Philosophy Break Your home for learning about philosophy

Introductory philosophy courses distilling the subject's greatest wisdom.

Reading Lists

Curated reading lists on philosophy's best and most important works.

Latest Breaks

Bite-size philosophy articles designed to stimulate your brain.

Friedrich Nietzsche The Best 9 Books to Read

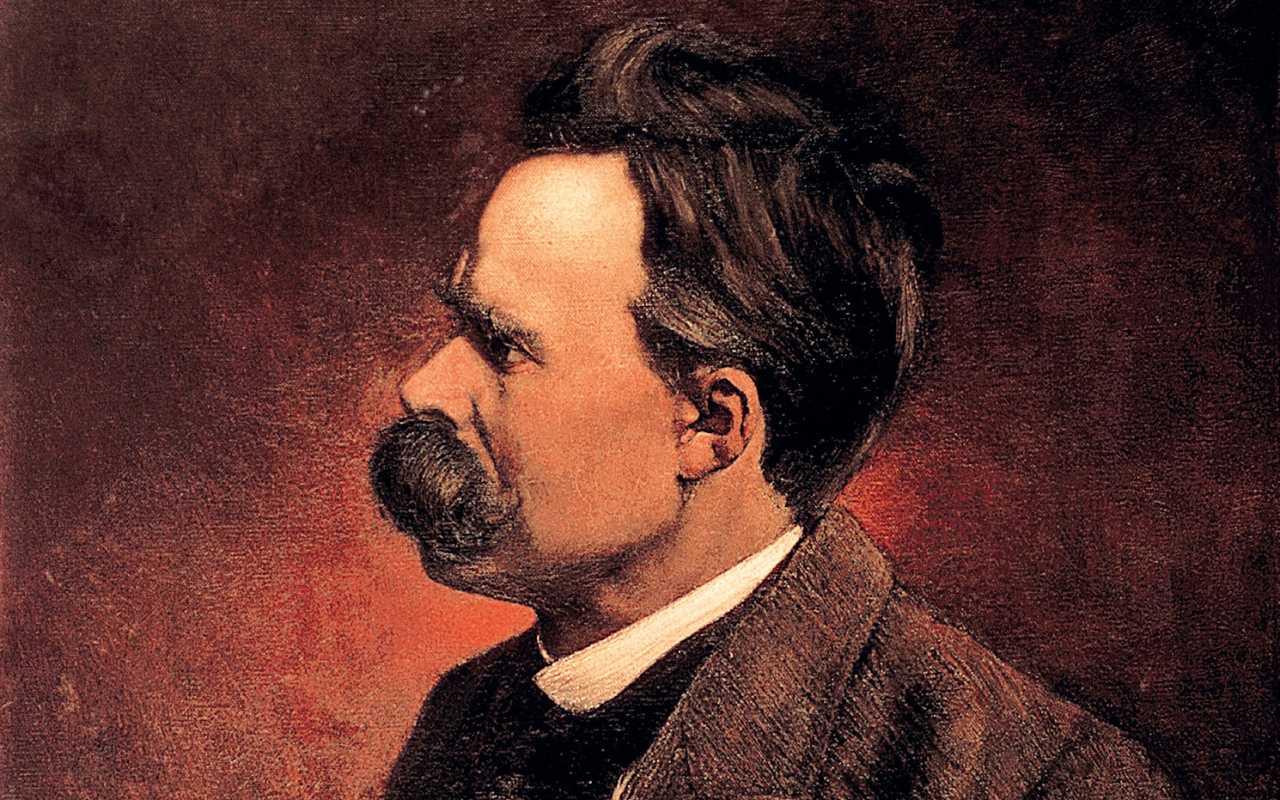

F riedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) was a 19th-century German philosopher who, though hardly read during his own (sane) lifetime, has become a dominant intellectual force in today’s popular culture.

Perhaps best known for his proclamation that God is dead , along with his critique of conventional morality and religion, Nietzsche is remembered for his attempt to establish what he called a ‘revaluation of all values’, and is celebrated for his brilliant, provocative aphorisms and idea-packed prose (which includes, for instance, his vision of the Übermensch , his distinction between the Apollonian and Dionysian , his presentation of the eternal recurrence , amor fati , and all of the 97 clever Nietzsche passages and quotations we’ve collated here ).

Accordingly, Nietzsche’s reputation in the English-speaking world is now arguably the highest it’s ever been, and his place in philosophy’s canon looks assured.

However, it wasn’t always this way. After suffering a mental breakdown in 1889 from which he never recovered, Nietzsche (and his works) came under the care of his sister, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, who was a bigoted anti-Semite.

Elisabeth warped Nietzsche’s unpublished notebooks and unfinished works (now collected in The Will to Power ) into a bloodthirsty call to arms for nationalist Germany, which aligned to the blueprint for Hitler’s ‘superior’ Aryan race.

For a long time, therefore, Nietzsche’s ideas were synonymous with those of Nazism.

Thankfully, the truth of Elisabeth’s tampering emerged — as did letters and earlier works evidencing Nietzsche’s fierce opposition to nationalism and antisemitism.

Following the Nazi defeat in World War II, efforts were made to sanitize Nietzsche’s name, not least by the philosopher, translator, and poet Walter Kaufmann.

Kaufmann recognized that Nietzsche was majorly misunderstood in the English-speaking world, and set out on a long-term campaign to not only provide new English translations of all of Nietzsche’s works, but also guide readers in better understanding the profundity of his ideas.

(For more on the key events of Nietzsche’s life and legacy, including his tragic descent into insanity, see our overview of Nietzsche’s life, insanity, and legacy , which places his philosophy in the context of his life and illness, ultimately suggesting that Nietzsche’s task in both his personal life and his wider philosophy were one and the same: to find meaning in suffering , to make recovery more predominant than resentment, and to establish a solution to the problem of nihilism.)

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox:

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

Even enjoying a resurgence in popularity, however, Nietzsche’s philosophy remains commonly misunderstood, misread, and misappropriated by those from all over the political and philosophical spectrum, who wish to elevate their particular cause with the power of his rhetoric.

With a range of thinking so widespread, and a style of writing so stunningly and wickedly provocative, it is perhaps no surprise that Nietzsche’s iconoclastic, hammering utterances — designed to jolt people out of presuppositions — can be so grossly taken out of context.

Here is a thinker who not only changes his mind on key topics throughout his active philosophical period, but who at times suggests he doesn’t want to be understood, not to be purposefully oblique, but because he thinks his readers are not yet ready for what he has to say.

The difficulties of reading Nietzsche

G etting into Nietzsche, then — i.e. really understanding and appreciating his philosophy, rather than just a few of his most famous quotations — can be somewhat of a challenge.

For, far from helping his readers by clearly laying out his ideas in rigid, structured form, Nietzsche prefers to challenge us by scattering his great ideas across his works — often offering only hints and winks about what he truly thinks, and occasionally contradicting himself or reevaluating earlier ideas.

Nietzsche also primarily adopts an aphoristic writing style — presenting us with a numbered sequence of rather disconnected sentences and paragraphs across a whole range of different subjects, sometimes held together by a particular theme, sometimes not.

There may be a paragraph from an 1881 work that aligns to something he then expands on in an 1887 work, for example.

Nietzsche also writes in such a way whereby he assumes you’ve read everything he’s ever written — as well as every major Western thinker from the ancient pre-Socratic Greeks onwards.

Which is the best Nietzsche book to start with?

G iven the quirks involved in reading him, selecting a ‘first’ Nietzsche book can be tricky. While they all contain diamonds, and while his writing style is always stunningly engaging, there is perhaps no ‘single’ work of his that stands out as an easy gateway to his ideas.

That said, some are certainly better candidates than others.

As we discuss below, his 1889 work Twilight of the Idols , for instance, is often recommended as a better starting point than most, for Nietzsche attempts to offer short summaries of his mature philosophy.

The 1887 On the Genealogy of Morals , too, can be a more accessible first read than others, in that Nietzsche foregoes his aphoristic style for the production of three longer-form essays, making for a more conventional initial reading experience (though, for first-time Nietzsche readers, understanding the subject matter will most definitely be a challenge without the assistance of some secondary literature, the best of which we outline below).

Perhaps the worst route into Nietzsche’s thinking, meanwhile, is the one most commonly taken: starting with his most famous book, Thus Spoke Zarathustra , written between 1883 and 1885.

