

Extracting the data means collecting information from the selected studies in a systematic way. There are two types of information you need to collect from each study:

- Information about the study’s methods and results . The exact information will depend on your research question, but it might include the year, study design , sample size, context, research findings , and conclusions. If any data are missing, you’ll need to contact the study’s authors.

- Your judgement of the quality of the evidence, including risk of bias .

You should collect this information using forms. You can find sample forms in The Registry of Methods and Tools for Evidence-Informed Decision Making and the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations Working Group .

Extracting the data is also a three-person job. Two people should do this step independently, and the third person will resolve any disagreements.

They also collected data about possible sources of bias, such as how the study participants were randomised into the control and treatment groups.

Step 6: Synthesise the data

Synthesising the data means bringing together the information you collected into a single, cohesive story. There are two main approaches to synthesising the data:

- Narrative ( qualitative ): Summarise the information in words. You’ll need to discuss the studies and assess their overall quality.

- Quantitative : Use statistical methods to summarise and compare data from different studies. The most common quantitative approach is a meta-analysis , which allows you to combine results from multiple studies into a summary result.

Generally, you should use both approaches together whenever possible. If you don’t have enough data, or the data from different studies aren’t comparable, then you can take just a narrative approach. However, you should justify why a quantitative approach wasn’t possible.

Boyle and colleagues also divided the studies into subgroups, such as studies about babies, children, and adults, and analysed the effect sizes within each group.

Step 7: Write and publish a report

The purpose of writing a systematic review article is to share the answer to your research question and explain how you arrived at this answer.

Your article should include the following sections:

- Abstract : A summary of the review

- Introduction : Including the rationale and objectives

- Methods : Including the selection criteria, search method, data extraction method, and synthesis method

- Results : Including results of the search and selection process, study characteristics, risk of bias in the studies, and synthesis results

- Discussion : Including interpretation of the results and limitations of the review

- Conclusion : The answer to your research question and implications for practice, policy, or research

To verify that your report includes everything it needs, you can use the PRISMA checklist .

Once your report is written, you can publish it in a systematic review database, such as the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , and/or in a peer-reviewed journal.

A systematic review is secondary research because it uses existing research. You don’t collect new data yourself.

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a dissertation , thesis, research paper , or proposal .

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarise yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Turney, S. (2022, October 17). Systematic Review | Definition, Examples & Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved 6 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/systematic-reviews/

Is this article helpful?

Shaun Turney

Other students also liked, what is a literature review | guide, template, & examples, exploratory research | definition, guide, & examples, what is peer review | types & examples.

How to Do a Systematic Review: A Best Practice Guide for Conducting and Reporting Narrative Reviews, Meta-Analyses, and Meta-Syntheses

Affiliations.

- 1 Behavioural Science Centre, Stirling Management School, University of Stirling, Stirling FK9 4LA, United Kingdom; email: [email protected].

- 2 Department of Psychological and Behavioural Science, London School of Economics and Political Science, London WC2A 2AE, United Kingdom.

- 3 Department of Statistics, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208, USA; email: [email protected].

- PMID: 30089228

- DOI: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102803

Systematic reviews are characterized by a methodical and replicable methodology and presentation. They involve a comprehensive search to locate all relevant published and unpublished work on a subject; a systematic integration of search results; and a critique of the extent, nature, and quality of evidence in relation to a particular research question. The best reviews synthesize studies to draw broad theoretical conclusions about what a literature means, linking theory to evidence and evidence to theory. This guide describes how to plan, conduct, organize, and present a systematic review of quantitative (meta-analysis) or qualitative (narrative review, meta-synthesis) information. We outline core standards and principles and describe commonly encountered problems. Although this guide targets psychological scientists, its high level of abstraction makes it potentially relevant to any subject area or discipline. We argue that systematic reviews are a key methodology for clarifying whether and how research findings replicate and for explaining possible inconsistencies, and we call for researchers to conduct systematic reviews to help elucidate whether there is a replication crisis.

Keywords: evidence; guide; meta-analysis; meta-synthesis; narrative; systematic review; theory.

- Guidelines as Topic

- Meta-Analysis as Topic*

- Publication Bias

- Review Literature as Topic

- Systematic Reviews as Topic*

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to write a systematic literature review [9 steps]

What is a systematic literature review?

Where are systematic literature reviews used, what types of systematic literature reviews are there, how to write a systematic literature review, 1. decide on your team, 2. formulate your question, 3. plan your research protocol, 4. search for the literature, 5. screen the literature, 6. assess the quality of the studies, 7. extract the data, 8. analyze the results, 9. interpret and present the results, registering your systematic literature review, frequently asked questions about writing a systematic literature review, related articles.

A systematic literature review is a summary, analysis, and evaluation of all the existing research on a well-formulated and specific question.

Put simply, a systematic review is a study of studies that is popular in medical and healthcare research. In this guide, we will cover:

- the definition of a systematic literature review

- the purpose of a systematic literature review

- the different types of systematic reviews

- how to write a systematic literature review

➡️ Visit our guide to the best research databases for medicine and health to find resources for your systematic review.

Systematic literature reviews can be utilized in various contexts, but they’re often relied on in clinical or healthcare settings.

Medical professionals read systematic literature reviews to stay up-to-date in their field, and granting agencies sometimes need them to make sure there’s justification for further research in an area. They can even be used as the starting point for developing clinical practice guidelines.

A classic systematic literature review can take different approaches:

- Effectiveness reviews assess the extent to which a medical intervention or therapy achieves its intended effect. They’re the most common type of systematic literature review.

- Diagnostic test accuracy reviews produce a summary of diagnostic test performance so that their accuracy can be determined before use by healthcare professionals.

- Experiential (qualitative) reviews analyze human experiences in a cultural or social context. They can be used to assess the effectiveness of an intervention from a person-centric perspective.

- Costs/economics evaluation reviews look at the cost implications of an intervention or procedure, to assess the resources needed to implement it.

- Etiology/risk reviews usually try to determine to what degree a relationship exists between an exposure and a health outcome. This can be used to better inform healthcare planning and resource allocation.

- Psychometric reviews assess the quality of health measurement tools so that the best instrument can be selected for use.

- Prevalence/incidence reviews measure both the proportion of a population who have a disease, and how often the disease occurs.

- Prognostic reviews examine the course of a disease and its potential outcomes.

- Expert opinion/policy reviews are based around expert narrative or policy. They’re often used to complement, or in the absence of, quantitative data.

- Methodology systematic reviews can be carried out to analyze any methodological issues in the design, conduct, or review of research studies.

Writing a systematic literature review can feel like an overwhelming undertaking. After all, they can often take 6 to 18 months to complete. Below we’ve prepared a step-by-step guide on how to write a systematic literature review.

- Decide on your team.

- Formulate your question.

- Plan your research protocol.

- Search for the literature.

- Screen the literature.

- Assess the quality of the studies.

- Extract the data.

- Analyze the results.

- Interpret and present the results.

