- NONFICTION BOOKS

- BEST NONFICTION 2023

- BEST NONFICTION 2024

- Historical Biographies

- The Best Memoirs and Autobiographies

- Philosophical Biographies

- World War 2

- World History

- American History

- British History

- Chinese History

- Russian History

- Ancient History (up to 500)

- Medieval History (500-1400)

- Military History

- Art History

- Travel Books

- Ancient Philosophy

- Contemporary Philosophy

- Ethics & Moral Philosophy

- Great Philosophers

- Social & Political Philosophy

- Classical Studies

- New Science Books

- Maths & Statistics

- Popular Science

- Physics Books

- Climate Change Books

- How to Write

- English Grammar & Usage

- Books for Learning Languages

- Linguistics

- Political Ideologies

- Foreign Policy & International Relations

- American Politics

- British Politics

- Religious History Books

- Mental Health

- Neuroscience

- Child Psychology

- Film & Cinema

- Opera & Classical Music

- Behavioural Economics

- Development Economics

- Economic History

- Financial Crisis

- World Economies

- Investing Books

- Artificial Intelligence/AI Books

- Data Science Books

- Sex & Sexuality

- Death & Dying

- Food & Cooking

- Sports, Games & Hobbies

- FICTION BOOKS

- BEST NOVELS 2024

- BEST FICTION 2023

- New Literary Fiction

- World Literature

- Literary Criticism

- Literary Figures

- Classic English Literature

- American Literature

- Comics & Graphic Novels

- Fairy Tales & Mythology

- Historical Fiction

- Crime Novels

- Science Fiction

- Short Stories

- South Africa

- United States

- Arctic & Antarctica

- Afghanistan

- Myanmar (Formerly Burma)

- Netherlands

- Kids Recommend Books for Kids

- High School Teachers Recommendations

- Prizewinning Kids' Books

- Popular Series Books for Kids

- BEST BOOKS FOR KIDS (ALL AGES)

- Ages Baby-2

- Books for Teens and Young Adults

- THE BEST SCIENCE BOOKS FOR KIDS

- BEST KIDS' BOOKS OF 2023

- BEST BOOKS FOR TEENS OF 2023

- Best Audiobooks for Kids

- Environment

- Best Books for Teens of 2023

- Best Kids' Books of 2023

- Political Novels

- New History Books

- New Historical Fiction

- New Biography

- New Memoirs

- New World Literature

- New Economics Books

- New Climate Books

- New Math Books

- New Philosophy Books

- New Psychology Books

- New Physics Books

- THE BEST AUDIOBOOKS

- Actors Read Great Books

- Books Narrated by Their Authors

- Best Audiobook Thrillers

- Best History Audiobooks

- Nobel Literature Prize

- Booker Prize (fiction)

- Baillie Gifford Prize (nonfiction)

- Financial Times (nonfiction)

- Wolfson Prize (history)

- Royal Society (science)

- Pushkin House Prize (Russia)

- Walter Scott Prize (historical fiction)

- Arthur C Clarke Prize (sci fi)

- The Hugos (sci fi & fantasy)

- Audie Awards (audiobooks)

Make Your Own List

Nonfiction Books » History Books » Historical Figures

The best books on alexander the great, recommended by hugh bowden.

Alexander the Great: A Very Short Introduction by Hugh Bowden

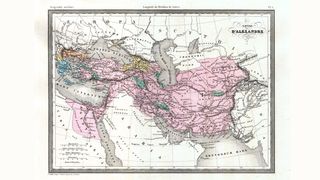

Alexander the Great never lost a battle and established an empire that stretched from the Mediterranean to the Indian subcontinent. From the earliest times, historians have argued about the nature of his achievements and what his failings were, both as a man and as a political leader. Here, Hugh Bowden , professor of ancient history at King's College London, chooses five books to help you understand the controversies, the man behind the legends, and why the legends have taken the forms they have.

Interview by Benedict King

Alexander the Great: The Anabasis and the Indica by Arrian

The History of Alexander by Quintus Curtius Rufus

The First European: A History of Alexander in the Age of Empire by Pierre Briant

The Persian Empire: A Corpus of Sources from the Achaemenid Period by Amélie Kuhrt

Fire from Heaven by Mary Renault

1 Alexander the Great: The Anabasis and the Indica by Arrian

2 the history of alexander by quintus curtius rufus, 3 the first european: a history of alexander in the age of empire by pierre briant, 4 the persian empire: a corpus of sources from the achaemenid period by amélie kuhrt, 5 fire from heaven by mary renault.

B efore we get to the books, please could you tell us about Alexander the Great’s background. What was it that led him to go out and conquer the known world?

That suggests that the huge contrast between Greece on one hand and Persia on the other, which is what Greek historians tended to focus on, and which modern scholars also often assume to be the case, wasn’t there quite so much in reality. Alexander would have been more familiar with the kind of things that went on further east.

Let’s explore how the books you’ve chosen shed light on this venture, starting with Arrian’s Alexander the Great: The Anabasis and the Indica . I think this was written in the second century AD. What sources did he use and why did he write this book?

Arrian, very helpfully, does tell us who he was getting his facts from. He relies principally on two authors. One is Ptolemy, son of Lagus, who becomes Ptolemy I, the first Ptolemaic ruler of Egypt. The other is a Greek called Aristobulus. Both of them accompanied Alexander on his campaigns.

Both of them probably wrote their accounts many decades after Alexander’s death, possibly 40 or 50 years after Alexander’s death, a generation or so later. It’s also worth saying that, although Ptolemy was there at all the battles, he probably often didn’t know what was going on. I think there’s good reason to suppose that Ptolemy actually used other histories to write his own, even though he was an eyewitness. Alexander had an official historian, or someone who is referred to as an official historian, called Callisthenes, who was later arrested, accused of plotting against Alexander and died in captivity. It may be that for the bits where Callisthenes got to before he stopped writing Ptolemy was able to use his account.

So Arrian is using these two figures. The important thing is that they were contemporaries of Alexander and they’re either using their own memory or supplementing their memory with what other contemporaries wrote. Arrian has slightly implausible explanations as to why you should trust them. He says you should trust Ptolemy’s account because Ptolemy is a king and kings don’t lie.

“I think that the modern tendency to point out how bad Alexander was probably misses the point of what historians should be doing”

A third writer on Alexander, who I didn’t choose, is Plutarch, who wrote the life of Alexander the Great round about AD 100, so a little bit before Arrian. In one or two places in his book, he mentions episodes, and lists all the historians who report the event and those who denied it happened. The most obvious one of these is when the queen of the Amazons visits Alexander. Arrian and Ptolemy both deny this happened, but others, including some who were contemporaries of Alexander, people who were there, are listed as having told this story. So, we do clearly have people, even in Alexander’s time or within living memory of Alexander, telling implausible stories about him. Arrian chooses those who don’t do that.

The other thing to say is that Arrian has probably got a particular reader in mind, and that reader is the Emperor Hadrian. Arrian knew Hadrian. Arrian was made a consul and that would have been a decision of Hadrian. Hadrian inherited an empire from his predecessor, Trajan, that reached into Mesopotamia, that included a lot the territory in which Alexander had fought. One of Hadrian’s first acts was to withdraw from the region east of the Euphrates River—so he was abandoning places Alexander had once controlled.

Part of what Arrian is doing in his book is suggesting that there were things that Alexander the Great did that were good, but there were also things Alexander did which weren’t necessarily a good idea for a wise ruler to follow. So Arrian is using Alexander as a model for how to be a king: setting up his bad points as things to avoid and his good points as things to follow.

One other important thing about Arrian is that he’s from a Greek background. He’s from a town in western Anatolia, but he’s very much a figure of Greek literature. He sat at the feet of a famous philosopher, Epictetus, and recorded his work. He wants to present Alexander in a positive light as a Greek, as a sign of how great the Greeks were in the past. This is a ‘look what the Greeks have done for us’ kind of presentation, or ‘look how glorious the ancestors of the Greeks were.’

Is he focused entirely on their military conquests or does he have a broader point to make about Greek culture?