While Thus Spoke Zarathustra is a stunning literary achievement, it is not the best way to learn about Nietzsche’s ideas, for it is more a densely cryptic expression of them in poetic, lyrical form.

Another common approach is to start with Nietzsche’s first book, The Birth of Tragedy — but this is also not recommended.

While the germ for many of his later ideas can be found in The Birth of Tragedy , on the whole it is not representative of his most important contributions to philosophy, for Nietzsche’s style and ideas develop considerably in his later works.

Nietzsche: the best 9 books to read

T aking into account all of the above, the below reading list consists of the best and most essential books for those looking to understand more about Nietzsche and his fascinating philosophy.

It contains a mix of both primary and secondary literature, for although Nietzsche’s words always make for a brilliantly entertaining read themselves, tying together Nietzsche’s ideas — scattered as they are across his works — can be a real challenge.

Indeed, if you’re interested in learning about Nietzsche as a first-time reader of his books, the power of his ideas is more accessible when contextualized by scholars whose life’s work has been dedicated to understanding him.

Without further ado, let’s dive in!

1. I Am Dynamite! By Sue Prideaux

I Am Dynamite!

BY SUE PRIDEAUX

This is the biography on Nietzsche we’ve been waiting for. Winner of The Times Biography of the year in 2019, Sue Prideaux’s I Am Dynamite! is a vividly compelling, myth-shattering portrait of one of history’s most misunderstood philosophers.

Prideaux illuminates all the events that shaped Nietzsche’s thinking, his key relationships — including those with the composer Richard Wagner and psychoanalyst Lou Salomé — as well as his heart-breaking descent into madness.

If you want to understand how the life Nietzsche lived led to the production of his philosophy, this is the biography for you.

2. Nietzsche on Morality, by Brian Leiter

Nietzsche on Morality

BY BRIAN LEITER

Both an introduction to and a sustained commentary on Nietzsche’s moral philosophy, Brian Leiter’s 2002 book Nietzsche on Morality has become one of the most widely used and debated secondary sources on Nietzsche over the past two decades.

Focusing on morality but touching on related topics too, Nietzsche on Morality is a solid overview and critique for anyone interested in Nietzsche’s philosophy.

3. The Oxford Handbook of Nietzsche, by Ken Gemes and John Richardson

The Oxford Handbook of Nietzsche

BY KEN GEMES & JOHN RICHARDSON

For an insight into just how lively, productive, and diverse the contemporary Nietzsche scholarship scene is, look no further than the 2013 Oxford Handbook of Nietzsche , edited by Ken Gemes and John Richardson.

This brilliant collection brings together 32 essays from leading Nietzsche scholars, covering virtually every aspect of Nietzsche’s thought — from his epistemology and metaphysics, to his value theory and metaethics.

The Oxford Handbook of Nietzsche is the most academic treatment of Nietzsche on this list, but rewards the reader with deep excavations and interpretations of his thinking.

Each essay sheds new light on the great philosopher, making this an essential book for Nietzsche die-hards.

4. Introduction to Nietzsche and His 5 Greatest Ideas, by Philosophy Break

Your Myth-Busting Guide to Nietzsche & His 5 Greatest Ideas

BY PHILOSOPHY BREAK

★★★★★ (50+ reviews)

If you’re looking for a modern, accessible, engaging introduction to Nietzsche’s philosophy with none of the nuance sacrificed, then the 2024 Introduction to Nietzsche and His 5 Greatest Ideas is designed to help you learn everything you need to know about the brilliant philosopher in 42 self-paced, myth-busting lessons.

This concise online guide is instantly accessible from any device, distills Nietzsche’s best and most misunderstood ideas (from God is dead to the Übermensch), and allows you to discuss Nietzsche and philosophy with other members (join 350+ active members inside).

Of course, we’re a little biased, as we produced this one — but if you’re seeking to understand the fundamentals of Nietzsche’s best ideas, have clarity on exactly what he was trying to say across his many works, and discover why he is so influential, then Introduction to Nietzsche and His 5 Greatest Ideas gets rave reviews (one reader describes it as “the best introduction to Nietzsche I’ve come across”), and might be just what you’re looking for!

5. Twilight of the Idols, by Friedrich Nietzsche

Twilight of the Idols

BY FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE

Turning from secondary literature to Nietzsche’s primary works, the question, of course, is where to start .

Well, as we discussed above, though one of his later works, Nietzsche’s 1889 Twilight of the Idols offers one of the best gateways into Nietzsche’s philosophy as a whole.

By no means ‘easy’ (secondary literature, including the previous entries on this list, is highly recommended for first-time Nietzsche readers), Twilight of the Idols nevertheless provides a better starting point than many of Nietzsche’s other works, for he was attempting to write a concise summary of some of the main ideas of his mature philosophy.

Not only that, but Twilight of the Idols contains some fantastic and hilarious passages, it’s a good introduction to Nietzsche’s aphoristic style, and it’s rather short (i.e. less than 100 pages, compared to the 500+ pages of some of Nietzsche’s earlier works).

This particular edition also features an updated, 21st-century translation by Judith Norman, and bundles in some introductory scholarly essays, as well as Nietzsche’s Anti-Christ — another great late work, in which Nietzsche offers his most scathing attack on Christianity — and Ecce Homo , his mania-afflicted autobiography which isn’t a good starting point, but a fascinating read nonetheless.

If you’re looking for your ‘first’ Nietzsche book, this bundled edition of Twilight of the Idols is a better, more accessible option than most, and will give you a feel for the great philosopher’s general ideas and approach.

6. The Gay Science, by Friedrich Nietzsche

The Gay Science

Nietzsche’s early-middle works — Human, All Too Human , Daybreak , and The Gay Science — are hugely significant for the development of his thinking, and the brilliantly rich aphorisms that make them up contain much of the intellectual raw material that form his later ideas.

Though they are rather long ( Human, All Too Human is over 500 pages), all are worth reading at some point; but if you’re seeking an accessible representative from this important era, The Gay Science is a good choice.

The Gay Science is where Nietzsche first mentions his ideas of the death of God , the eternal recurrence , and the higher man — and seeing them in this early form sets one up nicely to better understand Nietzsche’s later works, like Beyond Good & Evil , On the Genealogy of Morals , and Thus Spoke Zarathustra .

7. Beyond Good & Evil, by Friedrich Nietzsche

Beyond Good & Evil

Nietzsche’s 1886 book Beyond Good & Evil is a rich, wide-ranging work in which he explores all the themes for which he is best known: the origins and nature of morality, the will to power, the failures and dangers of objective thinking, the vapidity of modernity, the shortcomings of ‘reason’, the short-sightedness and wrongheadedness of previous philosophers (including Socrates, Kant, Schopenhauer, and many others), as well as how we can overcome mediocrity and suffering and become who we truly are.

Along with his next book, On the Genealogy of Morals , contemporary scholars increasingly recognize Beyond Good & Evil as perhaps Nietzsche’s most important and enduring contribution to philosophy.

Though challenging in places, Beyond Good & Evil is nevertheless incredibly rewarding once you’ve got a few of the Nietzsche fundamentals under your belt — and you can dip around various aphorisms and sections to ease your reading experience.

8. On the Genealogy of Morals, by Friedrich Nietzsche

On the Genealogy of Morals

Foregoing his usual aphoristic style, in his 1887 On the Genealogy of Morals Nietzsche adopts a tripartite essay form, perhaps making for a more conventional and connected reading experience than that of some of his other works.

That said, it remains a dense, difficult, often bamboozling challenge: On the Genealogy of Morals is Nietzsche’s most sustained critique of conventional morality and religion, where he introduces and discusses a diverse collection of novel ideas, including the slave revolt in morality, ‘master’ morality, and the ascetic ideal.

Among the most studied of Nietzsche’s works today, On the Genealogy of Morals stands alongside Beyond Good & Evil , of which it was planned as an accompaniment, as his philosophical masterpiece.

Indeed, if Beyond Good & Evil is the culmination of Nietzsche’s philosophy in his trademark aphoristic style, then On the Genealogy of Morals is the culmination of his philosophy in essay form.

If you’re interested in Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morals belongs on your bookshelf (though some secondary literature would be very handy in helping you fully digest and appreciate it).

9. Thus Spoke Zarathustra, by Friedrich Nietzsche

Thus Spoke Zarathustra

If Beyond Good & Evil and On the Genealogy of Morals are the culmination of Nietzsche’s philosophy as prose, then Thus Spoke Zarathustra is the culmination of Nietzsche�’s philosophy as poetry.