When carrying out a systematic literature review, you should employ multiple reviewers in order to minimize bias and strengthen analysis. A minimum of two is a good rule of thumb, with a third to serve as a tiebreaker if needed.

You may also need to team up with a librarian to help with the search, literature screeners, a statistician to analyze the data, and the relevant subject experts.

Define your answerable question. Then ask yourself, “has someone written a systematic literature review on my question already?” If so, yours may not be needed. A librarian can help you answer this.

You should formulate a “well-built clinical question.” This is the process of generating a good search question. To do this, run through PICO:

- Patient or Population or Problem/Disease : who or what is the question about? Are there factors about them (e.g. age, race) that could be relevant to the question you’re trying to answer?

- Intervention : which main intervention or treatment are you considering for assessment?

- Comparison(s) or Control : is there an alternative intervention or treatment you’re considering? Your systematic literature review doesn’t have to contain a comparison, but you’ll want to stipulate at this stage, either way.

- Outcome(s) : what are you trying to measure or achieve? What’s the wider goal for the work you’ll be doing?

Now you need a detailed strategy for how you’re going to search for and evaluate the studies relating to your question.

The protocol for your systematic literature review should include:

- the objectives of your project

- the specific methods and processes that you’ll use

- the eligibility criteria of the individual studies

- how you plan to extract data from individual studies

- which analyses you’re going to carry out

For a full guide on how to systematically develop your protocol, take a look at the PRISMA checklist . PRISMA has been designed primarily to improve the reporting of systematic literature reviews and meta-analyses.

When writing a systematic literature review, your goal is to find all of the relevant studies relating to your question, so you need to search thoroughly .

This is where your librarian will come in handy again. They should be able to help you formulate a detailed search strategy, and point you to all of the best databases for your topic.

➡️ Read more on on how to efficiently search research databases .

The places to consider in your search are electronic scientific databases (the most popular are PubMed , MEDLINE , and Embase ), controlled clinical trial registers, non-English literature, raw data from published trials, references listed in primary sources, and unpublished sources known to experts in the field.

➡️ Take a look at our list of the top academic research databases .

Tip: Don’t miss out on “gray literature.” You’ll improve the reliability of your findings by including it.

Don’t miss out on “gray literature” sources: those sources outside of the usual academic publishing environment. They include:

- non-peer-reviewed journals

- pharmaceutical industry files

- conference proceedings

- pharmaceutical company websites

- internal reports

Gray literature sources are more likely to contain negative conclusions, so you’ll improve the reliability of your findings by including it. You should document details such as:

- The databases you search and which years they cover

- The dates you first run the searches, and when they’re updated

- Which strategies you use, including search terms

- The numbers of results obtained

➡️ Read more about gray literature .

This should be performed by your two reviewers, using the criteria documented in your research protocol. The screening is done in two phases:

- Pre-screening of all titles and abstracts, and selecting those appropriate

- Screening of the full-text articles of the selected studies

Make sure reviewers keep a log of which studies they exclude, with reasons why.

➡️ Visit our guide on what is an abstract?

Your reviewers should evaluate the methodological quality of your chosen full-text articles. Make an assessment checklist that closely aligns with your research protocol, including a consistent scoring system, calculations of the quality of each study, and sensitivity analysis.

The kinds of questions you'll come up with are:

- Were the participants really randomly allocated to their groups?

- Were the groups similar in terms of prognostic factors?

- Could the conclusions of the study have been influenced by bias?

Every step of the data extraction must be documented for transparency and replicability. Create a data extraction form and set your reviewers to work extracting data from the qualified studies.

Here’s a free detailed template for recording data extraction, from Dalhousie University. It should be adapted to your specific question.

Establish a standard measure of outcome which can be applied to each study on the basis of its effect size.

Measures of outcome for studies with:

- Binary outcomes (e.g. cured/not cured) are odds ratio and risk ratio

- Continuous outcomes (e.g. blood pressure) are means, difference in means, and standardized difference in means

- Survival or time-to-event data are hazard ratios

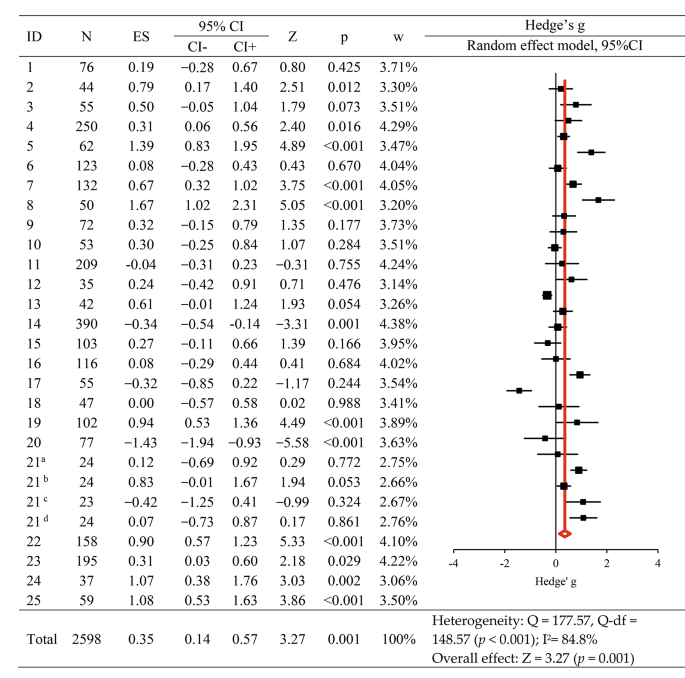

Design a table and populate it with your data results. Draw this out into a forest plot , which provides a simple visual representation of variation between the studies.

Then analyze the data for issues. These can include heterogeneity, which is when studies’ lines within the forest plot don’t overlap with any other studies. Again, record any excluded studies here for reference.

Consider different factors when interpreting your results. These include limitations, strength of evidence, biases, applicability, economic effects, and implications for future practice or research.

Apply appropriate grading of your evidence and consider the strength of your recommendations.

It’s best to formulate a detailed plan for how you’ll present your systematic review results. Take a look at these guidelines for interpreting results from the Cochrane Institute.

Before writing your systematic literature review, you can register it with OSF for additional guidance along the way. You could also register your completed work with PROSPERO .

Systematic literature reviews are often found in clinical or healthcare settings. Medical professionals read systematic literature reviews to stay up-to-date in their field and granting agencies sometimes need them to make sure there’s justification for further research in an area.

The first stage in carrying out a systematic literature review is to put together your team. You should employ multiple reviewers in order to minimize bias and strengthen analysis. A minimum of two is a good rule of thumb, with a third to serve as a tiebreaker if needed.

Your systematic review should include the following details:

A literature review simply provides a summary of the literature available on a topic. A systematic review, on the other hand, is more than just a summary. It also includes an analysis and evaluation of existing research. Put simply, it's a study of studies.

The final stage of conducting a systematic literature review is interpreting and presenting the results. It’s best to formulate a detailed plan for how you’ll present your systematic review results, guidelines can be found for example from the Cochrane institute .