It’s not solely about Alexander’s conquests, although his skill as a general is mentioned a lot. There are stories about Alexander’s interest in culture, sometimes suspiciously so because, for example, Arrian is not particularly keen to suggest that Alexander adopted Persian clothes, but Alexander did adopt Persian clothes and some Persian court practices. Arrian is ambivalent about these, so he does present these aspects in a bad way to some extent, but at the end he says, ‘well, he was only doing it to be a better ruler.’ Broadly speaking, Arrian wants to suggest that most of the time Alexander is moderate and it’s only occasionally that he is excessive. At the very end there’s a sort of obituary of Alexander where he sums things up and he says, amongst other things that, according to Aristobulus, Alexander only ever drank moderately. So Arrian was trying to play down the stories of Alexander getting drunk and doing things in a drunken fury, although even he shows that this happened from time to time.

So, it’s a picture of Alexander as a good character, more perhaps than Alexander as a bearer of Greek culture. But that Greekness is there in Arrian, minimising the extent to which Alexander was working within an Achaemenid Persian set up.

And is it a good read?

Let’s move on to Quintus Curtius Rufus. This book was a bit earlier, I think, and a bit more negative in its picture of Alexander the Great. Is that fair?

That’s right. We don’t know for certain when Curtius wrote, or indeed who he was. There are two possibilities: either he wrote under the emperor Vespasian in the 70s or, possibly, he wrote earlier under Claudius in the first half of the first century AD. He wrote in Latin and he was probably a senator in Rome.

The other problem we have with Curtius is that, unfortunately, the first two of the ten books of his history are missing. That’s a pity, because it means we don’t have his account of the early stages of Alexander the Great’s career. But, more significantly, it means we don’t have his introduction and we don’t have his conclusion either because there are also bits missing later on. In the beginning, in his prologue, he may well have said something about who his sources were and what his aims were in writing, but we’ve lost that.

He’s using a different source from Arrian. Scholars generally believe, although Curtius never mentions it, that he is using the work of a man called Cleitarchus who was probably writing in Alexandria in Egypt, probably about the same time as Ptolemy. But Cleitarchus was someone who had not campaigned with Alexander. So Cleitarchus is getting all this information second-hand, and it’s generally thought that Cleitarchus is more interested in fantastic stories than Plutarch and Aristobulus.

Support Five Books

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you're enjoying this interview, please support us by donating a small amount .

It’s worth saying some of these descriptions of non-Greek activity seem to be more plausible and more likely to be accurate than the alternatives. It may well be, for example, that Cleitarchus understood more about Egyptian religious rituals. All the historians give a description of Alexander visiting an oracle in the Libyan desert. The process Curtius describes sounds much more like what actually happened in Egypt than, for example, the story Arrian relates, which we know is very close to what Callisthenes said, and which is probably also what Ptolemy said, which tends to present the oracle much more like a Greek oracle.

So Cleitarchus is probably in some areas, particularly in relation to non-Greek practices, more reliable than the others.

But the other thing to say is that Curtius is writing as a Roman, a Roman senator, in a period when Roman senators were still coming to terms with autocracy. And, if he’s writing under Claudius, he’s writing in the wake of Caligula’s reign and, if he’s writing under Vespasian, then in the wake of Nero’s reign. Either way, he’s writing soon after the reign of a particularly unpopular and unsuccessful emperor with a very bad reputation, and he seems to be presenting, in the book, some of the faults of Alexander the Great as the kind of faults Caligula and Nero were accused of—arrogance, autocracy, tyranny, lack of freedom, a lack of respect for the aristocracy.

“The Macedonian monarchy was modelled, to some extent, on Persian practices or the practices of other monarchies that emulated Persia”

It’s also worth saying that Curtius is very down on the Greeks. He makes a distinction between Macedonians and Greeks and on the whole the Macedonians are mostly okay, but the Greeks are the real trouble. The Macedonian soldiery come across as sort of proto-Romans and the Greeks come across as these very problematic, wily, untrustworthy figures. I think, for Curtius, the extent to which Alexander is more Greek, and therefore less Macedonian, lies at the root of what causes him to go wrong. Curtius’ book is not short on stories about Alexander and, whereas Arrian talks about Alexander the Great’s self-restraint, Curtius keeps on talking about how he loses control of his appetites. For example, after Alexander’s first battle against Darius at Issus, Alexander captures the Persian camp followers, including all the royal household, Darius’ wife and daughters, and also Darius’ harem of 365 concubines, which gave him a different person to sleep with every day of the year. Curtius implies in his book that Alexander the Great took the harem over but says that maybe Alexander didn’t use it as frequently as Darius. Arrian doesn’t mention this at all.

He is also very keen to emphasise Alexander’s reliance on superstition, again in contrast to Arrian. Arrian has Alexander trusting a wise Greek soothsayer, called Aristander. When Alexander starts trusting the Babylonian astrologer/priests who are an important part of Babylonian royal and religious life, Curtius sees this as an indication that Alexander is succumbing to foreign superstition. He is keen to emphasise how often Alexander relies on these things and, because the Romans have a different approach to divination, Curtius is more scornful of all the divination Alexander uses and much more prepared to think that it is all trickery and fakery.

Was that kind of divination being used by contemporary Roman emperors?

Now to Pierre Briant’s The First European: A History of Alexander in the Age of Empire . This book is about Alexander the Great’s reception in the Enlightenment, isn’t it?

Just to join the gap, the first two books we were looking at are the earliest surviving, or some of the earliest surviving, narratives about Alexander the Great, even though they were written centuries after his time. In the medieval period people didn’t read the Greek texts, Greek wasn’t a language used in western Europe. Maybe Curtius was read a bit, but the dominant stories told about Alexander came from The Alexander Romance . It’s difficult to know how to describe this because it’s an evolving story that starts in Greek in the 3rd century BC, probably. We come across it in a manuscript that dates from the third century AD in Greek, but it’s translated into lots of other languages including Latin and Persian. Ultimately it goes on spreading into the modern period, so you have Scottish Alexander texts, you even have Icelandic stories about Alexander. And this is a story full of fantasy, it’s imaginative and not strict history.

And then in the Enlightenment period you start to get a return to interest in the Greek texts and in a more scientifically historical study of Alexander and this coincides with the periods of European overseas expansion. You have people writing about Alexander in the light of what French Kings like Louis XIV are doing and other European countries embarked on overseas expansion. A series of ideas about Alexander develops. Then, there’s this big change of direction after the American war of independence, with the British and French focusing more on India and indeed Persia and the growth of Russian power to the north, leaving Persia and Afghanistan as the borderlands between Russian interests and British interests.

You’ve also got, at the beginning of the 19th century, Napoleon invading Egypt and the French getting this strong brief interest in Egypt before the British move in. So, at the very end of the 18th century and in the early 19th century the modern battles of empire are taking place in the territories where Alexander had fought, and Alexander’s empire becomes an interesting model for people thinking about their world. Alexander the Great is interpreted in the light of contemporary imperial and colonial ideas and that’s what Briant talks about in this book.

The book was originally written in French and published in France and there’s quite a strong French focus to it, although when the English translation was prepared, this was balanced slightly differently. You have emphases on Alexander as a kind of scholar-King, Alexander as an advocate of trade and the creation of a commercial empire. You also have an interest in Afghanistan as this borderland between British India on the one hand and Russia on the other, and people becoming fascinated by what Alexander did in Afghanistan—where he went, and finding the places that he went to. Alexander gets tied to ideas related to the Great Game, the world of espionage between the British Empire and Russia in the second half of the 19th century.

Briant chooses to end the book talking about German interest in Alexander the Great. This is interesting, because at the time when the reunification of Germany was happening under Bismarck, you have Johann Droysen writing a history of Philip and then of Alexander. Droysen sees Philip as a Bismarck-like figure, uniting the Greeks in the way that Bismarck united the Germans, so these multiple small states are brought together in a useful empire as preparation for Alexander’s imperial achievements.

A lot of modern scholarship has tended to go back to Droysen, and what Briant does is tell the story before Droysen. If you read any modern book about Alexander the Great, although they will say that they’re going back to Arrian and Curtius and the other two or three ancient narratives, their approach is schooled by this tradition of how you write about Alexander that comes to us from Droysen. But before then you have all these other writers—French, English, Scottish—who start to create in their books this 18th- and 19th-century version of Alexander the Great that is, in many ways, the lens through which everyone who writes a biography of Alexander has tended to look.