Written between 1883 and 1885, Thus Spoke Zarathustra is a densely lyrical, epic prose-poem that Nietzsche regarded as his most important philosophical contribution (while some scholars agree with this judgment, many see it more as a literary achievement, with his philosophy better expressed elsewhere).

Aping the New Testament in style, it follows the journey of a prophet named Zarathustra who comes down from the mountains to share his “philosophy of the future” (the parallels with Nietzsche’s own life are not, one might suspect, accidental).

Thus Spoke Zarathustra is a challenging read and widely open to interpretation, with the key theme being that we must overcome all past value systems and cultivate self-affirmation — a theme embodied by Nietzsche’s character of the Übermensch , as well as his idea of the eternal recurrence .

While definitely not the best place to start, Thus Spoke Zarathustra is one of Nietzsche’s most famous works for good reason: its audacity, uniqueness, and style make it Nietzsche’s supreme literary achievement.

Further reading

Are there any other books you think should be on this list? Let us know via email or drop us a message on Twitter or Instagram .

In the meantime, why not explore more of our reading lists on the best philosophy books :

View All Reading Lists

Essential Philosophy Books by Subject

Get one mind-opening philosophical idea distilled to your inbox every Sunday (free):

About the author.

Jack Maden Founder Philosophy Break

Having received great value from studying philosophy for 15+ years (picking up a master’s degree along the way), I founded Philosophy Break in 2018 as an online social enterprise dedicated to making the subject’s wisdom accessible to all. Learn more about me and the project here.

If you enjoy learning about humanity’s greatest thinkers, you might like my free Sunday email. I break down one mind-opening idea from philosophy, and invite you to share your view.

Subscribe for free here , and join 12,000+ philosophers enjoying a nugget of profundity each week (free forever, no spam, unsubscribe any time).

Get one mind-opening philosophical idea distilled to your inbox every Sunday (free)

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 12,000+ subscribers enjoying a nugget of profundity from the great philosophers every Sunday:

★★★★★ (50+ reviews for Philosophy Break). Unsubscribe any time.

Each philosophy break takes only a few minutes to read, and is crafted to expand your mind and spark your curiosity.

The Buddha’s Four Noble Truths: the Cure for Suffering

7 -MIN BREAK

Compatibilism: Philosophy’s Favorite Answer to the Free Will Debate

10 -MIN BREAK

The Last Time Meditation: a Stoic Tool for Living in the Present

5 -MIN BREAK

Nietzsche On Why Suffering is Necessary for Greatness

3 -MIN BREAK

View All Breaks

PHILOSOPHY 101

- What is Philosophy?

- Why is Philosophy Important?

- Philosophy’s Best Books

- About Philosophy Break

- Support the Project

- Instagram / Threads / Facebook

- TikTok / Twitter

Philosophy Break is an online social enterprise dedicated to making the wisdom of philosophy instantly accessible (and useful!) for people striving to live happy, meaningful, and fulfilling lives. Learn more about us here . To offset a fraction of what it costs to maintain Philosophy Break, we participate in the Amazon Associates Program. This means if you purchase something on Amazon from a link on here, we may earn a small percentage of the sale, at no extra cost to you. This helps support Philosophy Break, and is very much appreciated.

Access our generic Amazon Affiliate link here

Privacy Policy | Cookie Policy

© Philosophy Break Ltd, 2024

- NONFICTION BOOKS

- BEST NONFICTION 2023

- BEST NONFICTION 2024

- Historical Biographies

- The Best Memoirs and Autobiographies

- Philosophical Biographies

- World War 2

- World History

- American History

- British History

- Chinese History

- Russian History

- Ancient History (up to 500)

- Medieval History (500-1400)

- Military History

- Art History

- Travel Books

- Ancient Philosophy

- Contemporary Philosophy

- Ethics & Moral Philosophy

- Great Philosophers

- Social & Political Philosophy

- Classical Studies

- New Science Books

- Maths & Statistics

- Popular Science

- Physics Books

- Climate Change Books

- How to Write

- English Grammar & Usage

- Books for Learning Languages

- Linguistics

- Political Ideologies

- Foreign Policy & International Relations

- American Politics

- British Politics

- Religious History Books

- Mental Health

- Neuroscience

- Child Psychology

- Film & Cinema

- Opera & Classical Music

- Behavioural Economics

- Development Economics

- Economic History

- Financial Crisis

- World Economies

- Investing Books

- Artificial Intelligence/AI Books

- Data Science Books

- Sex & Sexuality

- Death & Dying

- Food & Cooking

- Sports, Games & Hobbies

- FICTION BOOKS

- BEST NOVELS 2024

- BEST FICTION 2023

- New Literary Fiction

- World Literature

- Literary Criticism

- Literary Figures

- Classic English Literature

- American Literature

- Comics & Graphic Novels

- Fairy Tales & Mythology

- Historical Fiction

- Crime Novels

- Science Fiction

- Short Stories

- South Africa

- United States

- Arctic & Antarctica

- Afghanistan

- Myanmar (Formerly Burma)

- Netherlands

- Kids Recommend Books for Kids

- High School Teachers Recommendations

- Prizewinning Kids' Books

- Popular Series Books for Kids

- BEST BOOKS FOR KIDS (ALL AGES)

- Ages Baby-2

- Books for Teens and Young Adults

- THE BEST SCIENCE BOOKS FOR KIDS

- BEST KIDS' BOOKS OF 2023

- BEST BOOKS FOR TEENS OF 2023

- Best Audiobooks for Kids

- Environment

- Best Books for Teens of 2023

- Best Kids' Books of 2023

- Political Novels

- New History Books

- New Historical Fiction

- New Biography

- New Memoirs

- New World Literature

- New Economics Books

- New Climate Books

- New Math Books

- New Philosophy Books

- New Psychology Books

- New Physics Books

- THE BEST AUDIOBOOKS

- Actors Read Great Books

- Books Narrated by Their Authors

- Best Audiobook Thrillers

- Best History Audiobooks

- Nobel Literature Prize

- Booker Prize (fiction)

- Baillie Gifford Prize (nonfiction)

- Financial Times (nonfiction)

- Wolfson Prize (history)

- Royal Society (science)

- Pushkin House Prize (Russia)

- Walter Scott Prize (historical fiction)

- Arthur C Clarke Prize (sci fi)

- The Hugos (sci fi & fantasy)

- Audie Awards (audiobooks)

Make Your Own List

Philosophy Books » Great Philosophers

The best nietzsche books, recommended by brian leiter.

Moral Psychology with Nietzsche by Brian Leiter

Relativist, atheist, existentialist, Nazi. All have been said of German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, some with more reason than others. We asked Nietzsche expert Brian Leiter to explain the appeal of the controversial philosopher and recommend books to get started with to understand him and his work.

Nietzsche: A Philosophical Biography by Rüdiger Safranski & translator Shelley Frisch

Nietzsche on Truth and Philosophy by Maudemarie Clark

Nietzsche’s System by John Richardson

Beyond good and evil by friedrich nietzsche & walter kaufmann (translator).

On the Genealogy of Morality by Friedrich Nietzsche

1 Nietzsche: A Philosophical Biography by Rüdiger Safranski & translator Shelley Frisch

2 nietzsche on truth and philosophy by maudemarie clark, 3 nietzsche’s system by john richardson, 4 beyond good and evil by friedrich nietzsche & walter kaufmann (translator), 5 on the genealogy of morality by friedrich nietzsche.

B efore we get to the books, how did you first become interested in Nietzsche as one of your philosophical specialities?

What did you particularly like about him?

I had actually become interested in philosophy from reading Sartre as a high school student in French classes. The essay Rorty assigned starts on a very existentialist note – and of course the writing was very evocative. At this point I was reading it in English but Walter Kaufman’s strength as a translator is that he captures the flavour of Nietzsche in English. He’s not the most literal translator but he is the most evocative. So it was a combination of the proto-existentialist themes and the style of the writing that I found very gripping. And that sense never left me – I still always enjoying reading and re-reading Nietzsche.

We’re going to talk about five books you’d recommend for someone who’s interested but not an expert in Nietzsche. You’ve chosen a mixture of primary and secondary material. Would you say it’s best for readers to begin with the modern academic texts or should they go straight to Nietzsche first?