JEPS Bulletin

The Official Blog of the Journal of European Psychology Students

Writing a Systematic Literature Review

Investigating concepts associated with psychology requires an indefinite amount of reading. Hence, good literature reviews are an inevitably needed part of providing the modern scientists with a broad spectrum of knowledge. In order to help, this blog post will introduce you to the basics of literature reviews and explain a specific methodological approach towards writing one, known as the systematic literature review.

Literature review is a term associated with the process of collecting, checking and (re)analysing data from the existing literature with a particular search question in mind. The latter could be for example:

- What are the effects of yoga associated with individual’s subjective well-being?

- Does brief psychotherapy produce beneficial outcomes for individuals diagnosed with agoraphobia?

- What personality traits are most commonly associated with homelessness in the modern literature?

A literature review (a) defines a specific issue, concept, theory, phenomena; (b) compiles published literature on a topic; (c) summarises critical points of current knowledge about the problem and (d) suggests next steps in addressing it.

Literature reviews can be based on all sorts of information found in scientific journals, books, academic dissertations, electronic bibliographic databases and the rest of the Internet. Electronic databases such as PsycINFO , PubMed , Web of Science could be a good starting point. Some of them, like EBSCOhost , ScienceDirect , SciELO , and ProQuest , provide full-text information, while others provide the users mostly with the abstracts of the material. Besides scientific literature, literature reviews often include the so called gray literature . This refers to the material that is either unpublished or published in non-commercial form (e.g., theses, dissertations, government reports, fact sheets, pre-prints of articles). Excluding it completely from a literature review is inappropriate because the search should be always as complete as possible in order to reduce the risk of publication bias. However, when reviewing the material on for example Google Scholar , Science.gov , Social Science Research Network , or PsycEXTRA it should be kept in mind that such search engines also display the material without peer-review and have therefore less credibility regarding the information they are disclosing.

When performing literature reviews, the use of appropriately selected terminology is essential, since it allows the researchers much clearer communication. In psychology, without some commonly agreed lists of terms, we would all get lost in the variety of concepts and vocabularies that could be applied. A typical recommendation for where to look for such index terms would be ‘ Thesaurus of Psychological Index Terms (2007) ’, which includes nearly 9,000 most commonly cross-referenced terms in psychology. In addition, electronic databases mentioned before sometimes prompt the use of the so-called Boolean operators , simple words such as AND, OR, NOT, or AND NOT. These are used for combining and/or excluding specific terms in your search and sometimes allow to obtain more focused and productive results in the search. Other tools to make search strategy more comprehensive and focused are also truncations – a tool for searching terminologies that have same initial roots (e.g., anxiety and anxious) and wildcards for words with spelling deviations (e.g., man and men). It is worth noting that the databases slightly differ in how they label the index terms and utilize specific search tools in their systems.

Among authors, there is not much coherence about different types of literature reviews but in general, most recognize at least two: traditional and systematic. The main difference between them is situated in the process of collecting and selecting data and the material for the review. Systematic literature review, as the name implies, is the more structured of the two and is thought to be more credible. On the other hand, traditional is thought to heavily depend on the researcher’s decisions regarding the data selection and, consequently, evaluation and results. Systematic protocol of the systematic literature review can be therefore understood as an optional solution for controlling the incomplete and possibly biased reports of traditional reviews.

THE SYSTEMATIC LITERATURE REVIEW

The systematic literature review is a method/process/protocol in which a body of literature is aggregated, reviewed and assessed while utilizing pre-specified and standardized techniques. In other words, to reduce bias, the rationale, the hypothesis, and the methods of data collection are prepared before the review and are used as a guide for performing the process. Just like it is for the traditional literature reviews, the goal is to identify, critically appraise, and summarize the existing evidence concerning a clearly defined problem.

Systematic literature reviews allow us to examine conflicting and/or coincident findings, as well as to identify themes that require further investigation. Furthermore, they include the possibility of evaluating consistency and generalization of the evidence regarding specific scientific questions and are, therefore, also of great practical value within the psychological field. The method is particularly useful to integrate the information of a group of studies investigating the same phenomena and it typically focuses on a very specific empirical question, such as ‘Does the Rational Emotive Therapy intervention benefit the well-being of the patients diagnosed with depression?’.

Systematic literature reviews include all (or most) of the following characteristics:

- Objectives clearly defined a priori;

- Explicit pre-defined criteria for inclusion/exclusion of the literature;

- Predetermined search strategy in the collection of the information and systematic following of the process;

- Predefined characteristic criteria applied to all the sources utilized and clearly presented in the review;

- Systematic evaluation of the quality of the studies included in the review;

- Identification of the excluded sources of literature and justification for excluding them;

- Analysis/synthesis of the information (i.e., comparison of the results, qualitative synthesis of the results, meta-analysis);

- References to the incoherences and the errors found in the selected material.

The process of performing a systematic literature review consists of several stages and can be reported in a form of an original research article with the same name (i.e., systematic literature review):

1: Start by clearly defining the objective of the review or form a structured research question.

Place in the research article: Title, Abstract, Introduction.

Example of the objective: The objective of this literature revision is to systematically review and analyse the current research on the effects of music on the anxiety levels of children in hospital settings.

Example of a structured research question: What are the most important factors associated with the development of PTSD in soldiers?

Tip: In the title, identify that the report is a systematic literature review.

2: Clearly specify the methodology of the review and define eligibility criteria (i.e., study selection criteria that the published material must meet in order to be included or excluded from the study). The search should be extensive.

Place in the research article: Methods.

Examples of inclusion criteria: Publication was an academic and peer-reviewed study. Publication was a study that examined the effects of regular physical exercise intervention on depression and included a control group.

Examples of exclusion criteria: Publication was involving male adults. Studies that also examined non-physical activities as interventions. Studies that were only published in a language other than English.

Tips: The eligibility criteria sometimes fit to be presented in tables.

3: Retrieve eligible literature and thoroughly report your search strategy throughout the process. (Ideally, the selection process is performed by at least two independent investigators.)

Example: The EBSCOhost and PsychInfo electronic databases from 2010 to 2017 were searched. These were chosen because of the psychological focus that encompasses psychosocial effects of emotional abuse in childhood. Search terms were ‘emotional abuse’, ‘childhood’, ‘psychosocial effects’, and ‘psychosocial consequences’. The EBSCOhost produced 200 results from the search criteria, while PsychInfo produced 467, for a total of 667 articles. […] Articles were rejected if it was determined from the title and the abstract that the study failed to meet the inclusion criteria. Any ambiguities regarding the application of the selection criteria were resolved through discussions between all the researchers involved.

Tip: Sometimes it is nice to represent the selection process in a graphical representation; in the form of a decision tree or a flow diagram (check PRISMA ).

4: Assess the methodological quality of the selected literature whenever possible and exclude the articles with low methodological quality. Keep in mind that the quality of the systematic review depends on the validity and the quality of the studies included in the review.