Louis XIV and Napoleon both to some extent consciously modelled themselves on Alexander, but was there hostility to him it that era, with the widespread reluctance in the Enlightenment to glorify war?

Tell us about Amélie Kuhrt’s The Persian Empire: A Collection of Sources from the Achaemenid Period . Are any of the sources that are gathered in this book closer in time to Alexander the Great than Arrian or Curtius?

The first thing to say is that if we want to get away from the tradition of writing about Alexander the Great that Briant describes in his book, we need to take the Persian evidence seriously and to understand better the empire in which he worked and to recognise that—going back to what I said at the start—it’s not straightforwardly Western Alexander conquers Eastern Persia. It’s Alexander coming from a monarchical tradition that has been influenced by Persia. He moves in and he essentially seizes control of the Achaemenid Persian Empire and he adapts it to his purposes. The other thing to mention is the myth—and again the ancient writers like Arrian, Curtius and others are to some extent the source of this—that Persia was weak, divided, feeble and ripe for conquest. But if we look at the Persian evidence it’s much less clear that it’s as simple as that.

So, the point about Kuhrt’s very very large book is that it gives us a better picture of what Persia was like. I should say, I was torn between suggesting this and suggesting Pierre Briant’s From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire , but I thought I’d already chosen Briant’s The First European and, actually, going back to the ancient evidence is important.

“In the Enlightenment period you start to get a return to interest in the Greek texts and in a more scientifically historical study of Alexander”

The problem we have is that actually evidence about the Persian Empire mainly comes from the sixth and first half of the fifth centuries BC. The major buildings that survive, the inscriptions and other documents, of which there are quite a lot, are mostly from the early period, in particular from the time of Darius and Xerxes. By the time you get to Alexander’s period, for whatever reason, there are fewer inscriptions, or at least fewer surviving. There’s less information about what’s going on. We do have some documents written on leather in the Aramaic language from Bactria—the area of modern Afghanistan—that date from Alexander’s period and that fit in with other stuff that that’s in Kuhrt, but we have relatively little specifically about the empire under Alexander.

What Kuhrt provides us with is a clear idea of how the Empire functioned because, broadly speaking, it carried on much the same throughout the fifth and fourth centuries. Some of the material Kurt includes are Greek reports of Persia, so it’s not all Persian documents. It does include contemporary-ish Greek sources. So, we are reliant to some extent, even when we go back to the sources, on Greek perceptions of Persia. But the whole does allow us to see the Persian Empire as an efficient, well-run state with considerable resources and a highly developed organisation. It’s something that, by defeating Darius, Alexander is able to adopt and take over. And what makes it possible for him to run Persia for the brief time that he does before his death is his maintenance of Persian governmental structures and—what was controversial to people like Arrian and Curtius—his adoption of some of the practices of how to be an Achaemenid King and how he related to the Persian hierarchy by adopting these practices.

Some of the extreme practices that the Greek authors described Alexander taking up, for example getting people to prostrate themselves in front of him, are clearly a misunderstanding of Persian practice. So again, it’s useful to have documentation about the Persian Empire from earlier periods, images of what proskynesis , which Arrian thinks means prostration, actually involves. Descriptions of the practice from Herodotus, writing in the 5th century show that, as far as he was concerned, proskynesis wasn’t about prostration. So, we have these sources which help us to get a more accurate impression of what the Empire that Alexander conquered was like, written by people who were not anxious to sell a particular picture of Alexander.

You say he took over the machinery of the Persian Empire. Was he accepted by the Persians after he defeated them in battle? I mean, did the elite accept him as their monarch or did he face perpetual problems on that front?

‘Both’ is the answer. There was quite a lot of acceptance, but there was resistance, too. After the battle of Gaugamela, which was Alexander’s second and final defeat of Darius, Darius fled to Afghanistan to regroup. There he was assassinated by one of his generals, who then took the throne under the name of Artaxerxes, until he himself was subsequently captured by other Persians. Later on, after campaigning in the Indus Valley, Alexander comes back and finds that, in one or two places, the people he appointed as provincial governors have been replaced and that some of the people who have replaced them are setting themselves up as Persian King. So, there was clearly resistance, but this is from members of the elite trying to re-establish or increase their own status, rather than there being general unpopularity. Probably, for most people in the Empire, it made relatively little difference who was king.

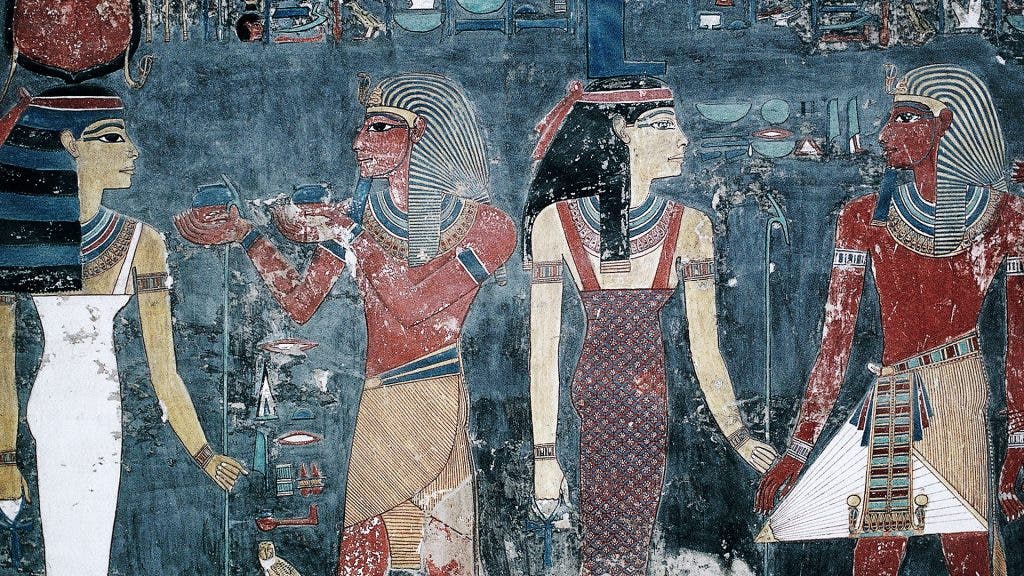

In other parts of his Empire—Egypt, for example—there seems to be no evidence of any problem with having a non-Egyptian king. They’d had that before. Alexander is presented in Egyptian temple sculptures as looking exactly like a traditional Egyptian pharaoh. Similarly, in Babylon the scholar-priests very much start operating their system to work for Alexander. So, broadly speaking, it was possible for him to slot into this new role. Inevitably there were ambitious Persians who didn’t accept it and who wanted to take power for themselves, but I think that that’s better seen as a question of individuals rather than there being a groundswell of opposition to him.

You mentioned that sources directly related to Alexander the Great are quite thin on the ground, but is the picture that the Persian sources paint of him in this book reasonably consistent with what we learn from Greek and Latin sources? Is there anything that’s radically different?

We have no actual Persian information about him. We do have some Babylonian evidence.

There’s a reasonable amount of material and it very much presents him as a typical king of Babylon. So, he’s supposed to do the rituals and they look after him in the same way that they would look after any other king. I think the answer is that, where we do have indigenous sources, which is Babylon and Egypt in particular, he comes across very much as in the mould of how a Babylonian or Egyptian king should behave. In that sense, there is a difference because this—as I was suggesting earlier—is something that the Greek and Roman sources tend to downplay. For example, there are some stories of Persians or Babylonians behaving weirdly when Alexander does something, which are probably either accidental or deliberate misreadings of more typical Babylonian or Persian practice.

Let’s move on to the final book, which is Mary Renault’s Fire from Heaven: A Novel of Alexander the Great. She’s a 20th century novelist. Tell us a bit about why you chose this.

There are quite a lot of novels about Alexander and I think that, of them all, Mary Renault’s is the most readable and the most entertaining. It’s the first of what’s called the Alexander Trilogy , although it’s a slightly odd trilogy and the third volume, Funeral Games takes place after Alexander’s death.