I think it’s a question of whether they’ve had any exposure to philosophy. If somebody has not had much exposure to philosophy, then it might be best to start with the Safranski biography before going to the primary texts. The primary texts are certainly more fun and if you were to start with one of them, then Beyond Good and Evil would be a great choice, because it covers all the distinctive and important Nietzschean themes and as it’s broken into bite-size pieces you don’t get overwhelmed. But if you wanted someone to patiently introduce you then Safranski is good on that score.

It seems like Nietzsche is one of the few philosophers whom lots of people who have never studied philosophy still enjoy reading. Why do you think he’s so appealing in this way?

I think the most important reason to start with is that he’s a great writer, and that is not the norm in philosophy. He’s a great stylist, he’s funny, he’s interesting, he’s a bit wicked, he’s rude. And he touches on almost every aspect of human life and he has something to say about it that’s usually somewhat provocative and intriguing. I think that’s the crucial reason why Nietzsche books are so popular. Indeed, he’s probably more popular outside academic philosophy because he’s so hostile to the main traditions in Western philosophy.

Do you think people who haven’t studied philosophy can get quite a lot out of him? You might not really enjoy Spinoza’s Ethics , for instance, if you just picked it up randomly in a bookshop or in the library. Would you say that’s the case with Nieztsche’s books?

I think people without that philosophical background do miss quite a lot – because a lot of what is going on in Nietzsche is reaction to and sometimes implicit dialogue with earlier philosophers. If you don’t know any Kant or Plato or the pre-Socratics, you’re not going to understand a lot of what’s motivating Nietzsche, what he’s reacting against. You get a much richer appreciation of Nietzsche if you are reading him against the background of certain parts of the history of philosophy.

Nietzsche himself was not trained in philosophy, he was trained in classics. But that included a great deal of study of ancient Greek philosophy. And then he taught himself a lot of other philosophy. Kant and Schopenhauer were particularly important to him.

Are there any non-philosophers who have influenced the way you think about Nietzsche?

Let’s start with the Safranski book, Nietzsche: A Philosophical Biography . There are absolutely loads of biographies of Nietzsche. Why did you go with this one in particular?

I think the virtue of this book is that it has a detailed and readable narrative of the life, but it combines it with an introduction to the philosophical works, which is written at a very appropriate level for the beginner. That’s the main reason I picked the Safranski.

The standard German biography of Nietzsche, by this guy Curt Paul Janz, is a three-volume tome that is exhaustive but it’s also exhausting. It’s a very good resource for scholars but not a delightful book for beginners.

There’s a famous quote in Beyond Good and Evil where Nietzsche says that despite philosophers’ claims about arguing rationally and aiming to find objective truth, all philosophy has really been a form of unconscious and involuntary autobiography. How do you think Nietzsche’s own life informs his philosophy, if at all?

The influences of Nietzsche’s own life on the philosophy are very dramatic. Some of them have to do with the intellectual biography, of course – what he studied, what he read et cetera. But I think probably the crucial fact about Nietzsche’s life is that when he writes about suffering he’s not a tourist. He’s writing about something he knows very intimately. He understands from his own experience the effect of suffering on the mind, on creativity and on one’s attitude to life generally. And if there’s a central question in Nietzsche it’s the one he takes over from Schopenhauer – namely, how is it possible to justify life in the face of inevitable suffering? Schopenhauer comes up with a negative answer. He endorses something like a stereotype of the Buddhist view: The best thing would not to be born, but if you’re born the next best thing would be to die quickly. Nietzsche wants to repudiate that answer – partly through bringing about a re-evaluation of suffering and its significance.

Could you give a sense of the suffering Nietzsche experienced and why his life was so difficult?

He was the proverbial frail and sickly child. But the real trouble started in his early 30s, the 1870s, when he started to develop gradually more and more physical maladies – things that looked like migraines, with nausea, dizziness, and he would be bedridden. It got so severe that he had to retire from his teaching position at the age of 35. So he spent the remainder of his sane life, until his mental collapse in 1889, basically as an invalid travelling between different inns and hotels in and around Italy, Switzerland and southern France, trying to find a good climate, often writing, often walking when his health permitted, but often bedridden with excruciating headaches, vomiting, insomnia. He was trying every self-medication device of the late 19th century. He had a pretty miserable physical existence. His eyesight also started to fail him during this time. Through all this he usually managed to continue to write and read, despite these ailments. So he really knew what suffering was.

In retrospect, there’s reasonably good evidence that he had probably at some point contracted syphilis and that the developing infection might have been responsible for these maladies. Though his father had also died at an early age, so there may have been some familial genetic component as well.

Safranski himself is German, whereas the other two secondary texts you recommend are by American scholars. Is there a difference between the view of Nietzsche in German scholarship and in Anglo-American scholarship at present?

What would be the next book to read if you’ve just finished the Safranski?

I think the one to go for would be the Clark – Nietzsche on Truth and Philosophy .

Given the title, does this book focus on Nietzsche’s epistemology or is it more of a general overview?

The first half of the book is primarily about truth and knowledge, matters of metaphysics and epistemology. The book appeared in 1990 and it was a very significant work. It was very unusual because, first of all, it treated Nietzsche as a philosopher. I know that sounds a funny thing to say, but an awful lot of books on Nietzsche are full of quotations and paraphrase – they don’t really engage dialectically and argumentatively with what Nietzsche has to say.

What Clark did, through systematic examination of Nietzsche’s views about truth and knowledge from the early essays through to his final works, was to try to show that Nietzsche’s view of truth and knowledge evolved over time, that it changed in significant ways.

Often Nietzsche is, perhaps wrongly, associated with a postmodern rejection of objective truth. I presume that’s not what this book argues…

That is Clark’s target in this book – the idea that Nietzsche is the guy who thinks there’s no such thing as truth and that there’s no such thing as knowledge, that every view is as good as every other view. She suggests that there may have been an aspect of the postmodernist view of truth in Nietzsche’s early work, but that he gradually came to abandon that view once he came to abandon the intelligibility of the old Kantian distinction between the way things appear to us versus the way things really are in themselves . There are a lot of difficult philosophical issues here, but that’s the crux of the story she’s trying to tell in the first part of the book.

As you mentioned the contrast between Clark and Richardson, let’s move on to the next book, Nietzsche’s System . First off, am I right in thinking that that title is rather controversial, given that Nietzsche is often seen as an anti-systematic philosopher?

The title is meant to be provocative, but Richardson’s central claim is that there is a kind of thematic coherence to all of Nietzsche’s work, and this coherence derives in part from the doctrine of the will to power.

Let’s just explain exactly what the will to power is for those not familiar with it.

Well, this question of definition is part of the Clark-Richardson debate. The Clark side is that what Nietzsche means by the will to power is that people are often motivated to act because the action will give them a feeling of power. But Richardson’s view is closer to Heidegger’s, although he makes a more compelling and sophisticated case for it.

Richardson’s view of Nietzsche’s doctrine of the will to power is this: Every person is made up of a bundle of “drives” – sex drive, hunger drive, drive for knowledge, and so on. Every drive, according to Richardson’s reading of Nietzsche, is characterised by the will to power. Every drive has a tendency to want to enlist every other drive in its service. So if the sex drive is dominant in a person – think Hugh Hefner – then the sex drive tries to get every other drive enlisted in helping satisfy it. So knowledge or food would only be of interest to the extent that they facilitate gratification of the sex drive, and so on.

Out of this basic picture of human psychology and the metaphysics of drives and their essential nature as will to power, Richardson thinks you can take this theme and see how it figures in everything else Nietzsche writes, whether it’s about truth, knowledge, morality and so on. In that sense he tells a very systematic story about Nietzsche’s thought.

If you side more with Clark in the debate, what made you decide to recommend Richardson’s Nietzsche book?

First of all, I think it’s a very well done and compelling interpretation. What’s particularly interesting is that Richardson , who is also a well-known Heidegger scholar, takes up a theme that was important to Heidegger’s reading of Nietzsche – the view that Nietzsche is the final point in the history of Western metaphysics. First there was Plato and at the very end was Nietzsche, and Nietzsche’s metaphysical doctrine is that everything is will to power. Richardson takes up that idea but gives it a very refined and nuanced elaboration that makes it much more plausible than it ever was in Heidegger.

Let’s move on to the primary texts. You mentioned that Beyond Good and Evil is a good one to dip into for people who are new to Nietzsche books, because it provides a good overview to his thoughts…

Yes, I think that’s right. It touches on almost all Nietzsche’s central concerns – on truth, on the nature of philosophy, on morality, on what’s wrong with morality, will to power.