Examples of the instruments available for evaluating the quality of the studies: PEDro, Jadad scale, the lists of Delphi, OTseeker, Maastricht criteria.

Tip: Present the excluded articles as a part of the selection process mentioned in step 3.

5: Proceed with the so-called characterization of the studies. Decide which data to look for in all the selected studies and present it in a summarized way. If the information is missing in some specific paper, always register it in your reports. (Ideally, the characterization of the studies is performed by at least two independent investigators.)

Place in the research article: Results.

Examples of the information that should and/or could be collected for characterization of the literature: authors, year, sample size, study design, aims and objectives, findings/results, limitations.

Tip: Sometimes results can be presented nicely in a form of a table depicting the main characteristics.

6: Write a synthesis of the results – integrate the results of different studies and interpret them in a narrative form.

Place in the research article: Interpretation, Conclusions.

Patterns discovered as results should be summarized in a qualitative, narrative form. Modulate one (or more) general arguments for organizing the review. Some trick to help you do this is to choose two or three main information sources (e.g., articles, books, other literature reviews) to explain the results of other studies through a similar way of organization. Connect the information reported by different sources and do not just summarize the results. Find patterns in the results of different studies, identify them, address the theoretical and/or methodological conflicts and try to interpret them. Summarize the principal conclusions and evaluate the current state on the subject by pointing out possible further directions.

CONCLUSIONS

The results emerging from the data that were included in such retrospective studies can lead to a certain level of credibility regarding their conclusions. Actually, systematic literature reviews are thought to be one of our best methods to summarize and synthesize evidence about some specific research question and are often used as the main ‘practice making guidelines’ in many health care disciplines. Therefore, it is no wonder why systematic reviews are gaining popularity among researchers and why journals are moving in this direction as well. This also shows in the development of more and more specific guidelines and checklists for writing systematic literature reviews (see for example PRISMA or Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions ). To find examples of systematic literature review articles you can check Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , BioMed Central’s Systematic Reviews Journal , and PROSPERO . If you are aware of the concept of ‘registered reports’, it is worth mentioning that submitting with PROSPERO provides you with the option of publishing the latter as well. I suggest that you go through the list of useful resources provided below and hopefully, you can get enough information about anything related that remained unanswered. Now, I encourage you to try to be a little more to be systematic whenever researching some topic, to try to write a systematic literature review yourself and to maybe even consider submitting it to JEPS .

USEFUL RESOURCES

- Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews : http://www.cochranelibrary.com/cochrane-database-of-systematic-reviews/

EBSCOhost : https://search.ebscohost.com/

Google Scholar : https://scholar.google.com/

PRISMA : http://www.prisma-statement.org/

PROSPERO : https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/

ProQuest : http://www.proquest.com/

PsycEXTRA : http://www.apa.org/pubs/databases/psycextra/index.aspx :

PsycINFO : http://www.apa.org/pubs/databases/psycinfo/index.aspx

PubMed : https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/

SciELO : http://www.scielo.org/php/index.php?lang=en

Science.gov : https://www.science.gov/

ScienceDirect : http://www.sciencedirect.com/

Scorpus : http://www.scopus.com/freelookup/form/author.uri

Social Science Research Network : https://www.ssrn.com/en/

Systematic Reviews Journal (BIOMED) : https://systematicreviewsjournal.biomedcentral.com/

Web of Science : https://webofknowledge.com/

Other sources

- Sampaio, R. F., & Mancini, M. C. (2007). Systematic review studies: A guide for a careful synthesis of scientific evidence. Brasilian Journal of Physical Therapy, 11 (1), 77-82. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-35552

- Tuleya, L. G. (2007). Thesaurus of psychological index terms . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Eva Štrukelj

Eva Štrukelj is currently studying Clinical and Health Psychology at the University of Algarve in Portugal. Her main areas of interest are social psychology and health psychology. Regarding research, she is particularly curious about stigma and with it related topics.

Share this:

Related posts:.

- How to write a good literature review article?

- How to search for literature?

- Editorial perspective on scientific writing: An interview with Dr. Renata Franc

- Peer Review Process – Tips for Early Career Scientists

Systematic Review

- Library Help

- What is a Systematic Review (SR)?

Steps of a Systematic Review

- Framing a Research Question

- Developing a Search Strategy

- Searching the Literature

- Managing the Process

- Meta-analysis

- Publishing your Systematic Review

Forms and templates

Image: David Parmenter's Shop

- PICO Template

- Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

- Database Search Log

- Review Matrix

- Cochrane Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Included Studies

• PRISMA Flow Diagram - Record the numbers of retrieved references and included/excluded studies. You can use the Create Flow Diagram tool to automate the process.

• PRISMA Checklist - Checklist of items to include when reporting a systematic review or meta-analysis

PRISMA 2020 and PRISMA-S: Common Questions on Tracking Records and the Flow Diagram

- PROSPERO Template

- Manuscript Template

- Steps of SR (text)

- Steps of SR (visual)

- Steps of SR (PIECES)

Adapted from A Guide to Conducting Systematic Reviews: Steps in a Systematic Review by Cornell University Library

Source: Cochrane Consumers and Communications (infographics are free to use and licensed under Creative Commons )

Check the following visual resources titled " What Are Systematic Reviews?"

- Video with closed captions available

- Animated Storyboard

- << Previous: What is a Systematic Review (SR)?

- Next: Framing a Research Question >>

- Last Updated: May 8, 2024 1:44 PM

- URL: https://lib.guides.umd.edu/SR

- Locations and Hours

- UCLA Library

- Research Guides

- Biomedical Library Guides

Systematic Reviews

- Types of Literature Reviews

What Makes a Systematic Review Different from Other Types of Reviews?

- Planning Your Systematic Review

- Database Searching

- Creating the Search

- Search Filters and Hedges

- Grey Literature

- Managing and Appraising Results

- Further Resources

Reproduced from Grant, M. J. and Booth, A. (2009), A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26: 91–108. doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Planning Your Systematic Review >>

- Last Updated: Apr 17, 2024 2:02 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucla.edu/systematicreviews

- Open access

- Published: 17 August 2023

Data visualisation in scoping reviews and evidence maps on health topics: a cross-sectional analysis

- Emily South ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2187-4762 1 &

- Mark Rodgers 1

Systematic Reviews volume 12 , Article number: 142 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

3614 Accesses

13 Altmetric

Metrics details

Scoping reviews and evidence maps are forms of evidence synthesis that aim to map the available literature on a topic and are well-suited to visual presentation of results. A range of data visualisation methods and interactive data visualisation tools exist that may make scoping reviews more useful to knowledge users. The aim of this study was to explore the use of data visualisation in a sample of recent scoping reviews and evidence maps on health topics, with a particular focus on interactive data visualisation.