Mary Renault really knew her sources. She really understands the material. She has another particular interest and that’s in homosexuality. So, both in Fire from Heaven and in the second volume The Persian Boy , there’s quite a lot of focus on Alexander and male lovers. In Fire from Heaven , this is Hephaestion who, historically, probably wasn’t significant in Alexander’s life until much later, but who was at the Macedonian court. So what Renault is doing is plausible.

The reason I chose Fire from Heaven rather than The Persian Boy was partly because this is the only book I’ve chosen that depicts Alexander’s childhood. One of the other ancient sources, Plutarch, does have accounts of it and, to a significant extent, this is based on that, although Renault does much more with the material. There’s a wonderful episode when Athenian ambassadors come to Macedon and she presents a negative picture of Demosthenes, who in subsequent periods became that last hero of Greek freedom, a symbol of democracy fighting monarchy. Mary Renault’s Demosthenes is this rather unpleasant, badly spoken Greek and his rival, Aeschines, comes across as a much nicer figure and I think this is a more realistic reading of the two historical figures.

The other thing I’d say—and this sort of takes us back to Arrian—is that what authors in antiquity were doing when they wrote about Alexander was essentially telling a good story. This would include writing speeches for figures in their histories. They would base it as much as possible on the evidence. So Arrian uses Ptolemy and Aristobulus, but they would want to make it more readable and in a higher style, more impressive altogether. And that’s essentially what historical novelists do. So, although this is presented as a novel, it is, in a sense, as useful as Arrian in terms of it being a way of getting us to think about Alexander. Arrian has an agenda and Mary Renault has an agenda. Arrian is using sources and Mary Renault is using sources. Mary Renault is more similar to Arrian than most of the history books written about Alexander. They’ve both got this same interest in telling a good story and getting you to react to Alexander in a particular way.

What is the story that the book tells of Alexander the Great’s youth? What does she tell us about his formation?

She is giving us a picture of his relationship with his parents, the extent to which from an early age, he is engaged in Macedonian politics, but also—and this is where she is her most inventive—this particular interest in his relationships with his young companions, his friends and, in particular, this love story between him and Hephaestion with whom he grew up and for whom, when he died, Alexander is said to have organised extremely lavish funeral celebrations. So, it’s about his development as a character and he comes across as an attractive figure, clever and interesting, again, in contrast to a lot of a lot of modern scholarship. Modern accounts of Alexander tend to be rather negative about him, to emphasise his cruelty and tyranny. These days Curtius, with his emphasis on Alexander’s negative aspects, is a lot more fashionable than Arrian. Mary Renault is much more positive.

I think that the modern tendency to point out how bad Alexander was probably misses the point of what historians should be doing. I think it presents a way of looking at Alexander that is unhelpful. Mary Renault’s novel is possibly slightly innocent, but overall presents him as this loveable figure, I suppose, but in a serious way.

One final question, which leads on from that. Do you think Alexander would have seen himself as a success or did he die a disappointed man?

Well, he died young, from a fever while still planning his next campaign. But, I think he would have seen himself as successful. He won every battle he fought, he had successfully taken over the entire Persian Empire. Again, to be controversial, there is the story that when he reached the river Hyphasis his troops forced him to turn back and prevented him from conquering India. I share the view of those scholars who think that this is probably a myth, that Alexander never really intended to go further. He probably did want to cross the Hyphasis but was prevented by bad omens, but he would not have travelled far to the east of the river. He did march down the eastern side of the Indus when he marched down the Indus Valley and that was effectively the boundary of the Achaemenid Empire. He did get the rulers on the far side of the Indus to support him. So, I think his eastern campaign was an unmitigated success, apart from his own injuries. He had to deal with a certain amount of insurrection when he got back, but basically if his target was to take territory from the Persian king, he ended up taking the whole of the empire of the Persians and replacing the Achaemenid dynasty; so that, I think, was a success and he would have recognised it as a success.

He was probably planning to move into Arabia next. He might, had he lived longer, have campaigned further west, but essentially, I think he would have seen himself as having been successful. At the end of the Indus campaign, he has some medals struck in silver, large coins which are called decadrachms, 10 drachma pieces, and they show, on one side, Alexander on horseback fighting a man on an elephant, which is a depiction of one of his battles in India. And, on the other side, Alexander holding a thunderbolt and being crowned by a flying figure of Victory, holding a wreath over his head.

So that’s a symbol of Alexander: victorious, unconquered—a word that sources often use about him. And not only unconquered but, by holding a thunderbolt, equivalent to a god. That image presented of him as the unconquered god was not megalomaniacal, not thinking that he is immortal or anything, but recognising that he has these achievements which are huge, and that only gods and heroes, like Heracles, have ever approached. I think that image is probably how he would have thought about himself at the end of his reign.

February 14, 2020

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]

Hugh Bowden

Hugh Bowden is Professor of Ancient History at King's College London, where he has taught a wide range of topics to generations of students for over 30 years. His books include Classical Athens and the Delphic Oracle: Divination and Democracy , Mystery Cults in the Ancient World and Alexander the Great: A Very Short Introduction .

We ask experts to recommend the five best books in their subject and explain their selection in an interview.

This site has an archive of more than one thousand seven hundred interviews, or eight thousand book recommendations. We publish at least two new interviews per week.

Five Books participates in the Amazon Associate program and earns money from qualifying purchases.

© Five Books 2024

Alexander the Great Top Ten Booklist

Creating a top ten list for books on Alexander the Great is not easy, since few ancient historical figures have been written about as much. Everything from his complex personality and his sexual life to his military and logistical tactics have been analyzed by historians. Alexander, simply put, stands out as unique among ancient historical figures for having so much detailed assessment made on his life and times. Although few primary sources exist from the time of Alexander, we know a lot about him from late Antiquity sources.

Top Ten Books

Naiden, F.S. Soldier, Priest, and God: A Life of Alexander the Great . Oxford, Oxford Univesity Press. Most accounts of Alexander the Great essentially ignored the reality that he was, in addition to soldier and leader, he was also a religious figure. As information of Alexander's campaign in the Near East has come to light over the past 30 years, the religious aspects of his conquests have become clearer. Naiden's work fundamentally shifts the narrative of Alexander's life as a soldier, priest and even god.

Heckel, W., & Tritle, L. A. (Eds.). (2009). Alexander the Great: A New History . Chichester, U.K. ; Malden, Mass: Wiley-Blackwell. This work is a relatively recent revaluation of the popular themes regarding Alexander. This includes his sexuality, military style, and influences.

Cartledge, Paul (2004). Alexander the Great (1st ed) . (Overlook Press, 2004) Paul Cartledge is one of the foremost experts on Ancient Greece. His book focuses on Alexander's ambition and his military campaigns.

Arrian, Mensch, P., & Romm, J. S. (2010). The Landmark Arrian: The Campaigns of Alexander . Anabasis Alexandrous: a new translation (1st ed). New York: Pantheon Books. One of the battlefield books. This exposes in detail the 12 odd years of campaigning that Alexander took to conquer much of the known world.

Briant, Pierre (2010). Alexander the Great and his Empire: A Short Introduction . Princeton: Princeton University Press. One of the best books out there. It looks at the complex influences and history. More than the West dominating the East, Briant shows Alexander learned much from his enemies and that changed the world.

Martin, T. R., & Blackwell, C. W. (2013). Alexander the Great: The Story of an Ancient Life . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Another book that looks at the complexities of Alexander and the totality of his humanity, from warrior to deep thinker.

Engels, D. W. (2007). Alexander the Great and the Logistics of the Macedonian Army (Nachdr.). Berkeley, Calif.: Univ. of California Press. This is a great book for those interested in military warfare. An army wins through its stomach and supplies and this book explains how Alexander conquered this unseen enemy.

Related DailyHistory.org Articles

Admin and Maltaweel

Best Books Hub

Reviews of The Best Books on Every Subject

20 Best Books on Alexander The Great (2022 Review)

September 19, 2020 by James Wilson

DISCLOSURE: This post may contain affiliate links, meaning when you click the links and make a purchase, I receive a commission. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

If you’ve ever wanted to learn more about Alexander The Great including some of his past experiences and skill as a leader, there are a number of excellent books to start your research. In this article, were going to detail some of the best books that you can get your hands on about Alexander The Great. Be sure to check out these books to further your knowledge of one of the most important historical figures the world has ever known.