The first thing you notice when you open the book is the layout and the way it’s written, which is striking, especially if you come to it having read modern philosophy essays and that kind of thing. Why does Nietzsche write in such an unusual, more aphoristic style?

The explanation really comes in the first chapter of the book where Nietzsche tells us that the great philosophers are basically fakers when they tell you that they arrived at their views because there were good rational arguments in support of them. That’s nonsense, says Nietzsche. Great philosophers , he thinks, are driven by a particular moral or ethical vision. Their philosophy is really a post-hoc rationalisation for the values they want to promote. And then he says that the values they want to promote are to be explained psychologically, in terms of the type of person that that philosopher is.

The relevance of this is that if this were your view of the rational argumentation of philosophers, it would be quite bizarre to write a traditional book of philosophy giving a set of arguments in support of your view. Because in Nietzsche’s view consciousness and reasoning are fairly superficial aspects of human beings. What really gets us to change our views about things are the non-rational, emotional, affective aspects of our psyche. One of the reasons he writes aphoristically and so provocatively – and this, of course, is why he’s the teenager’s favourite philosopher – is connected to his view of the human psyche. He has to arouse the passions and feelings and emotions of his readers if he’s actually going to transform their views. There’d be no point in giving them a systematic set of arguments like in Spinoza’s Ethics – in fact he ridicules the ‘geometric form’ of Spinoza’s Ethics in the first chapter of Beyond Good and Evil .

Do you have a particular favourite passage from Beyond Good and Evil that exemplifies Nietzsche’s direct and provocative approach?

For funny wickedness I do like Section 11, on Kant’s philosophy . It’s hysterically funny – if you’re familiar with Kant’s philosophy, that is. It’s not a late-night TV concept of hysterically funny!

You mentioned that Nietzsche is fascinated by psychology . Do you think if he were around today he would be hanging around the psychology department, rather than the philosophy department?

Maybe not the psychology department in its current form! But he would be interested in psychological research. There are a number of themes in contemporary empirical psychology that are essentially Nietzschean themes. There is a large literature suggesting that our experience of free will is largely illusory, that we often think we’re doing things freely when in fact we’re not, that our actions have sources that lie in the pre-conscious and unconscious aspects of ourselves and then we wrongly think we’re acting freely. These are themes familiar to anyone who’s read Nietzsche books and it’s striking that recent empirical work is largely coming down on Nietzsche’s side on these questions.

Would it be right to say Nietzsche was a big influence on Freud as well?

Freud claims to have stopped reading Nietzsche at a certain point – perhaps he thought Nietzsche anticipated his own views to an uncomfortable extent. But they share a very similar picture of the human mind, in which the unconscious aspect of the mind, and in particular the affective, emotional, non-rational part of the mind, plays a decisive role in explaining many of our beliefs, actions and values. Freud came up with a more distinctive and precise account of the structure of the unconscious, but the general picture is very similar.

Let’s talk about On the Genealogy of Morality, then. Is it fair to say that this is often seen, nowadays, as Nietzsche’s masterpiece?

I don’t know I would single it out as the masterpiece, but it’s a fascinating book which follows on many of the themes of Beyond Good and Evil . It’s unusual because it’s less aphoristic, but rather three essays. The essays have more structure and extended argumentation than is typical in most of Nietzsche’s works.

The book deals with the two absolutely central questions for Nietzsche, namely what’s wrong with our morality and the problem of suffering. It tells an extremely provocative story about each of these and in the third essay it even connects up with Nietzsche’s interest in questions about the nature of truth and why we value truth. In that sense it really is a mature work, bringing together reflections on topics that span the prior decade.

Why did you decide to recommend different translators for these two Nietzsche books?

Clark and Swensen, I think, have the best English translation of the Genealogy but it’s the only work they translated. If they had ever translated Beyond Good and Evil I might have recommended that. They are more literal than Kaufman, who does take liberties at times with the German. That often has a virtue – you get more of a sense of Nietzsche in Kaufman’s English than anyone else’s English, but sometimes for a philosophically-minded reader it can elide certain important distinctions. Clark is a philosopher, Swensen is a German-language scholar, and so they bring two good skill sets to the translation. Swensen has a good feel for the German and Clark is very sensitive to what is philosophically important in the German and not losing that in translation.

The other thing that is very nice about their edition is that it has very detailed notes. The Genealogy is sort of notorious because it has no footnotes. It makes all kinds of historical claims, etymological claims et cetera, but there are no footnotes because that’s not how Nietzsche does things. But in point of fact he had scholarly sources in mind on almost every one of these issues, and Clark and Swensen compiled them. So they supply the underlying scholarly apparatus for the kind of claims Nietzsche is making, which makes this a very useful text.

The book obviously focuses on morality. Do you think there’s been a shift in the way scholars have seen Nietzsche’s view of morality over the past 60 or 70 years?

I do think there’s been a significant change and I think there’s a simple explanation for it. Nietzsche’s association with the Nazis didn’t exactly help his reputation. For people like Walter Kaufman, who wrote an influential book about Nietzsche after the war, his Nietzsche is a pleasant, secular liberal. He’s a nice guy who believes in self-development – he’s not a scary Nazi! With Heidegger, we see Nietzsche as a metaphysician with a grand picture of the essence of reality as will to power, and the moral/political side of Nietzsche’s thought gets pushed aside. For the French deconstructionists, Nietzsche’s a guy who tells us that no text has a stable meaning and there’s no truth and so on. All these readings pull us away from Nietzsche’s core evaluative concerns, and I think over the last 20 years those concerns have come back to centre stage.

Support Five Books

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you're enjoying this interview, please support us by donating a small amount .

I think it’s always worth saying that Nietzsche was no Nazi. To start with, he hated Germans. This created a lot of problems for the Nazis. They had to edit the texts quite selectively because he hated German nationalists, he hated anti-semites, he hated militarists. He wouldn’t have fitted in too easily at Nuremberg! On the other hand, it is absolutely true that Nietzsche has quite shocking views about traditional Christian morality. Kaufman whitewashed this 50 years ago, but I think it’s less common to do so now. Nietzsche is deeply illiberal. He does not believe in the equal worth of every person. Nietzsche thinks there are higher human beings. His favourite three examples are Goethe , Beethoven and Nietzsche himself. And that higher human beings, through their creative genius, can actually make life worth living – that Beethoven’s 9th Symphony is enough to justify all the suffering the world includes. Again this is a crude summary but there is this aspect of Nietzsche. At the heart of his critique of morality is that he thinks creative geniuses like Beethoven, had they really taken morality seriously, wouldn’t have been creative geniuses. Because to really take morality seriously is to take your altruistic obligations seriously – to help others, to weigh and consider the interests of others et cetera. You can read any biography of Beethoven and see that that wasn’t how he lived! He was single-mindedly focused on his creative work and that’s what Nietzsche means by severe self-love.

Given that Nietzsche has a profoundly illiberal view of morality, what does he have to say to us now – if, that is, you’re keen to come at morality from, loosely speaking, a liberal and democratic point of view?

Even if you’re not as illiberal as Nietzsche, you might be worried if Nietzsche’s right that certain kinds of traditional moral values are incompatible with the existence of people like Beethoven. That’s the strong psychological claim he makes – that you can’t really be a creative genius like Beethoven and take morality seriously. I think even good old democratic egalitarian liberals could worry a bit about that, if it were true. It’s a very striking and pessimistic challenge, because the liberal post-Enlightenment vision is that we can have our liberal democratic egalitarian ethos and everyone will be able to flourish. Nietzsche thinks there’s a profound tension between the values that traditional morality holds up and the conditions necessary for creative genius.

So that challenge is interesting in its own right, even if you wouldn’t want to side with Nietzsche, who’s ready to sacrifice the herd of humanity for the sake of a Goethe or a Beethoven. And then there are all these aspects of Nietzsche that don’t really depend for their importance on his ultimate evaluative judgement. There’s Nietzsche’s picture of the human mind, there’s his attack on traditional philosophy, his attack on free will and moral responsibility. All of these themes are interesting and challenging, and resonate with themes in contemporary philosophy – even if you don’t have the same illiberal affect that Nietzsche has. And of course most readers don’t. That’s why there’s been a lot of whitewashing of Nietzsche in the secondary literature. It’s a bit shocking. It certainly took me a while to come to terms with the fact that this is really what Nietzsche believes, that the illiberal attitudes and the elitism was really central to the way he looked at things. The suffering of mankind at large was not a significant ethical concern in his view, it was largely a matter of indifference – in fact it was to be welcomed because there’s nothing better than a good dose of suffering to get the creative juices flowing.