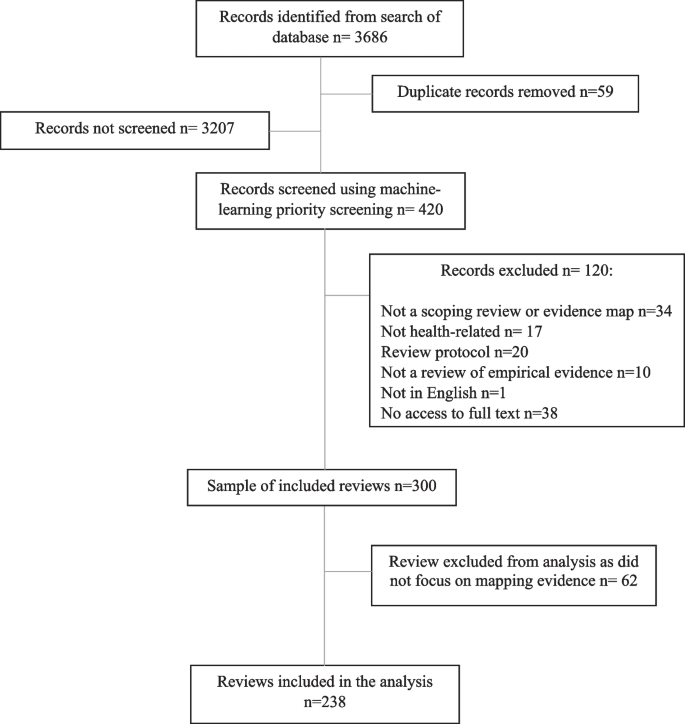

Ovid MEDLINE ALL was searched for recent scoping reviews and evidence maps (June 2020-May 2021), and a sample of 300 papers that met basic selection criteria was taken. Data were extracted on the aim of each review and the use of data visualisation, including types of data visualisation used, variables presented and the use of interactivity. Descriptive data analysis was undertaken of the 238 reviews that aimed to map evidence.

Of the 238 scoping reviews or evidence maps in our analysis, around one-third (37.8%) included some form of data visualisation. Thirty-five different types of data visualisation were used across this sample, although most data visualisations identified were simple bar charts (standard, stacked or multi-set), pie charts or cross-tabulations (60.8%). Most data visualisations presented a single variable (64.4%) or two variables (26.1%). Almost a third of the reviews that used data visualisation did not use any colour (28.9%). Only two reviews presented interactive data visualisation, and few reported the software used to create visualisations.

Conclusions

Data visualisation is currently underused by scoping review authors. In particular, there is potential for much greater use of more innovative forms of data visualisation and interactive data visualisation. Where more innovative data visualisation is used, scoping reviews have made use of a wide range of different methods. Increased use of these more engaging visualisations may make scoping reviews more useful for a range of stakeholders.

Peer Review reports

Scoping reviews are “a type of evidence synthesis that aims to systematically identify and map the breadth of evidence available on a particular topic, field, concept, or issue” ([ 1 ], p. 950). While they include some of the same steps as a systematic review, such as systematic searches and the use of predetermined eligibility criteria, scoping reviews often address broader research questions and do not typically involve the quality appraisal of studies or synthesis of data [ 2 ]. Reasons for conducting a scoping review include the following: to map types of evidence available, to explore research design and conduct, to clarify concepts or definitions and to map characteristics or factors related to a concept [ 3 ]. Scoping reviews can also be undertaken to inform a future systematic review (e.g. to assure authors there will be adequate studies) or to identify knowledge gaps [ 3 ]. Other evidence synthesis approaches with similar aims have been described as evidence maps, mapping reviews or systematic maps [ 4 ]. While this terminology is used inconsistently, evidence maps can be used to identify evidence gaps and present them in a user-friendly (and often visual) way [ 5 ].

Scoping reviews are often targeted to an audience of healthcare professionals or policy-makers [ 6 ], suggesting that it is important to present results in a user-friendly and informative way. Until recently, there was little guidance on how to present the findings of scoping reviews. In recent literature, there has been some discussion of the importance of clearly presenting data for the intended audience of a scoping review, with creative and innovative use of visual methods if appropriate [ 7 , 8 , 9 ]. Lockwood et al. suggest that innovative visual presentation should be considered over dense sections of text or long tables in many cases [ 8 ]. Khalil et al. suggest that inspiration could be drawn from the field of data visualisation [ 7 ]. JBI guidance on scoping reviews recommends that reviewers carefully consider the best format for presenting data at the protocol development stage and provides a number of examples of possible methods [ 10 ].

Interactive resources are another option for presentation in scoping reviews [ 9 ]. Researchers without the relevant programming skills can now use several online platforms (such as Tableau [ 11 ] and Flourish [ 12 ]) to create interactive data visualisations. The benefits of using interactive visualisation in research include the ability to easily present more than two variables [ 13 ] and increased engagement of users [ 14 ]. Unlike static graphs, interactive visualisations can allow users to view hierarchical data at different levels, exploring both the “big picture” and looking in more detail ([ 15 ], p. 291). Interactive visualizations are often targeted at practitioners and decision-makers [ 13 ], and there is some evidence from qualitative research that they are valued by policy-makers [ 16 , 17 , 18 ].

Given their focus on mapping evidence, we believe that scoping reviews are particularly well-suited to visually presenting data and the use of interactive data visualisation tools. However, it is unknown how many recent scoping reviews visually map data or which types of data visualisation are used. The aim of this study was to explore the use of data visualisation methods in a large sample of recent scoping reviews and evidence maps on health topics. In particular, we were interested in the extent to which these forms of synthesis use any form of interactive data visualisation.

This study was a cross-sectional analysis of studies labelled as scoping reviews or evidence maps (or synonyms of these terms) in the title or abstract.

The search strategy was developed with help from an information specialist. Ovid MEDLINE® ALL was searched in June 2021 for studies added to the database in the previous 12 months. The search was limited to English language studies only.

The search strategy was as follows:

Ovid MEDLINE(R) ALL

(scoping review or evidence map or systematic map or mapping review or scoping study or scoping project or scoping exercise or literature mapping or evidence mapping or systematic mapping or literature scoping or evidence gap map).ab,ti.

limit 1 to english language

(202006* or 202007* or 202008* or 202009* or 202010* or 202011* or 202012* or 202101* or 202102* or 202103* or 202104* or 202105*).dt.

The search returned 3686 records. Records were de-duplicated in EndNote 20 software, leaving 3627 unique records.

A sample of these reviews was taken by screening the search results against basic selection criteria (Table 1 ). These criteria were piloted and refined after discussion between the two researchers. A single researcher (E.S.) screened the records in EPPI-Reviewer Web software using the machine-learning priority screening function. Where a second opinion was needed, decisions were checked by a second researcher (M.R.).

Our initial plan for sampling, informed by pilot searching, was to screen and data extract records in batches of 50 included reviews at a time. We planned to stop screening when a batch of 50 reviews had been extracted that included no new types of data visualisation or after screening time had reached 2 days. However, once data extraction was underway, we found the sample to be richer in terms of data visualisation than anticipated. After the inclusion of 300 reviews, we took the decision to end screening in order to ensure the study was manageable.