What are the Best Alexander The Great Books to read?

The number of books that we surveyed study Alexander The Great from a number of different perspectives. You can learn more about the way that he was as a tactician, his history as well as gain insight into his lifestyle. It is possible that you may not know much on the details of Alexander The Great and some of his upbringing, these books can help to fill in some of the blanks on his lifestyle and help you understand what made him into the man he became.

Best Alexander The Great Books: Our Top 20 Picks

Here are some of the best Alexander The Great books that you can consider to expand your knowledge on the subject:

1. The Storm Before the Storm

The Storm before the storm is a story about the beginning of the end of the Roman Republic. Written by Mike Duncan who serves as the author and narrator for the audio book, this novel explores some of the most remarkable achievements in the history of civilization through the Roman Republic.

With its founding throughout 509 B.C.E., the Republic system was a cooperative government but a series of peaceful transfers. The early stages of this government in 133 to 80 BC was a tale of bloody battles and serves as a stark warning of a grim political climate. Learning more about the beginning and the end of the Roman Republic means studying great figures like Alexander The Great who is covered in this novel.

- Authors : Mike Duncan (Author)

- Publisher : PublicAffairs; 1st Edition (October 24, 2017)

- Pages : 352 pages

2. The Virtues of War: A Novel of Alexander the Great

The virtues of war is a novel on Alexander The Great produced by Stephen press field. This examination of Alexander The Great examines his life as a soldier and the way that he was able to expand his leadership through his knowledge of working as a soldier.

This is a true story of survivorship including his many battles and the brutal assassination of his father. With details on some of the hardships that Alexander faced, we can see the motivations that drove him to conquer new lands. The Virtues war even insiders look on the lifestyle of Alexander as a soldier. As told from a close perspective, this is the journey of Alexander from soldier to a leader of men. This book can provide some unique perspective on his career and the way he developed.

- Authors : Steven Pressfield (Author)

- Publisher : Broadway; 1st edition (October 19, 2004)

- Pages : 368 pages

3. Alexander the Great

Philip Freeman created his own authoritative biography on Alexander The Great that was written for a general audience. Taking a twist on his first traditional biography on Alexander The Great, this biography explores more the impact that Alexander The Great had on history as well as the shaping of a civilization.

With his image found on Greek coins as far east as Afghanistan, the reach of Alexander The Great was mighty and this novel explains more on that reach and what made his 32 year lifespan so powerful. This general audience interpretation of Alexander the great works as a direct timeline of his various accomplishments and helps to showcase some of the changes that he was able to make in government and as a conqueror. Discover how he rose to power and how he was able to affect change across the world.

- Authors : Philip Freeman (Author)

- Publisher : Simon & Schuster (October 18, 2011)

- Pages : 416 pages

4. Alexander the Great

This Alexander The Great book by Philip Freeman studies the inquisitive mind that would serve Alexander The Great throughout his rule over Greece and throughout each of his military campaigns. As a boy that was born into a royal family in Macedonia, we can learn more about his upbringing in this novel as well as its how his inquiring mind was able to plan conquests throughout Egypt and the world.

Philip Freeman included an audio version of this novel as narrated by Michael page and it is one of the best unabridged biographies and memoirs on Alexander The Great. If you have ever been curious to find out more about the mind and inner workings of Alexander the Great, this is a book that you should highly consider as a starting point.

- Publisher : Simon & Schuster; First Edition (January 4, 2011)

5. Ghost on the Throne: The Death of Alexander the Great and the Bloody Fight for His Empire

Ghost Throne by Alexander The Great is a look into the bloody fight over his empire and the way that he died at just the age of 32. Within empire that stretched from the Adriatic Sea all the way to modern-day India, the Bloody Empire focuses in on the many aspects of Alexander The Great that have been previously unknown.

Managing his infant son, working with a mentally damaged half brother and dealing with the assassination of his father were all challenges he faced in his lifestyle. James Romm examines more than the Empires under Alexander but also the general himself. This book is a perfect perspective surrounding the empires that Alexander formed and the way that he faced challenges as he pushed further into his career.

- Authors : James Romm (Author)

- Publisher : Vintage; Illustrated Edition (November 13, 2012)

6. Alexander the Great

Alexander The Great by Robin Lane Fox is a fearless and intense look at the adventure and conquest that Alexander The Great would have taken on threat his vast empire expansion. Detailing his road to expansion up until his death in 323 B.C.E. at 32, we discover how Alexander The Great was able to expand an empire into 2,000,000 mi.² from Greece to India.

Learn more about his leadership style as well as the 18 new cities that he founded. This book details more on the cities that Alexander shaped and not so much on the man himself. The book is an expiration of the way that he expanded his empire and the various cities that he formed. If you have ever been curious as to what it would be like to live in a world dominated by conquerors or live in a city as conquered by Alexander the great, this is an excellent book to pick up.

- Authors : Robin Lane Fox (Author)

- Publisher : Penguin; Tie-In ed. Edition (October 5, 2004)

- Pages : 592 pages

7. The Nature of Alexander

The nature of Alexander is a book by Mary Renault that expands upon her acclaimed biographical research on Alexander The Great. As the previous author of fire from heaven and a Persian boy, Renault expands on her knowledge of Alexander to continue showcasing a life behind the battles and leadership.

This is a true psychological rendering of the man that was and a completely unique perspective on Alexander The Great. This perspective examines more on the mind of the leader rather than his deeds.

- Authors : Mary Renault (Author)

- Publisher : Pantheon; Illustrated Edition (November 12, 1979)

- Pages : 276 pages

8. The Dividing the Spoils: The War for Alexander the Great’s Empire (Ancient Warfare and Civilization)

Dividing the spoils is a novel about Alexander The Great empire including experts on ancient warfare and civilization. Created by Robin Waterfield, this book goes into details on the empire stretching conqueror that was Alexander The Great.

Following his footsteps including the years of war and adventure, we are able to see the path that Alexander The Great took to reach his status of glory. With an in-depth look on the many schemes and tactics that were used to help him rise to power, this is a unique look at what Alexander The Great would have to go to in order to spread his reach. This in-depth academic look dives deeper into how Alexander formed ancient civilizations and how he was able to so quickly conquer. If you are interested in seeing a window into the life of a conquering general, this is an excellent book to consider.

- Authors : Robin Waterfield (Author)

- Publisher : Oxford University Press; Illustrated Edition (November 1, 2012)

- Pages : 304 pages

9. Alexander the Great

Alexander The Great is a book published by Demi and designed for young readers. With a series of illustrative photos inside there are details of Alexander The Great conquering of India as well as his ongoing supremacy.

Alexander’s policies are explored here as well as some of the history of conquering these lands. His full life is detailed over the course of this book and a chronicling of the 12 years that he spent conquering new lands. This is an excellent way to gain perspective on this ancient leader as well as explore some of the ancient teachings of leadership that Alexander The Great had to offer. This is the perfect option for many young readers with its hearty illustrations and easy to read paragraph styles.

- Authors : Demi (Author)

- Publisher : Two Lions; Illustrated Edition (September 1, 2010)

- Pages : 64 pages

10. Alexander the Great and the Logistics of the Macedonian Army

Donald W Engels create his own first edition examination of the logistics of the Macedonian army. There’ve been multiple studies into the battle formations and tactics is used by Alexander The Great but this archaeological work as completed by the University of California examines Alexander’s strategic decisions as well as the many options that were opened Alexander The Great throughout his battle plans. Choosing a perspective of examination on what brought this ancient army to life explores battle tactics in a creative new way.

If you are seeking a more in-depth academic view of the logistics associated with commanding an army, this is a book to consider. The way that it portrays tactics and the in-depth research that was completed for this book can help you to see more into the military mind of Alexander the great and the various ways that he would’ve been responsible for managing his army.

- Authors : Donald W. Engels (Author)

- Publisher : University of California Press; First Edition (December 29, 1980)

- Pages : 208 pages

11. The Campaigns of Alexander (Penguin Classics)

The campaigns of Alexander in Penguin Classics is a book that was authored by Arrian and edited by J.R. Hamilton. The original work was produced 400 years after Alexander’s death with a detail of the campaigns of Alexander.