___________________________

Since this interview was first published in 2011, you’ve written a new book on Nietzsche. Could you tell me a bit about that?

My book Moral Psychology with Nietzsche (Oxford, 2019) explores issues that were either ignored or touched on only briefly in my earlier book Nietzsche on Morality (Routledge, 2002; 2nd ed., 2015). These are issues that professional philosophers usually group under the label “moral psychology,” questions about the nature of morality and moral judgment, the structure of human agency, and the like. For example, since Nietzsche denies that value judgments are objective (I set out and defend his arguments for this view), what happens psychologically when we make such judgments? Nietzsche, I argue, should be seen as part of a tradition of moral anti-realists who are also sentimentalists , like Hume and, in the German tradition, Herder—that is, philosophers who think the best explanation of our moral judgments is in terms of our emotional responses to states of affairs in the world, responses that are, themselves, explicable in terms of psychological facts about the judger.

I also explore Nietzsche’s views about agency and his skepticism about free will. The book has exegetical aims, certainly, but it is not an exercise in the “history of ideas.” I believe Nietzsche is often correct, for example, in his anti-realism about value, his sentimentalism, his skepticism about the causal efficacy of consciousness, and his skepticism about the post-hoc rationalizations of moral philosophers for their moral beliefs. Much of the book is devoted to arguing philosophically, and on the basis of empirical psychological evidence, for Nietzsche’s views.

Which books by Nietzsche does your book focus on?

I range fairly widely over Nietzsche’s mature works, but besides the two crucial books recommended in the earlier interview— Beyond Good and Evil and On the Genealogy of Morality —I think two other works are quite important for understanding his moral psychology: Daybreak , his first mature work of 1881, and Twilight of the Idols , one of his last works in 1888.

Are there any other books on Nietzsche that have come out since this interview that you’d recommend?

A very good collection of original essays on Nietzsche can be found in the book The Oxford Handbook of Nietzsche (2013), edited by Ken Gemes and John Richardson: the volume gives readers a nice sense of why this is now a “golden age” for Nietzsche scholarship in the Anglophone world. I especially commend the chapters by Jessica Berry on Nietzsche and the ancient Greeks (readers interested in that topic might also look at her Nietzsche and the Ancient Skeptical Tradition [Oxford, 2011]); Nadeem Hussain on Nietzsche’s metaethical views; and Paul Katsafanas on his philosophical psychology.

A very important book on the latter topic ( Nietzsche’s Philosophical Psychology ) , by an Italian philosopher, Mattia Riccardi, came out from Oxford University Press in 2021. He combines philosophical skill and historical knowledge in elucidating Nietzsche’s views about the drives, affects, and consciousness, among other topics. I have no doubt his book will be a major event in Nietzsche studies.

September 8, 2020

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]

Brian Leiter

Brian Leiter is Karl N. Llewellyn Professor of Jurisprudence and Director of the Center for Law, Philosophy, and Human Values at the University of Chicago. He is the author of Nietzsche on Morality and co-editor of several books on Nietzsche’s work. He has also published widely on topics in moral, political and legal philosophy, and runs the influential philosophy blog Leiter Reports

We ask experts to recommend the five best books in their subject and explain their selection in an interview.

This site has an archive of more than one thousand seven hundred interviews, or eight thousand book recommendations. We publish at least two new interviews per week.

Five Books participates in the Amazon Associate program and earns money from qualifying purchases.

© Five Books 2024

- Corrections

Friedrich Nietzsche: The 13+1 Best Books Of His Philosophical Career

Friedrich Nietzsche was a provocative 19th-century philosopher who critiqued traditional values and explored the complexities of human nature and the pursuit of power.

Friedrich Nietzsche was one of the towering figures in philosophy, whose lasting mark on the late 19th and early 20th-century intellectual landscape left a distinctive imprint. Known for his unorthodox views and provocative ideas, Nietzsche’s works continue to capture readers, scholars, and thinkers alike.

Nietzsche’s writings elaborate the following philosophical ideas: nihilism, master-slave morality, perspectivism, eternal recurrence, and Übermensch (Superman). He criticized traditional values and societal institutions while advocating for individualism and self-overcoming.

So let us explore Nietzsche’s philosophical journey by looking into all the important books that explain his intellectual development.

Human All Too Human, 1880

One of Nietzsche’s first and most important books, Human, All Too Human , is a collection of aphorisms and reflections published in three parts between 1878 and 1880. It represents an important stage in Nietzsche’s philosophical career as he distanced himself from the idealism of his earlier works towards a more skeptical, critical view.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription.

In the first section of the book, “Of the First and Last Things,” Nietzsche covers a wide range of topics: from science, to philosophy, culture, and human existence. He challenges traditional religious beliefs and makes an assertion that man has made religion as a way to cope with their fears and uncertainties. Besides, Nietzsche argues for the importance of reason and rationality to understand the world, abandoning dogmas of religion in favor of empirical inquiry.

In “History of the Moral Feelings,” the second part, Nietzsche turns his attention to morality and ethics . He engages in a critical examination with respect to the origins of moral values and seeks to unveil their underlying psychological motivations. He argues that moral values are not universal truths but rather societal constructs shaped by power dynamics as well as individual perspectives. This critique undermines traditional notions of good and evil and posits them as largely subjective notions conditioned culturally.

In the third section, “The Religious Life,” he dissects religious systems, particularly Christianity, saying they perpetuate a life-denying mentality rather than opening people up to fill the challenges of life with fullness. To him, religion is an impediment to personal growth and freedom because it demands conformity over individual self-realization.

Throughout Human, All Too Human , Nietzsche takes on a kind of scientific approach to philosophy. This work establishes the context for many themes that would continue to pervade Nietzsche’s later writings, such as nihilism, perspectivism (the theory that knowledge is always tied to one’s perspective), and the importance of embracing life’s contradictions.

The Gay Science, 1882

The Gay Science , the 1882 masterpiece by Nietzsche, is an invigorating and heterogeneous conglomerate of aphorisms, poems, and reflections that explore life’s complexities and contradictions.

Amongst the major themes explored in The Gay Science is that life should be embraced enthusiastically and joyously, even amidst its challenges and uncertainties. Nietzsche encourages individuals to engage with life courageously, embracing both its highs as well as lows. He contemplates the notion of “amor fati” which translates to “love of fate.” This philosophy urges us not only to accept but also to love our destiny by finding meaning even in suffering.

Another distinctive feature of The Gay Science is the explanation of truth and knowledge. Nietzsche rejects traditional common views that consider truth as an objective reality available only via rational thinking. Instead, he asserts a more varied view called perspectivism—the notion of conceiving truth as always subject to our viewpoints. There are no absolute truths, according to Nietzsche—they emerge from individual perceptions.

The book also celebrates the notorious proclamation: “ God is dead .” With this daring statement, Nietzsche disparaged religious dogmas and stated that society had grown enough out of its dependence on obsolete religious frameworks. But instead of nihilism or despair without traditional beliefs, Nietzsche urges for humanity to become creators of their own values. He encourages people to make their own paths and find meaning without being dependent on external sources such as religion or societal norms.

The unconventional structure and snappily energetic style make The Gay Science a really enthralling read. Nietzsche’s gift for intermingling profound insights with wit and provocation ensures readers are challenged at every turn.

Thus Spoke Zarathustra, 1883

Thus Spoke Zarathustra was published in 1883 and is the most famous of Friedrich Nietzsche’s works. Described as a series of philosophical allegories, it tells the story of Zarathustra, a mythical prophet who descended from his mountain retreat to communicate his wisdom to mankind.

In the very heart of Thus Spoke Zarathustra is found this idea of Übermensch or “Superman” or “Overman.” Nietzsche depicts this visionary as the highest point in human potential—the breaker of traditional morals and practices that created his own value systems. The distinctions between right and wrong, good and bad, have no meaning for the Übermensch. They make their own value system by seeking individual excellence.

Zarathustra’s teachings arouse conventional beliefs about good and evil. According to Nietzsche, morality is not fixed but rather the product of human creation. He encourages individuals to put aside concepts of guilt and punishment inherited from religion. For him, liberation lies in acknowledging and owning one’s own desires while bearing full responsibility for their consequences.