Data extraction

A data extraction form was developed in EPPI-Reviewer Web, piloted on 50 reviews and refined. Data were extracted by one researcher (E. S. or M. R.), with a second researcher (M. R. or E. S.) providing a second opinion when needed. The data items extracted were as follows: type of review (term used by authors), aim of review (mapping evidence vs. answering specific question vs. borderline), number of visualisations (if any), types of data visualisation used, variables/domains presented by each visualisation type, interactivity, use of colour and any software requirements.

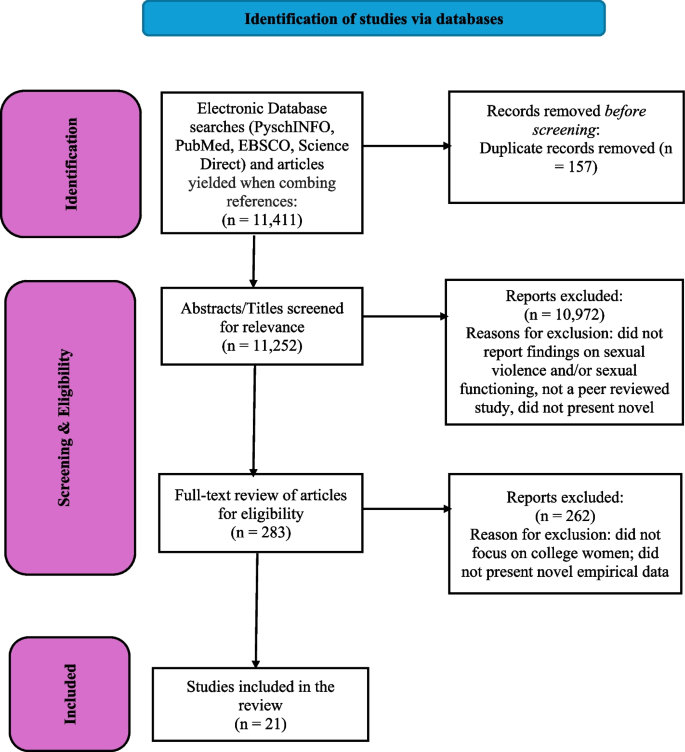

When categorising review aims, we considered “mapping evidence” to incorporate all of the six purposes for conducting a scoping review proposed by Munn et al. [ 3 ]. Reviews were categorised as “answering a specific question” if they aimed to synthesise study findings to answer a particular question, for example on effectiveness of an intervention. We were inclusive with our definition of “mapping evidence” and included reviews with mixed aims in this category. However, some reviews were difficult to categorise (for example where aims were unclear or the stated aims did not match the actual focus of the paper) and were considered to be “borderline”. It became clear that a proportion of identified records that described themselves as “scoping” or “mapping” reviews were in fact pseudo-systematic reviews that failed to undertake key systematic review processes. Such reviews attempted to integrate the findings of included studies rather than map the evidence, and so reviews categorised as “answering a specific question” were excluded from the main analysis. Data visualisation methods for meta-analyses have been explored previously [ 19 ]. Figure 1 shows the flow of records from search results to final analysis sample.

Flow diagram of the sampling process

Data visualisation was defined as any graph or diagram that presented results data, including tables with a visual mapping element, such as cross-tabulations and heat maps. However, tables which displayed data at a study level (e.g. tables summarising key characteristics of each included study) were not included, even if they used symbols, shading or colour. Flow diagrams showing the study selection process were also excluded. Data visualisations in appendices or supplementary information were included, as well as any in publicly available dissemination products (e.g. visualisations hosted online) if mentioned in papers.

The typology used to categorise data visualisation methods was based on an existing online catalogue [ 20 ]. Specific types of data visualisation were categorised in five broad categories: graphs, diagrams, tables, maps/geographical and other. If a data visualisation appeared in our sample that did not feature in the original catalogue, we checked a second online catalogue [ 21 ] for an appropriate term, followed by wider Internet searches. These additional visualisation methods were added to the appropriate section of the typology. The final typology can be found in Additional file 1 .

We conducted descriptive data analysis in Microsoft Excel 2019 and present frequencies and percentages. Where appropriate, data are presented using graphs or other data visualisations created using Flourish. We also link to interactive versions of some of these visualisations.

Almost all of the 300 reviews in the total sample were labelled by review authors as “scoping reviews” ( n = 293, 97.7%). There were also four “mapping reviews”, one “scoping study”, one “evidence mapping” and one that was described as a “scoping review and evidence map”. Included reviews were all published in 2020 or 2021, with the exception of one review published in 2018. Just over one-third of these reviews ( n = 105, 35.0%) included some form of data visualisation. However, we excluded 62 reviews that did not focus on mapping evidence from the following analysis (see “ Methods ” section). Of the 238 remaining reviews (that either clearly aimed to map evidence or were judged to be “borderline”), 90 reviews (37.8%) included at least one data visualisation. The references for these reviews can be found in Additional file 2 .

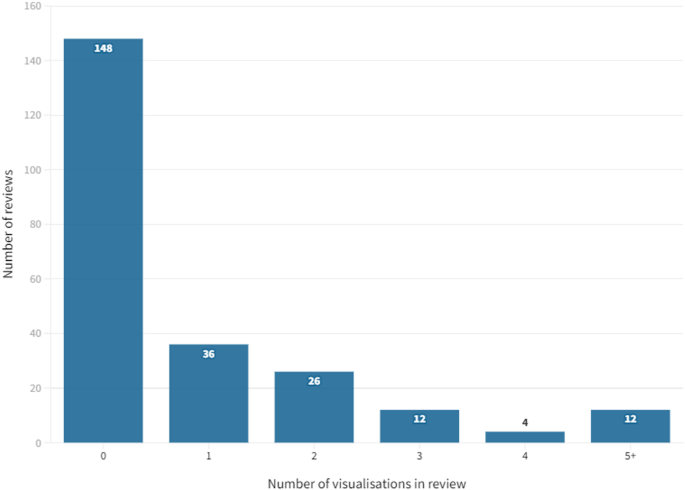

Number of visualisations

Thirty-six (40.0%) of these 90 reviews included just one example of data visualisation (Fig. 2 ). Less than a third ( n = 28, 31.1%) included three or more visualisations. The greatest number of data visualisations in one review was 17 (all bar or pie charts). In total, 222 individual data visualisations were identified across the sample of 238 reviews.

Number of data visualisations per review

Categories of data visualisation

Graphs were the most frequently used category of data visualisation in the sample. Over half of the reviews with data visualisation included at least one graph ( n = 59, 65.6%). The least frequently used category was maps, with 15.6% ( n = 14) of these reviews including a map.

Of the total number of 222 individual data visualisations, 102 were graphs (45.9%), 34 were tables (15.3%), 23 were diagrams (10.4%), 15 were maps (6.8%) and 48 were classified as “other” in the typology (21.6%).