This is one of the most reliable accounts of the achievements of Alexander through Arrians own experiences which were translated and recorded. This is a complete work detailing the campaigns through India, Babylon and Egypt. Gain an unprecedented look at Alexander as a charismatic leader and unparalleled conqueror. This remains one of the best authorities on the many campaigns and details surrounding the expansion of Alexander the great’s empire.

- Authors : Arrian (Author), J. R. Hamilton (Editor, Introduction), Aubrey de Sélincourt (Translator)

- Publisher : Penguin Classics; Revised Edition (October 28, 1976)

- Pages : 432 pages

12. Alexander the Great: A Life From Beginning to End (Military Biographies Book 2)

Alexander The Great a life from beginning to end is a novel from hourly history that includes a complete military biography of the history of Alexander The Great. The goal of this novel is to ensure that you can gain the quick history of Alexander The Great and his many compliments in a condensed format. Available in audio and Kindle format, this is a direct look into the early life of Alexander The Great as well as the struggles that he faced at the end of his life.

If you are interested in accessing a quick knowledge of Alexander the great and learning in a condensed format, this is an excellent starting point for your journey into discovering Alexander the great.

- Authors : Hourly History (Author)

- Publisher : CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (November 16, 2017)

- Pages : 44 pages

13. Who Was Alexander the Great?

Kathryn Waterfield and Robin Waterfield created this historical book for kids to learn about one of the most interesting conquerors that ever lived. This is an excellent perspective for young readers to learn more about Alexander as a child and how he was able to learn and thrive as a leader.

The book includes interesting thoughts on leadership as well as the message for Alexander The Great and his supporters. As an easy-to-read biography, this is a tale that is appropriate for many young readers to understand the life and times of Alexander The Great. As a book that is suitable for young readers, this is one of the best introductions to the historical figure for younger historians.

- Authors : Kathryn Waterfield (Author), Robin Waterfield (Author), Who HQ (Author), Andrew Thomson (Illustrator)

- Publisher : Penguin Workshop; Illustrated Edition (June 7, 2016)

- Pages : 112 pages

14. The Generalship Of Alexander The Great

The generalship of Alexander The Great is a novel produced by JFC Fuller. This novel details the extensive life and livelihood of one of the greatest conquerors to ever live. Alexander The Great commander army of no more than 40,000 men and was able to conduct a revolutionary war effort.

In this novel, we can learn more about the nature of his governing style as well as the full extent of his ever stretching Empire. As a masterpiece on the career and military genius about Xander the great, this novel could be an excellent way to gain perspective into the past ofAlexander The Great and his efforts as a conqueror.

- Authors : J. F. C. Fuller (Author)

- Publisher : Da Capo Press (February 5, 2004)

15. Alexander the Great: His Life and His Mysterious Death

It’s been over two millennia since Alexander The Great built an empire and painted a portrait of a skilled magisterial leader.

In this novel from Anthony Everitt, we learn more about the man himself throughout his life as well as the nature of his mysterious death. As he passed away just the age of 33, the empire that he created and the science and exploration that he furthered was truly something magnificent. He continued to glorify war and committed acts of remarkable cruelty but his death remains a mystery. Some suggested that his death was covered up and he was killed by his own men, others suggest that he was felled by a fever and died of natural causes. The explanation of his death is completed quite thoroughly in this novel and is well worth an expiration to understand the nature of the time and his legacy. If you have ever wondered about the life and mysterious death of Alexander the great, this is a wonderful option to pick up to solve the mystery.

- Authors : Anthony Everitt (Author)

- Publisher : Random House; Illustrated Edition (August 27, 2019)

- Pages : 496 pages

16. Alexander the Great: Student of Aristotle, Descendant of Heroes

Alexander The Great student of Aristotle is an examination from the in60Learning team. With a complete examination into his education in a way that he was able to gain his undefeated status, we take a look at his life through the 13 years of extreme conquering and expansion as well as in the early stages before he was in the army. His parents and tutors always raised him with the idea that he had something extra to prove and this was a mindset that he continued long into his life of accomplishments.

With more details on his early life and upbringing, we can gain an appreciation of how Alexander was prepared to be one of the finest warriors and generals that the world has ever knowon.

- Authors : in60Learning (Author)

- Publisher : Independently published (February 1, 2018)

- Pages : 39 pages

17. Alexander the Great

Thomas R Martin publishes a unique perspective on the story of an ancient life with Alexander The Great. This novel explains where Alexander The Great truly earned it’s title and some of the most important aspects of his best that led to his legacy.

Learning more about what motivated him, how he succeeded and how he was able to assert judgment in difficult times are all covered in this perspective on his life. This is a true perspective that looks deep into the legacy of Alexander The Great as well as some of the driving factors that caused his need for expansion. We often hear about the details of his expansion but rarely seek definition on the reasons for his legacy and the need for his expansion. This is what makes this book so unique.

- Authors : Thomas R. Martin (Author)

- Publisher : Cambridge University Press (November 15, 2012)

18. Alexander the Great: Lessons from History’s Undefeated General (World Generals Series)

The story of Alexander The Great would suggest that the Oracle of Delphi once told him that he was invincible. In lessons from history undefeated general from Bille Yenne, we learn just how close to invincible Alexander The Great was. As the son of King Philip the second of Macedonia, Alexander The Great had a number of excellent teachers including his education from Aristotle and his command of the wing of his father’s army. By the time he was a teenager he had risen to the ranks of an astute commander.

Learning more about his past and his empire, we can see just how Alexander The Great has become one of history’s most amazing undefeated generals. This book takes a deep dive into political strategy and his command. With insights into his education and the various strategies that he used, this is a book that showcases the many ways he was able to rise to power and continue success.

- Authors : Bill Yenne (Author)

- Publisher : St. Martin’s Press; Illustrated Edition (April 13, 2010)

- Pages : 224 pages

19. Alexander The Great: Selections From Arrian, Diodorus, Plutarch, And Quintus Curtius

Alexander The Great selections from Arrian, Diodorus, Plutarch and Quintus Curtius is a collection of relevant sections from four ancient writers who were responsible for chronicling the life and accomplishments of Alexander The Great. These are some of the closest firsthand accounts of Alexander The Great’s rise to power, his historical impact as well as his conquest of Asia. This is one of the most detailed and accurate historical examples of Alexander The Great’s conquests.

The book is also filled with a series of important additions like timelines, maps, glossaries and more. All of the data in this book has been translated and produced from experts from ancient texts and it is one of the best historical accounts of the deeds of Alexander The Great.

- Authors : Arrian (Author), Diodorus Siculus (Author), Plutarch (Author), Quintus Curtius Rufus (Author), Pamela Mensch (Editor), James S. Romm (Editor)

- Publisher : Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.; paperback / softback Edition (March 15, 2005)

20. Leadership & Strategy: Lessons From Alexander The Great

Leadership and strategy is a book that is written by Leonardo P. Martino and it serves as a quintessential guide from a business perspective on lessons from Alexander The Great.

As an unmatched leader for nearly 2000 years, Alexander has some of the greatest demonstrations of leadership and strength from any modern leader. His behaviors and traits have become increasingly more relevant for the modern business world and this could be a book that could teach you some of the most important aspects of Alexander The Great that you could adopt into your own lifestyle. If you have ever been curious about the nature of Alexander the Great and adopting some of his own leadership strategies into your life, this could be an excellent novel to consider.

- Authors : Leandro P. Martino (Author)

- Publisher : BookSurge Publishing (February 14, 2008)

- Pages : 273 pages

Choosing the Best Alexander The Great Books

If you are interested in learning more about Alexander The Great, any of these top books can be the perfect starting point. There is a wealth of knowledge that you can draw from on this subject with first-hand accounts from ancient historians all the way to modern historical looks at Alexander The Great. Whether you’re curious in the mysterious cause of his death or in the lifestyle that Alexander The Great lived, these are some excellent ways that you can start your research and gain a newfound perspective on Alexander The Great.