Besides that, the book also establishes the idea of eternal recurrence, where Zarathustra reveals to his disciples that life has to be accepted fully and repeatedly without any regrets. It asserts that all events that we experience will recur infinitely throughout eternity. Nietzsche sees this concept as a test: if one were to accept every event in their lives with complete acceptance and joy, then they have attained true liberation.

In addition, Thus Spoke Zarathustra demonstrates the nature of seeking the meaning of life . According to Nietzsche, no meaning can be extracted from the outside; rather, realization comes from grasping the contradiction inherent within life itself.

Nietzsche’s provocative prose and visionary allegories paint an engaging exploration of the human condition. The reader is challenged to transcend societal constraints and forge their own paths toward self-realization and personal growth.

Beyond Good And Evil, 1886

Another one of Nietzsche’s major works, Beyond Good and Evil was written in 1886 and provides his most focused attack on traditional moral and philosophical systems. In it, Nietzsche questions the good/evil dichotomy that dominates Western thought. He states that these concepts are not fixed or universal but rather subjective constructs fashioned out of cultural norms and prevailing power dynamics.

Nietzsche states that morality is a human interpretation as opposed to an absolute truth that is imposed upon us. Morality, according to him, cannot be divorced from individuality, freedom of will, or desire: they are basic forces in one’s actions.

Beyond Good and Evil introduces the element of the “will to power”—an elemental force in human behavior. According to Nietzsche, all living beings have an inner drive for self-affirmation and domination over their environment. This philosophy deconstructs altruism and highlights the importance of personal autonomy and ambition in shaping one’s destiny.

Also, in this book, Nietzsche resorts to the aphoristic style —using short yet intense observations—whereby readers are left to ponder each maxim individually while constructing a thorough picture of his ideas. His polemical statements strike both awe and controversy within readers, propelling them into forming their own beliefs.

Beyond Good and Evil is a philosophical “call to arms:” a summons for people to reconsider unquestioned assumptions of truth, morality, and authority. It invites people to examine uncomfortable truths about themselves and society as a whole.

In other words, Beyond Good and Evil is an intellectual battlefield on which Nietzsche fights complacency—a manifesto urging us out onto an endless quest for knowledge, leading us towards asking difficult questions without shying away from “hard” answers.

On The Genealogy Of Morality, 1887

The Genealogy of Morality was written by Friedrich Nietzsche in 1887. This is a relentless critique of traditional moral values, which constitutes a deep examination of the origins and development of human morality. In this provocative work posed as an inquiry into human culture, Nietzsche sets himself to unravel the complex genealogical roots behind our moral beliefs and throws light on how they shape our understanding of good or evil.

The book is divided into three essays. Each essay explores one aspect of morality. In the first essay, Nietzsche deconstructs the concept of “good.” He traces the idea to power and superiority. He argues that morality initially arose from a master-slave dynamic—those in positions of power created definitions of good that would serve their own interests and subjugate others.

In the second essay, “Guilt, Bad Conscience, and Related Matters,” Nietzsche explains the psychological mechanisms of morality. He says that guilt appears as a product of social pressure, conditioning people to suppress their natural instincts. In an alternative point of view suggested by Nietzsche, he says if one can live with desires without guilt or shame, then one will achieve personal growth and self-realization.

Finally, in the third essay, “What Do Ascetic Ideals Mean?” Nietzsche examines asceticism as a vital element of moral systems. He states that ascetic ideals—self-denial, renunciation, and discipline—have been propagated by cultures for centuries as a means to control people and keep social order. Yet he thinks these ideals, at last, prevent the human potential for creativity and pleasure.

This riveting work asks fundamental questions about human nature: Who decides what is good or evil? How does morality shape our lives and direct our actions? Nietzsche’s inquiry into such deep matters makes readers confront their own moral beliefs, as well as consider the constructive possibilities that emerge in breaking down convention.

Twilight Of The Idols, 1888

In Twilight of the Idols , published in 1888, Nietzsche launches a scathing critique of various aspects of Western culture. This work is characterized by its provocative, audacious style.

One of the central themes in Twilight of the Idols is the notion of “ ressentiment ,” which describes feelings of resentment towards those in power and towards creativity. Nietzsche says that this ressentiment breeds reactionary thoughts or concepts that desire to uproot those who are powerful and creative. According to him, such a mentality leads to societies where mediocrity is valued above excellence.

Another central theme in Twilight of the Idols is the rejection by Nietzsche of conventional notions regarding morality. He advocates for a reevaluation of moral standards, arguing for one’s embrace of an individualistic approach to morality where the action is guided by personal experience and desires rather than notions imposed on society by religion or notions handed down from adults.

Again, here, Nietzsche has employed his concept of “will to power.” He believes that all living creatures are propelled by an inherent desire for power which manifests itself collectively under the heading of striving for success or seeking control over others. According to Nietzsche, this will to power is at the basis of human nature and acts as a driving force behind individual development and achievement.

Twilight of the Idols also discusses both Nietzsche’s critiques of Christianity as well as its direct influence on Western civilization. He is vehemently opposed to what he perceives as Christian nihilism that promotes self-denial and weakness in morals instead of life with its inherent joys and challenges.

The Antichrist, 1895

The Antichrist was published in 1895. It is among Friedrich Nietzsche’s most controversial, as well as polemical, works. Nietzsche started conceiving this work in 1888. This period also saw Nietzsche suffer from a mental breakdown which marked the end of his active philosophic career. The book harks back to his rejection of Christianity and offers scathing critiques not only regarding its morality but also its teachings.

Not wasting any time at all, Nietzsche immediately launches into provocatively titled territory with the very title itself. By framing his work as “The Antichrist,” he identifies himself as an actual adversary to Christ. Still, Nietzsche is more interested in unearthing what he feels are the faults within Christian doctrine .

In substance, The Antichrist analyzes Christian values and argues that they damaged humanity. According to Nietzsche, the morality of Christianity is based on weakness, resentment, and self-denial. He maintains that this morality has weakened individuals and societies because it promotes an attitude of obedience to authority figures and suppresses natural human instincts and desires as well.

In The Antichrist , Nietzsche also traces the origin of historical characters like Socrates and Paul of Tarsus. He portrays Socrates as the corruptor leading philosophy astray by stressing rationality over instinctual wisdom. Concerning the apostle Paul , he accuses him of imposing a distortion in Jesus’s teachings to create a religion that propagates slave morality—a value system centered on meekness and submissiveness.

To call The Antichrist a major work within Nietzsche’s philosophical career would be an understatement. Yet, it was extremely critiqued upon its release and remains controversial today. It constitutes a total condemnation of religious dogma and an incisive look at alternate perspectives on morality and human nature.

Ecce Homo, 1888

Ecce Homo , or “Behold the Man,” is Friedrich Nietzsche’s autobiography and last completed work. It was finally published in 1888 after being kept away for several years. In this amazing book, Nietzsche gives a far-reaching account of his life, beliefs, and achievements—all presented with his characteristic wit and brilliance.

The foundations of Ecce Homo start from Nietzsche’s wish to reflect on what he thought was his life’s work as well as an assessment of his philosophy. It is both a retrospective exploration and an explanation of various stages within his intellectual journey. Nietzsche felt that to understand the worth and importance of his ideas for humanity, he must first understand his own life.

Among the major themes addressed by Ecce Homo is a radical self-confident person who breaks conventional norms and values. It’s clear that Nietzsche considered himself a transformative figure whose philosophy’s purpose is to try and overthrow old beliefs/values and pave the way for new, positive values.

One theme Ecce Homo has in common with Nietzsche’s other works is another “attack” on Christianity. He blames Christianity for many societal ills because of the emphasis on weakness, pride, conformity, and denial of individual desires. Through vivid reflections on his earlier works, such as Thus Spoke Zarathustra and The Genealogy of Morality , he offers alternative visions for human existence founded on strength, creativity, power, and personal development.

Another prominent feature of Ecce Homo is the style that Nietzsche employs in writing. He uses an autobiographical approach rich with poetic language, aphorisms, irony, exaggeration, and sometimes even self-mockery. He challenges the reader to engage interactively with his ideas in a unique and thought-provoking way.