Types of data visualisation

All of the types of data visualisation identified in our sample are reported in Table 2 . In total, 35 different types were used across the sample of reviews.

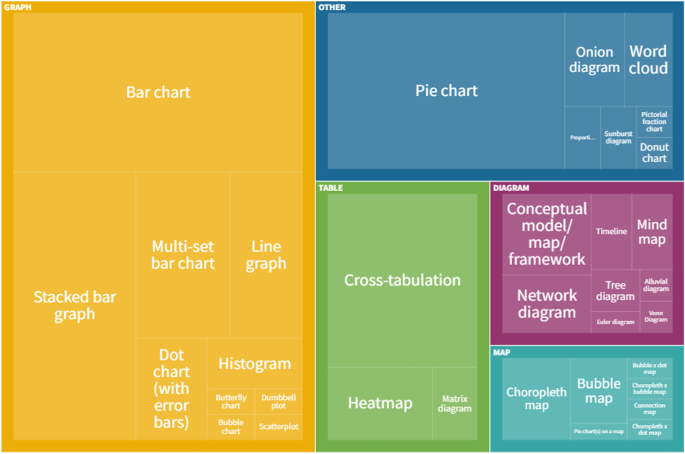

The most frequently used data visualisation type was a bar chart. Of 222 total data visualisations, 78 (35.1%) were a variation on a bar chart (either standard bar chart, stacked bar chart or multi-set bar chart). There were also 33 pie charts (14.9% of data visualisations) and 24 cross-tabulations (10.8% of data visualisations). In total, these five types of data visualisation accounted for 60.8% ( n = 135) of all data visualisations. Figure 3 shows the frequency of each data visualisation category and type; an interactive online version of this treemap is also available ( https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/9396133/ ). Figure 4 shows how users can further explore the data using the interactive treemap.

Data visualisation categories and types. An interactive version of this treemap is available online: https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/9396133/ . Through the interactive version, users can further explore the data (see Fig. 4 ). The unit of this treemap is the individual data visualisation, so multiple data visualisations within the same scoping review are represented in this map. Created with flourish.studio ( https://flourish.studio )

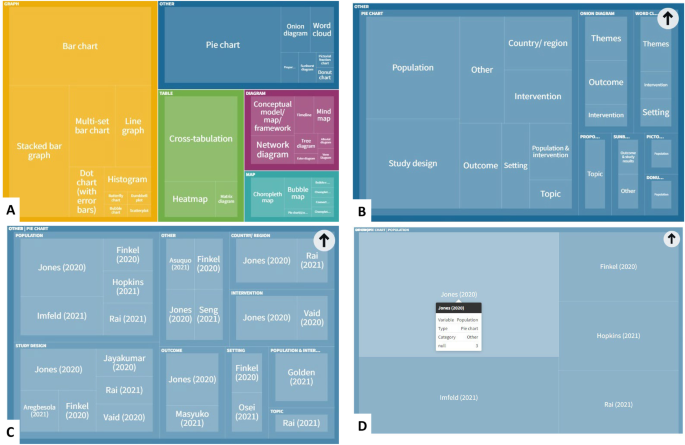

Screenshots showing how users of the interactive treemap can explore the data further. Users can explore each level of the hierarchical treemap ( A Visualisation category > B Visualisation subcategory > C Variables presented in visualisation > D Individual references reporting this category/subcategory/variable permutation). Created with flourish.studio ( https://flourish.studio )

Data presented

Around two-thirds of data visualisations in the sample presented a single variable ( n = 143, 64.4%). The most frequently presented single variables were themes ( n = 22, 9.9% of data visualisations), population ( n = 21, 9.5%), country or region ( n = 21, 9.5%) and year ( n = 20, 9.0%). There were 58 visualisations (26.1%) that presented two different variables. The remaining 21 data visualisations (9.5%) presented three or more variables. Figure 5 shows the variables presented by each different type of data visualisation (an interactive version of this figure is available online).

Variables presented by each data visualisation type. Darker cells indicate a larger number of reviews. An interactive version of this heat map is available online: https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/10632665/ . Users can hover over each cell to see the number of data visualisations for that combination of data visualisation type and variable. The unit of this heat map is the individual data visualisation, so multiple data visualisations within a single scoping review are represented in this map. Created with flourish.studio ( https://flourish.studio )

Most reviews presented at least one data visualisation in colour ( n = 64, 71.1%). However, almost a third ( n = 26, 28.9%) used only black and white or greyscale.

Interactivity

Only two of the reviews included data visualisations with any level of interactivity. One scoping review on music and serious mental illness [ 22 ] linked to an interactive bubble chart hosted online on Tableau. Functionality included the ability to filter the studies displayed by various attributes.

The other review was an example of evidence mapping from the environmental health field [ 23 ]. All four of the data visualisations included in the paper were available in an interactive format hosted either by the review management software or on Tableau. The interactive versions linked to the relevant references so users could directly explore the evidence base. This was the only review that provided this feature.

Software requirements

Nine reviews clearly reported the software used to create data visualisations. Three reviews used Tableau (one of them also used review management software as discussed above) [ 22 , 23 , 24 ]. Two reviews generated maps using ArcGIS [ 25 ] or ArcMap [ 26 ]. One review used Leximancer for a lexical analysis [ 27 ]. One review undertook a bibliometric analysis using VOSviewer [ 28 ], and another explored citation patterns using CitNetExplorer [ 29 ]. Other reviews used Excel [ 30 ] or R [ 26 ].

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic and in-depth exploration of the use of data visualisation techniques in scoping reviews. Our findings suggest that the majority of scoping reviews do not use any data visualisation at all, and, in particular, more innovative examples of data visualisation are rare. Around 60% of data visualisations in our sample were simple bar charts, pie charts or cross-tabulations. There appears to be very limited use of interactive online visualisation, despite the potential this has for communicating results to a range of stakeholders. While it is not always appropriate to use data visualisation (or a simple bar chart may be the most user-friendly way of presenting the data), these findings suggest that data visualisation is being underused in scoping reviews. In a large minority of reviews, visualisations were not published in colour, potentially limiting how user-friendly and attractive papers are to decision-makers and other stakeholders. Also, very few reviews clearly reported the software used to create data visualisations. However, 35 different types of data visualisation were used across the sample, highlighting the wide range of methods that are potentially available to scoping review authors.

Our results build on the limited research that has previously been undertaken in this area. Two previous publications also found limited use of graphs in scoping reviews. Results were “mapped graphically” in 29% of scoping reviews in any field in one 2014 publication [ 31 ] and 17% of healthcare scoping reviews in a 2016 article [ 6 ]. Our results suggest that the use of data visualisation has increased somewhat since these reviews were conducted. Scoping review methods have also evolved in the last 10 years; formal guidance on scoping review conduct was published in 2014 [ 32 ], and an extension of the PRISMA checklist for scoping reviews was published in 2018 [ 33 ]. It is possible that an overall increase in use of data visualisation reflects increased quality of published scoping reviews. There is also some literature supporting our findings on the wide range of data visualisation methods that are used in evidence synthesis. An investigation of methods to identify, prioritise or display health research gaps (25/139 included studies were scoping reviews; 6/139 were evidence maps) identified 14 different methods used to display gaps or priorities, with half being “more advanced” (e.g. treemaps, radial bar plots) ([ 34 ], p. 107). A review of data visualisation methods used in papers reporting meta-analyses found over 200 different ways of displaying data [ 19 ].