Subscribe To Email List

FREE Great Book Recommendations

Don't Miss Out On Books You Must Read

We won't send you spam. Unsubscribe at any time

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Beginnings of the Persian expedition

Asia minor and the battle of issus, conquest of the mediterranean coast and egypt, campaign eastward to central asia, invasion of india, consolidation of the empire.

Why is Alexander the Great famous?

What was alexander the great’s childhood like, how did alexander the great die, what was alexander the great like.

- What is imperialism in history?

Alexander the Great

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Constitutional Rights Foundation - The Legacy of Alexander the Great

- Chemistry LibreTexts - The Legacy of Alexander the Great

- National Center for Biotechnology Information - PubMed Central - Historical Perspective and Medical Maladies of Alexander the Great

- Live Science - Alexander the Great: Facts, biography and accomplishments

- JewishEncyclopedia.com - Alexander, King of Greece

- JewishEncyclopedia.com - Alexander The Great

- Social Studies for Kids - Biography of Alexander the Great

- Khan Academy - Alexander the Great

- Livius - Biography of Alexander the Great

- PBS LearningMedia - The Rise of Alexander the Great

- World History Encyclopedia - Biography of Alexander the Great

- Alexander the Great - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Alexander the Great - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

Although king of ancient Macedonia for less than 13 years, Alexander the Great changed the course of history. One of the world’s greatest military generals, he created a vast empire that stretched from Macedonia to Egypt and from Greece to part of India. This allowed for Hellenistic culture to become widespread.

Alexander was the son of Philip II and Olympias (daughter of King Neoptolemus of Epirus). From age 13 to 16 he was taught by the Greek philosopher Aristotle , who inspired his interest in philosophy, medicine, and scientific investigation. As a teenager, Alexander became known for his exploits on the battlefield.

While in Babylon , Alexander became ill after a prolonged banquet and drinking bout, and on June 13, 323, he died at age 33. There was much speculation about the cause of death, and the most popular theories claim that he either contracted malaria or typhoid fever or that he was poisoned.

While he could be ruthless and impulsive, Alexander was also charismatic and sensible. His troops were extremely loyal, believing in him throughout all hardships. Hugely ambitious, Alexander drew inspiration from the gods Achilles , Heracles , and Dionysus . He also displayed a deep interest in learning and encouraged the spread of Hellenistic culture.

Recent News

Alexander the Great (born 356 bce , Pella, Macedonia [northwest of Thessaloníki, Greece]—died June 13, 323 bce , Babylon [near Al-Ḥillah, Iraq]) was the king of Macedonia (336–323 bce ), who overthrew the Persian empire , carried Macedonian arms to India , and laid the foundations for the Hellenistic world of territorial kingdoms. Already in his lifetime the subject of fabulous stories, he later became the hero of a full-scale legend bearing only the sketchiest resemblance to his historical career.

He was born in 356 bce at Pella in Macedonia, the son of Philip II and Olympias (daughter of King Neoptolemus of Epirus ). From age 13 to 16 he was taught by Aristotle , who inspired him with an interest in philosophy , medicine , and scientific investigation , but he was later to advance beyond his teacher’s narrow precept that non-Greeks should be treated as slaves. Left in charge of Macedonia in 340 during Philip’s attack on Byzantium , Alexander defeated the Maedi, a Thracian people. Two years later he commanded the left wing at the Battle of Chaeronea , in which Philip defeated the allied Greek states, and displayed personal courage in breaking the Sacred Band of Thebes , an elite military corps composed of 150 pairs of lovers. A year later Philip divorced Olympias, and, after a quarrel at a feast held to celebrate his father’s new marriage, Alexander and his mother fled to Epirus, and Alexander later went to Illyria . Shortly afterward, father and son were reconciled and Alexander returned, but his position as heir was jeopardized.

In 336, however, on Philip’s assassination , Alexander, acclaimed by the army, succeeded without opposition. He at once executed the princes of Lyncestis, alleged to be behind Philip’s murder, along with all possible rivals and the whole of the faction opposed to him. He then marched south, recovered a wavering Thessaly , and at an assembly of the Greek League of Corinth was appointed generalissimo for the forthcoming invasion of Asia , already planned and initiated by Philip. Returning to Macedonia by way of Delphi (where the Pythian priestess acclaimed him “invincible”), he advanced into Thrace in spring 335 and, after forcing the Shipka Pass and crushing the Triballi , crossed the Danube to disperse the Getae ; turning west, he then defeated and shattered a coalition of Illyrians who had invaded Macedonia. Meanwhile, a rumour of his death had precipitated a revolt of Theban democrats; other Greek states favoured Thebes , and the Athenians , urged on by Demosthenes , voted help. In 14 days Alexander marched 240 miles from Pelion (near modern Korçë , Albania ) in Illyria to Thebes. When the Thebans refused to surrender, he made an entry and razed their city to the ground, sparing only temples and Pindar ’s house; 6,000 were killed and all survivors sold into slavery . The other Greek states were cowed by this severity, and Alexander could afford to treat Athens leniently. Macedonian garrisons were left in Corinth , Chalcis , and the Cadmea (the citadel of Thebes).

From his accession Alexander had set his mind on the Persian expedition . He had grown up to the idea. Moreover, he needed the wealth of Persia if he was to maintain the army built by Philip and pay off the 500 talents he owed. The exploits of the Ten Thousand, Greek soldiers of fortune, and of Agesilaus of Sparta , in successfully campaigning in Persian territory had revealed the vulnerability of the Persian empire . With a good cavalry force Alexander could expect to defeat any Persian army. In spring 334 he crossed the Dardanelles , leaving Antipater , who had already faithfully served his father, as his deputy in Europe with over 13,000 men; he himself commanded about 30,000 foot and over 5,000 cavalry, of whom nearly 14,000 were Macedonians and about 7,000 allies sent by the Greek League. This army was to prove remarkable for its balanced combination of arms. Much work fell on the lightarmed Cretan and Macedonian archers, Thracians, and the Agrianian javelin men. But in pitched battle the striking force was the cavalry , and the core of the army, should the issue still remain undecided after the cavalry charge, was the infantry phalanx , 9,000 strong, armed with 13-foot spears and shields, and the 3,000 men of the royal battalions, the hypaspists. Alexander’s second in command was Parmenio , who had secured a foothold in Asia Minor during Philip’s lifetime; many of his family and supporters were entrenched in positions of responsibility. The army was accompanied by surveyors, engineers, architects, scientists, court officials, and historians; from the outset Alexander seems to have envisaged an unlimited operation.

After visiting Ilium ( Troy ), a romantic gesture inspired by Homer , he confronted his first Persian army, led by three satraps , at the Granicus (modern Kocabaş) River, near the Sea of Marmara (May/June 334). The Persian plan to tempt Alexander across the river and kill him in the melee almost succeeded; but the Persian line broke, and Alexander’s victory was complete. Darius ’s Greek mercenaries were largely massacred, but 2,000 survivors were sent back to Macedonia in chains. This victory exposed western Asia Minor to the Macedonians, and most cities hastened to open their gates. The tyrants were expelled and (in contrast to Macedonian policy in Greece) democracies were installed. Alexander thus underlined his Panhellenic policy, already symbolized in the sending of 300 panoplies (sets of armour) taken at the Granicus as an offering dedicated to Athena at Athens by “Alexander son of Philip and the Greeks (except the Spartans) from the barbarians who inhabit Asia.” (This formula, cited by the Greek historian Arrian in his history of Alexander’s campaigns, is noteworthy for its omission of any reference to Macedonia.) But the cities remained de facto under Alexander, and his appointment of Calas as satrap of Hellespontine Phrygia reflected his claim to succeed the Great King of Persia. When Miletus , encouraged by the proximity of the Persian fleet, resisted, Alexander took it by assault, but, refusing a naval battle, he disbanded his own costly navy and announced that he would “defeat the Persian fleet on land,” by occupying the coastal cities. In Caria , Halicarnassus resisted and was stormed, but Ada , the widow and sister of the satrap Idrieus, adopted Alexander as her son and, after expelling her brother Pixodarus, Alexander restored her to her satrapy. Some parts of Caria held out, however, until 332.