Nietzsche Contra Wagner, 1888

Nietzsche Contra Wagner was published in 1888 and is yet another fascinating late work that speculates upon the complex relationship between Friedrich Nietzsche and Richard Wagner . In this book, Nietzsche expresses a deep-seated discontentment and disillusionment with the music of Wagner as well as with Wagner himself.

The origin of Nietzsche Contra Wagner can be traced to their earlier close friendship; first, according to him, he had felt like a brother to Wagner—an artist who had broken all those shackles of conventional aesthetics. But in time, their ideological differences became increasingly apparent.

At its core, Nietzsche Contra Wagner is not merely an attack on the musical compositions of Wagner but an exploration of the profound philosophical disagreements between them. In Nietzsche’s eyes, in Wagner’s music, he found jubilation over decadence and affirmation of what he calls “the will to negate life.”

Nietzsche blames Wagner primarily for being swayed by the cultural pressures surrounding him and allowing his artistic vision to be diluted by outside influences. Nietzsche also blames the way in which Wagner employs massive musical grandeur as well as epic themes as a mere distraction from more “deeply existential” questions regarding human life.

Further, Nietzsche finds it deplorable what he sees as Wagner’s embracement of anti-Semitic sentiments and nationalist sentiments for personal gain—a factor that becomes rather meaningful considering that at this time period, Germany was seeing rising nationalism and anti-Semitism .

In Nietzsche Contra Wagner , we see how Friedrich Nietzsche wrestles with disillusionment—a realization that someone he used to respect very much has now become representative not only of artistic differences but also deeper moral conflicts.

The Birth Of Tragedy From The Spirit Of Music, 1872

In 1872, Friedrich Nietzsche published his first major work, The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music. The book looks at the origin stories behind Greek tragic drama and how crucial it is in gaining an understanding of human existence.

Nietzsche begins this work by looking at the opposition between two artistic principles: the Apollonian and Dionysian . The Apollonian stands for order, harmony, and rationality, while the Dionysian embodies passion, ecstasy, and irrationality. For Nietzsche, ancient Greek tragedy has merged these two elements into substantial insights into life’s complexities.

For Nietzsche, Greek tragedy appeared as a reaction to the unbearable reality of existence. The human condition is characterized by suffering and chaos, but tragedy helps individuals transcend their suffering by offering aesthetic catharsis. Through music, dance, and poetry in tragedy’s mix, individuals can experience a temporary release from their personal struggles and even move outside toward something greater than themselves.

In Nietzsche’s opinion, The Birth of Tragedy was not simply artistic expression alone; it had wider cultural implications. He says that modern society has become too highly rationalized and is out of touch with its fundamental Dionysian instincts. In excluding this inner chaos from our lives, we have evolved a contrived order that chokes creativity and stifles real human experience.

The Birth of Tragedy was met with much suspicion from the academic milieu at the time, yet it laid important foundations for Nietzsche’s later works. He introduces his conceptual framework for how art, culture, and the human condition relate to one another. By exploring where Greek tragedy originally came from, Nietzsche lays deep truths about existence and reveals just how there is that same tension between order and chaos that lies underneath every human endeavor.

Philosophy In The Tragic Age Of The Greeks, 1873

In the work Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks , Friedrich Nietzsche talks about some of the philosophical ideas and outlooks of important characters during ancient Greek times. Published in 1873, these ancient Greek philosophers were to be presented to generations as flawless individuals whose views on life and existence were relevant and worthy of being respected and appreciated.

One philosopher explored is Thales , who proposed that water is the ultimate origin of all things. Three reasons are listed by Nietzsche why this idea should be considered a serious proposition: it offers a statement about the primal source of everything, it avoids mythical or fictional language, and it reflects a vision that sees all things as fundamentally interconnected.

Another figure that the philosopher considered is that of Anaximander , who believed in the emanation of existing things from an undifferentiated source ( apeiron ) and, ultimately, return to it. He thus held that individual existence is, by nature, unjust or has no worth in itself. His way of life was therefore reflected in his philosophy, marked with a dignified, solemn demeanor.

Heraclitus offered a contrasting perspective, emphasizing continuous change as the natural order rather than perceiving injustice or guilt in it. According to him, reality demonstrates a fixed regularity amongst the constant flux. Heraclitus wittingly made paradoxical statements based on his observations of a world conditioned by constant variations.

Parmenides , according to Nietzsche, departed from the views presented by Heraclitus with his doctrine that stressed pure logic above sensory experience. He asserted that being is immutable, while the senses are deceptive. Parmenides argued that true reality lies in the realm of thought, where logic prevails over the ever-changing nature of sensory perception. In Nietzsche’s interpretation, being as portrayed by Parmenides was a subjective instead of an objective truth.

Anaxagoras also agreed with Parmenides in denying nothingness and the principle of becoming. He believed that out of infinitely many distinct prime substances, all things originate and intermingle. Anaxagoras speaks about “ nous ”, a mind or intelligence, as the first cause behind all later changes in the universe. Rather than attributing ethical or moral properties to this creative force, Nietzsche saw it as a mechanical and arbitrary process driven by playfulness.

Untimely Meditations, 1876

Untimely Meditations , published in 1876, is a collection of four essays offering a restricted view into Nietzsche’s early philosophical development and thus preparing the way for his later works. Generally neglected as compared to his more recognized books like Thus Spoke Zarathustra or Beyond Good and Evil , Untimely Meditations remains a crucial resource for untangling Nietzsche’s evolving ideas.

In these essays, Nietzsche critically examines contemporary German culture and its conformity to societal expectations. He asserts that true intellectual development is only possible through the negation of prevailing conventions and a reassessment of values. Through different mediums, such as literature, philosophy, and history, Nietzsche seeks to challenge readers to reevaluate their assumptions about tradition, morality, and education.

The essay “David Strauss: The Confessor and the Writer” is one of the more interesting in this collection. In it, Nietzsche criticizes David Strauss’s book The Old Faith and the New for misguidedly trying to reconcile religion with rationality. He states that instead of seeking to harmonize opposing worldviews, intellects should engage in radical critique so as to unearth deeper truths.

Another interesting essay is “On the Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life.” In that piece, Nietzsche again challenges conventional historical scholarship oriented on accumulating facts about the past. He asserts that history should serve life by providing inspiration, lessons, and models for present-day existence. His call for a more life-affirming approach to history emphasizes its potential impact on shaping individuals’ values and actions.

Through Untimely Meditations , Nietzsche articulates his acute wit together with deep philosophical revelations. Each essay is an embodied argument, which adds to the general theme in Nietzsche’s work of critiquing conformity within society and motivating one’s search for truth and authenticity.

Human All Too Human, 1878

We have already touched upon Nietzsche’s famous work Human, All Too Human . However, there were two parts. The basic difference between Human, All Too Human (1878) and the subsequent edition published in 1880 lies in the additional content included in the later version.

In the 1878 edition, Nietzsche presents a collection of 638 aphorisms that range over topics from metaphysics to criticism of the Christian idea of good and evil. There are also reflections on religious worship and divine inspiration in art; social Darwinism discussion; analyses of the roles of men, women, and children in society; exploring state power; and finally, a section titled “Man Alone with Himself,” which turns inward to explore individuality.

Interestingly, in the version of Human, All Too Human , published in 1880, Nietzsche updates what he originally wrote by adding two further parts: Part II —408 aphorisms and Part III –350aphorisms. These further digressions build upon themes introduced within the first part whilst seeing beyond into new territory.

Such additions cover art and culture, science and knowledge, morality, freedom, love and relationships, religion’s command over human life, death, suffering, and solitude, among other life experiences. The inclusion of these later aphorisms widens our perspective on Nietzsche’s philosophy since it gives us deeper insights into what he thought about the above topics.

In general terms, though both editions have some similarities with respect to their content—such as Nietzsche’s criticism against religion and societal norms—the extended versions found in later editions provide readers with a deeper exploration of his philosophical ideas.

The Will to Power (& Why It’s Problematic)

Finally, right in the wide territory of philosophical works of Friedrich Nietzsche, The Will to Power towers as a lofty monolith. It is a book that goes into the depths of human nature and explores what lies behind our actions and ambitions. But with its undeniable allure comes a heavy dose of controversy and debate.

The Will to Power brings us, metaphorically speaking, on a journey through the search for power through Nietzsche’s exploration of the basic principle that underlies every form of human behavior: the challenge for power. This will to power is inborn in every facet of human life—from our most elementary instincts and loftiest aspirations. It is a force so powerful that it can mold not only individual lives but entire cultures and societies as well.