Only two reviews in our sample used interactive data visualisation, and one of these was an example of systematic evidence mapping from the environmental health field rather than a scoping review (in environmental health, systematic evidence mapping explicitly involves producing a searchable database [ 35 ]). A scoping review of papers on the use of interactive data visualisation in population health or health services research found a range of examples but still limited use overall [ 13 ]. For example, the authors noted the currently underdeveloped potential for using interactive visualisation in research on health inequalities. It is possible that the use of interactive data visualisation in academic papers is restricted by academic publishing requirements; for example, it is currently difficult to incorporate an interactive figure into a journal article without linking to an external host or platform. However, we believe that there is a lot of potential to add value to future scoping reviews by using interactive data visualisation software. Few reviews in our sample presented three or more variables in a single visualisation, something which can easily be achieved using interactive data visualisation tools. We have previously used EPPI-Mapper [ 36 ] to present results of a scoping review of systematic reviews on behaviour change in disadvantaged groups, with links to the maps provided in the paper [ 37 ]. These interactive maps allowed policy-makers to explore the evidence on different behaviours and disadvantaged groups and access full publications of the included studies directly from the map.

We acknowledge there are barriers to use for some of the data visualisation software available. EPPI-Mapper and some of the software used by reviews in our sample incur a cost. Some software requires a certain level of knowledge and skill in its use. However numerous online free data visualisation tools and resources exist. We have used Flourish to present data for this review, a basic version of which is currently freely available and easy to use. Previous health research has been found to have used a range of different interactive data visualisation software, much of which does not required advanced knowledge or skills to use [ 13 ].

There are likely to be other barriers to the use of data visualisation in scoping reviews. Journal guidelines and policies may present barriers for using innovative data visualisation. For example, some journals charge a fee for publication of figures in colour. As previously mentioned, there are limited options for incorporating interactive data visualisation into journal articles. Authors may also be unaware of the data visualisation methods and tools that are available. Producing data visualisations can be time-consuming, particularly if authors lack experience and skills in this. It is possible that many authors prioritise speed of publication over spending time producing innovative data visualisations, particularly in a context where there is pressure to achieve publications.

Limitations

A limitation of this study was that we did not assess how appropriate the use of data visualisation was in our sample as this would have been highly subjective. Simple descriptive or tabular presentation of results may be the most appropriate approach for some scoping review objectives [ 7 , 8 , 10 ], and the scoping review literature cautions against “over-using” different visual presentation methods [ 7 , 8 ]. It cannot be assumed that all of the reviews that did not include data visualisation should have done so. Likewise, we do not know how many reviews used methods of data visualisation that were not well suited to their data.

We initially relied on authors’ own use of the term “scoping review” (or equivalent) to sample reviews but identified a relatively large number of papers labelled as scoping reviews that did not meet the basic definition, despite the availability of guidance and reporting guidelines [ 10 , 33 ]. It has previously been noted that scoping reviews may be undertaken inappropriately because they are seen as “easier” to conduct than a systematic review ([ 3 ], p.6), and that reviews are often labelled as “scoping reviews” while not appearing to follow any established framework or guidance [ 2 ]. We therefore took the decision to remove these reviews from our main analysis. However, decisions on how to classify review aims were subjective, and we did include some reviews that were of borderline relevance.

A further limitation is that this was a sample of published reviews, rather than a comprehensive systematic scoping review as have previously been undertaken [ 6 , 31 ]. The number of scoping reviews that are published has increased rapidly, and this would now be difficult to undertake. As this was a sample, not all relevant scoping reviews or evidence maps that would have met our criteria were included. We used machine learning to screen our search results for pragmatic reasons (to reduce screening time), but we do not see any reason that our sample would not be broadly reflective of the wider literature.

Data visualisation, and in particular more innovative examples of it, is currently underused in published scoping reviews on health topics. The examples that we have found highlight the wide range of methods that scoping review authors could draw upon to present their data in an engaging way. In particular, we believe that interactive data visualisation has significant potential for mapping the available literature on a topic. Appropriate use of data visualisation may increase the usefulness, and thus uptake, of scoping reviews as a way of identifying existing evidence or research gaps by decision-makers, researchers and commissioners of research. We recommend that scoping review authors explore the extensive free resources and online tools available for data visualisation. However, we also think that it would be useful for publishers to explore allowing easier integration of interactive tools into academic publishing, given the fact that papers are now predominantly accessed online. Future research may be helpful to explore which methods are particularly useful to scoping review users.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Organisation formerly known as Joanna Briggs Institute

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Munn Z, Pollock D, Khalil H, Alexander L, McLnerney P, Godfrey CM, Peters M, Tricco AC. What are scoping reviews? Providing a formal definition of scoping reviews as a type of evidence synthesis. JBI Evid Synth. 2022;20:950–952.

Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Colquhoun H, Garritty CM, Hempel S, Horsley T, Langlois EV, Lillie E, O’Brien KK, Tunçalp Ӧ, et al. Scoping reviews: reinforcing and advancing the methodology and application. Syst Rev. 2021;10:263.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18:143.

Sutton A, Clowes M, Preston L, Booth A. Meeting the review family: exploring review types and associated information retrieval requirements. Health Info Libr J. 2019;36:202–22.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Miake-Lye IM, Hempel S, Shanman R, Shekelle PG. What is an evidence map? A systematic review of published evidence maps and their definitions, methods, and products. Syst Rev. 2016;5:28.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien K, Colquhoun H, Kastner M, Levac D, Ng C, Sharpe JP, Wilson K, et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16:15.

Khalil H, Peters MDJ, Tricco AC, Pollock D, Alexander L, McInerney P, Godfrey CM, Munn Z. Conducting high quality scoping reviews-challenges and solutions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;130:156–60.

Lockwood C, dos Santos KB, Pap R. Practical guidance for knowledge synthesis: scoping review methods. Asian Nurs Res. 2019;13:287–94.

Article Google Scholar

Pollock D, Peters MDJ, Khalil H, McInerney P, Alexander L, Tricco AC, Evans C, de Moraes ÉB, Godfrey CM, Pieper D, et al. Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis. 2022;10:11124.

Google Scholar

Peters MDJ GC, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco AC, Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping reviews (2020 version). In: Aromataris E MZ, editor. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI; 2020. Available from https://synthesismanual.jbi.global . Accessed 1 Feb 2023.

Tableau Public. https://www.tableau.com/en-gb/products/public . Accessed 24 January 2023.

flourish.studio. https://flourish.studio/ . Accessed 24 January 2023.