In winter 334–333 Alexander conquered western Asia Minor, subduing the hill tribes of Lycia and Pisidia , and in spring 333 he advanced along the coastal road to Perga , passing the cliffs of Mount Climax, thanks to a fortunate change of wind. The fall in the level of the sea was interpreted as a mark of divine favour by Alexander’s flatterers, including the historian Callisthenes . At Gordium in Phrygia , tradition records his cutting of the Gordian knot , which could only be loosed by the man who was to rule Asia; but this story may be apocryphal or at least distorted. At this point Alexander benefitted from the sudden death of Memnon , the competent Greek commander of the Persian fleet. From Gordium he pushed on to Ancyra (modern Ankara ) and thence south through Cappadocia and the Cilician Gates (modern Külek Boğazi); a fever held him up for a time in Cilicia . Meanwhile, Darius with his Grand Army had advanced northward on the eastern side of Mount Amanus. Intelligence on both sides was faulty, and Alexander was already encamped by Myriandrus (near modern İskenderun , Turkey ) when he learned that Darius was astride his line of communications at Issus , north of Alexander’s position (autumn 333). Turning, Alexander found Darius drawn up along the Pinarus River. In the battle that followed, Alexander won a decisive victory. The struggle turned into a Persian rout and Darius fled, leaving his family in Alexander’s hands; the women were treated with chivalrous care.

From Issus Alexander marched south into Syria and Phoenicia , his object being to isolate the Persian fleet from its bases and so to destroy it as an effective fighting force. The Phoenician cities Marathus and Aradus came over quietly, and Parmenio was sent ahead to secure Damascus and its rich booty, including Darius ’s war chest. In reply to a letter from Darius offering peace, Alexander replied arrogantly, recapitulating the historic wrongs of Greece and demanding unconditional surrender to himself as lord of Asia. After taking Byblos (modern Jubayl) and Sidon (Arabic Ṣaydā), he met with a check at Tyre , where he was refused entry into the island city. He thereupon prepared to use all methods of siegecraft to take it, but the Tyrians resisted, holding out for seven months. In the meantime (winter 333–332) the Persians had counterattacked by land in Asia Minor—where they were defeated by Antigonus , the satrap of Greater Phrygia—and by sea, recapturing a number of cities and islands.

While the siege of Tyre was in progress, Darius sent a new offer: he would pay a huge ransom of 10,000 talents for his family and cede all his lands west of the Euphrates . “I would accept,” Parmenio is reported to have said, “were I Alexander”; “I too,” was the famous retort, “were I Parmenio.” The storming of Tyre in July 332 was Alexander’s greatest military achievement; it was attended with great carnage and the sale of the women and children into slavery . Leaving Parmenio in Syria, Alexander advanced south without opposition until he reached Gaza on its high mound; there bitter resistance halted him for two months, and he sustained a serious shoulder wound during a sortie. There is no basis for the tradition that he turned aside to visit Jerusalem .

In November 332 he reached Egypt . The people welcomed him as their deliverer, and the Persian satrap Mazaces wisely surrendered. At Memphis Alexander sacrificed to Apis , the Greek term for Hapi, the sacred Egyptian bull, and was crowned with the traditional double crown of the pharaohs ; the native priests were placated and their religion encouraged. He spent the winter organizing Egypt , where he employed Egyptian governors, keeping the army under a separate Macedonian command. He founded the city of Alexandria near the western arm of the Nile on a fine site between the sea and Lake Mareotis, protected by the island of Pharos, and had it laid out by the Rhodian architect Deinocrates. He is also said to have sent an expedition to discover the causes of the flooding of the Nile. From Alexandria he marched along the coast to Paraetonium and from there inland to visit the celebrated oracle of the god Amon (at Sīwah ); the difficult journey was later embroidered with flattering legends . On his reaching the oracle in its oasis , the priest gave him the traditional salutation of a pharaoh , as son of Amon; Alexander consulted the god on the success of his expedition but revealed the reply to no one. Later the incident was to contribute to the story that he was the son of Zeus and, thus, to his “deification.” In spring 331 he returned to Tyre, appointed a Macedonian satrap for Syria, and prepared to advance into Mesopotamia . His conquest of Egypt had completed his control of the whole eastern Mediterranean coast.

In July 331 Alexander was at Thapsacus on the Euphrates . Instead of taking the direct route down the river to Babylon , he made across northern Mesopotamia toward the Tigris , and Darius, learning of this move from an advance force sent under Mazaeus to the Euphrates crossing, marched up the Tigris to oppose him. The decisive battle of the war was fought on October 31, on the plain of Gaugamela between Nineveh and Arbela. Alexander pursued the defeated Persian forces for 35 miles to Arbela, but Darius escaped with his Bactrian cavalry and Greek mercenaries into Media .

Alexander now occupied Babylon , city and province; Mazaeus, who surrendered it, was confirmed as satrap in conjunction with a Macedonian troop commander, and quite exceptionally was granted the right to coin . As in Egypt, the local priesthood was encouraged. Susa , the capital, also surrendered, releasing huge treasures amounting to 50,000 gold talents; here Alexander established Darius’s family in comfort. Crushing the mountain tribe of the Ouxians, he now pressed on over the Zagros range into Persia proper and, successfully turning the Pass of the Persian Gates, held by the satrap Ariobarzanes , he entered Persepolis and Pasargadae . At Persepolis he ceremonially burned down the palace of Xerxes , as a symbol that the Panhellenic war of revenge was at an end; for such seems the probable significance of an act that tradition later explained as a drunken frolic inspired by Thaïs , an Athenian courtesan. In spring 330 Alexander marched north into Media and occupied its capital. The Thessalians and Greek allies were sent home; henceforward he was waging a purely personal war.

As Mazaeus’s appointment indicated, Alexander’s views on the empire were changing. He had come to envisage a joint ruling people consisting of Macedonians and Persians, and this served to augment the misunderstanding that now arose between him and his people. Before continuing his pursuit of Darius, who had retreated into Bactria , he assembled all the Persian treasure and entrusted it to Harpalus , who was to hold it at Ecbatana as chief treasurer. Parmenio was also left behind in Media to control communications; the presence of this older man had perhaps become irksome.

In midsummer 330 Alexander set out for the eastern provinces at a high speed via Rhagae (modern Rayy , near Tehrān ) and the Caspian Gates, where he learned that Bessus , the satrap of Bactria, had deposed Darius. After a skirmish near modern Shāhrūd, the usurper had Darius stabbed and left him to die. Alexander sent his body for burial with due honours in the royal tombs at Persepolis.

Darius ’s death left no obstacle to Alexander’s claim to be Great King, and a Rhodian inscription of this year (330) calls him “lord of Asia”—i.e., of the Persian empire; soon afterward his Asian coins carry the title of king. Crossing the Elburz Mountains to the Caspian , he seized Zadracarta in Hyrcania and received the submission of a group of satraps and Persian notables, some of whom he confirmed in their offices; in a diversion westward, perhaps to modern Āmol , he reduced the Mardi, a mountain people who inhabited the Elburz Mountains. He also accepted the surrender of Darius’s Greek mercenaries. His advance eastward was now rapid. In Aria he reduced Satibarzanes, who had offered submission only to revolt, and he founded Alexandria of the Arians (modern Herāt ). At Phrada in Drangiana (either near modern Nad-e ʿAli in Seistan or farther north at Farah ), he at last took steps to destroy Parmenio and his family. Philotas , Parmenio’s son, commander of the elite Companion cavalry, was implicated in an alleged plot against Alexander’s life, condemned by the army, and executed; and a secret message was sent to Cleander , Parmenio’s second in command, who obediently assassinated him. This ruthless action excited widespread horror but strengthened Alexander’s position relative to his critics and those whom he regarded as his father’s men. All Parmenio’s adherents were now eliminated and men close to Alexander promoted. The Companion cavalry was reorganized in two sections, each containing four squadrons (now known as hipparchies); one group was commanded by Alexander’s oldest friend, Hephaestion , the other by Cleitus , an older man. From Phrada, Alexander pressed on during the winter of 330–329 up the valley of the Helmand River , through Arachosia , and over the mountains past the site of modern Kābul into the country of the Paropamisadae, where he founded Alexandria by the Caucasus .